Table of Contents

UNITED STATES

SECURITIES AND EXCHANGE COMMISSION

WASHINGTON, DC 20549

FORM 10-K

| x | ANNUAL REPORT PURSUANT TO SECTION 13 OR 15(d) OF THE SECURITIES EXCHANGE ACT OF 1934 |

For the fiscal year ended December 31, 2012

| ¨ | TRANSITION REPORT PURSUANT TO SECTION 13 OR 15(d) OF THE SECURITIES EXCHANGE ACT OF 1934 |

For the Transition Period from to

Commission File Number: 001-35405

CEMPRA, INC.

(Exact name of registrant specified in its charter)

| Delaware | 2834 | 45-4440364 | ||

(State or Other Jurisdiction of Incorporation or Organization) | (Primary Standard Industrial Classification Code Number) | (I.R.S. Employer Identification No.) |

6340 Quadrangle Drive, Suite 100

Chapel Hill, NC 27517

(Address of Principal Executive Offices)

(919) 313-6601

(Telephone Number, Including Area Code)

Securities Registered Pursuant to Section 12(b) of the Exchange Act:

Title of Each Class | Name of Exchange on which Registered | |

| Common Stock, $0.001 Par Value | Nasdaq Global Market |

Securities Registered Pursuant to Section 12(g) of the Act: None

Indicate by check mark if the registrant is a well-known seasoned issuer, as defined in Rule 405 of the Securities Act. Yes ¨ No x

Indicate by check mark if the registrant is not required to file reports pursuant to Section 13 or Section 15(d) of the Exchange Act. Yes ¨ No x

Indicate by check mark whether the registrant (1) has filed all reports required to be filed by Section 13 or 15(d) of the Securities Exchange Act of 1934 during the preceding 12 months (or for such shorter period that the registrant was required to file such reports), and (2) has been subject to such filing requirements for the past 90 days. Yes x No ¨

Indicate by check mark whether the registrant has submitted electronically and posted on its corporate Web site, if any, every Interactive Data File required to be submitted and posted pursuant to Rule 405 of Regulation S-T during the preceding 12 months (or for such shorter period that the registrant was required to submit and post such files). Yes x No ¨

Indicate by check mark if disclosure of delinquent filers pursuant to Item 405 of Regulation S-K is not contained herein, and will not be contained, to the best of the registrant’s knowledge, in definitive proxy or information statements incorporated by reference in Part III of this Form 10-K or any amendment to this Form 10-K. ¨

Indicate by check mark whether the registrant is a large accelerated filer, an accelerated filer, or a smaller reporting company. See definitions of “large accelerated filer,” “accelerated filer” and “smaller reporting company” in Rule 12b-2 of the Exchange Act. (Check one):

| Large accelerated filer | ¨ | Accelerated filer | ¨ | |||

| Non-accelerated filer | x (Do not check if a smaller reporting company) | Smaller reporting company | ¨ | |||

Indicate by check mark whether the registrant is a shell company (as defined in Rule 12b-2 of the Exchange Act). Yes ¨ No x

The aggregate market value of the voting stock held by non-affiliates of the registrant, as of June 29, 2012, was approximately $81.7 million. Such aggregate market value was computed by reference to the closing price of the common stock as reported on the Nasdaq Global Market on June 29, 2012. For purposes of making this calculation only, the registrant has defined affiliates as including only directors and executive officers and shareholders holding greater than 10% of the voting stock of the registrant as of June 29, 2012. The registrant became a publically reporting company on February 2, 2012 and did not meet the definition of an accelerated filer as of December 31, 2012.

As of March 1, 2013 there were 24,903,774 shares of the registrant’s common stock, $0.001 par value, outstanding.

DOCUMENTS INCORPORATED BY REFERENCE

Certain portions of the registrant’s definitive Proxy Statement for its 2013 Annual Meeting of Stockholders are incorporated herein by reference, as indicated in Part III.

Table of Contents

CEMPRA, INC.

i

Table of Contents

This report contains forward-looking statements within the meaning of Section 27A of the Securities Act of 1933 and Section 21E of the Securities Exchange Act of 1934. These forward-looking statements are subject to risks and uncertainties, including those set forth under “Item 1A. Risk Factors” and “Cautionary Statement” included in “Item 7. Management’s Discussion and Analysis of Financial Condition and Results of Operations” and elsewhere in this report, that could cause actual results to differ materially from historical results or anticipated results.

Overview

We are a clinical-stage pharmaceutical company focused on developing antibiotics to meet critical medical needs in the treatment of infectious diseases, particularly respiratory tract infections and chronic staphylococcal infections. Our lead program is solithromycin (CEM-101), which we are developing in both oral and intravenous, or IV, formulations initially for the treatment of community acquired bacterial pneumonia, or CABP, one of the most serious infections of the respiratory tract. We have completed a successful Phase 2 clinical trial of the oral formulation for the treatment of CABP, demonstrating a favorable safety and tolerability profile and comparable efficacy to the current standard of care, levofloxacin, a respiratory fluoroquinolone. In December 2012, we initiated a pivotal Phase 3 trial for oral solithromycin in patients with CABP. We are also pursuing a second indication, bacterial urethritis, primarily gonorrhea, for which there is an urgent public health need. In this indication, in October 2012 we released data from a Phase 2 study in which solithromycin was demonstrated to be highly effective in treating uncomplicated gonorrhea.

Our second program is Taksta, an antibiotic known as fusidic acid, that has been used for decades outside the U.S., including western Europe. We are developing Taksta in the U.S. as an oral treatment for long term treatment of prosthetic joint infections caused by staphylococci, includingS. aureus and methicillin-resistantStaphylococcus aureus, or MRSA. Taksta successfully completed a Phase 2 clinical trial in patients with acute bacterial skin and skin structure infections, or ABSSSI, which is frequently caused by MRSA, demonstrating a favorable safety and tolerability profile and comparable efficacy to linezolid (sold under the brand name Zyvox®), the only oral antibiotic for the treatment of MRSA approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration, or FDA. Having shown that Taksta is well tolerated and is active against current strains of MRSA in the U.S., in December 2012, we initiated a Phase 2 trial with Taksta in patients with prosthetic joint infections which is also primarily caused by staphylococci and for which safe, oral antibiotics for long term use are not currently available.

We have global rights (other than the Association of South East Asian Nations, or ASEAN, countries, which are Brunei Darussalam, Cambodia, Indonesia, Laos, Malaysia, Myanmar (Burma), the Philippines, Singapore, Thailand and Vietnam) to solithromycin and are developing Taksta exclusively for the U.S. market.

Our goal is to develop differentiated antibiotics. We believe there are two main challenges that antibiotic candidates must overcome to be considered truly differentiated from currently-available antibiotics and those in development. The first is spectrum of activity. In addition to having activity against bacteria that have become resistant to generic antibiotics, one should focus on “the right spectrum” rather than broad spectrum. The right spectrum means an antibiotic that is active against most or all of the pathogens that are involved in a particular infection and could reduce the need for polytherapy. It also means that collateral damage to important bacteria such as gut flora is limited so that unintended side effects do not occur. We believe that solithromycin fits this profile as it is active against many key CABP pathogens as well as against pneumococcal strains resistant to other macrolides. The second is that there are many generic antibiotics. To compete effectively, each of our products will have to be sufficiently differentiated, based on efficacy, safety, dosing flexibility, and/or other factors, from competing products to enable it to address a meaningful market.

Solithromycin (CEM-101)

Solithromycin is a potent new macrolide that we are developing in oral and IV formulations for the treatment of respiratory tract infections, including CABP, which is one of the most common serious infectious diseases of the respiratory tract, and bacterial urethritis, including gonorrhea, the second most common infectious disease in the world. Historically, macrolides, including azithromycin, have been among the most frequently prescribed drugs for respiratory tract infections because of their combination of spectrum of antibacterial activity, safety for use in adult and pediatric patients, availability in oral and IV formulations, and strong anti-inflammatory properties. Spectrum of activity refers to the antibiotic’s ability to protect against a range of bacterial types. The effectiveness of macrolides for treating serious respiratory tract infections such as CABP, however, has declined due to resistance issues related to earlier generations of macrolides. Macrolide use for serious infections has generally been replaced by fluoroquinolones, including levofloxacin, despite this class having a less desirable safety and tolerability profile than macrolides. Solithromycin is being developed for moderate to moderately severe CABP. We are also developing solithromycin as a treatment for bacterial urethritis, including gonorrhea. As with respiratory tract pathogens,Neisseria gonorrheae,has become resistant to macrolides, including azithromycin and other classes of antibiotics. We believe solithromycin, with its unique chemical structure, retains and improves on the beneficial features of macrolides and can overcome the shortcomings of existing therapies.

Our Phase 1 and Phase 2 clinical trials and pre-clinical studies to date have shown that solithromycin has the following attributes:

| • | favorable safety and tolerability profile; |

| • | comparable efficacy to the current standard of care; |

| • | potent activity against a broad range of bacteria with excellent tissue distribution and intracellular activity; |

| • | lower incidence of resistance development; |

| • | potential for IV, oral and suspension formulations that may allow it to be used in broad patient populations and settings; |

| • | potential for pediatric development; and |

2

Table of Contents

| • | anti-inflammatory qualities to help patients feel better sooner during treatment. |

In the third quarter of 2011, we completed a successful Phase 2 clinical trial in 132 CABP patients comparing the oral formulation of solithromycin to levofloxacin, a respiratory fluoroquinolone which is the current standard of care. In this trial, solithromycin demonstrated efficacy comparable to levofloxacin and a favorable safety and tolerability profile, with a lower incidence of treatment emergent adverse events than levofloxacin.

We designed our pivotal Phase 3 trial for oral solithromycin to treat CABP based on comments we received from the FDA. We believe that we will need two Phase 3 trials to support our planned NDA for solithromycin to treat CABP: one trial with oral solithromycin and another trial with IV solithromycin stepping down to oral solithromycin. These trials will be randomized, double-blinded studies conducted against a respiratory fluoroquinolone, moxifloxacin (Avelox), for which we will have to show non-inferiority for efficacy and acceptable safety and tolerability. Non-inferiority for efficacy means solithromycin will have to prove it is statistically as effective as a comparator drug within a pre-defined margin. In 2011, the FDA clarified the guidance for the clinical development of therapies for the treatment of CABP. We have designed our Phase 3 trials to meet FDA guidelines. The FDA reviewed and provided comments on our oral Phase 3 trial protocol and we began the Phase 3 trial with oral solithromycin in December 2012. In October 2012, we reported results from our Phase 1 trial for the IV formulation of solithromycin in which we demonstrated that IV solithromycin demonstrated good systemic tolerability, showed a favorable pharmacokinetic (PK) profile and achieved relevant plasma concentrations. Based on this study, we have selected a therapeutic dose of 400 mg administered once daily for up to seven days for the Phase 3 IV-to-oral step down trial. We plan to finalize the overall development program for solithromycin for CABP with the FDA at our end of Phase 2 meeting for solithromycin, which we expect will occur in the first half of 2013 and to initiate the IV to oral trial in the second half of 2013, subject to available resources.

In addition, we are studying solithromycin for the treatment of bacterial urethritis, including uncomplicated gonorrhea. The current standard of treatment for gonorrhea is a single intramuscular injection of ceftriaxone. Until recently, cefixime (Suprax) had been recommended for oral treatment of patients as well as for treatment of their potentially infected partners. However, as of August 2012, the Centers for Disease Control, or CDC, no longer recommends cefixime for the treatment of gonorrhea, which leaves no oral treatment option. In our preclinical studies, solithromycin has demonstrated in vitro activity against most drug-resistant gonococcal bacteria. In our Phase 2 open-label study begun in June 2012 and that, as of the date of this report, has enrolled 28 patients with suspected gonococcal infection, a single oral dose of solithromycin was administered. In October 2012, we reported that the primary endpoint of bacterial eradication as measured by conversion from positive baseline urethral or cervical cultures to negative at seven days was achieved in 100% of evaluable patients (22 patients with positive baseline cultures). Pharyngeal and rectal gonococcal infections were also cleared in this study. Because this is a second indication for which we intend to seek regulatory approval, we anticipate that a single Phase 3 trial in bacterial urethritis/cervicitis (primarily gonorrhea), will be sufficient for FDA approval for this indication.

Taksta

Taksta is an oral therapy that we are developing in the U.S. for the treatment of prosthetic joint infections, which are frequently caused by staphylococci, includingS. aureus, MRSA, coagulase negative staphylococci and other Gram-positive bacteria. Taksta is a novel and proprietary dosing regimen of fusidic acid, which is an approved antibiotic that has been sold by Leo Laboratories, Ltd. primarily for staphylococcal infections, including skin, soft tissue and bone infections, for several decades in Europe and other countries outside the U.S. and has a long-established safety and efficacy profile. We believe Taksta has the potential to be used in hospital and community settings on both a short-term and chronic basis. Since prosthetic joint infection is primarily treated with a combination of IV and oral drugs, we believe that Taksta would enable out-patient treatment of many patients who would otherwise require hospitalization, which we also believe would provide pharmacoeconomic advantages, be well received by doctors and be more convenient for patients. We have filed a patent application for our proprietary dosing regimen which has been shown with pharmacodynamics experiments to limit resistance development. In addition, fusidic acid is eligible for market exclusivity under the Drug Price Competition and Patent Term Restoration Act, also known as the Hatch-Waxman Act. If approved for prosthetic joint infections, Taksta could be eligible for orphan drug status in the U.S., which would provide seven years of market exclusivity. Taksta would also be eligible for an additional five years of exclusivity based upon the Generating Incentives for Antibiotics Now, or GAIN Act, since MRSA is listed in the law as a qualified infectious disease pathogen. Therefore, Taksta could qualify for as much as 12 years of exclusivity in total. Taksta also could receive additional six months exclusivity if approved for pediatric indications.

According to a survey of physicians conducted by Decision Resources, MRSA is the most important pathogen of concern in patients with osteomyelitis and prosthetic joint infection. Bone infections often begin with skin infections where bacteria enter the bloodstream through breaks in the skin or mucous membrane that occur as a result of a wound or due to a surgical, medical or dental procedure.

3

Table of Contents

Our clinical trials and pre-clinical studies to date, as well as historical data from outside the U.S., have shown that Taksta has the following attributes:

| • | established safety profile; |

| • | comparable efficacy to the only FDA-approved oral treatment for MRSA; |

| • | ability to be used orally as a treatment for all types ofS. aureus, including MRSA; |

| • | lower frequency of resistance development due to our loading dose regimen; and |

| • | potential to be used in patient populations not well served by current treatments. |

In 2010, we successfully completed a Phase 2 clinical trial with Taksta in ABSSSI patients. In this trial, the Taksta loading dose regimen demonstrated efficacy, safety and tolerability that was comparable to linezolid. Like ABSSSI, prosthetic joint infections are often caused byS. aureus, including MRSA. In December 2012, we initiated a Phase 2 trial of Taksta in patients with prosthetic joint infections.

The Limitations Associated with Antibiotics

The widespread use of antibiotics has led to development of resistant strains of bacteria, which limits the effectiveness of existing drugs. This led the World Health Organization to state in 2010 that antibiotic resistance is one of the three greatest threats to human health. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention estimates that more than 70% of U.S. hospital infections are resistant to at least one of the antibiotics most commonly used to treat them.

Antibiotic resistance is primarily caused by genetic mutations in bacteria selected by exposure to antibiotics where the drug does not kill all of the bacteria. In addition to mutated bacteria being resistant to the drug used for treatment, many bacterial strains can also be cross-resistant, meaning that the use of a particular treatment to address one kind of bacteria can result in resistance to other kinds of bacteria as well as to other antibiotics. As a result, the effectiveness of many antibiotics has declined, limiting physicians’ options to treat serious infections and creating a global health issue. For example, it is estimated that in the U.S. 44% of pneumococci, the primary pathogen involved in respiratory tract infections, are resistant to azithromycin and other macrolides commonly used to treat them. Antibiotic resistance has a significant impact on mortality and contributes heavily to health care system costs worldwide.

In addition to resistance issues, current antibiotic therapies also have other limitations, including serious side effects. These side effects may include: severe allergic reaction, decreased blood pressure, nausea and vomiting, suppression of platelets, pain and inflammation at the site of injection, muscle, renal and oto toxicities, optic and peripheral neuropathies and headaches. Some of these side effects may be significant enough to require that therapy be discontinued or not used. As a result, some treatments require clinicians to closely monitor patients’ blood levels and other parameters, increasing the expense and inconvenience of treatment.

Further, many of the existing antibiotics used to treat serious infections are difficult or inconvenient to administer. Many drugs are given twice daily for seven to 14 days or more and patients can be hospitalized for much or all of this period or require in-home IV therapy. While IV treatment delivers the drug more rapidly and in a larger dose than is possible orally, once a patient is stabilized, a step-down to oral treatment allows for more convenient and cost-effective out-patient treatment. We believe that there is a need for new antibiotics that have improved potency and pharmacokinetics, effectiveness against resistant bacterial strains, improved side effect profiles and more flexible administration formulations.

The FDA has issued proposed guidelines for CABP that impact the development of new antibiotics by recommending certain protocol elements, measures and endpoints for clinical trials. Recent public FDA discussions have evolved toward requiring that new drugs demonstrate non-inferiority to the current standard of care for the disease to be treated, within a predetermined non-inferiority margin. We believe the FDA guidance is helpful in clarifying the regulatory pathway for our product candidates and, given the data that we have gathered to date on our product candidates, reinforces our belief that our product candidates can establish non-inferiority while also demonstrating efficacy against susceptible and resistant bacterial strains and improved safety. Our clinical trials for solithromycin have been designed with these guidelines in mind.

Solithromycin

Overview

We are developing solithromycin, a fourth generation macrolide, to treat respiratory tract infections, including CABP and also for treating bacterial urethritis. Traditionally, macrolides have been among the most commonly prescribed drug for respiratory tract infections because of their combination of spectrum of activity, safety for use in adult and pediatric patients, tissue distribution and activity against intracellular pathogens, pharmacokinetics allowing use in oral and IV formulations, and anti-inflammatory properties. However, the effectiveness of macrolides for treating serious respiratory tract infections such as CABP has declined due to resistance issues related to earlier generations of macrolides. We believe our clinical and pre-clinical results suggest that solithromycin retains and improves on the benefits of, and overcomes the shortcomings of, earlier generation macrolides.

4

Table of Contents

Solithromycin Market Opportunity

We are developing solithromycin in both oral and IV formulations initially as a treatment for CABP, which is a respiratory tract bacterial infection acquired outside of a hospital setting. Respiratory tract infections can range from severe diseases such as pneumonia (CABP), to similar infections of the respiratory tract such as pharyngitis (which is usually referred to as strep throat), bronchitis, chronic sinusitis and middle ear infections (which are especially common in children). CABP is one of the most common serious infectious diseases of the respiratory tract and is the most frequent cause of death due to bacterial infections. There are 1.6 million fatal cases of pneumococcal disease annually worldwide which is more than the deaths caused annually by breast or prostate cancer. There are approximately five to six million cases of CABP in the U.S. every year, approximately one million of which require hospitalization. Typical bacteria that cause CABP includeStreptococcus pneumoniae,Haemophilus influenzae, andMoraxella catarrhalis. These three bacteria account for approximately 85% of CABP cases. Other organisms may be involved in CABP and includeLegionella pneumophila,S. aureus,Chlamydophila pneumoniaeandMycoplasma pneuomoniae.

Many respiratory tract infections, including CABP, involve multiple bacteria. The routine diagnostic tests available to a physician can only identify a pathogen in 10% to 25% of cases and that diagnosis can take several days. Since infections can be serious and potentially life threatening, physicians cannot delay treatment while waiting for the results of these diagnostic tests to identify the pathogens involved in the disease. As a result, physicians seek to begin treatment with the antibiotic or combination of antibiotics that has the broadest activity against the bacteria thought to be causing the infection.

CABP and other respiratory tract infections can be treated with numerous classes of antibiotics, including macrolides, tetracyclines, fluoroquinolones, penicillins and cephalosporins. Each class has a different mechanism of action and resulting spectrum of activity. Each class, however, whether used alone or in combination, has limitations that can impede the treatment of CABP infections. Historically, macrolides have been among the most commonly prescribed drug for respiratory tract infections because of their broad spectrum of activity and relative safety. Azithromycin, a second generation macrolide which is sold as Zithromax and Z-PAK and as a generic, is the most widely prescribed macrolide with total U.S. prescriptions of 52 million in 2010, according to IMS Health, and sales of $1.1 billion, according to Medical Marketing & Media.

In recent years, the effectiveness of earlier generation macrolides, including azithromycin, to treat serious infections such as CABP has declined due to resistance issues. The most recently approved macrolide, telithromycin (Ketek), has seen limited use because of serious side effects. For these reasons, fluoroquinolones, such as levofloxacin, now are commonly used for serious CABP infections. Although levofloxacin is efficacious, it has serious side effects includingC. difficile enterocolitis, tendonitis, hepatotoxicity and central nervous system effects. Beta-lactams, such as cephalosporins, which are commonly used in CABP, also have limitations, including limited coverage against several important bacteria such asLegionella andMycoplasma. In addition, the newer cephalosporins can only be administered intravenously, which is a disadvantage if the patient does not need to be hospitalized or needs step-down oral therapy to enable treatment on an out-patient basis. The American Thoracic Society, or ATS, and the Infectious Diseases Society of America, or IDSA, recommend a macrolide together with a beta-lactam (such as a cephalosporin) to treat CABP. Alternatively, ATS and IDSA recommend physicians treat CABP with fluoroquinolones. The recommended combination of a macrolide with a beta-lactam has been shown to enhance survival; when a macrolide is not used, an increase in mortality has been shown.

We believe that the initial market acceptance of Ketek, which, according to IMS Health, in 2005, its first full year after FDA approval, generated 3.4 million prescriptions and $193 million in sales in the U.S., demonstrates the potential for a new macrolide therapy. However, soon after its U.S. approval in 2004, Ketek was found to cause reversible visual disturbances, loss of consciousness, exacerbate myasthenia gravis (a neurological disorder characterized by improper muscle regulation) and cause liver toxicity resulting in liver failure. Ketek was withdrawn in 2007 for use in all infections other than CABP, and as a result, the large market predicted for Ketek has not developed. While Ketek is a macrolide, solithromycin has a different chemical structure from Ketek, and therefore we believe is not likely to have the safety issues associated with Ketek. Our research, which was published in a peer-reviewed article inAntimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy, suggests that pyridine, a chemical component of Ketek, is the agent that causes liver toxicity and other problems associated with Ketek. solithromycin and older generation macrolides, including azithromycin and clarithromycin, do not have a pyridine component and have not been observed to cause the serious side effects associated with Ketek. We believe that solithromycin has the potential to be more successful than Ketek if our Phase 3 trials confirm the efficacy and safety profile demonstrated in our previous trials.

As a result of the limitations of current therapies for CABP, we believe there is an opportunity to introduce a next generation macrolide that is more potent and effective against bacteria that are resistant to older generations of macrolides, while retaining the traditional safety and anti-inflammatory properties that macrolides are known to exhibit. To date, our Phase 1 and Phase 2 clinical trials have demonstrated that solithromycin is potent and effective against resistant bacteria and is well tolerated, with no serious adverse events. We also believe that developing IV and oral formulations will provide flexibility to physicians to treat patients according to the severity of their disease and transition some patients from IV to oral, enabling them to leave the hospital sooner. If approved by the FDA, solithromycin would be the first macrolide approved with both IV and oral formulations since azithromycin was approved 20 years ago.

5

Table of Contents

In addition to CABP, there is a large public health need for a new and effective oral treatment for treating bacterial urethritis. Resistance has emerged to cefixime, which is the only remaining oral therapy for gonococci infections, such as bacterial urethritis. Our preclinical data suggests that solithromycin is active against most bacterial pathogens known to be involved in bacterial urethritis including gonococci, chlamydia and mycoplasma. The CDC and key opinion leaders have expressed the need for an oral antibiotic as a replacement for cefixime because of resistance development. The development of solithromycin for bacterial urethritis would present an additional market opportunity for solithromycin and all of the patient data gathered in any trials would also contribute to the safety data base for CABP development.

Key Attributes of Solithromycin

We believe the following key attributes of solithromycin will make it a safe and effective treatment for CABP and bacterial urethritis.

Solithromycin has demonstrated a favorable safety and tolerability profile. Solithromycin has been tested in over 490 subjects in our Phase 1 and 2 clinical trials and has been shown to be safe and well tolerated to date. There were no clinically significant laboratory abnormalities in the Phase 1 trials. In the Phase 2 trial, there were fewer adverse events compared to levofloxacin, none of which required the patient to prematurely discontinue treatment with solithromycin, and no serious adverse events determined by the investigator to be related to solithromycin. Patients in our single and multi-dose Phase 1 IV trial showed no clinically significant liver enzyme changes associated with solithromycin at the selected therapeutic doses, indicating no liver toxicity. Additionally, in this study solithromycin did not produce dose-limiting nausea or vomiting, or effect the heart, which are common side effects of other macrolides.

Solithromycin has demonstrated comparable efficacy to the current standard of care. In our Phase 2 trial in 132 CABP patients comparing the oral formulation of solithromycin to levofloxacin, solithromycin successfully demonstrated efficacy comparable to levofloxacin. In addition, solithromycin has been highly effective in a Phase 2 trial of bacterial urethritis.

Solithromycin is potent against a broad range of bacteria and has excellent tissue distribution and intracellular activity. In pre-clinical studies, solithromycin was shown to be generally eight to 16 times more potent against respiratory tract bacteriain vitro than azithromycin as well as retains activity against azithromycin resistant strains. These pre-clinical studies also showed that solithromycin is potent against many bacteria that are resistant to levofloxacin and other fluoroquinolones. In addition to respiratory tract infections, solithromycin is active against bacteria causing other types of infections such as urethritis, malaria, and tuberculosis. solithromycin has demonstrated activity against bacterial strains that are not susceptible to older generations of macrolides. In pre-clinical studies, solithromycin has demonstrated a longer post-antibiotic effect, meaning that after exposure to solithromycin, bacteria take longer to regrow than after exposure to other macrolides, supporting the potential for once-daily dosing. Solithromycin has also demonstrated excellent organ and tissue distribution and intracellular activity, addressing not only bacteria located in the blood but also in organs and cells in which they multiply. Bacteria therefore cannot escape from the action of the drug. As a result of its potency, spectrum of activity and pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic properties, we believe that solithromycin could eventually be used as a monotherapy for the treatment of CABP.

Solithromycin has a greater ability to fight resistant bacteria and to overcome resistance development due to its chemical structure. Solithromycin has a unique structure that binds to bacterial ribosomes in three sites while earlier generation macrolides have only one or two binding sites. Therefore, bacteria must mutate at three sites on the ribosome to become resistant to solithromycin. To date, we have seen no resistance to solithromycin in our clinical trials, and resistance was rare in our pre-clinical studies.

Solithromycin has the potential for IV, oral and suspension formulations. We are developing oral and IV formulations to allow patients with severe CABP to be treated in both hospital and out-patient settings. Providing both the IV and oral formulations will enable IV-to-oral step-down therapy. We believe this would be more convenient and cost-effective for patients and provide pharmacoeconomic advantages to health care systems. We intend to develop a suspension formulation for treating bacterial infections in the pediatric population.

Solithromycin has improved anti-inflammatory qualities. In CABP and other bacterial infections, the body’s immune response to the bacteria results in inflammation and tissue damage, which worsens symptoms. In addition to their antibacterial effects, macrolides also have anti-inflammatory properties which help patients feel better earlier. Our pre-clinical data suggest that solithromycin could have significantly greater anti-inflammatory properties than azithromycin and clarithromycin, which are used to treat patients with cystic fibrosis, or CF, and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, or COPD, primarily for their anti-inflammatory properties.

Clinical Data

Phase 2 Oral Trial. We successfully completed a Phase 2 trial of the oral formulation of solithromycin in the third quarter of 2011. The trial was a randomized, double-blinded, multi-center study to evaluate the efficacy and safety of oral solithromycin

6

Table of Contents

compared to oral levofloxacin in 132 patients with CABP. Levofloxacin, which is a respiratory fluoroquinolone, is the current standard of care and widely prescribed for the treatment of CABP. Patients were randomized to receive solithromycin or levofloxacin for five days. solithromycin patients received once-daily dosing of 800 mg on Day 1 and 400 mg on Days 2 through 5. Patients randomized to levofloxacin treatment received the standard dosing regimen of 750 mg per day for five days. The trial compared clinical success rates and safety and tolerability parameters for solithromycin and levofloxacin. The primary outcome measure was continued improvement or complete resolution of baseline signs and symptoms in the intent to treat, or ITT, and the clinically evaluable, or CE, populations at the Test of Cure, or TOC, visit, which was completed five to 10 days after the last dose of the drug.

Outcomes were assessed for several populations within the study. The ITT population consisted of all randomized patients, among whom 85.6% were in the CE group. To be clinically evaluable, key inclusion and exclusion criteria had to be validated, confounding antibiotics for other infections could not have been administered, and key visits and assessments had to have been performed. Patients for whom a microbial pathogen, or the bacteria responsible for the pneumonia, had been identified comprised the microbial-ITT, or mITT, population. Those mITT patients who were also in the CE study group constituted the microbial-evaluable or ME group. Since pneumonia can also be caused by viruses which antibiotics cannot treat, the FDA has placed emphasis on proof of clinical success in the mITT and ME groups.

Solithromycin demonstrated comparable efficacy to levofloxacin. The clinical response rate in the ITT population was 84.6% for solithromycin and 86.6% for levofloxacin. Similarly, clinical response rates for solithromycin and levofloxacin in the mITT and ME populations were well balanced (77.8% vs. 71.4% and 80.0% vs. 76.9%, respectively). The clinical response rates at TOC for the ITT, CE, mITT and ME populations are presented in Table 1.

Table 1. Solithromycin Oral Phase 2 Results: Clinical Response at Test of Cure (Days 5 to 10 after Last Dose).

Population | Clinical Response | Solithromycin 800/400 mg once daily No. of patients (%) | Levofloxacin 750 mg once daily No. of patients (%) | |||

ITT | Number of patients | 65 | 67 | |||

| Success | 55 (84.6) | 58 (86.6) | ||||

| 95% Confidence Interval | (73.5-92.4) | (76.0-93.7) | ||||

| Failure(1) | 10 (15.4) | 9 (13.4) | ||||

| Failure | 9 (13.8) | 7 (10.4) | ||||

| Indeterminate | 1 (1.5) | 2 (3.0) | ||||

CE | Number of patients | 55 | 58 | |||

| Success | 46 (83.6) | 54 (93.1) | ||||

| 95% Confidence Interval | (71.2-92.2) | (83.3-98.1) | ||||

| Failure | 9 (16.4) | 4 (6.9) | ||||

mITT | Number of patients | 18 | 14 | |||

| Success | 14 (77.8) | 10 (71.4) | ||||

| 95% Confidence Interval | (52.4-93.6) | (41.9-91.6) | ||||

| Failure(1) | 4 (22.2) | 4 (28.6) | ||||

| Failure | 3 (16.7) | 4 (28.6) | ||||

| Indeterminate | 1 (5.6) | 0 (0.0) | ||||

ME | Number of patients | 15 | 13 | |||

| Success | 12 (80.0) | 10 (76.9) | ||||

| 95% Confidence Interval | (51.9-95.7) | (46.2-95.0) | ||||

| Failure | 3 (20.0) | 3 (23.1) |

| (1) | Includes clinical response of failure and indeterminate. |

In the CE population, the numerical success rate was higher in the levofloxacin arm (93.1%), with broadly overlapping confidence intervals. This in large part is due to exclusion of a larger number of failure patients from the levofloxacin arm and exclusion of treatment successes from the solithromycin arm on the basis of pre-established study criteria including validation of key inclusion and exclusion criteria and the completion of key visits and assessments.

Under the proposed FDA guidance for the conduct of CABP clinical trials, drug developers will be required to assess early responses to therapy as a primary endpoint. Therefore, we assessed markers of clinical success at the Day 3 visit. A clinical response was achieved if a patient was clinically stable and had experienced an improvement in severity without worsening in any of these signs or symptoms. The early clinical response rate in the ITT population was 72.3% for solithromycin patients, and 71.6% for levofloxacin patients.

7

Table of Contents

Safety was an important focus of this Phase 2 trial. In the trial, patients receiving levofloxacin reported more adverse events and severe adverse events than solithromycin patients. There were 19 patients (29.7%) in the solithromycin group with treatment emergent adverse events, or TEAE, compared with 31 patients (45.6%) in the levofloxacin group. There were no patients in the solithromycin group that discontinued the study due to a TEAE as compared to six patients (8.8%) in the levofloxacin group. The overall incidence of TEAE was greater in the levofloxacin arm, at all degrees of severity. Notably, gastrointestinal disorders, including abdominal discomfort, nausea, and vomiting, all occurred with greater frequency among levofloxacin recipients. The results are summarized in Table 2 below.

Table 2. Solithromycin Oral Phase 2 Results: Treatment-emergent Adverse Events with 2% Incidence in Any Treatment Group.

| By System/Organ | Solithromycin 800/400 mg once daily (No. of patients, n=64) | Levofloxacin 750 mg once daily (No. of patients, n=68) | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Mild n (%) | Moderate n (%) | Severe n (%) | Mild n (%) | Moderate n (%) | Severe n (%) | |||||||||||||||||||

Subjects with at least one TEAE | 10 (15.6) | 6 (9.4) | 3 (4.7) | 14 (20.6) | 11 (16.2) | 6 (8.8) | ||||||||||||||||||

Gastrointestinal Disorders | 5 (7.8) | 4 (6.3) | 0 (0.0) | 11 (16.2) | 5 (7.4) | 0 (0.0) | ||||||||||||||||||

Musculoskeletal and Connective Tissue Disorders | 2 (3.1) | 3 (4.7) | 0 (0.0) | 2 (2.9) | 1 (1.5) | 0 (0.0) | ||||||||||||||||||

Nervous System Disorders | 3 (4.7) | 2 (3.1) | 1 (1.6) | 5 (7.4) | 2 (2.9) | 1 (1.5) | ||||||||||||||||||

In addition to TEAEs, the trial also recorded serious adverse events, which are adverse events of particular severity that, among other defining criteria, might result in hospitalization or threaten overall health or survival. There were nine patients who experienced one or more serious adverse events during the study, two solithromycin recipients and seven levofloxacin recipients. The study site trial investigator determined that both of the serious adverse events reported in solithromycin recipients were unrelated to solithromycin, while one of the seven reported in levofloxacin recipients was unrelated to levofloxacin.

Patients treated with solithromycin had no drug-related clinically significant liver toxicities and reported no visual adverse events. Severe liver toxicities and visual disturbances led the FDA to require the drug label for Ketek to include a strengthened warning section regarding specific drug-related adverse events and contributed to Ketek being withdrawn for the treatment of all infections other than CABP.

Phase 1 IV Trial. The objective of our Phase 1 IV trial for solithromycin was to demonstrate safety and tolerability as well as to select the therapeutic dose after IV administration for our planned second Phase 3, IV to oral step down trial. We tested escalating IV doses of 25 mg, 50 mg, 100 mg, 200 mg, 400 mg, 800 mg and 1000 mg administered as single doses or 200, 400, 600 and 800 mg doses administered once daily for seven days. Patients were randomized into solithromycin and placebo arms. In the trial, the most common adverse events, or AEs, were general disorders and administration site conditions related to infusion discomfort or pain. Our Phase 1 trial also tested infusion solutions designed to minimize injection site pain. No AEs were reported in any of the studies that resulted from clinically significant changes in physical examinations, vital signs, or ECG data. In healthy subjects who received repeat-dose IV solithromycin (200, 400, or 800 mg QD for up to seven days) in the Phase 1 study 20% had asymptomatic and reversible ALT elevations. One subject, who received three daily doses of 800 mg, had a reversible and asymptomatic Grade 4 ALT elevation without bilirubin elevation. These ALT elevations were reversible and not associated with symptoms, bilirubin elevation or cholestasis. No loss-of-consciousness, myasthenia exacerbations, or visual disturbances were observed. Among patients receiving repeated doses of 400 mg daily for up to seven days, no clinically significant systemic adverse events were observed, except injection site pain in some subjects. In addition, the desired PK profile was achieved, with clinically relevant mean peak solithromycin concentrations of 4 micrograms/mL. Modeling of the PK data suggest that initial intravenous dosing with 400 mg once-daily, with a switch to oral administration when clinically appropriate to the same dose as in the oral program, i.e. 800 mg loading dose and 400 mg maintenance dose, will achieve concentrations of the drug that warrant its evaluation in the treatment of moderate to severe community acquired bacterial pneumonia caused by pathogens including azithromycin-resistant pneumococcus, Legionella, Mycoplasma, Moraxella, Hemophilus influenzae,and Staphylococcus aureus , including methicillin susceptible and community-acquired methicillin-resistantStaphylococcus aureus, all of which are infections that could require elevated concentrations of antibiotics. Based on this study, we have selected a therapeutic dose of 400 mg administered once daily for up to seven days for our planned Phase 3 IV-to-oral step down trial with the option of stepping down to oral treatment of solithromycin when appropriate as decided by the physician based on decreased symptoms.

Phase 1 Oral Trials. In earlier Phase 1 oral trials beginning in 2008 and continuing into 2011, 159 subjects were exposed to solithromycin. The Phase 1 trials were designed to examine the safety of solithromycin and the properties of the drug when absorbed

8

Table of Contents

into the bloodstream. There were no clinically relevant changes in patient laboratory values, including liver enzymes. There were very limited gastrointestinal adverse events and no dose-limiting nausea or vomiting, a common side effect of macrolides. Absorption of solithromycin into the bloodstream after oral administration was not affected by food, meaning solithromycin may be taken with or without food.

The results from our first Phase 1 dose escalation study demonstrated that doses of solithromycin from 200 mg to 600 mg had a favorable safety profile and were well tolerated in healthy subjects and that the compound’s pharmacokinetic profile was supportive of once-daily dosing. In this study, solithromycin was administered orally once-daily for seven days at 200 mg, 400 mg and 600 mg. The bioavailability of solithromycin was calculated to be 67% whereas azithromycin’s bioavailability is 38% as reported in its package insert. The concentration of solithromycin was measured in the plasma on Day 1 and Day 7. The compound showed moderate accumulation over the seven days of dosing, indicating that a loading dose regimen followed by a maintenance dose would be suitable, as has been noted with macrolides like azithromycin in the past. These blood levels were subjected to a sophisticated computer model based on efficacy studies in mouse models, which led to identifying a loading dose of 800 mg with a maintenance dose of 400 mg as the therapeutic dose. At these doses solithromycin is expected to be clinically effective against 99.99% of pneumococci with a minimum inhibitory concentration, or MIC, of 2 µg/ml or less, while no pneumococcal strains with an MIC of >1 mcg/ml have been identified in any of the surveillance programs. Mild, clinically insignificant gastrointestinal side effects were the most common adverse events observed in each dose group. Importantly, there were no clinically significant adverse events.

In CABP, the lung is the target organ where pathogens replicate. Therefore, in the first quarter of 2010, we conducted a Phase 1 pharmacokinetic study of solithromycin in 31 healthy human volunteers to measure the concentration of solithromycin in the epithelial lining fluid, or ELF, and in alveolar macrophages, or AM, compared to the concentration in plasma. After five days of dosing (400 mg per day, without loading), we performed bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL), a medical procedure to collect fluid and cells in the lung. BAL analysis was performed in groups of six at 3, 6, 9, 12 or 24 hours following the last solithromycin dose on Day 5, and solithromycin concentrations were measured in each of the ELF, AM, and plasma. The concentration of solithromycin in ELF was 10 times that of plasma and in AM it was 100 times that of plasma. As shown in Table 3, solithromycin’s drug levels are higher than those achieved by azithromycin and solithromycin reaches the site of infection at concentration levels several fold in excess of the levels necessary to kill the relevant bacteria according to our pre-clinical studies. Higher drug levels also inhibit bacterial regrowth and resistance development during intervals between dosages.

Table 3: Solithromycin Oral Phase 1 Results: Pulmonary Levels of Solithromycin and Azithromycin at Time of BAL.

Antibiotic | Dose | Plasma Cmax (µg/mL) | ELF Cmax (µg/mL) | AM Cmax (µg/mL) | ||||||||||

Solithromycin | 400 mg qd/5 d | 0.7 | 7.6 | 102 | ||||||||||

Azithromycin(1) | 500 mg qd/1 d; 250 mg qd/4 d | 0.1 | 2.2 | 57 | ||||||||||

| (1) | Zithromax Prescribing Information with loading dose of 500 mg on Day 1 followed by 250 mg daily for four days, Foulds, et.al., 1990. |

We also conducted three drug-drug interaction studies in 2010 and 2011 in which solithromycin was co-administered with rifampin, midazolam or ketoconazole to test its effects on these drugs. These studies have been successfully concluded and the data confirm that solithromycin’s interactions with CYP3A4, an enzyme in the liver that metabolizes a number of drugs, are consistent with older macrolides’ interactions with CYP3A4.

Phase 2 Trial in Gonorrhea.Emerging resistance to available therapies, including oral and injectible cephalosporins and azithromycin, has resulted in an urgent medical need for new therapies for gonorrhea. Solithromycin, a new fourth generation macrolide with three ribosomal binding sites, has greater in vitro potency against gonococci than azithromycin and is active against most azithromycin- and cephalosporin-resistant strains. We have completed a phase II study to evaluate the efficacy and safety of single-dose oral solithromycin for treatment of patients with gonorrhea. Patients with suspectedNeisseria gonorrhoeae infection were enrolled. Consenting eligible patients received a single oral dose of 1200 mg solithromycin. All patients were cultured forN. gonorrhoeae in the urethra/cervix, rectum, and pharynx at enrollment and Day 7. The primary outcome was bacterial eradication as measured by conversion from positiveN. gonorrhoeae baseline urethral or cervical culture to negative at Day 7. Secondary outcomes included eradication of rectal or pharyngeal gonorrhea. In October 2012, we reported that gonococcal eradication rates in 22 evaluable patients (of 28 patients enrolled at that time) who had culture proven gonorrhea, were 100% (22/22) for urethral/cervical infections. Eradication rates were also 100% for rectal (2/2) and pharyngeal (5/5) infections. Susceptibility data from 25 isolates show the median MIC (range) for solithromycin was 0.06 µg/mL (0.015–0.125). Solithromycin was generally well-tolerated, with mild gastrointestinal AEs common (86%; 24/28). The most common AE was mild diarrhea (61%; 17/28) followed by mild nausea (32%; 9/28). Based on these results, a single 1200 mg dose of solithromycin appears to be well tolerated and effective in eradicatingN. gonorrhoeae. Since 100% efficacy was achieved with 1200 mg, we are continuing to test 1000 mg to determine the optimum effective dose.

9

Table of Contents

Pre-Clinical Data

Our pre-clinical studies support four of the key attributes of solithromycin: potency against a broad range of bacteria, potential to have a low incidence of resistance, intracellular activity and anti-inflammatory qualities associated with macrolides.

Potency. We have extensively studied solithromycin’sin vitro activity and potency against a variety of respiratory and non-respiratory bacteria. solithromycin was tested against clinical isolates including pneumococci,Hemophilus, Legionella, Moraxella, Chlamydia, Neisseria, beta-hemolytic streptococci, Mycoplasma, S. aureus (including MRSA), coagulase negative staphylococci, enterococci and many other bacteria. These studies found that solithromycin exhibited two to four times greater potency compared to Ketek, and superior potency compared to other macrolides against most bacteria causing CABP. In another study, solithromycin demonstrated superior activity against several serotypes ofLegionella pneumophila compared to other macrolides, particularly erythromycin and azithromycin, which are commonly used to treat Legionellosis.Legionella are atypical bacteria and are not susceptible to penicillins and cephalosporins commonly used to treat CABP, but are susceptible to fluoroquinolones such as levofloxacin. The results of these studies are presented in Table 4 below. Potency against a panel of bacterial strains is measured by MIC90, which refers to the concentration needed to inhibit the growth of 90% of a panel of bacterial strains isolated from patients. A lower MIC90 indicates greater potency against a particular bacterium.

Table 4. Solithromycin Pre-Clinical Data: Solithromycinin vitro Activity Against CABP Bacteria.

Organism (# strains tested) | Solithromycin MIC90 (µg/ml) | Azithromycin MIC90 (µg/ml) | Levofloxacin MIC90 (µg/ml) | Amox/Clav MIC90 (µg/ml) | ||||||||||||

Streptococcus pneumoniae (150) | 0.25 | >16 | 1.0 | >8 | ||||||||||||

Streptococcus pyogenes (100) | 0.03 | >16 | 1.0 | 0.25 | ||||||||||||

Hemophilus influenzae (100) | 2 | 2 | 0.12 | 2.0 | ||||||||||||

Legionella pneumophila (30) | 0.015 | 2 | 0.5 | NE | ||||||||||||

Mycoplasma pneumoniae (36) | 0.000125 | 0.0005 | 0.5 | NE | ||||||||||||

Chlamydophila pneumoniae (10) | 0.25 | 0.125 | NT | NE | ||||||||||||

NE = Not effective, as the target of these antibiotics do not exist in these pathogens.

NT = Not tested.

Resistance. Solithromycin was tested against pneumococcal strains that have become resistant to older macrolides as a result of mutations callederm(B), mef(A), a combination oferm(B)with mef(A), and L4 mutations. As shown by thein vitro potency data in Table 5 below, solithromycin was active against all tested pneumococcal strains that are resistant to older macrolides.

Table 5. Solithromycin Pre-Clinical Data: MIC50 and MIC90 Values (µg/ml) of Pneumococci with Defined Macrolide-Resistant Mechanism.

Drug | erm(B) (54) | mef(A) (51) | erm(B) + mef(A) (31) | L4 mutations (27) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| MIC50 | MIC90 | MIC50 | MIC90 | MIC50 | MIC90 | MIC50 | MIC90 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

Solithromycin | 0.03 | 0.5 | 0.03 | 0.125 | 0.125 | 0.25 | 0.06 | 0.125 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

azithromycin | >64 | >64 | 4 | 8 | >64 | >64 | >64 | >64 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

telithromycin | 0.06 | 1 | 0.125 | 0.25 | 0.5 | 1 | 0.125 | 0.25 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

clindamycin | >64 | >64 | 0.06 | 0.06 | 0.06 | >64 | 0.06 | 0.125 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

amox/clav | 0.5 | 8 | 0.125 | 2 | 2 | 8 | 4 | 8 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

levofloxacin | 1 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 16 | 1 | 2 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

penicillin G | 1 | 4 | 0.125 | 4 | 2 | 4 | 4 | 16 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

The ability to become resistant to solithromycin was analyzed by exposing eight pneumococcal bacterial strains from the above study to solithromycin. Only one strain which was already resistant to the older macrolides and wereerm andmef strains developed a high-level resistance to solithromycin and only after 18 passes. This suggests that selection of resistant strains would be infrequent and additional mutations are necessary for resistance to develop to solithromycin.

We also tested a number of Group A beta-hemolytic streptococci that have become resistant to older macrolides. The data indicate that solithromycin is active against these organisms, which have different mechanisms of resistance, including erm(B), mef(A) and erm(A). The frequency of resistance was low at <10-10, but importantly there was no cross-resistance with these organisms once they had become resistant to older macrolides. Solithromycin is active against all these resistant strains. While the strains are resistant to older generations of macrolides, no strains resistant to solithromycin could be isolated after 50 transfers in a growth medium containing solithromycin.

10

Table of Contents

We have continued to study global susceptibility and resistance patterns against relevant pathogens in CABP and tested solithromycin against pathogens collected in 2011 from respiratory tract infections. Solithromycin displayed coverage against 100.0% ofS. pneumoniaestrains (2,418 strains collected from the U.S. and Europe) at£1 µg/mL (a level which is achievable in the plasma and tissues). The MIC90 againstS. pneumoniaewas 0.12 µg/mL in these studies. Resistance rates in the U.S. to macrolides have been noted to increase from previous results to 44% in 2012. The activity of solithromycin against other respiratory tract associated pathogens, such asH. influenzae andM. catarrhalis, was stable during four consecutive surveillance years (2008-2011). We believe this confirms that solithromycin could be a promising antibiotic for treatment of bacterial pathogens causing respiratory tract and other infections.

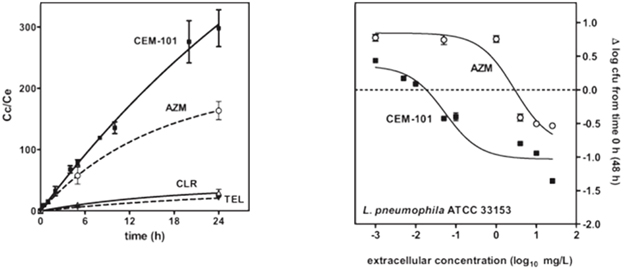

Intracellular Activity. Bacteria that cause infections can be inside cells or in tissue. During treatment if the antibiotic does not penetrate into tissues and cells, the bacteria can escape the effect of the antibiotic. Consequently, it is important that antibiotics be distributed from the blood to the tissues and intracellularly. Macrolides have been known to be effective against intracellular bacteria, which is one of their advantages. solithromycin accumulates to concentrations that are several times higher than azithromycin, as shown below in Figure 1a, and the intracellular drug is potent against intracellular bacteria and is more active than azithromycin in killing intracellular pathogens such as Legionella pneumophila as shown in Figure 1b.

| Figure 1a: Concentration after Exposure of Macrophages to Azithromycin and Solithromycin in Macrophages | Figure 1b: Killing of Legionella Located Intracellularly by Azithromycin and Solithromycin |

Anti-Inflammatory Properties. We conducted studies comparing solithromycin’s anti-inflammatory properties to older macrolides. solithromycin was more effective than the older macrolides in decreasing the production of cytokines, which are cell-signaling molecules involved in the process of inflammation. Reduction of cytokine activity would be expected to reduce inflammation and resulting tissue damage. Thus, solithromycin is expected to be effective in eradicating the infecting bacteria and reducing the inflammation resulting from the infection, which should result in a faster recovery. Older generation macrolides have also been used in the treatment of diseases like late-stage COPD and CF because of their anti-inflammatory properties. Our pre-clinical data suggest solithromycin could also be used in the treatment of these diseases.

In addition, investigators at the University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill, through funding from the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, or NIAID are for studying solithromycin’s mucin inhibitory properties and ability to restore lung physiology in cystic fibrosis model systems.

Planned Clinical Trials

We have initiated our pivotal trial program, which we believe will require two Phase 3 trials, including one trial with oral solithromycin and one trial with IV solithromycin stepping down to oral solithromycin for the approval of both IV and oral products under one NDA. The FDA’s Anti-Infective Drugs Advisory Committee (AIDAC) convened in November 2011 to review anticipated

11

Table of Contents

changes in guidance to the industry for conducting clinical trials for CABP. The proposed guidance follows several FDA advisory meetings as well as recommendations of an independent advisory body called the FNIH that involved industry and academic infectious disease physicians. According to the newly proposed guidelines, the primary endpoint for Phase 3 CABP trials will be clinical success at an early timepoint (Day 3-5 post study drug initiation). Clinical success is defined as improvement in at least two of the following symptoms: cough, shortness of breath, chest pain, and sputum production, without worsening in any other symptom. The proposed guidelines also clarify the patient population required for these trials by specifying the percent of patients to be enrolled based on the severity of their disease. For example, the new guidelines specify that up to 50% of patients in oral CABP trials can have moderate CABP, with the remainder having more severe disease. IV CABP trials can have up to 25% of patients with moderate CABP while the rest must have more severe CABP. For those seeking FDA approval by establishing non-inferiority, the guidance specifies that companies conduct adequate and well controlledPhase 3 CABP trials, with a requirement to demonstrate non-inferiority in early clinical response rate (in comparison to the comparator drug) in the Intent-to-Treat population of each study, using a 10% non-inferiority margin. In addition, non-inferiority must be demonstrated in the pooled (across both studies) microbiological-Intent-to-Treat population. We have designed our Phase 3 trial program to meet these FDA guidelines. For our Phase 3 trial for oral solithromycin, we requested and were allowed to includeMycoplasma pneumoniae, a CABP pathogen, within the mITT and ME scores. We also requested and were allowed to use PCR based rapid diagnostics for CABP pathogens (Curetis) to support our mITT and ME data. The study was initiated in the fourth quarter of 2012.

The Phase 3 trials will be randomized, double-blinded studies conducted against a comparator drug agreed upon with the FDA, for which we will have to show non-inferiority from an efficacy perspective and acceptable safety and tolerability. Using feedback received from the FDA, we began the Phase 3 trial with oral solithromycin in December 2012. We expect to receive top line data for that trial in the first half of 2014.

In October 2012, we reported results from our Phase 1 trial for the IV formulation of solithromycin in which we demonstrated that IV solithromycin was well tolerated, showed a favorable pharmacokinetic (PK) profile and achieved relevant plasma concentrations. Based on this study, we have selected a therapeutic dose of 400 mg administered once daily for up to seven days for the Phase 3 IV-to-oral step down trial. We are planning the second pivotal study, a Phase 3 IV-to-oral step down study for the treatment of moderate to moderately severe CABP. We plan to request, in the first quarter of 2013 an end of Phase 2 meeting with the FDA. This is a key meeting that should define the expectations for the NDA for the IV and oral formulations of solithromycin. The FDA can take up to 60 days to conduct this meeting. We plan to finalize the overall development program for solithromycin for CABP with the FDA at this meeting, which we expect will occur in the first half of 2013. We plan to initiate the trial in the second half of 2013, subject to available resources.

In addition, we intend to conduct a number of studies to support FDA approval, including a thorough QT, or TQT, study to look at cardiac effects, and studies in patients with hepatic insufficiency and renal impairment.

We are exploring the possibility for funding pediatric studies for solithromycin in a range of indications for CABP through the Biomedical Advanced Research and Development Authority, or BARDA, an agency of U.S. Department of Health and Human Services.

Solithromycin as a Treatment for Bacterial Urethritis. We have demonstrated that solithromycin has in vitro activity against a broad spectrum of pathogens that cause bacterial urethritis, includingN. gonorrhoeae, Chlamydia trachomatis, Mycoplasma genitalium, Ureaplasma urealyticum etc. In our Phase 2 study, we have demonstrated to date that solithromycin is effective in treating gonococcal urethritis/cervicitis, and pharyngeal and rectal gonococcal infections. The CDC no longer recommends oral cefixime to be used in the treatment of gonorrohea and the recommended treatment is intramuscular injection of ceftriaxone. Resistance to ceftriaxone has been reported. There is no oral antibiotic currently recommended for treating gonorrhea as well as for treatment of sexual partners of infected patients. This need has become a public health crisis and the WHO and U.S. government are looking for alternative treatments. We are discussing possible grant funding opportunities with the NIAID to pursue solithromycin in a pivotal Phase 3 trial for the treatment of bacterial urethritis, primarily gonnorhea.

Potential Biodefense Application for Solithromycin. Solithromycin is active against bioterror threat pathogens such asB. anthracis, Yersinia pestisand Francisella tularensis. In order to explore the potential for its use to provide broad protection in a bioterror threat, we are exploring the possibility for funding studies on solithromycin through BARDA.

Taksta (Fusidic Acid)

Overview

Taksta, our fusidic acid product candidate, is an oral antibiotic that we are developing in the U.S. for the treatment of prosthetic joint infections, which are frequently caused bystaphylococci, including coagulase-negative and coagulase-positive staphlycocci and MRSA. Fusidic acid is the only member of a unique class of antibiotics, called fusidanes, and has a mechanism of action that differs from any other antibiotic. Fusidic acid has been approved and sold for several decades in Europe and other countries outside the U.S. and has a long-established safety and efficacy profile, but has never been approved in the U.S. We have conductedin vitrotests of

12

Table of Contents

Taksta’s activity against thousands of strains ofS. aureus found in the U.S. and our data show that virtually all of those strains tested (99.6%) are susceptible to Taksta. In addition, we believe Taksta has the potential to be used in hospital and community settings on both a short-term and chronic basis. Our completed Phase 2 clinical study has shown Taksta to be comparably effective to linezolid, a treatment for the common skin infectionS. aureus and the only oral antibiotic approved by the FDA to treat MRSA.

Taksta Market Opportunity

According to a survey of physicians conducted by Decision Resources,Staphylococcus aureus, including MRSA, is the most important pathogen of concern in patients with osteomyelitis and prosthetic joint infection. The other major pathogen involved in PJI is coagulase-negative staphlycocci. Bone infections generally begin with bacteria that reside on the skin and enter the bloodstream through breaks in the skin or mucous membrane that occur as a result of a wound or due to a surgical, medical or dental procedures. According to the IDSA, MRSA infections account for approximately 60% of skin infections seen in U.S. emergency rooms. The most common treatments for prosthetic joint infection with MRSA currently are vancomycin (available as a generic) and sometimes daptomycin (sold under the brand name Cubicin®), both of which are available only as IV formulations for systemic infections. Linezolid, which is also prescribed for prosthetic joint infections, is available in both IV and oral formulations and is the only oral antibiotic approved by the FDA for MRSA. Linezolid, however, has significant side effects, which include irreversible peripheral neuritis, or the inflammation of nerves and thrombocytopenia, or a relative decrease of platelets in blood. It is recommended that linezolid not be taken for more than 14 days without additional monitoring because of the increased possibility of these side effects. In addition, on July 26, 2011, the FDA published a drug safety communication letter regarding the use of linezolid in patients on serotonergic drugs such as SSRIs (including Prozac, Paxil and Zoloft), which are taken for depression, bipolar disease, schizophrenia and other psychiatric disorders. Given the widespread use of SSRIs and some of the other side effects associated with linezolid, we do not believe that linezolid is an option for many patients. We believe there is an opportunity to develop an oral drug that is effective against MRSA and has a safety profile that supports out-patient use, use for chronic indications and use in children.

In 2006, nearly 800,000 total knee or hip arthroplasty procedures were performed in the U.S., with an overall infection rate of approximately 1.0%. It has been predicted that the demand for knee revision surgery will double by 2015, and increase by 673% by the year 2030 as the population ages. With steadily increasing numbers of patients in the U.S. undergoing prosthetic joint surgery, we expect there will be a corresponding increase in the overall incidence of prosthetic joint infections. Prosthetic joint infections usually occur when bacteria enter the area of the prosthesis during implantation. However, they may also occur through other surgical, medical or dental procedures or by accident when the skin or mucous membrane is broken, enabling surface-level bacteria to travel to the prosthesis.S. aureus species, including MRSA, are the most commonly identified bacterial pathogens involved in prosthetic joint infections.

The methods for the treatment for PJI are variable depending on the severity of the infection and the patient’s condition. The infected prosthesis could be saved or could be replaced. The antibiotics used to treat these infections depend on the pathogens involved. Staphylococci are the most frequently identified pathogen in PJI. IDSA has recently issued guidelines for the treatment of PJI (Osmon, et al., 2013). In almost all cases intravenous vancomycin is administered for two to eight weeks, in combination with oral antibiotics such as rifampin, ciprofloxacin, levofloxacin, cefazolin, clindamycin or Bactrim. The choice of the oral antibiotic is dependent on whether the staphylococcus is MRSA. Rifampin is commonly used as its use has been noted to have better outcome. Two-stage revision replacement of an infected prosthesis is most commonly practiced in the U.S. It has been noted that greater than 85% success could be achieved by two-stage revision versus 45% success rate if the prosthesis is retained. These results are in the U.S. where fusidic acid is not available for use. In the two-stage method of treatment, the infected prosthesis is removed, an antibiotic impregnated spacer is installed and the patient is then treated with IV vancomycin for four to six weeks. After that time, the antibiotic is stopped and after six weeks, the joint is cultured to determine if the infection is cleared and a new prosthesis is introduced. Thus, in the U.S., patients undergo at least two surgeries, several weeks of intravenous therapy, as well as oral antibiotics. In Europe and Australia, two-stage revision is less common and the strategy is to debride and treat with intravenous vancomycin and oral rifampin for one to four weeks followed by oral rifampin plus fusidic acid for three months to one to two years. Other oral antibiotics have been used with less success. In the U.S., the debride and retention method is less often used in PJI patients, but when used in these patients, chronic suppression is used for years with a combination of intravenous and oral antibiotics and the treatment is often a failure. According to Data Monitor, physicians indicate that safety is a significant factor for them in choosing antibiotic therapy for osteomyelitis and prosthetic joint infections because the population of patients receiving prosthetic joints tends to be older and the treatment duration is longer. As a result, we believe there is a significant opportunity for a treatment for prosthetic joint infection that is effective against staphylococci, including MRSA, and can be used safely on a long-term basis. Outside of the U.S., fusidic acid has been used successfully in combination with rifampin to achieve high cure rates in selected patients with prosthetic joint infections, without requiring replacement of the prosthesis. In a recent review of clinical experience at an Australian teaching hospital, as well as in the Swiss teaching hospital, treatment of staphylococcal prosthetic joint infection with debridement, prosthesis retention, and oral fusidic acid and rifampin therapy achieved an approximately 88% treatment success rate at one year.

13

Table of Contents

Key Attributes of Taksta

We believe Taksta can be an effective treatment for prosthetic joint infections because of the following key attributes.

Taksta has an established safety profile outside the U.S. Fusidic acid has been approved and used in certain countries in Europe and in Australia for many years, in some countries as many as 40 years, both for short-term use in complicated skin infections as well as for long-term use in other types of infections requiring long-term therapy, including osteomyelitis and prosthetic joint infections. Further, fusidic acid has been used in pediatric populations outside the U.S. and has been safe and well tolerated. As fusidic acid has been in clinical use outside the U.S. for several decades, a substantial body of safety data is in the public domain. Safety data from over 100 published clinical study results involving the oral administration of fusidic acid to over an aggregate of 4,000 patients demonstrated a safety profile consistent with non-U.S. approved product labeling. These data indicate significant worldwide use of fusidic acid, capture clinical experience in the public domain and characterize the safety profile of fusidic acid. The safety data from our Phase 1 and Phase 2 clinical trials are consistent with available historical data and establish that Taksta has a favorable safety and tolerability profile.

Taksta has demonstrated comparable efficacy to the only FDA-approved oral treatment for MRSA. In a Phase 2 trial in 155 ABSSSI patients comparing Taksta to linezolid, Taksta successfully demonstrated efficacy comparable to linezolid and confirmed its effectiveness againstS. aureus and MRSA. Furthermore,in vitro data have demonstrated that Taksta has potent activity against more than 7,300 strains ofS. aureus, including MRSA strains that are community-acquired MRSA, or CA-MRSA, hospital-acquired MRSA, or HA-MRSA, and other known types of MRSA. We have also conducted tests of Taksta’s activity against strains ofS. aureusthat are found in the U.S. and our data show that virtually all of those strains (99.6%) are susceptible to Taksta. As a result of Taksta’s broad range of activity againstS. aureus, physicians could use Taksta to treat a patient with an infected wound or cellulitis without identifying the particular type ofS. aureuscausing the infection. Since fusidic acid has a unique structure and target, there is no known cross-resistance with other antibiotics.

Taksta is an oral therapy for all types of S. aureus, including MRSA. The leading treatments for prosthetic joint infections and ABSSSI caused by MRSA are available only in IV formulations. Linezolid is the only drug currently approved for use against MRSA with an oral formulation. However, its use is associated with serious side effects and cannot be used in certain patient populations without additional monitoring. We believe our clinical studies and historical data on fusidic acid demonstrate that Taksta has the potential to be a safe and effective oral treatment for prosthetic joint infections and ABSSSI caused by MRSA. We believe Taksta would enable physicians to treat patients not otherwise needing hospitalization on an outpatient basis, thereby reducing hospitalization costs and avoiding the unnecessary introduction of resistant bacteria into the hospital setting.

Taksta has a lower incidence of resistance due to our proprietary loading dose regimen. Ourin vitro studies have shown that the reason for resistance to fusidic acid that was reported to occur during oral treatment outside the U.S. is that it was not dosed optimally. In addition, published studies of resistance during oral treatment with fusidic acid outside the U.S. conclude that the frequency of resistance is related to the lack of initial potency, which has been addressed in the past by combination therapy. Our innovative loading dose regimen minimizes the development of resistance by increasing the amount of drug initially delivered to the bacteria.

Taksta can be used in patient populations not well served by current treatments. We believe Taksta could also be used for patients that are anemic, as well as patients on serotonergic drugs such as SSRIs who could be treated with an oral antibiotic, but for whom linezolid may not be a viable or convenient treatment option due to side effects and/or increased monitoring requirements. In addition, none of the antibiotics currently on the market can be used for prolonged periods of time to treat chronic staphylococcal infections due to safety concerns. We believe Taksta could fulfill the need for a safe, long-term oral therapy to treat chronic infections such as prosthetic joint infections and osteomyelitis. Furthermore, there are few treatment options for children infected withS. aureus, especially MRSA, because in children, IV antibiotics have unpredictable blood levels and are inconvenient to dose. Fusidic acid is available in an oral formulation and has been used in pediatric populations outside the U.S. We intend to develop a pediatric formulation of Taksta to address the need for a safe and effective oral treatment of staphylococci and streptococci in children.

Clinical Data

Fusidic acid has been used outside the U.S. for approximately four decades. However, fusidic acid has never been approved in the U.S. As a result, we must demonstrate that Taksta is active against current strains of staph, including MRSA, that are responsible for infections in the U.S., as well as to show that it is well tolerated at the dosing regimen that we are developing.

Phase 2 Clinical Trial. We have successfully completed a Phase 2 clinical trial in ABSSSI, comparing Taksta to linezolid, which is the only oral antibiotic approved by the FDA for treating MRSA infections. The trial demonstrated that our Taksta loading dose regimen has a favorable safety and tolerability profile with efficacy comparable to linezolid. In this study, patients were stratified by the type of infection, such as wounds and cellulitis, and, through the first 127 patients, were randomized in a 1:1:1 ratio to receive a

14

Table of Contents