UNITED STATES

SECURITIES AND EXCHANGE COMMISSION

Washington, D.C. 20549

FORM 10-K

(Mark One)

☒ | ANNUAL REPORT PURSUANT TO SECTION 13 OR 15(d) OF THE SECURITIES EXCHANGE ACT OF 1934 |

For the fiscal year ended December 31, 2020

OR

☐ | TRANSITION REPORT PURSUANT TO SECTION 13 OR 15(d) OF THE SECURITIES EXCHANGE ACT OF 1934 FOR THE TRANSITION PERIOD FROM TO |

Commission File Number 001-39661

ATEA PHARMACEUTICALS, INC.

(Exact name of Registrant as specified in its Charter)

Delaware | 46-0574869 |

(State or other jurisdiction of incorporation or organization) | (I.R.S. Employer Identification No.) |

125 Summer Street Boston, MA | 02110 |

(Address of principal executive offices) | (Zip Code) |

Registrant’s telephone number, including area code: (857) 284-8891

Securities registered pursuant to Section 12(b) of the Act:

Title of each class | | Trading Symbol(s) | | Name of each exchange on which registered |

Common Stock, $0.001 par value per share | | AVIR | | The Nasdaq Global Select Market |

Securities registered pursuant to Section 12(g) of the Act: None

Indicate by check mark if the Registrant is a well-known seasoned issuer, as defined in Rule 405 of the Securities Act. YES ☐ NO ☒

Indicate by check mark if the Registrant is not required to file reports pursuant to Section 13 or Section 15(d) of the Act. YES ☐ NO ☒

Indicate by check mark whether the Registrant: (1) has filed all reports required to be filed by Section 13 or 15(d) of the Securities Exchange Act of 1934 during the preceding 12 months (or for such shorter period that the Registrant was required to file such reports), and (2) has been subject to such filing requirements for the past 90 days. YES ☒ NO ☐

Indicate by check mark whether the Registrant has submitted electronically every Interactive Data File required to be submitted pursuant to Rule 405 of Regulation S-T (§232.405 of this chapter) during the preceding 12 months (or for such shorter period that the Registrant was required to submit such files). YES ☒ NO ☐

Indicate by check mark whether the registrant is a large accelerated filer, an accelerated filer, a non-accelerated filer, a smaller reporting company, or an emerging growth company. See the definitions of “large accelerated filer,” “accelerated filer,” “smaller reporting company,” and “emerging growth company” in Rule 12b-2 of the Exchange Act.

Large accelerated filer | | ☐ | | Accelerated filer | | ☐ |

| | | |

Non-accelerated filer | | ☒ | | Smaller reporting company | | ☐ |

| | | | | | |

Emerging growth company | | ☒ | | | | |

If an emerging growth company, indicate by check mark if the registrant has elected not to use the extended transition period for complying with any new or revised financial accounting standards provided pursuant to Section 13(a) of the Exchange Act. ☐

Indicate by check mark whether the registrant has filed a report on and attestation to its management’s assessment of the effectiveness of its internal control over financial reporting under Section 404(b) of the Sarbanes-Oxley Act (15 U.S.C. 7262(b)) by the registered public accounting firm that prepared or issued its audit report. ☐

Indicate by check mark whether the Registrant is a shell company (as defined in Rule 12b-2 of the Act). YES ☐ NO ☒

The registrant was not a public company as of the last business day of its most recently completed second fiscal quarter and, therefore, cannot calculate the aggregate market value of its voting and non-voting common equity held by non-affiliates as of such date.

The number of shares of Registrant’s Common Stock outstanding as of March 29, 2021 was 82,736,937.

DOCUMENTS INCORPORATED BY REFERENCE

Portions of the registrant’s definitive proxy statement for its 2021 Annual Meeting of Stockholders, which the registrant intends to file with the Securities and Exchange Commission within 120 days after the end of the registrant’s fiscal year ended December 31, 2020, are incorporated by reference into Part III of this Annual Report on Form 10-K.

Table of Contents

i

SPECIAL NOTE REGARDING FORWARD-LOOKING STATEMENTS

This Annual Report on Form 10-K contains forward-looking statements. We make such forward-looking statements pursuant to the safe harbor provisions of the Private Securities Litigation Reform Act of 1995 and other federal securities laws. Forward-looking statements are neither historical facts nor assurances of future performance. Instead, they are based on our current beliefs, expectations and assumptions regarding the future of our business, future plans and strategies, our clinical results and other future conditions. The words “aim,” “anticipate,” “believe,” “contemplate,” “continue,” “could,” “estimate,” “expect,” “goal,” “intend,” “may,” "on track," “plan,” “possible,” “potential,” “predict,” “project,” “seek,” “should,” “target,” “will,” “would” or the negative of these terms or other similar expressions are intended to identify forward-looking statements, although not all forward-looking statements contain these identifying words.

These forward-looking statements include, among other things, statements about:

| • | our expectations relating to clinical trials for our product candidates, including projected costs, study designs or the timing for initiation, recruitment, completion, or reporting top-line data; |

| • | the potential therapeutic benefits of our product candidates and the potential indications and market opportunities therefor; |

| • | the safety profile and related adverse events of our product candidates; |

| • | our plans to research, develop and commercialize our current and future product candidates; |

| • | the potential benefits of our collaboration with Roche or any future collaboration we may enter into with Roche or others; |

| • | the timing of and our ability to obtain and maintain regulatory approvals for our product candidates; |

| • | the rate and degree of market acceptance and clinical utility of any products for which we may receive marketing approval; |

| • | our commercialization, marketing and manufacturing capabilities and strategy; |

| • | our estimates regarding future revenue, expenses and results of operations; |

| • | the progress of, timing of and amount of expenses associated with our research, development and commercialization activities; |

| • | our future financial position, capital requirements and needs for additional financing; |

| • | developments relating to our competitors, competing treatments and vaccines and our industry; |

| • | our expectations regarding federal, state and foreign laws and regulations; |

| • | our ability to attract, motivate, and retain key personnel; and |

| • | the impact of COVID-19 on our business, including our preclinical studies and clinical trials. |

These forward-looking statements are based on management’s current expectations. These statements are neither promises nor guarantees, but involve known and unknown risks, uncertainties and other important factors that may cause our actual results, performance or achievements to be materially different from any future results, performance or achievements expressed or implied by the forward-looking statements. Factors that may cause actual results to differ materially from current expectations include the initiation, execution and completion of clinical trials, uncertainties surrounding the timing of availability of data from our clinical trials, ongoing discussions with and actions by regulatory authorities, our development activities and those other factors we discuss in Part I, Item 1A. “Risk Factors.” You should read these factors and the other cautionary statements made in this report as being applicable to all related forward-looking statements wherever they appear in this report. These risk factors are not exhaustive and other sections of this report may include additional factors which could adversely impact our business and financial performance. Given these uncertainties, you should not rely on these forward-looking statements as predictions of future events. Except as required by law, we assume no obligation to update or revise these forward-looking statements for any reason, even if new information becomes available in the future.

As used in this Annual Report on Form 10-K, unless otherwise specified or the context otherwise requires, the terms “we,” “our,” “us,” the “Company” refer to Atea Pharmaceuticals, Inc. and its subsidiary. All brand names or trademarks appearing in this Annual Report on Form 10-K are the property of their respective owners.

ii

SUMMARY RISK FACTORS

Our business is subject to numerous risks and uncertainties, including those described in Part I, Item 1A. “Risk Factors” in this Annual Report on Form 10-K. The principal risks and uncertainties affecting our business include the following:

| • | There is significant uncertainty around our development of AT-527 as a potential treatment for COVID-19. |

| • | We are highly dependent on our management, directors and other key personnel. |

| • | We may expend resources in anticipation of potential clinical trials and commercialization of AT-527, which we may not be able to recover if AT-527 is not approved for the treatment of COVID-19 or we are not successful at commercializing AT-527. |

| • | The market for therapeutics for the treatment of COVID-19 may be reduced, perhaps significantly, if vaccines are effective and widely accepted. |

| • | AT-527 may face significant competition from other treatments for COVID-19 that are currently marketed or are in development. |

| • | The COVID-19 pandemic may materially and adversely affect our other business opportunities and financial results. |

| • | We have a limited operating history and no history of successfully developing or commercializing any approved antiviral products, which may make it difficult to evaluate the success of our business to date and to assess the prospects for our future viability. |

| • | We have incurred significant losses since inception. We expect our expenditures will increase for the foreseeable future. We have no products that have generated any commercial revenue and we may never achieve or maintain profitability. |

| • | We will require substantial additional financing, which may not be available on acceptable terms, or at all. A failure to obtain this necessary capital when needed could force us to delay, limit, reduce or terminate our product development or commercialization efforts. |

| • | Our ability to use our net operating loss carryforwards and other tax attributes to offset future taxable income may be subject to certain limitations. |

| • | Our business is highly dependent on the success of our most advanced product candidates. If these product candidates fail in preclinical or clinical development, do not receive regulatory approval or are not successfully commercialized, or are significantly delayed in doing so, our business will be harmed. |

| • | The regulatory approval processes of the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (“FDA”) and comparable foreign regulatory authorities are lengthy, expensive, time-consuming, and inherently unpredictable. If we are ultimately unable to obtain regulatory approval for our product candidates, we will be unable to generate product revenue and our business will be seriously harmed. Even if we complete the necessary preclinical studies and clinical trials, the marketing approval process is expensive, time-consuming and uncertain and may prevent us, our current collaboration partner, Roche, or any future collaboration partners from obtaining approvals for the commercialization of any product candidate we develop. |

| • | Clinical development is lengthy and uncertain. We may encounter substantial delays and costs in our clinical trials, or may not be able to conduct or complete our clinical trials on the timelines we expect, if at all. |

| • | Our product candidates may be associated with serious adverse events, undesirable side effects or have other properties that could halt their clinical development, prevent their regulatory approval, limit their commercial potential or result in significant negative consequences. |

iii

| • | We currently conduct clinical trials, and may in the future choose to conduct additional clinical trials, of our product candidates in sites outside the United States, and the FDA may not accept data from trials conducted in foreign locations. |

| • | Interim, topline and preliminary data from our clinical trials that we announce or publish from time to time may change as more data become available and are subject to audit and verification procedures that could result in material changes in the final data. |

| • | We may not be successful in our efforts to identify and successfully develop additional product candidates. |

| • | Risks related to healthcare laws and other legal compliance matters may materially and adversely affect our business and financial results. |

| • | Risks related to commercialization may materially and adversely affect our business and financial results. |

| • | Risks related to manufacturing and our dependence on third parties may materially and adversely affect our business and financial results. |

| • | Risks related to intellectual property may materially and adversely affect our business and financial results, including if we are unable to obtain, maintain, enforce and adequately protect our intellectual property rights with respect to our technology and product candidates, or if the scope of the patent or other intellectual property protection obtained is not sufficiently broad, our competitors could develop and commercialize technology and products similar or identical to ours, and our ability to successfully develop and commercialize our technology and product candidates may be adversely affected. |

| • | We have only a limited number of employees which may be inadequate to manage and operate our business. |

| • | Our business and operations would suffer in the event of system failures, deficiencies or intrusions. |

| • | We will need to expand our organization, and we may experience difficulties in managing this growth, which could disrupt our operations. |

| • | We may engage in acquisitions or strategic partnerships that could disrupt our business, cause dilution to our stockholders, reduce our financial resources, cause us to incur debt or assume contingent liabilities, and subject us to other risks. |

| • | We or the third parties upon whom we depend may be adversely affected by natural disasters or other unforeseen events resulting in business interruptions and our business continuity and disaster recovery plans may not adequately protect us from such business interruptions. |

| • | Litigation against us could be costly and time-consuming to defend and could result in additional liabilities. |

| • | Unstable market and economic conditions may have serious adverse consequences on our business, financial condition and share price. |

| • | Risks related to our common stock may materially and adversely affect our stock price. |

| • | If we fail to maintain effective internal control over financial reporting and effective disclosure controls and procedures, we may not be able to accurately report our financial results in a timely manner or prevent fraud, which may adversely affect investor confidence in our company. |

| • | We could be subject to securities class action litigation. |

iv

PART I

Item 1. Business.

Overview

We are a clinical-stage biopharmaceutical company focused on discovering, developing and commercializing antiviral therapeutics to improve the lives of patients suffering from difficult to treat, life-threatening viral infections. Our current focus is on the development of product candidates to treat COVID-19, dengue, chronic hepatitis C (“HCV”), and respiratory syncytial virus (“RSV”).

Utilizing our team’s expertise from decades of developing innovative antiviral treatments we are advancing oral product candidates that are designed to be potent and selective, which we derived from our proprietary nucleotide platform that combine unique nucleotide scaffolds with novel double prodrugs for the purpose of inhibiting the enzymes central to viral replication. We believe that utilizing this double prodrug moiety approach allows us to maximize formation of the active metabolite, potentially resulting in oral antiviral product candidates that are selective for and highly effective at preventing replication of single stranded RNA (“ssRNA”), viruses while avoiding toxicity to host cells.

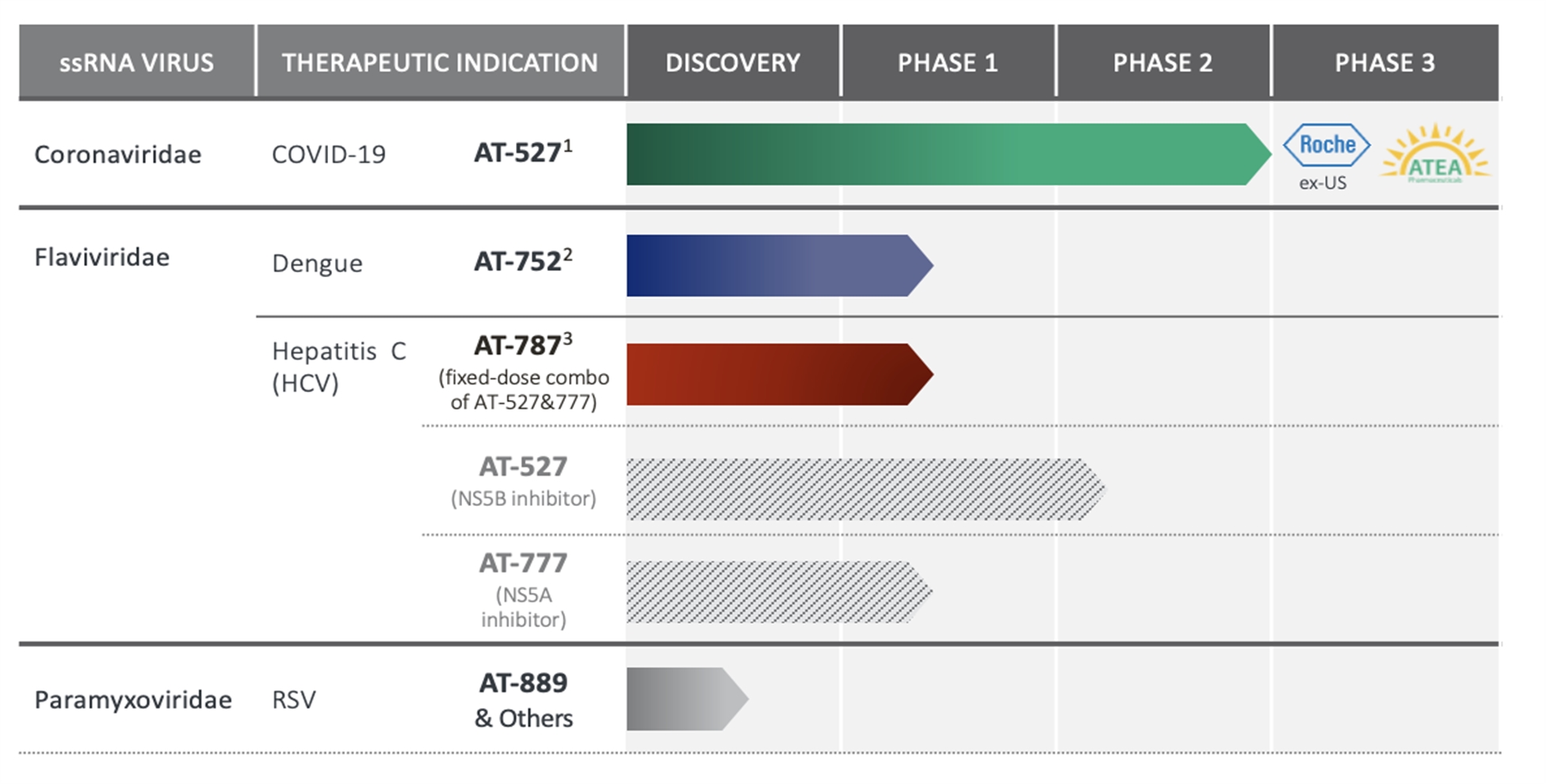

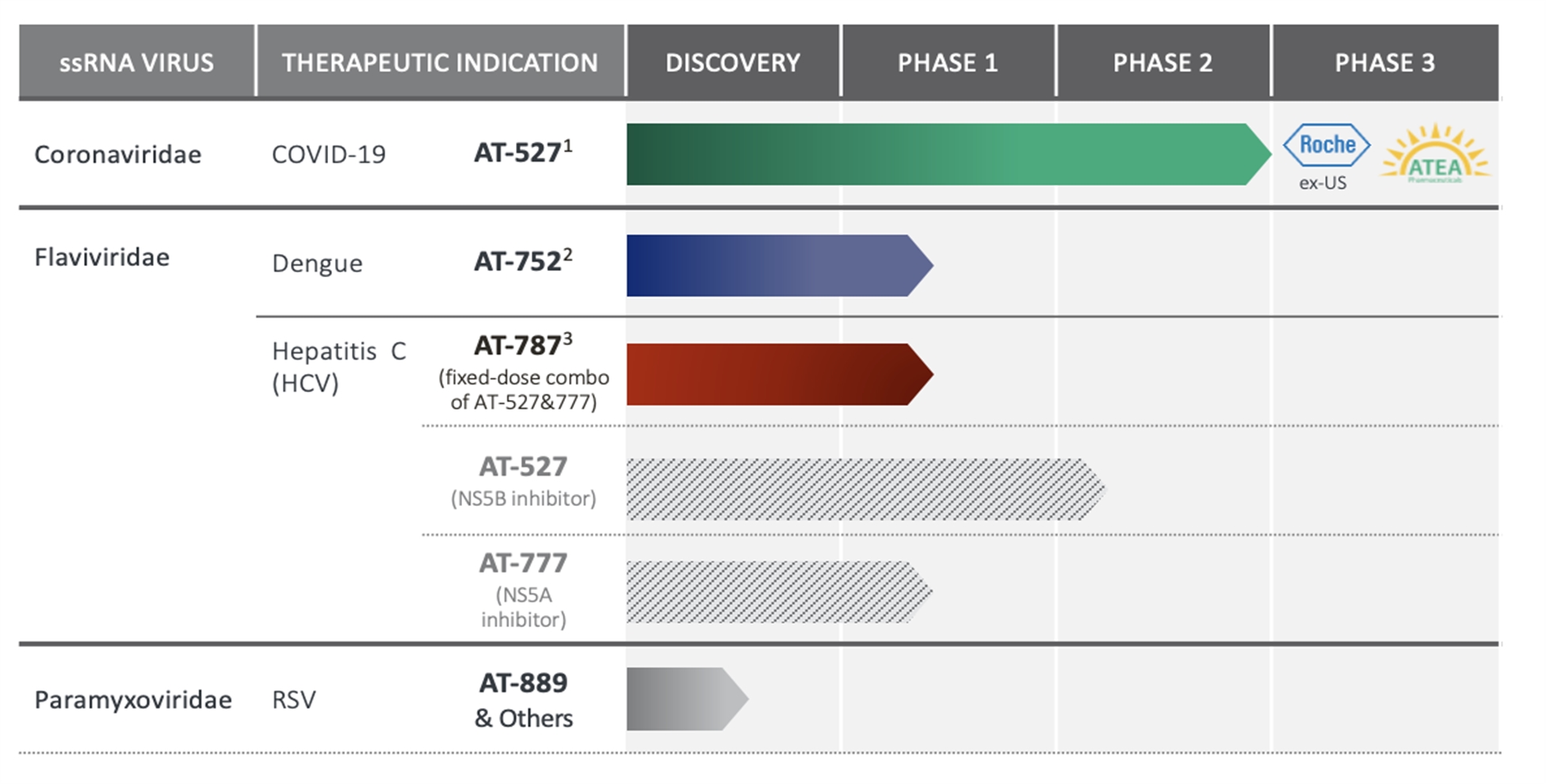

Our Development Pipeline

The following table summarizes our orally administered product candidate pipeline. All of our product candidates have been discovered and developed internally and we retain full global rights to commercialize our product candidates, other than certain ex-U.S. rights for our product candidate AT-527 licensed to F. Hoffmann-LaRoche Ltd. and Genentech, Inc. (together, “Roche”), under the License Agreement we entered into with Roche in October 2020 (the “Roche License Agreement”). We retain the right to commercialize all our product candidates in the United States.

1 Ex-US development and commercialization rights (other than for certain hepatitis C virus uses) licensed to Roche.

2 Rights to develop and manufacture globally and to commercialize in the US for dengue, among other viruses, retained. Ex-US commercialization of AT-752 for dengue is subject to agreement with Roche.

3 AT-787 is our selected product candidate for the treatment of HCV.

1

Our Technology Platform and Nucleosides Role in Antiviral Therapy

We have produced a large library of nucleoside and nucleotide prodrugs specifically designed to target viral RNA polymerase, a key enzyme that is encoded in the viral genome. All ssRNA viruses, including SARS-CoV-2, the virus that causes COVID-19, dengue and HCV, depend on viral RNA polymerase for replication and transcription and, since viral RNA polymerase is not present in the host cell, it is an ideal target to inhibit virus replication.

Over the last 40 years, nucleoside and nucleotide (together, “nucleos(t)ide”) analogs have been developed to mimic naturally occurring nucleic acids and block viral replication by inhibiting enzymes involved in RNA and DNA viral growth cycles. Nucleos(t)ide analogs have become the backbone of therapies that treat life-threatening viral infections, including human immunodeficiency virus (“HIV”) hepatitis B virus (“HBV”) and HCV.

COVID-19

The global pandemic of COVID-19, caused by SARS-CoV-2, has created significant disruption to public health and economic activity worldwide. As of March 29, 2021 there have been over 126.9 million confirmed cases of COVID-19 and 2.8 million deaths worldwide. Given our current expectation that SARS-CoV-2 is likely to become an endemic human coronavirus that has the potential to circulate in the human population for years, we believe that multiple COVID-19 preventive and therapeutic options will be needed.

At approximately one year into the pandemic, significant progress has been made with multiple vaccine and treatment options available. The treatment options include Veklury, or remdesivir, and dexamethasone, which are administered parenterally and have demonstrated benefit in hospitalized patients, and monoclonal antibody combinations, which are administered intravenously in high-risk patients.

Despite these advances, substantial need remains for new treatment options, particularly for orally administered treatments which would be more practical, convenient and efficient for use in the early stages of disease in an outpatient setting. We believe this is particularly true for patients with mild to moderate symptoms, which is the most frequent clinical presentation of the disease. Further, we believe that this need will continue for years, given that we expect there will be subsets of the population who will either refuse or fail to respond to available vaccines, or individuals for whom a vaccine is contraindicated, and who need treatment options to be available. An oral, direct acting antiviral that could be readily and easily administered in the outpatient setting would have the potential to significantly reduce disease burden and duration, prevent progression of disease or hospitalization, and have a significant impact on health systems globally. Additionally, an oral, direct acting antiviral with a mechanism of action that targets the inhibition of viral RNA polymerase, which is a highly conserved target site, could also be of particular value since the antiviral activity is expected to remain even in the presence of newly emerging variants.

Our product candidate for the treatment of patients with COVID-19 is AT-527, an orally administered, novel, direct acting antiviral. We, together with our collaborator Roche, anticipate initiating a Phase 3 clinical trial to study AT-527 in adult patients with mild or moderate COVID-19 in the outpatient setting in the second quarter of 2021. Currently, we are evaluating AT-527 for the treatment of patients with mild to moderate COVID-19 in two Phase 2 clinical trials. The first trial is a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled Phase 2 clinical trial in approximately 190 adult patients with moderate COVID-19 and one or more risk factors for poor outcomes in a hospitalized setting. We dosed our first patient in September 2020 and expect to report interim virology data from this clinical trial in the second quarter of 2021. The second trial, which is being conducted in collaboration with Roche, is a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled Phase 2 clinical trial in up to 220 adult patients with mild or moderate COVID-19 in an outpatient setting. The first patient in this trial was dosed in February 2021. We expect to report interim virology data from this trial in the second quarter of 2021. In addition, several Phase 1 clinical trials in healthy volunteers are planned in addition to the one currently being conducted and the one recently completed for which positive results have been announced.

2

Dengue

Dengue is a mosquito-borne viral infection that infects up to 400 million people a year, causing substantial public health and economic burden worldwide. Dengue, which is life threatening in severe cases, was traditionally considered a tropical disease, endemic to countries located mostly in the tropical regions of Asia, Latin America, the Pacific, and across Africa. However, in recent decades the incidence of the disease has been spreading globally. While a vaccine to prevent dengue is approved in some countries, it is indicated only for persons with confirmed prior dengue infection and its product label use is highly restricted. Currently there are no antiviral therapies approved by either the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (“FDA”) or the European Medicines Agency (“EMA”).

To address this unmet medical need, we are developing AT-752, an oral, purine nucleotide prodrug for the treatment of dengue. AT-752 targets the inhibition of the dengue viral polymerase and, in preclinical studies, AT-752 showed potent in vitro activity against all serotypes tested, as well as potent in vivo antiviral activity in a small animal model. In March 2021, we initiated a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled Phase 1a clinical trial to evaluate the safety and pharmacokinetics (“PK”), of different dosages of AT-752 in healthy adults. Following the completion of this Phase 1a clinical trial, we expect to initiate a Phase 1b clinical trial in the second half of 2021 to evaluate the antiviral activity, safety and PK of AT-752 in adult patients with dengue virus infection.

Hepatitis C

Despite significant recent advances in treatment, HCV remains a global health burden due to the limitations of currently available treatment options.

For the treatment of chronic HCV infection, we have created a novel combination of AT-527 with AT-777, an investigational nonstructural protein 5A (“NS5A”), inhibitor that we will coformulate into a single, oral, pan-genotypic fixed-dose combination product candidate, AT-787. We believe that AT-787 has the potential to offer a short duration protease-sparing regimen for HCV-infected patients with or without cirrhosis. For patients with decompensated cirrhosis, a life-threatening stage of liver disease, AT-787 has the potential to treat these patients without the co-administration of ribavirin. In March 2020 we paused clinical development in our HCV program due to the outbreak of the COVID-19 pandemic. In the second half of 2021, we expect to re-initiate a Phase 1/2a clinical trial, which will be designed to evaluate the safety and PK of different dosages of AT-777 in healthy adults and to evaluate the combination of AT-527 and AT-777 in HCV infected patients.

RSV

RSV is a seasonal respiratory virus that is responsible for significant health and economic burden worldwide. RSV is a common virus that causes severe respiratory disease in infants, which often leads to hospitalization. Up to 70% of infants are infected by the age of one and virtually all infants will have been infected by their third year of life. As protective immunity wanes, RSV reinfection in children and adults, is common. While these reinfections tend to be milder, RSV is a well established cause of significant morbidity and mortality in the elderly, the immunocompromised and other high-risk patients. There is also an increased awareness of the long-term consequences of RSV primary infection that have been linked to prolonged wheezing and an increased risk of developing asthma. There are no approved vaccines. The only approved drugs are ribavirin, which has safety concerns and questionable efficacy and Synagis, a monoclonal antibody which is indicated not for treatment but only for protection against RSV in a high risk pediatric population.

We are evaluating AT-889, an investigational, second-generation nucleoside pyrimidine prodrug and other compounds for the treatment of RSV. AT-889 is designed to inhibit RNA polymerase through both initiation of viral replication and viral transcription and showed potent in vitro activity in several cell based assays against RSV. In the second half of 2021, we expect to nominate a lead product candidate and initiate investigational new drug application (“IND”) enabling studies.

3

Our Team

Our management team has significant experience discovering, developing and commercializing antiviral therapies for life-threatening viral infections. Our Founder, Chairman, and Chief Executive Officer, Jean-Pierre Sommadossi, Ph.D., has over 30 years of scientific, operational, strategic, and management experience in the biopharmaceutical industry. Dr. Sommadossi has authored over 180 peer-reviewed publications and holds more than 60 U.S. patents related to the treatment of antiviral therapeutics and cancer. Dr. Sommadossi was the principal founder of Idenix Pharmaceuticals, Inc. (“Idenix”), which was acquired by Merck & Co., Inc. (“Merck”), in 2014, and a co-founder of Pharmasset, Inc. (“Pharmasset”), which was acquired by Gilead Sciences, Inc. in 2012.

We have assembled an experienced management and scientific team with a track record of success in the field of antiviral drug development, many of whom have worked together previously. Our team has significant expertise in nucleos(t)ide chemistry, biochemistry and virology and has applied that expertise towards the discovery and development of innovative antiviral treatments, including Epivir, Sovaldi, Tyzeka, Valtrex, Wellferon, Videx, Reyataz, Sustiva, Mavyret, Xofluza, Relenza and Zerit. Members of our team have held senior positions at AstraZeneca plc, Merck, GlaxoSmithKline plc, Chiron, Novartis International AG, Biogen, F. Hoffmann La Roche, Abbvie, Bristol Myers Squibb, Shire, Biohaven Pharma, Pharmasset, Idenix, Valeant Pharmaceuticals International and Alnylam Pharmaceuticals.

Our Strategy

Our goal is to become a global leader in the discovery, development, and commercialization of novel antiviral therapies for severe or life-threatening viral infections. We intend to achieve this goal by pursuing the following strategies:

• | Rapidly complete development and obtain approval for our lead product candidate, AT-527, an oral drug for the treatment of COVID-19. In collaboration with Roche, we intend to initiate a global Phase 3 clinical trial of AT-527 in patients with mild or moderate COVID-19 in the outpatient setting in the second quarter of 2021. Currently, we are evaluating AT-527 for the treatment of COVID-19 in two Phase 2 clinical trials and a Phase 1 clinical trial. We are working closely with the FDA and other regulatory authorities as we plan and implement our clinical trials to align on the most efficient regulatory pathway. |

• | Deploy our medicinal chemistry expertise and proprietary nucleotide platform against severe ssRNA viruses with high unmet need. We are developing additional small molecule antiviral product candidates for the treatment of other severe viral diseases, including AT-752 for the treatment of dengue, which, if successfully developed and approved, we believe has the potential to become the first approved treatment for dengue fever – a disease that infects up to 400 million people each year; AT-787, a co-formulated, oral, pan-genotypic fixed dose combination of AT-527 and AT-777, for the treatment of HCV which we believe has the potential to shorten treatment duration compared to existing therapies, cure difficult-to-treat populations not currently served by existing therapies, and eliminate the need for ribavirin in patients suffering from decompensated cirrhosis; and AT-889, an investigational, second-generation nucleoside pyrimidine prodrug, and other compounds for the treatment of RSV which, if successfully developed and approved, we believe could be the first therapy in over 30 years to be approved specifically for the treatment of RSV. |

• | Focus on excellent clinical and regulatory execution. We believe that building a successful antiviral-focused company requires very specific expertise in the areas of clinical study design and conduct and regulatory strategy. We have assembled a team with a successful track record of managing global clinical development activities in an efficient manner, and with multinational experience in obtaining regulatory approvals for antiviral therapeutics. |

4

• | Maximize the value of our product candidates. We generally intend to retain global commercialization rights to our product candidates, which we believe will allow us to retain the greatest potential value of our product portfolio. However, we may opportunistically enter into license agreements or collaborations where we believe there is an opportunity, particularly outside the United States, to maximize the value and accelerate the development of our product candidates and potential commercialization of any products. For example, in October 2020 we entered into the Roche License Agreement under which we granted an exclusive license for certain development and commercialization rights related to AT-527 outside of the United States to Roche. Currently, we plan to establish our own commercial organization in the United States, and we may build additional commercial organizations in other selected markets for any of our product candidates that are approved. |

• | Maintain our entrepreneurial outlook, scientifically rigorous approach, and culture of tireless commitment to patients. The patients we seek to treat suffer from life-threatening viral infections for which there are no approved therapies or the therapies that are approved have significant drawbacks which may include limited efficacy, or issues with safety and/or tolerability. Members of our team have dedicated their lives to discovering, developing, and commercializing novel antiviral therapies for severe or life-threatening viral infections. We intend to continue building our team of qualified individuals who share our commitment to collaborate and apply scientific rigor in the development of novel antiviral therapies that have the potential to treat or cure some of the world’s most severe viral diseases. |

Antiviral therapy

Background on viruses

Viruses are cellular parasites that can only replicate using a host cell’s replication processes, as viruses lack the machinery required to survive and replicate on their own. Unlike living organisms that use DNA as the basis for their genetic material, viruses can use either DNA or RNA. Approximately 70% of all viruses are RNA viruses.

Viruses have two primary components: nucleic acid (single or double stranded RNA or DNA) and a protective shell (the capsid). Some viruses may also have a lipid bilayer (the envelope) surrounding the capsid, an additional membrane derived from host cell membranes that contains viral proteins.

The viral replication process begins when a virus attaches itself to a specific receptor site on the host-cell membrane through attachment proteins. The replication mechanism is dependent upon whether the virus is an RNA or DNA virus. DNA viruses use host cell proteins and enzymes to make additional DNA that is used to copy the viral genome or is transcribed to messenger RNA (“mRNA”). RNA viruses use their RNA as a template for synthesis of viral genomic RNA and mRNA. The mRNA then instructs the host cell to assemble viral structural proteins. Finally, the newly created virus particles (“virions”), are released from the host cell in order to repeat the infection and replication cycle. RNA viruses can be particularly challenging to treat, as the error rates around the viral RNA polymerase directed RNA synthesis cause high mutation rates during reproduction, creating variants and resistance challenges for antiviral therapies.

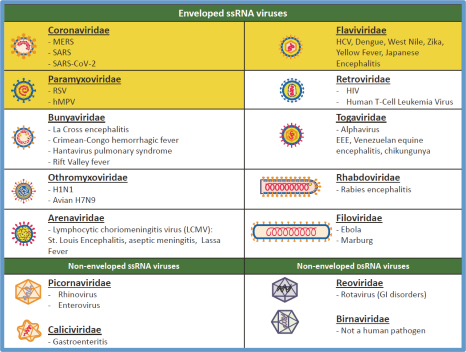

Background of ssRNA viruses

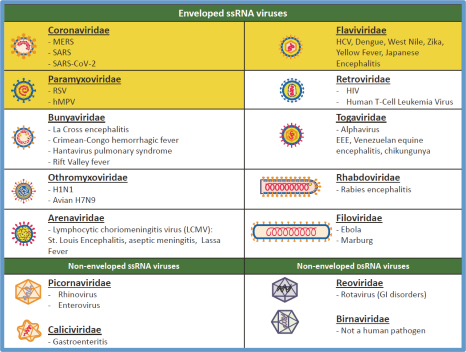

RNA viruses can be single stranded (ssRNA) viruses or double-stranded (dsRNA), viruses, depending on the type of RNA used as the genetic material. A virus encased within a lipid bilayer is known as an enveloped virus, while a virus without this bilayer is called a non-enveloped virus. Enveloped ssRNA viruses are the more prevalent cause of severe human viral diseases. Studies from the last decade have placed RNA viruses as primary etiological agents of many emerging human pathogens, representing up to 50% of all emerging infectious diseases. Types of enveloped and non-enveloped ssRNA viruses and some of the diseases they cause are shown in the table below, with the types of ssRNA viruses that we are currently targeting with our product candidates highlighted in yellow.

5

Over the last 40 years, a great deal of progress has been made in the treatment of some of the most severe viral infections. However, many highly pathogenic ssRNA viruses, including dengue virus and newly emerging viruses such as SARS-CoV-2 continue to cause severe viral diseases which still remain inadequately treated or not treated at all.

Viral polymerase as an antiviral target

From the discovery and approval of the first antiviral drug in 1963, there have been more than 100 antiviral drugs approved in the United States for the treatment of nine different human viral diseases. A historical challenge with the treatment of intracellular viruses has been selectivity or discovering drug targets that can completely inhibit viral replication without harming the host cells, leading to toxic side effects. Advances in technology and high throughput screening in recent years have driven the discovery of more selective antiviral product candidates. The viral polymerase, which is the single protein present in all RNA viruses, is a key enzyme in the replication of viruses, making for an ideal drug target as its core structural features are highly conserved across different viruses. There are four types of viral polymerase, depending upon the virus and its genomic makeup:

• | RNA-dependent RNA polymerase (“RdRp”): All ssRNA viruses, including SARS-CoV-2 and HCV, depend on the RdRp, encoded in the viral genome, for replication and transcription. Since these enzymes are not present in the host cell, this facilitates the design of selective inhibitors of viral replication, which target viral but not host cell polymerases. |

• | DNA-dependent DNA polymerase (“DdDP”): DdDP is used by DNA viruses to replicate their genome. |

• | RNA-dependent DNA polymerase (“reverse transcriptase”): Reverse transcriptase is used by certain DNA or RNA viruses, such as HBV and HIV-1, to replicate their genomes. |

• | DNA-dependent RNA polymerase (“DdRP”): DdRP is used by DNA viruses to transcribe mRNA from DNA templates during replication. |

As viral RNA polymerase based synthesis does not occur in human host cells, antiviral drug development for RNA viruses focuses on identifying selective drug-like molecules that target viral RNA polymerase. Advances in technology have enabled intensive structural and functional studies of viral RNA polymerase including the identification in the case of SARS-CoV-2 of nidovirus RdRp associated nucleotidyltranferase (“NiRAN”), and have opened avenues for the development of new and more effective antiviral therapies.

6

Viral resistance and Variants

A major obstacle to antiviral therapy is viral resistance. Resistance is a function of a virus’ ability to genetically mutate, which, in the case of RNA viruses, is substantially higher than DNA viruses, as most RdRp lack proofreading abilities. The rate of mutation of RNA viruses can occur at six orders of magnitude greater than the rate of mutation of host cells. The ability of viruses to evolve makes the design of ssRNA-directed therapies challenging, as these viral strains continue to mutate and become more resistant to certain antiviral therapies over time. Since all the enzymes involved in the metabolic pathways of AT-527 and AT-752 to their active triphosphate are designed to be essentially ubiquitous host cell enzymes and not virally encoded proteins, we believe that the high rate of viral mutation does not affect the activation of the prodrug.

At times, combination therapy has been used to combat viral resistance for specific types of human viral infections. The guiding principles to decide when combination therapy may be needed, include: the in vitro inhibitory potency and human pharmacology of the antiviral; viral replication kinetics in patients; viral polymerase error rate; and whether the viral disease is an acute or a chronic infection. With RNA viruses, the treatment of acute infection, such as influenza, is monotherapy (e.g., Tamiflu), as compared to the treatment of chronic infection, such as HCV, which is combination therapy (e.g., Epclusa). COVID-19, dengue and RSV are each the result of acute RNA viral infections.

Another consequence of viral mutations is the emergence of new variants. For example, each year the genetic mutations accumulated in the influenza virus cause antigen drift that could significantly impact immune recognition, thus the flu vaccines have to be reviewed and updated. SARS-CoV-2, despite the fact that it does have a proof-reading function with the nsp14 exonuclease, has proven to be able to mutate quickly as well. Multiple SARS-CoV-2 variants are circulating globally. For example, variants that have emerged since fall 2020, include B.1.1.7 (also known as 501Y.V1, VOC 202012/01) in the U.K., B.1.351 (501Y.V2) in South Africa, P.1 (20J/501Y.V3) in Brazil, and B.1.526 in New York. Some of these variants not only appear to transmit faster and cause more serious illness but may also reduce the efficacy of current vaccines and antibodies, and thus present an even greater health challenge.

Nucleos(t)ide analogs and prodrugs

Nucleic acids (DNA and RNA), which comprise human and viral genetic material, are composed of natural chemical compounds termed nucleosides and nucleotides. Nucleos(t)ide analogs, which are synthetic compounds that mimic the structure of naturally occurring nucleosides and nucleotides, target the viral polymerase directly so that it mistakenly incorporates these analogs into nascent nucleic acids, causing inhibition of viral replication. Nucleos(t)ide analogs, compared to other classes of antiviral therapies, have a high barrier to viral resistance due to the conservation of the structure of the polymerase that is required to produce viable virions.

Prodrugs of nucleos(t)ide analogs have become the backbone of therapies to treat life threatening viral infections, including HIV, HBV, and HCV. Prodrugs are employed to bypass rate limiting activation steps and to improve the oral bioavailability and permeation of cell membranes by the nucleos(t)ide analog.

Our Platform

Leveraging our deep understanding of antiviral drug development, nucleos(t)ide chemistry, biochemistry and virology, we have built a proprietary purine nucleotide prodrug platform to develop novel treatments for life threatening diseases caused by ssRNA viral infections.

Our proprietary nucleotide prodrug platform, as illustrated below, is comprised of the following critical components:

• | specific modifications at the 6-position of the purine base, acting as a prodrug, are designed to prevent the toxic effects of other such modifications and enhance cell membrane permeability, resulting in an intermediate metabolite that maximizes formation of the triphosphate active metabolite in cells; |

• | stereospecific phosphoramidate, acting as a prodrug, designed to bypass the first rate-limiting phosphorylation enzyme in the intracellular activation pathway; |

• | specific modifications in the sugar moiety of the purine nucleotide scaffold, producing potent antiviral activity with a high degree of selectivity; and |

• | highly specific salt form to enhance solubility and drug bioavailability. |

7

Atea’s purine nucleotide prodrug platform

We believe that product candidates derived from our platform, which combines unique purine nucleotide scaffolds with a novel double prodrug strategy, have the following potential advantageous characteristics and features:

• | enhanced antiviral activity and selectivity, as well as well-established pharmacology and animal models to predict clinical activity; |

• | favorable safety profile; |

• | convenience of once- or twice-daily oral administration; and |

• | efficient, predictable, scalable, and reproducible manufacturing, as well as long shelf life for potential stockpiling. |

Development Programs

AT-527 for the treatment of COVID-19

Although vaccines have an important role in mitigating the COVID-19 pandemic, we believe that there will be a continuing need for treatment options to stay ahead of the virus and the emergence of variants. While there are parenterally or intravenously administered therapeutics available for use in the hospital setting, oral treatments would be more practical and efficient for use in the early stages of disease in an outpatient setting, including for patients with mild to moderate symptoms. Thus we believe that a significant and urgent unmet medical need remains for orally administered, direct acting antivirals with broad utility for the treatment of COVID-19.

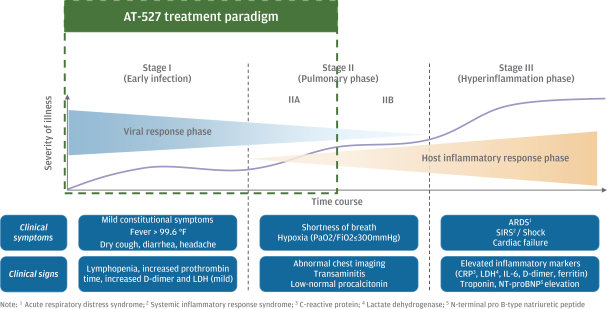

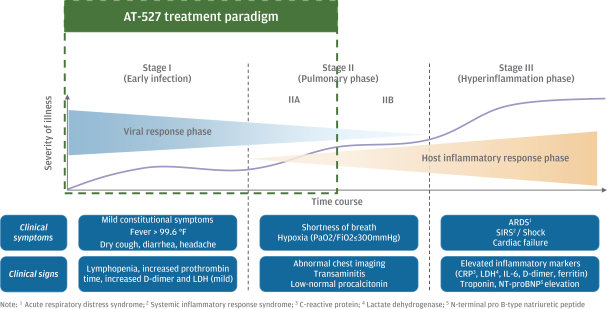

COVID-19 is an acute viral infection. We believe antiviral therapeutics should be most effective against COVID-19 within the first stage of the infection when the viral load is at its maximum, which is consistent with rapid viral replication initially in nasal cells, throat cells and ultimately pulmonary cells. As shown in the illustration below, we believe that the use of a potent, safe, oral antiviral therapeutic to treat SARS-CoV-2-infected individuals in the early stage of infection will mitigate the onset of severe COVID-19 and avert hospitalization.

8

SARS-CoV-2

Background

SARS-CoV-2 is a coronavirus, belonging to the Coronaviridae family, and is an enveloped virus with a positive sense ssRNA genome which encodes 29 viral proteins. It is one of six other human coronaviruses that exist, with four responsible for one third of common cold infections.

SARS-CoV-2 is structurally similar to two other life-threatening coronaviruses: SARS-CoV and Middle East Respiratory Syndrome coronavirus (“MERS-CoV-1”). SARS-CoV-2 impairs respiratory function and spreads primarily from person to person via respiratory droplets among close contacts. Symptoms, which may include fever, cough, shortness of breath and fatigue, generally appear two to twelve days after exposure. Severe complications include pneumonia, multi-organ failure, and death.

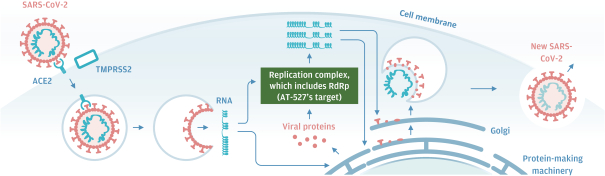

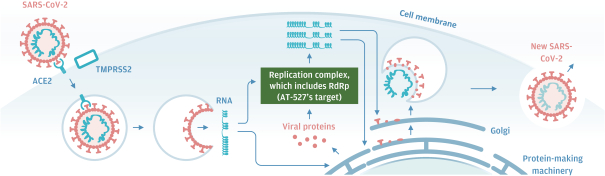

SARS-CoV-2 is a spherical virus that carries four different structural proteins: spike protein, envelope protein, membrane glycoprotein and nucleocapsid protein. As shown in the illustration below, the infection cycle begins when the spike proteins bind to the angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 cellular receptor (“ACE2”), on the surface of the target cells. A second cell surface protein, transmembrane serine protease 2 (“TMPRSS2”), enables the virion to enter the cell, where it releases its RNA. Some of this RNA is translated into new proteins using the host cell’s machinery—these proteins include the four structural proteins, as well as a number of non-structural proteins (“nsps”), that form the replication complex. Within this complex, RdRps catalyze the synthesis of the approximately 30,000-nucleotide RNA viral genome. The proteins and RNA are then assembled into a new virion in the Golgi and released through exocytosis.

SARS-CoV-2 replication process

9

COVID-19

Current vaccine and treatment landscape

Several vaccines have been recently authorized for emergency use and additional vaccines and drug candidates are being developed to prevent infection and to create herd immunity, with the aim of preventing disease and reducing the amount of virus circulating within the community. Antiviral therapies are complementary to vaccines, and we anticipate that antivirals will continue to be essential because of uncertainties around the level of immunity that the vaccines will be able to generate, the durability of such immunity and the emergence of new variants of the virus that could change and potentially lessen the effectiveness of vaccines.

As of March 29, 2021, the FDA has granted emergency-use authorizations for certain monoclonal antibody regimens for the treatment of mild to moderate COVID-19 and for convalescent plasma. Antibody therapies, including those that are currently authorized for emergency use as well as those in development, may have application in prevention as well as treatment. However, the antibodies currently in use and in development require parenteral administration and are historically more complex than small molecules to manufacture. We believe that these two factors will impact and limit the use of antibodies for the treatment of patients, particularly outpatients with COVID-19.

Remdesivir, an antiviral that is a RdRp inhibitor, is approved by the FDA for treatment of adults and pediatric patients 12 years of age and older with COVID-19 requiring hospitalization. The limited bioavailability of remdesivir requires administration via intravenous infusion, which we believe is likely to limit its use to hospitalized patients.

Clinical drug candidates in development include small molecules designed to work as direct acting antivirals, which may be administered for both treatment and potentially prophylaxis. In addition to our antiviral candidate, AT-527, other antiviral drug candidates currently in development include molnupiravir, a nucleoside analog that incorporates into the viral RNA leading to lethal accumulation of mistakes or “error catastrophe” and PF-0083521, a protease inhibitor.

In addition to treatments directed at the virus, there are other immunomodulatory therapies such as interleukin-6 inhibitors, steroids, JAK inhibitors, and anti-tumor necrosis factor antibodies which are being developed to treat the host inflammatory response to the disease.

Our approach

We, together with our collaboration partner, Roche, are developing AT-527, an orally administered, novel antiviral product candidate, for the treatment of COVID-19. AT-527 uniquely inhibits viral RNA polymerase including both NiRAN and RdRp functional domains.

Targeting SARS-COV-2 NiRAN/RdRp to treat COVID-19

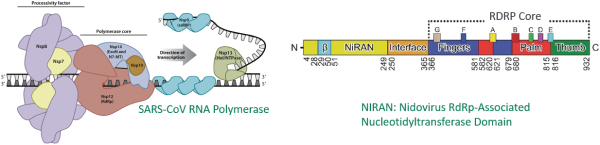

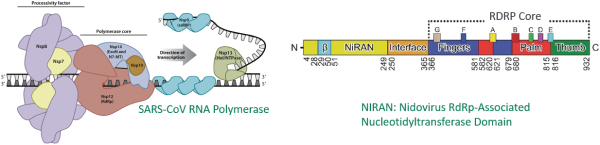

The RNA polymerase complex of SARS-CoV and SARS-CoV-2 supports the transcription and replication of their approximately 30,000-nucleotide viral RNA genomes. It is the largest and most complex RNA synthesis machinery among RNA viruses. As shown in the illustration below, the multi-subunit SARS-CoV polymerase complex is composed of a number of nsps including viral RNA-dependent RNA polymerase (nsp12), processivity factors (nsp7, nsp8), a proofreading exonuclease, a N7-methyl transferase (nsp14), and a helicase (nsp13). The nsp12 protein contains two domains, a RdRp core, which is the catalytic subunit incorporating ribonucleotides into RNA templates, and a N-terminal NiRAN domain, the function of which was previously unknown.

SARS-CoV RNA Polymerase

10

We have investigated the mechanism by which SARS-CoV initiates viral RNA synthesis and have discovered that there are two distinct pathways: one protein-primed and mediated by the NiRAN through the UMPylation of nsp8, and the other through de novo synthesis of dinucleotide primers in a NiRAN-independent manner. Importantly, both functions can be inhibited by AT-9010, the active triphosphate metabolite of the prodrug AT-527. Furthermore, we have obtained a 2.98 Å cryo-EM quaternary structure of nsp12/7/8/RNA/AT-9100, which confirms that AT-9010 not only bound to the NiRAN active site but also was incorporated by the RdRp and functions as a chain terminator. We believe this unique dual mechanism of AT-527 may create a potentially higher barrier to resistance compared to other direct acting antiviral inhibitors. We expect that AT-527 will maintain its antiviral activity even against the recently emerged variants with mutations in the spike (S) protein responsible for the receptor recognition and host cell membrane fusion process. These variants may affect the efficacy of vaccines and antibodies due to the mutations in the viral spike protein.

It is also conceivable that the proofreading exonuclease activity of nsp14 could remove the terminating analog nucleotide from the RdRp core and experiments to demonstrate this are ongoing. However, the NiRAN function has no exonuclease activity.

Preclinical Studies

AT-511, the free base of AT-527, has shown in vitro antiviral activity against multiple ssRNA viruses, including human flaviviruses and coronaviruses.

We assessed the in vitro potency of AT-511 against SARS-CoV and SARS-CoV-2. The data observed is summarized in the table below.

The activity against SARS-CoV was assessed after exposure of Huh-7 cells to virus and serial dilutions of test compound by determining the effective concentration required to reduce secretion of infectious virus into the culture medium by 90% (EC90) after a 3-day incubation using a standard endpoint dilution CCID50 assay to determine virus yield reduction (VYR). Half-maximal cytotoxicity (CC50) was measured by neutral red staining of compound-treated duplicates in the absence of virus.

Since Huh-7 cells were unable to support infection by and replication of SARS-CoV-2, normal human airway epithelial (“HAE”) cell preparations were used to assess the activity of AT-511 against this virus, using the same method as described above. Cytotoxicity was assessed by visual inspection of the cells at the end of the 5-day incubation period.

In Vitro Activity of AT-511 (free base of AT-527) Against Human Coronaviruses

| | | | |

Virus

(genus) | Cell line | Compound | Cytopathic

Effect Assay

CC50 (µM) | Virus Yield

Reduction

Assay EC90

(µM)(n) |

SARS‐CoV

(beta) | Huh‐7 | AT‐511 | >86 | 0.34 |

SARS‐CoV‐2

(beta) | HAE | AT‐511 molnupiravir remdesivir | >86a >19a >8.3a | 0.47 ± 0.012 (5) 2.8 ± 1.0 (3) 0.002 to 0.27 (5) |

aCytotoxicity assessed by visual inspection of cell monolayers

Huh‐7, human hepatocyte carcinoma cell line (established ability to form triphosphate from AT‐511)

HAE, human airway epithelial cell culture (established ability to form triphosphate from AT‐511)

The EC90 values for AT-511 against SARS-CoV and SARS-CoV-2 were 0.34 µM and an average of 0.5 µM from five independent experiments. The concentration of AT-511 required to exhibit CC50 of the host cells used in these assays to support viral infection and propagation was consistently greater than the highest concentration tested (>86 µM). The sub-micromolar EC90 values, in combination with the lack of

11

toxicity observed in the host cells, suggests the potential for high potency and selectivity of AT-511 in vivo against these SARS coronaviruses.

The EC90 for remdesivir, which was included in all SARS-CoV-2 assays as a positive control and was included as a blinded test article in two independent assays, ranged from 0.002-0.27 µM. The potency of remdesivir, however, is likely a combination of its antiviral activity and cytotoxicity since dying and dead cells cannot support efficient viral replication. The CC50 for remdesivir, determined by neutral red staining in the SARS-CoV assay conducted in human cells (Huh-7; less precise visual assessments without staining were used to determine cytotoxicity in the HAE assays) ranged from 5-11 µM. Similar in vitro cytotoxicity of remdesivir (1.7-36 µM CC50) has been reported in other cell lines.

We also assessed the in vitro potency of N4-hydroxycytidine, the nucleoside formed from the oral prodrug molnupiravir currently being developed by Ridgeback/Merck for the treatment of COVID-19. N4-hydroxycytidine was five to eight times less potent than AT-511 against SARS-CoV-2 in the same experiment. We also assessed the antiviral activity of sofosbuvir and found that it did not inhibit SARS-CoV replication in BHK-21 cells at concentrations as high as 100 µM and was a poor inhibitor of SARS-CoV-2 with an estimated EC90 of about 8 µM in HAE cells.

In addition to assessing the in vitro potency of AT-511 against SARS-CoV-2 and SARS-CoV, we evaluated the formation and intracellular half-life of AT-9010, the active triphosphate metabolite of AT-527, in primary human nasal and bronchial epithelial cells. Also, we evaluated the pharmacokinetics and intracellular half-life of AT-9010 in tissues of non-human primates after oral administration of AT-527.

Substantial levels of the active triphosphate of AT-527 were formed in normal human bronchial and nasal epithelial cells incubated in vitro with 10 µM AT-511. After an 8-hour incubation, intracellular concentrations of the triphosphate were 698 and 236 µM in the bronchial and nasal cells, respectively. After replacement of the culture medium at 8 hours with fresh medium without AT-511, the half-life of the active triphosphate was determined to be 39 and 38 hours in the respective cell incubations. The accumulation and half-life of remdesivir triphosphate has been reported in the same type of human bronchial epithelial cells incubated with 1 µM remdesivir. After similar eight hour incubations, the concentration of remdesivir triphosphate, normalized to a dose of 10 µM, is at least 7-fold lower than the observed concentration of AT-9010 in the same cell type. In similar incubations of 1 µM remdesivir with human bronchial epithelial cells for two hours followed by washout of drug and continued incubation for 30 hours, the initial half-life of remdesivir triphosphate was less than 8 hours which is at least 4 times shorter than the half-life of AT-9010 in the same primary human lung cells, suggesting the accumulation of higher levels of AT-9010 leading to a potentially greater antiviral effect after twice daily oral administration of 550 mg AT-527 versus daily intravenous administration of remdesivir (200 mg loading + 100 mg maintenance doses).

In non-human primates (“NHPs”) administered AT-527 orally for three days in the form of a loading dose (60 mg/kg) followed by five maintenance doses (30 mg/kg each) 12 hours apart, intracellular concentrations of the active triphosphate metabolite in lung, kidney and liver tissue 12 hours after the last dose (steady-state trough levels with respect to twice daily dosing) were 0.14, 0.13 and 0.09 µM, respectively. Since the NHP maintenance doses were allometrically scaled to be equivalent to the initially intended clinical maintenance doses for COVID-19 subjects (550 mg AT-527 given orally twice daily), predicted trough concentrations of AT-9010 in lung cells in prospective COVID-19 subjects were obtained from the plasma pharmacokinetics of AT-273 (surrogate for intracellular triphosphate concentrations) obtained from COVID-19 subjects given twice-daily oral doses of 550 mg AT-527.These values were adjusted by either the 1.6-fold greater triphosphate lung versus liver concentrations or the 1.2-fold greater lung triphosphate versus plasma AT-273 concentrations observed at 12 hours after the last dose in NHPs. These predictions of the trough human lung concentrations (0.9 and 0.7 µM, respectively) were based on the established close pharmacokinetic-pharmacodynamic relationship between plasma AT-273 concentrations and the antiviral effect in HCV-infected patients. We believe both predictions suggest that trough levels of the active triphosphate in COVID-19 patients during treatment with AT-527 should exceed the EC90 of 0.5 µM for AT-511 against SARS-CoV-2 replication. Moreover, we believe both predictions likely underestimate triphosphate trough levels in human lung since neither account for the extended intracellular half-life (39 hours) of the triphosphate observed exclusively in human lung epithelial cells in vitro.

12

Clinical Development History

AT-527 was initially developed for the treatment of chronic HCV, and we have completed two clinical trials of AT-527 in HCV. See –Hepatitis C virus (HCV)—Clinical development. By utilizing data that we obtained in our HCV clinical trials of AT-527, we were able to initiate our clinical development program of AT-527 for the treatment of patients with COVID-19. Ongoing clinical trials include a Phase 2 clinical trial in hospitalized patients, a Phase 2 clinical trial in the outpatient setting and a Phase 1 clinical trial in healthy volunteers.

Ongoing Phase 2 clinical trial in hospitalized patients

We are currently conducting a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, multi-center, global Phase 2 clinical trial of AT-527, which is expected to enroll approximately 190 COVID-19 hospitalized patients.

Patients eligible for enrollment in this Phase 2 clinical trial are aged 18 to 80 years with moderate COVID-19 illness and at least one risk factor suggestive of poor outcome (such as obesity, hypertension, a history of diabetes, or a history of asthma). Moderate severity is defined as having at least one symptom of lower respiratory infection consistent with COVID-19, as well as oxygen saturation below 93% on room air or requiring ≤2L/min oxygen to maintain oxygen saturation in excess of 93%. The primary efficacy endpoint is the change in level of respiratory insufficiency, assessed on an ordinal 6-category scale of respiratory support levels, as compared to placebo, where a statistically significant finding would be reflected by a significantly lower probability for AT-527-treated subjects to exhibit a worsening of respiratory insufficiency (requiring ≤2 level higher respiratory support) during the study compared to placebo recipients. The six categories of the ordinal scale are: (1) no respiratory support; (2) low-level passive O2 supplementation (up to 2 L/min) by mask or nasal cannula; (3) higher O2 supplementation (>2 L/min); (4) any non-invasive form of positive-pressure oxygenation/ventilation; (5) invasive respiratory support; and (6) death. We believe the most important outcomes to be assessed in this trial are the effect of AT-527 versus placebo on the viral kinetics of the infection and the elucidation of the safety and tolerability of the drug at the dose of 550mg administered twice daily.

Trial participants are being randomized 1:1 (AT-527: placebo). The first 40 patients (20 AT-527, 20 placebo) received a dose of either 550 mg of AT-527 or placebo twice daily for five days in addition to supportive standard of care. In accordance with the protocol, an independent Data Safety Monitoring Board (“DSMB”), conducted safety reviews after the first cohort of 20 patients, and again after the second cohort of 20 patients, and approved continued enrollment of patients in the trial.

There are additional planned pauses and DSMB reviews at each of the 50% and 75% enrollment levels.

We expect to report interim virology data from this Phase 2 clinical trial in the second quarter of 2021.

Ongoing Phase 2 clinical trial in an outpatient setting

In addition to the Phase 2 clinical trial in hospitalized patients, we, together with our collaborator, Roche, are conducting a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled Phase 2 clinical trial to evaluate the antiviral activity, safety, and pharmacokinetics of AT-527 in adult patients with mild or moderate COVID-19, with and without risk factors, in an outpatient setting (MOONSONG). There are multiple cohorts included in this clinical trial. The initial cohort is receiving 550 mg of AT-527 administered twice daily. With additional cohorts we may investigate dosing regimens in addition to the 550 mg twice-daily dose. The study may enroll up to 220 patients in the U.K., Ireland and other countries.

We expect to report interim virology data from this Phase 2 clinical trial in the second quarter of 2021.

Phase 1 clinical trials

In addition to the Phase 2 clinical trials, we, in collaboration with Roche, are conducting a Phase 1 clinical trial of AT-527 in healthy volunteers and we are planning several additional Phase 1 clinical trials, including clinical pharmacology studies required to support applications for regulatory approval.

On March 6, 2021 we announced favorable results from a Phase 1 clinical trial that evaluated 20 healthy volunteers who were randomized 1:1 to receive oral AT-527 550 mg twice daily (BID) or matching placebo for 5 days. The results demonstrated that AT-527 was well tolerated. In this Phase 1 clinical trial, there were no discontinuations, serious adverse events, clinically significant changes in vital signs, or electrocardiograms observed. The data also demonstrated that AT-511, the free base of AT-527, was

13

rapidly absorbed, followed by fast and extensive stepwise metabolic activation ultimately to the active triphosphate metabolite AT-9010, reflected by plasma AT-273. AT-527 550 mg BID led to fast attainment of steady-state levels of AT-273 within two days of dosing. Plasma levels of AT-273 were further used to predict lung concentrations of AT-9010 using a scaling factor of 1.2X which was previously determined based on in vivo tissue distribution of the triphosphate metabolite observed in cynomolgus monkeys. Beginning as early as three hours after the first dose, and maintained thereafter throughout the five days of dosing, predicted lung AT-9010 levels were consistently above the EC90 level of 0.5 µM that was required for in vitro inhibition of SARS-CoV-2 replication in cynomolgus monkeys.

Planned Phase 3 Global Clinical Development Program

Phase 3 Registrational Clinical Trial

We, together with Roche, are currently engaging with regulatory authorities in order to open a Phase 3 clinical trial of AT-527 in an outpatient setting (MORNINGSKY). This clinical trial is expected to enroll patients aged 18 years and older with mild or moderate COVID-19. The primary objective of the trial is expected to be evaluation of the efficacy of AT-527 compared to placebo by measuring the time to alleviation of symptoms (“TAS”), in patients with SARS-CoV-2 virus infection with mild or moderate disease. The primary endpoint of TAS is defined as the time when all COVID-19 symptoms are assessed and self-reported by the patient as none or mild for a duration of at least 24 hours. Patients will assess the severity of disease on a 4-point scale (with 0 indicating no symptoms, 1 mild symptoms, 2 moderate symptoms, and 3 severe symptoms). We expect to enroll approximately 1,500 patients in this clinical trial.

Post-exposure Prophylaxis Clinical Trial

We, together with Roche, are also planning to conduct a randomized, double-blind, post-exposure prophylaxis Phase 3 clinical trial evaluating the reduction of direct transmission from SARS-CoV-2 infected patients (index case) to contacts. In this outpatient clinical trial, we expect to enroll approximately 3,000 patients aged 18 years or older. Pending additional discussions with regulatory authorities, the primary endpoint is expected to be the proportion of participants who test positive by RT-PCR at predetermined timepoints.

Regulatory Strategy

To align on the most efficient regulatory pathway for AT-527 in COVID-19, we and Roche are engaging in discussions with the FDA and other regulatory authorities as we plan and implement the clinical trials described above.

Clinical Trial Material

We and Roche are currently conducting manufacturing campaigns at third-party contract manufacturers that are expected to result, when combined with our current drug tablet inventory, in an inventory of AT-527 275 mg and 550 mg tablets and matching placebo that is expected to satisfy the clinical trial material requirements for currently planned COVID-19 clinical trials. Additionally, we, together with Roche, are engaged, through our contract manufacturers, in the optimization of the synthetic process and formulation for commercial scale manufacture of AT-527 275 mg tablets. We are targeting availability of initial commercial supply of AT-527 beginning in 2022.

AT-752 for the Treatment of

Dengue

Background

Dengue, which is caused by a positive sense ssRNA virus belonging to the Flaviviridae family, is a mosquito-borne viral infection. Dengue causes flu-like symptoms in both children and adults and is spread through the bite of an infected mosquito. There are five dengue viral serotypes, and infection with one serotype does not produce immunity to another serotype. Thus, a person could be infected with dengue multiple times and reinfection typically results in a more severe disease. Symptoms include fever, eye pain, headache, swollen glands, rash, muscle pain, bone pain, nausea, vomiting, and joint pain, and last two to seven days post-infection.

14

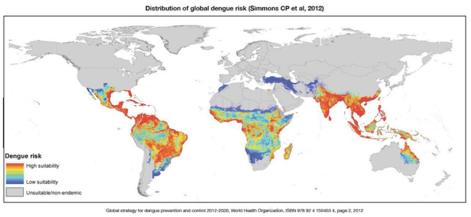

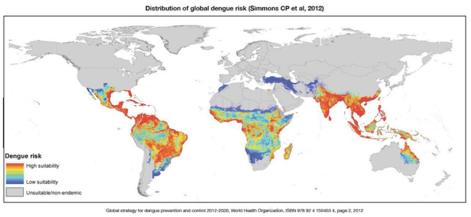

Globally, three billion people, or roughly 40% percent of the world’s population, live in high-risk dengue areas, while up to 400 million are infected each year, resulting in 500,000 hospitalizations. The WHO has called dengue the most important mosquito-borne viral disease in the world. Although dengue rarely occurs in the continental United States, it is endemic in Puerto Rico, Southeast Asia, Latin America and the Pacific Islands, as shown in the map below. Seventy percent of the global disease burden for dengue is in Asia.

According to the Center for Disease Control (“CDC”), 5% of infected patients develop a life-threatening form of dengue called severe dengue. Those who develop severe dengue may have some or all of the following complications: severe abdominal pain, fatigue, severe bleeding, organ impairment, and plasma leakage. The mortality rate of severe dengue ranges between 12% and 44%, if left untreated. The global economic cost burden of dengue was estimated at $8.9 billion in 2013, with nearly 50% of the costs associated with hospitalizations.

Current treatment landscape

There are no FDA or EMA approved therapies indicated for the treatment of dengue. Current treatment protocols involve supportive care, including analgesics, judicious fluid replacement, and bed rest. In 2019, a vaccine, Dengvaxia developed by Sanofi Pasteur Inc. (“Sanofi”), was approved by the FDA for the prevention of disease caused by dengue virus serotypes 1, 2, 3 and 4 in children ages nine to 16 with laboratory-confirmed previous dengue infection and living in endemic areas.

Takeda Pharmaceuticals Co Ltd, (“Takeda”), is also advancing a dengue vaccine, TAK-003, which is in Phase 3 development. Primary endpoint analysis of its ongoing Phase 3 trial in children ages four to 16 years showed protection against virologically-confirmed dengue.

Our approach

We are developing AT-752, an oral, purine nucleoside prodrug product candidate for the treatment of dengue. AT-752 has shown potent activity against all serotypes tested in preclinical studies. AT-752 is designed to target the inhibition of the dengue viral polymerase. We also intend to explore the potential development of AT-752 as a prophylactic treatment for dengue, which we believe, if approved, could be directed at the travelers’ market. As a part of the Roche License Agreement, we agreed that we would not commercialize AT-752 outside the United States unless we enter into a separate commercialization agreement with Roche to do so. We retain global rights to develop and manufacture AT-752 for the treatment of dengue.

15

Preclinical development

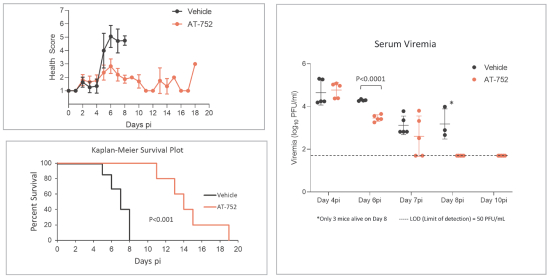

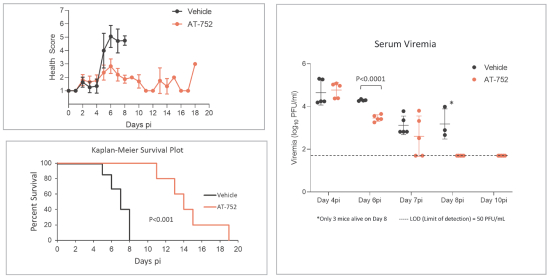

We have conducted preclinical studies of AT-752 in which we pre-treated AG129 mice with AT-752 (1000 mg/kg, p.o.) for four hours before subcutaneous inoculation with D2Y98P dengue strain and subsequent dosing of AT-752 twice daily (500 mg/kg, p.o.) for seven days, starting one hour post inoculation. This disease model, which ultimately resulted in fatal central nervous system sequelae, showed notable differences in overall health, survival, and viremia between AT-752-treated mice and mice that were treated with vehicle. As shown in the graphs below, viral RNA in serum was statistically significantly lower than control by day 6 and below the limit of detection (“LOD”) (LOD: 50 copies per m/L) on day 8, after seven days of drug treatment.

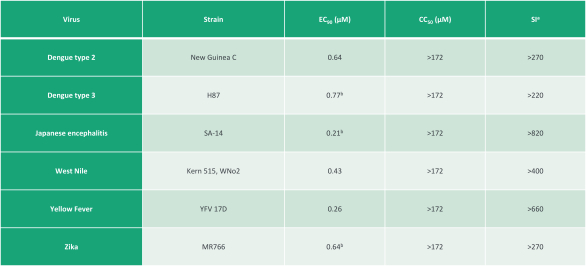

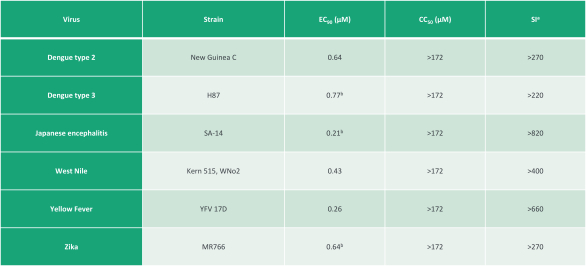

The antiviral activity of AT-281, the free base of AT-752, was evaluated under contract with the National Institutes of Health and Infectious Disease against a variety of flaviviruses. Huh-7 cells were infected with individual viral strains and exposed to serial dilutions of AT-281. A virally induced cytopathic effect (“CPE”), assay using a neutral red dye uptake endpoint or a virus yield reduction measurement using a standard endpoint dilution CCID50 assay was used to measure the antiviral EC50 or EC90 value, respectively. Uninfected cell controls concurrently exposed to drug were used to determine cytotoxicity (CC50) using the CPE assay. AT-281 demonstrated sub-micromolar potencies against all flaviviruses tested (summarized in the table below), with an EC90 of 0.64 µM against Dengue type 2 and an EC50 of 0.77 µM against Dengue type 3. No toxicity was detected for AT-281 up to the highest concentration tested (172 µM).

a | Selectivity index (CC50/EC90 or CC50/EC50) |

16

Clinical development

Phase 1 Clinical Trial

We have initiated a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled Phase 1a trial to evaluate the safety and pharmacokinetics (“PK”) of several different dosages of AT-752 in 50 to 60 healthy adult subjects.

Following the completion of the Phase 1a trial, we expect to initiate in the second half of 2021 a Phase 1b trial of AT-752 in 60 to 80 adult subjects with dengue, to evaluate antiviral activity, safety and PK. Currently, we expect that the endpoints of the Phase 1b trial will include reductions in viral load, fever and time to clearance of non-structural protein 1.

We intend to pursue FDA expedited development and review programs for AT-752. Dengue is also defined as a tropical disease under the Federal Food, Drug and Cosmetic Act (the “FDCA”), and therefore FDA approval of AT-752 for the treatment of Dengue may result in a tropical disease priority review voucher.

AT-787 for the Treatment of Hepatitis C

Hepatitis C virus (HCV)

Background

HCV is a blood-borne, positive sense, ssRNA virus, primarily infecting cells of the liver. HCV is a leading cause of chronic liver disease and liver transplants and spreads via blood transfusion, hemodialysis and needle sticks. Injection drug use accounts for approximately 60% of all new cases of HCV. Diagnosis of HCV is made through blood tests, including molecular tests that allow for the detection, quantification and analysis of viral genomes and the classification of an infection into specific viral genotypes. Hepatitis C becomes chronic Hepatitis C in 75% to 85% of cases, with an incubation period lasting from two to 26 weeks.

HCV is classified into seven genotypes and 67 subtypes, with genotype 1 responsible for more than 70% of HCV cases in the United States. Patients with HCV are also classified by liver function status: compensated cirrhosis (liver scarring) denotes those patients that do not yet have impaired liver function, while decompensated cirrhosis describes patients with moderate to severe liver function impairment.

According to the WHO, an estimated 71 million people are chronically infected with HCV, a significant portion of which are likely to develop cirrhosis or liver cancer. Of those infected with HCV, only 20% are diagnosed and 2% are treated globally. The WHO estimates that 399,000 people died from HCV in 2016.

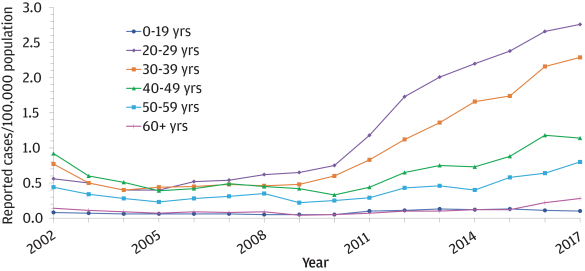

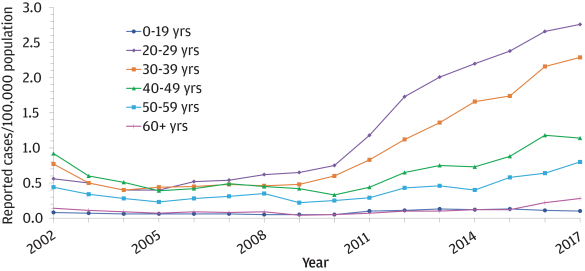

As shown in the table below, the CDC reported that new infections in the United States have increased substantially from 2011 to 2017 with the greatest increase in incidence occurring in individuals ages 20 to 39 years old.

17

Despite recent advances in treatment, there remains a large underserved HCV patient population which continues to grow. The CDC estimated the incidence of HCV in 2018 increased by 50,300 cases in the United States. It is estimated that a substantial global market for HCV therapeutics will exist to 2050 and beyond.

Current treatment landscape

No vaccine exists for the prevention of HCV, but several recently introduced oral antiviral therapeutics have boosted sustained virologic response rates to over 95% in a majority of patients, with treatment durations reduced to eight to 12 weeks depending upon the regimen and patient population. There are three classes of direct acting antiviral therapeutics, defined by their mechanism of action and therapeutic target: NS3/4A protease inhibitors, NS5A inhibitors, and NS5B non-nucleos(t)ide polymerase inhibitors. A patient’s genotype, cirrhotic status, and prior treatment failures determine the appropriate antiviral therapeutic used in treatment. The two leading therapeutics for treatment of chronic HCV are:

• | Epclusa (sofosbuvir/velpatasvir): Epclusa was first approved by the FDA in 2016 for the treatment of adults with chronic HCV infection with any of genotypes one through six infection, either without cirrhosis or with compensated cirrhosis. For patients with decompensated cirrhosis, Epclusa is approved for use in combination with ribavirin. Patients on Epclusa require 12 weeks of treatment. |

• | Mavyret (glecaprevir/pibrentasvir): Mavyret was first approved by the FDA in 2017 for the treatment of adults with chronic HCV with any of genotypes one through six infection, without cirrhosis or with compensated cirrhosis. Mavyret is also approved for HCV patients with genotype 1 infection who have been previously treated with a regimen either containing an NS5A inhibitor or an NS3/4A protease inhibitor (but not both). Mavyret was the first eight-week treatment approved for HCV genotypes one through six in adult patients without cirrhosis who have not been previously treated. In 2019, the FDA approved shortening the treatment duration from 12 weeks to eight weeks in treatment-naïve, compensated cirrhotic HCV patients across all genotypes one through six. Mavyret is not approved for use in patients with decompensated cirrhosis. |

Our approach

We are developing AT-787 for the treatment of chronic HCV infection, including patients with decompensated cirrhosis. AT-787 combines AT-527 with a second-generation NS5A inhibitor, AT-777, into a single, oral, pan-genotypic fixed-dose combination therapy. Based on our preclinical and clinical data to date, we believe that AT-787, if approved, could offer the following potential benefits over currently available treatments:

• | Shorten treatment duration to eight weeks in non-cirrhotic and compensated cirrhosis HCV in all genotypes. Current HCV therapies typically require longer dosing in cirrhotic patients to achieve a sustained virologic response (“SVR”), that is close to, but often proportionally lower, than the SVR achieved with shorter treatment of non-cirrhotic patients. |

• | Equivalent antiviral potency across all genotypes, regardless of cirrhotic status, including the difficult to treat genotype-3 population. |

• | Obviate the need for extensive pretreatment assessments required by current treatment options, including genotyping, fibroscan (if cirrhosis is present), and liver function assessment. |

• | Eliminate the need for ribavirin in patients with decompensated cirrhosis. Ribavirin, an antiviral first approved in 1986, carries several FDA boxed warnings, including the risk of hemolytic anemia and teratogenicity. |

• | Well tolerated, with low potential for drug-drug interactions. Mavyret, which carries an FDA warning for cirrhotic patient treatment, is not to be prescribed for patients on atazanavir or rifampin, while Epclusa could cause a slow heart rate when taken with amiodarone. |

18

Clinical development

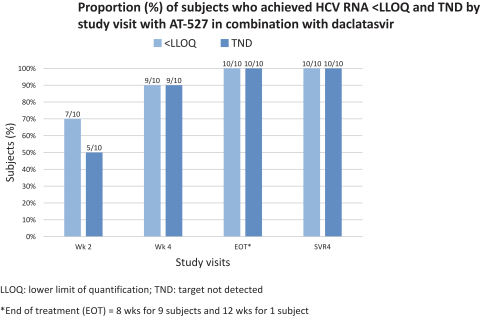

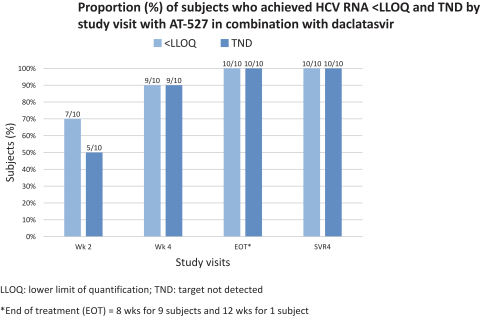

We have completed two clinical trials of AT-527 for the treatment of chronic HCV infection.

Phase 1 clinical trial of AT-527

We conducted a Phase 1 trial to evaluate single and multiple doses of AT-527 as a single agent in healthy and HCV-infected subjects for up to seven days. All HCV-infected subjects were treatment-naïve with HCV RNA ≥ 5 log10 IU/mL. The objectives of the trial were to assess safety, tolerability, PK and antiviral activity.