ABBREVIATIONS

| Abbreviations | Meaning |

| AFP | Administradora de Fondo de Pensiones or Private Pension Funds Administrators |

| AI | Artificial Inteligence |

| ALCO | Asset and Liabilities Committee |

| ALM | Asset and Liabilities Management |

| AML | Anti-Money Laundering |

| AMV | Autorregulador del Mercado de Valores de Colombia or Colombia’s Stock Market Self-regulator |

| ANPDP | Autoridad Nacional de Protección de Datos Personales del Peru or National Authority for the Protection of Personal Data of Peru |

| APS | Autoridad de Fiscalización y Control de Pensiones y Seguros de Bolivia or Supervision and Control Authority for Pensions and Insurance of Bolivia |

| ARRC | Alternative Reference Rates Committee |

| ASB | Atlantic Security Bank, currently ASB Bank Corp. |

| ASBANC | Asociación de Bancos del Peru or Association of Banks of Peru |

| ASFI | Autoridad Supervisora del Sistema Financiero or Financial System Supervisory Authority – Bolivia |

| ASHC | Atlantic Security Holding Corporation |

| ASOMIF | Asociación de Instituciones de Microfinanzas del Peru or Association of Microfinance Institutions of Peru |

| ATM | Automated Teller Machine (cash machine) |

| Bancompartir | Banco Compartir S.A., now Mibanco Colombia |

| BCB | Banco Central de Bolivia or Bolivian Central Bank |

| BCCh | Banco Central de Chile or Chilean Central Bank |

| BCM | Business Continuity Management |

| BCP Bolivia | Banco de Crédito de Bolivia S.A. |

| BCP Consolidated | BCP Consolidated includes BCP Stand-alone, Mibanco and Solución Empresa Administradora Hipotecaria |

| BCP Miami | Banco de Crédito del Peru, Miami Agency |

| BCP Panama | Banco de Crédito del Peru, Panama Branch |

| BCP Stand-alone | Banco de Crédito del Peru including BCP Panama (Panama Branch) and BCP Miami (Miami Agency), but excluding subsidiaries |

| BCRP | Banco Central de Reserva del Peru or Peruvian Central Bank |

| BLMIS | Bernard L. Madoff Investment Securities LLC. |

| BOB | Bolivianos – Bolivian Currency |

| Bps | Basis Points |

| BVL | Bolsa de Valores de Lima or Lima Stock Exchange |

| CAS | Contrato Administrativo de Servicios or Administrative Contracting of Services |

| CCSI | Credicorp Capital Securities Inc. |

| CEO | Chief Executive Officer |

| CET1 | Common Equity Tier I |

| CGU | Cash-Generating Unit |

| CID | Corporate and International Division |

| CIMA | Cayman Islands Monetary Authority |

| CINO | Chief Innovation Officer |

| CLP | Chilean Peso – Chilean Currency |

| CMF | Comisión para el Mercado Financiero or Financial Markets Commission of Chile |

| CODM | Chief Operating Decision Maker |

| CoE | Center Of Excellence |

| COFIDE | Corporación Financiera de Desarrollo S.A. or Peruvian Government-Owned Development Bank |

| CONFIEP | Confederación Nacional de Instituciones Empresariales Privadas or National Confederation of Private Business Institutions in Peru |

| COO | Chief Operating Officer |

| Consolidated Supervision of Financial and Mixed Conglomerates Regulation | SBS Resolution No. 11823-2010, Reglamento para la Supervisión Consolidada de los Conglomerados Financieros y Mixtos |

| COOPACS | Cooperativa de Ahorro y Créditos de Peru or Savings and Loans Associations of Peru |

| COP | Colombian Peso – Colombian Currency |

| COSO | Committee of Sponsoring Organizations of the Treadway Commission |

| CPS | Comisión de Protección Social or Social Protection Committee of Peru |

| CSF | Cybersecurity Framework |

| Credicorp Capital | Credicorp Capital Ltd., formerly Credicorp Investments Ltd. |

| Credicorp Capital Bolsa | Credicorp Capital Sociedad Agente de Bolsa S.A., formerly Credibolsa SAB S.A. |

| Credicorp Capital Chile | Credicorp Capital Chile S.A., operating subsidiary of Credicorp Capital Holding Chile |

| Credicorp Capital Colombia | Credicorp Capital Colombia S.A., formerly Correval S.A. |

| Credicorp Capital Fondos | Credicorp Capital Sociedad Administradora de Fondos S.A., formerly Credifondo SAFI S.A. |

| Credicorp Capital Holding Chile | Credicorp Capital Holding Chile S.A., holding subsidiary of Credicorp Capital Ltd. |

| Credicorp Capital Holding Colombia | Credicorp Capital Holding Colombia S.A.S., holding subsidiary of Credicorp Capital Ltd. |

| Credicorp Holding Colombia | Credicorp Holding Colombia S.A.S., holding subsidiary of Credicorp Ltd., which holds Credicorp Capital Colombia S.A.S. and Mibanco – Banco de la Microempresa de Colombia S.A. |

| Credicorp Capital Holding Peru | Credicorp Capital Holding Peru S.A., holding subsidiary of Credicorp Capital Ltd. |

| Credicorp Capital LLC | Subsidiary of Credicorp Capital USA, resulting from the merger of Ultralat Capital Market Inc. and Credicorp Capital Securities Inc. |

| Credicorp Capital Peru | Credicorp Capital Peru S.A.A., operating subsidiary of Credicorp Capital Holding Peru, and formerly BCP Capital S.A.A. |

| Credicorp Capital Servicios Financieros | Credicorp Capital Servicios Financieros S.A., formerly BCP Capital Financial Services S.A. |

| Credicorp Capital Titulizadora | Credicorp Capital Sociedad Titulizadora S.A., formerly Credititulos S.A. |

| CRS | Common Reporting Standards |

| CTF | Counter-Terrorism Financing |

| Culqi | Compañia Incubadora de Soluciones Moviles S.A. |

| DANE | Departamento Administrativo Nacional de Estadísticas or Colombian National Statistics Bureau |

| D&S | Disability and Survivorship |

| Deposit Insurance Fund | Fondo de Seguro de Depósitos or Deposit Insurance Fund of Peru |

| DIAN | Dirección de Impuestos y Aduanas Nacionales de Colombia or Taxes and National Customs Authority of Colombia |

| DTA | Deferred Tax Assets |

| Edpymes | Empresas de Crédito or Small and Micro Firm Development Institution, formerly Empresas de Desarrollo de Pequeña y Microempresa (Legislative Decree No. 1531) |

| Edyficar | Empresa Financiera Edyficar S.A. – Peru |

| EIR | Effective Interest Rate |

| Encumbra | Empresa Financiera Edyficar S.A.S. – Colombia |

| EPS | Entidad Prestadora de Salud or Health Care Facility |

| ENPS | Employee Net Promoter Score |

| ES Act | Economic Substance Act 2018 (as amended) of Bermuda |

| EY | Ernst & Young LLP |

| FAE | Fondo de Apoyo Empresarial del Peru or Business Support Fund of Peru |

| FAE-Mype | Fondo de Apoyo Empresarial a la Mype del Peru or SME Business Support Fund of Peru |

| FATCA | Foreign Account Tax Compliance Act |

| FCA | Financial Conduct Authority – United Kingdom |

| FED | Board of Governors of the U.S. Federal Reserve System |

| FFIEC | Federal Financial Institutions Examination Council |

| FIBA | Financial and International Business Association, formerly Florida International Bankers Association |

| FINRA | Financial Industry Regulatory Authority – US |

| Fintech | Financial Technology |

| FMV | Fair market value |

| Fondemi | Fondo de Desarrollo de la Microempresa del Peru or SMEs Development Fund of Peru |

| GAAP | Generally Accepted Accounting Principles |

| GDP | Gross Domestic Product |

| GMV | Gross Merchant Volume |

| Grupo Pacífico | Pacífico Compañía de Seguros y Reaseguros S.A. and consolidated subsidiaries |

| IASB | International Accounting Standards Board |

| IBA | ICE Benchmark Administration Limited |

| IBNR | Incurred but not reported |

| ICBSA | Inversiones Credicorp Bolivia S.A. |

| INDECOPI | Instituto Nacional de Defensa de la Competencia y de la Protección de la Propiedad Intelectual del Peru or National Institute for the Defense of Competition and the Protection of Intellectual Property |

| IFRS | International Financial Reporting Standards |

| IGA | Intergovernmental Agreements |

| IIA | Institute of Internal Auditors |

| IMF | International Monetary Fund |

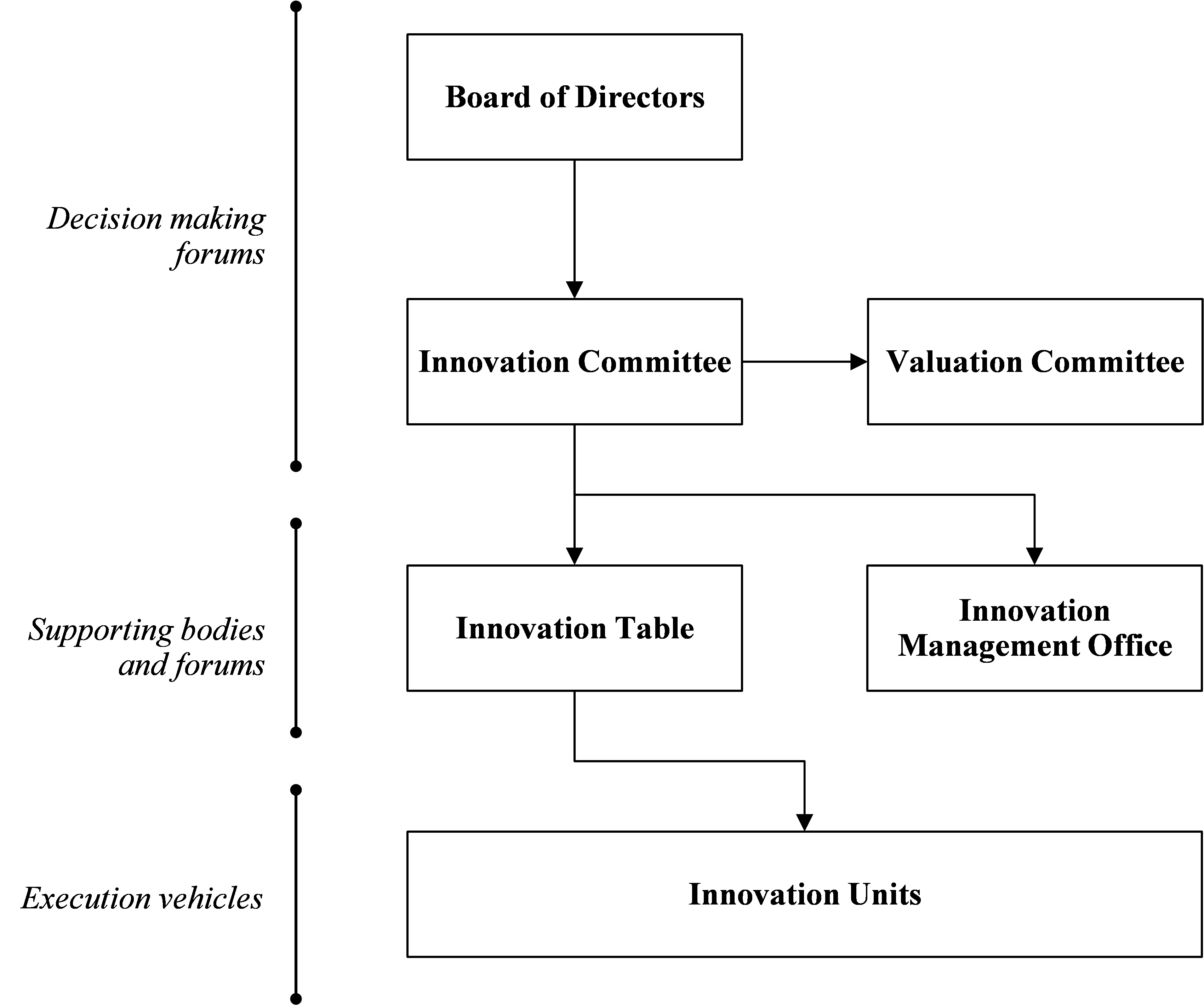

| IMO | Innovation Management Office |

| INE | Instituto Nacional de Estadística or National Statistics Institute of Chile |

| INEI | Instituto Nacional de Estadística e Informática or Peruvian National institute of Statistic and Informatics |

| IPO | Initial Public Offering |

| IRS | Internal Revenue Service |

| ISACA | Information Systems Audit and Control Association |

| IT | Information Technology |

| IUs | Innovation Units |

| KRI | Key Risk Indicators |

| LCR | Liquidity Coverage Ratio |

| LGD | Loss Given Default |

| LIBOR | London Interbank Offered Rate |

| LoB | Lines of Business |

| LTV | Loan to Value |

| MEF | Ministry of Economy and Finance of Peru |

| Merger Control Law | Law No. 31112, Ley que establece el control previo de operaciones de concentración empresarial |

| Mibanco | Mibanco, Banco de la Microempresa S.A. |

| Mibanco Colombia | Mibanco, Banco de la Microempresa de Colombia S.A. |

| MMD | Middle-Market Banking Division |

| Mype | Micro y Pequeña Empresa or Micro and Small Enterprise |

| NIM | Net Interest Margin |

| NIST | National Institute of Standards and Technology |

| NPS | Net Promoter Score |

| NYSE | New York Stock Exchange |

| OECD | Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development |

| P&C | Property and Casualty |

| Pacífico Seguros | Pacífico Compañía de Seguros y Reaseguros S.A. |

| PEN | Peruvian Sol (S/) – Peruvian Currency |

| Peruvian Banking and Insurance Law | Law No. 26702, Ley General del Sistema Financiero y del Sistema de Seguros y Orgánica de la Superintendencia de Banca y Seguros |

| PPS | Peruvian Private Pension System |

| RBG | Retail Banking Group |

| ROAA | Return on Average Assets |

| ROAE | Return on Average Equity |

| ROE | Return on Equity |

| RWAs | Risk-Weighted Asset |

| S&P | Standard and Poor’s |

| SBP | Superintendencia de Bancos de Panama or Superintendency of Banks of Panama |

| SBS | Superintendencia de Banca, Seguros y Administradoras Privadas de Fondos de Pensiones or Superintendence of Banks, Insurance and Pension Funds – Peru |

| SCTR | Seguro Complementario de Trabajo de Riesgo or Complementary Work Risk Insurance |

| SEAH | Solución Empresa Administradora Hipotecaria S.A. |

| SEC | U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission |

| SFC | Superintendencia Financiera de Colombia or Financial Superintendence of Colombia |

| SME | Small and Medium Enterprise |

| SME – Business | SME-Business Credicorp Segment |

| SME – Pyme | SME-Pyme Credicorp Segment |

| SMV | Superintendencia del Mercado de Valores or Superintendence of the Securities Market – Peru |

| SOFR | Secured Overnight Financing Rate |

| SUNAT | Superintendencia Nacional de Aduanas y de Administración Tributaria or Superintendence of Tax Administration – Peru |

| SUSALUD | Superintendencia Nacional de Salud del Peru or National Health Superintendence of Peru |

| Soles | Peruvian currency (S/ - PEN) |

| Tenpo | Tenpo SpA (formerly Krealo SpA) |

| Tyba | Credicorp Capital Negocios Digitales S.A.S. |

| U.S. Dollar | United States currency (also $, US$, Dollars or U.S. Dollars) |

| USA | United States of America (USA, U.S.A., US or U.S.) |

| USDBOB | Currency exchange rate between the U.S. Dollar and the Bolivian Boliviano |

| USDPEN | Currency exchange rate between the U.S. Dollar and the Peruvian Sol |

| Usury Law Regulation | Peruvian Law No. 31143, Ley que protege de la usura a los consumidores de los servicios financieros |

| VaR | Value at Risk |

| VAT | Value-added tax |

| Wally | Wally POS S.A.C. |

| WBG | Wholesale Banking Group |

| WHO | World Health Organization |

| WTI | West Texas Intermediate |

PRESENTATION OF FINANCIAL INFORMATION

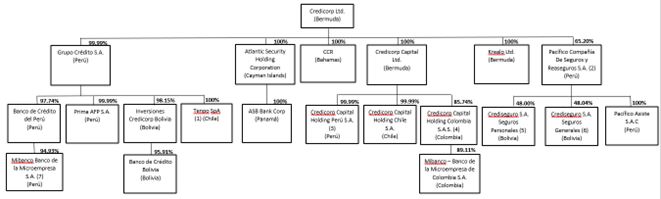

Credicorp Ltd. is a Bermuda exempted company (and is referred to in this Annual Report as Credicorp, the Company, the Group, we, or us, each of which means either Credicorp Ltd. as a separate entity or as an entity together with our consolidated subsidiaries, as the context may require). We maintain our financial books and records in Peruvian Soles and present our financial statements in accordance with International Financial Reporting Standards (IFRS), as issued by the International Accounting Standards Board (IASB). IFRS differ in certain respects from Generally Accepted Accounting Principles (GAAP) in the United States.

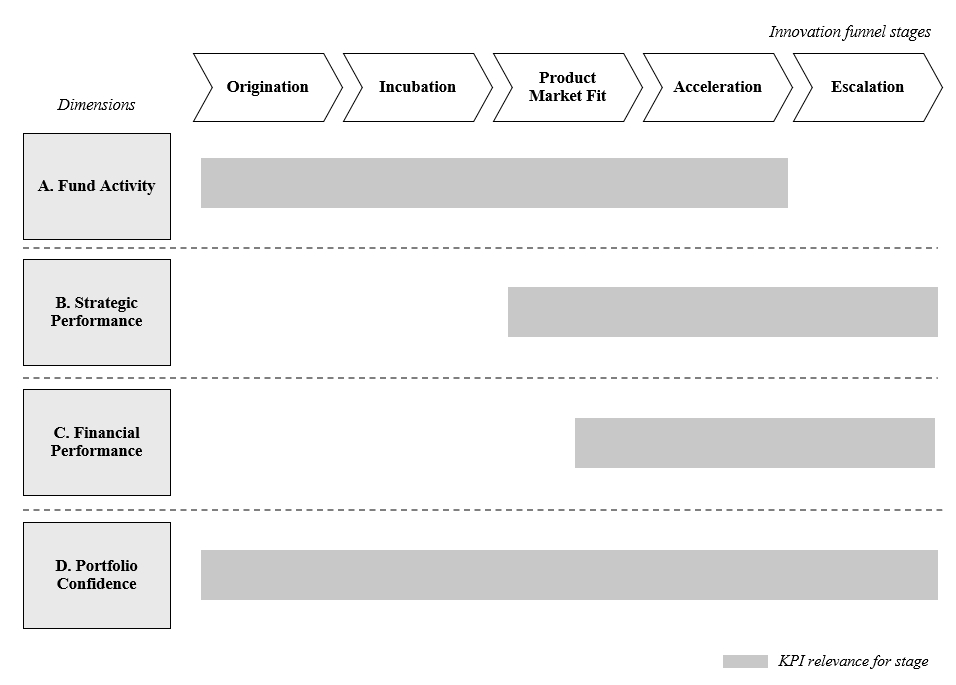

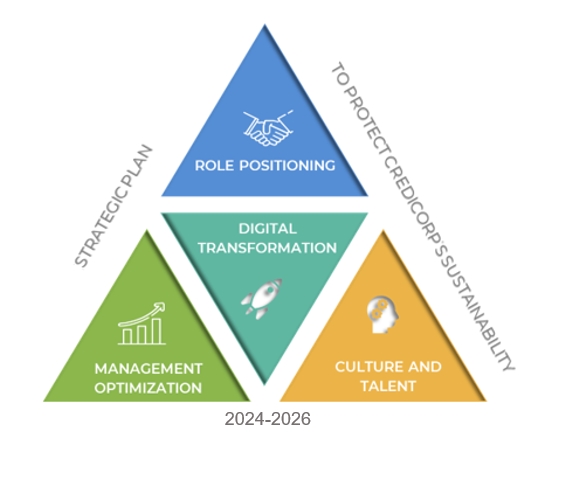

We operate primarily through our four lines of business (LoBs): Universal Banking, Microfinance, Insurance & Pensions, and Investment Management & Advisory. Additionally, we complement the operations of our LoBs through our innovation portfolio which is managed by the Innovation Committee at a corporate level. For more information about our innovation portfolio and strategy, please review “ITEM 4. INFORMATION ON THE COMPANY – 4.B Business Overview – (1) Credicorp Overview – Our Innovation Strategy”.

Our eight main operating subsidiaries are:

| • | Within Universal Banking: (i) Banco de Crédito del Peru S.A. (BCP Stand-alone), a Peruvian financial institution; and (ii) Banco de Crédito de Bolivia S.A. (BCP Bolivia) a commercial bank that operates in Bolivia and that we hold through Inversiones Credicorp Bolivia S.A. (ICBSA); |

| • | Within Microfinance: (iii) Mibanco, Banco de la Microempresa S.A. (Mibanco), a Peruvian banking entity oriented toward the micro and small business sector; and (iv) Mibanco – Banco de la Microempresa de Colombia S.A. (Mibanco Colombia), which resulted from the merger between Banco Compartir S.A. (Bancompartir) and Edyficar S.A.S. (Encumbra), which we hold through Credicorp Holding Colombia S.A.S.; |

| • | Within Insurance and Pensions: (v) Pacífico Compañía de Seguros y Reaseguros S.A. (Pacífico Seguros and, together with its consolidated subsidiaries, Grupo Pacífico), an entity that contracts and manages all types of general risk and life insurance, reinsurance and property investment and financial operations; and (vi) Prima AFP, a private pension fund; and |

| • | Finally, within Investment Management and Advisory: (vii) Credicorp Capital Ltd. (together with its subsidiaries) was formed in 2012, and (viii) ASB Bank Corp., resulted from the merger between ASB Bank Corp. and Atlantic Security Bank, which we hold through Atlantic Security Holding Corporation (ASHC). |

For information about these LoBs, see “ITEM 4. INFORMATION ON THE COMPANY – 4.B Business Overview – (2) Lines of Business (LoBs)”.

As of and for the year ended December 31, 2023, BCP Stand-alone represented 75.8% of our total assets and 77.0% of our equity attributable to Credicorp’s equity holders (that is, its shareholders). Unless otherwise specified, the financial information for BCP Stand-alone, BCP Bolivia, Mibanco, Mibanco Colombia, ASB Bank Corp., Grupo Pacífico, Prima AFP and Credicorp Capital included in this Annual Report is presented in accordance with IFRS and before eliminations for consolidation purposes. See “ITEM 3. KEY INFORMATION – 3.A Selected Financial Data” and “ITEM 4. INFORMATION ON THE COMPANY – 4.A History and Development of the Company”. We refer to BCP Stand-alone, BCP Bolivia, Mibanco, Mibanco Colombia, Grupo Pacífico, Prima AFP, Credicorp Capital and ASB as our main operating subsidiaries.

“ITEM 3. KEY INFORMATION – 3.A Selected Financial Data” contains key information related to our performance. This information was obtained mainly from our consolidated financial statements as of December 31, 2021, 2022 and 2023.

Unless otherwise specified or the context otherwise requires, references in this Annual Report to “S/”, “Sol”, “local currency” or “Soles” are to Peruvian Soles (each Sol is divided into 100 centimos (cents)), and references to “$”, “US$,” “Dollars”, “US Dollars” or “U.S. Dollars” are to United States Dollars. In addition, references to USDPEN are the currency exchange rate between the U.S. Dollar and the Peruvian Sol.

Some of our subsidiaries, namely Atlantic Security Holding and five of its subsidiaries (Atlantic Security International Financial Services Inc (ASIF), ASB Bank Corp., Atlantic Private Equity Investment Advisor, Atlantic Security Private Equity General Partner and Credicorp Capital Cayman GP), Credicorp Capital USA Inc. (with its subsidiaries Credicorp Capital Advisors LLC. and Credicorp Capital LLC.) and Credicorp Capital Asset Management Administradora General de Fondos maintain their operations and balances in US Dollars and other currencies. As a result, in certain instances throughout this Annual Report, we have translated US Dollars and other currencies to Soles. You should not construe any of these translations as representations that the US Dollar amounts actually represent such equivalent Sol amounts or that such US Dollar amounts could be converted into Soles at the rate indicated, as of the dates mentioned herein, or at all. Unless otherwise indicated, these Sol amounts have been translated from US Dollar amounts at an exchange rate of S/3.709= US$1.00, which is the December 31, 2023 exchange rate set by the Peruvian Superintendence of Banks, Insurance and Pension Funds (Superintendencia de Banca, Seguros y Administradoras Privadas de Fondos de Pensiones or SBS by its Spanish initials), S/3.814 and S/3.987 per dollar as of December 31, 2022 and 2021, respectively. Converting US Dollars to Soles on a specified date (at the prevailing exchange rate on that date) may result in the presentation of Sol amounts that are different from the Sol amounts that would result by converting the same amount of US Dollars on a different specified date (at the prevailing exchange rate on such date). Our Bolivian subsidiary operates in Bolivianos (BOB). For consolidation purposes, our Bolivian subsidiary’s financial statements are also presented in Soles. Likewise, our Panamanian subsidiaries (BCP Panama and ASB) present financial statements in Balboas (PAB). Our Colombian and Chilean subsidiaries operate in Colombian Pesos (COP) and Chilean Pesos (CLP), respectively, and their financial statements are also converted into Soles for consolidation purposes.

Our management’s criteria for translating foreign currency, for the purpose of preparing Credicorp’s consolidated financial statements, are described in “ITEM 5. OPERATING AND FINANCIAL REVIEW AND PROSPECTS – 5.A Operating Results – (3) Material Accounting Policies – 3.3 Functional, presentation and foreign currency transactions”.

CAUTIONARY STATEMENT WITH RESPECT TO FORWARD-LOOKING STATEMENTS

Certain statements contained in this Annual Report are not historical facts, including, without limitation, certain statements made in the sections titled “ITEM 3. KEY INFORMATION”, “ITEM 4. INFORMATION ON THE COMPANY”, “ITEM 5. OPERATING AND FINANCIAL REVIEW AND PROSPECTS” and “ITEM 11. QUANTITATIVE AND QUALITATIVE DISCLOSURES ABOUT RISK MANAGEMENT”, which are forward-looking statements within the meaning of Section 27A of the U.S. Securities Act of 1933, as amended, and Section 21E of the U.S. Securities Exchange Act of 1934, as amended (the Exchange Act). You can find many of these statements by looking for words such as “believes”, “expects”, “anticipates”, “estimates”, “intends”, “plans”, “goal”, “seek”, “project”, “strategy”, “future”, “likely”, “should”, “will”, “would”, “may”, or other similar expressions referring to future periods.

Forward-looking statements are based only on our management’s current views and assumptions and involve known and unknown risks and uncertainties that could cause actual results, performance, or events to differ materially from those expressed or implied in the forward-looking statements. Therefore, actual results, performance, or events may be materially different from those in the forward-looking statements due to, without limitation, the following factors:

| a) | Economic conditions and regulatory framework in Peru and markets in which we operate; |

| b) | The occurrence of natural disasters or political or social instability in Peru and markets in which we operate; |

| c) | The adequacy of the dividends that our subsidiaries are able to pay to us, which may affect our ability to pay dividends to shareholders and corporate expenses; |

| d) | Performance of, and volatility in, financial markets, including in Latin America and other emerging markets; |

| e) | The frequency, severity, and types of insured loss events; |

| f) | Fluctuations in interest rate and liquidity levels; |

| g) | Foreign currency exchange rates, including the Sol/US Dollar exchange rate; |

| h) | Deterioration in the quality of our loan portfolio; |

| i) | Increasing levels of competition in Peru and markets in which we operate; |

| j) | Developments and changes in laws and regulations affecting the financial sector and adoption of new international guidelines; |

| k) | Changes in the policies of central banks and/or foreign governments; |

| l) | Effectiveness of our risk management policies and of our operational and security systems; |

| m) | Emerging cybersecurity and environmental risks; |

| n) | Losses associated with counterparty exposures; |

| o) | Public health crises beyond our control; |

| p) | Changes in Bermuda laws and regulations applicable to so-called non-resident entities; and |

| q) | International geopolitical tensions and conflict. |

See “ITEM 3. KEY INFORMATION - 3.D Risk Factors” and “ITEM 5. OPERATING AND FINANCIAL REVIEW AND PROSPECTS” for additional information and other such factors.

Any forward-looking statement made by us in this Annual Report is based only on information currently available to us and is made only as of the date on which it is made, and you are cautioned not to place any undue reliance on any such statement. We are not under any obligation to, and we expressly disclaim any obligation to, update or alter any forward-looking statements contained in this Annual Report, whether as a result of new information, future events or otherwise.

| ITEM 1. | IDENTITY OF DIRECTORS, SENIOR MANAGEMENT AND ADVISERS |

Not applicable.

| ITEM 2. | OFFER STATISTICS AND EXPECTED TIMETABLE |

Not applicable.

| 3. A | Selected Financial Data |

The following table presents a summary of our consolidated financial information at the dates and for the periods indicated. This selected financial data is presented in Soles. You should read this information in conjunction with and qualify this information in its entirety by reference to, the consolidated financial statements, which are also presented in Soles.

The summary of our consolidated financial data as of and for the years ended December 31, 2021 and 2022 (restated), is derived from the consolidated financial statements audited by Gaveglio, Aparicio y Asociados S.C.R.L, a member firm of PricewaterhouseCoopers International Limited; and the summary of our consolidated financial data as of December 2023, and for the year ended, is derived from the consolidated financial statements audited by Tanaka, Valdivia y Asociados S.C.R.L member firm of Ernst & Young Global, both independent registered public accountants.

The consolidated financial statements as of and for the year ended on December 31, 2022, including their opening balance as of January 1, 2022, which are presented for comparative purposes, have been restated due to the initial implementation of IFRS 17, Insurance Contracts. For further detail please refer to note 3b on the 2023 Audited Financial Statements.

The report of Gaveglio, Aparicio y Asociados S.C.R.L on the consolidated financial statements as of and for the year ended on December 31, 2021 and 2022 (restated) and the report of Tanaka, Valdivia y Asociados S.C.R.L on the consolidated financial statements as of and for the year ended December 31, 2023 appear elsewhere in this Annual Report.

SELECTED FINANCIAL DATA

| | | As of and for the year ended December 31, | |

| | | 2021 | | | | 2022(*) |

| | | 2023 | | | | 2023 | |

| | | (In thousands of Soles, except percentages, ratios, and per common share data) | | | In thousands of US Dollars (1) | |

| INCOME STATEMENT DATA: | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | |

| IFRS: | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | |

| Interest and similar income | | | 11,850,406 | | | | 15,011,282 | | | | 18,798,495 | | | | 5,034,412 | |

| Interest and similar expenses | | | (2,490,802 | ) | | | (3,919,664 | ) | | | (5,860,523 | ) | | | (1,569,503 | ) |

| Net Interest, similar income and expenses | | | 9,359,604 | | | | 11,091,618 | | | | 12,937,972 | | | | 3,464,909 | |

| Provision for credit losses on loan portfolio | | | (1,558,951 | ) | | | (2,158,555 | ) | | | (3,957,143 | ) | | | (1,059,760 | ) |

| Recoveries of written-off loans | | | 346,728 | | | | 347,017 | | | | 334,798 | | | | 89,662 | |

| Provision for credit losses on loan portfolio, net of recoveries | | | (1,212,223 | ) | | | (1,811,538 | ) | | | (3,622,345 | ) | | | (970,098 | ) |

| Net interest, similar income and expenses, after provision for credit losses on loan portfolio | | | 8,147,381 | | | | 9,280,080 | | | | 9,315,627 | | | | 2,494,811 | |

| Commissions and fees | | | 3,493,734 | | | | 3,642,857 | | | | 3,804,459 | | | | 1,018,870 | |

| Net gain on foreign exchange transactions | | | 922,917 | | | | 1,084,151 | | | | 886,126 | | | | 237,313 | |

| Net gain on securities | | | 28,650 | | | | 5,468 | | | | 425,144 | | | | 113,858 | |

| Net gain on derivatives held for trading | | | 221,064 | | | | 65,187 | | | | 53,665 | | | | 14,372 | |

| Net result from exchange differences | | | (3,215 | ) | | | 387 | | | | 45,778 | | | | 12,260 | |

| Other income | | | 266,567 | | | | 268,046 | | | | 440,653 | | | | 118,011 | |

| Total non-interest income | | | 4,929,717 | | | | 5,066,096 | | | | 5,655,825 | | | | 1,514,684 | |

| Insurance service result | | | - | | | | 1,302,347 | | | | 1,602,421 | | | | 429,143 | |

| Underwriting result | | | - | | | | (460,899 | ) | | | (391,321 | ) | | | (104,799 | ) |

| Net premiums earned | | | 2,671,530 | | | | - | | | | - | | | | - | |

| Net claims incurred for life, general and health insurance contracts | | | (2,341,917 | ) | | | - | | | | - | | | | - | |

| Acquisition cost | | | (333,334 | ) | | | - | | | | - | | | | - | |

Total other expenses (2) | | | (7,740,561 | ) | | | (8,317,013 | ) | | | (9,334,223 | ) | | | (2,499,792 | ) |

| Profit before income tax | | | 5,332,816 | | | | 6,870,611 | | | | 6,848,329 | | | | 1,834,047 | |

| Income tax | | | (1,660,987 | ) | | | (2,110,501 | ) | | | (1,888,451 | ) | | | (505,745 | ) |

| Net profit | | | 3,671,829 | | | | 4,760,110 | | | | 4,959,878 | | | | 1,328,302 | |

| Attributable to: | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | |

| Credicorp’s equity holders | | | 3,584,582 | | | | 4,647,818 | | | | 4,865,540 | | | | 1,303,037 | |

| Non-controlling interest | | | 87,247 | | | | 112,292 | | | | 94,338 | | | | 25,265 | |

Number of shares as adjusted to reflect changes in capital (3) | | | 79,531,948 | | | | 79,533,094 | | | | 79,496,221 | | | | - | |

Net basic earnings per common share attributable to Credicorp’s equity holders (4) | | | 45.09 | | | | 58.26 | | | | 61.22 | | | | 16.40 | |

Net dilutive earnings per common share attributable to Credicorp’s equity holders (4) | | | 44.99 | | | | 58.13 | | | | 61.08 | | | | 16.36 | |

Cash dividends declared per common share Soles (5) | | | 15.00 | | | | 25.00 | | | | - | | | | - | |

(*) Balances corresponding to 2022 have been restated according to IFRS 17. For further detail please refer to note 3b on the 2023 Audited Financial Statements.

| | | As of and for the year ended December 31, | |

| | | 2021 | | | | 2022 ( | *) | | | 2023 | | | | 2023 | |

| | | (In thousands of Soles, except percentages, ratios, and per common share data) | | | In thousands of US Dollars (1) | |

| STATEMENT OF FINANCIAL POSITION DATA: | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | |

| IFRS: | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | |

| Total assets | | | 244,846,740 | | | | 235,414,157 | | | | 238,840,188 | | | | 64,394,766 | |

Total loans (6) | | | 147,597,412 | | | | 148,626,374 | | | | 144,976,051 | | | | 39,087,638 | |

| Allowance for loan losses | | | (8,477,308 | ) | | | (7,872,402 | ) | | | (8,277,916 | ) | | | (2,231,846 | ) |

Total deposits (7) | | | 149,596,545 | | | | 147,020,787 | | | | 147,704,994 | | | | 39,823,401 | |

| Equity attributable to Credicorp’s equity holders | | | 26,496,767 | | | | 29,003,644 | | | | 32,460,004 | | | | 8,751,686 | |

| Non-controlling interest | | | 540,672 | | | | 591,569 | | | | 647,061 | | | | 174,457 | |

| Total equity | | | 27,037,439 | | | | 29,595,213 | | | | 33,107,065 | | | | 8,926,143 | |

| | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | |

(*) Balances corresponding to 2022 have been restated according to IFRS 17. For further detail please refer to note 3b on the 2023 Audited Financial Statements.

| | | As of and for the year ended December 31, | |

| | | 2021 | | | | 2022 ( | *) | | | 2023 | |

| | | | | | | | | | | | |

| SELECTED RATIOS | | | | | | | | | | | |

| IFRS: | | | | | | | | | | | |

Net interest margin (NIM) (8) | | | 4.12 | % | | | 5.09 | % | | | 6.01 | % |

Return on average total assets (ROAA) (9) | | | 1.49 | % | | | 1.97 | % | | | 2.01 | % |

Return on average equity (ROAE) (10) | | | 13.94 | % | | | 16.81 | % | | | 15.83 | % |

Operating efficiency (11) | | | 44.95 | % | | | 47.50 | % | | | 46.08 | % |

Operating expenses as a percentage of average assets (12) | | | 3.12 | % | | | 3.27 | % | | | 3.64 | % |

| Equity attributable to Credicorp’s equity holders as a percentage of period end total assets | | | 10.82 | % | | | 12.32 | % | | | 13.59 | % |

Regulatory capital as a percentage of risk weighted assets – BIS ratio (13) | | | 16.71 | % | | | 19.31 | % | | | 18.59 | % |

Total internal overdue loan amounts as a percentage of total loans (14) | | | 3.77 | % | | | 4.00 | % | | | 4.23 | % |

| Allowance for direct loan losses as a percentage of total loans | | | 5.74 | % | | | 5.30 | % | | | 5.71 | % |

Allowance for loan losses as a percentage of total loans and other off-balance-sheet items (15) | | | 4.97 | % | | | 4.64 | % | | | 5.02 | % |

Allowance for direct loan losses as a percentage of total internal overdue loans (16) | | | 152.40 | % | | | 132.54 | % | | | 135.12 | % |

Allowance for direct loan losses as a percentage of impaired loans (17) | | | 75.13 | % | | | 73.79 | % | | | 75.82 | % |

Dividend payout ratio (18) | | | 33.27 | % | | | 42.78 | % | | | - | |

Equity to assets ratio (19) | | | 10.21 | % | | | 10.46 | % | | | 12.92 | % |

Shareholders’ equity to assets ratio (20) | | | 10.41 | % | | | 10.24 | % | | | 13.18 | % |

(*) Balances corresponding to 2022 have been restated according to IFRS 17. For further detail please refer to note 3b on the 2023 Audited Financial Statements.

Note: Total internal overdue loans include overdue and under legal collection loans.

| (1) | Translated for convenience only from Sol amounts to US Dollar amounts using exchange rates of S/3.709 = US$1.00, which is the December 31, 2023 exchange rate set by the SBS, for statement of financial position data and of S/3.734 = US$1.00, which is the average exchange rate on a monthly basis in 2023, for income statement data (for consistency with the annual amounts being translated). |

| (2) | Total other expenses include salaries and employee benefits, administrative expenses, depreciation and amortization, depreciation for right-of-use assets, impairment loss on goodwill and others. |

| (3) | The number of shares consists of capital stock (see Note 16(a) to the consolidated financial statements) less treasury stock (see Note 16 (b) to the consolidated financial statements). |

| (4) | Basic earnings per share is calculated by dividing the net profit for the year attributable to Credicorp’s equity holders by the weighted average number of ordinary shares outstanding during the year, excluding the average number of ordinary shares purchased and held as treasury stock (see Note 26 to the consolidated financial statements). Dilutive earnings per share is calculated by dividing by the weighted average number of ordinary shares outstanding during the year, including the average number of ordinary shares purchased and held as treasury stock. |

| (5) | Dividends declared per share based on net profit attained for the financial years 2021 and 2022 were declared in Soles and paid in US Dollars on June 10, 2022, and June 09, 2023, respectively, using the weighted exchange rate registered by the SBS for the transactions at the close of business on June 08, 2022, and June 07, 2023, respectively. As of the date of this Annual Report, no dividends have been declared in 2024. |

| (6) | “Total loans” refers to direct loans, internal overdue loans and under legal collection loans and accrued interest. See Note 7 to the consolidated financial statements. |

| (7) | Total deposits exclude interest payable. See Note 13 to the consolidated financial statements. |

| (8) | Net interest similar income and expenses as a percentage of average interest-earning assets, computed as the average of period-beginning and period-ending balances. |

| (9) | Net profit attributable to Credicorp’s equity holders as a percentage of average total assets, computed as the average of period-beginning and period-ending balances. |

| (10) | Net profit attributable to Credicorp’s equity holders as a percentage of average equity attributable to our equity holders, computed as the average of period-beginning and period-ending balances. |

| (11) | Sum of salaries and employee benefits, administrative expenses, depreciation and amortization, acquisition cost and association in participation, all as percentage of the sum of net interest income, commissions and fees, net gain from exchange differences, net gain in associates, net premiums earned, net gain on foreign exchange transactions and net result on derivatives held for trading. Acquisition cost includes net fees, underwriting expenses and underwriting income. |

| (12) | Sum of salaries and employee benefits, administrative expenses, depreciation and amortization and acquisition cost, all as percentage of average total assets. |

| (13) | Regulatory capital calculated in accordance with guidelines established by the Basel Committee on Banking Regulations and Supervisory Practices of International Settlements (Basel Committee Accord) as adopted by the SBS. See “ITEM 5. OPERATING AND FINANCIAL REVIEW AND PROSPECTS – 5.B Liquidity and Capital Resources - (1) Capital Adequacy Requirements for Credicorp.” |

| (14) | Depending on the type of loan, BCP Stand-alone and Mibanco consider corporate, large business and medium business loans to be internal overdue loans for after 15 days; and overdrafts, small and micro business to be internal overdue loans after 30 days. For consumer, mortgage and leasing loans the past-due installments are considered internal overdue after 30 to 90 days and after 90 days, the outstanding balance of the loan is considered internal overdue. ASB considers internal overdue loans all overdue loans when the scheduled principal and/or interest payments are overdue for more than 30 days. BCP Bolivia considers loans as internal overdue after 30 days. |

| (15) | Other off-balance-sheet items primarily consist of guarantees and stand-by letters, performance bonds, and import and export letters of credit. See Note 18 to the consolidated financial statements. |

| (16) | Allowance for direct loan losses, as a percentage of all internal overdue loans without accounting for collateral securing such loans. |

| (17) | Allowance for direct loan losses as a percentage of direct loans classified as impaired debt. See “ITEM 4. INFORMATION ON THE COMPANY - 4.B Business Overview – (7) Selected Statistical Information – 7.3 Loan Portfolio – 7.3.7 Classification of the Loan Portfolio”. |

| (18) | Dividends declared based on net profit attained for the financial years 2021 and 2022 divided by net profit attributable to our equity holders of the year 2021 and 2022, respectively. Dividends for 2023 results have not been declared yet. |

| (19) | Average equity attributable to our equity divided by average total assets, both averages computed as the average of month-ending balances. |

| (20) | Average equity attributable to our equity shareholders divided by average total assets, both averages computed as the average of month-ending balances. |

| 3. B | Capitalization and Indebtedness |

Not applicable.

| 3. C | Reasons for the Offer and Use of Proceeds |

Not applicable.

Our businesses are affected by many internal and external factors in the markets in which we operate. Different risk factors can impact our businesses, our ability to operate effectively and our business strategies. You should consider the risk factors carefully and read them in conjunction with all the information in this document. You should note that these risk factors described below are not the only risks to consider. Rather, these are the risks that we currently consider material. There may be additional risks that we consider immaterial or of which we are unaware, and any of these risks could have similar effects to those set forth below.

Credicorp is exposed to the following macroeconomic, legal and regulatory, industry and market, business performance, operational and environmental and social and governance risks:

| • | Our geographic location exposes us to Peruvian political, social and economic conditions. |

| • | Our banking and capital market operations in neighboring countries expose us to political and economic conditions in those countries. |

| • | Economic and market conditions in other countries may affect the Peruvian economy and the market price of Peruvian securities. |

| • | Geopolitical tensions and conflicts, including the conflict between Russia and Ukraine, and between Israel and Palestine, could have economic effects that negatively impact the Peruvian economy. |

| • | Regulatory changes and the adoption of new international guidelines to sectors in which we operate could impact our earnings and adversely affect our operating performance. |

| • | Credicorp, as a Bermuda exempted company, may be adversely affected by any change in Bermuda law or regulation. |

| • | It may be difficult to serve process on or enforce judgments against us or our principals residing outside of the United States or to assert claims against our officers or Directors. |

| • | We operate in a competitive environment that may limit our potential to grow, put pressure on our margins and reduce our profitability. |

| • | Our business and results of operations could be negatively impacted by a public health crises beyond our control. |

| • | Our financial statements, particularly our interest-earning assets and interest-bearing liabilities, could be exposed to fluctuations in interest rates, foreign currency exchange rates and exchange controls, which may adversely affect our financial condition and results of operations. |

| • | Our liquidity, business activities and profitability may be adversely affected by an inability to access the debt capital markets or to sell assets during periods of market-wide or firm-specific liquidity constraints. |

| • | The Group relies significantly on its deposits for funding. |

| • | Our investments measured at fair value through profit or loss and fair value through other comprehensive income expose us to market price volatility, liquidity declines and fluctuations in foreign currency exchange rates, which may result in losses that could adversely affect our business, financial condition and operating results. In addition, our investments measured at amortized cost may expose us to market price volatility and liquidity shortcomings if sales of those investments become required for liquidity purposes. |

| • | A deterioration in the quality of our loan portfolio may adversely affect our results of operations. |

| • | Errors or inaccuracies in risk models can generate adverse economic impacts. |

| • | Accurate underwriting and setting of premiums are important risk management tools for primary insurance companies, including Grupo Pacífico, and the estimates underlying our underwriting and premiums may be inaccurate. |

| • | While reinsurance is an important tool in risk management of any primary insurance company that enables risk diversification that in turn helps to reduce losses, we face the possibility that the reinsurance companies will be unable to honor their contractual obligations. |

| • | Risks not contemplated in our insurance policies may affect our results of operations. |

| • | Acquisitions and strategic partnerships may not perform as expected, which could have an adverse effect on our business, financial condition, and results of operations. |

| • | Credicorp’s increasing investments in digital transformation and disruptive initiatives may fail to achieve the ambitions, efficiencies and other performance improvements that we are pursuing. |

| • | Our ability to pay dividends to shareholders and to pay corporate expenses may be adversely affected by the ability of our subsidiaries to pay dividends to us. |

| • | A failure in, or breach of, our operational or security systems, fraud by employees or outsiders, other operational errors, or the failure of our system of internal controls to discover and rectify such matters could temporarily interrupt our businesses, increasing our costs and causing losses. |

| • | Our anti-money laundering and counter-terrorist financing measures might not prevent third parties from using us as a conduit for such activities, which could damage our reputation or expose us to fines, sanctions or legal enforcement, any of which could have a material adverse effect on our business, financial condition, and results of operations. |

| • | Natural disasters in Peru could disrupt our businesses and adversely affect our results of operations and financial condition. |

| • | We may incur financial losses and damages to our reputation from environmental, social and governance (ESG) risks. In recent years, these risks have been recognized as increasingly relevant since they can affect the creation of long-term value for stakeholders of the Company. |

Our geographic location exposes us to risks related to Peruvian political, social and economic conditions.

Most operations of BCP Stand-alone, Grupo Pacífico, Prima AFP, and a significant part of Credicorp Capital’s and Mibanco operations are located in Peru. In addition, while ASB Bank Corp. is based in Panama rather than in Peru, most of its customers are located in Peru. Therefore, our results primarily depend on economic activity in Peru. Changes in economic conditions, both international and domestic, government policies and social uncertainty can alter the financial health and regular development of our businesses. These changes may include, but are not limited to, high inflation, currency depreciation, currency exchange controls, caps on interest rates, confiscation of private property and financial regulation, among others. Similarly, terrorist activity, political and social unrest and corruption scandals can adversely impact our operations, as well as natural disasters.

Peru experienced one of its worst social and political crises in decades after a failed coup on December 7, 2022, by former president Pedro Castillo, triggered and exacerbated massive protests. On the day of a debate by Peru’s Congress on a third motion to impeach Castillo, he announced in a message to the Nation the temporary dissolution of Peru’s Congress, new elections for a Congress with the power to reform Peru’s constitution and the restructuring of Peru’s justice system. The police and armed forces released a joint statement saying that any act contrary to the established constitutional order was a violation of the constitution and that they would not abide by it. Within hours of his speech, Peru’s Congress voted to remove Castillo from office due to moral incapacity and he was arrested on charges of rebellion and conspiracy. In turn, Vice President Dina Boluarte was sworn in as Peru’s first female president and has indicated that she plans to govern until July 2026, which when Castillo’s term would have ended.

Since Boluarte took office, social unrest has exacerbated and erupted, mainly in southern regions of Peru which represent around 15% of Peru’s GDP, where Castillo had more support. Protesters demanded the release from jail of former president Castillo and the holding of new general elections. Protests were violent and resulted in supply chain disruptions due to road blockages, and some regional airports suspended operations temporarily as infrastructure was damaged. Additionally, some mining operations were also disrupted as they faced road blockages and lack of supplies. Furthermore, the protest negatively affected the tourism, hospitality, transportation, construction, and retail sectors.

These protests ended in February 2023. According to the Ombudsman’s office of Peru, the conflict linked to the political crisis caused at least 60 deaths as a result of clashes between civilians, police and military. Since then, other attempts of social protest have not gained much traction. However, there is no assurance as to when our country could face similar social unrest.

In the context of social unrest, on December 12, 2022, an initial bill was approved by Congress to hold early elections in April 2024. Thereafter, political parties asked for a reconsideration of the bill in which the date for the elections was prompted earlier to October 2023. On January 29, 2023, the revisited bill did not obtain the necessary superior majority (87 of 130 votes), which voided the initially approved initiative. Two months later, on March 2023, the executive branch presented another bill for early elections in December 2023, which was again rejected. On June 15, 2023, president Boluarte indicated to press that early elections in 2024 were a ‘closed topic’ and that her government would remain until July 2026, which is the initial date in which Castillo’s term would have ended.

In addition, as with Mr. Castillo’s presidency, president Boluarte has faced challenges in aligning certain initiatives with, and obtaining support from, the Peruvian Congress, which is highly fragmented, as no political party has a clear majority and at least 10 political parties hold minority representations. President Boluarte assumed the presidency with no parliamentary bench as she was expelled from the political party Peru Libre at the beginning of 2021 for not sharing the same ideology. Although it is expected that a majority opposition from the Peruvian Congress against certain policies that may be proposed by the new President will continue, there is a risk of unpredictable policymaking.

Further, should the new President or any official of her administration become involved in corruption investigations or other scandals, popular support for her government and policies may be adversely affected and result in additional disruption to Peru’s political landscape. According to March 2024 Ipsos survey, Ms. Boluarte has a very low approval rate of just 9%. There can be no assurance that future developments in or affecting the Peruvian political landscape, including economic, social or political instability in Peru, will not materially and adversely affect our business, financial condition or results of operations.

It is important to recall that the general elections of 2021 resulted in an environment of political and social polarization, as Pedro Castillo, a leader of a teachers’ union and of indigenous heritage, was elected president in a very narrow (only 44,263 votes of difference) second round win against the right-wing candidate Keiko Fujimori, who is the daughter of ex-president Alberto Fujimori.

Among some risks faced by the actual government are the further weakening of institutions, corruption scandals and lack of technical expertise, and remote risks, although lower than under Castillo’s presidency, include governmental intentions to impose greater state control over the economy and potential changes to Peru’s current constitution (which was enacted in 1993). For a new constitution to replace the current one through a constituent assembly, a constitutional reform proposal would need to be approved by Peru’s Congress, either through an absolute majority (87 votes) in two consecutive legislatures or simple a majority (66 votes) ratified in a referendum.

Social and political instability in Peru is not new. The country has experienced various instances of instability ranging from domestic terrorism (during the 1980s) to military coups and a succession of regimes. Although the risk of renewed domestic terrorism is not expected, any violence derived from the drug trade or illegal mining or a resumption of large-scale terrorist activities could hurt our operations. Additionally, some regimes during the 1970s and 1980s heavily intervened in the economy in pursuit of various economic policies and priorities, including expropriation, nationalization and new taxation policies. These interventions altered the country’s economic environment, financial system and agricultural sector, among other components.

There have also been several political disputes between the government and the opposition in recent decades. Since 2001, more than ten different political organizations have nominated candidates for President in each of the five election processes, showing low approval rating for all candidates (usually around 20%–30% approval ratings or less). Between August 2016 and February 2024, Peru has had 6 presidents, 3 congresses and 16 prime ministers.

Additionally, high levels of poverty and inequality in Peru have been a contributing factor to social conflict. Between 2004 and 2019 (pre pandemic) according to INEI, Peru’s poverty rate decreased from almost 60% of the population to 20%. In 2020, due to the economic shock resulting from the COVID-19 pandemic, the poverty rate increased to 30%, erasing nearly all gains from the last decade and even though it fell to 25.9% in 2021, it rose again in 2022 to 27.5%, remaining above pre pandemic levels. In 2023, the poverty rate increased for a second consecutive year due to weak economic conditions, according to the government technical organization National Center for Strategic Planning (or CEPLAN for its acronym).

There can be no assurance that Peru will not continue facing political, economic or social problems in the future or that these problems will not adversely affect our business, financial condition and results of operations. There is always the possibility that a political fraction could promote policies to respond to social unrest with a speech that includes or promotes, among other things, expropriation, nationalization, suspension of the enforcement of creditors’ rights and new taxation policies. As such, our financial condition and results of operations may also be adversely affected by changes in Peru’s political climate to the extent that such changes affect the nation’s economic policies, growth, stability, outlook or regulatory environment. Another source of risk is political and social unrest in areas where mining and oil and gas operations take place. In recent years, Peru has experienced protests against mining projects in several regions around the country.

Mining is an important part of the Peruvian economy. According to INEI, the mining and hydrocarbons sector represented 14.4% of GDP (mining 12.2% and hydrocarbons 2.2%) in 2023. The country’s exports are highly concentrated in the mining industry; in 2023, free on board (FOB) exports of metallic mining represented 65.9% of total exports (copper represents around half of mining exports), with tax revenues from the sector representing 7% of total fiscal revenues in 2023.

On several occasions, local communities have opposed these operations and accused them of polluting the environment, specifically rivers, hurting agricultural and other traditional economic activities, as well as complained of not receiving the benefits in terms of growth and wealth generated by the mining projects. For example, in 2021, politicized social unrest in Apurimac surrounded the Las Bambas mining project, which produced approximately 11% of Peru’s total copper production in 2022. Las Bambas’ majority owner, MMG, stated that if the routes to the mine continued to be blocked by different politicized members of communities surrounding the mine and routes to the mine, they would not be able to operate. In April 2022, Las Bambas shut down for 51 days, after protesters from two communities entered the mine and settled inside. The recent social protests of late 2022 and early 2023 have also affected Las Bambas’ operations as road blockages prevented the arrival of key inputs. In another example, on January 12, 2023, Minsur announced the temporary suspension of operations in its San Rafael tin mine, in Peru’s Puno region, as a measure of solidarity with the families of people who died in recent protests in the region. On February 6, 2023, Buenaventura temporarily suspended operations at its Julcani silver mine after protesters entered and destroyed part of the mine’s facilities.

These and other delays or cancellations of mining projects could reduce Peruvian economic growth and business confidence, thereby hurting the financial system both directly (many mining projects are at least partially financed by local financial institutions) and indirectly (overall economic activity could decelerate). Any such effect on the financial system could have a material adverse effect on our business and result of operations.

More recently, violence and crime have become the main concern of Peruvians, according to an October 2023 Ipsos survey, above corruption, unemployment and inflation. In Lima, the capital of Peru, one in three people over the age of 15 has been the victim of a crime in the last year, the highest point in almost seven years. The increase in citizen insecurity not only has a negative impact on victims of crime, but also on households and companies, which are forced to allocate part of their income to prevention measures. Due to the security crisis, the government in September 2023, declared two districts of Metropolitan Lima in a state of emergency to provide for security and social peace. This emergency state ended in January 2024, although the government could adopt this policy again in the future if they deemed it necessary.

Mining was also affected by crime. In December 2023, nine workers were killed and others gravely injured in an attack where men armed with explosives raided and took hostages at a mine belonging to Poderosa, one of Peru’s top gold producers. The government blamed illegal miners and criminal groups.

Altogether, this reduces efficiency in the economy and reduces aggregate productivity. The persistence of these problems represents a source of risk to the economy and, hence, our businesses.

After social unrest erupted in December 2022, Standard & Poor’s (S&P) changed the outlook for Peru’s long-term debt in foreign currency from stable to negative (though kept the credit rating at BBB) due to the challenging relationship between the executive and legislative branches, which limited the government’s ability to timely implement policies. S&P reaffirmed its BBB rating with negative outlook in February 2024. In January 2023, Moody’s changed Peru’s credit rating outlook from stable to negative (though kept the credit rating at Baa1) due to the intensification of social and political risks which threatened, over the next few years, a deterioration of institutional cohesion, governability, policy effectiveness and economic strength through successive governments. Months later, in October 2023, Fitch affirmed the sovereign rating (BBB) and outlook (negative), one year after changing the outlook to negative. The agency stated that the negative outlook reflected continued high level of political uncertainty in Peru and further deterioration of governance that have undermined private investment and are weighing on economic growth prospects.

Our banking and capital market operations in neighboring countries expose us to risk related to political and economic conditions in those countries.

ICBSA, Credicorp Capital Holding Colombia, Credicorp Capital Holding Chile and ASB Bank Corp. expose us to risks related to Bolivian, Colombian, Chilean and Panamanian political and economic conditions, respectively. These economies suffered unprecedented GDP contractions in 2020 due to the COVID-19 pandemic and have experienced an uneven recovery as a result of different policy responses and economic structures. The negative effect of the pandemic on poverty and inequality, combined with inflation rates (driven by high energy and food prices) not seen in these countries in decades, inflamed an already complex social environment characterized by elevated levels of inequality and dissatisfaction with authorities. According to data from the World Bank, Colombia is the second most unequal country in the region, as measured by the Gini index. In general, the higher the Gini index, which measures the rate of social inequality, of a country, the more unequal it is. Brazil has the highest Gini index in the region; Panama has the third highest.

In recent years, neighboring countries in Latin America in which we have banking and capital market operations have experienced widespread social unrest, and several left-wing leaders have been chosen as presidents. For example, in October 2019, Chile experienced massive and violent demonstrations that forced Sebastian Piñera’s government to sign off on a referendum on a new constitution. In late 2021, Gabriel Boric, a 36-year-old left-wing leader, was elected as Chile’s president for a four-year term. After voters rejected the text for a new constitution in September 2022, Chile’s congress approved a new constitutional process, which was again rejected in December 2023. The next presidential elections will take place in November 2025. In 2021, the proposal of an unpopular tax reform triggered its most serious public unrest in recent memory of Colombia. Gustavo Petro, also a left-wing candidate and former member of guerrilla group M-19, won the 2022 general election, making history as the first left-wing president to be elected in the country. He was also elected for a four-year term. His ability to carry out reforms was undermined by corruption scandals, as well as the loss of political majority in Congress. The next presidential elections will be held in May 2026. In 2022, rising living costs sparked large social protests in Panama. More than a year later, in October 2023, massive social protests erupted again after Congress fast-tracked the approval of the renegotiated concession contract between the government and Minera Cobre Panama. Social unrest lasted more than a month until the Supreme Court ruled the contract unconstitutional, a decision celebrated by the population. The next presidential election will be held in May 2024. In Bolivia, Luis Arce, from the left-wing, was elected president for a five-year term in 2020. Between late 2022 and January 2023, protests took place in Santa Cruz, which represents a larger proportion of Bolivia’s GDP than any other Bolivian city. In October 2023, the political party MAS (Movimiento al Socialismo) expelled Luis Arce from the party and prevented him from running in the 2025 national elections.

This political environment has had a general negative effect on economic activity and businesses in countries in which we have operations. Given these developments, we cannot provide any assurance that Peru will not experience any residual effects from events in neighboring countries, such as the possibility of the base of protesters in Peru extending to the middle class, which may have a materially adverse effect on our business and result of operations. Significant changes to Bolivian, Colombian, Chilean and Panamanian political and economic conditions could have an adverse effect on our business, financial condition, and results of operations.

Bolivia

In 2023 most of the economic activity indicators surpassed their pre-pandemic levels. However, some specific events affected the trend of GDP growth observed since 2021, accelerating the slowdown of the economic activity in the country. Initial estimates suggest that GDP growth for 2023 was around 2%. Furthermore, the decline in the prices of key commodities and the reduction in Bolivia’s primary sector’s productive capacity, especially the gas sector, affected the level of exports to the extent that it is estimated that the trade balance will reflect a deficit for 2023, equivalent to 0.5% of GDP.

Bolivia has a fixed exchange rate regime with an official rate of USDBOB 6.96. Since February 2023, the demand for dollars increased which caused the Central Bank to take different measures including the direct sale of dollars to the public by the Central Bank and the reduction of cash reserve requirements of USD-denominated deposits. In addition, to increase the availability of dollars, the monetary authority exchanged around 90% of its holdings of Special Drawing Rights (SDR) with the International Monetary Fund, equivalent to US$400 million, and, with the enactment of Law 1503, which enabled the Central Bank to sell up to 50% of gold reserves, it monetized approximately 17 tons of the gold reserves, resulting in an additional influx of US$1.05 billion. The government also negotiated new external loans with multilateral and bilateral entities, for an aggregate amount of approximately US$1.5 billion. Despite the policies enacted by the Central Bank, banks still needed to establish different types of limits for cash withdrawals in USD and to increase the fees charged for foreign transfers from 2% in February to around 11% in December. Locally, an informal parallel market has surfaced for the sale and purchase of dollars, with the exchange rate oscillating between 8.0 to 8.5 bolivianos per dollar (above to the official price 6.96 BOB/US$). Finally, International Reserves (INR’s) as of December 31st, 2023, were US$1.7 billion, 55% less than as of the end of 2022. In November 2023, S&P cut Bolivia’s sovereign rating from B- to CCC+ with a negative outlook. Fitch followed suit and, in February 2024, lowered the rating by two notches to CCC.

In April 2023, the ASFI intervened Banco Fassil, the third largest bank in Bolivia, due to severe liquidity issues and serious indications of management deficiencies.

For 2024, the government projects GDP to grow at a rate of 3.7%, driven by internal consumption and economic policies that promote macroeconomic stability, and has ruled out a devaluation of the official exchange rate. It should be noted that in April 2024 the World Bank estimated GDP growth in 2024 to stand at 1.4%. In addition, it projects that dollar liquidity will stabilize in 2024 due to higher cash flows from public industries, new external credits and the reduction of imports. Finally, the government expects a fiscal deficit in 2024 of 7.8% of GDP and a stable level of inflation (3.6% by the end of the year). However, the continued possibility of political conflicts and social unrest remains a risk factor that may affect the economic outlook for 2024.

Additionally, the lending quotas and caps on interest rates that were established in the Bolivian Financial Services Law (Ley de Servicios Financieros, No. 393), which was enacted in 2013, and the mandatory deferrals and refinancings schemes instituted in 2020 and 2021 to mitigate the impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic, continued to negatively impact interest margins on banks.

Colombia

According to the Colombian National Statistics Bureau (DANE), the Colombian economy exhibited a GDP growth of just 0.6% in 2023, the lowest (excluding the pandemic) recorded in 25 years. Amidst a generalized downside revision of the previously presented 2023 GDP data, the Colombian economy narrowly avoided a technical recession. On the spending side, the domestic demand declined 3.8% last year, driven by a plummet in investment (-25%) due to elevated inflation, restrictive financial conditions and persistent regulatory uncertainty.

In this context of domestic demand contraction, challenges remain. First, inflation has remained elevated (7.7% year-over-year as of February 2024), reducing consumers’ real income, while the higher corporate taxes resulting from the 2021 and 2022 tax bills and higher political uncertainty cause both private consumption and investment to remain sluggish. In addition, we believe it is not a coincidence that the worst instance of domestic demand since 1999 has occurred amid the highest policy rate since that year. In fact, the ex-ante real rate is currently the highest since data has been available (October 2003). Hence, a significant reduction in interest rates seems to be a necessary condition for an economic recovery, but uncertainty on the monetary policy front remains high amid upside risks to inflation from the El Niño phenomenon and the need to increase fuel prices. Undoubtedly, fiscal accounts remain a factor of never-ending concern; while they were better than expected in 2023, the government is targeting a sharp increase in primary spending of 1.8% of GDP in 2024, and the fiscal income projection heavily relies upon uncertain income sources (namely, legal tax dispute and tax management efficiencies-related revenues for a combined 1.7% of GDP). Accordingly, the Autonomous Committee of the Fiscal Rule has warned that the fiscal rule —the mechanism that establishes a permanent constraint on fiscal policy through a limit on the structural deficit relative to GDP— could be breached in 2024 should spending cuts are not undertaken. That said, the Minister of Finance, Ricardo Bonilla, has reaffirmed the government’s commitment to fiscal rule, suggesting spending cuts if necessary. Finally, we consider that political noise has decreased during the last year as no major government reforms have yet been approved, while the outcome of the October 2023 regional election meant a move of the political pendulum to the center/center-right. However, regulatory uncertainty is set to remain high in 2024 amid the discussion of controversial reforms (i.e., pensions, labor, healthcare) and proposals to change the regulatory schemes of important sectors like energy.

In June 2023 Moody’s affirmed the Government of Colombia’s long-term local and foreign currency issuer rating at Baa2 and noted the that “the stable outlook incorporates Moody’s expectations that institutional arrangements will continue to play a stabilizing role, assuring that policy directives remain within the confines defined by the existing policy settings, particularly on the fiscal front.” Moreover, in December 2023 Fitch affirmed Colombia’s long-term foreign currency issuer rating at BB+ with stable outlook. Fitch noted that “the ratings are constrained by continued fiscal challenges that weigh on prospects for consolidation needed to ensure stable debt/GDP, a particularly high interest burden, high commodity dependence, and structurally large current account deficit.” Lastly, on January 2024, S&P affirmed the foreign currency issuer rating at BB+ but revised the outlook from stable to negative amid subdued economic growth.

Chile

According to the Central Bank of Chile (BCCh), the Chilean economy barely grew 0.2% year-over-year in 2023. The authority has stated that the economy has behaved according to expectations, but with heterogeneous performance among economic sectors. On the demand side, household consumption has recently been showing an incipient recovery, while investment, beyond recent ups and downs, has continued to be sluggish amid weak construction linked to the housing and real estate segment.

According to the Chilean National Statistics Bureau (INE), inflation stood at 3.9% in December 2023. The figure showed a substantial decline compared to a year ago when it stood at 12.8%. As a result, price adjustments have continued to recede amid the resolution of macroeconomic imbalances, including the closing of the output gap, the normalization of aggregate demand after an unsustainable trend between 2021 and 2022 and the fading of cost-related shocks observed in the past few years.

The BCCh has continued with the normalization process of the policy rate, which has accumulated a reduction of 400 basis points between July 2023 and February 2024. Going forward, and according to the most recent monetary policy report, the reference rate is expected to stand between 4% and 6% by year-end, well below the peak of 11.25% seen in the first half of 2023. The reduction in domestic imbalances, the lower inflation and the ongoing monetary policy easing cycle should allow GDP to grow around 2.5% in 2024.

Regarding the fiscal accounts, the latest Public Finances Report showed that in 2023, the fiscal deficit would stand at 2.4% of GDP, while gross debt is forecasted at 39.8% of GDP. In our view, the sustainability of the public finances in the mid-term is one of the most relevant risk factors to consider. Recently, S&P revised Chile’s outlook from stable to negative on weaker political consensus. According to the credit agency, political wrangling has slowed the approval of meaningful policies to boost economic growth and rebuild fiscal resilience. The firm said fiscal accounts are expected to consolidate, but the fiscal profile is vulnerable to shocks, given still moderately low buffers. The negative outlook captures weakening political consensus on critical parameters of Chile’s political and economic agenda, which will weigh on Chile’s capacity to grow and potentially undermine its credit quality over time. Finally, we consider that political noise and uncertainty have significantly decreased after the rejection of the second constitutional plebiscite in December 2023 and the high probability of no new constitutional processes during the remainder of the current administration. In any case, the developments around the pension and tax reforms discussion are factors worth monitoring.

Panama

In 2023, economic activity unexpectedly increased with annual GDP growth of 7.3%. Large infrastructure and investment projects, such as the Panama’s third metro line, a fourth bridge over the canal and the Gatún power plant, boosted growth. On a sector-by-sector basis, construction, commerce, transport, and mining contributed the most to Panama’s economic growth. Additionally, Panama was negatively affected by the weather phenomenon “El Niño”, which caused the worst drought in 70 years and disrupted activities in the Panama Canal. The number of ships that transit the canal decreased 7.4% in 2023 compared to the same period last year, although the authority managed to increase toll revenues by 10%.

Panama’s GDP growth after the 2020 pandemic shock, which caused an unprecedented contraction of 17.7%, has been among the highest in the world. In 2021 and 2022, GDP rebounded 15.8% and 10.8%, respectively. The global economic recovery, big infrastructure projects and copper production from Minera Cobre Panama drove this substantial post-COVID economic recovery.

However, negative events in 2023 are expected to affect the outlook for the coming years. In October, the Congress fast-tracked the approval of the renegotiated concession contract between the government and Minera Panama, a local subsidiary of the Canadian company First Quantum Minerals. This approval caused massive protests – the worst in at least three decades - and road blockages that resulted in shortages of basic goods as large portions of the country were shutdown. The population claimed that the contract was unconstitutional, abusive and harmful to the environment.

It is worth noting that in mid-2022 Panama also experienced massive social unrest, similar to the 2023 episode, sparked by rising living costs (especially higher gasoline prices). The Panamanians claimed, at the time, that high inequality and a greater public perception of corruption in the political arena were the reasons behind their complaints.

On November 3, 2023, to diminish social unrest, President Laurentino Cortizo signed into law an indefinite moratorium on new mining concessions and the prohibition of renewing existing concessions. Despite that decision, protests continued. Days later, on November 28, 2023, Panama’s Supreme Court ruled the contract unconstitutional, to which the population reacted positively. Accordingly, the government ordered a definitive closure of First Quantum’s copper mine. According to the Minister of Industry and Commerce, the orderly process of the closure of a mine of this magnitude could take between seven to eight years.

The importance of the mine to the country was undeniable. Cobre Panamá was the largest private investment project in the country’s history with an amount equivalent to 10% of GDP. It began operations in 2019 and reached maximum capacity in 2021. With a production of 350 thousand tons of copper in 2022 it was among the top 15 copper producing mines in the world. Additionally, according to the National Institute of Statistics and Census (INEC for its acronym), it generated around US$2.8 billion (3.7% of GDP) through copper exports and was an important source of fiscal revenues.

In an already challenging fiscal environment, the closure of the Cobre Panama mine and the moratorium of new mining concessions triggered movements from the main three credit rating agencies in the last quarter of 2023. In September, before these events, Fitch affirmed the BBB- rating but changed the outlook from stable to negative due to persistent fiscal pressures and uncertain prospects for consolidation. The agency added that the government’s expected royalties from the renegotiated concession mining contract appeared increasingly doubtful. In October, Moody’s followed suit and reduced its rating to Baa3 (and changed the outlook to stable). The downgrade reflected the agency’s view about Panama’s lack of effective policy response to structural fiscal challenges that have been rising over time. Moody’s also considered that in a social-political context characterized by heightened tensions Panama’s credit profile will continue to be undermined by persistent pressures. And, in November, S&P revised the outlook to negative (and affirmed the BBB rating) to reflect the risk of a downgrade resulting from the potential fallout of the recent events on investor confidence, private investment and economic growth prospects.

Finally, in March 2024, Fitch downgraded Panama’s credit rating by one notch to BB+ with stable outlook, stripping the country from its investment grade status achieved in 2010. The agency stated that the move reflects fiscal and governance challenges that have been aggravated by the events surrounding closure of Minera Cobre Panama. As such, Moody’s places Panama’s credit rating at the lowest possible rating for a security to be considered investment grade while S&P’s rating is one notch above investment grade.

Panama’s public debt, as a percentage of GDP, peaked at year-end 2020 at 65.0% of GDP, fell to 60.1% at year-end 2021, to 57.9% of GDP at year-end 2022 and reached 55.2% of GDP at the end of 2023. Although public debt has fallen since 2020, the 2023 level still represents an increase of 10 percentage points from the year-end since 2019 rate of 44.5% of GDP.

On the positive side, in October, Panama was removed from the (Financial Action Task Force) grey list, a movement considered key by the International Monetary Fund to preserve Panama’s position as a regional financial center. However, the country is still on the European Union list of non-cooperative jurisdictions for tax purposes.

Finally, the May 2024 presidential elections will add an additional source of uncertainty to the country.

Economic and market conditions in other countries may affect the Peruvian economy and the market price of Peruvian securities.

Peru is a small, open economy highly integrated with the rest of the world and is affected by movements in the external environment (growth of main trade partners, changes in commodity prices and movements in external rates and global financial markets). As such, any major deterioration of the international economy can have materially adverse effects on the Peruvian economy and markets, as well as in our businesses and operational results. According to the Economist Intelligence Unit (EIU), there is a moderate risk that global inflation will re-accelerate in 2024, driven by firm global demand and an upswing in key commodity prices due to supply shortages. That could push central banks to keep tightening well into the year, raising interest rates to levels that would be likely to lead to a much more significant slump in consumer and investment demand.

In 2023, the United States and several large, advanced economies showed a greater than expected resilience and avoided falling into one of the most anticipated recessions by markets. A strong labor market kept consumption spending robust and caused Central Banks to continue raising their monetary policy rates, especially during the first half of the year. In China, although GDP surpassed the government’s target with a 5.2% economic growth, the year was characterized by a confidence and property market crisis which demanded fiscal support.