- UAL Dashboard

- Financials

- Filings

-

Holdings

- Transcripts

- ETFs

- Insider

- Institutional

- Shorts

-

8-K Filing

United Airlines (UAL) 8-KOther Events

Filed: 15 Dec 04, 12:00am

Exhibit 99.1

IN THE UNITED STATES BANKRUPTCY COURT

FOR THE NORTHERN DISTRICT OF ILLINOIS

EASTERN DIVISION

In re: | ) | Chapter 11 |

| ) |

|

UAL CORPORATION, et al., | ) | Case No. 02-B-48191 |

| ) | (Jointly Administered) |

Debtors. | ) |

|

| ) | Honorable Eugene R. Wedoff |

MEMORANDUM IN SUPPORT OF THE DEBTORS’ MOTION

TO REJECT THEIR COLLECTIVE BARGAINING AGREEMENTS

PURSUANT TO 11 U.S.C. § 1113(c)

| James H.M. Sprayregen, P.C. | ||

| Alexander Dimitrief, P.C. | ||

| KIRKLAND & ELLIS LLP | ||

| 200 East Randolph Drive | ||

| Chicago, Illinois 60601 | ||

| Telephone: | (312) 861-2000 | |

| Facsimile: | (312) 861-2200 | |

| Counsel for the Debtors | ||

| and Debtors-in-Possession | ||

|

|

| |

|

|

| |

|

|

| |

Dated: December 14, 2004 |

|

| |

TABLE OF CONTENTS

i

|

| |||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| ||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| |||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| ||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| ||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| ||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| |||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| |||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| |||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| |||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| ||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| ||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| |||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| |||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| |||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| |||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| ||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| United’s Defined Contribution and Nonqualified Pension Plans |

| |||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| ||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| United Responsibly Managed Its Pension Plans in the Years Before the Company Filed for Bankruptcy |

| ||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| ||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| ||||

ii

iii

iv

v

vi

|

| The Railway Labor Act and Bankruptcy Code Would Not Allow Employees to Strike |

| |||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| ||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Creditors’ Claims Will Be Severely Impaired If the CBAs Are Not Modified |

| |||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| ||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| ||||||

vii

Cases |

|

|

|

ALPA v. UAL, |

|

897 F.2d 1394 (7th Cir. 1990) |

|

|

|

Buffalo Forge Co. v. United Steelworkers of Am., |

|

428 U.S. 397 (1976) |

|

|

|

Detroit & Toledo Shore Line R.R. v. United Transp. Union, |

|

396 U.S. 142 (1969) |

|

|

|

Heinz v. Central Laborers’ Pension Fund, |

|

303 F.3d 802 (7th Cir. 2002) |

|

|

|

In re Allied Delivery System Co., |

|

49 B.R. 700 (Bankr. Ohio 1985) |

|

|

|

In re American Provision Co., |

|

44 B.R. 907 (Bankr. D. Minn. 1984) |

|

|

|

In re Amherst Sparkle Market, |

|

75 B.R. 847 (Bankr. N.D. Ohio 1987) |

|

|

|

In re Appletree Mkts., Inc., |

|

155 B.R. 431 (S.D. Tex. 1993) |

|

|

|

In re Bayly Corp., |

|

163 F.3d 1205 (10th Cir. 1998) |

|

|

|

In re Bayly Corp., |

|

No. Civ.A. 95 N 901, 90-18983 SBB, 1997 WL 33484011 (D. Colo. Feb 2, 1997) |

|

|

|

In re Big Sky Transp. Co., |

|

104 B.R. 333 (Bankr. D. Mont. 1989) |

|

|

|

In re Blue Diamond Coal Co., |

|

147 B.R. 720 (Bankr. E.D. Tenn. 1992), aff’d, 160 B.R. 574 (E.D. Tenn. 1993) |

|

|

|

In re Bowen Enters., Inc., |

|

196 B.R. 734 (Bankr. W.D. Pa. 1996) |

|

|

|

In re Century Brass Prods., Inc., |

|

55 B.R. 712 (D. Conn. 1985), rev’d on other grounds, 795 F.2d 265 (2d Cir. 1986) |

|

|

|

In re CF&I Fabricators of Utah, Inc., |

|

150 F.3d 1293 (10th Cir. 1998) |

|

viii

In re Continental Airlines Corp., |

|

901 F.2d 1259 (5th Cir. 1990), cert. denied, 506 U.S. 828 (1992) |

|

|

|

In re Garofalo’s Finer Foods, Inc., |

|

117 B.R. 363 (Bankr. N.D. Ill. 1990) |

|

|

|

In re Indiana Grocery Co., |

|

138 B.R. 40 (Bankr. S.D. Ind. 1990) |

|

|

|

In re Kentucky Truck Sales, Inc., |

|

52 B.R. 797 (Bankr. W.D. Ky. 1985) |

|

|

|

In re Maxwell Newspapers, Inc., |

|

981 F.2d 85 (2d Cir. 1992) |

|

|

|

In re Mile Hi Metal Sys., Inc., |

|

899 F.2d 887 (10th Cir. 1990) |

|

|

|

In re Moline Corp., |

|

144 B.R. 75 (Bankr. N.D. Ill. 1992) |

|

|

|

In re National Forge Co., |

|

279 B.R. 493 (Bankr. W.D. Pa. 2002) |

|

|

|

In re Ormet Corp., |

|

316 B.R. 665 (Bankr. S.D. Ohio 2004) |

|

|

|

In re Royal Composing Room, Inc., |

|

848 F.2d 345 (2d Cir. 1988) |

|

|

|

In re Salt Creek Freightways, |

|

47 B.R. 835 (Bankr. D. Wy. 1985) |

|

|

|

In re Sun Glo Coal Co., Inc., |

|

144 B.R. 58 (Bankr. E.D. Ky. 1992) |

|

|

|

In re Sunarhauserman Inc., |

|

126 F.3d 811 (6th Cir. 1997) |

|

|

|

In re Texas Sheet Metals, Inc., |

|

90 B.R. 260 (Bankr. S.D. Tex. 1988) |

|

|

|

In re United States Truck Co., |

|

89 B.R. 618 (E.D. Mich. 1988) |

|

|

|

In re US Airways Group, Inc., |

|

296 B.R. 734 (Bankr. E.D. Va. 2003) |

|

ix

In re Walway Co., |

|

69 B.R. 967 (Bankr. E.D. Mich. 1987) |

|

|

|

Matter of GCI, Inc., |

|

131 B.R. 685 (Bankr. N.D. Ind. 1991) |

|

|

|

NLRB v. Bildisco & Bildisco, |

|

465 U.S. 513 (1984) |

|

|

|

PBGC v. LTV Corp., |

|

496 U.S. 633 (1990) |

|

|

|

PBGC v. Republic Techs. Int’l, LLC, |

|

287 F. Supp. 2d 815 (N.D. Ohio 2003) |

|

|

|

Pineiro v. PBGC, |

|

318 F. Supp. 2d 67 (S.D.N.Y. 2003) |

|

|

|

Texas & New Orleans R.R. v. Brotherhood of Ry. & S.S. Clerks, |

|

281 U.S. 548 (1930) |

|

|

|

Truck Drivers Local 807, Int’l Bhd. of Teamsters v. Carey Transp., Inc., |

|

816 F.2d 82 (2d Cir. 1987) |

|

|

|

UAW v. Gatke Corp., |

|

151 B.R 211 (N.D. Ind. 1991) |

|

|

|

United Steelworkers of Am., AFL-CIO v. United Eng’g, Inc., |

|

52 F.3d 1386 (6th Cir. 1995) |

|

|

|

Wheeling-Pittsburgh Steel Corp. v. United Steelworkers of Am., |

|

791 F.2d 1074 (3d Cir. 1986) |

|

|

|

Statutes |

|

|

|

11 U.S.C. § 1113 |

|

|

|

26 U.S.C. § 404 |

|

|

|

26 U.S.C. § 411 |

|

|

|

26 U.S.C. § 412 |

|

|

|

26 U.S.C. § 4972 |

|

|

|

29 U.S.C. § 1001 |

|

|

|

29 U.S.C. § 1054 |

|

x

29 U.S.C. § 1082 |

|

|

|

29 U.S.C. § 1302 |

|

|

|

29 U.S.C. § 1322 |

|

|

|

29 U.S.C. § 1341 |

|

|

|

29 U.S.C. § 1342(d) |

|

|

|

29 U.S.C. § 1347 |

|

|

|

29 U.S.C. § 1348 |

|

|

|

Regulations |

|

|

|

26 C.F.R. § 1.401 |

|

|

|

26 C.F.R. § 1.402 |

|

|

|

26 C.F.R. § 1.412 |

|

|

|

29 C.F.R. § 4022 |

|

|

|

29 C.F.R. Pt. 4011 |

|

xi

xii

xiii

xiv

This is an unwelcome motion that United tried its best not to have to file. Two years ago, the Company and its unions reached agreements that made significant progress in reducing United’s then industry-leading labor costs to more competitive levels. United devoted the next 14 months of these proceedings to constructing a business plan to secure Air Transportation Stabilization Board (“ATSB”) loan guarantees on terms that would have allowed the Company to exit bankruptcy with its revised collective bargaining agreements (“CBAs”) and pension plans intact, to the benefit of United’s employees, retirees and the Pension Benefit Guaranty Corporation (“PBGC”). As a result, United has become a markedly different and stronger enterprise than it was in April 2003, with a stronger network and more profitable route structure, a streamlined and more cost-competitive fleet, more (and bigger) regional jets, and “Ted,” a vibrant low-fare offering.

But United’s world has changed even more, and in ways more permanent and profound than anyone had envisioned as recently as a year ago, let alone when these proceedings began in December 2002. The ATSB’s final denial of United’s application, the resulting need to secure exit financing that is not backed by ATSB loan guarantees, the extraordinary increase in fuel prices in the months since United finalized its ATSB application and the persistent downward pressure on pricing and yields have coalesced to force United to revisit its cost of labor, which remains the Company’s single largest expense (and one that, unlike fuel, United and its employees have within their power to address).

Moreover, United must reduce its labor costs expeditiously. To be sure, other legacy carriers have warned that their CBAs are no longer affordable because of the persistently low yields and steep fuel costs confronting the industry. And with ATA in bankruptcy, even low cost carriers have been unable to avoid the consequences of the worst economic environment in

1

industry history. But what differentiates most of these competitors from United is that they have sufficient liquidity to allow them the time to lower their cost structures gradually. United does not have this luxury. Under current projections, the Company’s cash balance will sink to precarious levels during the historically lean winter months, putting the entire operation at risk. Furthermore, unremitting industry economics have put United in jeopardy of breaching the terms of its DIP financing facility, which would put United’s future at risk.

Beyond overcoming these immediate hurdles, additional and fundamental reductions in the cost of labor are necessary to achieve the same goal underlying United’s first Section 1113 motion – to emerge from bankruptcy successfully and permanently. In particular, because of how profoundly United’s world has changed since April 2003, United must come to grips with its daunting pension liabilities. The Company fully appreciates that the men and women of United have been counting on receiving all of the retirement benefits that they have earned through years of hard work. But even before the ATSB rejected United’s loan guarantee application in June 2004, critics were already faulting the Company for not having terminated its pension plans to address the “substantial concerns about the under funded status of United’s pension plan[s]” and “United’s ability to generate sufficient cash flows to meet its pension funding obligations” that were explicitly cited by the ATSB as one of several principal grounds for denying loan guarantees back in December 2002.(1) At this juncture, United must squarely address its pension plan liabilities to attract exit financing in the face of a relentlessly punishing price environment, low cost competition and pervasively high fuel prices.

Yet, contrary to the fears harbored by many of United’s employees and retirees about the prospect of plan terminations, a dispassionate assessment of the facts clarifies that all

(1) Rejection Letter from ATSB to United of Dec. 4, 2002 (Ex. 117).

2

vested participants would continue to receive guaranteed benefit payments. In particular,(2) most current retirees would not see dramatic reductions in their monthly payments, and many retirees would not experience any reductions at all:(3)

Exhibit 1. BENEFITS RETAINED BY CURRENT RETIREES.

Retiree Group |

| Percentage of |

| Percentage of |

| |

Pilots |

| 81 |

|

| 44 |

|

Flight Attendants |

| 100 |

|

| 99 |

|

Mechanics |

| 96 |

|

| 62 |

|

Ramp |

| 94 |

|

| 65 |

|

PCEs |

| 98 |

|

| 47 |

|

SAM |

| 99 |

|

| 83 |

|

Although the impact on active employees would be more pronounced, most employees (except pilots, who must stop flying at age 60) could substantially mitigate the impact of a termination by working until age 65, the traditional retirement age in most pension plans:(4)

(2) The details and group-by-group assumptions underlying the analyses resulting in the percentages set forth in Exhibits 1-2 may be found in Section VI.C.2 of this Memorandum. Exhibit 2 projects the expected benefit at the present average retirement age following termination and replacement versus the expected benefit if an employee continues working until age 65.

(3) Declaration of Timothy J. Marnell (“Marnell Decl.”) (Ex. 107) ¶ 96.

(4) Marnell Decl. ¶ 97.

3

Exhibit 2. RETIREMENT BENEFITS FOR ACTIVE EMPLOYEES.

Employee Group |

| Percentage of |

| Percentage of |

| |

Pilots |

| 67 |

| N/A |

|

|

Flight Attendants |

| 56 |

| 99 |

|

|

Mechanics |

| 56 |

| 68 |

|

|

Ramp |

| 46 |

| 59 |

|

|

PCEs |

| 46 |

| 78 |

|

|

SAM |

| 44 |

| 70 |

|

|

Regrettably, resolving the Company’s pension issues will not suffice. United requires approximately $725 million in additional labor savings on average per year to satisfy the financial metrics necessary for exit financing. United will continue to work with its unions to try to make the process of reducing its labor costs a consensual one. But whether by agreement or through a ruling on this motion, the need for United’s proposed changes to its CBAs is irrefutable. So too is the reward – the preservation of a revitalized enterprise that will be able to compete successfully and profitably (and, in the process, offer stable jobs with competitive pay) in a fundamentally changed industry.

* * *

Part II of this Memorandum describes the economic pressures afflicting all network carriers. Part III describes the impact on United and how the Company is not alone in revisiting its cost of labor. Part IV provides an overview of United’s pension plans, the Byzantine funding rules under ERISA and how United’s unfunded pension liabilities grew to more than $6 billion. Part V outlines United’s proposals to its unions, which are detailed in the

4

accompanying appendices. Part VI details how United has satisfied all the requirements under Section 1113 for rejecting its CBAs.

Airline losses since 2001 have been staggering. Legacy carriers lost $24.3 billion from 2001 to 2003 and are expected to lose another $3 billion in 2004.(5) Worse, these losses have persisted despite a 14.5 percent reduction in operating expenses attributable to a painful combination of downsizing and cost-cutting.(6) While industry observers anticipated serious financial difficulties following September 11, no one foresaw that revenues would remain at such low levels for so long. Predictions that airlines would return to profitability have proved unfounded time and again, leaving legacy carriers in particular to face an uncertain future in 2005 and beyond.

The basic reasons behind the diminished revenues and unrelenting losses are not new – indeed, United flagged them in its first Informational Brief.(7) But the sea change in industry fundamentals has intensified and cut deeper and deeper into profits. Lower revenues have made it imperative for airlines to become more capable of absorbing large shocks, such as higher fuel costs.

(5) United States Government Accounting Office, Legacy Airlines Must Further Reduce Costs to Restore Profitability (Ex. 120) at 34-35 (Aug. 2004).

(6) GAO, Legacy Airlines at 19.

(7) Informational Brief of United Air Lines, Inc. at 36-45 [Docket No. 145].

5

Traditionally, the airline industry has gone through “boom and bust” cycles which have tracked broader macroeconomic trends, with periodic flush years followed by losses.(8) This historical pattern offered airlines the hope of profits during boom periods so long as they could survive the downturns. Now, structural changes in the industry likely have put an end to the boom times, forcing airlines to adapt their operations to permanently shrunken revenues.(9) As a federal government report recently concluded, the “potential for airlines to earn large profits during up-cycles to cover losses during down-cycles, as they did during the 1990s, appears to have come undone this decade.”(10)

Specifically, even though the broader economy recovered in 2003 and 2004, revenues for legacy carriers have remained low. From 1998 to 2003, real US GDP increased 14.5 percent, but airline revenues moved the opposite way, falling 10.7 percent.(11) Indeed, the airlines’ share of the US GDP remains appreciably below pre-September 11 levels:

(8) E.g., GAO, Legacy Airlines at 4-5.

(9) Declaration and Expert Report of Daniel M. Kasper (“Kasper Decl.”) (Ex. 101) ¶¶ 20-25.

(10) GAO, Legacy Airlines at 48.

(11) Kasper Decl. ¶ 24.

6

Exhibit 3. U.S. AIRLINE REVENUES AS A PERCENTAGE OF U.S. GDP.

Empty seats are no longer the culprit. Airlines are “on pace to carry a record 685 million passengers in 2004, a 3 percent increase from 2000, the busiest year on record.”(12) Many airlines – including United – are operating with the highest “load factors” (the percentage of seats occupied by customers) in their histories.(13) But even though passenger levels and loads are at an all-time high, inflation-adjusted airline revenues have reverted to 1994 levels. The reason is that yields, as measured by revenue per passenger, are down approximately 20 percent since 2000:

(12) Air Transport Association, U.S. Airlines Expecting Record Thanksgiving Traffic (Nov. 17, 2004).

(13) Kasper Decl. ¶ 23.

7

Exhibit 4. AIRLINE INDUSTRY YIELDS.

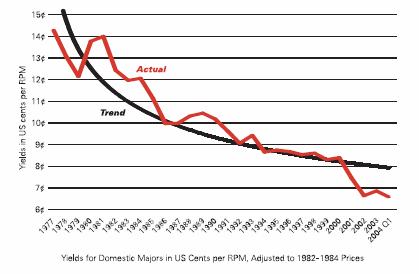

This drop in yields is not “business as usual.” Although yields have fallen gradually for decades in real terms (that is, when adjusted for inflation), the steep decline over the last four years has been far more severe than historical norms:(14)

(14) Unisys R2A Transportation Management Consultants, Unisys R2A Scorecard (Ex. 121) at 9 (Sept. 2004).

8

Exhibit 5. DECREASES IN DOMESTIC AIRFARES IN CONSTANT DOLLARS.

In 2004, while yields through the early part of the year were roughly the same as already-depressed 2003 levels, they fell sharply in late summer through the fall:(15)

Exhibit 6. CHANGE IN DOMESTIC YIELDS, 2004 VS 2003.

(15) Kasper Decl. ¶ 22.

9

These trends suggest the next “boom” may never come and, even if it does, yields and revenues are unlikely to return to prior levels.(16) LCCs continue to expand, entering new markets and increasing capacity, the Internet presents a permanent drag on fares through their price transparency, and there are few signs that business travelers will revert to their premium-paying ways of the late 1990’s. As a consequence, the industry is unlikely to benefit from increasing prices in the foreseeable future. Indeed, targeted attempts to pass through increased fuel costs have largely failed. When a carrier has tried to raise prices, others have refused to follow suit. And with scores of aircraft parked in the desert since September 11 available at the next revenue uptick, the economics of the industry will continue to work against increased prices for the foreseeable future.(17)

With all carriers striving to improve revenues, competition for passengers has intensified. Measured by the number of roughly-equal sized competitors on each route, carriers face significantly more domestic competition than in 1998.(18) This increase is attributable to the continued emergence of LCCs,(19) whose share of domestic passengers is now over 30 percent:

(16) Kasper Decl. ¶¶ 43-51.

(17) Garrett Chase, Lehman Brothers Equity Research, Dinosaurs in the Desert (Aug. 13, 2004) (“We believe that domestic weakness in the airline sector will continue for the foreseeable future.”).

(18) GAO, Legacy Airlines at 40-47.

(19) LCCs include Southwest, Access Air, AirTran, ATA, Eastwind, Frontier, Kiwi, National, Pro Air, Reno, Spirit, Sun Country, Vanguard, Western Pacific, Air South, Morris Air, JetBlue, ValuJet and America West.

10

Exhibit 7. LCC SHARE OF DOMESTIC PASSENGERS.

In total, United now competes with LCCs on over 80 percent of its domestic routes, double the percentage from a decade ago.(20) In particular, United is now coping with LCCs on an increasing number of high-revenue routes:

(20) Kasper Decl. ¶¶ 27-36.

11

Exhibit 8. NUMBER OF UNITED’S TOP 50 MARKETS WITH NON-STOP LCC COMPETITION.

LCC expansion has driven down yields throughout the industry.(21) Nearly all consumers now have access to LCC service, and those low cost carriers largely determine prices in the market. Periodic attempts by network carriers to raise fares have been matched by opportunistically lower prices by LCCs. Because of vastly different cost structures, low ticket prices that generate a profit for an LCC often result in a loss for a legacy carrier. Although a short-term boon for bargain-hunting airline passengers, the industry environment has left airlines struggling to align their cost structures with record-low pricing levels. And although some legacy carriers like United have reduced their costs significantly, a large gap remains between the cost structures of legacy carriers and those of LCCs:

(21) Kasper Decl. ¶¶ 26, 44.

12

Exhibit 9. UNADJUSTED CASM FOR LEGACY AIRLINES AND LCCS.

The competitive pressure from LCCs is here to stay.(22) LCC capacity continues to grow – JetBlue has ordered 223 new aircraft (which would quadruple the size of its current fleet) and has options for 150 more, while Southwest has 134 more aircraft on order with options for another 263. Independence Air, a new LCC that was once a United Express carrier, is now flying out of Washington, DC, one of United’s hub cities. And Virgin America, another LCC, plans to base its operations and flights from San Francisco, another United hub. As a recent government report observed, “[u]nlike earlier low cost airlines, many of which quickly disappeared, these airlines are well-capitalized and offer a good overall product.”(23)

More customers are turning to Internet search tools to find the lowest fares. The transparency of the Internet has had a greater impact than previously expected:

(22) Kasper Decl. ¶¶ 19, 43-46.

(23) GAO, Legacy Airlines at 8.

13

Exhibit 10. PERCENTAGE OF AIRLINE REVENUE BOOKED ONLINE.

Internet search engines that scour for the lowest price have placed a greater emphasis on the cost of the ticket to the exclusion of expansive schedules, connectivity and other amenities in which legacy carriers have excelled. With price-focused Internet searches readily available, carriers have generally been forced to match the prices of the cheapest competitor on each route. Any increase in fares causes a near-instant loss in market share as cost-conscious customers use the Internet to hone in on the lowest price.(24)

One of the clearest signs of the paradigmatic shift in the airline industry is the loss of higher fare tickets once routinely purchased by business passengers.(25) Most analysts anticipated that the recovery of the broader economy would bring the return of business travelers who would be willing to pay for the convenience and flexibility of unrestricted, full-fare tickets.

(24) Kasper Decl. ¶¶ 37-38.

(25) Kasper Decl. ¶¶ 39-42.

14

This has not happened. United’s proportion of domestic revenue from high-yield fares has continued to fall:

Exhibit 11. UNITED’S PROPORTION OF DOMESTIC REVENUE FROM PREMIUM PASSENGERS.

These trends persist even though business travel has increased as the economy has rebounded. Instead of purchasing full-fare tickets on network carriers, however, more business travelers are purchasing restricted fares or flying on LCCs. Moreover, technological substitutes for flying have become increasingly popular among business travelers. For example, a 2003 survey by Accenture found that 27 percent of business travelers had conducted teleconferences and videoconferences as an alternative to travel.(26) Without any sign that this trend will reverse itself, airlines (and particularly United, which has historically catered to business passengers as a core part of its mainline strategy) must adapt to the new economics of the industry. Increases in GDP and business travel are no longer reliable bellwethers of airline profitability.

(26) See Accenture, Low Cost Options Continue to Drive Business Travel Decisions, New Accenture Research Finds (Dec. 10, 2003).

15

Reports of increasing oil prices and their impact on airlines’ bottom lines have become ubiquitous in the media and analyst reports. United projects that due to rising prices, fuel will cost $1.2 billion more in 2004 than projected at the end of 2003.(27) Other airlines have issued similar reports – American Airlines a $1.2 billion increase, Delta a $800 million increase, and Continental a $400 million increase.(28) Higher projections for 2005 are now expected as well.(29)

The war in Iraq in early 2003 predictably brought a sharp jump in oil prices, with a corresponding increase in the price of jet fuel. When the ground war ended in May 2003, however, airlines, industry analysts, futures markets and the U.S. Department of Energy all predicted lower fuel costs. Oil industry analysts, for example, projected in late 2003 that oil prices would fall below $30 a barrel in 2004. The Department of Energy likewise was predicting as late as April 2004 that prices in the third quarter would fall to $32.01.(30) Instead, oil prices climbed to $55 per barrel in October 2004 before retrenching in the mid $40s in December 2004. The increase in crude oil prices has driven jet fuel prices today to nearly double what they were just 18 months ago:(31)

(27) Declaration of Michael F. Dingboom (“Dingboom Decl.”) (Ex. 106) ¶ 13.

(28) David Armstrong, Singing the Fuel Blues, SAN FRANCISCO CHRONICLE, Nov. 16, 2004 (American). Delta Air Lines 3Q2004 10-Q at 31; Continental Airlines 8K (Oct. 28, 2004).

(29) Declaration and Expert Report of Robert M. Sturtz (“Sturtz Decl.”) (Ex. 105) ¶ 24.

(30) Kasper Decl. ¶¶ 54-56.

(31) Kasper Decl. ¶¶ 52-53.

16

Exhibit 12. AVERAGE MONTHLY JET FUEL PRICES SINCE END OF IRAQ WAR.

Nor do oil prices show any signs of dropping to pre-war levels anytime soon. A host of factors (including OPEC’s intent to defend a price floor of $38 to $40 per barrel, the steady decline in oil production from non-OPEC countries, the increasing costs of finding and exploiting new oil sources, surging demand from China and other Asian countries as well as strong United States demand, and continuing political uncertainties threatening oil supplies) have combined to push prices upward. None of these factors is likely to change in the near future.(32)

United has revised its fuel forecasts accordingly. United’s forecasts through the end of 2005 use a combination of future prices expected by the market, projections from a leading consulting and information services firm, and its own evaluation of market factors.(33)

(32) Sturtz Decl. ¶¶ 32-43; Ben S. Bernanke, Federal Reserve Board, Remarks At the Distinguished Lecture Series, Darton College, Albany, Georgia (Oct. 21, 2004) (“Thus, the supply-demand fundamentals seem consistent with the view now taken by oil-market participants that the days of persistently cheap oil are over.”); Alan Greenspan, Remarks Before the Center for Strategic & International Studies (Apr. 27, 2004) (“The dramatic rise in six-year forward futures prices … can be viewed as effective long-term supply prices.”).

(33) For greater detail on United’s jet fuel forecasts see Section VI.B.6.d and the Declaration of Robert M. Sturtz (Exhibit 105).

17

Longer-term forecasts are based on futures prices for crude oil, which are the prices at which market participants offer to purchase or sell oil to be delivered in the future. Whereas the Company previously projected oil prices under $30 a barrel for the next several years, United now projects prices of $44 a barrel in 2005 and 2006 before gradually declining to $38 a barrel by 2010:

Exhibit 13. CURRENT PROJECTED OIL PRICES COMPARED TO ATSB BUSINESS PLAN.

All told, from 2004 through 2010, United projects a $7.2 billion increase over its prior fuel cost projections due to price increases.(34) An increase of this magnitude precludes profitability in today’s airline industry without further restructuring.

United has responded to these unprecedented changes with a restructuring that has been as extensive as it has been transformational. In collaboration with its stakeholders, the

(34) Dingboom Decl. ¶ 13.

18

Company has developed a suite of synergistic and cost-competitive products (such as Ted) that have strengthened its comprehensive network, dramatically reduced the cost of owning and maintaining its fleet, implemented “best-in-class” practices throughout its operations and, of course, reduced its cost of labor. See Section VI.B.5. In the process, United has reinvigorated its brand and provided its customers with operational performance at the best levels in the Company’s history.

Despite these efforts, however, persistently low yields have coupled with record fuel prices to reduce the Company’s cash flows and profitability to levels significantly lower than forecast – as has happened at virtually all airlines. These shortfalls have brought a renewed urgency to the Company’s reorganization. Unless labor costs are reduced beginning in January 2005, United will risk defaulting under its DIP financing covenants, fail to maintain an adequate cash balance and not achieve the credit metrics necessary to obtain exit financing. The entire industry joins United in these travails, which have forced bankruptcy filings by US Airways (for the second time in two years), ATA and Hawaiian Airlines and brought Delta to the brink. The only carriers not burning cash are certain of the LCCs, which have seized upon their superior cost structures to put even more pressure on legacy carriers.(35)

United’s transformation has enabled it to survive an unprecedented series of challenges over the past two years, including the aftermath of September 11, the Iraq war, SARS and the structural changes being wrought by LCCs. But, together with the Company’s other restructuring efforts, the April 2003 modifications to the Company’s CBAs have proven insufficient to overcome deteriorating yields and massive fuel cost increases. In its December

(35) Kasper Decl. ¶¶ 19, 74-85.

19

2003 application to the ATSB, United projected an operating loss of only $137 million for 1Q:04, an operating profit of $278 million for 2Q:04 and a $515 million operating profit for 3Q:04. United’s operating earnings have come in almost $940 million below these expectations through the first nine months of 2004:(36)

Exhibit 14. UNITED OPERATING EARNINGS BY QUARTER ($ MILLIONS).

|

| 2003 |

| 2004 |

| ||||

|

|

|

| Projections |

| 1-3Q Actual |

| Actuals & |

|

1st Quarter |

| (813 | ) | (137 | ) | (211 | ) | (74 | ) |

2nd Quarter |

| (431 | ) | 278 |

| 7 |

| (271 | ) |

3rd Quarter |

| 19 |

| 515 |

| (80 | ) | (595 | ) |

4th Quarter |

| (135 | ) | 161 |

| (520 | ) | (681 | ) |

Year |

| (1,360 | ) | 817 |

| (804 | ) | (1,621 | ) |

Source: UAL Corporation 10-Ks and 10-Qs plus internal forecast for 4Q:04.

In total, United’s updated financial model projects operating earnings to be $1.6 billion worse for 2004 alone, principally driven by $1.2 billion in increased fuel prices, but also reflecting a $275 million shortfall from reduced mainline unit revenue and $175 million in lower profits from United Express operations.(37) And in contrast to a previously projected year-end cash balance of approximately $2 billion, United now expects liquidity of only half that amount come December 31, which will only decrease in the traditionally lean winter months.(38)

The impact of the fierce competition for revenues is evidenced by United’s PRASM (passenger revenue per available seat mile), the measure of how much passenger

(36) Dingboom Decl. ¶ 10.

(37) Id.

(38) Id. ¶ 15.

20

revenue an airline generates per unit of capacity and a function of the number of passengers (load factors) and how much customers are paying for tickets (yields). Based on United’s rationalization of capacity and revenue initiatives, the Company’s ATSB application projected year-over-year PRASM growth of 6.3 percent in 2004. Load factors have held up their end of the equation; indeed, United now projects a load factor of 79.2 percent as compared to 77.4 percent in the ATSB application. But yields for 2004 declined significantly, from the ATSB forecast of 11.28 cents to the current expectation of 10.77 cents. This drop in yields more than offset the positive load factors, and United now expects an increase in PRASM of only 3.8 percent for 2004, fully 2.5 percentage points lower than forecast in December 2003.(39)

Nor is the outlook much brighter beyond 2004. Without additional labor savings, United now projects a $725 million operating loss for 2005 (vs. the $1.266 billion profit projected in United’s ATSB application), a $26 million operating profit in 2006 (only about 1.5% of its prior projection of $1.722 billion) and just $677 million in 2007 (about a third of its prior projection of $2.027 billion).(40)

Since filing for Chapter 11, United has relied on DIP financing to maintain the liquidity necessary to run the Company.(41) Shortly after filing for Chapter 11, the Company drew down almost $800 million from its lenders, all of the availability under the original DIP agreement. Subsequently, through a series of asset sales and amortization of the Bank One DIP, the Company paid off almost $400 million of DIP financing by July 2004. But in September

(39) Id. ¶ 12.

(40) Id. ¶ 11.

(41) Informational Brief at 34-36 (discussing DIP financing and EBITDAR covenants).

21

2004, the Company went back to its DIP lenders to increase the size of DIP financing by $500 million in order to provide the necessary liquidity during the seasonally weak winter months. Currently, the Company owes approximately $900 million to its DIP lenders.(42)

In providing DIP financing, the banks demanded various protections, including EBITDAR and minimum cash balance covenants. Similarly, subject to renegotiation of the covenants, United must meet specific EBITDAR targets each month based on the Company’s last twelve months of earnings. Missing a single covenant empowers United’s DIP lenders to foreclose on collateral that is essential to the Company’s operations.(43)

As will be discussed in Section III.B.2, United’s DIP lenders waived compliance with the October through December 2004 EBITDAR covenants, but required additional safeguards.(44) One of them was increasing the minimum cash balance covenant from $600 million to $750 million. Without additional labor savings beginning in mid-January 2005, United projects its cash balance will fall below $900 million through most of the first and second quarters of 2005, hitting monthly lows of $892 million in January, $817 million in February and $797 million in March before falling below the $750 million floor in early May: (45)

(42) Declaration and Expert Report of Todd R. Snyder (“Snyder Decl.”) (Ex. 102) ¶¶ 11-14.

(43) Id. ¶ 19.

(44) Id. ¶ 12.

(45) Dingboom Decl. ¶ 16.

22

Exhibit 15. CASH BALANCE WITHOUT LABOR COST REDUCTIONS (AS OF 12/3/04).

The projected January and February levels are too close to the covenants for an operation the size of United’s. An increase in oil prices to their October levels, significant snowstorms, further erosion of yields or a host of other events could cause a covenant breach.

In truth, the current minimum cash balance covenant does no more than recognize the operational perils of inadequate liquidity. The cash requirements of a multi-billion dollar international airline are enormous. United must maintain at least several hundred million dollars at all times to pay daily expenses and cover written but uncleared checks for essential operating costs (such as payments to vendors and utilities, landing fees, fuel, commissions to travel agents, and employee expense reimbursements). Perceptions also are important – if United’s business partners or customers become anxious about United’s liquidity, then those concerns could become reality.

Although there is no formulaic amount of cash necessary to run United, there is equally no doubt that a sustained drop below $750 million poses an unreasonable risk to the

23

continued viability of the Company. That amount is only a fraction of what United’s competitors maintain – for example, Continental, a significantly smaller airline, is targeting $1.5 billion.(46) The interests of all of United’s stakeholders demand immediate action that avoids the potentially calamitous effects of breaching DIP covenants and falling to unacceptably low levels of cash.

This fall, United projected that it might begin violating its EBITDAR covenants near the end of 2004, and swiftly began negotiations with its DIP lenders.(47) As part of those negotiations, on November 5, United provided its lenders with the Company’s updated business plan and financial model, Gershwin 5F. That business plan, while positioning United to exit bankruptcy in 2005, nevertheless projected future DIP covenant breaches without further relief from the Company’s lenders – projections which became reality when United announced on November 30 that it had not met its DIP EBITDAR covenant for October.

After reviewing Gershwin 5F, United’s DIP lenders consented to waiving compliance with the October through December EBITDAR covenants, and left open the possibility of renegotiating the covenants or further waivers.(48) It bears emphasis that securing three months of relief was no small feat – DIP lenders rarely allow debtors to operate without financial performance covenants, especially when close to $1 billion is at stake. Whether United can renegotiate its EBITDAR covenants going forward (or receive additional waivers) will depend on the Company’s progress in cutting expenses. The DIP lenders made clear their view that, absent timely and substantial cost reductions, United was not on a path to a successful

(46) Continental Airlines, Press Release, Continental Airlines Elects Deficit Reduction Contribution Relief, Sept. 3, 2004.

(47) Snyder Decl. ¶ 12.

(48) Snyder Decl. ¶¶ 12, 20.

24

reorganization. To ensure that the Company is righting the ship, under the terms of the most recent DIP amendment, United must update the DIP syndicate on or about December 15 detailing the Company’s progress in realizing cost reductions.(49) This temporary breathing room leaves the Company with precious little time to prove to the satisfaction of its DIP lenders that United can establish a cost structure compatible with the economic environment. The DIP lenders will not tolerate inaction in the face of continued losses that imperil United’s viability. The Company’s credibility depends on making and implementing the difficult decisions that are necessary.(50)

The outlook beyond early 2005 is no more promising. Without terminating and replacing its pension plans (or otherwise securing equivalent savings) and reducing labor costs by an additional $725 million per year, United will burn through more than $1 billion in cash each year until it runs out of cash:(51)

(49) Waiver, Consent and Ninth Amendment to Club DIP Facility at 2 [Docket No. 8564].

(50) Snyder Decl. ¶ 20.

(51) Dingboom Decl. ¶ 17.

25

Exhibit 16. CASH BURN WITHOUT LABOR COST REDUCTIONS.

No business can endure – and no investor would finance – continued cash burn of this magnitude. In view of the shocks and crises suffered by the airline industry over the last few years, lenders and investors will not provide exit financing unless they are convinced that United will be able to generate a healthy cash flow that is sustainable under realistic – and, in particular, not unduly optimistic – scenarios. Among other considerations, lenders are focusing on both raw cash flow and how well that cash flow covers United’s obligations.(52) As Exhibit 16 conclusively demonstrates, without the requested savings from labor, United’s cash flow will fall woefully short.

(52) Snyder Decl. ¶¶ 27-29, 31.

26

United is not alone. Carrier after carrier has struggled with the effects of low yields and high fuel costs.(53) All of United’s network competitors have taken steps to address these challenges above and beyond their prior efforts:

American. American announced a $214 million net loss in the third quarter of 2004, “typically the Company’s strongest quarter.” American further explained that “it will be very difficult for the Company to become profitable and continue to fund its obligations on an ongoing basis if the revenue environment does not improve and fuel prices remain at historically high levels for an extended period.”(54) In response, the airline renegotiated the EBITDAR covenants in its credit facility and is laying off another 1,100 pilots, mechanics and other employees.(55)

Delta. After repeatedly warning that its cash burn and losses were driving the company toward Chapter 11, Delta announced it was eliminating 6,000 - 7,000 jobs, cutting pay 10 percent across the board for all employees except pilots, increasing employees’ share of health care costs and reducing maximum vacation accruals.(56) The airline later negotiated $1 billion in annual savings from its pilots, including a 32.5 percent wage reduction and freezing and replacing their defined benefit pensions.(57) Delta simultaneously has been attempting to reduce its debt through an out-of-court restructuring.(58)

Northwest. Northwest “has incurred operating and net losses over the past three years at levels that are unsustainable on a long-term

(53) Section 1114 Memorandum at 58-62.

(54) AMR Corporation 3Q 2004 10-Q at 12-13.

(55) AMR Corporation 8-K (Sept. 22, 2004); Micheline Maynard, American Airlines Warns About Big Layoffs, N.Y. TIMES (Oct. 23, 2004).

(56) Delta Air Lines, Press Release, Delta CEO Shares Cost Savings Details in Employee Memorandum (Sept. 28, 2004).

(57) Delta Air Lines, Press Release, Delta Reaches Tentative Agreement with Pilot Union to Deliver $1 Billion in Annual Savings (Oct. 28, 2004).

(58) Delta Air Lines, Press Release, Delta Amends and Extends Exchange Offer and Increases Consideration Offered to the Holders of $2.6 Billion of Outstanding Unsecured Debt Securities and Enhanced Pass Through Certificates (Oct. 13, 2004).

27

basis. Overall operating costs remain well out of balance with the new pricing environment and the Company’s principal need at this time is to bring labor expenses within industry norms.”(59) On that score, Northwest reached a tentative agreement with its pilots’ union to save $300 million annually in costs, and is in the midst of concessionary negotiations with its other employees to achieve its target at $950 million in total labor savings.(60)

Continental. Continental recently stated: “Losses of the magnitude incurred by us since September 11, 2001 are not sustainable over the long term. With the current weak domestic yield environment caused in large part by the growth of low cost competitors and fuel prices at twenty-year highs, our cost structure is not competitive.”(61) Thus, Continental announced that it would seek $500 million in labor reductions by the end of February 2005, “the absolute minimum we need to be a survivor.”(62)

US Airways. Citing “higher fuel costs and lower domestic unit revenues,” on September 12, US Airways filed its second bankruptcy in the last two years.(63) Notably, US Airways stated that “while fuel prices accelerated the day of reckoning, it is the decline in domestic passenger unit revenues, not fuel prices, that is the central problem.”(64) The bankruptcy court granted the carrier’s Section 1113(e) motion, imposing 21 percent wage cuts and other modifications, deeming the relief “essential to the continuation of the Debtors’ business.”(65) US Airways has since negotiated permanent CBA changes with ALPA, TWU, and CWA, filed Section 1113(c) and Section 1114 motions against the unions with

(59) Northwest Airlines 3Q 2004 10-Q at 14.

(60) Northwest Airlines, Press Release, Northwest Airlines Announces It Has Reached Tentative Agreement With Its Pilots (Oct. 14, 2004)

(61) Continental Airlines 3Q 2004 10-Q at Item 2.

(62) Continental Airlines, Press Release, Continental Airlines Needs $500 Million Annual Reduction in Payroll and Benefits Costs (Nov. 18, 2004); see also Continental Airlines 3Q 2004 10-Q at Item 2.

(63) Supplemental Brief in Support of First Day Motions at 5, filed in In re US Airways, Case No. 04-13819 (Bankr. E.D. Va. Sept. 12, 2004).

(64) Supplemental Brief in Support of First Day Motions at 6, filed in In re US Airways, Case No. 04-13819 (Bankr. E.D. Va. Sept. 12, 2004).

(65) Order Authorizing Interim Relief Pursuant to Section 1113(e) of the Bankruptcy Code at 2, In re US Airways, Case No. 04-13819 (Bankr. E.D. Va. Oct. 15, 2004).

28

which it could not reach concessionary agreements, and also sought the termination of its remaining pension plans.(66)

United must take similar action, but within a much shorter time frame than carriers not in Chapter 11 because of the Company’s strict DIP covenants and lower liquidity.

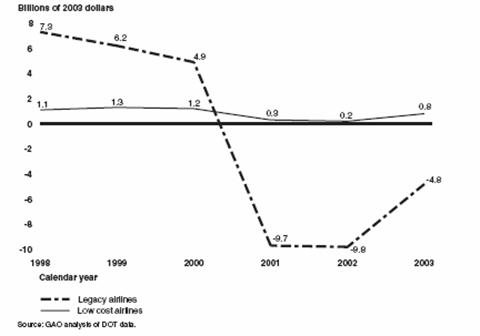

From 2001 - 2003, while legacy network carriers were collectively losing over $24.3 billion, the LCCs generated a profit of $1.3 billion:(67)

Exhibit 17. PROFITABILITY OF LEGACY AIRLINES COMPARED TO LCCS.

In fact, LCCs as a whole have generated a profit in every quarter since 2000 except for the fourth quarter of 2001. These profits have come largely at the expense of network carriers. As United and other network airlines retrenched in the wake September 11, LCCs expanded their routes.

(66) Memorandum in Support of the Debtors’ (1) Application to Reject Certain Collective Bargaining Agreements, (2) Application to Reduce Retiree Health Benefits, and (3) Motion to Approve Termination of Certain Defined Benefit Retirement Plans and Make Necessary Findings, filed in In Re US Airways, Case No. 04-13819, (Bankr. E.D. Va. Nov. 12, 2004).

(67) GAO, Legacy Carriers at 34-35.

29

Adding to the short-haul, high-density routes that had been their traditional province, LCCs increased their penetration into smaller markets and added transcontinental flights. LCCs also have been pursuing business travelers with increasing success, partly because companies have become more cost conscious and partly because LCCs have upgraded the quality of their product.(68) Profit margin comparisons tell the tale:

Exhibit 18. AIRLINE OPERATING MARGINS.

|

| 4Q 2003 |

| 1Q 2004 |

| 2Q 2004 |

| 3Q 2004 |

|

United |

| (3.7 | ) | (5.7 | ) | 0.2 |

| (1.9 | ) |

US Airways |

| (4.2 | ) | (8.4 | ) | 4.2 |

| (9.8 | ) |

Delta |

| (10.8 | ) | (11.8 | ) | (6.1 | ) | (10.9 | ) |

Continental |

| 0.7 |

| (5.9 | ) | 1.7 |

| 0.9 |

|

American |

| (5.2 | ) | (.9 | ) | 4.1 |

| (.6 | ) |

Northwest |

| (0.5 | ) | (4.1 | ) | (1.8 | ) | 2.6 |

|

Legacy Weighted Avg. |

| (4.5 | ) | (5.2 | ) | (.2 | ) | (3.0 | ) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Southwest |

| 7.3 |

| 3.1 |

| 11.5 |

| 11.4 |

|

JetBlue |

| 13.3 |

| 11.4 |

| 14.1 |

| 7.1 |

|

America West |

| 2.3 |

| 3.1 |

| 3.5 |

| (4.8 | ) |

Frontier Airlines |

| 7.9 |

| (4.1 | ) | (4.2 | ) | (0.5 | ) |

AirTran Holding |

| 8.8 |

| 4.1 |

| 11.3 |

| (4.9 | ) |

ATA Holdings |

| (2.4 | ) | (5.7 | ) | (2.8 | ) | (4.0 | ) |

LCC Weighted Avg. |

| 5.9 |

| 2.5 |

| 7.9 |

| 4.6 |

|

Of course, the picture is not all sunshine for LCCs either. Heavy dependence on flights to Florida left many LCCs scrambling when the hurricane season hit in August and contributed to ATA’s bankruptcy filing.(69) And unionized employees at Southwest, citing that airline’s consistent profitability, have negotiated more costly CBAs at a time when other carriers

(68) GAO, Legacy Carriers at 34, 42; Informational Brief at 43; Kasper Decl. ¶ 59.

(69) Affidavit of J. George Mikelsons ¶ 16, filed in In re ATA Holdings Corp., Case No. 04-19866 (Bankr. S.D. Ind. Oct. 26, 2004).

30

have been trying to reduce their costs.(70) Still, the last several years have crystallized the economic divide between legacy network carriers and LCCs. Bridging this gap will require United to improve in all areas. The Company is already reallocating its planes to focus on more profitable international flying and offering additional products to improve revenues, reducing its fleet costs and restructuring its debt – all in an effort to improve cash flow and profitability. But inasmuch as labor remains the Company’s single largest cost, United will be unable to restructure without securing additional reductions in its cost of labor. And in this respect, the changes in United’s world since the resolution of United’s first Section 1113 motion in April 2003 necessitate revisiting the viability of the Company’s pension plans.

Pensions have been a contentious issue precisely because they are the “Social Security” of bankruptcies – expensive and emotionally-charged “third rails” that are untouchable except at great peril to a Debtor-in-Possession. But persistently low yields coupled with skyrocketing fuel costs have laid bare the degree to which United’s defined benefit plans are no longer affordable. Unfortunately, the reasons why are as complicated as they are controversial and, as a result, readily lend themselves to misunderstandings. The multi-billion dollar pension issues now squarely confronting these proceedings implicate four separate plans covered by 11 different CBAs, actuarial analyses of the demographics of the plan participants, the Employee Retirement Income Security Act of 1974 (“ERISA”) and PBGC regulations that determine the benefits guaranteed to participants in terminated plans. As difficult and complex as solving this

(70) E.g., Unisys R2A Transportation Management Consultants, Unisys R2A Scorecard at 12-13 (Dec. 2003) (explaining that Southwest labor unit costs increased by 26 percent from 1997 to 2003 even as its other costs decreased by 7 percent); Southwest Reaches Deal With Attendants, Forbes.com, June 25, 2004 (“Analysts have suggested that rising labor costs could pose a problem for Southwest …. In the first three months of this year, spending on salaries and wages jumped 14 percent from a year ago.”).

31

“regulatory Rubik’s cube”(71) might be, however, United and its stakeholders (and hence this memorandum) cannot avoid reckoning with United’s pension plan liabilities if the Company is to attract exit financing and emerge successfully from Chapter 11 in the face of industry dynamics that have deteriorated since December 2003.

Two basic types of pension plans exist: defined benefit plans and defined contribution plans. A defined benefit plan guarantees participants a specific level of retirement income. Many use a formula that provides for a plan participant to receive either a percentage of final average salary as an active employee or a flat dollar amount multiplied by the number of years worked. At United, most pension benefits are calculated based on three variables: (1) years of service; (2) a multiplier; and (3) “final average earnings.” For example, the plan for management employees uses a 1.63 percent multiplier and the average of a participant’s highest consecutive five years of earnings during the last ten years before retirement. Thus, a management employee who retires at age 60 with thirty years of benefit service and whose highest five consecutive annual salaries in the last ten years were $75,000, $70,000, $65,000, $60,000 and $55,000 is entitled to an annual pension of $31,785 (30 x 1.63 percent x $65,000).(72)

Employers normally make periodic contributions to their plans, and these contributions are invested in stocks, bonds and other assets for the benefit of plan participants. Yet because payments to participants are determined by a formula that does not account for the value of the plan’s assets, employers bear the full risk of any market fluctuations that diminish a

(71) Mary Williams Walsh, A Premature Sunset for Pension Plans, N.Y. TIMES, Nov. 28, 2004.

(72) Marnell Decl. ¶¶ 11, 15; Declaration and Expert Report of Thomas J. Kuhlman (“Kuhlman Decl.”) (Ex. 104) ¶ 59.

32

plan’s investments. If the value of the plan’s assets fall below the present value of the plan’s liabilities, the plan becomes “underfunded,” and the employer alone must make up the shortfall by contributing additional funds to the plan.(73)

The last decade has witnessed a pronounced shift away from defined benefit plans toward defined contribution plans (such as 401(k) plans).(74) Defined contribution plans do not guarantee participants any specific level of retirement income and do not use any formulas to determine how much income retirees receive. Instead, each participant has an individual account to which the employee, the employer or both make contributions (ordinarily pre-tax or tax-deductible, respectively) that appreciate or depreciate over the course of the employee’s career depending largely on investment decisions made by the employee. As such, defined contribution plans cannot be “underfunded.” It is the employee, and not the employer, who bears the risk of investment gains or losses in the employee’s account.(75)

In 1974, Congress enacted ERISA to protect the “well-being and security of millions of employees and their dependents [who] are directly affected by [employee benefit plans].”(76) Title IV of ERISA “includes a mandatory Government insurance program that protects the pension benefits of . . . private-sector American workers who participate in

(73) Marnell Decl. ¶ 12; Kuhlman Decl. ¶ 59.

(74) Kuhlman Decl. ¶¶ 64-70; Steven A. Kandarian, PBGC Executive Director, Statement Before the Committee on Finance, United States Senate (Ex. 122) at 3 (Mar. 11, 2003); American Benefits Council, Pensions at the Precipice: The Multiple Threats Facing Our Nation’s Defined Benefit Pension System (Ex. 123) at 6-7 (May 2004).

(75) Marnell Decl. ¶ 13; Kuhlman Decl. ¶ 60.

(76) 29 U.S.C. § 1001(a); see generally Bradley P. Rothman, 401(k) Plans in the Wake of Enron Debacle, 54 FLA. L. REV. 921 (2002); James A. Wooten, The Most Glorious Story of Failure in the Business: The Studebaker-Packard Corporation and the Origins of ERISA, 49 BUFF. L. REV. 683 (2001).

33

[terminated] plans covered by [ERISA].”(77) The PBGC, “a wholly-owned United States government corporation, administers the pension plan termination insurance program.”(78) The PBGC assumes control of plans terminated with assets less than the guaranteed level and guarantees the payment of vested benefits to participants in “virtually all ‘defined benefit’ pension plans sponsored by private employers” up to a maximum annual benefit per person, even if a terminated pension plan itself does not have sufficient assets to pay the guaranteed benefits.(79)

The PBGC is not supported by taxpayers out of general tax revenues, but instead derives its funds from four sources: (1) premiums paid by the sponsors of insured pension plans; (2) assets of pension plans taken over by the PBGC; (3) recoveries from former plan sponsors; and (4) investment earnings on the PBGC’s assets.(80) As of year-end 2003, the PBGC insured the pensions of nearly 44 million participants in more than 32,000 active pension plans. The PBGC is also paying benefits to 934,000 participants in 3,240 terminated pension plans.(81) Although the PBGC is presently running a deficit, its Executive Director recently reassured Congress that the single-employer fund has sufficient assets to meet “obligations for a number of years.”(82) And should it prove necessary for the PBGC to assume control of United’s pension plans, the PBGC would use the billons of dollars that United has contributed to the plans (as well as the value of its claim in these proceedings) to pay benefits to the Company’s retirees for years before having to dip into the PBGC’s other funds.

(77) PBGC v. LTV Corp., 496 U.S. 633, 637 (1990).

(78) In re Bayly Corp., 163 F.3d 1205, 1207 (10th Cir. 1998); see also 29 U.S.C. § 1302.

(79) LTV, 496 U.S. at 637 n.1; see also 29 U.S.C. § 1322(a). The PBGC does not insure or otherwise regulate defined contribution plans.

(80) PBGC v. Republic Techs. Int’l, LLC, 287 F. Supp. 2d 815, 817-18 (N.D. Ohio 2003).

(81) PBGC 2003 Annual Report at 7.

(82) PBGC 2003 Annual Performance and Accountability Report at 7 (Nov. 15, 2004).

34

Once an employer establishes a defined benefit plan, “it must fund the plan in accordance with the minimum funding standard imposed by [ERISA and the Internal Revenue Code (“IRC”)].”(83) Importantly, “[t]he statutory rules impose both a minimum required contribution and a maximum amount that may be deducted annually.”(84)

An employer (such as United) with a calendar-year plan pays its minimum required contribution in quarterly installments on April 15, July 15 and October 15 of each calendar year and January 15 of the following year.(85) In addition, employers make a “true-up” payment by September 15 of the following year to ensure full payment of the minimum required funding contribution for the plan year. An employer’s plan year contributions “must be sufficient to eliminate any ‘accumulated funding deficiency’” in its plans.(86) An accumulated funding deficiency arises if the contributions made by September 15 of the following year are insufficient to pay the total minimum required contribution for the year.(87)

The minimum funding contribution is determined as of the beginning of a plan year and has both a “current” component (the portion required to fund the pension benefits that are expected to accrue during the plan year) and a “past service” component (the portion related

(83) In re Sunarhauserman Inc., 126 F.3d 811, 815 (6th Cir. 1997); see also 26 U.S.C. § 412; 29 U.S.C. § 1082. As the Sunarhauserman court recognized, the ERISA and IRC citations regarding the minimum funding standards are “parallel.” Id. at 815 n.3. This Memorandum generally will cite only to the IRC.

(84) Sunarhauserman, 126 F.3d at 815 (citing 29 U.S.C. § 1082 and 26 U.S.C. §§ 404, 412). The funding rules established by Congress are different than what an actuary would determine based on generally accepted actuarial principles. An actuary would not determine funding requirements based on short-term fluctuations in the value of plan assets, but would instead determine funding based on reasonable long-term assumptions regarding the expected return on the plan’s investments.

(85) 26 U.S.C. § 412(m).

(86) Sunarhauserman, 126 F.3d at 815 (citing 29 U.S.C. § 1082 (a)(3) and 26 U.S.C. § 412 (a)(3)).

(87) Marnell Decl. ¶ 24.

35

to prior years of service that is actuarially allocated to be paid during a particular plan year for active employees). ERISA originally allowed employers to amortize underfunded amounts related to past service liberally over a multiple-year period. That all changed in 1987 with the creation of the “deficit reduction contribution” (“DRC”).(88)

Congress imposed the DRC to shore up pension plans that were poorly funded.(89) Although the particulars of the DRC entail complex calculations, the gist is as follows: the sponsor of a plan whose assets fall below 90 percent of the plan’s liabilities for the current year and were not 90 percent or more for any two consecutive years of the last three or below 80 percent in the current year will be subject to the DRC. In practical terms, plans sponsors subject to the DRC are required to contribute enough cash within the next three to five years to cover 90 percent of the funding deficit.(90) On a current liability basis, United’s plans, in aggregate, were funded at 64 percent as of January 1, 2004.(91)

It would be difficult to overstate how profoundly the DRC has impacted the funding – or, more precisely, the underfunding – of defined benefit plans. Insofar as plan sponsors are concerned, it is as if Congress had issued an edict to homeowners with 30-year mortgages that, if the value of their homes drop below 80 percent of the purchase price (for whatever reason), their loans will be accelerated such that the balance will suddenly become due in just three to five years. Worse yet, this accelerated funding requirement kicks in at a time

(88) Marnell Decl. ¶¶ 26, 38.

(89) 26 U.S.C. § 412(l).

(90) 26 U.S.C. § 412(l)(9).

(91) Marnell Decl. ¶ 38.

36

when homeowners will likely find it most difficult to repay the loans because of the very same overarching economic circumstances that caused the value of their homes to drop.(92)

At the same time, ERISA limits the amount of “surplus” contributions that can be made to well-funded plans. Specifically, the “full funding limit” limits the contributions that an employer can make to a pension plan by imposing a 10 percent excise tax on “excess contributions” and making them non-deductible.(93) Moreover, the definition of a “fully funded” plan was extremely restrictive over the past decade-and-a-half and only recently has become more relaxed. When Congress passed ERISA in 1974, a plan was considered “fully funded” only if plan assets exceeded the employer’s actuarial accrued liability through the coming year, including future pay increases.(94) From 1987 through 2003, however, Congress legislated a new and often lower criterion for full funding – one that looked exclusively at plan assets measured against a multiplier of the plan’s “current” liability, which excludes the value of anticipated pay increases.(95) The upshot was that plans reached full funding status far more quickly.(96) As a result, while the DRC required companies to shore up underfunded pension plans more rapidly in

(92) See, e.g., Steven A. Kandarian, PBGC Executive Director, Testimony Before the Special Committee of Aging, United States Senate (Ex. 124) at 14 (Oct. 14, 2003) (“The DRC is a part of a system of flawed funding rules, which should be reviewed and reformed. … When the DRC kicks in, it often hits employers with huge contribution increases when they can least afford them.”); American Benefits Council, Pensions at the Precipice at 19-20 (“These rules … requir[e] additional contributions during difficult economic times – an unwelcome result from a business planning perspective and one that discourages companies from sponsoring defined benefit plans.”).

(93) Marnell Decl. ¶ 129; 26 U.S.C. § 412(c)(7); 26 U.S.C. § 4972.

(94) 26 U.S.C. § 412(c)(7)(A)(i)(II); see also Jack L. VanDerhei, Testimony Before the Subcommittee on Employer-Employee Relations, Committee on Education and the Workforce, United States House of Representatives, Hearing on Strengthening Pension Security: Examining the Health and Future of Defined Benefit Pension Plans at 6 (June 4, 2003).

(95) 26 U.S.C. § 412(c)(7)(A)(i)(I). This multiple was 150 percent of current liability in 1987 and subsequently increased to 170 percent of current liability. Starting with the 2004 plan year, the full funding limit based on current liability no longer applies. 26 U.S.C. § 412(c)(7)(F).

(96) VanDerhei, Testimony Before the Subcommittee on Employer-Employee Relations at 6-7.

37

times of economic duress, employers were deterred from making “rainy day” contributions to pension plans during periods of strong financial performance.

The combination of the DRC and full funding limit left cyclical businesses trying to fund defined benefit plans ill-equipped to cope with the volatility of today’s economy.(97) As former PBGC Executive Director Steven Kandarian put it: “After years of the funding rules allowing companies to make little or no contributions, many companies are suddenly required to make contributions of hundreds of millions of dollars to their plans at a time when they are facing other economic pressures. Although the law’s complicated funding rules were designed, in part, to minimize the volatility of funding contributions, the current rules have clearly failed to achieve this goal.”(98)

ERISA flatly prohibits changes to pension plans that would in any way reduce benefits that participants have already earned.(99) This provision is known as the “anti-cutback rule” because it forbids employers from decreasing accrued benefits even if plan beneficiaries were to agree to the reduction. The anti-cutback rule disallows (i) decreasing benefits that

(97) See, e.g., Rep. John Boehner, Press Release, Defined Benefit Pension System Needs Reform (Aug. 5, 2004) (Ex. 125) (“One federal requirement hits companies particularly hard: the Catch-22 legal requirement that forces employers to make additional pension contributions during difficult economic times when they can least afford them, even while limiting their ability to better fund their plans during healthier economic times.”); Michael J. Collins, Reviving Defined Benefit Plans: Analysis And Suggestions For Reform, 20 VA. TAX REV. 599, 643-44 (2001).

(98) Kandarian, Testimony Before The Special Committee on Aging at 13-14 (Ex. 124). Current PBGC Director Bradley Belt agrees that the “Byzantine . . . funding rules saddle financially healthy companies with needless complexity, excessive volatility, and perverse disincentives to funding up.” Bradley D. Belt, PBGC Executive Director, Presentation to the 6th Annual Conference of the Retirement Research Consortium (Ex. 126) at 5 (Aug. 13, 2004).

(99) See 26 U.S.C. § 411(d)(6).

38

participants have already earned, (ii) delaying eligibility for early retirement for benefits already accrued, or (iii) eliminating the option to be paid one’s benefits all at once as a lump sum for benefits already accrued.(100)

The practical effect of the anti-cutback rule, especially when coupled with the DRC, is that employers cannot materially reduce required contributions without terminating their pension plans. Nor can employers and plan participants reduce accrued pension liabilities by agreeing to reductions (or even to “rollbacks” of any recent improvements made to the plans).(101) In tandem with the minimum and maximum funding rules, the anti-cutback rule prevents employers from reducing their funding obligations even in times (such as those presently confronting United) when it is difficult to make contributions. In short, ERISA and the IRC set up pension funding as an all-or-nothing proposition: employers either must fund their irreducible accrued liabilities in full or seek to terminate the plans altogether.(102)

“Termination” is an ERISA term of art that overstates the consequences for plan participants, whose benefits are never “zeroed out.” Rather, the PBGC guarantees a certain level of continuing pension payments to vested plan participants. In addition, employers typically

(100) 29 U.S.C. § 1054(g). See generally Heinz v. Central Laborers’ Pension Fund, 303 F.3d 802, 804-05 (7th Cir. 2002).

(101) Although employers can reduce benefit accruals on a going-forward basis, this merely creates a “wear-away” period for existing employees during which the benefits to be paid under the old, higher formula remain in place until the benefits under the new formulas catch up with (and ultimately add to) the accrued benefits. See generally American Benefits Council, “Wear-Away” Prohibitions Should Not Include Early Retirement Subsidies (undated).

(102) The IRS does offer two temporary safety valves. The first is to seek a short-term funding waiver. This option is unavailable to United for the reasons set forth in Section VI.B.6.d.(ii). The second is to request the IRS to extend the amortization period for any unfunded accrued liability. 26 U.S.C. § 412(e). This would not help United either because such amortization relief does not decrease or delay the DRC-required contributions.

39

institute “replacement plans” to provide retirement benefits for active employees on a going-forward basis.

An employer may terminate an underfunded pension plan through a process known as a “distress termination.”(103) An employer in Chapter 11 typically seeks to satisfy the “reorganization distress test,” which requires proving that “unless the plan is terminated, [the sponsor] will be unable to pay all its debts pursuant to a plan of reorganization and will be unable to continue in business outside the Chapter 11 reorganization process.”(104) The PBGC cannot process an employer-initiated distress termination, however, if the termination is prohibited by a CBA.(105) Accordingly, a debtor seeking to terminate a plan required by a CBA must either obtain the consent of the participants’ union(s) to the distress termination or secure an order authorizing the rejection of the CBA pursuant to Section 1113 of the Bankruptcy Code.(106) It is this impediment to a potential ERISA distress termination (and, insofar as pension plans, this impediment alone) that United seeks to address as part of the present Section 1113 process.

(103) 29 U.S.C. § 1341(c). A “standard termination” may be pursued by an employer unilaterally (unless prohibited by collective bargaining agreements), but only if the pension plan has assets sufficient to purchase annuities or provide lump-sum payments in full and complete satisfaction of all liabilities. 29 U.S.C. § 1341(b).

(104) 29 U.S.C. § 1341(c)(2).

(105) 29 U.S.C. § 1341(a)(3).

(106) 29 C.F.R. § 4041.7(b). By contrast, the PBGC may “involuntarily” terminate a pension plan on the PBGC’s own initiative even if doing so would contradict the terms of a CBA. The PBGC may “involuntarily” terminate a pension plan if the PBGC determines that: (1) the plan has not met the minimum funding standards; (2) “the plan will be unable to pay benefits when due;” or (3) “the possible long-run loss [to the PBGC] with respect to the plan may reasonably be expected to increase unreasonably if the plan is not terminated.” 29 U.S.C. § 1342(a)(3).

40

Once a plan is approved for termination, a “termination date” is set.(107) On that date, all participants stop accruing benefits, their guaranteed benefit levels are set(108) and the PBGC takes over the assets of the terminated plan and assumes responsibility for all plan administration.(109) The PBGC pays guaranteed benefits to participants out of the terminated plan’s assets and, to the extent the plan’s funds are insufficient, the PBGC’s own funds.(110) The sponsor is relieved of any further such responsibility and stops making any contributions to the plan.(111)

The PBGC pays non-forfeitable pension benefits to all plan participants.(112) How much of a participant’s pre-termination benefits are received depends on the participant’s ERISA “Priority Category.” The most significant categories are “Priority Category 4” (PC4) and “Priority Category 3” (PC3). PC4 includes all plan participants with vested benefits. The PBGC will pay all PC4 participants the benefits to which they were entitled prior to termination, subject to two important qualifications:(113)

(107) 29 U.S.C. § 1348; Pineiro v. PBGC, 318 F. Supp. 2d 67, 72 (S.D.N.Y. 2003).

(108) Pineiro, 318 F. Supp. 2d at 72.

(109) PBGC v. LTV Corp., 496 U.S. 633, 637 (1990); 29 U.S.C. § 1342(d). These powers technically belong to a trustee appointed to administer the plan, but in practice the PBGC always serves as trustee. LTV, 496 U.S. at 637; Pineiro, 318 F. Supp. 2d at 72.

(110) LTV, 496 U.S. at 637-38.

(111) Id. at 637. Participants in a terminated plan cannot assert personal claims against the plan sponsor for any shortfall between the payments to which they were entitled under the plan and the payments guaranteed by the PBGC. See United Steelworkers of Am., AFL-CIO v. United Eng’g, Inc., 52 F.3d 1386, 1393-94 (6th Cir. 1995).

(112) 26 C.F.R. § 1.401-6(a). A benefit is non-forfeitable “if there is no contingency under the plan that may cause the employee to lose his rights.” 26 C.F.R. § 1.402(b)-1(d)(2).

(113) Marnell Decl. ¶ 62.

41

First, the PBGC only pays up to a maximum annual guaranteed benefit level, which varies based on a participant’s age.(114) This maximum guarantee works differently depending on whether a participant is a current retiree or active employee when the plan terminates. For current retirees, the cap is based on their age when the plan terminates (as opposed to their age at retirement). For a plan terminating in 2005, the maximum annual guaranteed benefit for current retirees who are 65 is $45,614.(115) The maximum is reduced for current retirees who are younger than 65 when the plan terminates; for instance, the 2005 annual maximum for age 60 is $29,649.(116) Conversely, the maximum increases for retirees older than age 65 when the plan terminates; for example, the maximum annual benefit for current retirees who are 67 when a plan terminates is $55,192.(117) This cap is set based on a retiree’s age at plan termination and never changes.(118)

For active employees, the PC4 maximum depends on when an employee begins to draw pension benefits from the terminated plan, which usually is immediately after he retires. For a plan terminating in 2005, active employees who retire at age 60 are subject to a $29,649 annual cap, those who retire at age 65 are subject to a $45,614 cap, and those who retire at age 67 are subject to a $55,192 cap. Maximums for active employees are fixed on the first day they commence their pension benefits and never change.(119)

(114) 29 U.S.C. § 1322.

(115) 29 C.F.R. Pt. 4011, App. B.

(116) Id.

(117) 29 C.F.R. § 4022.22.

(118) Marnell Decl. ¶ 63.

(119) Id. ¶ 64.

42

Second, the PBGC backs out increases in vested benefits attributable to plan improvements in the five years preceding termination. The portion of a recipient’s guaranteed benefits attributable to such amendments is phased in at 20 percent annual increments.(120) For example, if a plan amendment adopted three years prior to termination adds $1,000 a month to a recipient’s pension check, the PBGC would honor only $600 (3 years x 20 percent or 60 percent) of that increase (up to the maximum guaranteed level).

PC4 participants who retired or were eligible to retire at least three years prior to the plan termination date may also be eligible for additional PC3 benefits. If there are sufficient assets in a plan, PC3 participants receive the benefit payable under the plan provisions in effect five years prior to termination, calculated at the participant’s age, service, and pay three years prior to plan termination. Significantly, unlike PC4 benefits, PC3 benefits are not capped and do not vary by age at retirement. At the same time, PC3 benefits are paid at their full amount only if there are sufficient assets in the plan; if not, PC3 benefits are paid pro rata.(121) Thus, depending upon the funding level of their particular plan, retirees or senior employees eligible for retirement many receive more than the PC4 caps that are widely reported in the press.(122)

(120) Marnell Decl. ¶ 65; 29 U.S.C. § 1322(b).