Exhibit D

TABLE OF CONTENTS

| | | | |

INTRODUCTION | | | D-1 | |

| |

SUMMARY | | | D-2 | |

| |

RECENT DEVELOPMENTS | | | D-4 | |

| |

UNITED MEXICAN STATES | | | D-26 | |

| |

Geography and Population | | | D-26 | |

Form of Government | | | D-26 | |

Legal and Political Reforms | | | D-29 | |

Foreign Affairs, International Organizations and International Economic Cooperation | | | D-31 | |

Internal Security | | | D-31 | |

Environment | | | D-32 | |

| |

THE ECONOMY | | | D-35 | |

| |

General | | | D-35 | |

The Role of the Government in the Economy; Privatization | | | D-35 | |

Gross Domestic Product | | | D-36 | |

Employment and Labor | | | D-40 | |

Principal Sectors of the Economy | | | D-43 | |

| |

FINANCIAL SYSTEM | | | D-55 | |

| |

Monetary Policy, Inflation and Interest Rates | | | D-55 | |

Exchange Controls and Foreign Exchange Rates | | | D-58 | |

Banking System | | | D-59 | |

Banking Supervision and Support | | | D-62 | |

Credit Allocation by Sector | | | D-63 | |

Insurance Companies, Mutual Funds and Auxiliary Credit Institutions | | | D-63 | |

Securities Markets | | | D-64 | |

| |

FOREIGN TRADE AND BALANCE OF PAYMENTS | | | D-66 | |

| |

Foreign Trade | | | D-66 | |

Geographic Distribution of Trade | | | D-68 | |

In-bond Industry | | | D-69 | |

Balance of Payments and International Reserves | | | D-70 | |

Direct Foreign Investment in Mexico | | | D-72 | |

Memberships in International Institutions | | | D-73 | |

| |

PUBLIC FINANCE | | | D-74 | |

| |

General | | | D-74 | |

Fiscal Policy | | | D-76 | |

The Budget | | | D-77 | |

Revenues and Expenditures | | | D-79 | |

Government Agencies and Enterprises | | | D-85 | |

| |

PUBLIC DEBT | | | D-86 | |

| |

General | | | D-86 | |

Public Debt Classification | | | D-86 | |

Historical Balance of Public Sector Borrowing Requirements | | | D-87 | |

Internal Debt | | | D-87 | |

External Debt | | | D-90 | |

Liability Management and Debt Reduction Transactions | | | D-94 | |

Debt Record | | | D-94 | |

IMF Credit Lines | | | D-94 | |

External Securities Offerings | | | D-94 | |

i

LIST OF TABLES

| | | | |

Table No. 1 - Party Representation in Congress | | | D-4 | |

Table No. 2 - Real GDP and Expenditures (In Billions of Pesos) | | | D-6 | |

Table No. 3 - Real GDP and Expenditures (As a Percentage of Total GDP) | | | D-7 | |

Table No. 4 - Real GDP by Sector | | | D-8 | |

Table No. 5 - Real GDP Growth by Sector | | | D-9 | |

Table No. 6 - Industrial Manufacturing Output by Sector | | | D-10 | |

Table No. 7 - Money Supply | | | D-11 | |

Table No. 8 - Rates of Change in Price Indices | | | D-12 | |

Table No. 9 - Average Cetes, CPP and TIIE Rates | | | D-13 | |

Table No. 10 - Exchange Rates | | | D-14 | |

Table No. 11 - Exports and Imports | | | D-15 | |

Table No. 12 - Balance of Payments | | | D-17 | |

Table No. 13 - International Reserves and Net International Assets | | | D-18 | |

Table No. 14 - Budgetary Expenditures; 2017 Expenditure Budget | | | D-19 | |

Table No. 15 - Budgetary Results; 2017 Budget Assumptions and Targets | | | D-19 | |

Table No. 16 - Public Sector Budgetary Revenues | | | D-20 | |

Table No. 17 - Historical Balance of Public Sector Borrowing Requirements | | | D-21 | |

Table No. 18 - Gross and Net Internal Debt of the Public Sector | | | D-21 | |

Table No. 19 - Gross and Net Internal Debt of the Government | | | D-22 | |

Table No. 20 - Summary of External Public Debt | | | D-23 | |

Table No. 21 - Summary of External Public Debt by Currency | | | D-23 | |

Table No. 22 - Net External Debt of the Public Sector | | | D-23 | |

Table No. 23 - Gross External Debt of the Government by Currency | | | D-24 | |

Table No. 24 - Net External Debt of the Government | | | D-24 | |

Table No. 25 - Net Debt of the Government | | | D-24 | |

Table No. 26 - Selected Comparative Statistics | | | D-26 | |

Table No. 27 - Party Representation in Congress | | | D-28 | |

Table No. 28 - Real GDP and Expenditures | | | D-36 | |

Table No. 29 - Real GDP and Expenditures | | | D-37 | |

Table No. 30 - Real GDP by Sector | | | D-38 | |

Table No. 31 - Real GDP Growth by Sector | | | D-39 | |

Table No. 32 - Unemployed Population by Age and Gender | | | D-40 | |

Table No. 33 - Economically Active Population by Sector | | | D-41 | |

Table No. 34 - Underemployment as Percentage of Active Population from 2012 to 2016 | | | D-41 | |

Table No. 35 - Industrial Manufacturing Output by Sector | | | D-44 | |

Table No. 36 - Industrial Manufacturing Output Differential by Sector | | | D-45 | |

Table No. 37 - Tourism Revenues and Expenditures | | | D-48 | |

Table No. 38 - Development of Mexico’s Road Network | | | D-50 | |

ii

| | | | |

Table No. 39 - Communications | | | D-51 | |

Table No. 40 - Mining | | | D-52 | |

Table No. 41 - Electricity Generation by Source | | | D-53 | |

Table No. 42 - Money Supply | | | D-56 | |

Table No. 43 - Changes in Price Indices | | | D-57 | |

Table No. 44 - Average Cetes, CPP and TIIE Rates | | | D-58 | |

Table No. 45 - Exchange Rates | | | D-59 | |

Table No. 46 - Commercial Banking System | | | D-61 | |

Table No. 47 - Credit Allocation by Sector | | | D-63 | |

Table No. 48 - Mexican Stock Exchange Performance | | | D-65 | |

Table No. 49 - Exports and Imports | | | D-67 | |

Table No. 50 - Distribution of Mexican Merchandise Exports | | | D-68 | |

Table No. 51 - Distribution of Mexican Merchandise Imports | | | D-69 | |

Table No. 52 - In-bond Industry | | | D-69 | |

Table No. 53 - In-bond Industry Revenues | | | D-69 | |

Table No. 54 - Balance of Payments | | | D-70 | |

Table No. 55 - International Reserves and Net International Assets | | | D-71 | |

Table No. 56 - 2016 Foreign Investment by Sector | | | D-72 | |

Table No. 57 - Direct Foreign Investment | | | D-73 | |

Table No. 58 - Public Sector Balance | | | D-75 | |

Table No. 59 - Public Sector Borrowing Requirements | | | D-75 | |

Table No. 60 - Budgetary Expenditures; 2017 Expenditure Budget | | | D-78 | |

Table No. 61 - Budgetary Results; 2017 Budget Assumptions and Targets | | | D-78 | |

Table No. 62 - Selected Public Finance Indicators | | | D-79 | |

Table No. 63 - Public Sector Budgetary Revenues | | | D-80 | |

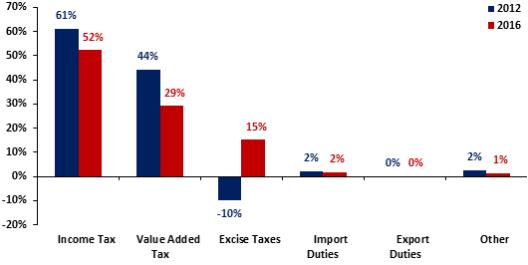

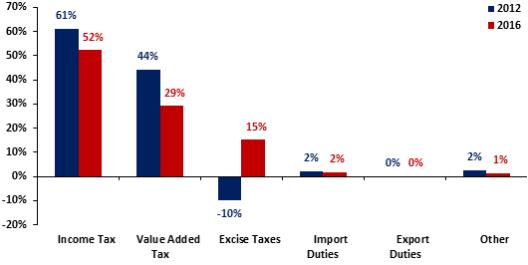

Table No. 64 - Composition of Tax Revenues 2012 vs. 2016 | | | D-81 | |

Table No. 65 - Public Sector Budgetary Expenditures | | | D-83 | |

Table No. 66 - Principal Government Agencies, Productive State-Owned Companies and Enterprises at December 31, 2016 | | | D-85 | |

Table No. 67 - Historical Balance of Public Sector Borrowing Requirements | | | D-87 | |

Table No. 68 - Gross and Net Internal Debt of the Public Sector | | | D-88 | |

Table No. 69 - Gross and Net Internal Debt of the Government | | | D-89 | |

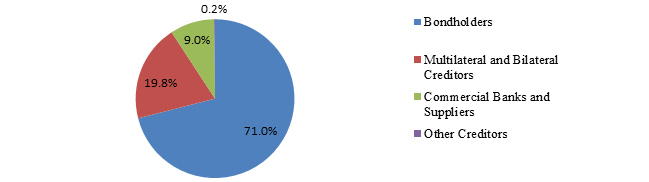

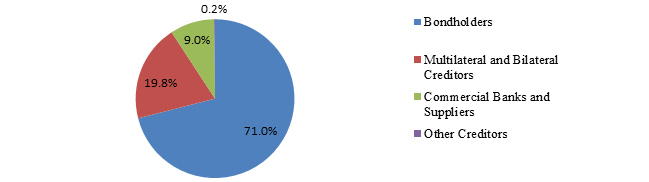

Table No. 70 - Public Debt Creditors at December 31, 2016 | | | D-90 | |

Table No. 71 - Summary of External Public Debt | | | D-91 | |

Table No. 72 - Summary of External Public Debt by Currency | | | D-91 | |

Table No. 73 - Net External Debt of the Public Sector | | | D-91 | |

Table No. 74 - Amortization Schedule of Total Public Sector External Debt | | | D-92 | |

Table No. 75 - Gross External Debt of the Government | | | D-93 | |

Table No. 76 - Net External Debt of the Government | | | D-93 | |

Table No. 77 - Net Debt of the Government | | | D-93 | |

iii

INTRODUCTION

References herein to “U.S.$”, “$”, “U.S. dollars” or “dollars” are to United States dollars. References herein to “pesos” or “Ps.” are to the lawful currency of the United Mexican States (Mexico). References herein to “nominal” data are to data expressed in pesos that have not been adjusted for inflation, and references to “real” data are to data expressed in inflation-adjusted pesos. Unless otherwise indicated, U.S. dollar equivalents of peso amounts as of a specified date are based on the exchange rate for such date announced by Banco de México for the payment of obligations denominated in currencies other than pesos and payable within Mexico, and U.S. dollar equivalents of peso amounts for a specified period are based on the average of such announced daily exchange rates for such period. Note that due to fluctuations in the peso/dollar exchange rate, the exchange rate on any subsequent date could be materially different from the rate provided in this document.

Banco de México calculates the announced peso/dollar exchange rate daily, on the basis of an average of rates obtained in a representative sample of financial institutions whose quotations reflect market conditions for wholesale operations. Banco de México uses this rate when calculating Mexico’s official economic statistics. The exchange rate announced by Banco de México on September 28, 2017 (which took effect on the second business day thereafter) was Ps. 18.1300 = U.S.$1.00. See “Foreign Trade and Balance of Payments—Exchange Controls and Foreign Exchange Rates.”

Under the Ley Monetaria de los Estados Unidos Mexicanos (Mexican Monetary Law), payments which are required to be made in Mexico in a foreign currency, whether by agreement or upon a judgment of a Mexican court, may be discharged in pesos at the prevailing peso exchange rate at the time of payment.

The fiscal year of the Federal Government of Mexico (the Government) is aligned with the calendar year and ends on December 31 of each year. The fiscal year ended December 31, 2016 is referred to as “2016” and all other years are referred to in a similar manner.

The information included herein reflects the most recent information available at the time of filing.

D-1

SUMMARY

The following is a summary of Mexico’s economic information for the period 2012-2016 and the second quarter of 2017. This summary does not purport to be complete and is qualified by the more detailed information appearing elsewhere in this document.

United Mexican States

| | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | |

| | | 2012(1) | | | 2013(1) | | | 2014(1) | | | 2015(1) | | | 2016(1) | | | Second

quarter 2016(1) | | | Second quarter

2017(1) | |

| | | (in millions of dollars or pesos, except percentages) | |

The Economy | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | |

GDP: | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | |

Nominal | | Ps. | 15,626,907 | | | Ps. | 16,118,031 | | | Ps. | 17,259,799 | | | Ps. | 18,261,422 | | | Ps. | 19,539,870 | | | Ps. | 18,890,471 | (2) | | Ps. | 20,694,333 | (2) |

Real(3) | | Ps. | 13,287,534 | | | Ps. | 13,468,255 | | | Ps. | 13,773,994 | | | Ps. | 14,138,964 | | | Ps. | 14,462,162 | | | Ps. | 14,207,172 | (2) | | Ps. | 14,529,322 | (2) |

Real GDP growth(3) | | | 4.0 | % | | | 1.4 | % | | | 2.2 | % | | | 2.5 | % | | | 2.3 | % | | | 2.4 | % | | | 2.3 | % |

Increase in national consumer price index | | | 3.6 | % | | | 4.0 | % | | | 4.1 | % | | | 2.1 | % | | | 3.4 | % | | | 2.5 | % | | | 6.3 | % |

Merchandise export growth(4) | | | 6.1 | % | | | 2.5 | % | | | 4.4 | % | | | (4.1 | )% | | | (1.7 | )% | | | (3.0 | )% | | | 9.2 | % |

Non-oil merchandise export growth(4) | | | 8.5 | % | | | 4.0 | % | | | 7.3 | % | | | 0.8 | % | | | (0.7 | )% | | | (2.8 | )% | | | 9.5 | % |

Oil export growth | | | (6.2 | )% | | | (6.6 | )% | | | (14.4 | )% | | | (45.3 | )% | | | (18.5 | )% | | | (36.7 | )% | | | 30.5 | % |

Oil exports as % of merchandise exports(4) | | | 14.3 | % | | | 13.0 | % | | | 10.7 | % | | | 6.1 | % | | | 5.0 | % | | | 5.0 | % | | | 6.0 | % |

Balance of payments: | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | |

Current account | | $ | (15,463 | ) | | $ | (31,078 | ) | | $ | (23,125 | ) | | $ | (28,847 | ) | | $ | (22,420 | ) | | $ | (14,128 | ) | | $ | (8,719 | ) |

Trade balance | | $ | 18 | | | $ | (1,195 | ) | | $ | (3,065 | ) | | $ | (14,682 | ) | | $ | (13,125 | ) | | $ | (7,054 | ) | | $ | (2,910 | ) |

Capital account | | $ | (106 | ) | | $ | 2,302 | | | $ | 27 | | | $ | (87 | ) | | $ | (75 | ) | | $ | (34 | ) | | $ | 1.3 | |

Change in international reserves(5) | | $ | (17,841 | ) | | $ | (13,150 | ) | | $ | (15,482 | ) | | $ | (18,085 | ) | | $ | 428 | | | $ | 1,233 | | | $ | 2,629 | |

International reserves (end of period)(6) | | $ | 163,592 | | | $ | 176,579 | | | $ | 193,045 | | | $ | 176,735 | | | $ | 177,335 | | | $ | 174,246 | | | $ | 174,246 | |

Net international assets(7) | | $ | 166,472 | | | $ | 178,686 | | | $ | 196,288 | | | $ | 177,629 | | | $ | 178,057 | | | $ | 181,511 | | | $ | 175,425 | |

Ps./$ representative market exchange rate (end of period)(8) | | Ps. | 12.9658 | | | Ps. | 13.0843 | | | Ps. | 14.7414 | | | Ps. | 17.2487 | | | Ps. | 20.6194 | | | Ps. | 18.4646 | | | Ps. | 18.0626 | |

28-day Cetes (Treasury bill) rate (% per annum)(9) | | | 4.2 | % | | | 3.8 | % | | | 3.0 | % | | | 3.0 | % | | | 4.2 | % | | | 3.6 | % | | | 6.4 | % |

Unemployment rate (end of period) | | | 4.4 | % | | | 4.3 | % | | | 3.8 | % | | | 4.0 | % | | | 3.4 | % | | | 3.9 | % | | | 3.5 | % |

| | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | |

| | | 2012(3) | | | 2013(3) | | | 2014(3) | | | 2015(3) | | | 2016(1) (3) | | | Second

quarter

2016(1)(3) | | | Second

quarter

2017(1)(3) | | | 2017

Budget (10)(3) | |

| | | (in billions of constant pesos, except percentages) | |

Public Finance(11) | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | |

Public sector revenues | | | Ps. 3,515 | | | | Ps. 3,800 | | | | Ps. 3,983 | | | | Ps. 4,267 | | | | Ps. 4,846 | | | | Ps. 2,339 | | | | Ps. 2,656 | | | | Ps. 4,361 | |

As % of GDP | | | 22 | .5% | | | 23 | .6% | | | 23 | .1% | | | 23 | .4% | | | 24 | .8% | | | 12 | .4% | | | 12 | .8% | | | 22 | .9% |

Public sector expenditures | | | Ps. 3,920 | | | | Ps. 4,178 | | | | Ps. 4,528 | | | | Ps. 4,893 | | | | Ps. 5,347 | | | | Ps. 2,465 | | | | Ps. 2,531 | | | | Ps. 4,856 | |

As % of GDP | | | 25 | .1% | | | 25 | .9% | | | 26 | .2% | | | 26 | .8% | | | 27 | .4% | | | 13 | .0% | | | 12 | .2% | | | 24 | .2% |

Public sector balance as % of GDP(12) | | | (2 | .6)% | | | (2 | .3)% | | | (3 | .2)% | | | (3 | .5)% | | | (2 | .6)% | | | (0 | .6)% | | | 0. | 7% | | | (2 | .4)% |

D-2

| | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | |

| | | December 31, | | | Second

quarter

2016(1) | | | Second

quarter

2017(1) | |

| | | 2012 | | | 2013 | | | 2014 | | | 2015(1) | | | 2016(1) | | | |

| | | (in billions of dollars or pesos, except percentages) | |

Public Debt(13) | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | |

Historical Balance of Public Sector Borrowing Requirements as % of nominal GDP(14) | | | 37.7 | % | | | 40.4 | % | | | 43.1 | % | | | 47.3 | % | | | 50.1 | % | | | 46.9 | % | | | 43.9 | % |

Internal Debt(15) | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | |

Gross Internal Debt of the Public Sector | | Ps. | 3,861.1 | | | Ps. | 4,408.9 | | | Ps. | 5,049.5 | | | Ps. | 5,639.5 | | | Ps. | 6,182.3 | | | Ps. | 5,629.5 | | | Ps. | 6,327.9 | |

Net Internal Debt of the Public Sector(14) | | Ps. | 3,770.0 | | | Ps. | 4,230.9 | | | Ps. | 4,804.3 | | | Ps. | 5,379.9 | | | Ps. | 6,009.4 | | | Ps. | 5,412.6 | | | Ps. | 5,949.8 | |

Gross Internal Debt of the Federal Government | | Ps. | 3,575.3 | | | Ps. | 4,063.2 | | | Ps. | 4,546.6 | | | Ps. | 5,074.0 | | | Ps. | 5,620.3 | | | Ps. | 5,059.0 | | | Ps. | 5,808.3 | |

Net Internal Debt of the Federal Government | | Ps. | 3,501.1 | | | Ps. | 3,893.9 | | | Ps. | 4,324.1 | | | Ps. | 4,814.1 | | | Ps. | 5,396.3 | | | Ps. | 4,857.6 | | | Ps. | 5,373.8 | |

External Debt(16) | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | |

Gross External Debt of the Public Sector | | $ | 125,726.0 | | | $ | 134,435.9 | | | $ | 147,665.8 | | | $ | 162,209.5 | | | $ | 180,986.0 | | | $ | 179,904.8 | | | $ | 188,441.0 | |

Net External Debt of the Public Sector | | $ | 121,659.0 | | | $ | 130,949.7 | | | $ | 145,617.4 | | | $ | 161,609.5 | | | $ | 177,692.5 | | | $ | 175,386.7 | | | $ | 187,317.9 | |

Gross External Debt of the Federal Government | | $ | 67,460.5 | | | $ | 72,180.4 | | | $ | 78,573.4 | | | $ | 82,588.3 | | | $ | 88,157.0 | | | $ | 90,287.7 | | | $ | 89,471.9 | |

Net External Debt of the Federal Government | | $ | 66,016.5 | | | $ | 69,910.4 | | | $ | 77,352.4 | | | $ | 82,320.3 | | | $ | 86,666.0 | | | $ | 87,904.7 | | | $ | 89,379.3 | |

Interest on external public debt as % of merchandise

exports(4) | | | 1.6 | % | | | 1.6 | % | | | 1.6 | % | | | 1.7 | % | | | 2.1 | % | | | 2.2 | % | | | 2.2 | % |

| Note: | Numbers may not total due to rounding. |

| (1) | Preliminary figures. Note that, in particular, unemployment figures from 2012-2016 and GDP figures from 2012-2016 remain subject to periodic revision. Further, nominal GDP figures for 2016 represent the latest INEGI release of such figures on May 22, 2017. |

| (2) | Annualized. Actual first quarter nominal GDP data has been annualized by multiplying it by four for comparison purposes. First quarter data is not necessarily indicative of performance for the full fiscal year. |

| (3) | Constant pesos with purchasing power as of December 31, 2008. |

| (4) | Merchandise export figures include the maquiladora (or the in-bond industry) and exclude tourism. |

| (5) | Due to the impact of errors and omissions, as well as the purchase, sale and revaluation of bullion, figures for changes in total reserves do not reflect the sum of the current and capital accounts. |

| (6) | “International reserves” are equivalent to gross international reserves minus international liabilities of Banco de México with maturities of less than six months. |

| (7) | “Net international assets” are defined as (a) gross international reserves plus (b) assets with a maturity longer than six months derived from credit agreements with central banks, less (x) liabilities outstanding to the International Monetary Fund (IMF) and (y) liabilities with a maturity of less than six months derived from credit agreements with central banks. |

| (8) | “Representative market rate” represents the end-of-period exchange rate announced by Banco de México for the payment of obligations denominated in currencies other than pesos and payable within Mexico. |

| (9) | Annual average of weekly rates, calculated on a month-by-month basis. |

| (10) | The figures provided for Mexico’s budget for 2017 represent budgetary estimates, based on the economic assumptions contained in the Criterios Generales de Política Económica 2017 (General Economic Policy Guidelines for 2017) and in the Programa Económico 2017 (Economic Program for 2017), and do not reflect actual results for 2017 or updated estimates of Mexico’s 2016 economic results. Percentages of GDP were calculated with a GDP projection made in 2016, using the method of calculation in effect since April 2008. |

| (11) | Includes the Government’s aggregate revenues and expenditures, as well as the aggregate revenues and expenditures of budget-controlled and administratively-controlled agencies (each as defined in “Public Finance–General”). This does not include off-budget revenues or expenditures. |

| (12) | The definition of “public sector balance” is discussed in “Public Finance—General—Methods for Reporting Fiscal Balance.” See this section for further information regarding the calculation of the public sector balance. |

| (13) | Includes the Government’s direct debt, public sector debt guaranteed by the Government and other public sector debt, except as indicated. |

| (14) | The Historical Balance of Public Sector Borrowing Requirements represents net obligations incurred to achieve public policy objectives, both of public institutions and of private entities acting on behalf of the Government. It includes the budgetary public sector debt and obligations of IPAB, of FONADIN, associated with long-term infrastructure-related projects (PIDIREGAS) and the support programs for debtors, as well as the expected gains or losses of development banks and development funds, minus financial assets available, including loans granted and debt amortization funds, as a reflection of the annual trajectory of the Public Sector Borrowing Requirements. |

| (15) | “Net internal debt” represents the internal debt directly incurred by the Government at the end of the period indicated, including Banco de México’s General Account Balance and the assets of the Fondo de Ahorro Para el Retiro (Retirement Savings System Fund). It does not include the debt of budget-controlled and administratively-controlled agencies or any debt guaranteed by the Government. In addition, “net internal debt” is comprised of Cetes and other securities sold to the public in auctions for new issuances (primary auctions), but does not include any debt allocated to Banco de México for its use in Regulación Monetaria (regulating the money supply). This is because Banco de México’s sales of debt pursuant to Regulación Monetaria does not increase the Government’s overall level of internal debt; Banco de México must reimburse the Government for any allocated debt that Banco de México sells in the secondary market and that is presented to the Government for payment. However, if Banco de México carries out a high volume of sales of allocated debt in the secondary market, this can result in the Government’s outstanding internal debt being higher than its outstanding net internal debt. |

| (16) | External debt is presented herein on a “gross” basis and includes the public sector’s external obligations at its full outstanding face or principal amounts at the end of the period indicated. For informational and statistical purposes, Mexico sometimes reports its external public sector debt on a “net” or “economic” basis, which is calculated as gross debt net of certain financial assets held abroad. These financial assets include the value of collateral securing principal and interest on bonds, as well as Mexican public sector external debt that is held by public sector entities but that has not been canceled. “External public sector debt” does not include (a) repurchase obligations of Banco de México with the IMF (none of which were outstanding at March 31, 2017); (b) external borrowings by the public sector after March 31, 2017; and (c) loans from the Commodity Credit Corporation to private sector Mexican banks. |

Source: Ministry of Finance and Public Credit.

D-3

RECENT DEVELOPMENTS

The following information provides a summary of selected recent developments relating to each section of this report since December 31, 2016.

UNITED MEXICAN STATES

Form of Government

On January 4, 2017, Luis Videgaray was appointed as the Secretary of Foreign Affairs of Mexico by President Enrique Peña Nieto. Mr. Videgaray previously served as the Secretary of Finance and Public Credit of the Secretaría de Hacienda y Crédito Público (Ministry of Finance and Public Credit) of Mexico from 2012 to 2016.

On February 5, 2017, the Political Constitution of Mexico City was published in the Diario Oficial de la Federación (Official Gazette of the Federation). It will enter into force on September 17, 2018. See “United Mexican States—Form of Government—State Government” for more information on Mexico City’s statehood.

On June 4, 2017, gubernatorial elections were held in Coahuila, Nayarit and the State of Mexico, and mayoral elections were held in Veracruz. The State of Mexico is politically important due to its size, economic impact and proximity to Mexico City. The gubernatorial election in the State of Mexico was heavily contested. On August 9, 2017, the candidate from the Partido Revolucionario Institucional (Institutional Revolutionary Party, or PRI), Alfredo del Mazo Maza, was confirmed the winner.

The following table provides the distribution as of September 1, 2017 of Congressional seats reflecting certain post-election changes in the party affiliations of certain senators and deputies.

Table No. 1 – Party Representation in Congress

| | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | |

| | | Senate | | | Chamber of Deputies | |

| | | Seats | | | % of Total | | | Seats | | | % of Total | |

Institutional Revolutionary Party | | | 55 | | | | 43.0 | % | | | 197 | | | | 39.4 | % |

National Action Party | | | 38 | | | | 29.7 | | | | 109 | | | | 21.8 | |

Democratic Revolution Party | | | 8 | | | | 6.2 | | | | 54 | | | | 10.8 | |

Ecological Green Party of Mexico | | | 7 | | | | 5.5 | | | | 48 | | | | 9.6 | |

Social Encounter Party | | | 0 | | | | 0 | | | | 9 | | | | 1.8 | |

Labor Party | | | 15 | | | | 11.7 | | | | 0 | | | | 0 | |

Citizen Movement Party | | | 0 | | | | 0 | | | | 21 | | | | 4.2 | |

New Alliance Party | | | 0 | | | | 0 | | | | 12 | | | | 2.4 | |

Unaffiliated | | | 5 | | | | 3.9 | | | | 3 | | | | 0.6 | |

Independent | | | 0 | | | | 0 | | | | 1 | | | | 0.2 | |

| | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | |

National Regeneration Movement (New) | | | 0 | | | | 0 | | | | 46 | | | | 9.2 | |

| | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | |

Total | | | 128 | | | | 100.0 | % | | | 500 | | | | 100.0 | % |

| | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | |

Note: Numbers may not total due to rounding.

Source: Senate and Chamber of Deputies.

Legal and Political Reforms

Local Government Finance

On March 31, 2017, the Reglamento de Sistema de Alertas (Alerts System Regulation) was published in the Official Gazette of the Federation. In furtherance of the objectives listed in the Ley de Disciplina Financiera de las Entidades Federativas y los Municipios (Law for the Financial Discipline of the States and the Municipalities), the purpose of the Alerts System Regulation is to evaluate the level of indebtedness of states so the Government may take the actions listed in the Law for the Financial Discipline of the States and the Municipalities to prevent risky levels of indebtedness. See “United Mexican States—Legal and Political Reforms—Local Government Finance” for more information on the Law for the Financial Discipline of the States and the Municipalities.

D-4

Economic Development

Consistent with the Plan Nacional de Desarrollo 2013-2018 (National Development Plan, or the Plan), on January 9, 2017, the Government announced that it signed the Acuerdo para el Fortalecimiento Económico y la Protección de la Economía Familiar (Agreement for Economic Strengthening and Protection of the Economy of the Family). This agreement aims to strengthen the domestic market in Mexico with a focus on protecting the economic well-being of Mexican families, increasing investment and maintaining job creation, economic growth and competitiveness.

On May 15, 2017, the Disposiciones de Carácter General Aplicables a las Bolsas de Valores (General Provisions Applicable to Stock Exchanges) were published in the Official Gazette of the Federation. These General Provisions strengthen the regulatory framework applicable to stock exchanges, including, among other measures, enhanced internal controls of the stock market, rules covering the disclosure of market-moving information and the establishment of contingency plans for stock exchanges experiencing operational distress.

On August 29, 2017, the concession for a new stock exchange in Mexico was published in the Official Gazette of the Federation by the Ministry of Finance and Public Credit. The new Bolsa Institutional de Valores (Institutional Stock Exchange, or BIVA) will begin operations once it fulfills the requirements set forth in the Ley del Mercado de Valores (Stock Market Exchange Law). This new concession was granted as part of the Ministry of Finance and Public Credit’s program to develop the securities market based on four main pillars: (1) changing the configuration and regulation of securities; (2) providing for the participation of development banks to promote securities markets; (3) changing the regulation of retirement funds and insurance companies to encourage investment in new projects and creating reference portfolios to establish incentives to participate in the securities market; and (4) developing a national strategy for financial education to encourage participation in development instruments.

Internal Security

Following the cyber-attack that affected several countries in Europe, Asia and Latin America on May 12, 2017, the Comisión Nacional de Seguridad (National Security Commission, or CNS) reported that la Policía Federal (the Federal Police) issued guidance with technical recommendations for improved security of federal agencies’ computer equipment. The Collaboration Protocol, an agreement between the CNS and corresponding agencies from other countries, was also activated to manage cybernetic incidents linked to Ransomware software.

In May 2017, responding to increased violence in Mexico against human rights defenders and journalists, the Government announced that it would implement measures that include: (1) the expansion of infrastructure and budgetary resources to protect human rights defenders and journalists; (2) the creation of a national coordination system to identify and reduce the risk of violence, led by representatives of civil society, the Comisión Nacional de los Derechos Humanos (National Commission of Human Rights) and the Government; and (3) an increase of the resources available to the Fiscalía Especial para la Atención de Delitos Cometidos Contra la Libertad de Expresión (Special Prosecutor’s Office for Crimes Against Freedom of Expression) in order to strengthen its ability to conduct and resolve investigations in cases of violence against human rights defenders and journalists.

On June 22, 2017, President Peña Nieto reiterated the Government’s commitment to protect freedom of expression. In line with this commitment, President Peña Nieto ordered the Attorney General’s Office to conduct an investigation into allegations that advanced spyware, known as “Pegasus,” had been used to intrude upon the privacy of journalists, human rights defenders and anti-corruption activists in Mexico.

Environment

Pursuant to Mexico’s 2015 Ley de Transición Energética (Energy Transition Law), on May 31, 2017, the Ministry of Energy announced in the Official Gazette of the Federation the creation of the Programa Especial de la Transición Energética (Special Energy Transition Program) in order to assess and implement clean energy strategies in order to increase the share of clean energy in the energy market to 25% by 2018, 30% by 2021 and 35% by 2024.

D-5

THE ECONOMY

Gross Domestic Product

The following tables set forth Mexico’s real Gross Domestic Product (GDP) and expenditures, in constant 2008 pesos and in percentage terms, for the periods indicated. Quarterly GDP data has been multiplied by four to state on an annualized basis. Quarterly real GDP data for the period presented is not necessarily indicative of performance for the full fiscal year.

Table No. 2 – Real GDP and Expenditures

(In Billions of Pesos)(3)

| | | | | | | | |

| | | Second quarter (annualized) (2) | |

| | | 2016(1) | | | 2017(1) | |

GDP | | | Ps. 14,207.2 | | | | Ps. 14,529.3 | |

Add: Imports of goods and services | | | 4,799.7 | | | | 5,100.7 | |

| | | | | | | | |

Total supply of goods and services | | | 19,006.8 | | | | 19,630.0 | |

Less: Exports of goods and services | | | 4,872.5 | | | | 5,203.6 | |

| | | | | | | | |

Total goods and services available for domestic expenditure | | | Ps. 14,134.4 | | | | Ps. 14,426.4 | |

Allocation of total goods and services: | | | | | | | | |

Private consumption | | | 9,459.4 | | | | 9,759.5 | |

Public consumption | | | 1,552.2 | | | | 1,560.8 | |

| | | | | | | | |

Total consumption | | | 11,011.7 | | | | 11,320.2 | |

| | | | | | | | |

Total gross fixed investment | | | 2,992.6 | | | | 2,955.5 | |

| | | | | | | | |

Changes in inventory | | | 65.9 | | | | 57.0 | |

| | | | | | | | |

Total domestic expenditures | | | Ps. 14,070.2 | | | | Ps. 14,332.8 | |

| | | | | | | | |

Errors and Omissions | | | (64.2 | ) | | | (93.6 | ) |

| | | | | | | | |

| Note: | Numbers may not total due to rounding. |

| (2) | Annualized. Actual second quarter nominal GDP data has been annualized by multiplying it by four for comparison purposes. Second quarter data is not necessarily indicative of performance for the full fiscal year. |

| (3) | Constant pesos with purchasing power as of December 31, 2008. |

Source: INEGI.

D-6

Table No. 3 – Real GDP and Expenditures

(As a Percentage of Total GDP)(3)

| | | | | | | | |

| | | Second quarter (annualized)(2) | |

| | | 2016(1) | | | 2017(1) | |

GDP | | | 100.0 | % | | | 100.0 | % |

Add: Imports of goods and services | | | 33.8 | | | | 35.1 | |

| | | | | | | | |

Total supply of goods and services | | | 133.8 | | | | 135.1 | |

Less: Exports of goods and services | | | 34.3 | | | | 35.8 | |

| | | | | | | | |

Total goods and services available for domestic expenditures | | | 99.5 | % | | | 99.3 | % |

Allocation of total goods and services: | | | | | | | | |

Private consumption | | | 66.6 | % | | | 67.2 | % |

Public consumption | | | 10.9 | | | | 10.7 | |

| | | | | | | | |

Total consumption | | | 77.5 | | | | 77.9 | |

Total gross fixed investment | | | 21.1 | | | | 20.3 | |

Changes in inventory | | | 0.5 | | | | 0.4 | |

| | | | | | | | |

Total domestic expenditures | | | 99.0 | % | | | 98.6 | % |

| | | | | | | | |

Errors and Omissions | | | (0.5 | )% | | | (0.6 | )% |

| Note: | Numbers may not total due to rounding. |

| (2) | Annualized. Actual second quarter nominal GDP data has been annualized by multiplying it by four for comparison purposes. Second quarter data is not necessarily indicative of performance for the full fiscal year. |

| (3) | Constant pesos with purchasing power as of December 31, 2008. |

Source: INEGI.

D-7

The following tables set forth the composition of Mexico’s real GDP by economic sector and percentage change by economic sector, in constant 2008 pesos and in percentage terms, for the periods indicated. Quarterly GDP data has been multiplied by four to state on an annualized basis. Quarterly real GDP data for the period presented is not necessarily indicative of performance for the full fiscal year.

Table No. 4 – Real GDP by Sector

(In Billions of Pesos)(3)

| | | | | | | | |

| | | Second quarter (annualized)(2) | |

| | | 2016(1) | | | 2017(1) | |

Primary Activities: | | | | | | | | |

Agriculture, forestry, fishing, hunting and livestock(4) | | Ps. | 439.6 | | | Ps. | 454.1 | |

Secondary Activities: | | | | | | | | |

Mining | | | 926.5 | | | | 832.7 | |

Utilities | | | 316.5 | | | | 312.9 | |

Construction | | | 1,012.2 | | | | 1,011.5 | |

Manufacturing | | | 2,213.9 | | | | 2,279.9 | |

Tertiary Activities: | | | | | | | | |

Wholesale and retail trade | | | 2,213.9 | | | | 2,279.9 | |

Transportation and warehousing | | | 847.1 | | | | 879.3 | |

Information | | | 512.0 | | | | 543.6 | |

Finance and insurance | | | 671.4 | | | | 736.3 | |

Real estate, rental and leasing | | | 1,705.7 | | | | 1,741.8 | |

Professional, scientific and technical services | | | 320.6 | | | | 338.1 | |

Management of companies and enterprises | | | 85.5 | | | | 89.1 | |

Support for Business | | | 450.7 | | | | 467.0 | |

Education services | | | 492.3 | | | | 498.8 | |

Health care and social assistance | | | 261.1 | | | | 267.9 | |

Arts, entertainment and recreation | | | 59.4 | | | | 61.6 | |

Accommodation and food services | | | 306.6 | | | | 318.8 | |

Other services (except public administration) | | | 296.1 | | | | 300.9 | |

Public administration | | | 508.3 | | | | 510.9 | |

| | | | | | | | |

Gross value added at basic values | | | 13,804.8 | | | | 14,110.3 | |

Taxes on products, net of subsidies | | | 390.9 | | | | 419.1 | |

| | | | | | | | |

GDP | | Ps. | 14,207.2 | | | Ps. | 14,529.3 | |

| | | | | | | | |

| Note: | Numbers may not total due to rounding. |

| (2) | Annualized. Actual second quarter nominal GDP data has been annualized by multiplying it by four for comparison purposes. Second quarter is not necessarily indicative of performance for the full fiscal year. |

| (3) | Based on GDP calculated in constant pesos with purchasing power as of December 31, 2008. |

| (4) | GDP figures relating to agricultural production set forth in this table and elsewhere herein are based on figures for “agricultural years,” with the definition of the relevant “agricultural year” varying from crop to crop based on the season during which it is grown. Calendar year figures are used for the other components of GDP. |

Source: INEGI.

D-8

Table No. 5 – Real GDP Growth by Sector

(Percent Change Against Prior Year)(1)

| | | | |

| | | Second quarter (annualized)(3) |

| | | 2016(2) | | 2017(2) |

GDP (constant 2008 prices) | | 2.4% | | 2.3% |

Primary Activities: | | | | |

Agriculture, forestry, fishing, hunting and livestock(4) | | 1.8 | | 3.3 |

Secondary Activities: | | | | |

Mining | | (4.0) | | (10.1) |

Utilities | | 3.3 | | (1.2) |

Construction | | 2.2 | | (0.1) |

Manufacturing | | 1.1 | | 3.6 |

Tertiary Activities: | | | | |

Wholesale and retail trade | | 3.0 | | 3.0 |

Transportation and warehousing | | 3.1 | | 3.8 |

Information | | 9.1 | | 6.2 |

Finance and insurance | | 7.8 | | 9.7 |

Real estate, rental and leasing | | 2.0 | | 2.1 |

Professional, scientific and technical services | | 7.5 | | 5.5 |

Management of companies and enterprises | | 5.2 | | 4.2 |

Administrative support, waste management and remediation services | | 3.8 | | 3.6 |

Education services | | 1.1 | | 1.3 |

Health care and social assistance | | 0.4 | | 2.6 |

Arts, entertainment and recreation | | 3.2 | | 3.7 |

Accommodation and food services | | 4.6 | | 4.0 |

Other services (except public administration) | | 5.8 | | 1.6 |

Public administration | | (1.7) | | 0.5 |

| Note: | Numbers may not total due to rounding. |

| (1) | Based on GDP calculated in constant pesos with purchasing power as of December 31, 2008. |

| (3) | Annualized. Actual second quarter nominal GDP data has been annualized by multiplying it by four for comparison purposes. Second quarter data is not necessarily indicative of performance for the full fiscal year. |

| (4) | GDP figures relating to agricultural production set forth in this table and elsewhere herein are based on figures for “agricultural years,” with the definition of the relevant “agricultural year” varying from crop to crop based on the season during which it is grown. Calendar year figures are used for the other components of GDP. |

Source: INEGI.

According to preliminary figures, Mexico’s GDP increased by 2.3% in real terms during the first six months of 2017, compared to the same period of 2016. This increase reflects the increase in private consumption and in Mexico’s external demand as a result of a moderate recovery of global economic activity.

Employment and Labor

According to preliminary Tasa de Desocupación Abierta (open unemployment rate) figures, Mexico’s unemployment rate was 3.5% as of August 31, 2017, a 0.2 percentage point increase from the rate registered on December 31, 2016. As of June 30, 2017, the economically active population in Mexico fifteen years of age and older consisted of 54.1 million individuals.

The new minimum wage of Ps. 80.04 per day, as set by the Comisión Nacional de los Salarios Mínimos (National Minimum Wage Commission) on December 19, 2016, went into effect on January 1, 2017 and was applied uniformly across Mexico.

D-9

Principal Sectors of the Economy

Manufacturing

The following table shows the value of industrial manufacturing output in constant 2008 pesos and the percentage of total output accounted for by each manufacturing sector for the periods indicated.

Table No. 6 – Industrial Manufacturing Output by Sector(1)

| | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | |

| | | Second

quarter of

2016(2) | | | Second

quarter of

2017(2) | |

Food | | Ps. | 506.9 | | | | 1.9 | % | | Ps. | 518.1 | | | | 2.2 | % |

Beverage and tobacco products | | | 121.1 | | | | 6.8 | | | | 122.9 | | | | 1.5 | |

Textile mills | | | 16.3 | | | | 0.8 | | | | 16.6 | | | | 1.9 | |

Textile product mills | | | 14.2 | | | | 2.6 | | | | 12.6 | | | | (11.2 | ) |

Apparel | | | 55.0 | | | | 2.2 | | | | 54.7 | | | | (0.5 | ) |

Leather and allied products | | | 18.2 | | | | 0.7 | | | | 17.5 | | | | (4.0 | ) |

Wood products | | | 22.0 | | | | (6.5 | ) | | | 23.3 | | | | 5.9 | |

Paper | | | 49.7 | | | | 4.3 | | | | 50.9 | | | | 2.4 | |

Printing and related support activities | | | 14.5 | | | | (2.1 | ) | | | 14.0 | | | | (3.5 | ) |

Petroleum and coal products | | | 70.3 | | | | (2.0 | ) | | | 61.2 | | | | (13.1 | ) |

Chemicals | | | 241.8 | | | | (1.9 | ) | | | 239.9 | | | | (0.8 | ) |

Plastics and rubber products | | | 73.7 | | | | 4.3 | | | | 77.8 | | | | 5.5 | |

Nonmetallic mineral products | | | 120.6 | | | | 3.3 | | | | 120.9 | | | | 0.2 | |

Primary metals | | | 159.5 | | | | (0.2 | ) | | | 166.0 | | | | 4.0 | |

Fabricated metal products | | | 81.0 | | | | 3.0 | | | | 83.9 | | | | 3.6 | |

Machinery | | | 101.3 | | | | 3.7 | | | | 107.2 | | | | 5.9 | |

Computers and electronic products | | | 111.8 | | | | 7.6 | | | | 120.6 | | | | 7.9 | |

Electrical equipment, appliances and components | | | 73.8 | | | | 2.6 | | | | 76.0 | | | | 2.9 | |

Transportation equipment | | | 447.6 | | | | (2.5 | ) | | | 499.4 | | | | 11.6 | |

Furniture and related products | | | 26.5 | | | | (1.4 | ) | | | 25.4 | | | | (3.9 | ) |

Miscellaneous | | | 53.4 | | | | 4.3 | | | | 55.9 | | | | 4.8 | |

Total expansion/contraction | | Ps. | 2,379.2 | | | | 1.1 | % | | Ps. | 2,464.9 | | | | 3.6 | % |

| (1) | In billions of constant pesos with purchasing power as of December 31, 2008 and percent change against corresponding period of prior year. Percent change reflects differential in constant 2008 pesos. |

Source: INEGI

Petroleum and Petrochemicals

On June 19, 2017, the first bidding session of Round Two of the energy reform process closed, during which fifteen blocks were offered. Petróleos Mexicanos (PEMEX) won bids for two blocks in consortium with international companies. Twenty four blocks were offered in the second and third bidding sessions that occurred on July 12, 2017. The fourth bidding session will offer deep sea blocks and is scheduled for January 2018. See “The Economy – Principal Sectors of the Economy – Petroleum and Petrochemicals” for more information on the energy reform bidding process.

D-10

Following the discovery of new hydrocarbons reserves in the Gulf of Mexico by several private companies, the Ministry of Energy announced on July 16, 2017 that the Government will receive between an 83% and 90% share of the profits of each such company, which includes the base royalty, the Government’s share in the company’s operating income, the exploration and extraction of hydrocarbons tax and the income tax.

As of August 14, 2017, 224 permits have been authorized for the import of gasoline, 324 for the import of diesel, 114 for the import of LP gas and 71 for the import of aviation fuel.

On February 18, 2017, the Ministry of Finance and Public Credit published guidance on how the maximum prices for gasoline and diesel will be determined for each region of the country on a daily basis.

Transportation and Communications

On January 6, 2017, Grupo Aeroportuario de la Ciudad de México, S.A. de C.V, the government enterprise responsible for building, managing and operating a new airport in the Mexico City vicinity (Nuevo Aeropuerto Internacional de la Ciudad de México, or NAICM), announced the award of the contract for the design and operation of the new airport terminal and the start of construction.

In September 2017, NAICM raised a total of U.S.$4 billion in the sale of two tranches of green bonds (bonds created to fund projects that have positive environmental and/or climate benefits) with 10-year and 30-year maturities. See “The Economy & Principal Sectors of the Economy - Principal Sectors of the Economy” for more information on the NAICM and its financing.

On August 16, 2017 the Supreme Court of Mexico declared unconstitutional a law requiring providers of telecommunications services to allow rival companies to use their networks without a fee. The Court ruled that only the Instituto Federal de Telecomunicaciones (Federal Institute of Telecommunications), and not Congress, has the power to determine the interconnection tariffs, even if the amount of the tariff is zero.

FINANCIAL SYSTEM

Monetary Policy, Inflation and Interest Rates

Money Supply and Financial Savings

The following table shows Mexico’s M1 and M4 money supply aggregates at each of the dates indicated. The methodology for the calculation of Mexico’s M1 and M4 money supply is discussed in “Financial System—Monetary Policy, Inflation and Interest Rates—Money Supply and Financial Savings.”

Table No. 7 – Money Supply

| | | | | | | | |

| | | June 30, | |

| | | 2016 | | | 2017(1) | |

| | | (in millions of nominal pesos) | |

M1: | | | | | | | | |

Bills and coins | | | Ps. 1,106,216 | | | | Ps. 1,241,521 | |

Checking deposits | | | | | | | | |

In domestic currency | | | 1,279,568 | | | | 1,443,648 | |

In foreign currency | | | 408,370 | | | | 460,226 | |

Interest-bearing peso deposits | | | 634,078 | | | | 645,083 | |

Savings and loan deposits | | | 15,748 | | | | 18,767 | |

| | | | | | | | |

Total M1 | | | Ps. 3,443,981 | | | | Ps. 3,809,245 | |

| | | | | | | | |

M4 | | | Ps. 14,263,626 | | | | Ps. 15,344,514 | |

Note: Numbers may not total due to rounding.

Source: Banco de México.

D-11

Inflation

Consumer inflation for the first six months of 2017 was 6.3%, which was above the 3.0% (+/- 1.0%) target inflation for the year and 2.9 percentage points higher than the 3.4% consumer inflation for 2016. This was mainly a combined result of the adjustment of energy prices, particularly the liberalization of gasoline prices, exchange rate changes, higher agricultural prices, the increase in the minimum wage and increases in public transport fares.

The following table shows, in percentage terms, the changes in price indices and annual increases in the minimum wage for the periods indicated. For additional information on Mexico’s minimum wage policy, see “The Economy—Employment and Labor.”

Table No. 8 – Rates of Change in Price Indices

| | | | | | | | | | | | |

| | | National Producer

Price Index(1)(2)(3)(4) | | | National Consumer

Price Index(1)(5) | | | Increase in

Minimum Wage | |

2015 | | | 2.7 | | | | 2.9 | | | | 6.9 | |

2016 | | | 2.8 | | | | 5.7 | | | | 6.9 | |

2017 | | | | | | | | | | | 4.2 | |

January | | | 4.7 | | | | 9.8 | | | | 9.6 | |

February | | | 4.9 | | | | 9.5 | | | | — | |

March | | | 5.4 | | | | 9.4 | | | | — | |

April | | | 5.8 | | | | 8.7 | | | | — | |

May | | | 6.2 | | | | 8.1 | | | | — | |

June | | | 6.3 | | | | 6.7 | | | | — | |

July | | | 6.4 | | | | 5.9 | | | | — | |

| (1) | For annual figures, changes in price indices are calculated each December. |

| (2) | National Producer Price Index figures represent the changes in the prices for basic merchandise and services (excluding oil prices). The index is based on a methodology implemented in June 2012. |

| (3) | Preliminary figures for 2016-2017. |

| (4) | National Producer Price Index takes December 2003 as a base date. |

| (5) | National Consumer Price Index takes the second half of December 2010 as a base date. |

Sources: INEGI; Ministry of Labor.

On August 23, 2017, INEGI announced changes, effective in August 2018, to the National Consumer Price Index aimed at better reflecting the consumption patterns of Mexican households. The changes include: (1) actualizing the base year; (2) increasing the number of categories for goods and services; (3) increasing the number of areas represented; and (4) adjusting the weighting of each component. It is expected that the new measurements will generate greater volatility in the National Consumer Price Index.

Interest Rates

Banco de México increased the target for the overnight interbank funding rate by fifty basis points in its decision of February 2017 and by twenty-five basis points in each of its decisions of March 2017, May 2017 and June 2017 reaching a level of 7.0 percent on June 22, 2017. These measures were consistent with the actions taken in 2016 to prevent contamination of the price formation process in the economy, anchor inflation expectations and strengthen the convergence of inflation to its target. See “Financial System—Monetary Policy, Inflation and Interest Rates—Interest Rates” for more information.

D-12

The following table sets forth the average interest rates per annum on 28-day and 91-day interest rate accured on Certificados de la Tesororía de la Federación (Federal Treasury Certificates, or Cetes), the costo porcentual promedio (the average weighted cost of term deposits for commercial banks, or CPP) and the 28-day and 91-day tasa de interés interbancaria de equilibrio (the equilibrium interbank interest rate, or TIIE) for the periods indicated.

Table No. 9 – Average Cetes, CPP and TIIE Rates

| | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | |

| | | 28-Day

Cetes | | | 91-Day

Cetes | | | CPP | | | 28-Day

TIIE | | | 91-Day

TIIE | |

2015: | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | |

January-June | | | 2.9 | | | | 3.0 | | | | 2.2 | | | | 3.3 | | | | 3.3 | |

July-December | | | 3.1 | | | | 3.2 | | | | 2.1 | | | | 3.3 | | | | 3.4 | |

2016: | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | |

January-June | | | 3.6 | | | | 3.8 | | | | 2.4 | | | | 3.9 | | | | 4.0 | |

July-December | | | 4.7 | | | | 4.9 | | | | 2.9 | | | | 5.0 | | | | 5.1 | |

2017: | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | |

January | | | 5.8 | | | | 6.3 | | | | 3.6 | | | | 6.1 | | | | 6.3 | |

February | | | 6.1 | | | | 6.4 | | | | 3.7 | | | | 6.4 | | | | 6.6 | |

March | | | 6.3 | | | | 6.6 | | | | 3.9 | | | | 6.6 | | | | 6.8 | |

April | | | 6.5 | | | | 6.7 | | | | 4.1 | | | | 6.9 | | | | 6.9 | |

May | | | 6.6 | | | | 6.8 | | | | 4.2 | | | | 7.0 | | | | 7.0 | |

June | | | 6.8 | | | | 7.1 | | | | 4.3 | | | | 7.2 | | | | 7.3 | |

July | | | 7.0 | | | | 7.1 | | | | 4.3 | | | | 7.4 | | | | 7.4 | |

Source: Banco de México.

During the first six months of 2017, interest rates on 28-day Cetes averaged 6.4%, as compared to 3.6% during the same period of 2016. Interest rates on 91-day Cetes averaged 6.6%, as compared to 3.8% during the same period of 2016.

On September 28, 2017, the 28-day Cetes rate was 7.0% and the 91-day Cetes rate was 7.1%.

On March 28, 2017, Banco de México transferred its operating surplus for fiscal year 2016 of Ps. 321.7 billion to the Government. In accordance with the Ley Federal de Presupuesto y Responsabilidad Hacendaria (Federal Law of Budget and Fiscal Accountability), the Government must apply 70% of this operating suplus amount, equivalent to Ps. 225.2 billion, to amortize debt or to reduce outstanding indebtedness. On June 29, 2017, the Ministry of Finance and Public Credit announced the repurchase of Ps. 40.0 billion of debt in the local market. The remaining amounts will be used in 2017 to: (1) reduce the outstanding indebtedness the local market by Ps. 5.6 billion pesos and (2) reduce external indebtedness by Ps. 74.5 billion pesos.

Exchange Controls and Foreign Exchange Rates

Foreign Exchange Policy

The U.S. election in November 2016 resulted in pressure on the value of the Mexican peso, which declined through January 2017. Since then, the Mexican peso has recovered a substantial part of its loss in value.

On January 5, 2017 Banco de México sold U.S.$2 billion directly in the foreign exchange market. The purpose of this sale was to provide liquidity and mitigate market volatility, and the Comisión de Cambios (Foreign Exchange Commission) did not rule out the possibility of further sales in the event that present market conditions continue.

On February 21, 2017, the Foreign Exchange Commission announced the implementation of a new foreign exchange market mechanism consisting of non-deliverable forward auctions, which will be settled in Mexican pesos starting on March 6, 2017. The mechanism aims to maintain the local exchange market while supplying market participants with a foreign exchange hedging instrument in order to mitigate exposure to foreign exchange risk. The maximum program size will be U.S.$20 billion.

D-13

The following table sets forth, for the periods indicated, the daily peso/dollar exchange rates announced by Banco de México for the payment of obligations denominated in dollars and payable in pesos within Mexico.

Table No. 10 – Exchange Rates

| | | | | | | | |

| | | Representative Market Rate | |

| | | End-of-Period | | | Average | |

2015 | | | 17.2487 | | | | 15.8680 | |

2016 | | | 20.6194 | | | | 18.6908 | |

2017 | | | | | | | | |

January | | | 20.7908 | | | | 21.3853 | |

February | | | 19.9957 | | | | 20.2905 | |

March | | | 18.7955 | | | | 19.3010 | |

April | | | 18.9594 | | | | 18.7875 | |

May | | | 18.6909 | | | | 18.7557 | |

June | | | 18.0626 | | | | 18.1326 | |

July | | | 17.8646 | | | | 17.8283 | |

Source: Banco de México.

On September 28, 2017, the peso/dollar exchange rate closed at Ps. 18.1790 = U.S.$1.00, an 11.9% appreciation in dollar terms as compared to the rate on December 31, 2016. The peso/U.S. dollar exchange rate announced by Banco de México on September 28, 2017 (which took effect on the second business day thereafter) was Ps. 18.1300 = U.S.$1.00.

Securities Markets

The Bolsa Mexicana de Valores (Mexican Stock Exchange, or BMV) publishes the Índice de Precios y Cotizaciones (Stock Market Index, or the IPC) based on a group of the thirty-five most actively traded shares.

On September 28, 2017, the IPC stood at 50,137 points, representing a 9.9% increase from the level at December 30, 2016.

FOREIGN TRADE AND BALANCE OF PAYMENTS

Foreign Trade

Foreign Relations

On April 7, 2017 the Minister of Foreign Affairs, Luis Videgaray, participated in the Ministerial Meeting between the Ministers of Economy of the Pacific Alliance and El Mercado Común del Sur (MERCOSUR). The meeting allowed the two main regional blocs in Latin America to discuss the prospects for regional integration.

Mexico recently took part in several bilateral meetings with the governments of Spain and China, as well as with the European Union (EU). On April 20, 2017, Mexico and Spain agreed on six new legal instruments covering a range of topics, including air transport regulation, commerce and investment and labor issues. On May 3, 2017, Mexico and China highlighted increases in commerce, investment and air connectivity achieved within the framework of their comprehensive strategic partnership established during President Peña Nieto’s visit to China in June 2013 and agreed to deepen bilateral relations. On July 10, 2017, Mexico and the EU held a round of negotiations aimed at modernizing the existing Economic Partnership, Political Coordination and Cooperation Agreement.

D-14

Following the United Kingdom’s vote to leave the EU, on July 26, 2017 Mexico and the United Kingdom discussed options to continue and strengthen their economic and cooperative relations in the context of Mexico’s trade agenda and the departure of the United Kingdom from the EU.

Foreign Trade Performance

The following table provides information about the value of Mexico’s merchandise exports and imports (excluding tourism) for the periods indicated.

Table No. 11 – Exports and Imports

| | | | | | | | |

| | | First eight

months of

2016 | | | First eight

months of

2017(1) | |

| | | (in millions of dollars,

except average price of

the Mexican crude oil mix ) | |

(Merchandise exports (f.o.b.) | | | | | | | | |

Oil and oil products | | $ | 11,485 | | | $ | 14,342 | |

Crude oil | | | 9,316 | | | | 11,694 | |

Other | | | 2,169 | | | | 2,648 | |

Non-oil products | | | 229,626 | | | | 251,127 | |

Agricultural | | | 9,798 | | | | 10,646 | |

Mining | | | 2,655 | | | | 3,466 | |

Manufactured goods(2) | | | 217,174 | | | | 237,016 | |

| | | | | | | | |

Total merchandise exports | | | 241,112 | | | | 265,470 | |

Merchandise imports (f.o.b.) | | | | | | | | |

Consumer goods | | | 33,200 | | | | 35,974 | |

Intermediate goods(2) | | | 192,771 | | | | 210,045 | |

Capital goods | | | 25,903 | | | | 26,616 | |

| | | | | | | | |

Total merchandise imports | | | 251,874 | | | | 272,635 | |

| | | | | | | | |

Trade balance | | $ | (10,763 | ) | | $ | (7,165 | ) |

| | | | | | | | |

Average price of Mexican oil mix(3) | | $ | 33.07 | | | $ | 43.78 | |

Note: Numbers may not total due to rounding.

| (2) | Includes the in-bond industry. |

| (3) | In U.S. dollars per barrel. |

Source: Banco de México/PEMEX.

Foreign Trade Agreements

Mexico and the EU continue to negotiate to modernize the Free Trade Agreement between Mexico and the EU (the TLCUEM) and aim to conclude negotiations in 2017. On January 20, 2017, Mexico announced the conclusion of the third round of renegotiations. Throughout these discussions, topics included access to goods and services, rules of origin and trade facilitation and barriers. The modernization of TLCUEM is a priority in Mexico’s trade agenda; over the past seventeen years, trade between the EU and Mexico has tripled from $20.8 billion to $61.7 billion.

On January 23, 2017, the U.S. President signed an Executive Order directing the United States Trade Representative to withdraw the United States as a signatory to the Trans-Pacific Partnership Agreement (TPP), a proposed international trade agreement among twelve Pacific Rim countries, and to permanently withdraw the United States from TPP negotiations. Mexico and other parties are evaluating ratification of the TPP without the United States, while also considering alternatives.

D-15

Canada, Mexico and the U.S. are currently engaged in negotiations involving the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA). The first, second and third rounds of negotiations between Canada, Mexico and the U.S. took place in Washington, D.C from August 16 through 20, 2017, in Mexico City from September 1 through 5, 2017, and in Ottawa from September 23 through 27, 2017. The fourth round of negotiations will be held in Washington, D.C. from October 11 through 15, 2017. Changes to NAFTA may greatly affect Mexico’s industries, especially manufacturing and agriculture, but it is difficult to predict the impact of a renegotiated NAFTA on Mexico.

On June 6, 2017, Mexico and the United Stated reached an agreement regarding the exportation of sugar from Mexico to the United States, preventing the imposition of compensatory quotas against sugar exported from Mexico. Mexico also agreed to increase the export of raw sugar by 10 percent.

Balance of Payments and International Reserves

As of the first quarter of 2017, balance of payments statistics will be reported based on the classification criteria of the Sixth Edition of the International Monetary Fund’s (IMF) Manual on Balance of Payments, as updated in November 2013. The modifications and improvements in the measurement of these statistics are aimed at the implementation of international recommendations and standards, which allows for the international comparability of statistics, in addition to providing a greater level of information disaggregation.

D-16

The following table sets forth Mexico’s balance of payments for the periods indicated:

Table No. 12 – Balance of Payments

| | | | | | | | |

| | | Second

quarter of

2016 | | | Second

quarter of

2017(1) | |

| | | | | | | | |

| | | (in millions of dollars) | |

| Current account(2) | | $ | (6,117.3 | ) | | $ | (321.1 | ) |

Credits | | | 108,432.2 | | | | 119,640.0 | |

Merchandise exports (f.o.b.) | | | 93,837.7 | | | | 102,921.0 | |

Non-factor services | | | 6,078.0 | | | | 6,556.6 | |

Transport | | | 463.1 | | | | 443.5 | |

Tourism | | | 4,838.0 | | | | 5,302.9 | |

Insurance and pensions | | | 652.4 | | | | 668.1 | |

Financial Services | | | 41.6 | | | | 78.0 | |

Others | | | 82.9 | | | | 64.1 | |

Primary Income | | | 1,488.7 | | | | 2,787.9 | |

Secondary Income | | | 7,027.8 | | | | 7,374.5 | |

Debits | | | 114,549.4 | | | | 119,961.1 | |

Merchandise imports (f.o.b.) | | | 96,887.7 | | | | 103,053.7 | |

Non-factor services | | | 8,042.2 | | | | 8,797.6 | |

Transport | | | 3,106.7 | | | | 3,538.3 | |

Tourism | | | 2,389.3 | | | | 2,535.3 | |

Insurance and pensions | | | 1,193.2 | | | | 1,262.9 | |

Financial Services | | | 264.0 | | | | 401.2 | |

Others | | | 1,088.9 | | | | 1,059.9 | |

Primary Income | | | 9,444.8 | | | | 7,928.0 | |

Secondary Income | | | 174.8 | | | | 181.7 | |

| Capital account | | | (5.8 | ) | | | (10.3 | ) |

Debit | | | 41.3 | | | | 35.9 | |

Credit | | | 47.1 | | | | 46.3 | |

| Financial account | | | (10,111.7 | ) | | | (8,287.4 | ) |

Direct investment | | | (7,22.3 | ) | | | (3,297.6 | ) |

Portfolio investment | | | (3,625.0 | ) | | | (510.3 | ) |

Financial derivatives | | | (772.1 | ) | | | 985.9 | |

Other investment | | | (4,093.3 | ) | | | (1,479.7 | ) |

Reserve assets | | | (1,389.0 | ) | | | (3,985.8 | ) |

| Errors and omissions | | | (3,988.6 | ) | | | (7,956.0 | ) |

| Note: | Numbers may not total due to rounding. |

| (2) | Current account figures are calculated according to a methodology developed to conform to new international standards under which merchandise exports and merchandise imports include the in-bond industry. |

Source: Bancode México.

Current Account

In the second quarter of 2017, Mexico’s current account registered a deficit of 0.1% of GDP, or U.S.$321.1 million, due to deficits in the balance of goods and services. The deficit in the balance of goods is mainly explained by an increase in merchandise exports, while the deficit in the balance of services is attributable in part to an increase of services exports.

Capital Account

In the second quarter of 2017, Mexico registered a capital account deficit of U.S.$10.3 million.

D-17

Financial Account

In the second quarter of 2017, Mexico registered financial account inflows of 1.5% of GDP, or U.S.$8.3 billion, which was due to a net inflow of foreign direct investment and portfolio investment offset by other investment.

International Reserves and Assets

The following table sets forth Banco de México’s international reserves and net international assets at the end of each period indicated.

Table No. 13 – International Reserves and Net International Assets(3)

| | | | | | | | |

| | | End-of-Period

International Reserves(1)(2) | | | End-of-Period

Net International Assets | |

| | | (in millions of dollars) | |

2016 | | | 176,542 | | | | 178,057 | |

2017(4) | | | | | | | | |

January | | | 174,791 | | | | 176,657 | |

February | | | 175,145 | | | | 181,847 | |

March | | | 174,931 | | | | 178,735 | |

April | | | 175,011 | | | | 176,779 | |

May | | | 175,138 | | | | 177,045 | |

June | | | 174,246 | | | | 175,425 | |

July | | | 173,360 | | | | 175,713 | |

August | | | 173,032 | | | | 174,482 | |

| (1) | Includes gold, Special Drawing Rights (international reserve assets created by the IMF) and foreign exchange holdings. |

| (2) | “International reserves” are equivalent to: (a) gross international reserves, minus (b) international liabilities of Banco de México with maturities of less than six months. |

| (3) | “Net international assets” are defined as: (a) gross international reserves, plus (b) assets with maturities greater than six months derived from credit agreements with central banks, less (x) liabilities outstanding to the IMF and (y) liabilities with maturities of less than six months derived from credit agreements with central banks. |

Source: Banco de México.

D-18

PUBLIC FINANCE

2017 Budget

Selected estimated budget expenditures and preliminary results are set forth in the table below.

Table No. 14 – Budgetary Expenditures; 2017 Expenditure Budget

(In Billions of Pesos)

| | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | |

| | | 2015

Results(1) | | | 2016

Results(1) | | | First six

months of

2017

Results(1) | | | 2017

Budget(2) | |

Health | | | Ps. 121.1 | | | | Ps. 121.8 | | | | Ps. 62.6 | | | | Ps. 121.8 | |

Education | | | 323.1 | | | | 301.5 | | | | 147.4 | | | | 267.7 | |

Housing and community development | | | 29.2 | | | | 26.0 | | | | 7.9 | | | | 16.0 | |

Government debt servicing | | | 322.2 | | | | 370.1 | | | | 214.5 | | | | 416.3 | |

CFE and PEMEX debt servicing | | | 86.0 | | | | 102.9 | | | | 65.1 | | | | 120.4 | |

PEMEX | | | 72.6 | | | | 86.9 | | | | 55.1 | | | | 102.3 | |

CFE | | | 13.5 | | | | 16.0 | | | | 10.0 | | | | 18.1 | |

Other | | | 0.0 | | | | 0.0 | | | | 0.0 | | | | 0.0 | |

The table below sets forth the budgetary results for 2012–2016 and the first six months of 2017. It also sets forth certain assumptions and targets from Mexico’s 2017 Budget.

Table No. 15 - Budgetary Results; 2017 Budget Assumptions and Targets

| | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | |

| | | 2012

Results(1) | | | 2013

Results(1) | | | 2014

Results(1) | | | 2015

Results(1) | | | 2016

Results(1) | | | First six

months

of 2017

Results(1) | | | 2017

Budget(2) | |

Real GDP growth (%) | | | 4.0 | % | | | 1.4 | % | | | 2.3 | % | | | 2.6 | % | | | 2.3 | % | | | 2.3 | % | | | 1.5-2.5 | % |

Increase in the national consumer price index (%) | | | 3.6 | % | | | 4.0 | % | | | 4.1 | % | | | 2.1 | % | | | 3.4 | % | | | 5.4 | % | | | 4.9 | % |

Average export price of Mexican oil mix (U.S.$/barrel) | | $ | 101.96 | | | $ | 98.44 | | | $ | 85.48 | | | $ | 43.12 | | | $ | 35.63 | | | $ | 43.49 | | | $ | 42 | (3) |

Average exchange rate (Ps./$1.00) | | | 13.2 | | | | 12.8 | | | | 13.3 | | | | 15.9 | | | | 18.7 | | | | 19.4 | | | | 19.5 | |

Average rate on 28-day Cetes (%) | | | 4.2 | % | | | 3.8 | % | | | 3.0 | % | | | 3.0 | % | | | 4.2 | % | | | 6.4 | % | | | 6.5 | % |

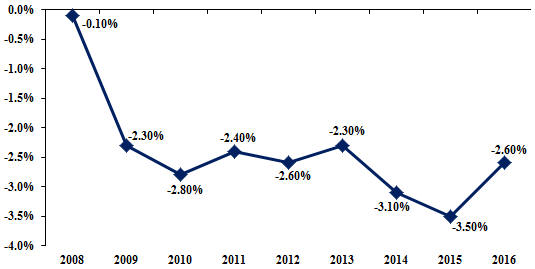

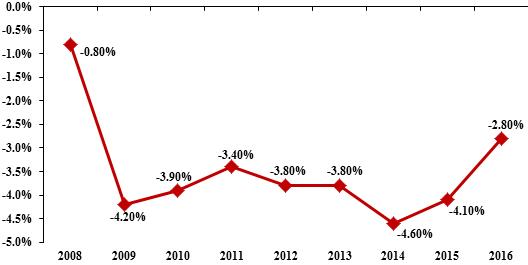

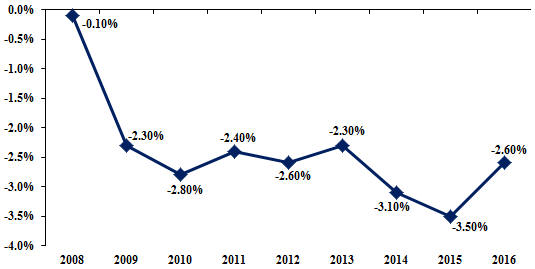

Public sector balance as % of GDP(4) | | | (2.6 | )% | | | (2.3 | )% | | | (3.2 | )% | | | (3.5 | )% | | | (2.6 | )% | | | 0.7 | % | | | (2.4 | )% |

Primary balance as % of GDP(4) | | | (0.6 | )% | | | (0.4 | )% | | | (1.1 | )% | | | (1.2 | )% | | | (0.1 | )% | | | 2.0 | % | | | 0.5 | % |

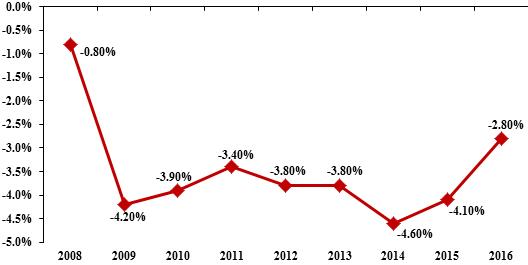

Current account deficit as % of GDP | | | (1.3 | )% | | | (2.4 | )% | | | (1.8 | )% | | | (2.5 | )% | | | (2.2 | )% | | | (0.1 | )% | | | (2.5 | )% |

| (2) | 2017 Budget figures represent budgetary estimates, based on the economic assumptions contained in the General Economic Policy Guidelines and in the Economic Program for 2017. These figures do not reflect actual results for the year or updated estimates of Mexico’s 2017 economic results. |

| (3) | The Government entered into hedging agreements to mitigate the effects of a potential decline in oil prices with respect to the level that was assumed in the 2017 Revenue Law. Therefore, the approved expenditures level should not be affected if the weighted average price of crude oil exported by PEMEX for the year falls below the price assumed in the 2016 Budget. |

| (4) | Includes the effect of expenditures related to the issuance of bonds pursuant to reforms to the ISSSTE Law and the recognition as public sector debt of certain PIDIREGAS obligations, as discussed under “Public Finance—Revenues and Expenditures—General.” |

Source: Ministry of Finance and Public Credit.

D-19

Revenues and Expenditures

The following table presents the composition of public sector budgetary revenues for the first six months of 2016 and 2017 in constant 2008 pesos.

Table No. 16 – Public Sector Budgetary Revenues

(In Billions of Pesos)(3)

| | | | | | | | | | | | |

| | | First six months of

2016(1) | | | First six months of

2017(1) | | | 2017

Budget(2) | |

Budgetary revenues | | | 2,338.9 | | | | 2,655.6 | | | | 4,360.9 | |

Federal government | | | 1,726.1 | | | | 1,896.5 | | | | 3,263.8 | |

Taxes | | | 1,393.1 | | | | 1,468.9 | | | | 2,739.4 | |

Income tax | | | 762.8 | | | | 834.1 | | | | 1,422.7 | |

Value-added tax | | | 374.3 | | | | 400.0 | | | | 797.7 | |

Excise taxes | | | 213.0 | | | | 189.9 | | | | 433.9 | |

Import duties | | | 23.5 | | | | 24.9 | | | | 45.8 | |

Export duties | | | 0.0 | | | | 0.0 | | | | 0.0 | |

Luxury goods and services | | | 0.0 | | | | 0.0 | | | | 0.0 | |

Other | | | 17.7 | | | | 21.3 | | | | 39.3 | |

Non-tax revenue | | | 333.0 | | | | 424.3 | | | | 524.4 | |

Fees and tolls | | | 34.1 | | | | 38.8 | | | | 50.7 | |

Transfers from the Mexican Petroleum Fund for Stabilization and Development | | | 142.1 | | | | 235.2 | | | | 386.9 | |

Rents, interest and proceeds of assets sales | | | 0.0 | | | | 0.0 | | | | 0.0 | |

Fines and surcharges | | | 294.2 | | | | 381.3 | | | | 86.7 | |

Other | | | 4.6 | | | | 4.1 | | | | 0.0 | |

Public enterprises and agencies | | | 470.7 | | | | 527.3 | | | | 1,097.2 | |

PEMEX | | | 172.8 | | | | 182.0 | | | | 400.4 | |

Others | | | 297.9 | | | | 345.3 | | | | 696.7 | |

Note: Numbers may not total due to rounding.

| (2) | Budgetary estimates as of December 2016. Budgetary estimates for 2017 were converted into constant pesos using the GDP deflator for 2017, estimated as of December 2016. |

| (3) | Constant pesos with purchasing power as of December 31, 2008. |

Source: Ministry of Finance and Public Credit.

On January 18, 2017, a decree was published in the Official Gazette of the Federation granting tax incentives to encourage the repatriation of capital held abroad for a period of six months. During the six month period, approximately Ps. 58 billion was transferred into Mexico. On July 17, 2017, a decree was published in the Official Gazette of the Federation providing for a three-month extension of this program.

On June 7, 2017 the Vice Minister of Revenue, Miguel Messmacher Linartas, signed, on behalf of the Government, the Convencion Multilateral para Aplicar las Medidas Relacionadas con los Tratados Fiscales para prevenir la erosion de las bases imponibles y el traslado de beneficios (Multilateral Convention to Implement Measures Related to Tax Treaties designed to prevent base erosion and profit shifting). The Convention’s member states agreed to modify their existing double taxation agreements to allow for the rapid implementation of the tax treaty measures developed as part of the Base Erosion and Profit Shifting Project (BEPS), a framework covering over 100 countries and jurisdictions that aims to curb tax planning strategies that take advantage of gaps in tax rules. The Convention member states will avoid the need to bilaterally renegotiate more than 2,000 treaties worldwide.

On July 31, 2017 the Servicio de Administración Tributaria (Tax Administration Service, or SAT) reported that tax revenues in the first half of 2017 amounted to Ps. 1,472.2 billion, surpassing the amount contemplated in the 2017 Ley de Ingresos (Revenue Law) by Ps. 61 million or 4.3%.

D-20

Financial Stability

On March 30, 2017, the Financial Stability Board (FSB) analyzed the recent evolution of the external and internal environment and reviewed Mexican economic policy and risks in the Mexican financial system. The FSB stated that it would continue to prioritize fiscal discipline and monetary stability, and noted the advantages of diversifying the Mexican public debt portfolio by tenor, currency and sources of funding. The FSB also highlighted the importance of maintaining a dialogue with the United States government following the November 2016 U.S. elections.

PUBLIC DEBT

Historical Balance of Public Sector Borrowing Requirements

The following table sets forth the Historical Balance of Public Sector Borrowing Requirements as a percentage of GDP at each of the dates indicated:

Table No. 17 – Historical Balance of Public Sector Borrowing Requirements

(Percentage of GDP)

| | | | | | | | |

| | | At June 30, 2016 | | | At June 30, 2017(1) | |

Historical Balance of Public Sector Borrowing Requirements(2) | | | 46.9 | % | | | 43.9 | % |

| (1) | Percentage of GDP is calculated using the estimated annual GDP for 2017, consistent with the update of the GDP growth range published by the Ministry of Finance and Public Credit on May 22, 2017. |

| (2) | The Historical Balance of Public Sector Borrowing Requirements represents net obligations incurred to achieve public policy objectives, both of public institutions and of private entities acting on behalf of the Government. It includes the budgetary public sector debt and obligations of IPAB, of FONADIN, associated with long-term infrastructure-related projects (PIDIREGAS) and the support programs for debtors, as well as the expected gains or losses of development banks and development funds, minus financial assets available, including loans granted and debt amortization funds, as a reflection of the annual trajectory of the Public Sector Borrowing Requirements. |

At June 30, 2017, the Historical Balance of Public Sector Borrowing Requirements represented 43.9% of GDP, a decrease of 6.2% from the end of 2016. For an explanation of Mexico’s public debt classification, including the Historical Balance of Public Sector Borrowing Requirements, see “Public Debt—Public Debt Classification.”

Internal Debt

Internal Public Sector Debt

Table No. 18 – Gross and Net Internal Debt of the Public Sector

| | | | | | | | |

| | | At June 30, 2016 | | | At June 30, 2017 | |

Gross Debt | | Ps. | 5,629.5 | | | Ps. | 6,327.9 | |

By Term | | | | | | | | |

Long-term | | | 5,081.9 | | | | 5,798.5 | |

Short-term | | | 547.6 | | | | 529.4 | |

By User | | | | | | | | |

Federal Government | | | 5,059.0 | | | | 5,808.3 | |

State Productive Enterprise (Pemex and CFE) | | | 453.6 | | | | 392.9 | |

Development Banks | | | 117.0 | | | | 126.7 | |

Financial Assets | | | 216.9 | | | | 378.1 | |

Total Net Debt | | | 5,412.6 | | | | 5,949.8 | |

Gross Internal Debt/GDP | | | 29.8 | % | | | 29.8 | % |

Net Internal Debt/GDP(1) | | | 28.6 | % | | | 28.1 | % |

| (1) | “Net internal debt” represents the internal debt directly incurred by the Government at the end of the period indicated, including Banco de México’s General Account Balance and the assets of the Fondo de Ahorro Para el Retiro (Retirement Savings System Fund). It does not include the debt of budget-controlled and administratively-controlled agencies or any debt guaranteed by the Government. In addition, “net internal debt” is comprised of Cetes and other securities sold to the public in auctions for new issuances (primary auctions), but does not include any debt allocated to Banco de México for its use in Regulación Monetaria (regulating the money supply). This is because Banco de México’s sales of debt pursuant to Regulación Monetaria does not increase the Government’s overall level of internal debt; Banco de México must reimburse the Government for any allocated debt that Banco de México sells in the secondary market and that is presented to the Government for payment. However, if Banco de México carries out a high volume of sales of allocated debt in the secondary market, this can result in the Government’s outstanding internal debt being higher than its outstanding net internal debt. |

D-21

Internal Government Debt

On April 28, 2017, the Ministry of Finance and Public Credit presented the reports on the Economic Situation, Public Finances and Public Debt for the first quarter of 2017. The reports highlighted the successful syndicated placement in March 2017 of a Ps.15 billion thirty-year M Bond yielding 7.85% despite challenging market conditions and six swap transactions carried out since the beginning of 2017 that have smoothed the maturity profile of Mexico’s debt and improved price formation in the yield curve, including a transaction in March 2017 in which bonds worth Ps.32.5 billion were exchanged for longer-maturity debt.

Table No. 19 – Gross and Net Internal Debt of the Government(1)

| | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | |

| | | At June30, 2016 | | | At June30, 2017(2) | |

| | | (in billions of pesos, except percentages) | |