Exhibit (a) (7)

FAIR MARKET VALUEOF

THE COMMON STOCKOF

BELK, INC.

ASOF FEBRUARY 1, 2014

April 16, 2014

Mr. Ralph Pitts

Executive Vice President and General Counsel

Belk, Inc.

2801 West Tyvola Road

Charlotte, North Carolina 28217-4500

Dear Mr. Pitts:

Pursuant to your request, we conducted a valuation analysis of the common stock (the “Subject Interest”) of Belk, Inc. (“Belk” or the “Company”) as of February 1, 2014 (the “valuation date”). The results of our analysis are summarized in this introductory transmittal letter and set forth in additional detail in the attached valuation report.

PURPOSEAND OBJECTIVEOFTHE ANALYSIS

The purpose of our analysis is to provide an independent opinion of the fair market value of Belk common stock for management planning purposes, tax compliance purposes, and a potential board of directors (the “Board”) tender offer. Our analysis was conducted for the purposes specified herein. No other purpose is intended nor should be inferred.

The objective of our analysis is to estimate the fair market value of total equity of Belk on a nonmarketable, noncontrolling ownership interest basis as of the valuation date.

STANDARDOF VALUEAND PREMISEOF VALUE

The standard of value used in this analysis isfair market value,as this term is used in the Internal Revenue Code (IRC) and set forth in the Regulations to the IRC. For purposes of this valuation, fair market value is defined as the price at which the Subject Interest would change hands between a hypothetical willing buyer and willing seller, with both having reasonable knowledge of all relevant facts, and neither party being under any compulsion to buy or sell. Fair market value also assumes that the price is paid all in cash or its economic equivalent at closing. The factors surrounding the determination of fair market value are discussed more fully in Internal Revenue Service (IRS) Revenue Ruling 59-60, as amended and amplified by subsequent Revenue Rulings and interpreted by the courts.

Our analysis was conducted under the premise of value in continued use, as a going concern. The going concern premise assumes that Belk will continue to operate as an income producing entity.

Our opinion of value for the Subject Interest is on a nonmarketable, noncontrolling ownership interest basis. A nonmarketable interest cannot be sold in a liquid public market, nor can it be sold quickly, with price certainty, or without incurring relatively significant transaction risks and costs. A noncontrolling interest lacks the relative ability to control an entity’s operating, investing, and financing decisions.

Mr. Ralph Pitts

April 16, 2014

Page 2

BRIEF DESCRIPTIONOF BELK, INC.

Belk, together with its subsidiaries, is the nation’s largest family owned and operated department store business in the U.S., with 299 stores in 16 states, as of the valuation date. With stores located primarily in the southern U.S. and with a growing eCommerce business on its belk.com website, the Company generated revenue of $4.0 billion for the fiscal year 2014. Together with its predecessors, Belk has been successfully operating department stores since 1888. Belk is committed to providing its customers a compelling shopping experience and merchandise that reflects “Modern.Southern.Style.”

VALUATION PROCEDURESAND ANALYSIS

Our analyses, opinions, and conclusions were developed under, and this report was prepared in conformance with, the Uniform Standards of Professional Appraisal Practice, as promulgated by the Appraisal Foundation and endorsed by the American Society of Appraisers.

In developing this valuation analysis, we researched and analyzed the following factors, among others:

| | • | | Economic information and data |

| | • | | Comparative industry data |

| | • | | Information relating to publicly traded companies considered suitable for comparison to Belk |

| | • | | Empirical market evidence regarding historical long-term rates of return on investment measures as developed from nationally recognized investment information publications and studies |

| | • | | Contemporaneous costs of debt capital in the public and private market as provided by nationally recognized investment information publications and our analysis |

We reviewed and analyzed certain information and data provided by Belk, including, but not limited to, audited and unaudited financial information, Company-specific information, and other internal operational documents. This information was both historical and prospective in nature. We relied on this information as fairly presenting the Company’s results of operations and financial position.

We assumed the accuracy and completeness of the financial, operational, and other internal data provided to us, as well as all other publicly available information and data upon which we relied. Information supplied by the Company has been accepted without further verification, unless otherwise noted in our analysis. We have not audited these data as part of our valuation analysis. Therefore, we express no opinion or other form of assurance regarding these data as such work was beyond the scope of our valuation engagement.

Economic, industry, and financial market data were obtained by us from various public and private sources and databases that we deem, but do not guarantee, to be reliable. Data sources are set forth in the text and exhibits of the attached valuation report.

We reviewed and discussed certain documents and information with Belk management as we formed our opinion of fair market value under standard valuation procedures, as they applied to this specific case.

Mr. Ralph Pitts

April 16, 2014

Page 3

We arrived at indications of value through generally accepted valuation approaches. We specifically relied on (1) the discounted cash flow method (an income approach), (2) the guideline publicly traded company method (a market approach), and (3) the previous transactions method (a market approach).

We reached an opinion after considering the historical and prospective operating characteristics of the Company, the risk/expected return investment relationships reflected for guideline companies having securities traded in the public market, capital market, and related industry macroeconomic evidence available as of February 1, 2014, and longer term market pricing evidence, as well as other relevant factors. There were no restrictions or limitations in the scope of our appraisal work or data made available for our analysis.

VALUATION SYNTHESISAND CONCLUSION

Based upon the procedures and analysis mentioned above, and in our independent professional opinion, the fair market value of the Subject Interest on a nonmarketable, noncontrolling ownership interest basis as of February 1, 2014, was:

$1,973,000,000 or $48.10 Per Share

Based on 40,990,916 Shares Issued and Outstanding.

We are independent of Belk, Inc., and we have no current or future financial interest in the assets, properties, or business interests valued. Our fee for this analysis is in no way contingent upon the value conclusions reached.

A narrative valuation report delineating the scope, analysis, and conclusions of this valuation follows this introductory executive summary. Our individual valuation methods and procedures are summarized in the valuation exhibits that are presented following the narrative valuation report. The accompanying statement of assumptions and limiting conditions, certification and representation, and the professional qualifications of the principal analysts are integral parts of this opinion.

Respectfully submitted,

WILLAMETTE MANAGEMENT ASSOCIATES

Curtis R. Kimball, CFA, ASA

Managing Director

FAIR MARKET VALUEOF

THE COMMON STOCKOF

BELK, INC.

ASOF FEBRUARY 1, 2014

TABLEOF CONTENTS

| | | | |

| | | Page | |

| |

I. INTRODUCTION | | | 7 | |

Description of the Assignment | | | 7 | |

Purpose and Objective of the Analysis | | | 7 | |

Standard of Value and Premise of Value | | | 7 | |

Valuation Procedure and Analysis | | | 7 | |

| |

II. U.S. ECONOMIC OUTLOOK | | | 9 | |

General Economic Conditions | | | 9 | |

Fiscal Policy | | | 9 | |

Monetary Policy | | | 10 | |

Consumer Prices and Inflation Rates | | | 10 | |

Employment Growth and Unemployment | | | 10 | |

Interest Rates | | | 11 | |

Consumer Spending | | | 11 | |

Construction | | | 12 | |

The Stock Markets | | | 13 | |

Industrial Production | | | 13 | |

Capital Expenditures | | | 14 | |

Outlook | | | 15 | |

| |

III. DEPARTMENT STORE INDUSTRY OUTLOOK | | | 17 | |

The Department Store Industry in the U.S. | | | 17 | |

Industry Indicators | | | 18 | |

Key External Drivers | | | 18 | |

Products, Operations, and Technology | | | 19 | |

Current Conditions | | | 20 | |

Products and Services Segmentation | | | 21 | |

Major Market Segmentation | | | 21 | |

Critical Issues and Business Challenges | | | 21 | |

Significant Events Affecting the Competitive Landscape | | | 22 | |

Technology and Omnichannel Developments | | | 23 | |

Outlook | | | 24 | |

| |

IV. BELK, INC., OVERVIEW | | | 26 | |

History and Description of Belk, Inc. | | | 26 | |

Strategic Investments | | | 27 | |

Growth Strategy | | | 27 | |

Merchandising | | | 28 | |

Marketing and Branding | | | 29 | |

Omnichannel | | | 29 | |

eCommerce | | | 30 | |

Belk Proprietary Charge Programs | | | 30 | |

FAIR MARKET VALUEOF

THE COMMON STOCKOF

BELK, INC.

ASOF FEBRUARY 1, 2014

TABLEOF CONTENTS

| | | | |

| | | Page | |

Systems and Technology | | | 30 | |

Inventory Management and Logistics | | | 31 | |

Sustainability and Philanthropy | | | 31 | |

Store Locations and Distribution | | | 32 | |

Associates | | | 32 | |

Industry and Competition | | | 32 | |

Legal Proceedings | | | 33 | |

Management’s Discussion and Analysis of Financial Condition and Results | | | 33 | |

Company Management | | | 34 | |

Board of Directors | | | 35 | |

Capitalization and Equity Ownership | | | 38 | |

Tender Offers | | | 39 | |

Dividends | | | 39 | |

Financial Statement Analysis | | | 40 | |

Balance Sheets | | | 40 | |

Income Statements | | | 41 | |

Financial Statement Adjustments | | | 42 | |

Summary of Positive and Negative Factors | | | 42 | |

Positive Factors | | | 42 | |

Negative Factors and Challenges | | | 44 | |

| |

V. IDENTIFICATION OF GUIDELINE PUBLICLY TRADED COMPANIES | | | 47 | |

Overview | | | 47 | |

Descriptions of Selected Guideline Publicly Traded Companies | | | 47 | |

The Bon-Ton Stores, Inc. | | | 47 | |

Dillard’s, Inc. | | | 47 | |

Kohl’s Corporation | | | 48 | |

Macy’s, Inc. | | | 48 | |

Nordstrom, Inc. | | | 48 | |

Target Corporation | | | 48 | |

Stage Stores, Inc. | | | 49 | |

The Gap, Inc. | | | 49 | |

| |

VI. VALUATION ANALYSIS | | | 50 | |

Income Approach | | | 50 | |

Discounted Cash Flow Method | | | 51 | |

DCF Method Calculations | | | 54 | |

The Market Approach | | | 55 | |

The Guideline Publicly Traded Company Method | | | 56 | |

The Previous Transaction Method | | | 57 | |

The Asset-Based Approach | | | 58 | |

FAIR MARKET VALUEOF

THE COMMON STOCKOF

BELK, INC.

ASOF FEBRUARY 1, 2014

TABLEOF CONTENTS

| | | | |

| | | Page | |

VII. VALUATION SYNTHESIS AND CONCLUSION | | | 59 | |

Indicated Equity Value – DCF and GPTC Methods | | | 59 | |

Indicated Equity Value – Previous Transaction Method | | | 59 | |

Synthesis and Conclusion | | | 60 | |

| |

APPENDIX A – VALUATION EXHIBITS | | | 61 | |

| |

APPENDIX B – DISCOUNT FOR LACK OF MARKETABILITY | | | 103 | |

| |

APPENDIX C – STATEMENT OF ASSUMPTIONS AND LIMITING CONDITIONS | | | 127 | |

| |

APPENDIX D – CERTIFICATION AND REPRESENTATION | | | 130 | |

| |

APPENDIX E – PROFESSIONAL QUALIFICATIONS OF PRINCIPAL ANALYSTS | | | 132 | |

I. INTRODUCTION

DESCRIPTIONOFTHE ASSIGNMENT

Willamette Management Associates was retained by Belk, Inc., to provide an independent professional opinion of the fair market value of the common stock (the “Subject Interest”) of Belk, Inc. (“Belk” or the “Company”) as of February 1, 2014 (the “valuation date”). The results of our analysis are set forth in this valuation report.

PURPOSEAND OBJECTIVEOFTHE ANALYSIS

The purpose of our analysis is to provide an independent opinion of the fair market value of Belk common stock for management planning purposes, tax compliance purposes, and a potential board of directors (the “Board”) tender offer. Our analysis was conducted for the purposes specified herein. No other purpose is intended nor should be inferred.

The objective of our analysis is to estimate the fair market value of total equity of Belk on a nonmarketable, noncontrolling ownership interest basis as of the valuation date.

STANDARDOF VALUEAND PREMISEOF VALUE

The standard of value used in this analysis isfair market value,as this term is used in the Internal Revenue Code (IRC) and set forth in the Regulations to the IRC. For purposes of this valuation, fair market value is defined as the price at which the Subject Interest would change hands between a hypothetical willing buyer and willing seller, with both having reasonable knowledge of all relevant facts, and neither party being under any compulsion to buy or sell. Fair market value also assumes that the price is paid all in cash or its economic equivalent at closing. The factors surrounding the determination of fair market value are discussed more fully in Internal Revenue Service (IRS) Revenue Ruling 59-60, as amended and amplified by subsequent Revenue Rulings and interpreted by the courts.

Our analysis was conducted under the premise of value in continued use, as a going concern. The going concern premise assumes that Belk will continue to operate as an income producing entity.

Our opinion of value for the Subject Interest is on a nonmarketable, noncontrolling ownership interest basis. A nonmarketable interest cannot be sold in a liquid public market, nor can it be sold quickly, with price certainty, or without incurring relatively significant transaction risks and costs. A noncontrolling interest lacks the relative ability to control an entity’s operating, investing, and financing decisions.

VALUATION PROCEDUREAND ANALYSIS

Our analyses, opinions, and conclusions were developed under, and this report was prepared in conformance with, the Uniform Standards of Professional Appraisal Practice, as promulgated by the Appraisal Foundation and endorsed by the American Society of Appraisers.

In developing this valuation analysis, we researched and analyzed the following factors, among others:

| | • | | Economic information and data |

| | • | | Comparative industry data |

| | • | | Information relating to publicly traded companies considered suitable for comparison to Belk |

| | • | | Empirical market evidence regarding historical long-term rates of return on investment measures as developed from nationally recognized investment information publications and studies |

| | • | | Contemporaneous costs of debt capital in the public and private market as provided by nationally recognized investment information publications and our analysis |

We reviewed and analyzed certain information and data provided by Belk, including, but not limited to, audited and unaudited financial information, Company-specific information, and other internal operational documents. This information was both historical and prospective in nature. We relied on this information as fairly presenting the Company’s results of operations and financial position.

We assumed the accuracy and completeness of the financial, operational, and other internal data provided to us, as well as all other publicly available information and data upon which we relied. Information supplied by the Company has been accepted without further verification, unless otherwise noted in our analysis. We have not audited these data as part of our valuation analysis. Therefore, we express no opinion or other form of assurance regarding these data as such work was beyond the scope of our valuation engagement.

Economic, industry, and financial market data were obtained by us from various public and private sources and databases that we deem, but do not guarantee, to be reliable. Data sources are set forth in the text and exhibits of the attached valuation report.

We reviewed and discussed certain documents and information with Belk management as we formed our opinion of fair market value under standard valuation procedures, as they applied to this specific case.

We arrived at indications of value through generally accepted valuation approaches. We specifically relied on (1) the discounted cash flow method (an income approach), (2) the guideline publicly traded company method (a market approach), and (3) the previous transactions method (a market approach).

We reached an opinion after considering the historical and prospective operating characteristics of the Company, the risk/expected return investment relationships reflected for guideline companies having securities traded in the public market, capital market, and related industry macroeconomic evidence available as of February 1, 2014, and longer term market pricing evidence, as well as other relevant factors. There were no restrictions or limitations in the scope of our appraisal work or data made available for our analysis.

II. U.S. ECONOMIC OUTLOOK

In the valuation of any business interest, the valuation analyst should consider the general economic outlook as of the valuation date. This premise is based on the belief that the national economic outlook influences how investors perceive alternative investment opportunities at any given time.

In our analysis, we considered the general economic climate that prevailed at the end of the beginning of the first quarter of 2014. This section contains an overview of some selected economic factors, followed by a discussion of those factors that are deemed critical over the long term. The topics addressed include general economic conditions, fiscal policy, monetary policy, consumer prices and inflation rates, employment growth and unemployment, interest rates, consumer spending, construction, the stock markets, industrial production, and capital expenditures.

GENERAL ECONOMIC CONDITIONS

In the fourth quarter of 2013, real gross domestic product (GDP) increased at an annual rate of 3.2 percent in the fourth quarter, according to advance estimates released by the Bureau of Economic Analysis, despite continued federal spending cutbacks. This followed a revised increase of 4.1 percent in the third quarter and an increase of 2.5 percent in the second quarter.

The fourth quarter increase primarily reflected positive contributions from personal consumption expenditures, which increased at their fastest pace in three years. In addition, private inventory investment, nonresidential fixed investment, and exports contributed to the GDP growth. This was partially offset by lower federal government spending and residential fixed investment.

FISCAL POLICY

The federal government budget deficit was $182 billion for the first quarter of the government fiscal year ending September 30, 2014. This was $111 billion less than the deficit for the same period in the prior government fiscal year. Revenue was 8 percent higher than a year ago, while adjusted spending was about 7 percent lower than a year ago.

In the first quarter of the government fiscal year, revenue from individual income and payroll taxes combined decreased by 1.8 percent from the same period of the prior fiscal year. Receipts of corporate income taxes increased by 10.1 percent from same period of the prior fiscal year. Outlays were 6.8 percent lower (on an adjusted basis) from the same period of the prior fiscal year at $846 billion. This amount included $15 billion in spending for unemployment benefits. Outlays for unemployment benefits for the first quarter of the government fiscal year ending September 30, 2014, decreased by 22.1 percent from the same period of the prior fiscal year.

The nation’s trade deficit increased in December 2013 to $38.7 billion, up from $34.6 billion in November. Imports increased to $230.0 billion, and exports decreased to $191.3 billion. For the three months ended in December 2013, exports of goods and services averaged $193.1 billion, while imports averaged $230.6 billion, resulting in an average deficit of $37.4 billion, lower than the November three-month average of $38.8 billion. For the year 2013, the deficit was $471.5 billion, $63.1 billion less than the 2012 deficit.

MONETARY POLICY

At its meeting on December 18, 2013, the Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC) of the Federal Reserve Bank voted to maintain a target range for the federal funds rate of 0 to 0.25 percent. The discount rate charged on direct loans to banks remained at 0.75 percent. The FOMC “sees the improvement in economic activity and labor market conditions . . . consistent with growing underlying strength in the broader economy.” Therefore, the FOMC “decided to modestly reduce the pace of its asset purchases.” Beginning in January, the Federal Reserve will reduce its pace of purchasing agency mortgage-backed securities to $35 billion per month (instead of $40 billion per month) and will reduce its pace of purchasing longer-term Treasury securities to $40 billion per month (instead of $45 billion per month). According to their statement, “Labor market conditions have shown further improvement; the unemployment rate has declined but remains elevated. Household spending and business fixed investment advanced, while the recovery in the housing sector slowed somewhat in recent months. . . . Inflation has been running below the Committee’s longer-run objective, but longer-term inflation expectations have remained stable.”

CONSUMER PRICESAND INFLATION RATES

The Consumer Price Index (CPI) increased 0.3 percent in December 2013, on a seasonally adjusted basis. The CPI was unchanged in November from October. Energy costs increased 2.1 percent, and food costs increased 0.1 percent. The core CPI, which excludes food and energy costs, increased by 0.1 percent in December and by 0.2 percent in November. For the 12 months ended December 31, 2013, the CPI increased by 1.5 percent (not seasonally adjusted). The core CPI increased 1.7 percent over the past 12 months.

The U.S. Import Price Index was unchanged in December 2013, after decreasing 0.9 percent in November. Excluding petroleum, import prices in December 2013 decreased 0.1 percent from November 2013. Petroleum prices increased 0.4 percent in December, but were 1.7 percent lower than a year ago. Export prices increased 0.4 percent in December 2013 after increasing 0.1 percent in November. For the year ended December 31, 2013, import prices were down 1.3 percent, and export prices were down 1.0 percent.

The price index for personal consumption expenditures (PCE) increased 0.2 percent in December 2013, after increasing less than 0.1 percent in November. The core PCE price index (excluding food and energy) increased 0.1 percent in December, following the same increase in November.

EMPLOYMENT GROWTHAND UNEMPLOYMENT

Total nonagricultural employment increased by 74,000 in December 2013. Private sector employment increased by 87,000. Most sectors added jobs in December, led by retail trade, wholesale trade, and professional services.

The unemployment rate decreased in December to 6.7 percent, down from a high of 10 percent in December 2009. The unemployment rate was 1.2 percentage points lower than in December 2012.

Seasonally adjusted average hourly wages increased by $0.02 in December 2013 to $24.17. Average hourly earnings increased 1.8 percent over the year ended December 31, 2012. The average workweek decreased 0.1 hour in December to 34.4 hours.

The Labor Department’s Employment Cost Index (ECI) increased 0.5 percent in the fourth quarter of 2013, on a seasonally adjusted basis. Wages and salaries increased 0.6 percent, and benefits increased 0.6 percent. In the prior quarter, wages and salaries increased 0.3 percent and benefits increased 0.7 percent. For the year ended December 31, 2013, compensation costs increased 2.0 percent. Compensation costs increased by 1.9 percent in the 12 months ended September 30, 2013.

According to the December 2013 personal income and outlays report, personal income increased less than 0.1 percent, and personal spending increased 0.4 percent. In November, personal income increased 0.2 percent, while personal expenditures increased 0.6 percent. Core consumer prices (which exclude food and energy) increased by 0.1 percent in December 2013.

Americans’ personal savings rate (as a percentage of disposable income) was 3.9 percent in December 2013, 0.4 percent lower than in November and lower than in the third quarter of 2013.

Productivity in the nonfarm business sector—the amount of output per hour of work—increased at an annual rate of 3.2 percent in the fourth quarter of 2013. This followed a revised increase of 3.6 percent reported in the third quarter of 2013. From the fourth quarter of 2012 to the fourth quarter of 2013, productivity in the nonfarm business sector increased 1.7 percent.

Unit labor costs in the nonfarm business sector decreased at an annual rate of 1.6 percent in the fourth quarter of 2013, after decreasing a revised 2.0 percent in the third quarter of 2013.

INTEREST RATES

On December 18, 2013, the Federal Reserve maintained the target range for the federal funds rate at between 0 and 0.25 percent. As of December 31, 2013, the prime lending rate remained at 3.25 percent. The prime rate is a benchmark for many consumer and business loans.

CONSUMER SPENDING

Consumer spending increased 0.4 percent in December 2013, after a revised 0.6 percent increase in November. For the fourth quarter of 2013, consumers increased spending by an annual rate of 4.1 percent. This figure was higher than the 3.9 percent increase in the third quarter of 2013. Advance retail sales estimates were higher by 0.2 percent in December 2013 (seasonally adjusted), following a 0.4 percent increase in November. For the quarter ended December 31, 2013, retail sales increased 4.1 percent, on a seasonally adjusted basis, from the same period a year ago.

The largest monthly sales increases were in grocery stores, clothing stores, and gasoline stations (1.9 percent, 1.8 percent, and 1.6 percent, respectively). Gasoline sales have decreased 0.6 percent since December 2012. Sales of automobiles and auto parts have increased 5.9 percent since December 2012. Sales of electronics and appliances have decreased 1.4 percent since December 2012. Sales, excluding automobiles, increased 0.7 percent in December 2013 from November 2013.

Consumer credit outstanding in December 2013 increased at an annual rate of 7.3 percent, or $18.7 billion, to $3.11 trillion, after increasing $12.4 billion in November. Credit card (revolving) debt increased by 7.0 percent, or $5 billion. Nonrevolving debt, such as automobile loans, increased by 7.4 percent, or $13.7 billion. Consumer borrowing does not include mortgages or other loans secured by real estate.

The Conference Board said its Consumer Confidence Index increased 6.1 points in December 2013 to 78.1. The index had decreased in November. A figure between 80.0 and 100.0 suggests slow growth, while a reading below 80.0 indicates a recession (Consumer Confidence Index figures can range from 0 to 160).

The University of Michigan Index of Consumer Sentiment increased in December 2013 to 82.5. The Index of Consumer Expectations also increased in December—to 72.1 from 66.8 in November. “Personal finances, the most critical factor that shapes consumer spending, did slightly improve in December, although largely . . . in the top third of the income distribution,” according to the report.

CONSTRUCTION

Construction spending increased 0.1 percent in December 2013 to a seasonally adjusted annual rate of $930.5 billion. Construction spending has increased 5.3 percent since December 2012. Construction spending in December was higher in some sectors of the construction industry (for example, lodging, commercial, and transportation, to name a few). In other sectors (communication, power, and education, to name a few) spending was lower.

Private construction spending in December 2013 was at a seasonally adjusted annual rate of $663.9 billion, 1.0 percent above the revised November estimate. Residential construction was at a seasonally adjusted annual rate of $352.6 billion, 2.6 percent higher than the revised November estimate. Nonresidential construction was at a seasonally adjusted annual rate of $311.3 billion in December, 0.7 percent below the revised November estimate.

Public construction spending in December 2013 was $266.6 billion, 2.3 percent below the revised November estimate. Educational construction spending was 7.2 percent below the revised November figure, and highway construction was 1.8 percent above the revised November estimate.

For the year ended December 31, 2013, spending on residential construction increased 17.5 percent. New home construction starts decreased 9.8 percent in December 2013 to a seasonally adjusted annual rate of 999,000. The December 2013 figure was 1.6 percent higher than the revised December 2012 rate of 983,000. Single-family housing starts decreased 7.0 percent from November, and multifamily (5 units or more) housing starts decreased 17.9 percent.

The issuance of building permits decreased 3.0 percent in December 2013, to 986,000 units. The rate was 4.6 percent higher than the revised December 2012 rate.

Sales of new single-family homes increased 4.5 percent for the year ended December 31, 2013. In December, sales decreased 7.0 percent to an annual rate of 414,000 units. The November figure was 445,000, lower than the October figure.

The median new home price in December decreased 7.4 percent from November to $311,400. This figure, however, was 4.1 percent above the December 2012 figure. The inventory of new homes for sale in December increased from November to a 5.0-month supply.

In December 2013, sales of existing homes increased by 1.0 percent to a seasonally adjusted annual rate of 4.87 million units. Sales of existing homes in December 2013 were 0.6 percent below December 2012 sales. Sales for all of 2013 were the highest since 2006, at 5.09 million. The median price of an existing home increased 9.9 percent from a year earlier to $198,000. The inventory of unsold existing homes decreased by 9.3 percent from a year ago to 1.86 million units in December 2013, a 4.6-month supply.

The total number of foreclosure filings in December 2013 decreased 26 percent from December 2012. Foreclosures were 53 percent lower than they were at their peak in 2010. Foreclosure filings were reported on approximately 1.4 million properties in 2013, the lowest annual total since 2007.

The nationwide average interest rate for a 30-year fixed rate mortgage for December 2013 was 4.46 percent, compared with 4.26 in November and 3.35 percent in December 2012, according to Freddie Mac. The nationwide average does not include add-on fees known as “points.”

THE STOCK MARKETS

The U.S. stock market indexes had strong growth in the fourth quarter of 2013 and over the year ended December 31, 2013. In fact, the Dow Jones Industrial Average (DJIA) increased by the largest amount in 18 years. For the quarter ended December 31, 2013, the DJIA increased 9.6 percent. For the year ended December 31, 2013, the DJIA increased 26.5 percent. The S&P 500 Index increased 9.9 percent for the quarter and 29.6 percent for the year ended December 31, 2013. The S&P Industrials Index finished the fourth quarter of 2013 with a 10.2 percent increase. For the year ended December 31, 2013, the index increased 29.6 percent. The Nasdaq Composite Index finished higher by 10.7 percent for the quarter. For the year ended December 31, 2013, the Nasdaq increased 38.3 percent.

According to theWall Street Journal, all 10 stock sectors of the S&P 500 Index increased in 2013. The largest increase was in the consumer discretionary sector (40 percent), followed by health care (39 percent) and industrials (37 percent).

The table below presents some historical data for the DJIA, S&P Industrials, S&P 500 Composite, and the Nasdaq Composite Indexes.

| | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | |

| | | 2012 | | | 2013 | |

Index | | 12/28 | | | 3/29 | | | 6/28 | | | 9/27 | | | 12/27 | |

Dow Jones Industrial Average | | | 12,938.11 | | | | 14,578.54 | | | | 14,909.60 | | | | 15,258.24 | | | | 16.478.41 | |

S&P Industrials | | | 1,869.85 | | | | 2,087.28 | | | | 2,124.12 | | | | 2,251.50 | | | | 2,455.95 | |

P/E Multiple | | | 16.45 | | | | 18.50 | | | | 18.82 | | | | 19.80 | | | | 20.91 | |

Dividend Yield | | | 2.33 | | | | 2.15 | | | | 2.22 | | | | 2.12 | | | | 2.00 | |

S&P 500 Composite | | | 1,402.58 | | | | 1,569.19 | | | | 1,606.28 | | | | 1,691.75 | | | | 1,841.40 | |

P/E Multiple | | | 15.95 | | | | 18.14 | | | | 18.57 | | | | 19.29 | | | | 20.25 | |

Dividend Yield | | | 2.33 | | | | 2.16 | | | | 2.21 | | | | 2.12 | | | | 2.04 | |

Nasdaq Composite | | | 2,960.31 | | | | 3,267.52 | | | | 3,403.25 | | | | 3,781.59 | | | | 4,156.59 | |

Sources:Barron’s [12-31-12, 4-1-13, 7-1-13, 9-30-13, and 12-30-13]

INDUSTRIAL PRODUCTION

Industrial output at the nation’s factories, mines, and utilities increased by 0.3 percent in December. In November industrial output increased by 1 percent. For the fourth quarter of 2013 as a whole, total industrial production increased at an annual rate of 6.8 percent, after increasing 2.4 percent in the third quarter of 2013 and 1.2 percent in the second quarter. Manufacturing production increased 0.4 percent in December after a 0.6 percent increase in November. Utility output decreased 1.4 percent, but mining output was up 0.8 percent.

Capacity utilization at factories, mines, and utilities was at 79.2 percent in December 2013, 1.8 percent above its level a year ago. The utilization rate was 1 percentage point below its 1972–2012 average of 80.2 percent.

U.S. factory orders for manufactured goods decreased in December 2013 by 1.5 percent to $489.2 billion. The December decrease followed a 1.5 percent increase in November. Demand for durable goods decreased 4.2 percent in December 2013, following a 2.7 percent increase in November. Durable goods orders have decreased in two of the past three months. Orders for nondurable goods increased 1.1 percent in December after increasing by 0.4 percent in November.

The Institute of Supply Management (ISM) reported its Manufacturing Index registered 57 in December 2013, a 0.3 percent decrease over November. A reading of 50 or more indicates the sector is expanding while a reading below 50 indicates manufacturing activity is contracting.

The ISM Prices Index for manufacturing materials was 53.5 in December 2013, up from 52.5 in November. This indicates that prices are increasing at a faster pace. The ISM Prices Index measures inflationary pressures in the manufacturing sector.

The ISM Nonmanufacturing Index registered 53 in December 2013. The reading decreased from 53.9 recorded in November. This reading indicates slower growth in the nonmanufacturing sector. A number above 50.0 indicates expansion; less than 50.0 indicates contraction.

The Prices Index for the nonmanufacturing sector increased to 55.1 in December 2013 from 52.2 in November, which reflects a faster increase in prices.

The U.S. Labor Department’s Producer Price Index (PPI) for finished goods decreased 0.4 percent in December 2013 on a seasonally adjusted basis, following a decrease of 0.1 percent in November. For the year ended December 31, 2013, the PPI increased 1.2 percent, the smallest annual increase since 2008. Food prices decreased 0.6 percent, while energy prices increased 1.6 percent. Excluding food and energy prices, the index increased 0.3 percent in December.

In November 2013 manufacturers’ and trade inventories were 0.4 percent higher than in October, at a level of $1,699.9 billion. The total inventories-to-sales ratio was 1.29 in November 2013, the same as the November 2012 ratio.

CAPITAL EXPENDITURES

Real nonresidential fixed investment increased 3.8 percent in the fourth quarter of 2013, following a revised 4.8 percent increase in the third quarter of 2013.

Businesses increased their spending on equipment by 6.9 percent in the fourth quarter of 2013, after increasing spending by a revised 0.2 percent in the third quarter of 2013. Businesses increased their spending on intellectual property products by 3.2 percent in the fourth quarter of 2013, after increasing spending by 5.8 percent in the third quarter of the year.

Business investment in commercial structures decreased 1.2 percent in the fourth quarter of 2013, following an increase of 4.8 percent in the third quarter of 2013.

OUTLOOK

Most economists are predicting continued moderate economic growth in the near-term. The economists at Standard & Poor’s expect U.S. GDP growth of around 2.6 percent in 2014, mainly coming from the private sector. The private sector is expected to increase by 3.1 percent in 2014. They state that the chances of another recession in 2014 are about 15 to 20 percent, and the chances of a quick recovery are also around 15 to 20 percent.

The Livingston Survey forecasters have lowered their estimates for GDP growth in 2014 to 2.5 percent for the first half of 2014 and 2.8 percent for the second half. They expect the unemployment rate to be 7 percent by June 2014 and 6.7 percent by December 2014. Inflation (measured by the CPI) is expected to be about 1.8 percent in 2014.

The Kiplinger Letter expects GDP growth of 2.6 percent in 2014. It expects the unemployment rate to approach 6.5 percent by the end of the year. Inflation is expected to be about 1.8 percent in 2014.

Value Line expects GDP growth to “edge back toward 3% by the end of 2014 (from 2.0%–2.5% early on in the new year), as inventories are worked off.” They expect growth of more than 3 percent, on average, in 2015.

The Federal Reserve adjusted their central tendency estimate for U.S. GDP growth to a range of 2.8 to 3.2 percent for 2014. They estimate growth of 3.0 to 3.4 percent in 2015. The Federal Reserve expects the unemployment rate to be between 6.3 to 6.6 percent in 2014. In 2015, they expect it to decrease to 5.8 to 6.1 percent.

The National Association for Business Economists (NABE) panelists forecast “the pace of economic growth to accelerate in both 2013 and 2014.” The panel forecasts GDP growth of 2.8 percent in 2014.

According to the National Association of Home Builders (NAHB), “builder confidence in the market for newly built, single-family homes improved four points to a 58 reading on the National Association of Home Builders/Wells Fargo Housing Market Index (HMI).” NAHB chairman Rick Judson stated, “This is definitely an encouraging sign as we move into 2014. . . . We continue to look for a gradual improvement in the housing recovery in the year ahead.”

Standard & Poor’s states, “We also expect another boost from the housing sector in 2014, with existing home sales climbing about 6.4% next year and new home sales jumping a healthy 26.7%. Since each single-family home built adds two to three jobs to the economy, that’s good news.”

Business investment is expected accelerate to a 7.4 percent rate in 2014 (compared to 2.6 percent in 2013), according to Standard & Poor’s. They expect consumer spending to increase by 2.5 percent in 2014.

According to theLivingston Survey, the S&P 500 will reach 1,841.1 by the end of June 2014 and 1,875.0 by the end of the year. The medianValue Line estimate for the DJIA in 2014 is 15,265.

Sources: Congressional Budget Office, “Monthly Budget Review for December 2013,” January 8, 2014; U.S. Bureau of Economic Analysis, “Gross Domestic Product: Fourth Quarter 2013 (Advance Estimate),” January 30, 2014; U.S. Bureau of Economic Analysis, “Personal Income and Outlays: December 2013,” January 31, 2014; U.S. Census Bureau and U.S. Bureau of Economic Analysis, “U.S. International Trade in Goods and Services: December 2013,” February 6, 2014; Bureau of Labor Statistics, “U.S. Import and Export Price Indexes—December 2013,”

January 14, 2014; Bureau of Labor Statistics, “The Employment Situation—December 2013,” January 10, 2014; Bureau of Labor Statistics, “Employment Cost Index—December 2013,” January 31, 2014; Bureau of Labor Statistics, “Consumer Price Index—December 2013,” January 16, 2014; Bureau of Labor Statistics, “Productivity and Costs: Fourth Quarter 2013, Preliminary,” February 6, 2014; Bureau of Labor Statistics, “Producer Price Index—December 2013,” January 15, 2014; U.S. Census Bureau News, “Advance Monthly Sales for Retail and Food Services: December 2013,” January 14, 2014; U.S. Census Bureau News, “December 2013 Construction at $930.5 Billion Annual Rate,” February 3, 2014; U.S. Census Bureau News, “New Residential Construction in December 2013,” January 17, 2014; U.S. Census Bureau News, “New Residential Sales in December 2013,” January 27, 2014; “December Existing-Home Sales Rise, 2013 Strongest in Seven Years,” National Association of Realtors press release, January 23, 2014; Freddie Mac, “30-Year Fixed-Rate Mortgages Since 1971”; “1.4 Million U.S. Properties with Foreclosure Filings in 2013 Down 26 Percent to Lowest Annual Total Since 2007,” RealtyTrac press release, January 13, 2014; U.S. Census Bureau News, “Full Report on Manufacturers’ Shipments, Inventories and Orders: December 2013,” February 4, 2014; U.S. Census Bureau News, “Manufacturing and Trade Inventories and Sales: November 2013,” January 14, 2014; Federal Reserve Statistical Release, “Consumer Credit: December 2013,” February 7, 2014; Federal Reserve Statistical Release, “Industrial Production and Capacity Utilization,” January 17, 2014; Federal Reserve press release, December 18, 2013; “Economic Projections of Federal Reserve Board Members and Federal Reserve Presidents, December 2013,” December 18, 2013; Conference Board press release, December 31, 2013; Reuters/University of Michigan Surveys of Consumers, December 23, 2013;Barron’s, “Market Laboratory,” December 30, 2013; Institute for Supply Management, “December 2013 Manufacturing ISM Report on Business,” January 2, 2014; Institute for Supply Management, “December 2013 Non-Manufacturing ISM Report on Business,” January 6, 2014; Bloomberg; National Association of Home Builders press release, December 17, 2013;The Kiplinger Letter, January 3, 2014;Value Line Investment Survey: Selection & Opinion, December 27, 2013, and January 3, 2014; National Association for Business Economists,NABE Outlook, December 2013; Matt Jarzemsky, “U.S. Stocks Close Year with Broad Gains,Wall Street Journal, December 31, 2013; Dan Strumpf, “All 10 Stock Sectors Post Gains in Big Year,”Wall Street Journal, December 31, 2013; Shobhana Chandra, “Consumer Spending Propelled U.S. Fourth-Quarter Growth: Economy,” Bloomberg, January 30, 2014; Federal Reserve Bank of Philadelphia,The Livingston Survey, December 12, 2013; and Standard & Poor’s,Industry Surveys: Trends & Projections, December 2013.

III. DEPARTMENT STORE INDUSTRY OUTLOOK

In the valuation process, the state of the industry in which Belk operates must be considered. The analyst must have an understanding of the factors that drive the industry. The following is an overview of the department store industry in the United States.

THE DEPARTMENT STORE INDUSTRYINTHE U.S.

Operators in the department store industry are large scale department stores which retail a broad range of general merchandise, such as apparel, jewelry, cosmetics, home furnishings, general household products, toys, appliance, and sporting goods. Discount department stores, which are also included in this industry, retail similar lines of goods and services but at lower prices. Supercenters that offer fresh groceries in their stores, and warehouse clubs that operate under membership programs, are not included in this industry classification. Further, the primary role of this industry is in retailing a general line of merchandise. Major products and services in this industry include children’s wear, drugs and cosmetics, footwear, furniture and household appliances, men’s wear, toys and hobbies, and women’s wear.

IBISWorld estimates that the industry is comprised of 68 businesses within the United States with estimated 2013 revenue of $198.0 billion dollars and profits of around $9.5 billion. Over the past five years from 2008 to 2013, the industry generated an average annualized decline in revenue of 1.2 percent. Market share in the U.S. is dominated by five large companies: Wal-Mart Stores Inc. (25.2 percent market share); Target Corp. (24.0 percent market share); Sears Holdings Corporation (16.7 percent market share); Macy’s, Inc. (14.3 percent market share); and J. C. Penney Company, Inc. (5.1 percent market share). Furthermore, the department stores industry is highly competitive with moderate regulations, low revenue volatility, low industry globalization, medium barriers to entry, and a declining life cycle stage. The largest concentrations of firms in the U.S. reside in California (10.9 percent), Florida (6.4 percent), Texas (6.1 percent), Illinois (5.1 percent), Pennsylvania (5.0 percent), and New York (4.7 percent).

According to IBISWorld, the department store industry has weathered adverse conditions in the five years to 2013, with revenue expected to decline at an average annual rate of 1.2 percent to $198.0 billion by 2013. Weak consumer confidence and low disposable income led households to curtail discretionary purchases during the recession, resulting in a substantial decline in demand at traditional department stores. Furthermore, in recent years, online retailers have emerged as a threat to industry players and poached customers by offering convenience and low prices. Notwithstanding these adverse conditions, industry profit is expected to increase to an estimated 4.8 percent of revenue in 2013 from 2.9 percent of revenue in 2008. Profit margins increased during this five-year time period despite an average annual decline in revenue due to a shift in sales mix to higher margin products and due to conservative expense management. Improved stability of economic conditions in 2013 should, according to IBISWorld, lead to a 2.2 percent increase in industry revenue in 2014.

Over the past five years, the conversion of discount department stores into big-box retailers (i.e., warehouse clubs and supercenters) has been responsible for much of the industry’s changes in market share. Discount giants, such as Walmart and Target, have been retrofitting stores with fresh grocery sections to increase their market share. Due to this competitive pressure, some operators have been forced out of the industry or have consolidated and merged with larger players. According to the U.S. Census Bureau, the number of stores declined to 68 in 2013 from 71 in 2008.

INDUSTRY INDICATORS

| | • | | According to First Research, U.S. consumer spending on nondurable goods, an indicator of department store sales, increased 0.2 percent in December 2013 over December 2012. |

| | • | | According to U.S. Census Bureau News, retail trade sales decreased in January 2014 by 0.4 percent from December 2013, but increased 2.6 percent in January 2014 over January 2013. |

| | • | | IBISWorld, in its November 2013 report “Department Stores in the U.S.,” projects industry revenue to increase 2.2 percent and 0.9 percent in 2013 and 2014, respectively. |

| | • | | S&P Capital IQ, in its December 2013 report “Industry Surveys/Retailing: General,” projects that 2013 total retail sales growth will have increased by approximately 4 percent in 2013. Retail sales had been up about 4.3 percent through October 2013; however, the federal government shutdown in October crimped demand during the remainder of the year. Online retail sales were much higher than total retail sales during this time period, increasing 10.4 percent. Conversely, through October 2013, department store sales were down 5.1 percent over the same period in 2012. |

| | • | | S&P Capital IQ, in its December 2013 report “Industry Surveys/Retailing: General,” observed that consumer spending patterns shifted as the economy improved in 2013. Consumers shifted more discretionary spending toward big-ticket items such as vehicles and away from smaller ticket items such as apparel. |

| | • | | The S&P Department Stores Index for stock prices increased 19.5 percent year-to-date to November 15, 2013, underperforming the S&P 500, which posted a 26.6 percent increase. |

| | • | | Among indicators of retail demand, Standard & Poor’s Economics, as of October 2013, projected real U.S. GDP to increase 1.6 percent in 2013 and 2.5 percent in 2014. Standard & Poor’s Economics projected nominal disposable personal income to increase 1.8 percent in 2013 and 4.7 percent in 2014. |

KEY EXTERNAL DRIVERS

| | • | | Department stores rely heavily on the financial health of its customer base, including per capita disposable income. During the periods of low disposable income growth, consumers cut back on spending by delaying purchases or substituting costlier goods with inferior products. This was the result of the unemployment rate and the general economic environment. Because disposable income tends to be correlated with economy activity, disposable income is expected to increase in 2014, creating a potential opportunity for the industry to recover margins and sales. |

| | • | | Department stores compete with a wide array of other industries due to the range of products and services they provide. Some of the industry’s largest competitors are big-box retail stores and supercenters, which offer similar products and services. Online retailers also pose significant competition to the industry with the increase in eCommerce. eCommerce allows customers to purchase products any time of day with convenience and access to a diversified database of reviews and options. According to IBISWorld, this driver is expected to increase in 2014, representing a potential threat to the industry. |

| | • | | Consumer confidence levels influence the volume and frequency of consumer purchases. Low consumer confidence causes consumers to delay purchases or buy cheaper alternatives. In contrast, purchases increase as consumer confidence rebounds and sentiments change to less uncertain expectations of the future of the U.S. economy (i.e., consumers anticipate lower unemployment, increased wealth, and higher disposable incomes). This trend is expected to increase in 2014, showing improvement. |

| | • | | Population growth is an important component of industry growth. As the population increases, so does the industry’s customer base. Additionally, population growth in specific regions is an important indicator of future establishment growth because the number of stores is generally dependent on geographical area populations. This driver is expected to increase slowly in 2014. |

PRODUCTS, OPERATIONS,AND TECHNOLOGY

Major products of the department store industry include apparel, drugs and cosmetics, furniture and appliances, and toys. Apparel includes women’s, men’s, and children’s clothing. Cosmetics include makeup, skin care, hair care, and fragrances. Appliances include refrigerators, stoves, washers, dryers, and dishwashers. Companies may also sell kitchenware, bedding, towels, and sheets. Services include gift wrapping, delivery, appliance installation, and personal shopping.

National and regional chains dominate the industry. Store formats and merchandise selection depends on a company’s target market. Some companies lease space to independent companies to sell products requiring sales expertise, such as furs, designer handbags, and high-end cosmetics. Effective store layouts and eye-catching merchandise displays can generate complementary sales and impulse purchases. Companies may also have outlets to help sell excess inventory.

Most department stores are anchor tenants in large malls, and a store’s presence is expected to drive traffic to the mall. Companies consider demographics, population density, and lifestyle when selecting business locations. A typical Sears store averages 133,000 square feet, but some companies have flagship stores that can exceed 250,000 square feet.

Because department stores deal with tens of thousands of stock keeping units (SKUs), effective supply chain management is critical to keeping costs low and supporting timely merchandising flow. Companies have extensive networks of warehouses and distribution centers to route products from suppliers to stores. Cross-docking facilities allow companies to unload and reallocate products in a single operation, minimizing storage costs. Dedicated distribution centers and call centers often support internet and catalog sales as well.

Department stores buy inventory from manufacturers, importers, and distributors, and may work with thousands of suppliers. While long-term supplier relationships are common, few companies have long-term contracts. Lead times can be long: buyers may place orders six to nine months in advance for apparel and shoes and three to six months in advance for handbags and jewelry.

Further, a large percentage of department stores merchandise is imported. Over 90 percent of apparel and footwear sold in the U.S. is imported from Mexico and China. Low-cost production has forced the majority of apparel and show manufacturing offshore. Buyers make purchasing decisions based on trends and historical sales, and may take preferences and climate into account. Companies may receive allowances from suppliers for markdowns and advertising.

Technology is very important to the industry. Information systems to manage functional areas, including sales, merchandising, purchasing, inventory control, distribution, finance, and accounting are key elements. Point-of-sale (POS) systems record sales transactions and process credit card orders. Merchandise planning systems help companies forecast demand and allocate merchandise across states. Inventory management systems monitor inventory levels and trigger replenishment orders. Electronic data

interchanges (EDI) allows companies to process purchase orders more efficiently. While most department stores use bar codes to identify and track products through the supply chain process, some companies are using radio frequency identification devices (RFIDs) to monitor merchandise movement.

CURRENT CONDITIONS

The department store industry has exhibited mixed performance trends in the five years to 2014; while some department stores have flourished, others have floundered. Operators in this industry are segmented into two distinct types: up-market department stores and their discount variety counterparts. Like most retail stores, traditional department stores have suffered from declining demand and rising competition, which reduced sales and hurt profitability. On the other hand, discount department stores gained market share and thrived during the recession because consumers focused more on savings and lower-price points than luxury and high-end goods. Overall, industry revenue is expected to have declined at an average annualized rate of 1.2 percent over the five years to 2013. However, according to IBISWorld, industry revenue is expected to increase by 2.2 percent in 2013 as disposable income improves.

The linchpin for improved conditions in 2013 was the recovery of the housing market, which began at the end of 2012. Retail spending may have been higher had there not been a reprise of the debt ceiling impasse at the end of 2012, followed by the sequester and the government shutdown in the fall of 2013 which caused consumer confidence to decrease by nine points. The silver lining for this, and for prior severe declines in consumer confidence due to government policy, is that consumer confidence rebounded quickly once a temporary resolution was meted out.

In the December 2013 S&P Capital IQIndustry Surveys/Retailing: General, while some of the department stores beat same-store sales estimates for the first half of fiscal 2014 (ended January 2014), some fell short of estimates. It was observed that middle-income consumers were cautious with expenditures due to higher taxes and a beleaguered, unpredictable job market. This resulted in a weak performance for middle-income focused department stores like Kohl’s, but a strong performance by discounters such as Dollar Tree, Dollar General, and Family Dollar. Another factor during 2013 was the weather. March 2013 was the coldest March in the prior 17 years in the United States. S&P believes that the unseasonably cold spring crimped demand for spring clothing, and was a factor in Fred’s and Target posting negative year-over-year same-store sales during the first fiscal quarter ending April. In the latter half of the year, record snowfall and wintery weather along the east coast limited an already shorter shopping season as compared to calendar year 2012. In the fourth quarter, for many department store companies, the shopping season was six days fewer and wintery weather along the east coast further eliminated three days, lowering sales opportunities.

As of late November 2013, Standard & Poor’s held a neutral outlook for department stores. Through October 2013, department store sales had declined 5.1 percent over the same period in 2012, according to the U.S. Census Bureau. Headwinds during 2013 included (1) the ending of the payroll tax holiday; (2) difficult year-over-year comparisons due to an unseasonably warm, early spring in 2012; and (3) increased competition from specialty apparel and home retailers. Standard & Poor’s estimates that there is a lag of about a year between a meaningful increase in consumer wealth and increased spending, which is known as the “wealth effect.” According to Cassidy Turley’s2014 Retail Forecast, the economist Matteo Iacoviello found that for every $1.00 increase in housing wealth, the consumer spends an incremental $0.06. Economists at Wells Fargo have found the spending increase to be closer to $0.09. In the past, it was commonly held by economists that the spending increase was typically $0.05. One reason for the increase may be due to consumer retrenchment over many years and the purchasing of items long postponed. Another reason may be the relativity of security. Consumers have been pessimistic for so long that any incremental improvement in economic conditions has a more profound effect on consumer spending than it had during periods of gradual improvement from less severe recessions.

Products and Services Segmentation

The products and services offered by department stores are primarily centered on their target customer: women of the household. Therefore, the products and services are segmented accordingly:

| | • | | Women’s Wear (21.1 percent) |

| | • | | Furniture and Household Appliances (16.5 percent) |

| | • | | Drugs and Cosmetics (15.5 percent) |

| | • | | Other Categories (12.6 percent) |

| | • | | Children’s Wear (11.4 percent) |

| | • | | Men’s Wear (10.2 percent) |

| | • | | Toys and Hobbies (8 percent) |

Major Market Segmentation

The market segmentation of customers at department stores is fairly equal among ages, as follows:

| | • | | Consumers aged 25-40 (35 percent) |

| | • | | Consumers aged 41-65 (30 percent) |

| | • | | Consumers aged under 25 (20 percent) |

| | • | | Consumers aged over 66 (15 percent) |

Critical Issues and Business Challenges

| | • | | Companies face intense competition from a wide variety of retailers: discount department stores, warehouse clubs, and specialty stores. Discount department stores have drawn sales away from traditional department stores over the past five years. Warehouse stores sell basic items at rock-bottom prices, and specialty retailers provide better selections and service within particular categories. Further, private label apparel from all types of retailers has challenged department stores. |

| | • | | Consumer spending drives department stores sales, in which a large percentage of products sold are discretionary items. During adverse economic conditions, consumers may curtail overall spending or shop at less expensive retailers. |

| | • | | Demand continues to hinge partly on fashion trends. Fashion trends and fads can change quickly, leaving companies with inventory overhang. Failure to predict trends and react quickly can result in unplanned markdowns or lost sales due to errors in forecasting. Stocking dated merchandise can undermine a company’s reputation, if it causes shoppers to perceive the company as being anachronistic. |

| | • | | Companies in this industry rely on economies of scale, particularly in purchasing, distribution, and marketing, to keep costs low and remain profitable. Large companies can benefit from volume purchasing and shared resources among locations. Scale advantages have resulted in industry consolidation and the demise of many small and mid-sized department stores. |

| | • | | Foreign manufacturers produce the majority of the apparel and footwear offered by department stores. Political unrest or trade disputes, economic instability, unfavorable exchange rates, and transportation delays can affect merchandise availability and impinge on seasonal sales. These factors present operational challenges in light of the long lead time to delivery. |

| | • | | Highly seasonal trends, in which the fourth quarter generates the most significant sales and profits for the industry due to winter shopping, present a challenge for working capital management. Cash flow ebbs in the quarters leading up to the fourth quarter and peaks during the first quarter when collections are made from the peak fourth quarter. Leading up to the peak selling season in the fourth quarter, companies must build inventory, hire additional staff, and increase advertising. Accurate sales forecasting is crucial, since most holiday purchasing orders are made months in advance. |

| | • | | High workforce turnover is a result of the low wages paid for such service sector jobs. Companies must consistently hire and train new workers, which can be time-consuming and costly. A constantly changing sales staff can result in poor customer service and inconsistencies with the customer experience. |

Significant Events Affecting the Competitive Landscape

| | • | | New Management at J. C. Penney – In fiscal 2013 ended January 2013, new CEO Ron Johnson initiated a multiyear transformational program to improve sale volumes and address fierce competition from Kohl’s and Macy’s. Central to this strategy is presenting a more engaging,brand-centric specialty department store format with a revamped pricing and merchandising strategy. |

The pricing strategy, whose moniker is “fair and square,” includes three types of prices: everyday, month-long, and best. The everyday prices were lowered by 40 percent; however, coupons were eliminated and promotional activity was cut back. The result was that same-store sales fell 20 percent, as customers failed to recognize that the cessation of discount coupons was offset by already reduced prices. In response, on August 1, 2012, the company instituted two types of prices: every day and clearance. In October 2012 the company restored the discount coupon promotion.

The revamped merchandising strategy involves reducing the number of brands sold to 100 by fiscal year end 2016 from over 400 brands in fiscal 2012, and reducing the percentage of private label brands to 25 percent of sales from 55 percent of sales in 2012.

Due to the disappointing same-store sales following the commencement of this new strategy, Ron Johnson was replaced by Mike Ullman, their prior chairman and CEO from 2004-2011. One of his first moves was to restore weekly promotions, couponing, and door-busters. He also restored private label brands which had been popular among regular customers. According to S&P Capital IQ’s industry survey of December 2013, these actions had an immediate, positive effect on apparel sales.

Losing about $500 million in business during fiscal 2013 took its toll on the capital structure. Despite the company restructuring, the 7.125 percent notes due 2023 and concluding the second quarter of 2014 with approximately $1.5 billion in cash and $1.9 billion in total liquidity, the company announced on September 27, 2013, that it was lowering its forecast for year-end liquidity to $1.3 billion, and conducting a public equity offering worth $810 million. On the day of that announcement, the stock price fell 13 percent and approximately an additional 15 percent between September 30 and October 7, 2013.

| | • | | “Fast Fashion” Initiatives – Fast fashion refers to affordable, fast turnover clothing lines that dovetail off high-end fashion trends. The target market for fast fashion is teenage girls and young women who shop at “fast fashion” chains such as H&M, Topshop, Zara, Uniqlo, and Forever 21. In 2011, Macy’s introduced a series of designer capsule collections for its Impulse contemporary departments, and in 2012, the company announced plans to launch 13 new brands and to expand 11 existing brands aimed at the millennial generation. Target has catered to this niche since 2006, offering limited-edition contemporary apparel by international designers for its “Target Designer Collaborations” and “GO International” campaigns. Target launched its 400-item Missoni collection in September 2011 and the Jason Wu collection in 2012. Kohl’s entered the fast fashion market in 2011 with its Jennifer Lopez and Marc Anthony collections, which include premium denim, apparel, shoes, and accessories. In 2012, Kohl’s launched the Princess Vera Wang collection, a line of children’s apparel. Nordstrom partnered with Topshop in 2012, stocking Topshop apparel and accessories in 42 of 127 locations. Topshop is one of the more prominent “fast fashion” chains. |

| | • | | Sears Attempts to Gain Higher ROI from its Real Estate – Sears, ironically acquired for its real estate by way of junior debt purchases and subsequent chapter 11 plan, has been attempting to rectify its square footage under-utilization by offering space for lease to other retailers. In September 2011, Sears offered space in nearly 4,000 Sears and Kmart stores. It has leased space, for example, to “fast fashion” retailer Forever 21, Whole Foods Market, Western Athletic Clubs, and Gonzalez Grocery. |

Technology and Omnichannel Developments

To provide customers more flexibility with how, when, and from where they shop, department stores and discounters are seeking new, innovative ways to engage and serve their customers.

Mobile technology affords retailers an opportunity to tailor marketing messages and shopping experiences for customers. Nordstrom added Wi-Fi functionality to all of its full-line stores in 2010, and in 2011 tested 6,000 mobile POS devices during its Anniversary Sale in July. Nordstrom also introduced a mobile-optimized version of its website in June 2011 so that it can capitalize on the growing trend of customers shopping through their smartphones.

J. C. Penney, Kohl’s, Kmart, Sears, Saks Fifth Avenue, Macy’s, and Target have all developed applications for the iPhone that allow iPhone users to borrow weekly sales circulars, receive coupons, search for and receive directions to nearby stores, create shopping lists, and/or make online purchases.

Macy’s and Target are also supporting the new Shopkick app (developed by Shopkick Inc.) in stores within select metro markets, including Chicago, Los Angeles, and New York. Just by walking into a participating store with their iPhones or Android phones, customers can earn points called “kickbucks” that are redeemable for music downloads; gift cards at Macy’s, Target, and other Shopkick partner stores; magazine subscriptions; iPods; charitable donations; and other rewards. They also receive exclusive offers while in the store.

Macy’s mobile marketing campaign, called Macy’s Backstage Pass, makes use of Quick Response (QR) bar code technology to engage in-store shoppers. Macy’s Backstage Pass delivers 30-second videos of designers and fashion experts (including Tommy Hilfiger, Michael Kors, Martha Stewart, and Rachel Ray) telling stories about their inspiration as well as fashion tips and advice. Shoppers access the videos by scanning any Macy’s Backstage Pass code using a mobile device camera running a QR reader application. Shoppers can also access the videos through MMS by texting a keyword found beside each Backstage Pass to MACYS, as well as online at www.macys.com/findyourmagic.

Nordstrom has been an early adopter of mobile checkout technology. In June 2011, the company purchased 6,000 mobile POS devices for its full-line stores as part of an effort to provide an enhanced shopping experience to its customers. Nordstrom has so far achieved 75 percent of its fixed POS capability on mobile devices in its full-line stores and is trying to achieve 100 percent capability on mobile POS devices by the end of 2013. As of September 2012, the company had on an average 15 mobile POS devices for each of its Rack stores.

Neiman Marcus is also focusing on becoming an “Omnichannel” company, namely one that provides its customers with the “O2O” (Offline to Online) brand experience. To this end, the company is currently testing the iPhone-only NM Service app in four of its stores. This app alerts the customer of in-store events, sales, and new product arrivals, and enables sales associates to make product suggestions based on the customer’s purchase history and wish list.

OUTLOOK

In its2014 Retail Forecast, Cassidy Turley observes that while encouraging signs of vitality are manifest among high-end consumers, the middle class remains frugal but is gradually spending more, and will continue to gain confidence provided that the housing market continues to recover. The frugality of the middle class has negatively impacted sales of mid-priced items. At the other end of the spectrum, discounters and dollar stores continue to expand aggressively. The top five national chains have averaged 2,000 new units for the past three years and have similar growth plans for 2014. Costco plans at least 28 new stores over the next six months. Marshall’s, TJ Maxx, Ross Dress for Less, and Nordstrom Rack plan to continue aggressive expansion if possible in 2014, contingent on the availability of mid-box space, which is becoming harder to find.

While certain retailers, such as the discounters, have been expanding in terms of number of stores, others have striven to fend off the threat of online sales. Kohl’s, which had been expanding at a rate of 60 stores per year, has put new stores on hold and instead endeavored to build out its eCommerce and supply chain platform.

First Research forecasts that U.S. department store revenue will decline by 1.0 percent per year between 2014 and 2018. Conversely, IBISWorld forecasts that the department store industry will generate annual revenue growth of 1.0 percent from 2013 to 2018, driven in part by expected annual increases in consumer confidence and per capital disposable income of 5.2 percent and 2.4 percent, respectively. Profit margins are expected to increase to about 6.2 percent of revenue in 2018 from 4.8 percent of revenue in 2013. However, competition from online retailers is expected to continue to pressure pricing by industry participants. IBISWorld projects that industry consolidation will continue; the number of participants is forecast to decline at an annual rate of 3.5 percent in the five years to 2018, to about 57 operators.

Sources:Department Stores in the US, IBISWorld, November 2013;Industry Profile: Department Stores, First Research, December 16, 2013;Industry Surveys, Retailing: General, S&P Capital IQ, December 2013;Advance Monthly Sales for Retail and Food Services, U.S. Census Bureau News, January 2014; Cassidy Turley,2014 Retail Forecast; Macy’s Form 10-K for fiscal year ended February 2, 2013; Kohl’s Corporation Form 10-K for fiscal year ended February 2, 2013; Dillard’s Inc. Form 10-K for fiscal year end February 2, 2013; Belk management interview commentary; Belk internal documents.

IV. BELK, INC., OVERVIEW

HISTORYAND DESCRIPTIONOF BELK, INC.1

Belk began when 26-year-old William Henry Belk opened a small bargain store in Monroe, North Carolina, on May 29, 1888. The store measured only 22 by 70 feet, totaling about 1,500 square feet. Mr. Belk named the store the New York Racket, as he thought it made the store sound large and would attract more business. Mr. Belk started with $750 in savings, a $500 loan at 10 percent interest rate from a local widow, and approximately $3,000 worth of goods taken on consignment from a bankrupt store. In less than seven months, he had paid off his debts and netted a $3,300 profit.

Mr. Belk introduced some radically new retailing ideas in his time. He bought large quantities of goods for cash and sold for cash at a low mark-up. Further, all merchandise was clearly marked with its retail price and, therefore, no haggling ensued and customers could return any merchandise purchased if they were not completely satisfied. These innovative ideas helped Belk stores succeed and grow.

In 1891, William Henry Belk persuaded his brother, Dr. John Belk, to leave his medical profession and become a partner in the Monroe store, beginning a remarkable 37-year business association. The company became the Belk Brothers Company.

The brothers opened a second store in 1893 in Chester, South Carolina, and a third store in 1894 in Union, South Carolina. In 1895, William Henry Belk left the Monroe store to open the company’s fourth store in Charlotte, North Carolina. Dr. John Belk continued to manage the Monroe store until his death in 1928. William Henry Belk headed the Belk stores until his death at age 89 in 1952.

The second generation of management of the company was led by two sons of William Henry Belk: Thomas M. Belk and John M. Belk. Thomas M. Belk passed away in 1997. John M. Belk retired as chief executive officer in 2004, but remained director emeritus until his death in 2007.

At the present, Belk is privately owned and operated under a third generation of Belk family leadership. Thomas M. (Tim) Belk Jr. as chairman of the board and chief executive officer and John R. (Johnny) Belk as president and chief operating officer. H. W. McKay Belk is a board member.

The descendants of founder William Henry Belk and his brother, Dr. John M. Belk, own the majority of the company’s stock. The remainder of the stock is mostly held by current and former employees of the company and their descendants. Belk had a policy of providing minority ownership interests to key store employees over the decades as the company expanded. Historically, Belk was composed of a number of separately formed operating companies representing a store or a cluster of stores often using a trade name which included the local manager, such as “Hudson-Belk Stores.” In May 1998, Belk, Inc., was formed by merging all of these operating companies into a single corporate entity.

The Company completed an acquisition of 22 Proffitt’s stores and 25 McRae’s stores from Saks Incorporated effective July 3, 2005. The Proffitt’s and McRae’s stores were regional department stores located in 11 of the 14 Southeastern states in which Belk had operations.

| 1 | Information was obtained from www.belk.com, Belk documents, Belk management interviews, and Web searches conducted by Willamette Management Associates staff during 2012 and 2013. |

In the summer of 2006, Belk purchased the assets of Migerobe, Inc. (an independent company which had been operating jewelry counters within Belk stores) and began operating its own fine jewelry departments.

In October 2006, Belk completed a purchase transaction with Saks Incorporated for the acquisition of certain Parisian department stores located throughout nine Southeastern and Midwestern states. Belk paid $285 million in cash for Parisian, which included real and personal property, operating leases, and inventory of 38 Parisian stores. Parisian generated total revenue of approximately $723 million in 2005.

In the third quarter of fiscal year ended on January 29, 2011, Belk launched a re-branding program, adopting a new mission and vision. The mission is “to satisfy the modern Southern lifestyle like no one else, so that our customers get the fashion they desire and the value they deserve.” The vision is “for the modern Southern woman to count on Belk first. For her, for her family, for life.” Belk is committed to providing its customers a compelling shopping experience and merchandise that reflects “Modern.Southern.Style.”

As of the fiscal year ended February 1, 2014, the Company operated 299 retail department stores in 16 states, primarily in the southern United States. The Company generated $4.0 billion in revenue for the fiscal year 2014. Belk stores seek to provide customers the convenience of one-stop shopping, with an appealing merchandise mix and extensive offerings of brands, styles, assortments, and sizes.

The Company’s fiscal year is a 52- or 53-week period ending on the Saturday closest to each January 31. Fiscal years ended (FYE) 2014, 2013, and 2012 ended on February 1, 2014; February 2, 2013; and January 28, 2012, respectively. The Company was incorporated in Delaware in 1997. The Company’s principal executive offices are located at 2801 West Tyvola Road, Charlotte, North Carolina 28217-4500.

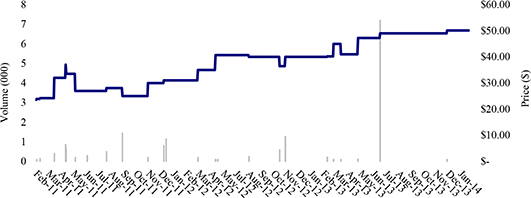

STRATEGIC INVESTMENTS