October 3, 2013

Karl Hiller

Branch Chief

U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission

Division of Corporate Finance

Washington, D.C. 20549-7010

Gentlemen:

We have received your letter of September 26, 2013 wherein you have provided to us your comments and questions related to:

Magellan Midstream Partners, L.P.

Form 10-K for the Fiscal Year ended December 31, 2012

Filed February 22, 2013

Response Letter dated August 27, 2013

File No. 1-16335

The purpose of this correspondence is to provide our response to your comments and questions related to the above-noted filings. Before we get into our detailed response we acknowledge:

| |

| • | We are responsible for the adequacy and accuracy of the disclosures in our filings; |

| |

| • | That staff comments or changes to disclosures in response to staff comments do not foreclose the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission from taking any action with respect to our filing; and |

| |

| • | That we may not assert staff comments as a defense in any proceedings initiated by the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission or any person under the federal securities laws of the United States. |

For ease of reference, we have repeated your questions / comments in our response.

Karl Hiller

Branch Chief

U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission

October 3, 2013

Form 10-K for the Fiscal Year ended December 31, 2012

General

| |

| 1. | We understand that you would prefer to limit compliance with our prior comments to future filings and will consider your request. |

Response: We appreciate the staff’s willingness to consider our request.

Management’s Discussion and Analysis, page 35

Non-GAAP Measures, page 43

| |

| 2. | We note your response to prior comment one, explaining that your derivative related adjustments are intended to align the value of your NYMEX future contracts with the “physical value” of your product when it is purchased or sold, “…as if those commodity derivatives had qualified for hedge accounting treatment.” However, you also state that you believe it is not practical to reconcile your adjustments with the details provided in Note 6 and Note 12 to your financial statements. Please address the following points. |

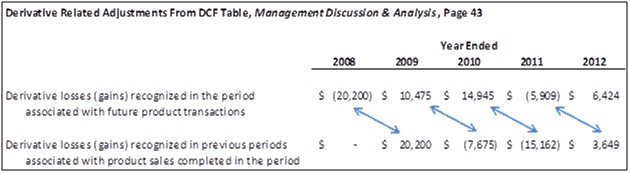

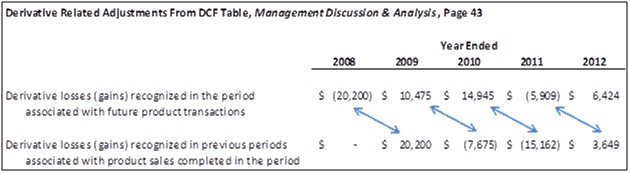

Response: Prior to answering your specific questions, we would like to clarify our prior response. The adjustments we make to our Distributable Cash Flow (“DCF”) for derivatives are comprised of two items: (1) adjustments to defer derivative gains and losses recognized in the current period that hedge physical inventory that has not yet been sold and (2) adjustments to “realize” derivative gains and losses that were already recognized in previous periods that relate to physical inventory sold during the current period. In the table below, you can see the trend where deferrals in one year are, for the most part, reversed in the next year’s DCF adjustment. The table follows ($ ‘000):

Our previous response that it was not practical to reconcile our adjustments with the details provided in Note 6 and Note 12 was specifically a response to the second line in the DCF adjustments referenced above, which relates to adding back prior year recognized amounts. In some cases, these items might originate from derivative hedges entered into more than one or two years prior to the current year, and as such cannot be tied specifically to the footnotes which are related to current period activity. However, we can reconcile the first line of the table above to Footnote 3 and 12 and have done so in the following response.

Karl Hiller

Branch Chief

U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission

October 3, 2013

| |

| (a) | Explain why these adjustments would not equate with the periodic change you report for all derivative assets and liabilities net of the adjustments in equity pertaining to your accounting for hedges; and would not also equate with the amounts you report on page 79 as “Energy commodity derivative contracts, net of derivative deposits” which are utilized in your reconciliation of net income to operating cash flows. |

Response: These adjustments are a component of the periodic change we report for all derivative assets and liabilities. A reconciliation demonstrating this can be found in our reconciliation under (b) below.

| |

| (b) | Submit analyses and schedules that reconcile your “commodity-related” adjustments to the changes in the aforementioned balance sheet accounts, based on the details in Note 12 to your financial statement and the corresponding disclosures in prior year reports, also which reconciles these adjustments to the amounts you report on page 79. Please identify and explain the reasons for the variances in these comparisons. |

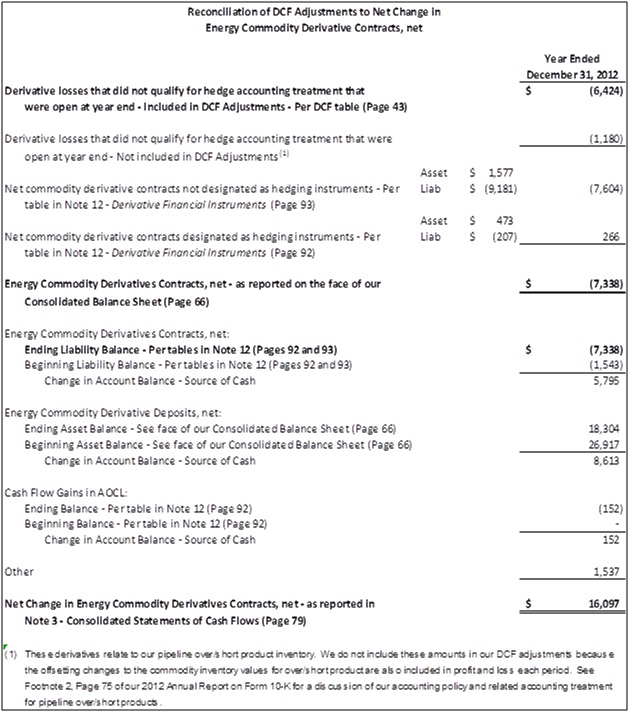

Response: We believe the following table provides the reconciliations you are requesting. As mentioned in our response above, our derivative related commodity DCF adjustments are comprised of two components: (1) derivative losses (gains) recognized in the period associated with future product transactions and (2) derivative losses (gains) recognized in previous periods associated with product sales completed in the period. Because the adjustments in item (1) above relate to a future period, one would expect to see an asset or liability representing those open derivative contracts at the end of the reporting period. The following table shows how the adjustments identified in item (1) reconcile to the balance sheet items identified in Footnote 12, and how those amounts reconcile to the net change in Energy Commodity Derivative Contracts identified in Footnote 3, ($ in ‘000):

Karl Hiller

Branch Chief

U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission

October 3, 2013

Karl Hiller

Branch Chief

U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission

October 3, 2013

| |

| (c) | Tell us why you describe your effort in compiling your various “commodity-related” adjustments as aligning value of future contracts with the “physical value” of products, rather than the cash flows associated with the derivative instruments on the dates of settlement. |

Response: Our use of the phrase “physical value” may be somewhat imprecise, and we apologize for any confusion that may have caused; but we intended by “physical value” to mean the value of the physical product for which those contracts serve as hedges. Our point more generally was that our commodity adjustments are intended to align the value of our futures contracts that do not qualify for hedge accounting with the value of the products for which those futures contracts serve as hedges, as if those derivatives had qualified for hedge accounting treatment. As we described, the fact that they do not qualify for hedge accounting means that our hedges and the product hedged are not currently aligned in our financial statements: pursuant to GAAP, we recognize any change in fair value of those derivative agreements in our income statement in each period, regardless of whether or not the physical product those derivatives are intended to hedge has been sold, while at the same time we do not recognize any change in the value of the underlying product until the date that product is physically sold. In order to align the change in the value of the derivative with the change in value of the underlying physical product in our calculation of DCF, we essentially defer changes in value of those derivatives contracts that do not qualify for hedge accounting until the date of the physical product sale, at which time the change in value of the derivative and the change in value of the underlying product offset each other as intended (except for any hedge ineffectiveness).

The reason we adjust DCF to align the value of futures contracts with the value of the physical product for which those contracts serve as hedges, rather than with the cash flows associated with the derivative instruments on the dates of settlement, is because we intend our DCF calculation to reflect the cash generation performance of our assets during the period, not simply fluctuations in cash flows during the period. We discuss this further below, in response to question 5; but a brief example may illustrate the distinction:

Assume we buy butane in June, with the intention of blending that butane in December to make finished gasoline that we will sell in December. In December, we will earn the margin between the purchase price of butane and the sales price of the finished gasoline (minus our operating costs to perform the blending), so between the time we purchase the butane and sell the gasoline, we are exposed to changes in the price of gasoline. To hedge against this risk and lock in that margin, we sell a futures contract for December gasoline at the time that we purchase the butane. We are now short December gasoline as a result of our futures contract, which hedges the long position in gasoline we will have in December after blending the butane with gasoline.

Assume further that this hedge does not qualify for hedge accounting treatment (because the futures contract is for New York harbor gasoline, while our December gasoline sale

Karl Hiller

Branch Chief

U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission

October 3, 2013

will be in the midcontinent (e.g., Tulsa), which results in enough ineffectiveness to disallow hedge accounting treatment). As a result, changes in the value of our futures contract as a result of changes in the forward price of gasoline will be reflected in our periodic earnings, while of course we will recognize no change in the value of the product until it is ultimately sold in December.

Assume the forward (to December) price of gasoline falls $10/barrel in September (for simplicity, assume the value of our butane inventory remains unchanged). Our income statement for the three-month period ending September 30 will include a $10/barrel gain on our futures contract. Since our calculation of DCF begins with net income, our DCF for the period will also reflect this $10/barrel gain, even though we have not actually blended and sold the butane during the period. Our cash flows will also reflect the increase, as our margin account will be credited with the margin posted by others who are long the contract that we shorted.

Now assume further that the price of December gasoline remains unchanged until December, at which time we blend our butane and sell the resulting gasoline. At the same time we terminate the futures contract. Our income statement for the three-month period ending December 31 will reflect product sales that are lower by $10/barrel (as compared to the forward to December price at the time we purchased the butane and entered the hedge in June). Since the futures contract did not change in value between September and the point at which it was terminated in December, no change in value for that contract will be reflected in our income statement for the three-month period ending December 31. Therefore, the net effect will be a decrease in our net income, and in our DCF, for that period. Our cash flows will also be lower for the three-month period ending December 31, as there will be no change in the margin money we had at the end of September related to the futures contract, while our lower product sales will result in lower net income and lower cash from operations.

If we intended DCF to be used as a liquidity measure that reflected change in cash flows during a period, the situation described above would not require adjustment. However, we intend DCF to be used to measure the ultimate net cash generation performance of our assets during a period, irrespective of any working capital fluctuations; and in this scenario, all of the cash related to the blending activity was ultimately generated by our blending and sale of product in December. For the purposes of calculating DCF, then, the impact of the futures contract on our income statement must be deferred until the period when the related product is sold. We accomplish this by making a negative $10/bbl adjustment to DCF for the three-month period ending September 30, essentially to defer the gain on the futures contract included in our income statement for that period until the three-month period ending December 31, at which time we make an adjustment to add back that gain to our DCF calculation for that period. The adjustment to add back to DCF that gain on the hedge effectively cancels out the lower sales price realized on the physical sale of the blended gasoline in December, with the result that the net realized profit during the period is the price we locked in when we put the hedge on in June (again ignoring any ineffectiveness).

Karl Hiller

Branch Chief

U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission

October 3, 2013

As a result of our adjustments, then, DCF for the three-month period ending September 30 will show no impact of the sale that will occur in December, while the DCF for the three-month period ending December 31 will reflect the net performance of our blending program, as realized by the sale of physical product during the period, net of the impact of related hedging. It is that net performance for activity during the period when the product is sold that we will base our distribution recommendations on, not the fluctuations reflected in net income and cash flows between periods leading up to the ultimate sale and termination of the hedge.

| |

| 3. | We understand from your response to prior comment one that you do not utilize options in your economic hedging program and have therefore not incurred any option premiums in any period. However, you state that all costs from your hedging program are reflected as cash outflows in your Distributable Cash Flow amounts. Please describe the nature of these costs and the circumstances under which they are incurred, quantify the amounts that have been expended and recovered each period, and explain how these are reflected in your accounting and the adjustments utilized in your non-GAAP presentation. |

Response: We apologize for any confusion our earlier response may have caused you. We incur no direct costs associated with our derivative program, other than the losses we incur related to the derivative instruments themselves.

| |

| 4. | Tell us why you believe the components of the “commodity-related” adjustments that are identified as “Lower-of-cost-or-market adjustments and “Houston-to-El Paso cost of sales adjustments” on page 43 are appropriately added to net income in computing non-GAAP measures that are presented in a historical context. Please describe your calculations in detail and clarify the extent to which these adjustments are based on hypothetical circumstances, as appear to be in described in footnote (5) to your table, or derived from your historical accounting records. |

Response:

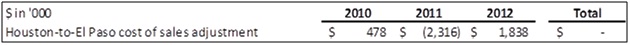

Houston-to-El Paso Adjustment

The Houston-to-El Paso cost of sales adjustment (which was discontinued when the related product buy/sell activity stopped in 2012) was made to remove the financial impact of average inventory costing on cost of goods sold. The differential on those buy/sell transactions essentially represented the cost to move a barrel from Houston to El Paso, and so approximated what a “spot tariff” for those periods would have been if the customer had shipped on the line rather than entering the buy/sell arrangement with us (to be clear, though, the buy/sell activity was recorded as product sales and purchases, not transportation tariff revenue). The DCF adjustment removed the non-cash impact of the average inventory methodology, so that the financial results in our DCF table reflected the

Karl Hiller

Branch Chief

U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission

October 3, 2013

economics of the actual buy/sell transactions made for that period, irrespective of beginning inventory amounts. A more thorough explanation follows:

The Houston-to-El Paso cost of sales adjustment was related to a unique service offering that Magellan formerly offered only for this portion of its pipeline system. This activity was stopped with the conversion of the pipeline to crude service in 2012. This activity began when we acquired the pipeline in late 2009 from the previous owner out of a bankruptcy proceeding. At the time of acquisition, the pipeline system was idle. As a result, in order to promote shipments on the pipeline, we had to acquire the line-fill inventory (i.e. the working inventory required to operate the pipeline system) ourselves. This was unique for Magellan because we typically require our shippers on our pipeline systems to carry the line-fill inventory. As we are not typically in the business of owning and taking risks on the products we ship for others, we hedged this line-fill inventory position by selling forward NYMEX contracts against the inventory. Later, as we brought third-party shippers to this pipeline, we required them to carry the line-fill inventory, and sold down our inventory position.

Because the pipeline was idle when we acquired it, and there was not a constant flow of new product coming into the pipeline, it was difficult for us to provide shippers with an exact estimate of when their product would arrive in El Paso. In refined products and other liquid pipelines, typically new product must come into a pipeline to push product that is in the pipeline to its final destination. This difficulty in estimating arrival times made it difficult to entice shippers to ship on the pipeline. To address this issue, we began offering a service in which we bought a customer’s product in Houston and delivered our own line-fill product to them in El Paso, thereby ensuring an exact delivery time. Typically, the actual price differential between our commodity purchase cost in Houston and our sales price to the customer in El Paso would approximate a discounted tariff cost to move product on our pipeline from Houston to El Paso: effectively we bought product from a customer in Houston and sold that product to the customer in El Paso for a premium that reflected a discounted tariff rate. However, the impact on our financial statements did not reflect those buy/sell economics with the customer, because Magellan follows a lower-of-average-cost-or-market approach for our inventory valuation. Following this approach, the actual cost of the product purchased from the customer was blended with our beginning inventory cost, resulting in a new blended average cost, and that average blended cost had to be used to arrive at the cost of goods sold price that was matched with the product sales price we realized in El Paso when we sold product to the customer. Thus our financial results were not consistent with the buy/sell economics entered into with customers. As a result, in our DCF calculations, we began making an adjustment to our cost of goods sold to adjust for the distorting impact of our average inventory costing approach.

Karl Hiller

Branch Chief

U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission

October 3, 2013

The adjustments were simply timing related and ended in 2012, when the activity was halted and the line was idled so that it could be put into crude oil service. The details of the adjustment can be found on page 43 of our 2012 Annual Report on Form 10K, and are also included below:

Lower-Cost-or-Market Adjustment

A majority of our inventory is economically hedged through NYMEX hedges, subject only to very minor allowances for un-hedged product as outlined in Magellan’s commodity management policy. However, a portion of our NYMEX contracts do not qualify for hedge accounting treatment, and as a result, the underlying inventory that those contracts hedge must be evaluated versus prevailing market prices at the end of each period. To the extent prevailing market prices are less than the inventory carrying cost, we incur a charge to our income statement to write-down the inventory cost to the prevailing price. When calculating DCF, we adjust net income to eliminate this non-cash charge from net income because our inventory is economically hedged. Likewise, in quarters following a lower-cost-or-market adjustment, our financial statement will reflect a higher gain when the inventory is sold as a result of the previous period inventory write-down. In that case, we remove the incremental gain from net income. As a result, lower-cost-or-market adjustments are simply timing related as demonstrated below:

| |

| 5. | Given your disclosure stating that you utilize your non-GAAP measure of Distributable Cash Flow “….to determine the amount of cash that our operations generated that is available for distribution to our limited partners,” please explain why you have not reconciled this non-GAAP liquidity measure to operating cash flow as the most directly comparable GAAP measure, rather than net income, to comply with Item 10(e)(1)(i)(B) of Regulation S-K. |

Response: We have always viewed DCF as a performance measure rather than a liquidity measure. In our annual proxy, we disclose that DCF, adjusted for commodities, is the performance measure used in calculating our named executive officer’s long-term incentive payout. Accordingly, we report our DCF schedule under Results of Operations in Management’s Discussion and Analysis of Financial Condition and Results of Operations, rather than under Liquidity and Capital Resources.

We believe that net income is preferable to cash from operations as the most directly comparable GAAP measure to distributable cash flow. As you note, we do state that we utilize DCF “to determine the amount of cash that our operations generated that is

Karl Hiller

Branch Chief

U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission

October 3, 2013

available for distribution to our limited partners”; however, we do not think it follows, and we do not thereby intend to imply, that DCF is a non-GAAP “liquidity measure, ” as you suggest. As we explain in Item 6, page 31, “Our partnership agreement requires that all of our available cash, less amounts reserved by our general partner’s board of directors, be distributed to our limited partners.” Management’s recommendations to our general partner’s board of directors regarding distributions to our partners, including recommendations regarding amounts to be reserved, are not and never have been driven by liquidity concerns. Nor are they influenced by working capital fluctuations captured by cash from operations. Instead, they are a function of the on-going operating performance, or results of operations, of our assets. That is why we believe net income to be the most comparable GAAP measure to DCF, because the way we use DCF is most comparable to the way net income is used, namely as a measure of how our assets have performed during the period. In that regard, our decision to reconcile to net income as opposed to cash from operations is based on a very similar rationale to that of companies who reconcile non-GAAP measure of “EBITDA” or “Adjusted EBITDA” to net income.

In making distribution decisions, however, we are specifically focused on the cash generation performance of our assets, rather than their GAAP earnings performance. That is why we make adjustments to net income to reflect non-cash items, such as depreciation and non-cash asset write downs, as well as out-of-period items that are included in net income for the period per GAAP but which relate to future or prior periods. It is also why we adjust (i.e. reduce) DCF for maintenance capital, which per GAAP is an “investing activity” but which we believe to reflect a reduction in the cash generation performance of our assets.

In addition, there are several other reasons for reconciling to net income including (1) ease of understanding, (2) timing, (3) consistency and (4) comparability.

Ease of understanding

In order to tie cash from operations to distributable cash flow, we have to include items from both cash from investing activities (maintenance capital and distributions in excess of equity investment earnings) as well as items from financing activities (settlement of tax withholdings on long-term incentive compensation). In addition, we must adjust for working capital fluctuations, as these are temporary cash flow items that are financed through short-term borrowings or cash on hand and not used in making distribution decisions. Furthermore, we have to adjust for pension settlement cost and actuarial amortizations, as we choose to use accrued pension costs as distributable cash flow items, as those relate to the current period performance of our assets, while cash from operations includes pension-related items that may relate to future periods (for example, contributions to our plans in excess of periodic costs that increase funding status and will reduce future plan contributions). Finally, we have to make commodity adjustments in the same way we make adjustments in our current approach of reconciling from net income.

Karl Hiller

Branch Chief

U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission

October 3, 2013

A table demonstrating the reconciliation of cash from operations to distributable cash flow follows:

This table reconciliation is approximately the same size and complexity as our current reconciliation to net income, but in our view is less familiar to investors, who are accustomed to non-GAAP measures such as EBITDA or Adjusted EBITDA that are reconciled to net income. We believe an investor will more easily comprehend adjustments to net income than adjustments to cash from operations when seeking to understand distributable cash flow. In addition, by reconciling from Net Income, in that same calculation we provide an adjusted EBITDA reconciliation, which is an important consideration for investors when evaluating the level of leverage (debt to EBITDA) maintained by the partnership.

One other consideration is that we provide investors guidance to future net income, earnings per unit and distributable cash flow. We would find it unusual to provide guidance on cash from operations, as it would be very difficult to anticipate changes in working capital. Therefore for future guidance purposes, the only GAAP item available for distributable cash flow to be reconciled to is Net Income.

Timing

We strive to provide earnings results to the public as soon as possible following the end of each quarter, and when doing so, we also communicate our distributable cash flow results. We historically have not provided balance sheet or cash flow items in our expedited earning results, principally due to the fact that we believe footnote disclosures are important considerations when evaluating these items.

Because of our expedited earnings results process, we typically communicate our earnings results before completing and filing our Form 10-Q or 10-K. This is largely due to the additional effort that goes into developing and finalizing footnotes, as well as providing adequate time for review of the entire Form 10-Q or Form 10-K. Therefore, in order to provide distributable cash flow information in our earning release, the only GAAP item we have to reconcile to is Net Income.

Karl Hiller

Branch Chief

U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission

October 3, 2013

Consistency

We first began publicly reconciling distributable cash flow in the first quarter 2006. At that time and continuing through the current period, we have always considered DCF to be a performance measure. From the first quarter of 2006, and even from the inception of our partnership in early 2001, we have followed the same approach of deriving and reconciling distributable cash flow from net income. We believe our investors understand and are accustomed to this approach.

Comparability

We believe that most master limited partnerships (MLPs) follow the same approach as we do in reconciling distributable cash flow to net income. In reviewing twelve MLPs that have a large market capitalization and that are in the midstream sector, all but two reconcile distributable cash flow to net income. And of the two that do not reconcile to net income, neither appears to provide distributable cash flow in their filings. We believe investors are familiar with the reconciliation approach we follow and benefit from the comparability of this information to other MLPs.

I trust the responses discussed above adequately address your questions. If you have follow-up questions, please feel free to call me direct at (918) 574-7004.

Sincerely,

/s/ John D. Chandler

Chief Financial Officer

Magellan Midstream Partners, L.P.