Exhibit 99.2

Technical Report – Preliminary Economic Assessment Study

La Negra Mine

Minera La Negra S.A. de C.V.

Cadereyta de Montes (Maconí), Querétaro, Mexico

20°50’10”N, 99°30’55”W

Submitted in accordance with the standards of National Instrument 43-101 “Standards of Disclosure for Mineral Projects”, including National Instrument 43-101F1, of the Canadian Securities Administrators

Report Contributors: Scott G. Britton – P.E. Mining Plus US, Kim Kirkland – FAusIMM Mining Plus Peru S.A.C., Glenn Zamudio – FAusIMM Mining Plus Australia, Steven Truby – P.E. Wood EIS

Effective date: March 31, 2022

Date of Issue: June 29, 2022

CERTIFICATE OF QUALIFIED PERSON

I, Scott G. Britton, P.E., do hereby certify that:

| 1. | I am currently employed as Principal Mining Consultant by: |

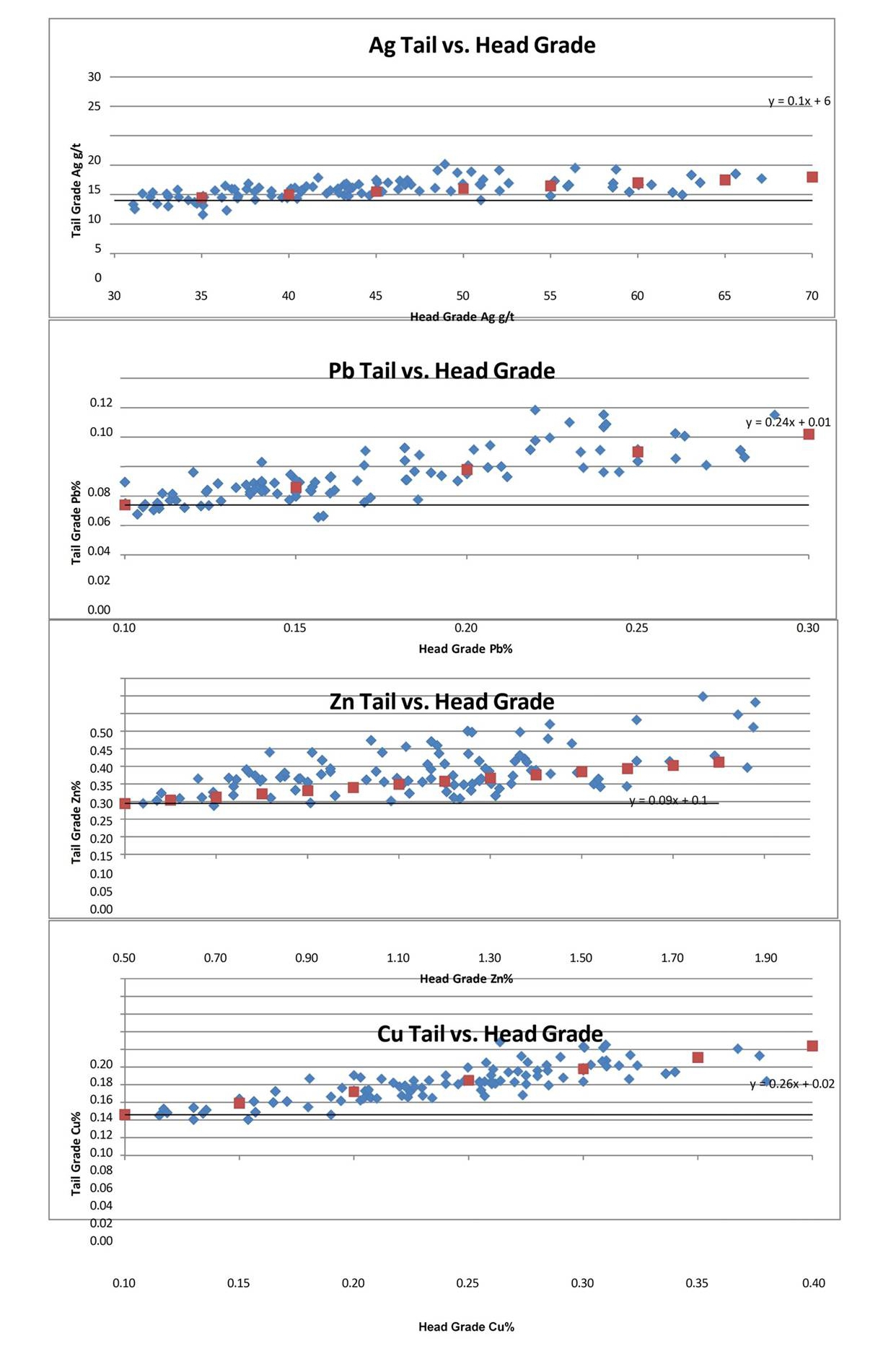

Mining Plus US

10185 Park Meadows Drive

Lone Tree, Colorado 80124 U.S.A.

| 2. | I am a graduate of the Virginia Polytechnic Institute and State University (Virginia Tech) and received a Bachelor of Science degree in Minerals Engineering in 1977. |

| | ● | Licensed Professional Engineer in the State of Wyoming (PE-032064) with reciprocity for other states in the United States of America |

| | ● | Registered Member in good standing of the Society for Mining, Metallurgy, and Exploration (SME), Inc. (#037051RM) |

| 4. | I have worked as a Mining Engineer for a total of 43 years since graduation from the Virginia Tech, as an employee of various mining firms and consulting companies. I have in excess of 5 years of experience directly related to underground narrow vein mining for base and precious metals, and/or the economic sale of minerals, exploration and resource development, including resource estimation and interpretation, resource evaluation, and technical reporting. |

| 5. | I have read the definition of “qualified person” set out in National Instrument 43-101 (“NI 43-101”) and certify that by reason of my education, affiliation with a professional association (as defined in NI 43 101) and past relevant work experience, I fulfill the requirements to be a “qualified person” for the purposes of NI 43-101. |

| 6. | I personally inspected the Minera La Negra mine and plant on March 27 through March 30, 2022. |

| 7. | I am responsible for the preparation of the report titled Technical Report – Preliminary Economic Analysis Study La Negra Mine dated June 29, 2022 with an effective date of March 31, 2022, with specific responsibility for Sections 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 13, 16, 17, 20, portions of 18, 21.1, 21.1-21.4, 22.2-22.3, 23, 24, 25, 26, 27 of this report. |

| 8. | I have had no prior involvement with the property that is the subject of this Technical Report. 9. As of the date of this certificate and as of the effective date of the Technical Report, to the best of my knowledge, information and belief, the Technical Report contains all scientific and technical information required to be disclosed to make the report not misleading. |

| 10. | I am independent of the issuer applying all of the tests in section 1.5 of NI 43-101. |

| 11. | I have read National Instrument 43-101 and Form 43-101F1, and the Technical Report has been prepared in compliance with that instrument and form. |

Dated June 29, 2022,

“Signed”

Scott G. Britton

CERTIFICATE OF QUALIFIED PERSON

Kim Kirkland, FAusIMM

Principal Mining Engineer

Mining Plus Peru S.A.C.

Avenida José Pardo 513, Office 1001

Miraflores, Lima 15074 Perú

I, Kim Kirkland, FAusIMM, am employed as a Principal Mining Engineer with Mining Plus Peru S.A.C. (Mining Plus), with an office address at Avenida José Pardo 513, Office 1001, Miraflores, Lima Perú.

This certificate applies to the technical report titled Technical Report – Preliminary Economic Analysis Study La Negra Mine dated June 29, 2022, with an effective date of March 31, 2022 (the “technical report”).

I am a Fellow of AusIMM #309585 in good standing. I graduated with a Bachelor of Science degree in Geological Engineering from University of Utah 1987.

I have practiced my profession for 35 years. I have been directly involved in precious and base metal production, resource estimates, studies and management in North and South America during that timeframe.

As a result of my experience and qualifications, I am a Qualified Person as defined in National Instrument 43– 101 Standards of Disclosure for Mineral Projects (NI 43–101) for those sections of the technical report that I am responsible for preparing.

I have personally visited the La Negra mine and facilities on March 27-30 2022.

I am responsible for Sections 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, and 14 of the technical report.

I am independent and have no prior involvement with Minera La Negra, as independence is described by Section 1.5 of NI 43–101.

I have been involved with the La Negra Mine Project since February 2022.

I have read NI 43–101 and the sections of the technical report for which I am responsible have been prepared in compliance with that Instrument.

As of the effective date of the technical report, to the best of my knowledge, information and belief, the sections of the technical report for which I am responsible contain all scientific and technical information that is required to be disclosed to make the technical report not misleading.

Dated: June 29, 2022,

“Signed”

Kim Kirkland, FAusIMM

CERTIFICATE OF QUALIFIED PERSON

I, Glenn Zamudio, FAuslMM, am employed as a Senior Principal Consultant with Mining Plus Australia, with an office address at Bravo Building, 1 George Wieneke Drive, Perth Domestic Airport, WA 6105.

This certificate applies to the technical report titled Technical Report – Preliminary Economic Analysis Study La Negra Mine dated June 29, 2022, with an effective date of March 31, 2022 (the “technical report”).

I am a Fellow of AuslMM #3003821 in good standing. I graduated with a Bachelor of Science degree in Chemical Engineering and MBA from University of Cape Town, 1988 and 1994, and Chartered Financial Analyst, 2001.

I have practiced my profession for 35 years. I have worked in the Investment Banking division of a merchant bank and have been involved in mining for the last 15 years as a general manager projects and a mining executive.

As a result of my experience and qualifications, I am a Qualified Person as defined in National Instrument 43- 101 Standards of Disclosure for Mineral Projects (NI 43-101) for those sections of the technical report that I am responsible for preparing.

I am responsible for Sections 19, 21, 22 of the technical report.

I am independent and have no prior involvement with Minera La Negra S.A. de C.V., as independence is described by Section 1.5 of NI 43-101.

I have been involved with the La Negra Mine Project since February 2022.

I have read NI 43-101 and the sections of the technical report for which I am responsible have been prepared in compliance with that Instrument.

As of the effective date of the technical report, to the best of my knowledge, information and belief, the sections of the technical report for which I am responsible contain all scientific and technical information that is required to be disclosed to make the technical report not misleading.

Dated: June 29, 2022,

“Signed”

Glenn Zamudio, FAuslMM

CERTIFICATE OF QUALIFIED PERSON

I, Steven Truby, P.E, am employed as a Principal–Geotechnical Engineer with Wood Environment & Infrastructure Solutions, Inc. (“Wood”), with a business address at 2000 S Colorado Blvd Ste 2-1000, Denver, CO, 80222-7931.

This certificate applies to the technical report titled Technical Report – Preliminary Economic Analysis Study La Negra Mine dated June 29, 2022, with an effective date of March 31, 2022 (the “technical report”).

I am a Professional Engineer registered with the Department of Regulatory Authorities, Colorado, the Alaska State Board of Registration for Architects, Engineers, and Land Surveyors and the Nevada State Board of Professional Engineers and Land Surveyors. I graduated from the University of the Witwatersrand, Johannesburg, South Africa in 1991 with a B.Sc. in Civil Engineering, and from the University of the Witwatersrand in 1996 with a M.Sc. in Civil Engineering.

I have practiced my profession for 28 years. I have been directly involved in the design, construction and permitting of mine tailings storage facilities, water management infrastructure and leach pads.

As a result of my experience and qualifications, I am a Qualified Person as defined in National Instrument 43– 101 Standards of Disclosure for Mineral Projects (“NI 43–101”) for those sections of the technical report that I am responsible for preparing.

I have not visited the Minera La Negra Project.

I am responsible for Sections 18.5.2 and 18.5.3 and portions of 21.1, 21.5, 22.1, 22.4, 25.3, and 27.4 of the technical report.

I am independent of Minera La Negra as independence is described by Section 1.5 of NI 43–101. I have no previous involvement with the Minera La Negra Project.

I have read NI 43–101 and the sections of the technical report for which I am responsible have been prepared in compliance with that Instrument.

As of the effective date of the technical report, to the best of my knowledge, information and belief, the sections of the technical report for which I am responsible contain all scientific and technical information that is required to be disclosed to make the technical report not misleading.

Dated: June 29, 2022

“Signed”

Steven Truby, P.E.

Contents

| 1 | Executive Summary | 1 |

| | | |

| 2 | Introduction | 25 |

| | | |

| 3 | Reliance on Other Experts | 27 |

| | | |

| 4 | Property Description and Location | 28 |

| | | |

| 5 | Accessibility, Climate, Local Resources, Infrastructure and Physiography | 35 |

| | | |

| 6 | History | 39 |

| | | |

| 7 | Geological Setting and Mineralization | 46 |

| | | |

| 8 | Deposit Types | 65 |

| | | |

| 9 | Exploration | 67 |

| | | |

| 10 | Drilling | 76 |

| | | |

| 11 | Sample Preparation, Analyses and Security | 81 |

| | | |

| 12 | Data Verification | 87 |

| | | |

| 13 | Mineral Processing and Metallurgical Testing | 91 |

| | | |

| 14 | Mineral Resource Estimates | 102 |

| | | |

| 15 | Mineral Reserve Estimates | 136 |

| | | |

| 16 | Mining Methods | 136 |

| | | |

| 17 | Recovery Methods | 173 |

| | | |

| 18 | Project Infrastructure | 179 |

| | | |

| 19 | Market Studies and Contracts | 188 |

| | | |

| 20 | Environmental Studies, Permitting and Social or Community Impact | 197 |

| | | |

| 21 | Capital Cost Summary | 216 |

| | | |

| 22 | Operating Cost Summary | 223 |

| | | |

| 23 | Economic Analysis | 234 |

| | | |

| 24 | Adjacent Properties | 242 |

| | | |

| 25 | Other Relevant Data and Information | 245 |

| | | |

| 26 | Interpretation and Conclusions | 248 |

| | | |

| 27 | Recommendations | 254 |

| | | |

| 28 | References | 257 |

| | | |

| 29 | Unit of Measure, Abbreviations and Acronyms | 258 |

This technical report has been prepared for Minera La Negra S.A. de C.V.

Minera La Negra (“MLN”) is a base metals and silver producer focused on restarting its 100%-owned La Negra mine, located in the Maconí District of the Sierra Gorda range of the State of Querétaro, in central Mexico. La Negra will be a mid-scale, low-cost polymetallic underground mining operation with drift access using long hole, open stope methods along with conventional flotation, initially processing up to 2,500 tonnes per day (tpd) to produce lead, zinc, and copper concentrates with silver values, and is targeting annual production of 23.3 moz of payable silver equivalent (Ageq) over an initial 7.5-year mine life.

Mineralization in the vicinity of the La Negra mine was known in pre-Hispanic times, and small operations in the area were developed during the Spanish Colonial era. Although the La Negra orebody had been discovered previously by other operators, it was first developed in the 1960s by Industrias Peñoles S.A. de C.V. and achieved commercial production in 1971. Mining has proceeded to operate almost continuously since then as other deposits have been discovered and developed. The mine was closed in March of 2020 due to the government-mandated Covid-19 shutdown. The decision was made at that time not to reopen until certain pending had been resolved. These included: taxation issues, a new contract with the union, an extension of the land-use agreement with the local communities, a near-mine drilling program, and new resource and mine plan, which have all been resolved. All pending issues with the tax authority, SAT, were concluded in February of 2021, and a new labor contract went into effect in April of 2021, with a 15-year extension of the land-use agreement signed in July of 2021.

The Technical Report was completed by the authors with the assistance of the following independent consultants:

| ● | A-Geommining – Core Logging, Surface Exploration, and Exploration Program QA/QC |

| ● | Think Data MX – Socioeconomic studies for Section 20 |

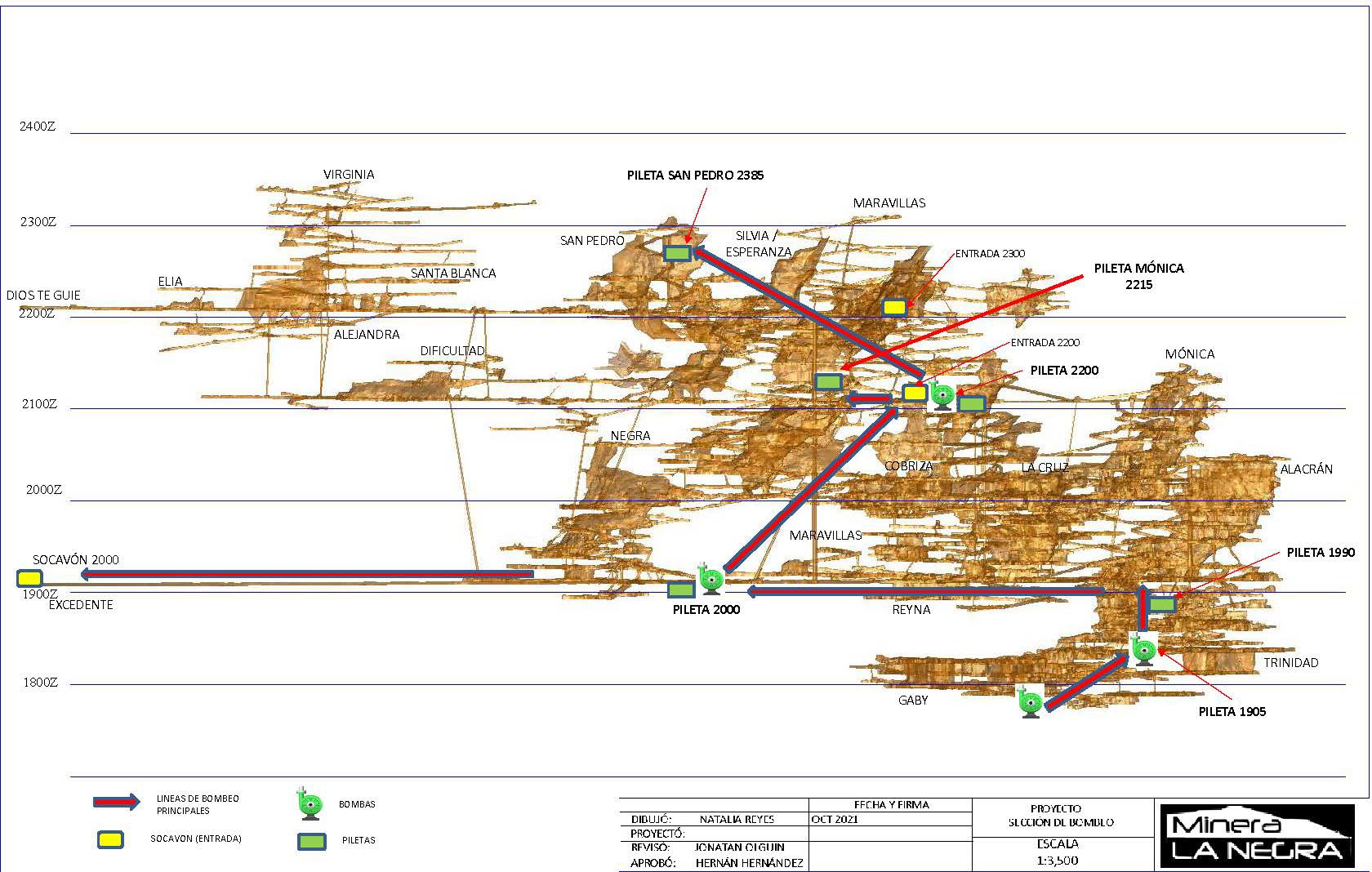

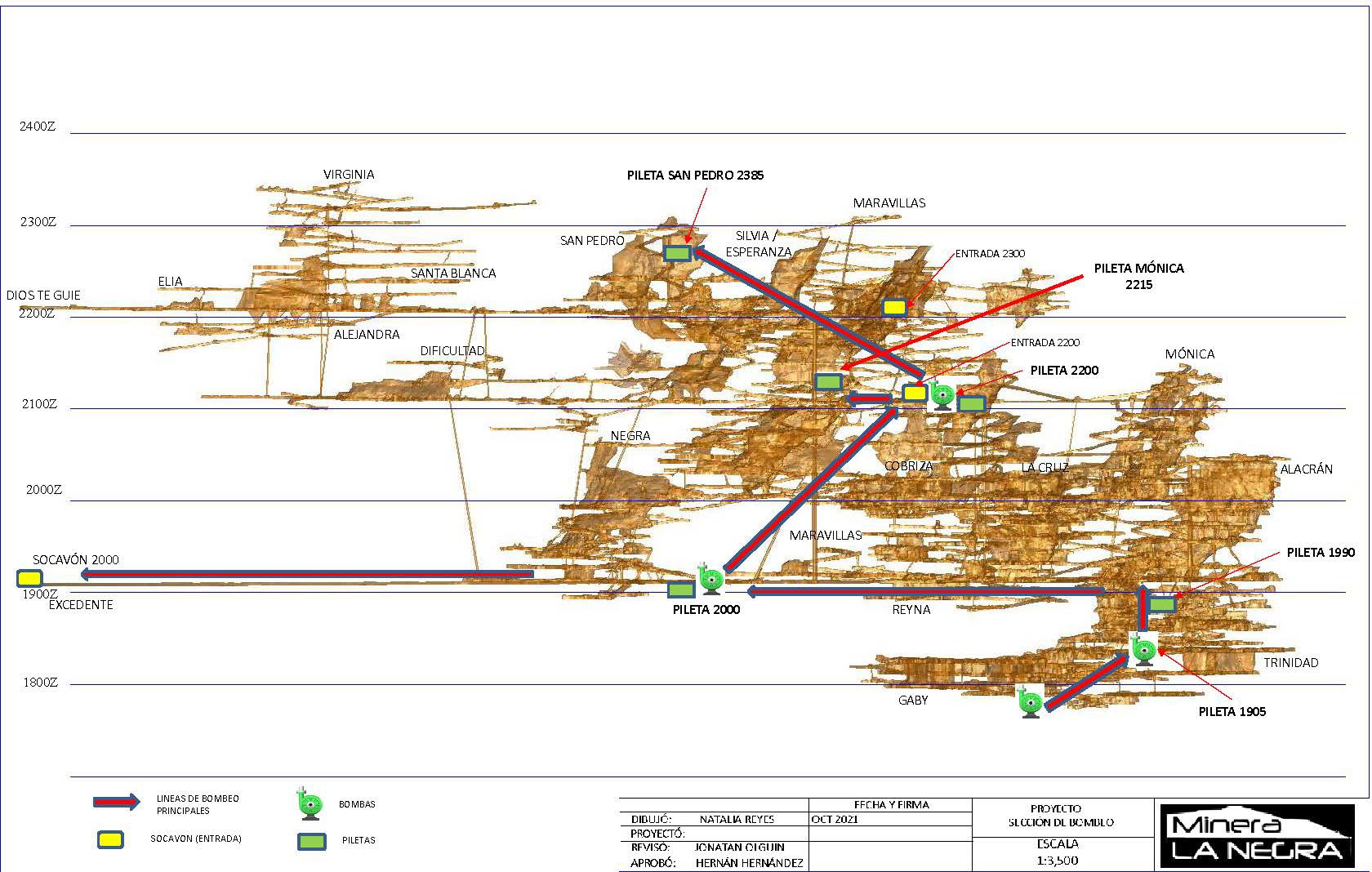

| ● | Integración de Procesos para Minas Carrillo (IPMC) – Paste Backfill Plant preliminary design, Section 26.3 |

This report presents the results of the PEA using the guidance of the Canadian Securities Administrators’ National Instrument (NI) 43-101 and Form 43-101F1 and Canadian Institute of Mining (CIM) guidance on Resource and Reserve Estimation. The authors of this report note that the information and detail presented significantly exceeds that normally found in a PEA. The reason for including this additional information is that Minera La Negra is not a greenfields site, but rather a former producer with 50 years of history that is being reactivated and has access to a large amount of readily available information.

A site visit by Mining Plus occurred between March 27, 2022 and March 30, 2022.

Minera La Negra owns 100% of the La Negra project and holds all of the titles, rights, benefits, and obligations to the La Negra project, consisting of fifteen mineral concessions with an aggregate area of approximately 82,878 hectares. Minera La Negra is 99.99% owned by Orion Mine Finance (Master) Fund LLP (Orion) but has an agreement with Grupo Desarrollador Migo, S.A.P.I. de C.V. (M Grupo), a private Querétaro-based company whose principal business is infrastructure, real estate, industrial lighting and agricultural commodities, to apportion to them a share of any sales proceeds based on a pre-agreed formula.

| 1.2 | Property Description and Ownership |

The La Negra project is located in central Mexico approximately 90km in a direct line to the northeast of Querétaro, capital of the state of the same name, or approximately 150km by paved road (Figure 1.1). The center of the property is located at approximately 20o51.1.’ North Latitude and 99o30.9’ West Longitude (UTM 14Q 2303950N / 426443E (WGS84 datum)). The State of Querétaro has a population of 2.4M inhabitants, based on the 2020 census, and the capital city has a population of 1.1M. The main industrial activities in the state include automotive and aerospace manufacturing, as well as logistics and distribution, given its location close to Mexico City. The state also has a burgeoning agricultural sector, and produces primarily specialty products such as triticale, roses, asparagus, chickpeas, carrots, as well as an emerging viticulture industry.

Figure 1.1 Project Location Map

Source: MLN

The project is located in the district of Maconí, within the municipality of Cadereyta. Maconí and its environs have a population of approximately 3000 inhabitants, dependent primarily on the mine as well as on small-scale agriculture and small-scale business. In total, there are 21 communities in the vicinity of the mine, although most of these consist of only a handful of houses each. The mine site itself is 3.4 km east of the town of Maconí and is accessed by an all-weather gravel road.

Minera La Negra’s concessions are shown overleaf in Figure 1.2 with the corresponding concession number placed next to or overlaying the concession. Figure 1.3 shows the mine’s infrastructure and layout.

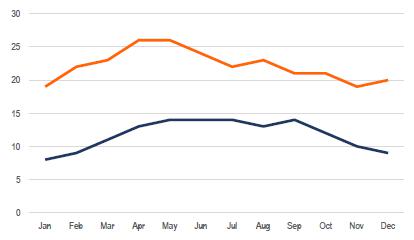

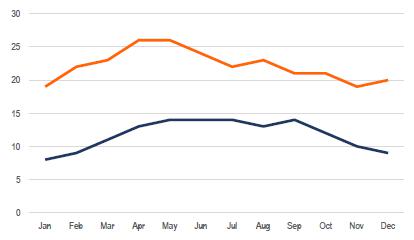

La Negra is located in a mountainous range known as the Sierra Gorda, consisting of rugged, steep topography with peaks up to 3100 m in altitude and deep river valleys at an elevation of 1700 m. The climate is temperate, but the region is semi-arid, and consists of scrubby vegetation and cacti, with deciduous forest (primarily oak) and pine trees in those areas that receive greater rainfall. The main portal for the mine is located at 1906 masl (although known as the 2000 level), with operations as high as 2300 m and as low as 1700 m. Figure 1.3 shows the layout of the mine.

Figure 1.2 La Negra Mining Concessions

Source: MLN

Figure 1.3 Minera La Negra Layout and Infrastructure

Source: MLN

The local workforce available to the mine include skilled miners and process operators with years of experience working at the mine.

As part of the company’s commitment to adding value to the local communities and building capacity in Mexico, the entire workforce of the operation is composed of Mexican nationals. The majority of the workforce is from the local communities, including skilled mechanical and electrical tradesmen. The positions that cannot be filled by local workers, primarily senior geologists and engineers and administrative staff, will be staffed with suitably qualified nationals.

The total mine workforce at full operations after restart is estimated to be 229 employees, consisting of 164 unionized workers and 65 salaried staff.

Figure 1.4 Map of Surrounding Communities and Settlement Areas

The evidence suggests that the area around La Negra may have been mined for minerals used for cosmetic and decorative purposes for at least 2,000 years. The Spanish began mining in the district in the 1500s and in the area around Maconí in the late 1600s. Mining by private individuals continued in the 1800s and 1900s on an intermittent basis and by 1950 the property was owned by Compañía Minera Acoma, S.A., although their activities were apparently not successful.

Peñoles, which had operated a small smelter 10km away in the vicinity of El Doctor, acquired the property in the early 1960s and carried out a mapping, sampling, and magnetic survey program which resulted in the discovery of the La Negra and El Alacrán deposits. Mine development began in 1967 and production commenced in 1971. In the year 2000 the property was put on care and maintenance due to low metals prices, and the property was acquired by Aurcana in 2006. In 2016 ownership of the property passed to Orion as part of a court-sanctioned Plan of Arrangement. Orion entered into a joint venture with M Grupo in August of 2020; in early 2022 the joint venture was modified to entitle M Grupo to a share of proceeds from the sale of MLN subject to a pre-agreed formula.

| 1.4 | Geology and Mineralization |

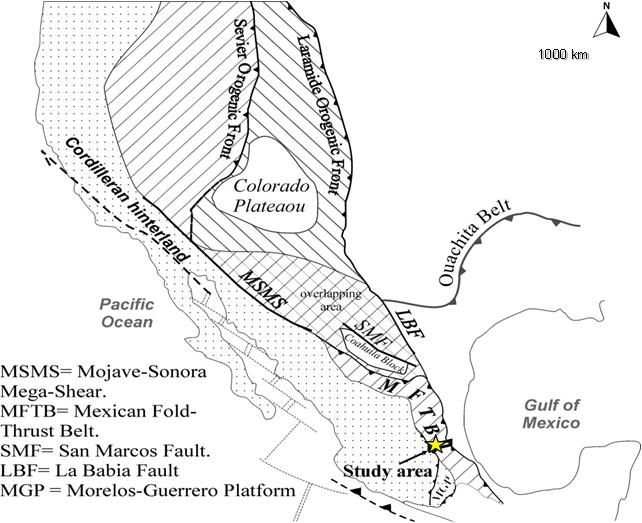

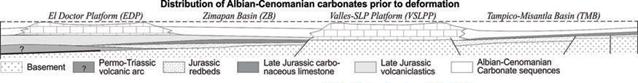

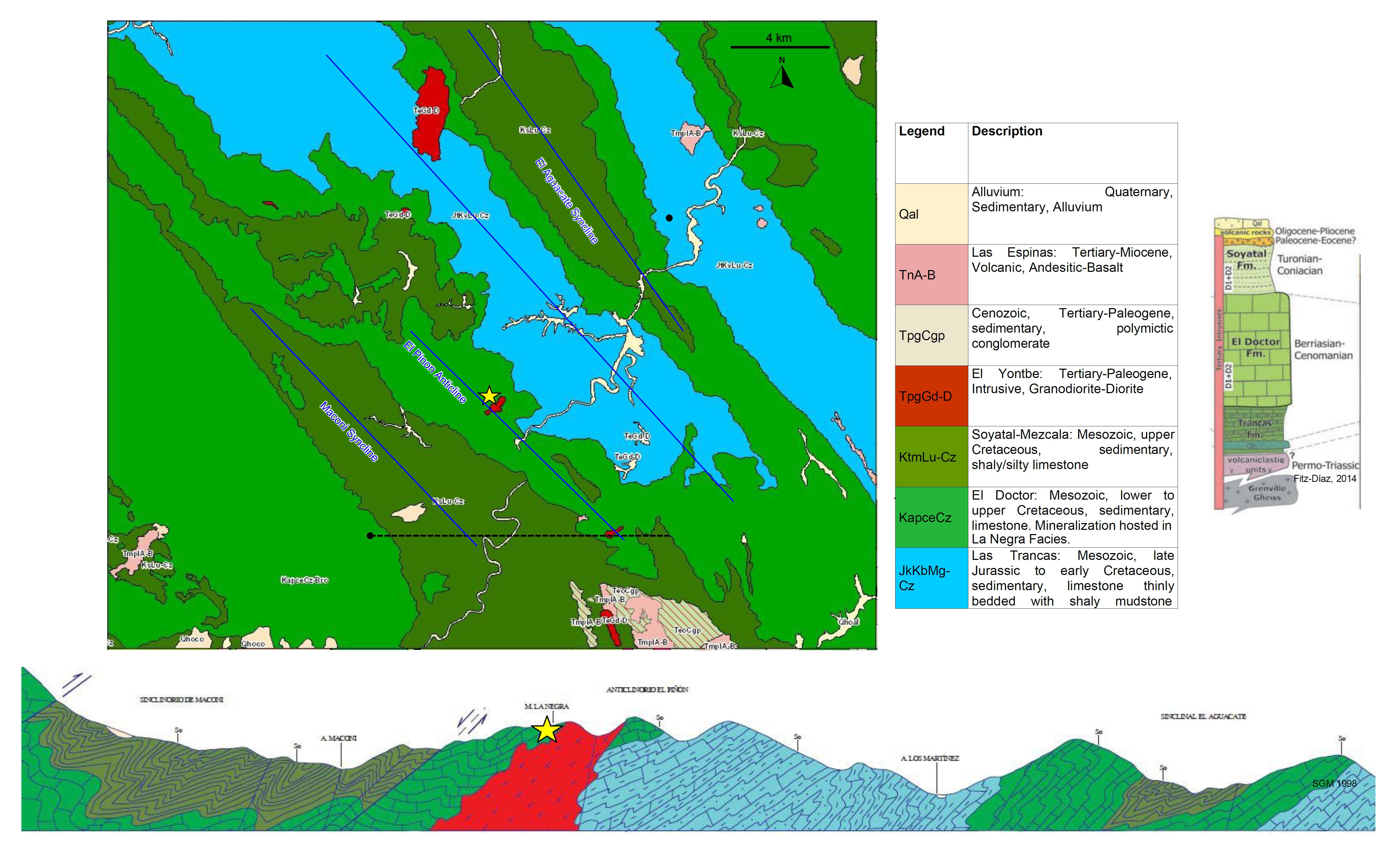

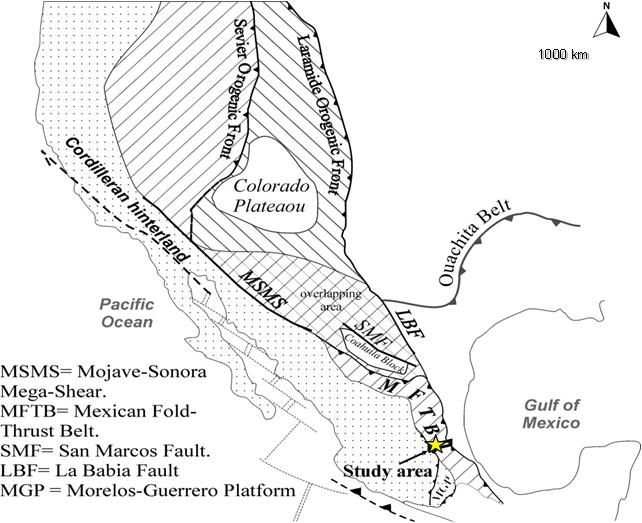

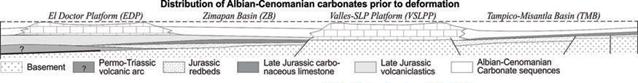

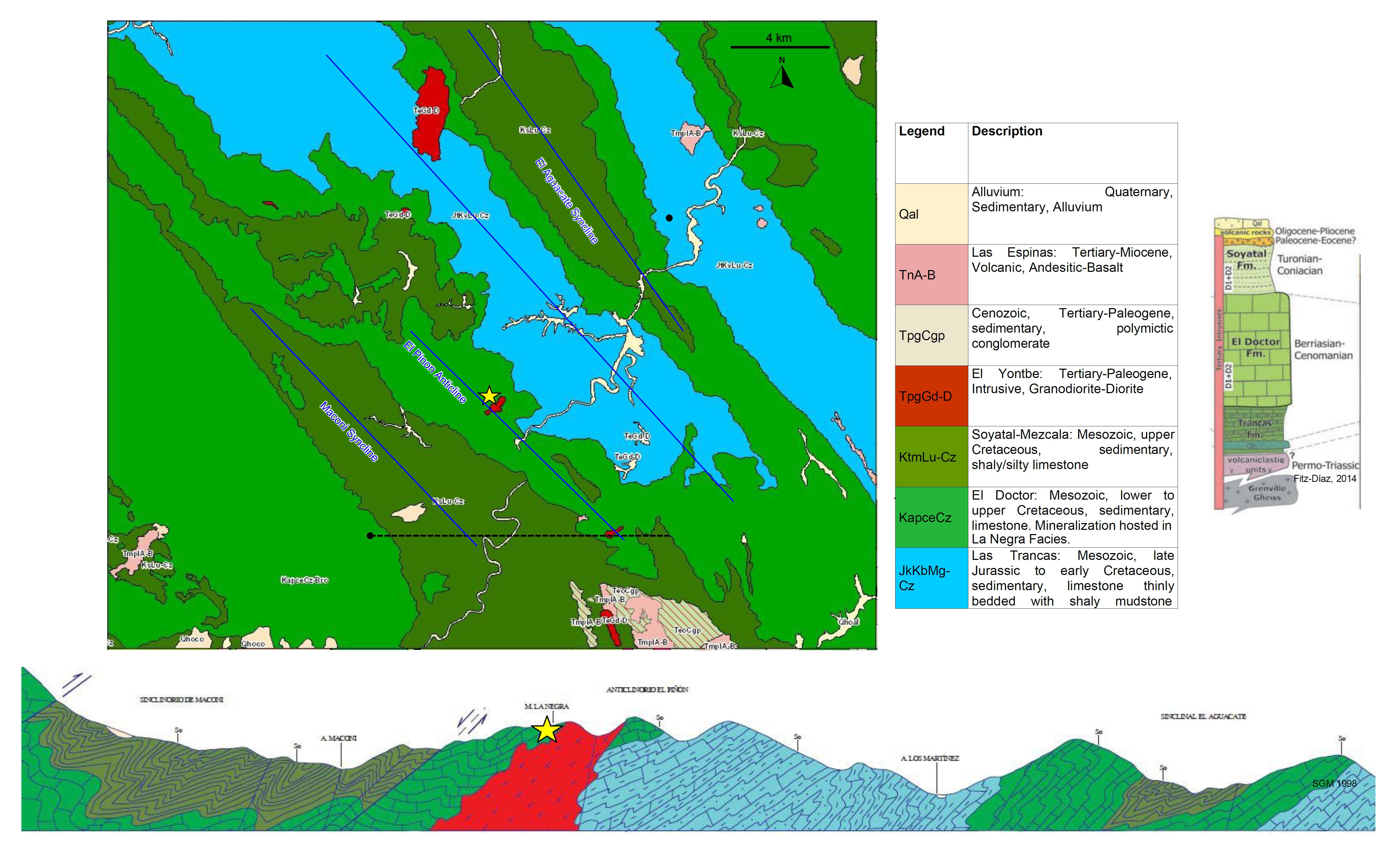

The La Negra property is located in the Sierra Gorda range, belonging to the Sierra Madre Oriental physiographic province. The main sedimentary host rocks were laid down during the late Jurassic through early Cretaceous and consist of two carbonate platforms – El Doctor to the west and Valles- San Luis Potosí to the east – with the deep water Zimapán basin, consisting of basinal carbonates with minor clastic material in between.

The collision of the Guerrero Terrane with the southwest coast of North America and the beginning of subduction signaled the beginning of the formation of the Mexican Fold and Thrust Belt (MFTB) about 83 million years ago. The Paleozoic basement and resistant carbonate rocks of the El Doctor platform buckled and were thrust to the NE over the sediments of the Zimapán basin, which deformed plastically resulting in high-amplitude folds.

Subsequent to the end of the Laramide orogeny and the termination of the compressional regime that formed the MFTB, the region experienced a period of extension (43-25 Ma) that led to minor normal faulting. Intrusive bodies exploited the NW-trending fold axes created during the formation of the MFTB as well as subsidiary NE-trending structures.

The principal geologic unit in the vicinity of La Negra is the La Negra facies of the El Doctor Formation, which strikes N in the area of the mine but is interpreted to broadly follow the NW trend of the Piñón Anticline, the fold axis of which is a major throughgoing structure. To the west, and potentially hosting NW extensions of the mineralization, is the San Joaquín facies of the El Doctor Formation, which forms a N trending band approximately 150 m wide. To the west of this, and outside any zones of known mineralization, is the foreslope Socavón facies of the El Doctor Formation.

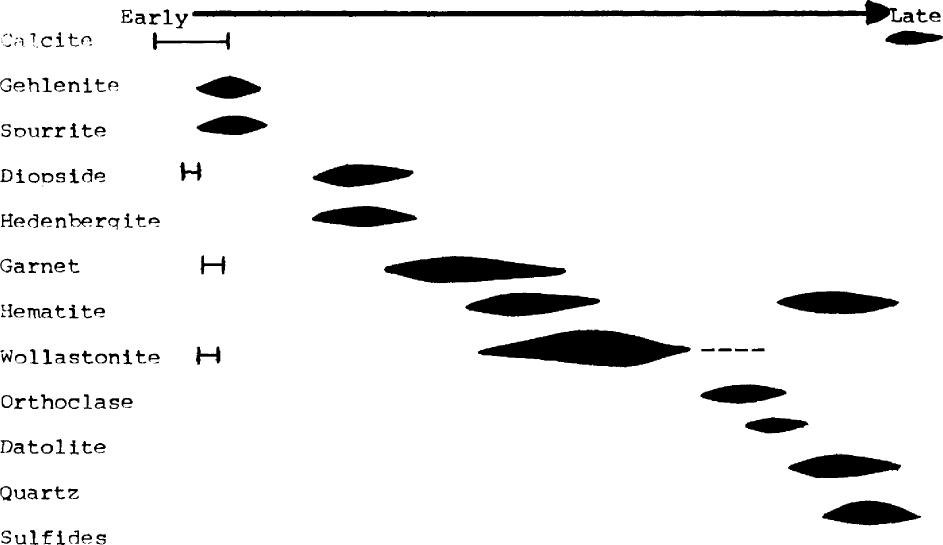

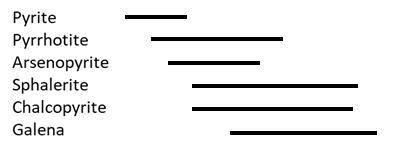

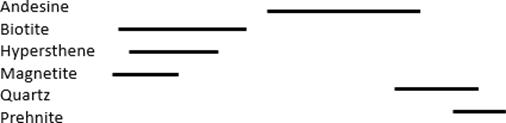

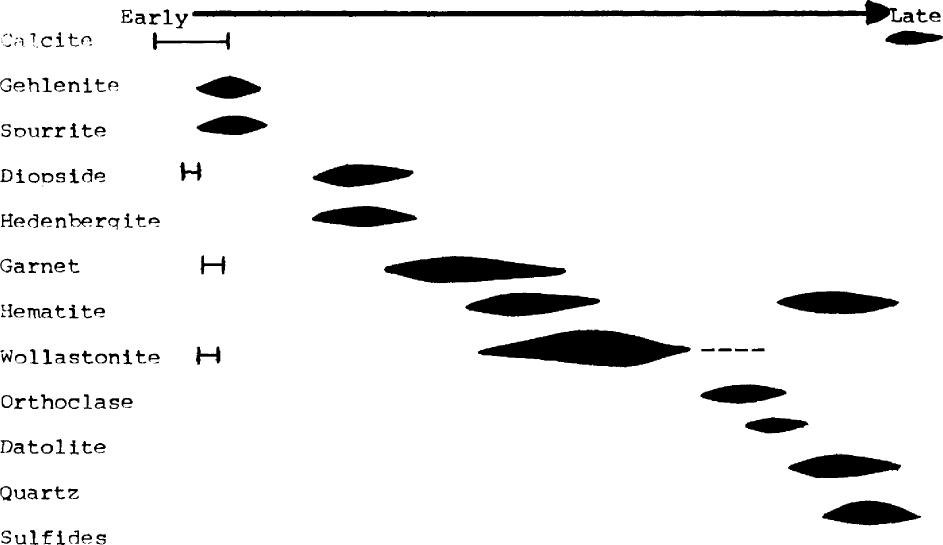

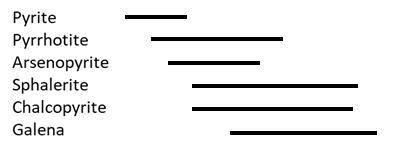

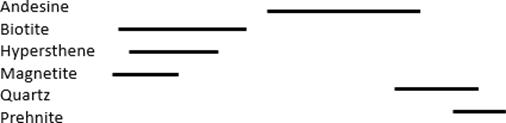

Four different phases of skarn mineralization have been identified with the economic mineralization formed in the final stage, which in addition to sulfides generated orthoclase, quartz, calcite and datolite. The principal minerals at La Negra consist of sphalerite (marmatite), galena, and chalcopyrite, with silver present as hessite [Ag2Te] in association with galena and as argentite and pyrargyrite. Other common, non-mineral sulfides include pyrite, minor pyrrhotite, lloelingite [FeAs2] and arsenopyrite. La Negra is classified as a Pb-Zn-Ag + Cu skarn.

| 1.5 | Exploration and Data Management |

MLN employs its own drillers and owns a variety of underground drill equipment, which is used primarily for definition drilling. The 2021 drill program, however, was caried out by an experienced independent drilling company. Underground drilling is generally controlled and monitored by mine geological staff, but for the 2021 exploration program this was managed by experienced geological contractors, who were tasked with confirming the surveys of the location of the drill collar and the azimuth and inclination of each hole. Core was delivered to the secure core sampling and storage facility at the main mine complex where it was recorded as received and entered into a control database that documented the process of logging and sampling. Prior to sampling, the core was checked for completeness and continuity, box numbering and length. The core was then cleaned and logged for lithology, mineralization, structure and alteration. All core was photographed to provide a digital record.

Intervals were selected for sampling on the basis of visual identification of mineralization. Sample lengths generally are one or two meters; barren intervals above and below mineralization are also sampled to ensure the limits of mineralization are captured by the sampling process. Core was cut with a saw and half was placed in a labelled plastic sample bag together with a corresponding sample tag. A sample tag was placed in the core box and a third copy was retained in the sample booklet. When sampling was completed, the samples were consigned to the mine assay lab through a chain of custody protocol. Samples were routinely assayed for silver, copper, lead, zinc, iron and arsenic and beginning in 2021 for antimony, bismuth, and cadmium. Umpire samples were sent to an independent lab.

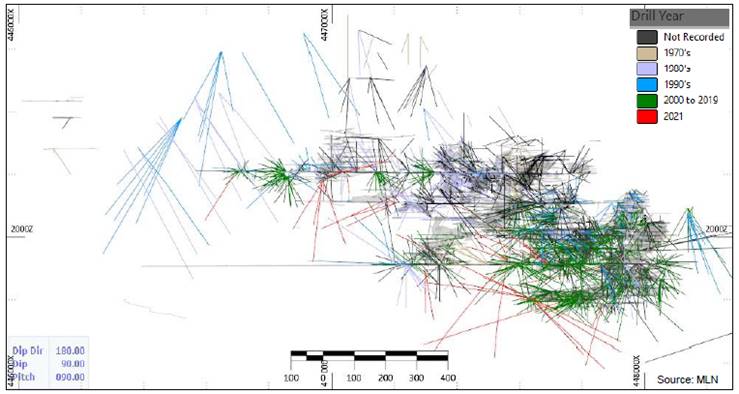

The 2021 drill program consisted of 35 holes totaling 9,800 meters, the global database contains approximately 47,000 underground drillhole assays.

| 1.6 | Metallurgical Testing and Mineral Processing |

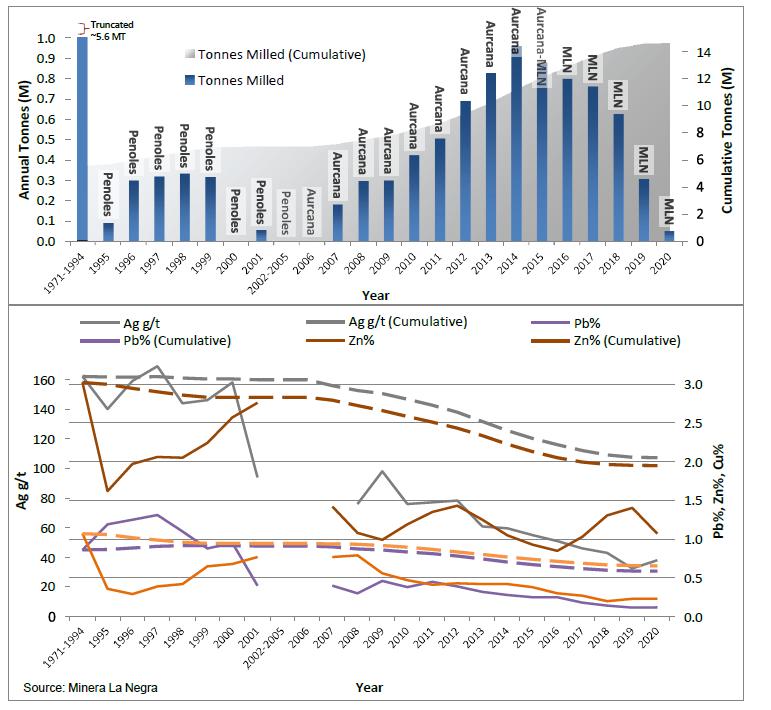

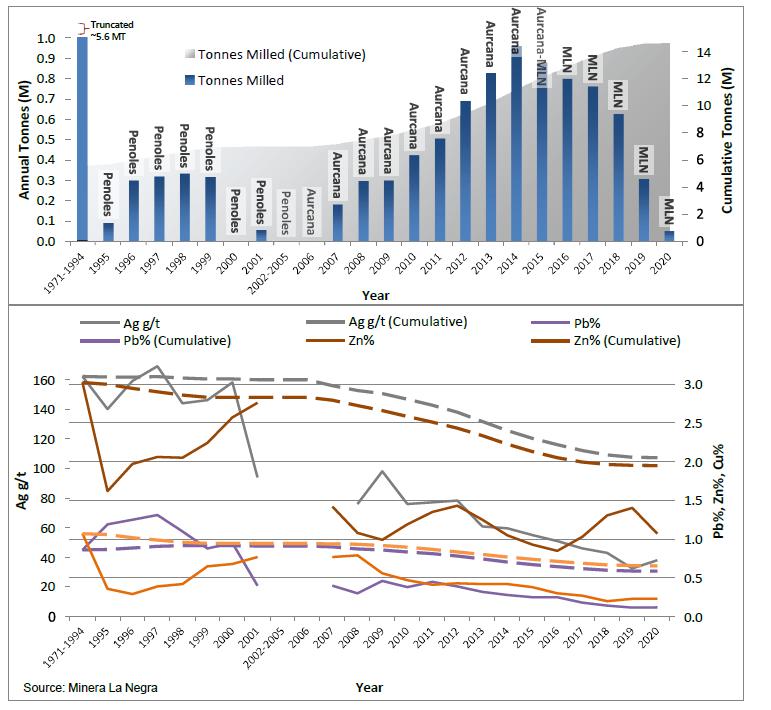

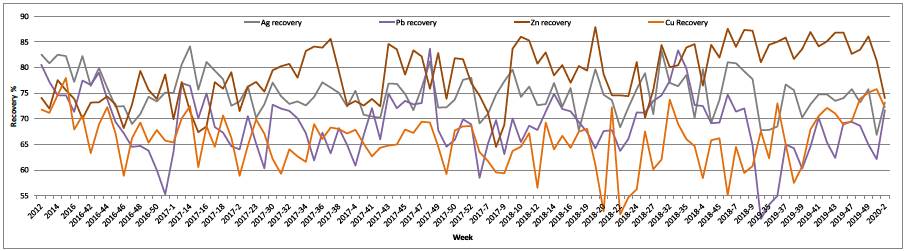

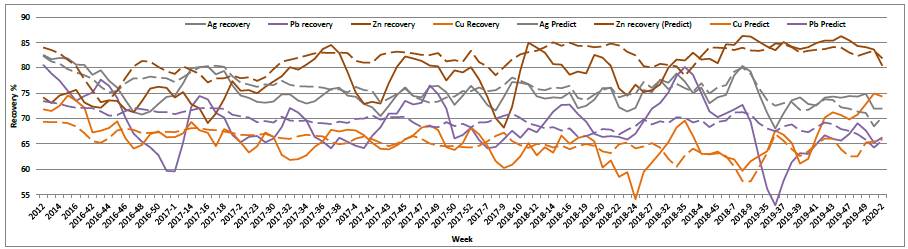

Minera La Negra initiated operations in 1971 and has been in continuous production for most of that time (see Figure 6.1).

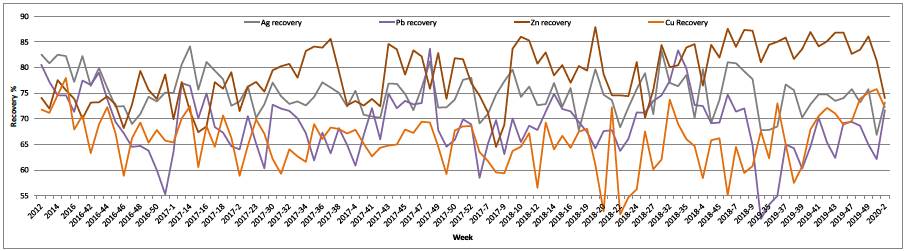

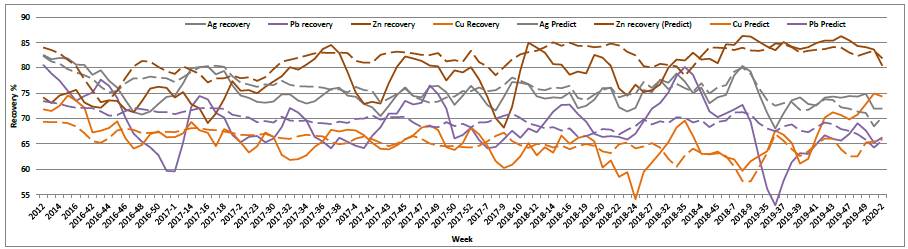

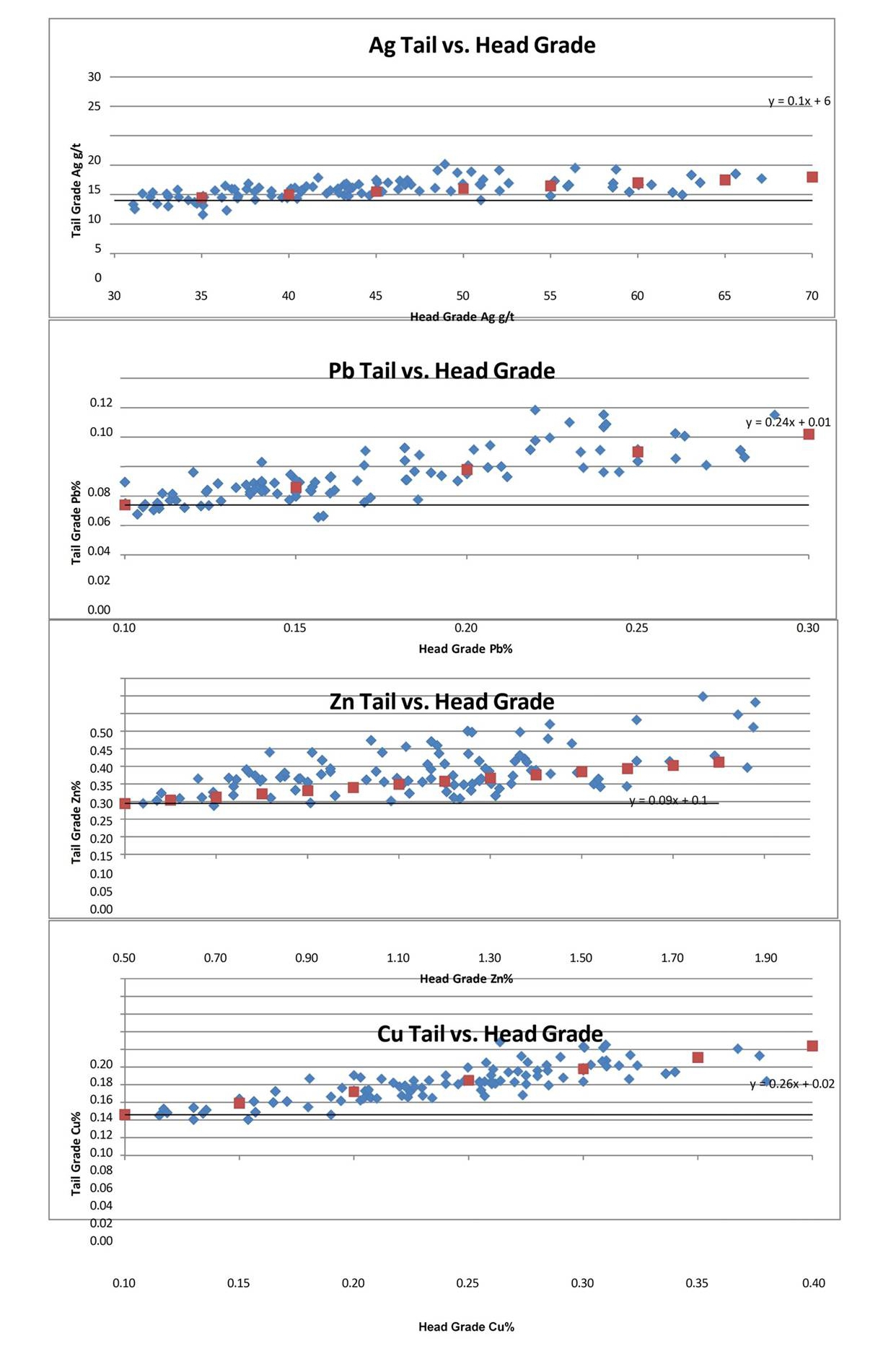

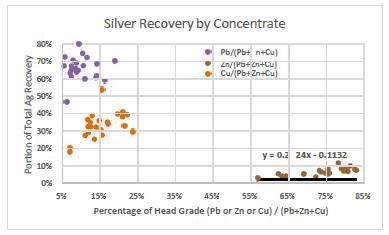

Other than various throughput expansions over the years, the processing plant flowsheet has been well established and is little changed, and operating parameters and recoveries are well understood. Production data for the period 2011-2019 is shown in Table 13.1. Estimated LOM recoveries are as follows: Ag – 79.7%, Pb – 72.3%, Zn – 84.0%, Cu – 68.0%.

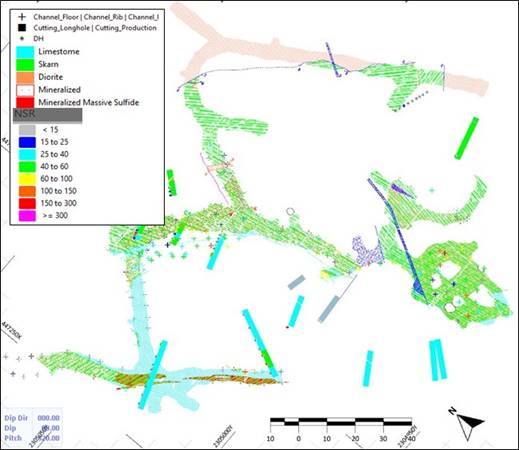

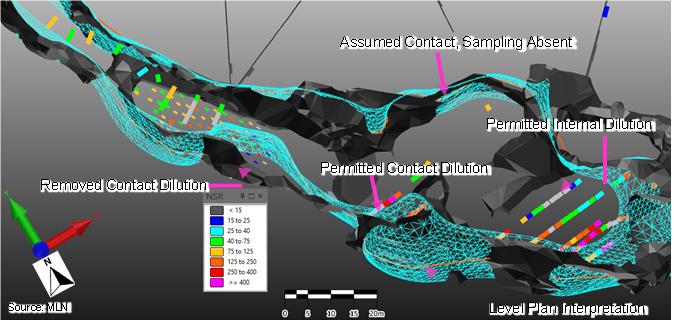

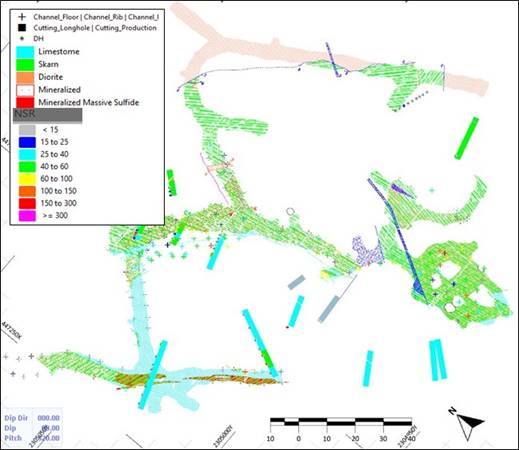

The most important aspect of the mine planning and mineral processing at La Negra is the correct calculation of the NSR for each tonne of rock in the model, as this directly drives the planning process for both the mine and the processing plant, as described in Sections13.2 through 13.12.

NSR is the dollar value of material after the metallurgical recovery, concentrate trucking charges, smelter payables, smelter deductibles, smelter penalties, and treatment charges have been accounted for. NSR does not account for mining cost, process cost, G&A, sustaining capital, dilution, royalties, VAT, or taxes. The purpose of the NSR is to compare material value to the breakeven costs of the mine.

| 1.7 | Mineral Resource Estimate |

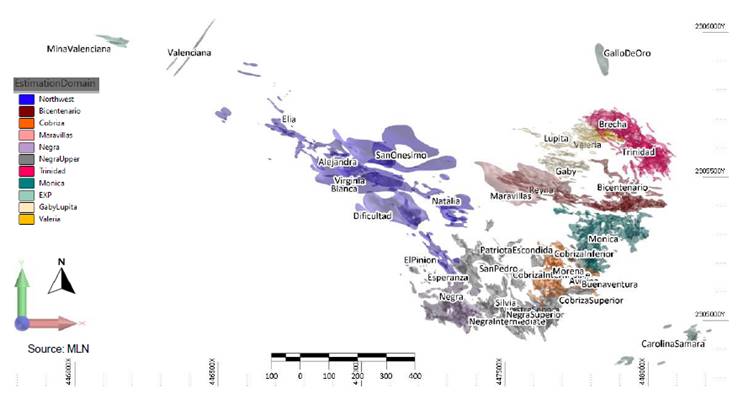

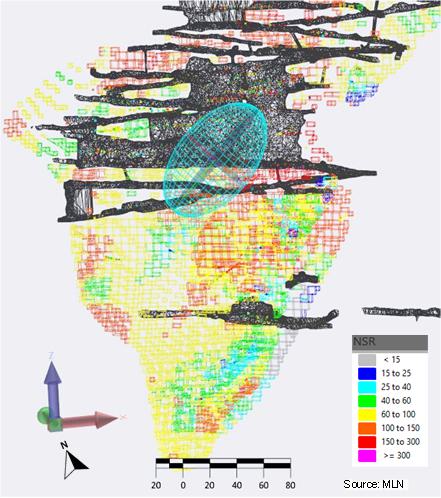

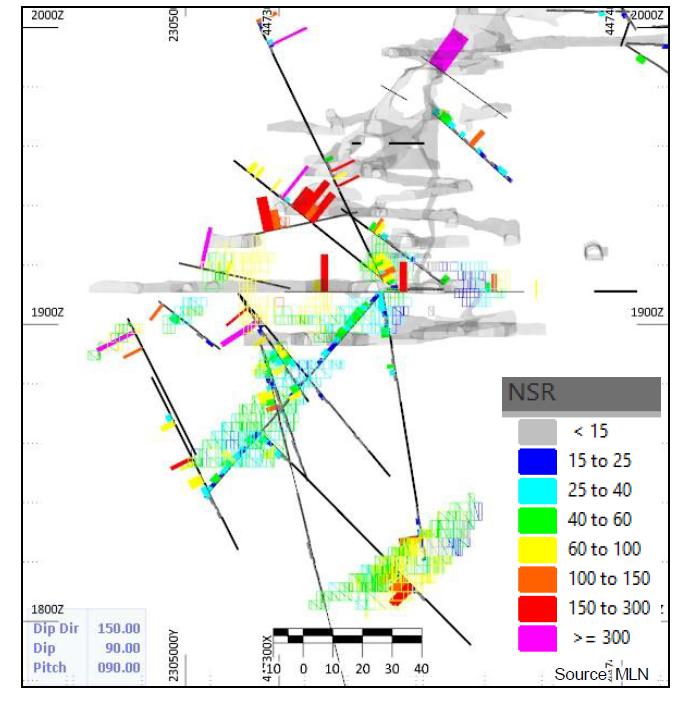

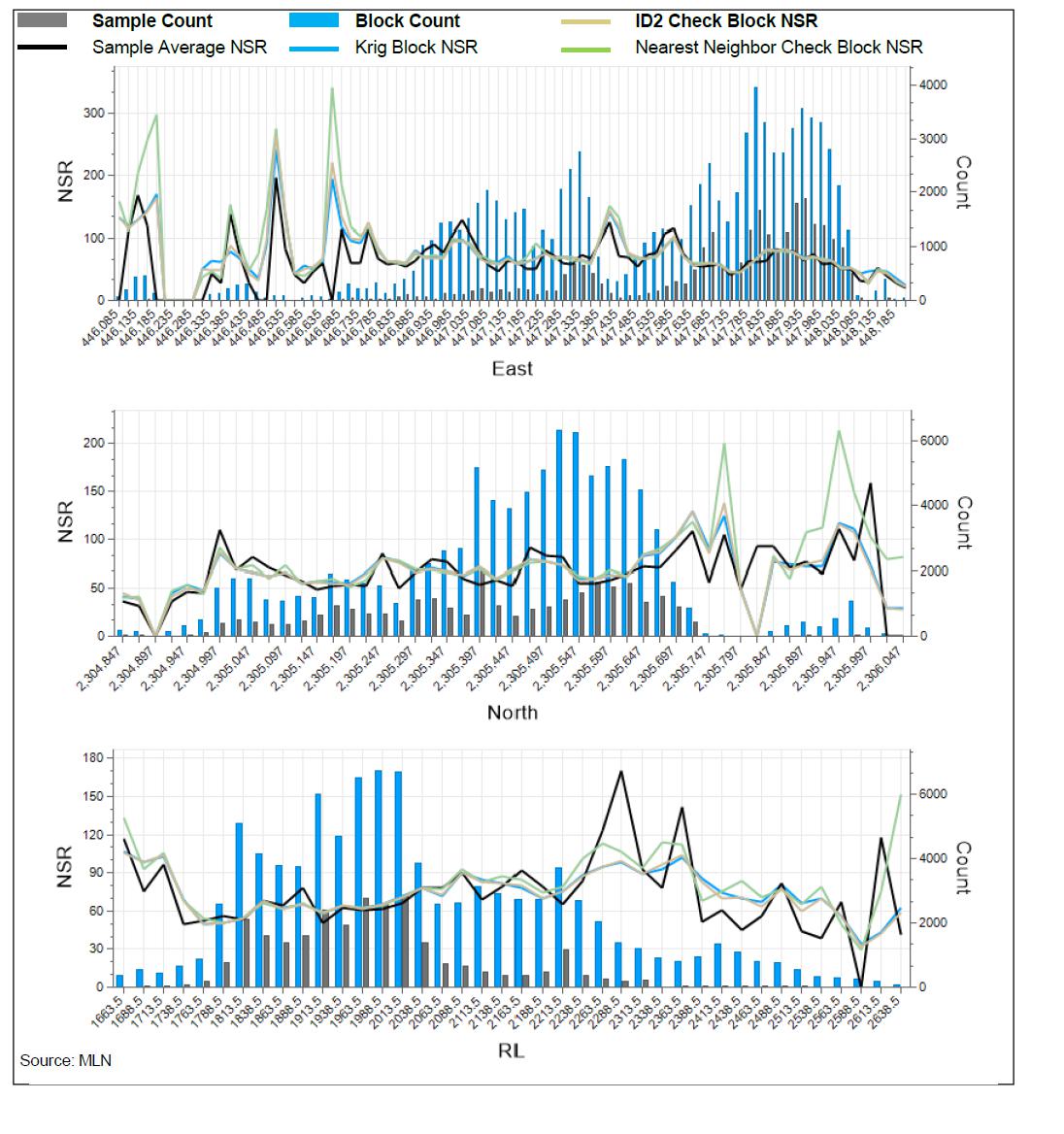

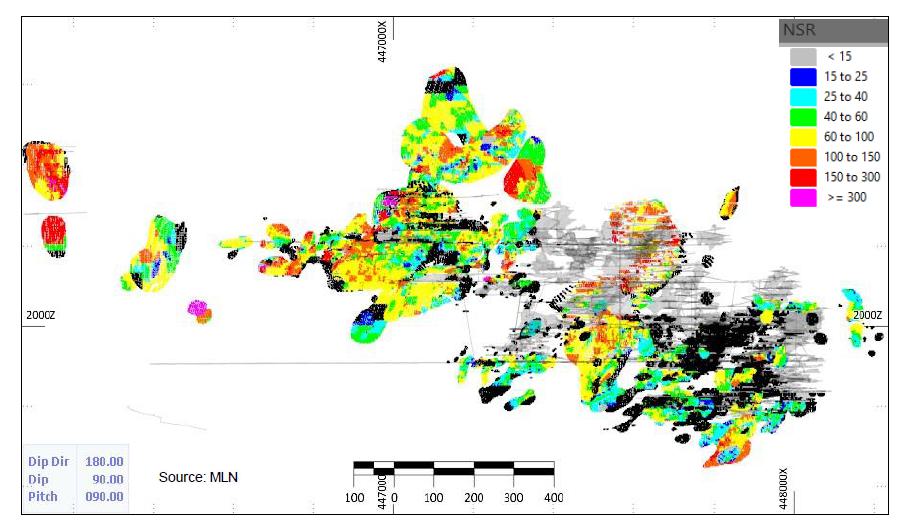

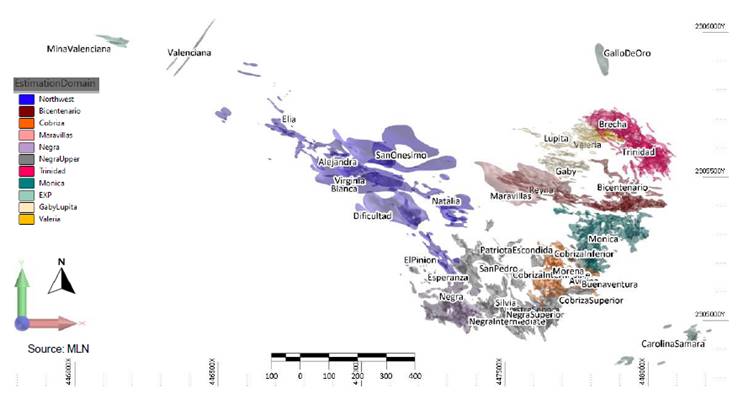

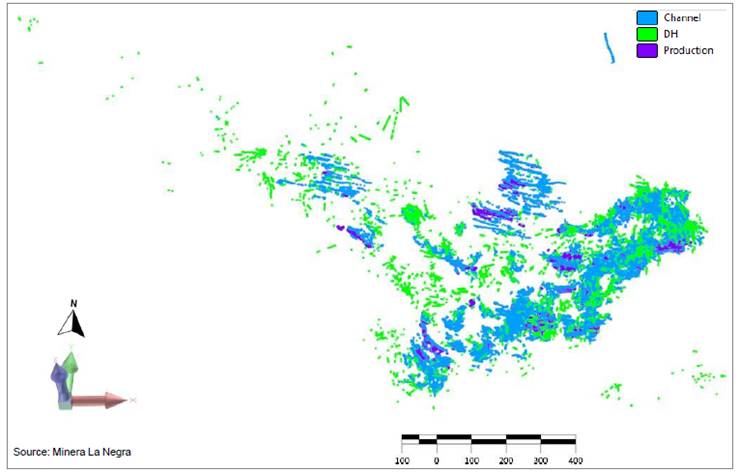

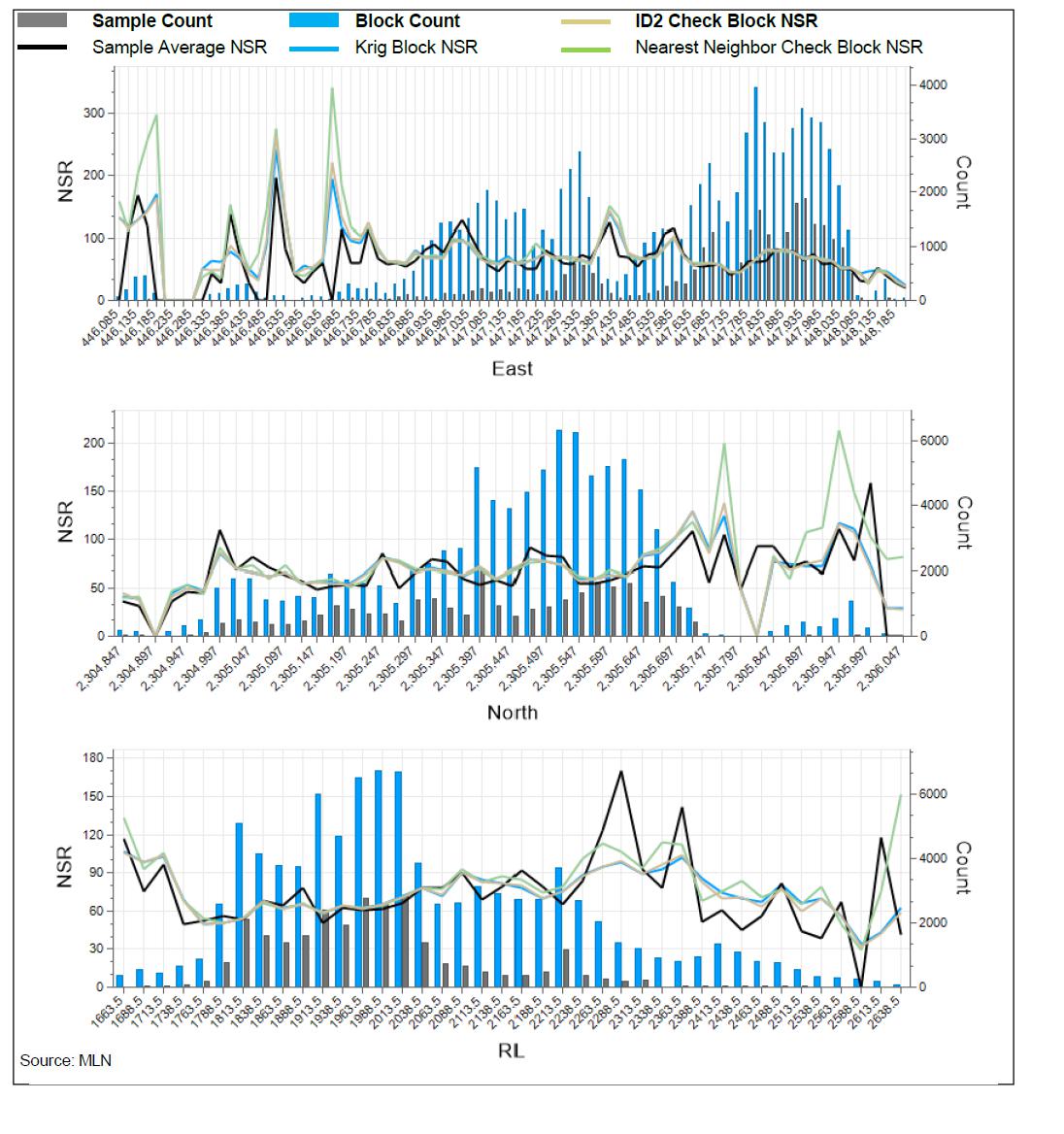

Resources for the La Negra mine have been estimated using Ordinary Kriging (OK), are wireframe constrained, and stated at a base case cut-off grade of US$28/t NSR accounting for value from Ag, Pb, Zn, and Cu and penalties from As and Fe (see Section 13 for a detailed description of the NSR model). Resources have been estimated from analyses of Ag, Pb, Zn, Cu, As, and Fe collected from diamond drilling, channel sampling, and long-hole production sampling. Samples have been selected and the block model has been defined by 35 mineral zone solids constructed via implicit modeling using a cut-off of US$20/t as a general guide. Grades have been estimated into the block model by grouping the 35 mineral solids into eleven estimation domains. Drill hole samples are composited to 2m, channel and production samples are independently declustered to a 4m cell size. Drill hole, channels and production samples have been globally capped, capped by datatype, and capped by estimation domain.

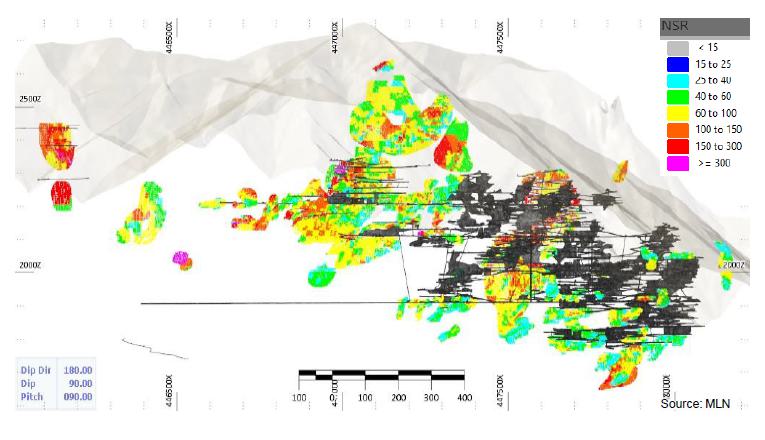

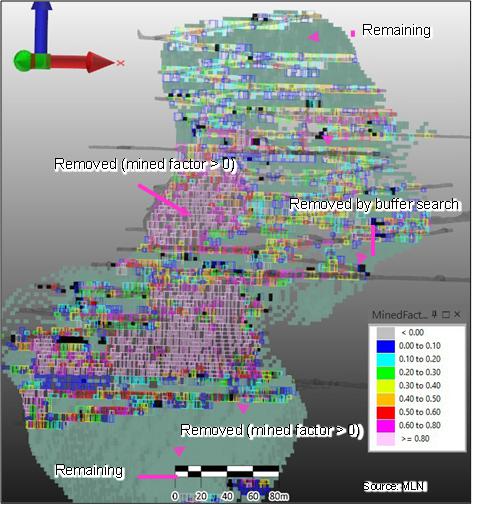

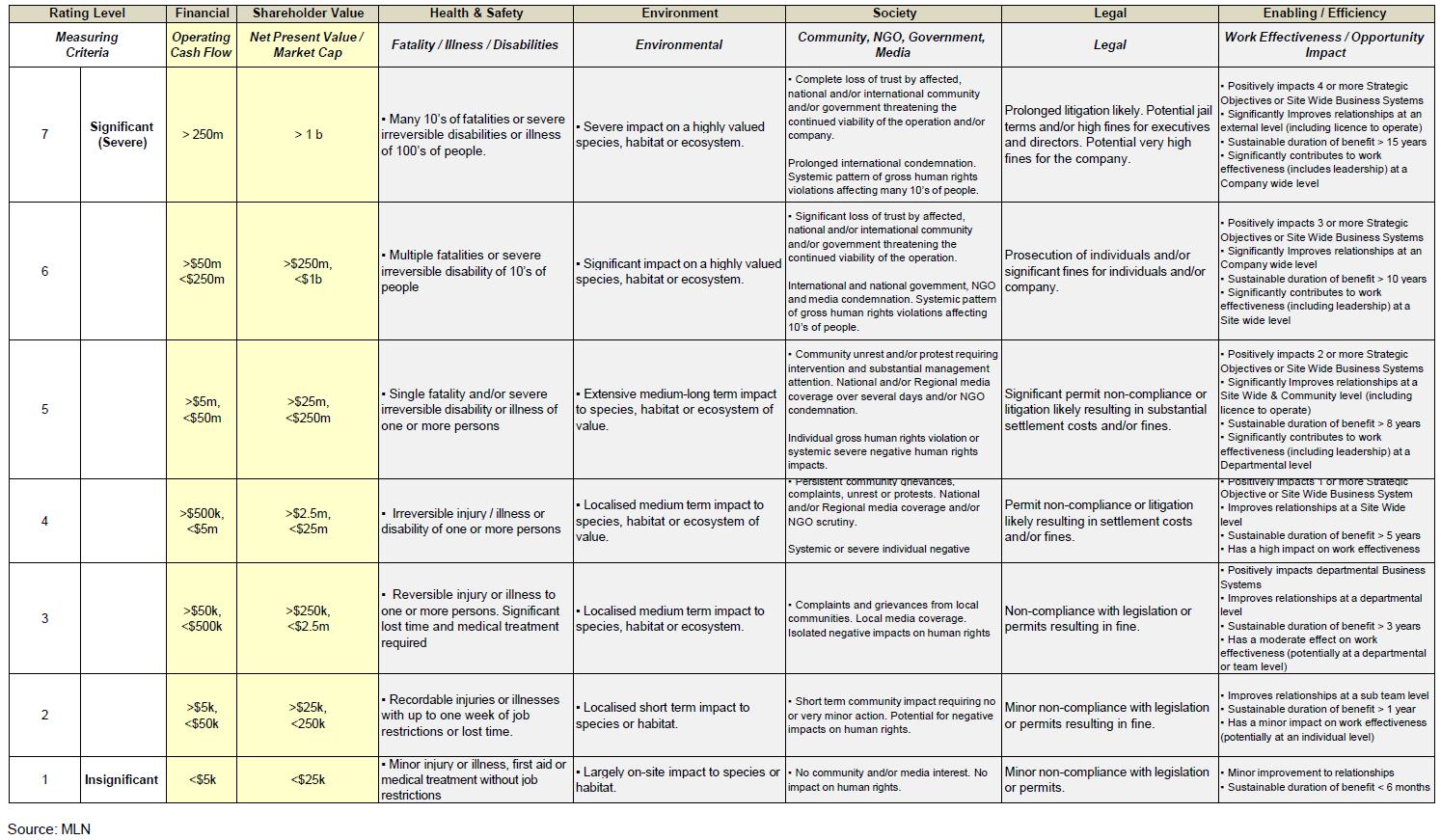

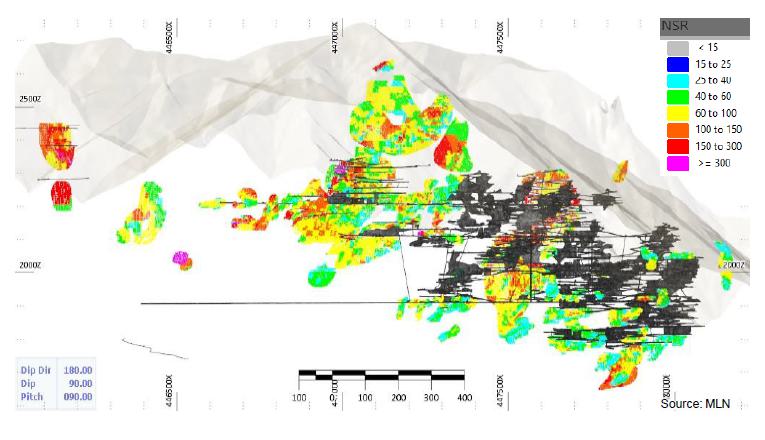

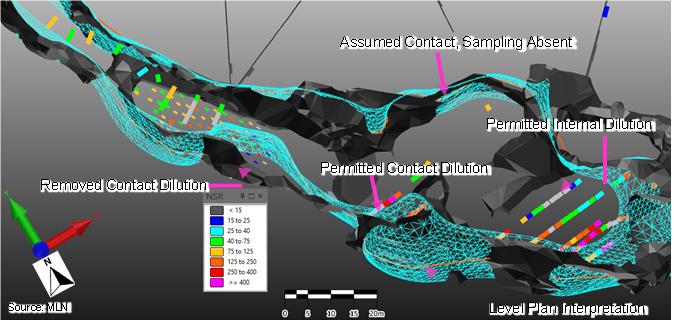

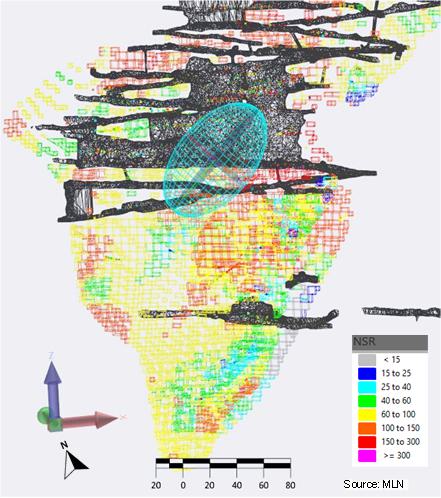

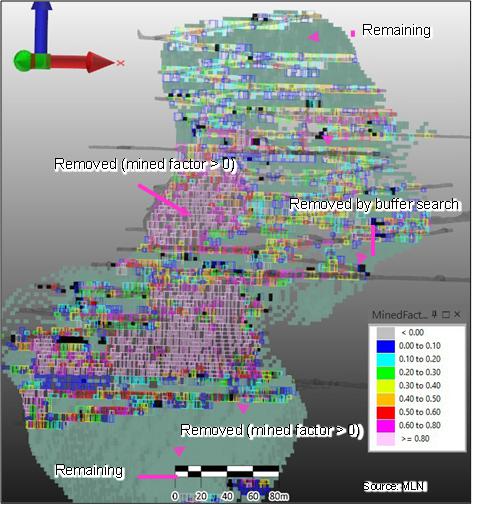

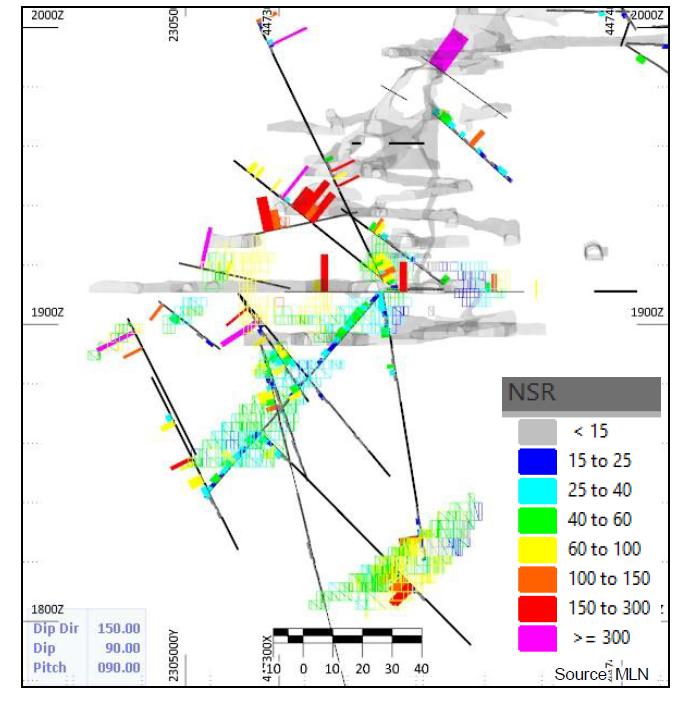

Figure 1.5 Mineral Solid Wireframes 3D Overview

Estimation employs: sample length weighting, three nested passes of 25, 50 and 80 meters, and sector declustering. Resource classification criteria account for: estimation pass range, distance to nearest sample, quantity of samples, sectors used, age and quality of data, type, and general reliability estimation. The block model has been depleted by existing mine cavities with an additional spatial buffer as well as manual removal of blocks near historic mining, no partially mined blocks are accounted for, and historically mined areas are mostly entirely removed from tabulation even if there are areas suspected to be remaining.

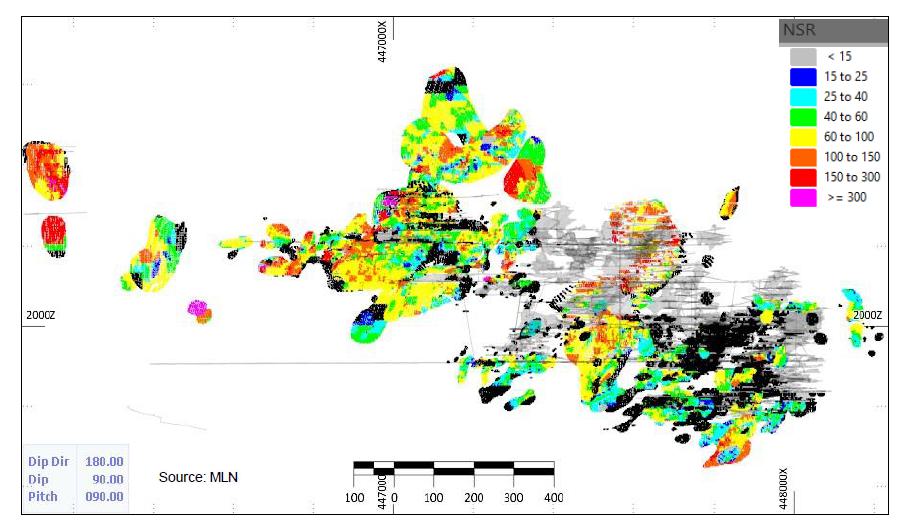

Figure 1.6 Overview Estimated Remaining Resources >US$28/t NSR (Looking North)

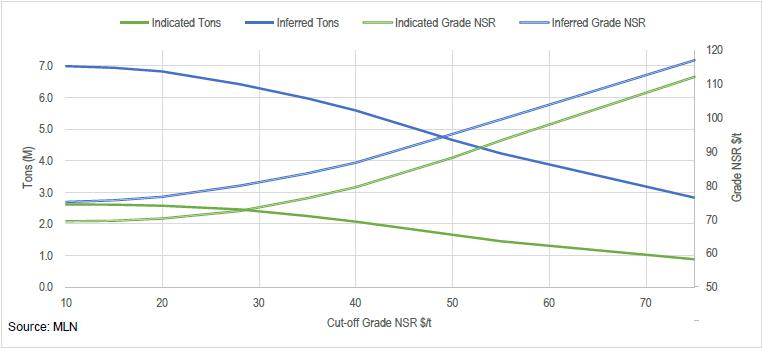

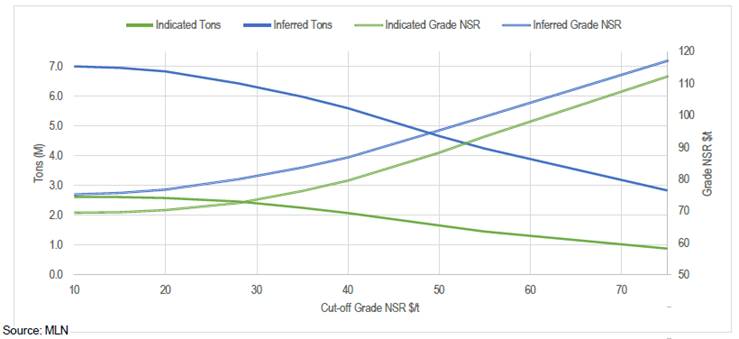

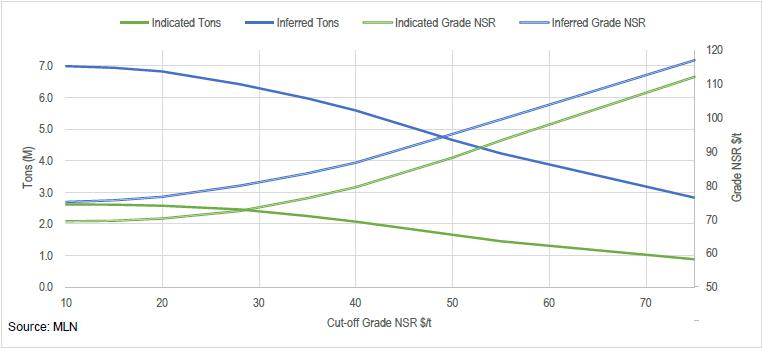

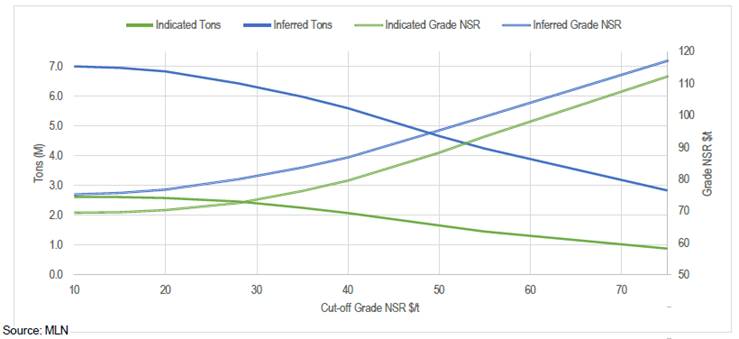

Mineral Resources are stated in the below table. Figure 1.6 is a grade tonnage curve of Indicated and Inferred Resources.

Table 1.1 La Negra Mineral Resource Statement at US$28/t NSR Cutoff

Classification | | Cutoff Grade US$NSR/t | | Tonnes

(M) | | Grade US$NSR/t | | Grade

Ag g/t | | Grade

Pb% | | Grade

Zn% | | Grade

Cu% |

| Indicated | | 28 | | 2.46 | | 73 | | 64 | | 0.27 | | 1.95 | | 0.50 |

| Inferred | | 28 | | 6.42 | | 80 | | 80 | | 0.65 | | 1.80 | | 0.40 |

Source: MLN

Mineral Resources are not Mineral Reserves and do not have demonstrated economic viability. Resources are stated as undiluted. There is no certainty that all or any part of mineral resources will be converted to Mineral Reserves. Inferred Mineral Resources are based on limited sampling with assumed geologic continuity which suggests the greatest uncertainty for resource estimation. Quantity and grades are estimates and are rounded to reflect the fact that the resource estimate is an approximation. Resources are undiluted. NSR includes the following price assumptions: Ag US$20.0/oz, Pb US$0.90/lb, Zn US$1.10/lb and Cu US$3.30/lb based on the Q3 2021 Q3 long-term forecasts provided by Duff & Phelps (D&P). NSR includes varying recovery with the averages of 80% Ag, 68% Pb, 80% Zn, and 66% Cu.

Figure 1.7 Mineral Resource Grade-Tonnage Curve

| 1.8 | Mineral Reserve Estimate |

No Mineral Reserves have been estimated as part of this study.

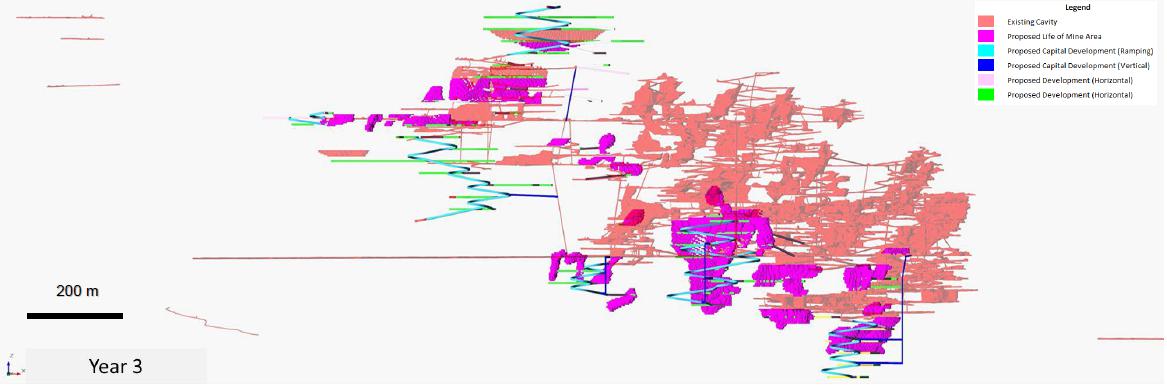

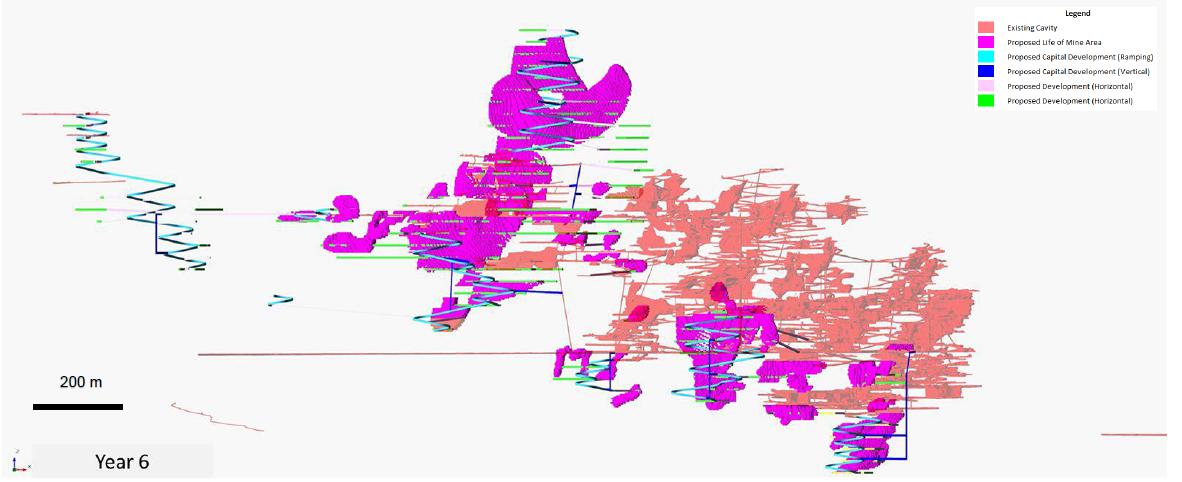

The mineralized zones that make up the La Negra project will be mined using as much of the existing mine infrastructure as possible, supplemented by new drift and ramp development, water handling and ventilation, as needed. Mining will take place with La Negra’s existing mining fleet, supplemented with new and some used equipment that is expected to be available as required to meet the mine plan, which is based on the production of 2,500 tonnes per operating day, or 842,500 tpa. Any additional equipment is included in the capital budget and includes a 20% contingency. Any additional development and equipment required is included in the project’s capital cost as described in 21.3. The mine plan envisions mining the zones corresponding to the mineralized bodies described in Section 14, with certain economic factors – such as mining recovery, dilution, capital and operating development, ventilation requirements, and operating costs – applied to these mineralized zones to present a reasonable prospect for economic extraction. This technical study does not present any Reserves (see Section 15).

All phases of mining, with the exception of haulage to surface, will be carried out by experienced La Negra personnel, with the latter being managed by a community-based contractor.

Each zone of mineralization was analyzed to determine the most optimum and practical mining method, which was then used along with the appropriate mine design criteria to develop a cut-off grade. As this is a PEA level study, all categories of resource were included in the optimization process.

For the purposes of the preliminary optimization, a mining cost of US$7.21/tonne mined was assumed for long-hole open stoping and was generated from first principles taking into account anticipated staffing levels, current wage levels plus anticipated bonuses, current equipment operating costs, and consumable costs from vendor quotation. An estimated development mining cost was also calculated at US$840 per m of advance, assuming a 4m x 4.5m drift size The cost of haulage from the mine to the crusher is US$1.18/tonne based on an active contract, which is carried out by a community-based contractor, is included in the mining cost quoted above. These costs are considered reasonable for this level of study and would be subject to revision and update as more detailed work is completed.

For the mining study the resource model was adjusted to account for expected mining dilution. Historically, dilution at La Negra has averaged 14%, for this study dilution of 15% has been accounted for.

Based on the parameters outlined in Section 16.11, as well as the first principle estimates of processing and G&A costs (see Section 22), a cutoff grade of US$28 per tonne was utilized for identifying potential mining areas.

| | 1.9.1 | Geotechnical Considerations |

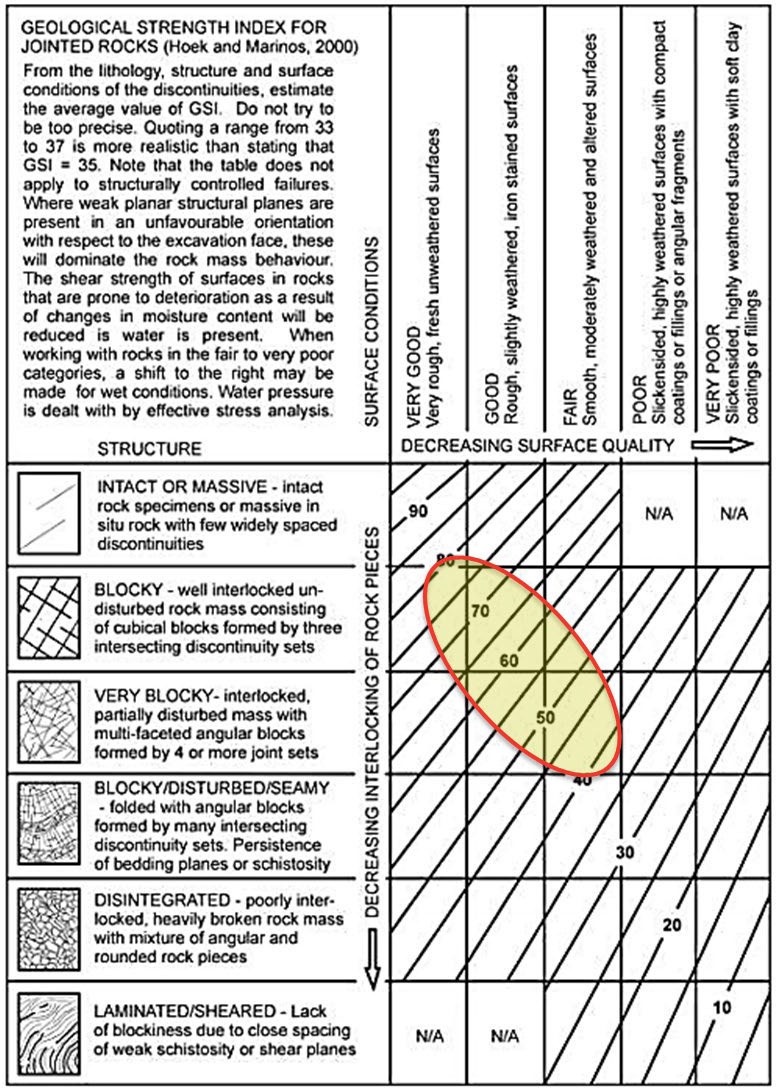

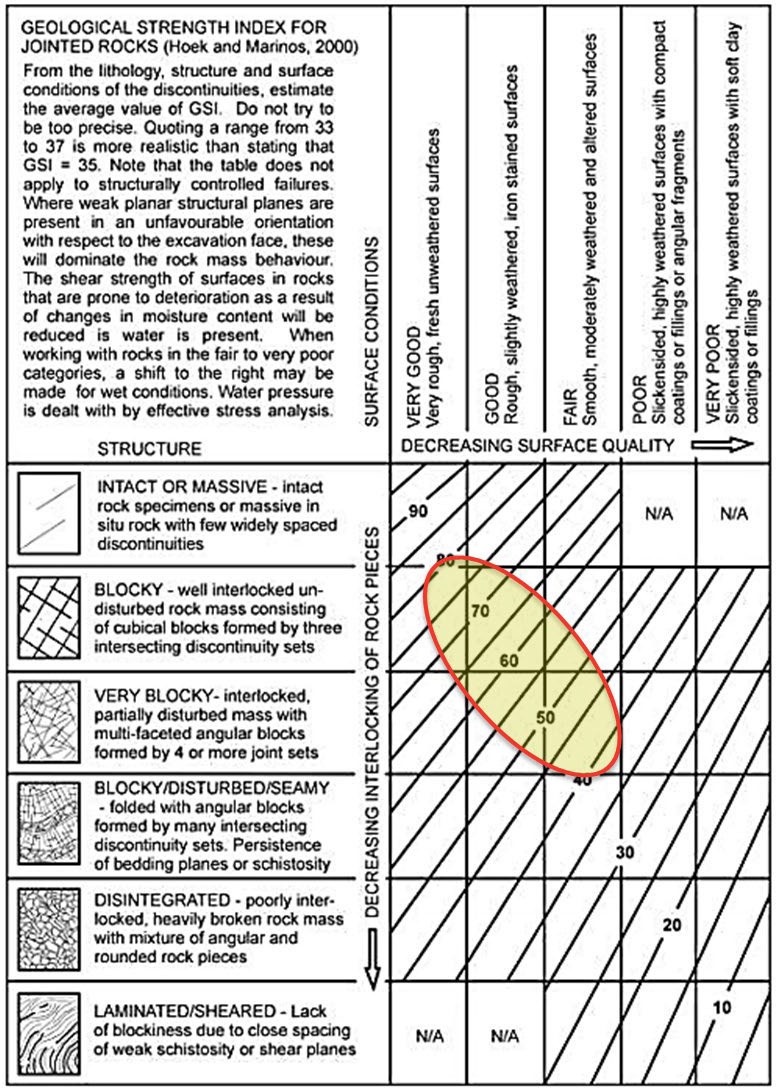

An initial geotechnical model suited to past operations was developed by A-Geommining in October of 2018. This work was considered by Mining Plus for this study. The mechanical properties for each mineralized zone were determined based on lithology and assigned a minimum, maximum and average Uniaxial Compressive Strength (UCS). Q-values (max, min, avg) were also determined for each zone for each lithology.

Based on site observations of the ground conditions at La Negra, the Geological Strength Index for the mine ranges between 40 and 80, with most of the readings between 60 and 75 and the lowest readings occurring only in faulted zones. This correlates very well with the Q values for the project as calculated by A-Geommining and reviewed by Mining Plus.

Excavation stability assessments were completed using industry-accepted empirical relationships, supported by historical experience. The rock mass conditions assessed in the range of Fair to Fair/Good or better are considered suitable for open stoping mining methods such as those that have been historically employed at La Negra. The ground conditions assessed within the Poor to Fair domain are considered adequate for open stoping methods, but with shorter length or width spans and with greater use of rib and sill pillars.

The recommended open stope geometry is 20 m long by 20 m high and 6 m wide, mined along the strike of the vein formation in a retreating sequence using a longitudinal orientation, although transverse mining will be considered in areas where the mineralization is greater than 6 m in width. Stability of the stope back is critical for maintaining stable mining conditions, and this design is expected to provide a factor of safety > 2.0.

Ground support design takes into consideration industry standard empirical guidelines and La Negra’s experience with varying ground conditions within the mine. Historically very little in the way of ground support has been required given the competence of the country rock, although rock bolts and mesh have been utilized occasionally in areas with poorer ground conditions.

This study does not consider the use of backfill. Scoping level trade-offs and geotechnical assessment did not require the use of backfill. The absence of backfill does however, reduce resource recovery and the potential to utilize backfill to maximize resource recovery should be further considered in conjunction with current plans to filter tailings and deposit them over top of the existing (and permitted) TSF5/TSF5A and TSF3 facilities.

| | 1.9.2 | Mine Design and Mining Methods |

The underground design for La Negra was based on industry-standard methodology for cut-off grade optimization, mine sequencing, and design at a scoping level. The main steps in the planning process are as follows:

| ● | Assignment of economic criteria to the geologic resource model |

| ● | Definition of optimization parameters such as net smelter return (“NSR”), preliminary cost estimates, resource extraction, dilution, and metallurgical recovery estimates for each mineralized zone |

| ● | Calculation of economic stope limits for the various zones using stope optimization software |

| ● | Establishment of an economic scheduling sequence |

| ● | Identification of stoping areas and preliminary designs and mining sequence incorporating ventilation requirements |

In recent history, two principal mining methods have been used at La Negra: long hole open stoping and mechanized room and pillar. While mechanized mining has predominated, some non- mechanized (jackleg mining) methods have been employed, primarily in the upper sections of the mine (i.e., above the main 2000 haulage level). Long-hole open stoping (LHOS) has been employed in areas where the mineralization is subvertical (but greater than 70 degrees to horizontal) while room-and-pillar was the method of choice for subhorizontal (but less than 30 degrees to horizontal) – and generally lower-grade – zones. Support pillars with dimensions of 8 by 8 meters were generally utilized in these zones.

The restart plan envisions utilizing a greater amount of long hole open stoping as the primary mining method, for the following reasons:

| ● | Ground conditions allow for the use of this method |

| ● | The mine staff are familiar with this method given its use over almost 50 years |

| ● | The mine fleet is suitable for this extraction method |

| ● | It allows for low-cost extraction |

| ● | It provides the future potential for efficient backfilling. |

Other variations of these mining methods will be considered in areas with poorer ground conditions, but only if such zones have a materially higher NSR, allowing for profitable extraction. The restart plan does not envision much use of jackleg mining for either stoping or development following the time when required initial slashing is complete.

The following criteria were used in the preparation of the production plan:

| ● | The production plan has been developed on a monthly time period basis for the life-of-mine |

| ● | The mine will operate six days per week, with the exception of statutory holidays, or approximately 310 days per year |

| ● | Production will be primarily by sub-level long hole open stoping |

| ● | The process plant is scheduled to operate 337 days per annum |

| ● | The process plant has a theoretical capacity of 3,000 tpd but will be operated at 2,500 tonnes per operating day |

The following table details the LOM production plan.

Table 1.2 LOM Production Schedule

| | | | | LOM | | Year 1 | | Year 2 | | Year 3 | | Year 4 | | Year 5 | | Year 6 | | Year 7 | | Year 8 |

| Tonnes to the mill | | (000’s Tonnes) | | 6,223 | | 843 | | 843 | | 843 | | 843 | | 843 | | 843 | | 843 | | 326 |

| Production and Throughput | | (tpd) | | 2,500 | | 2,500 | | 2,500 | | 2,500 | | 2,500 | | 2,500 | | 2,500 | | 2,500 | | 2,500 |

| Ag Grade | | (g/t) | | 63 | | 47 | | 53 | | 62 | | 63 | | 63 | | 55 | | 81 | | 96 |

| Pb Grade | | (%) | | 0.4 | | 0.2 | | 0.2 | | 0.5 | | 0.5 | | 0.5 | | 0.3 | | 0.7 | | 0.8 |

| Zn Grade | | (%) | | 1.5 | | 1.3 | | 1.4 | | 1.8 | | 1.6 | | 1.7 | | 1.6 | | 1.3 | | 1.4 |

| Cu Grade | | (%) | | 0.4 | | 0.4 | | 0.5 | | 0.3 | | 0.3 | | 0.3 | | 0.4 | | 0.3 | | 0.4 |

| Fe Grade | | (%) | | 8.6 | | 9.8 | | 8.9 | | 8.6 | | 8.2 | | 8.2 | | 8.7 | | 8.7 | | 6.3 |

| As Grade | | (%) | | 0.7 | | 0.6 | | 0.8 | | 0.8 | | 0.6 | | 0.7 | | 0.7 | | 0.4 | | 0.4 |

Source: MLN

The underground mining activities at La Negra will be carried out with conventional equipment typical of smaller-scale underground mines, including single-boom drilling jumbos for drift and ramp access, (“simba”) production drills for stope preparation, and scoop trams for mucking. The scoops are diesel fueled but the jumbos and production drills are electric. The existing fleet is detailed in 16.7.5.

La Negra historically relied on small, 2.5 and 3.5 cuyd scoop trams for mucking, but as the operation grew the smaller equipment was replaced with 4.0 and 6.0 cuyd scoops. Until the recent shutdown the smaller scoops were used in those areas with smaller headings but the redevelopment plan assumes that the smaller equipment will only be utilized as needed to help slash out the smaller headings and will then be retired.

Haulage from the loading pockets to the surface stockpile area outside the 2000 Level portal has historically been carried out by a community-based contractor utilizing 23 tonne trucks. This study assumes this arrangement will continue. The cost of contractor haulage is included in mining costs albeit shown as a separate line item.

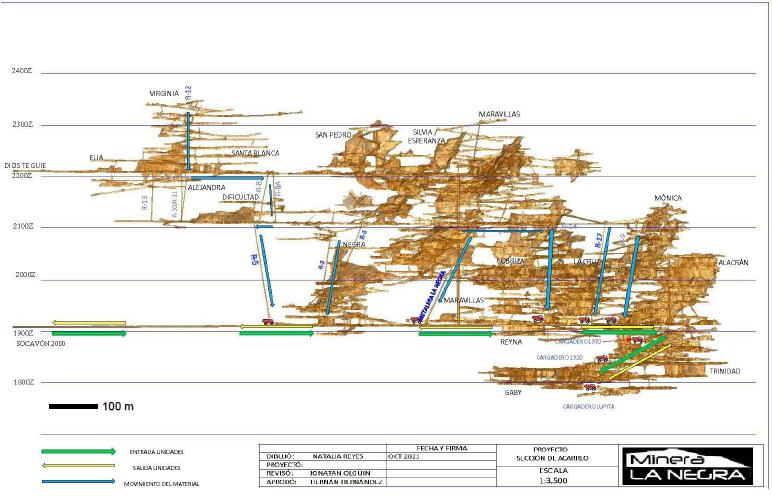

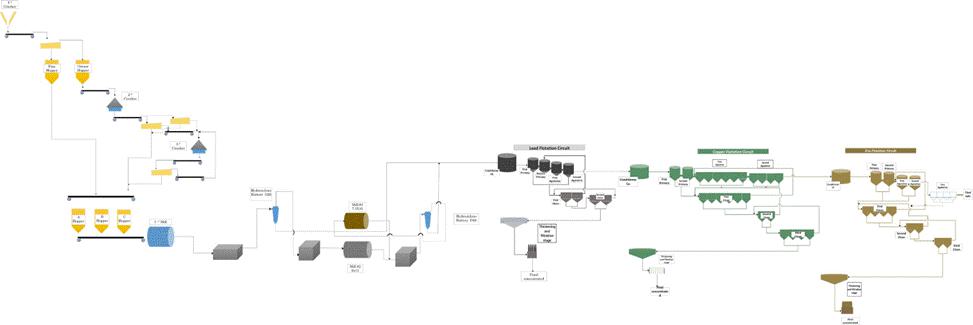

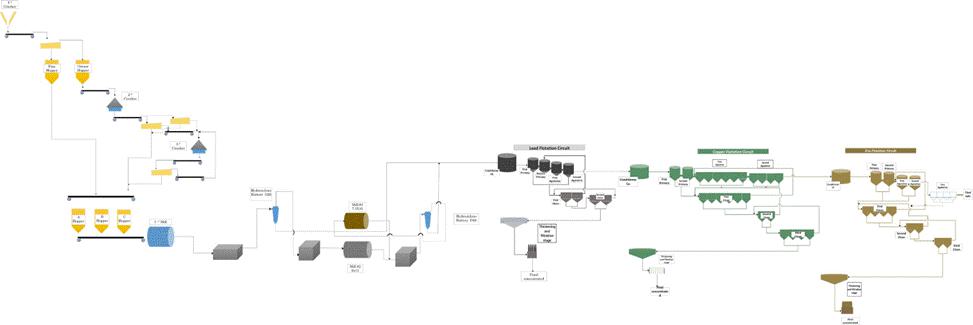

The processing facility at Minera La Negra consists of a standard crushing, grinding, flotation, and filtration circuit producing lead-silver, copper-silver, and zinc concentrates (in that order). The concentrator has an operating capacity of 3,000 tonnes per day but is estimated in this document to be operated at a rate of 2,500 tpd after restart.

The crushing circuit consists of a 25” x 42” jaw crusher, followed by secondary and tertiary crushing with Symons 5 ½ ft standard and shorthead cone crushers, respectively, to produce a product with a p80 of 5/16”. The material is conveyed to three fine ore storage bins with a capacity of 450 tonnes each. The grinding circuit consists of two parallel ball milling lines. The first consists of a 10’ x 10’ ball mill in a single grinding stage arrangement, while the second line consists of two ball mills, 9’ x 11’ and 7.5’ x 11’, in a two-stage milling arrangement, producing a p80 of 75μ.

The flotation circuit consists of three stages of flotation to recover lead, copper, and zinc concentrates, in that order. A variety of reagents are added throughout the process to maximize the recovery of the targeted metal, while suppressing unwanted materials such as iron and arsenic. The lead recovery circuit consists of four 350 ft3 Outotec rougher flotation cells and four 50 ft3 Denver scavenger/cleaner flotation cells. Sodium cyanide and zinc sulfate are added during the grinding stage to depress pyrite, arsenic and copper and zinc minerals, and AERO 7583 is added as a lead collector while CC1064 is added as a frother.

The copper recovery circuit consists of 10 160 ft3 Denver flotation cells. Ammonium bisulfite is added as a pH modifier and Zn and Fe depressor, while S-7583 is added as a copper collector and CC1064 is added as a frother. Depending on the copper minerals sodium isopropyl xanthate is also added as a collector.

The zinc recovery circuit consists of four Denver 160 ft3 rougher flotation cells and four Denver 160 ft3 cleaner flotation cells. Lime is added as a pH modifier and copper sulfate is added to activate the zinc minerals. Aero 5160 is added as a collector, while CC1064 is added as a frother.

The concentrates are thickened and filtered to a moisture content of 10-12% with LOM concentrate grades of 60.2% Pb and 8,362 g/t Ag for the Pb-Ag concentrate, 44.1% Zn and 70 g/t Ag for the Zn concentrate, and 23.9% Cu and 1,740g/t Ag for the copper concentrate. See Table 1.2.

La Negra has a fully equipped laboratory to perform sample preparation and assays by ICP, atomic absorption and fire assay. The laboratory carries out assays for both exploration and concentrate samples.

Table 1.3 Minera Negra NSR Model

| | | Ag | | Pb | | | Zn | | | Cu | | | Fe | | | As | |

| Material Grade | | 63 | | 0.46 | % | | 1.51 | % | | 0.35 | % | | 8.78 | % | | 0.71 | % |

| Gross Recovery (%) | | 79.7 | | 72.3 | | | 84.0 | | | 68.0 | | | | | | | |

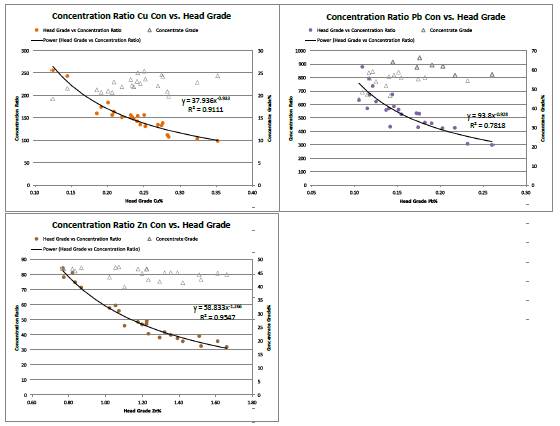

| Concentration Ratio | | | | 193.1 | | | 34.5 | | | 99.9 | | | | | | | |

| | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | |

| Concentrate Grade | | | | Pb | | | Zn | | | Cu | | | | | | | |

| Moisture (%) | | | | 11.1 | | | 12.2 | | | 10.2 | | | | | | | |

| Ag (g/t) | | | | 8,362 | | | 156 | | | 1,740 | | | | | | | |

| Pb (%) | | | | 60.2 | | | 0.2 | | | 2.4 | | | | | | | |

| Zn (%) | | | | 1.3 | | | 49.2 | | | 6.7 | | | | | | | |

| Cu (%) | | | | 0.0 | | | 0.0 | | | 23.9 | | | | | | | |

| Fe (%) | | | | 0.0 | | | 15.0 | | | 0.0 | | | | | | | |

| As (%) | | | | 0.63 | | | 0.00 | | | 0.38 | | | | | | | |

| Sb (%) | | | | 1.2 | | | 0.00 | | | 0.03 | | | | | | | |

| Cd (ppm) | | | | 0.0 | | | 0.42 | | | 0.00 | | | | | | | |

| Bi (%) | | | | 2.0 | | | 0.00 | | | 0.00 | | | | | | | |

| SiO2 (%) | | | | 0.0 | | | 0.00 | | | 0.00 | | | | | | | |

| Cl (ppm) | | | | 0.0 | | | 0.00 | | | 0.00 | | | | | | | |

| F (ppm) | | | | 0.0 | | | 0.00 | | | 0.00 | | | | | | | |

| | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | |

| Payability | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | |

| Ag (%) | | | | 95%/50g/t ded | | | 70%/100g/t ded | | | 90%/31g/t ded | | | | | | | |

| Pb (%) | | | | 95%/3% ded | | | 0.0 | | | 0.0 | | | | | | | |

| Zn (%) | | | | 0.0 | | | 85%/8 % ded | | | 0.0 | | | | | | | |

| Cu (%) | | | | 0.0 | | | 0 | | | 96.5%/1% ded | | | | | | | |

| | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | |

| Deductions | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | |

| Treatment Charge (US$/t) | | | | 97 | | | 150 | | | 75 | | | | | | | |

| Treatment Charge Escalation (US$/t) | | | | 0 | | | 0.12 > 1900/t | | | 0 | | | | | | | |

| Refining Charge Ag (US$/oz) | | | | 0.75 | | | 0.0 | | | 0.75 | | | | | | | |

| | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | |

| Penalties | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | |

| As (US$/t) | | | | 0 | | | 0 | | | 2.5 > 0.2 | % | | | | | | |

| Sb (US$.t) | | | | 0 | | | 0 | | | 2.5 > 0.1 | % | | | | | | |

| Pb+Zn (US$/t) | | | | 0 | | | 0 | | | 2.5 > 2.0 | % | | | | | | |

| Fe (US$/t) | | | | 0 | | | 2.5 > 5 | % | | 0.0 | | | | | | | |

| As+Sb (US$/t) | | | | 2.5 > 0.3 | % | | 0.0 | | | 0.0 | | | | | | | |

| Zn (US$/t) | | | | 2 > 5.0 | % | | 0.0 | | | 0.0 | | | | | | | |

| F+Cl (US$/t) | | | | 2.00 > 500ppm | | | 0.0 | | | 0.0 | | | | | | | |

| | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | |

| NSR (US$/t) | | | | 72.2 | | | | | | |

Source: MLN

The infrastructure in and around Minera La Negra is fairly standard. The mine has access from the state capital city of Querétaro through a paved road to the town of Maconí. The last stretch to the plant site is via a well-maintained, year-round, 3.4 km long gravel road. Although it narrows to one lane locally it can handle all heavy equipment.

San Joaquín is the largest town close to Maconí, located 21 km to the north, with better services than Maconí. Local schooling is provided at Maconí through primary level, while San Joaquin provides secondary and high school equivalent levels. For technical and higher-level education, local people attend schools at Cadereyta, Ezequiel Montes or Querétaro.

Available transportation is limited to a private bus service from San Joaquín to Querétaro and other localities.

Electrical power is obtained from the national grid through a 34 kilovolt (kV) line to the process plant and mine facilities. Occasionally, power is delivered directly from the Ezequiel Montes sub-station. Electrical power is transformed at MLN’s substation to 6.9 kV to be distributed to the process plant and mine facilities at 440 volts.

The site has both fixed land lines and satellite internet. Cellular phone service at the mine site and in the area around Maconí is limited.

Water for domestic sources comes from the Maconí River. Water for industrial purposes is obtained from several sources: water used within the mine is obtained from the small amount of surface rain and run-off water that infiltrates the mine; this water is recirculated from the lower levels using pumps to lift it to where it is needed. Historically, approximately 70% of the water used in the mill operation is recirculated from the tailings storage facility and the remaining 30% makeup water is obtained from the San Nicolás water well. With the planned introduction of filtered tailings, it is estimated that 90% of the water used in the plant will be recycled.

| 1.12 | Environment and Social Impact |

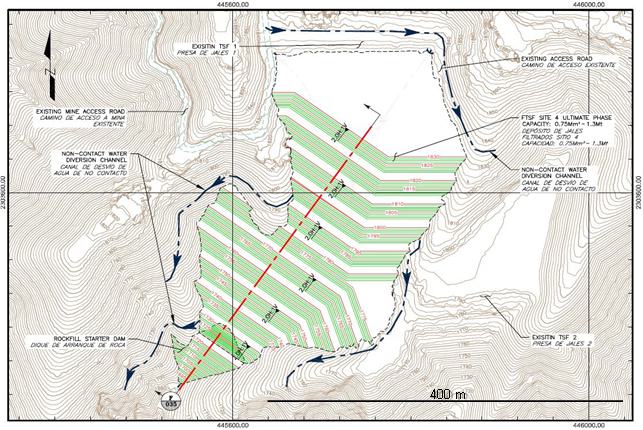

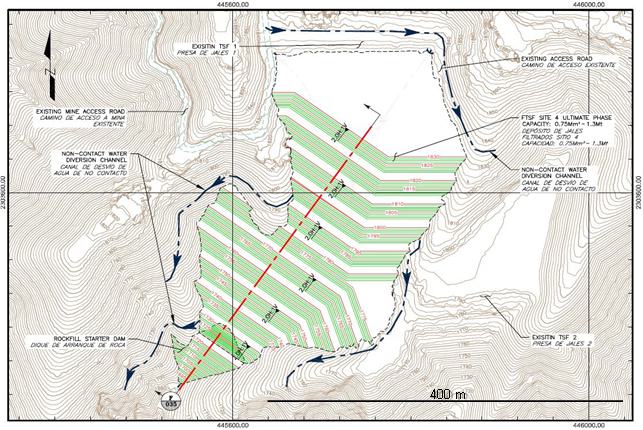

Minera La Negra has all the permits required to restart operations.

Minera La Negra operates under three separate environmental impact statements (Manifestación de Impacto Ambiental – MIA), two of which are currently valid and in effect. The third is for the TSF5 facility which is no longer in use. The initial MIA was issued for the mine, mill, and the original tailings facility. A second MIA was issued for the development of TSF5 (Tailings Storage Facility 5), and the third was an amendment that allowed the expansion of TSF 5, known as TSF5A.

These studies considered the impact of the operation on the environment and the social impact of the project. The area affected by the project is located in a region that had experienced significant historical impact, including past mining operations dating back to the pre-Columbian era as well as other human activities stretching back for hundreds of years.

The following table lists the key operating and environmental permits issued to Minera La Negra, and which allow the mine to engage in mining, processing, and tailings storage. MLN has all the permits required for startup.

Table 1.4 Minera La Negra Permits

| License/Permit | | Agency | | Document Number | | Status |

| Operating License | | SEMARNAT | | No. 0168 / 130.25 I. SE469, 27 | | Valid |

| Environmental License | | SEMARNAT | | LAU-22 / 000004-2016 | | Valid |

Environmental Impact Statement (MIA) Mine, Plant and Tailings | | SEMARNAT | | F.22.01.01.01/1882/17 | | Valid |

| Environmental Impact Statement (MIA) TSF5 | | SEMARNAT | | D.O.O. - 04853 | | Expired* |

| Environmental Impact Statement (MIA) TSF5A | | SEMARNAT | | F.22.01.01.01/1533/16 | | Valid |

| Environmental Impact Statement (MIA) Settling Pond | | SEMARNAT | | F.22.01.01.01/0070/2020 | | Pending |

| Hazardous Waste Register | | SEMARNAT, CONAGUA, STPS, SSC, SDS and municipal authorities | | 22/EV-0040/10/18 | | Valid |

| Land Rezoning | | SEMARNAT, CONAGUA, STPS, SSA, SDS | | SRN/280/98 | | Valid |

| Federal Water Use Permit | | CONAGUA | | QRO100564 | | Valid |

| Wastewater Discharge Permit | | CONAGUA | | 09QRO106300/26EDDL12 | | Valid |

| Waste Use Permit | | SEMARNAT, CONAGUA | | 2S.3.21/00051-2020 | | Valid |

| Organic Residue Permit | | SEDESU | | - | | Valid |

| Hazardous Waste Management Plan | | SEMARNAT | | 22-PMG-I-3478-2019 | | Valid |

| Special Waste Management Plan | | SEDESU | | - | | Pending |

| TSF5A Closure Plan | | SEMARNAT | | - | | Pending |

| Explosives Permit | | SEDENA | | 3121-Qro. | | Valid |

Source: Minera La Negra. *Not required for operations

There are 21 communities in the vicinity Minera La Negra and which together belong to the Comunidad Agraria Maconí. The largest of these is Maconí, with a population of over 900, but the majority consist of small communities with a population of less than 100 inhabitants, and the total population near the mine totals approximately 3,000 individuals. The location of these communities relative to Minera La Negra’s infrastructure is shown in Figure 1.4.

The project footprint consists of approximately 51 ha and constitutes the areas that are directly disturbed by existing infrastructure and earthworks, in addition to those that are projected as part of the longer-term operation of the mine.

Minera La Negra has developed a series of plans which outline its commitment to environmental and social management, monitoring and mitigation, and includes health and safety, security, environmental plans, and stakeholder engagement. These plans are reviewed and updated periodically, and will consider internal and external comments, stakeholder feedback, and third-party reviews, and of course any potential regulatory changes.

The following management plans have been developed and implemented:

| ● | Stakeholder Engagement Plan (Plan de Recuperación del Tejido Social) |

| ● | Occupational Health and Safety Plan (Programa de Seguridad e Higiene Industrial) |

| ● | Emergency Preparedness and Spill Response Plan (Plan de Contingencias por Residuos Peligrosos) |

| ● | Emergency Preparedness Plan (Programa Interno de Protección Civil) |

| ● | Transport Management Plan (Plan Interno de Seguridad Vial) |

| ● | Cyanide Management Plan (Procedimiento para el Manejo de Cianuro) |

| ● | Reagent Management Plan (Plan Específico de Seguridad e Higiene para el Manejo, Transporte y Almacenamiento de Sustancias Químicas Peligrosas) |

| ● | Solid Waste Management Plan (Plan de Manejo de Residuos Peligrosos) |

| ● | Air Quality and Noise Management Plan (Plan Anual de Protección y Conservación Atmosférica) |

| ● | Dust Management Program (included in Plan Anual de Protección y Conservación Atmosférica) |

| ● | Surface Water Management Plan (Plan Anual de Protección de Agua Superficial) |

| ● | Soil and Tailings Management Plan (Plan Anual para la Protección y Conservación de Suelos) |

| ● | Biodiversity Management Plan (Programa para el Rescate y Reubicación de Vegetación Forestal and Programa de Acciones para la Protección de la Fauna) |

| ● | Physical and Property Security Plan (Plan de Seguridad Patrimonial) |

| ● | Cultural and Archeological Protection Plan (Plan de Protección al Patrimonio Cultural, Paleontológico y Prehispánico) |

| ● | Mine Closure Plan (Guía para la Elaboración del Plan de Cierre de Mina y Planta de Beneficio) |

| ● | TSF5 Closure Plan (Plan de Obra Cierre del Depósito de Jales No. 5) |

| ● | TSF5A Closure Plan (Plan de Cierre de Depósito de Jales Proyecto Ampliación del Depósito de Jales no. 5) |

| ● | TSF Emergency Management Plan (Plan de Atención a Emergencias Depósito de Jales) |

Minera La Negra is located on land belonging to an agrarian community named Comunidad Agraria Maconí. This is not to be confused with a common form of communal land ownership unique to Mexico known as the ejido although in practice there are minimal differences between an ejido and an agrarian community.

Based on the latest agrarian census by Mexico’s statistics agency, INEGI, completed in 2020, there are 29,793 ejidos in Mexico covering an area of just over 82.2 million ha, compared with 2,354 agrarian communities covering just over 17.5 million ha. For the state of Querétaro the comparative figure is 364 ejidos covering 0.48 million ha and 16 agrarian communities covering 58,288 ha.

The benefits and/or payments that the third party provides to the community are known as the usufructo, and the agreement between the Comunidad Agraria and the third party is known as the Contrato de Usufructo por la Ocupación Temporal de Tierras Comunales. Following Peñoles’ sale of the property, a new 15-year usufructo was entered into between the community and Minera La Negra on July 18th 2006, covering an area of 42.5 ha. This agreement was later amended the 16th of February of 2016 following a series of negotiations that commenced in late 2014 designed to address certain grievances by the community with respect to the original agreement. The area covered by the usufructo was increased to 51.0 ha to allow for the construction of TSF 5A.

The latest amendment to the usufructo was completed in October 2021 and amends the terms of the agreement that expired on 18 July 2021. The agreement is valid for 15 years and covers the same 51.0 ha. In addition to the annual land payment, Minera La Negra has agreed to carry out certain infrastructure projects of importance to the community once the project is fully in production.

The company is subject to inspections and audits by several government agencies. At the Federal level the water agency CONAGUA inspects the site one to two times per year, while Profepa (Procuraduría Federal de Protección al Ambiente) which is the enforcement agency of SEMARNAT, inspects the mine three to four times per year.

At the State level Minera La Negra is subject to inspections by the sustainable development agency SEDESU (Secretaría de Desarrollo Sustentable) and by the State water commission CEA (Comisíon Estatal del Agua). Each of these agencies inspects the company on average once per year.

The municipality of Cadereyta de Montes also inspects the mine once to twice per year.

Proper closure preparation is important to ensure that a mining project will have a positive impact on a community or region. Minera La Negra’s closure and reclamation goals are as follows:

| ● | Future public health and safety are not compromised |

| ● | Environmental impacts are minimized and environmental resources in the region are not subject to additional deterioration over time |

| ● | Post-closure use of the site is beneficial and sustainable and acceptable to the community and regulators |

| ● | Adverse impacts on the local community is minimized |

| ● | Socioeconomic benefits are maximized |

| ● | Closure and rehabilitation are funded by MLN |

In accordance with Mexico’s regulatory requirements, a series of closure plans for La Negra were developed for each of the company’s MIAs. The closure plan for TSF5 was developed in July 2019 by MLN in accordance with Mexico’s mining law (Ley Minera) and in accordance with SEMARNAT regulations NOM-141-SEMARNAT-2003 and NOM-147-SEMARNAT/SSA1-2004. That same year the company developed the closure plan for TSF5A. Preliminary closure and rehabilitation costs including engineering planning and environmental monitoring were developed by Minera La Negra. A summary of the costs developed for this study are included in Chapter 21.

| 1.13 | Capital Cost Estimate |

The total estimated cost required to restart La Negra includes the cost of refurbishing the existing mining fleet and purchasing certain additional new and used equipment, as well as advancing mine development, partial refurbishment of process lines within the processing plant, a new filtered tailings facility, first fills, and owner’s costs. Subject to further revisions as plan updates or details emerge, these costs are considered reasonable for this level of study.

Capital cost estimates are based on a combination of prices and quotations provided by equipment suppliers and estimates provided by Minera La Negra personnel based on historic operating experience. The following table (Table 1.5) summarizes the initial and sustaining capital cost estimate.

Table 1.5 LOM Capital Cost Estimate

| Description | | Restart Capital (US$m) | | | Sustaining Capital (US$m) | | | Closure (US$m) | | | LOM Total (US$m) | |

| Processing Plant | | 2.41 | | | 2.38 | | | - | | | 4.79 | |

| TSF | | 13.55 | | | 4.11 | | | - | | | 17.66 | |

| Underground Development | | 0.57 | | | 18.18 | | | - | | | 18.75 | |

| Equipment Replacement/Refurb | | 0.46 | | | 12.31 | | | - | | | 12.77 | |

| Indirect Costs | | 2.03 | | | - | | | - | | | 2.03 | |

| Owner’s Costs | | 1.63 | | | - | | | - | | | 1.63 | |

| Capitalized Exploration | | 0.29 | | | 4.57 | | | - | | | 4.85 | |

| Other | | - | | | 0.58 | | | - | | | 0.58 | |

| Closure | | - | | | - | | | 5.00 | | | 5.00 | |

| Total Capital | | 20.94 | | | 42.13 | | | 5.00 | | | 68.06 | |

Source: MLN, Mining Plus, Wood

The underground development required for restart was developed with the support of Mining Plus, while the costs for the development of a filtered tailings plant were developed with the support of Wood.

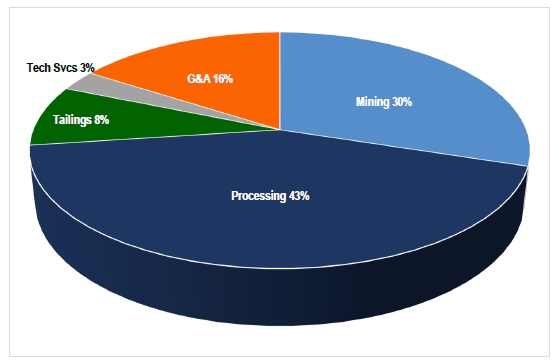

| 1.14 | Operating Cost Estimate |

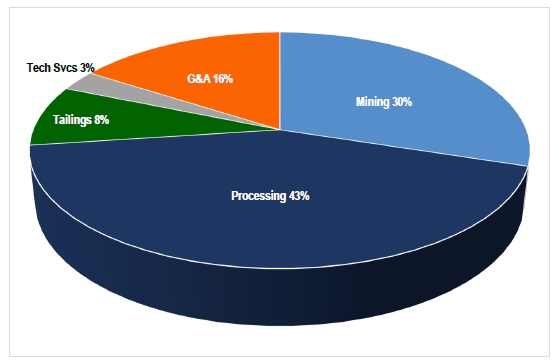

The life-of-mine (LOM) operating costs for La Negra average US$28.00/tonne and include the following:

| ● | Mining |

| ● | Processing |

| ● | Tailings |

| ● | Technical Services |

| ● | General and Administrative Costs |

The cost per tonne milled is based on an annual processing rate of 842,500 tonnes (2,500 tonne per operating day). These costs are considered to be reasonable for this level of study.

The LOM operating cost excludes offsite costs such as treatment charges, refining charges, other concentrate penalties/losses, and concentrate transportation. As described in Sections 13, 19, and 22 these costs are included in the NSR for each of the concentrates.

Table 1.6 Life of Mine and Annual Operating Cost Summary

| Operating Costs | | LOM Cost US$m) | | | Annual Cost (US$m) | | | US$/t milled | |

| Mining | | | | | | | | | | | | |

| Payroll (Staff and Union) | | | 13,377,067 | | | | 1,803,650 | | | | 2.15 | |

| Diesel | | | 14,119,966 | | | | 1,903,816 | | | | 2.27 | |

| Haulage | | | 7,365,608 | | | | 993,116 | | | | 1.18 | |

| Mine Services | | | 4,359,212 | | | | 587,759 | | | | 0.70 | |

| Drill Steel | | | 3,677,070 | | | | 495,785 | | | | 0.59 | |

| Explosives | | | 3,433,317 | | | | 462,919 | | | | 0.55 | |

| Mechanical Maintenance | | | 2,903,624 | | | | 391,500 | | | | 0.47 | |

| Tools | | | 1,337,625 | | | | 180,354 | | | | 0.21 | |

| Safety | | | 659,493 | | | | 88,920 | | | | 0.11 | |

| Electrical Maintenance | | | 238,197 | | | | 32,116 | | | | 0.04 | |

| Spare Parts | | | 491,390 | | | | 66,255 | | | | 0.08 | |

| Gasoline | | | 215,770 | | | | 29,093 | | | | 0.03 | |

| Other | | | 42,066 | | | | 5,672 | | | | 0.01 | |

| Total Mining Costs | | | 52,220,404 | | | | 7,040,953 | | | | 8.39 | |

| Processing | | | | | | | | | | | | |

| Reagents | | | 26,855,799 | | | | 3,621,007 | | | | 4.32 | |

| Labor (Staff and Union) | | | 13,730,764 | | | | 1,851,339 | | | | 2.21 | |

| Power | | | 13,035,814 | | | | 1,757,638 | | | | 2.09 | |

| Maintenance | | | 10,798,238 | | | | 1,455,942 | | | | 1.74 | |

| Spare Parts | | | 5,275,250 | | | | 711,270 | | | | 0.85 | |

| Haulage | | | 2,314,997 | | | | 312,134 | | | | 0.37 | |

| Make-up Water | | | 713,474 | | | | 96,199 | | | | 0.11 | |

| Lab | | | 1,079,044 | | | | 145,489 | | | | 0.17 | |

| Fuel and Lubricants | | | 887,969 | | | | 119,726 | | | | 0.14 | |

| Construction Materials | | | 192,976 | | | | 26,019 | | | | 0.03 | |

| Tools | | | 77,768 | | | | 10,486 | | | | 0.01 | |

| Other | | | 144,981 | | | | 19,548 | | | | 0.02 | |

| Safety Equipment | | | 34,849 | | | | 4,699 | | | | 0.01 | |

| Total Processing Costs | | | 75,141,922 | | | | 10,131,495 | | | | 12.07 | |

| Tailings | | | 14,597,557 | | | | 1,968,210 | | | | 2.35 | |

| G&A | | | | | | | | | | | | |

| Labor (Staff and Union) | | | 5,869,902 | | | | 791,448 | | | | 0.94 | |

| Outside Service Providers | | | 7,208,736 | | | | 971,964 | | | | 1.16 | |

| Insurance | | | 5,119,466 | | | | 690,265 | | | | 0.82 | |

| Mining Concessions/Community | | | 4,048,782 | | | | 545,903 | | | | 0.65 | |

| Environmental | | | 2,887,820 | | | | 389,369 | | | | 0.46 | |

| Safety/Security | | | 1,664,406 | | | | 224,414 | | | | 0.27 | |

| Supplies/Other | | | 545,057 | | | | 73,491 | | | | 0.09 | |

| Accommodations and catering | | | 443,474 | | | | 59,794 | | | | 0.07 | |

| Total G&A | | | 27,787,644 | | | | 3,746,649 | | | | 4.47 | |

| Technical Services | | | 4,975,345 | | | | 670,833 | | | | 0.80 | |

| | | | | | | | | | | | | |

| Total Operating Cost | | | 174,722,872 | | | | 23,558,140 | | | | 28.08 | |

Source: MLN

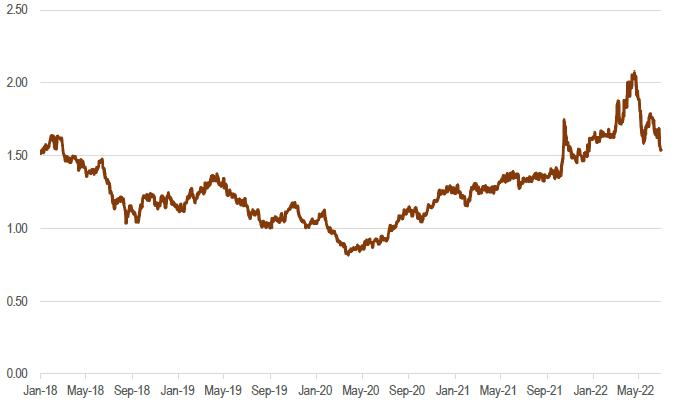

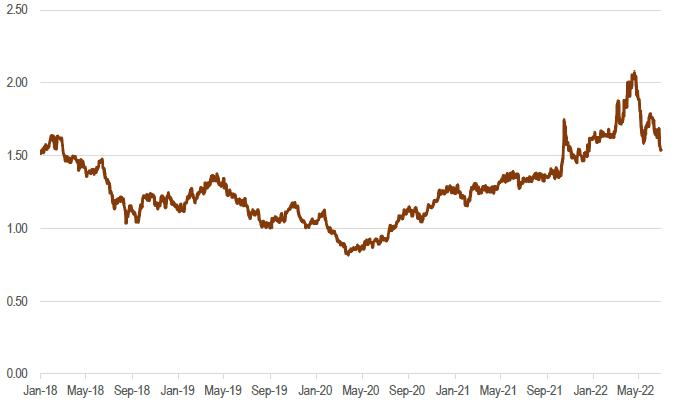

Table 1.7 outlines the metals prices and foreign exchange (FX) assumptions used in the economic analysis. Mine revenue will be derived from the sale of lead-silver, zinc, and copper-silver concentrates that will be sold to concentrate offtakers in the domestic and/or international markets. Although MLN has historically operated under offtake contracts with various offtakers there are currently no contractual arrangements.

Table 1.7 Commodity Price and FX Assumptions

| Commodity | | | Unit | | | Year 1 | | | Year 2 | | | Year 3 | | | Year 4 | | | Year 5 | | | Year 6 | | | Year 7 | | | Year 8 | |

| Silver | | | US$/oz | | | | 22.50 | | | | 22.50 | | | | 22.13 | | | | 22.00 | | | | 22.00 | | | | 22.00 | | | | 22.00 | | | | 22.00 | |

| Lead | | | US$/lb | | | | 0.95 | | | | 0.95 | | | | 0.95 | | | | 0.95 | | | | 0.95 | | | | 0.95 | | | | 0.95 | | | | 0.95 | |

| Zinc | | | US$/lb | | | | 1.18 | | | | 1.16 | | | | 1.15 | | | | 1.15 | | | | 1.15 | | | | 1.15 | | | | 1.15 | | | | 1.15 | |

| Copper | | | US$/lb | | | | 3.95 | | | | 3.76 | | | | 3.78 | | | | 3.65 | | | | 3.60 | | | | 3.60 | | | | 3.60 | | | | 3.60 | |

| MXN | | | per US$ | | | | 21.00 | | | | 21.00 | | | | 21.00 | | | | 21.00 | | | | 21.00 | | | | 21.00 | | | | 21.00 | | | | 21.00 | |

Source: MLN

Table 1.8 shows the LOM and annual projected payable metals and average payability for each metal.

Table 1.8 LOM Payable Metals

| Metal | | | Unit | | | Year 1 | | | Year 2 | | | Year 3 | | | Year 4 | | | Year 5 | | | Year 6 | | | Year 7 | | | Year 8 | | | LOM Total | |

| Ag | | | koz | | | | 893 | | | | 1,018 | | | | 1,202 | | | | 1,242 | | | | 1,253 | | | | 1,062 | | | | 1,656 | | | | 777 | | | | 9,101 | |

| Pb | | | klb | | | | 1,920 | | | | 2,201 | | | | 5,747 | | | | 6,347 | | | | 9,220 | | | | 3,624 | | | | 8,334 | | | | 3,569 | | | | 40,960 | |

| Zn | | | klb | | | | 16,099 | | | | 18,164 | | | | 22,834 | | | | 21,009 | | | | 20,106 | | | | 20,424 | | | | 16,584 | | | | 6,680 | | | | 141,900 | |

| Cu | | | klb | | | | 5,075 | | | | 5,866 | | | | 3,675 | | | | 3,603 | | | | 3,629 | | | | 4,568 | | | | 3,555 | | | | 1,653 | | | | 31,623 | |

Source: MLN

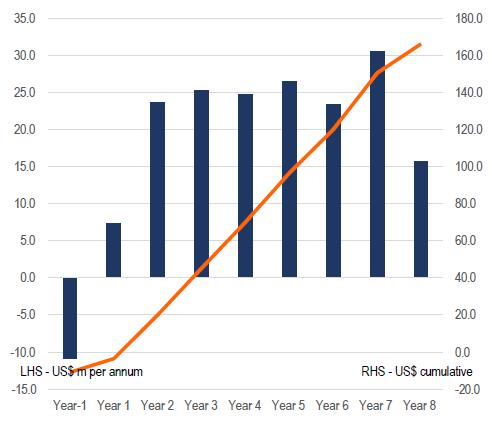

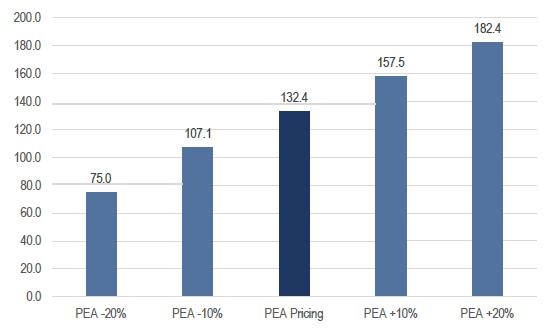

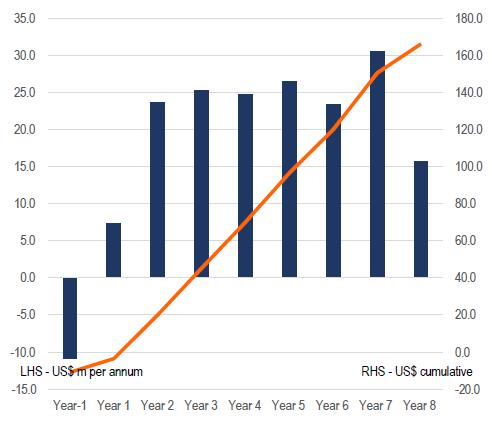

The project has an after-tax Net Present Value based on a 5% discount rate of US$132.4 m, based on the commodity price and FX assumptions detailed in Table 1.6 and Table 23.2. The figure below shows the annual projected cash flows for the project.

Figure 1.8 Annual and Cumulative After-Tax Cash Flow (US$ m)

Source: MLN

The following table summarizes the results of the financial analysis for the La Negra restart.

Table 1.9 Project Results Summary

| | | Unit | | Value | |

| AISC | | US$/oz Ageq | | | 12.95 | |

| LOM NSR | | US$ m | | | 449.2 | |

| LOM Operating Costs | | US$ m | | | 185.1 | |

| LOM Capital | | US$ m | | | 68.1 | |

| Pre-tax Cash Flow | | US$ m | | | 202.3 | |

| After-tax Cash Flow | | US$ m | | | 166.2 | |

| Pre-tax NPV (5%) | | US$ m | | | 160.5 | |

| After-tax NPV (5%) | | US$ m | | | 132.4 | |

Source: MLN

The following table shows the NPV for the project at several discount rates.

Table 1.10 Project NPV Discount Rate Sensitivity

| Discount Rate (%) | | Pre-tax NPV US$ m | | After-tax NPV US$ m | |

| 0.0 | | 202.3 | | | 166.2 | |

| 2.5 | | 179.8 | | | 148.0 | |

| 5.0 | | 160.5 | | | 132.4 | |

| 7.5 | | 143.9 | | | 119.0 | |

| 10.0 | | 129.5 | | | 107.3 | |

| 12.5 | | 117.1 | | | 97.1 | |

| 15.0 | | 106.2 | | | 88.2 | |

Source: MLN

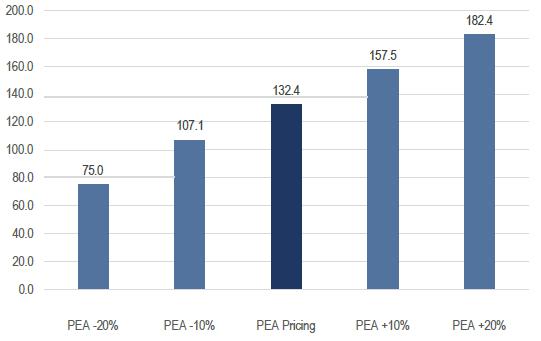

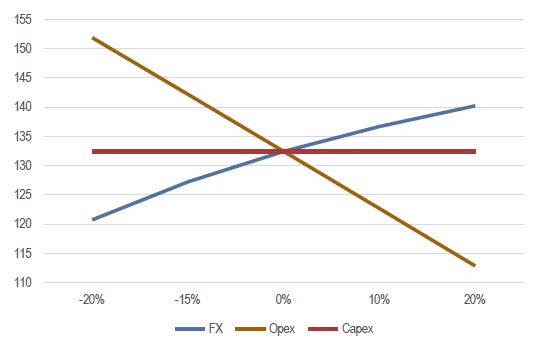

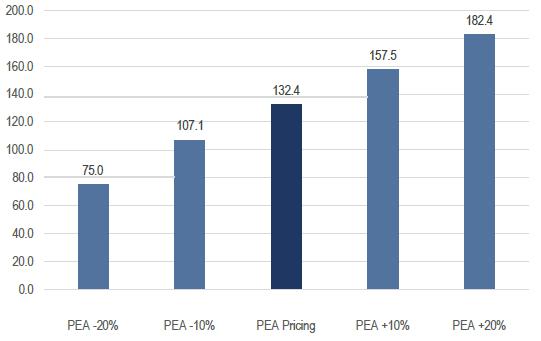

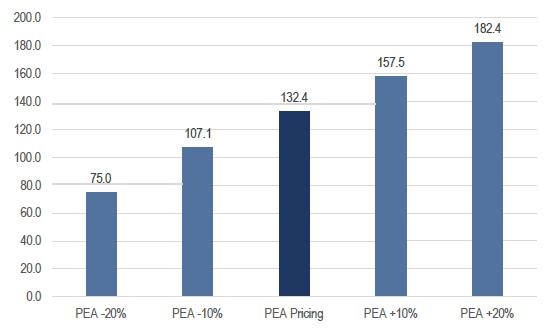

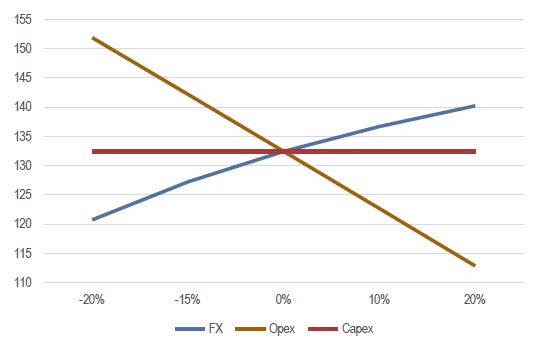

Figure 1.9 shows the project’s sensitivity to metal prices, with prices of -20%, -10%, +10%, and +20% relative to the base case commodity price estimates used in this report. Figure 1.10 shows the distribution of revenue by payable metal.

Figure 1.9 La Negra NPV (US$ m) Metals Price Sensitivity

Source: MLN

Figure 1.10 NSR Distribution by Metal

Source: MLN

The La Negra site team, supported by the consultants listed in this report, have prepared a project restart execution plan, as shown in Figure 26.1.

| 1.17 | Conclusions and Recommendations |

The Preliminary Economic Assessment summarized in this technical report contains adequate detail and information to support the positive economic outcome and recommended restart of La Negra, particularly as this is a brownfields site with existing infrastructure, equipment, development, operating permits, and labor force. Standard industry practices, equipment and design methods were used.

The project contains sufficient resources to be mined by underground methods and recovered by differential flotation.

Based on the results of this study, both economic and technical, and considering that La Negra is a brownfields site, further advancement of La Negra is warranted.

In common with virtually all other mining projects, La Negra faces many risks that could affect the economic viability of the project. External risks are more difficult to predict and potentially impossible to control, such as political risks (including changes in regulations, legislation, ownership rules, and taxes), commodity prices, input prices (particularly reagents and energy), and exchange rates. Maintaining strong relationships with all stakeholders is critical to the success of the project, but these risks are reasonably predictable, and manageable, and form part of the company’s Stakeholder Engagement and Environmental Management Plans.

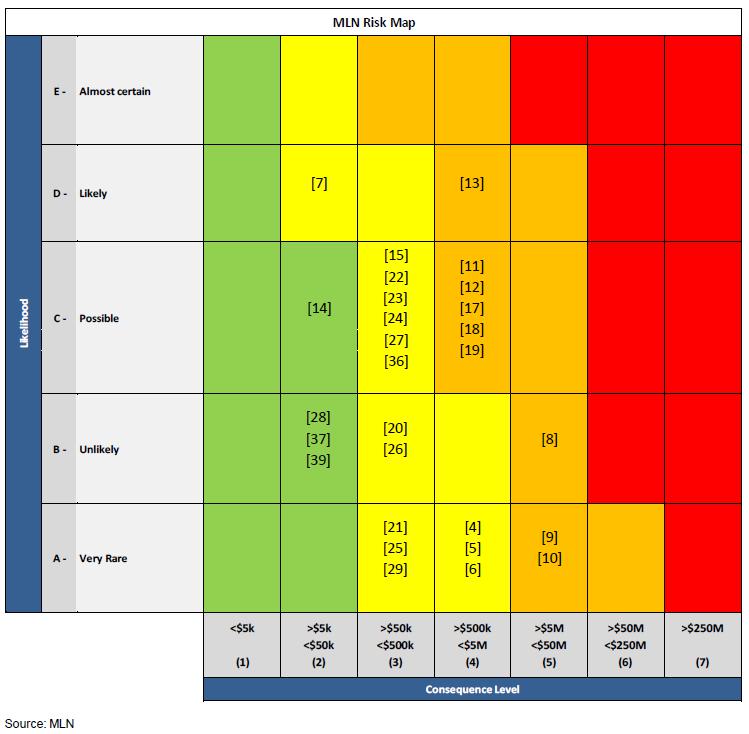

The most significant potential risks include operating and capital cost escalation (including those caused by schedule delays), permitting and environmental compliance, ability to raise finance, commodity prices and exchange rates.

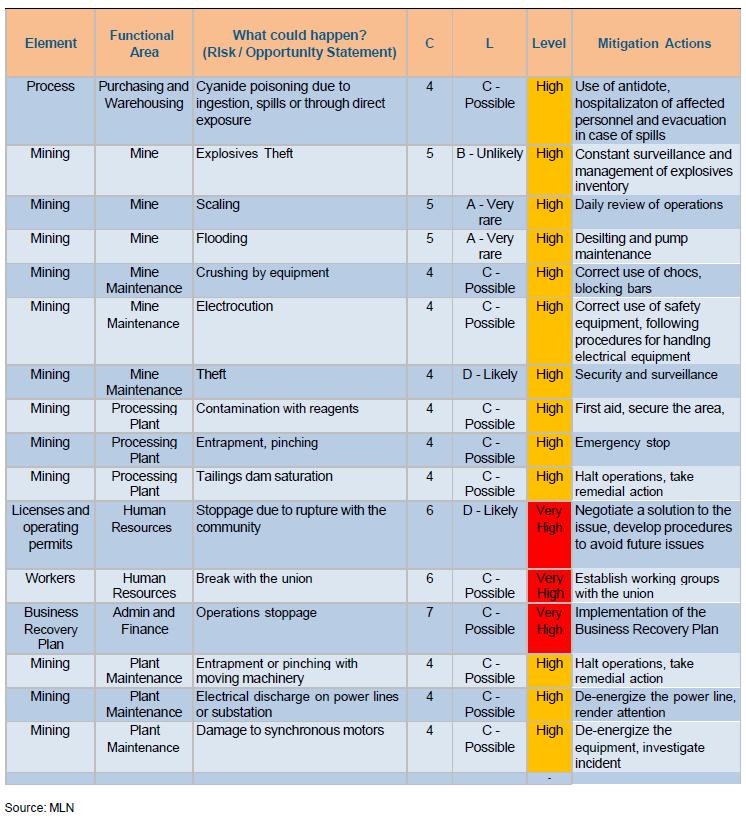

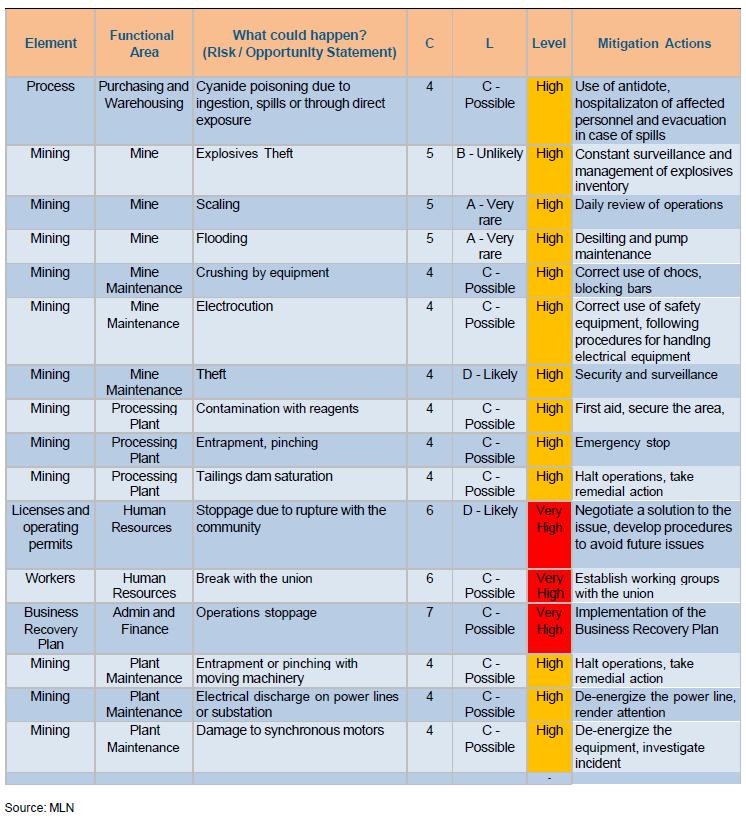

Figure 27.2 identifies the most significant risks associated with the project restart plan and ongoing operating activities. This table also details the measures implemented to avoid, minimize, mitigate and/or offset these risks.

| 1.17.2 | Project Opportunities |

Section 27.2 outlines the various opportunities that will be considered to improve the economics, timing, and operational performance of the mine. The most significant opportunity is to extend the life-of-mine beyond that outlined in this report. In addition, the mine plan presented in this report recovers only a portion of the resource due to the need to leave sufficient rib and sill pillars. The introduction of paste backfill later in the mine life could result in the recovery of a greater percentage of the overall resource, even after the operating and capital costs of paste backfill are incorporated.

Table of Contents

| 1 | Executive Summary | 1 |

| | 1.1 | Introduction | 1 |

| | 1.2 | Property Description and Ownership | 2 |

| | 1.3 | History | 6 |

| | 1.4 | Geology and Mineralization | 6 |

| | 1.5 | Exploration and Data Management | 6 |

| | 1.6 | Metallurgical Testing and Mineral Processing | 7 |

| | 1.7 | Mineral Resource Estimate | 7 |

| | 1.8 | Mineral Reserve Estimate | 9 |

| | 1.9 | Mining | 9 |

| | | 1.9.1 | Geotechnical Considerations | 10 |

| | | 1.9.2 | Mine Design and Mining Methods | 11 |

| | | 1.9.3 | Production Plan | 12 |

| | | 1.9.4 | Equipment | 13 |

| | 1.10 | Recovery Methods | 13 |

| | 1.11 | Infrastructure | 15 |

| | 1.12 | Environment and Social Impact | 15 |

| | 1.13 | Capital Cost Estimate | 18 |

| | 1.14 | Operating Cost Estimate | 19 |

| | 1.15 | Economic Analysis | 21 |

| | 1.16 | Project Execution | 23 |

| | 1.17 | Conclusions and Recommendations | 24 |

| | | 1.17.1 | Project Risks | 24 |

| | | 1.17.2 | Project Opportunities | 24 |

| | |

| 2 | Introduction | 25 |

| | 2.1 | Terms of Reference and Purpose | 25 |

| | 2.2 | Section Contributors | 25 |

| | | 2.2.1 | Additional Contributors | 25 |

| | 2.3 | Site Visits | 26 |

| | 2.4 | Units, Currency and Rounding | 26 |

| | 2.5 | Coordinate System and Elevation | 26 |

| | 2.6 | Sources of Information | 26 |

| | |

| 3 | Reliance on Other Experts | 27 |

| | 3.1 | Ownership | 27 |

| | 3.2 | Environmental and Permitting | 27 |

| | 3.3 | Taxes and Royalties | 27 |

| | |

| 4 | Property Description and Location | 28 |

| | 4.1 | Location | 28 |

| | 4.2 | Property Description and Concessions | 28 |

| | 4.3 | Ownership | 31 |

| | 4.4 | Land Use Agreement | 31 |

| | 4.5 | Royalties and Taxes | 31 |

| | | 4.5.1 | Statutory Royalty | 32 |

| | | 4.5.2 | Peñoles Royalty | 32 |

| | 4.6 | Permitting | 32 |

| | | 4.6.1 | Mining Rights | 32 |

| | | 4.6.2 | Additional Permits | 33 |

| | 4.7 | Property Risks | 34 |

| 5 | Accessibility, Climate, Local Resources, Infrastructure and Physiography | 35 |

| | 5.1 | Accessibility | 35 |

| | | 5.1.1 | Airport | 36 |

| | | 5.1.2 | Port | 36 |

| | 5.2 | Physiography | 36 |

| | 5.3 | Climate | 38 |

| | 5.4 | Local Resources and Infrastructure | 38 |

| | | 5.4.1 | Power | 38 |

| | | 5.4.2 | Human Resources | 38 |

| | |

| 6 | History | 39 |

| | 6.1 | Historical Study and Evaluation Work | 40 |

| | 6.2 | Historical Mineral Resource and Reserve Estimates | 40 |

| | 6.3 | Historical Operating Costs | 45 |

| | |

| 7 | Geological Setting and Mineralization | 46 |

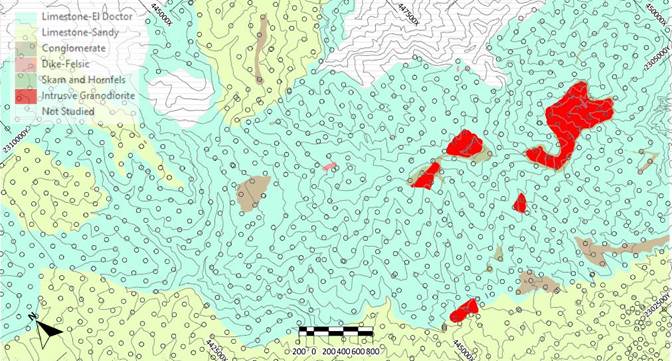

| | 7.1 | Regional Geology | 46 |

| | 7.2 | Property Geology | 49 |

| | | 7.2.1 | Stratigraphy | 49 |

| | | | 7.2.1.1 | Las Trancas Formation | 49 |

| | | | 7.2.1.2 | El Doctor Formation | 49 |

| | | | 7.2.1.3 | El Soyatal and Mezcala Formations | 49 |

| | | | 7.2.1.4 | El Morro Conglomerate | 50 |

| | | 7.2.2 | Intrusives | 50 |

| | 7.3 | Local Geology | 51 |

| | | 7.3.1 | Structure | 52 |

| | 7.4 | Alteration and Mineralization | 52 |

| | | 7.4.1 | Paragenesis | 53 |

| | | 7.4.2 | Geochemistry | 56 |

| | | 7.4.3 Mineralized Trends | 56 |

| | 7.5 | Mineralized Zones | 61 |

| | |

| 8 | Deposit Types | 65 |

| | |

| 9 | | Exploration | 67 |

| | 9.1 | Introduction | 67 |

| | 9.2 | Peñoles | 67 |

| | 9.3 | Minera La Negra | 67 |

| | | 9.3.1 | 2021 Mapping | 67 |

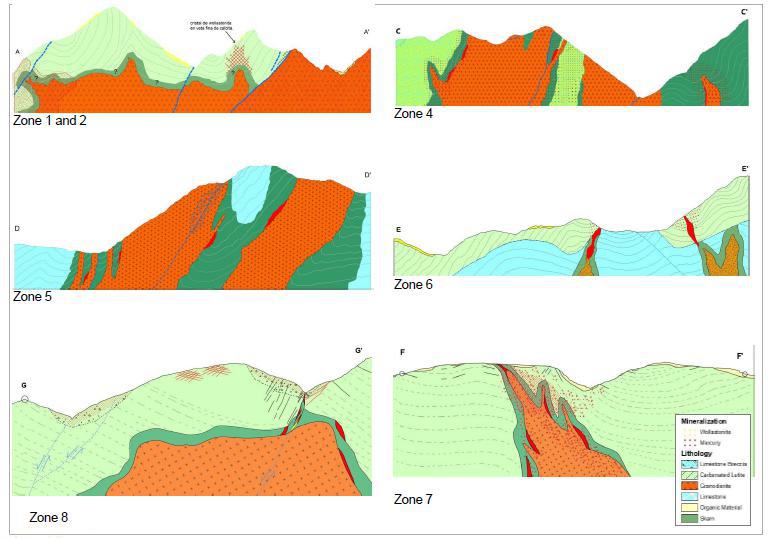

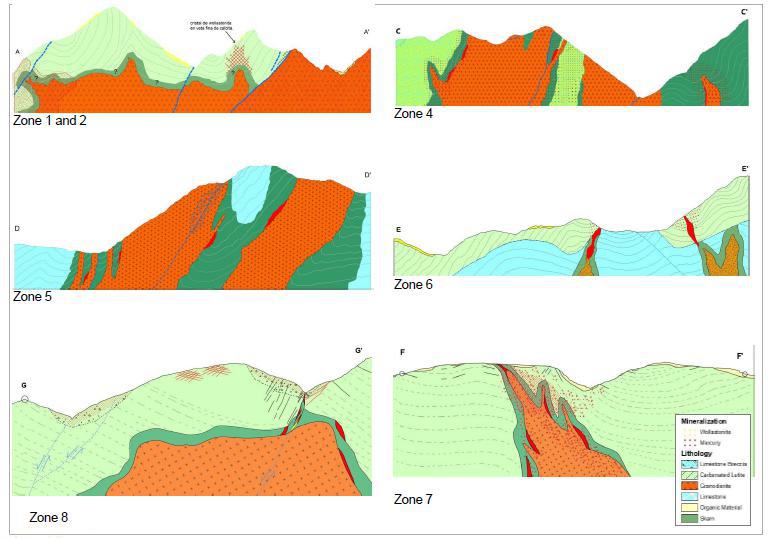

| | | | 9.3.1.1 | Zones 1 and 2 | 68 |

| | | | 9.3.1.2 | Zone 3 | 68 |

| | | | 9.3.1.3 | Zone 4 | 69 |

| | | | 9.3.1.4 | Zone 5 | 69 |

| | | | 9.3.1.5 | Zone 6 | 69 |

| | | | 9.3.1.6 | Zone 7 | 69 |

| | | | 9.3.1.7 | Zone 8 | 69 |

| | | | 9.3.1.8 | Zone 9 | 70 |

| | | | 9.3.1.9 | Zone 10 | 70 |

| | | | 9.3.1.10 | Zone 11 | 70 |

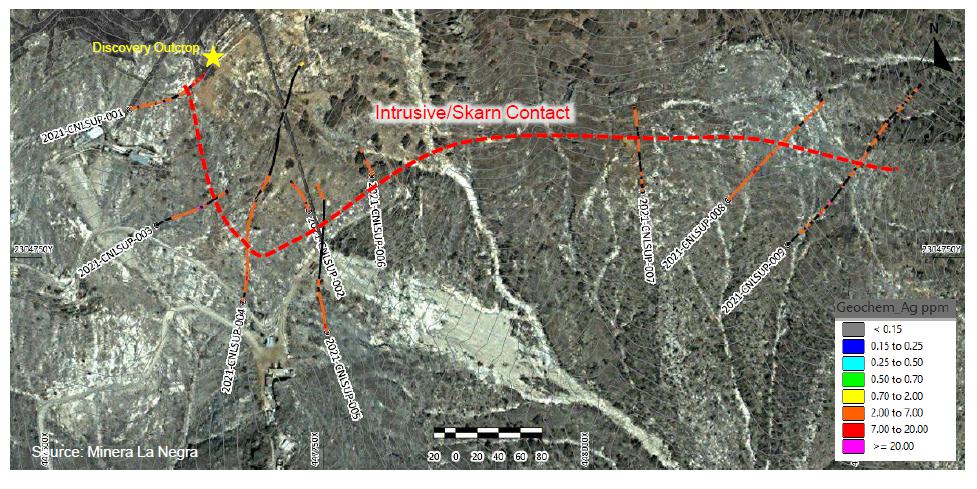

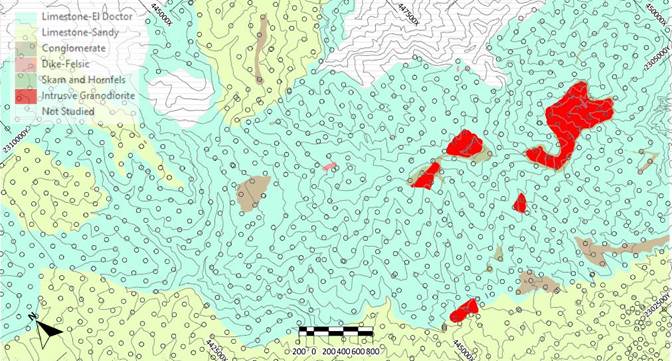

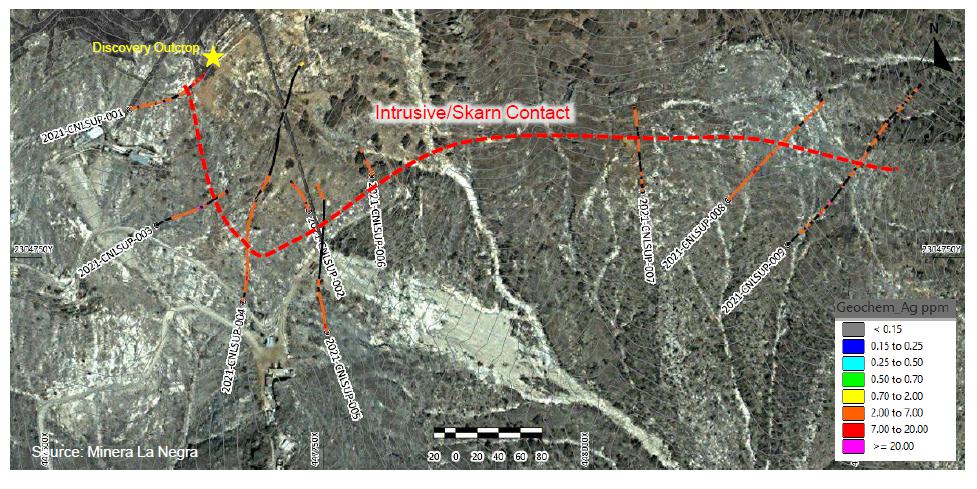

| | | 9.3.2 | 2021 Soil Sampling | 72 |

| | | 9.3.3 | 2021 Channel Sampling Program | 74 |

| | | 9.3.4 | Data Recovery | 75 |

| | | 9.3.5 | 2021 Drill Program | 75 |

| 10 | Drilling | 76 |

| | |

| 11 | Sample Preparation, Analyses and Security | 81 |

| | 11.1 | Peñoles and Previous Explores | 81 |

| | 11.2 | Aurcana | 81 |

| | 11.3 | Sample Preparation | 82 |

| | | 11.3.1 | Surface Sampling | 82 |

| | | 11.3.2 | Mine Sampling | 82 |

| | | 11.3.3 | Drill Core Sampling | 82 |

| | 11.4 | Sample Security | 83 |

| | 11.5 | Sample Analysis | 83 |

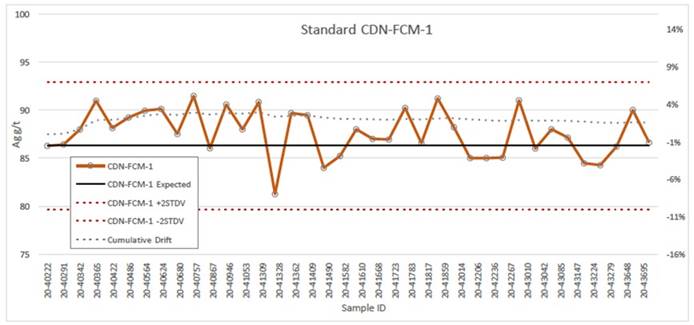

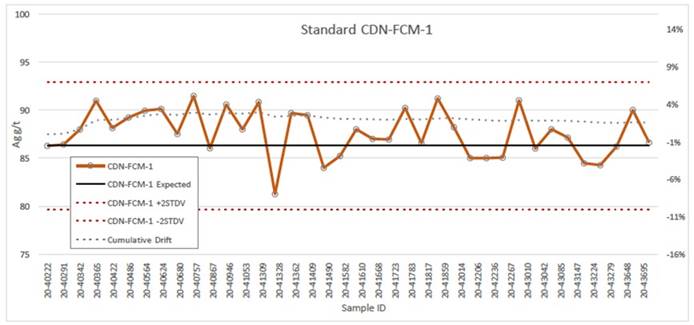

| | 11.6 | QA/QC-2021 Drill Hole Program | 83 |

| | 11.7 | Opinion of Qualified Person | 86 |

| | |

| 12 | Data Verification | 87 |

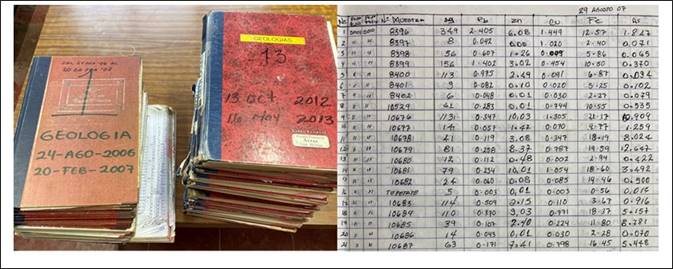

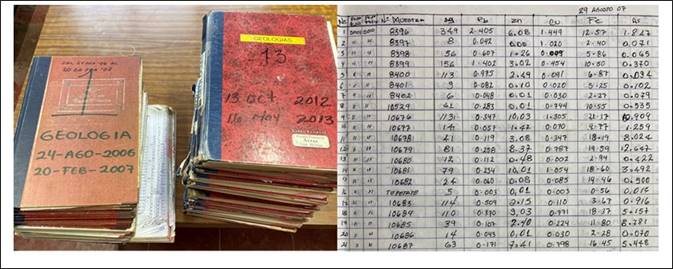

| | 12.1 | Data Sources and Records Maintenance | 87 |

| | 12.2 | Verification Completed as Part of the Mineral Resource Process | 89 |

| | 12.3 | Qualified Person’s Opinion of Data Adequacy | 90 |

| | |

| 13 | Mineral Processing and Metallurgical Testing | 91 |

| | 13.1 | Introduction | 91 |

| | 13.2 | NSR – Net Smelter Return | 92 |

| | 13.3 | NSR-Calculation | 92 |

| | 13.4 | Tonnage | 93 |

| | 13.5 | Head Grade (Grade) | 93 |

| | 13.6 | Recovery | 94 |

| | 13.7 | Concentration Ratio (Mass Pull) | 97 |

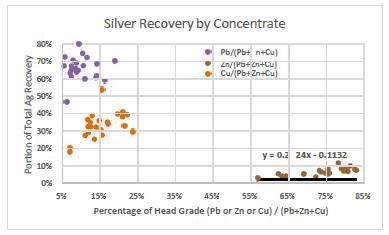

| | 13.8 | Silver Recovery Total and by Concentration | 97 |

| | 13.9 | Arsenic Recovery to Copper and Lead Concentrates | 98 |

| | 13.10 | Other Deleterious Elements | 99 |

| | 13.11 | Trucking | 99 |

| | 13.12 | Model Results and Conclusions | 99 |

| | |

| 14 | Mineral Resource Estimates | 102 |

| | 14.1 | Summary | 102 |

| | 14.2 | Supporting Data Quality | 104 |

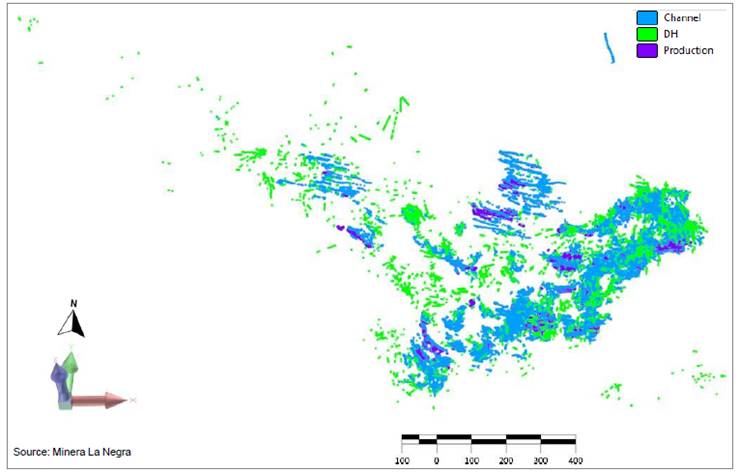

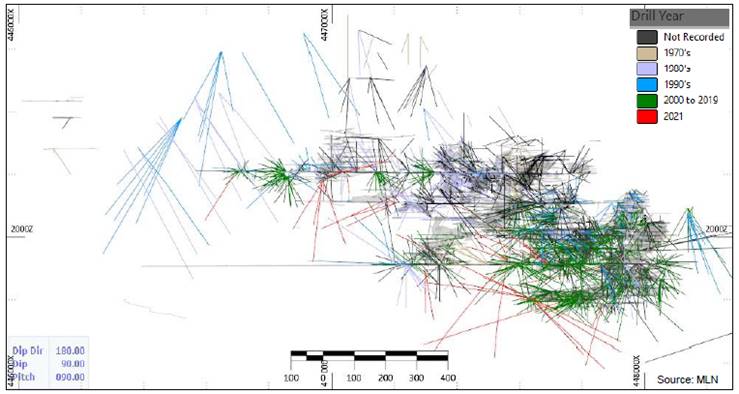

| | | 14.2.1 | Data Types | 104 |

| | | 14.2.2 | Drilling by Era | 106 |

| | | 14.2.3 | Deleterious Element Coverage | 106 |

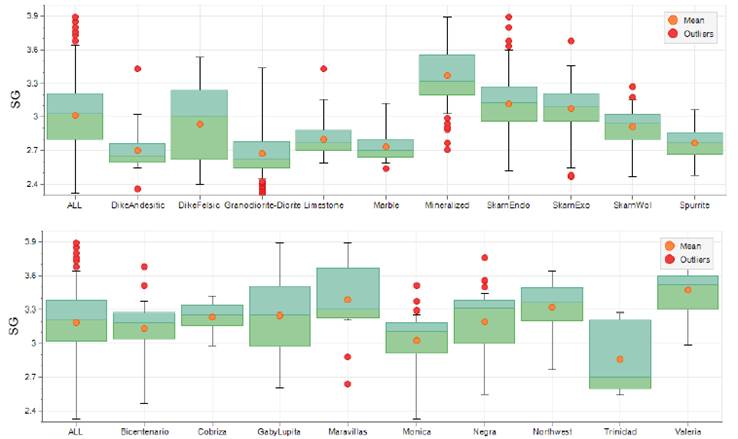

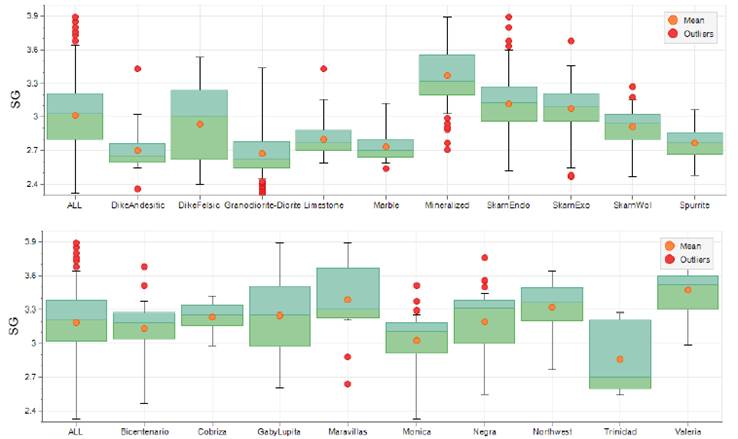

| | | 14.2.4 | Density | 107 |

| | 14.3 | Modeling of Mineral Bodies | 108 |

| | 14.4 | Domaining and Data Grouping | 111 |

| | | 14.4.1 | Estimation Groups | 112 |

| | | | 14.4.1.1 | Negra Upper | 112 |

| | | | 14.4.1.2 | Negra | 112 |

| | | | 14.4.1.3 | Cobriza | 112 |

| | | | 14.4.1.4 | Bicentenario | 113 |

| | | | 14.4.1.5 | Trinidad | 113 |

| | | | 14.4.1.6 | Brecha | 113 |

| | | | 14.4.1.7 | Maravillas | 113 |

| | | | 14.4.1.8 | Northwest | 113 |

| | 14.5 | Capping and Compositing | 116 |

| | 14.6 | Variogram Modelling and Search Orientation | 117 |

| | | 14.6.1 | Search Ellipse Orientation | 117 |

| | | 14.6.2 | Experimental Variography | 119 |

| | 14.7 | Search Parameters | 121 |

| | 14.8 | Block Model Structure | 122 |

| | 14.9 | Resource Classification | 122 |

| | 14.10 | Depletion of Historic Mining | 125 |

| | 14.11 | Cut-off Grade and Reasonable Prospects for Eventual Economic Extraction | 127 |

| | | 14.11.1 | Commodity Pricing | 128 |

| | | 14.11.2 | Metallurgical Flotation Recovery and Deportment to Concentrate | 128 |

| | | 14.11.3 | Smelter Terms | 128 |

| | 14.12 | Resource Statement | 129 |

| | 14.13 | Validation | 132 |

| | 14.14 | Item 14(d) Form NI 43-101 and Estimation Risks | 134 |

| | 14.15 | Reasonable Prospects for Eventual Economic Extraction | 134 |

| | |

| 15 | Mineral Reserve Estimates | 136 |

| | |

| 16 | Mining Methods | 136 |

| | 16.1 | Introduction | 136 |

| | | 16.1.1 | Basis of Estimate | 136 |

| | | 16.1.2 | Mining Method and Mining Costs | 137 |

| | | 16.1.3 | Dilution | 137 |

| | | 16.1.4 | Cutoff grade | 137 |

| | 16.2 | Geotechnical Considerations | 137 |

| | | 16.2.1 | Stability Assessments | 137 |

| | | 16.2.2 | Backfill | 141 |

| | 16.3 | Hydrogeological Considerations | 141 |

| | | 16.3.1 | Groundwater Conditions | 141 |

| | | 16.3.2 | Dewatering and Mine Drainage | 141 |

| | | | 16.3.2.1 | Pumps | 141 |

| | | | 16.3.2.2 | Pumping Rates and Projections | 143 |

| | | | 16.3.2.3 | Water Treatment and Usage | 143 |

| | | | 16.3.2.4 | Potable Water | 143 |

| | 16.4 | Mine Safety | 143 |

| | | 16.4.1 | Mine Rescue Equipment | 143 |

| | | 16.4.2 | Refuge Chambers | 143 |

| | | 16.4.3 | Mine Ambulance | 143 |

| | | 16.4.4 | Fire Protection Systems | 143 |

| | 16.5 | Underground Mine Design | 144 |

| | | 16.5.1 | Stope Design Criteria | 144 |

| | | 16.5.2 | Mining Methods | 145 |

| | | | 16.5.2.1 | Historical Mining Methods | 145 |

| | | | 16.5.2.2 | Proposed Mining Methods | 146 |

| | | 16.5.3 | Resource Extraction | 148 |

| | | 16.5.4 | Mine Workings | 148 |

| | | 16.5.5 | Pillars | 148 |

| | 16.6 | Mine Production Schedule | 148 |

| | | 16.6.1 | Production Schedule Criteria | 148 |

| | | 16.6.2 | Production Schedule | 148 |

| | | 16.6.3 | Production Plan | 148 |

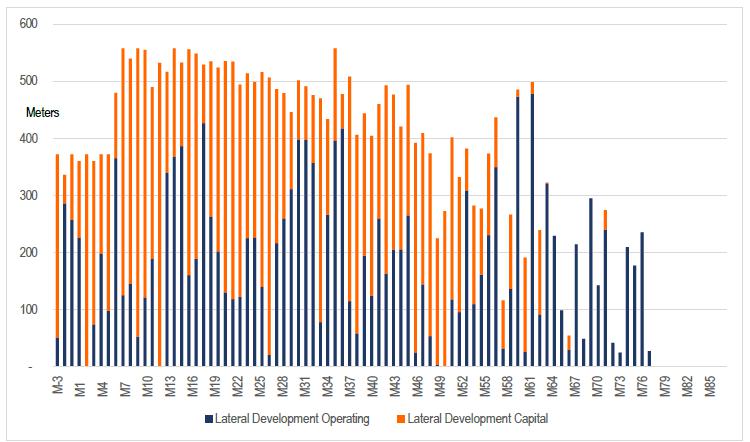

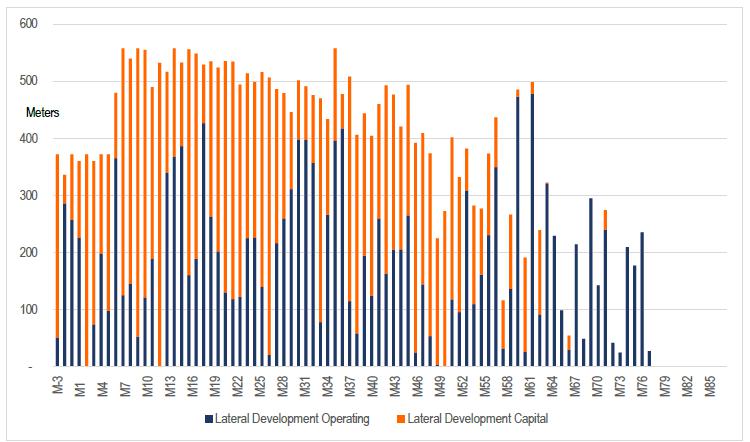

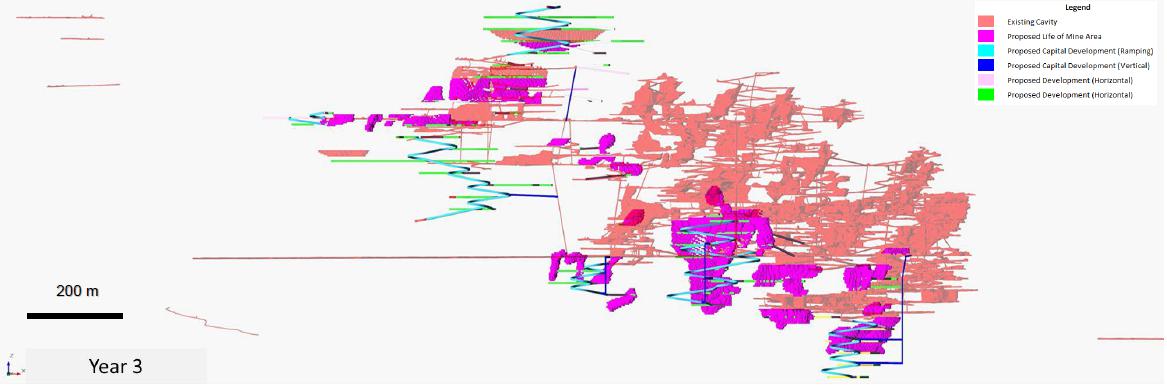

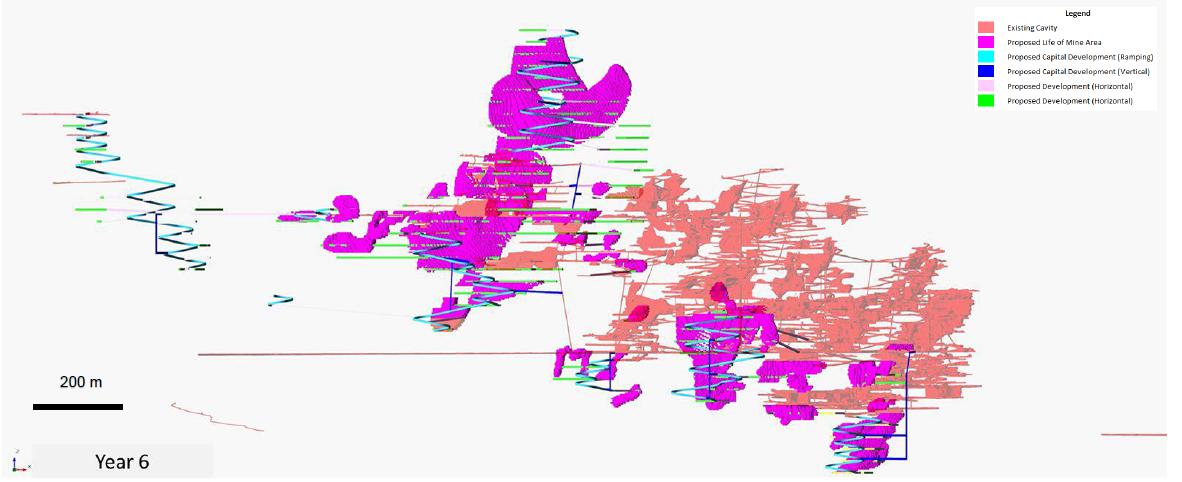

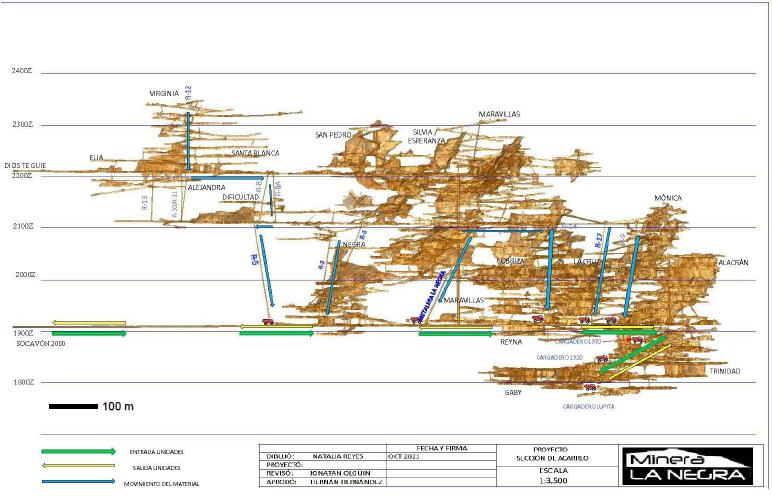

| | | 16.6.4 | Underground Development | 150 |

| | 16.7 | Mine Equipment | 160 |

| | | 16.7.1 | Introduction | 160 |

| | | 16.7.2 | Time Definitions and Work Schedules | 160 |

| | | 16.7.3 | Ground Support | 160 |

| | | 16.7.4 | Drilling and Blasting | 160 |

| | | | 16.7.4.1 | Drilling | 160 |

| | | | 16.7.4.2 | Explosives | 161 |

| | | 16.7.5 | Mucking | 161 |

| | | 16.7.6 | Haulage | 161 |

| | | 16.7.7 | Support and Auxiliary Equipment | 161 |

| | | 16.7.8 | Equipment Summary | 161 |

| | 16.8 | Power and Ventilation | 163 |

| | | 16.8.1 | Cabling | 163 |

| | | 16.8.2 | Substations and Transformers | 163 |

| | | 16.8.3 | Ventilation | 165 |

| | | 16.8.4 | Compressors | 167 |

| | 16.9 | Underground Mine Infrastructure | 167 |

| | | 16.9.1 | Underground Infrastructure | 167 |

| | | | 16.9.1.1 | Access, Egress and Evacuation Routes | 167 |

| | | | 16.9.1.2 | Ore Passes | 168 |

| | | | 16.9.1.3 | Magazines and Warehouses | 170 |

| | | | 16.9.1.4 | Workshops | 170 |

| | | | 16.9.1.5 | Fuel Supply and Storage | 170 |

| | | | 16.9.1.6 | Compressed Air | 170 |

| | | | 16.9.1.7 | Active Workings/Pathways | 170 |

| | | | 16.9.1.8 | Closed Workings/Pathways | 170 |

| | | 16.9.2 | Surface Infrastructure | 170 |