- MOS Dashboard

- Financials

- Filings

-

Holdings

- Transcripts

- ETFs

- Insider

- Institutional

- Shorts

-

8-K Filing

The Mosaic Company (MOS) 8-KImpacts of the Global

Filed: 23 Feb 09, 12:00am

Exhibit 99.1

Impacts of the Global

Economic Crisis on Crop Nutrient Markets

Market Mosaic is a quarterly newsletter published for our customers, suppliers and stakeholders by the Market Analysis group of The Mosaic Company. The Spring and Fall issues recap our assessment of the near term outlook for agricultural and crop nutrient markets. The Summer and Winter issues provide an in-depth look at topics of special interest to our readers.

Michael R. Rahm

Vice President

mike.rahm@mosaicco.com

Joseph Fung

Market Analyst

joseph.fung@mosaicco.com

Mathew Philippi

Market Analysis Assistant

matt.philippi@mosaicco.com

Recent forecasts released by the International Monetary Fund (IMF) and private forecasting firms paint a bleak picture of the world economy in 2009. IMF forecasts released at the end of January indicate that global economic growth will slow from the brisk pace of 5.2% in 2007 and from 3.4% in 2008 to just 0.5% in 2009. Advanced economies are projected to contract 2.0% while emerging and developing economies are expected to expand 3.3% in 2009.

IHS Global Insight in January projected that the world economy would contract 0.5% in 2009. If this forecast is on target, the world economy will register its weakest performance since 1982 when global output expanded just 0.1%.

Some analysts have suggested that the current crisis afflicting global financial markets and the banking industry rivals conditions during the Great Depression. That may be true for this sector, but the most recent macroeconomic forecasts clearly are not nearly as bad as conditions during the Great Depression. For example, U.S. unemployment reached 25% during the Great Depression and another 25% of the work-force was grossly under-employed by most estimates. At this point, the current economic downturn looks more like the serious 1981-82 global recession than the Great Depression.

Nearly all central banks and governments have implemented aggressive expansionary monetary and fiscal policies in response to the economic crisis ignited by the implosion of the U.S. sub-prime mortgage market. Despite criticism that some of the fiscal stimulus packages are developing into grab bags for special interests, these policies will take hold later this year and could revive economies more quickly than expected and even fuel inflation down the road. The IMF and IHS Global Insight project that the global economy will grow 3.0% and 2.6%, respectively, in 2010.

In the meantime, key sectors such as housing, finance, auto and retail will operate in a brutal market environment. The paralysis of credit markets coupled with massive wealth destruction and record low consumer confidence creates the most pessimistic outlook for the world economy in more than 25 years.

A key question is how will the global economic crisis impact crop nutrient markets? This issue of Market Mosaic attempts to answer that question by first identifying the transmission mechanisms by which macroeconomic developments impact crop nutrient markets and then by assessing the likely impacts of expected changes on these markets.

— continued inside

The Transmission Mechanisms and Our Take-Aways

We identify and discuss five transmission mechanisms in this analysis. The first and most immediate is reduced credit availability. Credit constrained demand during the last half of 2008 in some regions such as Latin America and illiquid credit markets are expected to continue to hamstring business in this region and possibly others in 2009.

The second and most controversial mechanism is the exodus of investment funds from agricultural commodity markets due to a crisis-induced need for liquidity. This impact played out during the last half of 2008, but the jury is still out and has not rendered its verdict on how much of the decline in crop prices was due to weaker fundamentals versus a rush to liquidity. Our assessment is that the rush to liquidity may have exacerbated the decline, but it was not a root cause and likely had a minor impact on prices. A more compelling reason was that it stopped raining in Iowa last spring.

The third and most obvious transmission mechanism is the impact of slower economic growth on food demand and more pointedly on grain demand and crop nutrient use. It will take more time to get an accurate read of the impact of the current economic downturn, but history demonstrates that recessions have had only limited effects on global grain and oilseed use. We fully expect that the current downturn will produce no different result.

The fourth and one of the most powerful mechanisms is the impact of slower economic growth on energy demand, energy prices and biofuels economics. This mechanism is important today because the production and distribution of crop nutrients is energy intensive and because of the rapid development of bio-fuels – especially the exponential growth of corn-based ethanol production in the United States. The current downturn is expected to slow energy demand growth, keep a lid on energy prices for awhile and reduce the rate of growth of grain demand for biofuels production. That said, we do not see governments in energy deficient and grain surplus countries wavering from their commitments to biofuels. Our assessment is that biofuels in general and U.S. corn-based ethanol in particular remain a viable component of a comprehensive long term energy policy.

The fifth and most subtle mechanism is the impact of macroeconomic developments on exchange rates. Our assessment – or SWAG in the case of exchange rate forecasts – is that, despite the recent strength of the dollar, the unprecedented policies implemented to combat the crisis in the United States likely will keep the domestic economy and the dollar weak relative to other major economies and currencies in the long run. If true, that bodes well for commodity prices and the U.S. agricultural sector.

Reduced Credit Availability

Illiquid credit markets have made it difficult if not impossible for many companies to renew lines of credit or refinance debt since last fall. As a result, many were forced to curtail output and lay off workers.

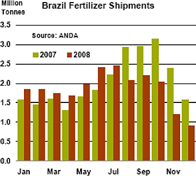

In the case of crop nutrient markets, reduced credit availability impacted key regions such as Brazil but had limited impact in other regions such as North America. The latest statistics from the Brazilian fertilizer association (ANDA) indicate that crop nutrient shipments declined 9% to 22.4 million tonnes in 2008. That still was the fourth highest usage in history, but it was much less than preliminary forecasts of around 26 million tonnes. Several factors such as the large carryover of high-priced inventories, declines in soybean and sugar prices, increases in crop input costs and dry conditions in some parts of the country combined to reduce fertilizer use. Reduced credit availability, however, also played a role. For example, shipments during the first seven months of 2008 were up 20% from a year earlier, but then plunged 35% or 4.5 million tonnes during the last five months of the year. Part of this sharp decline was due to reduced credit availability from both financial institutions as well as agricultural companies that supply roughly one-third of the working capital to Brazilian farmers.

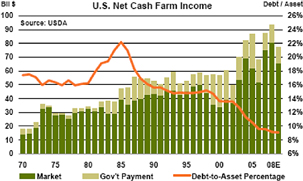

In other regions such as North America, credit had less of an impact than other factors. Shipments into the North American distribution pipeline plunged last fall for several reasons, but reduced credit availability was not a major factor. In the case of the United States, the financial condition of the farm sector remains solid. The latest USDA estimates indicate that U.S. net cash farm income reached a record of more than $93 billion in 2008, topping the high five-year average by 18% or $14 billion and exceeding the ten-year average by 38% or $26 billion. The balance sheet of U.S. agriculture also is the strongest in recent history with farm equity of $2.13 trillion and a debt-to-asset percentage of just 9%. Furthermore, many of the public and private entities specializing in agricultural lending were not large investors in troubled assets. The combination of credit worthy customers and financially strong lenders has minimized the credit issues that are hamstringing other industries.

The Rush to Liquidity

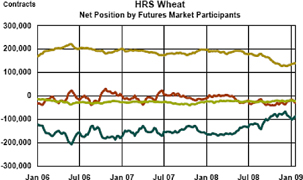

Many investment funds that had built large long positions in agricultural commodities exited these markets during the last half of 2008 for both fundamental reasons as well as the need to raise cash. Statistics published by the Commodity Futures Trading Commission (CFTC) in its weekly Commitments of Traders Supplemental Report were used to calculate the net position of investment funds including both large non-commercial traders and commodity index traders.

In the case of corn, the long position of investment funds peaked at more than 674,000 contracts or almost 3.4 billion bushels on March 4, 2008. Funds reduced their long position 73% to less than 179,000 contracts or about 890 million bushels by November 18, 2008. Large non-commercial traders transitioned from a long position during the first half of the year to a small short position by the end of October.Commodity index traders, who typically hold only long positions, cut their long position nearly in half during the same period. The charts show that investment funds also reduced their long positions in both the soybean and wheat markets.

Our assessment is the decline in crop prices during the last half of 2008 was more the result of weaker fundamentals rather than a rush to liquidity by investment funds. Nevertheless, agricultural interests and politicians have called for greater futures market regulation following Congressional hearings last year about the impact of investment funds on the volatility of commodity prices. Some of the more extreme proposals such as the prohibition of speculative trading would short circuit the key price discovery function performed by futures markets. The charts show a balance of long speculative positions and short commercial hedging positions for the major agricultural commodities during the last three years. Both speculative trading and commercial hedging are required for a viable futures market.

Impact of Lower GDP Growth on Food Demand

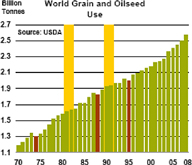

History shows that economic downturns have had limited impacts on global grain and oilseed use and crop nutrient demand. In fact, global grain and oilseed use has declined in only three years since 1970. What is noteworthy is that the decline in each of those years – namely the 1974/75, 1988/89 and the 1995/96 crop years – was largely the result of a poor harvest and an increase in prices needed to allocate short supplies to their highest valued uses.

For example, grain and oilseed use declined almost 44 million tonnes in 1974/75 but the 1974 global harvest was off more than 58 million tonnes from a year earlier. Global use declined 20 million tonnes in 1988/89 and about 15 million tonnes in 1995/96, but the 1988 and 1995 harvests were down 56 million tonnes and 53 million tonnes, respectively, from a year earlier.

More importantly, the charts also show that grain and oilseed use continued to increase during the severe global recession during the early 1980s and the more mild recession in the early 1990s. For example, global GDP per capital increased 0.1% in 1980, decreased 0.7% in 1981 and dropped another 1.4% in 1982, but global grain and oilseed use still registered steady increases of 1.4% in 1980/81, 1.9% in 1981/82 and 1.3% in 1982/83.

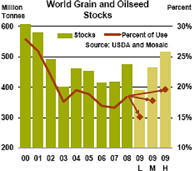

Furthermore, we have maintained that the world still needs to produce another large crop in 2009 in order to prevent global grain and oilseed stocks from falling to unsafe levels. The chart below was first published in the August issue of Market Mosaic and shows projected stocks at the end of the 2009/10 crop year for low, medium and high production and use scenarios.

We have made a few changes to the assumptions from the original analysis as a result of developments during the last several months. In particular, given the slowdown in the global economy, we now assume grain and oilseed demand grows at 0%, 1% and 2%, respectively, in the low, medium and high scenarios. Furthermore, we assume harvested area remains flat at the record levels of last year in all three scenarios. Finally, we assume an average yield equal to the 10-year trend in the medium scenario, a yield equal to trend plus the largest positive deviation from trend in the high scenario and a yield equal to trend minus the largest negative deviation from trend in the low scenario. This analysis indicates that the world requires another near-record harvest to prevent a large drop in global stocks in 2009/10. Needless to say, supply prospects are not off to a stellar start so far due to serious droughts in Argentina, Brazil and China as well as a drop in U.S. winter wheat acreage.

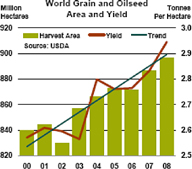

The bumper crops of the last two years are worth highlighting to illustrate the challenges of repeating this performance. Farmers harvested almost 25 million more hectares in 2008 than in 2006. That is slightly more than the area harvested by Canadian farmers last year. Not only did farmers plant more area during the last two years but they also harvested record yields thanks to more intensive input usage and a little help from Mother Nature – especially last year. The average yield in 2008 exceeded the 10-year trend by a wide margin. In fact, if the yield last year would have just equaled trend, global grain and oilseed production would have totaled 77 million tonnes less than what farmers harvested last year and the world would have drawn down stocks by more than 15 million tonnes during the 2008/09 crop year.

Impact of Lower GDP Growth on Energy Demand and Biofuels Production

The downturn in the global economy has curbed the growth of energy demand and pulled down energy prices. That in turn has slowed, or has the potential to slow, the rates of growth of biofuels production, grain demand and nutrient use.

In the case of the U.S. ethanol industry, the pace of growth has slowed moderately. For example, the latest U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) forecasts indicate that U.S. plants will grind 3.6 billion bushels of corn or 30% of the 2008 harvest into ethanol during the 2008/09 crop year. That is off 10% from earlier forecasts of 4.0 billion bushels, but it still is up 20% from 3.0 billion bushels in 2007/08 and it is up more than 70% from 2.1 billion bushels in 2006/07.

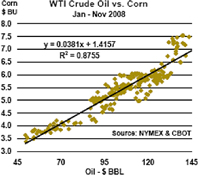

The large increase in the use of corn for ethanol production caused corn prices to trade in lock-step with energy prices and exchange rates for much of last year. The trading logic for this linkage is that higher oil prices – driven by strong global growth and a weak dollar – improve ethanol profitability, boost ethanol output and increase corn demand. This logic obviously applies in reverse – lower oil prices drive lower corn prices. Indeed, the daily closing prices of the nearby contracts for oil and corn tracked closely from January through November last year or during the sharp run-up and decline in these two commodity prices. Based on this relationship, each $10 per barrel increase (decrease) in the price of oil corresponded to a $0.38 per bushel increase (decrease) in the price of corn during this period.

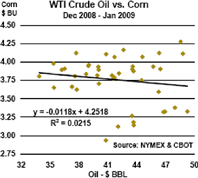

This strong positive correlation caused some analysts and traders to proclaim corn as an energy rather than a food crop and to conclude that traditional fundamental factors such as food demand, crop input costs and weather do not matter very much compared to oil prices and exchange rates. However, other fundamental drivers such as the large increases in crop input costs and a severe drought in Argentina began to influence corn prices beginning in December. The daily closing prices of oil and corn did not correlate during December and January. Other analysts then proclaimed that corn prices finally had decoupled from oil prices.

The key take-aways here are that all fundamental drivers will matter at some point, that global growth rates influence crop nutrient markets through their impact on energy prices and biofuels production, and that other fundamental drivers are showing positive signs.

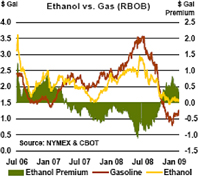

The combination of lower ethanol prices and relatively high corn costs has squeezed U.S. ethanol producers. However, ethanol prices have not declined as much as wholesale gasoline prices during the last several months. Ethanol traded at a steep discount to gasoline during the period of peak energy prices earlier last year. This resulted in lucrative blending margins for gasoline distributors even before the 51 cent per gallon tax credit that blenders received in 2008. Ethanol is trading at a premium to gasoline today and this premium has exceeded the 45 cent blending credit in effect for 2009 during several periods this year.

The profitability of ethanol production will vary over time just like the production economics of other commodities. However, our assessment remains that biofuels in general and U.S. ethanol in particular are viable components of comprehensive energy policy due to the long term outlook for energy and agricultural commodities. In particular, the outlook for energy prices remains positive despite the current economic downturn as a result of strong long term demand prospects in the developing world as well as the higher costs of finding and developing new petroleum supplies. In addition, leading seed companies indicate that new varieties in the R&D pipeline will increase yields significantly during the next several decades. Productivity growth likely will keep grain prices at moderate levels in the long term.

Exchange Rates

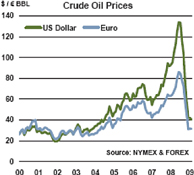

Because much of the world’s international trade is transacted in U.S. dollars, the impact of macroeconomic developments on exchange rates is a potent but often less understood transmission mechanism. The U.S. dollar has declined significantly during this decade. For example, a trade-weighted dollar index peaked at 119 in February 2002 and then declined steadily until hitting bottom at 72 in April 2008 – almost 40% less than its peak six years earlier. The dollar has appreciated almost 20% against most major currencies during the current financial crisis and most analysts only can offer the “other-nations-are-even-worse-off-than-the-United-States” explanation for this move.

A decline of the greenback benefits U.S. exporters and foreign importers but hurts U.S. importers and foreign exporters – at least in the short run. For example, assuming no change in the dollar price of a product, U.S. exporters and foreign importers benefit because a weak dollar reduces the local currency price of the imported product. Conversely, a decline in the dollar hurts U.S. importers and foreign exporters because a weaker dollar reduces the local currency price received by the foreign exporter, again assuming no change in the dollar price of a product.

In both cases, supply and demand are expected to pressure market prices higher as foreign importers bid up the price of the now less expensive product or foreign exporters push to increase the dollar price of the product in order to maintain local currency revenue. For example, the dollar price of oil increased sharply during the first half of last year due to fundamental factors as well as the weak dollar. The price of oil in Euros per barrel increased much less than the dollar price and better reflects the fundamental forces at play in the global oil market.

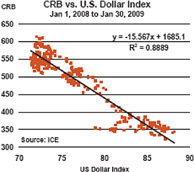

There is a strong inverse relationship between the value of the dollar and commodity prices. The chart plots the daily trade-weighted index of the dollar against the daily Commodity Research Bureau’s (CRB) commodity price index from January 1, 2000 through January 30, 2009. It shows that when the dollar was weak commodity prices were strong and when the dollar was strong commodity prices were weak.

While the recent rebound of the dollar is difficult to explain, it no doubt has put downward pressure on commodity prices including oil and grain values. Forecasting exchange rates is a high-risk endeavor, but given the challenges facing the U.S. economy in the long term, it seems unlikely the dollar will remain strong relative to other major currencies – and that should bode well for commodity prices.