UNITED STATES

SECURITIES AND EXCHANGE COMMISSION

Washington, D.C. 20549

FORM 10-K/A

(Amendment No. 1)

FOR ANNUAL AND TRANSITION REPORTS

PURSUANT TO SECTIONS 13 OR 15(d) OF THE

SECURITIES EXCHANGE ACT OF 1934

(Mark One)

| x | ANNUAL REPORT PURSUANT TO SECTION 13 OR 15(d) OF THE SECURITIES EXCHANGE ACT OF 1934 |

For the Fiscal Year Ended December 31, 2005

or

| ¨ | TRANSITION REPORT PURSUANT TO SECTION 13 OR 15(d) OF THE SECURITIES EXCHANGE ACT OF 1934 |

For the Transition Period From to

Commission File Number 001-32331

Foundation Coal Holdings, Inc.

(Exact Name of Registrant as Specified in Its Charter)

| | |

| Delaware | | 42-1638663 |

(State or Other Jurisdiction of Incorporation or Organization) | | (I.R.S. Employer Identification No.) |

999 Corporate Boulevard, Suite 300 Linthicum Heights, Maryland | | 21090 |

| (Address of Principal Executive Offices) | | (Zip Code) |

Registrant’s telephone number, including area code) (410) 689-7500

Securities registered pursuant to Section 12(b) of the Act:

| | |

Title of Each Class | | Name of Each Exchange on Which Registered |

| Common Stock, $0.01 par value | | New York Stock Exchange |

Securities registered pursuant to Section 12(g) of the Act: None

Indicate by check mark if the registrant is a well-known seasoned issuer, as defined in Rule 405 of the Securities Act. Yes x No ¨

Indicate by check mark if the registrant is not required to file reports pursuant to Section 13 or Section 15(d) of the Act. Yes ¨ No x

Indicate by check mark whether the Registrant (1) has filed all reports required to be filed by Section 13 or 15(d) of the Securities Exchange Act of 1934 during the preceding 12 months (or for such shorter period that the registrant was required to file such reports), and (2) has been subject to such filing requirements for the past 90 days. Yes x No ¨

Indicate by check mark if disclosure of delinquent filers pursuant to Item 405 of Regulation S-K is not contained herein, and will not be contained, to the best of Registrant’s knowledge, in definitive proxy or information statements incorporated by reference in Part III of this Form 10-K or any amendment to this Form 10-K. ¨

Indicate by check mark whether the registrant is large accelerated filer, an accelerated filer, or a non-accelerated filer. See definition of “accelerated filer and large accelerated filer” in Rule 12b-2 of the Exchange Act. (Check one):

Large accelerated filer x Accelerated filer ¨ Non-accelerated filer ¨

Indicate by check mark whether the Registrant is a shell company (as defined in Rule 12b-2 of the Exchange Act). Yes ¨ No x

The aggregate market value of the Registrant’s voting and non-voting common equity held by non-affiliates of the Registrant calculated using the June 30, 2006 closing price on the New York Stock Exchange, was $2,112.1 million. There were 45,735,643 shares of common stock outstanding on July 31, 2006.

DOCUMENTS INCORPORATED BY REFERENCE

Portions of Registrant’s definitive Proxy Statement submitted to the Registrant’s stockholders in connection with our 2006 Annual Stockholders Meeting was held on May 18, 2006, are incorporated by reference into Part III of this report. The definitive proxy statement was filed with the Securities and Exchange Commission within 120 days after the end of the fiscal year to which this report relates.

TABLE OF CONTENTS

| (1) | Not affected by this Amendment No. 1. Refer to the original Form 10-K previously filed on March 16, 2006. |

2

EXPLANATORY NOTE

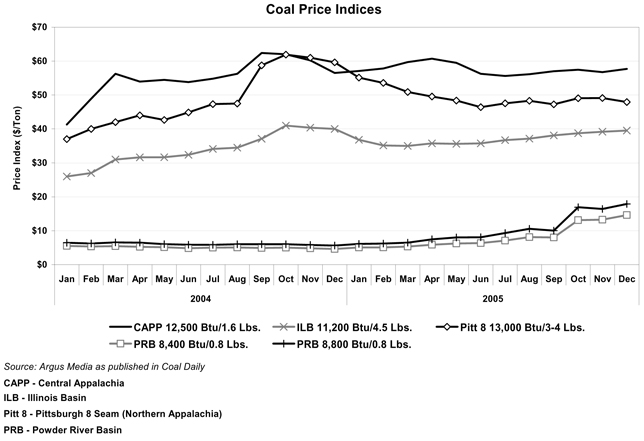

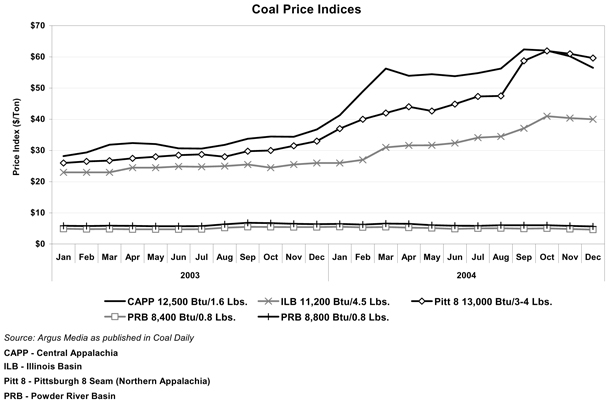

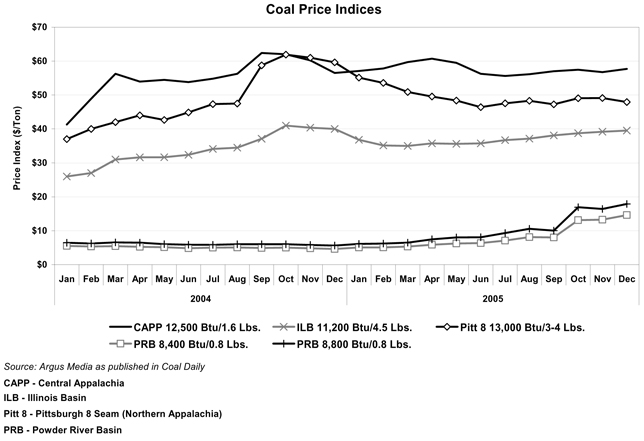

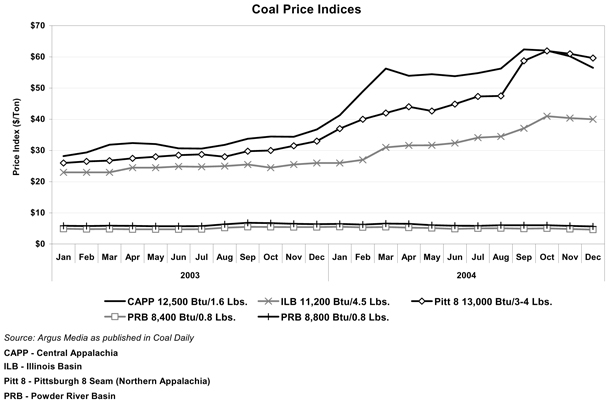

In response to comments raised by the Staff of the Securities and Exchange Commission, this Form 10-K/A (Amendment No. 1) is being filed by Foundation Coal Holdings, Inc. (the “Company”) to (a) revise Items 1, 1A and 2 to change the terminology “reserve base” to “reserves”; (b) revise Item 1 with respect to the description of unleased federal coal that adjoins the Belle Ayr mine; (c) supplement the mine location map in Item 1 to include smaller-scale maps showing the location of and access to each mine; (d) revise Item 7, Management’s Discussion and Analysis of Financial Condition and Results of Operations (MD&A), to eliminate references to “combined pro forma” and “pro forma results” (Non-GAAP combined results of operations for the twelve months ended December 31, 2004 are now compared to the successor results of operations for the year ended December 31, 2005 and to the predecessor results of operations for the year ended December 31, 2003, presented on a historical basis pursuant to the requirements of Item 303(a)(3) of Regulation S-K); and (e) supplement Item 7 by inserting graphs of representative steam coal prices and discussion of the “Other” segment in the segment analysis for the year ended December 31, 2005 compared to the non-GAAP combined twelve months ended December 31, 2004 and in the segment analysis for the non-GAAP combined twelve months ended December 31, 2004 compared to the year ended December 31, 2003.

This amendment modifies Item 7A to correct a typographical error in the third paragraph of the Interest Rate Risk subheading.

As the amendment relates only to Items 1, Business, 1A, Risk Factors, 2, Properties, 7, MD&A and Item 7A, Quantitative and Qualitative Disclosures about Market Risk, the previously issued consolidated financial statements and notes thereto are unchanged. No attempt has been made in this Form 10-K/A to modify or update disclosures in the original report on Form 10-K (“original Form 10-K”) except as required to make the revisions and supplemental disclosures described in the preceding paragraph. This Form 10-K/A does not reflect events occurring after the filing of the original Form 10-K or modify or update any related disclosures. Information not affected by the amendment is unchanged and reflects the disclosure made at the time of the filing of the original Form 10-K with the Securities and Exchange Commission on March 16, 2006. Accordingly, this Form 10-K/A should be read in conjunction with the original Form 10-K and the Company’s filings made with the Securities and Exchange Commission subsequent to the filing of the original Form 10-K including any amendments to those filings.

The complete texts of Items 1, 1A, 2 and 7 are set forth herein, including those portions of the text that have not been amended from that set forth in the original form 10-K. The only changes are described in items (a) through (e) in the second preceding paragraph above.

3

PART I

To aid readers unfamiliar with the terms commonly used in the coal industry, a glossary of selected terms is provided at the end of “Item 1. Business.”

Unless the context otherwise indicates, as used in this Annual Report on Form 10-K (“10-K”) the terms “we” “our” “us” and similar terms refer to Foundation Coal Holdings, Inc. and its consolidated subsidiaries. For purposes of all financial disclosure contained herein, RAG American Coal Holding, Inc. is the predecessor to Foundation Coal Holdings, Inc. We and our indirect subsidiary, Foundation Coal Corporation, were formed to acquire the North American coal mining assets of RAG Coal International AG, which acquisition closed on July 30, 2004 (the “Acquisition”). All references to Foundation Coal Holdings, Inc., including the business description, operating data and financial data, excludes RAG Coal International AG’s former Colorado operations, which were sold to a third party on April 15, 2004 and are accounted for herein as discontinued operations. On December 9, 2004, we completed an initial public offering of 24,121,900 shares of our common stock which we refer to herein as the Initial Public Offering (“IPO”). Certain statements in this 10-K are forward-looking statements. To facilitate trend analysis we compare the historical financial data of Foundation Coal Holdings, Inc. (the Successor) for the year ended December 31, 2005 and of RAG American Coal Holding, Inc. (the Predecessor) for the year ended December 31, 2003 with the “non-GAAP combined” financial data for the year ended December 31, 2004. Non-GAAP combined financial data for the year ended December 31, 2004 are determined by adding the historical amounts of the Predecessor for the period from January 1, 2004 through July 29, 2004 with the corresponding amounts of the Successor for the five month operating period ended December 31, 2004. Non-GAAP combined amounts for the year ended December 31, 2004 are not recognized measures under GAAP and do not purport to be alternatives to GAAP operating measures. Non-GAAP combined amounts are not indicative of the operating results of Foundation Coal Holdings, Inc. because of the significant difference in basis between the Successor and Predecessor caused by the acquisition on July 30, 2004 and its impact on income from operations. Management believes that the discussion of non-GAAP combined operating results is important to the readers of the financial statements to understand key operating trends over the normal operating cycle years 2005, 2004 and 2003. Non-GAAP combined amounts are reconciled to the underlying historical GAAP basis financial statements on page 47.

ITEM 1. BUSINESS

Overview

We are the fifth largest coal producer in the United States. We operate a diverse group of thirteen mines located in Wyoming, Pennsylvania, West Virginia and Illinois. For the year ended December 31, 2005, we sold 68.8 million tons of coal, including 66.3 million tons that were produced and processed at our operations. As of December 31, 2005, we had approximately 1.7 billion tons of proven and probable coal reserves. We are also involved in marketing coal produced by others to supplement our own production and, through blending, provide our customers with coal qualities beyond those available from our own production. We purchased and resold 2.5 million tons of coal in 2005.

We are primarily a supplier of steam coal to U.S. utilities for use in generating electricity. We also sell steam coal to industrial plants. Steam coal sales accounted for 97% of our coal sales volume and 92% of our coal sales revenue in 2005. We also sell metallurgical coal to steel producers; metallurgical sales accounted for 3% of our coal sales volume and 8% of our coal sales revenue in 2005.

As of December 31, 2005, we had a total sales backlog of over 330 million tons of coal, and our coal supply agreements have remaining terms ranging from one to 16 years. For 2005, based on sales revenues we sold approximately 79% of our sales volume under long-term coal supply agreements. We consider sales commitments with a duration of twelve months or longer as a “long-term” contract as opposed to spot sales agreements with a duration less than twelve months. As of January 24, 2006, we had sales and price commitments for approximately 96% of our planned 2006 production, approximately 75% of our planned 2007 production, approximately 50% of our planned 2008 production and approximately 37% of our planned 2009 production.

4

Competitive Strengths

We believe that the following competitive strengths enhance our prominent market position in the United States:

We are the fifth largest coal producer in the United States and have significant coal reserves. Based on 2005 production of 66.3 million tons, we are the fifth largest coal producer in the United States. As of December 31, 2005, we controlled approximately 1.7 billion tons of proven and probable coal reserves. Based on these reserve estimates and our actual rate of production during the year ended December 31, 2005, we have a total reserve life of approximately 26 years.

We have a diverse portfolio of coal-mining operations and reserves. We operate a total of 13 mines in the Powder River Basin, Northern Appalachia, Central Appalachia and the Illinois Basin, selling coal to dozens of domestic and foreign electric utilities, steel producers and industrial users. We are the only producer with significant operations and major reserve blocks in both the Powder River Basin and Northern Appalachia, two U.S. coal production regions for which future demand is expected to increase by approximately 2.0% annually through 2030, according to the Energy Information Administration (“EIA”). We believe that this geographic diversity provides us with a significant competitive advantage, allowing us to source coal from multiple regions to meet the needs of our customers and reduce their transportation costs.

We operate highly productive mines and have had strong EBITDA margins. We believe our focus on productivity has helped contribute to our strong EBITDA margins for fiscal years ended 2002, 2003, 2004 and 2005. Our strategic investment in equipment and technology has increased the efficiency of our operations, which we believe reduces our costs and provides us with a competitive advantage. Maintaining our low-cost position enables us to maximize our profitability in all coal pricing environments.

We are a recognized industry leader in safety and environmental performance. Our focus on safety and environmental performance results in a lower likelihood of disruption of production at our mines, which leads to higher productivity and improved financial performance. We operate some of the nation’s safest mines, with 2005 injury incident rates, as tracked by the Mine Safety and Health MSHA, below industry averages.

We have long-standing relationships and long-term contracts with many of the largest coal-burning utilities in the United States. We supply coal to numerous power plants operated by a diverse group of electricity generators across the country. We believe we have a reputation for reliability and superior customer service that has enabled us to solidify our customer relationships.

Our management team has a track record of success during our long operating history. Our management team has a proven record of generating free cash flow, increasing productivity, reducing costs, developing and maintaining long-standing customer relationships and effectively positioning us for future growth and profitability. We operated as a stand-alone subsidiary of privately held RAG Coal International AG from 1999 until becoming an independent company on July 30, 2004. Our senior executives have an average of approximately 25 years of experience in the coal industry, including an average of 16 years of experience operating our assets when owned by us and our predecessors, and have the management and organizational capability to successfully operate an independent public company.

Business Strategy

Our objective is to increase shareholder value through sustained earnings and cash flow growth. Our key strategies to achieve this objective are described below:

Maintaining our commitment to operational excellence as a low-cost producer. We seek to maintain our productivity leadership with an emphasis on lowering costs by continuing to invest selectively in new equipment and advanced technologies, such as our previous investments in underground diesel, increased longwall face widths and a larger shield system. We will continue to focus on profitability and efficiency by leveraging our significant economies of scale, large fleet of mining equipment, information technology systems and coordinated purchasing and land management functions. In addition, we continue to focus on productivity through our culture of workforce involvement by leveraging our strong base of experienced, well-trained employees.

5

Capitalizing on favorable industry dynamics through an opportunistic approach to selling our coal. The fundamentals of the current U.S. coal market are among the strongest in the past decade resulting in a favorable coal pricing environment which, based on current coal forward prices, we believe will continue for the foreseeable future. We employ an opportunistic approach to selling our coal, including the use of long-term sales commitments for a portion of our future production while maintaining uncommitted planned production to capitalize on favorable future pricing environments.

Selectively expanding our production and reserves. Given our broad scope of operations and expertise in mining in each of the major coal-producing regions in the United States, we believe that we are well-situated to capitalize on the expected continued growth in U.S. and international coal consumption by evaluating growth opportunities, including (i) expansion of production capacity at our existing mining operations, (ii) further development of existing significant reserve blocks in Northern Appalachia and Central Appalachia, and (iii) potential strategic acquisition opportunities that arise in the United States or internationally. We will prudently act to expand our reserves when appropriate. For example, we currently plan to seek to increase our reserve position by obtaining mining rights to federal coal reserves adjoining our current operations in Wyoming through the Lease By Application (“LBA”) process.

Continuing to provide a mix of coal types and qualities to satisfy our customers’ needs. By having operations and reserves in the four major coal producing regions, we are able to source coal from multiple mines to meet the needs of our domestic and international customers. Our broad geographic scope and mix of coal qualities provide us with the opportunity to work with many leading electricity generators, steel companies and other industrial customers across the country.

Continuing to focus on excellence in safety and environmental stewardship. We intend to maintain our recognized leadership in operating some of the safest mines in the United States and in achieving environmental excellence. Our ability to minimize lost-time injuries and environmental violations improves our operating efficiency, which directly improves our cost structure and financial performance.

History

Amoco Minerals Company was incorporated in Delaware on September 2, 1969, as a subsidiary of Amoco Corporation. The name was changed to Cyprus Minerals Company on May 24, 1985 and then spun-off from Amoco Corporation in July of 1985.

Cyprus Minerals Company merged with and into AMAX, Inc., a New York corporation, on November 15, 1993, with Cyprus Minerals Company being the surviving corporation under the name Cyprus Amax Minerals Company.

On June 30, 1999, Cyprus Amax Minerals Company and its subsidiary, Amax Energy Inc., sold the stock of Cyprus Amax Coal Company and all of its subsidiaries consisting of its remaining coal properties to RAG International Mining GmbH (now RAG Coal International AG (“RAG”)).

Foundation Coal Holdings, LLC was formed on February 9, 2004, by a group of investors for the purpose of acquiring the United States coal properties owned by RAG Coal International AG. A Stock Purchase Agreement was signed on May 24, 2004.

Foundation Coal Holdings, LLC, through its subsidiary, Foundation Coal Corporation, and pursuant to the Stock Purchase Agreement, completed the Acquisition of 100% of the outstanding common shares of RAG American Coal Holding, Inc. and its subsidiaries from RAG Coal International AG, on July 30, 2004 (the “Transaction”).

Foundation Coal Holdings, LLC, merged on August 17, 2004 into its subsidiary, Foundation Coal Holdings, Inc., a Delaware corporation that was formed on July 19, 2004. Foundation Coal Holdings, Inc. was the surviving entity in this merger. On December 9, 2004, we completed the IPO of Foundation Coal Holdings, Inc.

6

Coal Mining Techniques

We use four different mining techniques to extract coal from the ground: longwall mining, room-and-pillar mining, truck-and-shovel mining and truck and front-end loader mining.

Longwall Mining

We utilize longwall mining techniques at our Cumberland and Emerald mines in Pennsylvania. Longwall mining is the most productive and safest underground mining method used in the United States. A rotating drum is trammed mechanically across the face of coal, and a hydraulic system supports the roof of the mine while the drum advances through the coal. Chain conveyors then move the loosened coal to a standard underground mine conveyor system for delivery to the surface. Continuous miners are used to develop access to long rectangular blocks of coal which are then mined with longwall equipment, allowing controlled subsidence behind the advancing machinery. Longwall mining is highly productive and most effective for large blocks of medium to thick coal seams. High capital costs associated with longwall mining demand large, contiguous reserves. Ultimate seam recovery of in-place reserves using longwall mining is much higher than the room-and-pillar mining underground technique. All of the raw coal mined at our longwall mines is washed in preparation plants to remove rock and impurities.

Room-and-Pillar Mining

Our Kingston, Laurel Creek and Rockspring mines in West Virginia and our Wabash mine in Illinois utilize room-and-pillar mining methods. In this type of mining, main airways and transportation entries are developed and maintained while remote-controlled continuous miners extract coal from so-called rooms by removing coal from the seam, leaving pillars to support the roof. Shuttle cars are used to transport coal to the conveyor belt for transport to the surface. This method is more flexible and often used to mine smaller coal blocks or thin seams. Ultimate seam recovery of in-place reserves is typically less than that achieved with longwall mining. Much of this production is also washed in preparation plants before it becomes saleable clean coal.

Truck-and-Shovel Mining and Truck and Front-End Loader Mining

We utilize truck-and-shovel mining methods in both of our mines in the Powder River Basin. We utilize the truck and front-end loader method at our surface mines in West Virginia (the “Pioneer Mines”). These methods are similar and involve using large, electric or hydraulic-powered shovels or diesel-powered front-end loaders to remove earth and rock (overburden) covering a coal seam which is later used to refill the excavated coal pits after the coal is removed. The loading equipment places the coal into haul trucks for transportation to a preparation plant or loadout area. Ultimate seam recovery of in-place reserves on average exceeds 90%. This surface-mined coal rarely needs to be cleaned in a preparation plant before sale. Productivity depends on overburden and coal thickness (strip ratio), equipment utilized and geologic factors.

Business Environment

Coal is an abundant, efficient and affordable natural resource used primarily to provide fuel for the generation of electric power. World-wide recoverable coal reserves are estimated to be approximately 1.0 trillion tons. The United States is one of the world’s largest producers of coal and has approximately 27% of global coal reserves, representing over 200 years of supply based on current usage rates. According to the U.S. Department of Energy, the energy content of the United States coal reserves exceeds that of all the known oil supplies in the world.

Coal Markets. Coal is primarily consumed by utilities to generate electricity. It is also used by steel companies to make steel products and by a variety of industrial users to heat and power foundries, cement plants, paper mills, chemical plants and other manufacturing and processing facilities. In general, coal is characterized by end use as either steam coal or metallurgical coal. Steam coal is used by electricity generators and by industrial facilities to produce steam, electricity or both. Metallurgical coal is refined into coke, which is used in the production of steel. Over the past quarter century, total annual coal consumption in the United States has nearly doubled to approximately 1.1 billion tons in 2005. The growth in the demand for coal has coincided with an increased demand for coal from electric power generators.

7

The following table sets forth demand trends for United States coal by consuming sector as projected by the EIA for the periods indicated (totals may not foot due to rounding).

| | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | |

| | | Actual | | Preliminary(1) | | Projected(2) | | Annual Growth | |

Consumption by Sector | | 2002 | | 2003 | | 2004 | | 2005 | | 2010 | | 2020 | | 2004-2010 | | | 2010-2025 | |

| | | (tons in millions) | |

Electric Generation | | 978 | | 1,005 | | 1,016 | | 1,051 | | 1,140 | | 1,235 | | 1.9 | % | | 0.8 | % |

Industrial | | 61 | | 61 | | 62 | | 64 | | 66 | | 66 | | 1.1 | % | | 0.0 | % |

Steel Production | | 24 | | 24 | | 24 | | 24 | | 23 | | 22 | | (0.6 | )% | | (0.5 | )% |

Coal-to-Liquids Processes | | 0 | | 0 | | 0 | | 0 | | 0 | | 62 | | N/A | | | N/A | |

Residential/Commercial | | 4 | | 4 | | 5 | | 4 | | 4 | | 4 | | (0.4 | )% | | 0.0 | % |

Export | | 40 | | 43 | | 48 | | 50 | | 41 | | 19 | | 0.4 | % | | (7.5 | )% |

| | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | |

Total | | 1,106 | | 1,138 | | 1,155 | | 1,194 | | 1,274 | | 1,408 | | 1.8 | % | | 1.0 | % |

| | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | |

| (1) | Preliminary data estimates for 2005 are based on data published in the EIA’s Quarterly Coal Report through the third quarter of 2005 and output from the EIA’s National Energy Modeling System. |

| (2) | Projected 2004-2005 Data per EIA Annual Energy Outlook 2006 |

The nation’s power generation infrastructure is largely coal-fired. As a result, coal has consistently maintained a 49% to 53% market share during the past 10 years, principally because of its relatively low cost, reliability and abundance. Coal is the lowest cost fossil fuel used for base-load electric power generation, being considerably less expensive than natural gas or oil. Coal-fired generation is also competitive with nuclear power generation especially on a total cost per megawatt-hour basis. The production of electricity from existing hydroelectric facilities is inexpensive, but its application is limited both by geography and susceptibility to seasonal and climatic conditions. Non-hydropower renewable power generation accounts for only 1.4% of all the electricity generated in the United States, and wind and solar power—the alternative fuel sources that may provide more environmental benefits—represent less than 1% of United States power generation.

Coal consumption patterns are also influenced by the demand for electricity, governmental regulation impacting power generation, technological developments and the location, availability and cost of other fuels such as natural gas, nuclear and hydroelectric power.

Coal’s primary advantages are its relatively low cost and availability compared to other fuels used to generate electricity. Based on data available through November 2005, Global Energy Advisors (“GEA”), a commonly used authoritative resource for industry commodity pricing, has estimated the average total production costs of electricity, using coal and competing generation alternatives, as follows:

| | | |

Electrical Generation Type | | Cost per

Megawatt Hour |

Natural Gas | | $ | 75.29 |

Oil | | $ | 78.34 |

Renewables* | | $ | 25.01 |

Coal | | $ | 21.21 |

Nuclear | | $ | 20.21 |

Hydroelectric | | $ | 7.43 |

| * | Includes: Energy generation from wind, solar, biomass, geothermal, tidal and wave sources. |

8

Coal Production. United States coal production was approximately 1.1 billion tons in 2005. The following table, derived from data prepared by the EIA, sets forth production statistics in each of the four major coal producing regions for the periods indicated (totals may not foot due to rounding).

| | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | |

| | | Actual | | Preliminary(1) | | Projected(2) | | Annual Growth | |

Consumption by Sector | | 2002 | | 2003 | | 2004 | | 2005 | | 2010 | | 2025 | | 2004-2010 | | | 2010-2025 | |

| | | (tons in millions) | |

Powder River Basin | | 397 | | 400 | | 421 | | 446 | | 486 | | 661 | | 2.4 | % | | 2.1 | % |

Central Appalachia | | 249 | | 231 | | 233 | | 214 | | 202 | | 156 | | (2.4 | )% | | (1.7 | )% |

Northern Appalachia | | 140 | | 137 | | 148 | | 161 | | 202 | | 216 | | 5.3 | % | | 0.5 | % |

Illinois Basin | | 96 | | 92 | | 94 | | 102 | | 133 | | 180 | | 5.9 | % | | 2.0 | % |

Other | | 223 | | 223 | | 228 | | 222 | | 239 | | 318 | | 0.8 | % | | 1.9 | % |

| | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | |

Total | | 1,105 | | 1,083 | | 1,125 | | 1,145 | | 1,261 | | 1,530 | | 1.9 | % | | 1.3 | % |

| | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | |

| (1) | Preliminary data estimates for 2005 are based on data published in the EIA’s Quarterly Coal Report through the third quarter of 2005 and output from the EIA’s National Energy Modeling System. |

| (2) | Projected 2004-2025 Data per EIA Annual Energy Outlook 2006. |

Coal Regions. Coal is mined from coal fields throughout the United States, with the major production centers located in the Western United States, Northern and Central Appalachia and the Illinois Basin. The quality of coal varies by region. Heat value and sulfur content are two of the most important coal characteristics in measuring quality and determining the best end use of particular coal types.

Competition. The coal industry is intensely competitive. The most important factors on which we compete are coal price at the mine, coal quality and characteristics, transportation costs from the mine to the customer and the reliability of supply. Demand for coal and the prices that we will be able to obtain for our coal are closely linked to coal consumption patterns of the domestic electric generation industry, which are influenced by factors beyond our control. Some of these factors include the demand for electricity, which is significantly dependent upon economic activity and summer and winter temperatures in the United States, government regulation, technological developments and the location, availability, quality and price of competing sources of coal, alternative fuels such as natural gas, oil and nuclear, and alternative energy sources such as hydroelectric power.

Transportation Cost. Coal used for domestic consumption is generally sold free on board at the mine, and the purchaser normally bears the transportation costs. Export coal, however, is usually sold at the loading port, and coal producers are responsible for shipment to the export coal-loading facility, with the buyer paying the ocean freight.

Most electric generators arrange long-term shipping contracts with rail or barge companies to assure stable delivered costs. Transportation can be a large component of a purchaser’s total cost. Although the purchaser pays the freight, transportation costs still are important to coal mining companies because the purchaser may choose a supplier largely based on cost of transportation. According to the National Mining Association (“NMA”), railroads account for nearly two-thirds of total United States coal shipments, while river barge movements account for an additional 20%. Trucks and overland conveyors haul coal over shorter distances, while barges, Great Lake carriers and ocean vessels move coal to markets served by water. Most coal mines are served by a single rail company, but some are served by two competing rail carriers. Rail competition is important because rail costs can constitute up to 75% of the delivered cost of coal in various markets.

Coal Characteristics

In general, coal of all geological composition is characterized by end use as either steam coal or metallurgical coal. Heat value and sulfur content are two of the most important variables in the profitable marketing and transportation of steam coal, while ash, sulfur and various coking characteristics are important variables in the profitable marketing and transportation of metallurgical coal. We mine, process, market and transport bituminous and sub-bituminous coal, characteristics of which are described below.

9

Heat Value

The heat value of coal is commonly measured in British thermal units, or “Btus.” A Btu is the amount of heat needed to raise the temperature of one pound of water by one degree Fahrenheit. Coal found in the eastern and midwestern regions of the United States tends to have a higher heat value than coal found in the western United States.

Bituminous coal has a heat value that ranges from 10,500 to 14,000 Btu/lb. This coal is located primarily in our mines in Northern and Central Appalachia and in the Illinois Basin, and is the type most commonly used for electric power generation in the United States. Bituminous coal is used for utility and industrial steam purposes, and includes metallurgical coal, a feed stock for coke, which is used in steel production.

Sub-bituminous coal has a heat value that ranges from 7,800 to 9,500 Btu/lb. Our sub-bituminous reserves are located in Wyoming. Sub-bituminous coal is used almost exclusively by electric utilities and some industrial consumers.

Sulfur Content

Sulfur content can vary from seam to seam and sometimes within each seam. When coal is burned, it produces sulfur dioxide, the amount of which varies depending on the chemical composition and the concentration of sulfur in the coal. Compliance coal is coal which, when burned, emits 1.2 pounds or less of sulfur dioxide per million Btus and complies with the requirements of the Clean Air Act. Low sulfur coal is coal which, when burned, emits 1.6 pounds or less of sulfur dioxide per million Btus.

Sub-bituminous coal typically has a lower sulfur content than bituminous coal, but some of our bituminous coal in West Virginia also has a low sulfur content.

High sulfur coal can be burned in plants equipped with sulfur-reduction technology, such as scrubbers, which can reduce sulfur dioxide emissions. Plants without scrubbers can burn high sulfur coal by blending it with lower sulfur coal, or by purchasing emission allowances on the open market, which permit the user to emit a ton of sulfur dioxide. More than 15,000 megawatts of coal-based generating capacity has been retrofitted with scrubbers since the beginning of Phase I of the Clean Air Act. Furthermore, utilities have announced plans to scrub an additional 77,000 megawatts by 2010. Additional scrubbing will provide new market opportunities for our noncompliance coals. All new coal-fired generation plants built in the United States are expected to use clean coal-burning technology.

Operations

As of December 31, 2005, we operated a total of 13 mines located in Wyoming, Pennsylvania, West Virginia and Illinois. We currently own most of the equipment utilized in our mining operations.

10

The following table provides summary information regarding our principal mining complexes as of December 31, 2005.

| | | | | | | | | | |

Mining Complex | | Number of Mines | | Type of Mine | | Mining Technology | | Transportation | | Tons Sold in 2005 |

| | | | | | | | | | | (in millions) |

Wyoming | | | | | | | | | | |

Belle Ayr | | 1 | | Surface | | Truck-and-Shovel | | BNSF, UP | | 19.5 |

Eagle Butte | | 1 | | Surface | | Truck-and-Shovel | | BNSF | | 24.1 |

| | | | | |

Pennsylvania | | | | | | | | | | |

Cumberland | | 1 | | Underground | | Longwall | | Barge | | 7.0 |

Emerald | | 1 | | Underground | | Longwall | | CSX, NS | | 6.7 |

| | | | | |

West Virginia | | | | | | | | | | |

Kingston | | 2 | | Underground | | Room-and-Pillar | | Barge, CSX, NS | | 1.2 |

Laurel Creek | | 3 | | Underground | | Room-and-Pillar | | Barge, CSX | | 1.5 |

Rockspring | | 1 | | Underground | | Room-and-Pillar | | NS | | 3.0 |

Pioneer | | 2 | | Surface | | Truck and Front-End Loader | | Barge, NS | | 1.6 |

Purchased and resold coal | | | | | | | | | | 1.7 |

| | | | | |

Illinois | | | | | | | | | | |

Wabash | | 1 | | Underground | | Room-and-Pillar | | NS | | 1.7 |

| | | | | |

Other | | | | | | | | | | |

Purchased and resold coal | | — | | | | | | | | 0.8 |

| | | | | | | | | | |

Total | | 13 | | | | | | | | 68.8 |

| | | | | | | | | | |

| | |

| BNSF = Burlington Northern Santa Fe Railroad | | NS = Norfolk Southern Railroad |

| CSX = CSX Railroad | | UP = Union Pacific Railroad |

Note: The tonnage shown for each mine represents coal mined, processed and shipped from our active operations. Kingston and Pioneer tons sold include a total of 1.3 million tons of metallurgical coal. The tonnage shown in the two categories labeled purchased and resold includes 0.8 million tons of metallurgical coal.

11

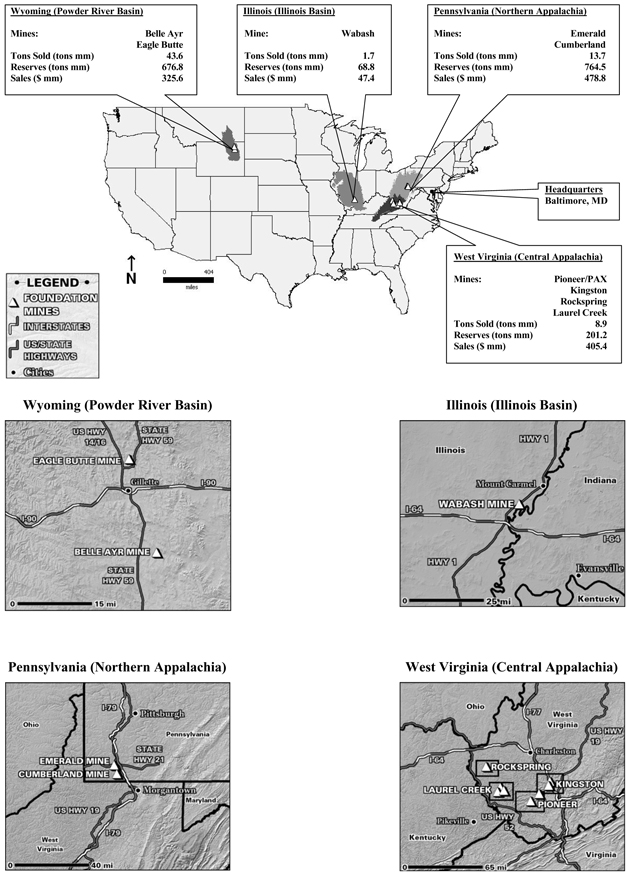

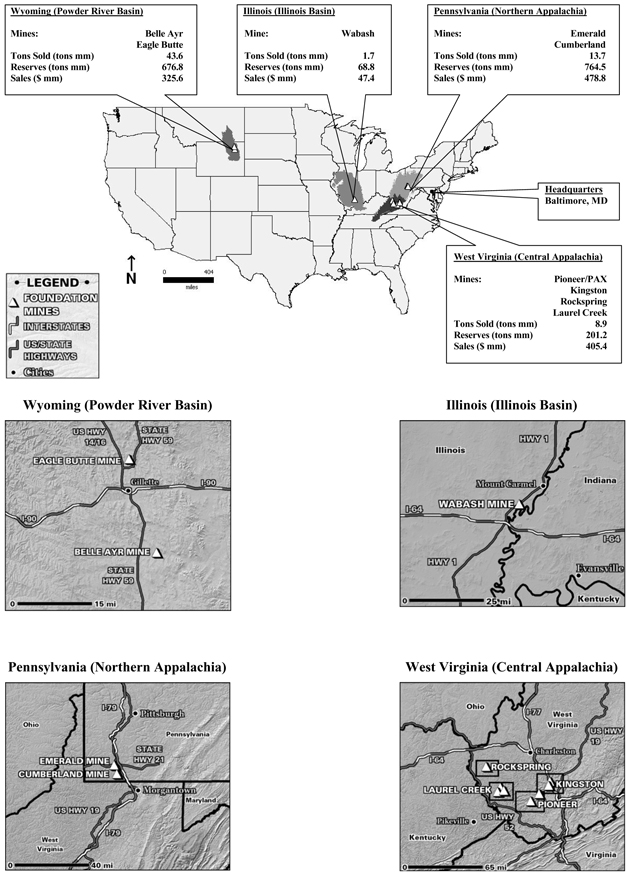

The following map outlines our operations, sales of produced coal, tons sold and reserves as of December 31, 2005.

12

The following provides a description of the operating characteristics of the principal mines and reserves of each of our mining operations.

Wyoming Operations

We control approximately 676.8 million tons of coal reserves in the Powder River Basin, the largest and fastest growing U.S. coal-producing region. Our subsidiaries, Foundation Coal West, Inc. and Foundation Wyoming Land Company, own and manage two sub-bituminous, low sulfur, non-union surface mines that sold 43.6 million tons of coal in 2005, or 66% of our total production volume. The two mines employ approximately 510 salaried and hourly employees. Our Powder River Basin mines have produced over 900 million tons of coal since 1972.

Belle Ayr Mine

The Belle Ayr mine, located approximately 18 miles southeast of Gillette, Wyoming, extracts coal from the Wyodak-Anderson Seam, which averages 75 feet thick, using the truck-and-shovel mining method. Belle Ayr shipped 19.5 million tons of coal in 2005. The mine sells 100% of raw coal mined and no washing is necessary. Belle Ayr has approximately 330.7 million tons of reserves. The reserves at Belle Ayr will sustain projected production for approximately 13 years. We plan to apply to lease several hundred million tons of surface mineable, unleased federal coal that adjoins Belle Ayr’s property under the LBA process. If we prevail in the bidding process and obtain these leases we will be able to extend the life of the mine. Belle Ayr has the advantage of shipping its coal on both of the major western railroads, the Burlington Northern Santa Fe Railroad and the Union Pacific Railroad.

Eagle Butte Mine

The Eagle Butte mine, located approximately eight miles north of Gillette, Wyoming, extracts coal from the Roland and Smith Seams, which total 100 feet thick, using the truck-and-shovel mining method. Eagle Butte shipped 24.1 million tons of coal in 2005. The mine sells 100% of the raw coal mined and no washing is necessary. Eagle Butte has approximately 346.1 million tons of reserves. The reserves will sustain projected production levels for 14 years. We have applied to lease approximately 240 million tons of surface mineable, unleased federal coal adjoining the western boundary of the mine property. The LBA sale is scheduled for 2007. If we prevail in the bidding process and obtain this lease, we will be able to extend the mine’s life by approximately an additional 10 years, based on the mine’s 2005 rate of production. Coal from Eagle Butte is shipped on the Burlington Northern Santa Fe Railroad to power plants located throughout the Midwest and the South.

Pennsylvania Operations

We control approximately 764.4 million tons of contiguous reserves in Northern Appalachia. Approximately 200.4 million tons are assigned to active mines. Approximately 564.0 million tons are unassigned. A portion of these unassigned reserves is accessible through our currently active mines. Our Pennsylvania mines are located in the southwestern part of the state, approximately 60 miles south of Pittsburgh. Both mines operate in the Pittsburgh No. 8 Seam, the dominant coal-producing seam in the region, which is six to eight feet thick on these properties. The Pennsylvania operations consist of the Cumberland and the Emerald mining complexes, which collectively shipped 13.7 million tons in 2005 using longwall mining systems supported by continuous mining methods. The mines sell high Btu, medium sulfur coal primarily to eastern utilities. The hourly work force at each mine is represented by the United Mine Workers of America (“UMWA”).

Cumberland Mine

The Cumberland mining complex, located approximately 12 miles south of Waynesburg, Pennsylvania, was established in 1977. Cumberland shipped 7.0 million tons of coal in 2005. As of December 31, 2005, Cumberland had assigned reserves of 102.3 million tons. All of the coal at Cumberland is processed through a preparation plant before being loaded onto Cumberland’s owned and operated railroad for transportation to the Monongahela River dock site. At the dock site, coal is then loaded into barges for transportation to river-served utilities or to other docks for subsequent rail shipment to non-river-served utilities. The mine can also ship a portion of its production via truck. Cumberland has approximately 611 salaried and hourly employees.

13

Emerald Mine

The Emerald mining complex, located approximately two miles south of Waynesburg, Pennsylvania, was established in 1977. As of December 31, 2005, Emerald had assigned reserves of approximately 98.1 million tons. Emerald shipped 6.7 million tons of coal in 2005. Emerald has the ability to store clean coal and blend variable sulfur products to meet customer requirements. All of Emerald’s coal is processed through a preparation plant before being loaded into unit trains operated by the Norfolk Southern Railroad or the CSX Railroad. The mine also has the option to ship a portion of its coal by truck. Approximately 577 salaried and hourly employees work at Emerald.

West Virginia Operations

Our subsidiaries operate four mining facilities located in West Virginia in the Central Appalachia region: Kingston, Laurel Creek, Rockspring and Pioneer. The Kingston, Laurel Creek and Rockspring facilities are all underground mining complexes that use room-and-pillar mining technology to develop and extract coal. The Pioneer Mines operates two surface mines utilizing truck/loader systems to extract coal from multiple seams. Our West Virginia operations have approximately 76.7 million tons of reserves that are assigned to current operations and approximately 124.5 million tons of reserves that are unassigned and are being held for future development. Except for the two surface mines, all of the raw coal is processed through preparation plants before transportation to market. Production from the mines is typically low sulfur, high Btu coal. In 2005, our West Virginia mines collectively sold 8.9 million tons of produced and purchased coal. Our West Virginia mines ship coal by either the Norfolk Southern Railroad or the CSX Railroad or by barge on the Kanawha and Big Sandy Rivers. These operations serve a diversified customer base, including regional and national customers. We also own and operate the Rivereagle loading facility on the Big Sandy River in Boyd County, Kentucky.

Our West Virginia operations have approximately 792 non-union salaried and hourly employees. In November 2003, a UMWA election was held at the Rockspring mining facility, the outcome of which is pending a decision of the National Labor Relations Board (the “NLRB”). If the NLRB finds that the UMWA was properly elected, approximately 248 employees at the Rockspring facility would become UMWA members.

Kingston Mines

The Kingston complex consists of two mines, Kingston #1 and Kingston #2, located in Fayette County and Raleigh County, respectively. Kingston #1 mines the Glen Alum Seam and Kingston #2 mines the Douglas Seam. In 2005, the Kingston complex shipped 1.1 million tons and as of December 31, 2005 had approximately 12.1 million tons of reserves of which approximately 8.9 million tons are assigned and approximately 3.2 million tons are unassigned. Kingston sells coal primarily into the metallurgical market for domestic steel plants. The coal is trucked to the Kanawha River for shipment by barge or delivered via the CSX Railroad or the Norfolk Southern Railroad for shipment by rail.

Laurel Creek Mines

The Laurel Creek mining complex consists of three underground mines, #1, #4 and #6 operating in the Coalburg 5 Block and Cedar Grove seams respectively, and a preparation plant located in Logan and Mingo Counties. In 2005, the mines shipped 1.5 million tons and as of December 31, 2005 had approximately 11.7 million tons of assigned reserves and approximately 15.3 million tons of unassigned reserves. The coal is shipped by truck primarily to our Rivereagle dock, other third-party docks or a rail siding on the CSX Railroad.

Rockspring Mine

Rockspring Development, Inc. operates a large multiple section mining complex in Wayne County called Camp Creek that produces coal from the Coalburg Seam. The complex shipped 3.0 million tons of coal in 2005. Assigned and unassigned coal reserves totaled approximately 44.3 million tons and 22.7 million tons, respectively. Rockspring has a mine site rail loadout. The coal is transported on the Norfolk Southern Railroad, primarily to southeastern utilities. The mine can also ship a portion of its production by truck.

14

Pioneer Mines

Pioneer Fuel Corporation operates two active surface mines, Paynter Branch which is located in Wyoming County and Pax surface mine which is located in Raleigh County. These mines utilize front-end loaders with trucks to mine multiple seams. The Pioneer Mines shipped 1.5 million tons of primarily steam coal in 2005. As of December 31, 2005, the mines had assigned reserves of approximately 11.8 million tons with an additional 19.4 million tons of unassigned reserves. Based on 2005 production rates, we expect that the Paynter Branch mine has sufficient reserves to last approximately six years. We expect that the Pax mine has sufficient reserves to last approximately eight years. Coal from Paynter Branch is shipped by truck to a loading facility on the Norfolk Southern Railroad and then on to domestic utilities and exported to metallurgical coal customers. Coal from Pax is trucked to the Kanawha River for shipment by barge or may be transported by truck to an on-site loading facility utilized by Paynter Branch for rail shipment on the Norfolk Southern Railroad. The Pax mine is currently constructing an on-site loading facility which will allow loading on the CSX Railroad.

Illinois Operations

Wabash Mine

The Wabash Mine is a room-and-pillar operation, mining in the Illinois No. 5 seam, located in Wabash County, Illinois in the Illinois Basin just east of Keensburg. The mine shipped 1.7 million tons of steam coal in 2005. After cleaning in the preparation plant, the coal is shipped via the Norfolk Southern Railroad to power plants located in the Illinois Basin, in particular to the PSI Gibson Station in Owensville, Indiana, one of the largest power plants in the U.S.

The hourly work force at the Wabash Mine is represented by the UMWA. Wabash has approximately 268 salaried and hourly employees.

As of March 2006, we have existing commitments for most of the Wabash Mine production through 2009.

FutureGen Industrial Alliance, Inc.

We are a founding member of the FutureGen Industrial Alliance, Inc. This is a non-profit company that is partnering with the U.S. Department of Energy to facilitate the design, construction and operation of the world’s first near-zero emission coal-fueled power plant. The FutureGen plant will demonstrate advanced coal-based technologies to gasify coal and generate electricity, and also produce hydrogen to power fuel cells for transportation and other energy needs. The technology also will integrate the capture of carbon emissions with carbon sequestration, helping to address the issue of climate change as energy demand continues to grow worldwide. The alliance announced in December 2005 that it entered into a limited scope cooperative agreement with the U.S. Department of Energy to develop and site in the United States the cleanest coal-fueled power plant in the world with a target of zero emissions, hydrogen production and carbon dioxide sequestration capabilities. Activities for site selection and conceptual design are underway.

Long-Term Coal Supply Agreements

As of December 31, 2005, we had a total sales backlog of over 330 million tons of coal, and our coal supply agreements have remaining terms ranging from one to 16 years. For 2005, based on sales revenues we sold approximately 79% of our sales volume under long-term coal supply agreements with a duration of twelve months or longer. In 2005, we sold coal to over 100 electricity generating and industrial plants. Our primary customer base is in the United States. We expect to continue selling a significant portion of our coal under long-term supply agreements. Our strategy is to selectively renew, or enter into new, long-term supply contracts when we can do so at prices we believe are favorable. As of January 24, 2006, we had sales and price commitments for approximately 96% of our planned 2006 production, approximately 75% of our planned 2007 production, approximately 50% of our planned 2008 production and approximately 37% of our planned 2009 production. To the extent we do not renew or replace expiring long-term coal supply agreements, our future sales will be exposed to market fluctuations.

15

The terms of our coal supply agreements result from competitive bidding and extensive negotiations with customers. Consequently, the terms of these contracts vary significantly by customer, including price adjustment features, price reopener terms, coal quality requirements, quantity parameters, permitted sources of supply, future regulatory changes, extension options, force majeure, termination and assignment provisions.

Some of our long-term contracts provide for a predetermined adjustment to the stipulated base price at times specified in the agreement or at other periodic intervals to account for changes due to inflation or deflation. In addition, most of our contracts contain provisions to adjust the base price due to new statutes, ordinances or regulations that impact our costs related to performance of the agreement. Additionally, some of our contracts contain provisions that allow for the recovery of costs impacted by modifications or changes in the interpretations or application of any applicable statute by local, state or federal government authorities.

Price reopener provisions are present in some of our long-term contracts. These provisions may allow either party to commence a renegotiation of the contract price at a pre-determined time. In a limited number of agreements, if the parties do not agree on a new price, either party has an option to terminate the contract. Under some of our contracts, we have the right to match lower prices offered to our customers by other suppliers.

Quality and volumes for the coal are stipulated in coal supply agreements, and in some instances buyers have the option to vary annual or monthly volumes. Most of our coal supply agreements contain provisions requiring us to deliver coal within certain ranges for specific coal characteristics such as heat content, sulfur, ash, hardness and ash fusion temperature. Failure to meet these specifications can result in economic penalties, suspension or cancellation of shipments or termination of the contracts.

Some of our contracts set out mechanisms for temporary reductions or delays in coal volumes in the event of a force majeure, including events such as strikes, adverse mining conditions, mine closures or serious transportation problems that affect us or unanticipated plant outages that may affect the buyer. More recent contracts stipulate that this tonnage can be made up by mutual agreement or at the discretion of the buyer. Many of our contracts contain similar clauses covering changes in environmental laws. We often negotiate the right to supply coal that complies with new environmental requirements to avoid contract termination.

In some of our contracts, we have a right of substitution, allowing us to provide coal from different mines as long as the replacement coal meets quality specifications and will be sold at the same delivered cost.

Sales and Marketing

Through our sales, trading and marketing entities, we sell coal produced by our diverse portfolio of operations, broker coal sales of other coal producers, both as principal and agent, trade coal and emission allowances and provide transportation-related services. Our sales, marketing, and trading affiliate, Foundation Energy Sales, Inc., employs staff to handle trading, transportation, market research, contract administration and risk/credit management activities.

Transportation

Coal consumed domestically is usually sold at the mine, and transportation costs are normally borne by the purchaser. Export coal is usually sold at the loading port, with purchasers paying ocean freight. Producers usually pay shipping costs from the mine to the port.

We depend upon rail, barge, trucking and other systems to deliver coal to markets. In 2005, our produced coal was transported from the mines to the customer primarily by rail, with the main rail carriers being the CSX, Norfolk Southern, Burlington Northern Sante Fe and the Union Pacific. The majority of our sales volume is shipped by rail, but a portion of our production is shipped by barge and truck. All coal from our Belle Ayr Mine in Wyoming is shipped by two competing railroads, the Burlington Northern Santa Fe Railroad and the Union Pacific Railroad, while output from our Eagle Butte operation moves via the Burlington Northern Santa Fe Railroad. The Wabash Mine in Illinois is serviced by the Norfolk Southern Railroad. The Pioneer, Kingston, Laurel Creek and Rockspring Mines in West Virginia are serviced by a combination of the Norfolk Southern Railroad and the CSX Railroad, as well as by truck and barge. In Pennsylvania, the Emerald Mine is serviced by the Norfolk Southern Railroad and the CSX Railroad and the Cumberland Mine is serviced by barge.

16

We believe we enjoy good relationships with rail carriers and barge companies due, in part, to our modern coal-loading facilities and the experience of our transportation and distribution employees.

Suppliers

We spend more than $400 million per year to procure goods and services in support of our business activities, excluding capital expenditures. Principal commodities include maintenance and repair parts and services, electricity, fuel, roof control and support items, explosives, tires, conveyance structure, ventilation supplies and lubricants. We use suppliers for a significant portion of our equipment rebuilds and repairs both on- and off-site, as well as construction and reclamation activities and to support computer systems.

Each of our regional mining operations has developed its own supplier base consistent with local needs. We have a centralized sourcing group for major supplier contract negotiation and administration, for the negotiation and purchase of major capital goods, and to support the business units. The supplier base has been relatively stable for many years, but there has been some consolidation. We are not dependent on any one supplier in any region. We promote competition between suppliers and seek to develop relationships with those suppliers whose focus is on lowering our costs. We seek suppliers who identify and concentrate on implementing continuous improvement opportunities within their area of expertise.

Technological Innovation

We have been active in identifying new technologies to improve productivity, lower unit costs and make operations safer. In addition, we have enlisted our suppliers to assist us in developing these new technologies.

Examples of new technological improvements in both our underground and surface operations include:

Two Meter Wide Shields. Cumberland is the first underground mine in the world to fully utilize 2.0 meter wide shields in place of the industry standard 1.75 meter shields. This has reduced the number of longwall shields by 14%, reduced the number of shields to move and reduced the number of components in the longwall system.

Longwall Face Extension. Our Pennsylvania operations have extended the longwall face from 1,000 feet to 1,250 feet and further extended the Emerald face to 1,450 feet in June 2005. These wider longwall faces improve coal recovery and reduce the ratio of continuous miner development work per unit of longwall coal extracted.

Real-Time Truck Dispatch. Our large western surface mines utilize 240 and 360 ton haul trucks. We were the first operator in the Powder River Basin to utilize a real-time dispatch system. The company estimates that this innovation has improved truck productivity by 10% by more fully utilizing the truck asset through automatically assigning the trucks to the shovels that have the greatest need for additional trucks.

Underground Diesel Equipment. We were the first mining company in Pennsylvania to utilize underground diesel equipment, thereby eliminating battery charging requirements and facilitating a continuous duty cycle.

Pumpable Cribs. Roof support is critical in any underground mine to maintain entry stability and safety. We pioneered the use of pumpable cribs which replaced the traditional wooden cribs in certain secondary support areas. The pumpable crib utilizes a low-density concrete that is mixed on the surface and then pumped underground into pre-fabricated forms. The hardened concrete has greater roof support density and a more uniform support base than wooden cribs. This process eliminated the need to haul wood blocks underground to build the cribs and has reduced accident exposure for our employees.

Real-Time Monitoring. The large surface mines use on-line equipment monitoring to increase haul truck payloads by 6%. Maintenance personnel can monitor equipment performance real time and detect problems early, thereby reducing maintenance costs and improving availability. The equipment operators also get immediate feedback on the performance characteristics of their equipment and operating conditions and thus can adjust their management of the equipment to maximize productivity and minimize costs and downtime.

17

Employees

As of December 31, 2005, we and our subsidiaries had approximately 2,900 employees. As of December 31, 2005, the UMWA represented approximately 40% of our employees, who produced approximately 23% of our coal sales volume during the fiscal year ended December 31, 2005. Relations with organized labor are important to our success and we believe our relations with our employees are satisfactory. Three mining operations (Cumberland, Emerald and Wabash) are signatories to the UMWA collective wage agreement negotiated between the Bituminous Coal Operators Association (the “BCOA”) and the UMWA in 2002. While our operations are not part of the BCOA, we have historically executed collective wage agreements patterned after the industry negotiated collective wage agreement with additional memoranda of understanding to handle local issues. The three wage agreements with the UMWA expire in early 2007, approximately three months after the industry-negotiated collective wage agreement expiration date of December 31, 2006.

ENVIRONMENTAL AND OTHER REGULATORY MATTERS

Federal, state and local authorities regulate the United States coal mining industry with respect to matters such as: employee health and safety; permitting and licensing requirements; emissions to air and discharges to water; plant and wildlife protection; the reclamation and restoration of mining properties after mining has been completed; the storage, treatment and disposal of wastes; remediation of contaminated soil, surface and groundwater; surface subsidence from underground mining; and the effects of mining on surface and groundwater quality and availability, and competing uses of adjacent, overlying or underlying lands such as for oil and gas activity, pipelines, roads and public facilities. These regulations and legislation (and judicial or agency interpretations thereof) have had, and will continue to have, a significant effect on our production costs and our competitive position. New laws and regulations, as well as future interpretations or different enforcement of existing laws, and regulations, may require substantial increases in equipment and operating costs to us and delays, interruptions, or a termination of operations, the extent of which we cannot predict. We intend to respond to these regulatory requirements and interpretations thereof at the appropriate time by implementing necessary modifications to facilities or operating procedures. When appropriate, we may also challenge actions in regulatory or court proceedings. Future legislation, regulations, interpretations or enforcement may also cause coal to become a less attractive fuel source. As a result, future legislation, regulations, interpretations or enforcement may adversely affect our mining operations, cost structure or the ability of our customers to use coal.

We endeavor to conduct our mining operations in compliance with all applicable federal, state, and local laws and regulations. However, violations occur from time to time. None of the violations identified or the monetary penalties assessed upon us in recent years has been material. It is possible that future liability under or compliance with environmental and safety requirements could have a material effect on our operations or competitive position. Under some circumstances, substantial fines and penalties, including revocation or suspension of mining permits, may be imposed under the laws described below. Monetary sanctions and, in severe circumstances, criminal sanctions may be imposed for failure to comply with these laws.

Mine Safety and Health

The Coal Mine Health and Safety Act of 1969 and the Federal Mine Safety and Health Act of 1977 impose stringent safety and health standards on all aspects of mining operations.

Also, most of the states in which we operate have state programs for mine safety and health regulation and enforcement. Collectively, federal and state safety and health regulation in the coal mining industry is perhaps the most comprehensive and pervasive system for protection of employee health and safety affecting any segment of U.S. industry. Regulation has a significant effect on our operating costs.

In early 2006, as a result of the Sago mine incident in West Virginia and other incidents in the coal mining industry, legislative and regulatory bodies at the state and federal levels as well as MSHA have promulgated or proposed various new statutes, rules and regulations relating to mine safety and rescue issues. At this time it is not possible to predict the effect that the new or proposed statutes, rules and regulations will have on our operating costs.

18

Black Lung

Under the Black Lung Benefits Revenue Act of 1977 and the Black Lung Benefits Reform Act of 1977, as amended in 1981, each coal mine operator must secure payment of federal black lung benefits to claimants who are current and former employees and to a trust fund for the payment of benefits and medical expenses to claimants who last worked in the coal industry prior to July 1, 1973. The trust fund is funded by an excise tax on production of up to $1.10 per ton for deep-mined coal and up to $0.55 per ton for surface-mined coal, neither amount to exceed 4.4% of the gross sales price. This tax is passed on to the purchaser under many of our coal supply agreements.

In December 2000, the Department of Labor amended regulations implementing the federal black lung laws to, among other things, establish a presumption in favor of a claimant’s treating physician and limit a coal operator’s ability to introduce medical evidence regarding the claimant’s medical condition. The number of claimants who are awarded benefits will increase, as will the amounts of those awards.

As of December 31, 2005, all of our various payment obligations for federal black lung benefits to claimants entitled to such benefits are made from a fully funded tax exempt trust established for that purpose. Based on actuarial reports and required funding levels, from time to time we may have to supplement the trust corpus to cover the anticipated liabilities going forward.

Coal Industry Retiree Health Benefit Act of 1992

The Coal Industry Retiree Health Benefit Act of 1992 (the “Coal Act”) provides for the funding of health benefits for certain UMWA retirees and their spouses or dependants. The Coal Act established the Combined Fund into which employers who are “signatory operators” are obligated to pay annual premiums for beneficiaries. The Combined Fund covers a fixed group of individuals who retired before July, 1 1976, and the average age of the retirees in this fund is approximately 80 years of age. Our premium obligations to the Combined Fund are approximately $1,500,000 per year. The Coal Act also created a second benefit fund, the 1992 Plan, for miners who retired between July 1, 1976 and September 30, 1994, and whose former employers are no longer in business to provide them retiree medical benefits. Companies with 1992 Plan liabilities also pay premiums into this plan. Our payment obligations to the 1992 Plan are approximately $1,000,000 per year. These per beneficiary premiums for both the Combined Fund and the 1992 Plan are adjusted annually based on various criteria such as the number of beneficiaries and the anticipated health benefit costs.

Environmental Laws

We and our customers are subject to various federal, state and local environmental laws. Some of the more material of these laws, discussed below, place stringent requirements on our coal mining operations. Federal and state regulations require regular monitoring of our mines and other facilities to ensure compliance.

Mining Permits and Necessary Approvals

Numerous governmental permits, licenses or approvals are required for mining and related operations. When we apply for these permits and approvals, we may be required to present data to federal, state or local authorities pertaining to the effect or impact our operations may have upon the environment. The requirements imposed by any of these authorities may be costly and time consuming and may delay commencement or continuation of mining operations. These requirements may also be added to, modified or re-interpreted from time to time. Regulations also provide that a mining permit or modification can be delayed, refused or revoked if an officer, director or a stockholder with a 10% or greater interest in the entity is affiliated with or is in a position to control another entity that has outstanding mining permit violations. Thus, past or ongoing violations of federal and state mining laws could provide a basis to revoke existing permits and to deny the issuance of additional permits.

In order to obtain mining permits and approvals from state regulatory authorities we must submit a reclamation plan for restoring, upon the completion of mining operations, the mined property to its prior or better condition, productive use or other permitted condition. Typically, we submit our necessary permit applications several months, or even years, before we plan to begin mining a new area. In the past, we have generally obtained our mining permits in time so as to be able to run our operations as planned. However, we cannot be sure that we will not experience difficulty or delays in obtaining mining permits in the future.

19

Surface Mining Control and Reclamation Act

The Surface Mining Control and Reclamation Act of 1977 (the “SMCRA”), which is administered by the Office of Surface Mining Reclamation and Enforcement (the “OSM”), establishes mining, environmental protection and reclamation standards for all aspects of surface mining as well as many aspects of deep mining. Where state regulatory agencies have adopted federal mining programs under the act, the state becomes the regulatory authority with primacy and issues the permits, but OSM maintains oversight. SMCRA stipulates compliance with many other major environmental statutes, including the federal Clean Air Act, Clean Water Act, Resource Conservation and Recovery Act (“RCRA”) and Comprehensive Environmental Response, Compensation and Liability Act (“CERCLA” or “Superfund”).

SMCRA permit provisions include requirements for coal prospecting; mine plan development; topsoil removal, storage and replacement; selective handling of overburden materials; mine pit backfilling and grading; protection of the hydrologic balance; subsidence control for underground mines; surface drainage control; mine drainage and mine discharge control and treatment; and re-vegetation. The permit application process is initiated by collecting baseline data to adequately characterize the pre-mine environmental condition of the permit area. This work includes surveys of cultural and historical resources, soils, vegetation, wildlife, assessment of surface and ground water hydrology, climatology, and wetlands. In conducting this work, we collect geologic data to define and model the soil and rock structures and coal that we will mine. We develop mining and reclamation plans by utilizing this geologic data and incorporating elements of the environmental data. The mining and reclamation plan incorporates the provisions of SMCRA, the state programs, and the complementary environmental programs that affect coal mining. Also included in the permit application are documents defining ownership and agreements pertaining to coal, minerals, oil and gas, water rights, rights of way and surface land.

Some SMCRA mine permits take over a year to prepare, depending on the size and complexity of the mine. Once a permit application is prepared and submitted to the regulatory agency, it goes through a completeness review and technical review. Public notice of the proposed permit is given that also provides for a comment period before a permit can be issued. Some SMCRA mine permits may take six months to two years or even longer to be issued. Regulatory authorities have considerable discretion in the timing of the permit issuance and the public and other agencies have rights to comment on and otherwise engage in the permitting process, including through intervention in the courts.

Before a SMCRA permit is issued, a mine operator must submit a bond or otherwise secure the performance of reclamation obligations. The Abandoned Mine Land Fund, which is part of SMCRA, requires a fee on all coal produced. The proceeds are used to reclaim mine lands closed prior to 1977. The current fee is $0.35 per ton on surface-mined coal and $0.15 per ton on deep-mined coal. There are proposals to modify this fee and the administration of the Abandoned Mine Land Fund, but any change is not expected to have a material adverse impact on our financial results.

Surety Bonds

Federal and state laws require us to obtain surety bonds to secure payment of certain long-term obligations including mine closure or reclamation costs, federal and state workers’ compensation costs, obligations under federal coal leases and other miscellaneous obligations. Many of these bonds are renewable on a yearly basis. In recent years, surety bond premium costs have increased and the market terms of surety bonds have generally become more unfavorable. In addition, the number of companies willing to issue surety bonds has decreased. We cannot predict the ability to obtain or the cost of bonds in the future.

Clean Air Act

The Clean Air Act, the Clean Air Act Amendments and the corresponding state laws that regulate the emissions of materials into the air affect coal mining operations both directly and indirectly. Direct impacts on coal mining and processing operations may occur through Clean Air Act permitting requirements and/or emission control requirements relating to particulate matter, such as fugitive dust, including future regulation of fine particulate matter measuring 10 micrometers in diameter or smaller. The Clean Air Act indirectly affects coal mining operations by extensively regulating the air emissions of sulfur dioxide, nitrogen oxides, particulates, mercury and other compounds emitted by coal-fueled electricity generating plants. Power plants will likely have to continue to install pollution control technology and upgrades. Power plants may be able to recover the costs for these upgrades

20

in the prices they charge for power, but this is not a certainty and state public utility commissions often control such rate matters. The Clean Air Act provisions and associated regulations are complex, lengthy and often being assessed for revisions or additions. In addition, one or more of the pertinent state or federal regulations issued as final are at this time, and may still continue to be, subject to current and future legal challenges in courts and the actual timing of implementation may remain uncertain. Some of the more material Clean Air Act requirements that may directly or indirectly affect our operations include the following:

| | • | | Acid Rain. Title IV of the Clean Air Act required a two-phase reduction of sulfur dioxide emissions by electric utilities. Phase II became effective in 2000 and applies to all coal-fired power plants generating greater than 25 megawatts. The affected electricity generators have sought to meet these requirements mainly by, among other compliance methods, switching to lower sulfur fuels, installing pollution control devices, reducing electricity generating levels or purchasing sulfur dioxide emission allowances. We cannot accurately predict the effect of these provisions of the Clean Air Act on us in future years. At this time, we believe that implementation of Phase II has resulted in an upward pressure on the price of lower sulfur eastern coals, and more demand for western coals, as coal-fired power plants continue to comply with the more stringent restrictions of Title IV. |

| | • | | Fine Particulate Matter and Ozone. The Clean Air Act requires the Environmental Protection Agency (“EPA”) to set standards, referred to as National Ambient Air Quality Standards (“NAAQS”), for certain pollutants. Areas that are not in compliance (referred to as “non-attainment areas”) with these standards must take steps to reduce emissions levels. In 1997, the EPA revised the NAAQS for particulate matter and ozone. Although previously subject to legal challenge, these revisions were subsequently upheld but implementation was delayed for several years. For ozone, these changes include replacement of the existing one-hour average standard with a more stringent eight-hour average standard in Phase 1 of the Ozone Rule. In April 2004, the EPA announced that counties in 31 states and the District of Columbia failed to meet the new eight-hour standard for ozone. On November 8, 2005, the EPA finalized Phase 2 of the Ozone Rule, which establishes the final compliance requirements and timelines upon which state, local, and tribal government will base their state implementation plans for areas designated as non-attainment. For particulates, the changes include retaining the existing standard for particulate matter with an aerodynamic diameter less than or equal to 10 microns (“PM10”), and adding a new standard for fine particulate matter with an aerodynamic diameter less than or equal to 2.5 microns (“PM2.5”). State fine particulate non-attainment designations were finalized in December 2005, and counties in 21 states and the District of Columbia were classified as non-attainment areas. In December 2005, the EPA also proposed changes to the current national air quality monitoring requirements for all criteria pollutants including particulates and revisions to the national air quality standards for fine particulate pollution, proposing more stringent requirements for this pollutant. The EPA expects to finalize these standards by September 2006 and would make the final designations for attainment of PM2.5 standards by 2009 and PM10 standards by 2013. Designated states would have to meet the new standards by 2015 for PM2.5 and 2018 for PM10. Meeting the new PM2.5 standard may require reductions of nitrogen oxide and sulfur dioxide emissions. Future regulation and enforcement of these new ozone and PM2.5 standards will affect many power plants, especially coal-fired plants and all plants in “non-attainment” areas. |

| | • | | Ozone. Significant additional emissions control expenditures may be required at many coal-fired power plants to meet the current NAAQS for ozone. Nitrogen oxides, which are a by-product of coal combustion, can lead to the creation of ozone. Accordingly, emissions control requirements for new and expanded coal-fired power plants and industrial boilers may continue to become more demanding in the years ahead. |

| | • | | NOx SIP Call. The NOx SIP Call program was established by the EPA in October of 1998 to reduce the transport of ozone on prevailing winds from the Midwest and South to states in the Northeast, which said they could not meet federal air quality standards because of migrating pollution. Under Phase I of the program, the EPA is requiring 90,000 tons of nitrogen oxides reductions from power plants in 22 states east of the Mississippi River and the District of Columbia beginning in May 2004. Phase II of the program, which became effective in June 2004, requires a further reduction of about 100,000 tons of nitrogen oxides per year by May 2007. Installation of additional control measures, such as selective catalytic reduction devices, required under the final rules will make it more costly to operate coal-fired electricity generating plants, thereby making coal a less attractive fuel. |

21

| | • | | Clear Skies Initiative. The Clear Skies Act of 2005, a revised version of the Clear Skies Acts of 2002 and 2003, was introduced in early 2005. Similar to its predecessors, the Clear Skies Act of 2005 sought to further reduce emissions of sulfur dioxide, nitrogen oxides, and mercury via reduced emissions caps and a revised emission allowance trading system on a national level. The Clear Skies Act of 2005 is still pending in the Senate Committee on Environment and Public Works. It is currently not possible to predict what, if any, new regulatory requirements will ultimately evolve out of these initiatives during the current Congress or in the future. |