- RC Dashboard

- Financials

- Filings

-

Holdings

- Transcripts

- ETFs

- Insider

- Institutional

- Shorts

-

8-K Filing

Ready Capital (RC) 8-KRegulation FD Disclosure

Filed: 20 Mar 13, 12:00am

| SPECIALRESEARCHREPORT | |

| MARCH2013 |

| FIVEREASONS TO BEOPTIMISTIC ABOUT THEUS HOUSINGMARKET |

Four years since the end of the recession, key housing indicators such as residential construction, home sales, housing starts, and real disposable income remain at anemically weak levels compared to past serious recessions1 – consistent with deleveraging periods after banking crises. Yet each of these indicators has seen incremental but steady improvement over the last two years. More importantly, home prices have risen meaningfully (5.5% year-on-year according to Case Shiller, 8.3% according to CoreLogic) and steadily, rising more than any same-month period in 2010, 2011, or 2012 in each of the past nine months. Because homeowners are leveraged borrowers, home price appreciation is a key driver of mobility, housing activity, spending, and confidence. Historically, home prices display considerable momentum, but can correct sharply on occasions (such as 2006-08) when price trends reverse course.

ZAIS believes this is unlikely to happen anytime soon. The Fed’s reflation efforts appear to have borne fruit in markets as disparate as equities to commercial properties. Despite recent appreciation, residential home prices remain deeply depressed compared to 2006 highs (Figure 1a). From a long-term equilibrium perspective, home prices look roughly fair. Price-to-rent ratios of about 0.9 suggest homes are slightly undervalued. We prefer price-to-income ratios as an equilibrium measure because

| 1 | We look at the 1973-75, 1981-82, 1990-91, and 2001 recessions, controlling for the number of months since each recession’s end. |

|

| MARCH2013 | SPECIALRESEARCHREPORT|PAGE2 |

markets displayed a stable equilibrium for a quarter-century (1978-2003 in Figure 1b) before distorting in the 2000’s. By this measure, home prices are fair. Thus, we see no obvious disequilibrium pull to precipitate a reversal in home price appreciation.

Part of the reason home prices have not rebounded strongly is shadow inventory; the overhang of foreclosed or soon-to-be foreclosed properties. The greatest endogenous risk to a housing recovery, in our view, is an unexpected contraction in mortgage credit that disrupts the absorption of shadow inventory but this risk appears manageable. Distressed inventory fell from roughly 6 million homes in 2010 to about 4.5 million currently, and annual liquidations of approximately 1.5 million distressed homes in recent years have failed to dampen home prices2. Furthermore, policies that further extend foreclosure timelines are more likely in a downturn, providing a soft policy backstop to distressed sale volume (e.g. when we would expect new modification programs).

On the other hand, ZAIS sees numerous reasons to be optimistic about housing – over and above quantitative easing, structural rebalancing, and other factors that affect the economy more broadly. Our top five are pent-up demand, inflationary pressures, labor mobility, expansion of affordable financing, and renovated re-sales of distressed homes.

____________________ | ||

| 2 | Estimates from J P Morgan. |

|

| MARCH2013 | SPECIALRESEARCHREPORT|PAGE3 |

Reason #1: Pent-up demand should provide a front-loaded boost.

Uncertain financial prospects, declining home prices, and curtailed access to financing understandably cut housing demand in the aftermath of the housing bust. Far fewer homeowners moved from 2008-2012 than normal, as displayed in Figure 2a. The number of existing homes sold averaged about 4.3 million per year post-crisis, compared to 5.3 million from 1999-2003, summing to a gap of over 5 million homes. Many of these homeowners continued to have children or progressed in their careers, and would now presumably like to move to a larger house if possible (census surveys consistently peg trade-ups as the number one reason for moving). As housing prospects improve, this pent-up demand should lead to higher transaction volumes. While existing homes by definition are net neutral for supply/demand, environments with high transaction volumes have historically been associated with rising home prices.

Even more important than existing home sales is household formation, which drives net demand. Figure 2b shows five years of household formation at roughly half the usual 1.1 million annually, resulting in a gap of 2-3 million new households. New graduates living with their parents can delay marriage, children, and homeownership only so long, and a significant fraction of the gap is likely to boost household formation in the early years of a housing recovery (and even households that rent indirectly support home prices by removing alternative supply).

|

| MARCH2013 | SPECIALRESEARCHREPORT|PAGE4 |

Reason #2: Inflation may help home prices materially.

The reservoir of impatiently waiting home buyers is finite, and the effects of pent-up demand should dissipate after a few years. However, front-loaded upward pressure can help precipitate other positive factors. Furthermore, inflationary pressures may kick in by the time pent-up demand flags. This matters because, for sustained home price appreciation without price-to-income equilibrium distortions, incomes need to rise.

Figure 3a shows that home prices historically behave like real assets. Over the past 120 years, home prices have behaved stably for decades at a time, despite a number of highly inflationary periods (shaded areas denote CPI above 7%).

We have long argued that easy monetary policy, however necessary to combat deflation in the near term, will generate inflationary pressure as recovery gains strength3. Abnormally low money multipliers, Chinese exportation of inflation, and a likely increase in the natural rate of unemployment are all reasons to believe the Fed will have difficulty taming inflation in a timely fashion. High Debt-to-GDP is another major concern, as inflation has historically been a powerful aid in restoring fiscal balances of debtor nations.

| ____________________ | ||

| 3 | See “Avoiding the Government Bond Bubble” white paper on the ZAIS website https://www.zaisgroup.com/research.aspx |

|

| MARCH2013 | ZAIS LETTERTOINVESTORS| PAGE5 |

Home Price Appreciation (HPA) is likely to accelerate a similar amount. For mortgage-based securities, this is generally a positive because leveraged borrowers care about nominal price increases.

Of course, household incomes can also rise without inflation. Figure 3b shows that incomes trend upward over time, and based on this long-term trend we would expect increases of roughly 0.5% per year. At present, however, incomes are far below trends, and in a general economic recovery they would need to rise 10-15% to match long-term trends. We don’t count this in our list of reasons for optimism, because it hinges on a general recovery, not simply a rebound in housing. Nevertheless, we expect this effect to kick in at some point as housing couples into, and helps drive, a general recovery.

Reason #3: Improved mobility should help employment, leading to a virtuous cycle.

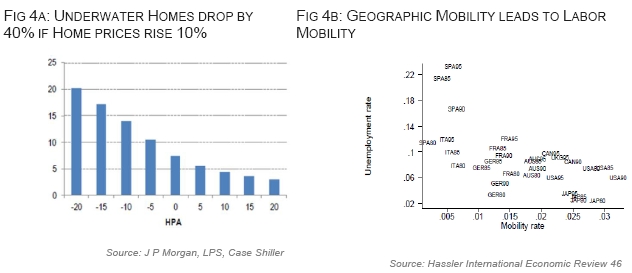

A specific mechanism for coupling a housing recovery to the general recovery that is sometimes overlooked is the impact of geographic mobility on labor mobility. As highlighted in Figure 4a, a 10% rise in home prices would reduce the number of underwater borrowers by roughly a third, allowing these borrowers to move without coming up with large up-front payments. Thus, an oil engineer in South-central California may suddenly be able to transfer to a dream job in Texas. It also increases the equity of above-water borrowers, allowing them to put down-payments on significantly larger homes – a major driver of high housing turnover in the mid-2000s.

Figure 4b shows empirical evidence that geographic mobility feeds into employment. Industrialized countries during periods of high geographic mobility (such as the US in the 1990s) tend to have low structural levels of unemployment, whereas as those with low mobility (particularly Spain and Italy) tend to have high unemployment. Census estimates of mobility indicate 2007-12 levels were approximately 35% below long-term (1947-2006) levels. Existing home sales and our own estimates of credit availability suggest even lower mobility. The unprecedented nature of the current housing/credit environment makes it difficult to quantify the effect of increased mobility on employment, but we estimate that improving homeowner equity and credit availability could improve the mobility rate by 1-1.5 percentage points. Using Figure 4b as a guideline, this could be associated with a reduction in unemployment rates of 3-5 percentage points. While not all of this is causal, a

|

| MARCH2013 | ZAIS LETTERTOINVESTORS| PAGE6 |

rise in home prices should nevertheless indirectly result in improved employment, which has the potential to increase home prices in a virtuous cycle.

Reason #4: Expansion of credit availability should have a multiplier effect on affordability.

Many analysts attribute low mortgage rates as the driving force behind the housing rebound. We view it as a minor contributor because the effect has been suppressed by weak credit availability. As shown in Figure 5a, mortgage affordability has been extremely high since 2008, yet home prices did not pick up until 2012. Low rates help borrowers who qualify for mortgages, but tight underwriting boxes limit the reach of low rates. Average FICO credit scores on GSE originations have risen from 720 pre-crisis to 760. Average FICO on FHA loans has risen even more, from 660 pre-crisis to nearly 710. Figure 5b suggests that, assuming high-FICO borrowers have the same access to credit today as in 2007, nearly half the borrowers that would normally qualify for a mortgage pre-crisis would fail to do so now4.

| ____________________ | ||

4 | This estimate, based on credit score at origination for 30-year fixed-rate GSE mortgages, is consistent with estimates from voluntary housing turnover and refinance efficiency, which respectively imply a post-crisis reduction in credit availability of 44%, 45%, and 47%. |

|

| MARCH2013 | ZAIS LETTERTOINVESTORS| PAGE7 |

If credit availability expands as housing strengthens, the multiplier effect of low rates should expand. The spread between mortgage rates and 10-year Treasuries is about 50 basis points wider than pre-crisis norms, and mortgage rates are likely to be stable as Treasuries sell off. Even if mortgage rates rise hand-in-hand, the multiplier effect should more than compensate. Historically speaking, mortgage rates of 5.5% (about 200 basis points above present) would still be near 40-year pre-crisis lows, and therefore highly stimulative. While credit availability is likely to expand gradually, a robust housing market should encourage origination by banks and non-bank financial intermediaries. Price appreciation also enables equity withdrawals by homeowners, expanding credit access by helping repair damaged credit histories.

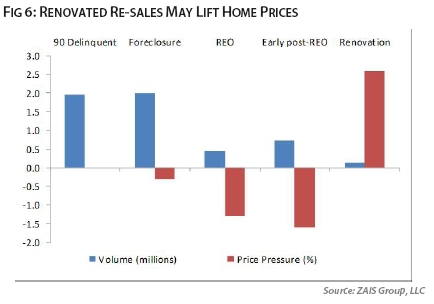

Reason #5: Distressed homes bought at fire sale discounts should be resold at sharply higher prices.

Our last optimistic bullet point is something we’ve discussed in prior letters (e.g., 2012 Q3 Strategy Letter): Renovated Re-Sales. Figure 6 shows schematically why shadow inventory has been pushing downward on home prices. As seriously delinquent loans (shadow inventory) get absorbed as distressed sales, they lower home price measures because distressed sales typically have 25-30% discounts to voluntary sales (contagion effects act in addition). As already discussed, we expect this downward pressure to continue for a few years, but not to sharply intensify. The 5 million or so distressed sales over the past 3-4 years have been absorbed by either investors or homeowners. Both groups are likely to inject capital into the

|

| MARCH2013 | ZAIS LETTERTOINVESTORS| PAGE8 |

homes, at a minimum repairing the property damage that typifies foreclosure sales. Both are likely to want to sell the property as home prices rise, either for profit (investors) or to trade up (pent-up demand for homeowners). Either way, we should see more and more renovated transactions that sell for 25-30% higher prices than the quick-sale purchase price, plus injected equity, plus any normal price appreciation. Such sales should boost home price measures significantly (rightmost red bar in Figure 6).

The timing of these effects is uncertain, and will likely to be staggered. We view pent-up demand as the most likely immediate catalyst, followed by expanding credit availability, geographic mobility, and renovated re-sales. Inflation may kick in later, although historical experience shows it is extremely difficult to predict its timing and magnitude. The successional order, in our view, is less important than the observation that there are numerous interacting effects that have the potential to amplify each other in a virtuous cycle. We do not count on these effects boosting HPA, but consider them essential to maximizing upside optionality in investments.

|

| MARCH2013 | ZAIS LETTERTOINVESTORS| PAGE9 |

IMPACT OFHOUSING ONMORTGAGES |

Direct effects of HPA can be quantitatively assessed using proprietary models that are calibrated to historical experience. Indirect effects are more subjective because many of the expected phenomenon have no modern precedent. Our base and downside scenarios are not particularly sensitive to speculations about the interaction of mobility and employment, or the impact of home price reflation on credit availability. The potential upside, on the other hand, depends a great deal on these outcomes.

To access the plausible upside if our “five reasons for optimism” reach fruition, Figure 7 shows model estimates of the direct effect of a housing boom scenario in which home prices rise 39% over the next three years (compared to more pessimistic three year increase of 4%). Not surprisingly, prime MBS has the least upside, while Alt-A and subprime stand to benefit more. Whole loans show even stronger sensitivities to home prices because we’ve focused on re-performing loans whose recoveries depend on home prices several years from now.

In the second half of the table, we make very rough estimates of indirect effects. Our models quantify the price effect for a given change in defaults, prepayments, or severities. We then estimate how increased mobility leads to improved employment and lower defaults; how expanded credit availability leads to higher housing turnover and refinancings; and how dwindling distressed sales shorten the foreclosure timeline and compress quick-sale discounts. Our estimates could be off by a factor of two or more, but nevertheless suggest indirect effects are at least as important as direct ones when considering potential upside.

|

| MARCH2013 | ZAIS LETTERTOINVESTORS| PAGE10 |

FIG7: A HOUSINGREBOUNDHELPSMORTGAGES

| ESTIMATEDPRICECHANGE FROMDIRECTEFFECT OF | ||||

| HOUSINGBOOM | ||||

| PRIME | ALT-A | SUBPRIME | WHOLE | |

| LOANS | ||||

| +39% HPA in 3 Years (compared to +4% over 3 years) | 3.4 | 9.3 | 10.3 | 12.4 |

| ESTIMATEDPRICECHANGE FROMINDIRECTEFFECTS OF | ||||

| HOUSINGBOOM | ||||

| Fewer Defaults (mobility) | 0.8 | 1.6 | 4.4 | 5.3 |

| Faster Prepayments (mobility and credit availability) | 3.6 | 5.3 | 0.1 | 2.8 |

| Better Recoveries (faster dispositions) | 2.1 | 4.5 | 4.6 | 3.9 |

| TOTAL INDIRECT | ||||

| PRICE CHANGE | 6.6 | 11.4 | 9.1 | 12.0 |

Source: ZAIS Group, LLC | ||||

Of course, different collateral and structures depend more or less sensitively than the benchmarks in the table. For example, many of our funds contain RMBS bonds with heavily modified concentrations that increase their sensitivity to forward home prices. ZAIS continues to select investments that it believes can handle extremely weak growth or a modest downturn, but provide significant optionality in a vigorous housing rebound.

As always, we are available to discuss, please contact your client relations representative at +1 732 978 9722 or ZAISclientrelations@zaisgroup.com.

|

| MARCH2013 | ZAIS LETTERTOINVESTORS| PAGE11 |

DISCLAIMER

The information contained herein has been obtained from sources believed to be reliable, but ZAIS Group, LLC and its affiliates (“ZAIS”) do not guarantee its accuracy or completeness. The opinions and estimates reflect our best judgment as of the report date and are subject to change without notice. ZAIS is under no duty to update this report. This report is intended for informational purposes only and does not constitute an offer or solicitation to buy or sell any securities. The opinions and recommendations herein do not take into account individual client circumstances, objectives, or needs and are not intended as recommendations of particular securities, financial instruments or strategies to particular clients. The recipient of this report must make its own independent decisions regarding any securities, financial instruments or strategies mentioned herein.

This material should not be regarded as providing any specific advice. ZAIS accepts no obligation to provide any advice or recommendations in respect of the information contained in this material and accepts no fiduciary duties to the recipient in relation to this information.

Investors should not utilize this report as the basis of any investment decision and the report should not be viewed as identifying or suggesting all risks, direct or indirect, that may be associated with any investment decision.

ZAIS produces a number of different types of research products. Recommendations contained in one type of research product may differ from recommendations contained in other types of research products, whether as a result of differing time horizons, methodologies or otherwise. It is possible that individual employees of ZAIS may have different perspectives to this publication and may pursue investment strategies that may or may not be consistent with the information contained in this publication.

This information is being delivered solely for informational purposes and is not an offer to buy or sell or a solicitation of an offer to buy or sell any security or instrument or to participate in any trading strategy. Information contained herein does not purport to be complete and is subject to the same qualifications and assumptions, and should be considered by investors only in the light of the same warnings, lack of assurances and representations and other precautionary matters, as disclosed in an offering document or prospectus.

ZAIS does not make any representation or warranty, expressed or implied, regarding any prospective investor’s legal, tax or accounting treatment of the matters described herein, and ZAIS is not responsible for providing legal, regulatory or accounting advice to any prospective investor.

These materials contain statements that are not purely historical in nature but are “forward-looking statements.” In some cases, you can identify forward-looking statements by terms such as “anticipate,” “believe,” “could,” “estimate,” “expect,” “intend,” “may,” “plan,” “potential,” “should” and “would” or the negative of these terms or other comparable terminology. These forward-looking statements include, among other things, projections, forecasts, estimates of income, yield or return, future performance targets, sample or pro forma portfolio structures or portfolio composition, scenario analysis, specific investment strategies and proposed or pro forma levels of diversification or sector investment. These forward-looking statements are based upon certain assumptions, some of which are described herein. Prospective investors are cautioned not to place undue reliance on such statements. No representation is made by ZAIS as to the accuracy, validity or relevance of any such forward-looking statement. Each recipient is hereby solely responsible for gathering its own information and undertaking its own projections, forecasts, estimates and hypothetical calculations. Actual events are difficult to predict, are beyond ZAIS’ control, and may substantially differ from those assumed. All forward-looking statements included herein are based on information available on the date hereof and ZAIS does not assume any duty to update any forward-looking statement. Some important factors which could cause actual results to differ materially from those in any forward-looking statements include, among others, the actual composition of the portfolio of eligible investments, any defaults to the eligible investments, the timing of any defaults and subsequent recoveries, changes in interest rates, and any weakening of the specific obligations included in any portfolio of eligible investments. Accordingly, there can be no assurance that estimated returns or projections can be realized, that forward-looking statements will materialize or that actual returns or results will not be materially lower than those presented.

Additional information is available upon request.

© 2013 ZAIS Group, LLC. All rights reserved.

|