insurance may not provide adequate coverage against potential liabilities. We do not maintain insurance for environmental liability or toxic tort claims that may be asserted against us in connection with our storage or disposal of biological, hazardous or radioactive materials.

In addition, we may incur substantial costs in order to comply with current or future environmental, health and safety laws and regulations. These current or future laws and regulations, which are becoming increasingly more stringent, may impair our research, development or production efforts. Our failure to comply with these laws and regulations also may result in substantial fines, penalties or other sanctions.

We are subject to certain U.S. and certain foreign anti-corruption, anti-money laundering, export control, sanctions and other trade laws and regulations. We can face serious consequences for violations.

U.S. and foreign anti-corruption, anti-money laundering, export control, sanctions and other trade laws and regulations prohibit, among other things, companies and their employees, agents, CROs, legal counsel, accountants, consultants, contractors and other partners from authorizing, promising, offering, providing, soliciting, or receiving directly or indirectly, corrupt or improper payments or anything else of value to or from recipients in the public or private sector. Violations of these laws can result in substantial criminal fines and civil penalties, imprisonment, the loss of trade privileges, debarment, tax reassessments, breach of contract and fraud litigation, reputational harm and other consequences. We have direct or indirect interactions with officials and employees of government agencies or government-affiliated hospitals, universities and other organizations. We also expect ournon-U.S. activities to increase over time. We expect to rely on third parties for research, preclinical studies and clinical trials and/or to obtain necessary permits, licenses, patent registrations and other marketing approvals. We can be held liable for the corrupt or other illegal activities of our personnel, agents, or partners, even if we do not explicitly authorize or have prior knowledge of such activities.

Any violations of the laws and regulations described above may result in substantial civil and criminal fines and penalties, imprisonment, the loss of export or import privileges, debarment, tax reassessments, breach of contract and fraud litigation, reputational harm and other consequences.

Risks Related to Our Intellectual Property

If we are unable to obtain and maintain sufficient patent protection for our drug candidates, or if the scope of the patent protection is not sufficiently broad, third parties, including our competitors, could develop and commercialize products similar or identical to ours, and our ability to commercialize our drug candidates successfully may be adversely affected.

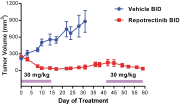

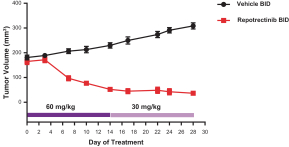

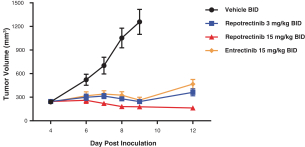

Our success depends in large part on our ability to protect our proprietary technologies that we believe are important to our business, including pursuing, obtaining and maintaining patent protection in the United States and other countries intended to cover the composition of matter of our drug candidates, for example, repotrectinib, the methods of use, related technologies and other inventions that are important to our business. In addition to patent protection, we also rely on trade secrets to protect aspects of our business that are not amenable to, or that we do not consider appropriate for, patent protection. If we do not adequately pursue, obtain, maintain, protect or enforce our intellectual property, third parties, including our competitors, may be able to erode or negate any competitive advantage we may have, which could harm our business and ability to achieve profitability.

To protect our proprietary position, we file patent applications in the United States and abroad related to our drug candidates that we consider important to our business. The patent application and approval process is expensive, time-consuming and complex. We may not be able to file, prosecute

80