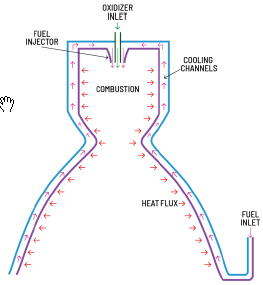

combustion chamber wall hotter. If the wall gets hot enough, the temperature of the wall can exceed the local boiling point of the fuel, causing some of the fuel to boil along the wall inside the channels. Sometimes this condition can “self-heal”, because a small amount of boiling can actually enhance the cooling ability of the fuel, bringing the wall temperature back down. However, if too much of the fuel boils, its cooling capability is significantly and adversely impacted, and the wall temperature can go up and up until the wall fails and “burns through,” dumping a portion of the fuel flow directly into the combustion chamber - essentially wasting it. This is what we determined had occurred during the TROPICS-1 launch.

In addition to the partial blockage of the injector, Astra determined that a secondary factor for the burn-through was thermal barrier coating erosion. Portions of the upper stage engine’s combustion chamber have a thermal barrier coating on the inside to insulate the chamber wall and reduce the heat that the fuel is required to absorb as a coolant. If some thermal barrier coating is missing, even a very small amount, that portion of the wall can get much hotter and increase the likelihood of a local burn-through. During the investigation, Astra found that there was a small amount of missing thermal barrier coating on the LV0010 upper stage engine. This missing coating was in a location that was considered acceptable by engineers at the time, but further analysis showed that we had underestimated the need for coating in this region under flight conditions (more on the ground vs. flight differences in the next section).

What caused the injector blockage?

While it was relatively straightforward to determine that a blockage of the injector had occurred during upper stage flight, it took much longer to conclusively determine what had caused the blockage. We used a combination of analysis and testing to systematically investigate each potential blockage source. Three credible sources for the blockage were the focus of this investigation:

| | • | | Foreign object debris (“FOD”), such as particles of metal |

After a review of flight results and testing to recreate the failure, we were able to conclude that the injector blockage was caused by a gas. This ruled out solid foreign object debris such as metal particles.

Next we examined helium, which is used for the upper stage’s pneumatic and pressurization systems, and theoretically could have leaked into the fuel lines. We performed a barrage of tests on our pneumatic systems, attempting to cause helium to leak under flight-like conditions of vacuum, vibration, and low temperatures. We were unable to substantiate any meaningful leaks, nor did data from the LV0010 upper stage indicate any leaks before or during flight. The only other credible source of helium in the upper stage is in the pressurization system, found at the start of upper stage flight in a small “ullage” bubble at the top of the fuel tank. Analysis showed it is highly unlikely that this helium could migrate to the bottom of the tank and be ingested into the engine at the beginning of the burn. Even if it had migrated, it’s even more unlikely that this helium could have remained in the bottom of the tank and sustained the injector blockage for the amount of time seen in flight (helium, since it’s much lighter than fuel, tends to migrate toward the top of the tank as soon as the engine lights and the stage begins accelerating).

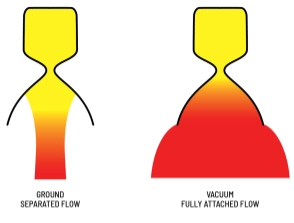

So, we were left with gaseous fuel as the main suspect. During ground acceptance testing, the fuel in the upper stage engine gets warm but we had never observed boiling or near-boiling within the cooling channels. However, the exhaust jet of the upper stage engine on the ground is “separated” from the inside of the engine nozzle by the pressure of the atmosphere around it, and therefore transfers less heat into the fuel. In flight, the engine is surrounded by vacuum and the exhaust jet expands to become “fully attached” to the inside of the nozzle. Therefore, the fuel passing through the engine during flight is heated to a higher temperature than during ground testing.