FEDERATIVE REPUBLIC OF BRAZIL

This description of the Federative Republic of Brazil is dated as of June 30, 2005 and appears as Exhibit D to the Federative Republic of Brazil’s Annual Report on Form 18-K to the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission for the fiscal year ended December 31, 2004.

Until the introduction of the real in July 1994, Brazil had experienced high rates of inflation. A variety of indices exist for measuring inflation in Brazil. This document uses the General Price Index-Domestic Supply (Índice Geral de Preços-Disponibilidade Interna, or “IGP-DI”), a national price index based on a weighting of three other indices, the Wholesale Price Index-Domestic Supply (Índice de Preços por Atacado-Disponibilidade Interna, or “IPA-DI”) (60%), the Consumer Price Index (Índice de Preços ao Consumidor, or “IPC”) (30%), and the National Index of Building Costs (Índice Nacional de Custos de Construção, or “INCC”) (10%). The IGP-DI, one of the most widely used inflation indices, is calculated by the Getúlio Vargas Foundation, an independent research organization. See “The Brazilian Economy—Prices”. As measured by the IGP-DI, the annual rate of inflation in Brazil was 9.8% in 2000, 10.4% in 2001, 26.4% in 2002, 7.7% in 2003, 12.1% in 2004. Such levels of inflation, together with the devaluation of the Brazilian currency in relation to the U.S. dollar, should be considered by the readers of all financial and statistical information contained herein.

The following table sets forth certain exchange rate information for the selling of U.S. dollars, expressed in nominal reais, for the periods indicated. The Federal Reserve Bank of New York does not report a noon buying rate for the real.

Table No. 1

Commercial Exchange Rates (Selling Side)

R$/$1.00

| | | | | | | |

Year

| | Average for Period(1)

| | End of Period

| | Percentage Change (End of Period)

| |

2000 | | 1.8295 | | 1.9554 | | 9.3 | |

2001 | | 2.3522 | | 2.3204 | | 18.7 | |

2002 | | 2.9309 | | 3.5333 | | 52.3 | |

2003 | | 3.0715 | | 2.8892 | | (18.2 | ) |

2004 | | 2.9257 | | 2.6544 | | (8.1 | ) |

| (1) | | Weighted average of the exchange rates on business days during the period. |

Source: Central Bank

In January 1999, the Central Bank abandoned its exchange band mechanism, which encouraged small exchange devaluations within a specified range and which had been in effect since March 1995, and permitted the value of the real to float freely against that of the dollar. On December 31, 2004, the real-U.S. dollar exchange rate (sell side) in the commercial exchange market, as published by the Central Bank, was R$2.6544 to $1.00. See “Balance of Payments and Foreign Trade—Foreign Exchange Rates and Exchange Controls”. In this report, references to “dollars”, “U.S. dollars”, “U.S.$” and “$” are to United States dollars, and references to “real”, “reais” and “R$” are to Brazilian reais.

The fiscal year of the federal Government of Brazil (the “Government”) ends December 31. The fiscal year ended December 31, 2004 is referred to herein as “2004”, and other years are referred to in a similar manner. Tables herein may not add due to rounding.

D-1

MAP OF BRAZIL

D-2

INTRODUCTION

Brazil is the fifth largest country in the world and occupies nearly half the land area of South America. Brazil shares a border with every country in South America except Chile and Ecuador. The capital of Brazil is Brasília, and the official language is Portuguese. On December 31, 2004, Brazil’s estimated population was 182.7 million.

Following two decades of military governments, in 1985 Brazil made a successful transition to civilian authority and democratic government. A new Brazilian Constitution (the “Constitution”) was adopted in 1988. In 1989, direct presidential elections were held for the first time in 29 years. After winning a runoff election with 61% of the vote on October 27, 2002, Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva assumed the presidency of Brazil on January 1, 2003. As President, Mr. da Silva has initiated a series of social programs, including a “Zero Hunger” campaign, which is intended to eradicate famine and address poverty in the country, a “Bolsa Família” program that provides assistance to impoverished families and a “First Job” program aimed at facilitating young persons’ entry into the labor market. He has also secured reforms of the tax, pension and judicial systems, instituted a framework for public-private partnerships, introduced a regulatory framework for investment in, among others, the electricity sector and secured amendments to the country’s bankruptcy law. Finally, the da Silva administration’s economic policy has been characterized by fiscal discipline, a floating exchange rate and inflation targeting. Among the da Silva administration’s first initiatives was an increase in the consolidated public sector primary surplus target from 3.75% of real gross domestic product (“GDP”) in 2002 to 4.25% of GDP in each of 2003, 2004 and 2005. On September 22, 2004, the Government announced that it had raised its primary surplus target for 2004 to 4.5% of GDP from 4.25% of GDP due to better than expected fiscal revenues. The Government has maintained its 2005 primary surplus target of 4.25% of GDP.

Mr. da Silva is a member of the Workers’ Party (Partido dos Trabalhadores, or PT). Following the October 2002 elections, Mr. da Silva’s party held 17.5% of the seats in the Chamber of Deputies and 12.3% of the seats in the Senate. Mr. da Silva was elected as part of a broad coalition consisting of the Liberal Party and five smaller parties, including the Brazilian Socialist Party (PSB) and the Brazilian Workers Party (PTB). In 2003 and 2004, the PT formed new alliances with the Brazilian Democratic Movement Party (PMDB) and the Brazilian Progressive Party (PP) and with other, small parties. As a result of these alliances, Mr. da Silva’s coalition grew to 73% of the members of the Chamber of Deputies and to 57% of the members of the Senate. However, on December 12, 2004, the Brazilian Democratic Movement Party (PMDB) voted to leave President da Silva’s coalition and to support its own candidate for Brazil’s 2006 presidential election. Certain pro-government members of the PMDB—including two members of President da Silva’s cabinet and 19 of the party’s 22 senators—have said that they would ignore the party’s decision to leave the coalition. The PMDB’s move followed a decision by the smaller Popular Socialist Party (PPS) on December 11, 2004 to leave President da Silva’s coalition.

The success of Mr. da Silva’s initiatives will be influenced by public opinion toward the reforms and the strength of any opposition to the reforms by affected interest groups. Whereas ordinary legislation requires only a simple majority of both houses of Congress, amendments to the Constitution require three-fifths of the votes of the respective members of each house of Congress in two separate rounds. See “The Federative Republic of Brazil—Form of Government and Political Parties”.

Mr. da Silva succeeded in enacting certain pension reforms during his first two years in office. These reforms, which Brazil’s Chamber of Deputies and Senate approved on December 19, 2003 as Constitutional Amendment No. 41, included: (i) an increase in the minimum retirement age for civil servants from 48 to 55 years for women and from 53 to 60 years for men; (ii) a reduction of 30% in pensions paid for widows and orphans of civil servants in excess of R$2,400 per month; (iii) a contribution to the social security system by retired civil servants of 11% of the amount by which the retired employee’s pension exceeds R$1,440 per month in the case of federal retirees and R$1,200 per month in the case of all other retired civil servants; (iv) a uniform contribution level for municipal, State and federal workers consisting of at least 11% of the amount of the

D-3

employee’s salary; and (v) the institution of a complementary regime for the new civil servants, which will require the passage of ordinary legislation. For the private sector pension system, the cap on social security pensions paid to private sector retirees was raised from R$1,561.56 to R$2,400 per month. See “The Brazilian Economy—Constitutional Reform” and “—Social Security”.

Mr. da Silva was also able to enact certain tax reforms during his first two years in office. On December 19, 2003, the Chamber of Deputies and the Senate approved an amended tax reform bill in the form of Constitutional Amendment No. 42. Constitutional Amendment No. 42 provides for, among other things: (i) the extension to 2007 of the provisional financial contribution transaction levy (“CPMF”) and the Delinking of Central Government Revenues (“DRU”), which permits the reallocation of 20% of certain tax revenues that the federal Government would otherwise be required to devote to specific program areas under the Constitution; (ii) the exempting of exports from the tax on the circulation of goods and services (“ICMS”) and the establishment of a fund to compensate States for lost ICMS revenue resulting from that exemption; (iii) the imposition of the contribution for the financing of social security (COFINS) only at the final stage of the production process, rather than at each stage of that process; (iv) a reduction of the tax on industrial products (IPI) on imports of capital goods; and (v) a requirement that the federal Government transfer to States and municipalities 25% of the revenues from the federal contribution on fuel (CIDE). The Chamber of Deputies is also to consider a proposed Constitutional amendment authorizing the Senate to introduce legislation to create a new national value-added tax to replace certain federal and State taxes, including ICMS and the IPI. If the Chamber of Deputies approves the proposed amendment, the Senate will be authorized to propose a further Constitutional amendment providing for the creation of the new value-added tax. This further amendment would have to be approved by an absolute three-fifths majority in two rounds of voting in each of the Chamber of Deputies and the Senate to become effective.

During his second year in office, Mr. da Silva was able to enact certain judicial reforms. In November 2004, Congress approved Constitutional Amendment No. 45 dated December 8, 2004, a set of reforms intended to improve the efficiency of the judicial system. Constitutional Amendment No. 45, among other things, amends Articles 102 and 105 of Brazil’s Constitution to provide that the Superior Court of Justice, and not the Federal Supreme Court, is to determine whether foreign judgments and foreign arbitral awards are enforceable in Brazil. The enforcement by a Brazilian court of a foreign arbitral award is subject to the recognition of such award by the Superior Court of Justice. The Superior Court of Justice will recognize such an award if all of the required formalities are observed and the award does not contravene Brazilian national sovereignty, public policy and “good morals”.

Other reforms introduced by Constitutional Amendment No. 45 include: (i) the right of all parties to a judicial process of reasonable duration and to the means necessary to attain it; (ii) the submission by Brazil to the jurisdiction of the International Criminal Court, the governing statute of which was ratified by Brazil in June 2002; (iii) a provision barring a retired or removed judge from practicing, for a period of three years, before the court in which he or she sat; (iv) a rule providing that decisions of the Federal Supreme Court on the merits of lawsuits challenging the constitutionality of certain acts (ações diretas de inconstitucionalidade and ações declaratórias de constitucionalidade) constitute binding precedents for the lower courts and the direct and indirect administration; (v) a rule providing that the Federal Supreme Court may issue summary legal principles (súmulas) that are binding on the lower courts and the direct and indirect administration; (vi) the establishment of a fifteen-member National Council of Justice (Conselho Nacional de Justiça) to oversee the administrative and fiscal management of the judiciary; and (vii) the establishment of a fourteen-member National Council of the Public Ministry (Conselho Nacional do Ministério Público) to oversee the administrative and fiscal management of the public prosecution service.

Changes have also been made to improve the investment climate. On December 30, 2004, President da Silva sanctioned Law No. 11,079, which provides for the formation of two types of “public-private partnerships” or “PPPs”: (i) contracts for concessions of public works or utility services under which private party concessionaires receive payments from a public sector entity in addition to tariffs charged to end-users and

D-4

(ii) contracts for rendering of services under which a public sector entity is the end-user. PPP contracts must be worth at least R$20 million and provide for a service period of between five and thirty-five years, including extensions of the term. All such contracts can only be awarded through a public bidding process. Because the concessionaires will only begin to receive payments when the services under the PPP contract are provided, the private parties will have to obtain private financing for the construction of the facility that is to provide the services under the contract. Law No. 11,079 permits payments from the public sector entity to be made directly to the contractor’s creditors, thereby reducing the creditors’ overall credit risk. The federal PPP program is to be overseen by a management committee appointed by the Ministry of Planning, Budget and Management, the Ministry of Finance and the Office of the Chief of Staff (Casa Civil da Presidência da República). The management committee is charged with selecting the projects for and regulating the federal PPP program. Law No. 11,079 further permits the federal Government to allocate up to R$6 billion to a PPP Guarantee Fund (Fundo Garantidor de Parcerias Público-Privadas, or FGP). On May 30, 2005, the Planning, Budget and Management Ministry announced that it had prepared a list of ten projects to be presented to the private sector as possible PPPs. The Government expects to announce the first six projects, which are all related to the transportation infrastructure, by November 30, 2005.

On February 9, 2005, President da Silva sanctioned a bankruptcy law that had been under consideration by the Congress for ten years, as well as changes to the tax code. The new bankruptcy law, Law No. 11,101, among other things, (i) places a cap equal to 150 times the minimum monthly salary on claims in bankruptcy proceedings by employees for such items as unpaid wages, unused vacation time and the 40% penalty for unjust dismissals; (ii) gives secured credits (such as those held by banks) priority over tax claims in bankruptcy proceedings; and (iii) ends a “succession” doctrine that makes a purchaser of assets from a bankrupt company or from a company under judicial reorganization responsible for certain of the insolvent company’s tax and social security obligations as a consequence of the acquisition, and, in the case of a company under bankruptcy proceedings, the debtor’s labor claims. The Government expects the measure to reduce interest rates charged by financial institutions for domestic loans.

In February 2005, Severino José Cavalcanti Ferreira, a Deputy in the Progressive Party (PP), defeated the Workers Party’s candidate in an election for president of the Chamber of Deputies. Although the PP is a member of President da Silva’s coalition, Mr. Cavalcanti has in the past criticized certain elements of the Government’s economic and social agenda. The leadership change in the Chamber of Deputies might, therefore, make it more difficult for the Government to obtain legislative approval of certain other proposed reforms.

On February 13, 2004, the Government fired Waldomiro Diniz, an aide to President da Silva’s former Cabinet Chief, José Dirceu, after a weekly news magazine posted a video on its website that allegedly showed Mr. Diniz in 2002, while Mr. Diniz was the head of the State of Rio de Janeiro’s lottery company, soliciting campaign contributions for two Workers Party candidates and offering political favors in return. The leaders of Brazil’s opposition parties called for a congressional investigation of the Diniz matter and demanded the resignation of Mr. Dirceu. On February 18, 2004, the Government announced that it would conduct an internal investigation of the Diniz matter and announced on March 23, 2004 that Mr. Dirceu had been cleared of any wrongdoing. The Government maintained that Mr. Diniz’s alleged misconduct occurred before President da Silva’s inauguration and was not connected to the current administration. On June 22, 2005, the Supreme Court ruled that the President of the Brazilian Senate was required to form a parliamentary commission of inquiry to investigate the country’s bingo industry.

In addition, in July 2004, a weekly news magazine in Brazil reported that Henrique Meirelles and Luiz Augusto Candiota, the Central Bank’s president and director of monetary policy, respectively, were being investigated by the public prosecutor’s office for tax evasion and other fiscal infractions and that their names had been mentioned at a congressional commission of inquiry (CPI) investigating capital flight through Banco do Estado do Paraná S.A. (Banestado), then the bank of the State of Paraná. According to the report, Mr. Meirelles had failed to file a tax return for 2001 on the grounds that he had been living abroad, although he had claimed that he was a resident of the State of Goiás during that period to run for Congress as a candidate of the Brazilian

D-5

Social Democratic Party (PSDB). Mr. Candiota, according to the report, had failed to report transfers of funds through MTB Bank in New York. Both individuals have denied any wrongdoing. Mr. Candiota resigned from his position, saying that he wished to avoid harm to the Central Bank. The public prosecutor’s office subsequently confirmed that it was conducting these investigations. Law No. 11,036 dated December 22, 2004, elevated the Governor of the Central Bank to ministerial status. As a result of such ministerial status, the Governor of the Central Bank can only be tried by the Federal Supreme Court.

On May 25, 2005, a joint session of the National Congress approved the formation of a parliamentary commission of inquiry (CPI) to examine charges of corruption in the postal service. The vote to form the CPI came after the release by a news magazine of a video recording of the former head of the postal service’s procurement and inventories management department appearing to accept a bribe and stating that he represented a government-allied political party, later identified as the Brazilian Workers Party (PTB). A weekly news magazine also reported that the president of the Brazilian Reinsurance Institute (IRB) had been recorded stating that the IRB was required to transfer R$400,000 per month to the PTB.

On June 6, 2005, a daily newspaper in São Paulo reported that Roberto Jefferson, the head of the PTB had alleged that the Workers Party had paid certain Congressmen $12,000 per month for their support in Congress. Mr. Jefferson further alleged the payments had continued, even after he had informed Cabinet Chief José Dirceu and Finance Minister Antônio Palocci. According to Mr. Jefferson, the payments stopped only after he had informed President da Silva of such payments. Mr. Jefferson stated that President da Silva had been previously unaware of such payments but alleged that certain senior officials of the Workers Party had overseen such payments. The Workers Party has denied the allegations. Testifying before the Congressional ethics committee on June 14, 2005, Mr. Jefferson admitted that he had no evidence to support any of his accusations. Mr. Jefferson and certain members of his party are the focus of the CPI investigation on corruption in the postal service and the Brazilian Reinsurance Institute. On June 14, 2005, the President of the National Congress received a formal request signed by 205 Deputies and 41 Senators for the installation of a parliamentary commission of inquiry (CPI) to examine the accusations made by Mr. Jefferson. On June 16, 2005, Mr. Dirceu resigned from his position as Cabinet Chief.

Prior to the introduction of the real as Brazil’s official currency in July 1994 pursuant to the Plano Real, Brazil’s economic performance had been characterized by macroeconomic instability, including extremely high rates of inflation and significant and sudden currency devaluations. Pre-Plano Real stabilization efforts, which included wage and price controls, failed to contain inflation for any extended period. See “The Brazilian Economy—Historical Background”. The Plano Real, which the Government announced in December 1993 and fully implemented in July 1994, succeeded in lowering inflation from an annual rate of 2,708.6% in 1993 and 909.6% in 1994 to 14.8% in 1995, 9.3% in 1996, 7.5% in 1997 and 1.7% in 1998, as measured by the IGP-DI. The inflation rate increased to 20.0% in 1999, however, following the decision of the Central Bank in January 1999 to permit the value of the real to float against that of the dollar. The inflation rate subsequently declined as a consequence of the implementation of the inflation targeting regime by the Central Bank in June 1999, registering 9.8% in 2000 and 10.4% in 2001. See “The Brazilian Economy—Prices”.

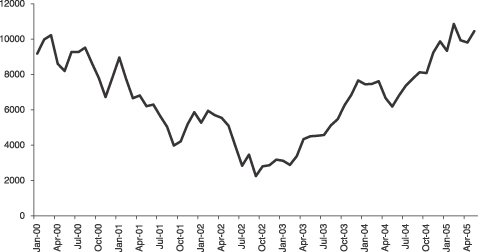

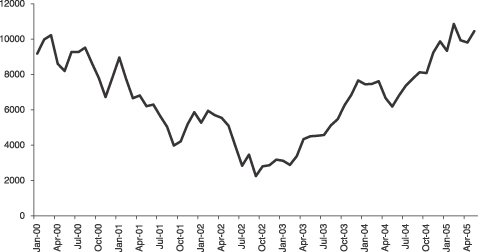

In addition, the value of the real has at times fluctuated significantly against the U.S. dollar. The second half of 2002 and the first quarter of 2003 posed several challenges for Brazil, for example, which arose in large part from the effects of Argentina’s financial crisis, a weak global economy, uncertainties about the country’s national elections held in October 2002 and concerns about terrorism and tensions in the Middle East. Through much of the period from July through October 2002, the real declined against the U.S. dollar. The real-U.S. dollar exchange rate (sell side), as published by the Central Bank, declined from R$2.8444 to $1.00 on June 28, 2002 to R$3.8949 to $1.00 on September 30, 2002 before reaching a low of R$3.9552 to $1.00 on October 22, 2002. Following the October 2002 elections, the real began to recover against the U.S. dollar, reaching R$3.5333 to $1.00 on December 31, 2002, R$2.8892 to $1.00 on December 31, 2003 and R$2.6544 on December 31, 2004. On May 31, 2005, the real-U.S. dollar exchange rate (sell side), as published by the Central Bank, was R$2.4038 to $1.00. See “Balance of Payments and Foreign Trade—Foreign Exchange Rates and Exchange Controls”.

Largely as a result of a depreciation in the value of the real, increases in administered prices (prices subject to Government regulation, such as rates for telephone calls and prices for gasoline and other petroleum derivatives, and prices governed by contracts with vendors, such as fares charged for certain public

D-6

transportation) and rising oil prices in the world markets, the inflation rate began to rise in Brazil during the fourth quarter of 2002. The inflation rate, as measured by IGP-DI, began to accelerate in October 2002, increasing 4.2% in October 2002 and 5.8% in November 2002. Although the inflation rate subsequently subsided, it reached 26.4% for 2002 and 7.7% in 2003 and 12.1% in 2004. For the 12 months ending May 31, 2005, the inflation rate, as measured by IGP-DI, was 8.4%. See “The Brazilian Economy—Prices” and “Balance of Payments and Foreign Trade—Foreign Exchange Rates and Exchange Controls”.

To address rising inflation during the last quarter of 2002, the Central Bank increased its overnight Over/Selic interest rate target from 18% to 21% on October 14, 2002, 22% on November 20, 2002, 25% on December 18, 2002, 25.5% on January 22, 2003 and 26.5% on February 19, 2003. The International Monetary Fund (“IMF”) also announced on September 6, 2002, in response to Brazil’s economic situation, that it had approved Brazil’s request for a 15-month standby facility of 22.8 billion in special drawing rights (SDR) (approximately $32.4 billion as of June 13, 2003) to support the country’s economic and financial program through December 2003. The standby facility was extended for another fifteen months in December 2003. In addition, in December 2003, the IMF extended by one year repurchases of SDR 4 billion (approximately $5.8 billion) that Brazil would otherwise have been required to make in each of 2005 and 2006. On March 22, 2005, the IMF announced that it had completed its tenth and final review of Brazil’s performance under the standby facility, and on March 28, 2005, the Brazilian government announced that it had decided not to request IMF support under a successor arrangement. The standby facility expired on March 31, 2005. See “The Brazilian Economy—Recent Economic Events and Policies” and “Public Debt—External Debt”.

Noting that the inflation rate as measured by the IPCA was likely to meet its target of 5.5% for 2004 and 4.5% for 2005 (with tolerance levels of plus or minus 2.5 percentage points), the Central Bank reduced its Over/Selic interest rate target from 26.5% on May 21, 2003 to 16% on April 14, 2004. However, in an effort to manage inflationary expections, the Central Bank increased its Over/Selic rate target from 16% to 16.25% on September 15, 2004, 16.75% on October 20, 2004, 17.25% on November 17, 2004, 17.75% on December 15, 2004, 18.25% on January 19, 2005, 18.75% on February 16, 2005, 19.25% on March 16, 2005, 19.5% on April 20, 2005 and 19.75% on May 18, 2005. These higher interest rates have increased the Republic’s financing costs as the Republic has been forced to issue debt at higher interest rates.

Brazil’s GDP rose 4.4% in 2000, 1.3% in 2001, 1.9% in 2002, 0.5% in 2003 and 4.9% in 2004. Growth in the agricultural sector, industrial sector and services sector rose in 2004 5.3%, 6.2% and 3.3%, respectively. Household consumption rose 4.1% in 2004 relative to 2003, and investments in manufacturing plants, machinery and capital equipment (formação bruta de capital fixo, or FBCF) rose by 10.9% in 2004 relative to 2003.

The current account recorded deficits from 1993 to 2002. Brazil’s current account deficit declined from $25.3 billion in 1999 to $24.2 billion and $23.2 billion in 2000 and 2001, respectively. The current account deficit fell to $7.6 billion in 2002 largely as a result of an improvement in the trade balance that year; Brazil registered a trade surplus of approximately $13.1 billion in 2002, versus a trade surplus of approximately $2.7 billion in the previous year. However, net foreign direct investment fell to $16.6 billion in 2002 from $22.5 billion in 2001, resulting in a balance of payments surplus of approximately $302 million in 2002, compared with a $3.3 billion balance of payments surplus in 2001. In 2003, Brazil registered a current account surplus of approximately $4.1 billion as the trade balance continued to improve. Net foreign direct investment continued to fall, totaling $10.1 billion in 2003. In 2004, the current account surplus reached a record high of $11.7 billion, driven in large part by a trade surplus of approximately $33.7 billion. The accumulated balance of payments surplus was approximately $2.2 billion, compared with an accumulated $8.5 billion balance of payments surplus in 2003. During the first five months of 2005, Brazil registered an accumulated trade surplus of approximately $15.6 billion, versus an accumulated trade surplus of approximately $11.2 billion for the corresponding period in 2004. The improvement in the trade balance during the first five months of 2005 resulted in an accumulated current account surplus of approximately $4.1 billion, compared to an accumulated surplus of approximately $2.3 billion for the corresponding period in 2004. See “Balance of Payments and Foreign Trade—Foreign Trade” and “—Balance of Payments.”

D-7

The Republic has generally financed most of its current account deficit each year through direct foreign investment. However, the Republic’s recurring current account deficits and the need to finance them have left the Republic vulnerable at times to external shocks and reductions in direct foreign investment. This volatility has declined, however, and in 2003 and 2004 Brazil registered a current account surplus for the first time since 1992, thereby reducing its external financing needs. See “The Brazilian Economy—Recent Economic Events and Policies”.

Since 1994, debt management policy has aimed at lengthening the maturity of domestic public debt, as well as consolidating a domestic yield curve by means of selling fixed income government securities. In December 2003, the average maturity of Brazil’s domestic debt securities was 31.3 months, down from 35.0 months in December 2001 and 33.2 months in December 2002. In December 2004, the average tenor of Brazil’s domestic debt securities was 28.1 months. A portion of the federal Government’s federal domestic securities debt is indexed to inflation indices or foreign currencies. On December 31, 2004, Brazil’s floating rate domestic securities debt totaled approximately R$625.5 billion (77.2% of all federal debt securities). A significant percentage of this debt was indexed to the U.S. dollar; the percentage of Brazil’s domestic debt securities that was indexed to the U.S. dollar was 22.3% in December 2000, 28.6% in December 2001, 22.4% in December 2002, 10.8% in December 2003 and 5.2% in December 2004. On April 30, 2005, Brazil’s U.S. dollar-indexed domestic securities debt totaled approximately R$34.5 billion (4.0% of all federal debt securities). By contrast, the aggregate principal amount of the federal debt securities indexed to the Over/Selic rate rose from R$449.0 billion (61.4% of all federal debt securities) on December 31, 2003 to R$463.0 billion (57.1% of all federal debt securities) on December 31, 2004 and R$517.0 billion (59.2% of all federal debt securities on April 30, 2005, while fixed rate federal debt securities increased from R$104.6 billion (14.3% of all federal debt securities) on December 31, 2003 to R$184.8 billion (22.8% of all federal debt securities) on December 31, 2004 and R$199.1 billion (22.8% of all federal debt securities) on April 30, 2005.

The large stock of floating rate domestic debt securities makes the Republic’s finances susceptible to significant interest rate movements, mostly because the debt is accounted for on an accrual basis. Persistent high debt servicing costs and the recognition of certain liabilities as obligations of Brazil have led to sustained high levels of net public sector debt as well as to nominal deficits. The consolidated public sector primary balance (which is the financial balance less net borrowing costs of the public sector) registered surpluses of 3.5% of GDP in 2000, 3.7% of GDP in 2001, 4.0% of GDP in 2002, 4.3% of GDP in 2003 and 4.6% of GDP in 2004.

The consolidated public sector nominal balance (the difference between the level of consolidated public sector debt in one period and the level of such debt in the previous period, excluding the effects of the Government’s privatization program and the effect of exchange rate fluctuations on the debt levels between periods), by contrast, showed deficits of 3.6% of GDP in 2000, 3.5% of GDP in 2001, 4.3% of GDP in 2002, 5.1% in 2003 and 2.7% in 2004. The interest expense in respect of Brazil’s public sector debt represented 8.6% of GDP in 2002, up from 7.2% of GDP in 2001. In 2003, the nominal deficit rose to 5.1% of GDP, as Brazil’s interest expense rose to 9.3% of GDP. In 2004, the interest expense was reduced to 7.3% of GDP and the nominal deficit represented 2.7% of GDP. The accumulated nominal balance for the five-month period ended May 31, 2005 declined to 1.9% of GDP, while interest expense rose to 8.5% of GDP.

Net public sector debt in Brazil, composed of the internal and external debt of the federal Government, State and local governments and public sector enterprises, amounted to $288.0 billion, or 48.7% of GDP, on December 31, 2000. Net public sector debt reached 54.8% of GDP in September 2001 as the real depreciated in value against the U.S. dollar, but ended the year at $284.7 billion on December 31, 2001, or 52.6% of GDP, as a result of the appreciation of the real during the fourth quarter of 2001. Brazil’s net public sector debt fell to $249.4 billion (or 55.5% of GDP) on December 31, 2002 but rose to $316.1 billion (or 58.7% of GDP) on December 31, 2003 as a result of higher Over/Selic rates. Brazil’s net public sector debt reached $360.6 billion (51.8% of GDP) in December 2004 and was at $398.4 billion (50.3% of GDP) in May 2005. See “Public Debt”.

During the period from 1982 until the implementation of Brazil’s external debt restructuring in 1994, Brazil failed to make payments on certain of its external indebtedness from commercial banks as originally scheduled, and in February 1987 declared a moratorium on principal and interest payments on external indebtedness to commercial banks. Brazil’s external indebtedness to commercial banks was restructured in a Brady Plan restructuring in April 1994. See “Public Debt—Debt Crisis and Restructuring”. Throughout the debt restructuring process, from 1982 to 1994, the Republic continued to make principal and interest payments on its external bonded indebtedness in accordance with the terms of such indebtedness. See “Public Debt—Debt Record”.

D-8

SELECTED BRAZILIAN ECONOMIC INDICATORS

| | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | |

| | | 2000

| | | 2001

| | | 2002

| | | 2003

| | | 2004

| |

The Economy | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | |

Gross Domestic Product (“GDP”): | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | |

(in billions of constant 2004 reais) | | R$ | 1,621.5 | | | R$ | 1,642.7 | | | R$ | 1,674.4 | | | R$ | 1,683.5 | | | R$ | 1,766.6 | |

(GDP at current prices in U.S.$ billions)(1) | | U.S.$ | 602.2 | | | U.S.$ | 509.8 | | | U.S.$ | 459.4 | | | U.S.$ | 506.8 | | | U.S.$ | 604.0 | |

Real GDP Growth (decline)(2) | | | 4.4 | % | | | 1.3 | % | | | 1.9 | % | | | 0.5 | % | | | 4.9 | % |

Population (millions) | | | 169.6 | | | | 175.1 | | | | 177.6 | | | | 180.2 | | | | 182.7 | |

GDP Per Capita(3) | | U.S.$ | 3,515.9 | | | U.S.$ | 2,932.9 | | | U.S.$ | 2,604.3 | | | U.S.$ | 2,831.4 | | | U.S.$ | 3,326.1 | |

Unemployment Rate(4) | | | 7.1 | % | | | 6.2 | % | | | 7.1 | % | | | 12.3 | % | | | 11.5 | % |

IGP-DI (rate of change)(5) | | | 9.8 | % | | | 10.4 | % | | | 26.4 | % | | | 7.7 | % | | | 12.1 | % |

Nominal Devaluation Rate(6) | | | 9.3 | % | | | 18.7 | % | | | 52.3 | % | | | (18.2) | | | | (8.1) | |

Domestic Real Interest Rate(7) | | | 7.0 | % | | | 6.3 | % | | | (5.7) | % | | | 14.6 | % | | | 3.7 | % |

Balance of Payments (in U.S.$ billions) | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | |

Exports | | | 55.1 | | | | 58.2 | | | | 60.4 | | | | 73.1 | | | | 96.5 | |

Imports | | | 55.8 | | | | 55.6 | | | | 47.2 | | | | 48.3 | | | | 62.8 | |

Current Account | | | (24.2) | | | | (23.2) | | | | (7.6) | | | | 4.2 | | | | 11.7 | |

Capital and Financial Account (net) | | | 19.3 | | | | 27.1 | | | | 8.0 | | | | 5.1 | | | | (7.3) | |

Change in Total Reserves | | | (2.3) | | | | 3.3 | | | | 0.3 | | | | 8.5 | | | | 2.2 | |

Total Official Reserves | | | 33.0 | | | | 35.9 | | | | 37.8 | | | | 49.3 | | | | 52.9 | |

Public Finance | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | |

Financial Surplus (Deficit) as % of GDP(8) | | | (3.6) | % | | | (3.5) | % | | | (4.3) | % | | | (5.1) | % | | | (2.7) | % |

Primary Surplus (Deficit) as % of GDP(9) | | | 3.5 | | | | 3.7 | | | | 4.0 | | | | 4.3 | | | | 4.6 | |

Public Debt (in billions) | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | |

Gross Internal Debt (Nominal)(10) | | U.S.$ | 322.7 | | | U.S.$ | 319.9 | | | U.S.$ | 256.0 | | | U.S.$ | 347.1 | | | U.S.$ | 418.8 | |

Gross External Debt (Nominal)(11) | | | 86.7 | | | | 82.9 | | | | 80.9 | | | | 84.8 | | | | 83.1 | |

Public Debt as % of Nominal GDP | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | |

Net Internal Debt | | | 39.1 | % | | | 42.2 | % | | | 41.2 | % | | | 46.7 | % | | | 44.3 | % |

Net External Debt(12) | | | 9.6 | | | | 10.4 | | | | 14.3 | | | | 12.0 | | | | 7.5 | |

Total Public Debt (Nominal)(13) | | U.S.$ | 409.4 | | | U.S.$ | 402.8 | | | U.S.$ | 336.9 | | | U.S.$ | 431.9 | | | U.S.$ | 501.9 | |

| (1) | | Converted into dollars based on the weighted average exchange rate for each year. |

| (2) | | Calculated based upon constant average 2004 reais. |

| (3) | | Not adjusted for purchasing power parity. |

| (4) | | Average annual unemployment rate of the metropolitan regions of Belo Horizonte, Porto Alegre, Recife, Rio de Janeiro, Salvador and São Paulo. The methodology used by IBGE to determine the average unemployment rate was changed in 2003. The average unemployment rates shown for 2000 through 2002 were determined using the methodology in effect prior to 2003. If the new methodology had been in effect in 2002, the average unemployment rate that year would have been 11.7%. See “The Brazilian Economy—Employment”. |

| (5) | | IGP-DI is one indicator of inflation. While many inflation indicators are used in Brazil, the IGP-DI, calculated by the Getúlio Vargas Foundation, an independent research organization, is one of the most widely utilized indices. |

| (6) | | Year-on-year percentage appreciation of the dollar against the real (sell side). |

| (7) | | Brazilian federal treasury securities deflated by the IGP-DI and adjusted at each month-end to denote real annual yield. |

| (8) | | Financial results represent the difference between the consolidated public sector debt in one period and the consolidated public sector debt in the previous period, excluding the effects of the Government’s privatization program and the effect of exchange rate fluctuations on the debt levels between periods. |

| (9) | | Primary results represent Government revenues less Government expenditures, excluding interest expenditures on public debt. |

D-9

| (10) | | Presents debt on a consolidated basis, which is calculated as the gross internal debt less credits between governmental entities. |

| (11) | | Not including external private debt. Consolidated external private debt as of December 31, 2004 was $60.1 billion. |

| (12) | | Gross external debt less total reserves. |

| (13) | | Consolidated gross public sector debt. |

Sources: Fundação Instituto Brasileiro de Geografia e Estatística (“IBGE”); Getúlio Vargas Foundation; Central Bank

D-10

THE FEDERATIVE REPUBLIC OF BRAZIL

Area and Population

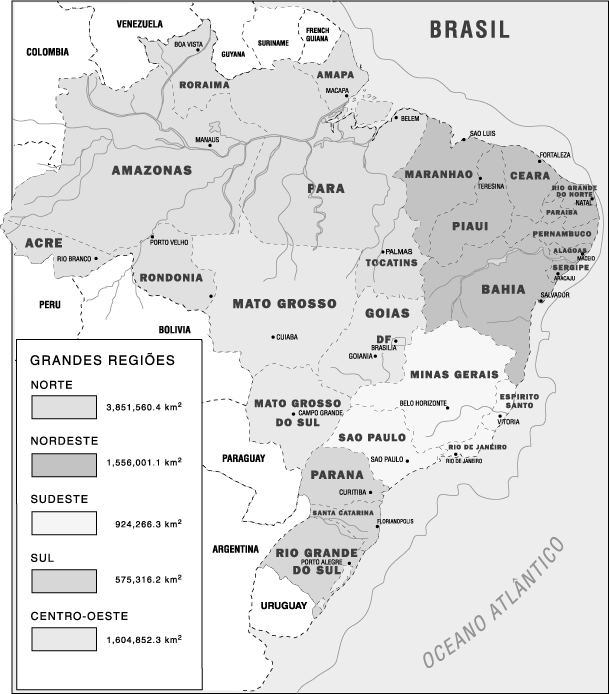

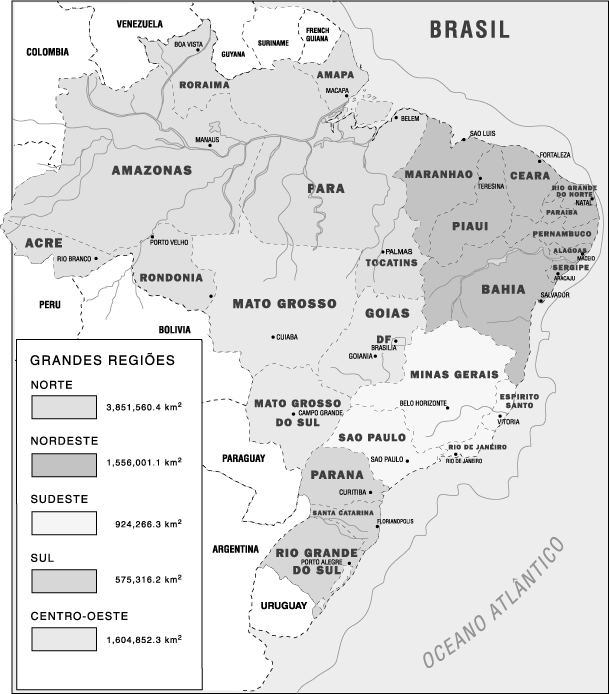

Brazil is the fifth largest country in the world and occupies nearly half the land area of South America. Brazil is officially divided into five regions consisting of 26 States and the Federal District, where the Republic’s capital, Brasília, is located.

Brazil has one of the most extensive river systems in the world. The dense equatorial forests and semi-arid plains of the North are drained by the Amazon River and the fertile grasslands of the South by the Paraná, Paraguay and Uruguay Rivers. Other river systems drain the central plains of Mato Grosso and the hills of Minas Gerais and Bahia. Most of the country lies between the Equator and the Tropic of Capricorn, and the climate varies from tropical to temperate. More than half of the total terrain of Brazil consists of rolling highlands varying from 650 to 3,000 feet in altitude.

According to the demographic census conducted by the Brazilian Institute of Geography and Statistics (“IBGE”) in 2000, Brazil had an estimated population of 169.8 million that year. IBGE also estimates that the population is currently growing at a rate of 1.6% per year. Approximately 138.0 million people, or 81.2% of the population, live in urban areas; the urban population has been increasing at a greater rate than the population as a whole. The largest cities in Brazil were São Paulo and Rio de Janeiro, with estimated populations of 10.4 million and 5.9 million, respectively, according to the 2000 census. Other cities with populations in excess of one million were Brasília, Belém, Belo Horizonte, Curitiba, Fortaleza, Goiânia, Manaus, Porto Alegre, Recife and Salvador. The States with the largest GDP in Brazil, São Paulo, Rio de Janeiro and Minas Gerais, had populations in excess of 37.0 million, 14.4 million and 17.9 million, respectively, on December 31, 2000.

There were approximately 136.9 million persons of working age (10 or more years of age) in Brazil in 2000. In 2001, the active labor force was composed of 75.5 million persons, of whom approximately 39.3% worked in retail and other services, approximately 20.6% in agriculture and related areas, approximately 13.5% in industry, approximately 6.5% in civil construction and approximately 18.4% in public administration.

Although social welfare indicators in Brazil such as per capita income, life expectancy, and infant mortality do not compare favorably to those of certain of Brazil’s neighboring countries, Statistics in the Human Development Report for 2004, published by the United Nations Development Program, show that Brazil has made significant progress in improving social welfare over the past three decades. During that period, life expectancy in Brazil increased by approximately 14.3% (from 59.5 years in 1970-1975 to 68 years in 2002) and the infant mortality rate decreased 68.4% (from 95 per 1,000 live births in 1970 to 30 per 1,000 live births in 2002). Adjusted for purchasing power parity by the United Nations, real GDP per capita rose 0.8% annually from 1975 to 2002. In addition, the reduction in inflation under the Plano Real and the consequent diminution of the erosion of purchasing power have improved the social welfare of large numbers of lower-income Brazilians.

D-11

The following table sets forth comparative GDP per capita figures and selected other comparative social indicators for 2002:

Table No. 2

Social Indicators, 2002

| | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | |

| | | Brazil

| | | Argentina

| | | Chile

| | | Ecuador

| | | Mexico

| | | Peru

| | | U.S.

| | | Venezuela

| |

Real GDP per capita(1) | | $ | 7,770 | | | $ | 10,880 | | | $ | 9,820 | | | $ | 3,580 | | | $ | 8,970 | | | $ | 5,010 | | | $ | 35,750 | | | $ | 5,380 | |

Life expectancy at birth (years) | | | 68.0 | | | | 74.1 | | | | 76.0 | | | | 70.7 | | | | 73.3 | | | | 69.7 | | | | 77.0 | | | | 73.6 | |

Infant mortality rate (per 1,000 births) | | | 30.0 | | | | 16.0 | | | | 10.0 | | | | 25.0 | | | | 24.0 | | | | 30.0 | | | | 7.0 | | | | 19.0 | |

Adult literacy rate | | | 86.4 | % | | | 97.0 | % | | | 95.7 | % | | | 91.0 | % | | | 90.5 | % | | | 85.0 | % | | | — | (2) | | | 93.1 | % |

| (1) | | Based on 2002 figures, adjusted for purchasing power parity by the United Nations. Per capita GDP amounts in this chart therefore differ from the amounts for per capita annual income set forth in “Summary Economic Information”. |

| (2) | | For purposes of calculating its “Human Development Index”, the United Nations Development Program applied a rate of 99.0%. |

Source: United Nations Development Program, Human Development Report 2004

Form of Government and Political Parties

Brazil was discovered by the Portuguese navigator Pedro Álvares Cabral in the year 1500 and remained a Portuguese colony for more than 300 years. The colonial government, first established in Salvador in the Northeast, was transferred to Rio de Janeiro in 1763. During the Napoleonic wars the Portuguese court moved from Lisbon to Rio de Janeiro, where it remained until 1821. In the following year Brazil declared its independence from Portugal, and the Prince Regent Dom Pedro I became Emperor of Brazil. His successor, Dom Pedro II, ruled Brazil for 49 years, until the proclamation of the Republic on November 15, 1889. From 1889 to 1930, the presidency of the Republic generally alternated between officeholders from the dominant States of Minas Gerais and São Paulo. This period, known as the First Republic, ended in 1930, when Getúlio Dorneles Vargas took power. Vargas governed Brazil for the next fifteen years, first as chief of a provisional government (1930-1934), then as a constitutional president elected by Congress (1934-1937) and finally as dictator (1937-1945) of a government that he termed the New State (Estado Novo). During the period from 1945 to 1961, Brazil held direct elections for the presidency. The resignation of President Jânio da Silva Quadros in 1961 after less than seven months in office and the resistance to the succession to the presidency of Vice President João Goulart created a political crisis that culminated in the establishment of a parliamentary system of government. The new system of government lasted approximately 16 months. In January 1963, after a plebiscite, Brazil returned to a presidential government, which was overthrown by the military in March 1964. Military governments ruled Brazil from 1964 until 1985, when a civilian president was elected by means of an electoral college composed of Senators and Deputies.

Thereafter, a series of political reforms was enacted, including the reestablishment of direct elections for the President and the calling of a Constitutional Assembly which, in October 1988, adopted a new Brazilian Constitution. In December 1989, Fernando Collor de Mello was elected President of Brazil for a five-year term in the first direct presidential election since 1960. Since October 1994, Brazil’s Presidents have been elected to serve four-year terms. In October 2002, Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva of the Workers’ Party (Partido dos Trabalhadores, or PT) was elected President of Brazil; he assumed the presidency on January 1, 2003.

Brazil is a federative republic with broad powers granted to the federal Government. The Constitution provides for three independent branches of government: an executive branch headed by the President; a legislative branch consisting of the bicameral National Congress, composed of the Chamber of Deputies and the

D-12

Senate; and a judicial branch consisting of the Federal Supreme Court and lower federal and State courts. The Constitution provided for a mandatory constitutional review that began in October 1993 and ended on May 31, 1994. The review resulted in the adoption of six amendments, which included the reduction of the presidential term of office from five to four years. The Constitution also provided for a plebiscite in April 1993 in which voters were permitted to consider alternative systems of government, including a return to the monarchy; in that plebiscite, the Brazilian electorate voted overwhelmingly to maintain the presidential system of government.

Under the Constitution, the President is elected by direct vote. A constitutional amendment adopted in June 1997 permits the re-election for a second term of the President and certain other elected officials. The President’s powers include the right to appoint ministers and key executives in selected administrative posts. The President may issue provisional measures (medidas provisórias) with the same scope and effect as legislation enacted by the National Congress. However, Constitutional Amendment No. 32, which became effective on September 12, 2001, prohibits the issuance of provisional measures for, among other things, the implementation of multi-year plans and budgets, the seizure of financial or other assets, and the regulation of matters which the Federal Constitution specifically requires the National Congress to regulate through complementary law. Under Constitutional Amendment No. 32, provisional measures are enforceable for up to 60 days, extendable for a single additional period of 60 days. If a provisional measure is rejected or if it is not voted by the National Congress within the enforcement period, the provisional measure becomes invalid as of the date it was issued. The amendment expressly prohibits the re-issuance of provisional measures not voted by the National Congress within the enforcement period.

The legislative branch of government consists of a bicameral National Congress composed of the Senate and the Chamber of Deputies. Ordinary legislation requires a simple majority vote in both houses of the National Congress for adoption. Amendments to the Constitution require an absolute three-fifths majority vote, in each of two rounds of voting, in both houses of the legislature. A matter addressed in a proposed amendment that is rejected cannot be reproposed during the same legislative session. The Senate is composed of 81 Senators, elected for staggered eight-year terms, and the Chamber of Deputies has 513 Deputies, elected for concurrent four-year terms. Each State and the Federal District is entitled to three Senators. The number of Deputies is based on a proportional representation system weighted in favor of the less populated States which, as the population increases in the larger States, assures the smaller States an important role in the National Congress.

D-13

The following table sets forth by the number and party affiliations of Senators and Deputies in the National Congress as of June 11, 2005.

Table No. 3

Distribution of National Congressional Seats by Party

| | | | |

| | | Senate

| | Chamber of Deputies

|

Partido dos Trabalhadores (PT) | | 13 | | 91 |

Partido da Frente Liberal (PFL) | | 16 | | 59 |

Partido do Movimento Democrático Brasileiro (PMDB) | | 22 | | 85 |

Partido da Social Democracia Brasileira (PSDB) | | 12 | | 49 |

Partido Trabalhista Brasileiro (PTB) | | 3 | | 47 |

Partido Progressista Brasileiro (PP) | | 1 | | 54 |

Partido Liberal (PL) | | 3 | | 54 |

Partido Socialista Brasileiro (PSB) | | 3 | | 17 |

Partido Popular Socialista (PPS) | | 1 | | 17 |

Partido Democrático Trabalhista (PDT) | | 4 | | 14 |

Others | | 3 | | 26 |

| | |

| |

|

Total | | 81 | | 513 |

Sources: Official Websites of the Offices of the Chamber of Deputies and of the Senate and Central Bank

The judicial power is exercised by the Federal Supreme Court (composed of 11 Justices), the Superior Court of Justice (composed of 33 Justices), the Federal Regional Courts (appeals courts), military courts, labor courts, electoral courts and the several lower federal courts. The Federal Supreme Court, whose members are appointed for life by the President, has ultimate appellate jurisdiction over decisions rendered by lower federal and State courts on Constitutional matters.

Brazil is divided administratively into 26 States and the Federal District. The States are designated as autonomous entities within the federative union and have all powers that the Constitution does not preclude the States from exercising. The Constitution reserves to the Republic the exclusive power to legislate in certain areas, including, among others, monetary systems, foreign affairs and trade, social security and national defense. The States may exercise legislative power in matters not reserved exclusively to the Republic and have, concurrently with the Republic, certain powers of taxation. At the State level, executive power is exercised by governors elected for four-year terms and legislative power by State deputies also elected for four-year terms. Judicial power at the State level is vested in the State courts, and appeals of State court judgments may be taken to the Superior Court of Justice and the Federal Supreme Court.

Federal, State and Local Elections

National general elections were held in October 2002. The offices of the President and State Governors, two-thirds of the Senate and all the seats in the Federal Chamber of Deputies, as well as seats in the State legislatures, were determined pursuant to the election. After winning a runoff election with 61% of the vote on October 27, 2002, Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva assumed the presidency of Brazil on January 1, 2003. Mr. da Silva is a member of the Workers’ Party (Partido dos Trabalhadores, or PT). Following the October 2002 elections, Mr. da Silva’s party held 17.5% of the seats in the Chamber of Deputies and 12.3% of the seats in the Senate. Mr. da Silva was elected as part of a broad coalition consisting of the Liberal Party and five smaller parties, including the Brazilian Socialist Party (PSB) and the Brazilian Workers Party (PTB).

Brazil last held local elections on October 3, 2004. Brazil’s next general elections are slated to be held in October 2006.

D-14

External Affairs and Membership in International Organizations

Brazil maintains diplomatic and trade relations with almost every nation in the world. It has been a member of the United Nations since 1945. The Republic participates in the organizations under the control of the United Nations Secretariat, as well as others of a voluntary character, such as the International Fund for Agriculture and Development.

Brazil is an original member of the International Monetary Fund and the World Bank, as well as three affiliates of the World Bank, the International Finance Corporation, the International Development Association and the Multilateral Investment Guaranty Agency. Brazil was an original member of the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (“GATT”) and is a charter member of the World Trade Organization. In addition, Brazil is an original member of the Inter-American Development Bank (“IDB”), the Inter-American Investment Corporation, the African Development Bank Group and the International Fund for Agricultural Development.

At the regional level, Brazil participates in the Organization of American States (the “OAS”) and in several sub-regional organizations under the OAS, as well as in the Latin American Economic System, the Latin American Integration Association, the Andean Development Corporation and the Financial Fund for the Development of the River Plate Basin.

In March 1991, Brazil, Argentina, Paraguay and Uruguay entered into the Treaty of Asunción, formally establishing the Mercado Comum do Sul (“Mercosul”), a common market organization composed of the signatory nations. In December 1994, the four member countries signed an agreement establishing the date of January 1, 1995 for the implementation of a Common External Tariff (“CET”) intended to transform the region into a customs union. However, under Decision No. 31 dated December 15, 2003 of the Common Market Council (Conselho do Mercado Comun, or CMC), each member country (other than Paraguay and Uruguay) is permitted a list of 100 items as exceptions to the CET through December 31, 2005, while Paraguay and Uruguay are permitted a list of up to 150 items and 125 items, respectively, until 2010. Because of these exceptions to the CET, the full implementation of a customs union has not yet been achieved.

Mercosul has six associate members: Bolivia, Chile, Colombia, Ecuador, Peru and Venezuela. Associate members are included in free trade treaties but have no voting rights within Merscosul.

Mercosul has attempted to form trading relations with other countries. Brazilian Presidential Decree No. 4,458 dated November 5, 2002 ratified an automobile accord between Mercosul and Mexico that is intended to increase trade in automotive products between the two parties. In December 2004, Mercosul also concluded preferential trade accords with India and the Southern African Customs Union (SACU).

At the first Summit of the Americas in Miami, Florida, in December 1994, Brazil joined 33 other countries in the Western Hemisphere in negotiations for the establishment of a Free Trade Area of the Americas (“FTAA”). In December 1995, Mercosul and the European Union signed a framework agreement for the development of free trade between them. In 1996, Mercosul signed agreements with Chile and Bolivia, effective October 1996 and February 1997, respectively, for the development of free trade among them; these agreements were approved by the Brazilian National Congress in September 1996 and April 1997, respectively. Mercosul also signed an agreement with Chile, approved by Brazilian Presidential Decree No. 4,404 dated October 3, 2002, that provides for the reduction of tariffs for certain automotive, chemical and agricultural products in trade between Brazil and Chile.

On October 29, 1999, Brazil and Argentina signed a protocol under the Treaty of Asunción to give effect to a memorandum of understanding between institutions in the two countries responsible for the certification of products that harmonizes the two countries’ standards for certification of certain products. The agreement covers a variety of products, including shoes, home appliances and toys.

D-15

THE BRAZILIAN ECONOMY

Historical Background

From the late 1960s through 1982, Brazil followed an import-substitution, high-growth development strategy financed, in large part, by heavy recourse to foreign borrowings. Foreign debt grew at an accelerated pace in response to the oil shocks of the 1970s and, when international interest rates rose sharply in 1979-80, the resulting accumulated external debt became one of Brazil’s most pressing problems in the decade that followed. See “Public Debt—Debt Crisis and Restructuring”. The debt crisis of the 1980s and high inflation substantially depressed real growth of Brazil’s GDP, which averaged 2.3% per year from 1981 to 1989. The public sector’s role in the economy also expanded markedly, with many key economic sectors subject to Government monopoly or subsidized participation, and significant structural distortions were introduced through high tariffs and the creation of subsidies and tax credit incentives. Significant increases in the money supply to finance a large and growing fiscal deficit further fueled inflationary pressures.

Efforts to address these problems during the late 1980s and early 1990s were largely unsuccessful. High inflation and the recurrent threat of hyperinflation during this period prompted the Government to pursue a series of stabilization plans, but these plans were undermined by a variety of factors. Stabilization measures implemented at that time relied on mechanisms, such as price and wage freezes and/or unilateral modifications of the terms of financial contracts, that were not supported by fiscal and monetary reforms. A central problem during this period was the public sector, which ran operational deficits averaging more than 5% of GDP during the five-year period from 1985 to 1989, while monetary policy was compromised by the short-term refinancing of public sector debt. These problems were aggravated by the 1988 Constitution, which limited the ability of the federal Government to dismiss public sector employees and reallocated public resources, in particular tax revenues, from the federal Government to the States and municipalities without a proportional shift of responsibilities to them, thereby further constraining the effectiveness of federal Government fiscal policy. The practice of inflation indexation in the economy, which made prices downwardly rigid, also helped to undermine stabilization measures. See “—Relationship between the Federal and Local Governments”, “—Employment” and “Public Finance—Taxation and Revenue Sharing Systems”.

In December 1993, the Government announced a stabilization program, known as the Plano Real, aimed at curtailing inflation and building a foundation for sustained economic growth. The Plano Real was designed to address persistent deficits in the Government’s accounts, expansive credit policies and widespread, backward-looking indexation.

The Plano Real had three stages. The first stage included a fiscal adjustment proposal for 1994, consisting of a combination of spending cuts and an increase in tax rates and collections intended to eliminate a budget deficit originally projected at $22.0 billion. Elements of the proposal included (i) cuts in current expenditures and investment through the transfer of some activities from the federal Government to the States and municipalities, (ii) the establishment of an Emergency Social Fund (“ESF”), financed by reductions in constitutionally mandated transfers of federal Government revenues to the States and municipalities, to ensure financing of social welfare spending by the federal Government, (iii) a prohibition on sales of public bonds by the Government, except to refinance existing debt and for certain specified expenditures and investments, (iv) new taxes, including a new levy on financial transactions, and (v) the collection of mandatory Social Security contributions (“COFINS”) in order to finance health care and welfare programs, following the November 1993 confirmation by the Federal Supreme Court that such contributions were permissible under the Constitution.

The second stage of the Plano Real, initiated on March 1, 1994, began the process of reform of the Brazilian monetary system. Brazil’s long history of high inflation had led to the continuous and systematic deterioration of the domestic currency, which no longer served as a store of value and had lost its utility as a unit of account. Because inflation had reduced dramatically the information content of prices quoted in local currency, economic agents had included in their contracts a number of mechanisms for indexation (providing for the adjustment of the amounts payable thereunder by an agreed-upon inflation or tax rate to preserve the economic value of such

D-16

contracts) and the denomination of obligations in indexed units of account. The process of rehabilitation of the national currency began with the creation and dissemination of the Unidade Real de Valor (the Unit of Real Value, or “URV”) as a unit of account. The second stage of the Plano Real was designed to eliminate the indexation of prices to prior inflation and to link indexation to the URV instead.

The third stage of the Plano Real began on July 1, 1994, with the introduction of the real as Brazil’s currency. All contracts denominated in URVs were automatically converted into reais at a conversion rate of one to one, and the URV, together with the cruzeiro real, ceased to exist (although the cruzeiro real was generally accepted until August 31, 1994). The real initially appreciated against the U.S. dollar, with the rate in the commercial market (sell side) moving from R$1.00/dollar, when the real was introduced, to R$0.829/dollar on October 14, 1994. In March 1995, the Central Bank formalized an exchange band system pursuant to which the real would be permitted to float against the U.S. dollar within bands established by the Central Bank. Thereafter, the real gradually declined in value against the dollar, reaching R$1.1164 per dollar on December 31, 1997 and declining further to R$1.2087 per dollar on December 31, 1998. As described more fully below, however, the Central Bank was forced in January 1999 to abandon its exchange band mechanism, which encouraged small exchange devaluations within a specified range, and permit the value of the real to float freely against that of the U.S. dollar.

Largely as a result of the measures under the Plano Real, the average monthly rate of inflation dropped significantly from 43.2% during the first half of 1994 to 2.65% during the second half of that year. The annual rate of inflation for 1994 was 909.6%, down from 2,708.6% in 1993. The public sector operational balance also showed a surplus of 1.3% of GDP in 1994, versus a 0.2% of GDP public sector operational surplus in 1993. However, the external accounts showed a higher current account deficit in 1994 as a result of an increase in imports and a reduction in net capital account surplus.

In January 1999, Brazil’s international reserves came under significant pressure as a result of a series of events that month. On January 6, 1999, the newly inaugurated governor of the State of Minas Gerais announced that the State would suspend for 90 days payments in respect of the State’s approximately R$18.3 billion debt to the Government. A week later, on January 13, 1999, Gustavo H.B. Franco, the president of the Central Bank and one of the architects of the Plano Real, resigned and was replaced by Francisco Lopes, who attempted a controlled devaluation of the real by widening the band within which the real was permitted to trade. Subsequent Central Bank intervention failed to keep the real-U.S. dollar exchange rate within the new band, however, and on January 15, 1999, the Central Bank announced that the real would be permitted to float, with Central Bank intervention to be made only in times of extreme volatility.

On February 2, 1999, the Government designated Armínio Fraga Neto to replace Francisco Lopes as president of the Central Bank. Following Mr. Fraga’s confirmation on March 3, 1999, the Central Bank eliminated two widely used overnight rates, the Central Bank Basic Rate (“TBC”) and the Central Bank Assistance Rate (“TBAN”), giving primacy to the Over/Selic rate; because the Central Bank could influence the Over/Selic rate on a daily basis through its participation in auctions, repurchase transactions and reverse repurchase transactions, the Over/Selic rate permitted the Central Bank to react more quickly to changes in market conditions.

Following its decision to permit the real to float, the Government formally adopted inflation targeting as its monetary policy framework. See “The Financial System—Monetary Policy and Money Supply”. The Government also began negotiations with the IMF on adjustments to the 1999-2001 economic program agreed in November 1998 and new economic targets in light of the new foreign exchange regime introduced in January 1999. On March 5, 1999, Brazil and the IMF announced that they had reached agreement on the adjustments. Under the agreement, Brazil undertook to adopt measures designed to achieve primary surpluses, excluding debt payments, of at least 3.1% of GDP in 1999, 3.25% of GDP in 2000 and 3.35% of GDP in 2001, substantially greater than the 2.6%, 2.8% and 3.0% of GDP surpluses for 1999, 2000, and 2001, respectively, under the November 13, 1998 agreement with the IMF.

D-17

Recent Economic Events and Policies

During the second half of 2000, uncertainties about the U.S economy, concerns about Argentina and rising oil prices caused the real to decline in value against the U.S. dollar. The real-U.S. dollar exchange rate (sell side) in the commercial exchange market, as published by the Central Bank, declined 7.5% from R$1.8234 to $1.00 on August 31, 2000 to R$1.9596 to $1.00 on November 30, 2000. Brazil’s continued compliance with a $41.8 billion IMF-led support program agreed on November 13, 1998, as established by the IMF’s sixth review on November 28, 2000, and an improvement in the external environment resulting from interest rate reductions in the United States, reduced the downward pressure on the exchange rate, which ended the year at R$1.9554 to $1.00. The improved conditions also permitted the Central Bank to lower its Over/Selic rate target to 15.75% on December 20, 2000 and 15.25% on January 17, 2001.

During the first five months of 2001, however, renewed concerns about Argentina, together with nervousness about the political impact of the alleged misconduct of certain public officials, put further downward pressure on the real. The real fell from R$1.9711 to $1.00 on January 31, 2001, to R$2.1847 to $1.00 on April 30, 2001. In May 2001, the Government announced its intention to reduce energy consumption through rationing and other measures in response to a severe power shortage. In addition, Argentina announced its intention to link its currency to both the U.S. dollar and the euro and, on June 15, 2001, announced the introduction of a special exchange rate for exporters in that country that permitted such exporters to exchange U.S. dollars for pesos for the combined average value of a U.S. dollar and a euro. Concerns about the impact of the Government’s energy measures and a possible Argentine devaluation of the peso drove the real to new lows against the U.S. dollar. The real-U.S. dollar exchange rate (sell side) in the commercial exchange market, as published by the Central Bank of Brazil, reached R$2.5517 to $1.00 on August 31, 2001.

Citing an increase in core inflation, the uncertainties related to the effects of exchange rate depreciation and the accelerating pace of economic activity, the Central Bank raised the Over/Selic rate target to 15.75% on March 21, 2001, 16.25% on April 18, 2001 and 16.75% on May 24, 2001. After the real dropped to R$2.4748 to $1.00 on June 20, 2001, the Central Bank raised its Over/Selic rate target by 1.50% to 18.25%. The Central Bank also announced on June 21, 2001 that it had intervened in the foreign exchange market by selling U.S. dollars and buying reais and that the Government would raise $10.8 billion in additional funds to increase its international reserves and to finance future interventions to support the real. Brazil planned to raise the funds by purchasing $2 billion under its IMF facility, postponing a $1.8 billion repayment under that facility, borrowing $1.8 billion from international financial institutions, issuing an additional $1 billion in new bonds in the international capital markets and selling shares of privatized companies for $3.8 billion. The $10.8 billion amount also included $400 million in proceeds of a bond issuance by Brazil’s National Bank for Economic and Social Development, or BNDES, completed earlier in the year. Approximately $6.2 billion of the funds were to be used to increase the level of Brazil’s foreign reserves, while the remaining $4.6 billion were to be available for use for further interventions in the foreign exchange markets.

After recovering briefly to R$2.2923 to $1.00 on June 28, 2001, the real declined to a low of R$2.5979 to $1.00 on July 16, 2001. The real recovered slightly to R$2.4247 to $1.00 on July 24, 2001 following the Central Bank’s decision on July 18, 2001 to raise its Over/Selic rate target to 19.00% from 18.25%. The Government also announced during the week of July 23, 2001 that it intended to negotiate an extension of its facility with the IMF and that it would seek to reduce 2001 spending by R$1 billion.

On September 14, 2001, the IMF announced that its Executive Board had approved a new standby facility for Brazil in the amount of SDR 12.14 billion (approximately $15.6 billion) in support of the Government’s economic and financial program through December 2002. Approximately $4.7 billion was available immediately, and Brazil made purchases totaling approximately $4.7 billion at the time the facility was established. The remainder was to be made available in five installments, subject to the satisfaction of certain performance criteria set forth in the Memorandum of Economic Policies accompanying Brazil’s letter of intent dated August 23, 2001. These performance criteria included targets for the primary surplus of 3.35% of GDP for 2001 and 3.5% of GDP for 2002 (an increase from the 3.0% target for both years under Brazil’s December 1998 IMF facility) and a net

D-18

international reserves floor of $20 billion (a $5 billion reduction from the floor under Brazil’s December 1998 IMF facility). The standby facility replaced the previous three-year standby arrangement approved in December 1998.

Following terrorist attacks on the World Trade Center and the Pentagon in the United States on September 11, 2001, the real-U.S. dollar rate moved to a new low, reaching R$2.8007 to $1.00 on September 21, 2001. The real began to recover after October 11, 2001, reaching R$2.5287 to $1.00 on November 30, 2001 and R$2.3204 to $1.00 on December 31, 2001. After giving effect to purchases under the IMF standby facility and a repurchase by the Republic of Poland for $2.5 billion of certain Paris Club credits owing to Brazil on November 13, 2001, Brazil’s international reserves stood at $35.9 billion on December 31, 2001.

The Republic of Argentina’s announcement in December 2001 and January 2002 that it would suspend payments in respect of certain of its public external debt and modify its exchange rate system, together with lower than expected trade flows, caused the real to fall approximately 4.2% during January 2002 to close at R$2.4183 to $1.00 on January 31, 2002. The real subsequently recovered, however, as a result of improving economic conditions in Brazil resulting from the end of energy rationing on March 1, 2002 and two reductions in the Central Bank’s Over/Selic rate target to 18.75% on February 20, 2002 and 18.50% on March 20, 2002. The real was also helped by the IMF’s announcements on January 23, 2002 and March 26, 2002 that it had completed reviews of Brazil’s performance under the IMF standby facility and that, based on those reviews, Brazil would be permitted to draw, if necessary, installments of SDR 358.6 million (approximately $448 million) and SDR 3.7 billion (approximately $5 billion). The real rose against the U.S. dollar, reaching R$2.3625 to $1.00 on April 30, 2002.

The real began to depreciate again in May 2002 amid renewed concerns about the potential contagion effect of Argentina’s problems and uncertainty about the October 2002 elections in Brazil. The value of the real declined to R$2.5220 to $1.00 on May 31, 2002 and R$2.7486 to $1.00 on June 12, 2002 before recovering to R$2.6700 to $1.00 on June 18, 2002. On June 13, 2002, the Government announced a new set of economic measures that included, among other things, (i) an increase in the 2002 target for the primary surplus to 3.75% of GDP from 3.5% of GDP, (ii) a purchase of an additional $10 billion under the IMF standby facility, (iii) a reduction of the minimum net international reserve requirement under that facility to $15 billion from $20 billion, (iv) repurchases from time to time of up to $3 billion aggregate principal amount of Brazil’s outstanding external debt securities, with an emphasis on those maturing in 2003 and 2004, (v) periodic interventions by the Central Bank in the foreign exchange market, (vi) rollovers of long-term Brazilian Treasury floating rate and U.S. dollar-indexed securities with shorter term securities and (vii) repurchases from time to time by the Brazilian Treasury of its domestic debt securities. In addition, the World Bank announced that day that it had approved three loans totaling $1.0 billion. The loans included a $400 million loan intended to provide continued support to the comprehensive financial sector reform being pursued by the Government, a $450 million loan to support reforms in the energy sector and a $160 million loan to finance the School Improvement Program Fund.

The IMF also announced on June 18, 2002 that it had completed its third review under the standby arrangement approved on September 14, 2001. In its press release, the IMF stated that Brazil’s performance under the facility remained strong. The IMF added “over the medium term, the authorities needed to continue to work to reduce Brazil’s large external borrowing requirement and the borrowing requirements of the public sector, as well as to reduce the large share of the public debt that is contracted at floating rates or linked to the exchange rate. Further progress in these areas, as well as on remaining elements of the structural reform agenda, will contribute to a further strengthening in Brazil’s position in the years ahead”. Based on the third review, the IMF made an additional SDR 3.7 billion (or approximately $4.8 billion) available for purchase under the standby facility, bringing the total amount available to be drawn to SDR 7.7 billion (or approximately $10 billion). Brazil withdrew the entire amount available on June 21, 2002.

From July through October 2002, the real continued to decline against the U.S. dollar. In addition to Argentina’s financial crisis and uncertainty about the October general elections, the decline was also attributable

D-19

to concerns about terrorism and tensions in the Middle East. The real-U.S. dollar exchange rate (sell side), as published by the Central Bank, declined from R$2.8444 to $1.00 on June 28, 2002 to R$3.4285 to $1.00 on July 31, 2002 and to R$3.8949 to $1.00 on September 30, 2002 before reaching a low of R$3.9552 to $1.00 on October 22, 2002. Following the October 2002 elections, the real began to recover against the U.S. dollar, reaching R$3.5333 to $1.00 on December 31, 2002 and R$2.8892 to $1.00 on December 31, 2003.

Largely as a result of a depreciation in the value of the real, increases in administered prices (prices subject to Government regulation, such as rates for telephone calls and prices for gasoline and other petroleum derivatives, and prices governed by contracts with vendors, such as fares charged for certain public transportation) and rising oil prices in the world markets, the inflation rate began to rise in Brazil during the fourth quarter of 2002. The broad consumer rate index (IPCA), which the Central Bank uses for inflation-targeting purposes, began to accelerate in October 2002, increasing 1.3% in October 2002, 3.02% in November 2002, 2.1% in December 2002 and 2.3% in January 2003. As a result, the inflation rate, as measured by IPCA, increased from 7.7% for the 12 months ending June 30, 2002 to 12.5% for the 12 months ending December 31, 2002; it continued to rise to 17.2% for the 12 months ending May 31, 2003. The Central Bank responded by increasing its overnight Over/Selic interest rate target from 18% to 21% on October 14, 2002, to 22% on November 20, 2002, to 25% on December 18, 2002, to 25.5% on January 22, 2003 and to 26.5% on February 19, 2003. Following these increases, the inflation rate, as measured by IPCA, declined to 9.3% for 2003.