QuickLinks -- Click here to rapidly navigate through this documentExhibit 99.c

1

Budget Statement

Economic and budget policy guidelines

1 Budget Statement

1.1 Responsibility for Sweden in unsettled times

The international situation has been marked for some considerable time by a lack of confidence and economic downturn. The war in Iraq has exacerbated the uncertainties. Its consequences—for the people of Iraq and democracy in that country, and for the international economy—have yet to be revealed. It is important that we continue to work for peace and security internationally, in accordance with the principles of the United Nations.

All countries are affected by the unstable situation. In Sweden and in the world around us, banks and financial institutions are downgrading their growth forecasts. Companies and investors are playing a waiting game. Consumers are holding back. Growth and employment are suffering. The public finances are coming under strain.

Yet in international terms, the Swedish economy still remains strong. By comparison with other European countries, employment and growth rates are high and unemployment low. Sweden is one of the few countries that has a surplus in its public finances. This is because we in Sweden made sure to secure safety margins in time. So as not to be obliged to make big savings during future economic downturns, the Government and Riksdag set targets for public finances surpluses and introduced expenditure ceilings. Now, when the decline has become prolonged, it is obvious how important this was.

The successes of recent years—a strong economy, a high rate of growth and low unemployment—constitute a good foundation for aggressive policies for welfare, employment and sustainable development. In spite of the downturn, it has been possible to implement a series of reforms that will enter into effect this year and next. More resources are being allocated to health care and dental care. Parental insurance is being enhanced, the system of maximum charges has been brought in as has universal pre-school for 4 and 5-year-olds. The municipalities are being given extra resources to employ more teachers and other specialist staff in schools. Pensions are being improved and the upper secondary study grant is being extended by a month. The expansion of higher education and investments in research are continuing. Environmental appropriations are going up. Housing construction will be stimulated.

These reforms are important for Sweden's development and competitiveness so they remain firm commitments. In addition, two tasks that are crucial to future growth and welfare will require major investments: to create a more humane working life where fewer people become sick, and to open up the labour market to new Swedes. These are tasks that will require resources, a long-term approach and broad cooperation.

Yet the harsher economic climate calls for caution as well. We need to cut our expenses. Healthy public finances are the foundation for welfare and employment. This foundation is the last thing that should be put at risk in times of great uncertainty. The economic policy objectives must remain firm and the expenditure ceilings must be kept. This is why the Government and the parties cooperating with us are proposing expenditure cuts.

The aim is to create good conditions for a rapid recovery of growth in Sweden when the international downturn ends. Thus, the Government is proposing measures to enhance conditions for growth, restrain joblessness and increase the employment rate. Work and growth lay the foundation for welfare. Hence, a strong basis is being ensured for forward-looking policies to promote welfare and full employment. Sound public finances, stable prices and efficient wage formation are essential conditions for achieving our objectives.

Since 1994 growth in Sweden has been higher than both the OECD and the EU average. Sweden's public finances are currently among the strongest in the EU. Inflation is low, and unemployment and

3

the need for social assistance have declined. The employment rate is among the highest in the whole of the EU. Sweden is also the leading EU country in terms of economic reforms.

The election in autumn 2002 resulted in an agreement between the Swedish Social Democratic Party, the Left Party and the Green Party on 121 points for a more secure, fairer and greener Sweden. This agreement made it clear that our common policy for Sweden is based on our conviction that the ecological, social and economic dimensions must be interwoven so as to generate sustainable development that is good for Sweden. We want, together, to work on the basis of clearly formulated policies for a green, gender-equal welfare society, where sustainable growth, full employment and secure welfare are advanced by technological development, modernisation, broad participation and reduced disparities.

Our policies must be characterised by order and responsibility. In unsettled times clearly stated priorities are more urgently required, but so, above all, is a common assumption of responsibility. The Government and the parties cooperating with us are prepared to shoulder this responsibility. Broad cooperation is the best environment for Sweden's development. Our responsibility lies with our country, but also extends to the world around us, on which we are so dependent.

Forms for cooperation

The Spring Fiscal Policy Bill is based on an agreement between the Social Democratic Government, the Left Party and the Green Party, which jointly endorse the guidelines for economic policy, budget policy and the supplementary budget for 2003.

1.2 The state of the economy

1.2.1 International developments

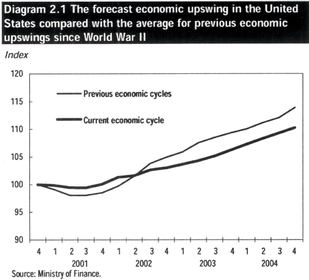

The international economy is marked by uncertainty. Growth has been weaker than expected and remains so. The war in Iraq and the further course of events there will have a crucial effect on economic developments.

In the euro zone, the trend for household consumption and business investment has been subdued. Unemployment has continued up. A number of countries are facing strained public finances and may have difficulty living up to the demands of the EU's Stability and Growth Pact this year. No upturn is expected in the euro zone economy before the end of this year, at the earliest. Since the euro zone accounts for some 40 per cent of total Swedish exports, the weak trend will have an adverse impact on Sweden's economy.

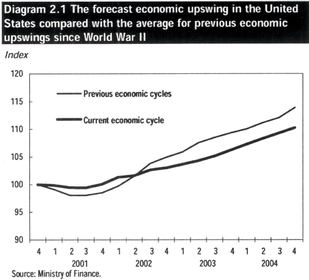

Developments in the United States appear highly uncertain. The latest statistics suggest a certain slackening of household consumption. In Japan the prospects for growth remain dim and the situation is still precarious.

1.2.2 The outlook for Sweden

Like other countries, Sweden is feeling the effects of the international economic downturn. Growth is forecast to be just 1.4 per cent this year, rising to 2.4 per cent in 2004.

4

Table 1.1 GDP growth in Sweden and other countries

Percentage change

| | 1999

| | 2000

| | 2001

| | 2002

|

|---|

| Sweden | | 4.6 | | 4.4 | | 1.1 | | 1.9 |

| United States | | 4.1 | | 3.8 | | 0.3 | | 2.4 |

| Japan | | 0.2 | | 2.8 | | 0.4 | | 0.3 |

| EU | | 2.8 | | 3.5 | | 1.6 | | 1.0 |

| OECD | | 3.2 | | 3.9 | | 0.8 | | 1.8 |

Sources: National sources, Ministry of Finance.

Table 1.2 Balance of resources

| |

| | SEK bn

| | Volume change in per cent

|

|---|

| | 2002

| | 2002

| | 2003

| | 2004

|

|---|

| Household consumption expenditure | | 1139 | | 1.3 | | 1.9 | | 2.2 |

| Public sector consumption expenditure | | 656 | | 2.1 | | 0.5 | | 0.2 |

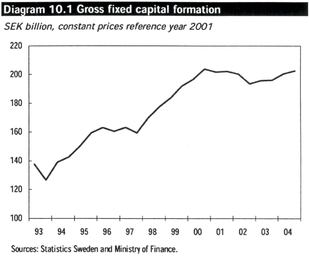

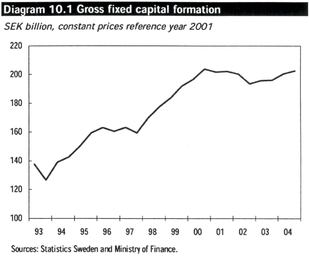

| Gross fixed capital formation | | 400 | | -2.5 | | -0.5 | | 2.9 |

| Stocks(1) | | 4 | | -0.1 | | 0.2 | | 0.0 |

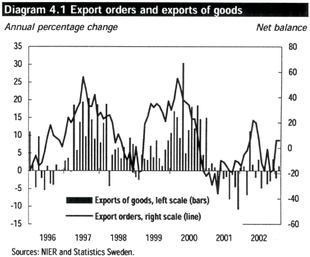

| Exports | | 1012 | | 0.4 | | 2.3 | | 7.0 |

| Imports | | 871 | | -2.7 | | 2.3 | | 6.0 |

| GDP | | 2340 | | 1.9 | | 1.4 | | 2.4 |

- (1)

- Contribution to GDP growth.

Sources: Statistics Sweden, Ministry of Finance.

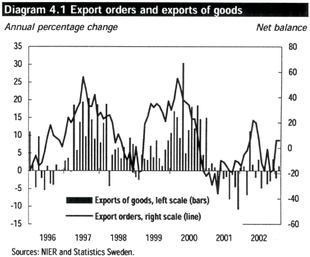

The weakness of international demand has obvious repercussions for Swedish exports. Despite some improvement in recent months, new export orders remain weak. Demand for Swedish investment goods, however, is expected to pick up gradually in the course of the year as international recovery begins. Imports to Sweden are expected to increase this year when stock liquidation is completed and demand in the economy begins to grow.

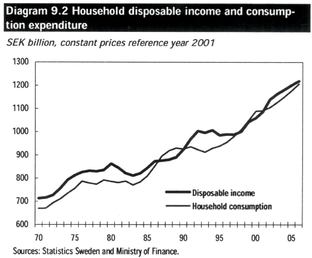

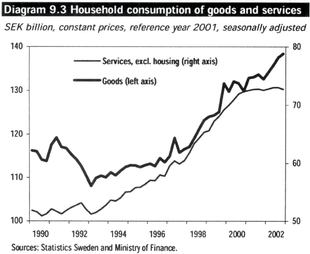

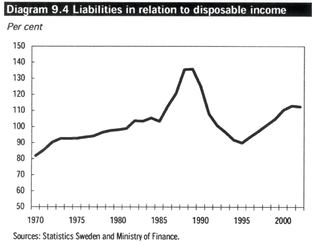

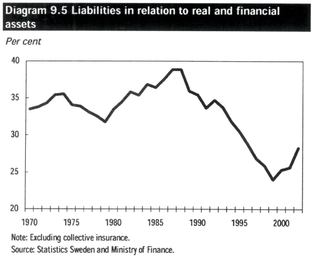

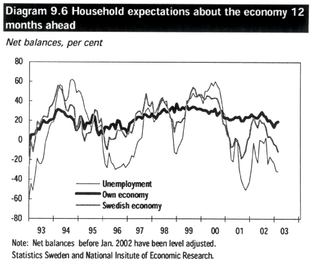

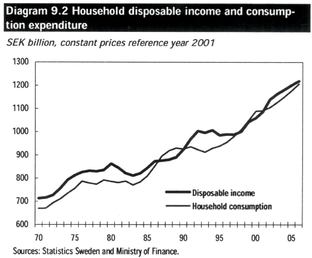

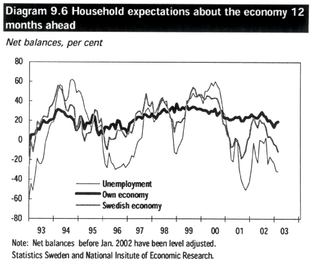

The international downturn is restraining household demand. Nevertheless, demand is forecast to grow this year on aggregate, partly because the economic position of households remains strong and interest rates low. A gradual diminishing of uncertainty about the economic situation in the world around—and hence also in Sweden—is expected to contribute to increasing household demand.

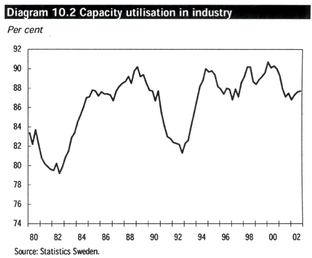

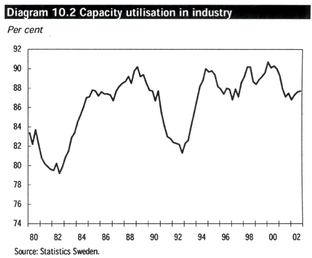

In consequence of a previous substantial expansion of capacity and a lower rate of growth in production, business investments are expected to continue weak this year as well.

5

Table 1.3 Key indicators

Annual percentage change, unless otherwise indicated

| | 2002

| | 2003

| | 2004

|

|---|

| CPI(1) | | 2.4 | | 2.4 | | 1.8 |

| Hourly wage | | 4.0 | | 3.5 | | 3.5 |

| Open unemployment(2) | | 4.0 | | 4.5 | | 4.3 |

| Labour market programmes(2) | | 2.6 | | 2.2 | | 2.0 |

| Number of persons employed | | 0.1 | | -0.3 | | 0.3 |

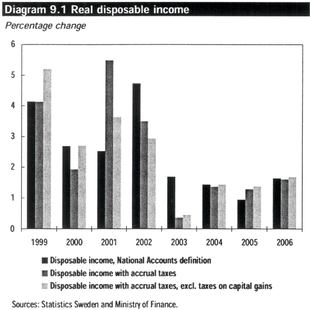

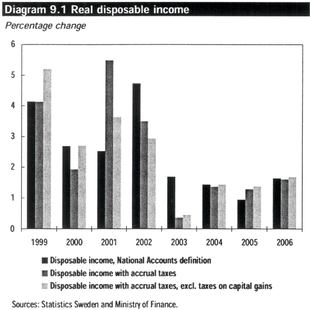

| Real disposable income(3) | | 4.7 | | 1.7 | | 1.4 |

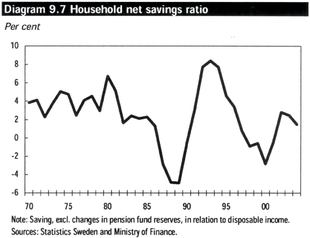

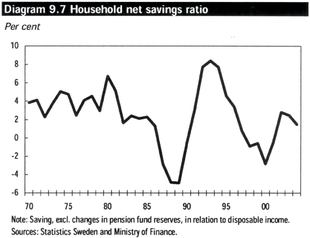

| Household net saving ratio, level(4) | | 2.8 | | 2.6 | | 1.9 |

| Balance on current account(3) | | 4.2 | | 4.3 | | 4.1 |

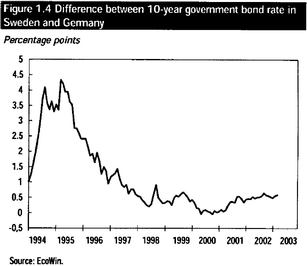

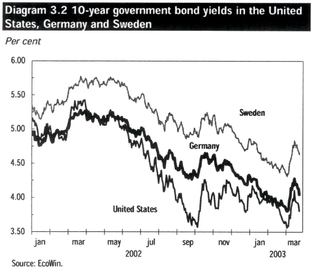

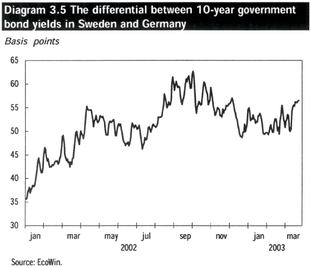

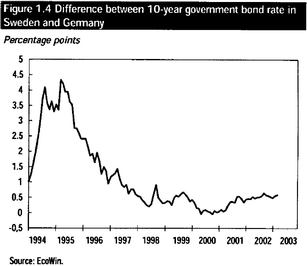

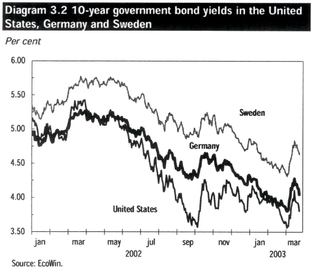

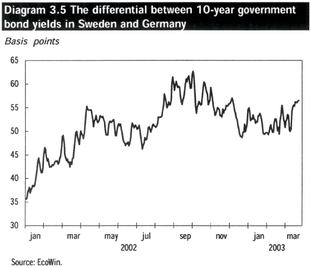

| German 10-year government bond rate(1) | | 4.8 | | 4.3 | | 5.0 |

| Swedish 10-year government bond rate(1) | | 5.3 | | 4.9 | | 5.4 |

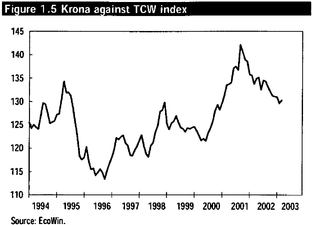

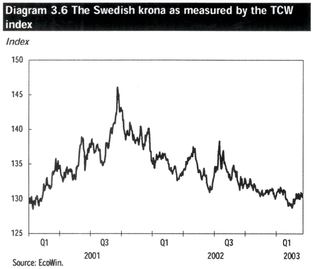

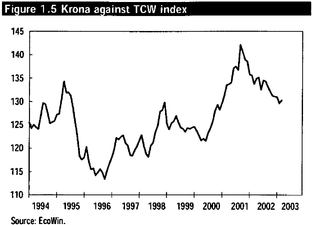

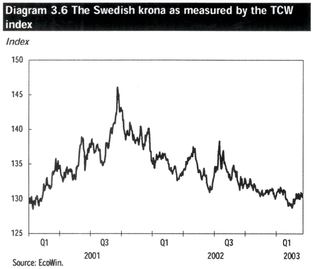

| TCW index(1) | | 133.7 | | 128.8 | | 127 |

(1)- Annual average.

- (2)

- Per cent of labour force.

- (3)

- Per cent of GDP.

- (4)

- Excluding savings in occupational pension schemes.

Sources: Statistics Sweden, National Labour Market Board, National Mediation Office, Riksbank and Ministry of Finance.

Table 1.4 Employment, unemployment and wage growth

| | 1995

| | 1996

| | 1997

| | 1998

| | 1999

| | 2000

| | 2001

| | 2002

| | 2003

| | 2004

|

|---|

| Number of persons employed(1) | | 3986 | | 3963 | | 3922 | | 3979 | | 4069 | | 4159 | | 4239 | | 4244 | | 4232 | | 4247 |

| | of whom in private sector(1) | | 2697 | | 2698 | | 2695 | | 2735 | | 2805 | | 2888 | | 2969 | | 2960 | | — | | — |

| | of whom in public sector(1) | | 1287 | | 1263 | | 1223 | | 1240 | | 1260 | | 1264 | | 1262 | | 1278 | | — | | — |

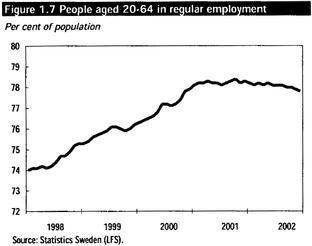

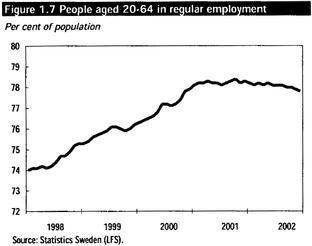

| Regular employment ratio(2) | | 74.9 | | 74.7 | | 73.9 | | 74.6 | | 75.9 | | 77.2 | | 78.2 | | 78.1 | | 77.6 | | 77.6 |

| Open unemployment(3) | | 7.7 | | 8.1 | | 8.0 | | 6.5 | | 5.6 | | 4.7 | | 4.0 | | 4.0 | | 4.5 | | 4.3 |

| Cyclically dependent labour market programmes(3) | | 4.6 | | 4.7 | | 4.5 | | 4.1 | | 3.3 | | 2.6 | | 2.5 | | 2.6 | | 2.2 | | 2.0 |

| Hourly wage(4) | | 3.3 | | 6.0 | | 4.5 | | 3.8 | | 3.4 | | 3.7 | | 4.3 | | 4.0 | | 3.5 | | 3.5 |

| Productivity growth, private sector(4) | | 3.6 | | 1.9 | | 5.2 | | 2.0 | | 2.6 | | 4.1 | | 0.6 | | 4.2 | | 2.6 | | 2.3 |

Note: In LFS, Church of Sweden employees were not transferred from the local authority sector to the private services employed in the public sector is overestimated by approximately 22 000 in 2000.

- (1)

- In thousands.

- (2)

- Population aged 20-64 in regular employment as a percentage of total population in the age group.

- (3)

- In per cent of the labour force.

- (4)

- Annual percentage change.

Sources: Statistics Sweden, National Labour Market Board, National Mediation Office and Ministry of Finance.

6

Table 1.5 Employment and unemployment disaggregated by sex

| | 1998

| | 1999

| | 2000

| | 2001

| | 2002

|

|---|

| | Women

| | Men

| | Women

| | Men

| | Women

| | Men

| | Women

| | Men

| | Women

| | Men

|

|---|

| Number of persons employed(1) | | 1901 | | 2079 | | 1947 | | 2121 | | 1992 | | 2167 | | 2036 | | 2203 | | 2047 | | 2197 |

| | of whom in private sector(1) | | 967 | | 1768 | | 997 | | 1808 | | 1037 | | 1852 | | 1080 | | 1891 | | 1080 | | 1879 |

| | of whom in public sector(1) | | 932 | | 308 | | 949 | | 311 | | 953 | | 312 | | 954 | | 307 | | 965 | | 314 |

| Open unemployment(2) | | 6.0 | | 6.9 | | 5.2 | | 5.9 | | 4.3 | | 5.0 | | 3.6 | | 4.3 | | 3.6 | | 4.4 |

Note: In LFS, Church of Sweden employees were not transferred from the local authority sector to the private services sector until 2001. As a result, the number of people employed in the public sector is overestimated by approximately 22 000 in 2000.

- (1)

- In thousands.

- (2)

- In per cent of the labour force.

Source: Statistics Sweden.

The municipal sector

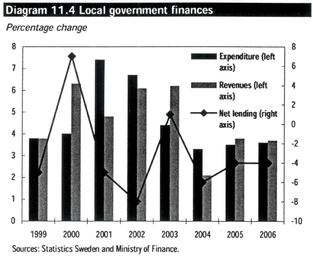

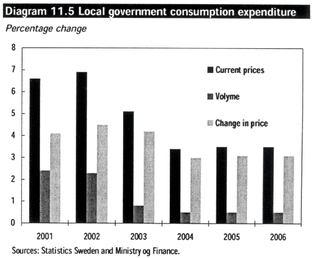

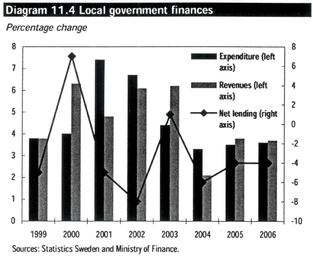

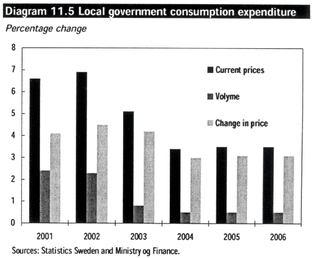

Municipal consumption underwent strong growth in 2001 and 2002, while the rise in employment lost momentum and the tax base grew rather more slowly than in previous years as a result. The figures for 2002 indicate a decline in the number of municipal and county councils with positive results. Tax increases averaging SEK 0.65 per SEK 100 in 2003 (corresponding to SEK 8.5 billion in increased tax revenues) and the extension of the temporary employment support system in 2004 have helped improve the finances of the local government sector.

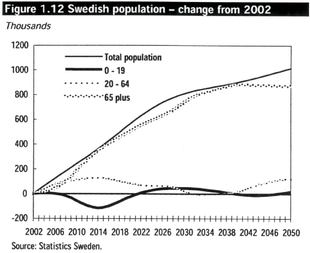

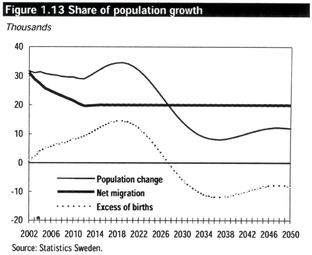

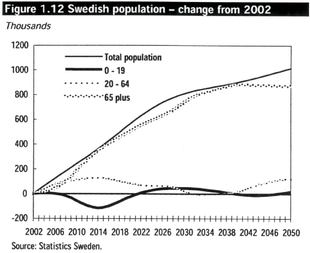

Since 2000 local authorities have been required to balance their budgets. Each generation must bear the costs of the services it approves and consumes. The demographic development makes great demands on local authorities to use resources efficiently, so as to sustain welfare in the future. An inquiry has been undertaken and proposals presented regarding the balanced budget requirement. The matter is currently being processed by the Government Offices.

In order to support local authorities in a particularly vulnerable position, the Government has entered into agreements with 36 municipalities and four county councils on economic help aimed at bringing about a reorganisation of activities and achieving a balanced economy. These measures have proved highly effective.

In the long term, low unemployment and high numbers of people in work are vital to the prospects of local authorities managing to maintain welfare in the long run.

The labour market

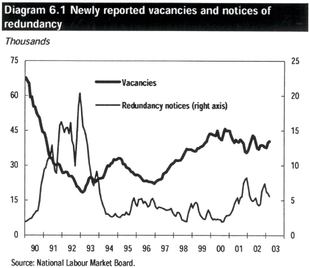

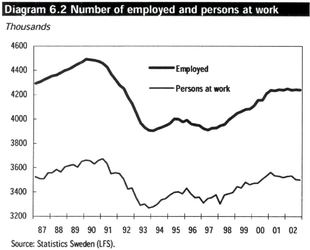

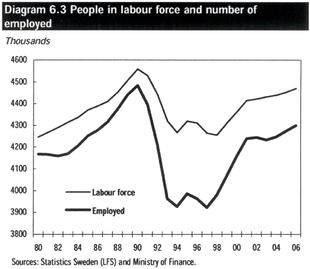

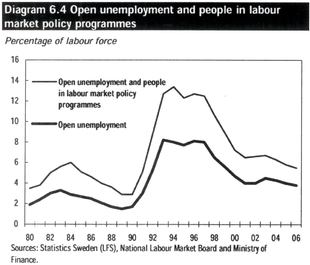

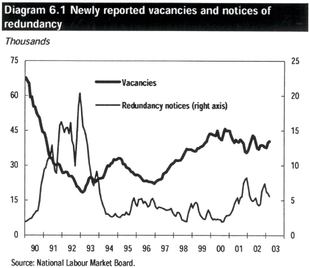

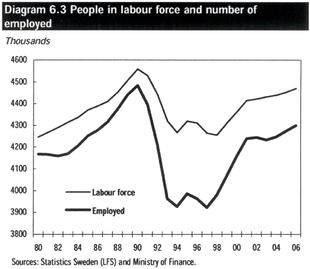

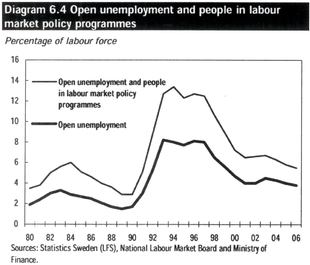

Between 1997 and 2002 the number of people in work rose by approximately 320 000. The bulk of this increase came in the private sector, where the number of people employed climbed by some 260 000. Open unemployment has hovered around the four per cent mark since the end of 2000.

The relatively weak growth this year and last is having an adverse effect on the labour market. Open unemployment is forecast to rise this year to an annual average of 4.5 per cent. Next year, however, unemployment is expected to decline as the employment figures increase again. The proportion of people aged 20 to 64 in regular employment is predicted to be 77.6 per cent in 2004.

7

Medium-range outlook

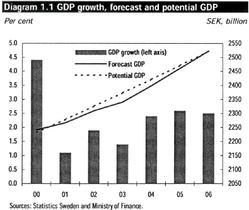

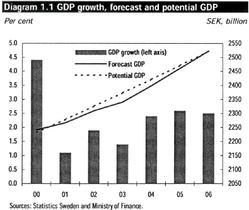

Cyclical fluctuations are hard to predict in the years after 2004. No forecast is therefore made regarding the state of the economy. A projection is, however, presented.

The calculations are based on an assumption that there will be unexploited resources at the end of 2004 that can be taken into use without inflationary bottlenecks arising in the Swedish economy. GDP growth is thus slightly higher than the long-term trend in 2005 and 2006.

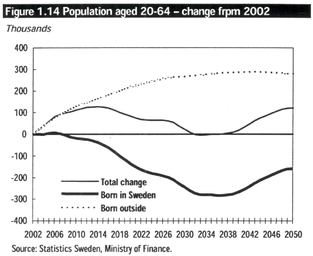

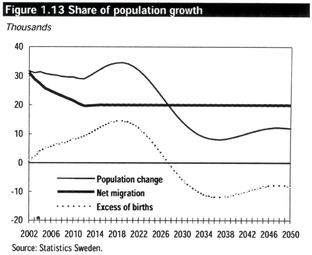

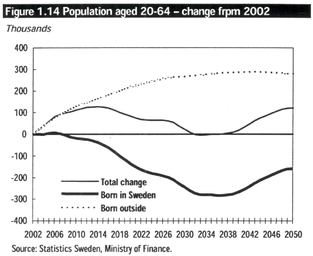

The trend for employment is good and open unemployment falls to 3.8 per cent in 2006. Although the population aged 20 to 64 will increase, it is mostly age groups with relatively low labour force participation and low employment rates that will grow larger. Consequently, the rate of regular employment in the 20-64 age bracket will not change markedly in the years up to 2006.

Table 1.6 Medium-term projection

| | 2002

| | 2003

| | 2004

| | 2005

| | 2006

|

|---|

| GDP growth | | 1.9 | | 1.4 | | 2.4 | | 2.6 | | 2.5 |

| Rate of regular employment(1) | | 78.1 | | 77.6 | | 77.6 | | 77.7 | | 77.8 |

| Government saving | | 1.1 | | 0.4 | | 1.0 | | 1.4 | | 2.1 |

- (1)

- Percentage of population aged 20-64 in regular employment.

1.3 Fiscal policy

The aim of the fiscal policy is to maintain surpluses in the public finances. There are several reasons for this objective.

- —

- The proportion of elderly people in the population will grow substantially in future. This will mean higher costs for pensions, health and social care, while revenues will grow more slowly since the working population is likely to decline relative to the total population. To prepare Sweden for this situation, public debt should be reduced.

- —

- Those who are dependent on welfare must be able to feel confident that it will continue to function even in harder times when it is needed most. Without strong public finances, there is a risk that every economic downturn will force major cutbacks that will diminish public confidence and undermine the will to pay for welfare when times are good.

- —

- To make it possible to pursue an active stabilisation policy without deficits becoming too large, a safety margin is required so that fiscal policy can help to moderate economic fluctuations.

There are two overall budget policy objectives: the public finances surplus target and the expenditure ceilings.

1.3.1 Surplus target for sound public finances

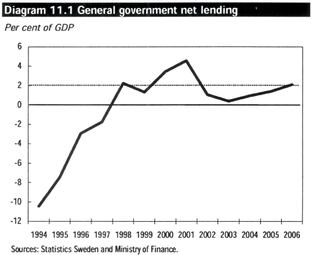

The surplus target entails that public finances are required to show a surplus of 2 per cent of GDP on average over a business cycle. This implies that a surplus of less than 2 per cent can be allowed in an economic slowdown, so as to help sustain private sector income levels and limit the downturn. Conversely, during an upswing in the business cycle, a larger surplus will restrain economic activity and reduce the risk of overheating. The surplus is adjusted to take into account the economic situation and the level of resource utilisation in the Swedish economy.

In the 2003 Budget Bill, the Government made the assessment that in the light of the economic situation and the level of resource utilisation in the economy, a surplus of 1.5 per cent of GDP in 2003 was compatible with the surplus target. However, if the economy developed less well than anticipated, a

8

smaller surplus would be acceptable. Compared with the forecast in the Budget Bill, 2003 growth has been revised downwards by more than 1 percentage point.

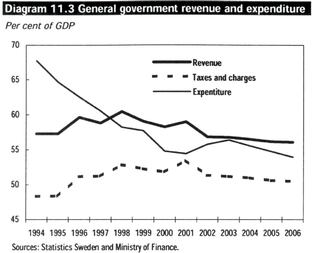

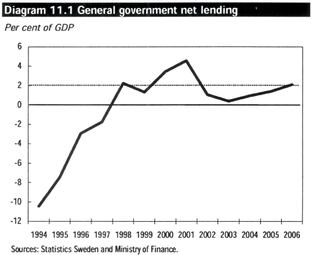

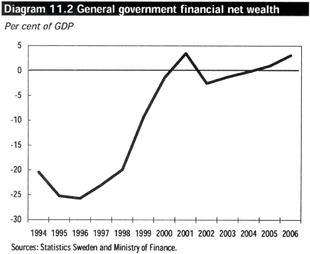

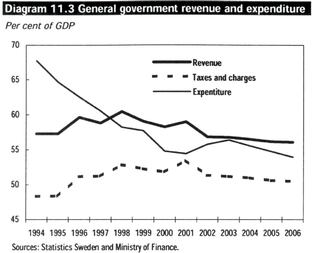

Since the target of a 2 per cent surplus over the business cycle began to apply in 2000, the annual surplus in the public finances has averaged 3 per cent of GDP. The estimated surplus in 2003 is 0.4 per cent of GDP. After the measures proposed in this bill, it is calculated that the average surplus for the period 2000 to 2006 will be 2.0 per cent. This means that public savings are in line with the overall target of a surplus of 2 per cent over an economic cycle.

Table 1.7 Public finances

Per cent of GDP

| | 2000

| | 2001

| | 2002

| | 2003

| | 2004

| | 2005

| | 2006

|

|---|

| Expenditure ratio | | 54.8 | | 54.4 | | 55.8 | | 56.4 | | 55.5 | | 54.7 | | 53.9 |

| Revenue ratio | | 58.2 | | 59.0 | | 56.8 | | 56.8 | | 56.5 | | 56.1 | | 56.1 |

| Tax ratio incl. EU contribution | | 52.4 | | 54.0 | | 51.8 | | 51.5 | | 51.2 | | 50.8 | | 50.7 |

| Financial saving | | 3.4 | | 4.6 | | 1.1 | | 0.4 | | 1.0 | | 1.4 | | 2.1 |

| Net debt | | 1.3 | | -3.5 | | 2.5 | | 1.2 | | 0.2 | | -1.0 | | -3.1 |

| Consolidated gross debt | | 52.9 | | 54.4 | | 52.4 | | 51.0 | | 50.0 | | 48.4 | | 46.4 |

Sources: Statistics Sweden, Ministry of Finance.

By international comparison, Sweden's public finances are strong. In 2002 Sweden had one of the largest public sector surpluses in the EU, while a number of large EU countries in contrast had substantial deficits to show. Sweden will continue to note surpluses in 2003 and 2004 while the EU countries as a whole will show deficits.

Table 1.8 Public sector financial savings in Sweden and other countries

Per cent of GDP

| | 2002

| | 2003

| | 2004

|

|---|

| Sweden | | 1.1 | | 0.4 | | 1.0 |

| EU | | -2.0 | | -1.9 | | -1.6 |

| Euro zone | | -2.2 | | -2.1 | | -1.8 |

| Germany | | -3.7 | | -3.3 | | -2.6 |

| France | | -2.7 | | -2.9 | | -2.5 |

| Italy | | -2.3 | | -2.1 | | -2.8 |

| Finland | | 3.2 | | 2.9 | | 3.6 |

| UK | | -1.4 | | -1.4 | | -1.3 |

| Denmark | | 2.2 | | 2.4 | | 2.9 |

| USA | | -3.1 | | -3.0 | | -2.7 |

| Japan | | -7.9 | | -7.7 | | -7.8 |

Sources: OECD Economic Outlook 72, Dec. 2002, and Ministry of Finance.

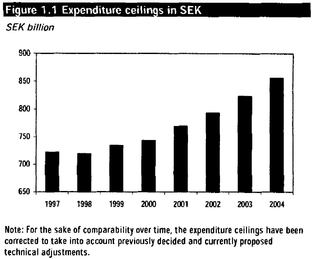

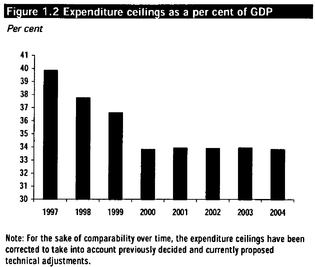

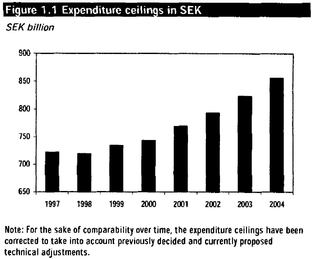

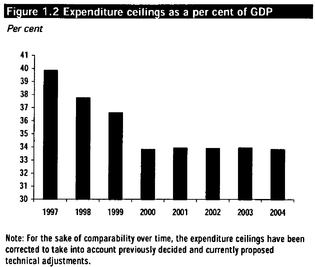

1.3.2 Expenditure ceilings

Expenditure ceilings play an instrumental role in guiding budget policy. The ceilings are set three years in advance. Central government expenditure is then not allowed to exceed these ceilings. The expenditure ceilings prevent the use of temporarily higher income to finance permanently higher expenditure.

9

On the whole, the system has functioned well and has helped maintain balance in the growth of expenditure during the good years, which in turn has enabled Sweden to face the international economic slowdown with strong public finances. A working party including representatives from the parties in cooperation is currently following up the Budget Act.

The expenditure ceilings have been met every year since their introduction in 1997.

The Government considers there is a risk of the expenditure ceilings for 2003 and 2004 being exceeded unless action is taken to prevent this. The Government therefore proposes a number of measures to rein in expenditure growth and make it possible to meet the ceilings for 2003 and 2004. One crucial component consists of the measures now proposed to reverse the trend towards increasing numbers of people on sick leave. In addition, certain reforms announced earlier will be postponed until later in this Government's term of office. Further, the Government intends to introduce restrictions on the expenditures allowed under certain appropriations. The Government is monitoring expenditure developments on an ongoing basis and will take additional measures if the expenditure ceilings come under threat. The expenditure ceilings must be met.

Table 1.9 Overall impact on expenditure of appropriation cuts and restrictions

SEK million

Appropriation cuts

| | 2003

| | 2004

|

|---|

| Sickness allowance to equal unemployment benefit | | 300 | | 600 |

| Delay in raising sickness insurance ceiling | | 920 | | 2 000 |

| New sickness insurance qualifying income | | 565 | | 1 140 |

| Longer period of sick pay | | 669 | | 1 338 |

| Delay in raising parental insurance ceiling | | 395 | | 865 |

| The partly unemployed | | | | 550 |

| Exits from unemployment | | | | 1 000 |

| Priority study grants | | | | 126 |

| Education recruitment grants | | | | 700 |

| Higher maximum child care charges | | | | 240 |

| Culture | | | | 92 |

| Environment | | 150 | | 315 |

| Infrastructure | | 500 | | 1 000 |

| Other appropriation cuts | | 404 | | 785 |

Expenditure restrictions

|

|

|

|

|

|---|

| Defence | | 1 027 | | 373 |

| Development assistance | | 400 | | -200 |

| Miscellaneous | | 631

| | -461

|

| Total impact on expenditure | | 5 287

| | 10 810

|

Defence equipment is one category of expenditure that will be postponed. Part of the increase in development assistance will be transferred from 2003 to 2004. As from 1 July, the regulations for sickness allowances will be changed to make compensation in the event of sickness equivalent to the compensation paid by unemployment insurance. This will mean that an unemployed person who is given a sickness certificate will no longer receive more compensation when sick than when healthy.

The higher ceiling in the sickness and parental insurance systems will be delayed. The contact days for which a temporary parent's allowance can be claimed will be eliminated. A number of measures are expected to result in less people on sick leave, which will mean lower expenditures. These include the

10

government bill that has already been presented on improvements in sick leave procedures (Gov. bill 2003/03:89); the proposals in this bill on changes in the calculation of qualifying income in the sickness insurance system; a more consistent application of the rules on moving from sickness allowance to sickness compensation; the proposal for a consistent application of the initial no-benefit day regulations; and upcoming proposals for a system of financial incentives for employers.

The regulations for unemployment benefits in the event of partial unemployment will be applied more consistently. Efficiency measures will be implemented in labour market policy with a view to promoting a speedier transition from unemployment to work.

Adults who have already completed three-year upper secondary education will no longer be eligible for the higher study grant for adult education. The financial framework available to local authorities for recruitment grants for adult education will shrink. The ceiling on maximum charges for child care will be raised in 2004, though the ceiling of 3 per cent of parental income will remain in place.

The introduction of free entry to museums will be postponed. Infrastructure investments will be delayed. The Government estimates that Sweden's EU contribution will be lowered by some SEK 900 million in 2003 as a result of the EU budget surplus in 2002.

A higher total in the municipal equalisation system, moreover, will entail an adjustment of SEK 3 billion in the expenditure ceiling in 2003.

In view of the short time available for planning between the Riksdag election and the 2003 Budget Bill, the Government did not present a proposed expenditure ceiling for 2005 in the autumn. The Government announced that it would return to the issue of expenditure ceilings for 2005 and 2006 in the Spring Fiscal Policy Bill instead.

Since 2001 the expenditure ceiling has been set at levels that essentially mean the ceiling is constant as a percentage of GDP, given trend growth of about 2 per cent per year. The slight rise in the expenditure ceiling as a percentage of GDP between 2002 and 2003 reflects the relatively low growth rate this year. Growth next year is forecast to increase to over 2 per cent, which will result in a slight lowering of the expenditure ceiling expressed in terms of GDP.

Calculations of general government expenditure show that there is a risk that the demographic trend, with an ageing population, will lead the expenditure ratio to grow. The desirability of avoiding deficits and major expenditure cuts as the number of older citizens increases is an important argument for keeping expenditure rises in check and conducting policies to promote a higher rate of employment, which in turn will boost revenues.

If the expenditure ceilings are held technically constant as a proportion of GDP and growth is on trend, the expenditure ceiling would be SEK 890 billion for 2005 and SEK 927 billion for 2006. The Government intends to make its proposals for expenditure ceilings in 2005 and 2006 later, in the 2004 Budget Bill.

11

1.4 Prices and wages

1.4.1 Stable prices

Stable prices are a fundamental prerequisite for a successful economic policy. A high rate of inflation, particularly when difficult to foresee, has negative distributional effects. In addition, a high rate of inflation makes for poorer prospects of strong, sustained growth, and so also undermines the chances of a stable high rate of employment and welfare.

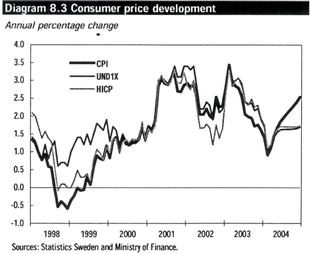

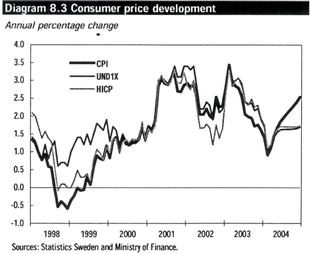

The overriding task of monetary policy has been defined by the Riksdag as price stability. The Riksbank, which conducts monetary policy as an independent institution, has defined price stability such that the increase in the consumer price index must be limited to 2 per cent, plus or minus 1 per cent. The Government supports the orientation of monetary policy and endorses the target for inflation.

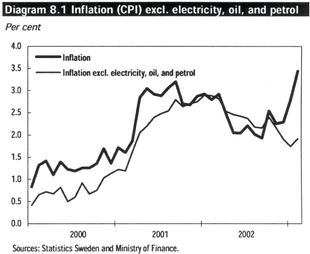

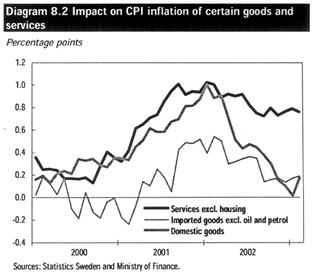

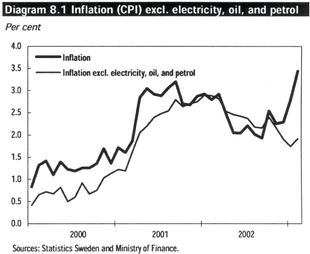

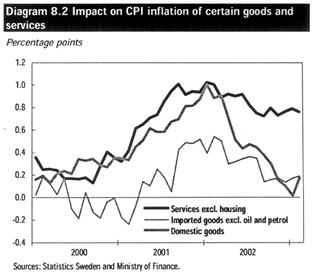

Inflation is forecast to be high temporarily during the first six months of this year, partly because of higher oil and electricity prices. Lower inflationary pressure in Sweden and weaker import price growth will lead inflation gradually to fall back to approximately 2 per cent, i.e. close to the target set by the Riksbank, half way through the year. In the following years, inflation is expected to remain in line with the target.

In recent years monetary policy has been based on forecasts of UND1X for the coming two years. UND1X is a measure of inflation based on the consumer price index, but excluding the direct effects of

12

changes in interest rates, taxes and subsidies. This year UND1X inflation is forecast to be 2.6 per cent as an annual average. Next year UND1X inflation is expected to decline to 1.5 per cent.

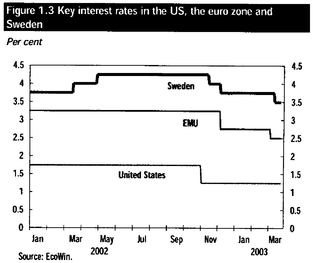

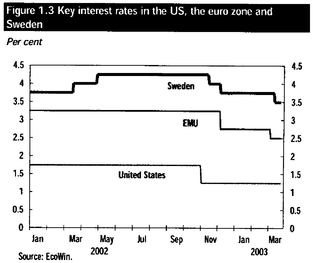

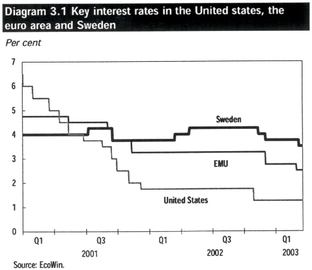

The interest rate and the krona

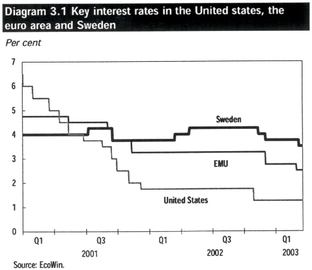

International interest rates have continued to fall. As a result of the uncertain state of the economy, world stock markets have continued to lose value. The expected upturn in the economy has been delayed and the outlook for corporate profits has weakened.

Several central banks have continued to lower their interest rates in 2002 and early 2003, in an attempt to bolster economic recovery. Towards the end of 2002 and at the beginning of 2003 interest rates have fallen particularly sharply in Europe. The Riksbank has lowered its key rate by 0.75 percentage points to 3.5 per cent.

The krona has grown stronger since autumn 2001, particularly against the US dollar.

13

EMU

The introduction of euro notes and coins on 1 January 2002 was a historic and significant step in European integration. The euro is now a reality in large parts of Europe.

Sweden has elected not to participate in the currency union from the start. However, the Riksdag decided in 1997 that Sweden should keep the door open for entry at a later date and meanwhile see to it that the country is prepared for possible Swedish participation in the single currency.

The Riksdag has decided that a referendum on the introduction of the euro as Sweden's currency will be held on 14 September 2003. All parties have declared that they are prepared to respect the outcome of the referendum.

Participation in the European exchange rate cooperation, ERM2, is not being considered at the present time.

1.4.2 Wage formation

Efficient wage formation is of crucial importance for sustaining the satisfactory development of the national economy. Wage increases within the given national economic parameters make for lower unemployment and higher employment and production levels. Moderate nominal wage increases are essential if it is to be possible to meet the Government's target of 80 per cent of the population aged 20-64 in regular employment.

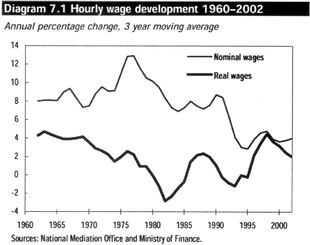

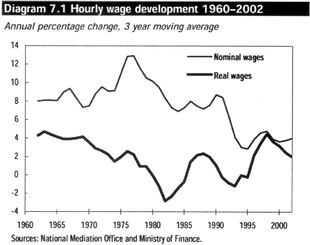

Between 1994 and 2001, real wages have gone up on average by 3 per cent per year. For the sake of comparison, in the 1980s they rose by less than 0.5 per cent. Nominal wage increases in the latter part of the 1990s, however, were only about half as high as in the 1980s.

The trend in recent years shows that moderate nominal wage increases and augmented responsibility on the part of the social partners create good conditions for low unemployment and healthy real wage growth.

In 2001 and 2002, however, nominal wages rose more rapidly than in previous years, despite the more subdued state of the economy and employment trends. In 2001 wage increases across the economy came to 4.3 per cent. This is higher than in the euro zone and the United States. Total wage increases are estimated to have been slightly more restrained last year, at about 4 per cent. Wage increases were slightly higher in the public sector than in the business sector.

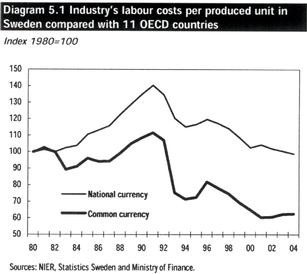

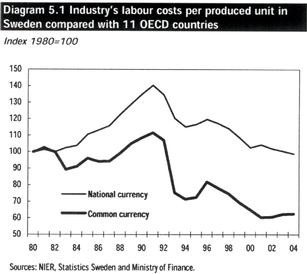

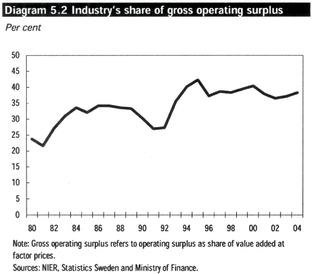

Over the period 1996-2001, labour cost growth in the Swedish business sector has exceeded the EU average by about 1.5 percentage points per year, measured in the national currency. Despite this, Swedish competitiveness has been enhanced over the period due to strong productivity growth and the falling krona.

The Government assumes that the high rate of nominal wage growth witnessed in recent years will be adjusted downwards in future so as to avoid any weakening of Sweden's competitiveness. This is

14

vital in order to sustain the positive trend for the economy and to achieve the Government's employment target. It is also important that the wage formation process allows changes in relative wages, within the framework of the overall rate of wage increases that the economy can tolerate. For the sake of employment and welfare, it is of vital importance that the social partners demonstrate will and responsibility in coming collective negotiations.

Gender-related wage discrimination must be overcome. Women are paid 82 per cent of men's wages. Correcting for age, education, working hours and sector, the difference shrinks to give a figure of 92 per cent. The reasons for this disparity are complex. They include the value assigned to different types of work and the effects of segregation in the labour market, as well as direct wage discrimination.

The new Act concerning Equality between Men and Women is one instrument for evening out unjustified gender pay differentials. Wage formation is an issue that the social partners must address; unjustified pay differentials attributable to sex are an infringement of the law. The Government is monitoring action in this area via the Office of the Equal Opportunities Ombudsman and the National Mediation Office. The outcome of efforts made by the social partners in this area will determine the need for further measures, such as tougher legislation.

The Government intends to present an action plan for increased equality between women and men in the course of the year. The action plan is to propose means of ensuring that structural wage differentials between women and men diminish.

1.5 Jobs and growth—for welfare and justice

Since 1994 the Government has conducted a long-term policy to strengthen the prospects for economic growth in Sweden. This policy is based on macroeconomic policies to promote stability and sound public finances. A range of reforms has been carried out, aimed, among other things, at improving the functioning of the labour market and increasing competition in the economy. The average marginal effects on incomes from work have been lowered by five percentage points since 1999. Substantial investments are being made in education, research and the infrastructure.

The policies are having results. Over the period 1994-2002, GDP growth in Sweden has averaged 3.1 per cent per year. For comparison, the average annual growth rate for the EU countries has been 2.3 per cent. The Government's policies are intended to further strengthen Sweden's position.

The conditions are better than they have been for a long time. In Lisbon in 2000, the EU set the objective of becoming the most competitive and dynamic knowledge-based economy in the world, capable of sustainable economic growth with more and better jobs and greater social cohesion. Each year there is a follow-up of the different measures taken by the Member States in pursuit of these objectives, using comparisons of about 40 different indicators, such as employment, growth, inflation, price trends, etc.

The latest follow-up conducted by the European Commission shows that Sweden is the country that has most top-three ratings in the various comparisons. Sweden is held up as an example. The Commission draws attention to Sweden as a leader in terms of economic reforms, employment, the environment and research and innovation.

15

One important condition for a high growth rate is to increase understanding and dialogue between different parts of society. The best conditions for growth are achieved in a climate of understanding.

The prospects for growth and renewal in Sweden must be further reinforced during this term of office. Cooperation between the business sector, higher education and society will be stimulated at national and regional level. Entrepreneurship will be facilitated. Enterprise will be given better operating conditions. The flow of knowledge from research and development to the business sector will be eased. Sweden's research strengths and profile areas must be kept up and further developed. All of this presupposes close interplay between many policy areas.

1.5.1 Full employment

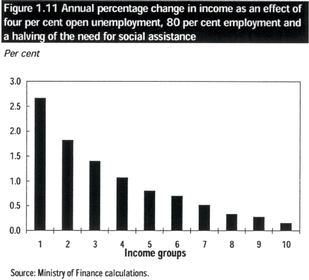

Full employment is at the top of the Government's agenda. A high employment rate and low unemployment are the cornerstones of welfare. The keys to enhancing social justice and gender equality are a high growth rate, rising numbers of people in work and fewer and fewer jobless. These conditions lead to increased resources, making it possible to extend welfare, step by step. In the autumn of 1998, the Government and Riksdag set the interim target that the proportion of the population aged 20-64 in regular employment should increase from 73.9 per cent in 1997 to 80 per cent in 2004.

In terms of both GDP growth and the number of people employed, developments have been more favourable since 1998 than was assumed when the employment target was set. The Government's assessment in 1998 was that annual growth of 2.75 per cent was needed, and that the number of people aged 20-64 in regular employment needed to increase by 1.3 per cent each year in order to reach the target of 80 per cent regular employment. These levels have been surpassed. From 1998 to 2002, GDP growth has averaged 3.1 per cent per year and regular employment in the 20-64 age group has increased by an average of 1.5 per cent per year.

16

In spite of the favourable trend, the chances of reaching the employment goal in 2004 have declined. Regular employment is forecast at 77.6 per cent in 2004. One major explanation lies in the repercussions of the weakened international economy in Sweden. Other factors include the rise in the number of students and the increase in net immigration since the target was set.

Efforts to reach the employment goal are continuing. The Government is now proposing a range of measures to promote increased employment and to give all groups better opportunities on the labour market. Efforts are focusing on the following groups:

Youth: At the beginning of the 1990s, 80 per cent of young people aged 20-24 were employed. The corresponding figure today is 60 per cent. The difference is largely due to the fact that more young people are continuing their education to higher levels, but the desire of young people to work and to combine work and studies needs to be harnessed more adequately.

- •

- Increase knowledge about the results and impact of programmes of higher education

Impact analyses give prospective students information about the effect different programmes of higher education have on employability. The Government intends to instruct the National Agency for Higher Education to conduct impact studies and to follow up and analyse the extent to which individuals subsequently become established on the labour market.

- •

- Review the possibilities of granting credit for previous courses at university level

Sweden has ratified the Lisbon Convention, which means students are entitled to credit for courses taken previously as long as there are no substantial differences between the programmes involved. The Government intends to commission the National Agency for Higher Education to review procedures for granting credit for previous studies and to propose measures to facilitate this process.

- •

- Speedier transition from upper secondary to higher education

In labour market terms, it is desirable for more young people to get out onto the market more quickly, assuming there is no concomitant loss of quality. Those who apply to university should be offered a place and complete their educational programme as soon as possible. The Government has appointed a special expert to examine ways of modifying university selection rules and admission procedures so as to reduce incentives for prospective students to take municipal adult education courses to obtain more competitive upper secondary grades.

17

Among adults studying at compulsory school and upper secondary school levels, there are two groups who are eligible for the higher study grant of 82 per cent in the study support system: students who lack leaving certificates from compulsory or three-year upper secondary school, and students repeating or supplementing subjects taken at these levels. The Government proposes that as from 2004, students who have completed three-year upper secondary education should no longer be eligible for the higher grant for refresher courses and supplementary courses at upper secondary level.

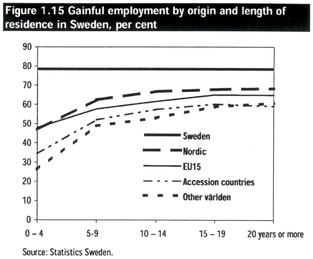

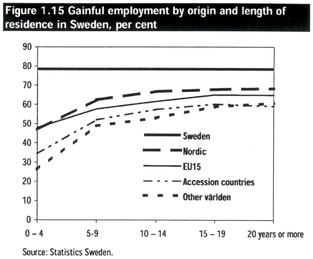

Immigrants: Immigrants represent a great potential resource that Sweden must use better. Between 1997 and 2002, the employment rate has risen more rapidly for immigrants than for people born in Sweden. Nevertheless, the gap in employment level between immigrants and native Swedes remains broad. In the 16-64 age group, the employment rate for people born outside Europe was barely 54 per cent in 2002, as against nearly 77 per cent for native Swedes.

- •

- Improved valuation of qualifications

Acknowledgement of previously acquired knowledge and abilities, whether formal or informal, leads to increased employability and better labour market matching. An improved validation system is important, not least to make it easier for immigrants to enter the labour market. The Government intends later to announce proposals for a temporary central government initiative to stimulate the development of effective and appropriate validation systems.

- •

- Workplace experience to facilitate language learning

The chances of newly arrived immigrants mastering the Swedish language and obtaining work increase if language teaching is integrated with working life. Work experience opportunities build contacts in working life, provide work training and increase employability. In 2004, the Government intends to propose measures aimed at improving the integration of language learning and workplace experience.

- •

- More effective Swedish instruction

Knowledge of the Swedish language is important if people born outside Sweden are to establish themselves on the labour market and participate in society. There is considerable variation between education providers in terms of educational quality and student throughput. In 2004 the Government intends to propose a reform of Swedish language instruction for immigrants. Such instruction will be regularly linked to studies in the local authority adult education system or higher education, work experience, employment or other activities.

The unemployed: The successful policies of recent years have kept unemployment steady at about four per cent despite the international economic slowdown. Nevertheless, 41 000 individuals were still enrolled long-term at employment offices in 2002. Most of these are participating in the activity guarantee programme.

- •

- Give priority to individuals furthest from the labour market

Recruitment incentives are an effective tool for bringing individuals into the labour market. Yet they also risk crowding out other jobseekers. The efficiency and legitimacy of recruitment incentives are affected by the number of recipients and by targeting the groups that are most removed from the labour market. The Government intends to review the recruitment incentives to enhance their efficiency and to give priority to those who have greatest difficulty in obtaining regular employment.

- •

- Shortening periods of unemployment

Continued efforts are being made to consolidate the effects of changes in the unemployment insurance regulations. The Government intends to take several steps to make the application and supervision of the regulations affecting jobseekers entitled to unemployment benefits more effective. For example, the management of labour market policy will be improved, differences in the results achieved by the different regional divisions of the Swedish National Labour Market

18

The elderly: The proportion of elderly people in the population is growing. The 60-64 age bracket is the group that will experience most population growth in the near future. This is an age group that has a considerably lower employment rate than the average in the population as a whole.

- •

- Making it easier for elderly people to work

It has become apparent that a relatively large number of employers rarely or never recruit elderly people. The attitude of employers towards elderly employees is one of the reasons why it is difficult for elderly people who have left working life to re-enter the labour market. The Government is considering further measures.

The sick: The Government's objectives for sickness absence are designed to reduce individual suffering, give more people a chance to support themselves by their own work and bring down the costs to society. A lower incidence of sick leave and sickness compensation is also a prerequisite for high levels of employment. Each individual receiving sickness or activity compensation who returns to work represents a victory. In order to achieve high employment levels long-term, sick leave must diminish.

- •

- Reducing the number of people receiving sickness or activity compensation by making it easier to change jobs

Mobility in general leads to a more efficient labour market. The Government intends to analyse different factors that can generate locking-in effects. The purpose is to identify measures that will prevent working-age individuals disappearing from employment and the labour market, for example by being granted sickness or activity compensation. Such measures should be able to help ensure that fewer elderly employees leave working life prematurely.

- •

- Recruitment incentives for individuals on long-term sick leave

A form of recruitment subsidy will be introduced to make it easier for individuals on long-term sick leave to begin working again by moving to another employer. The National Labour Market Board will be given the task of administering the subsidy, which is forecast to cover an average of 3 000 individuals.

The Government's approach to the issue of working hours is based on the belief that it is desirable to reduce working hours and to increase the influence individual workers exercise over the organisation of their time at work.

19

Additional measures

The interim target of an 80 per cent employment rate remains firmly in place. In the light of the weak international situation, additional measures will be required to reach the target. The Government intends to propose further measures later, in the 2004 Budget Bill.

Strong, vigorous enterprises

Strong, vigorous enterprises are crucial if Sweden is to be distinguished by sustained growth and social justice.

The Government has set aside funds for a national programme to promote entrepreneurship. The aim is to create a better entrepreneurial climate, foster positive attitudes towards entrepreneurial and business operations and boost entrepreneurial activity.

To enhance growth, the Government is preparing a number of proposals aimed at facilitating the establishment of more and growing companies. The idea is to boost the supply of capital at an early phase of development. It must become easier to start and run a business.

The amount of information small enterprises are required to submit to authorities will be cut during this Government's term of office, as will the number of occasions involved. The Government intends to formulate measurable targets for reducing the administrative burden and to give SimpLex (the Government Offices department responsible for regulatory simplification) the resources to scrutinise existing legislation.

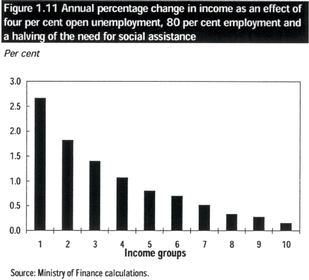

1.5.2 Halving the need for social assistance

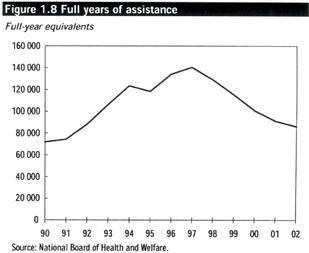

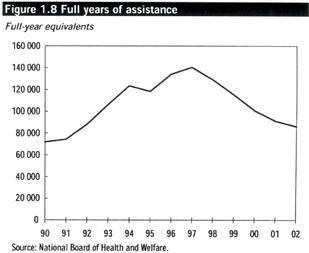

The need for social assistance is an expression of economic and social disparities. It leads to a lack of economic independence and to economic vulnerability. In the 2001 Spring Fiscal Policy Bill, the Government set the target of halving the need for social assistance. This means halving the number of full years of social assistance from 115 200 in 1999 to 57 600 in 2004.

Between 1999 and 2001 the number of full years of social assistance fell by 24 000, i.e. by 21 per cent. The cost trend for 2002 indicates a continued, albeit slower, decline.

The projections in the 2003 Budget Bill show that reaching the employment target is a necessary, but not sufficient, condition for meeting the social assistance target. The poorer economic climate is affecting Sweden and having adverse effects on employment, which will make it more difficult to meet the social assistance target. However, if the favourable employment trend for immigrants in recent years continues, the chances of success will grow. Moreover, the Government's measures to promote increased employment will have a positive impact on the prospects of reaching the social assistance target. The Government remains committed to the objective of halving the need for social assistance.

20

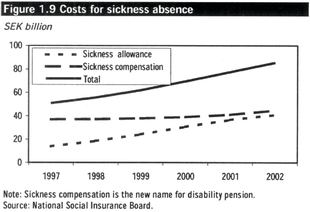

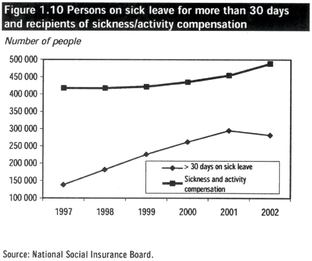

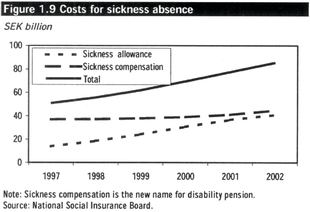

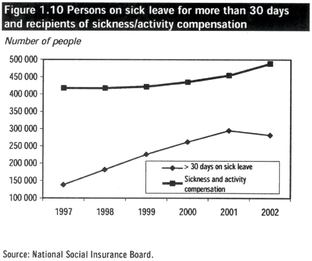

1.5.3 Reducing sick leave

Sickness absence is a human problem above all. But it also has economic consequences. In the last few years the costs of sickness absence have shot up. Recently the number of days of sickness allowance claimed has stopped increasing and the Government expects it to decline in the course of the year. The number of people on long-term sick leave, however, remains persistently high. In both the public and the private sector, women specifically are heavily overrepresented among those on long-term sick leave. This trend has entailed suffering for individuals, difficulties for employers and a heavy burden on the social insurance systems. If the trend is not broken, important welfare initiatives will have to be sidelined.

Sickness absence has many causes: an ageing labour force, a lack of incentives for employers, the health services and people on sick leave, a more demanding working life, a worse psychosocial working environment, deficiencies in the rehabilitation programmes set up by the social insurance offices and employers, waiting times for health and medical care, changes in the attitudes towards sick leave, etc. In view of the multiple causes, measures are required in a range of areas. Actions against sickness absence must be followed closely and improved on an ongoing basis.

The Government has set the target of halving the number of days of sick leave between 2002 and 2008 and bringing down the number of new activity and sickness allowances (which replace disability pensions and sickness benefits). The Riksdag has endorsed this target.

The Government inaugurated a major concerted effort in the autumn of 2001, when an 11-point programme was presented in conjunction with the 2002 Budget Bill. One component has been to invest SEK 70 million in pilot projects to promote better health in the public sector. These trials will now be followed up and evaluated, and the experience gained will be disseminated. Extra resources worth a total of SEK 3.75 billion will be committed over the period 2002 to 2004 to increase the availability of health care. A series of measures were presented in last year's Budget Bill, within the framework of an overall strategy. The social insurance offices, for example, received augmented financial resources to enable them to manage their work. The Riksdag has decided that compulsory reporting of sickness absence will be introduced in annual reports, a decision that will enter into force on 1 July 2003. A proposal has been drawn up for an inquiry into financial coordination. The three-way talks between the Government, employers and trade union organisations have concluded and the chairman has delivered his final report.

The Government is now taking a further step and proposing additional initiatives. In a special bill (Gov. bill 2002/03:89), the Government has described proposals for changes in sickness insurance for the sake of better health in working life. Sick leave will be made a more accurate system, by avoiding

21

full-time sick leave, introducing coordination meetings between the insured individual and the affected parties, improving the information on which decisions are based, enhancing training in insurance medicine and increasing the number of insurance medicine doctors and modifying their role. The employer's rehabilitation report will be made compulsory and the period during which a person is entitled to hold a sickness or activity compensation award dormant will be extended from one to two years.

The Government proposes extending the period during which sick pay is payable by 7 days to a total of 21 days, as from 1 July this year. At the same time, a cost limiting mechanism is proposed for small enterprises.

The procedure for calculating the amount of compensation paid in the form of sickness allowance in the event of sick leave will be changed as from 1 July 2003. The compensation will be cut back by reducing the base for calculating sickness allowances. This reduction will apply to sickness allowance only.

The initial no-benefit day should apply equally to all, irrespective of the timing of sickness notification. The Government will therefore examine the application of the no-benefit day and propose any changes that are required.

The Government proposes further that the sickness allowance paid to unemployed individuals should be adjusted from1 July this year so as not to exceed their unemployment compensation. At present, an unemployed person who is put on sick leave normally receives higher compensation. All those who are employed receive less when they are on sick leave and it is only reasonable that people who are unemployed should not receive a raise in compensation when they are put on sick leave.

Many people on long-term sick leave have jobs to which they cannot return. To make it easier for these individuals to return to work, a form of recruitment incentive is being set up—a temporary subsidy of the wages paid to individuals on long-term sick leave who obtain work with another employer. This support will apply to cases of long-term sick leave where the responsibility for rehabilitation has been transferred from the individual's employer to the social insurance office. The National Labour Market Board will be given the task of administering the subsidy, which is forecast to cover an average of 3 000 individuals. Cooperation will be needed between the social insurance office and the labour market authority to identify individuals who may be relevant.

In its bill on Changes in sickness insurance for better health in working life (Gov. bill 2002/03:89), the Government has proposed that no later than one year after the date of sickness notification, the social insurance offices shall have investigated the possibilities of giving the insured person sickness compensation or activity compensation instead of sickness allowance. The Government will monitor the effects of this change. However, the proposal will not affect people who have already been on sick leave for more than a year. Since the size of this group varies greatly from one county to another, the Government will also instruct the National Social Insurance Board and the social insurance offices to make their working procedures more uniform.

The previously announced raising of the sickness insurance ceiling from 7.5 to 10 price base amounts will be postponed to a later date.

22

While the Government is seeking comprehensive solutions, measures against ill health cannot be delayed. The measures proposed now are simply a first step.

Additional measures

The measures that have already been implemented and those that are now proposed are necessary to meet the target of halving the number of days of sick leave. But this is an ambitious target and additional steps will be required. The three-way talks have delivered proposals in the shape of a programme. As efforts continue, the social partners will bear a considerable responsibility. The steps that need to be taken will depend on various factors, including the impact of the measures already adopted and announced. The Government intends to return to a number of issues in the 2004 Budget Bill.

- —

- More vigorous preventive efforts

In the 2003 Budget Bill, the Government has emphasised the need to improve preventive efforts and rehabilitation. Further development of efforts in the workplace, in cooperation between employers and employees, is fundamental to continued endeavours to promote better health in working life. Measures have been announced relating to the development and augmenting of preventive action. These measures concern occupational health services and inspections in the working environment area.

23

- —

- Increased responsibility for those on sick leave to actively assist in breaking out of sick leave

The responsibility for facilitating a return to work also lies in part with the individual. At present it very seldom happens that compensation is suspended or reduced when a person refrains from participating in rehabilitation or in some other way obstructs a return to work. One reason for this is that the social insurance offices have limited powers to act. Consequently, the Government intends to consider whether the regulations and their application should be made more rigorous.

- —

- Sickness compensation for a maximum of three years at a time

This proposed change was announced in the 2003 Budget Bill, but the labour law consequences need further analysis before a proposal can be put forward. The Government intends to make a proposal in this area at a later date.

- —

- Stronger economic incentives to employers to reduce ill health

As early as the 11-point programme presented in connection with the Budget Bill in the autumn of 2001, the Government indicated that it intended to bring in augmented economic incentives of some type to encourage employers to tackle the problem of increased ill health in working life. Within the framework of the three-way talks, a model has also been proposed that places an increased responsibility for costs on employers, even in cases of relatively long-term sick leave. The Swedish Trade Union Confederation, the Confederation of Professional Employees and the Swedish Confederation of Professional Associations (SACO) have also proposed a similar model with an increased responsibility for costs. Employers will also face higher costs if they fail to provide rehabilitation plans.

At present employers have considerable costs in connection with absences of short and medium duration; there are costs for sick pay, costs for replacement personnel and overtime, and not least costs in the form of disturbances of production. But the longer a person is on sick leave, the more the costs to the individual employer tend to disappear. The person who is sick is not infrequently replaced by a substitute who, as time goes by, does the job equally well. The employer then has nothing to gain economically from getting the sick employee back, especially if he or she returns with a lower capacity for work. To increase the employer's motivation to get staff back to work, the Government therefore wishes to introduce economic incentives.

Proposals on the detailed design of a system of economic incentives will be presented in connection with the 2004 Budget Bill. The planned starting date for the system is 1 January 2004. The following pointers can already be noted:

- —

- The system will encompass the entire labour market and will be designed to strengthen both individuals and enterprise—and hence also the general economy—in a long-term perspective.

- —

- Employers will pay part of the compensation even after the period of sick pay.

- —

- The design of the economic incentives will entail that steps leading to less ill health and lower sickness allowance costs will lower employers' costs.

- —

- When designing a system incorporating increased responsibility for costs, the current arrangements in the collective agreements on the labour market must be taken into account.

- —

- It is proposed that a mechanism to protect small enterprises in connection with the proposed lengthening of the period of sick pay to 21 days should already be introduced this year. This mechanism will be designed to prevent increased responsibility for costs after the period of sick pay inhibiting growth. Threshold effects should be minimised and

24

1.6 Reforms to promote justice and security

Welfare will continue to be extended at the rate the economy allows. An extensive system of welfare that provides security in the midst of change makes the economy more dynamic. Secure people can be more daring.

A range of reforms are being implemented this year to enhance social justice. These reforms will give higher pensions, more teachers in schools, more places in higher education, improved study grants, universal pre-school, more international development assistance and more money for health and social services.

In spite of the savings and expenditure cuts that are now proposed, a number of reforms will be carried out in 2004 as well. There will be further investments to put more teachers and specialist staff in schools, measures to support health care and medical services, environmental and infrastructure investments and a further increase in development assistance to 0.868 per cent of GNI, which will mean a rise of SEK 2 887 million to SEK 21 833 million.

Table 1.10 Approved and announced reforms

Impact on the budget compared with previous year

SEK billion

| | 2003

| | 2004

|

|---|

| Justice | | 0.20 | | 0.40 |

| International development cooperation | | 1.64 | | 1.46 |

| Health and medical care, schools and community services | | 6.24 | | 2.80 |

| Pensions, etc. | | 2.80 | | 0.00 |

| Extra month for mother/father | | 0.50 | | 0.50 |

| Labour market | | 1.70 | | 0.00 |

| Education and research | | 2.10 | | 0.76 |

| Housing | | 0.35 | | 0.12 |

| Infrastructure | | 1.20 | | 2.10 |

| Other expenditure reforms | | 2.68 | | 1.40 |

| | |

| |

|

| Expenditure reforms, total | | 19.40 | | 9.54 |

| | |

| |

|

1.6.1 Children and the young—Sweden's future

The system of maximum charges has given families with children substantially lower fees for childcare. Special resources will be committed in future as well to recruit extra staff so as to safeguard the quality of operations. The first follow-up of the maximum charges reform, conducted by the National Agency for Education, indicates that the Government's aims have been fulfilled. Standards have been maintained. More children are attending preschool, but the increase in the number of children has not affected the size of groups or the amount of time children spend at pre-school. There has been no negative impact on staffing ratios either. On 1 January this year universal pre-school was introduced for all children aged four or five. This means all children are entitled to three hours of

25

pre-school per day, free of charge. As part of the expenditure cuts announced in this bill, the Government proposes a rise in the ceiling for maximum childcare charges in 2004.

Parental insurance will be enhanced. The one-month extension of parental insurance will take effect this year. At the same time, the minimum daily allowance will be raised to SEK 150 per day and a further increase to SEK 180 per day is planned for 2004. When the economic situation permits, the Government intends to go further and enhance parental insurance additionally by raising the income ceiling in the system.

The upper secondary study grant has been extended from 9 to 10 months of the year. This will mean an extra SEK 950 per year for families with a teenager at upper secondary school.

Table 1.11 Investments in schools and pre-school

SEK billion

| | 2002

| | 2003

| | 2004

|

|---|

| Maximum charges | | 3.9 | | 3.9 | | 3.7 |

| Right for children of jobseekers or parents on parental leave to attend pre-school | | 0.5 | | 0.5 | | 0.5 |

| Universal pre-school for 4-5- year-olds | | | | 1.2 | | 1.2 |

| Extra staff in schools and after school centres | | 1.5 | | 2.5 | | 3.5 |

| | |

| |

| |

|

| Total | | 5.9 | | 8.1 | | 8.9 |

| | |

| |

| |

|

1.6.2 Security for the elderly

The elderly have a right to grow old in security. A welfare society like Sweden should be distinguished by solidarity between women and men, individuals, groups and generations. During the Government's previous term of office, a series of important reforms were carried out. Pensions and housing supplements were raised repeatedly, while taxes on pensioners went down. A maximum charge was introduced in elder care, together with a minimum guaranteed income after charges, and a new and better system to protect against high costs was implemented in dental care for the elderly.

Further steps have been taken this year in strengthening intergenerational solidarity and enhancing security for the elderly.

Pensions have been raised by between SEK 300 and SEK 600 a month for those with the lowest pensions. Another SEK 300 million are being committed this year as part of the process of improving dental care support for the elderly. A new form of maintenance support for elderly persons has been brought in to guarantee all people in Sweden over the age of 65 a reasonable standard of living. This reduces the need of the elderly for social allowances.

1.6.3 Standards will be kept up in health care and social services

Health and medical care, schools and community services are at the very heart of social welfare. Availability must be determined by need, not by private economic circumstances or where in the country a person lives. Health and medical care, schools and community services must therefore be universal, cover the whole population and maintain high standards.

Local authorities have recently enjoyed good income growth. Rising employment levels and higher government grants have led to increased revenues. Now times have changed. The weakness of the international economy and the prevailing uncertainty are affecting the Swedish economy and the weaker income growth has repercussions for Swedish local authorities.

26

In order to develop welfare and continue to meet commitments in future, employment levels must go up. To strengthen the position of local authorities in the short term, the temporary employment support provided in 2002 has been extended to apply in 2003 as well. The Government now proposes to augment the employment support in 2003 and to continue such support in 2004. The fixed sum of SEK 200 that all income earners pay in state income tax will accrue to the local authorities this year. The Government proposes that these tax resources should also go to municipalities and county councils in 2004. These changes will entail a boost for local authorities totalling SEK 0.3 billion in 2003 and SEK 4.3 billion in 2004.

The special health care initiative earlier approved by the Riksdag provides additional resources of SEK 9 billion over the period 2001-2004. These funds have been made available largely by adjustments in total defence priorities. In addition, SEK 3.75 billion is being committed in 2002-2004 to reduce waiting times in the health service.

Table 1.12 Commitments to health care

SEK billion

| | 2002

| | 2003

| | 2004

|

|---|

| Health care | | 1 | | 3 | | 4 |

| Shorter waiting lists | | 1.25 | | 1.25 | | 1.25 |

| | |

| |

| |

|

| Total | | 2.25 | | 4.25 | | 5.25 |

| | |

| |

| |

|

1.6.4 Sweden—a knowledge society

Knowledge is a powerful tool for economic growth and social justice. Education is essential for equality and development. This being so, major initiatives are under way in compulsory school, upper secondary school, adult education and higher education.

Over the next few years, up to 2006, schools and after school centres will receive SEK 1 billion per year. This means raising the total level of resources by SEK 5 billion. The resources are to be used to employ more school staff, e.g. teachers, school nurses, remedial teachers, school librarians and other specialist staff.

A special initiative for higher education is also in progress. The Government's long-term goal is that at least half the young people born in any year shall have embarked on university-level studies by the age of 25. Resources have been allocated corresponding to an expansion by nearly 100 000 student places between 1997 and 2003.

On 1 January this year a specific government grant for adult education was launched. At the same time, a form of special adult study support known as an education recruitment grant has been introduced, for use by municipalities in recruiting adults over the age of 25 who have limited previous education, are unemployed or at risk of unemployment or have some type of disability.

In order to make it more possible for higher education institutions to incorporate both breadth and specialisation in the research they pursue, government appropriations for research and postgraduate education will increase by SEK 1.5 billion between 2000 and 2004.

As part of the green tax shift, money has been set aside for individual learning and skills development. This matter is currently under preparation at the Government Offices. The Government intends to put forward proposals on learning and skills development later in this term of office.

27

1.6.5 Good housing for all

The objective of housing policy is good housing for all people at reasonable prices. Housing is an integral part of welfare.

The Swedish housing market is polarised. In many municipalities the population is declining. A large proportion of the existing dwellings are unoccupied, particularly accommodation owned by the municipal housing companies. On 1 August 2002, the Government established the National Public Housing Board to help municipalities and municipal housing companies to restructure their property holdings.

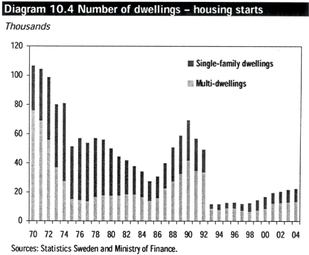

In growth regions, the situation is the reverse. Population increase is generating higher demand, while housing construction has been low over the last ten years. In 2001 a special investment grant was introduced to encourage the production of new small and medium-sized rental dwellings in growth regions. The Government has recently proposed further incentives to increase the production of small rental units and student accommodation (Gov. bill 2002/03:98).

New housing must be built at reasonable cost. To achieve this, competition in the building sector must also improve. Further action is required to produce good indoor environments.

1.6.6 Challenges for social policy

Much remains to be done in the social domain, and in some respects things are still moving in the wrong direction. This is the case, for example, with drug abuse and alcohol consumption. Drink and drug abuse are often the key to other social problems, e.g. crime, homelessness and prostitution.

SEK 550 million has been set aside for the action plan on alcohol policy in the period 2001-2003, for use in improving and expanding local preventive measures, conducting a broad information campaign and other activities. The aim is to reduce alcohol abuse, delay young people's alcohol debut and bring down total consumption.

The action plan on drug policy includes initiatives to reduce new recruitment to drug abuse, induce more addicts to stop using drugs and reduce the availability of drugs. A total of SEK 325 million is being committed to this between 2002 and 2004. SEK 100 million of this has been allocated to the prison and probation services for use in preventing and combating drug abuse in prisons and helping more inmates overcome their addiction. This bill announces more resources for the prison and probation services, which will also be significant for the campaign against drugs.

The Government intends to continue to take initiatives during this term of office to improve preventive activities in the area of alcohol and drugs, to enhance the care available to addicts and to reduce homelessness.

The appropriation to the Swedish Police will be augmented in 2004 and subsequently so as to increase the number of police officers and permit operational development. The Government will specify the levels in the Budget Bill for 2004.

1.6.7 Balanced regional development

In its development, society must aim to use and develop the resources of the entire country. All parts of the country must be able to contribute to Sweden's growth. Sweden needs cohesion—both among its people and between and within its regions.

Sweden, with its great distances, needs a well developed infrastructure. The tax equalisation system will be further developed. Cooperation creates the best conditions for growth. Regional growth programmes will be developed and implemented in agreement and dialogue between different parts of society.

28

1.7 Fair taxes

The prime purpose of taxation is to finance social welfare. Taxation policies must simultaneously encourage work and investment, stimulate sustainable growth and help to close economic and social gaps. The Government can never accept large tax cuts for those members of society who are already well off, at the expense of health care, schools and community services.

Proceeding from this basic outlook, the Government will give priority to further improvements for employees and small enterprises. At present there is no scope for unfinanced tax cuts.

During the coming year, taxation policy will focus on four areas.

1.7.1 Globalisation and the structure of Swedish taxation

The continuing process of globalisation presents a range of challenges to the Swedish tax system. At the end of 2002, the Tax Base Commission delivered its final report. The report has been circulated to a wide range of bodies for comment by the summer of 2003.

One of the main messages from the Tax Base Commission is that while the present level of taxation can be maintained, this will only be possible if we look after the tax system and tax bases. Countries with high levels of public spending require broad tax bases and need to limit various types of special regulations. This is essential to minimise marginal taxes in certain strategic areas.

1.7.2 Small enterprises

The Government strives as far as possible to create consistent and straightforward tax regulations for different forms of small enterprises and their owners. One of the benefits of such regulations is to facilitate the transitions between different corporate forms that often naturally accompany operational development.

In June 2002 the 3:12 Commission delivered its report Taxation of small entrepreneurs (Swedish Government Official Reports 2002:52). The Commission proposes amendments in the basic regulations governing the taxation of income from small limited companies, as well as relief in the form of lighter inheritance taxation in connection with generational handovers and gifts. The report has been circulated for comment and the proposals are now being processed at the Government Offices. The Government wants to change the 3:12 rules to make them more favourable to entrepreneurs.

Last year the Committee for Simplification of Taxation Rules for Small Enterprises presented its final report, which included a proposal on a reform of tax regulations for partnerships. The report has been circulated for comment and the Government will take a position on the Committee's proposal in conjunction with the continuing work on tax regulations for small enterprises.

1.7.3 Action against tax evasion

Tax evasion distorts competition in the economy, impairs the legitimacy of the tax system and ultimately represents a threat to welfare. The Government continues to give priority to the fight against tax evasion and economic crime.

The Swedish Tax Administration was allocated a total of SEK 300 million in 2001 and 2002 for tougher tax enforcement. As a result more and more criminal investigations have been brought to a conclusion and an increasing number of tax offences have been reported to the prosecution authorities. Efforts to make tax control more effective are also under way at the National Tax Board. The Government has recently submitted a bill containing proposals for reforming the organisation of the Swedish Tax Administration and enhancing its efficiency and effectiveness. The bill proposes replacing the present organisation by a national authority, the Tax Board.

29

Over and above organisational changes and measures to improve control, changes are required in the tax legislation to prevent tax evasion and avoidance.

In its report Pull your socks up, lads! (Swedish Government Official Reports 2002:115), for example, the National Commission on Construction proposes the establishment of special contract accounts and "reversed" VAT liability for general contractors, as measures to combat unregistered labour in the construction sector. These proposals are currently being processed by the Government Offices and will be evaluated after comments from referral bodies.

In the course of the spring, the Government will take a position on standard taxation in certain industries, as proposed in the National Tax Board report Standard taxation: a basic outline (National Tax Board Report 2002:3).