QuickLinks -- Click here to rapidly navigate through this documentEXHIBIT 99.C

1

The revised

Budget Statement

PROP. 2000/2001:1

1 The revised Budget Statement

1.1 A reform budget

The budget for 2001 is a budget for the future.

The foundation for an active, future oriented policy is a strong economy. Economic policy therefore aims to support and prolong the good economic development of recent years. This involves prioritising growth and social justice while at the same time reducing the burden of debt for future generations.

Children are at the centre of policy. The Swedish school system is to be one of the best in the world. Investing more money in education is a good, sustainable investment in the future. Welfare policy is driving Sweden forward. There is now scope for welfare reforms and tax cuts with our own money, while paying off public debt at the same time. Sweden shall continue to show that growth and social justice can be combined.

A policy for sustainable high growth

The Swedish economy is developing well. Growth is good. Unemployment is decreasing and employment increasing. The target of reducing open employment to 4 per cent has been practically achieved. Public debt is being reduced at a rapid rate. Sweden has a large, increasing surplus in foreign trade. The Swedish economy has not developed so well and in such a balanced way since the 1960s.

The Government now makes the assessment that the resource use that can be achieved without the risk of overheating is greater than was previously thought possible. The good growth is not only a temporary cyclical upturn but an adaptation to a long-term higher resource use.

In order to prolong the upturn and make it sustainable, the Government proposes to increase repayments on public debt and to reduce taxes for those on low and medium incomes. Furthermore, the reforms for growth and social justice that were proposed in the Spring Fiscal Policy Bill will be realised.

The balance struck between debt repayments, expenditure increases and tax reductions will depend on cyclical and distribution policy considerations. Furthermore, the budget targets must be met. The Swedish economy shall continue to grow without tendencies to overheating appearing.

Research, technical leading-edge competence and broad participation contribute to the ability of the Swedish economy to grow at a high rate without imbalances arising. Sweden shall retain its world-leading position in strategically important areas such as information technology, telecommunications and biotechnology. Distributing licences for the new generation of mobile telephones without high fees to those companies that have the best abilities to contribute to this development is a part of this strategy. The Government intends to work for Sweden to retain its leadership also in biotechnology.

A policy for strong public finances

Good social welfare requires strong public finances.

The goal for public finances is that they should generate a surplus of 2 per cent of GDP on average over a business cycle. This target is to be upheld. Thereby, a more stable basis is created for the challenges that come with the great increase in the proportion of elderly people in the next decade.

2

Targets for each year are then set on the basis of the long-term target. In conjunction with the Budget Bill, the Government proposes a target for public finances for the coming year. This target is set on the basis of the contemporary assessment of the state of the economy. In accordance with this, the Government is now proposing that the target for surplus in public finances be increased from 2 to 2.5 per cent of GDP to reduce the risk of overheating.

The expenditure ceilings are to be upheld. A responsible budget policy lays the basis for continued strong economic growth. The expenditure ceilings in relation to GDP will fall until 2002 and stabilise thereafter. Despite this, there is scope for reforms since the expenditure ceilings are increasing in real terms.

A policy for welfare

Universal, publicly financed welfare is required to achieve the goal of a fair society with equality of opportunity.

The reforms that have previously been presented are now being carried out. Resources for education, health care and social services are being increased. Child allowances are being increased and additional resources are being made available for the worst-off pensioners. The first step is being taken in the maximum childcare charge reform. The offensive for growth, equality of opportunity, social justice and full employment is to be accomplished.

However, further steps must be taken to strengthen welfare. In the same way as an additional SEK 9 billion is to be made available to health care in the next few years, a long-term investment in education is now proposed. The vision is a society where all children are treated fairly and get a good start in life.

To make it possible for more children to meet the objectives, additional resources are required, particularly for pupils with special needs. The Government therefore proposes a substantial increase in resources for schools and recreation centres for schoolchildren.

During the coming years, resources for education are to be increased by SEK 1 billion per year. From 2006, an additional SEK 5 billion is to be made available compared with today. More adults in school contribute to creating a better school. The Government is also proposing to reintroduce contact days in the temporary parental benefit next year. This will improve the opportunities for women and men to take an active part in their child's everyday life at school.

The Government is also proposing additional resources in other areas of welfare. In addition to the extra resources previously proposed, the Government is proposing that an additional SEK 100 million be made available for dental care next year. An improvement is also proposed of the special housing supplement for pensioners, which will benefit the worst-off pensioners.

A policy for work

High employment is the foundation for welfare.

In connection with the Spring Fiscal Policy Bill, the Government proposed an offensive for growth and social justice. This offensive is focused on work and is now being carried out with full force.

Measures are taken to further press down unemployment. The target of reducing open unemployment to 4 per in 2000 has practically been achieved.

Measures are taken to increase employment and growth. The goal that at least 80 per cent of the population aged between 20 and 64 shall be in regular employment is to be achieved by 2004.

3

Measures are taken to increase the participation of immigrants in the labour force. It is a waste of resources that people with an immigrant background have higher unemployment and a lower employment ratio than other Swedes.

There is a trend towards an increase in ill health. This is serious from a human as well as an economic perspective. The Government has therefore appointed a working group to produce an action plan to reduce ill health. This work includes a review of sickness benefit, rehabilitation allowance, the supervision of the working environment and disability pension. It is of the greatest importance that working conditions and the work environment do not give rise to ill health and occupational injuries. Preventive work shall therefore be prioritised. Active steps are to be taken to enable those on sick leave and on disability pensions to return to a working life that does not give rise to injuries and illnesses or wear people out.

A policy for growth in the whole of Sweden

The overall design of economic and business policy is very important for ensuring a high sustainable rate of growth throughout the country. During the last few years, the Government has introduced a number of initiatives in the area of business policy aiming to promote growth.

- •

- Proposals are included in the IT bill submitted to the Riksdag to enable support to be provided for expansion of the IT infrastructure.

- •

- A well-functioning infrastructure is of crucial importance for the Swedish business sector to develop well. The Budget Bill gives priority to investments that increase maintenance, the bearing capacity and the reconstruction of roads and railways. Moreover, special funds are being made available for initiatives for flood-damaged roads.

- •

- In order to stimulate the business climate and create good conditions for new establishment of businesses, and to enable existing businesses to expand, work must be continued with respect to supply of capital, simplification of rules, information, service and advice, skills, effective competition and transfer of knowledge.

- •

- The approach in regional policy is to create the prerequisites for sustainable economic growth, social justice and freedom of choice, so that uniform conditions of life are created for citizens throughout Sweden. A regional policy commission is at present working on producing a strategy for regional balance. The Government intends to submit further proposals to the Riksdag when the commission has made its final report.

A policy for fair taxes and a good environment

The strong public finances have made tax cuts possible this year which both stimulate growth and increase social justice. The Government now makes the assessment that there is scope for further tax cuts mainly focused on those on low and medium incomes.

The Government is proposing compensation for a further quarter of the employee contributions paid by wage earners to the pension system. Wage earners will thus be compensated for half of the employee contributions they pay.

4

Table 1.1 Proposals in the Spring Fiscal Policy Bill (SFPB) and the Budget Bill (BB) for 2001

SEK Billion

| | 2001

| | 2002

| | 2003

|

|---|

| Proposals in the SFPB | | | | | | |

| Offensive for growth and social justice | | 1.9 | | 2.2 | | 9.2 |

| Increased social justice and security | | 2.4 | | 3.0 | | 3.4 |

| Children our future | | 0.2 | | 5.4 | | 6.6 |

| An ecologically sustainable Sweden | | 0.6 | | 0.6 | | 2.6 |

| International solidarity | | 0.3 | | 0.3 | | 2.5 |

| Others | | 1.0 | | 0.8 | | 0.8 |

| Less financing | | -1.7 | | -3.4 | | -5.1 |

| | |

| |

| |

|

| Total reforms in SFPB 2000 | | 4.5 | | 8.9 | | 20.0 |

| | |

| |

| |

|

Alcohol preventive measures |

|

0.05 |

|

0.08 |

|

0.10 |

| Dental care | | 0.10 | | | | |

| Guarantee pension | | | | | | 1.00 |

| Contact days r | | 0.06 | | 0.16 | | 0.28 |

| Education | | 0.50 | | 1.50 | | 2.50 |

| Sustainable Sweden | | 0.10 | | 0.12 | | 0.12 |

| Road maintenance | | 0.20 | | | | |

| Other expenditure reforms | | 0.01 | | 0.26 | | 0.53 |

| | |

| |

| |

|

| Total expenditure reforms in BB for 2001 | | 0.97 | | 2.11 | | 4.53 |

| | |

| |

| |

|

1/4 income tax reform |

|

12.50 |

|

13.80 |

|

15.00 |

| Reduced VAT on public transport | | 0.88 | | 0.81 | | 0.81 |

| Increased travel deduction | | 0.00 | | 0.25 | | 0.25 |

| Other | | 0.28 | | 0.29 | | 0.29 |

| Green tax swap | | | | | | |

| | Increased basic deduction | | 2.57 | | 2.80 | | 2.80 |

| | Reduced payroll tax | | 0.47 | | 0.45 | | 0.40 |

| | Increased environmental taxes | | -3.18 | | -2.95 | | -2.84 |

| | |

| |

| |

|

| Total tax cuts in BB for 2001(1) | | 13.52 | | 15.45 | | 16.71 |

| | |

| |

| |

|

- (1)

- Excluding the tax changes proposed to neutralise the effects of increased tax assessment values.

Reporting in the table is made in national accounting terms. This means inter alia that the effects of measures are accrued to the years when payment takes place.

These employee contributions were introduced as a component of the budget consolidation during the 1990s. The improved public finances now make compensation possible. Employee contributions are a heavy burden, particularly for those on low incomes. The Government is also proposing that the threshold for state income tax be increased. Income tax reductions reduce the number of taxpayers who pay state tax to 16 per cent. These measures reduce marginal taxes for those on low and medium incomes and have a positive distribution profile. It is also proposed that the travel deduction be increased to SEK 16 per 10 kilometres. Through these tax cuts, the maximum childcare charge reform, the educational and training initiatives, labour supply can be stimulated.

A green tax swap—increasing tax on environmentally hazardous activities while reducing tax on labour—is part of an ecologically and economically sustainable tax policy.

It is considered that slightly over SEK 3 billion is available for a green tax swap in 2001. The Government is therefore proposing that carbon dioxide tax, diesel tax and electricity tax be increased. These incomes are used to finance a reduction of payroll tax and an increase of the basic deduction by

5

SEK 1,200. The general basic deduction and the special basic deduction for pensioners are both being increased.

A number of other tax changes are proposed in the environmental field. To benefit public transport, it is proposed to halve value-added tax on it. Vehicle tax on older diesel-driven cars is increased while sales tax on motorcycles, light lorries and buses/coaches is abolished. The environmental bonus for windpower is retained.

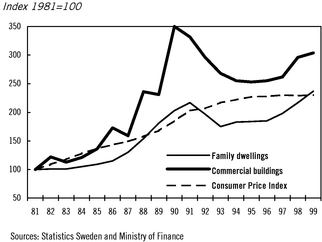

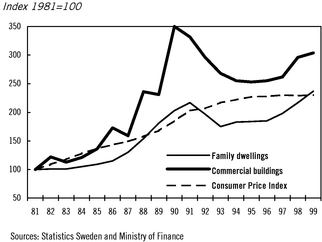

In recent years, property prices have increased in many places in Sweden. In 2001, there will be a great increase in tax assessment values in the areas where prices have increased the most. If no action is taken, this will lead to an increase in central government revenue of around SEK 10 billion next year.

The Government is now proposing that this tax revenue shall be used to reduce the tax rate on houses from 1.5 to 1.2 per cent and on apartment blocks from 1.2 to 0.7 per cent of the tax assessment value. At the same time, the exempted amount in wealth tax is to be increased for single persons to SEK 1 million and to SEK 1.5 million for jointly taxed couples. In order to avoid persons on low incomes paying too large a proportion of their income in property tax, the Government has initiated work aiming at presenting a proposal on a limitation rule in property tax. The Government is also proposing that tax on sale of private houses be raised from 15 to 20 per cent.

A policy for co-operation

The Government aims to create the greatest possible endorsement for a policy of full employment. The social partners in the labour market have an important role in this context. The Budget Bill is based on an agreement between the Social-Democratic government, the Left Party and the Green Party, which support the guidelines of economic policy, the expenditure ceiling, the supplementary budget for 2000, the appropriations for 2001, and the tax changes now proposed.

This co-operation extends to five areas—the economy, employment, social justice, equality of opportunity and the environment—and includes concrete proposals as well as commitments for the future. This co-operation confirms that there is a political majority for an economic policy directed at full employment, a public budget surplus of 2 per cent of GDP on average over the business cycle, and price stability. The policy pursued also aims at equality of opportunity and ecological sustainability.

1.2 The economic situation

The Swedish economy is developing well due to the increasing domestic demand, increased supply and the good international economic trend. Growth is expected to be 3.9 per cent this year and 3.5 per cent next year.

1.2.1 International economic development

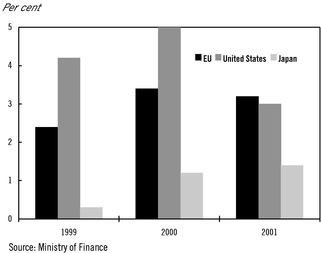

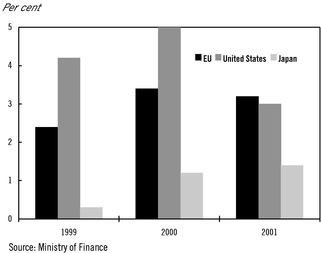

The prospects for the world economy are good. Global growth is expected to be 4.5 per cent this year and 4 per cent next year.

The state of the economy in the EU improves further still and growth is expected to total around 3.5 per cent this year and over 3 per cent next year. Growth is driven by continued strong domestic demand combined with a favourable increase in exports.

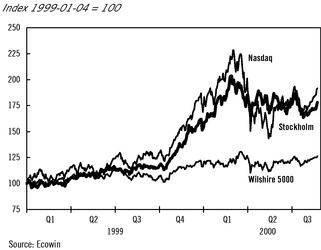

The American economy is developing well. The upturn has now continued without interruption since 1992. This year, continued strong domestic demand is expected to contribute to growth in the American economy being as much as 5 per cent. Next year, growth is expected to fall to approximately 3 per cent.

6

The prospects for the Japanese economy are still uncertain. Domestic demand is weak. However, there are certain positive signs, for example in the form of a relatively strong recovery in industrial production. Growth in the Japanese economy is expected to total over 1 per cent this year and just under 1.5 per cent next year.

1.2.2 Swedish economic development

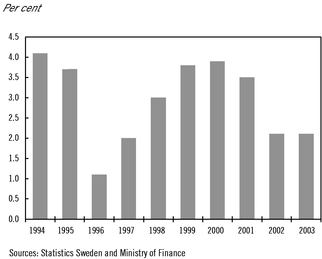

The Swedish economy continues to grow. Between 1997 and 2000, it is estimated that the Swedish economy grew by over 3 per cent per year on average.

The prerequisites for a continued good economic development are favourable. The surpluses in public finances are stable and economic resources are available for increasing welfare, cutting taxes and increasing repayment of the public debt. Despite high growth, price increases are low.

Table 1.2 Demand and output, 1999-2001

| | SEK Billion

| | Percentage change, volume g

|

|---|

| | 1999

| | 2000

| | 2001

|

|---|

| Household consumption expenditure(1) | | 997 | | 3.7 | | 3.4 |

| General government consumption expenditure(1) | | 533 | | 0.6 | | 0.9 |

| Gross fixed capital formation | | 327 | | 5.1 | | 6.8 |

| Stockbuilding(2) | | 6 | | 0.2 | | -0.1 |

| Exports | | 863 | | 9.8 | | 7.7 |

| Imports | | 754 | | 8.8 | | 7.5 |

| GDP | | 1.972 | | 3.9 | | 3.5 |

- (1)

- The statistics for 2000 are affected by the Church of Sweden being included in the household consumption sector from this year. Changes in volume are shown excluding this effect.

- (2)

- Contribution to growth of GDP

Sources: Statistics Sweden and Ministry of Finance

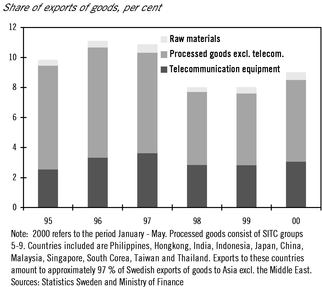

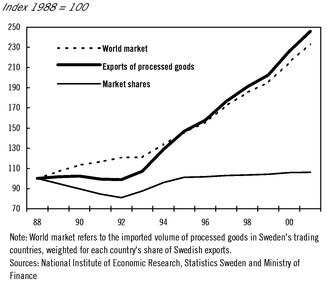

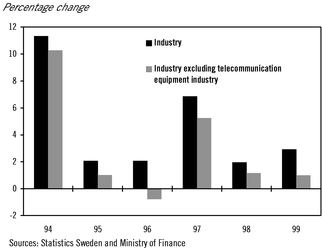

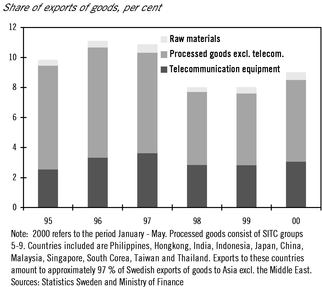

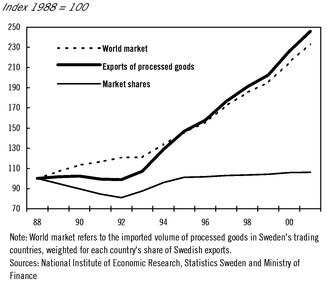

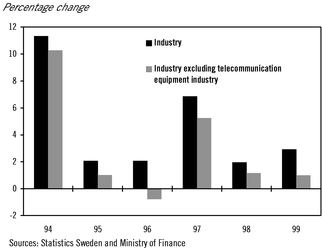

Swedish exports benefit from the rise in the world economy and from the great strength of the Swedish business sector in such areas as telecommunications and information technology. Some capacity restrictions in base industry contribute to the growth of exports being dampened next year compared with this year's very strong increase.

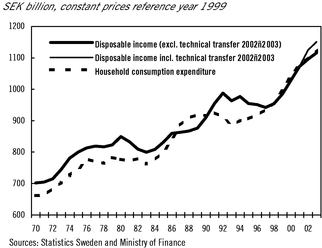

Domestic demand continues to increase strongly. Low inflation and rapidly rising employment leads to a good trend in household income. The tax cuts now proposed strengthen household finances. At the same time, labour supply is stimulated, for instance through reduced marginal effects.

7

Table 1.3 Selected statistics

Annual percentage change unless otherwise stated

| | 1999

| | 2000

| | 2001

|

|---|

| CPI, annual average | | 0.3 | | 1.2 | | 1.4 |

| Hourly wage cost | | 3.4 | | 3.5 | | 3.5 |

| Open unemployment(1) | | 5.6 | | 4.6 | | 3.8 |

| Labour market programme measures(1) | | 3.1 | | 2.6 | | 2.6 |

| Number of employed | | 2.2 | | 2.0 | | 1.3 |

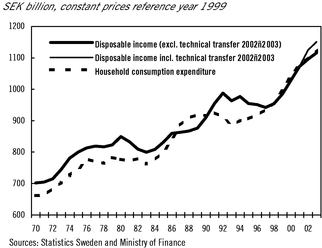

| Real disposable income(2) | | 3.3 | | 3.4 | | 4.2 |

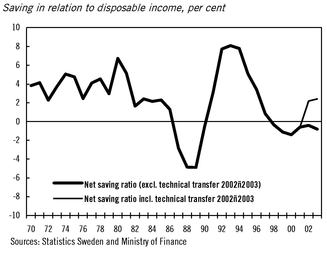

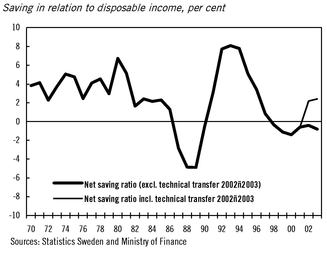

| Household net savings ratio, level(2) | | 2.1 | | 2.2 | | 2.9 |

| Current account balance(3) | | 2.5 | | 2.6 | | 3.6 |

| German 10-year government bond yield(4) | | 4.5 | | 5.3 | | 5.3 |

| Swedish 10-year government bond yield(4) | | 5.0 | | 5.4 | | 5.4 |

| TCW index(4) | | 125 | | 123 | | 122 |

- (1)

- Per cent of labour force, annual average.

- (2)

- The statistics for 2000 are affected by the Church of Sweden being included in the household consumption sector from this year. Changes are shown excluding this effect. The savings ratio includes saving in group pensions.

- (3)

- Per cent of GDP

- (4)

- Annual average

Sources: Statistics Sweden, National Labour Market Board, Riksbank and Ministry of Finance

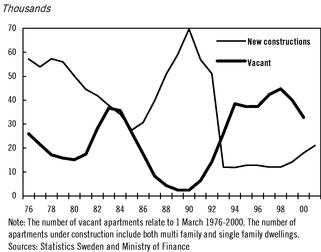

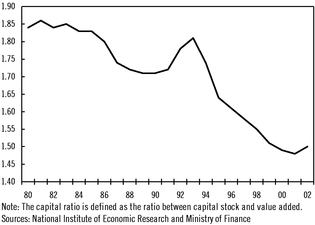

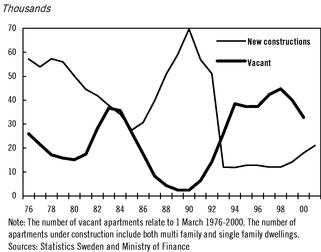

Investment activity is expected to increase again. Housing construction can accelerate even though supply restrictions dampen this rise. The strong industrial upswing entails a strong need to expand production capacity. The volume of investment in other parts of the business sector is expected to increase more slowly than previously.

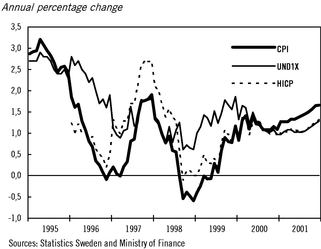

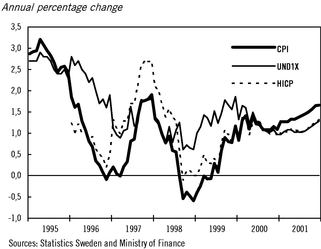

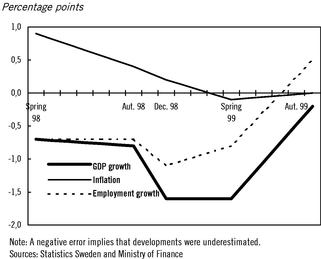

Inflation is still low. The rate of price increases only totalled approximately 1.2 per cent in July this year. These price increases are largely due to increased prices for oil products. However, the strong demand is expected to entail some increase in underlying inflation next year. The rate of inflation measured as CPI is expected to total 1.7 per cent towards the end of next year.

Altogether, growth is expected to continue to be good during the next few years while inflation is expected to remain low. Unused resources are so great in the initial situation that GDP can increase by 3.9 per cent this year and 3.5 per cent next year without any significant shortage situations arising.

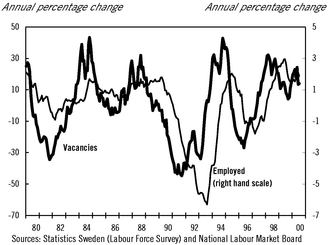

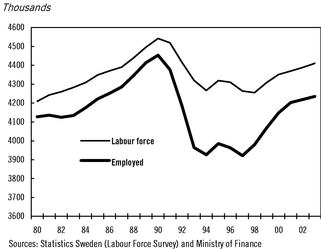

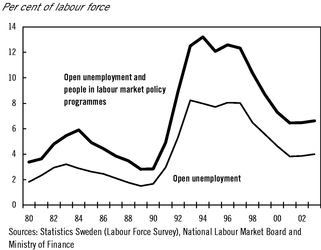

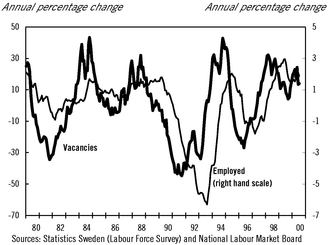

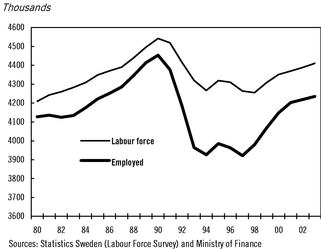

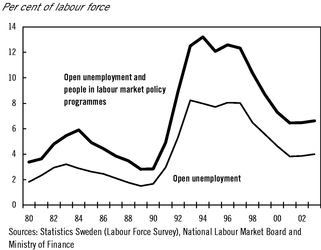

Employment and unemployment

The Swedish labour market is developing well although problems remain. In 1996, the Government and Riksdag set the target that open unemployment was to be halved from the then 8 per cent to 4 per cent in 2000. This target has now practically been achieved. In May 2000, open unemployment was 4.1 per cent and 3.8 per cent for women.

Open unemployment is expected to be around 4 per cent at the end of the year. Measured as an annual average, open unemployment is expected to be 4.6 per cent this year and 3.8 per cent next year.

The goal ahead is full employment. As a step towards this goal, the Government set the target in 1998 that the proportion of the population aged between 20 and 64 in regular employment should increase from 75 to 80 per cent by 2004. This target is also within reach. Employment is increasing practically throughout the country, although large regional imbalances remain. Most new jobs are in the private services sector.

8

A number of observations indicates that employment will continue to increase during the year. The number of notified vacancies increased sharply at the beginning of the year. Employment is expected to increase by around 134,000 persons between 1999 and 2001. This increase is taking place almost exclusively in the private sector. The regular employment ratio for persons aged between 20 and 64 is expected to rise to 77.7 per cent next year.

Despite the rapidly falling unemployment, unused resources are still available in the labour market. No general shortage situations are expected to arise this year or next year. However, there are indications of shortage situations regionally and in certain sectors.

Energetic action is taken to increase labour supply. The maximum charge reform will lead to reduced marginal effects for families with children. Compensation for part of the individual pension contributions and adjustments of the threshold to reduce the proportion paying state tax reduces marginal tax for those on low and medium incomes.

The system of employment support and the recently introduced activity guarantee aim at increasing the employment ratio for those groups that still have a weak foothold in the labour market. Older persons, those with functional disabilities and citizens from outside the Nordic area are prioritised groups.

The overall goal for the Government's working group in the area of ill health is to give people the prerequisites to remain in or return to work according to their ability. Active measures are to be introduced to enable those on sick leave and disability pensions to be able to return to working life full or part time.

The Government intends to introduce a system for individual increase in skills in working life to reinforce the position of the employee in a more and more demanding and changing labour market. Major investments are made in education and training and the provision of skills. The increase in study places and universities and other institutions of higher education will dampen the increase in labour supply somewhat for a time. However, in a longer period, the increased investment in education will have positive effects for labour supply as the number of well-educated people will increase. This will then improve the prospects for a return to full employment in Sweden.

Table 1.4 Employment, unemployment and wage formation

| | 1994

| | 1995

| | 1996

| | 1997

| | 1998

| | 1999

| | 2000

| | 2001

|

|---|

| No. of employed(1) | | 3 927 | | 3 986 | | 3 963 | | 3 922 | | 3 979 | | 4 068 | | 4 149 | | 4 202 |

| | Private sector(1) | | 2 633 | | 2 697 | | 2 698 | | 2 695 | | 2 735 | | 2 805 | | 2 886 | | 2 929 |

| | Public sector(1) | | 1 290 | | 1 287 | | 1 263 | | 1 223 | | 1 241 | | 1 260 | | 1 260 | | 1 270 |

| Proportion of employed aged between 20 and 64(2) | | 74.2 | | 74.8 | | 74.7 | | 73.9 | | 74.6 | | 75.9 | | 77.0 | | 77.7 |

| Open unemployment(3) | | 8.0 | | 7.7 | | 8.1 | | 8.0 | | 6.5 | | 5.6 | | 4.6 | | 3.8 |

| Labour market programmes(3) | | 5.3 | | 4.4 | | 4.5 | | 4.3 | | 3.9 | | 3.1 | | 2.6 | | 2.6 |

| Hourly wage cost(4) | | 2.4 | | 3.3 | | 6.0 | | 4.5 | | 3.8 | | 3.4 | | 3.5 | | 3.5 |

| Development of productivity in business sector(4) | | 3.8 | | 2.5 | | 1.3 | | 3.3 | | 1.4 | | 1.2 | | 2.2 | | 2.5 |

- (1)

- Thousands of persons

- (2)

- Those in regular employment as a percentage of the population aged between 20 and 64

- (3)

- As a percentage of the labour force

- (4)

- Annual percentage change

Sources: Statistics Sweden, National Labour Market Board and Ministry of Finance

9

1.2.3 Scenarios up to 2002 and 2003

After a long period of good growth, the gap between actual and potential GDP is expected to close at the end of 2001. This means that growth will subsequently be determined by the possibilities of further increasing the use of resources without inflation accelerating.

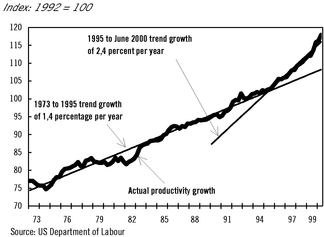

No forecast has been made for the period after 2001. Instead, an estimate has been made on the basis of certain assumptions. It is assumed that GDP will increase at the same rate as increased productivity and the increase in labour supply, which together is expected to make possible growth of over 2 per cent each year. However, there are indications that the long-term sustainable growth can be one or a few tenths of a percentage point higher than that.

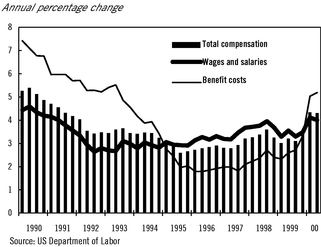

The labour market and wage formation have to date functioned better than many thought possible. Total wage increases including wage drift are expected to be 3.5 per cent per year also after 2001. It is important that wage increases are moderate in order for the trend on the labour market to continue favourable in the next few years.

1.3 Economic policy

The premise for economic policy is that sound public finances, stable prices and a well-functioning wage formation constitute the foundations for high sustainable growth and employment.

1.3.1 Sound public finances

Fiscal and budget policy are controlled by two overriding goals: Public finances shall generate an average surplus of 2 per cent of GDP over a business cycle and expenditure shall not exceed the set expenditure ceilings.

There are a number of reasons why both these goals are of central importance for economic policy:

- •

- Good welfare requires strong public finances. The proportion of elderly people will increase greatly in future. This will mean increased expenditure on pensions and health and social services as well as reduced revenue as the proportion of people of working age will fall.

- •

- There must be a safety margin in public finances so that the next downturn can be counteracted by an active fiscal policy. Excessively high deficits could lead to a large increase in interest rates in a recession as well.

- •

- Saving in Sweden must be high to be able to reduce Sweden's international indebtedness at the same time as the level of investment is high. The public sector must also contribute to this.

- •

- The expenditure ceilings prevent temporary increases in income being used to pay for permanently increased expenditure. In this way, painful savings are avoided when the economic situation deteriorates.

- •

- Sweden has undertaken in the EU Stability and Growth Pact to have a medium-term goal that public finances should be in balance or surplus.

The surplus target for 2001

Detailed targets are set each year on the basis of the long-term goal for public finances of a surplus of 2 per cent of GDP on average over a business cycle. In conjunction with the Budget Bill, the Government is proposing a target for the coming year. The target is set on the basis of the contemporary assessment of the state of the economy. The premise is that a 2 per cent surplus can be achieved when use of resources in the Swedish economy is at a level which it is possible to achieve without inflation accelerating, i.e. the long-term sustainable use of resources.

10

In last year's Budget Bill, it was established that the surplus target for public finances for the current year should be 2 per cent since it was then expected that that the long-term sustainable use of resources would be achieved this year. The Government further maintained that if the growth was to significantly depart from the estimated growth for cyclical reasons, the corresponding discrepancy would be tolerated in the surplus target. This year, it is estimated that public finances will have a surplus of 3.4 per cent of GDP, i.e. clearly over target.

The Government now makes the assessment that the use of resources in the economy can increase more than what was previously assumed to be possible without inflation accelerating. The gap between actual and potential GDP is now assumed to be closed by the end of 2001. This is a very positive development. There is thus scope for growth over the long-term sustainable level this year and next year without inflation accelerating.

There are a number of reasons for this assessment. Since the mid-1990s, the Swedish economy has undergone major changes. Budget consolidation, low inflation policy, increased competition and the investments in education, training and entrepreneurship are some explanations why the Swedish economy is developing better than expected. Another important explanation is the focus of labour market policy on activity and skills.

If fiscal policy was to be focused on achieving a surplus of 2 per cent of GDP in 2001 by proposals for large tax cuts and expenditure increases, this would entail a marked risk for overheating in the present situation. Historical experience clearly indicates that overheating brings great human and economic strains.

The Government is therefore proposing that the target for surplus in public finances in 2001 be increased from 2 to 2.5 per cent of GDP in order to reduce the risk of overheating. In this way, public debt can be decreased. If growth significantly diverges from estimated growth for cyclical reasons, the equivalent discrepancy in the surplus target shall be tolerated, however.

Even after this increase, it is estimated that the surplus in public finances will exceed the goal now set, given the assessment of economic development that can now be made. This increasing surplus, which, among other things is due to extraordinary revenue, shall be regarded as a safety margin and will not be used for reforms. The experiences of the 1990s clearly show the importance of achieving the set targets. Confidence takes an extremely long time to build up, although it can be lost in a very short time.

Despite the increase in the surplus target and the safety margin, resources are available to increase expenditure and reduce taxes without this being accompanied by a substantial increase in the risk of overheating. Moreover, public debt falls strongly which will strengthen Sweden in the long term.

In the Spring Fiscal Policy Bill, the Government proposed a number of reforms but no tax cuts. The Government is now carrying out these reforms but is also proposing tax cuts of around SEK 13 billion next year. Furthermore, it is proposed that the freezing of tax assessment values on houses and apartment blocks be ended so that the connection between tax assessment values and market values is restored. In order to avoid tax revenue increasing as a result of the increase in tax assessment values, a reduction in tax rates for houses and apartment blocks and an adjustment of the exempted amount in wealth tax are proposed.

As a result of the Government's proposal, fiscal policy will be expansive next year. This shall be viewed in the light of there then being unused resources in the Swedish economy. However, fiscal policy will be considerably less expansive than if the whole additional margin over the previous target for the surplus in public finances of 2 per cent had been used.

11

Tabell 1.5 Public Finances

Per cent of GDP

| | 1994

| | 1995

| | 1996

| | 1997

| | 1998

| | 1999

| | 2000

| | 2001

|

|---|

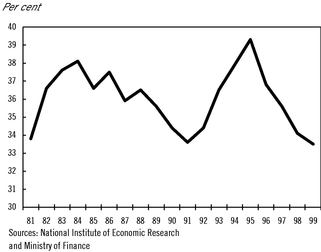

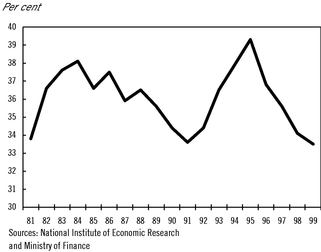

| Expenditure ratio | | 67.3 | | 64.6 | | 62.6 | | 61.1 | | 58.7 | | 58.4 | | 55.5 | | 53.7 |

| Income ratio | | 56.4 | | 56.7 | | 59.3 | | 59.1 | | 60.6 | | 60.2 | | 58.9 | | 57.2 |

| Tax ratio(1) | | 47.3 | | 48.3 | | 51.3 | | 52.0 | | 53.4 | | 53.5 | | 52.6 | | 51.5 |

| Financial savings | | -10.8 | | -7.9 | | -3.4 | | -2.0 | | 1.9 | | 1.9 | | 3.4 | | 3.5 |

| Surplus target | | -3.0 | | 0.0 | | 0.5 | | 2.0 | | 2.5 | | 0.5 | | 2.0 | | 2.5 |

| Net debt | | 21.0 | | 22.7 | | 19.4 | | 18.2 | | 15.8 | | 11.4 | | 0.5 | | -3.7 |

| Consolidated gross debt(2) | | 77.4 | | 76.3 | | 76.0 | | 74.9 | | 72.4 | | 65.6 | | 58.9 | | 53.2 |

- (1)

- Including taxes to the EU.

- (2)

- Measured according to the Maastricht rules.

Sources: Statistics Sweden and Ministry of Finance

Surpluses after 2001

It is assumed that the annual surpluses in public finances will be 2 per cent of GDP in the years after 2001. If no decisions are made on tax cuts or expenditure increases, the surpluses would be considerably larger than this, however. The additional surpluses have therefore been transferred to households for technical accounting purposes. Given the assessment of consumption that has been made, household savings will then increase. Although a development of this kind is not unreasonable, the change in the savings ratio shall in the first place be viewed as a technical consequence of other assumptions.

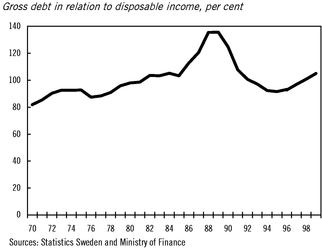

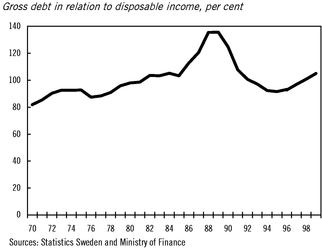

The consequences of the surpluses for public debt are great. The consolidated gross debt measured according to the Maastricht criteria, is now under 60 per cent of GDP. Net debt is expected to be removed next year.

Reduced debt is a very desirable development. The Long-Term Planning Commission report (SOU 2000:7) shows that the social welfare system will be under considerable pressure as the proportion of elderly in the population increases greatly from around 2008. The number of people of active working age will fall at the same time as a greater number are to be provided for through pensions, etc. At the same time, demand for health care and social services can be expected to increase. A smaller working population is to provide for an increasing number of elderly.

In order to cope with the strains on the economy and public finances ensuing from a great increase in the proportion of elderly in the population after 2008, surpluses in public finances are required for a number of years to come. This is an important reason to maintain the target of a 2 per cent surplus on average over a business cycle.

The expenditure ceilings

Since consolidation of the public finances was started in 1994, the central government budget has improved at a rapid rate. A contributory reason for this success has been the reform of the budget procedure which was carried out at the end of the 1990s.

In the new budget procedure, the Government proposes a ceiling for central government expenditure in the Spring Fiscal Policy Bill. This ceiling must not be exceeded. The expenditure ceilings are set in advance for three years at a time and expenditures have been within the ceiling every year since the ceilings were introduced in 1997. The system with expenditure ceilings has worked well.

12

However, for the current year there is some risk that the expenditure ceiling will be exceeded if no action is taken. The Government is therefore proposing certain measures to limit expenditure. The Government's assessment is that after these measures, expenditure will be under the ceiling with a budgeting margin of approximately SEK 0.6 billion. The Government will monitor events carefully and will take action if it is shown to be necessary. The expenditure ceiling shall be maintained.

In accordance with previous decisions, the expenditure ceiling is increased with SEK 25 billion between 2000 and 2001. This increase will be used inter alia for additional resources for education, health care and social services, increased child allowance, increased resources to the worst-off pensioners and substantial investment in the judicial system. Furthermore, the good development of the economy makes it possible to reduce taxes by approximately SEK 13 billion in relation to this year. Welfare is increasing at the same time as taxes are being reduced.

Next year expenditure is also expected to be close to the expenditure ceiling. A considerable problem is the rise in expenditure for increased ill health. The increase in costs reflects an unacceptable increase in ill health in working life. The Government has appointed a working group to work out a plan of action for the entire ill health area.

The new budget procedure has on the whole worked well and has improved the conditions for responsible economic policy. However, there are some problems. A number of measures have been proposed in the evaluation of the budget procedure (SOU 2000:61). Moreover, a review is taking place in the Riksdag. The Government intends to come back to the question of possible improvements of the budget procedure at a later date.

The basis for the Government's continued development of the budget procedure is that the principles on budget discipline in public finances must not be weakened in relation to the principles that apply now.

1.3.2 Stable prices

Stable prices are a fundamental prerequisite for a successful economic policy. High inflation creates poorer conditions for sustainable high growth and thus also for stable high employment. A high, difficult-to-predict inflation has moreover negative distribution effects.

The Riksbank is carrying out monetary policy independently. The overall task for monetary policy is price stability. The Riksbank has defined price stability so that the increase in the consumer price index is to be limited to 2 per cent with a tolerance of 1 percentage point in each direction.

The Government supports the direction of monetary policy and stands behind the inflation target.

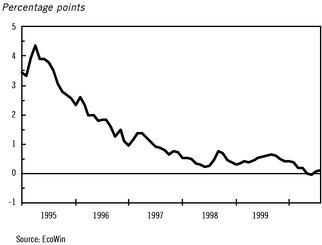

Inflation continues to be at a low despite the high level of demand in the Swedish economy. This year CPI is expected to increase by 1.1 per cent. Next year, CPI is expected to increase by 1.7 per cent.

The Riksbank has clarified that at present it is the assessment of UND1X over a one to two-year horizon that determines the conduct of monetary policy. UND1X is a measure of inflation where the direct effects of changed interest rates, taxes, and subsidies have been excluded from CPI. This year, UND1X is estimated to increase by 1.1 per cent. Next year, UND1X is expected to increase by 1.3 per cent.

13

The interest rate

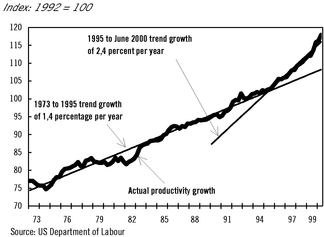

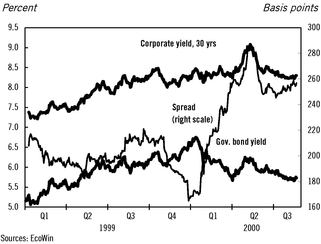

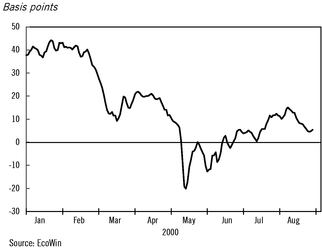

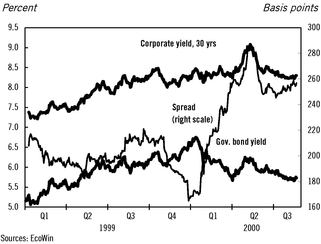

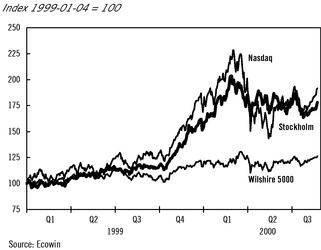

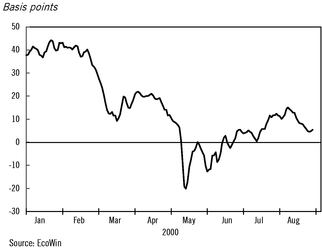

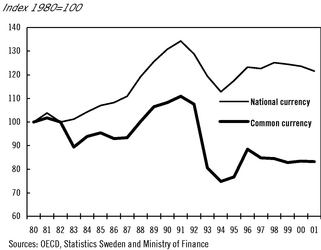

In 1999, international interest rates increased by approximately 2 per cent due to the increasingly strong global growth. Since the year-end, a stabilisation has taken place and 10-year interest rates have fallen in the range of 0.5 percentage points.

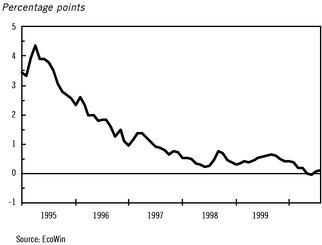

Despite the international increase in interest rates, the Swedish bond yields have risen rather less than the German. The interest gap in relation to Germany which was over 4 percentage points five years ago, has practically disappeared. Consolidation of public finances and confidence in price stability policy has laid the basis for this development.

During May and June, the ten-year Swedish bond yield was even lower than the German. The long interest rate in Sweden was hardly a tenth of a percentage point over the German in September 2000.

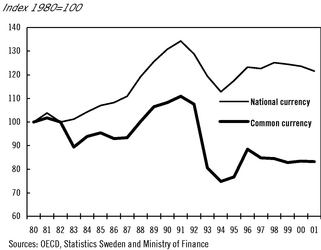

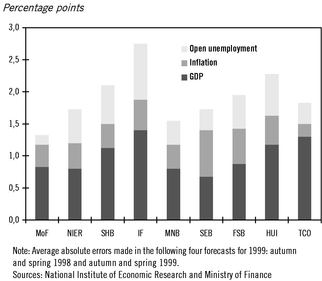

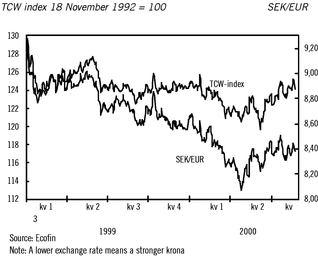

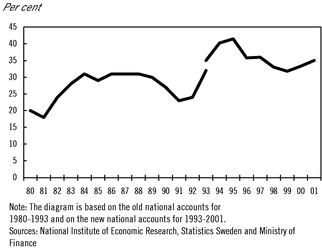

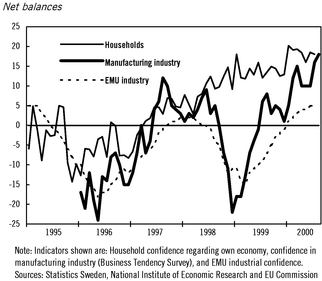

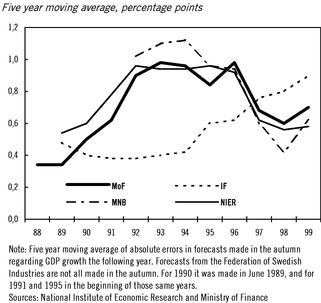

Diagram 1.1 Yield differential with Germany, ten-year treasury bonds

During the past year, Swedish monetary policy has been shifted in a less expansive direction in the light of the strong growth and a gradual increase in resource use. Despite strong demand, inflation has continued to be low and inflation expectations have been in line with the inflation target.

Confidence in public finances, the price stability target, increased competition and lower inflation tendencies have created the prerequisites for favourable inflation prospects. The Riksbank has increased the instrumental rate from a minimum of 2.90 to 3.75 per cent. Despite these increases, the Swedish instrumental rate is lower than the ECB instrumental rate.

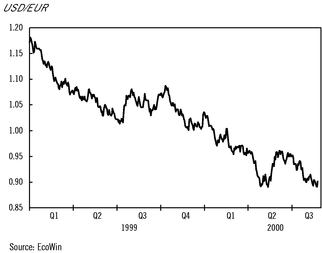

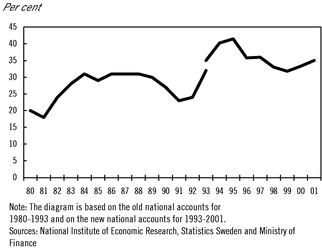

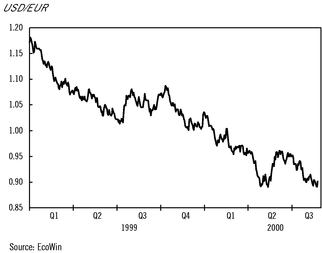

The krona

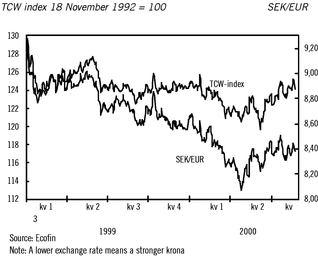

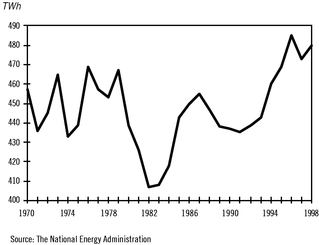

Since early 1999, the krona has been relatively stable in relation to an average of currencies. The trend has been for the krona to appreciate against the euro and it is now quoted at approximately SEK 8.40 per euro. This appreciation in relation to the euro has mainly been balanced by a weakening in relation to the dollar. The strengthening of the krona during the spring can partly be due to direct investments and purchase of Swedish shares.

14

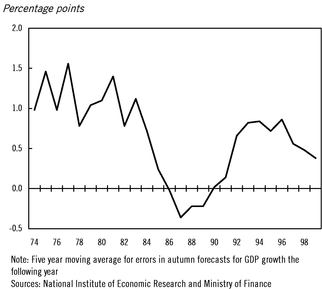

Diagram 1.2 The exchange rate of the krona in relation to the euro and a weighted average of currencies

EMU

The introduction of the EU's single currency, the euro, is a historical and important step in European integration. The monetary union affects Sweden to a great extent, both economically and politically, also when we, as hitherto, stand outside. Banknotes and coins in euro will be introduced in the monetary union on 1 January 2002. During its presidency of the EU, Sweden will, if necessary, contribute to an efficient introduction. It is important for the growth and stability of the whole EU that the monetary union is a success.

Sweden decided not to participate in the monetary union from the outset. However, Sweden is keeping the door open for participation at a later date. A decision on participation must have broad public support and shall be submitted to the Swedish people for consideration in a referendum.

A commission will be appointed on the prerequisites for fiscal policy in the event of Swedish participation in the monetary union. This commission will also analyse the need for "buffer funds" to increase the possibilities of stabilisation policy.

The Government's view is that it is not at present of immediate interest to take part in the European exchange rate co-operation ERM2.

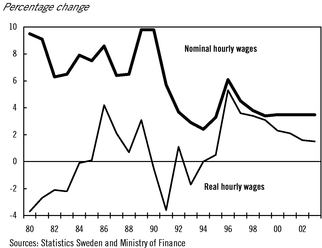

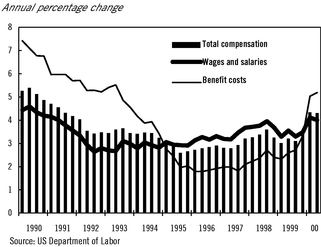

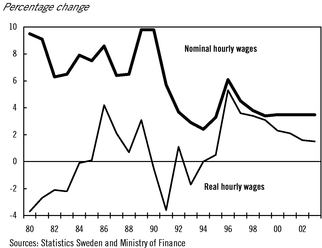

1.3.3 Wage formation

A well functioning wage formation is of crucial importance for a continued good employment development with the aim full employment. Nominal wage increases must remain moderate even though labour demand continues to increase and open unemployment falls rapidly. If pay increases are too high, there is a risk that unemployment will rise again. The objective is to combine low inflation and good real wage increases with a strong increase in employment.

Swedish wage formation is facing an important test in 2001. For the first time after the deep economic crisis in the 1990s, new wages are to be set for almost the entire labour market in a situation of falling unemployment and rising labour demand in combination with low inflation and dampened pay increases in the surrounding world.

15

The prerequisites for the social partners to be able to deal with the challenge confronting them are favourable in many respects:

- •

- A stable, strong confidence in price stability has been established. No wage earner need risk that the pay increases that have been negotiated will be undermined by uncontrolled inflation.

- •

- In recent years, wage earners have experienced that moderate nominal pay increases can contribute to good, stable development of real wages.

- •

- Employers have become increasingly aware of the limitations that exist as regards passing on costs to consumers.

- •

- Employment has increased and some scope has been created for cutting taxes. The situation has improved markedly for many wage earners during the most recent contract period as a result of the good employment trend.

The Government is now proposing further tax cuts. If the pay bargaining leads to excessively high pay increases, there is a risk that Sweden will end up in an overheating situation. The economic room for further tax cuts in coming years would then disappear. In this situation, there might even be grounds for reviewing fiscal policy.

However, inflation is still low and total pay increases are moderate. Assessments of the future are also favourable. The awareness of the links between employment, productivity growth, and the real wage trends has increased. A continued good employment trend is conditional on the scope for real wage increases created by the long-term productivity development in the economy not being exceeded.

Considerable changes of the institutional frameworks of wage formation have been carried out. Co-operation agreements have been signed in a number of sectors where the parties have reached agreement on, for instance, new bargaining rules. A new mediation institution has been set up with the task of supporting the parties in their endeavour to combine stable real wage development with a continued rapid, sustainable increase in employment. Certain changes have also been introduced in the legal framework within which negotiations are carried out.

Labour market policy has been focused to an increasing extent on reducing the risk for bottlenecks in the labour market and substantial investment in education and training has taken place with a view to increasing the supply of highly qualified labour.

In the present economic situation, the upward pressure on wages for the groups in the labour market that are most in demand and in the fastest growing regions can nevertheless be high. The social partners must be able to deal with the problems that this can entail.

Wage formation has a great influence on many areas. The social partners have a special responsibility for counteracting pay differences due to sex. This is one of the most important issues in equal opportunities policy. The Government has therefore proposed that the equal opportunities act be made more stringent.

Working hours

The starting point for the Government's work on the issue of working hours is that it is important to shorten working hours and to increase the influence of the individual over the allocation of working hours. A reduction in working hours can take place by agreement as well as by legislation. Legislation is required if everybody is to benefit from a reduction in working hours. The Government intends to reduce working hours within the framework of changed legislation.

The working hours issue includes important welfare policy choices. A reduction in working hours is discussed in public debate as a means of reducing the risk of burn-out and providing scope for a life

16

which is not only centred on work. After a number of years with increasing average working hours per employee, many want to increase the time available for life outside of working life.

The value of a reduction in working hours must always, however, be weighed against the need for other reforms and costs must be taken into consideration. If we reduce working hours, we are taking part of future growth in the form of more leisure instead of increased private and public consumption. The long-term consequences of a reduction in working hours for the public sector activities must be particularly taken into account.

The Government Offices' working group for working hours issues has had the task of assessing the prerequisites for and consequences of different changes in working hours. These analyses have referred both to economic aspects and welfare effects. The report "Shorter working hours—for and against" has been circulated for comment. The responses are at present being studied in the Government Offices. The Swedish Trade Union Confederation and the Confederation of Professional Employees have also recently presented proposals on working hours reforms.

A reform of working hours is important. The Government, the Left Party and the Green Party note, however, that the rate, the extent and the approach to a reform of working hours require further consideration.

Work environment

In order to meet the problems in today's working life, a work environment policy is required that allows different solutions adapted to individual preferences and operational requirements and which benefits both employees and employers. The interaction between the employer and the employee in the arrangement and organisation of work is key for the productive work environment and good work.

The Government's work environment policy is to promote good growth and secure welfare. The Government is therefore proposing that the appropriation to the National Board of Occupational Safety and Health be increased by SEK 70 million, SEK 20 million of which was set aside already in the Spring Fiscal Policy Bill. At the same time, legislative work is in process that aims to improve supervision. In this way, work environment work can be improved, in particular with regard to method development and in relation to the most exposed work places.

1.4 Reforms for full employment

Sweden shall be a country with full employment, high growth and good welfare. The basis for this is healthy public finances and stable prices. On this basis, an offensive for full employment is being carried out at the same time as considerable investments are being made in the field of education. Education and training, development and competence shall characterise the whole of Sweden.

An offensive for full employment

The total work input in Sweden, i.e. the total number of hours worked, is of crucial importance for making possible good welfare. A high supply of labour is important for future growth and for opportunities to finance the welfare system when the proportion of elderly persons increases.

In its report (SOU 2000:7), the Long-term Planning Commission underlined the importance of taking steps already today so that Sweden will be well-prepared to meet the future. The policy focused on sustainable growth, increased employment and sound public finances which the Government has conducted since 1994 is well in accord with what is required to meet the challenges that the Long-term Planning Commission drew to attention.

17

In the Spring Fiscal Policy Bill, the Government presented an offensive for growth and social justice. The objective is full employment. Now this offensive is being made a reality:

Unemployment is to be pushed down. Sweden shall again show that it is possible to combine low inflation and low unemployment with social justice and equal conditions of life. A broad programme of measures is being carried out to press unemployment down to 4 per cent in 2000. Among other things this programme includes:

- •

- that the labour market programmes is focused on the long-term unemployed to a greater extent than to date,

- •

- that the requirement for activity in unemployment insurance be clarified,

- •

- that a generous employment support be introduced for employers that employ people who have been unemployed for a long time.

Employment and labour supply shall increase. The most important way for counteracting the risk that people are excluded from the labour market is measures to increase employment. Work has an intrinsic value, it confers self-esteem and makes it possible to earn a livelihood. Moreover, it is very important that each individual's ability to work is made use of for labour supply to increase and for making it possible to retain a good welfare. The programme entails for instance:

- •

- that active measures are carried out to enable those on sick leave and disability pensions to return to working life,

- •

- that the Special Adult Education Initiative is prolonged to increase the supply of trained labour,

- •

- that a maximum childcare charge is introduced to reduce the marginal effects and thus promote work and education.

The opportunities for taking part in working life are to be increased for all. People with an immigrant background have considerable higher unemployment and lower employment than other Swedes. This must be changed. Everyone is needed in the labour market. The programme entails for instance:

- •

- that the opportunities for people with foreign education to complement their education are strengthened,

- •

- that measures to stimulate ethnic/cultural diversity in public administration and private companies are introduced,

- •

- that resources are made available for advisory initiatives for immigrants starting or running small businesses.

Knowledge, education and training

Sweden is to be in the forefront as a knowledge nation. Our future competitiveness will be determined by the breadth of our skills and leading edge competence. Sweden is to be a country characterised by entrepreneurship and innovation. New technology, new knowledge and new ideas are essential driving forces for the development of society.

Knowledge and a well-educated population constitute an important part of the Government's policy for growth and social justice. Internationally prominent education and lifelong learning for all—from pre-school to higher education and in working life—are an effective tool for equality and development.

18

The strengthening of the educational task of the pre-school underlines its task in lifelong learning. Universal pre-school for four and five-year-olds, a maximum childcare charge and expanded right to pre-school for the children of unemployed and those on parental leave give more access to pre-school.

The Swedish school achieves good results in international comparisons. At the same time, schools are faced by considerable difficulties and challenges. The new grade system makes clearer demands. More than every tenth pupil who leaves compulsory school is not eligible for upper secondary school. This is not acceptable. All pupils must obtain good basic knowledge, learn to read, write and count.

Far more pupils must achieve the goals at upper secondary school. Growth and new resources provide municipalities with greatly increased resources, creating good opportunities for investment in schools. Moreover, considerable investments are taking place in developing teachers' skills. The guaranteed tuition time is being expanded on all upper secondary school programmes from next year. The Government also intends to improve the follow-up of results in school.

The Government is therefore proposing greatly increased resources to schools in the coming years. During the period 2001 to 2006, SEK 17.5 billion is to be made available to education, SEK 0.5 billion of it from next year. Thereafter an additional SEK 1 billion will be allocated each year until the level of SEK 5 billion is reached.

Table 1.6 Funds for education

SEK Billion

2001

| | 2002

| | 2003

| | 2004

| | 2005

| | 2006

|

|---|

| 0.5 | | 1.5 | | 2.5 | | 3.5 | | 4.5 | | 5.0 |

The Government is also proposing that the "contact days" in temporary parental benefit be restored next year.

The expansion of higher education is continuing. The long-term goal is for 50 per cent of a year cohort to have started higher education by 25 years of age. The number of places increases with approximately 100.000 between 1997 and 2003. This expansion has been focused on natural sciences and technology but it is now being extended to other areas.

The study support system is being reformed and the study grant portion of study allowance increased. The grant portion will be 34.5 per cent of study support from the second half of 2001. Moreover, the permitted amount of independent earnings will be increased and study allowance will confer pension rights.

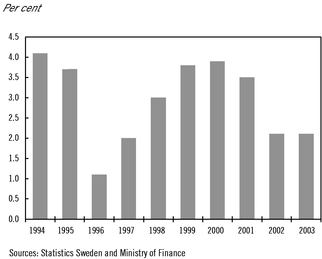

Altogether, Sweden uses almost 4 per cent of GDP for research and development (R&D). This is more than any other country in the world. The state has a particular responsibility for guaranteeing the freedom of research and supporting vital basic research and doctoral studies. The central government appropriation for basic research and post-graduate education is increasing by almost SEK 1.3 billion during the period 2000 to 2003. Postgraduate education is of strategic importance since the need for trained researchers is increasing both in higher education and the rest of society.

1.5 Reforms for increased welfare

Substantial resources are being invested in key areas of welfare in the next few years. Universal welfare is the foundation of the Government's endeavour for development and equality. The financial situation of families with children is being strengthened. The resources available for health care, education and social services are increased. In addition to this, a number of measures are proposed to increase social justice and security in Sweden.

19

Children

Sweden is to be a country where all children and young people have a good upbringing. During the next few years, considerable investments are being made for families with children. Altogether, the additional resources to families with children already announced by the Government will total approximately SEK 9 billion by 2003. An additional SEK 6 billion is being made available for the reform of study support.

Child allowances and study grants are being increased as from 1 January 2001 by an additional SEK 100 a month. Child allowance and study grant will then be SEK 950 per child and month. The supplement for large families is being correspondingly increased.

A broad family policy reform is being introduced in stages. Children of the unemployed will be given the right to pre-school activity as from 1 July 2001. A maximum childcare charge will be introduced in 2002 and funds made available to municipalities for quality assurance of this activity. The maximum charge will be 3 per cent of income, at most SEK 1,140 per month to have a child at a day-care centre.

Parental insurance will be extended by a month in 2002. Two months will be reserved for the mother and father respectively within the framework of the extended parental insurance. This will mean the introduction of an additional "father's" and "mother's" month in parental insurance. A right to childcare is also being introduced for children of parents who are unemployed and parents who are on parental leave with younger siblings. Universal pre-school for four-year-olds and five-year-olds will be introduced in 2003.

Table 1.7 Family policy reforms

SEK Million

| | 2001

| | 2002

| | 2003

|

|---|

| Maximum childcare charge, etc. | | 150 | | 4 400 | | 5 600 |

| Study allowance (including pensions) | | 2.100 | | 5.600 | | 6.200 |

| Mother's/Father's month | | | | 1 000 | | 1 000 |

| Increase in child allowance (including study grant in study assistance) | | 2.500 | | 2.500 | | 2.500 |

| Contact days | | 60 | | 160 | | 280 |

| | |

| |

| |

|

| Total reforms | | 4.810 | | 12.660 | | 15.580 |

| | |

| |

| |

|

Good welfare

Sweden shall be a country with equality and equality of opportunity. Every person must have the opportunity to make use of his or her ability and willingness to participate. All discrimination shall therefore be combated. Similar opportunities shall apply to all regardless of sex, ethnic or cultural background.

A policy for social justice is based on education, work and universal welfare. If everyone has access to a good education, there will be an even distribution of knowledge. Needs—not financial circumstances—shall determine health care and social services. This evens out the conditions of life between healthy and sick persons or those with functional disabilities.

As a consequence of this, the Government has consistently given priority to health care, education and social services since 1994. Firstly, through the orientation of the consolidation programme and subsequently by making resources available to municipalities and county councils as the economy improved. The good growth will also entail substantial revenue increases for the local government sector in the next few years.

20

A well-functioning school, health care and social services are a prerequisite for the welfare society. Large parts of local government activity form the foundation for social justice and lay the basis for sustainable growth. This year, an additional SEK 21.3 billion in central government grants is being made available to health care, education and social services compared with 1996. Next year, the Government proposes that these investments be increased to SEK 25.3 billion.

Good growth and increased employment will lead to substantial increases in tax revenues in the next few years. This year, the tax revenue of the local government sector will be approximately SEK 46 billion higher than in 1996 and by 2003 it is expected to have increased by a further SEK 35 billion. The additional resources enable the local government activities to be safeguarded and reinforced.

In addition to general resources in the form of taxes and general central government grants, further resources are made available to municipalities and county councils in a number of areas.

- •

- A total of SEK 9 billion is invested in health care and social services during 2001-2004 primarily by funds released through the defence review. These investments aim at developing primary care, health care for the elderly and psychiatry.

- •

- SEK 0.5 billion is set aside for municipalities that introduce the maximum childcare charge for quality assurance of activities.

- •

- A deficit has arisen in the local government value-added tax system which is estimated to be at most SEK 4.3 billion at the end of the year. Since the Government on a number of occasions has underlined the importance of prioritising health care, education and social services while at the same time requiring the municipalities to run balanced budgets, it is proposed that this deficit shall be written down. The Government will also appoint a working group to review the system as a whole, including its redistributive effects. The Government intends to submit further proposals to the Riksdag at a later date.

Although the local government sector as a whole is now beginning to have strong finances, there is a number of municipalities and county councils that are lagging behind due to decreasing population, imbalances in the age structure, continued high unemployment, and low growth. These are external structural factors that the individual municipality is to a great extent unable to influence and which can only partly be compensated for by the equalisation system. Special initiatives can therefore be required for these municipalities and county councils.

The Government therefore set up a commission to prepare matters concerning temporary financial support to certain municipalities and county councils. The purpose of this support is to make it easier for these municipalities and county councils to carry out reconstruction and long-term sustainable measures to achieve balanced budgets. The responsibility for implementation of the measures required rests on the individual municipality or county council. The commission completed its work in July and proposed that support should be made available to 36 municipalities and 3 county councils. The Government intends to make a decision on the report during the autumn.

A major problem for the local government sector is the difficulty of following up activity. The Government has therefore taken an initiative to a development project concerning follow-up work in municipalities and county councils. An initial interim report has been presented, proposing the development of a municipal database. The database is intended to make it possible for municipalities and county councils to learn from one another and to improve the national follow-up.

The Government considers that it is important to improve follow-up by local government as well as by central government of the sector as a whole on the basis of national targets for different activities. The Government will therefore prioritise the work with the database and its follow up.

21

Security and solidarity

Sweden shall be a country where citizens feel security and participation in change. Universal welfare is to be developed and strengthened. The Government therefore proposed in the Spring Fiscal Policy Bill a number of proposals aiming at increased social justice and security.

The financial situation of the worst-off pensioners must be improved. The Government's proposal to increase the housing supplement and to make permanent the temporary increase of pension supplement is now being implemented. Moreover, a further improvement is proposed of the special housing supplement for pensioners, which will benefit the worst-off pensioners.

The Government is also proposing additional resources in other areas of welfare. In addition to the previously announced additional resources of SEK 200 million for 2002 and SEK 300 million for 2003, the Government is now proposing that a further SEK 100 million be made available to dental care. An action plan for disability policy has been adopted by the Riksdag.

Sweden shall be a country where criminality is low. The reasons for crime must be rectified at the same time as criminality is combated energetically. There has therefore been a substantial increase in resources to the judicial system. Additional resources have also been made available to the tax and customs system.

The Government aims for Sweden to again achieve the one per cent target for development assistance when central government finances so permit. As previously decided, development assistance will increase from SEK 12.5 billion in 2000 to SEK 14.1 billion in 2001.

For 2003, 0.81 per cent of GNP will be allocated to development assistance. A step will thereby be taken towards achieving the one per cent target.

1.6 Reforms for fair taxes

The primary purpose of taxes is to finance common expenses. Strong public finances are a fundamental condition for sustainable welfare. In addition, the tax system shall reduce gaps and stimulate work, investments, and a sustainable development. The distribution policy objective is important. The Government can never accept that the sacrifices made by the wage earners during the difficult years now should come to benefit the affluent through tax reliefs.

Reduced taxes for wage earners

The surpluses that now exist in public finances are a result of the responsible, deliberate policy that aimed to save the welfare society. Resources are now available to increase public expenditure and to reduce taxes at the same time as public debt can be paid off at an increased rate.

In the same way that the most vulnerable groups have been compensated for a number of the measures that were introduced to consolidate the public finances, for instance through the increase in compensation levels to 80 per cent and increased pensions and child allowances, resources are now available to compensate for the tax increases that affected wage earners, primarily those on low and medium incomes.

As a result of the budget consolidation, the proportion paying state tax has increased and employee contributions are now payable by all wage earners. A year ago the Government presented a strategy for an income tax reform. This reform consists of two parts. The first part consists of compensation for employee contributions. The second part consists of increasing the lower threshold in the tax table so that only 15 per cent of taxpayers pay state tax.

On 1 January 2000, the first step towards realising this reform was taken. A quarter of the employee contributions were compensated for at the same time as the threshold was increased so that

22

the proportion of taxpayers paying state tax was estimated to fall from 19 to 18 per cent. With regard to the budget as well as to national economy considerations, the Government now makes the assessment that there is scope to take a another step of the same size.

The Government is proposing a compensation for an additional quarter of the employee contributions. Wage earners will thus have received compensation for half of the employee contributions that she or he pays. The Government is also proposing that the lower threshold limit for charging state income tax be increased. This together with the increase of the basic deduction reduces the proportion of those who pay state tax to 16 per cent. These measures reduce marginal taxes for low and medium income wage earners and they also have a good profile since employee contributions are a heavier burden for low-income earners than for others.

The Government is furthermore proposing that travel deduction be increased from today's SEK 15 per 10 kilometres to SEK 16 per 10 kilometres.

Property tax

This year, property tax is expected to generate an income of SEK 23.1 billion that contributes to financing public welfare.

The charging of property tax has been limited in recent years by a number of decisions. The tax assessment values, i.e. the basis for property tax, have in principle been unchanged since 1997. Moreover, in 1998 the tax rate was reduced from 1.7 to 1.5 per cent. The tax rate in apartment blocks has been further reduced to 1.2 per cent in 2000.

The link between tax assessment values and market values is now to be restored. In recent years, the prices of detached houses and other housing has increased greatly in many areas of Sweden. In 2001, tax assessment values will therefore increase sharply in the areas where house prices have risen most. If no action is taken, central government revenue will increase by around SEK 10 billion next year.

The Government is now proposing that this tax revenue is used to reduce the tax rate on houses from 1.5 to 1.2 per cent and on apartment blocks from 1.2 to 0.7 per cent. At the same time, it is proposed that the exempted amount in wealth tax be increased to SEK 1 million for those living alone and SEK 1.5 million for jointly taxed couples. It is further proposed that capital gain tax on sale of housing be increased from today's 15 per cent to 20 per cent.

Through the measures proposed, a majority of Swedes will share tax reductions on properties.

The Real Estate Taxation Commission has recently submitted proposals as to how a more equitable design of property tax can be achieved and a more uniform treatment of different forms of ownership established. The commission also proposed a limitation rule that entails that charging of property tax for permanent residences be reduced in certain circumstances. The Government has initiated work aiming at being able to present a proposal to the Riksdag in spring 2001 containing proposals for a limitation rule. The approach adopted in this work is that households with normal income and wealth conditions shall not pay more than 6 per cent of household income in property tax. Such a rule should apply from 1 January 2001.

With regard to property taxation in a longer perspective, the Government intends to make proposals at a later date on the basis of the reports of the Real Estate Taxation Commission and the Property Assessment Taxation Commission.

Other tax changes

To benefit public transport and to balance the increase in diesel tax that is taking place within the framework of the green tax swap, value-added tax on public transport is to be reduced from 12 to 6 per

23

cent. The vehicle tax for older diesel-driven cars is to be increased to the level that applies for newer more environmentally friendly vehicles. In accordance with the proposals from the Traffic Taxation Commission, sales tax is being abolished on motorcycles, light lorries and light buses.

Pending it being possible to introduce alternative measures of control to support wind power, Sweden will request the EU Commission that the "environmental bonus" for electricity produced by wind power be extended for another couple of years. Later this autumn, proposals will be presented on a reduction of value-added tax for entry into zoos from 25 to 6 per cent and on improved and expanded opportunities to make tax deductions for professional fishermen.

The Government regards it as important to safeguard the Swedish shipping industry. The goal is to give Swedish shipping equal conditions for competition. The total support should be expanded to include the ferry industry as well. The Government intends to introduce proposals on a new support system which can come into effect on 1 January 2002.

1.7 An ecologically sustainable Sweden

Sweden is to set an example of ecologically sustainable development. The goal is an ecologically sustainable Sweden. The vision of a sustainable Sweden combines the best in the Swedish tradition of taking a comprehensive view and reforming gradually; social justice and internationalism, employment and the struggle for the life environment on the planet Earth.

The transformation of Sweden applies to all policy areas. Tax policy plays a key role and its importance will increase further. With a forward-looking employment, tax and environmental policy, Sweden can become the first country that builds the ecologically sustainable society. Environment and economics shall develop hand in hand. Ecological adaptation can serve as the driving force for green technical development and creation of new jobs.

In April 1999, the Riksdag adopted national environmental quality goals with a broad majority in the following 15 areas:

- 1.

- Fresh air

- 2.

- Good quality groundwater

- 3.

- Living lakes and watercourses

- 4.

- Living wetlands

- 5.

- A sea in balance with a living coast and archipelago

- 6.

- No overfertilisation

- 7.

- Only natural acidification

- 8.

- Living forests

- 9.

- A rich cultivated landscape

- 10.

- A magnificent mountain environment

- 11.

- Good urban environment

- 12.

- An toxic-free environment

- 13.

- A safe radiation environment

- 14.

- Protecting ozone layer

- 15.

- Limited effect on the climate

24

Work on environmental goals rests on five basic values: We shall promote human health, safeguard biological diversity, take care of our cultural heritage, preserve the long-term production capacity of the ecosystem, and ensure economical use of natural resources. This is the intent and purpose of an ecologically sustainable development. In recent years, major reinforcements have taken place with respect to conservation, environmental monitoring, land decontamination, and environmental research. The local investment programme has created a broad commitment in municipalities. Next year, extensive additional resources will be made available within a number of areas such as environmental monitoring, liming, windpower and care of nature reserves.

The foremost purpose of a green tax swap is to relate the tax system more closely to the environment. This leads to economic measures of control being given increased weight in environmental policy alongside administrative and information-related measures of control. If properly designed, economic measures of control give cost-effective signals to market participants to create prerequisites for an environmentally compatible life style and technology that makes sparing use of resources. Environmental taxes put a price on the environment so that it becomes more expensive, for instance, to pollute the air or water. Thereby, the participants in the economy will themselves bear the costs of the environmental effects they cause in the same way as they pay for other goods and services.

A green tax swap does not involve any increase in total tax uptake. Increased taxes on energy and environmental discharges are balanced by a reduction of other taxes, primarily on work.

Sweden was one of the first countries in the world to carry out a green tax swap—even though the concept of "green tax swap" was not used then. This year a further step was taken. Now yet another step is being taken. Energy taxation is being increased at the same time as tax on work is reduced.

Taxes—financing and control

An overall aim of taxes is to finance public expenditure. A lesson that can be drawn from the economic crisis in the 1990s is that welfare must be paid for. It is not possible to live over one's means in the long run. During the previous period of office, tax increases accounted for a large part of the consolidation of public finances, at the same time as they contributed to budget consolidation taking place in a way acceptable from a distribution policy perspective. The latter also illustrates another central main purpose of taxes, namely to contribute to a fairer distribution of income and wealth.

A further purpose of taxes is to contribute to setting the right price on products so that consumers and producers appreciate the real costs. Thus taxes can contribute to financing and fair distribution at the same time as they can contribute to a better use of our total resources.