Exhibit 99.c

Appendix 1

Sweden’s Economy

Appendix 1

Sweden’s Economy

Contents

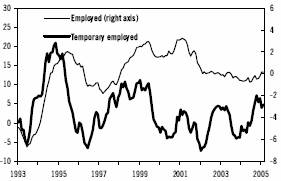

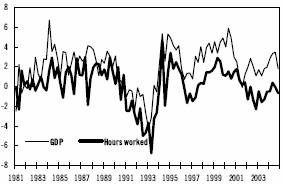

3

Diagrams

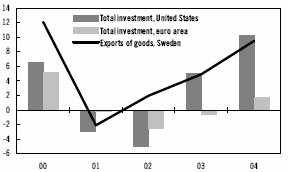

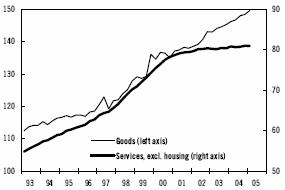

1.1 Investment and goods exports | |

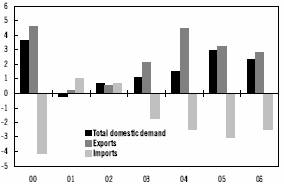

1.2 Contributions to GDP growth | |

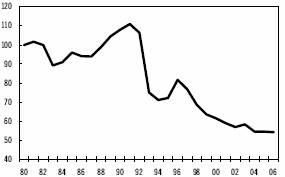

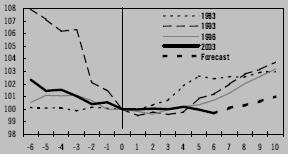

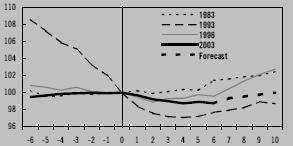

1.3 Industry’s unit labour cost in Sweden compared with 11 OECD countries, common currency (SEK) | |

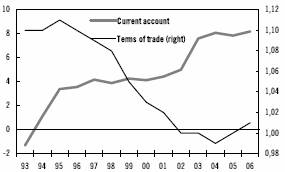

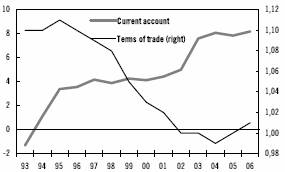

1.4 Current account and terms of trade | |

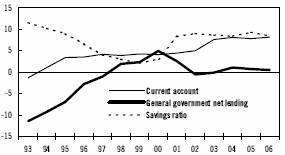

1.5 Current account, general government net lending and household savings ratio | |

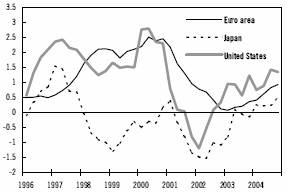

2.1 Employment growth in the euro area, the United States and Japan | |

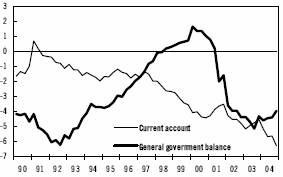

2.2 Budget balance and current account balance in the United States | |

3.1 Key interest rates in the United States, the euro area and Sweden | |

3.2 10-year government bond yields in the United States, Germany and Sweden | |

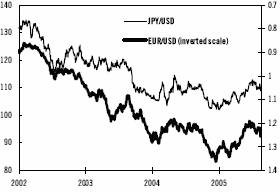

3.3 The US dollar against the yen and euro | |

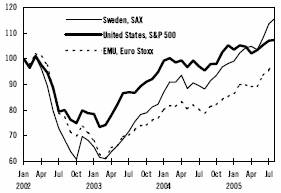

3.4 Stock market developments in the United States, the euro area and Sweden | |

3.5 The differential between 10-year government bond yields in Sweden and Germany | |

3.6 TCW index | |

5.1 Industry’s unit labour costs in Sweden compared with 11 OECD countries | |

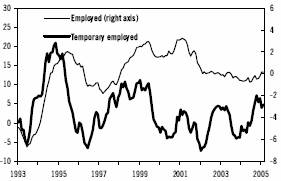

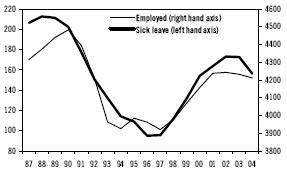

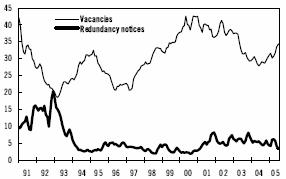

6.1 Temporary employment and total employment | |

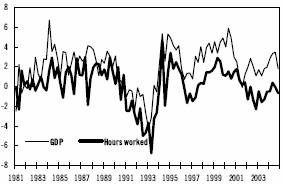

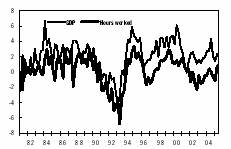

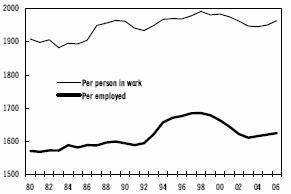

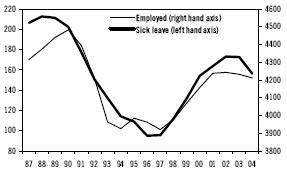

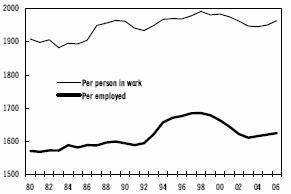

6.2 Hours worked and GDP | |

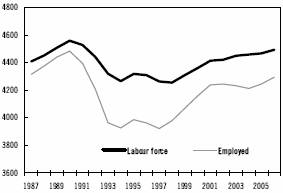

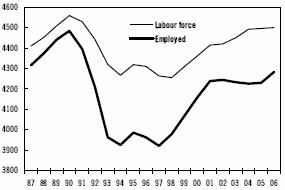

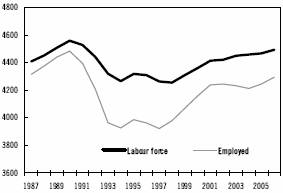

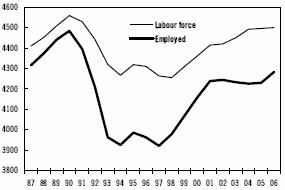

6.3 Supply of labour and employment | |

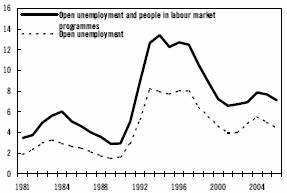

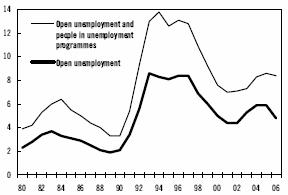

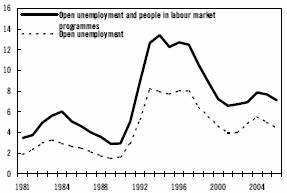

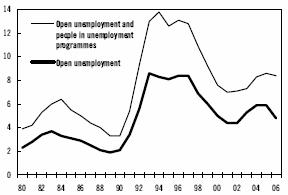

6.4 Unemployment | |

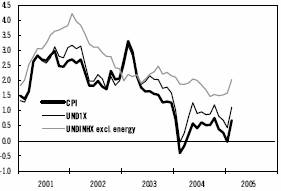

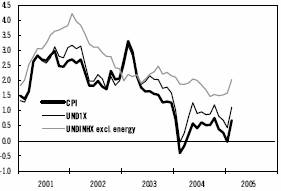

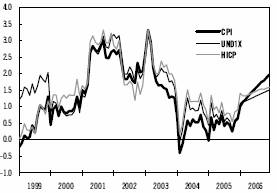

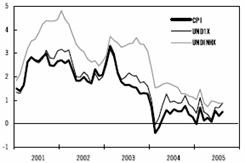

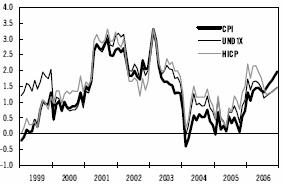

8.1 Inflation (CPI), underlying inflation (UND1X) and domestic underlying inflation (UNDINHX) excl. energy | |

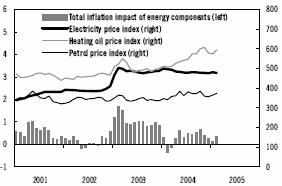

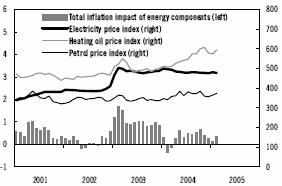

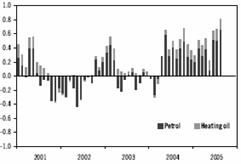

8.2 Energy consumer price indexes and total contribution from energy prices to inflation | |

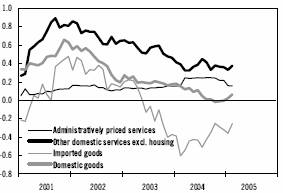

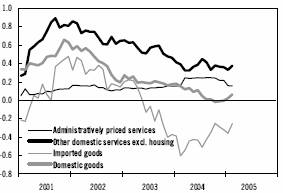

8.3 Contributions to CPI inflation from certain goods and services, excluding electricity, oil, petrol, fruit and vegetables | |

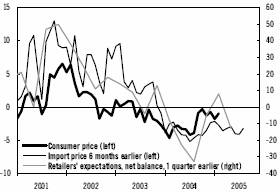

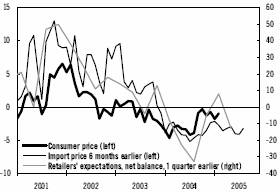

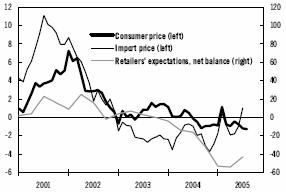

8.4 Clothing and footwear. Consumer and import prices (year-on-year change) and retailers’ consumer price expectations | |

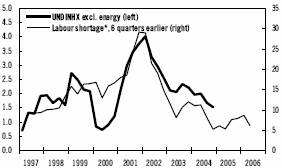

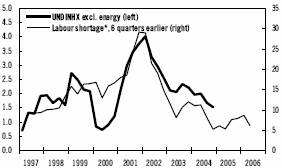

8.5 Domestic underlying inflation (UNDINHX) and labour shortage reported in the wholesale, retail and motor vehicle trades | |

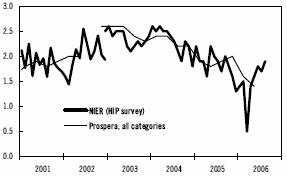

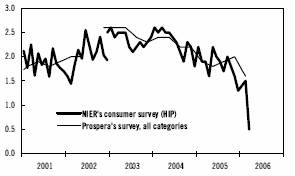

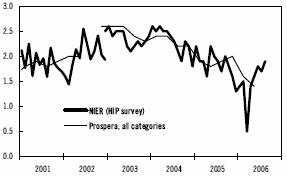

8.6 Inflation expectations, 12 month horizon | |

8.7 Consumer prices | |

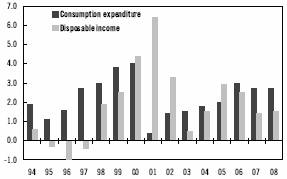

9.1 Household real disposable income | |

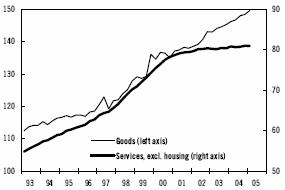

9.2 Household consumption of goods and services | |

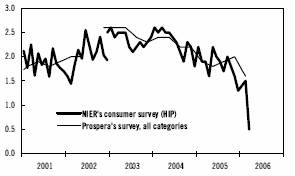

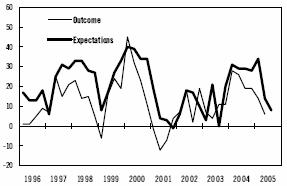

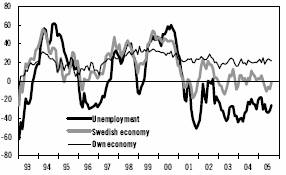

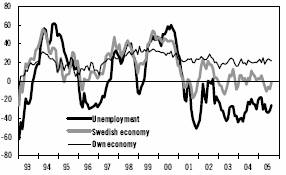

9.3 Household expectations about the economy 12 months ahead | |

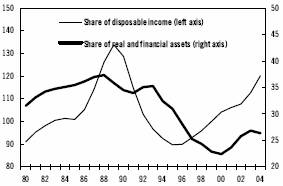

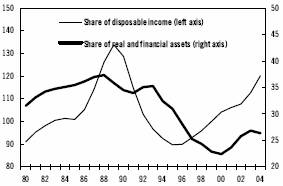

9.4 Liabilities in relation to disposable income and total assets | |

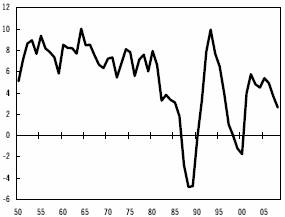

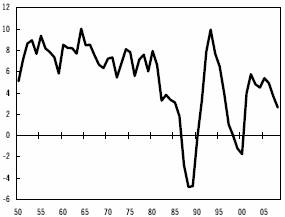

9.5 Household own saving | |

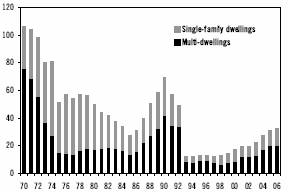

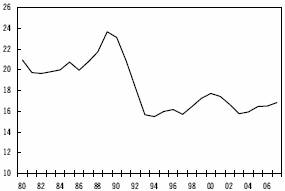

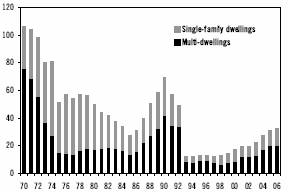

10.1 Investment | |

10.2 Investment share of GDP | |

10.3 Capacity utilisation in industry | |

10.4 New building starts | |

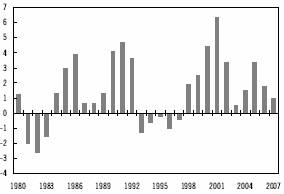

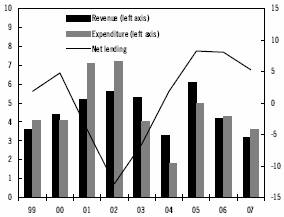

11.1 General government net financial position | |

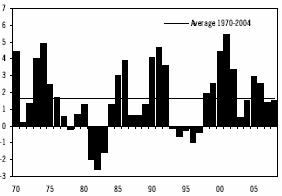

7

Sweden’s Economy

Foreword

This appendix to the 2005 Spring Fiscal Policy Bill contains the Ministry of Finance’s forecast of the development of the international and Swedish economies in 2005 and 2006. In addition, it contains an estimate of the development in 2007.

The forecast is based on data from Statistics Sweden (SCB), the European Commission and the National Institute of Economic Research (NIER). The Ministry of Finance is, however, wholly responsible for the assessments presented here. Henrik Braconier, Director at the Ministry of Finance, is responsible for the forecast. This appendix takes account of information available on 4 April.

1 Overview

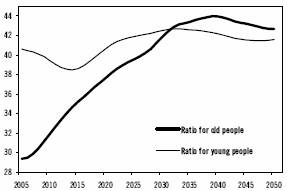

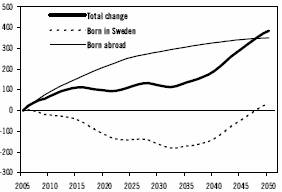

The global economy is expected to continue to grow rapidly and growth is estimated at approximately 4 per cent both this year and in 2006. Low interest rates, high corporate profits and stronger developments in the labour market result in both investment and household consumption driving global growth. Inflationary pressure is expected to continue to be subdued in the near future. The international risk assessment is, however, not balanced and the probability of weaker growth than expected is greater than the probability of stronger growth.

The Swedish economy is estimated to grow by 3.2 per cent this year. Export growth is slowing, but exports are expected to make a large contribution to GDP growth this year as well. Domestic demand will, however, play an increasingly important role for growth in 2005 and 2006. Investment, which began growing rapidly in 2004, is expected to grow at a high rate this year. Growth in household consumption is expected to increase in the near future, partly as a result of expansionary monetary and fiscal policies as well as a brightening labour market. GDP growth in 2006 is estimated at 2.7 per cent.

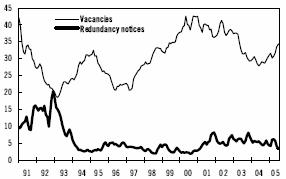

The labour market situation is gradually improving and employment is estimated to rise by 0.8 per cent this year and by 1.1 per cent in 2006. Unemployment is expected to fall gradually as a result of increased volumes of labour market policy programmes and increasingly strong economic activity. Measured as an annual average, unemployment is estimated to fall to 5.0 per cent this year and to 4.4 per cent in 2006.

Inflationary pressure in the Swedish economy continues to be low, which is partly a result of low resource utilisation. CPI inflation is estimated at an average of 0.5 per cent this year and 1.5 per cent in 2006.

Public finances continue to show a surplus. General government net lending is estimated at 0.7 per cent of GDP this year and 0.6 per cent in 2006.

1.1 International conditions

The global economy grew very rapidly in 2004 and growth is estimated to have been 4.9 per cent (see Table 1.1). Growth was strong in the majority of regions. However, growth was slow in the euro area. During the second half of 2004, growth in the global economy slowed, partly as a result of rising oil prices and a gradually less expansionary economic policy. Both underlying structural factors and forward-looking indicators, however, indicate that growth will be somewhat higher in 2005 than the second half of 2004. Overall, the global economy is estimated

9

to grow by 4.1 per cent in 2005 and 3.9 per cent in 2006.

Further oil price rises and the large current account deficit in the United States still constitute the largest threats to growth in the global economy. The risk factors are, however, considerably different in nature. The probability of higher oil prices is relatively high, while the consequences for the global economy are not likely to be too serious. The probability of financial turbulence as a result of the US current account deficit is considered to be lower, but the economic consequences may be both considerable and difficult to predict. The possible consequences for the Swedish economy of such a development are illustrated in an alternative scenario in Chapter 12. The risk of higher oil prices or financial disruption in the United States is likely to persist throughout the forecast period.

The US economy continued to grow strongly throughout 2004 and early 2005, despite the gradually less expansionary economic policy stance. Despite systematic and repeated rises, the Federal Reserve’s key rate is still at a low level, and is not expected to reach neutral levels until 2006. The reduced demand stimulus from economic policy has been balanced by increasing employment, strong growth in household wealth and continued low long-term interest rates. Consequently, the deceleration from last year’s high GDP growth of 4.4 per cent in the United States is expected to be relatively mild. Growth is estimated at 3.7 per cent this year and 3.4 per cent in 2006. The favourable growth rate has so far only led to a moderate increase in inflation. The reason for this is that productivity has continued to develop strongly and resource utilisation has therefore not risen alarmingly fast. Prices are expected to continue to rise at a balanced rate in the near future.

The export-led economic upturn, which began in the euro area during the summer of 2003, was weakened considerably during the second half of 2004. Weaker global growth – combined with the appreciation of the euro – contributed to exports slowing, and GDP grew by only 2.0 per cent. In 2005, increasing domestic demand is expected to gradually lead to stronger growth, but the growth rate is estimated at only 1.6 per cent this year, rising to 2.1 per cent in 2006. At the same time, stable high unemployment and an inflation rate that is permanently above the European Central Bank’s (ECB) target indicate that the euro area as a whole is struggling with structural problems. However, developments differ markedly between different member states, as described in Chapter 2. Growth in the neighbouring Nordic countries and the UK is expected to be favourable in the near future, which will have a favourable impact on Swedish exports. Japanese growth is also expected to accelerate gradually in 2005 and 2006.

Table 1.1 Assumptions for the forecast

| | 2003 | | 2004 | | 2005 | | 2006 | | 2007 | |

GDP, world(1) | | 3.6 | | 4.9 | | 4.1 | | 3.9 | | 3.6 | |

Brent oil, USD(2) | | 28.9 | | 39.0 | | 45.1 | | 40.6 | | 39.8 | |

TCW index(2) | | 128 | | 126 | | 122 | | 121 | | 121 | |

German long-term interest rate(3) | | 4.1 | | 4.1 | | 3.8 | | 4.1 | | 4.2 | |

Swedish long-term interest rate(3) | | 4.6 | | 4.4 | | 4.0 | | 4.3 | | 4.4 | |

Repo rate(4) | | 2.75 | | 2.00 | | 2.00 | | 2.75 | | 3.25 | |

Refi rate(5) | | 2.00 | | 2.00 | | 2.00 | | 2.50 | | 3.00 | |

Fed Funds rate(6) | | 1.00 | | 2.25 | | 3.50 | | 4.00 | | 4.50 | |

(1) Percentage change.

(2) Annual average.

(3) 10-year government bond, annual average.

(4) Final entry.

(5) Euro area key policy rate, final entry.

(6) US policy key rate, final entry.

Sources: Riksbank, Statistics Sweden and Ministry of Finance.

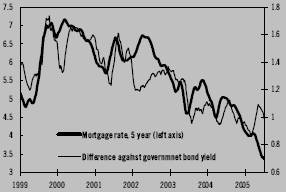

1.2 Capital markets

Over the past five years, both nominal and real market rates have fallen sharply globally. Long rates are now at historically low levels and reflect the fact that global saving has increased more rapidly than investment requirements. The relatively high saving is also reflected in a low interest rate spread between borrowers with different degrees of creditworthiness. A rise in bond rates is probable in the near future and has already begun in the United States. However, the rise is expected to be dampened by demographically determined continued high saving, and by changes in investment regulations for insurance companies and pension funds.

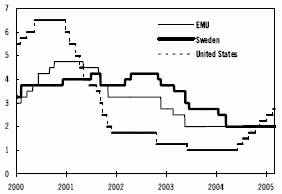

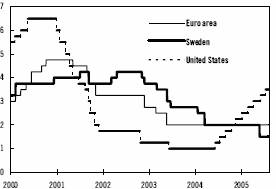

The central banks’ key rates are also at low levels. Monetary policy thus has an expansionary stance in both the United States and the euro area. In 2004 and early 2005, monetary policy was gradually tightened in the United States.

10

This trend is expected to continue in the near future, with the aim of restraining the inflation that arises as resource utilisation increases. In the euro area, key interest rates have been held at 2.00 per cent for quite some time now. Subdued economic development in the euro area indicates that interest rate rises are not to be expected in 2005. However, the ECB is expected to raise key rates gradually in 2006 as resource utilisation slowly increases.

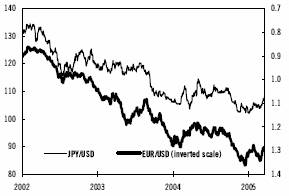

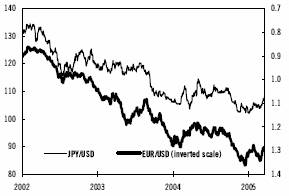

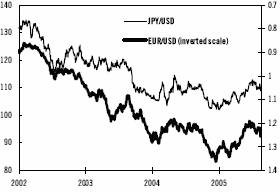

During the period January 2002 to January 2005, the US dollar weakened by 34 per cent against the euro. In early 2005, the dollar stabilised, partly supported by a rising interest-rate spread against the euro area. The large current account deficit – and to a lesser extent the budget deficit – indicates, however, that a continued weakening of the dollar is to be expected. In the forecast, some weakening of the dollar is expected in 2005 and 2006.

The same factors that indicate a continued weakening of the dollar point to a stronger Swedish krona. Large current account surpluses and sound public finances result in a gradual improvement in the net position in relation to the rest of the world. Over the past four years, the krona has also strengthened markedly in terms of the TCW index. In 2005, a continued strengthening is anticipated, albeit at a considerably slower rate. The TCW index is estimated at 121 at the end of 2005.

1.3 Economic policy

Between November 2002 and April 2004, the Riksbank lowered the repo rate by a total of 2.25 percentage points, and then held it at a low level of 2.00 per cent. The Riksbank’s monetary policy has thus had an expansionary stance since 2003 and made a positive contribution to demand in the Swedish economy in 2004 and early 2005. Since monetary policy impacts on domestic demand with a considerable time lag, it is probable, however, that the full impact of the low repo rate will not make itself felt until this year.

As a consequence of low inflationary pressure and low resource utilisation in the economy, the Riksbank is expected to hold the repo rate at 2.00 per cent throughout 2005, and then gradually raise the level to 2.75 per cent by the end of 2006. In 2007, it is expected to raise the repo rate further towards neutral levels.

Fiscal policy, measured as the change in the structural balance, was tightened equivalent to 1.0 per cent of GDP in 2004. The discretionary fiscal policy in the central government budget was weakly expansionary. However, this was more than offset by other tightening items, including raised local government taxes. Moreover, tax revenues increased as a result of some firms reversing the whole or parts of their tax allocation reserves for taxation. This year, fiscal policy is expected to have an expansionary stance equivalent to 0.9 per cent of GDP. The expansion is driven to a large extent by the discretionary policy in the central government budget. Fiscal policy is expected to have a weakly expansionary stance equivalent to 0.2 per cent of GDP in 2006, followed by a weakly contractionary stance in 2007.

Overall, economic policy is expected to have a strongly stimulating effect on demand both this year and in 2006. The effect is anticipated to decline in 2007.

1.4 Demand and output

Sweden’s GDP grew by 3.5 per cent in 2004 (see Table 1.2). The high growth was partly a result of the unusually large number of working days in 2004 compared with 2003. This calendar effect is estimated by Statistics Sweden (SCB) to have contributed 0.5 percentage points to growth in 2004. In 2005, both actual GDP growth and calendar adjusted GDP growth are estimated at 3.2 per cent. In 2006, growth is estimated at 2.7 per cent, but since there are fewer working days

Table 1.2 Selected statistics

Percentage change unless otherwise stated

| | 2003 | | 2004 | | 2005 | | 2006 | | 2007 | |

GDP | | 1.5 | | 3.5 | | 3.2 | | 2.7 | | 2.4 | |

GDP, calendar adjusted | | 1.6 | | 3.0 | | 3.2 | | 3.0 | | 2.4 | |

Open unemployment(1) | | 4.9 | | 5.5 | | 5.0 | | 4.4 | | 4.2 | |

Number of hours worked | | -1.2 | | 0.9 | | 0.6 | | 0.7 | | 0.4 | |

CPI, Dec–Dec | | 1.3 | | 0.3 | | 0.6 | | 2.0 | | 2.0 | |

General government net lending, per cent of GDP | | -0.1 | | 1.1 | | 0.7 | | 0.6 | | 1.1 | |

TCW index(2) | | 128 | | 126 | | 122 | | 121 | | 121 | |

(1) Per cent of labour force.

(2) Annual average.

Sources: Riksbank, Statistics Sweden and Ministry of Finance.

11

Table 1.3 Demand and output

| | SEK,

billion(1) | | Percentage change in volume | |

| | 2004 | | 2001 | | 2002 | | 2003 | | 2004 | | 2005 | | 2006 | | 2007 | |

Household consumption expenditure | | 1,224 | | 0.4 | | 1.4 | | 1.5 | | 1.8 | | 2.2 | | 2.7 | | 2.6 | |

General government consumption expenditure | | 706 | | 0.9 | | 2.3 | | 0.8 | | 0.3 | | 1.2 | | 0.7 | | 0.5 | |

Central government | | 197 | | -1.6 | | 3.0 | | 0.8 | | -0.5 | | 0.5 | | 0.0 | | 0.5 | |

Local government | | 509 | | 1.9 | | 2.0 | | 0.7 | | 0.5 | | 1.5 | | 1.0 | | 0.5 | |

Gross fixed capital formation | | 405 | | -1.0 | | -2.6 | | -1.5 | | 5.1 | | 7.1 | | 5.2 | | 5.1 | |

Business sector, excluding housing | | 270 | | -2.9 | | -7.1 | | -2.9 | | 4.7 | | 7.3 | | 5.6 | | 5.4 | |

Housing | | 64 | | 4.2 | | 5.7 | | 5.5 | | 16.1 | | 10.7 | | 4.7 | | 8.0 | |

Authorities | | 71 | | 4.5 | | 9.7 | | -1.3 | | -2.0 | | 2.9 | | 3.7 | | 0.8 | |

Change in stocks(2) | | 4 | | -0.5 | | -0.2 | | 0.4 | | -0.3 | | 0.4 | | -0.1 | | 0.0 | |

Exports | | 1,176 | | 0.5 | | 1.2 | | 5.0 | | 10.2 | | 6.9 | | 5.8 | | 5.7 | |

Imports | | 972 | | -2.5 | | -1.9 | | 4.9 | | 6.7 | | 7.9 | | 6.2 | | 6.4 | |

GDP | | 2,543 | | 1.0 | | 2.0 | | 1.5 | | 3.5 | (3) | 3.2 | | 2.7 | (3) | 2.4 | |

(1) Current prices.

(2) Volume change, per cent of last year’s GDP.

(3) Underlying (i.e. calendar adjusted) GDP growth is estimated at 3.0% both 2004 and 2006. The fact that actual GDP growth in 2004 was higher than the underlying growth is due to the larger number of working weekdays in 2004 compared to 2003. The fact that actual GDP growth in 2006 is lower than the underlying growth is due to the smaller number of working weekdays in 2006 compared to 2005.

Sources: Statistics Sweden and Ministry of Finance.

in 2006 than in 2005, calendar adjusted growth is estimated at 3.0 per cent. In 2007, GDP is estimated to increase by 2.4 per cent.

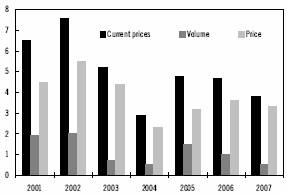

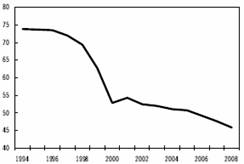

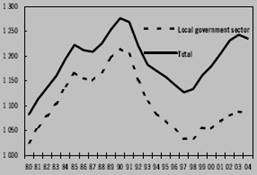

Export-driven growth in 2004

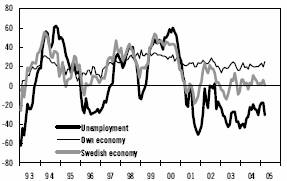

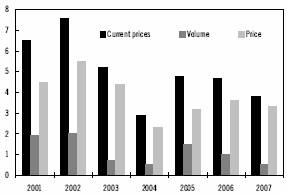

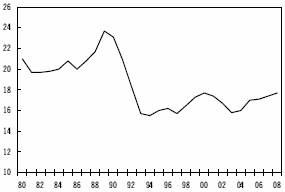

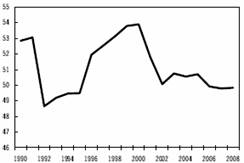

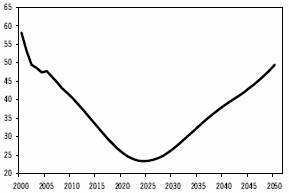

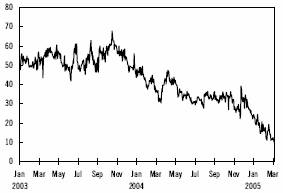

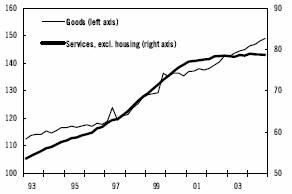

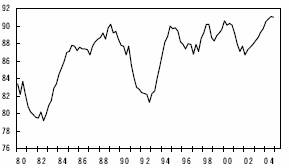

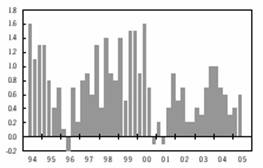

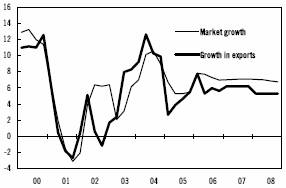

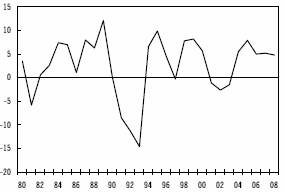

An important reason for the high GDP growth in 2004 was that Swedish exports grew by over 10 per cent, partly as a result of strong global growth (see Table 1.3). The composition of export demand was also favourable for Swedish export firms since global demand for investment goods in particular grew rapidly (see Diagram 1.1). Moreover, the telecommunication equipment industry benefited from the strong recovery in investment by telecoms operators. Exports of services also grew substantially in 2004, partly as a result of increased exports of corporate services.

One item that attracted considerable attention in 2004 was merchanting, i.e. the trade margin that arises when Swedish parent companies handle the invoicing of sales by foreign subsidiaries to a third country. According to SCB, merchanting contributed 0.4 percentage points to GDP growth in 2004.

Strong export growth contributed to a gradual broadening of the economic recovery in 2004. Fast-growing exports – combined with rising capacity utilisation in industry and low interest rates – also led to an upturn in investment, which grew by 5.1 per cent in 2004. A contributory cause of the rise in investment was the sharp increase in housing investment. The relatively subdued investment rise followed a relatively mild fall in investment during the period 2001–2003.

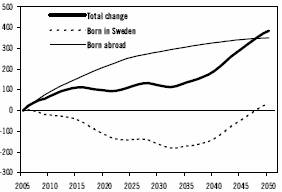

Diagram 1.1 Investment and goods exports

Percentage change in volume

Sources: Statistics Sweden, Eurostat och US Department of Commerce.

Export industry successes and gradually increasing investment in the business sector are reflected in increasing industrial output, which grew by 9.1 per cent in 2004. Even though output growth as a whole was low in the service sector in 2004, output of corporate services developed strongly and grew by 3.8 per cent. Output in the construction industry also

12

increased relatively strongly as a result of the sharp increase in housing investment.

Domestic demand becomes increasingly important

In 2005 and 2006, domestic demand is expected to increasingly drive growth. Investment, which grew rapidly in 2004, is expected to grow more rapidly in 2005. Statistics Sweden’s Investment Survey indicates that industrial investment will continue to increase in 2005. Investment plans show considerable breadth, with the pulp and paper industry, the mining industry, the chemical industry and the transport industry planning new investment. The energy sector also has major investment plans, comprising both the modernisation and upgrading of the electricity supply system, and increased output capacity. For example, Vattenfall has announced investment of just over SEK 40 billion in the energy sector in Sweden over the next few years. Housing investment is also expected to continue to grow at a good rate over the next few years. Overall, investment is expected to increase by 7.1 per cent this year and 5.2 per cent in 2006. In 2007, investment is estimated to increase by 5.1 per cent.

The destocking that took place in 2004 is considered to have led to a situation with undesirably small stocks. Consequently, increased stockbuilding is expected in 2005, which is estimated to make a contribution to GDP growth of 0.4 percentage points. However, the estimate of the contribution from stocks is highly uncertain, as it is not yet clear how the effects of the severe storm in southern Sweden in January will affect the development of stocks in the forestry sector.

Weak developments in the labour market over the past few years have created uncertainty among households, which has dampened household consumption. In 2004, consumption grew by 1.8 per cent, which was slightly more than in 2003. The NIER’s Consumer Survey showed a considerable deterioration in household expectations regarding the labour market situation in 2000 and 2001. Expectations of positive developments in the labour market did not begin strengthening until 2004, but households continue to have a pessimistic view of the labour market. Household expectations are not expected to strengthen markedly until the anticipated improvement in the labour market in 2005 is realised.

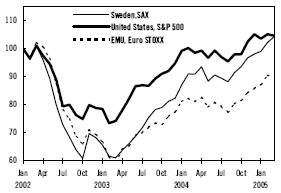

The effects of households’ negative expectations regarding the labour market are, however, balanced by the strong increase in household wealth and real income. The underlying conditions for high consumption growth have thus improved over the past few years. The financial wealth position of households has strengthened, partly as a result of the Stockholm stock exchange rising over the past two years. At the same time, households’ real assets in the form of single-family dwellings have increased sharply in value. Overall, this means that household consumption in relation to households’ net wealth is at a very low level. Moreover, household real disposable income is expected to grow in the near future and interest rates are at historically low levels.

Table 1.4 Contributions to GDP growth

Percentage points

| | 2004 | | 2005 | | 2006 | | 2007 | |

Household consumption expenditure | | 0.9 | | 1.1 | | 1.3 | | 1.2 | |

General government consumption expenditure | | 0.1 | | 0.3 | | 0.2 | | 0.1 | |

Gross fixed capital formation | | 0.8 | | 1.1 | | 0.9 | | 0.9 | |

Change in stocks | | -0.3 | | 0.4 | | -0.1 | | 0.0 | |

Net foreign trade | | 2.0 | | 0.2 | | 0.3 | | 0.2 | |

Exports | | 4.5 | | 3.2 | | 2.8 | | 2.8 | |

Imports | | -2.5 | | -3.0 | | -2.5 | | -2.6 | |

GDP | | 3.5 | | 3.2 | | 2.7 | | 2.4 | |

Sources: Statistics Sweden and Ministry of Finance.

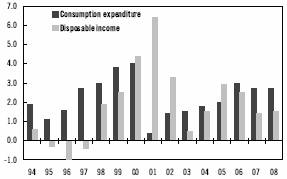

Overall, the conditions for increasing household consumption are expected to improve in 2005 and 2006. The NIER’s Consumer Confidence Indicator (CCI) and various retail indicators also point to a rise in consumption in 2005. In pace with the gradual improvement in the labour market situation, the increase in consumption is expected to accelerate in 2006. Overall, household consumption is expected to increase by 2.2 per cent this year and 2.7 per cent in 2006. In 2007, household consumption is estimated to grow by 2.6 per cent.

General government consumption grew by only 0.3 per cent in 2004. Cost-saving programmes in many municipalities and county councils resulted in local government consumption growing by a moderate 0.5 per cent in 2004. In 2005 and 2006, local

13

government revenue is, however, expected to develop favourably, partly as a result of employment support and increasing tax revenues. Local government consumption is therefore expected to grow by 1.5 per cent this year and 1.0 per cent in 2006. Central government consumption fell by 0.5 per cent in 2004. The decline was to a great extent a consequence of the reduction in purchases of defence materiel. In 2005, central government consumption is expected to grow by 0.5 per cent and then remain unchanged in 2006. Overall, general government consumption is expected to grow by 1.2 per cent in 2005 and 0.7 per cent in 2006. In 2007, general government consumption is estimated to grow by 0.5 per cent.

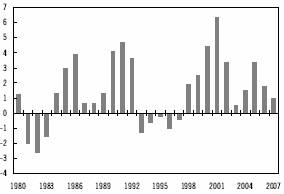

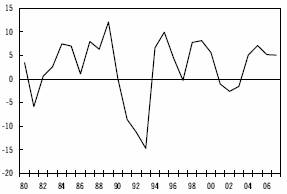

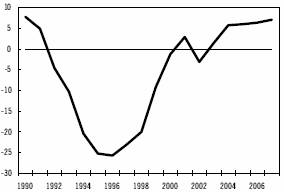

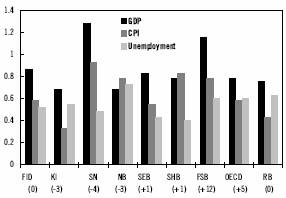

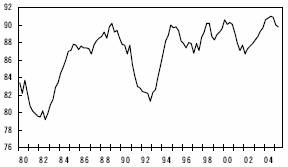

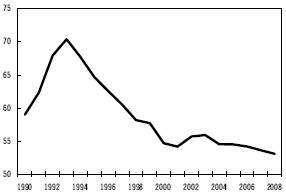

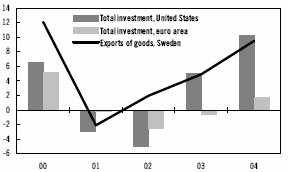

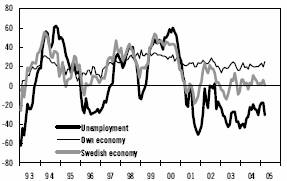

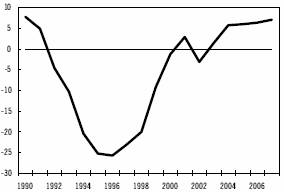

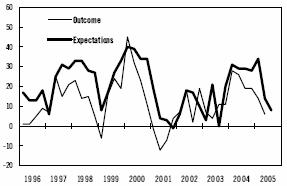

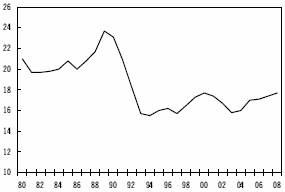

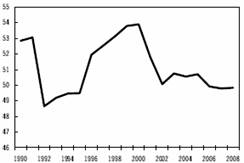

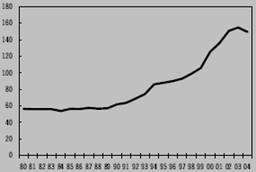

Overall, the contribution to GDP growth from total domestic demand will increase sharply in 2005 (see Diagram 1.2).

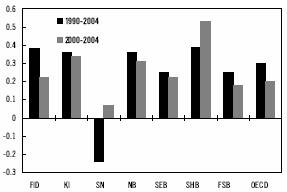

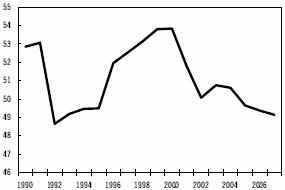

Diagram 1.2 Contributions to GDP growth

Percentage points

Sources: Statistics Sweden and Ministry of Finance.

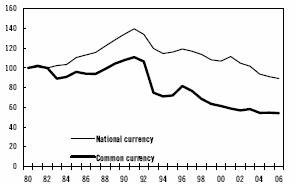

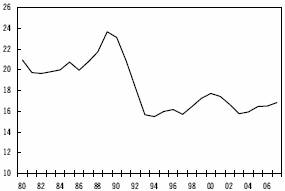

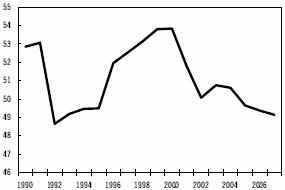

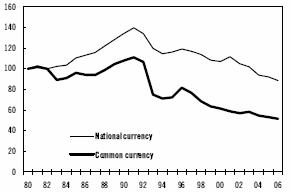

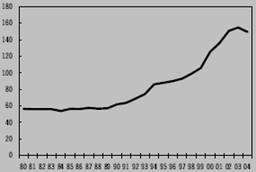

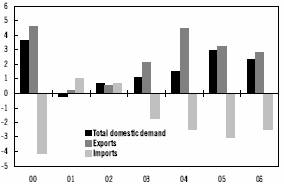

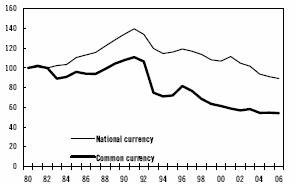

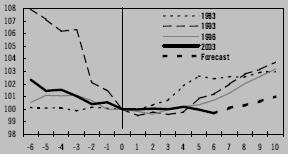

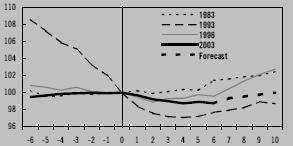

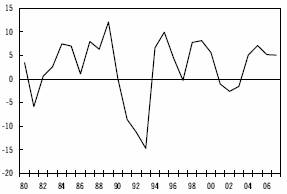

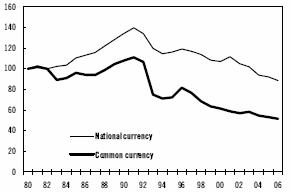

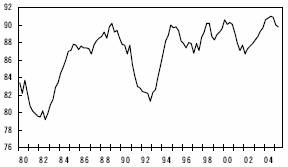

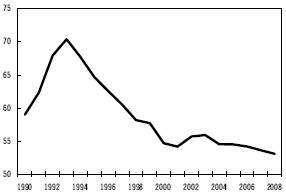

At the same time as domestic demand gradually accelerates, growth in exports, however, will slow. The strong export growth in 2004 began slowing at the end of the year. In 2005, the inflow of orders to the export industry has slowed markedly, indicating slower export growth in 2005 than 2004. Both weaker global growth and the fact that Swedish exports tend to be early in the international business cycle indicate lower export growth in the near future. While export demand is expected to develop more weakly, the conditions for continued strong export growth nevertheless seem to be favourable. Industry’s unit labour costs relative to important competing countries have – despite the krona’s appreciation in the past few years – developed favourably as a result of high productivity growth and subdued wage increases (see Diagram 1.3). In both 2005 and 2006, exports are also expected to make a larger contribution to GDP growth than total domestic demand. Overall, export growth is expected to be 6.9 per cent this year and 5.8 per cent in 2006. In 2007, exports are estimated to grow by 5.7 per cent.

Diagram 1.3 Industry’s unit labour cost in Sweden compared with 11 OECD countries, common currency (SEK)

Index (1980=100)

Sources: Statistics Sweden, National Institute of Economic Research and Ministry of Finance.

High growth drives rise in imports

In 2004, imports rose by 6.7 per cent, which is the most rapid increase since 2000. The large increase in imports was a consequence of the high growth in demand in the economy. The strong growth in import-dependent exports had a particular impact. In the near future, it is probable that the import content of exports will continue to grow as a result of the stronger krona and the continued globalisation of production.

Even though export growth is expected to slow in 2005 and 2006, imports are expected to continue developing strongly as a result of the relatively rapid growth in both investment and consumption. Among other things, Swedes’ foreign travel is expected to increase in 2005. The strong increase, which could be observed during the second half of 2004, is considered to have been interrupted only temporarily as a result of the tsunami disaster in Asia. Overall, imports are expected to rise by 7.9 per cent this year and 6.2 per cent in 2006. In 2007, imports are estimated to grow by 6.4 per cent.

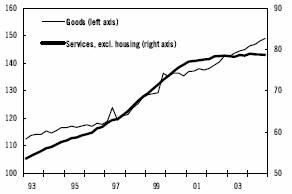

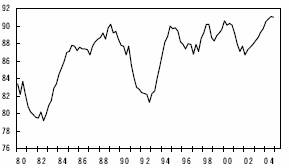

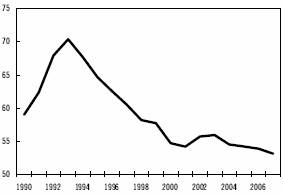

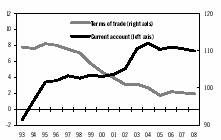

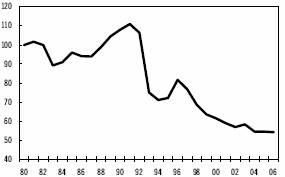

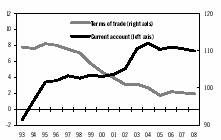

The terms of trade, i.e. export prices in relation to import prices, have developed weakly since 1995 (see Diagram 1.4). Strong Swedish productivity growth and the considerable

14

improvement in the trade balance and the current account that has taken place since the early 1990s are important reasons for this development. In 2004, the terms of trade deteriorated by 1.0 per cent, which was mainly a result of rising oil prices. In 2005 and 2006, the terms of trade are expected to strengthen somewhat, partly due to the krona appreciation being expected to have a greater impact on import prices than on export prices. Another reason is the anticipated fall in oil prices in 2005 and 2006.

Diagram 1.4 Current account and terms of trade

Note: The current account is expressed as per cent of GDP.

Sources: Riksbank, Statistics Sweden and Ministry of Finance.

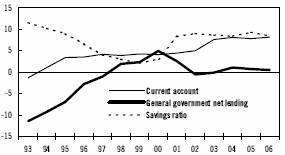

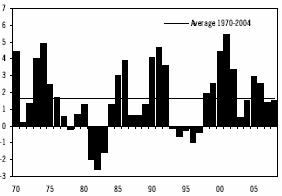

The current account surplus was SEK 206 billion in 2004, which is equivalent to 8.1 per cent of GDP. The surplus has gradually increased since the early 1990s. The demographic structure of the population has a positive impact on household saving. In addition, a number of reforms in the 1990s, such as the tax reform, the pension reform and the restructuring of public finances, have contributed to higher saving (see Diagram 1.5). At the same time, the increase in

Diagram 1.5 Current account, general government net lending and household savings ratio

Per cent

Note: Current account and general government net lending are expressed as per cent of GDP. The savings ratio is defined as household savings, including savings in supplementary pension schemes, in relation to disposable income.

Sources: Riksbank, Statistics Sweden and Ministry of Finance.

the surplus in the last few years has been driven by high export demand, subdued consumption growth and strong productivity. In 2005 and 2006, the impact of these factors is expected to decline and the current account surplus is expected to stabilise at approximately 8 per cent of GDP.

Domestic risk picture

In addition to the global risks mentioned in section 1.1, the domestic risk picture mainly comprises two alternative scenarios. On one hand, the deceleration in export growth may be stronger than expected. This risk is partly related to global growth, but the high capacity utilisation in industry may also constitute an obstacle to continued rapid export expansion. Weaker export growth means that growth is dependent on domestic demand to a greater extent. On the other hand, productivity growth may be higher than expected and the deceleration in productivity anticipated in the forecast will then take place later. Such a development involves even lower inflationary pressure and weaker developments in the labour market, leaving scope for the Riksbank to lower the repo rate.

1.5 Labour market, resource utilisation and inflation

Labour market situation beginning to improve this year

The labour market has developed weakly since 2001, with a decline in the number of hours worked. At the same time, the increase in sickness absence up to 2003 dampened the fall in employment.(1) In 2004, output in the Swedish economy rose rapidly, but unemployment nevertheless continued to rise and employment to fall. There are several reasons for the weak development in employment relative to output. Firstly, the large calendar effect in 2004 meant

(1) Sickness absence is normally included in employment as measured in the Labour Force Survey.

15

that output and the number of hours worked could increase rapidly without employment needing to rise. In addition, sickness absence began to decline, which meant that the number of hours worked could increase, without more people being employed. Finally, the continued strong productivity growth helped to dampen employment growth. Overall, employment fell by 0.5 per cent in 2004, while unemployment rose to 5.5 per cent.

In 2005, developments in the labour market are, however, expected to reverse and employment is estimated to rise by 0.8 per cent (see Table 1.5). Since the autumn of 2004, several labour market indicators have developed in an increasingly positive direction. Among other things, the number of newly reported vacancies to the National Labour Market Board has risen since November. Other factors also indicate that employment may be expected to rise in 2005. Increased domestic demand is for example expected to lead to more rapid growth in services output in the near future. In the service sector, the prospects for increasing output without employment rising are considered to be poorer than in industry as a result of weaker productivity growth.

Weak developments in the labour market have led to the government gradually increasing the volumes of labour market policy programmes. In 2003, there were 92,000 places, which increased to 106,000 places in 2004.

Table 1.5 Selected labour market statistics

| | 2003 | | 2004 | | 2005 | | 2006 | | 2007 | |

GDP(1) | | 1.5 | | 3.5 | | 3.2 | | 2.7 | | 2.4 | |

GDP, calendar adjusted(1) | | 1.6 | | 3.0 | | 3.2 | | 3.0 | | 2.4 | |

Productivity(1) | | 2.8 | | 2.8 | | 2.5 | | 1.9 | | 2.2 | |

Number of hours worked(1) | | -1.2 | | 0.9 | | 0.6 | | 0.7 | | 0.4 | |

Number of employed(1) | | -0.3 | | -0.5 | | 0.8 | | 1.1 | | 0.4 | |

Open unemployment(2) | | 4.9 | | 5.5 | | 5.0 | | 4.4 | | 4.2 | |

Labour market policy programmes(3) | | 2.1 | | 2.4 | | 2.7 | | 2.7 | | 2.4 | |

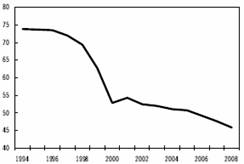

Regular employment rate(4) | | 77.6 | | 77.0 | | 76.8 | | 77.1 | | 77.3 | |

(1) Percentage change.

(2) Per cent of labour force.

(3) Number of people in labour market policy programmes, per cent of labour force.

(4) Number of employed in the age group 20-64, excluding those employed in labour market policy programmes, per cent of population 20-64.

Sources: Statistics Sweden, Arbetsmarknadsstyrelsen, Riksbank and Ministry of Finance.

The continued rising unemployment resulted in the government deciding on further measures to counteract open unemployment in the Budget Bill for 2005. An education initiative with 6,000 places for local government employees is being introduced this year. At the same time, the sabbatical year has been introduced, which is estimated to comprise 10,000 yearly places in 2005. Moreover, there is additional recruitment support comprising 10,000 places, which is announced in the Spring Fiscal Policy Bill. Overall, the number of participants in labour market policy programmes is assumed to be 121,000 this year and in 2006. The measures implemented in 2004 resulted in open unemployment starting to fall in 2004. However, the total number of unemployed people, i.e. openly unemployed people and participants in programmes, continued to rise in 2004 and amounted to 7.9 per cent of the labour force. Open unemployment was 5.5 per cent in 2004 and is expected to fall to 5.0 per cent this year and 4.4 per cent in 2006 as a result of the improved situation in the labour market and the measures announced. In 2007, unemployment is estimated to fall further to 4.2 per cent.

Resource utilisation continues to be low

Currently, there are available resources in the Swedish economy. Low resource utilisation is reflected in high unemployment, a low labour shortage and low wage and price pressure. Low resource utilisation is illustrated by the negative GDP gap, which means that the actual GDP level is less than the potential level. The GDP gap for 2004 is estimated to have been 0.9 per cent (see Table 1.6). In 2005 and 2006, the gap is expected to narrow gradually as actual GDP grows more rapidly than potential GDP. However, the GDP gap is not expected to close until 2007. The GDP gap can be broken down into a productivity gap, an average hours worked gap and an employment gap. The GDP gap for 2005 consists of an employment gap that is clearly more negative than the GDP gap, a positive productivity gap and an average hours worked gap that is close to zero. Consequently, there are estimated to be more available resources in the labour market than the GDP gap indicates for 2005, while productivity is higher than is considered sustainable in the long term. The employment gap is expected to close gradually in 2005 and 2006 as a result of employment rising more rapidly than is sustainable in the long term. At the same time,

16

actual productivity is expected to develop more slowly than potential productivity.

However, the assessment of productivity growth in the near future constitutes uncertainty in the forecast. The government has therefore commissioned the NIER to analyse in more detail the potential productivity growth in the Swedish economy.

Table 1.6 Resource situation

Per cent

| | 2004 | | 2005 | | 2006 | | 2007 | |

GDP gap | | -0.9 | | -0.3 | | -0.1 | | 0.0 | |

Employment gap | | -1.3 | | -0.9 | | -0.2 | | 0.0 | |

Productivity gap | | 0.4 | | 0.6 | | 0.1 | | 0.1 | |

Average hours worked gap | | -0.2 | | 0.0 | | -0.1 | | 0.0 | |

Note: Gaps are defined as (actual-potential)/potential.

Source: Ministry of Finance.

The downturn in 2001 made it increasingly easy for employers to recruit suitable labour. At the same time, unemployment rose and the underlying inflation rate began to fall. This trend has resulted in increasingly slow growth in wages. The wage agreements reached in 2004 were considerably lower than during previous agreement periods, which guarantees a continued weak nominal rate of wage increase. The agreements reached in early 2005 were also at levels indicating continued subdued wage growth. At the same time, real wages are growing strongly as a result of low inflation. Wages are expected to rise by 3.5 per cent in 2005 and are then assumed to rise by 3.5 per cent per year.

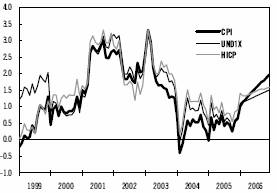

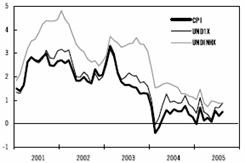

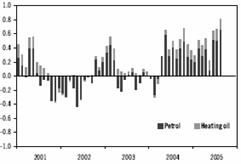

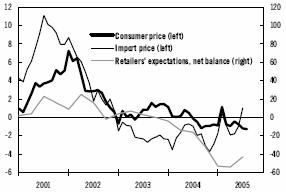

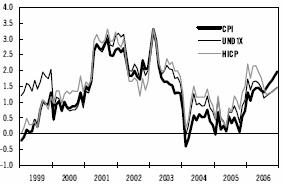

Continued low inflation

Inflation is currently very low. In 2004, consumer price inflation (CPI) was an average of 0.4 per cent, while underlying inflation (UND1X) was 0.8 per cent (see Table 1.7). The low inflationary pressure in the economy is caused by several factors. Unit labour costs have developed slowly for several years as a result of low wage increases and high productivity growth. Moreover, the weak development of demand and increased competition in, among other things, non-durables, have reduced profit margins. In addition, the contribution to inflation from imports, excluding energy, has been negative since 2003. However, the oil price rise in 2004 made a positive contribution to inflation. In 2005, changes in clothing import quotas and a further strengthening of the krona are expected to contribute to continued low imported inflation. The oil price development entails uncertainty in the inflation forecast.

Falling inflation expectations were measured in early 2005 and inflation expectations are now low. Low resource utilisation and subdued wage growth result in domestic inflationary pressure only rising slowly in the near future. Combined with low imported inflation, this results in underlying inflation (UND1X) amounting to only 0.7 per cent this year and 1.3 per cent in 2006. Consumer price inflation – which will be affected by rising interest rates on home loans in the near future – is estimated at 0.5 per cent this year and 1.5 per cent in 2006. Inflation is not expected to reach the Riksbank’s target of 2 per cent until 2007.

Table 1.7 Hourly wage, CPI and UND1X

Percentage change

| | 2003 | | 2004 | | 2005 | | 2006 | | 2007 | |

Hourly wages | | 3.5 | | 3.3 | | 3.5 | | 3.5 | | 3.5 | |

CPI, Dec-Dec | | 1.3 | | 0.3 | | 0.6 | | 2.0 | | 2.0 | |

CPI, annual average | | 1.9 | | 0.4 | | 0.5 | | 1.5 | | 2.0 | |

UND1X, Dec-Dec | | 1.6 | | 0.7 | | 0.7 | | 1.5 | | — | |

UND1X, annual average | | 2.2 | | 0.8 | | 0.7 | | 1.3 | | — | |

Sources: National Mediation Office, Statistics Sweden and Ministry of Finance.

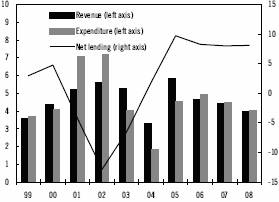

1.6 Public finances

Public finances improved considerably in 2004 for several reasons. Both local government and central government consumption developed weakly, while central government expenditure on transfer payments was lower than expected. Central government interest expenditure also declined by SEK 7 billion between 2003 and 2004. General government net lending amounted to 1.1 per cent of GDP in 2004 (see Table 1.8). The government’s target is that net lending should amount to an average of 2 per cent of GDP over an economic cycle.

Net lending is expected to decline somewhat and is estimated at 0.7 per cent of GDP in 2005 and 0.6 per cent in 2006. In 2007, net lending is estimated at 1.1 per cent of GDP. Consequently, average net lending is estimated at 1.3 per cent of GDP during the period 2000–2007. The structural balance, in which the effects of cyclical fluctuations on net lending have been eliminated,

17

is estimated at 0.9 per cent of GDP this year. In 2006 and 2007, the structural balance is estimated at 0.7 per cent and 1.1 per cent of GDP respectively.

During the forecast period, both taxes (including charges) and expenditure are expected to decline as a percentage of GDP. Overall, both the tax ratio and the expenditure ratio are expected to fall by 1.5 percentage points between 2004 and 2007.

Table 1.8 General government finances

Per cent of GDP

| | 2003 | | 2004 | | 2005 | | 2006 | | 2007 | |

Revenue | | 55.8 | | 55.6 | | 54.9 | | 54.5 | | 54.2 | |

Taxes(1) | | 50.8 | | 50.6 | | 49.7 | | 49.4 | | 49.1 | |

Expenditure | | 55.9 | | 54.5 | | 54.2 | | 53.9 | | 53.1 | |

Net lending | | -0.1 | | 1.1 | | 0.7 | | 0.6 | | 1.1 | |

Structural balance | | 0.8 | | 1.8 | | 0.9 | | 0.7 | | 1.1 | |

Consolidated gross debt | | 52.0 | | 51.2 | | 49.9 | | 48.6 | | 47.3 | |

Net debt | | -1.5 | | -5.8 | | -6.0 | | -6.4 | | -7.1 | |

(1) Including taxes to EU.

Sources: Statistics Sweden and Ministry of Finance.

General government consolidated gross debt is also expected to decline as a percentage of GDP during the forecast period, from 51.2 per cent in 2004 to 47.3 per cent in 2007.

18

2 International developments

Global GDP growth slowed in 2004. This was partially a result of high commodity prices. Despite the slowdown, the global economy is estimated to have grown by 4.9 per cent last year, which is the highest rate of growth since the 1970s. Global GDP growth is expected to enter a somewhat calmer phase this year and next. However, growth rates of around 4 per cent in both 2005 and 2006 mean that the international climate for strong Swedish exports is believed to be good.

Strong but slowing growth in 2004

The rate of growth in the global economy was very high in late 2003 and early 2004. Low interest rates (in both real and nominal terms), rising property prices and a very strong performance by many growth economies contributed to global growth of 4.9 per cent in 2004. The economic recovery spread to more regions during the year, and Asia (excluding Japan) and the United States further strengthened their positions. Latin America, the Middle East, Africa and Eastern Europe also performed well, while the euro area lagged behind and the Japanese economy stagnated. However, growth rates slowed in most regions during the course of the year as a result of high commodity prices and a return to more long-term sustainable levels of growth. Rising oil prices and strong growth have yet to trigger any appreciable increase in global inflation. Key interest rates have been raised in several countries, including the United States, Canada, Australia and the United Kingdom. This has probably kept inflation expectations in check. However, the return towards more normal interest rates is from very low levels, and so monetary policy can still be viewed as expansionary in a global perspective.

Investment growing fast

Business sector investment has been growing strongly in the biggest economic regions. This is a result of firms having consolidated their balance sheets and recorded good earnings growth, while at the same time real interest rates have remained low. The upswing in investment has been under way since 2003 in the United States and Japan, and has now spread to the euro area. Private investment is expected to be one of the main economic drivers in the United States, the euro area and Japan during the forecast period.

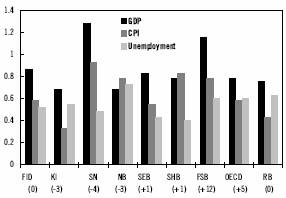

Gradually brighter labour market

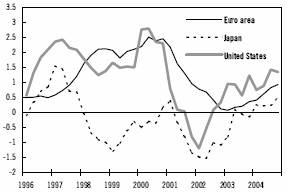

Although the economic performance of the three biggest regions – the United States, the euro area and Japan – has been relatively synchronised in recent years, developments in the labour market have differed markedly. The differences can be explained by both cyclical and structural factors.

Economic recovery began earlier in the United States than in the other regions, which explains why a recovery in employment was first seen in the United States. The more marked ups and downs in employment in the United States relative to the euro area and Japan reflect the more flexible US labour market (see Diagram 2.1 below). Compared with the euro area and Japan, US firms are probably quicker to cut back their workforce when demand falls, and therefore also to recruit again when demand picks up.

Employment growth slowed sharply at the end of 2000 in both the United States and the euro area. In the United States the number of people in employment fell for three quarters in a row, and the downturn was almost as severe as during the recession of the early 1990s. In the euro area the downturn in employment was less steep than in the United States and less severe than during the recession of the early 1990s. Employment in the United States began to pick up at the end of 2003, while the recovery in the euro area was less appreciable and arrived six months later. In Japan the labour market situation has been difficult for a long time, but it did improve last year. Employment growth was slightly positive, and unemployment fell to its lowest level for six years.

Last year unemployment amounted to 5.5 per cent in the United States and 4.7 per cent in Japan. Unemployment is expected to fall in both of these countries during the forecast period. In the euro area unemployment has held at around 8.8 per cent since mid-2003, and only a moderate decrease is anticipated in the coming years.

19

Diagram 2.1 Employment growth in the euro area, the United States and Japan

Percentage change

Source: OECD

The global risk picture

The average price of crude oil (Brent) rose by just over 30 per cent in 2004. This contributed to the slight slowdown in economic growth during the year. Higher oil prices are expected to result in slightly lower global growth during the forecast period as well. Oil prices are also a source of uncertainty in the forecast. Strong demand growth and continued geopolitical unrest, together with the associated supply disturbances, could lead to rising oil prices with negative effects on the global economy.

Besides oil prices, global imbalances present a risk in our assessment. The US current account deficit has been growing for many years, and amounted to around 6 per cent of GDP at the beginning of 2005. To date this growing deficit has been financed through strong foreign interest in investing in US assets. However, the possibility cannot be ruled out that the country’s very depressed long-term interest rates might start to rise if, for example, the Asian central banks – which have a high proportion of dollars in their currency reserves – decide to reallocate their assets in favour of other currencies. The US current account deficit has also been a contributing factor in the depreciation of the dollar in recent years. Some improvement in the US current account balance could be achieved in the short term if key Asian nations introduce more flexible exchange rates, or if public finances are tightened in the United States. In the longer term, structural reforms to boost growth in the rest of the world would have a positive impact on the US current account deficit. However, no appreciable improvement in global imbalances is anticipated during the forecast period, which means that the underlying problems remain. Should there nevertheless be a change, there is much to suggest that it would involve a sharp drop in the value of the dollar. The implications of this for the global economy are difficult to gauge (see section 12.2).

Table 2.1 GDP growth, inflation and unemployment

Percentage change

| | 2003 | | 2004 | | 2005 | | 2006 | | 2007 | |

Gross domestic product | | | | | | | | | | | |

World | | 3.6 | | 4.9 | | 4.1 | | 3.9 | | 3.6 | |

United States | | 3.0 | | 4.4 | | 3.7 | | 3.4 | | 3.3 | |

Japan | | 1.3 | | 2.6 | | 1.0 | | 1.7 | | 1.4 | |

Euro area | | 0.5 | | 2.0 | | 1.6 | | 2.1 | | 2.3 | |

Germany | | -0.1 | | 1.6 | | 1.0 | | 1.7 | | 2.2 | |

France | | 0.6 | | 2.5 | | 2.1 | | 2.0 | | 2.3 | |

Italy | | 0.4 | | 1.2 | | 1.0 | | 1.7 | | 1.9 | |

UK | | 2.2 | | 3.1 | | 2.6 | | 2.5 | | 2.7 | |

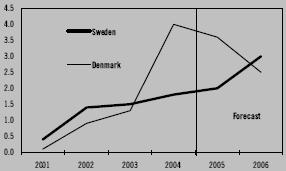

Nordic countries | | 1.0 | | 2.7 | | 2.8 | | 2.6 | | 2.4 | |

Denmark | | 0.5 | | 2.0 | | 2.3 | | 2.3 | | 2.2 | |

Finland | | 2.1 | | 3.4 | | 3.1 | | 2.7 | | 1.8 | |

Norway | | 0.4 | | 2.9 | | 3.0 | | 2.7 | | 3.3 | |

Consumer prices(1) | | | | | | | | | | | |

Euro area | | 2.1 | | 2.1 | | 1.9 | | 1.8 | | 1.8 | |

United States | | 2.3 | | 2.7 | | 2.6 | | 2.3 | | 2.3 | |

Japan | | -0.3 | | 0.0 | | 0.0 | | 0.2 | | 0.3 | |

Unemployment, per cent of labour force(2) | | | | | | | | | | | |

Euro area | | 8.9 | | 8.9 | | 9.0 | | 8.7 | | 8.6 | |

United states | | 6.0 | | 5.5 | | 5.1 | | 4.9 | | 4.7 | |

Japan | | 5.3 | | 4.7 | | 4.5 | | 4.3 | | 4.3 | |

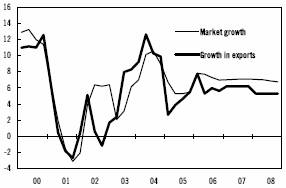

Market growth for Swedish exports | | 4.4 | | 8.3 | | 8.1 | | 7.9 | | 7.6 | |

(1) HICP for the euro area and CPI for the United States and Japan.

(2) Eurostat definition for euro area and national definition for United States and Japan.

Sources: National sources, Eurostat and Ministry of Finance.

Continued strong demand for Swedish exports

Growth in world trade probably peaked in 2004. As the global economic cycle matures and the economic policy stimulus gradually subsides, the economy is expected to enter a calmer phase. Global growth is forecast to be around 4 per cent both this year and next, which can be compared with average global growth of around 3.5 per cent over the last 20 years. Global growth of 3.6 per cent is projected for 2007. Thus the climate for continued strong Swedish export growth is expected to remain good over the next

20

few years. Swedish world market growth – growth in the trade-weighted demand for processed goods encountered by Swedish exporters – is forecast to be 8.1 per cent in 2005 and 7.9 per cent in 2006, which is slightly above the historical average. World market growth of 7.6 per cent is projected for 2007.

2.1 The euro area

Short-lived economic upswing in the euro area

During the second half of 2004 the euro area economy slowed once again. The recovery that began in mid-2003 lasted for just four quarters. The upswing was driven primarily by strong export growth. When global demand weakened in mid-2004 and the euro continued to appreciate, the export climate deteriorated significantly. GDP growth is estimated to have been 2.0 per cent last year. Looking ahead, growth is expected to be driven increasingly by rising domestic demand, and GDP is forecast to grow by 1.6 per cent this year and 2.1 per cent next year. In 2007 growth is projected to rise further to 2.3 per cent.

The euro has strengthened considerably since the beginning of 2002, above all against the dollar but also in trade-weighted terms. Since 2002 the euro has gained more than 30 per cent against the dollar and more than 15 per cent against the currencies of the euro area’s most important trading partners. The euro’s appreciation in 2004 was moderate compared with previous years. However, the overall impact of the euro’s appreciation on the export industry is probably significant, and is expected to be felt after a certain time lag. At the same time the stronger euro has resulted in considerable pressure for change, which may lead to increased competitiveness relative to the rest of the world in the longer term.

There was a clear downturn in export growth during the second half of last year as the global economy entered a calmer growth phase. The euro area therefore lost the helping hand previously lent by strong external demand. The expected transition from an export-led economic upswing to increasingly domestically generated growth did not materialise last year. Growth in household consumption remained weak, and the upswing in investment was moderate compared with previous economic recoveries.

Domestic demand to strengthen

Domestic demand is predicted to strengthen this year, above all as a result of continued recovery in investment. The situation in the labour market is expected to improve somewhat this year in the form of increased employment growth. The upswing in the number of people in employment is expected to lead to stronger consumer confidence and thus increased household consumption. Low interest rates and subdued inflation will also support a recovery in household consumption. Recent years’ marked growth in the savings ratio has also given households scope to step up consumption.

Several factors suggest a continued upswing in investment in both 2005 and 2006. Firms’ profitability has grown significantly, and firms’ financial position is believed to be very good. The previous lengthy period of dwindling investment has led to a growing need for replacement investment, and at the end of last year capacity utilisation passed the historical average.

Altogether, the euro area is expected to grow in line with its potential growth rate over the next two-year period, and thus the GDP gap will narrow only marginally by 2007.

Major growth differentials in the euro area

GDP growth in the euro area as a whole amounted to 2.0 per cent last year. If we look instead at the average rate of growth when each country is weighted equally, this figure rises to 2.7 per cent. This reflects the fact that it is mainly some of the biggest economies in the euro area that are growing slowly. The growth differentials in the euro area widened during the year, especially between the four biggest economies: Germany, France, Italy and Spain (see explanatory box at the end of this chapter).

High inflation and high unemployment

In 2004 inflation in the euro area exceeded the ECB’s inflation target for the fifth year in a row. Despite low GDP growth and high unemployment over the last four years, inflation has held

21

around a level of just over 2 per cent. To some extent the high inflation last year can be explained by temporary effects, such as rising oil prices, higher indirect taxes and increased health expenditure. Underlying inflation has also exceeded the inflation target in recent years, with the exception of the odd month here and there. This relatively high inflation suggests that there are major structural problems in the economy. However, inflation is expected to fall slightly as the effects of previous price increases drop out of the calculations. The more restrained wage settlements in most of the euro economies are also expected to help to curb inflation.

Unemployment has kept surprisingly still over the last economic cycle, and employment growth has been very depressed. Unemployment in the euro area was 8.8 per cent last year and is expected to rise to 9.0 per cent this year. Falling labour costs in most of the euro economies combined with increased domestic consumption are expected to underpin accelerating employment growth this year and lead to reduced unemployment, primarily next year.

2.2 The United Kingdom

The UK economy peaked last year with a GDP growth of 3.1 per cent. GDP is forecast to grow by 2.6 per cent this year and 2.5 per cent next year. Strong domestic demand has been the driving force behind the economic upswing, while foreign trade has made a negative contribution to growth. Household consumption is expected to slow slightly, partly as a result of the Bank of England having increased its base rate. Rising interest rates have caused the previous strong growth in property prices to slow. The accumulation of household wealth resulting from the boom in property prices is therefore slowing as well. Sluggish wage growth is also contributing to lower consumption growth.

High capacity utilisation and an improved financial position are expected to lead to continued growth in business sector investment this year and next. The UK export industry has lost market share recently, partly due to the appreciation of sterling. Sterling weakened during the second half of 2004, which is expected to strengthen the export industry somewhat, but the contribution to economic growth from foreign trade is nevertheless predicted to be negative over the next few years. CPI inflation has risen slightly since autumn 2004 and is expected to approach the 2 per cent target in 2006–2007.

2.3 The Nordic countries

In the other Nordic countries, domestic demand was the main driver behind economic growth in 2004. The contribution to GDP growth from foreign trade was modest. Household consumption was stimulated by expansionary monetary and fiscal policy. In 2005 domestic demand will continue to be the main driver behind relatively strong GDP growth in the Nordic countries.

In Finland, household consumption and investment accounted for the bulk of GDP growth in 2004. Export growth was relatively weak given the strong global economic growth. Exports picked up towards the end of 2004, and foreign trade is expected to contribute more to GDP growth this year. The relatively strong growth in investment last year, which can be explained mainly by increased investment in housing, is expected to continue in 2005. Higher interest rates will contribute to the slowing of investment growth in 2006. Household consumption is predicted to grow at a good rate during the forecast period as a result of continued expansionary fiscal policy. GDP growth is forecast to be 3.1 per cent in 2005, 2.7 per cent in 2006 and 1.8 per cent in 2007.

In Denmark too, household consumption and investment were the main drivers behind GDP growth in 2004. As a result of this strong domestic demand, imports grew very fast during the last three quarters of 2004. Meanwhile export growth was modest due to relatively weak demand from the euro area. The contribution from foreign trade was therefore negative last year, and it is expected to remain negative in 2005. The strong growth in household consumption is forecast to continue this year, but higher interest rates and neutral fiscal policy are expected to slow consumption growth in 2006. GDP growth is forecast to be 2.3 per cent in 2005, 2006 and 2007.

As a result of high real wage growth and low interest rates, household consumption in Norway increased at a relatively rapid rate in 2004. Expectations of permanently higher oil prices have led to a major increase in investment

22

in the oil sector. Growth in investment is expected to accelerate in 2005, while household consumption growth will slow slightly relative to 2004. Imports grew strongly in 2004, and export growth was moderate. The contribution to GDP growth from foreign trade is expected to remain negative throughout the forecast period. GDP is forecast to grow by 3.0 per cent this year and 2.7 per cent in 2006. Continued favourable GDP growth is also projected for 2007.

2.4 The United States

Continued strong growth

The US economy continued to perform well in 2004. GDP growth was 4.4 per cent, the highest rate seen since the late 1990s. It was primarily household consumption and business sector investment which contributed to the high rate of growth, while net exports made a negative contribution. Domestic demand had previously been stimulated by highly expansionary economic policy, but continued to grow at a good rate in 2004 despite the fiscal policy stimulus largely ebbing out. Corporate earnings are historically high, and continued good earnings expectations have contributed to strong growth in private investment. Household consumption has increased as a result of rising disposable incomes and employment. Continued low interest rates have also stimulated growth in consumption and investment.

This positive economic performance is expected to continue this year, although economic policy will gradually be tightened and the economy will enter a slightly calmer phase. GDP is expected to grow by 3.7 per cent this year and 3.4 per cent in 2006. Growth of 3.3 per cent is projected for 2007.

Domestic demand the driver

Domestic demand is expected to remain the principal driver behind the economy during the forecast period. Employment grew steadily in 2004, and the slowdown in productivity growth during the second half of the year suggests continued robust employment growth in the economy. Unemployment has fallen, and wages are expected to grow more quickly as the situation in the labour market improves further. At the same time as developments in the labour market boost disposable incomes, a move towards a more neutral monetary policy suggests increased household saving. Household wealth has improved as a result of rising equity and property prices. After weakening slightly in the autumn, consumer confidence has rallied in recent months and is now at a very high level. Altogether, the outlook is bright for continued strong growth in private consumption both this year and next.

Private investment is also expected to continue to grow at a good rate as a result of firms’ strong balance sheets and continued good earnings prospects. At the same time firms are believed to have a continuing need to invest. Rising capacity utilisation, combined with still favourable financing conditions, will contribute to strong investment growth during the forecast period. Business sector confidence is high, especially in the service sector but also in the manufacturing industry. Exports are also expected to grow more quickly as a result of the competitive edge afforded by the weaker dollar. Since import volumes are substantially higher than export volumes, net exports are nevertheless expected to continue to contribute negatively to growth.

Inflation has risen at a moderate rate despite lower productivity growth and higher energy prices. However, productivity growth slowed from very high levels and remains good. This, combined with the Federal Reserve continuing to gradually tighten monetary policy, is expected to lead to continued moderate growth in prices.

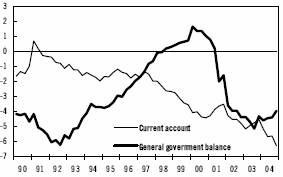

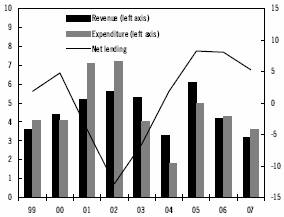

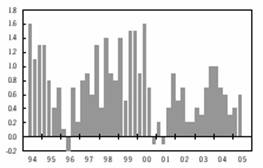

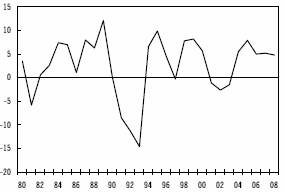

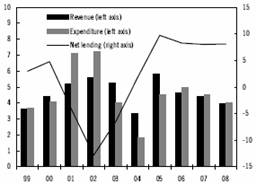

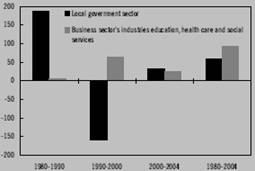

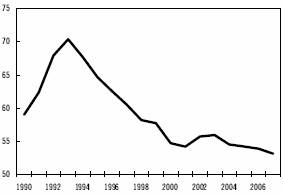

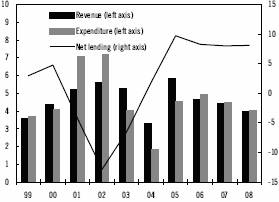

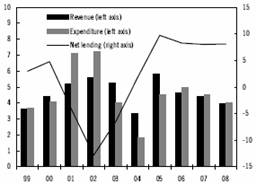

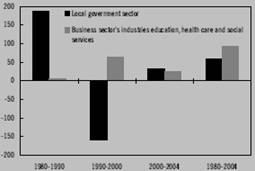

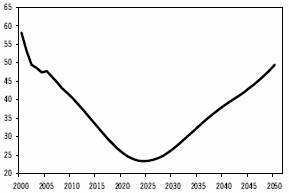

Double deficits still a risk factor

The principal risks associated with the performance of the US economy remain high oil prices and the country’s large current account and budget deficits (see Diagram 2.2). The current account deficit has been growing for many years and is expected to continue to widen during the forecast period. Should there be a decrease in the deficit, this could lead to a sharp drop in the value of the dollar and rising bond yields (see alternative scenario in Chapter 12). Further deterioration in public finances could also have negative effects on confidence, resulting in rising

23

bond yields. However, the budget deficit is expected to narrow, which will put a damper on long-term interest rates. There are also risks pulling in the opposite direction: for example, the possibility cannot be ruled out that US GDP growth might be higher than anticipated given the good state of both the household and business sectors.

Diagram 2.2 Budget balance and current account balance in the United States

Percentage change

Note: Per cent of GDP.

Source: US Department of Commerce.

2.5 Japan

Economy stagnated in 2004

Having grown strongly in late 2003 and early 2004, the Japanese economy then stagnated during the remainder of the year. The global economic slowdown undermined export growth, and the contribution from foreign trade was negative for the first time in two years. Household consumption and private investment also slowed during the year. Furthermore a change in methodology – GDP is now calculated using a chain index – resulted in lower growth both in 2004 and historically. According to the revised figures, GDP growth in 2004 was 2.6 per cent, which is 1.5 percentage points lower than estimated in the Budget Bill last autumn.

Signs of recovery in the economy

Rising oil prices and a stronger yen mean that the contributions from foreign trade and household consumption are expected to be slightly smaller this year and next than predicted in the Budget Bill.

New statistics also paint a relatively optimistic picture of developments at the beginning of 2005. The strong growth in important export markets in Asia and the United States would suggest a recovery in the manufacturing industry. Besides stronger export growth, this is expected to result in growth in private investment picking up again after slowing at the end of last year. Fundamental factors in the form of rising capacity utilisation, favourable financing options and strong earnings growth would suggest a recovery in business sector investment. Export orders have been robust in recent months, and industrial output improved at the beginning of the year after slowing during the autumn. The purchasing managers index has also strengthened in recent months after gradually weakening since the middle of last year.

Household consumption stagnated during the second half of 2004. Falling real wages and an unusually warm winter served to dampen household demand. Statistics for the start of 2005 suggest a recovery in the household sector. Household consumption expenditure, the retail trade and disposable incomes performed well at the beginning of the year. The labour market has also improved through more full-time jobs and rising bonuses. Together with continued strong confidence indicators, the latest statistics would therefore suggest a recovery in household consumption growth in the time ahead.

Consumer prices were unchanged in 2004 after more than five years of deflation. As deflation expectations have also subsided, weak growth in prices is anticipated in the coming years. However, prices are not expected to increase to an extent that any change in the country’s extremely expansionary monetary policy can be expected.

Japan’s GDP is forecast to grow by 1.0 per cent in 2005 and 1.7 per cent in 2006. Growth of 1.4 per cent is predicted for 2007, which is in line with the potential growth rate.

2.6 The rest of Asia

Strong growth in the rest of Asia

Growth in Asia excluding Japan was almost 8 per cent in 2004, the strongest rate since 1996. In China growth slowed during the second quarter

24

before picking up again during the second half of the year. Elsewhere in Asia growth slowed gradually during the course of the year, which partly reflected a return to long-term sustainable rates of growth. Meanwhile oil prices rose sharply during the autumn. Domestic demand therefore slowed in most countries in the region. In China the authorities took a number of steps to cool the investment boom, as a result of which GDP growth slowed temporarily during the second quarter of last year. Thanks to a larger relative contribution from household consumption, the economy then grew strongly again during the second half of the year. Growth over the year as a whole was 9.5 per cent.

The latest statistics for China suggest that economic activity remained high at the beginning of 2005. After slowing gradually since last spring, growth in Chinese industrial output rose in January and remained strong in February. Household consumption and, in particular, net exports also grew strongly during the first few months of this year. The larger relative contribution from household consumption, combined with the slowdown in bottleneck sectors (such as steel, cement and aluminium), means that the composition of GDP growth looks set to be somewhat more balanced this year.

Prospective indicators such as the purchasing managers index have also picked up, which suggests that the Chinese economy will continue to stimulate demand in the region.

The tsunami disaster that hit Asia at the end of 2004 is primarily an enormous human tragedy. The economic consequences for the region as a whole are probably limited. Some countries’ tourist, agricultural and fisheries industries have been hit hard, but the affected areas’ share of GDP is small.

Aggregate GDP growth for Asia excluding Japan is forecast to be 7.0 per cent in 2005 before slowing to 6.5 per cent in 2006. In 2007 growth in the region is projected to slow further to 5.5 per cent.

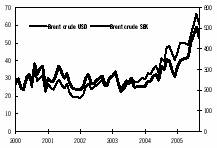

2.7 Oil prices

Since the beginning of the year the price of Brent crude has grown strongly again from around USD 40 per barrel to around USD 55 in mid-March. Unlike previous price surges over the last year, there has been no specific event behind the upswing in 2005. Continued strong demand growth has probably led to a renewed focus on the limits of existing production capacity and the risk of global shortages.

Since January the International Energy Agency has revised its forecast for global oil demand upwards, and its forecast for oil supply from non-OPEC producers slightly downwards. This means that OPEC’s importance in meeting demand has grown, at the same time as the margins between supply and demand have narrowed. Existing global capacity is probably sufficient to meet demand in the coming years, but spare capacity is in relatively short supply, and so production disturbances can be expected to have a significant impact on oil prices.

The high oil prices will probably slightly reduce demand for oil already this year, which should contribute to oil prices gradually falling back during the year. In 2006 the margin between supply and demand is expected to grow as new capacity is taken into use and growth in demand for oil is further eroded by slightly lower global economic growth, conversion to alternative energy sources and greater energy efficiency. The forecast for the price of Brent crude is USD 44 per barrel in December 2005 and USD 40 in December 2006.

25

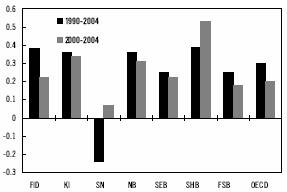

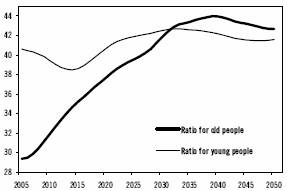

Large growth differentials in the euro area

The economy in the euro area began to slow again in mid-2004. It was the second time in less than two years that a recovery in the euro area had run out of steam before really getting going. The strong appreciation of the euro in recent years has to some extent helped to put a damper on growth in the euro area, but the main reasons for the low growth are weak domestic demand and, in particular, weak household consumption. Growth is being hampered more by domestic structural problems than by unfavourable exchange rate movements.

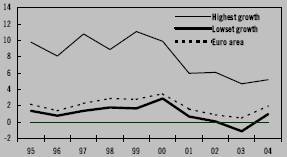

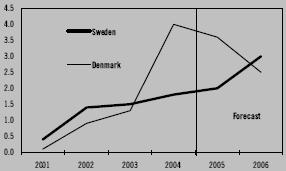

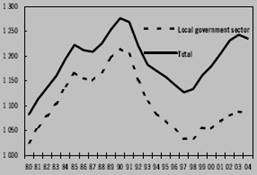

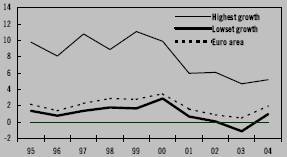

However, growth has not been weak in all of the euro economies in recent years. Some of the smaller economies – including Greece, Luxembourg, Finland and, above all, Ireland – have seen high rates of growth. Growth differentials in the euro area have narrowed since 1999. Between 1995 and 1999 the average maximum differential was just over 8 percentage points, whereas in recent years it has been around 6 percentage points (see Diagram). The decreased differentials in the euro area can to a great extent be explained by growth in Ireland having slowed significantly in recent years.

However, last year the growth differentials between the four biggest euro economies widened. Of these four, Germany and Italy have had the weakest GDP growth in recent years, while France and Spain have reported relatively high growth rates. Germany and Italy account for almost 50 per cent of the overall euro area economy, while France and Spain make up 30 per cent and the other eight countries just 20 per cent. Developments in the four largest euro economies therefore have a major impact on the euro area’s overall economic performance and so the design of monetary policy.

Average GDP growth in the euro area as a whole between 2001 and 2004 was 1.3 per cent. The average rate of growth during the same period when each country is weighted equally was 2.0 per cent. The slow-growing economies of Germany and Italy grew by an average of 0.8 per cent, while the fast-growing large economies of France and Spain grew by an average of 2.1 per cent. The other eight countries grew even more quickly: the average rate of growth in the small euro economies between 2001 and 2004 was 2.3 per cent.

This means that in recent years half of the euro area economy has grown by an average of 0.8 per cent a year while the other half has grown by an average of 2.2 per cent. The low growth in the euro area in recent years can therefore be explained to a great extent by two of the biggest economies – Germany and Italy – lagging behind the others.

The relatively large growth differentials in the euro area are also resulting in differentials in other key measures, such as inflation. Between 2001 and 2004 inflation averaged 2.0 per cent in Germany and Italy, but 2.6 per cent in France and Spain, and 2.7 per cent in the other eight euro economies. In other words, half of the euro area has had inflation rates virtually in line with the European Central Bank’s inflation target in recent years but also very low growth, while the other half has had relatively high growth but inflation well above the target rate.

Large growth differentials and inflation differentials in a currency area make it more difficult to pursue a monetary policy which is appropriate to conditions throughout the region. Few euro economies have been able to combine high growth with low inflation. Last year growth in the eight small euro economies was 3.1 per cent and inflation was 2.1 per cent. In Germany and Italy growth was 1.4 per cent and inflation 2.1 per cent, and in France and Spain growth was 2.6 per cent and inflation 2.7 per cent.

Growth differentials in the euro area

Note: The graph shows the highest and the lowest rate of growth in an individual member state for each year and the growth rate in the euro area as a whole.

Source: Eurostat.

26

3 Capital markets

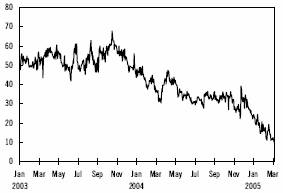

Low interest rates contribute to continued expansive global financial conditions. In the currency market, the dollar weakened to its lowest level to date in relation to the euro in late 2004 and early 2005. Even if the rising interest rate differential between the United States and the euro area temporarily buoys the dollar, factors such as the US current account deficit are expected to contribute to the continued weakening of the dollar. A general depreciation of the dollar is forecast to contribute to a stronger trade-weighted krona exchange rate. In Sweden, the Riksbank is expected to leave the key interest rate unchanged during 2005 because of low inflation and relatively weak labour market growth.

3.1 International developments

Interest rates continue to be low in the financial markets. Global financial conditions are still expansive, at the same time that the global economy is expected to enter a calmer growth phase. All factors considered, economic conditions continue to be favourable. Increased global competition and relatively high productivity growth have contributed to low inflation and low inflation expectations; consequently, central banks have been able to keep key interest rates at low levels for some time. In the future, central banks are expected to be relatively restrictive, with tightening monetary policy both in the short term and somewhat longer term.

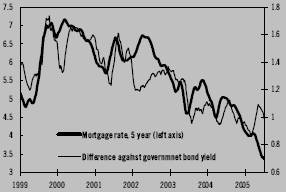

International bond yields are still at historically low levels. Bond yields are expected to rise in the future, but many factors suggest that yields will remain relatively low from a historical perspective. Structural factors such as changed investment regulations for insurance companies and pension funds are expected to further contribute to dampening the upswing for longer bond yields in Europe.

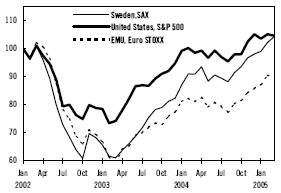

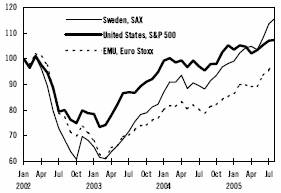

Stock markets have climbed during the beginning of 2005 in the wake of sharply rising corporate profits. Continued expansive financial conditions, growing activity in the business sector and increased dividends are expected to contribute to favourable financial conditions for firms.

The credit market has continued to move in the right direction and the differential between corporate bonds and bonds in emerging markets in relation to treasury bonds has dropped to low levels in recent years. The low interest rate differential is probably an expression of the low demand for capital. In part, firms’ indebtedness is lower because of rising corporate profits due to efficiency measures and increased income. Low yields on treasury bonds have probably also contributed to increased interest among investors for alternative investments, such as bonds in emerging markets and corporate bonds.

Rising key interest rate in the United States

The Federal Reserve began to tighten monetary policy in June 2004 and key interest rates are now at 2.75 per cent. The key interest rate is still low and monetary policy continues to be expansionary. Growth in the United States is still good, at the same time that inflation is low and demand for labour has increased. The tightening of monetary policy is expected to continue during the year as the recovery in the labour market continues and capacity utilisation increases in the US economy. Underlying inflation is expected to remain relatively low during the forecast period. The forecast for the key US interest rate is 3.50 per cent in December 2005 and 4.00 per cent in December 2006. A further tightening of monetary policy is expected during 2007.

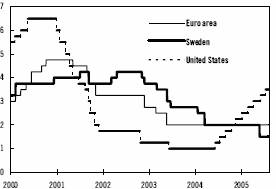

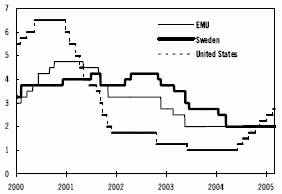

Diagram 3.1 Key interest rates in the United States, the euro area and Sweden

Per cent

Source: EcoWin.

27

US bond yields have risen since the beginning of the year, but both nominal and real bond yields are low despite good growth in the US economy. The development is similar in several other countries and can in part be an expression of global financial integration. Stable growth in the United States and increased capacity utilisation are expected to continue boosting bond yields. However, a large borrowing requirement to finance the US budget deficit could help government bond yields to rise more than what had been assumed during the forecast period. This risk is especially large if the Asian central banks should all reduce their purchases of US treasury bonds at one time. Moreover, rising inflation expectations, following the continued depreciation of the dollar, could contribute to a sharper upswing in interest rates than assumed in the forecast, which would also impact on bond yields globally. Possible consequences of such a development are illustrated in Chapter 12.

Diagram 3.2 10-year government bond yields in the United States, Germany and Sweden

Per cent

Source: EcoWin.

Interest rates in the euro area

Growth in the euro area continues to be low. The rate of wage increase has been dampened and household consumption has been restrained in recent years. All factors considered, this has helped the European Central Bank (ECB) to keep the key interest rate (refi rate) at 2.00 per cent since spring 2003, even though inflation has been over the central bank’s inflation target. However, the appreciation of the euro has caused financial conditions to tighten somewhat. Because of continued subdued growth and a decline in underlying inflation, the ECB is expected to leave the key interest rate unchanged at 2.00 per cent during 2005. A tightening of monetary policy will begin next year and in December 2006 the refi rate is expected to reach 2.50 per cent. Interest rates are expected to continue to climb during subsequent years.

European bond yields are expected to follow international movements and rise as resource utilisation increases within the euro area. However, yields in the euro area are not expected to rise as much as US yields. Structural changes in areas such as the insurance market are expected to help increase demand for long-term bonds, which will hold back interest rates somewhat.