Exhibit 99.c

Appendix 1

Sweden’s Economy

Appendix 1

Sweden’s Economy

Contents

Preface | | 9 |

| | | | |

Summary | | 9 |

| | | | |

1 | The global economy | | 11 |

| 1.1 | United States | | 12 |

| 1.2 | Euro area | | 14 |

| 1.3 | Asia | | 16 |

| 1.4 | Oil prices | | 18 |

| | | | |

2 | Financial markets | | 19 |

| 2.1 | Outside Sweden | | 19 |

| 2.2 | Sweden | | 21 |

| | | | |

3 | Swedish demand and output | | 24 |

| 3.1 | Exports | | 25 |

| 3.2 | Investment | | 27 |

| 3.3 | Stockbuilding | | 30 |

| 3.4 | Household consumption | | 31 |

| 3.5 | General government consumption | | 34 |

| 3.6 | Imports | | 35 |

| 3.7 | Output | | 37 |

| 3.8 | Current account | | 39 |

| 3.9 | GNI | | 39 |

| | | | |

4 | Labour market, wages, inflation and resource utilisation | | 43 |

| 4.1 | Labour market | | 47 |

| 4.2 | Wages | | 57 |

| 4.3 | Inflation | | 61 |

| | | | |

5 | General government sector | | 65 |

| 5.1 | General government finances | | 65 |

| 5.2 | Fiscal policy targets | | 70 |

| 5.3 | Fiscal policy | | 74 |

| 5.4 | Central government sector | | 76 |

| 5.5 | Pension system | | 78 |

| 5.6 | Local government | | 79 |

3

6 | Alternative scenarios | | 82 |

| 6.1 | Base scenario | | 82 |

| 6.2 | High-growth scenario | | 82 |

| 6.3 | Low-growth scenario | | 83 |

| | | | |

7 | Forecast evaluation | | 85 |

| 7.1 | Ministry of Finance forecasts | | 85 |

| 7.2 | Comparison with other forecasters | | 87 |

| 7.3 | Comparison with the preceding forecast | | 89 |

| | | | |

Tables Appendix | | 91 |

| Tables Chapter 1 The global economy | | 91 |

| Tables Chapter 2 Financial markets | | 92 |

| Tables Chapter 3 Swedish demand and output | | 93 |

| Tables Chapter 4 Labour market, wages, inflation and resource utilisation | | 97 |

| Tables Chapter 5 General government sector | | 99 |

| | | | |

Explanatory boxes | | |

| Revised method for calculating the wallet version of household disposable income | | 32 |

| Long-term impact of the government’s policies | | 40 |

| Potential GDP and the output gap | | 46 |

| Labour supply and employment | | 54 |

| 2007 wage round | | 58 |

4

Tables

Selected statistics | | 10 |

Table 1.1 GDP, inflation, unemployment and world market demand | | 11 |

Table 2.1 Interest and exchange rate assumptions | | 23 |

Table 3.1 Demand and output | | 24 |

Table 3.2 Exports of goods and services and change in export prices | | 26 |

Table 3.3 Investment | | 28 |

Table 3.4 Household disposable income | | 31 |

Table 3.5 Imports of goods and services and change in import prices | | 36 |

Table 3.6 Business sector output | | 37 |

Long-term impact of the government’s economic policies | | 42 |

Table 4.1 Selected statistics | | 43 |

Table 4.2 Employment trends by sector and contributions to total employment change in 2006 | | 47 |

Table 4.3 Participants in labour market policy programmes | | 48 |

Table 4.4 New start jobs | | 49 |

Central agreements and wage outcomes 2001–2006 | | 59 |

Table 4.5 Consumer prices | | 64 |

Table 5.1 General government net lending | | 65 |

Table 5.2 General government finances | | 65 |

Table 5.3 Taxes and charges | | 67 |

Table 5.4 Regulatory changes in the tax system; gross effects compared to preceding year | | 69 |

Table 5.5 General government expenditure | | 70 |

Table 5.6 Net lending in general governmnet | | 71 |

Table 5.7 Net lending: moving average for seven years excluding premium pension system | | 73 |

Table 5.8 Central government expenditure ceiling | | 74 |

Table 5.9 Indicators of stimulus to demand | | 75 |

Table 5.10 Central government finances | | 76 |

Table 5.11 Central government net lending and budget balance | | 76 |

Table 5.12 Budget balance and central government debt | | 78 |

Table 5.13 The old-age pension system | | 79 |

Table 5.14 Taxes and central government grants | | 79 |

Table 5.15 Central government grants according to the National Accounts | | 80 |

Table 5.16 Local government sector finances | | 80 |

Table 6.1 Selected statistics, base scenario | | 82 |

Table 6.2 Selected statistics, high-growth scenario | | 83 |

Table 6.3 Selected statistics, low-growth scenario | | 84 |

Table 7.1 Ministry of Finance forecasts and outcome for 2006 | | 85 |

Table 7.2 Average absolute forecast error for GDP-growth | | 88 |

Table 7.3 Ministry of Finance forecasts for 2007 in the Budget Bill for 2007 and the 2007 Spring Fiscal Policy Bill | | 90 |

GDP | | 91 |

Unemployment | | 91 |

Inflation | | 91 |

Interest and exchange rate assumptions, year-end | | 92 |

Interest and exchange rate assumptions, annual average | | 92 |

Demand and output | | 93 |

Contribution to GDP growth | | 93 |

5

Exports and imports of goods and services and change in prices | | 94 |

Gross fixed capital formation | | 94 |

Household income and savings | | 95 |

Business sector output | | 95 |

General government output | | 96 |

Current account balance | | 96 |

Components of saving | | 96 |

Gross national income (GNI) | | 96 |

General government finances | | 99 |

Central government finances | | 100 |

The old-age pension system | | 100 |

Local government finances | | 101 |

6

Figures

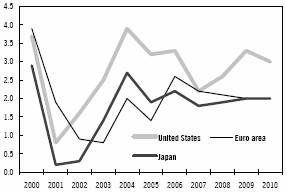

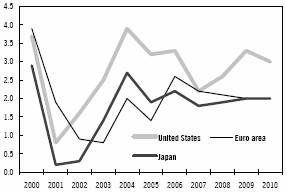

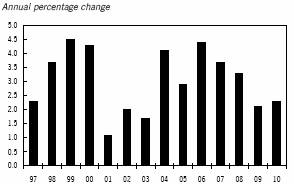

Figure 1.1 GDP-growth in key countries | | 12 |

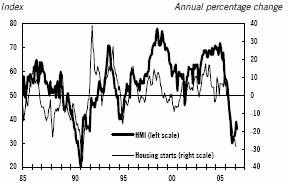

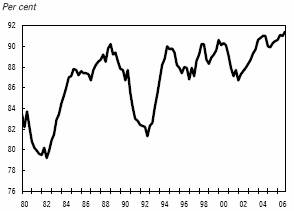

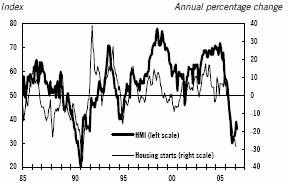

Figure 1.2 Housing starts and Housing Market Index (HMI) | | 12 |

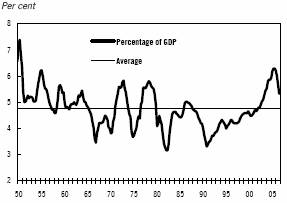

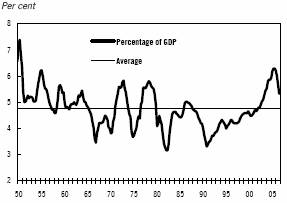

Figure 1.3 Housing investment as a percentage of GDP | | 13 |

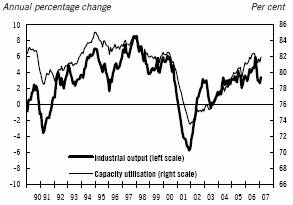

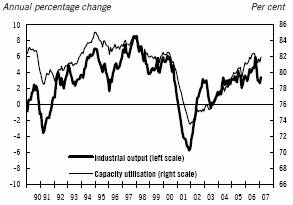

Figure 1.4 Industrial output and capacity utilisation | | 14 |

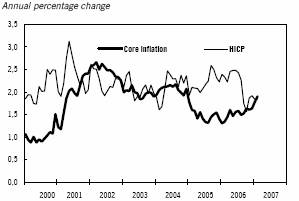

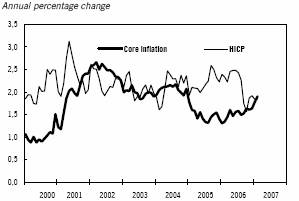

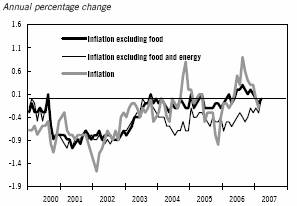

Figure 1.5 Inflation in the euro area | | 15 |

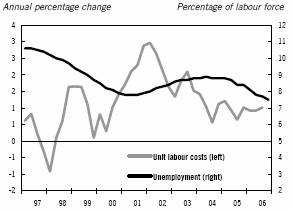

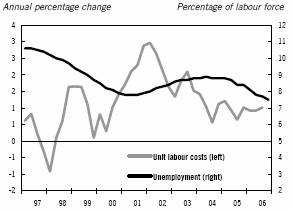

Figure 1.6 Unemployment and unit labour costs | | 16 |

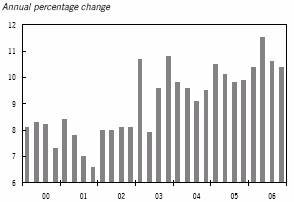

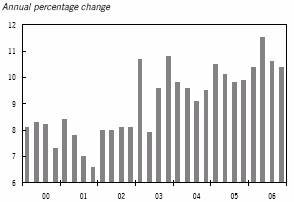

Figure 1.7 Chinese GDP growth by quarter | | 17 |

Figure 1.8 Inflation in Japan | | 18 |

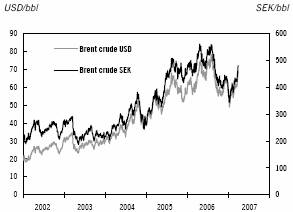

Figure 1.9 Price of Brent crude | | 18 |

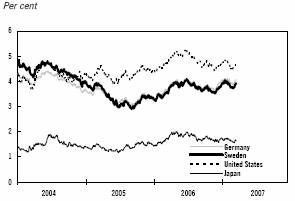

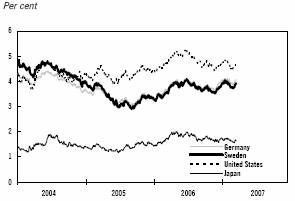

Figure 2.1 Ten-year bond yields in Germany, the United States, Japan and Sweden | | 19 |

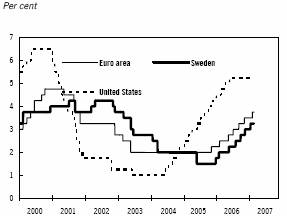

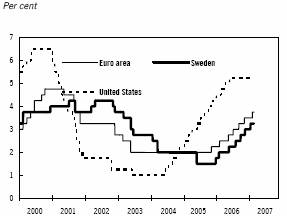

Figure 2.2 Key interest rates in the euro area, Sweden and the United States | | 20 |

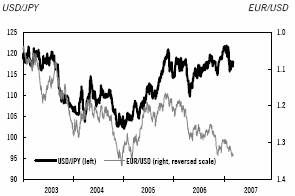

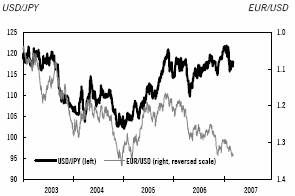

Figure 2.3 U.S. dollar against the yen and euro | | 20 |

Figure 2.4 Equity market performance in the euro area, the United States, Japan and Sweden | | 21 |

Figure 2.5 Spread between ten-year bond yields in Sweden and Germany | | 21 |

Figure 2.6 Repo rate and uncertainty range | | 22 |

Figure 2.7 TCW exchange-rate index | | 22 |

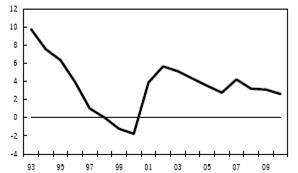

Figure 3.1 GDP | | 24 |

Figure 3.2 World market growth and growth in Swedish exports | | 25 |

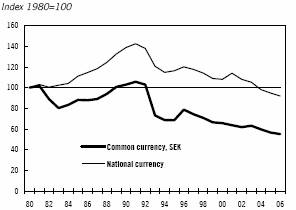

Figure 3.3 Unit labour cost in Swedish industry compared to 14 OECD countries | | 26 |

Figure 3.4 Investment | | 27 |

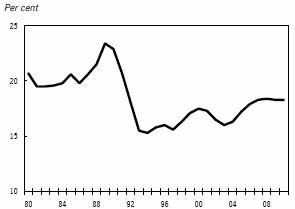

Figure 3.5 Investment as a percentage of GDP | | 27 |

Figure 3.6 Capacity utilisation in the industrial sector | | 27 |

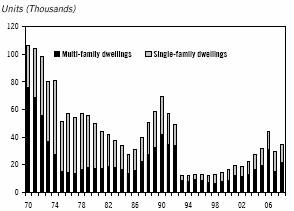

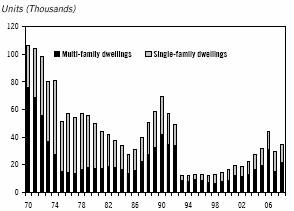

Figure 3.7 Housing starts | | 29 |

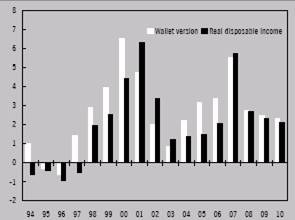

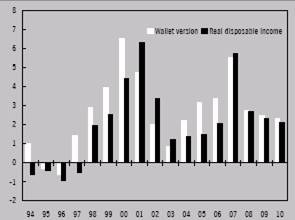

Real disposable income – National Accounts vs. the wallet version | | 32 |

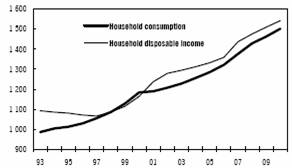

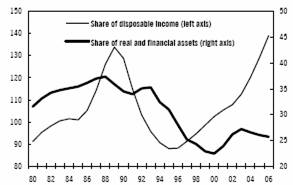

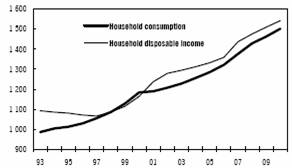

Figure 3.8 Household disposable income and consumption | | 33 |

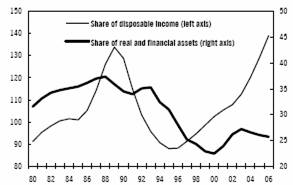

Figure 3.9 Household debt | | 33 |

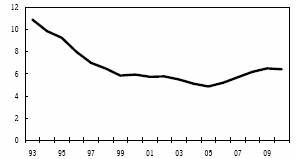

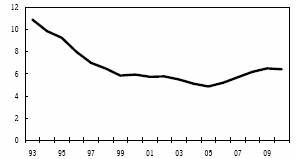

Figure 3.10 Household interest expenditure | | 33 |

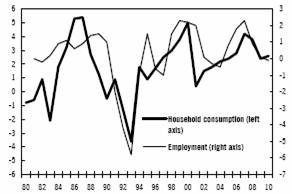

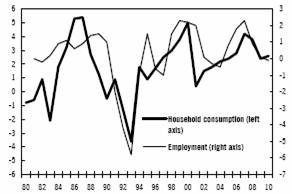

Figure 3.11 Employment and household consumption | | 34 |

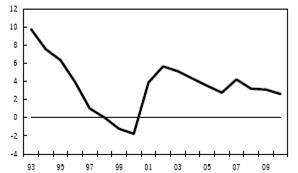

Figure 3.12 Household saving | | 34 |

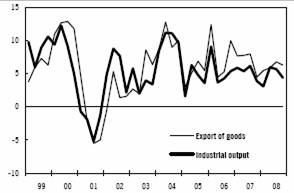

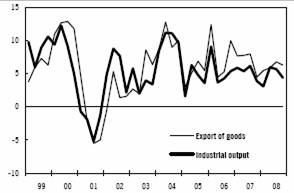

Figure 3.13 Industrial output and exports of goods | | 37 |

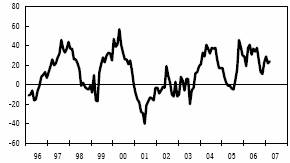

Figure 3.14 Inflow of new orders from the export market to the manufacturing industry | | 37 |

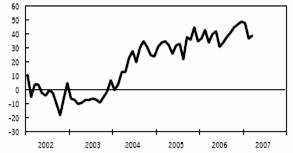

Figure 3.15 Demand for private services | | 38 |

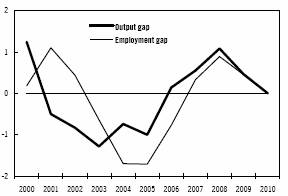

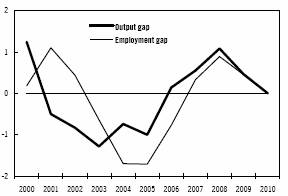

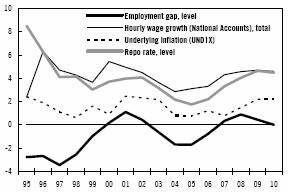

Figure 4.1 Output gap and employment gap | | 44 |

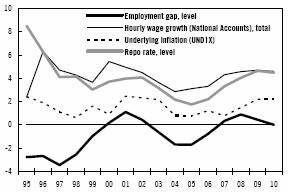

Figure 4.2 Employment gap, wage growth, inflation and repo rate | | 45 |

Figure 4.3 Participants in labour market policy programmes | | 48 |

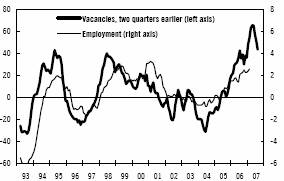

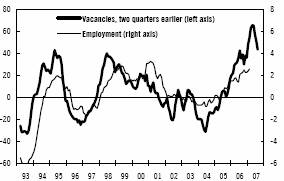

Figure 4.4 Newly reported vacancies and employment | | 49 |

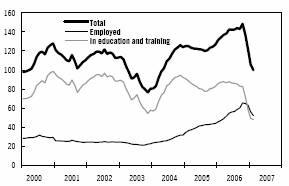

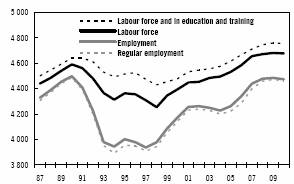

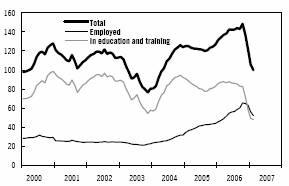

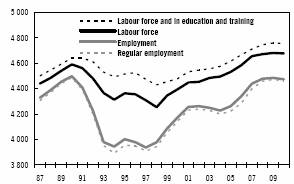

Figure 4.5 Employment and people in the labour force | | 50 |

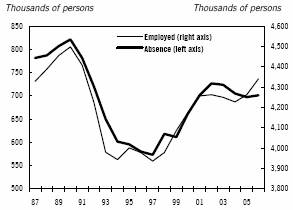

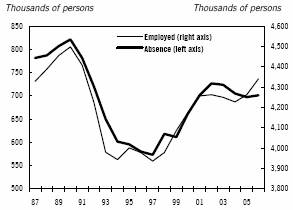

Figure 4.6 Absence and employment | | 51 |

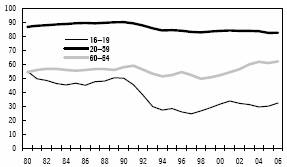

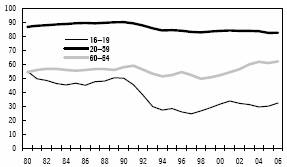

Figure 4.7 Labour participation by age group | | 52 |

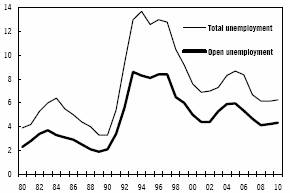

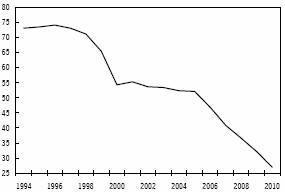

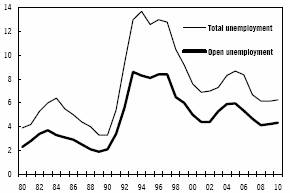

Figure 4.8 Open and total unemployment | | 53 |

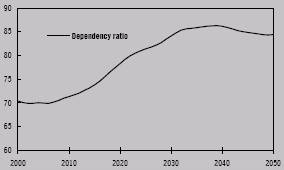

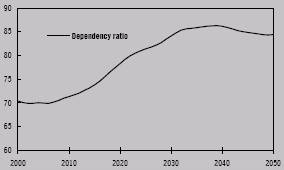

Demographic dependency ratio | | 54 |

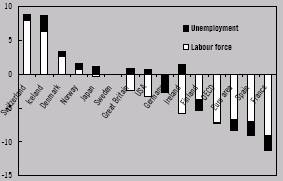

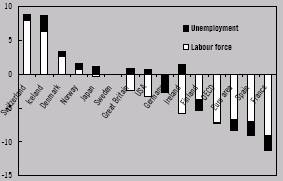

Contributions to employment rate variations among selected OECD countries compared to Sweden, 2005 | | 54 |

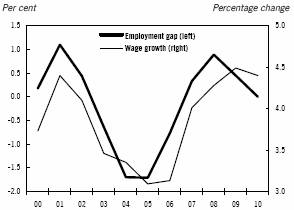

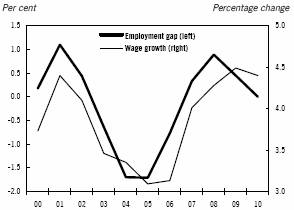

Figure 4.9 Employment gap and wage growth | | 57 |

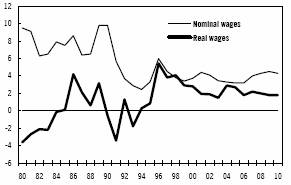

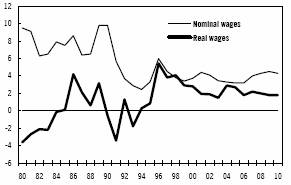

Figure 4.10 Nominal and real wage growth | | 57 |

7

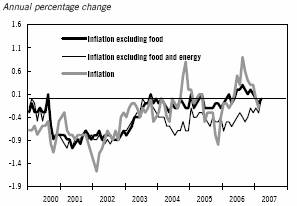

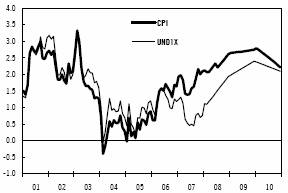

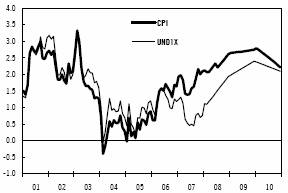

Figure 4.11 Consumer prices | | 61 |

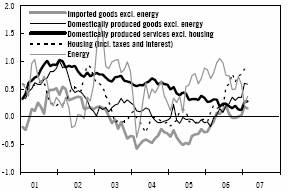

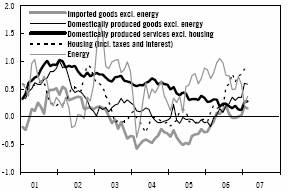

Figure 4.12 Effects on CPI inflation of prices for various goods and services | | 61 |

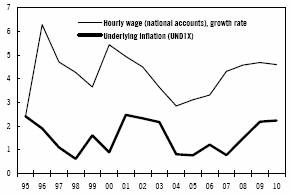

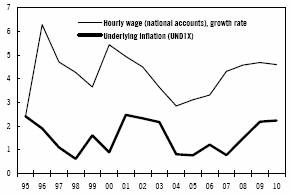

Figure 4.13 Hourly wage and inflation | | 62 |

Figure 4.14 Exchange rate and imported inflation | | 62 |

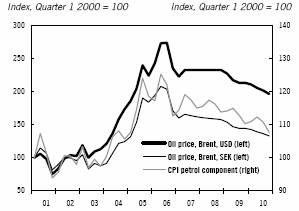

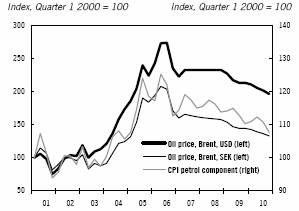

Figure 4.15 Oil price in USD and SEK and petrol in the CPI | | 63 |

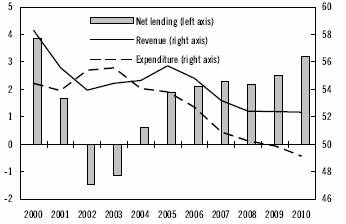

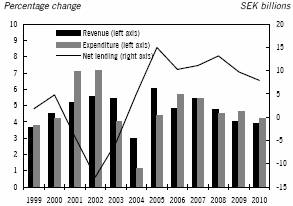

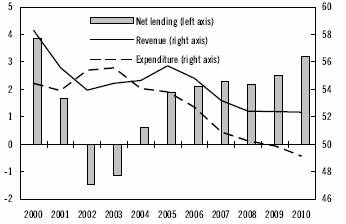

Figure 5.1 Net lending, revenue and expenditure | | 65 |

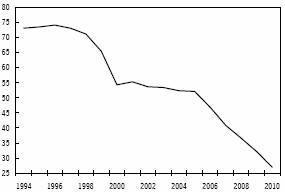

Figure 5.2 Consolidated gross debt | | 67 |

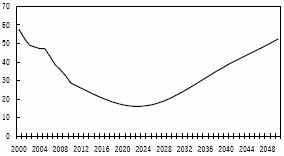

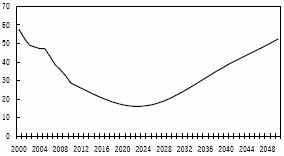

Figure 5.3 Central government debt 2000—2050, excluding proceeds from sales | | 71 |

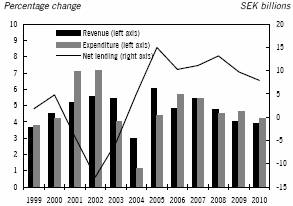

Figure 5.4 Local government sector finances | | 81 |

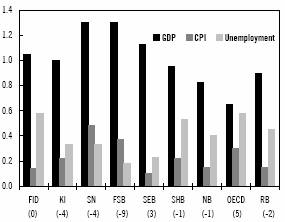

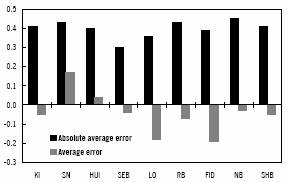

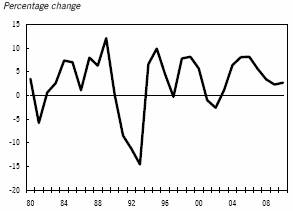

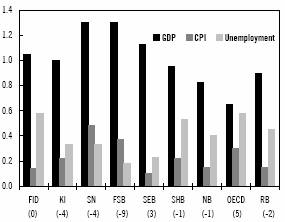

Figure 7.1 Average absolute forecast errors for 2006 | | 87 |

Figure 7.2 Average absolute forecast errors related to GDP | | 88 |

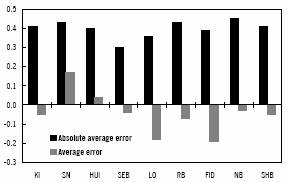

Figure 7.3 Average absolute errors and average errors for unemployment 1997–2006 | | 89 |

8

Preface

This appendix to the 2007 Spring Fiscal Policy Bill presents the Ministry of Finance’s global and Swedish economic forecast for 2007 and 2008, as well as an estimate for 2009 and 2010 based on the assessed level of resource utilisation and potential economic growth.

The forecast is based on data from institutions such as Statistics Sweden (SCB), the European Commission and the Swedish National Institute of Economic Research (NIER). The Ministry of Finance has full responsibility for the assessments presented here. Henrik Braconier, director at the Ministry of Finance, is responsible for the calculations. The appendix proceeds from information available on 29 March 2007. The announced inquiry concerning repeal of the property tax has not been taken into consideration.

Summary

Fuelled by several years of expansionary monetary policy in the OECD area and historically low long-term interest rates, the global economy has grown rapidly in recent years. Although monetary policy has gradually tightened, the low rates are still contributing to rising demand. Global economic growth is expected to slow down in 2007 and 2008 but remain brisk. Continued labour market strength is setting the stage for rapid increases in household consumption. But global investment growth is likely to decelerate. Despite a long period of strong economic growth, global inflation has been modest and is expected to remain so in the next few years.

Rapidly rising demand in the United States over the past three years has accounted for a considerable share of global economic growth. While U.S. economic growth is set to taper off in 2007, steady ongoing growth in Asia and Europe should cushion the impact. But if the U.S. housing market declines further and has ripple effects, global economic growth may be less vigorous than anticipated by this forecast. The alternative scenario presented in Chapter 6 illustrates how a steeper economic downturn in the United States would affect the Swedish economy.

The Swedish economy is growing rapidly for the fourth consecutive year. Economic conditions are favourable, while both domestic and foreign demand for Swedish goods and services is rising steadily. In 2007 and 2008, the business cycle is expected to enter a more mature phase and exports are likely to increase more gradually. Owing partly to rapid expansion of output capacity over the past few years, investment growth is also set to slow down somewhat. Housing investment is projected to level out at a high plateau in the next few years.

Meanwhile, household consumption is set to increase very rapidly in the next few years as the result of a solid wealth position, rising real wages and robust employment growth, as well as the significant tax cuts that have been adopted and announced. Partly due to the fact that local government finances are sounder than they have been for a long time, general government consumption should also increase substantially in 2007 and 2008.

Given brisk demand growth and a stronger Swedish krona, imports are likely to increase at a steady pace in 2007 and 2008. GDP is forecast to rise by 3.7 per cent this year and 3.3 per cent next year. Calendar-adjusted GDP growth, which excludes the impact of the number of working days, is expected to be 3.9 per cent in 2007 and 3.2 per cent in 2008. Due to a high level of resource utilisation, actual GDP growth is projected to slow to 2.1 per cent in 2009 and 2.3 per cent in 2010.

Employment has been recovering steadily since Sweden’s robust economic growth caused a turnaround in the labour market in 2005. Continuation of rapid demand growth in Sweden will pave the way for rising employment in 2007 and 2008 as well. The cyclical labour market recovery has boosted labour supply. The measures that the government has already adopted to stimulate labour supply, combined with the reforms announced in this bill, should contribute to a steady expansion of supply during the period 2007–2008. Expanding labour supply is essential in order achieve a sustainable increase in the level of regular employment. The alternative scenario presented in Chapter 6 assumes that the reforms to increase labour supply will have a considerably greater impact than anticipated by this forecast. The scenario illustrates how structural reforms can generate economic growth, employment and stronger public finances.

9

Notwithstanding the forecast expansion of labour supply, brisk employment growth should lead to rapid resource utilisation increases in the total economy. Particularly in view of considerable uncertainty about the economic impact of the government’s supply-stimulating policies, projecting resource utilisation is a difficult task. If labour supply does not expand faster than this forecast anticipates and demand continues to exhibit strong growth, the economy may be in danger of overheating during the next few years. A number of indicators suggest that the Swedish business cycle is in a phase at which wage and price increases will begin to accelerate. The incipient manpower shortage makes it even more important to stimulate labour supply.

Despite the rapid expansion of labour supply, strong employment growth in 2006 led to lower unemployment. Open unemployment is expected to decline further in 2007 and 2008. Total unemployment, which also includes people participating in labour market policy programmes, is set to decrease substantially in both 2007 and 2008. Employment is expected to grow slower in 2009 and 2010 in the wake of a high level of resource utilisation, while open unemployment remains at just above 4 per cent. The regular employment rate is projected to rise throughout the forecast period and reach 75.6 per cent for the 16–64 age group in 2010.

General government finances have strengthened in the past few years. Excluding premium pension savings, general government net lending was 2.1 per cent of GDP in 2006. Steady economic growth provides the fiscal latitude to adopt tax cuts and other reforms without leaving public finances weaker than 2006. Tax cuts previously adopted and currently proposed will substantially reduce tax receipts as a percentage of GDP. Because expenditures will decrease by the same approximate percentage, general government net lending will remain virtually unchanged at just over 2 per cent of GDP in 2007–2008. In 2009–2010 general government net lending will strengthen gradually. The surpluses should continue to bolster the general government sector’s financial position. Moreover, gross debt will shrink as a result of the planned divestments of state shareholdings. Consolidated gross debt is projected at 27.0 per cent of GDP in 2010.

Selected statistics

Percentage change, unless otherwise stated

| | 2006 | | 2007 | | 2008 | | 2009 | | 2010 | |

GDP | | 4.4 | | 3.7 | | 3.3 | | 2.1 | | 2.3 | |

GDP, calendar adjusted | | 4.7 | | 3.9 | | 3.2 | | 2.1 | | 2.0 | |

Number of employed | | 1.8 | | 2.3 | | 0.9 | | 0.1 | | -0.1 | |

Regular employment rate, 16-64 years(1) | | 73.5 | | 75.0 | | 75.6 | | 75.7 | | 75.6 | |

Regular employment rate, 20-64 years(1) | | 77.7 | | 79.4 | | 80.2 | | 80.3 | | 80.1 | |

Open unemployment(2) | | 5.4 | | 4.7 | | 4.1 | | 4.2 | | 4.2 | |

Total unemployment(2),(3) | | 8.4 | | 6.7 | | 6.2 | | 6.1 | | 6.2 | |

Labour market policy programmes(4) | | 138 | | 95 | | 95 | | 90 | | 90 | |

Wage growth(5) | | 3.1 | | 4.0 | | 4.3 | | 4.5 | | 4.4 | |

UND1X, yearly average | | 1.2 | | 0.8 | | 1.5 | | 2.2 | | 2.2 | |

CPI, yearly average | | 1.4 | | 1.8 | | 2.3 | | 2.7 | | 2.5 | |

General government net lending(6),(7) | | 2.1 | | 2.3 | | 2.2 | | 2.5 | | 3.2 | |

Taxes and charges(6),(8) | | 49.8 | | 47.7 | | 47.2 | | 47.3 | | 47.3 | |

General government expenditure(6) | | 52.7 | | 50.9 | | 50.3 | | 49.9 | | 49.1 | |

Consolidated gross debt(6) | | 46.9 | | 40.9 | | 36.6 | | 32.2 | | 27.0 | |

(1) Number of employed in the age group, excluding employed in labour market policy programmes, as per cent of population in the age group.

(2) Per cent of labour force.

(3) Number of people in open unemployment and in labour market policy programmes.

(4) Number of people in labour market policy programmes, thousands.

(5) Short-term wage statistics.

(6) Per cent of GDP.

(7) Excluding premium pension savings.

(8) Including taxes to EU.

Sources: Statistics Sweden, National Labour Market Board, National Mediation Office and Ministry of Finance.

10

1 The global economy

Robust global growth

World GDP grew by an estimated 5.2 per cent in 2006. From an historical perspective, the global economy has grown very quickly for four consecutive years. While global growth is expected to weaken somewhat in the next two years, a number of indicators point to only a modest slowdown to 4.6 per cent in 2007 and 4.5 per cent in 2008. Due primarily to a recovery in the United States, global growth is likely to accelerate somewhat to 4.7 per cent in 2009, followed by 4.5 per cent in 2010.

Investment activity will taper off

The global economy is still exhibiting moderate inflation, high corporate profits and historically low bond yields. Modest inflation expectations and low interest rates are paving the way for investment activity to remain brisk. However, investment activity is expected to taper off somewhat after several years at a high level.

Table 1.1 GDP, inflation, unemployment and world market demand

Percentage change, unless otherwise stated

| | 2006 | | 2007 | | 2008 | | 2009 | | 2010 | |

GDP | | | | | | | | | | | |

World | | 5.2 | | 4.6 | | 4.5 | | 4.7 | | 4.5 | |

United States | | 3.3 | | 2.2 | | 2.6 | | 3.3 | | 3.0 | |

Japan | | 2.2 | | 1.8 | | 1.9 | | 2.0 | | 2.0 | |

Euro area | | 2.6 | | 2.2 | | 2.1 | | 2.0 | | 2.0 | |

CPI(1) | | | | | | | | | | | |

United States | | 3.2 | | 1.8 | | 2.6 | | 2.8 | | 2.9 | |

Japan | | 0.2 | | 0.6 | | 0.9 | | 1.2 | | 1.5 | |

Euro area | | 2.2 | | 2.0 | | 2.0 | | 1.9 | | 1.9 | |

Unemployment, percentage of labour force(2) | | | | | | | | | | | |

United States | | 4.6 | | 4.8 | | 5.3 | | 5.2 | | 5.1 | |

Japan | | 4.1 | | 3.9 | | 3.7 | | 3.7 | | 3.7 | |

Euro area | | 7.9 | | 7.4 | | 7.4 | | 7.5 | | 7.5 | |

World market demand(3) | | 9.8 | | 6.3 | | 6.4 | | 7.0 | | 6.9 | |

(1) HICP for the euro area and CPI for the United States and Japan.

(2) Eurostat definition for euro area and national definition for the United States and Japan.

(3) World market demand measures the weighted import demand in all countries to which Sweden exports.

Sources: National sources, Eurostat and Ministry of Finance.

Buoyed by a brighter outlook for the labour market, consumption is expected to grow steadily in 2007 and 2008. Unemployment in both the United States and the euro area is as low as it was around 2000. The oil price decline in autumn 2006 has provided additional latitude for household consumption.

Soft landing in the United States

The cooling U.S. housing market in autumn 2006 led to rapidly falling housing investments, significantly restraining GDP growth in the latter half of the year. But spurred by favourable labour market trends and falling oil prices, household consumption remains solid. Ripple effects from the housing market to other economic sectors have been limited so far.

As unemployment rises in the wake of lower gross fixed capital formation, the weaker housing market is likely to have a greater impact on household consumption. But the economic slowdown is forecast to be temporary. Most of the correction in the housing market should be over sometime in 2008. As the impact of lower gross capital formation in housing subsides in 2008, the U.S. economy is expected to recover.

Growth in the euro area and Asia will decelerate

The slowdown of the U.S. economy is likely to have relatively few repercussions on the rest of the world. As opposed to the global economic downturn around 2000, more modest growth in the United States is the result of specific domestic factors that have relatively little impact on imports. The danger of ripple effects in terms of reduced lending and rising risk premiums appears to be limited.

Both the euro area and Asia have been resistant so far – they are expected to grow above trend in both 2007 and 2008. But the slowdown in the United States and weaker investment activity are forecast to moderate growth, which will be fuelled more by domestic consumption, in those two regions. Lower household saving and a significantly better labour market are set to stimulate euro area consumption in both 2007 and 2008. While Asian growth has been largely driven by rapidly increasing exports, the trend

11

toward greater dependence on domestic demand is likely to continue in 2007 and 2008.

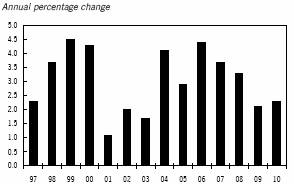

Figure 1.1 GDP-growth in key countries

Annual percentage charge

Sources: National sources, Eurostat and Ministry of Finance.

Global risk outlook

Although the base scenario is for a soft landing of the global economy, the downside risks are considerable. Among the primary risks in this forecast is the slowdown in the United States. If the correction in the housing market is more pronounced than anticipated, the ripple effects on the rest of the economy will be more evident as well. The result would be substantially slower growth in the United States and thereby the possibility of a palpable impact on the global economy.

Other risks are associated more with financial markets. Low nominal interest rates have led to a significant upswing in capital asset prices and rapidly expanding credit. A quick correction could have major repercussions on the real economy of every region.

Particularly in combination with rising oil prices, mounting labour costs in the wake of a tighter labour market and a higher level of resource utilisation could substantially increase inflationary pressure. A poorer economic growth outlook and the need for tighter monetary policies would result.

While the risk is small, an abrupt correction in the international trade and current account imbalances would significantly affect the global economy.

1.1 United States

Declining housing investment restraining economic growth

Thanks to strong ongoing consumption growth and solid increases in the machinery investment, U.S. GDP rose by 3.3 per cent in 2006. But the slowdown in the housing market gradually moderated GDP growth during the year. Housing investment made a negative contribution to GDP growth in 2006. The weak housing market and its ripple effects on other economic sectors are expected to persist throughout 2007 and early 2008. As a result, U.S. GDP growth is likely to be considerably less vigorous than 2006 in both 2007 and 2008.

Housing investment decelerated throughout 2006 and was 13 per cent lower in the fourth quarter than 12 months earlier. Demand for new housing has fallen considerably since mid-2005, while the number of completed, unsold units has risen. In February 2007, fewer new units were sold than at any time since 1997 and housing starts sank to their lowest level since 1991.

Figure 1.2 Housing starts and Housing Market Index (HMI)

Source: National Association of Home Builders.

The Housing Market Index (HMI) fell sharply in 2006. But more stable HMI trends in late 2006 and early 2007 suggest that the housing market has already started to adjust. The fact that the index is still far below 50 indicates that the residential construction market remains weak.

The number of completed, unsold units is expected to decrease as housing starts taper off. But the housing investment as a percentage of GDP is far above the historical average, and it will take at least a year for the housing surplus to

12

be offset. Thus, housing investment is forecast to decline by almost 14 per cent in 2007 and not start recovering until early 2008.

Figure 1.3 Housing investment as a percentage of GDP

Source: US Department of Commerce.

Recent, widely discussed problems in the sub-prime mortgage market have led to greater uncertainty about the magnitude of the U.S. economic slowdown in 2007. Because more and more people with subprime mortgages are having trouble making payments, many lenders have declared bankruptcy. Falling house prices and rising mortgage rates have probably caused these problems. It is not inconceivable that the impact on house prices will thereby increase and detrimentally affect household consumption even more than anticipated by the base scenario of this forecast.

Changes in the housing market will depress consumption

Given that household consumption accounts for approximately 70 per cent of U.S. GDP, it has a major impact on economic growth. Rising house prices, along with steady income and employment growth, have helped boost household consumption by an annual average of 3.5 per cent in the past three years. But partly due to the impact of the weak housing market, household consumption is expected to grow a good deal slower in 2007 and 2008.

The housing surplus has begun to moderate price increases for existing units, and house prices are even falling in some regions. Because household net worth and the latitude for debt-financed consumption decrease along with house values, household consumption is likely to taper off as well. The decrease in housing construction is also likely to weaken employment, thereby detrimentally affecting consumption in 2007 and 2008. As much as one third of employment growth over the past three years is estimated to have been associated with changes in the real estate market. Lower household saving could offset lower real net worth. But the saving ratio of U.S. households is already negative, and declining net worth points to higher saving instead. Weaker income trends as the result of slower employment and economic growth should also restrain increases in household consumption.

Lower industrial activity

The U.S. industrial sector is in a more fragile position than many other major industrialised nations. Sales have been low in relation to inventories since late 2006, and new orders have tapered off. Industrial output has slowed down as a result. Industrial activity is being squeezed by weak demand in sectors that are dependent on the housing market, competition problems in the auto industry and other developments. Thus, industrial activity is expected to remain less vigorous in 2007. But strong global demand and the cheaper dollar, factors that favour U.S. exporters, are set to counteract weak domestic demand. As a result, exports are expected to grow at a healthy pace in both 2007 and 2008, albeit not as fast as 2006. Meanwhile, import growth is likely to decelerate in the wake of poorer domestic demand. Thus, the contribution of net exports to GDP growth is forecast to be slightly positive in 2007.

As the economic outlook for the industrial sector dims, lower profits and decreasing capacity utilisation are likely to ensue. Thus, the machinery investment in the industrial sector is also expected to grow slower than 2006 in both 2007 and 2008.

13

Figure 1.4 Industrial output and capacity utilisation

Sources: Federal Reserve och Federal Reserve Board.

The weak housing market and industrial activity have already restrained service sub-sectors that depend on orders from them. Taking slower consumption growth into consideration as well, the result is likely to be persistence of the dimmer outlook for the service sector in 2007.

GDP growth below potential growth in both 2007 and 2008

The downturn in the U.S. housing market and the ripple effects it is expected to have on consumption and other factors are likely to considerably depress GDP growth in 2007 to well below the potential growth estimate of approximately 3 per cent. The correction in the housing market is projected to be over sometime in 2008, at which point housing investment should begin to gradually recover. Other economic sectors, including household consumption, would benefit. Monetary policy is also likely to stimulate the U.S. economy in 2008. Owing to the accelerating economic downturn, the Federal Reserve is expected to start lowering the federal funds rate in the latter half of the year. While GDP growth is thereby forecast to be somewhat stronger in 2008 than 2007, it is unlikely to match potential growth until 2009.

As employment growth wanes and demand rises slower, inflationary pressure is expected to ease in 2007. But given somewhat stronger economic growth, inflation should pick up speed in 2008.

1.2 Euro area

Growth finally increasing

Euro area GDP grew in 2006 by 2.6 per cent, the highest in six years. A large percentage of the improvement can be traced to the considerably stronger German economy.

Economic growth is expected to lose some momentum in 2007 and 2008 in the wake of weaker global demand, fiscal austerity and a less expansionary monetary policy. But the slowdown is forecast to be modest, leaving GDP growth at 2.2 per cent in 2007 and 2.1 per cent in 2008.

Germany strongest of the EU big three

Euro area GDP growth accelerated considerably in the fourth quarter of 2006. GDP was 0.9 per cent above the third quarter and 3.3 per cent above the fourth quarter of 2005. The increase was propelled in equal measure by rapid export growth late in the year and ongoing improvement in domestic demand. Foreign trade contributed 0.8 percentage points and domestic demand contributed 0.7 percentage points to GDP growth, while a substantial decrease in inventories made a negative contribution.

The biggest economies of Germany, France and Italy (EU big three) have averaged 1.7 per cent annual GDP growth over the past ten years, as opposed to 3.7 per cent for the other euro countries. France has enjoyed the most rapid growth of the EU big three during most of that time. But Germany has pulled into the lead since early 2005, while Italy is lagging further and further behind.

German investment activity tapered off in mid-2006 and is expected to continue doing so in 2007 as the result of weaker global demand and lower capacity utilisation. Closer trade relations with new EU Member States and Eastern Europe have favoured German exports. In contrast to most other euro countries, Germany’s share of world trade has increased in recent years. Several years of cost-cutting by the business sector have improved competitiveness and substantially lowered unit labour costs.

14

French GDP growth has been driven more by a rapid upturn in consumption, while industrial activity has moderated considerably. Favourable labour market trends are paving the way for a continuation of healthy economic growth in 2007 and 2008. But due to mounting competition problems and more feeble consumption, the deceleration of Italian GDP growth will be more evident during that period.

Common to virtually all euro countries is high business confidence in the manufacturing industry. Expectations for the future dimmed somewhat in autumn 2006 but remain optimistic. New orders are still brisk, while manpower requirements have decreased somewhat. All in all, the confidence indicators point to a modest slowdown in industrial output in 2007.

Consumption recovering

Greater household consumption is vital to the persistence of strong GDP growth in 2007 and 2008. Consumption has been one of the main drivers of economic expansion in countries such as Spain and France that experience favourable employment growth and rising housing prices. However, consumption has contributed only modestly to euro area GDP growth as a whole. But largely due to an increase in Germany as well, euro area consumption grew more rapidly in 2006 than at any time since 2001. The weaker global economy notwithstanding, a number of indications suggest that consumption growth in the euro area will persist in 2007 and 2008. The number of employed workers has increased significantly, and consumer confidence is at its highest point in five years. As public finances strengthen, precautionary saving by households is expected to decrease and provide additional latitude for consumption.

As a result of the VAT hike from 16 per cent to 19 per cent that took effect in January 2007, German consumption growth is forecast to slow down temporarily this year. The acceleration of consumption expected in 2006 barely manifested. Although retail sales (particularly new cars) were up substantially during the fourth quarter, the overall impact was small. Given a considerable improvement in the labour market and rising consumer confidence, the 2007 slowdown stemming from the VAT hike is expected to be short-lived and relatively modest in terms of both consumer prices and consumption.

Inflation more modest in 2007

Falling energy prices moderated inflation considerably in autumn 2006. But inflation speeded up again in early 2007. Measured as the Harmonised Consumer Price Index (HICP), inflation was up from 1.6 per cent in October 2006 to 1.8 per cent in February 2007.

Core inflation (HICP excluding energy and unprocessed food) has risen sharply since the end of 2006. As a result, the difference between aggregate HICP inflation and core inflation has evaporated. Core inflation was 1.9 per cent in February 2007.

Figure 1.5 Inflation in the euro area

Sources: Eurostat.

Much of the rate of growth in core inflation is due to the German VAT hike, as the result of which inflation (excluding energy prices) in Germany rose from 1.2 per cent in December 2006 to 1.8 per cent in February 2007.

Inflation of 2.2 per cent in 2006 was above the ECB inflation target for the seventh consecutive year. Because the impact of earlier oil price hikes will drop out of the 12-month comparisons this summer, the energy component of the consumer price index will hold down inflation until midyear. The combination of lower energy prices and tighter monetary policy is expected to push inflation down to 2.0 per cent in 2007 and 2008.

When will wage growth take off?

The 7.4 per cent unemployment rate at the beginning of 2007 was lower than the high-growth years around 2000. The decrease in the number of jobless workers is forecast to taper off, leaving

15

the unemployment rate at approximately 7.4 per cent in both 2007 and 2008.

A key difference between now and the period around 2000 is that a considerably improved labour market has not accelerated wage growth. One possible reason is that the labour market reforms adopted in recent years have held down equilibrium unemployment. A less auspicious explanation may be that there is a greater time lag between a tighter labour market and its impact on wages than was previously the case. If that is true, wage growth is likely to accelerate considerably in 2007 once the euro area business cycle enters a more mature phase. But global competition and the ECB’s interest rate policy are likely to restrain wage increases.

Figure 1.6 Unemployment and unit labour costs

Sources: Eurostat.

1.3 Asia

Increasingly integral to the global economy

Many years of very rapid growth, particularly in China and India, have gradually increased Asia’s share of world GDP. Measured as purchasing power parity (PPP)(1), Asia’s share rose to approximately 36 per cent in 2006, as opposed to 20 per cent for the United States and 15 per cent for the euro area. As GDP rises in Asia, global growth increasingly reflects developments in the region.

Whereas both the U.S. and euro area economies are set to slow down in 2007, Asia still faces bright prospects of continued rapid growth over the next few years. Domestic demand is an increasingly vital driver for the entire region. Intra-Asian trade has risen, while reliance on exports to the United States has decreased. Furthermore, low inflationary pressure has opened the door to a more expansionary monetary policy if necessary. Due to strengthening public finances, fiscal policy is also becoming an increasingly viable instrument of control. The exception is India, whose tight fiscal policy will remain hostage to large government budget deficits.

Asian GDP increases are expected to moderate over the next two years in the wake of somewhat slower growth in China and India, as well as the newly industrialised economies of South Korea, Taiwan, Hong Kong and Singapore that will be affected by less vigorous global export demand.

Chinese growth will taper off but remain very high

Exports have been fuelling growth in China. According to the IMF, China’s share of world exports rose from 1 per cent in the early 1980s to more than 8 per cent in 2006. The advances of the export industry have generated both higher corporate profits and rising employment in the urban regions. Gross capital formation, and to a lesser extent consumption, has grown very fast as a result. Rapid credit expansion has also spurred gross capital formation, thereby increasing the risk of overinvestment and bad loans. The persistence of strong gross capital formation and export growth in 2006 contributed to a 10.7 per cent increase in GDP.

(1) Measuring GDP as PPP takes differences among the purchasing power of the various countries into consideration.

16

Figure 1.7 Chinese GDP growth by quarter

Source: National Bureau of Statistics.

China adopted austerity measures in late 2006 aimed at restraining rapid gross capital formation and credit growth. Consisting of a lending rate hike, stronger administrative controls and higher reserve requirements, the effort made an impact and checked growth of gross capital formation somewhat at the end of the year. The moderating effect on growth of gross capital formation is expected to continue in 2007 and 2008, thereby contributing to more deliberate (but still very rapid) GDP increases. Weaker export trends as a result of more sluggish global demand growth are also set to rein in Chinese economic expansion. The country’s currency strategy of a gradual appreciation of the yuan against the dollar in order to achieve greater exchange-rate flexibility is also expected to detrimentally affect exports at the margin.

Expectations that GDP will grow somewhat slower are in line with China’s current five-year economic plan, which targets a long-term, economically sustainable average of 7.5 per cent a year. The idea is also for consumption and innovation to drive growth more than before. But consumption growth is unlikely to speed up within the next four years. Given the flimsy social safety net, the saving ratio among Chinese households is forecast to remain high.

Indian economic growth will slow down

Domestic demand and household consumption have historically made the biggest contributions to Indian economic growth. Partly due to rising demand by China, which accounts for approximately half of Indian export trade in Asia, exports have become an increasingly important engine of economic growth in recent years. India’s share of world GDP has risen to more than 6 per cent. Measured as PPP, only the United States, China and Japan contribute more to world GDP.

Indian GDP grew by 9.3 per cent in 2006. Owing to a rising level of resource utilisation, thereby restraining output in both the industrial and service sectors, economic growth is projected to taper off in 2007 and 2008. Moreover, Indian monetary policy is likely to tighten in the wake of rising inflation and rapid credit expansion. Given large government budget deficits, fiscal policy is expected to be restrictive.

Japan back in the game

While Japan has played a more modest role during the arduous years of deflation, its importance should not be underestimated. GDP growth of 2.2 per cent in 2006 reinforced the view that Japan is once more a force to be reckoned with. The Japanese economy is expected to expand somewhat slower in 2007-2008 than 2006 but remain above OECD’s estimated potential growth of 1.4 per cent. One factor contributing to more modest GDP increases is likely to be weaker growth of gross capital formation in the next two years. The significant decline in machinery orders early in 2007 will probably restrain the Japanese industrial sector’s propensity to make capital expenditures. The incipient adjustment of output capacity to demand is also holding down the machinery component of gross capital formation. Furthermore, the Bank of Japan has dropped its zero interest policy and raised its key interest rate by 50 basis points. The probable result will be additional restraint on gross capital formation at the margin.

Although employment has risen and unemployment declined, household consumption is forecast to grow only modestly in 2007 and 2008. Inflation, which is struggling to stay above zero, is restraining the propensity to consume. Japan had zero inflation in February 2007, and prices are expected to rise only marginally for the rest of the year.

17

Figure 1.8 Inflation in Japan

Source: Ministry of Internal Affairs and Communications.

Owing partly to the large percentage of part-time employees and number of workers retiring, real wage growth has also been sluggish. Wage demands and levels are lower among young workers than those who are retiring. As the labour market tightens, real wage growth is expected to accelerate but not enough for consumption to take off in earnest. Exports, the main reason that the Japanese economy has steadily strengthened since 2000, are forecast to exhibit somewhat slower growth going forward as the result of weaker import demand by its most important trading partners of China and the United States. But due partly to weaker import growth, net exports are set to continue making a positive contribution to Japanese economic expansion.

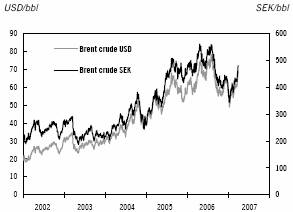

1.4 Oil prices

Oil prices hit record highs in summer 2006. Brent crude peaked at close to USD 80 per barrel in early August. Due partially to unusually warm weather in the United States, oil prices retreated late in the year. Cold weather and reduced oil inventories contributed to renewed hikes in early 2007.

For a number of reasons, oil prices have risen substantially since 2002. Output capacity has expanded relatively slowly since 2000, while demand for oil has risen rapidly in recent years.

The strong global economy has contributed to greater demand for oil. The emergence of China and India as significant net consumers of oil has helped narrow the gap between potential supply and actual demand (reserve capacity). As a result, oil prices have become increasingly vulnerable to supply disruptions and geopolitical uncertainty in oil-producing regions.

Figure 1.9 Price of Brent crude

Source: Reuters.

Global reserve capacity is expected to be limited in the short term, while demand remains strong. Thus, relatively high oil prices are expected to persist.

There is much to suggest that global reserve capacity will increase over the longer term. The price hikes of recent years have boosted investment in both new and existing oil fields. In the wake of a less vigorous global economy, demand is likely to taper off toward the end of the forecast period. As a result, the supply of crude is projected to rise faster than demand in the long term and thereby increase reserve capacity. Refinery capacity is also expected to expand, especially after 2009 as the OPEC countries and Asia put new capacity to use.

Expanding reserve capacity is likely to reduce the risk premium and thereby oil prices as well. But the price decline should be limited by the risk of geopolitical unrest and future production disruptions, as well as higher costs of oil production. Oil is projected to cost USD 60 per barrel at the end of 2007, USD 60 at the end of 2008, USD 55 at the end of 2009 and USD 50 at the end of 2010.

Predicting future oil prices is still associated with a great deal of uncertainty. Politically unstable countries account for an increasing percentage of production. Changes in global growth, unexpected production disruptions, and geopolitical tensions retain the potential to significantly affect oil prices.

18

2 Financial markets

The financial markets have been haunted recently by uncertainty about the U.S. economy. Signs of a slowdown in the United States and uneasiness about the U.S. mortgage market have contributed to a decline in international bond yields. In the light of weaker economic growth, the Federal Reserve is expected to cut the federal funds rate in the latter half of 2007. Meanwhile, the ECB and Riksbank are likely to further tighten monetary policy. The Bank of Japan is also forecast to continue raising its key interest rate, albeit slowly.

Expectations of future interest rate differentials among various countries have set the tone for the foreign exchange market. The prospect of narrower differentials contributed to a depreciation of the dollar against both the euro and krona in 2006. As the differentials between Sweden and the other regions narrow, the krona is expected to appreciate further.

Higher interest rates and a stronger krona involve tighter monetary conditions in Sweden. But the change is from an expansionary level, and interest rates are set to remain low. All in all, Swedish monetary conditions are anticipated to remain relatively expansionary.

2.1 Outside Sweden

Lower bond yields due to less risk appetite

Owing largely to greater uncertainty about the U.S. economy, international bond yields fell after summer 2006. Strong economic indicators in late 2006 and early 2007 raised expectations for U.S. growth, thereby contributing to rising international bond yields. Most recently, uncertainty about the U.S. economy and uneasiness about U.S. mortgage lending institutions have dogged the financial markets. The greater risk aversion stemming from that uncertainty has caused capital flight from investment options with lower creditworthiness to government bonds, thereby helping to push down bond yields. Generally speaking, both Swedish and international bond yields are at historically low levels.

Figure 2.1 Ten-year bond yields in Germany, the United States, Japan and Sweden

Source: Reuters.

Flatter yield curve

As short-term bond yields have continued to climb while long-term yields have declined since the beginning of 2007, the yield curve(2) has flattened. The yield on the 10-year U.S. Treasury note is lower than on short-term bills. In the past, such conditions have often signalled an impending economic downturn.

(2) The yield curve describes the relationship between the yields on treasury bills and bonds of various maturities.

Given the various structural explanations for the low bond yields, whether that historical relationship still holds true today is a matter of speculation. One explanation stems from new rules for pension funds, leading to greater demand for long-term bonds. Increased confidence in the inflation targets of central banks has probably contributed to a decrease in the term premium – in other words, investors are demanding less compensation for holding long-term bonds because they believe that inflation is now less volatile. An increase in world net saving, particularly in the newly industrialised Asian economies and other emerging economies, has presumably helped depress bond yields as well.

Recent short-term interest rate hikes by the ECB and Bank of Japan also explain the flat shape of the yield curve.

European and Japanese bond yields are expected to increase in the wake of strong economic growth, greater resource utilisation, rising inflation and higher short-term interest rates. Because the U.S. curve is likely to acquire a positive slope, yields are predicted to increase

19

marginally in the United States as well. Several factors point to generally higher international interest rates in the longer term. Globalisation has contributed to an expansion of global labour supply. The higher gross capital formation required by such an expansion should add impetus to rising interest rates. Moreover, the high level of household saving in Asian countries is set to subside as incomes rise and social safety nets improve.

This forecast anticipates a yield of 4.80 per cent on the 10-year U.S. Treasury note and 4.30 per cent on its German counterpart at the end of both 2007 and 2008.

ECB will continue tightening while the Federal Reserve cuts federal funds rate

The Federal Reserve has left the federal funds rate at 5.25 per cent since summer 2006. Due to the strength of U.S. economic indicators at the end of 2006, prices of forward contracts indicated that the Federal Reserve would tighten monetary policy. But the slowdown in U.S. GDP growth during the first quarter of 2007 changed prices of forward contracts, which now point to a cut in the federal funds rate to 4.75 per cent by the end of 2007. This forecast anticipates that the signs of weaker economic growth will be pivotal to the Federal Reserve’s decisions. The prediction is that the federal funds rate will be cut this year and decrease from the 4.75 per cent figure in December 2007 to 4.5 per cent in December 2008.

The ECB has continued to tighten monetary policy, raising its key interest rate by 2 percentage points to 3.75 per cent since December 2005. The ECB’s moves have been motivated by the fact that inflation and money supply growth, the two pillars of its monetary policy strategy, have been above the target level. Rapid, persistent price increases can increase the inflation expectations of households and undermine their confidence in the target, thereby spurring wage growth. Due partly to strong growth in lending to households, money supply is continuing to expand rapidly. Meanwhile, the recent strengthening of the European economy points to additional hikes in the ECB’s key interest rate. The ECB has been signalling that it plans to gradually raise the rate toward a more neutral level – this forecast anticipates 4.0 per cent at the end of both 2007 and 2008.

Responding to the recent palpable strength of the real Japanese economy, the Bank of Japan has raised its key interest rate by 50 basis points since summer 2006. Core inflation has also risen, though remaining low. This forecast anticipates that the Bank of Japan will continue raising its key interest rate, albeit slowly.

Figure 2.2 Key interest rates in the euro area, Sweden and the United States

Sources: ECB, Riksbank and Federal reserve.

Dollar will weaken further

Strong U.S. economic indicators in late autumn 2006 temporarily shored up the dollar. Weaker indicators recently have raised expectations that the Federal Reserve will cut the federal funds rate during the course of 2007. The prospect of lower positive interest rate differentials vis-à-vis other currency areas has sapped the dollar’s strength once again.

Figure 2.3 U.S. dollar against the yen and euro

Source: Reuters.

The dollar is likely to depreciate further as growth and interest rate differentials narrow. This forecast anticipates that the dollar will fall

20

to 1.35 against the euro and 115 against the yen at the end of 2007, followed by 1.35 against the euro and 110 against the yen at the end of 2008.

Carry trades

Carry trades have had a major impact on the foreign exchange market in recent years. A carry trade involves borrowing in a low-interest currency to invest in higher yielding assets. A similar transaction is available in the currency futures market. The principle is the same – to take advantage of the interest rate differential between two countries. The theory posits that systematic generation of profits on interest rate arbitrage is impossible, but that the differentials should manifest in the simultaneous appreciation of low-interest currencies and depreciation of high-interest currencies. Nevertheless, such arbitrage trading has periodically generated profits and affected the foreign exchange market. The yen has gradually depreciated against the dollar and euro over the past two years. Traders have been borrowing in yen at low interest rates to invest in higher yielding dollar and euro assets. Low Japanese interest rates have further depressed the yen. A carry trade can be undermined by altered monetary conditions. Recent economic indicators suggest that Japanese growth has accelerated, and the Bank of Japan raised its key interest rate in February 2007. Changes in monetary policy can quickly affect currency flows and exchange rate levels. Nevertheless, the Bank of Japan is expected to raise its key interest rate at a deliberate pace.

Equity markets are more volatile

The major world stock indices have been more volatile recently. Uncertainty about U.S. economic growth and uneasiness about U.S. mortgage lending institutions have contributed to substantial movements on world equity markets. Whether a temporary correction or a more sustained bear market is under way after almost four years of a bull market remains to be seen.

Swedish firms reported generally higher profits for the fourth quarter of 2006 than analysts had predicted. However, the consensus estimate is that profits will decline somewhat going forward. Both the U.S. and European equity markets are undervalued in comparison with the bond market. But rising interest and labour costs may squeeze the margins of firms in the longer term.

Figure 2.4 Equity market performance in the euro area, the United States, Japan and Sweden

Source: Reuters.

2.2 Sweden

After the yield on 10-year Swedish government bonds rose in late 2006, long-term yields have retreated in line with international trends. But given the favourable economic conditions, bond yields are still low.

Figure 2.5 Spread between ten-year bond yields in Sweden and Germany

Source: Reuters.

Since May 2005, 10-year Swedish government bonds have been in the historically unusual position of yielding less than their German equivalent. The fact that the Riksbank’s repo rate has been lower than the ECB’s key interest rate during that period provides most of the explanation. In addition, new rules for pension funds

21

have stimulated demand for long-term Swedish bonds. Meanwhile Sweden’s shrinking, relatively small central government debt is limiting the supply of long-term government bonds.

This forecast anticipates that Swedish bond yields will rise in both 2007 and 2008 as available economic resources dwindle and monetary policy becomes less expansionary. Swedish bond yields are expected to increase somewhat more than their German equivalents in 2008 as the spread between the Riksbank’s repo rate and the ECB’s key interest rate narrows. The yield on 10-year Swedish government bonds is projected at 4.05 per cent in December 2007, 4.65 per cent in December 2008 and 4.85 per cent in December 2009.

Riksbank continuing to raise the repo rate

The Riksbank is continuing to tighten monetary policy. Its repo rate hikes from 1.5 per cent to 3.25 per cent since 2006 are likely to be followed by more. Despite strong economic growth, Swedish inflation is low. Thus, the spread between the repo rate and inflation has widened. Inflation remains below the Riksbank’s target. But underlying inflation, as measured by the Riksbank’s UND1X index, is expected to rise during the latter half of the year to 0.8 per cent at the end of 2007, 1.9 per cent at the end of 2008 and 2.4 per cent at the end of 2009 (see Section 4.3 on inflation).

Figure 2.6 Repo rate and uncertainty range

Sources: Riksbank and Ministry of Finance.

The Ministry of Finance issues its repo rate forecast with an uncertainty range based on its past forecast errors.(3) The present forecast anticipates gradual hikes in the repo rate over the next few years. Ongoing employment growth is expected to contribute to more rapid wage increases and higher resource utilisation. The forecast anticipates a repo rate of 3.5 per cent at the end of 2007, 4.5 per cent at the end of 2008, 4.75 per cent at the end of 2009 and 4.25 per cent at the end of 2010.

(3) The deviations are based on forecasts in the 1998-2006 Spring Fiscal Policy Bills.

Krona will appreciate

Due primarily to the prospect that the Riksbank would tighten monetary policy, the krona appreciated against both the euro and dollar in autumn 2006. But owing chiefly to changed expectations about interest rate differentials between Sweden and the other regions, the krona has depreciated against both currencies since the beginning of 2007.

Favourable underlying factors such as a current account surplus, stable public finances, solid economic growth and modest inflation are set to strengthen the krona. The trade-weighted (TCW) exchange-rate index is projected to be 124 at the end of 2007, 120 at the end of 2008, 121 at the end of 2009 and 121 at the end of 2010.

Figure 2.7 TCW exchange-rate index

Source: Reulers.

22

Volatility on the Stockholm Stock Exchange

Owing primarily to rising corporate profits, the Swedish bull market charged ahead in autumn 2006. The stock market started off 2007 on a strong note. But uncertainty about the U.S. economy and mortgage market led to falling share prices around the world. At the moment, the equity markets appear to have stabilised.

At approximately 24 per cent, growth in corporate profits was somewhat higher than expected in the fourth quarter of 2006. The primary industries of forestry, steel and minerals reported the biggest increases, followed by the engineering and pharmaceutical industries. Analysts generally predict that earnings growth will continue but decelerate. The consensus estimate(4) is that the earnings of firms listed on the Stockholm Stock Exchange will rise by approximately 6 per cent in 2007, 9 per cent in 2008 and 5 per cent in 2009. By and large, slower earnings growth points to an impending period characterised by weaker growth of gross capital formation (see Section 3.2 on gross capital formation).

(4) Source: FactSet Consensus Estimates (JCF)

Outlook for the Swedish economy

Financial market factors such as interest and exchange rates affect the Swedish economy by influencing business strategies and consumer behaviour. Prices of capital assets such as equities and housing affect household net worth and ultimately consumption. Fiscal conditions are expected to stay relatively expansionary throughout the rest of 2007 but tighten as the Riksbank raises the repo rate throughout 2008. Short-term real interest rates have risen in the wake of the higher repo rate, while inflation has remained low. Household borrowing is still increasing rapidly, albeit more modestly. The borrowing trend, which is partly due to the continuation of expansionary monetary policy, is contributing to strong demand growth in the total economy. The relatively weak krona is expected to appreciate in late 2007 and 2008.

Table 2.1 Interest and exchange rate assumptions

Value at the end of each year

| | 2006 | | 2007 | | 2008 | | 2009 | | 2010 | |

Repo rate | | 3.00 | | 3.50 | | 4.50 | | 4.75 | | 4.25 | |

6-month interest rate | | 3.07 | | 3.60 | | 4.55 | | 4.70 | | 4.30 | |

5-year interest rate | | 3.70 | | 3.95 | | 4.60 | | 4.80 | | 4.50 | |

10-year interest rate | | 3.65 | | 4.05 | | 4.65 | | 4.85 | | 4.55 | |

Spread Swe-Ger 10 year | | -0.15 | | -0.25 | | 0.35 | | 0.55 | | 0.25 | |

6-month EURIBOR | | 3.61 | | 4.05 | | 4.05 | | 4.05 | | 4.05 | |

TCW index | | 123 | | 124 | | 120 | | 121 | | 121 | |

EUR/SEK | | 9.04 | | 9.10 | | 8.80 | | 8.90 | | 8.90 | |

USD/SEK | | 6.84 | | 6.74 | | 6.52 | | 6.59 | | 6.59 | |

EUR/USD | | 1.32 | | 1.35 | | 1.35 | | 1.35 | | 1.35 | |

Sources: Reuters and Ministry of Finance.

23

3 Swedish demand and output

Due largely to an increase in demand on a broad front, Swedish GDP growth was very strong at 4.4 per cent in 2006 (see Figure 3.1). Export growth has been rapid, the sustained upswing in gross fixed capital formation has persisted and household consumption has risen steadily.

Figure 3.1 GDP

Sources: Statistics Sweden and Ministry of Finance.

GDP growth will remain rapid in 2007 and 2008

In the wake of more modest growth of exports and gross fixed capital formation, GDP growth is set to be slower in 2007 and 2008 (see Table 3.1) but remain high. Given a cooling off of the global economy and a stronger krona, export growth is likely to be somewhat slower, though healthy from a historical perspective. The persistence of robust demand, high capacity utilisation and the financial strength of firms should help keep gross fixed capital formation in sectors such as industry and residential construction at a high level. But as demand tapers off somewhat and the output capacity that has been added in recent years is put to use, growth in gross fixed capital formation is likely to decelerate in 2007 and 2008.

Steady expansion of Swedish household consumption is expected to partially offset slower growth of exports and gross capital formation. Disposable income is rising quickly, employment is proceeding upward and household net worth is starting from a solid position. The cumulative impact should be high consumption growth in 2007 and 2008, particularly in 2007 as income tax cuts help boost household disposable income. Spurred by sound finances, local government is set to exhibit the most rapid consumption growth in the general government sector.

Table 3.1 Demand and output

| | SEK Billion | | Percentage change in volume | |

| | 2006 | | 2006 | | 2007 | | 2008 | | 2009 | | 2010 | |

Household consumption | | 1 339 | | 2.8 | | 4.2 | | 3.8 | | 2.4 | | 2.6 | |

General government consumption | | 759 | | 1.8 | | 1.4 | | 1.4 | | 0.5 | | 0.6 | |

Central govt. | | 207 | | 1.0 | | 0.5 | | 0.4 | | 0.1 | | 0.1 | |

Local govt. | | 552 | | 2.0 | | 1.8 | | 1.7 | | 0.7 | | 0.7 | |

Investment | | 509 | | 8.2 | | 5.6 | | 3.4 | | 2.3 | | 2.7 | |

Change in stocks(1) | | 0 | | 0.0 | | 0.0 | | 0.1 | | 0.0 | | 0.2 | |

Exports | | 1 456 | | 9.1 | | 7.0 | | 6.3 | | 6.3 | | 6.0 | |

Imports | | 1 224 | | 7.8 | | 7.6 | | 6.7 | | 6.7 | | 6.7 | |

GDP | | 2 838 | | 4.4 | | 3.7 | | 3.3 | | 2.1 | | 2.3 | |

GDP, calendar adjusted | | — | | 4.7 | | 3.9 | | 3.2 | | 2.1 | | 2.0 | |

(1) Contribution to GDP-growth, percentage points.

Sources: Statistics Sweden and Ministry of Finance.

More moderate GDP growth in 2009 and 2010

GDP growth forecasts for the years after 2008 are based on estimates of the size of potential supply, measured as potential GDP. As described by an explanatory box in Chapter 4, potential GDP is calculated on the basis of potential productivity and potential labour supply.

Due to a rapid expansion of GDP and employment in 2007-2008, the level of resource utilisation is forecast to be high. In other words, the output gap is expected to be positive. Given a positive output gap in 2008, wage and price increases are likely to accelerate while the Riks-bank raises the repo rate, thereby contributing to a stronger krona and weaker domestic demand. Both household and general government consumption, as well as gross fixed capital formation, are set to rise slower in 2009 and 2010 than 2008. Partly due to the appreciation of the krona, export growth should moderate somewhat.

Demand is likely to taper off somewhat in 2009 and 2010 while GDP increases approximately 1 percentage point slower than potential GDP.

24

Risk outlook

The primary risk to the Swedish GDP forecast would be an unexpectedly abrupt downturn in the U.S. economy that restrains global (and thereby Swedish) growth. But as discussed in Section 1.1, the base scenario is a soft landing in the United States.

Certain risks are primarily associated with developments in the medium term. The magnitude and timing of the impact of the government’s economic policies are difficult to project. Assessing current resource utilisation and future growth in potential GDP is also fraught with uncertainty. Such factors are integral to the direction of the economy over the next few years. To illustrate the uncertainty of the assessments, Chapter 6 presents two alternative scenarios in which the Swedish economy takes a different course than in the base scenario.

3.1 Exports

Swedish exports grew rapidly in 2006 and are expected to continue upward. The upswing in 2006 extended to most groups of products and virtually every region, with the exception of the United States. Increases to European countries were particularly rapid, and the strong German economy helped make it Sweden’s biggest export partner once again.

Given that the European economy has stabilised at a high level and global demand is still brisk, the prospects for Swedish export growth remain auspicious. Exports are likely to rise steadily throughout the forecast period but at a gradually slower pace as the krona appreciates and the global economy cools off. Export growth is expected to total 7.0 per cent in 2007 and 6.3 per cent in 2008, followed by a further modest deceleration in 2009-2010.

Outlook for Swedish exports remains bright

The prospects for ongoing robust export growth are good. Both the global economy and demand for Swedish exports in the world market remain strong. Exports are rising steadily to all major regions, particularly Europe by virtue of its vigorous economy, except the United States. The European economy is more stable now that it is transitioning from having been driven mainly by external demand to increasingly being driven by domestic demand. A total of 70 per cent of Swedish exports goes to European countries.

Figure 3.2 World market growth and growth in Swedish exports

Sources: Statistics Sweden and Ministry of Finance.

Given high sales and earnings in 2006, Swedish firms find themselves in a strong financial position. The high sustained level of industrial activity is particularly benefiting the industrial sector, and the engineering sector is especially optimistic.

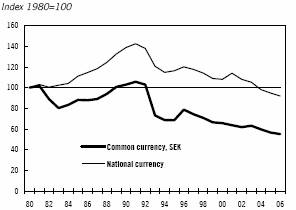

The competitiveness of the industrial sector is strong. In both national and common currency, the sector’s unit labour cost has trended downward compared to other countries since the early 1990s (see Figure 3.3 below). The reason is that Sweden has enjoyed higher productivity growth and the krona has depreciated for a long time.

The NIER Investment and Intermediate Goods Survey points to persistence of strong export growth. The Purchasing Managers Index also suggests that industrial activity will remain brisk.

Exports of finished goods such as motor vehicles, telecom products and pharmaceuticals grew very rapidly, particularly in late 2006. The trend is expected to generally proceed in 2007, if somewhat more leisurely than in 2006.

Firms in the basic industries are also enjoying solid export growth, and survey statistics suggest that they will continue to do so. But exports of primary products are expected to slow down more than exports of finished goods in 2007. For instance, exports of petroleum products are

25

set to taper off significantly in 2007 in the wake of supply restrictions following very rapid growth in 2006

Exports of goods are likely to grow steadily throughout the forecast period, though gradually decelerating due to a cooling down of the global economy and an appreciation of the krona. Exports of goods are forecast to rise by 6.9 per cent in 2007 and 6.1 per cent in 2008.

Figure 3.3 Unit labour cost in Swedish industry compared to 14 OECD countries

Sources: Statistics Sweden, NIER and Ministry of Finance.

Exports of services growing at a healthy clip

While exports of services grow in line with exports of goods, the trend for the past ten years has been a somewhat faster services growth. As a result, services accounted for 26 per cent of total exports in 2006 – up 6 percentage points since 1996.

Exports of services rose by 12 per cent in 2006, and the healthy increases are expected to continue in 2007. Brisk world trade has led to a rapid upturn in exports of transport services and to greater exports of business services. Export of travel and tourism (expenditures of foreign visitors in Sweden) has also benefited from the robust global economy, which is increasingly dependent on household consumption growth. Like exports of goods, exports of services are expected to grow more modestly in the next few years as the global economy cools off and the krona appreciates.

Net trade in services has been positive in recent years, and exports of services are projected to increase faster than imports of services during the forecast period. However, due to the appreciation of the krona, import of travel and tourism (foreign travel by Swedes and associated expenditures abroad) is likely to rise a little faster than export of travel and tourism in 2008.

Exports of services are expected to grow by 7.4 per cent in 2007 and 6.9 per cent in 2008.

Table 3.2 Exports of goods and services and change in export prices

| | SEK billion | | Percentage change in volume | |

| | 2006 | | 2006 | | 2007 | | 2008 | | 2009 | | 2010 | |

Exports of goods | | 1 051 | | 8.0 | | 6.9 | | 6.1 | | — | | — | |

Processed goods | | 878 | | 8.3 | | 7.5 | | 6.7 | | — | | — | |

Exports of services | | 367 | | 12.0 | | 7.4 | | 6.9 | | — | | — | |

Total exports | | 1 418 | | 9.1 | | 7.0 | | 6.3 | | 6.3 | | 6.0 | |

Export prices | | — | | 2.7 | | -0.7 | | -0.3 | | 1.0 | | 1.2 | |

Sources: Statistics Sweden and Ministry of Finance.

Export prices to fall again

Due primarily to rising petrol and metal prices, along with the weaker krona, export prices have increased over the past two years. As primary product prices fall back and the krona appreciates, export prices are expected to retreat in 2007-2008.

After rising substantially in late 2006, metal prices are expected to decline during 2007. However, demand for metals remains robust, and the decline is not likely to be as steep as the increases in 2005-2006.

The expected appreciation of the krona during the forecast period should exert pressure on firms to hold down the prices of their products so as not to compromise competitiveness. But once again, the price cuts should be limited by the heavy demand that many firms are still encountering. Although primary product costs have risen considerably for a number of years and production costs are thereby higher, some firms are still able to pass part of the increase on to their customers by raising prices. For instance, big steel companies have announced hikes this spring. Export prices are expected to fall by 0.7 per cent in 2007 and 0.3 per cent in 2008. Partly due to the diminished impact of the stronger krona, export prices will probably recover somewhat in the medium term, rising by 1.0 per cent in 2009 and 1.2 per cent in 2010.

26

3.2 Investment

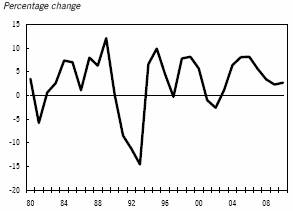

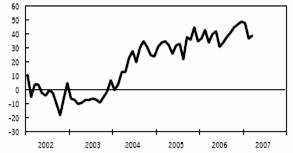

Robust growth of investment for the past three years

Investment has risen at an accelerating pace since 2003 (see Figure 3.4), and the brisk investment activity has spilled over to more and more of the total economy. Growth of investment averaged 7.6 per cent in 2004–2006, including 8.2 per cent in 2006. Not since the late 1980s has investment grown so rapidly for three consecutive years.

Figure 3.4 Investment

Sources: Statistics Sweden and Ministry of Finance.

Investment will grow steadily

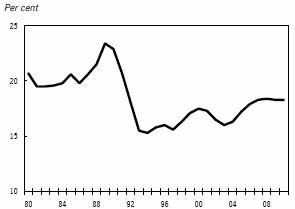

Persistently high capacity utilisation and the financial strength of firms are set to spur growth of investment going forward. The government’s economic policies, which are expected to boost employment and thereby capital expenditure requirements by firms, should promote continuation of solid growth of investment. But a growing number of firms are likely to have expanded their output capacity over the next year while global demand tapers off. As a result, growth of investment is predicted to gradually decelerate in 2007 and 2008. Total investment is projected to increase by 5.6 per cent in 2007, 3.4 per cent in 2008 (see Table 3.3), 2.3 per cent in 2009 and 2.7 per cent in 2010. Investment is expected to account for 18.3 per cent of GDP, the highest percentage since 1991, at the end of 2010 (see Figure 3.5).

Figure 3.5 Investment as a percentage of GDP

Sources: Statistics Sweden and Ministry of Finance.

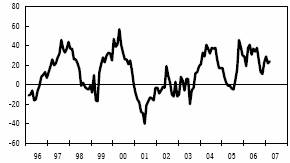

Investment by goods producers growing rapidly again

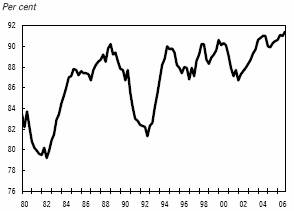

The upswing in exports that began in 2003 has claimed a growing share of industrial sector output capacity (see Figure 3.6), generating a need for greater investment – particularly on machinery. Investment in machinery in the industrial sector advanced vigorously during 2005, above all in the paper products industry. Once the paper products industry started up the machinery in autumn 2005, investment decreased sharply and moderated the increases for the industrial sector as a whole in 2006. Nevertheless, machinery investment continued to grow steadily in other sub-sectors during 2006 and brought the total figure for the industrial sector to 2.3 per cent.

Figure 3.6 Capacity utilisation in the industrial sector

Source: Statistics Sweden.

Despite the vigorous investment activity of recent years, persistently strong foreign demand and rising domestic demand has propelled capacity utilisation to a record high since measurements

27

began in 1980. New orders to the industrial sector remain high, both foreign and domestic demand are strong, interest rates are relatively low and corporate profits are growing briskly. Thus, the prospects are bright for continuation of rapid growth in investment.

The Statistics Sweden Business Investments survey points to a sharp upswing in 2007. The majority of sectors, most notably the chemical and mining industries, are planning for increased investment. Investment in the paper products industry is also expected to increase somewhat, while the construction component of investment in the industrial sector should taper off.

The global economy is set to slow down in 2007–2008, and Swedish exports are likely to cool off. Thus, demand for Swedish-made goods will probably decline somewhat, as reflected in progressively lower expectations by the manufacturing industry for orders from the export market. The need for investment on machinery should also ebb in the longer term.

Investment in the industrial sector is expected to grow briskly in 2007 but slow down somewhat in 2008.

Particularly in view of major efforts by electricity suppliers to boost generation and improve supply, rapidly increasing investment in the energy sector over the past few years is likely to continue.

Table 3.3 Investment

Percentage change

| | 2006 | | 2007 | | 2008 | | 2009 | | 2010 | |

Business sector | | 6.1 | | 4.8 | | 4.6 | | — | | — | |

Producers of goods | | 6.1 | | 8.1 | | 5.9 | | — | | — | |

Producers of services | | 6.1 | | 2.1 | | 3.4 | | — | | — | |

Housing | | 16.5 | | 10.1 | | -1.5 | | — | | — | |

General government | | 8.7 | | 4.1 | | 4.4 | | — | | — | |

Central government | | 8.2 | | 7.2 | | 5.7 | | — | | — | |

Local government | | 9.2 | | 0.9 | | 3.0 | | — | | — | |

Total | | 8.2 | | 5.6 | | 3.4 | | 2.3 | | 2.7 | |

Sources: Statistics Sweden and Ministry of Finance.

According to the NIER Business Tendency Survey, expectations in the construction industry have dimmed somewhat of late. While firms believe that new orders and construction will grow further, fewer and fewer anticipate an improvement in the construction market over the next 12 months. But investment in housing is expected to increase substantially in 2007, while construction in the property management sub-sector and the general government sector has taken off. Given solid new orders and a broader-based upswing in construction activity, investment by the construction industry is thereby expected to rise steadily in 2007 and 2008.

Investment by goods producers is predicted to climb by 8.1 per cent in 2007 and 5.9 per cent in 2008 (see Table 3.3).

Investment by service producers will slow down

Investment in the service sector – particular financial services and property management, as well as post and telecommunications – rose steadily in 2006.

Investment in wholesale and retail trade also grew at a healthy pace in 2006, and robust consumption growth is likely to give it an additional boost in 2007–2008. For instance, new department stores are opening in several market segments, including building supplies and home furnishings. Investment in household services is also forecast to grow at a good clip in 2007 and 2008.

After declining for three years, investment in the property management sub-sector (excluding housing) rose in 2005 and took off even more in 2006. Rapidly expanding household consumption is fuelling most of the investment, including new construction and expansion of shopping centres, in this sector as well. As a result, investment in the property management sub-sector is expected to grow steadily in 2007 and 2008.