GOVERNMENT OF JAMAICA

This description of the Government of Jamaica is dated as of March 9, 2012 and appears as Exhibit (d) to the Government of Jamaica’s Annual Report on Form 18-K, as amended, to the US Securities and Exchange Commission for the fiscal year ended March 31, 2011.

D-1

EXCHANGE RATES

The following table shows exchange rate information for the selling of US dollars for the periods indicated. The Federal Reserve Bank of New York does not report a noon buying rate for the JA dollar. The official exchange rate published by the Bank of Jamaica for US dollars on March 7, 2012 was J$87.22 per US$1.00.

Foreign Exchange Rates

| | | | | | | | | | | | | | |

Year | | Month | | Average for

Period(1) | | | End of Period | | | Percentage Change(2)

(End of Period) | |

| | | (spot weighted average ask in J$ for US$) | |

| | | | |

2005 | | | | | 62.60 | | | | 64.58 | | | | 4.79 | |

2006 | | | | | 65.98 | | | | 67.15 | | | | 3.98 | |

2007 | | | | | 69.16 | | | | 70.62 | | | | 5.17 | |

2008 | | | | | 73.36 | | | | 80.47 | | | | 13.95 | |

2009 | | | | | 88.82 | | | | 89.60 | | | | 11.35 | |

2010 | | | | | 87.34 | | | | 85.86 | | | | (4.17 | ) |

2011 | | | | | 86.07 | | | | 86.60 | | | | 0.86 | |

2012 | | January | | | 86.79 | | | | 86.83 | | | | 0.27 | |

| | February | | | 86.90 | | | | 87.06 | | | | 0.26 | |

| (1) | The weighted average of the exchange rates for annual periods is calculated as the simple average of end of month rates. |

| (2) | As compared to the prior month. |

Source: Bank of Jamaica.

PRESENTATION OF CERTAIN INFORMATION

All references in this annual report on Form 18-K to “Jamaica” and the “Government” are to the Government of Jamaica, unless otherwise indicated. All references to “JA dollars” and “J$” are to Jamaica dollars, all references to “US dollars” and “US$” are to the lawful currency of the United States of America, or US, and all references to “€” are to Euro. Historical amounts translated into JA dollars or US dollars have been converted at historical rates of exchange. References to annual periods (e.g., “2010”) refer to the calendar year ended December 31, and references to fiscal year or FY (e.g., “FY 2009/10” or “FY 2010/11”) refer to Jamaica’s fiscal year ended March 31. All references to “tonnes” are to metric tonnes. Jamaica publishes external economy information, such as external debt and goods and services exported, in US dollars. All international currencies, such as external debt denominated in Euro, are translated into US dollars. Domestic economy information is published by Jamaica in Jamaica dollars. The base year for gross domestic product data contained in this Form 18-K was changed in 2003 from 1986 to 1996. Components contained in tabular information in this annual report on Form 18-K may not add to totals due to rounding. The term “N/A” is used to identify economic or financial data that is not presented for a particular period because it is not applicable to such period and “n.a.” for economic or financial data that is not available.

Statistical information included in this report is the latest official data publicly available. Financial data provided may be subsequently revised in accordance with Jamaica’s ongoing maintenance of its economic data.

D-2

D-3

Summary of Economic Information

| | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | |

| | | 2006 | | | 2007 | | | 2008 | | | 2009 | | | 2010 | |

| | | (in millions of US$, except where noted) | |

DOMESTIC SECTOR(1) | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | |

Nominal GDP | | | 784,171.2 | | | | 885,352.6 | | | | 1,005,435.8 | | | | 1,080,167.6 | | | | 1,173,466.8 | |

Nominal GDP(2) | | | 11,881.4 | | | | 12,812.6 | | | | 13,698.0 | | | | 12,164.0 | | | | 13,441.8 | |

Real Gross Domestic Product (J$ millions)(3) | | | 756,132.8 | | | | 766,972.0 | | | | 760,895.1 | | | | 737,442.2 | | | | 726,840.4 | |

Real GDP(2) | | | 11,456.6 | | | | 11,099.4 | | | | 10,366.4 | | | | 8,304.5 | | | | 8,325.8 | |

Percent Change in Real GDP | | | 2.9 | | | | 1.4 | | | | (0.8 | ) | | | (3.1 | ) | | | (1.4 | ) |

Real GDP per capita (J$/person) | | | 283,930 | | | | 285,959 | | | | 282,608 | | | | 273,248 | | | | 268,623 | |

Inflation | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | |

Consumer Price Index (Percent Change) | | | 5.7 | | | | 16.8 | | | | 16.8 | | | | 10.2 | | | | 11.7 | |

Interest Rates (Percent)(4) | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | |

Weighted Average Loan Rate | | | 17.6 | | | | 17.1 | | | | 16.8 | | | | 16.2 | | | | N/A | |

Weighted Average Deposit Rate | | | 6.6 | | | | 7.0 | | | | 7.4 | | | | 6.4 | | | | N/A | |

Treasury Bill Yield(5) | | | 12.3 | | | | 13.3 | | | | 24.4 | | | | 16.8 | | | | 7.5 | |

Unemployment Rate (Percent)(6) | | | 10.3 | | | | 9.7 | | | | 10.6 | | | | 11.4 | | | | 12.4 | |

EXTERNAL SECTOR | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | |

Average Annual Nominal Exchange Rate (J$/US$) | | | 66.0 | | | | 69.1 | | | | 73.4 | | | | 88.8 | | | | 87.3 | |

Export of Goods | | | 2,133.6 | | | | 2,362.6 | | | | 2,743.9 | | | | 1,387.7 | | | | 1,370.4 | |

Alumina | | | 1,040.5 | | | | 1,193.1 | | | | 1,230.5 | | | | 368.0 | | | | 402.8 | |

Sugar | | | 89.7 | | | | 100.3 | | | | 104.3 | | | | 72.3 | | | | 44.2 | |

Imports of Goods | | | 5,077.0 | | | | 6,203.9 | | | | 7,546.8 | | | | 4,475.6 | | | | 4,629.4 | |

Goods Balance | | | (2,943.4 | ) | | | (3,841.3 | ) | | | (4,802.9 | ) | | | 3,087.9 | | | | (3,259.0 | ) |

Current Account Balance | | | (1,182.9 | ) | | | (2,038.2 | ) | | | (2,793.9 | ) | | | 125.6 | | | | (978.6 | ) |

Net Foreign Direct Investments | | | 796.8 | | | | 751.1 | | | | 1,360.7 | | | | 479.8 | | | | 169.8 | |

Increase/(Decrease) in Reserves | | | 230.2 | | | | (439.9 | ) | | | (104.8 | ) | | | 43.6 | | | | (442.0 | ) |

Net International Reserves of the Bank of Jamaica | | | 2,317.6 | | | | 1,877.7 | | | | 1,772.9 | | | | 1,729.4 | | | | 2,171.4 | |

Weeks of Coverage of Goods Imports(7) | | | 25.2 | | | | 16.4 | | | | 14.8 | | | | 18.9 | | | | 32.3 | |

PUBLIC FINANCE (J$ millions)(8) | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | |

Revenue and Grants | | | 211,364.5 | | | | 252,140.7 | | | | 276,199.8 | | | | 300,200.1 | | | | 314,558.5 | |

Expenditure | | | 248,011.7 | | | | 294,279.6 | | | | 351,521.4 | | | | 421,458.5 | | | | 388,768.0 | |

Fiscal Surplus (Deficit) | | | (36,647.2 | ) | | | (42,138.8 | ) | | | (75,321.6 | ) | | | (121,258.4 | ) | | | (74,209.5 | ) |

Fiscal Surplus (Deficit) as a percent of Nominal GDP | | | (4.7 | ) | | | (4.8 | ) | | | (7.5 | ) | | | (11.2 | ) | | | (6.3 | ) |

Primary Surplus | | | 61,170.7 | | | | 59,584.6 | | | | 49,983.6 | | | | 67,457.2 | | | | 54,145.2 | |

Primary Surplus as a percent of Nominal GDP | | | 7.8 | | | | 6.7 | | | | 5.0 | | | | 6.2 | | | | 4.6 | |

Loan Receipts | | | 161,297.2 | | | | 135,240.3 | | | | 212,148.6 | | | | 299,599.6 | | | | 212,968.9 | |

Amortization | | | 122,049.7 | | | | 106,115.4 | | | | 148,733.2 | | | | 169,514.0 | | | | 102,157.5 | |

Overall Surplus (Deficit) | | | 2,600.3 | | | | (8,472.1 | ) | | | (11,906.2 | ) | | | (8,827.2 | ) | | | 38,084.5 | |

Overall Public Sector Surplus (Deficit)(9) | | | (72,025.4 | ) | | | (67,500.0 | ) | | | (87,251.1 | ) | | | (138,990.5 | ) | | | (124,553.9 | ) |

Overall Public Sector Surplus (Deficit) as a percent of Nominal GDP | | | (9.2 | ) | | | (7.6 | ) | | | (8.7 | ) | | | (12.9 | ) | | | (10.6 | ) |

PUBLIC DEBT | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | |

Domestic Debt (J$ millions)(10) | | | 536,673.1 | | | | 558,426.3 | | | | 608,915.5 | | | | 754,015.1 | | | | 799,964.2 | |

Percent of Nominal GDP | | | 68.4 | | | | 63.1 | | | | 60.6 | | | | 69.8 | | | | 68.2 | |

Public Sector External Debt | | | 5,795.7 | | | | 6,122.8 | | | | 6,343.7 | | | | 6,594.3 | | | | 8,389.5 | |

Percent of Nominal GDP | | | 48.8 | | | | 47.8 | | | | 46.3 | | | | 54.2 | | | | 62.4 | |

Total Public Sector Debt (J$ millions) | | | 925,842.8 | | | | 990,800.9 | | | | 1,119,401.9 | | | | 1,344,864.8 | | | | 1,520,301.0 | |

Percent of Nominal GDP | | | 118.1 | | | | 111.9 | | | | 111.3 | | | | 124.5 | | | | 129.6 | |

External Debt Service Ratio | | | 9.4 | | | | 12.2 | | | | 11.0 | | | | 9.6 | | | | 11.7 | |

TOURISM | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | |

Total Visitor Arrivals | | | 3,015,899 | | | | 2,880,289 | | | | 2,859,534 | | | | 2,753,446 | | | | 2,831,297 | |

Occupancy Rate (% Hotel Rooms) | | | 62.8 | | | | 63.2 | | | | 60.4 | | | | 59.0 | | | | 60.5 | |

Visitor Expenditures(11) | | | 1,871.0 | | | | 1,943.0 | | | | 1,975.5 | | | | 1,925.4 | | | | 2,001.2 | |

| (1) | The gross domestic product series has been revised. This revision was made in order to capture the changing structure of industries in the manufacturing, financial and insurance services, business services and the miscellaneous services sectors. In addition, the base year has been changed from 1996 to 2003. |

| (2) | Calculated using the average annual nominal exchange rate. |

| (3) | At constant 2007 prices |

| (4) | Series discontinued after 2009. |

| (5) | Tenors of Treasury Bills are approximately 182 days. |

| (6) | Includes all persons without jobs, whether actively seeking employment or not. In 2003, three labor force surveys were conducted (in April, July and October). Four labor force surveys were conducted in each of 2005, 2006, 2007 and 2008 (in January, April, July and October). |

| (7) | Calculated on the basis of gross international reserves. |

| (8) | Fiscal year data from April 1 to March 31. For example, 2010 refers to the period April 1, 2010 to March 31, 2011. |

| (9) | Overall Public Sector comprises the central government, the Bank of Jamaica, governmental statutory bodies and authorities and government-owned companies. |

| (10) | Does not include contingent liabilities in the form of guarantees of certain obligations of public entities. |

Source: Bank of Jamaica, Statistical Institute of Jamaica, Ministry of Finance and Planning and Jamaica Tourist Board.

D-4

JAMAICA

History

Originally settled by the Arawak Indians, Jamaica was first visited by Christopher Columbus in 1494 on his second voyage to the New World. Jamaica’s name derives from the Arawak word “Xaymaca,” which means “Land of Wood and Water.” In 1655 Admiral William Penn and General Robert Venables led a British force that conquered the island, ousting the Spaniards. Over the next 40 years, Jamaica became the stronghold of the Caribbean buccaneers who transformed Port Royal, then the island’s commercial center, into the richest city in the New World. The sugar industry, supported to a great extent by slaves transported from Africa until the abolition of slavery in 1834, formed the basis of the island’s economy. During its three centuries as a British colony, Jamaica was variously administered by a governor and a planter-controlled legislature, by British Crown Colony rule from London, England, and by limited representative government in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. The Government granted universal adult suffrage in 1944. From 1958 to 1961, Jamaica was a member of the now-defunct West Indies Federation, which encompassed all of Britain’s Caribbean colonies. Although plans for independence first appeared in the 1940s, internal self-government did not begin until 1959. On August 6, 1962, Jamaica became an independent country within the British Commonwealth.

The historical development of the island has influenced Jamaican national symbols. Jamaica’s flag, a diagonal cross of gold on a green and black background, represents the statement, “The sun shineth, the land is green and the people are strong and creative.” The national crest incorporates the original Arawak inhabitants with the legend “Out of Many, One People,” which reflects the country’s multiracial heritage. Jamaica’s reggae music enjoys international renown.

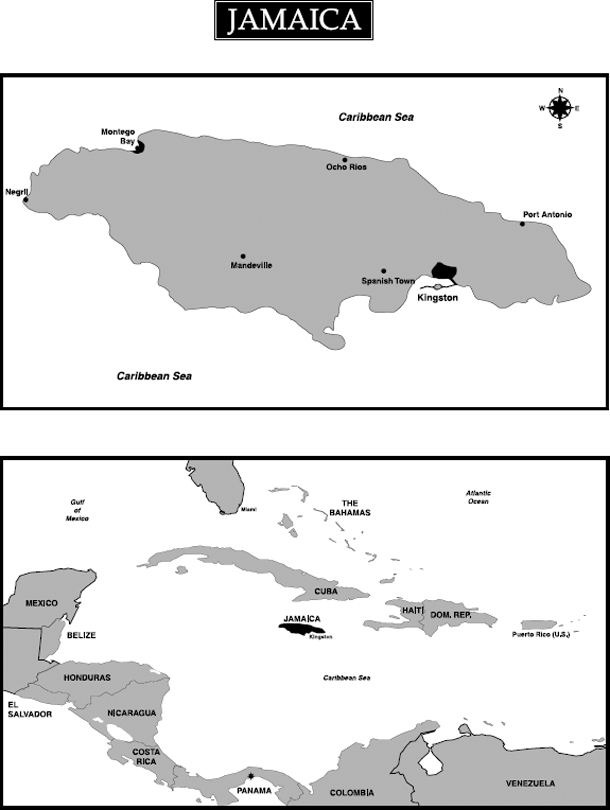

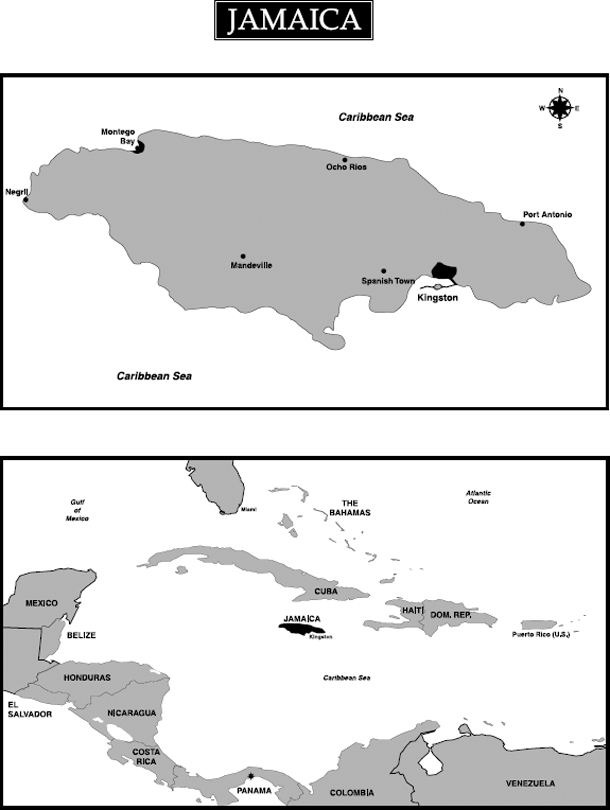

Territory and Population

Jamaica, the third largest island in the Caribbean Sea, is located 558 miles (898 kilometers) southeast of Miami, Florida, 90 miles (144.8 kilometers) south of Cuba and 100 miles (160.9 kilometers) southwest of Haiti. The island has an area of 4,411 square miles (11,420 square kilometers), and its highest point is the Blue Mountain Peak, which rises 7,402 feet (2,256 meters) above sea level. The capital city, Kingston, located on the island’s southeast coast, also serves as Jamaica’s major commercial center. The natural harbor in Kingston is the seventh largest in the world. The country’s second-largest city, Montego Bay, located on the island’s northwest coast, is Jamaica’s main center for tourism. See “The Jamaican Economy—Principal Sectors of the Economy—Tourism.”

From 2007 to 2011, Jamaica’s population grew at an average rate of approximately 0.4% per year. At December 31, 2011, Jamaica’s population was estimated at 2,711,100, a 0.2% increase over the December 31, 2010 population of 2,705,800. The last official census completed in 2001 indicated that 48.0% of Jamaica’s population lives in rural areas while 52.0% lives in urban areas. As of the date of this filing, we are undertaking an official census. The data collection phase of the census was completed on August 31, 2011. The data processing phase is now in progress. Challenges faced in the processing of data have resulted in a revision of the schedule for release of census results. Preliminary results are now expected by April 2012 and final results by September 2012. Jamaica’s official language is English, and a majority of the population speaks a dialect.

Society

Diverse religious beliefs are represented in Jamaica, although Christian denominations predominate. Other major religious groups include adherents to the Rastafari, Bahai, Islamic and Jewish faiths.

Jamaica’s educational system is based on the British system. The school system consists of a pre-primary cycle of two years, followed by a primary cycle of six years and a secondary cycle of five years. In some instances students pursue two years of additional secondary education. The Government of Jamaica has a policy designed to support the mandatory engagement of all children between the ages of three to 18 years in a meaningful learning process and in a structured and regulated setting. It addresses regular attendance at learning institutions for all children as well as exposure to both academic and vocational program at the secondary level. The HEART Trust/NTA is the facilitating and coordinating body for technical and vocational workforce development in Jamaica.

D-5

The Trust provides access to training, development of competence, assessment and certification to working age Jamaicans. It also facilitates career development and employment services island-wide. Training is provided both in the workplace (Enterprise-based), as well as through 28 formal Technical, Vocational and Educational Training (TVET) institutions and over 120 TVET special programs.

The educational system accommodates a variety of public and private schools. Post-secondary education is available to qualified candidates at community colleges, the University of Technology, University College of the Caribbean, Northern Caribbean University, International University of the Caribbean, the Jamaican campus of the University of the West Indies and several private off-shore universities.

In addition to the formal school system, Jamaica has an adult literacy program, which contributed to reducing the illiteracy rate from 32.2% in 1987 to 19.1% in 1999, according to a 1999 survey. No comparable survey has been undertaken since 1999. Data provided by UNESCO using the 1999 data estimates the 2009 literacy rate at 86.8%.

In 2010, the average number of unemployed persons was 154,700, an increase of 7.2% from 144,300 in 2009. The average unemployment rate was 12.4% in 2010, an increase from 11.4% in 2009. See “The Jamaican Economy—Employment and Labor.” The unemployment rate in Jamaica during the past six years has been relatively stable, ranging from a high of 12.4% in 2010 to a low of 9.7% in 2007. Recent macro- and micro-economic developments caused the unemployment rate to increase in 2011. Unemployment in 2011 was 12.7%.

The following table shows selected social indicators applicable to Jamaica for the five years ended December 31, 2010:

Social Indicators

| | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | |

| | | 2006 | | | 2007 | | | 2008 | | | 2009 | | | 2010 | |

Real GDP per capita(1) | | J$ | 283,930 | | | J$ | 285,959 | | | J$ | 282,608 | | | J$ | 273,248 | | | J$ | 268,623 | |

Perinatal Mortality Rate (per thousand)(2) | | | 28.2 | | | | 27.1 | | | | 29.7 | | | | 29.7 | | | | 27.4 | |

| (1) | In constant 2007 prices. |

| (2) | Defined as deaths in government hospitals occurring anytime from 28 weeks of pregnancy until seven days after birth. |

Source: Statistical Institute of Jamaica, Planning Institute of Jamaica and Ministry of Health—Information Unit.

Governmental Structure and Political Parties

The Jamaica (Constitution) Order in Council 1962, or the Constitution, is the supreme law of Jamaica and sets forth the basic framework and legal underpinnings for governmental activity in Jamaica. The Constitution came into effect when Jamaica became an independent country on August 6, 1962, and includes provisions that safeguard the fundamental freedoms of the individual. While a simple majority of Parliament can enact amendments to the Constitution, certain amendments require ratification by a two-thirds majority in both houses of Parliament, and amendments altering fundamental rights and freedoms require the additional approval of a national referendum.

Jamaica is a parliamentary democracy based upon the British Westminster model and is a member of the British Commonwealth. The Head of State is the British Monarch, who is represented locally by the Governor-General of Jamaica. Traditionally, the British Monarch appoints the Governor-General upon the recommendation of Jamaica’s Prime Minister. The actions of the Governor-General are, in most cases, of a purely formal and ceremonial nature. General elections are constitutionally due every five years, at which time all seats in the House of Representatives will be up for election. The Constitution permits the Prime Minister to call elections at any time within or shortly beyond the five-year period, consistent with the Westminster model.

National legislative power is vested in a bicameral Parliament composed of a House of Representatives and a Senate. The House of Representatives comprises 60 members elected by the people in the general elections. The Senate comprises 21 members appointed by the Governor-General, 13 of whom are appointed on the advice of the

D-6

Prime Minister and eight of whom are appointed on the advice of the Leader of the Opposition. The President of the Senate is elected by its members. The members of the House of Representatives select their own chairman, known as the Speaker. The Prime Minister, usually the member most likely to command the support of the majority of the members of the House of Representatives, is appointed by the Governor-General.

In addition to the national governing bodies, local government is administered through 12 parish councils and a statutory corporation that administers the Kingston and St. Andrew (KSAC) areas and the Municipality of Portmore. The results of the last local government election, which took place in December 2007, accorded the ruling Jamaica Labour Party, or JLP, nine of the 12 parish councils and the KSAC. Both the JLP and the People’s National Party, or PNP, shared the St. Ann Parish Council. The PNP won the Municipality of Portmore.

The principal policy-making body of the Government is the Cabinet, which is responsible for the general direction and control of Jamaica and whose members are collectively accountable to Parliament. The Cabinet consists of the Prime Minister and no fewer than 11 other members of the two Houses of Parliament. No fewer than two, and no more than four members must be selected from the Senate. The Governor-General appoints members of the Cabinet upon the recommendation of the Prime Minister.

The Jamaican judicial system is based on English common law and practice and consists of a Supreme Court, a Court of Appeal and local courts. Final appeals are made to the Judicial Committee of the Privy Council in the United Kingdom, or UK. A number of Caribbean nations, including Jamaica, are currently discussing the establishment of a Caribbean Court of Justice to replace the Judicial Committee of the Privy Council for those nations. Jamaica has signed an agreement to establish the Caribbean Court of Justice. In April 2005, Jamaica passed the Caribbean Court of Justice (Original Jurisdiction) Act 2005. The Act provides for the implementation of the provisions of the Agreement establishing the Caribbean Court of Justice in its original jurisdiction. The Caribbean Court of Justice, in its original jurisdiction, will hear and determine matters relating to the interpretation and application of the Revised Treaty of Chaguaramas establishing the Caribbean Community and Common Market.

Two major political parties dominate Jamaica’s political system. From Jamaica’s independence on August 6, 1962 until 1972, the JLP formed the government; then the PNP assumed power in 1972. In late 1980, the JLP returned to power until February 1989, when Michael Manley led the PNP to victory and became Prime Minister. In 1992, Prime Minister Manley resigned as Prime Minister and leader of the PNP and was succeeded by Percival James (“P. J.”) Patterson. The PNP won the 1993 general election and Mr. Patterson was returned as Prime Minister. In 1995, a former Chairman of the JLP formed a third political party, the National Democratic Movement. In the 1997 general election, the PNP won 51.7% of the votes cast, and P. J. Patterson returned to the office of Prime Minister. In March 2006, Prime Minister Patterson resigned as Prime Minister and leader of the PNP and was succeeded by Portia Simpson Miller.

In the September 3, 2007 general elections, the JLP won 49.98% of the votes cast, and Bruce Golding became Prime Minister. The changes in the leadership of the country had no material effect on the economy of Jamaica. On September 25, 2011, Mr. Golding announced that he would not be seeking re-election, and Andrew Holness succeeded Mr. Golding as Prime Minister and leader of the JLP on October 23, 2011.

Jamaica held its most recent general election on December 29, 2011. As a result of that election, the PNP won 53.0% of the votes cast, and Portia Simpson Miller became Prime Minister. The Jamaican Constitution requires that a general election be held every five years, at which time all seats in the House of Representatives will be up for election. Given that the last general election was December 29, 2011, an election is to be constitutionally held by December 2016. However, the Prime Minister is constitutionally permitted to call an election at any time before this date.

D-7

The following table shows the parliamentary electoral results for the past seven general elections:

Parliamentary Electoral Results

| | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | |

| | | 1983(1) | | | 1989 | | | 1993 | | | 1997 | | | 2002 | | | 2007 | | | 2011(2) | |

| | | (number of representatives) | |

| | | | | | | |

People’s National Party | | | 0 | | | | 45 | | | | 52 | | | | 51 | | | | 34 | | | | 28 | | | | 42 | |

Jamaica Labour Party | | | 60 | | | | 15 | | | | 8 | | | | 9 | | | | 26 | | | | 32 | | | | 21 | |

| (1) | The People’s National Party did not contest the 1983 election, and the eight opposition senators were appointed as independents by the Governor-General. |

| (2) | Following a Boundaries Revision exercise conducted between April 2008 and March 2010, the number of constituencies (parliamentary seats) was increased from sixty to sixty-three. |

Source: Electoral Commission of Jamaica

In recognition of the jubilee year of Jamaican independence, the Administration of Prime Minister Simpson Miller has proposed to begin the process of detaching Jamaica from the British Monarchy and to have Jamaica become a republic with an indigenous president as its Head of State. An important agenda item for the Administration in this respect is to establish the Caribbean Court of Justice as its final appellate jurisdiction, replacing the Judicial Committee of the Privy Council. The Administration also intends to broaden and deepen Jamaican input into the regional integration movement. See “—International Relationships—Caribbean Community and Common Market (CARICOM).”

International Relationships

Jamaica maintains diplomatic relations with almost every nation in the world. Jamaica is a member of the United Nations and its affiliated institutions, including the Food and Agriculture Organization, the International Monetary Fund, the World Bank Group, the World Health Organization, the World Tourism Organization, the World Intellectual Property Organization (WIPO), the International Seabed Authority and the United Nations Environment Program. It is also a member of several other regional and international bodies, including the World Trade Organization (WTO); the African, Caribbean Pacific Group of States; the Association of Caribbean States; the Caribbean Community and Common Market (CARICOM); the Commonwealth; the Latin American Economic System; and the Organization of American States.

Jamaica is a signatory to the Cotonou Partnership Agreement and is also a beneficiary of the Caribbean Basin Economic Recovery Act and the Caribbean-Canada Trade Agreement (CARIBCAN). In addition, as a member of the United Nations bloc of developing countries known as the Group of 77, Jamaica is eligible for the Generalized System of Preferences. Jamaica is also a member of the Group of 15, a group of 18 states focused on cooperation among developing countries in the areas of trade, investment and technology.

Jamaica receives preferential tariff treatment on most of its products pursuant to, among others, the trade agreements described below.

WTO—Doha Development Round

Jamaica has been participating in the WTO’s Doha Development Round, aimed at further liberalizing trade at the global level, since it was launched in Doha, Qatar in 2001. These negotiations were scheduled to be concluded in 2005 but are currently at an impasse due to various unresolved issues. The eighth WTO Ministerial Conference (MC8) was held in Geneva, Switzerland from December 15-17, 2011. The Conference addressed issues under its existing mandate relating to: (1) the Importance of the Multilateral Trading System (MTS); (2) Trade and Development; and (3) the Doha Development Agenda (DDA). Among the decisions adopted that were of particular interest to Jamaica were those on the Work Programme on Small Economies and the Trade Policy Review Mechanism. The WTO is to continue with its regular work program throughout the year 2012 and also continue efforts to advance the Doha Development Agenda negotiations to the extent possible.

D-8

Caribbean Community and Common Market (CARICOM)

The Treaty of Chaguaramas establishing the CARICOM was signed in 1973 among 13 English-speaking Caribbean countries. These countries are: Antigua, The Bahamas, Barbados, Belize, Dominica, Grenada, Guyana, Jamaica, Montserrat, St. Kitts-Nevis-Anguilla, St. Lucia, St. Vincent and Trinidad and Tobago. The main focus of the Treaty has been to deepen economic integration and increase trade among CARICOM Member States. In pursuing these objectives, the Treaty made provisions for, inter alia:

| | • | | the promotion of economic integration among CARICOM Member States, including the establishment of a common market regime and the integration of economic activities; |

| | • | | the coordination of CARICOM Member States’ foreign policies; and |

| | • | | the engagement of CARICOM Member States in functional cooperation activities aimed at improving the effectiveness and efficiency of certain common services, as well as the advancement of social, cultural and technological development. |

The Treaty also created “Community Organs” to monitor the activities and initiatives mandated. Additionally, in fulfilling the provisions of the Treaty, CARICOM Member States established common institutions for the purposes of policy formulation and cooperation aimed at improving the provision of services such as education and health care. As well, CARICOM Member States have cooperated in other important areas such as labor, agriculture, transportation, communication, tourism and disaster preparedness.

Between 1997 and 2001, Member States negotiated a revision of the Treaty, based on recommendations made by the West Indian Commission in 1992, to expand the scope of the Common Market by establishing a single market and economy. Consequently, the Revised Treaty of Chaguaramas establishing the Caribbean Community including the CARICOM Single Market and Economy (CSME) was signed by the following Caribbean countries in July 2001: Antigua and Barbuda, The Bahamas, Barbados, Belize, Dominica, Grenada, Guyana, Jamaica, Montserrat, St. Kitts and Nevis, St. Lucia, St. Vincent and the Grenadines, Suriname and Trinidad and Tobago. Haiti later signed the Revised Treaty of Chaguaramas on July 2, 2002.

The Revised Treaty seeks to establish a common economic region among CARICOM Member States which would provide for the free movement of goods, services, people (to live, work and do business), capital, and technology, and would provide CSME nationals with the right to establish businesses and acquire property in any CARICOM Member State participating in the CSME. Additionally, the Revised Treaty provides for the harmonization of fiscal and monetary policies, including the establishment of a common currency. In January 2006, the implementation of the provisions of the CARICOM Single Market (CSM) was initiated by Jamaica, Barbados, Belize, Guyana, Suriname and Trinidad and Tobago, that is, the provisions enabling the free movement of goods, services, people and capital. Other Member States started the CSM implementation process in July 2006. The Bahamas, Haiti and Montserrat are members of the Caribbean Community but are not yet participating in the CSME. Whereas the CSME Member States have made progress in the implementation of the CSM, exploratory work is underway to inform the implementation of the CARICOM Single Economy (CSE) provisions, that is, the provisions for the harmonization of economic, fiscal and monetary measures and policies among Member States. In the meantime, negotiations are underway for a CARICOM Financial Services Agreement to remove all regulations, the existence of which negatively affects intra-CARICOM trade in financial services. Negotiations are also underway to complete a CARICOM Investment Code which will help to facilitate the establishment of a Community Investment Policy and creates a framework for the designation of CARICOM as a single investment location. In this context, the CARICOM Investment Code is to establish common standards of treatment for extra-CARICOM investors.

Jamaica remains committed to the mandate of the Revised Treaty of Chaguaramas. A 2009 Audit conducted by the CARICOM Secretariat indicates that Jamaica is far advanced in implementing its obligations under the Revised Treaty.

D-9

Caribbean-Canada Trade Agreement (CARIBCAN)

The CARIBCAN is an agreement entered into by Canada and the CARICOM countries in 1986. This agreement established a program for trade, investment and industrial cooperation, and features the unilateral extension by Canada of preferential duty-free access to the Canadian market for many imports from CARICOM countries. CARIBCAN’s basic objectives are to enhance the Caribbean region’s existing trade and export earnings, improve its trade and economic development prospects, promote new investment opportunities, and encourage enhanced economic integration and cooperation within the region. This program, after running its course for more than twenty years, has been slated to be replaced by the CARICOM-Canada Trade and Development Agreement, with reciprocal equal access for Canadian companies to the Caribbean market. The negotiations commenced in late 2009. Since 2009, there have been three rounds of negotiations between Canada and CARICOM with a view to convening a fourth round, but negotiations have not been concluded.

The Caribbean Basin Initiative

The Caribbean Basin Initiative, or CBI, which was initially launched in 1983 with the enactment of the Caribbean Basin Economic Recovery Act, was amended in 1990 to increase market access to the United States. The benefits under the CBERA are of indefinite duration. In 2000, the United States further expanded the CBI with the enactment of the Caribbean Basin Trade Partnership Act (CBTPA). The CBTPA provides preferential access for a number of products previously excluded from the CBI. The CBTPA, which was due to expire on September 30, 2010, was recently extended until September 30, 2020.

Generalized System of Preferences

Under the aegis of the United Nations Conference on Trade and Development, the Generalized System of Preferences was designed to afford developing countries preferential access for a wide range of their exports to the markets of developed countries. The Generalized System of Preferences is an export-promotion tool with the objectives of increasing the export earnings of developing countries, promoting industrialization in developing countries and accelerating the rate of economic growth in developing countries.

Cotonou Partnership Agreement

In February 2000, the European Union and the African Caribbean Pacific group of countries, or ACP, concluded negotiations for a new 20-year trade, industrial, financial and technical cooperation agreement. Jamaica ratified the new agreement, known as the Cotonou Participation Agreement, in February 2001 and, following ratification by 75% of ACP Member States and all EU members, the agreement formally entered into force on April 1, 2003. The agreement was reviewed in 2005 and 2010. The trade provisions of the Cotonou Partnership Agreement have been replaced by the CARIFORUM-EC Partnership Agreement, as described below.

The CARIFORUM-EC Partnership Agreement

The CARIFORUM-EC Economic Partnership Agreement (EPA) was signed by Jamaica and other CARIFORUM Countries, that is, other CARICOM countries and the Dominican Republic, in October of 2008. The duration of the EPA is indefinite, and provides exporters of most CARIFORUM-originated goods with duty-free and quota-free access to the EU market. The coverage of the agreement extends to include traditional exports, such as sugar, bananas, rum and rice, which will ultimately enter the EU duty-free and quota-free.

The EU’s preferential system for bananas ended on January 1, 2006, and the sugar regime which existed under the Cotonou Partnership Agreement ended on September 30, 2009. However, under the EPA, bananas from CARIFORUM countries enter the EU quota-free and duty-free, and since October 1, 2009, CARIFORUM sugar exporters have duty-free and quota-free access to the EU market under a managed system which will last until 2015, when the conditions will be removed. The agreement also requires the EU to remove restrictions on CARIFORUM’s services exports, beginning with the liberalization of 29 sectors and sub-sectors.

D-10

At the same time, the EPA requires Jamaica and other CARIFORUM countries to remove all tariffs/duties on 86.9% of the value of imports from the EU (90.2% of tariff lines) on a phased basis over a 25-year period.

The EPA establishes provisions to administer trade related issues between the parties. These trade-related issues are primarily in relation to agriculture and fisheries, sanitary and phyto-sanitary standards, customs and trade facilitation, investment facilitation, intellectual property rights management, competition policy administration, electronic commerce and personal data protection. The agreement goes further to provide for parties to undertake development cooperation in a number of areas, ranging from the development of supply-side capacity, including the development of trade-related infrastructure, to the enhancement of the tourism sector and culture cooperation.

The agreement is being provisionally applied by Jamaica.

D-11

THE JAMAICAN ECONOMY

General

Jamaica operates as a mixed, free market economy with state enterprises as well as private sector businesses. Major sectors of the Jamaican economy include agriculture, mining, manufacturing, tourism and financial and insurance services. As an open economy, Jamaica is well integrated into the global economy with intraregional trade contributing prominently to overall economic activity.

Since the early 1980s, successive governments have implemented structural reforms aimed at fostering private sector activity and increasing the role of market forces in resource allocation. During this period, a large share of the economy has been returned to private sector ownership through divestment and privatization programs in areas such as agriculture, tourism, transportation, banking, manufacturing and communications. See “—Privatization.” Deregulation of markets, the elimination of price subsidies and price controls and the reduction and removal of trade barriers have reduced or eliminated production disincentives and anti-export biases.

In the early 1990s, the reform process in Jamaica gained momentum with, among other developments, the liberalization of the foreign exchange market and the overhaul and simplification of the tax system. In addition to changes in personal income tax and corporate tax regimes, a number of indirect taxes were removed and replaced with a value-added tax. The Tax Administration Reform Project implemented in 1994 was aimed at broadening the tax base, facilitating voluntary compliance with the tax laws, improving the effectiveness of tax administration and tax collection and controlling tax evasion. To enhance compliance, Jamaica implemented a Tax Registration Number system aimed at broadening the tax base through the assignment of identification numbers to individuals and businesses. See “Public Finance—Tax Reform.”

In 2009, Jamaica introduced a new strategic plan for the country’s growth and development—Vision 2030 Jamaica. This strategic plan aims at enabling Jamaica to achieve developed country status by 2030, and is based on the following seven guiding principles: transformational leadership, partnership, transparency and accountability, social cohesion, equity, sustainability, and urban and rural development. Vision 2030 Jamaica seeks to redefine the strategic direction of Jamaica by moving from dependence on lower forms of capital, such as tourism and basic agricultural commodities, to higher forms of capital, such as cultural, human, knowledge and institutional capital stocks. Despite these prior initiatives, challenges for Jamaican business owners remain. See “—Principal Sectors of the Economy.”

The Administration of Prime Minister Simpson Miller remains committed to the framework of the Vision 2030 Jamaica national development plan, has declared its support for the Growth Inducement Strategy, which is the short-medium term elaboration of specific strategies consistent with the Vision 2030 framework, and has articulated the need for specific short-term emergency employment measures. The Administration plans to use state resources to stimulate employment through the Jamaica Emergency Employment Programme (JEEP) in the short and medium term. While the Administration’s policies are based on the principle that the private sector is a major participant in shaping the Jamaican economy, the Administration also believes that the Government must act to stimulate growth and to restore confidence in Jamaica during times of crisis. The Administration intends to use JEEP in a transparent and non-partisan manner to improve critical areas, such as the infrastructure and the environment, which it believes will support economic growth. The Administration has also announced its intention to pursue a tight fiscal policy, reduce Jamaica’s debt-to-GDP ratio, maintain the key macro-economic fundamentals; and be prudent in Jamaica’s debt management.

Impact of Global Economic Crisis

Beginning in the second half of 2007, the short-term funding markets in the United States encountered several issues, leading to liquidity disruptions in various markets. In particular, subprime mortgage loans in the United States began to face increased rates of delinquency, foreclosure and loss. These and other related events have had a significant adverse impact on the international economic environment, including the global credit, commodities and financial markets as a whole. Although Jamaica has limited exposure to subprime assets and financially distressed international financial institutions, the country was affected by the contraction of liquidity in the international

D-12

financial markets, the volatility in commodity prices, and the contraction in growth in some of Jamaica’s most important tourism clientele and export markets. Gross domestic product, or GDP, contracted in 2009 and 2010 as compared to 2008, and 2009, respectively. In addition, continuing deteriorated market conditions have also had adverse effects on the Jamaican economy; however in 2010, certain sectors of the Jamaican economy experienced a recovery when compared to 2009. The adverse effects the continuing marketing conditions have had on the Jamaican economy include:

| | • | | a decrease in exports and domestic demand in 2009, when compared to 2008; however in 2010, exports increased and domestic demand declined compared to in 2009; |

| | • | | a decrease in net foreign direct investment inflows; however, in the first quarter of 2011, foreign direct investment increased compared to the same period in 2010; |

| | • | | a decrease in tourist expenditures in 2009, when compared to 2008; however in 2010, tourist expenditures increased compared to 2009; |

| | • | | a decrease in remittances from Jamaicans living abroad in 2008 when compared to 2009; however in 2010, remittances from Jamaicans living abroad increased compared to 2009; |

| | • | | depreciation of the Jamaican dollar against the US dollar from J$80.47, as of December 31, 2008 to J$89.60 as of December 31, 2009; however, in 2010 the Jamaican dollar appreciated against the US dollar to 85.86 as of December 31, 2010; |

| | • | | a decrease in credit availability as financial intermediaries adopted more restrictive lending policies and access to foreign credit decreases; and |

| | • | | a decrease in the prices of international commodities, which specifically had an adverse effect on the production and prices of bauxite and alumina, in 2009; however in 2010, production of bauxite and alumina and the prices of alumina increased compared to 2009. |

Beginning in the last quarter of 2008, the government took preventive fiscal and monetary actions in response to the then current adverse international economic environment. It announced that it had taken certain steps to address the impact of the global economic crisis. These steps included the following:

| | • | | provision of support to the tourism sector to mitigate cash flow constraints and help sustain activity through the extension of credit lines, tax cuts and other mechanisms; |

| | • | | provision of liquidity to Jamaican financial institutions through the Bank of Jamaica, providing US$168.8 million in order to satisfy financial agreements related to payments on Government global bonds held with institutions abroad; this amount was repaid by September 30, 2010; |

| | • | | provision of support to small businesses through the extension of credit lines, tax cuts and other mechanisms; |

| | • | | provision of support to the productive and manufacturing sectors through the extension of credit lines, the temporary removal of Customs User Fees payable on capital goods and raw materials, tax cuts and other mechanisms; |

| | • | | entry into a US$300 million credit facility agreement with the Inter-American Development Bank (IADB) to provide loans to the productive sector through commercial banks and the Export-Import Bank, of which approximately only US$100 million was used; and |

| | • | | provision of support to individuals through an increase in the income tax threshold. |

D-13

See “Public Finance—Tax Reform.”

IMF Standby Arrangement

In February 2010, Jamaica entered into a 27-month Standby Arrangement (SBA), with the International Monetary Fund (IMF) in the amount of SDR 820.5 million (approximately US$1.27 billion). Prior to the execution of the SBA, the Government had to take several actions, including adopting a tax policy package yielding approximately 2% of GDP; completing the Jamaica Debt Exchange (JDX); and reaching an agreement regarding the divestment of Air Jamaica, all of which the Government completed. See “ Public Sector Indebtedness—The Jamaica Debt Exchange,” “Public Finance—Tax Reform” and “The Jamaican Economy—Privatization.” The SBA supports Jamaica’s economic program aimed at restoring macroeconomic stability and creating conditions for improved growth. This program includes critical steps and policy reforms to tackle fiscal and debt imbalances and other underlying vulnerabilities. The program was designed to assist the country in the establishment of fiscal and debt sustainability over the medium term. As such, the program focuses on facilitating tax reform, rationalization of public bodies, rationalization of the public sector and reform of public financial systems.

To achieve these goals, the program focuses on a three-pronged strategy:

| | • | | comprehensive debt management; and |

| | • | | reforms to further strengthen the financial system. |

As part of the SBA, Jamaica undertook a structural reform agenda, which included reforms to fiscal institutions, public entities, debt management, and financial sectors. As part of these reforms Jamaica passed the Fiscal Responsibility Framework, launched its strategic and comprehensive domestic liability management program, and implement a variety of reforms impacting the financial system. See “—IMF Standby Agreement—Fiscal Consolidation,” “—IMF Standby Agreement—Comprehensive Debt Management,” and “—IMF Standby Agreement—Legal Reforms to Financial System.”

The SBA provided for eight reviews by the IMF Executive Board before its expiration in May 2012. The third review was completed in January 2011 and it was agreed that the fourth and fifth reviews would be combined and completed by June 2011. However, those reviews were not completed due mainly to concerns by the management and staff of the IMF that the fiscal consolidation and the achievement of structural benchmarks necessary to achieve the medium-term debt sustainability objective of the program were not taking place. Key fiscal indicators in FY 2010/11 fell short of the milestones that would have signaled satisfactory progress towards the program objectives. In this regard, the Primary Balance to GDP ratio was 4.5% relative to an IMF-SBA target of 4.7%. The Fiscal Deficit was, however, 6.2% of GDP relative to the SBA target of 6.4% of GDP. The deviation of the primary balance from target was plausibly—extreme weather, expenditure on a civil emergency, and complications surrounding the divestment of state assets. The effort that was made to contain the deviation would have supported a satisfactory review of performance up to March 2011. Nonetheless, in the absence of the scheduled reviews, no further performance targets were established to form the basis of further drawdowns. The SBA will therefore expire in May 2012, with only US$849.97 million in drawdowns (special drawing rights (SDR) 541.8 million). This has resulted in the non-disbursement of multilateral funding including US$220 million from the Inter-American Development Bank (IDB). Loan commitments from the IDB, the World Bank, and the Caribbean Development Bank under the original IMF SBA amounted to US$1.1 billion, compared to the actual drawdown of US$1.0 billion

On January 24, 2012, a team from the Western Hemisphere Department of the IMF ended a five-day visit to Jamaica. During that visit, the team shared with the Jamaican authorities concerns about the vulnerabilities of the Jamaican economy, against the background of higher risks from lower growth in the world economy as well as in the light of current realities in Jamaica; including a reduction in the primary surplus of the Government that was targeted for this fiscal year and a rise of the overall deficit of the public sector. The team noted that, based on current projections, the primary surplus would be approximately 1.5% of GDP below what was targeted in the budget, which the team interpreted to be an unsustainable position that would lead to a worsening of Jamaica’s already burdensome national debt. As a result, the Government has begun to work on a set of economic policies to address the risks posed by both the global environment and the worsening fiscal realities in Jamaica.

D-14

The Administration of Prime Minister Simpson Miller has announced a policy which includes reengaging the IMF for an Extended Fund Facility (an “EFF”) to replace the SBA. EFFs are typically three years in duration with the possibility of an extension into a fourth year. As with the SBA, the EFF would support Jamaica’s economic program aimed at restoring macroeconomic stability and creating conditions for improved growth. The repayment period would be longer for an EFF than the SBA, typically between 4 1/2 to 10 years. Each disbursement under an EFF is generally repaid in twelve equal semiannual installments. The EFF program is designed to support countries’ economic programs aimed at moving toward a stable and sustainable macroeconomic position consistent with strong and durable poverty reduction and growth. The Government is of the view that an effective program with the IMF, as well as robust partnerships with other international financial institutions, is an essential element in maintaining confidence domestically and internationally while undertaking the necessary economic reforms. The Government expects to begin negotiations during March 2012 with the IMF on such a successor agreement to the SBA.

Fiscal Consolidation

Jamaica committed to fiscal discipline by adopting a number of programs, the first of which is the Fiscal Responsibility Framework, or FRF. The FRF requires the Government to adopt a number of initiatives including the following:

| | • | | preparing medium-term goals and explaining deviations, should there be any; |

| | • | | more comprehensive reporting in several areas and empowering the Financial Secretary to obtain fiscal information of all public sector entities; |

| | • | | strengthening accountability to Parliament in areas such as corporate plans and budgets of public bodies and increasing oversight of overall fiscal policy; |

| | • | | establishing quantitative ceilings on debt stock, fiscal balance and wages within a specific time frame (initially March 2016); and |

| | • | | requiring the Ministry of Finance and Planning to present to Parliament, at the time of the annual budget, a medium-term fiscal policy framework paper with plans and policies for developing the country. |

The FRF is the centerpiece to a number of other initiatives aimed at achieving fiscal consolidation. These other initiatives include a medium-term expenditure framework, the establishment of a centralized treasury management system and the enhancement and consolidation of legislation governing debt management generally.

Comprehensive Debt Management

On January 14, 2010, the Government of Jamaica launched its strategic and comprehensive domestic liability management program, marketed as the Jamaica Debt Exchange, or JDX, for domestic securities only. The results of the JDX revealed a participation rate of approximately 99.2% with a 100% participation rate from financial institutions. This level of success represented an exchange of approximately J$695.6 billion in eligible bonds.

The immediate benefits of the JDX were the realignment of the domestic debt portfolio, which saw a significant reduction in maturities over the next three years; substantial cost savings through the reduction in the projected interest cost for FY 2010/11 of J$17.1 billon (i.e., US$190.7 million, or 15.2% of interest cost); extension of amortization equal to J$148.6 billion (or US$1.66 billion) in FY 2010/11; the creation of 25 new benchmark bonds in exchange for over 350 smaller and illiquid bonds; the removal of US Dollar Indexed Bonds and the introduction of new CPI-Indexed Bonds into the domestic portfolio; and an increase in the fixed rate component of the domestic debt portfolio. See “Public Sector Indebtedness—The Jamaica Debt Exchange.”

D-15

In addition to implementing the JDX, the Government has an on-going debt management strategy that includes the following:

| | • | | increasing the fixed-rate proportion of the domestic debt stock; |

| | • | | reducing foreign currency domestic debt; |

| | • | | focusing on benchmark bonds to enhance liquidity; |

| | • | | continuing to develop the secondary capital market; |

| | • | | increasing the transparency and predictability of debt issuance and operations; |

| | • | | continuing to engage multilateral institutions and bilateral creditors; and |

| | • | | enhancing and consolidating legislation governing debt management generally. |

Legal Reforms to Financial System

The Government plans to implement a variety of reforms impacting the financial system. These include the following:

| | • | | introducing an omnibus banking law that will allow for more effective supervision of financial conglomerates, including harmonization of the prudential standards that apply to commercial banks, merchant banks and building societies; |

| | • | | amending the Bank of Jamaica Act to establish a legal framework to provide that the Bank of Jamaica have responsibility for overall financial stability; |

| | • | | reforming of deposit taking institutions to enhance capital rules to address market risks; |

| | • | | reforming of the securities dealer sector to strengthen its ability to withstand shocks going forward; and |

| | • | | continuing to strengthen the regulatory and supervisory framework of the securities dealer sector to enhance capitalization and margin requirements. |

Repayment of funds disbursed under the SBA is slated to commence in June 2013, with the final payment occurring in February 2017. The executive board of the IMF concluded reviews of Jamaica’s economic performance under the SBA for the quarters ending March 2010, June 2010 and September 2010. Completion of these reviews enabled the immediate disbursement of additional amounts under the SBA, bringing total disbursements under the arrangement to SDR 541.8 million (about US$849.97 million) as of May 2011. Reviews of Jamaica’s economic performance by the IMF for the quarters ending December 2010 and March 2011 were delayed over discussions on the medium-term fiscal program and, with the formal expiry of the SBA in May 2012, will not take place. Jamaica is continuing discussion with the IMF with respect to the medium term program in the context of an Article IV review and expects to begin negotiations during March 2012 on a successor arrangement to the SBA. See “—IMF Standby Arrangement.”

Gross Domestic Product

The Jamaican economy continued to be affected by the adverse effects of the global economic crisis and in that context gross domestic product, or GDP, declined by 1.4% in 2010 when compared with 2009. GDP declined by 3.1% in 2009 compared to 2008. The decline in 2010 was mainly the result of a 1.8% decrease in the goods producing sectors, and a 1.3% decline in the services sector. The decrease in the goods producing sectors was

D-16

primarily a result of decreases in the mining and quarrying, the construction and the manufacturing sectors. The mining and quarrying sector declined by 4.3% in 2010 as compared to 2009, primarily due to a decline in bauxite and alumina. Alumina production fell from 1,773.6 million tonnes in 2009 to 1,590.7 million tonnes in 2010, a 10.3% decline. During the first quarter of 2010, gross value added for the mining and quarrying sector fell by 42.1% as the industry continued to feel the effects of the global economic recession. As global aluminum demand increased in the subsequent quarters of 2010, the sector experienced a significant improvement, increasing 1.4% in the second quarter, 30.3% in the third quarter and 22.4% in the fourth quarter. This contributed to the reopening of one of the three alumina plants that were closed during 2009 and a return to full capacity utilization in the bauxite industry. In 2010, manufacturing declined by 2.9% when compared to 2009, while the construction sector contracted by 1.0% compared to 2009. These decreases were also primarily a result of the slow pace of recovery in the global economy and contraction in domestic demand. The agriculture, forestry and fishing industry decline by 0.4% in 2010 when compared to 2009.

The decrease in the services sectors in 2010 was mainly due to decreases of 4.3% in electricity and water, 4.8% in finance and insurance services, 2.0% in the transport, storage and communication sector, 3.4% in wholesale and retail trade, 1.2% in real estate, renting and business activities, and 1.5% in other services, each as compared to 2009. These decreases were offset in part by increases in the hotels and restaurants sector in 2010 as compared to 2009. The finance and insurance sector was affected by the contraction in the local economy as well as the introduction of the JDX in the early part of 2010. The downturn in transport, storage and communication was caused primarily by declines in air and land transport as well as post and telecommunications. The increase in 2010 in the hotels and restaurants sector was primarily due to increased airlift, aggressive promotion, and discount pricing, as well as expanded room capacity.

GDP increased 1.6% during the first nine months of 2011 to J$553.4 billion as compared to J$545.0 billion during the same period in 2010, mainly as a result of increases in both the goods producing and services sectors of 4.6% and 0.6% respectively. During the first nine months of 2011, industries recording growth as compared to the same period in 2010 included the mining and quarrying sector, which grew by 24.8%, the agriculture forestry and fishing sector, which grew by 9.2%, manufacturing, which grew by 0.2%, electricity and water, which grew by 0.9%, construction, which grew by 0.6%, producers of government services, which grew by 0.2%, real estate renting and business activities, which grew by 0.4%, the hotels and restaurants sector, which grew by 4.4%, and transport, storage and communication, which grew by 0.1%. Value added for wholesale and retail trade; repairs and installation of machinery and other services remained relatively unchanged during the first nine months of 2011 as compared to the same period in 2010. The finance and insurance services sector, however, declined by 1.1% during the first nine months of 2011 as compared to the same period in 2010.

There are no commercial reserves of oil, gas or coal in Jamaica, and the country receives approximately 90.9% of its energy requirements from imported oil. Of the remaining 9.1% of Jamaica’s energy requirements, the country receives 7.4% from biomass, 1.0% from bioethanol, 0.4% from hydropower generation and 0.2% from wind and 0.1% from solar generation. The Government has been in negotiations with the governments of the Republic of Trinidad and Tobago and the Bolivarian Republic of Venezuela to have natural gas exported from each country to Jamaica. However, no agreements have been reached and no construction has begun of any natural gas import facilities. Increases in global oil prices may have a significant adverse effect on the Jamaican economy, particularly the competitiveness of the mining and quarrying and manufacturing sectors. Domestic energy output is limited to small hydropower plants, wood burning and the fiber left over from milled sugar cane. The main sources of imports of fuel are the Bolivarian Republic of Venezuela, the United Mexican States and the United States of America.

The pace of Jamaica’s economic growth has been impacted by the amount of government spending for interest payments. There has been, however, a declining trend in interest costs. In FY 2010/2011, interest payments accounted for 40.1% of total revenues and 10.5% of GDP. This compares favorably to FY 2009/10 when interest payments accounted for 62.9% of total revenue and 17% of GDP. Interest cost as a percentage of total revenues has averaged 49.5% over the last three years. This favorable outturn of declining interest costs to revenue is expected to continue through the medium-term, thus creating fiscal space to allow for improvements to infrastructure, increased economic efficiencies, and poverty reduction. See “Public Sector Indebtedness.”

D-17

The following table shows real GDP by economic sectors at constant 2007 prices for the five years ended December 31, 2010:

Sectoral Origin of Gross Domestic Product(1)

| | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | |

| | | 2006 | | | 2007 | | | 2008 | | | 2009 | | | 2010 | |

| | | Amount | | | % of

Total | | | Amount | | | % of

Total | | | Amount | | | % of

Total | | | Amount | | | % of

Total | | | Amount | | | % of

Total | |

| | | (in millions of J$ at constant 2007 prices, except percentages) | |

| | | | | | | | | | |

Agriculture, Forestry and Fishing: | | | 44,503 | | | | 5.9 | | | | 40,895 | | | | 5.3 | | | | 38,369 | | | | 5.0 | | | | 43,929 | | | | 6.0 | | | | 43,746 | | | | 6.0 | |

Traditional Export Agriculture | | | 7,916 | | | | 1.0 | | | | 7,365 | | | | 1.0 | | | | 6,366 | | | | 0.8 | | | | 7,078 | | | | 1.0 | | | | 7,627 | | | | 1.0 | |

Other Agricultural Crops and Post-Harvest Crop Activities | | | 26,225 | | | | 3.5 | | | | 23,836 | | | | 3.1 | | | | 22,464 | | | | 3.0 | | | | 27,033 | | | | 3.7 | | | | 26,825 | | | | 3.7 | |

Animal Farming, Forestry and Fishing | | | 10,361 | | | | 1.4 | | | | 9,694 | | | | 1.3 | | | | 9,538 | | | | 1.3 | | | | 9,819 | | | | 1.3 | | | | 9,293 | | | | 1.3 | |

Construction | | | 61,078 | | | | 8.1 | | | | 63,829 | | | | 8.3 | | | | 58,992 | | | | 7.8 | | | | 55,873 | | | | 7.6 | | | | 55,314 | | | | 7.6 | |

Manufacture | | | 67,026 | | | | 8.9 | | | | 67,821 | | | | 8.8 | | | | 67,454 | | | | 8.9 | | | | 64,241 | | | | 8.7 | | | | 62,347 | | | | 8.6 | |

Mining and Quarrying: | | | 33,317 | | | | 4.4 | | | | 32,353 | | | | 4.2 | | | | 31,493 | | | | 4.1 | | | | 15,627 | | | | 2.1 | | | | 14,958 | | | | 2.1 | |

Bauxite and Alumina | | | 32,083 | | | | 4.2 | | | | 30,957 | | | | 4.0 | | | | 30,286 | | | | 4.0 | | | | 14,485 | | | | 2.0 | | | | 13,655 | | | | 1.9 | |

Quarrying incl. Gypsum | | | 1,234 | | | | 0.2 | | | | 1,396 | | | | 0.2 | | | | 1,207 | | | | 0.2 | | | | 1,142 | | | | 0.2 | | | | 1,303 | | | | 0.2 | |

| | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | |

Total Goods | | | 205,924 | | | | 27.2 | | | | 204,898 | | | | 26.7 | | | | 196,308 | | | | 25.8 | | | | 179,671 | | | | 24.4 | | | | 176,365 | | | | 24.3 | |

| | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | |

| | | | | | | | | | |

Wholesale & Retail Trade; Repairs and Installation of Machinery | | | 140,221 | | | | 18.5 | | | | 142,126 | | | | 18.5 | | | | 141,592 | | | | 18.6 | | | | 138,017 | | | | 18.7 | | | | 133,368 | | | | 18.3 | |

Electricity and Water Supply | | | 24,359 | | | | 3.2 | | | | 24,494 | | | | 3.2 | | | | 24,715 | | | | 3.2 | | | | 25,247 | | | | 3.4 | | | | 24,159 | | | | 3.3 | |

Financial & Insurance Services | | | 75,534 | | | | 10.0 | | | | 79,243 | | | | 10.3 | | | | 81,044 | | | | 10.7 | | | | 82,373 | | | | 11.2 | | | | 78,400 | | | | 10.8 | |

Producers of Government Services | | | 94,870 | | | | 12.5 | | | | 96,150 | | | | 12.5 | | | | 96,288 | | | | 12.7 | | | | 95,822 | | | | 13.0 | | | | 95,940 | | | | 13.2 | |

Hotels & Restaurants | | | 35,911 | | | | 4.7 | | | | 36,066 | | | | 4.7 | | | | 36,842 | | | | 4.8 | | | | 37,578 | | | | 5.1 | | | | 38,841 | | | | 5.3 | |

Real Estate, Renting & Business Activities | | | 77,237 | | | | 10.2 | | | | 79,827 | | | | 10.4 | | | | 80,980 | | | | 10.6 | | | | 79,968 | | | | 10.8 | | | | 78,998 | | | | 10.9 | |

Transport, Storage & Communication | | | 88,236 | | | | 11.7 | | | | 90,075 | | | | 11.7 | | | | 87,321 | | | | 11.5 | | | | 84,244 | | | | 11.4 | | | | 82,569 | | | | 11.4 | |

Other Services | | | 49,020 | | | | 6.5 | | | | 49,967 | | | | 6.5 | | | | 50,463 | | | | 6.6 | | | | 50,448 | | | | 6.8 | | | | 49,677 | | | | 6.8 | |

| | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | |

Total Services | | | 585,388 | | | | 77.4 | | | | 597,948 | | | | 78.0 | | | | 599,243 | | | | 78.8 | | | | 593,698 | | | | 80.5 | | | | 581,952 | | | | 80.1 | |

| | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | |

| | | | | | | | | | |

Less: Financial Intermediation Services Indirectly Measured (FISIM) | | | 35,179 | | | | 4.7 | | | | 35,874 | | | | 4.7 | | | | 34,655 | | | | 4.6 | | | | 35,927 | | | | 4.9 | | | | 31,476 | | | | 4.3 | |

| | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | |

| | | | | | | | | | |

Gross Domestic Product | | | 756,133 | | | | 100.0 | | | | 766,972 | | | | 100.0 | | | | 760,895 | | | | 100.0 | | | | 737,442 | | | | 100.0 | | | | 726,840 | | | | 100.0 | |

| | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | |

| (1) | The Jamaican System of National Accounts has undergone a comprehensive revision. The revision included: (1) the compilation of the national accounts in line with the United Nations System of National Accounts 1993 (1993 SNA); (2) incorporation of new and revised data into the estimates; (3) revision of the national accounts classification of industries; and (4) rebasing of the constant price estimates from 1996 to 2003. |

Source: Statistical Institute of Jamaica.

D-18

The following table shows the rate of growth of real GDP by economic sectors at constant 2007 prices for the five years ended December 31, 2010:

Rate of Growth of Real GDP by Sector(1)

| | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | |

| | | 2006 | | | 2007 | | | 2008 | | | 2009 | | | 2010 | |

| | | (%) | |

| | | | | |

Agriculture, Forestry and Fishing: | | | 20.0 | | | | (8.1 | ) | | | (6.2 | ) | | | 14.5 | | | | (0.4 | ) |

Traditional Export Agriculture | | | 72.5 | | | | (7.0 | ) | | | (13.6 | ) | | | 11.2 | | | | 7.8 | |

Other Agricultural Crops and Post-Harvest Crop Activities | | | 14.3 | | | | (9.1 | ) | | | (5.8 | ) | | | 20.3 | | | | (0.8 | ) |

Animal Farming, Forestry and Fishing | | | 8.3 | | | | (6.4 | ) | | | (1.6 | ) | | | 2.9 | | | | (5.4 | ) |

Construction | | | (3.7 | ) | | | 4.5 | | | | (7.6 | ) | | | (5.3 | ) | | | (1.0 | ) |

Manufacture | | | (1.9 | ) | | | 1.2 | | | | (0.5 | ) | | | (4.8 | ) | | | (2.9 | ) |

Mining and Quarrying: | | | 0.7 | | | | (2.9 | ) | | | (2.7 | ) | | | (50.4 | ) | | | (4.3 | ) |

Bauxite and Alumina | | | 1.3 | | | | (3.5 | ) | | | (2.2 | ) | | | (52.2 | ) | | | (5.7 | ) |

Quarrying incl. Gypsum | | | (13.1 | ) | | | 13.1 | | | | (13.5 | ) | | | (5.4 | ) | | | 14.1 | |

| | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | |

Total Goods | | | 2.0 | | | | (0.5 | ) | | | (4.2 | ) | | | (8.5 | ) | | | (1.8 | ) |

| | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | |

Wholesale & Retail Trade; Repairs and Installation of Machinery | | | 2.3 | | | | 1.4 | | | | (0.4 | ) | | | (2.5 | ) | | | (3.4 | ) |

Electricity and Water Supply | | | 3.2 | | | | 0.6 | | | | 0.9 | | | | 2.2 | | | | (4.3 | ) |

Financial & Insurance Services | | | 2.6 | | | | 4.9 | | | | 2.3 | | | | 1.6 | | | | (4.8 | ) |

Producers of Government Services | | | 0.4 | | | | 1.3 | | | | 0.1 | | | | (0.5 | ) | | | 0.1 | |

Hotels & Restaurants | | | 10.0 | | | | 0.4 | | | | 2.1 | | | | 2.0 | | | | 3.4 | |

Real Estate, Renting & Business Activities | | | 1.9 | | | | 3.4 | | | | 1.4 | | | | (1.2 | ) | | | (1.2 | ) |

Transport, Storage & Communication | | | 4.2 | | | | 2.1 | | | | (3.1 | ) | | | (3.5 | ) | | | (2.0 | ) |

Other Services | | | 5.3 | | | | 1.9 | | | | 1.0 | | | | 0.0 | | | | (1.5 | ) |

| | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | |

Total Services | | | 3.0 | | | | 2.1 | | | | 0.2 | | | | (0.9 | ) | | | (2.0 | ) |

| | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | |

Less: Financial Intermediation Services Indirectly Measured (FISIM) | | | (0.5 | ) | | | 2.0 | | | | (3.4 | ) | | | 3.7 | | | | (12.4 | ) |

| | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | |

Gross Domestic Product | | | 2.9 | | | | 1.4 | | | | (0.8 | ) | | | (3.1 | ) | | | (1.4 | ) |

| | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | |

| (1) | The Jamaican System of National Accounts has undergone a comprehensive revision. The revision included: (1) the compilation of the national accounts in line with the United Nations System of National Accounts 1993 (1993 SNA); (2) incorporation of new and revised data into the estimates; (3) revision of the national accounts classification of industries; and (4) rebasing of the constant price estimates from 1996 to 2003. |

Source: Statistical Institute of Jamaica.

The Petrocaribe Agreement

On August 23, 2005, Jamaica entered into the Petrocaribe Energy Cooperation Agreement (the Petrocaribe Agreement), with the government of the Bolivarian Republic of Venezuela, effective as of June 29, 2005, for an automatically renewable one-year term. The Petrocaribe Agreement has been renewed annually since 2005. Under the arrangement, Venezuela has agreed to make available to Jamaica a portion of the value of Jamaica’s purchases of oil as a concessionary loan facility, the terms of which are determined by the prevailing price per barrel of oil internationally. Currently, with the price of oil averaging more than $100 per barrel, the amount of concessionary financing available is sixty percent 60% of the value of purchases, which is to be repaid over 25 years, including a two-year grace period, at an interest rate of 1.0%. The terms of the Petrocaribe Agreement limit the concessionary flows to the purchase of a maximum of 23,500 barrels per day (23,500 Bbl/day) of crude oil, refined products and liquefied petroleum gas (LPG) or its energy equivalents, supplied directly to Jamaica for its internal consumption. Prices for products are based on prevailing rates in the international oil market and deliveries to Jamaica are subject

D-19

to the commercial policies and practices of Petroleos de Venezuela S.A., or PDVSA. Jamaica has the option of providing alternative forms of payments through goods and services. The Petrocaribe Agreement may be modified or terminated by Venezuela upon 30 days’ written notice to Jamaica.

In 2006, Parliament authorized the establishment of the Petrocaribe Development Fund to undertake the following activities in relation to the Petrocaribe Agreement:

| | • | | manage loan proceeds that flow to Jamaica; |

| | • | | provide financing for approved projects and receive loan repayments from borrowers; and |

| | • | | meet debt service obligations to Venezuela arising from the Agreement. |

At March 31, 2011, the loan proceeds to the Petrocaribe Development Fund totaled US$1,431 million.

Revitalization of downtown Kingston

The Urban Development Corporation of Jamaica, or UDC, is in the process of preparing a redevelopment plan for downtown Kingston. This envisages various projects being implemented on a phased basis in keeping with Vision 2030 Jamaica, which seeks to position Jamaica as a place of choice to live, work, raise families and do business. As part of this plan, the UDC has been actively engaging public and private sector entities to invest in downtown Kingston.

Arising out of these efforts, telecommunications company Digicel has started the construction of its group headquarters in Kingston. Digicel is incorporated in Bermuda but has its head offices in Jamaica. Digicel’s decision to relocate from offices in New Kingston to downtown Kingston is expected to have significant direct and indirect effects on the downtown Kingston redevelopment effort. One of the direct consequences will be the addition of approximately 1,000 working professionals and expatriates to the downtown Kingston area each day. This will result in an increased demand for support services such as banking, restaurants and other retail services. Even prior to the completion of the building of its headquarters, Digicel has already invested over J$170 million to renovate the Coronation Market (the largest of its kind in Jamaica) and has committed to spending even more in the downtown Kingston market district.

Principal Sectors of the Economy

Tourism

The tourism industry is the leading gross earner of foreign exchange for Jamaica and makes a significant contribution to employment. Tourism accounted for 39.1% of gross foreign exchange earnings from the productive sector in 2010. In 2010, the accommodation sub-sector alone employed approximately 37,018 persons. Visitor arrivals in Jamaica have increased in the last decade, from 2,231,765 million visitors in 2000 to 2,831,297 million visitors in 2010. Total visitors’ accommodation has also grown during the last decade to 28,374 rooms in 2009 from 26,360 rooms in 2000.

During 2010, visitor arrivals increased 2.8% to 2,831,297 in 2010, from 2,753,446 in 2009. Visitor arrivals increased mainly due to increases in the frequency of flights and number of routes provided by airlines during the year, Governmental support of increased marketing, the private tourism industry offering attractive rates, continued advertising and an increase in hotel occupancy in an environment with increased hotel capacity. In 2010, stopover arrivals to Jamaica increased by 4.9% to 1,921,678 from 1,831,097 in 2009. This increase was partially offset by a 1.4% decline in the number of cruise passengers to 909,619 from 922,349 in 2009. The main factors that can be identified as having had a positive impact on Jamaica’s stopover arrivals during 2010 were the aggressive thrust to maintain the current airlift capacity and initiate new gateways to the island, Governmental support of increased marketing, as well as the private industry offering attractive pricing for air travel, hotels and vacation packages.

D-20

During 2009, visitor arrivals decreased 3.7% to 2,753,446 in 2009, from 2,859,534 in 2008. This follows a decline of 0.7% to 2,859,534 in 2008 compared to the 2,880,289 in 2007. The decline in 2009 in visitor arrivals was primarily a result of a 15.6% decrease in cruise passengers, which was offset in part by an increase in stopover visitors. The number of cruise passengers declined due to the global economic slowdown. Stopover arrivals to Jamaica increased by 3.6% to 1,831,097 in 2009 from 1,767,271 in 2008.

During 2008, visitor arrivals decreased 0.7%, from 2,880,289 in 2007 to 2,859,534 in 2008. This follows a decline of 4.5% to 2,880,829 in 2007 compared to an all-time high of 3,015,899 in 2006. The decline in 2008 in visitor arrivals was primarily a result of a decrease in cruise passengers, which was offset in part by an increase in stopover visitors. The number of cruise passengers declined due to the global economic slowdown. Stopover arrivals to Jamaica increased by 3.9% from 1,700,785 in 2007 to 1,767,271 in 2008. The increases in stopover arrivals in each of 2009 and 2008 were a result of a combination of factors, including Government support of increased marketing and the private tourism industry offering attractive rates.

For the first ten months of 2011, total visitor arrivals were 2,462,555, an increase of 6.5% compared to the same period of 2010; stopover arrivals totaled 1,614,318, a 1.8% increase over the same period in 2010; and cruise passengers totaled 848,237, an increase of 16.9% compared to the same period of 2010. The number of cruise passengers increased mainly due to the opening of the new cruise ship pier in Falmouth Trelawny. The increases in stopover arrivals in the ten months of the year reflect the results of the continuing wide-ranging marketing and sales activities Jamaica has embarked upon to encourage travel from Jamaica’s major tourist markets—the United States and Canada—as well as attractive pricing offered by the private tourism industry. In addition, Jamaica continued to secure adequate airlift out of major airport hubs allowing more visitors easy access to the destination. Currently 31 airlines fly into Jamaica including Air Canada, American Airlines, British Airways, Continental Airlines, Delta Airlines, Jet Blue and Virgin Atlantic Airlines.

The United States, Jamaica’s major tourist market, accounted for 64.7% of total stopover visitors in 2010, compared to 64.1% in 2009. Jamaica’s share of visitors from Canada has grown to 16.9% a share in 2010 from 15.9% in 2009. Jamaica’s share of visitors from Europe decreased to 14.1% in 2010 from 15.1% in 2009. Average hotel room occupancy was 60.5% in 2010, 59.0% in 2009, 60.4% in 2008, 63.2% in 2007 and 62.8% in 2006. Approximately 54.7% of hotel rooms in Jamaica are in the all-inclusive hotel category. In 2010, the average room occupancy rate of all-inclusive hotels was 67.4%. Three hotel chains—Sandals Resorts International Limited, SuperClubs and RIU Resorts—operate the majority of the all-inclusive rooms.