Exhibit (c)(ii)

American Bancorp, Inc.

Opelousas, LA

Fairness Opinion

February 11, 2004

P.O. Box 14720

Baton Rouge, Louisiana 70898

(225) 757-1200

fax (225) 765-7200

Table of Contents

| 1 | | | | Introduction | | 1 |

| | | 1.1 | | | | Description of the Engagement | | 1 |

| | | 1.2 | | | | Standard of Value | | 1 |

| | | 1.3 | | | | Summary of the Company | | 1 |

| | | 1.4 | | | | Sources of Information | | 1 |

| | | 1.5 | | | | Assumptions and Limiting Conditions | | 2 |

| 2 | | | | Economic Conditions and Industry Data | | 2 |

| | | 2.1 | | | | National Economic Profile | | 2 |

| | | 2.2 | | | | Regional and Local Economic and Demographic Profile | | 3 |

| | | 2.3 | | | | Industry Conditions | | 3 |

| 3 | | | | Analysis of the Subject Company | | 4 |

| | | 3.1 | | | | General Description | | 4 |

| | | 3.2 | | | | Management | | 4 |

| | | 3.3 | | | | Competition | | 4 |

| | | 3.4 | | | | Facilities | | 5 |

| 4 | | | | Financial Statement Analysis | | 5 |

| | | 4.1 | | | | Historical Financial Statements | | 5 |

| | | 4.2 | | | | Comparative Statistics | | 5 |

| | | | | 4.2.1 | | Uniform Bank Performance Report | | 5 |

| | | 4.3 | | | | Normalizing Adjustments | | 6 |

| | | | | 4.3.1 | | Holding Company Adjustments | | 6 |

| | | | | 4.3.2 | | Income Tax Adjustment | | 6 |

| 5 | | | | Valuation of the Subject Company | | 7 |

| | | 5.1 | | | | Factors to be Considered | | 7 |

| | | 5.2 | | | | Valuation Approaches | | 7 |

| | | 5.3 | | | | Asset Based Approaches | | 8 |

| | | 5.4 | | | | Market Based Approach—Comparable Transactions | | 8 |

| | | | | 5.4.1 | | Comparable Sales—Whole Bank Transactions | | 8 |

| | | | | 5.4.2 | | Publicly Traded Comparable Companies | | 9 |

| | | | | 5.4.3 | | Publicly Traded Comparable Companies—Share Exchange | | 9 |

| | | | | 5.4.4 | | Historical Transactions in Company Stock | | 10 |

| | | 5.5 | | | | Income Based Approaches | | 10 |

| | | | | 5.5.1 | | Discounted Future Returns | | 10 |

| | | | | 5.5.2 | | Capitalization of Historical Earnings | | 11 |

| 6 | | | | Valuation Adjustments | | 11 |

| | | 6.1 | | | | Common Adjustments | | 11 |

| | | 6.2 | | | | Control Premium/Minority Discount | | 12 |

| | | | | 6.2.1 | | The Minority Stockholder's Situation | | 12 |

| | | | | 6.2.2 | | Control Premium | | 13 |

| | | 6.3 | | | | Marketability Adjustment | | 14 |

| | | 6.4 | | | | Application of Adjustments | | 14 |

| 7 | | | | Valuation Conclusion | | 15 |

| 8 | | | | Valuator's Certification | | 15 |

| 9 | | | | Valuator's Qualifications | | 16 |

i

1 Introduction

1.1 Description of the Engagement

National Capital, L.L.C. ("National Capital") has been engaged to provide a Fairness Opinion to American Bancorp, Inc. (the "Company") in connection with the Company's proposed merger with American Interim Company, a wholly-owned subsidiary of the Company. The transaction is intended to reduce the number of shareholders of common stock of the Company to fewer than 75, thereby allowing the Company to elect to be taxed as a Subchapter S corporation for federal income tax purposes and to terminate the registration of its common stock under the Securities Exchange Act of 1934. Under this plan, certain shareholders of the Company will receive cash for their shares in an involuntary exchange. Our Fairness Opinion addresses the fairness of the cash consideration to be paid to these shareholders, from the perspective of all shareholders of the Company.

1.2 Standard of Value

Revenue Ruling 59-60 defines fair market value as:

…the price at which the property would change hands between a willing buyer and a willing seller when the former is not under any compulsion to buy and the latter is not under any compulsion to sell, both parties having reasonable knowledge of relevant facts. Court decisions frequently state in addition that the hypothetical buyer and seller are assumed to be able, as well as willing, to trade and to be well informed about the property and concerning the market for such property.

For the purpose of this engagement, Fair Market Value is not appropriate due to the involuntary surrender of certain shareholders' interests in exchange for cash that will occur as part of the reverse stock split. Fair Market Value is, however, an appropriate starting point from which to define a standard of value that acknowledges the premium due to an involuntary participant in a transaction. The concept of Fair Value, while not well defined in Louisiana case law, can be described as Fair Market Value without the phrase "not under any compulsion to sell". As the seller is being forced to transact, some incremental value is generally recognized to be appropriate as compensation for the involuntary nature of the transaction. This incremental value is often recognized in the valuation process through the exclusion of all or part of the minority discount usually applied to minority shareholder interests under the Fair Market Value standard.

Fair Value will be used as the standard of value when considering the fairness of the proposed transaction.

1.3 Summary of the Company

The Company is the holding company for American Bank & Trust Company (the "Bank"), a community bank servicing the banking needs of consumers and businesses in the Opelousas, Louisiana area. Detailed corporate information can be found in Section 3: Analysis of the Subject Company.

1.4 Sources of Information

In preparing this valuation report, we obtained various financial documents and other information pertaining to the Company and Bank from its management. We have considered, among other items, the following:

- 1.

- The Bank's Call Reports for the years ended December 31, 1997 through 2003;

- 2.

- The Bank's Uniform Bank Performance Report ("UBPR") dated September 30, 2003;

- 3.

- The Company's Annual Report to Shareholders for the years ended December 31, 2001 and 2002, including the Company's audited financial statements;

1

- 4.

- The Company's SEC form 10-K for the year ended December 31, 2002; and

- 5.

- The Company's Business Plan and current financial projections.

In addition to the information provided by the Company, we reviewed and analyzed a number of public documents and databases, including the following:

- 1.

- Federal Reserve Board Beige Book dated January 14, 2004; (www.federalreserve.gov/fomc/BeigeBook);

- 2.

- Stocks, Bonds, Bills and Inflation: Valuation Edition 2002 Yearbook; Ibbotson Associates, 2003; and

- 3.

- Numerous internet resources, including the sites maintained by the following:

Federal Reserve Bank of Atlanta (www.frbatlanta.org), Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation (www.fdic.gov), and SNL Financial (www.snl.com andwww.ymerge.com).

1.5 Assumptions and Limiting Conditions

This valuation report is subject to the following assumptions and limiting conditions:

- 1.

- All financial information was supplied by the Company or its agents. This information has been accepted by National Capital as having been prepared in accordance with generally accepted accounting principles and has not been subject to further verification, except as otherwise described in this report.

- 2.

- National Capital has relied on the accuracy and completeness of all information provided by the Company and its agents. Any material misstatements or omissions could significantly alter our conclusion of value.

- 3.

- Except as noted herein, no attempts were made to verify the validity of the information provided by or obtained from any external source. All thirdparty sources are considered reputable providers of accurate data.

- 4.

- No verification of legal title has been conducted in relation to the real and personal property of the Company. All rights and claims to these assets are assumed to be valid and no consideration has been given to any liens or encumbrances other than those specifically identified in this report.

- 5.

- All liabilities of the Company are assumed valid and legally enforceable. No consideration has been given to contingent liabilities except as specifically identified in this report.

- 6.

- This report and conclusion of value are for the specific use identified in Section 1.1, and may not be quoted in whole or in part or otherwise referred to in any document, or furnished or otherwise communicated to any person for any other purpose without our prior written consent.

- 7.

- This fairness opinion and report are limited only by the above factors and reflect the unbiased, professional opinion of National Capital.

2 Economic Conditions and Industry Data

2.1 National Economic Profile

The Federal Reserve Board Beige Book discussing the current U.S. economic outlook is included as Exhibit A.

2

2.2 Regional and Local Economic and Demographic Profile

Additional information on the regional and local economy is included as Exhibit B.

2.3 Industry Conditions

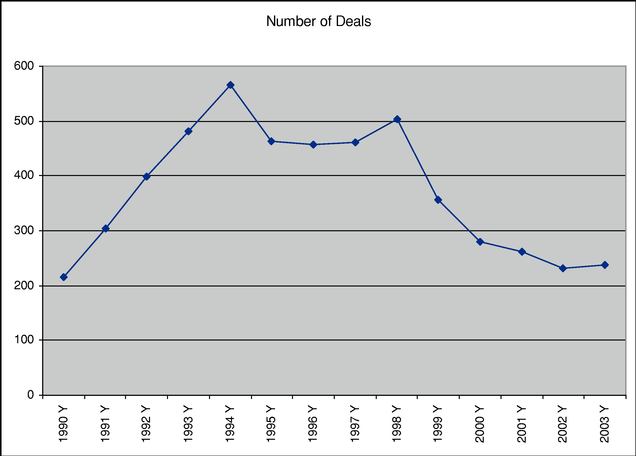

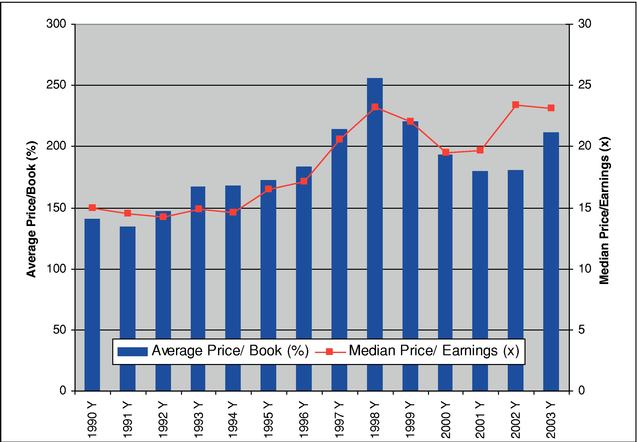

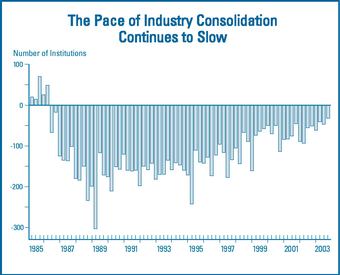

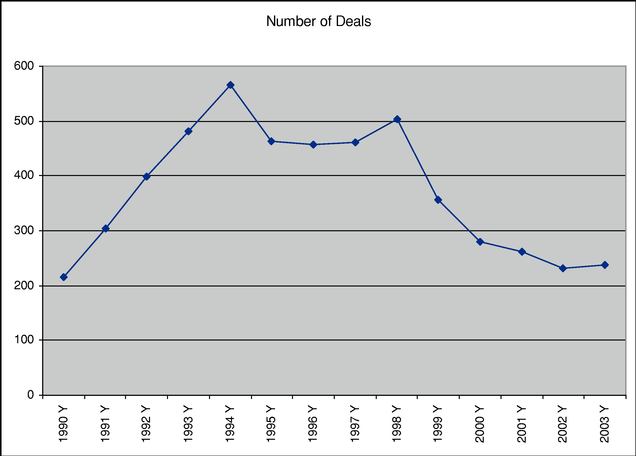

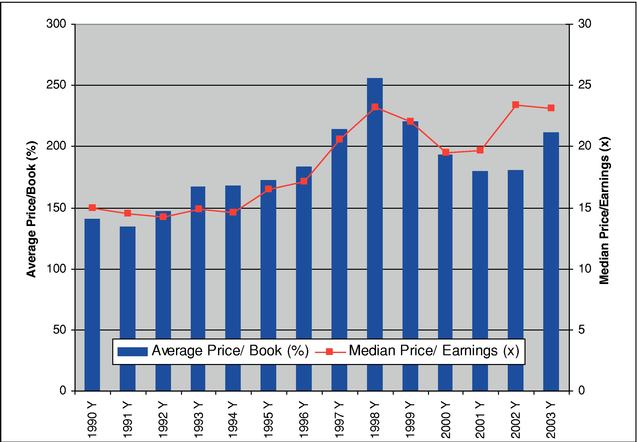

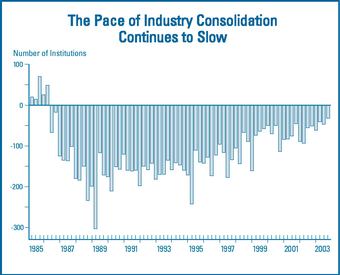

Sales of banks and bank holding companies have slowed in recent years, dropping to levels not seen since the early 1990s. Much of this decrease is attributable to the lack of attractive acquisition candidates and the shift in focus of many mid-size acquirors toward selling or merging with other institutions.

Over the last fourteen years, bank pricing has seen several peaks and valleys, as shown in the following graph. In 2003, we saw a return to relatively high pricing multiples, along with an increase in earning multiples as compared to book multiples.

3

Please refer to Exhibit C for additional information on industry conditions.

3 Analysis of the Subject Company

3.1 General Description

American Bank & Trust Company is a full service provider of financial services for consumers and businesses with five offices in St. Landry Parish and one location in Lafayette Parish. The Bank, founded in 1958, currently has over $100 million in total assets.

The Company had 10,000,000 shares of common stock authorized as of the valuation date, with 120,000 shares issued and 115,987 shares outstanding. There are a total of 503 shareholders.

3.2 Management

Mr. Salvador L. Diesi, Sr., age 73, is the President, and has been with the Bank for 20 years. Mr. Ronald J. Lashute, age 53, serves as the Bank's Executive Vice President and Chief Executive Officer. Mr. Lashute has worked for the Bank for 31 years. Executive Management is considered sufficient for the current and future needs of the Bank.

3.3 Competition

Competition within the industry comes from many different sources: national and state chartered banks, credit unions, savings banks, investment companies and non-traditional lenders. Over the past twenty years, the share of the average consumer's wealth held in commercial banks has steadily declined.

4

Statistical information on the Bank's market and competitors is included as Exhibit D.

3.4 Facilities

The Bank operates from a main office located at Union and Landry Streets, Opelousas, Louisiana. It has one other full-service office in Opelousas, and offices in Krotz Springs, Port Barre and Lawtell in St. Landry Parish, as well as the Lafayette office. There is also an operations center located next to the main office. All facilities are considered adequate for current and future operations of the Bank.

4 Financial Statement Analysis

4.1 Historical Financial Statements

The table below summarizes pertinent financial information of the Bank.

American Bank & Trust Company

Financial Summary

| | 2003

| | 2002

| | 2001

| | 1999

| | CAGR

| |

|---|

| Total Loans | | 39,972 | | 40,558 | | 38,241 | | 32,660 | | 5.18 | % |

| Total Assets | | 100,781 | | 99,653 | | 92,041 | | 82,749 | | 5.05 | % |

| Total Deposits | | 85,638 | | 84,842 | | 78,711 | | 71,345 | | 4.67 | % |

| Loan Loss Reserve | | 667 | | 627 | | 605 | | 580 | | 3.56 | % |

Loans to Deposits |

|

46.68 |

% |

47.80 |

% |

48.58 |

% |

45.78 |

% |

|

|

| Reserve to Loans | | 1.67 | % | 1.55 | % | 1.58 | % | 1.78 | % | | |

| Return on Assets | | 1.00 | % | 1.29 | % | 1.25 | % | 1.47 | % | | |

Total Capital |

|

14,055 |

|

13,577 |

|

12,236 |

|

11,044 |

|

6.21 |

% |

Net Income |

|

1,006 |

|

1,290 |

|

1,149 |

|

1,217 |

|

- -4.65 |

% |

The Company's historical balance sheets and income statements for the years ended December 31, 1999 through 2003 are included as Exhibit E.

4.2 Comparative Statistics

4.2.1 Uniform Bank Performance Report

The Uniform Bank Performance Report (UBPR) is an analytical tool created for bank supervisory, examination, and management purposes. In a concise format, it shows the impact of management decisions and economic conditions on a company's performance and balance sheet composition. The performance and composition data contained in the report can be used as an aid in evaluating the adequacy of earnings, liquidity, capital, asset and liability management, and growth management. Bankers and examiners alike can use this report to further their understanding of a company's financial condition, and through such understanding, perform their duties more effectively.1 Some of the key ratios are presented below.

5

- 1

- Federal Financial Institutions Examination Council website (http://www.ffiec.gov/UBPR.htm)

UBPR

| | 9/30/2003

|

|---|

| | AMBO

| | Peer

| | Percentile

|

|---|

| Capital Adequacy | | | | | | |

| | Tier One Risk-Based Capital/Risk-Weighted Assets | | 28.90 | | 13.34 | | 96 |

| | Total Risk-Based Capital/Risk-Weighted Assets | | 30.16 | | 14.50 | | 96 |

| | Tier One Leverage Capital | | 14.09 | | 8.98 | | 94 |

Asset Quality |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| | Past Due Loans/Total Loans: | | 0.99 | | 0.97 | | 58 |

| | | Nonaccrual/Total Loans | | 0.01 | | 0.66 | | 19 |

| | | 90+ Days Past Due/Total Loans | | 0.99 | | 0.21 | | 89 |

| | | 30-89 Days Past Due/Total Loans | | 1.18 | | 1.12 | | 59 |

| | Net Loan Losses/Average Total Loans & Leases | | 0.00 | | 0.19 | | 22 |

Management |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| | Average Earning Assets/Average Assets | | 92.62 | | 91.43 | | 61 |

| | Personnel Expense/Average Assets | | 1.63 | | 2.00 | | 20 |

| | Total Overhead Expense/Average Assets | | 3.34 | | 3.75 | | 35 |

| | Asset Growth Rate | | 5.60 | | 9.17 | | 48 |

Earnings |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| | Return on Assets (Net Income/Average Assets) | | 1.11 | | 0.87 | | 67 |

Liquidity |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| | Net Short Term Non-Core Funding Dependence | | (0.14 | ) | 1.02 | | 38 |

| | Net Noncore Funding Dependence | | 0.13 | | 7.84 | | 25 |

| | Net Loans/Total Deposits | | 47.73 | | 75.36 | | 6 |

| | Net Loans/Core Deposits | | 53.47 | | 88.01 | | 6 |

| | Net Loans/Assets | | 40.22 | | 64.49 | | 6 |

| | Core Deposits/Assets | | 75.87 | | 73.94 | | 56 |

4.3 Normalizing Adjustments

Given the highly regulated nature of the banking industry, there are few normalizing adjustments to be considered when valuing a financial institution. For purposes of this valuation, the following normalizing adjustments were made.

4.3.1 Holding Company Adjustments

For the purposes of this valuation, we considered the financial information of the Bank, as there are no operations and limited expenses at the holding company level. We reduced the Bank's pretax income by $13,000 to consider ongoing holding company expenses, resulting in pretax income of $1,246,000. We also considered the holding company's equity of $14,069,647 and cash dividend of $231,974 for valuation purposes.

4.3.2 Income Tax Adjustment

The Bank's income tax liability in 2003 was reduced by $79,703 due to overpayments in previous years. We increased income tax by this amount, thereby reducing the Company's net income. Total net income for valuation purposes, after these adjustments, was $913,297.

6

5 Valuation of the Subject Company

5.1 Factors to be Considered

Discussing the valuation process, Revenue Ruling 59-60 states:

In valuing the stock of closely held corporations or the stock of corporations where market quotations are not available, all other available financial data, as well as all relevant factors affecting the fair market value must be considered for estate tax and gift tax purposes. No general formula may be given that is applicable to the many different valuation situations arising in the valuation of such stock.

Revenue Ruling 59-60 also outlines the following factors that "require careful analysis" in business valuations:

- 1.

- The nature of the business and the history of the enterprise from its inception.

- 2.

- The economic outlook in general and the condition and outlook of the specific industry in particular.

- 3.

- The book value of the stock and the financial condition of the business.

- 4.

- The earning capacity of the company.

- 5.

- The dividend-paying capacity of the company.

- 6.

- Whether or not the enterprise had goodwill or other intangible value.

- 7.

- Sales of the stock and the size of the block of stock to be valued.

- 8.

- The market price of stocks of corporations engaged in the same or a similar line of business having their stocks actively traded in a free and open market, either on an exchange or over-the-counter.

Each of these factors is addressed in this valuation report.

5.2 Valuation Approaches

There are three main categories of valuation methods: Asset Based Approaches, Market Based Approaches and Income Based Approaches. Each method examines the value of a subject entity from a slightly different perspective, and each method has its own strengths and weaknesses in general and in specific application. In most cases, the values determined by each method will differ as a result of the varying inputs and assumptions required under each approach. It is up to the analyst to determine which method provides the most accurate value of the subject.

Methods within the Asset Based Approaches presume that the value of the subject entity is represented by the market values of the assets owned by the entity, less the market value of any liabilities. Thenet asset value method assumes that the values of all assets are realized through the course of normal business operations, while theliquidation method assumes that all assets are liquidated in an orderly fashion.

Thecomparative transaction method represents the common application of the Market Based Approach. By using one or more sets of statistics drawn from comparable completed whole-entity sales (public company mergers and acquisitions, private transactions) and/or partial interest transactions (publicly-traded stocks, mutual funds, partnership interests, REITs, etc.), the value of the subject can be estimated using multiples of the subject's revenues, earnings, dividends, cash flow, capital or other relevant financial attributes. In addition, historical information on actual transactions in the subject's stock can provide highly valuable information as to the true value of the subject, provided that the transactions were conducted at arm's length and occurred in the relatively recent past.

7

Within the Income Based Approaches, methods are differentiated based on the use of historical or projected income streams. Under thecapitalized returns method, an estimation of value is based on historical data. This method is most suitable for use when the subject's recent historical normalized returns can be reasonably expected to continue into the future and can be expected to grow at a predictable rate. By contrast, thediscounted future returns method is based on the present value of expected future earnings. This method is more applicable if the subject's earnings fluctuate greatly, if the subject has no history of earnings, or if the subject has recently undergone major changes in operating characteristics. Both of these methods require a reasonable and supportable estimation of future earnings prospects.

5.3 Asset Based Approaches

The Company's tangible equity totaled $14.1 million as of December 31, 2003. Assuming that all of the Company's assets and liabilities are carried at or near their reasonable market values, this amount should be the minimum at which the whole Company should be sold. At any lower value, the current owners could liquidate the Company and walk away with over $14 million, less the cost of liquidation.

In reality, FDIC-insured financial institutions are rarely liquidated except in cases of near failure. These failure situations are usually a result of long-term mismanagement, highrisk lending practices and/or illegal activity (fraud, embezzlement, etc.). Further, this liquidation method is not an appropriate method to consider in the valuation of an ongoing entity.

5.4 Market Based Approach—Comparable Transactions

The comparable transactions method is based on the financial theory of substitution or economic indifference. By obtaining data related to actual sales transactions of similar entities or interests and making appropriate adjustments to recognize the differences between the subject and its comparables, an estimate of the market value of the subject can be obtained.

The selection of financial attributes to be valued and the selection of appropriate comparables are critical in developing a market-based valuation estimate. While this method can be extremely useful due to its use of actual transaction data as a source of value determination, it is often difficult (or even impossible) to find truly comparable companies that have sold or that are traded in a public market. It should be noted that comparables do not have to be identical to the subject company, but should be similar enough to withstand scrutiny. Courts have criticized valuators for excluding reasonably comparable entities from consideration and have also objected to the use of transaction data that was drawn from too wide a set of comparables, which were, in fact, incomparable.

The following methods were used to develop comparable-based valuations:

5.4.1 Comparable Sales—Whole Bank Transactions

The SNL DataSource database provides detailed information on whole bank transactions and allows for searches based on multiple criteria. The criteria used in this valuation were:

| | From

| | To

| |

|---|

| Seller Total Assets | | $ | 50MM | | $ | 250MM | |

Return On Assets |

|

|

0.50 |

% |

|

1.50 |

% |

Tangible Equity/Assets |

|

|

9.0 |

% |

|

20.0 |

% |

Transaction Announced |

|

|

2/10/2003 |

|

|

2/9/2004 |

|

8

Terminated transactions and transactions where material data was unavailable were excluded from the analysis. A complete listing of the transaction dataset is included in Exhibit F.

| Number of Transactions | | 24 |

| | Multiple

| |

|---|

| Price/Earnings | | 21.73 | |

| Price/Tangible Book* | | 169.60 | % |

| Price/Assets | | 20.20 | % |

| Price/Deposits | | 23.16 | % |

| Premium/Core Deposits | | 13.99 | % |

*—We adjusted the Company's tangible equity to the level of that of the peer group, multiplied the price/tangible book multiple to this adjusted level, and added the excess equity dollar for dollar.

By applying the median of key valuation factors to the relevant factors from the Company's financials, we determined an entity value, before appropriate adjustments, of $21,679,854. Exhibit F includes details of this valuation process.

5.4.2 Publicly Traded Comparable Companies

Exhibit G shows a comparison of certain financial data of 13 publicly traded bank holding companies located in Louisiana or Mississippi. These publicly traded companies were selected based on their asset size and location. We have carefully considered each guideline company and its similarity or difference to the Company in terms of business, size, and financial and operating characteristics. All of these companies have a market presence in one or more metropolitan area in the two states, and some of them may be direct competitors of the Company. When viewed together, they serve as a guideline for expected returns, capital market pricing and financial data of related segments of the banking industry. We have, therefore, determined that the guideline companies are sufficiently similar to the Company to permit their utilization in a valuation pricing model. The median pricing multiples of the group are shown below.

| | Multiple

| |

|---|

| Price/Earnings | | 15.65 | |

| Price/Tangible Book* | | 181.69 | % |

| Price/Assets | | 19.30 | % |

| Price/Deposits | | 25.54 | % |

| Dividend Yield | | 2.58 | % |

*—We adjusted the Company's tangible equity to the level of that of the peer group, multiplied the price/tangible book multiple to this adjusted level, and added the excess equity dollar for dollar.

By applying the median of key valuation factors to the relevant factors from the Company's financials, we determined an entity value, before appropriate adjustments, of $19,094,478.

5.4.3 Publicly Traded Comparable Companies—Share Exchange

The Publicly Traded Comparable Companies—Share Exchange Method is founded on the premise that a rational, publicly-traded potential buyer of a bank or bank holding company would be willing to execute a share exchange only if such an exchange would be non-dilutive (or minimally dilutive) to the acquirer's pro forma per share earnings.

9

We analyzed the earnings performance of the Company in light of the earnings performance and market values of the peer group of publicly traded bank holding companies discussed above. Based on size, financial strength, operating history and geographic proximity, it is reasonable to assume that each institution would be able to consummate a transaction with the Company.

Before analyzing the earnings performance of the Company in light of the share exchange analysis, we made an earnings adjustment of 25% to take into account an estimate of cost savings and other synergies that would be expected to result from the acquisition. After adjustment, we determined that the pro forma earnings estimate of the Company for the year ended December 31, 2004, would be approximately $1,500,000. To determine the implied share exchange market value of the Company, we calculated the average of the projected values that the regional peer group acquirors would pay for the Company in a non-dilutive transaction. To determine the individual projected values, we divided the Company's adjusted pro forma earnings by each acquiring company's estimated earnings per share for 2004 to determine the number of shares to be issued to the Company, and multiplied the number of shares to be issued by the acquiring company's price-earnings ratio. Using the share exchange analysis, we determined an implied share exchange market value of $22,125,704, prior to the application of appropriate valuation adjustments. Exhibit H illustrates the application of the share exchange analysis.

5.4.4 Historical Transactions in Company Stock

There have been several transactions involving Company stock in the last 18 months. The Company repurchases shares routinely, with the price set by the Board at 75% of book value. There were eight such transactions between June 2002 and December 2003, totaling 301 shares at prices between $79 and $89 per share. None of these transactions are considered "arm's length."

Additionally, some shares recently have been traded through market makers, who then publish the price on the OTC Bulletin Board. Information regarding these trades is not readily available to the Company; however, information on the OTC website and Yahoo Finance indicate that 1,600 shares were traded since June 1, 2002, at prices ranging from $90 to $150 per share. There have been no transactions since October 2003.

5.5 Income Based Approaches

5.5.1 Discounted Future Returns

As discussed in Section 5.2: Valuation Approaches, this method has as its basic premise the theory that a business is worth the present value of all the expected future benefits of ownership. Proper application of this theory requires the analyst to select the appropriate measure of return to the owner (cash flow vs. net earnings) and select the appropriate discount rate and/or capitalization rate to be applied to the selected measure of returns. The method also requires the analyst to make certain assumptions regarding prospective earnings and anticipated earnings growth rates.

The two primary components of the value estimate developed using the discounted future returns method are:

- •

- The present value of operations from the valuation date until a stable and sustainable level of growth and profit is established, and

- •

- The present value of the company's value in theterminal year, defined as the year after stable and sustainable growth and profit are established.

After projecting the future values of the Company, it is necessary to determine the present value of those future returns using a discount rate. The Ibbotson Buildup Method was used to determine this discount rate. Exhibit I includes a detailed description of the components of this rate.

10

Balance sheet and income statement projections were prepared by National Capital and reviewed by Company management. Dividends and cash flows from the sale of the Company at the terminal period were used as the appropriate measure of return. Future period dividends were projected at 70% of earnings. The selected payout ratio is based on the Company's earnings and growth projections and its ability to distribute this level of earnings without impairing capital adequacy. Based on this information, the value of the Company using the Discounted Future Returns Value, prior to the application of appropriate valuation adjustments, is $19,098,861. Exhibit I provides detailed calculations of this result.

5.5.2 Capitalization of Historical Earnings

Following much of the same logic as the Discounted Future Returns Method, the Capitalization of Historical Earnings relies on historical data rather than estimates of future performance as the basis for valuation. In many cases, courts have indicated a preference for the use of historical financial information due to the actual, verifiable nature of the data. While it has often been said that past performance is not always an indication of future results, the Historical Earnings Method can provide a reasonable indication of value, especially in cases where the subject company has a history of stable earnings or growth and such stability or growth can be reasonably expected to continue in a similar manner.

The Company has experienced a declining return on average assets over the last five years. As indicated in Exhibit J, a weighted trend line of earnings from 1999 through 2003 was used to establish the earnings level to be capitalized. The median Price/Earnings multiple of comparable public companies was used to calculate the appropriate capitalization rate.

After consideration of all appropriate factors, the value of the Company using the Capitalization of Historical Earnings method, prior to the application of appropriate valuation adjustments, is $19,325,602.

6 Valuation Adjustments

6.1 Common Adjustments

The purpose of a valuation adjustment is to reflect differences between the characteristics of the subject and those of the comparable dataset(s) from which the indications of value are derived. As valuations are based on the financial principle of substitution, these adjustments are an attempt to account for the varying degrees of risk associated with the subject interest vis a vis "comparable" investments.

The following adjustments were considered during the valuation process. Not all are applicable for the given situation, but all were reviewed for applicability. Those discounts considered appropriate are discussed in detail below.

- •

- Discount for trapped-in capital gains

- •

- Key person discount

- •

- Discount for known or potential environmental liability

- •

- Discount for pending litigation

- •

- Portfolio discount (for unattractive assemblage of assets)

- •

- Concentration of customer or supplier base

- •

- Voting vs. non-voting stock adjustment

11

- •

- Block discount

- •

- Control premium/minority discount

- •

- Marketability discount

- •

- Expectations premium

6.2 Control Premium/Minority Discount

6.2.1 The Minority Stockholder's Situation

Minority stock interests in a "closed" corporation are usually worth much less than the proportionate share of the assets to which they attach…2

- 2

- Cravens v.Welch, 10 Fed. Supp. 94 (1935)

The above statement, from a 1935 stock valuation case that is still widely quoted, captures the essence of the minority stockholder's situation. This revelation comes as a shock to many people, who may have always assumed that a partial interest is worth a pro rata portion of the value of the total enterprise.

H. Calvin Coolidge, a former bank trust officer with extensive experience in dealing with and selling (or attempting to sell) minority interests in closely held companies, presents a cogent summary of the minority stockholder's position.

The holder of a minority interest can at best elect only a minority of the directors, and for corporations chartered in states which do not permit cumulative voting, he may not be able to elect even one director. Lacking control of the board of directors, he cannot compel payment of dividends which must be declared equally and which would give him his pro rata share of earnings. Lacking control of the board of directors, he cannot compel his election as an officer or his employment by the corporation, which the holders of the controlling interest can do, often with resultant handsome compensation. In short, the holder of a minority interest has no voice in corporate affairs and is at the mercy of the holders of the controlling interest who have no reason to pay anything but a token dividend, if any, and no reason to buy out the minority holder except at a nominal price.

A willing buyer contemplating purchase from a willing seller of a minority interest, being under no compulsion to buy (which would exclude a buyer already owning some shares whose new purchase would cover control), would suffer the same disadvantage of lack of control. The buyer is asked to make an investment with no assurance as to the certainty of current yield or as to when, or the amount at which, he may be able to liquidate his investment. Regardless, therefore, of the value of 100% of the corporation, the buyer will not purchase a minority interest except at a discount from its proportionate share of the value of 100% of the corporation.3

- 3

- H. Calvin Coolidge, "Discount for Minority Interest: Rev. Rul. 79-7's Denial of Discount Is Erroneous,"Illinois Bar Journal 68 (July 1980), p. 744

The lack of concurrence between the value of stock and the corporation's underlying assets was clearly established by the U.S. Supreme Court back in 1925:

The capital stock of a corporation, its net assets, and its shares of stock are entirely different things…the value of one bears no fixed or necessary relation to the value of the other.4

12

- 4

- Ray Consol. Copper Co. v.United States, 45 S. Ct. 526 (1925)

An oft-cited U.S. Tax Court case quoted the above, adding:

- 5

- Drayton Cochran et al., 7 T.C.M. 325 (1948)

That minority shareholders often find themselves disadvantaged compared to controlling shareholders is attested to by the fact that the oft-quoted, lengthy, and scholarly two volume treatiseO'Neal's Oppression of Minority Shareholders is doing well in its second edition, published in 1985. In the preface to that edition, the authors comment on the growing amount of minority shareholder litigation:

Most American lawyers do not realize the tremendous amount of litigation in this country arising out of shareholder disputes. Since the publication of the first edition of this treatise, the volume of litigation grounded on minority shareholder oppression—actual, fancied, or fabricated—has grown enormously, and the flood of litigation shows no sign of abating. The increase in litigation has been pronounced in both federal and state courts, with an especially large number of suits challenging the validity of "cash-out" mergers. Also worthy of note is that in the last four or five years there has been a substantial increase in the number of suits minority shareholders have brought for involuntary dissolution of their corporation or to force majority shareholders to purchase their shares.6

- 6

- F. Hodge O'Neal and Robert B. Thompson,O'Neal's Oppression of Minority Shareholders,2nd ed., vol. 1 (Wilmette, Ill.: Callaghan & Company, 1985), p. iii. The termcash-out merger is sometimes used to mean asqueeze-out orfreeze-out merger, in which minority shareholders receive cash for their shares. They cannot block the merger or demand consideration other than cash. If they are not satisfied with the amount of cash offered, their remedy is to demand an appraisal of the stock under dissenter's appraisal rights statutes. See, for example,Roland International Corp. v.Najjar, 407 A.2d 1032, 1033 (Del. S. Ca. 1979)

6.2.2 Control Premium

Due to the involuntary nature of the subject transaction, no minority discount will be applied to valuation methods that initially yield a whole company value. For methods that initially yield a marketable minority value, we will attempt to remove the minority discount through the application of a control premium.

The precise determination of an appropriate minority discount (or inversely, control premium can be extremely difficult, if not impossible. Two major bodies of empirical evidence are often used to estimate minority discounts:7

- 7

- Pratt,Discounts and Premiums, p. 62

- 1.

- Prices at which controlling interests are acquired in the public market compared with the preannouncement minority stock trading prices, and

- 2.

- Prices at which holding company interests sell compared with their underlying net asset values.

- a.

- REITs

- b.

- SEC-registered limited partnership interests

- c.

- Closed-end mutual funds

We used the SNL DataSource to build a control premium / minority discount database based on all whole bank transactions announced in the past twelve months. This data yielded a median control premium of 24.82%.

13

Given the nature of the Company and the block of stock being valued and after consideration of the various discount studies and bodies of empirical evidence appropriate to this valuation, it is our determination that a control premium of 24.82% is appropriate in this situation. Please refer to Exhibit K for additional information.

6.3 Marketability Adjustment

Generally, minority interests in privately held corporations command significant marketability discounts due to the difficulty associated with liquidating such interests. Several of the key factors in determining the appropriate marketability discount include:

- •

- The size and stability of dividends

- •

- Prospects for liquidity (probably length of holding period)

- •

- The pool of potential buyers

- •

- Growth prospects

Based on this analysis, and with the support of a number of discount studies (see Exhibit L for details), we determined that a marketability discount of 30% was appropriate for this valuation.

6.4 Application of Adjustments

The following table shows the application of valuation adjustments to the various values determined using the methods discussed above.

AMERICAN BANK & TRUST COMPANY

Valuation Methods Summary

Valuation Method

| | Method

Results Before

Adjustments

| | Result Type

Discount

(Premium)

| | Indicated

Whole Bank

Value Before

Adjustments

| | Entity Level

Marketability

Discount

(Premium)

| | Indicated

Whole Bank

Value After

Adjustments

| | Fair Value

per Share

| | Book

Multiple

| | Earnings

Multiple

|

|---|

| Book Value | | 14,069,647 | | | | 14,069,647 | | | | 14,069,647 | | | | 1.00 | | 15.41 |

| Comparable Sales—Whole Bank | | 21,679,854 | | | | 21,679,854 | | 30.00 | % | 15,175,898 | | 130.84 | | 1.08 | | 16.62 |

| Share Exchange | | 22,125,704 | | | | 22,125,704 | | 30.00 | % | 15,487,993 | | 133.53 | | 1.10 | | 16.96 |

| Public Company Multiples | | 19,094,478 | | -24.82 | % | 23,833,727 | | 30.00 | % | 16,683,609 | | 143.84 | | 1.19 | | 18.27 |

| Discounted Future Returns | | 19,098,881 | | -24.82 | % | 23,839,223 | | 30.00 | % | 16,687,456 | | 143.87 | | 1.19 | | 18.27 |

| Earnings Capitalization | | 19,325,602 | | -24.82 | % | 24,122,216 | | 30.00 | % | 16,885,551 | | 145.58 | | 1.20 | | 18.49 |

| |

| |

| |

| |

| | Fair Market

Value per

Share

| | Book

Multiple

| | Earnings

Multiple

| | Dividend

Yield

| |

|---|

| Total Shares Outstanding (fully diluted) | | 115,987 | | | | | | Average | | 139.53 | | 1.15 | | 17.72 | | 1.43 | % |

| Trailing 12 Month Earnings | | 913,297 | | | | | | Maximum | | 145.58 | | 1.20 | | 18.49 | | 1.37 | % |

| Trailing 12 Month Dividend | | 231,974 | | | | | | Minimum | | 130.84 | | 1.08 | | 16.62 | | 1.53 | % |

| EPS | | 7.87 | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | |

14

7 Valuation Conclusion

After considering all relevant information and the results of various valuation methods, it falls to the valuator to use judgment and experience to analyze the results and determine the ultimate fairness of the proposed transaction.

Based on all factors that we deem relevant and assuming the accuracy and completeness of the information and data provided to us, we conclude that the cash consideration of $140.24 per share to be paid by the Company is fair, from a fýnancial point of view, to all shareholders of the Company, including those shareholders receiving the cash consideration.

8 Valuator's Certification

I certify that, to the best of my knowledge and belief

- 1.

- The statements of fact in this report are true and correct.

- 2.

- Neither the valuator, nor any officer, agent or employee of National Capital, L.L.C. has any present or contemplated interest in the subject company, nor any personal bias with respect to the parties involved.

- 3.

- National Capital, L.L.C. has received a fee for the preparation of this valuation report. The fee paid to National Capital, L.L.C. was not contingent on any action or event resulting from the analysis, opinions or conclusions in the report.

- 4.

- This valuation report is valid only for the valuation period indicated in the report and only for the express purpose stated herein.

- 5.

- The report analyses, opinions and conclusions are limited only by the reported assumptions and limiting conditions, and are my personal, unbiased professional analyses, opinions and conclusions.

- 6.

- The valuator's analyses, opinions and conclusion were developed, and this report was prepared, in conformity with the National Association of Certified Valuation Analysts' standards for conducting and reporting on business valuations.

Jonathan W. Briggs, CFA

February 11, 2004 | | |

15

9 Valuator's Qualifications

Jonathan W. Briggs

| Experience | | 2003-Present National Capital, L.L.C. Baton Rouge, LA |

| | | Principal |

| | | • | | Perform business valuations for purposes including ESOP Formation, Contribution and Dissolution; Family Limited Partnership Formation and Gifting, Estate Valuation; Merger/Acquisition; Subchapter-S Conversion; Private Placements; etc. |

| | | • | | Provide investment banking and financial advisory services to publicly traded and privately held companies across a wide range of industries. |

| | | • | | Act as Buyer's, Seller's or Third-Party Representative in merger transactions. |

| | |

|

| | | 2003-Present American Planning Corporation Baton Rouge, LA |

| | | Principal |

| | | • | | Act as a Financial Consultant to Financial Institutions and Financial Holding Companies. |

| | | • | | Provide short- and long-range financial planning services based on valueenhancement strategies. |

| | | • | | Develop and value long-range strategic business plans. |

| | |

|

| | | 1997-2003 Chaffe & Associates, Inc. New Orleans, LA |

| | | Assistant Vice President |

| | | • | | Perform business valuations for purposes including ESOP Formation, Contribution and Dissolution; Family Limited Partnership Formation and Gifting, Estate Valuation; Merger/Acquisition; Subchapter-S Conversion; Private Placements; etc. |

| | | • | | Provide investment banking and financial advisory services to publicly traded and privately held companies across a wide range of industries. |

| | | • | | Act as Buyer's, Seller's or Third-Party Representative in merger transactions. |

|

| Education | | University of New Orleans New Orleans, LA |

| | | • | | B.S.—Finance |

|

Memberships

and

Designations |

|

Association for Investment Management & Research (Chartered Financial Analyst Designation) |

16

Exhibit A

National Economic Data and Analyses

The Federal Reserve Board

January 14, 2004

Summary

Prepared at the Federal Reserve Bank of Kansas City and based on information collected before January 6, 2004. This document summarizes comments received from businesses and other contacts outside the Federal Reserve and is not a commentary on the views of Federal Reserve officials.

Reports from Federal Reserve Districts suggest that the nation's economy has continued to improve since the last survey. The strongest report came from the San Francisco district, which said its economy expanded soundly. Most other districts also gave quite favorable reports, saying their economies improved, strengthened further, or grew at a moderate pace. However, Cleveland, Chicago, and Dallas reported only slow or modest growth, and St. Louis said conditions were mixed. Retailers and manufacturers reported that prices were generally steady despite increases for raw materials.

Holiday retail sales were generally positive across the country, and auto sales either improved or held steady in most districts. Manufacturing activity increased in nearly all districts, and New York, Philadelphia, and Kansas City noted some growth in factory employment. Housing remained strong, particularly in the Boston and San Francisco districts. Commercial real estate was still weak, although a few districts reported signs of firming. Travel and tourism activity increased considerably, and gains were reported in most other service industries as well. Bank loan demand was flat or slightly lower, with credit quality generally unchanged. Energy and agricultural activity was steady in most districts, although the appearance of mad cow disease created considerable uncertainty in the cattle industry.

Along with the increase in overall economic activity, many districts reported modest improvements in labor markets. These improvements took the form of reduced layoffs or modestly increased hiring, although new hiring was still quite minimal in several districts and most types of workers remained easy to recruit. Health care and other employee benefit costs continued to rise. However, with labor markets still slack, wage pressures remained generally subdued. Retail prices were generally flat, with some districts reporting less discounting of holiday retail prices than in previous years. Manufacturers in most districts also held their selling prices steady, despite substantial increases in the prices of some raw materials such as steel and natural gas.

Consumer Spending

Reports on holiday retail sales were generally upbeat across the country, particularly for sales during the last two weeks of 2003. San Francisco gave the strongest report, saying robust sales led to considerable year-over-year gains. Holiday sales were also quite solid in the Boston, Philadelphia, St. Louis, and Kansas City districts. Most other districts reported more modest year-over-year sales growth, although some of these districts noted an improvement in sales at the end of December. Cleveland, on the other hand, said retailers were generally disappointed by sluggish sales during the holidays. All districts reporting on store inventories said stock levels were generally in good shape for 2004, and all districts reporting on expectations for future retail sales anticipate continued improvement in the months ahead.

Looking across product categories, sales of high-end items were characterized as especially strong in several districts, including New York, Philadelphia, Atlanta, and San Francisco. Likewise, electronics and home furnishings sold well in many districts. On the other hand, sales of apparel were reported to be soft in the Philadelphia and Cleveland districts, and San Francisco noted heavy discounting at lower-

A-1

priced apparel stores. Indeed, sales at discount stores in general were reported to have been below plan in several districts, including New York, Cleveland, and Kansas City.

Reports on auto sales were also generally positive, with most districts reporting either steady or improving sales at the end of the year. Cleveland, St. Louis, and Minneapolis characterized new vehicle sales as "strong" or "solid" in December, although St. Louis reported that sales of used cars were not as robust as sales of new cars. Richmond, Chicago, and San Francisco all noted some improvement in vehicle sales from previous months, while Atlanta, Kansas City, and Dallas said sales were mixed or flat. Philadelphia noted that a seasonal slowing in auto sales resulted in a buildup of inventories, and dealers in the Cleveland district were worried about their ability to sell all of their 2003 models. Otherwise, though, districts reporting expectations for auto sales were generally optimistic about 2004.

Manufacturing

Nearly all districts reported increases in manufacturing activity in December, and several districts noted that factory employment had begun to edge up as well. Chicago reported broad-based improvement across manufacturing industries, and Dallas and San Francisco said factory activity increased in a variety of sectors. Philadelphia, Richmond, and Kansas City noted strong orders in December, and Boston said several firms had been "pleasantly surprised" by recent increases in orders. Factory employment was reported to have posted modest overall gains in the New York, Philadelphia, and Kansas City districts, and factory jobs also reportedly picked up in select industries or for select occupations in the Boston, Richmond, and San Francisco districts.

Looking across industries, primary metal manufacturing was said to be improving in the Philadelphia, Cleveland, and Richmond districts, and production of various high-tech goods continued to rebound in the Boston, Dallas, and San Francisco districts due to increased capital spending by customers. Several districts also noted increases in the production of industrial machinery, building materials, and transportation equipment. On the negative side, St. Louis reported layoffs in the biotechnology, food, and tobacco industries. Petrochemical producers suffered from overcapacity in the Dallas district and continued to lay off workers in the Atlanta district. In addition, producers of paper goods in the Boston and Philadelphia districts reported some weakness.

Manufacturers across the country generally expect factory conditions to continue to improve in the months ahead, and several districts noted that capital spending in 2004 will be somewhat higher than in 2003. Much of the increased spending will go towards replacement of outdated IT and other capital equipment, but both Chicago and Kansas City reported a few firms plan plant expansions as well. Exceptions to the optimistic outlook included textile producers in the Boston and Richmond districts, who continue to suffer from excess capacity.

Real Estate and Construction

Residential real estate activity remained robust, with home sales and new construction reported to be strong in most districts. In the Boston district, home sales in Massachusetts continued to rise at double-digit rates, while housing activity in other parts of the district returned to more normal levels following boom conditions during the last two years. In the San Francisco district, home sales increased and home price appreciation remained solid. In most other districts, home sales and single-family homebuilding were reported to be holding steady at high levels. The only districts reporting some slowdown in overall housing activity were Chicago and Dallas. Contacts in the Chicago district said some easing was inevitable given the previous boom, but Dallas reported that high inventories of existing homes were becoming a concern. Both Boston and Kansas City reported that the high-end market was weaker than the entry-level market, although tentative signs of a turnaround in high-end construction were noted in Kansas City. The multifamily market remained weak in the few districts reporting on this sector, the only bright spot being a modest recovery in apartment rents in New York.

A-2

Commercial real estate activity remained weak, although there were signs of improvement in a few districts. In most districts, commercial real estate markets and nonresidential construction were described as soft with little improvement expected in the near term. Commercial builders in the Cleveland district viewed 2003 as a weak year and did not expect conditions to improve for at least the next six months. In the Chicago district, vacancy rates remained elevated in most segments of the market, and contacts saw no indication of a firming in demand at the end of the year. On a more positive note, however, a few districts reported either a pickup in activity or improvement in expectations for the future. For example, Atlanta reported that commercial construction activity was still generally weak but that leasing activity continued to improve. In the Dallas district, the office market remained soft, but contacts were increasingly optimistic that the worst was behind them. The strongest report came from the Richmond district, where contacts were highly encouraged by a pickup in leasing activity late in the year.

Tourism and Services

Travel and tourism activity improved substantially. Boston, Richmond, Minneapolis, Kansas City and San Francisco all reported a surge in visitors to ski resorts due to very good snow conditions, while Atlanta noted increased optimism about winter tourism in Florida and New Orleans. Boston also reported a positive outlook for international bookings due to the lower dollar and promotional airfares. Demand for hotel rooms in New York remained strong, as brisk leisure travel activity more than compensated for a continued slump in business travel. In other reports on business travel, Atlanta observed a modest increase in convention bookings, while Boston noted increased spending on corporate entertaining and higher bookings for corporate meetings in 2004.

Activity in other service industries generally expanded as well. Several districts reported increased demand for freight transport services. For example, Cleveland observed busy trucking activity serving retailers, Dallas reported increased rail shipments of lumber due to strength in construction, and San Francisco noted that exports and holiday imports kept several seaports operating at capacity. Looking at other sectors, Dallas reported robust growth in legal services, Philadelphia noted improved demand at marketing firms, and New York cited unusually brisk hiring for office jobs. Boston reported little change in overall demand for insurance, with slightly higher sales of long-term care products but lower revenue from large-property insurance. On a negative note, Richmond indicated lackluster activity at several business support and technical firms.

Banking

Overall demand for bank loans either remained unchanged or declined somewhat in most districts. Home mortgage lending continued to fall due mainly to lower refinancing activity. Banks in the Chicago district reported that new mortgage originations were also slowing somewhat, although such lending remained fairly strong. Demand for consumer loans fell somewhat in the New York and St. Louis districts and rose in the Philadelphia and Kansas City districts. Business loan demand increased in the Philadelphia, Richmond, and St. Louis districts but held steady or weakened in other districts. Banks in the Richmond district attributed the increased demand for business loans to the stronger economy and were optimistic about lending prospects for 2004. In the Chicago and San Francisco districts, banks reported more inquiries about lending terms from small businesses, even though overall business lending remained flat.

Credit quality and lending standards were little changed in most districts. Credit quality was described as stable in the Philadelphia district, although some banks reported higher defaults on consumer loans. Banks in the New York district reported fewer delinquencies in all loan categories except business loans. In the Chicago district, business loan quality improved, but home mortgage loan quality eroded slightly. The only changes in credit standards were in the New York district, where they were tightened

A-3

slightly for non-mortgage loans, and in the Chicago district, where some large banks were said to be loosening standards on business loans in an effort to boost lending.

Natural Resources and Agriculture

Activity in natural resource industries generally held steady. Ore mining in the Minneapolis district continued at a strong pace, as some mines produced near capacity while other, previously shut, mines reopened. Energy activity in the Dallas district was little changed, but contacts noted continuing excess capacity in the oil services and machinery industry. Oil and gas drilling in the Kansas City district remained unchanged at levels considerably higher than a year ago, while Minneapolis reported a decrease in both oil and natural gas exploration. Looking ahead, natural gas producers in the Kansas City district plan increased capital spending in anticipation of continued strong production, but contacts in both the Kansas City and Dallas districts expect some decline in oil production in coming months.

While most districts reported steady conditions in the farm economy, the appearance of mad cow disease created substantial uncertainty in the cattle industry. Farm incomes were supported in the Chicago district by strong hog production and by rising corn and soybean prices, while incomes in the Kansas City district were maintained by high soybean prices and still-elevated cattle prices. In the San Francisco district, farmers benefited from strong holiday sales of cut flowers and Christmas trees. Crop conditions in the Atlanta and Dallas districts were reported as stable. However, farmers in some parts of the Minneapolis and Kansas City districts continued to suffer from drought, and Richmond reported harvest and planting delays due to excessive precipitation. The emergence of a case of mad cow disease in Washington state resulted in a great deal of uncertainty for cattle ranchers. Contacts in several districts noted substantial declines in cattle prices due to foreign bans on U.S. beef exports. The uncertainty was causing ranchers in the Kansas City and Dallas districts to take a wait-and-see approach toward herd adjustments. San Francisco, on the other hand, reported that the appearance of mad cow disease was boosting sales of range-raised beef.

Labor Markets, Wages, and Prices

Most districts reported modest improvements in labor markets in December. San Francisco noted a pickup in hiring, Minneapolis reported more hiring announcements than layoff announcements, and Kansas City said layoffs dropped considerably. Likewise, demand for temp workers increased in the Philadelphia and Richmond districts, and Chicago said the seasonal decrease in temp employment this year was less than in the previous two years. On the other hand, hiring was said to be quite minimal in several districts. Cleveland, for example, noted that most firms still do not plan to increase payrolls in the near future. In addition, while hiring improved somewhat in the Atlanta district, firms generally remained reluctant to add full-time staff. Both Kansas City and Dallas noted some pickup in demand for high-tech workers, although such workers were still easily recruited in the Kansas City district and some types of high-tech and telecom work in the Dallas district continued to be outsourced overseas. Acute labor shortages were generally reported only for select health care fields, with some hospitals in the Atlanta district recruiting overseas to fill open nursing positions.

Wage pressures generally remained subdued throughout the nation, but most districts continued to report greater upward pressure on health care and other employee benefit costs. Chicago, Kansas City and San Francisco described wage increases as "weak" or "modest" and Boston stated that wages were mostly stable. Exceptions were reported in the Dallas district, with wages subject to downward pressure in the airline industry but upward pressure in certain occupations such as skilled mechanics. Meanwhile, districts consistently reported that employee benefit costs continued to increase. San Francisco said that the improving job market was making it harder to shift increases in health care premiums to workers, resulting in slightly higher growth of total compensation.

A-4

Most districts reported little change in final goods prices, but costs of some raw materials rose noticeably. Retail prices were generally stable. Atlanta, Kansas City, Dallas, and San Francisco all reported less discounting of holiday retail prices than in previous years, although a few other districts said holiday discounts were similar to last year. In manufacturing, the most widely cited increase in raw materials costs was for steel. Contacts in the Cleveland district said steel producers were raising prices to cover the increased cost of their own inputs, such as scrap and iron ore, and that steel prices were likely to continue rising through the first quarter. Price increases were also reported in some districts for copper and aluminum. In the Boston district, prices of lumber and plywood were reported to have fallen back somewhat from the highs reached in the third quarter, but contacts in other districts said these prices were still well above year-ago levels. In most districts, manufacturing firms were reported to still be having difficulty passing input costs on to their customers. In the Dallas district, petrochemical producers held their selling prices steady in the face of sharply rising natural gas prices, and trucking firms kept their rates unchanged despite higher fuel costs. The only signs of a change in pricing power were in the New York and Kansas City districts, where some firming in selling prices was reported.

A-5

Exhibit B

Regional Economic Data and Analyses

FDIC State Profile

WINTER 2003

Louisiana

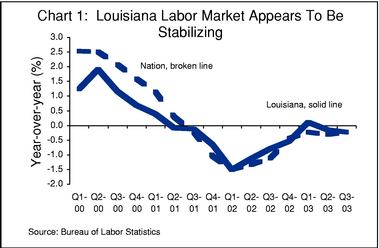

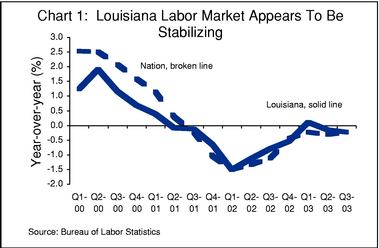

Employment in Louisiana remained weak during third quarter 2003.

- •

- Employment levels declined in Louisiana during the past two years, although the rate of loss has diminished in the last 18 months (see Chart 1).

- •

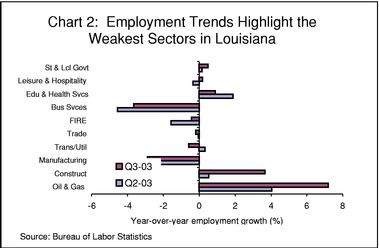

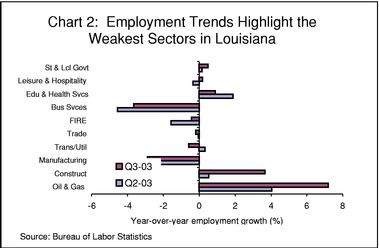

- During the third quarter, the most significant job losses occurred in services and manufacturing (see Chart 2).

- •

- In contrast, employment in the energy and construction industries expanded strongly on a year-over-year basis as of third quarter 2003.

B-1

- •

- Employment was flat in the leisure and hospitality sector, increasing only 0.2 percent on a year-over-year basis as of third quarter 2003. This sector accounts for more than one in ten jobs in Louisiana, and is an important economic driver in the metro areas of the state.

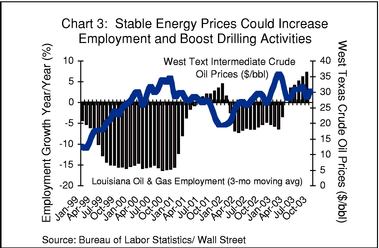

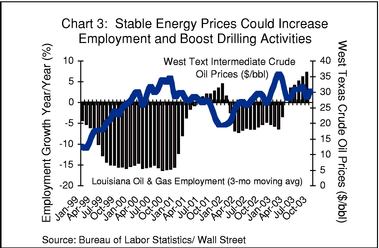

Employment in the Louisiana oil and gas sector may benefit from stable energy prices.

- •

- The still dominant energy sector accounts for 19 percent of gross state product as of year-end 2001 (most recent data available), down from over 30 percent at year-end 1981.

- •

- Energy sector employees are well compensated; as a result, even modest changes in the industry have a significant effect on personal income in natural resource dependent areas. Employment levels in the sector typically rise when oil prices exceed a mid-twenty dollar per barrel price point and contract below that level. The Organization of the Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC) has sought to maintain prices at or above $25 per barrel, a goal achieved since early 2002 (see Chart 3).

- •

- Favorable commodity prices for key crops coupled with generally robust production figures indicate that 2003 net farm incomes will exceed results from recent years.

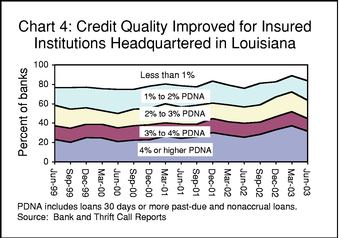

Asset quality improved in the second half of 2003.

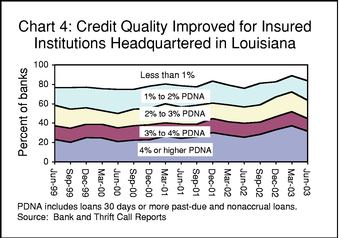

- •

- Past-due and nonaccrual loan levels reported by insured institutions headquartered in Louisiana reached a cyclical peak at year-end 2001 and remained elevated during 2002.1

- 1

- The median past-due ratio peaked at 2.67 percent at year-end 2001 and remained relatively unchanged at year-end 2002.

- •

- The median consumer past-due and nonaccrual loan ratio was 2.54 percent in second quarter 2003, down from 2.72 percent the prior quarter, but 10 basis points above the 2.44 percent ratio one year earlier, indicating on-going pressure in overall credit quality for insured institutions in Louisiana (see Chart 4).

B-2

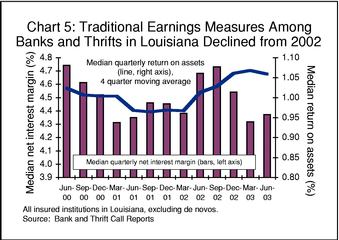

Future earnings among insured institutions in Louisiana may be pressured.

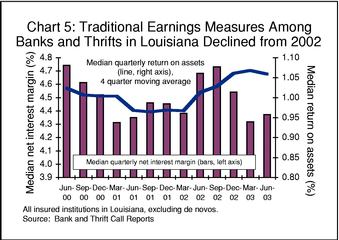

- •

- The median quarterly net interest margin (NIM) was 4.37 percent in second quarter 2003 for insured institutions in Louisiana, virtually unchanged from one quarter ago, but down significantly from 4.68 percent at second quarter 2002 (see Chart 5).

- •

- As the national economy gains momentum, interest rates are expected to rise. Traditionally, net interest margins for Louisiana community banks have been adversely affected by rising interest rates, as most insured institutions are liability sensitive, with liabilities repricing more quickly than assets.

B-3

State Profile

Louisana at a Glance

General Information

| | Jun-03

| | Jun-02

| | Jun-01

| | Jun-00

| | Jun-99

| |

|---|

| Institutions (#) | | 171 | | 174 | | 177 | | 186 | | 188 | |

| Total Assets (in thousands) | | 51,657,794 | | 47,476,679 | | 45,609,598 | | 54,861,163 | | 53,515,538 | |

| New Institutions (# < 3 years) | | 0 | | 4 | | 12 | | 15 | | 15 | |

| New Institutions (# < 9 years) | | 17 | | 17 | | 17 | | 19 | | 21 | |

Capital

|

|

Jun-03

|

|

Jun-02

|

|

Jun-01

|

|

Jun-00

|

|

Jun-99

|

|

|---|

| Tier 1 Leverage (median) | | 9.98 | | 10.31 | | 10.07 | | 10.40 | | 10.29 | |

Asset Quality

|

|

Jun-03

|

|

Jun-02

|

|

Jun-01

|

|

Jun-00

|

|

Jun-99

|

|

|---|

| Past-Due and Nonaccrual (median %) | | 2.54 | % | 2.32 | % | 2.32 | % | 2.02 | % | 2.35 | % |

| Past-Due and Nonaccrual > = 5% | | 32 | | 28 | | 26 | | 23 | | 25 | |

| ALLL/Total Loans (median %) | | 1.29 | % | 1.29 | % | 1.25 | % | 1.27 | % | 1.31 | % |

| ALLL/Noncurrent Loans (median multiple) | | 1.28 | | 1.89 | | 1.44 | | 1.70 | | 1.67 | |

| Net Loan Losses/Loans (aggregate) | | 0.31 | % | 0.35 | % | 0.38 | % | 0.34 | % | 0.44 | % |

Earnings

|

|

Jun-03

|

|

Jun-02

|

|

Jun-01

|

|

Jun-00

|

|

Jun-99

|

|

|---|

| Unprofitable Institutions (#) | | 4 | | 1 | | 7 | | 12 | | 14 | |

| Percent Unprofitable | | 2.34 | % | 0.57 | % | 3.95 | % | 6.45 | % | 7.45 | % |

| Return on Assets (median %) | | 1.12 | | 1.10 | | 0.98 | | 1.10 | | 1.01 | |

| | 25th Percentile | | 0.77 | | 0.78 | | 0.67 | | 0.74 | | 0.69 | |

| Net Interest Margin (median %) | | 4.33 | % | 4.55 | % | 4.34 | % | 4.67 | % | 4.48 | % |

| Yield on Earning Assets (median) | | 6.06 | % | 6.82 | % | 8.08 | % | 8.09 | % | 7.71 | % |

| Cost of Funding Earning Assets (median) | | 1.78 | % | 2.43 | % | 3.82 | % | 3.62 | % | 3.31 | % |

| Provisions to Avg. Assets (median) | | 0.11 | % | 0.13 | % | 0.11 | % | 0.11 | % | 0.10 | % |

| Noninterest Income to Avg. Assets (median) | | 0.92 | % | 0.84 | % | 0.83 | % | 0.80 | % | 0.77 | % |

| Overhead to Avg. Assets (median) | | 3.42 | % | 3.32 | % | 3.38 | % | 3.45 | % | 3.31 | % |

Liquidity/Sensitivity

|

|

Jun-03

|

|

Jun-02

|

|

Jun-01

|

|

Jun-00

|

|

Jun-99

|

|

|---|

| Loans to Deposits (median %) | | 70.87 | % | 72.93 | % | 71.12 | % | 71.62 | % | 67.75 | % |

| Loans to Assets (median %) | | 60.23 | % | 60.83 | % | 61.39 | % | 60.85 | % | 57.22 | % |

| Brokered Deposits (# of Institutions) | | 13 | | 13 | | 10 | | 10 | | 6 | |

| Bro. Deps./Assets (median for above inst.) | | 0.79 | % | 1.35 | % | 1.35 | % | 2.13 | % | 4.52 | % |

| Noncore Funding to Assets (median) | | 18.71 | % | 18.36 | % | 18.20 | % | 17.66 | % | 16.71 | % |

| Core Funding to Assets (median) | | 68.69 | % | 68.85 | % | 69.55 | % | 69.68 | % | 71.01 | % |

Bank Class

|

|

Jun-03

|

|

Jun-02

|

|

Jun-01

|

|

Jun-00

|

|

Jun-99

|

|

|---|

| State Nonmember | | 122 | | 124 | | 126 | | 132 | | 132 | |

| National | | 15 | | 16 | | 16 | | 19 | | 20 | |

| State Member | | 3 | | 2 | | 2 | | 2 | | 3 | |

| S&L | | 20 | | 21 | | 21 | | 21 | | 21 | |

| Savings Bank | | 9 | | 8 | | 9 | | 9 | | 9 | |

| Mutually Insured | | 2 | | 3 | | 3 | | 3 | | 3 | |

MSA Distribution

| |

| | # of Inst.

| | Assets

| | % Inst.

| | % Assets

| |

|---|

| No MSA | | | | 90 | | 10,296,361 | | 52.63 | % | 19.93 | % |

| New Orleans LA | | | | 29 | | 30,813,743 | | 16.96 | % | 59.65 | % |

| Lafayette LA | | | | 22 | | 4,774,063 | | 12.87 | % | 9.24 | % |

| Baton Rouge LA | | | | 10 | | 2,634,371 | | 5.85 | % | 5.10 | % |

| Shreveport-Bossier City LA | | | | 8 | | 751,601 | | 4.68 | % | 1.45 | % |

| Houma LA | | | | 6 | | 708,720 | | 3.51 | % | 1.37 | % |

| Monroe LA | | | | 2 | | 458,659 | | 1.17 | % | 0.89 | % |

| Lake Charles LA | | | | 2 | | 878,973 | | 1.17 | % | 1.70 | % |

| Alexandria LA | | | | 2 | | 341,303 | | 1.17 | % | 0.66 | % |

B-4

The Federal Reserve Board

January 14, 2004

Federal Reserve Districts

Sixth District—Atlanta

Summary

Reports from the Sixth District indicated that the pace of economic growth remained favorable during November and December. District retailers gave encouraging early reports on holiday sales and most contacts noted that activity met or exceeded year-ago levels. Auto sales were mixed, with foreign models outperforming domestic brands. Strength in the District's residential housing markets continued, whereas commercial construction remained generally weak. Reports noted modest improvement in the industrial sector, and some contacts reported an increase in capital spending during November and December. The District's tourism and hospitality sector continued to improve late in the year. Responses from the financial sector were also mostly positive. Labor market reports firmed a bit in November and December, although employers remained cautious. Prices were described as stable overall.

Consumer Spending

Initial reports from District retailers indicated that holiday sales met or exceeded year-ago levels. Contacts noted that the combination of lean inventories and strong sales resulted in fewer discounts than in recent years. In particular, less discounting was noted after Christmas. Several contacts reported that high-end merchandise did well over the holiday season. Electronics and home-related products were also strong sellers. Generally, retailers were upbeat about their prospects for first-quarter sales.

Vehicle sales in November and December were mixed, according to reports from auto dealers. Some contacts noted that December is traditionally a low-volume month, although foreign model sales were quite strong late in the year. Most contacts reported that a reduction in the level of incentives had not significantly reduced sales or floor traffic at dealerships.

Real Estate

District single-family housing markets ended the year strongly, with both construction and sales continuing at a steady pace. Commercial markets were mixed. Commercial construction remained generally weak in November and December, while leasing activity continued to improve. Local industry analysts reported that improvements in the commercial real estate market were expected in 2004.

Manufacturing and Transportation

District contacts reported that manufacturing production continued to recover in November and December, and industrial energy sales had stabilized in some parts the District. Some contacts noted that previously delayed capital spending plans have been revived, especially IT equipment and infrastructure. Reports cited increased confidence in the sustainability of economic growth, tax law changes, and the need to replace outdated and worn equipment as reasons for the pickup in capital spending. Auto parts producers continued to announce plans for new plants, and tractor and trailer producers reported increasing orders over last year. New military contracts boosted activity for

B-5

shipyards and military equipment suppliers. Less positively, Louisiana's petrochemical industry continued to pare employment rolls.

District trucking contacts continued to report gains in seasonal freight demand late in the year. Airfreight tonnage improved from yearearlier levels for both domestic and international cargo in Atlanta and Miami.

Tourism and Business Travel

The District's tourism and hospitality industry continued to improve at year-end. In Miami, restaurants were said to be hiring aggressively, and south and central Florida tourism officials were upbeat about the current tourist season. Tennessee hotel occupancy rates were picking up in November and December from a year earlier as well. New Orleans tourism industry officials were upbeat about the first half of 2004, and Atlanta contacts reported a modest increase in convention bookings for 2004.

Banking and Finance

Responses from the financial sector were mostly positive. Deposit growth held steady or improved in much of the region from a year ago. Commercial loan demand, however, remained weak. Credit quality continued to strengthen and past due loans at banks were below year-ago levels. Most banks were reported to be moving ahead with capital expenditures to improve operating efficiency.

Employment and Prices

Reports on hiring were more positive in November and December than in previous reports, but employers continued to be cautious regarding adding full-time staff. Several businesses reported that they were keeping a lid on current payrolls but were increasing the amount of outsourcing. In south Florida, seasonal hiring was reportedly stronger than it has been for several years. Hospitals throughout the District continued to recruit internationally to help meet the nursing shortage.

Most reports indicated that businesses were not raising prices. But one report did note that increases in raw material costs were being passed on to customers, whereas wage and benefit increases were not being passed on. Prices for timber products remained high because of relatively low supplies and strong housing construction activity in the District.

Agriculture

Conditions remained mostly favorable for the District's crops. The harvest of sugar cane, citrus crops and vegetables was underway in some areas. The discovery of mad cow disease in Washington was expected to have an effect on the region's economy through lower cattle prices.

B-6

The Federal Reserve Board

January 14, 2004

Federal Reserve Districts

Eleventh District—Dallas