RAY A. GOLDBERG

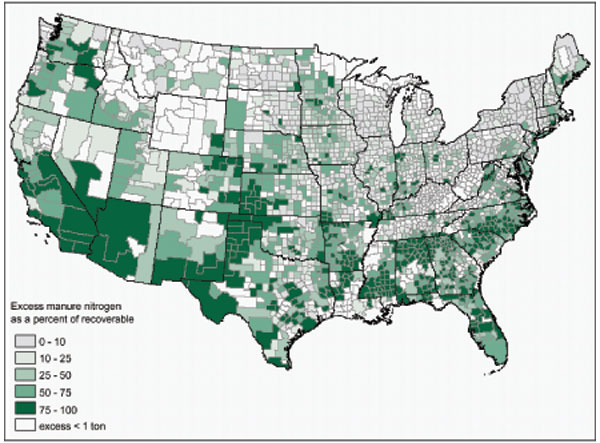

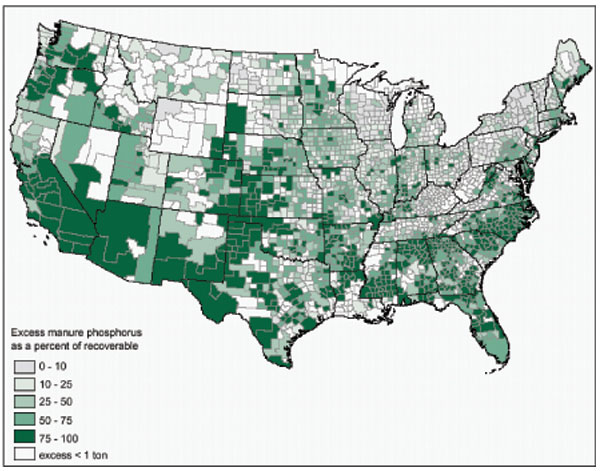

LAURE MOUGEOT STROOCK Environmental Power Corporation: Changing Manure Into Gold? Joe Cresci and Donald “Andy” Livingston, the two founders of Environmental Power Corporation (EPC), a small company developing renewable energy projects with $53.5 million revenues in 2001, were wrapping up the presentation of their “manure-to-money” digester system, a facility that extracted methane from animal waste through anaerobic digestion and used it to generate electricity. The dozen dairy farmers fromWisconsin who seemed so quiet when Cresci and Livingston had begun, now assailed them with questions about the technology and the financial feasibility of their Product. In the spring of 2002, the mood of farmers involved in large Concentrated Animal Feeding Operations (CAFOs) was one of caution. Under a new regulation from U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) and the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) coming into force at the end of 2002, all CAFO operators would have to develop and implement technically sound, economically feasible, and site specific nutrient management plans for properly managing the manure produced at their facilities. To comply with these new dispositions, they might have to reduce their herd size, buy new land for additional manure spreading, or invest in a digester. Digesters reduced odor and converted organic compounds into methane and plant nutrients. Either way, this meant additional costs that would hurt many farmers who were already heavily leveraged. Several features in Cresci and Livingston’s demonstration had caught their attention. First, unlike other digesters, the EPC digester not only helped manage farm wastes, but also produced large amounts of utility grade electricity that could be delivered at peak hours. Hence, in addition to recouping capital costs, farmers could make profits from multiple revenue streams including electricity sales at a premium rate, pollution offset credits, heat, refrigeration, and residual co-products such as compost or fertilizers. Second, EPC had packaged its product to remove most of the burdens associated with financing and operating the facilities. Finally, as a pollution prevention tool as well as a renewable energy producer, the project was likely to benefit from support programs of the EPA, the USDA, and the Department of Energy (DOE). Yet, Cresci and Livingston still had several obstacles to overcome to achieve their aggressive target of 226 facilities operating by 2006. EPC’s facilities used a Danish technology with a spotless track record, from both an engineering and an economic standpoint. But the Danish digesters were significantly smaller in size and benefited from advantageous national support programs. Could EPC replicate the Danish model at a larger scale under less favorable political and economic conditions?

Professor Ray A. Goldberg and Research Associate Laure Mougeot Stroock prepared this case. HBS cases are developed solely as the basis for class discussion. Cases are not intended to serve as endorsements, sources of primary data, or illustrations of effective or ineffective management.Copyright © 2002 President and Fellows of Harvard College. To order copies or request permission to reproduce materials, call 1-800-545-7685, write Harvard Business School Publishing, Boston, MA 02163, or go to http://www.hbsp.harvard.edu. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, used in a spreadsheet, or transmitted in any form or by any means—electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise—without the permission of Harvard Business School.

|