Exhibit 99.1

SUMMARY BUDGET 2017/18

2 / BUDGET 2017

Summary Budget

For the Fiscal Year Ending March 31, 2018 (Millions of Dollars)

With Comparative Data for the Fiscal Year Ending March 31, 2017

| | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | |

| | | 2017/18 | | 2016/17 | | 2016/17 | | Per Cent Change 2017/18 Budget from 2016/17 |

| | | Budget | | Forecast | | Budget | | Forecast | | Budget |

| | | | | |

Revenue | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | |

| | | | | |

Income Taxes | | | | 4,194 | | | | | 3,950 | | | | | 3,868 | | | | | 6.2 | | | | | 8.4 | |

| | | | | |

Other Taxes | | | | 4,497 | | | | | 4,395 | | | | | 4,396 | | | | | 2.3 | | | | | 2.3 | |

| | | | | |

Fees and Other Revenue | | | | 2,307 | | | | | 2,307 | | | | | 2,220 | | | | | - | | | | | 3.9 | |

| | | | | |

Federal Transfers | | | | 4,163 | | | | | 4,117 | | | | | 4,108 | | | | | 1.1 | | | | | 1.3 | |

| | | | | |

Net Income of Government Business Enterprises | | | | 705 | | | | | 644 | | | | | 674 | | | | | 9.5 | | | | | 4.6 | |

| | | | | |

Sinking Funds and Other Earnings | | | | 235 | | | | | 230 | | | | | 209 | | | | | 2.2 | | | | | 12.4 | |

| | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | |

| | | | | |

Total Revenue | | | | 16,101 | | | | | 15,643 | | | | | 15,475 | | | | | 2.9 | | | | | 4.0 | |

| | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | |

| | | | | |

Expenditure | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | |

| | | | | |

Health | | | | 6,681 | | | | | 6,475 | | | | | 6,504 | | | | | 3.2 | | | | | 2.7 | |

| | | | | |

Education | | | | 4,400 | | | | | 4,284 | | | | | 4,281 | | | | | 2.7 | | | | | 2.8 | |

| | | | | |

Families | | | | 2,159 | | | | | 2,037 | | | | | 2,037 | | | | | 6.0 | | | | | 6.0 | |

| | | | | |

Community, Economic and Resource Development | | | | 1,531 | | | | | 1,511 | | | | | 1,521 | | | | | 1.3 | | | | | 0.7 | |

| | | | | |

Justice and Other Expenditures | | | | 1,294 | | | | | 1,270 | | | | | 1,282 | | | | | 1.9 | | | | | 0.9 | |

| | | | | |

Debt Servicing | | | | 991 | | | | | 938 | | | | | 911 | | | | | 5.7 | | | | | 8.8 | |

| | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | |

| | | | | |

Total Expenditure | | | | 17,056 | | | | | 16,515 | | | | | 16,536 | | | | | 3.3 | | | | | 3.1 | |

| | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | |

| | | | | |

In-Year Adjustments/Lapse | | | | (115) | | | | | – | | | | | (150) | | | | | | | | | | | |

| | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | |

| | | | | |

Net Income (Loss) | | | | (840) | | | | | (872) | | | | | (911) | | | | | | | | | | | |

| | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | |

NOTES:

| • | | The 2016/17 forecast and budget have been restated to be consistent with the 2017/18 budget presentation. |

| • | | In-Year Adjustments/Lapse could be an increase in revenue and/or decrease in expenditures. |

| • | | Numbers may not add due to rounding. |

BUDGET 2017 / 3

SUMMARY BUDGET 2017/18

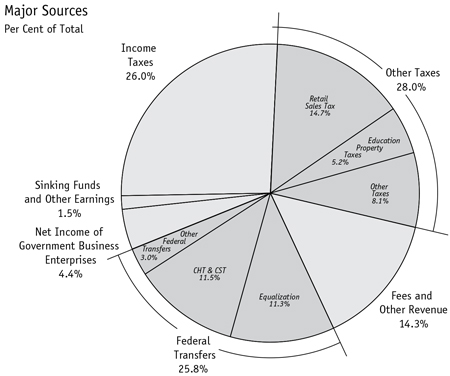

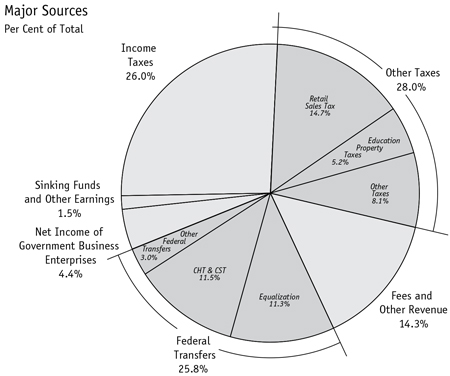

Revenue

Revenue in 2017/18 is projected to increase $626 million, or 4.0%, from the 2016/17 Budget.

Income tax revenue is projected to increase by $326 million, with a $312 million increase in individual income tax revenue and an increase of $14 million in corporation income tax revenue. Budget 2017 projects a $101 million, or 2.3%, increase in other tax revenue, mainly reflecting growth in retail sales tax and corporations taxes. Fees and other revenue is projected to increase $87 million, or 3.9%. Federal transfers are projected to increase $55 million, or 1.3%. Net income of Government Business Enterprises is projected to increase $31 million, or 4.6%. Sinking funds and other earnings is projected to increase by $26 million.

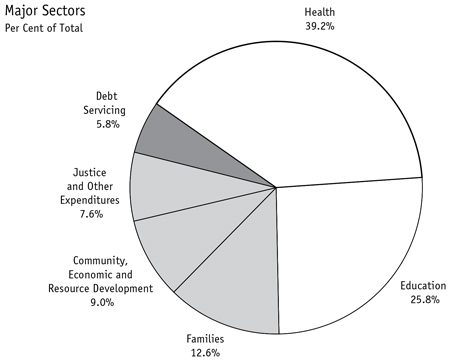

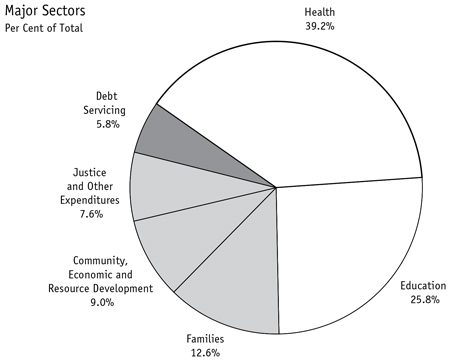

Expenditure

Expenditure in 2017/18 is projected to increase $520 million, or 3.1%, from the 2016/17 Budget.

The growth in health expenditure is $177 million, or 2.7%. Education-related expenditure is increasing by $119 million, or 2.8%. Families is up $122 million, or 6.0%. Community, economic and resource development expenditure will increase by $10 million, or 0.7%. The justice and other expenditures sector will increase by $12 million, or 0.9%. Debt servicing is expected to increase by $80 million.

4 / BUDGET 2017

Summary Revenue

For the Fiscal Year Ending March 31, 2018 (Millions of Dollars)

With Comparative Data for the Fiscal Year Ending March 31, 2017

| | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | |

| | | 2017/18 | | 2016/17 | | 2016/17 | | Per Cent Change 2017/18 Budget from 2016/17 |

| Source of Revenue | | Budget | | Forecast | | Budget | | Forecast | | Budget |

| | | | | |

Income Taxes | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | |

Individual Income Tax | | | | 3,651 | | | | | 3,498 | | | | | 3,339 | | | | | | | | | | | |

Corporation Income Tax | | | | 543 | | | | | 452 | | | | | 529 | | | | | | | | | | | |

| | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | |

Subtotal: Income Taxes | | | | 4,194 | | | | | 3,950 | | | | | 3,868 | | | | | 6.2 | | | | | 8.4 | |

| | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | |

Other Taxes | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | |

Corporations Taxes | | | | 282 | | | | | 270 | | | | | 249 | | | | | | | | | | | |

Fuel Taxes | | | | 334 | | | | | 341 | | | | | 331 | | | | | | | | | | | |

Land Transfer Tax | | | | 84 | | | | | 83 | | | | | 84 | | | | | | | | | | | |

Levy for Health and Education | | | | 342 | | | | | 340 | | | | | 345 | | | | | | | | | | | |

Retail Sales Tax | | | | 2,360 | | | | | 2,298 | | | | | 2,328 | | | | | | | | | | | |

Tobacco Tax | | | | 249 | | | | | 251 | | | | | 256 | | | | | | | | | | | |

Other Taxes | | | | 11 | | | | | 13 | | | | | 10 | | | | | | | | | | | |

Education Property Taxes | | | | 835 | | | | | 799 | | | | | 793 | | | | | | | | | | | |

| | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | |

Subtotal: Other Taxes | | | | 4,497 | | | | | 4,395 | | | | | 4,396 | | | | | 2.3 | | | | | 2.3 | |

| | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | |

Fees and Other Revenue | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | |

Fines and Costs and Other Legal | | | | 54 | | | | | 58 | | | | | 54 | | | | | | | | | | | |

Minerals and Petroleum | | | | 11 | | | | | 12 | | | | | 10 | | | | | | | | | | | |

Automobile and Motor Carrier Licences and Fees | | | | 154 | | | | | 153 | | | | | 152 | | | | | | | | | | | |

Parks: Forestry and Other Conservation | | | | 34 | | | | | 36 | | | | | 34 | | | | | | | | | | | |

Water Power Rentals | | | | 111 | | | | | 114 | | | | | 108 | | | | | | | | | | | |

Service Fees and Other Miscellaneous Charges | | | | 1,636 | | | | | 1,635 | | | | | 1,572 | | | | | | | | | | | |

Tuition Fees | | | | 307 | | | | | 299 | | | | | 290 | | | | | | | | | | | |

| | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | |

Subtotal: Fees and Other Revenue | | | | 2,307 | | | | | 2,307 | | | | | 2,220 | | | | | – | | | | | 3.9 | |

| | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | |

Federal Transfers | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | |

Equalization | | | | 1,820 | | | | | 1,736 | | | | | 1,736 | | | | | | | | | | | |

Canada Health Transfer (CHT) | | | | 1,355 | | | | | 1,313 | | | | | 1,304 | | | | | | | | | | | |

Canada Social Transfer (CST) | | | | 502 | | | | | 485 | | | | | 482 | | | | | | | | | | | |

Shared Cost and Other Transfers | | | | 486 | | | | | 583 | | | | | 586 | | | | | | | | | | | |

| | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | |

Subtotal: Federal Transfers | | | | 4,163 | | | | | 4,117 | | | | | 4,108 | | | | | 1.1 | | | | | 1.3 | |

| | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | |

Net Income of Government | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | |

Business Enterprises (GBEs) | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | |

Manitoba Liquor and Lotteries Corporation | | | | 592 | | | | | 580 | | | | | 586 | | | | | | | | | | | |

Deposit Guarantee Corporation | | | | 20 | | | | | 18 | | | | | 18 | | | | | | | | | | | |

Manitoba Hydro-Electric Board1 | | | | 74 | | | | | 50 | | | | | 42 | | | | | | | | | | | |

Workers Compensation Board | | | | 7 | | | | | 24 | | | | | 9 | | | | | | | | | | | |

Manitoba Public Insurance Corporation | | | | 12 | | | | | (28) | | | | | 19 | | | | | | | | | | | |

| | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | |

Subtotal: Net Income of GBEs | | | | 705 | | | | | 644 | | | | | 674 | | | | | 9.5 | | | | | 4.6 | |

| | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | |

Sinking Funds and Other Earnings | | | | 235 | | | | | 230 | | | | | 209 | | | | | 2.2 | | | | | 12.4 | |

| | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | |

Total Revenue | | | | 16,101 | | | | | 15,643 | | | | | 15,475 | | | | | 2.9 | | | | | 4.0 | |

| | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | |

1 Budget figures as per Integrated Financial Forecast (IFF15)

BUDGET 2017 / 5

Summary Expenditure

For the Fiscal Year Ending March 31, 2018 (Millions of Dollars)

With Comparative Data for the Fiscal Year Ending March 31, 2017

| | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | |

| | | 2017/18 | | 2016/17 | | 2016/17 | | Per Cent Change 2017/18 Budget from 2016/17 |

| Sector/Department | | Budget | | Forecast | | Budget | | Forecast | | Budget |

| | | | | |

Health | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | |

| | | | | |

Health, Seniors and Active Living | | | | 6,681 | | | | | 6,475 | | | | | 6,504 | | | | | 3.2 | | | | | 2.7 | |

| | | | | |

Education | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | |

| | | | | |

Education and Training | | | | 4,400 | | | | | 4,284 | | | | | 4,281 | | | | | 2.7 | | | | | 2.8 | |

| | | | | |

Families | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | |

| | | | | |

Families | | | | 2,159 | | | | | 2,037 | | | | | 2,037 | | | | | 6.0 | | | | | 6.0 | |

| | | | | |

Community, Economic and Resource Development | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | |

| | | | | |

Agriculture | | | | 394 | | | | | 289 | | | | | 381 | | | | | | | | | | | |

| | | | | |

Growth, Enterprise and Trade | | | | 114 | | | | | 137 | | | | | 130 | | | | | | | | | | | |

| | | | | |

Indigenous and Municipal Relations | | | | 451 | | | | | 516 | | | | | 458 | | | | | | | | | | | |

| | | | | |

Infrastructure | | | | 430 | | | | | 428 | | | | | 409 | | | | | | | | | | | |

| | | | | |

Sustainable Development | | | | 142 | | | | | 141 | | | | | 143 | | | | | | | | | | | |

| | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | |

| | | | | |

Subtotal: Community, Economic and Resource Development | | | | 1,531 | | | | | 1,511 | | | | | 1,521 | | | | | 1.3 | | | | | 0.7 | |

| | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | |

| | | | | |

Justice and Other Expenditures | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | |

| | | | | |

Legislative Assembly | | | | 47 | | | | | 57 | | | | | 58 | | | | | | | | | | | |

| | | | | |

Executive Council | | | | 3 | | | | | 3 | | | | | 3 | | | | | | | | | | | |

| | | | | |

Civil Service Commission | | | | 21 | | | | | 21 | | | | | 21 | | | | | | | | | | | |

| | | | | |

Employee Pensions and Other Costs | | | | 77 | | | | | 77 | | | | | 77 | | | | | | | | | | | |

| | | | | |

Finance | | | | 352 | | | | | 345 | | | | | 346 | | | | | | | | | | | |

| | | | | |

Justice | | | | 615 | | | | | 602 | | | | | 604 | | | | | | | | | | | |

| | | | | |

Sport, Culture and Heritage | | | | 82 | | | | | 78 | | | | | 83 | | | | | | | | | | | |

| | | | | |

Enabling Appropriations | | | | 40 | | | | | 30 | | | | | 33 | | | | | | | | | | | |

| | | | | |

Other Appropriations | | | | 57 | | | | | 57 | | | | | 57 | | | | | | | | | | | |

| | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | |

| | | | | |

Subtotal: Justice and Other Expenditures | | | | 1,294 | | | | | 1,270 | | | | | 1,282 | | | | | 1.9 | | | | | 0.9 | |

| | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | |

| | | | | |

Debt Servicing | | | | 991 | | | | | 938 | | | | | 911 | | | | | 5.7 | | | | | 8.8 | |

| | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | |

| | | | | |

Total Expenditure | | | | 17,056 | | | | | 16,515 | | | | | 16,536 | | | | | 3.3 | | | | | 3.1 | |

| | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | |

6 / BUDGET 2017

Revenue, 2017/18

Expenditure, 2017/18

FISCAL RESPONSIBILITY STRATEGY 2017/18:

THE ROAD TO RECOVERY

FISCAL RESPONSIBILITY STRATEGY 2017/18: THE ROAD TO RECOVERY

| | | | |

| CONTENTS | | | | |

| |

WHERE WE ARE TODAY | | | 9 | |

| |

WHAT WE HEARD: YOUR PROVINCE – YOUR PLAN | | | 9 | |

| |

EXPERT REVIEWS | | | 11 | |

| |

WHAT WE LEARNED | | | 11 | |

| |

RESTORING FISCAL DISCIPLINE | | | 12 | |

| |

ALL HANDS ON DECK | | | 15 | |

| |

THE PATH FORWARD | | | 16 | |

| |

REBUILDING THE ECONOMY | | | 19 | |

| |

CLIMATE AND GREEN PLAN | | | 21 | |

| |

PARTNERSHIPS | | | 21 | |

| |

APPENDICES | | | | |

| |

Appendix 1: Fiscal Performance Review | | | 23 | |

| |

Appendix 2: Clinical and Preventive Services Planning for Manitoba | | | 29 | |

| |

Appendix 3: Factors Affecting Emergency Department Waiting Room Times in Winnipeg | | | 33 | |

| |

Appendix 4: Health System Sustainability and Innovation Review | | | 35 | |

BUDGET 2017 / 9

As our government proceeds into year two of our mandate, we continue on the path to making Manitoba the most improved province in Canada: from better health care and education for Manitoba families; to better jobs that will inspire our young people to make Manitoba their home into the future; led by an open government that earns the trust of Manitobans. Our road to recovery is based on the foundation of a strong fiscal plan to make this process possible.

WHERE WE ARE TODAY

Our first year has been spent listening to Manitobans who came forward during our pre-budget consultation to give us their views on how to repair our services, fix Manitoba’s finances and rebuild our economy. We received advice from Manitobans from all walks of life and from all across the province, small business people and provincial civil servants, front-line service providers and farmers. We sought expert advice on how to improve the performance of our government, with particular focus in the short term to improving our health care services. From that advice we have developed Budget 2017 and a longer-term strategy to improve services to give Manitobans better value for their hard-earned tax dollars.

Further work is underway on other services, including a strategy to improve services for children in care that will build on our initial legislative reforms to enhance information sharing between the agencies helping children in need of protection and support. We have begun to explore ways to improve our justice system, and are developing a strategy to provide more child care spaces for Manitoba families. Reviews are underway on how best to encourage more private sector investment to strengthen our economy.

WHAT WE HEARD: YOUR PROVINCE – YOUR PLAN

We strongly believe that Manitoba citizens have valuable insight and advice to offer as we move forward in our mandate. This is why we undertook the most

extensive pre-budget consultation that Manitobans have ever seen, offering opportunities in person, in written communication and through social media in order to reach out as extensively as possible to all corners of our province.

Launched in October of 2016, our pre-budget consultations engaged Manitobans from across the province. Community meetings, hosted by the Minister of Finance, were held in Winnipeg, Brandon, Swan River and Thompson, with approximately 340 individuals and almost 50 stakeholders participating.

In addition, over 220 citizens provided advice and ideas online in the areas of efficiency, regulatory reform, managing the province’s expenditure growth, supporting economic growth and specifically, private sector growth in Manitoba’s North. Over 100 Manitobans chose to write or e-mail the Minister of Finance directly with their priorities. Over 300 civil servants from across Manitoba provided advice through an internal website.

In all, our consultations included over 18,000 interactions with Manitobans who provided extensive and important feedback and input on priorities for Budget 2017.

The ideas brought forward were valuable, important and much appreciated as we collectively work towards fixing our finances and rebuilding our economy.

10 / BUDGET 2017

Manitoba was the first province to employ an interactive online tool that allowed Manitobans to build their own provincial budget based on their priorities.

At the same time, they were able to see how those decisions impact Manitoba’s 2016/17 budgeted core deficit of $890 million. This tool allowed Manitobans to experience firsthand the development of a provincial budget and to better understand the challenges as we strive to fix our finances.

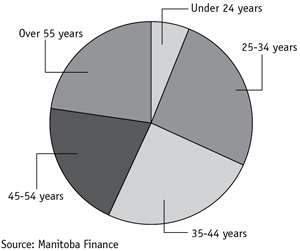

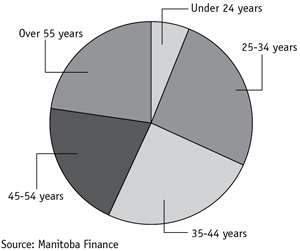

Almost 1,000 Manitobans built their own provincial budget. The input came from a broad spectrum of Manitobans from all regions of the province, including urban, rural and northern, home owners and renters, 90% of whom have resided in Manitoba for more than 10 years, and representing all age groups.

Manitoba’s Citizen Budget Participants

What we heard from Manitobans was that sustainability and ensuring programs and services are delivered in the most efficient way possible is fundamental to good governance. The following themes emerged:

These themes were echoed by the Advisory Panel on Fiscal Performance, which participated in the budget deliberations and offered their advice to the Minister of Finance based on the feedback of Manitobans and the expert panel reviews.

Budget 2017 reflects the consideration of the advice we have received over the last several months. Manitobans have a right to expect that their government uses public revenues effectively and efficiently to deliver high-quality government programs and services at a reasonable and sustainable cost, and this is what we heard when we consulted our citizens.

BUDGET 2017 / 11

EXPERT REVIEWS

Several major reviews by external experts have helped us as we prepared Budget 2017 and developed our long-term plans for repairing our services and making progress towards a balanced future.

Firstly, we conducted a comprehensive Fiscal Performance Review of our core government departments, excluding the health sector. Secondly, we received two important reports on our health care services, the Provincial Clinical and Preventive Services Planning for Manitoba: Doing Things Differently and Better (the ‘Peachey Report’), and Factors Affecting Emergency Department Waiting Room Times in Winnipeg, by the Manitoba Centre for Health Policy. A third and complementary review – the Health System Sustainability and Innovation Review – focused on assessing the current state of our health care services, and recommended a pathway towards improving the quality and sustainability of our health care system. Appendices 1 to 4 provides further details regarding the findings of these reports.

WHAT WE LEARNED

Our first year was also spent learning and understanding the full extent of the fiscal challenges inherited from the previous government.

Throughout our first year, we have learned that the challenges we inherited are significant and include:

| ● | | the level of regional health authority deficit spending: history of running deficits including almost $60 million in 2015/16; |

| ● | | the East Side Road Authority commitments, which totaled over $200 million; |

| ● | | depletion of the Fiscal Stabilization Account leaving the current balance of $115 million, the lowest balance of the account in 14 years; |

| ● | | lengthy lease commitments, long-term collective bargaining agreements, complex job descriptions and bargaining units, all challenging the government’s ability to improve front-line services; |

| ● | | neglected upgrades for the Fleetnet emergency communications service used by first responders, resulting in an estimated $400 million replacement price tag; |

| ● | | amortization, principal and interest payments, the cost of servicing debt on capital assets, rising by almost $60 million annually; and |

| ● | | deferred maintenance liability of over $8 billion in core government infrastructure alone, as a result of failing to properly maintain owned assets. |

These examples of fiscal mismanagement contributed to Manitoba’s 2015/16 level of expenditures to Gross Domestic Product (GDP) of 24%, significantly higher than other western provinces. In Budget 2015, the last tabled budget of the previous government, the financial deficit projection was $422 million on a summary basis while the actual deficit came in at $846 million, more than double their projection. This enormous increase in the deficit came despite Budget 2014’s projection that the deficit would be eliminated by 2016.

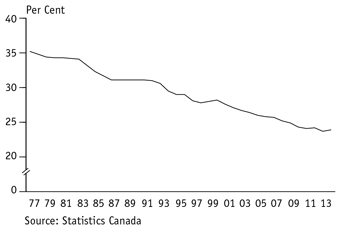

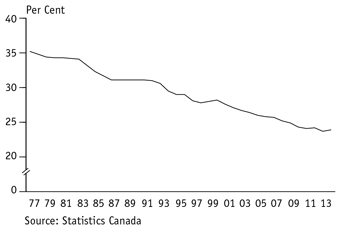

From 2005/06 to 2015/16, core government revenues grew at a reasonable and predictable pace, averaging 3.8%. Expenditures on the other hand, grew at 4.7%, outstripping the revenue growth. It is clear that these annual deficits were not the result of a revenue problem – the previous government had a chronic spending problem.

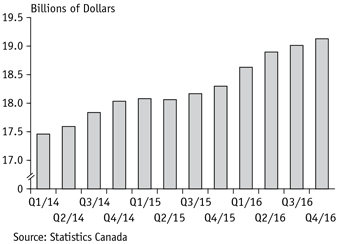

Running deficits has resulted in a very serious issue for our province’s net debt position, which more than doubled since 2007/08 to $21.4 billion in 2015/16, and is a key factor in recent downgrades from credit rating agencies.

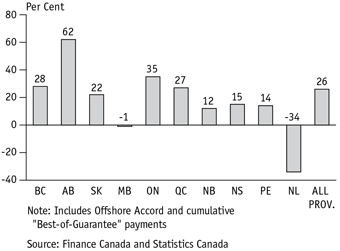

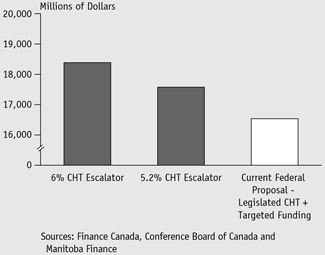

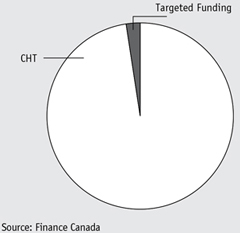

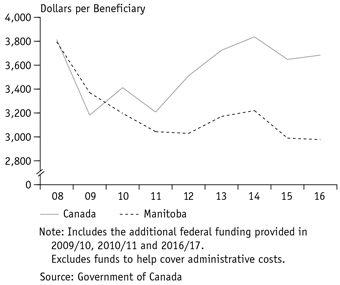

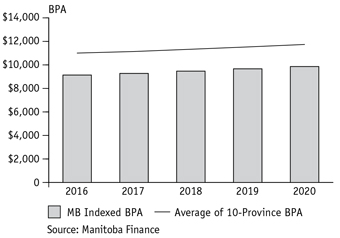

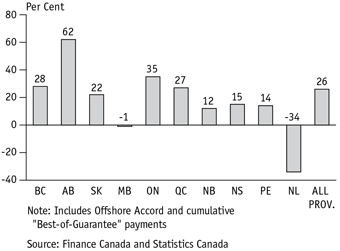

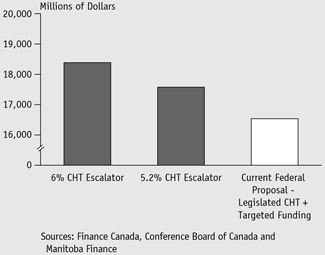

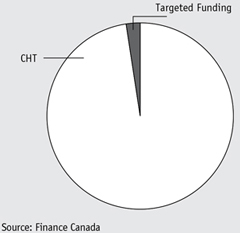

It is clear that Manitoba’s fiscal situation will not fix itself. In addition to these liabilities, our government faces upcoming challenges, notably the reduction of the level of federal transfers for health care. This unilateral announcement applies a further pressure of $39 million on provincial revenues, despite numerous expert studies warning of the oncoming demographic challenges to the health care system.

12 / BUDGET 2017

But we are making progress. Budget 2016, introduced four weeks after the swearing in of our government, is on track: based on the third quarter of the fiscal year 2016/17, we are projecting a deficit of $872 million, $39 million better than the budgeted deficit of $911 million.

RESTORING FISCAL DISCIPLINE

Our government will continue working to restore fiscal discipline with a common sense approach to financial management. We will work to implement the input from Manitobans and the recommendations of our expert reviews to eliminate waste and duplication, and ensure that we deliver value for taxpayers’ hard-earned money.

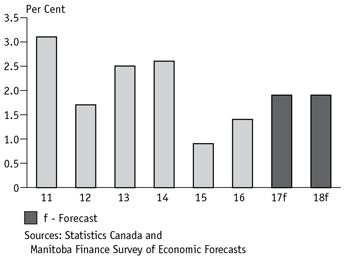

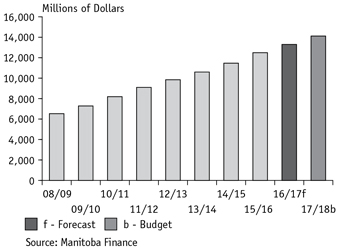

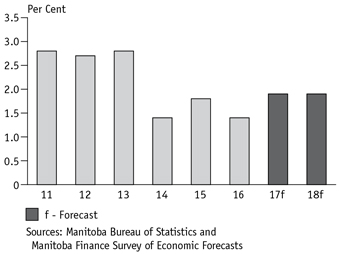

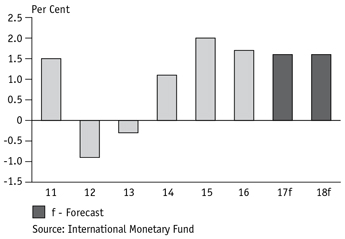

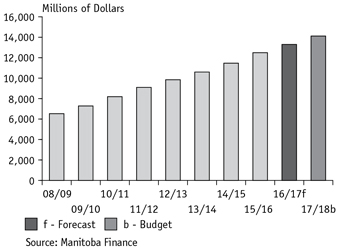

Manitoba’s Budget Projections

Open and transparent financial reporting means that financial management plans, actions and results should be clearly described and readily available to the public.

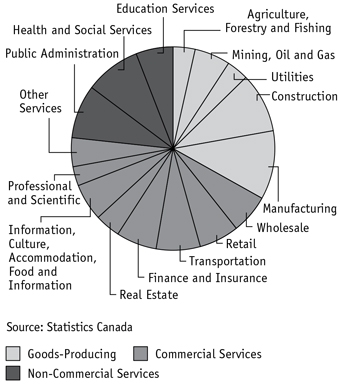

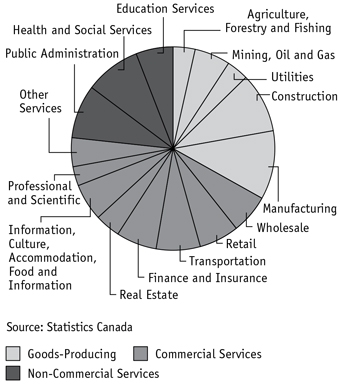

Summary budget reporting and core government reporting are both important to provide transparency and accountability with respect to the province’s financial management. The Summary Budget brings together the results for not just core government, but also all of the government business enterprises (GBEs) such as Manitoba Hydro and Manitoba Public Insurance, the health authorities, the social service authorities, school divisions, and many more entities either

controlled or financially dependent on the provincial government. As such, it provides an important overview of the financial position of the provincial public sector as a whole.

The core government projections provide information on the revenues and expenses of government departments that are under the direct control of the Legislative Assembly. These are where the day-to-day decisions are made that ultimately determine the success of the government’s strategies, plans and programs.

Manitoba now has the basic elements in place to ensure transparency, including summary financial statements that are compliant with Canadian Public Sector Accounting Standards, as well as quarterly financial reporting on the same summary basis.

Open and transparent financial reporting increases accountability and ultimately fosters the fiscal discipline needed to bend the cost curve in government spending to restore budget balance.

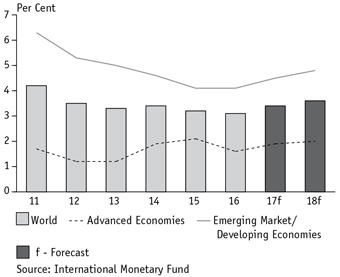

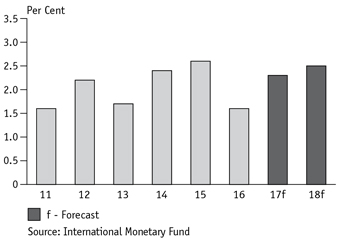

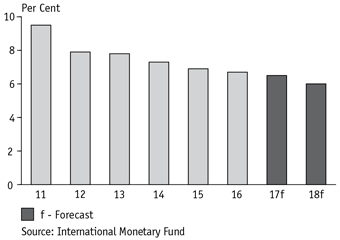

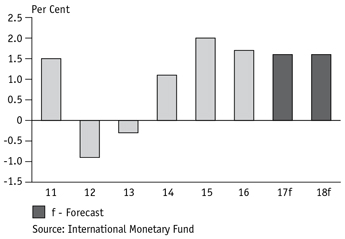

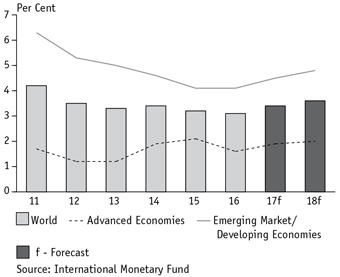

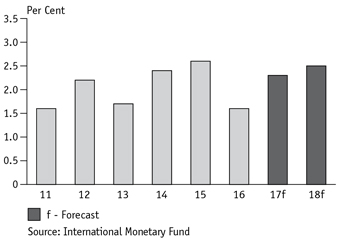

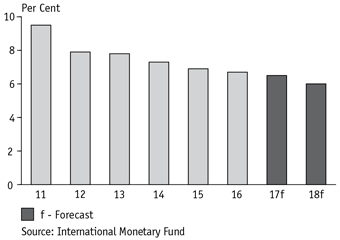

Although several risks and challenges remain for the global economy, Manitoba’s stable economic and demographic fundamentals are projected to produce steady economic growth over the next year.

Both summary and core government budget projections assume revenue will rise by an average of 3% annually from 2017/18 to 2019/20. We have taken measures to control expenditures, which are now projected to increase by an annual average of 2% during the same period.

Summary Budget

| | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | |

| (Millions of Dollars) | | 2016/17

Budget | | | 2016/17

Forecast | | | 2017/18

Budget | | | 2018/19

Projection | | | 2019/20

Projection | |

| | | | | |

Revenue | | | 15,475 | | | | 15,643 | | | | 16,101 | | | | 16,584 | | | | 17,081 | |

| | | | | |

Expenditure | | | 16,536 | | | | 16,515 | | | | 17,056 | | | | 17,397 | | | | 17,745 | |

| | | | | |

Year-End Adjustments/Lapse | | | (150) | | | | - | | | | (115) | | | | (115) | | | | (115) | |

| | | | | |

Net Income (Loss) | | | (911) | | | | (872) | | | | (840) | | | | (698) | | | | (549) | |

| | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | |

BUDGET 2017 / 13

Core Government

| | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | |

| (Millions of Dollars) | | 2016/17

Budget | | | 2016/17

Forecast | | | 2017/18

Budget | | | 2018/19

Projection | | | 2019/20

Projection | |

| | | | | |

Revenue | | | 12,578 | | | | 12,663 | | | | 13,016 | | | | 13,406 | | | | 13,808 | |

| | | | | |

Expenditure | | | 13,538 | | | | 13,463 | | | | 13,820 | | | | 14,096 | | | | 14,378 | |

| | | | | |

Year-End Adjustments/Lapse | | | (70) | | | | - | | | | (35) | | | | (35) | | | | (35) | |

| | | | | |

Net Result | | | (890) | | | | (800) | | | | (769) | | | | (655) | | | | (535) | |

| | | | | |

Fiscal Stabilization Account Transfer | | | - | | | | - | | | | (10) | | | | (50) | | | | (50) | |

| | | | | |

Net Income (Loss) | | | (890) | | | | (800) | | | | (779) | | | | (705) | | | | (585) | |

| | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | |

Beginning in 2017/18, transfers to the Fiscal Stabilization Account will begin to rebuild the province’s savings, providing protection for core government operations in future years.

Budget 2017 fiscal projections are based on the latest available economic projections. The current Manitoba Finance Survey of Economic Forecasts from March 2017 shows Manitoba’s nominal GDP - the broadest measure of the tax base - to increase by 3.6% in 2017 and by 3.8% annual average growth over the next two years.

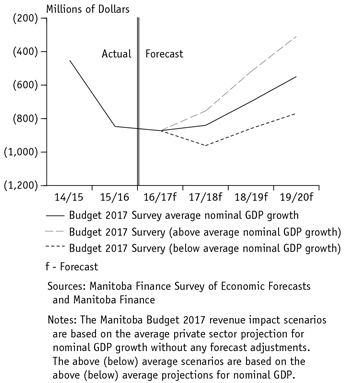

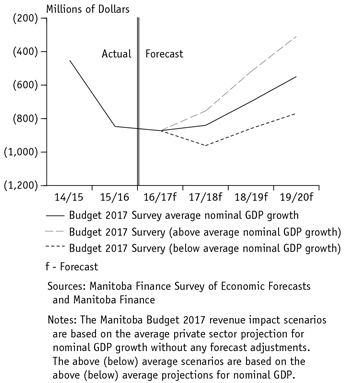

Given the uncertainty in the economic environment, risks and revisions to the economic forecast can materially impact provincial revenue projections and thereby impact the projected budget surplus/deficit position. The following chart shows fiscal outcomes under two additional revenue growth scenarios compared to the base case. The above average nominal GDP growth scenario uses forecasts that are above the survey average, while the below average scenario uses the forecasts that are below the survey average.

Manitoba continues to face significant fiscal challenges on the road to recovery. We know that this recovery will take time, and we stand behind our commitment to ensure that we get it right, and that we return to balance before the end of our second term.

Prudent budget decisions in expenditure increases and fiscal discipline throughout the coming year are imperative to ensuring that the 2017/18 budgeted deficit position is achieved. This approach will continue in future years.

Manitoba Summary Budget

Under Various Revenue Growth Scenarios

14 / BUDGET 2017

Reaffirming Our Commitment: The Fiscal

Responsibility and Taxpayer Protection Act

Bill 21, The Fiscal Responsibility and Taxpayer Protection Act re-establishes the foundation of fiscal discipline and accountability that will support a sustainable financial future for Manitoba.

The new Act will require government to show progress from the deficit base line of $924 million established on a summary basis in Budget 2017 and, as progress is made each year, the deficit must continue to be less than the year before.

However, Bill 21 also recognizes the impact that decisions of the past will continue to have on our ability to pay for the services Manitobans expect.

Manitoba Hydro has made aggressive capital investments that have led to volatile and costly projections that impact our budget on a summary basis. Any significant loss experienced by Manitoba Hydro would have to be offset by reductions to the very services and supports that our government is committed to protecting.

At the same time, because the projections are volatile, Manitoba Hydro may see positive results in some years, as these capital projects progress. It would likewise be imprudent to count on those positive earnings as an indicator of success on the road to balance, with the knowledge that Manitoba will be paying for the decisions of the past for many years to come. It is therefore the fiscally responsible approach to exclude Manitoba Hydro’s net income, whether it is positive or negative.

The new legislation will reaffirm the value of planning for the future through the use of the Fiscal Stabilization Account. It will allow government to set aside one-time revenue that is intended to pay for a service or project that will be completed and paid for in a future year and to return that revenue to the Consolidated Fund when the payment is made. This is a practical, transparent and responsible approach that ensures that when progress is made and ultimately balance is achieved, it is sustainable and not dependent on one-time revenue that cannot be maintained into the future.

The calculation of the Budget 2017 base line deficit, as determined under the new Act, is as follows:

Fiscal Responsibility and Taxpayer Protection,

Base Line Deficit

| | |

| (Millions of Dollars) | | 2017/18 Budget |

| |

Revenue | | 16,101 |

| |

Expenditure | | 17,056 |

| |

Net Result | | (955) |

| |

Year-End Adjustments/Lapse | | (115) |

| |

Net Income (Loss) | | (840) |

| |

Adjustments: | | |

| |

1) Net Income (Loss) Manitoba Hydro | | 74 |

| |

2) Fiscal Stabilization Account | | 10 |

| |

Base Line Deficit 2017/18 | | (924) |

BUDGET 2017 / 15

To ensure the accountability of members of cabinet and to reflect our principles to face difficult decisions head on and to reward performance, the new Act will require ministers to forgo 20% of their salary each year that a deficit is projected. If progress is achieved and the deficit is smaller than the previous year, then that performance is rewarded and ministers will receive the withheld salary. However, if progress is not achieved, then the salary repayment will be reduced, or even forfeited for that year, and further withheld at 40% in subsequent years, until progress towards balance is achieved.

Returning to balance will require focus, vigilance and a common sense approach, but it must not be achieved on the backs of hard-working Manitobans. The Fiscal Responsibility and Taxpayer Protection Act will provide Manitoba taxpayers with enforceable protection, including the restoration of the right to vote on major tax increases.

These measures will ensure that we stay on a financially prudent course and that all of our partners contribute to Manitoba claiming its title as the Most Improved Province.

ALL HANDS ON DECK

A common theme in both fiscal performance reviews and the clinical services review was the invaluable contribution provided by the public service and those delivering front-line services to Manitobans. Our civil service is committed to reinvigorating and contributing to the design of a more responsive and efficient government that benefits all Manitobans.

At the same time, we recognize that a significant portion of expenditures in government relate to public service compensation. If we are to work together to return our books to balance and chart a sustainable path for future generations, then we must all contribute to that goal.

Our government’s initial focus was to reduce the size of cabinet and reorganize government departments. The next step involved a more responsive and effective

management approach, to reduce a top-heavy structure initially in the civil service through streamlining and consolidation, a process that will continue across the broader public sector.

A further component of our efforts to ensure the sustainability of front-line services across the public sector is reflected in the introduction of Bills 28 and 29, companion pieces of legislation designed to protect the front-line services relied upon by Manitoba families, deliver better patient care through necessary reform and bargaining unit restructuring, and guard against tax increases. This legislation follows extensive pre-budget consultations with Manitobans and continuing dialogue with union leaders.

Bill 28, The Public Services Sustainability Act, establishes a four-year sustainability period with percentage limits on pay increases for an estimated 120,000 public servants, including employees of: the government and its agencies; health organizations including physicians; child and family service authorities and agencies; universities, colleges and school divisions; other financial reporting organizations; independent offices; the legislative assembly; and political staff.

There are currently more than 180 different bargaining units and collective agreements in the health care sector, adding administrative burdens and creating challenges to ensure integrated, quality care for patients across our province’s health care system. Bill 29, The Health Sector Bargaining Unit Review Act sets out a framework to significantly reduce the number of bargaining units and increase the flexibility necessary to improve the quality and consistency of patient care across Manitoba.

16 / BUDGET 2017

THE PATH FORWARD

Budget 2017 continues the common sense approach to review processes and programs to eliminate waste and duplication to ensure that public funding delivers value for money.

Restoring Credit Ratings

After many years of stability, Manitoba’s credit ratings have come under increasing pressure in recent years as budget deficits continue at unsustainable levels. When Budget 2015 showed that Manitoba would not return to balance in 2016 as planned, Manitoba received its first credit downgrade in almost 30 years. While many factors are considered in determining a credit rating, the one that was highlighted when Moody’s Investors Service downgraded Manitoba was the lack of control over spending growth. In 2016, Manitoba received a second downgrade, this time by Standard & Poor’s, largely as a result of Manitoba Hydro’s increasing debt burden. The threat of additional downgrades is real.

Our government acknowledges the importance of controlling spending growth as the key element in restoring fiscal discipline. As the financial forecasts indicate, our government is committed to maintaining spending growth at sustainable levels, setting the foundation for a return to balance.

Meeting Budget Targets

A key to restoring fiscal discipline is to restrain the growth of spending, bending the cost curve, to ensure that spending does not outpace revenue growth. Our government is committed to ensuring that government programs and services become more effective and efficient.

The Third Quarter Report for fiscal year 2016/17, forecasts that core government is on track to meet expenditure budget targets, which has not happened since 2002/03. This was the result of government changing the tone and working with departments to instill accountability for meeting their budgets. The focus on meeting budget targets continues in Budget 2017, to stop the chronic overspending of the

past decade. Manitobans will once again be able to place their trust in government’s financial projections.

Initiatives to support this increased emphasis on delivering better value within available resources will continue in the coming year:

| ● | | procurement of public goods will continue through smart shopping including competitive tendering of government contracts; |

| ● | | checking in on the progress made to meet the commitments outlined in the mandate letters given to government ministers when they took office; |

| ● | | keeping annual core government spending growth below 3% to reduce the deficit; |

| ● | | creating the Regulatory Accountability Secretariat to ensure that barriers to growth and productivity are continually reviewed to reduce the regulatory burden on businesses and stakeholders; |

| ● | | tabling Bill 20, The Crown Corporations Governance and Accountability Act to define the roles and responsibilities of the crown corporations and the minister responsible; |

| ● | | implementing the Fiscal Performance Review Framework and change management principles into core government department decision making processes; |

| ● | | taking initial steps in health care to ensure a sustainable system today and for future generations; and |

| ● | | continuing to engage front-line workers in all departments to find ways to deliver better results for citizens through the use of proven methodologies like Lean and Continuous Improvement. |

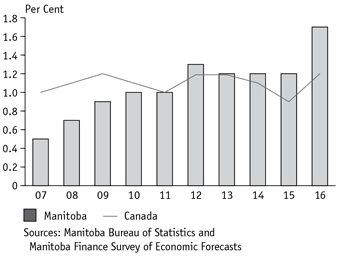

Stabilizing Net Debt to GDP

Net debt is an important indicator of a government’s financial position as this highlights how government services will remain affordable in the future. Summary net debt is made up of financial assets (such as cash or investments) minus total liabilities (such as loans or financing). It is the remaining liability that must be financed by future revenues.

The net debt to GDP ratio measures changes in net debt against the growth of the economy. A stable net debt

BUDGET 2017 / 17

to GDP ratio is a good indication that the province is managing its debt responsibly.

Some amount of public debt is necessary for the efficient delivery of required services. It is the relative size of the debt that matters. Prudent debt management means managing the size of the debt to stay within reasonable and predictable limits that reflect the ability of the provincial economy to support it. While governments run deficits, debt cannot be reduced. As outlined in Bill 21, The Fiscal Responsibility and Taxpayer Protection Act, the Manitoba government has set guidelines for reducing the deficit and will set targets for reducing the debt once balance is achieved. In order to meet this commitment, setting a sustainable level of capital investment will assist with the reduction of the debt level over time.

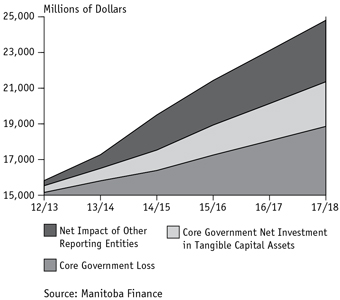

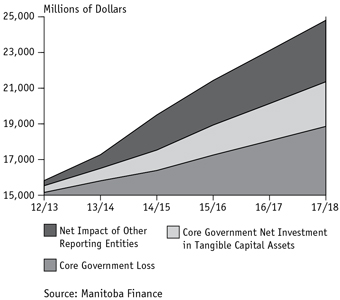

The following chart breaks out the components of the growth in the summary net debt in recent years to show the impact that core government deficits have had on the growth of the province’s net debt. Manitoba’s commitment to correct the course and move back to balance will eliminate that component of the growth curve, bringing it back down to a reasonable and sustainable level.

Summary Net Debt

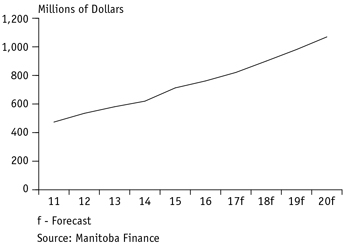

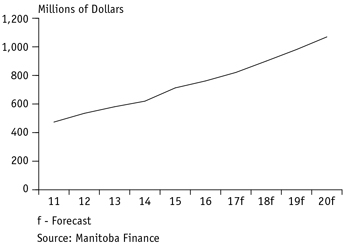

Principal, Amortization and Interest Growth

With the growth in the capital investment and debt over the last number of years, the growth in debt servicing costs has been dramatic. In 2017/18, over $900 million has been included in core government appropriations for principal, amortization and interest related to capital investment. Continued capital investment at similar levels into the future will result in unsustainable growth in capital related debt servicing costs. The resulting pressure to pay for the debt results in bigger deficits and erodes the ability to pay for front-line services. This will be compounded by potential future interest rate increases which will have an even greater impact on government’s ability to protect front-line services.

A total of $492 million has been included in core government appropriations to retire debt associated with capital investments: $270 million for amortization of department-owned assets; and $222 million for principal payments mainly for education and health-related assets.

Manitoba’s communities and the economy as a whole benefit from the debt financed net investment in tangible capital assets in both core government and other reporting entities, ranging from roads and water-control structures to health facilities, universities, colleges and schools, and parks. While the public good provided by these investments is clear, it is also evident that continued growth at the level of past investment is unsustainable.

18 / BUDGET 2017

Sustainable Investment in

Strategic Infrastructure

Investments in strategic capital stimulate the provincial economy, generate employment and increase household and business incomes. In addition, infrastructure and infrastructure renewal projects, boost productivity over the long-term, further strengthening the economy.

Our government is committed to spending at least $1 billion annually on strategic infrastructure: roads and bridges, flood protection, hospitals, schools, universities and colleges, as well as municipal projects and other infrastructure. In addition to our direct expenditures on infrastructure, we are working to

remove barriers to private investments in public infrastructure through public-private partnerships, and to maximize the cost-sharing opportunities with our federal and municipal partners.

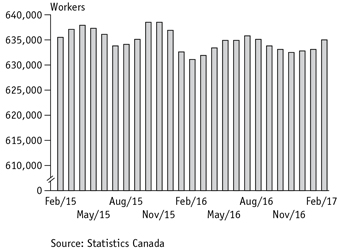

In 2017/18, the province will invest over $1.7 billion on strategic infrastructure. It is important that the investment decisions are made in the context of stimulating the economy, are for the public good, but are also financially sustainable over the long-term. With this in mind, all infrastructure investments will continue to be scrutinized to ensure the best value for money.

Strategic Infrastructure 2017/18

| | | | | | | | | | | | | | | |

| (Millions of Dollars) | | 2017/18 Budget | | 2016/17 Forecast | | 2016/17 Budget |

| | | |

Roads, Highways, Bridges and Flood Protection | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | |

| | | |

Highways Infrastructure and Airport Runway Capital | | | | 510 | | | | | 542 | | | | | 542 | |

| | | |

Maintenance and Preservation – Highways | | | | 143 | | | | | 147 | | | | | 144 | |

| | | |

Water Related Infrastructure | | | | 60 | | | | | 40 | | | | | 45 | |

| | | |

Transportation Equipment and Aircraft | | | | 19 | | | | | 15 | | | | | 17 | |

| | | |

Maintenance and Preservation – Water | | | | 15 | | | | | 15 | | | | | 15 | |

| | | |

Subtotal | | | | 747 | | | | | 759 | | | | | 763 | |

| | | |

Health, Education and Housing | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | |

| | | |

Health | | | | 358 | | | | | 364 | | | | | 442 | |

| | | |

Education | | | | 176 | | | | | 154 | | | | | 241 | |

| | | |

Housing | | | | 107 | | | | | 137 | | | | | 120 | |

| | | |

Subtotal | | | | 641 | | | | | 655 | | | | | 803 | |

| | | |

Other Provincial Infrastructure | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | |

| | | |

Municipal and Local Infrastructure | | | | 270 | | | | | 265 | | | | | 277 | |

| | | |

Public Service Buildings, Equipment and Technology | | | | 88 | | | | | 55 | | | | | 87 | |

| | | |

Parks, Cottage and Camping | | | | 12 | | | | | 8 | | | | | 12 | |

| | | |

Subtotal | | | | 370 | | | | | 328 | | | | | 376 | |

| | | |

Total Strategic Infrastructure | | | | 1,758 | | | | | 1,742 | | | | | 1,942 | |

NOTE:

| • | | The 2016/17 forecast and budget have been restated to be consistent with the 2017/18 budget presentation. |

BUDGET 2017 / 19

REBUILDING THE ECONOMY

Employment and economic growth are at the centre of our plan for a better Manitoba. A stronger economy will allow improvements in front-line services and additional investments in the programs and initiatives most important to Manitoba families, while also repairing the state of the province’s finances. Manitobans recognize that better services depend on a stronger economy, and we have taken the first steps on the road to make Manitoba a more attractive place to invest and create jobs.

Our government has a 10-point plan to grow Manitoba’s economy by increasing competitiveness, building strategic infrastructure, working with business and entrepreneurs to expand their opportunities, and promoting Manitoba as an attractive place to invest and trade. A stronger Manitoba depends on access to trading partners, and early in our mandate we took steps to join the New West Partnership Trade Agreement and improve the national Canada Free Trade Agreement to reduce barriers to interprovincial trade.

Last December, we announced the creation of our Premier’s Enterprise Team, an advisory team of top business leaders to work with us to create new jobs and economic growth in the province. This team has begun its review of the full suite of our economic development programs and agencies, to ensure we are taking the right steps to encourage investment and job creation, and will oversee the refinement of our economic development strategy.

Our government will continue to work closely with business and community leaders to create new and innovative opportunities to ensure our economy remains strong and growing. Included among the initiatives to grow the economy in 2017 are:

| ● | | enhancing export opportunities as a result of the Canada-European Union Comprehensive Economic and Trade Agreement coming into force in 2017; |

| ● | | continuing to invest no less than $1 billion annually in strategic infrastructure; |

| ● | | partnering with municipalities to provide them with a fair say on strategic infrastructure investment priorities; |

| ● | | continuing investments in tourism marketing and development through 96/4 tourism funding model; |

| ● | | Look North Strategy launched in February 2017, engaging stakeholders, communities and businesses to develop a long-term vision for economic growth and job creation in northern Manitoba; and |

| ● | | Manitoba’s Partnerships for Economic Growth program, introducing a single window funding mechanism for external economic development partners. |

Reducing Red Tape

Reducing red tape is part of our plan to grow the economy. We are committed to becoming Canada’s most improved province by reducing the burden of regulatory requirements that are poorly designed, duplicative, contradictory, anachronistic or overly prescriptive.

Manitoba recently received an “F” in the Canadian Federation of Independent Business (CFIB) 2016 Provincial Red Tape Report Card1, the lowest provincial ranking for regulatory accountability. CFIB estimates that regulation from all levels of government cost Manitoba’s small- and medium-sized businesses $1.2 billion annually in time and resources. Manitoba entrepreneurs estimate that 30% of all regulatory requirements are “red tape” and do not contribute to greater environmental quality, consumer protection or workplace safety.

In comparison with other provinces, Manitoba has no legislation and few policies regarding regulatory accountability. For example, Manitoba has no established measurement system to quantify the number of regulatory burdens or requirements being applied to stakeholders or private citizens, and there is no department with the responsibility for providing direction or training to departmental staff on effective and efficient regulation making and red tape reduction.

| 1 | http://www.cfib-fcei.ca/cfib-documents/RTAWReportCard2016_ en.pdf |

20 / BUDGET 2017

Similarly, there is neither consistent consultation policy nor a central online location that stakeholders can monitor for consultation notices or pending regulatory changes.

We are committed to providing better guidance on regulatory affairs and developing an institutional framework to promote better regulation making and accountability for regulatory decisions, which will in turn help promote more responsive decision making, and improved business development and growth through the following steps.

Our government has taken early action to reduce red tape. Once passed, Bill 24, The Red Tape Reduction and Government Efficiency Act, 2017, will eliminate 15 red tape issues and remove 749 regulatory requirements. In addition, Bill 22, The Regulatory Accountability Act and Amendments to the Statutes and Regulations Act, will minimize the administrative burden on stakeholders to comply with regulatory requirements and will promote and enhance regulatory accountability within government and government agencies.

Key elements of Bill 24 include:

| ● | | mandating the regulatory requirement baseline count, including annual reporting and updating of the baseline; |

| ● | | requiring regulatory changes to complete a regulatory impact statement (including a thorough cost-benefit analysis) and publicizing them in whole or in part if the change is adopted by government; |

| ● | | implementing a two-for-one rule (two regulations repealed for every one introduced) until fiscal year 2019/20, with a relaxation clause to one-for-one for all years proceeding from fiscal year 2020/21; |

| ● | | restricting introduction of non-emergency regulatory requirements to a set frequency; |

| ● | | establishing the Regulatory Accountability Committee of Cabinet and Regulatory Accountability Secretariat in legislation; and |

| ● | | requiring new regulations be reviewed by the Legislative Assembly of Manitoba’s Statutory Regulations and Orders Committee within three years of implementation to determine if the regulations or policies are meeting their intended purpose. |

Our new legislation will expand the mandate of the current Legislative Review Committee of Cabinet (LRC) into a Regulatory Accountability Committee. The LRC already analyzes legislation to ensure proposed regulatory requirements on stakeholders are effectively and efficiently implemented as part of their work. Expanding LRC’s mandate to include reviewing regulatory proposals will ensure consistent direction and analysis of all regulatory tools.

The new Regulatory Accountability Secretariat will bring together existing expertise within the civil service to support the cabinet committee by performing a number of tasks, including:

| ● | | reviewing existing and proposed regulations utilizing effective regulatory impact analysis techniques; |

| ● | | developing and maintaining methodology, tools and support for departments to facilitate counting regulatory requirements; |

| ● | | monitoring references to external standards in legislation and regulations to ensure all references are updated in a timely manner and adhere to interprovincial agreements; and |

| ● | | developing a central information hub for external stakeholders on consultation notices and pending regulatory changes. |

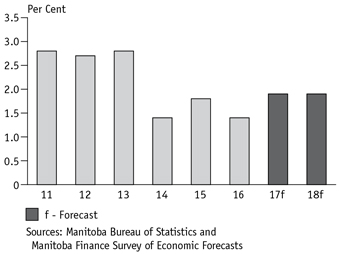

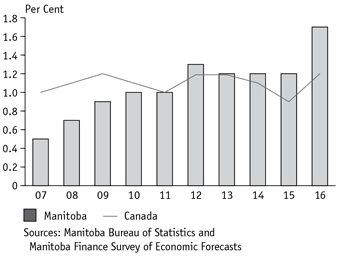

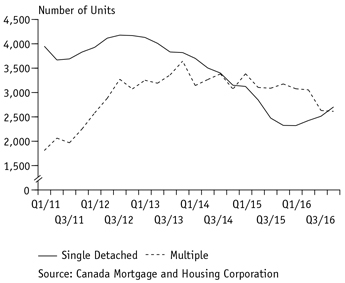

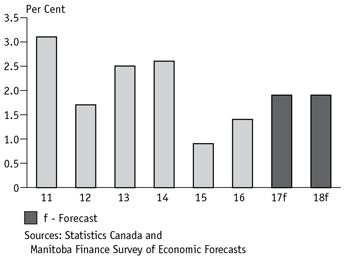

Employment Growth

Manitoba’s labour market is the most stable in Canada, with modest changes from year-to-year in annual growth rates. The province’s unemployment rate is second lowest among the provinces and the labour force participation rate is the third highest. Our steady labour market reflects the growth in the economy, with the supply of labour growing at about the same rate as the growth in jobs.

BUDGET 2017 / 21

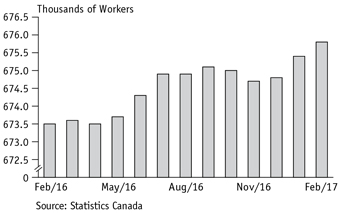

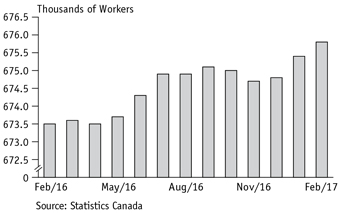

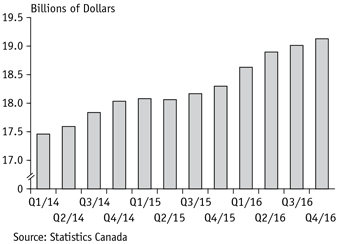

Manitoba Labour Force Trend

12-Month Moving Average

February 2016 – February 2017

Supported by population growth, the working age population in Manitoba now exceeds one million persons. Combined with the labour force participation rate at 67.2%, there is a record 675,800 workers in Manitoba’s labour market on an annual basis.

Employment increased by 6,600 jobs in the 12 months ending in February 2017. Full-time employment increased by 7,800 jobs and part-time employment fell by 1,200 jobs. Manitoba’s unemployment rate is 5.8%, compared to 6.6% in Canada.

The Manitoba Finance Survey of Economic Forecasts shows an expected 0.7% growth in employment this year and 0.8% growth in 2018, in line with the national average. The unemployment rate is expected to average 6.1% in 2017 and is anticipated to fall to 5.9% in 2018, tied for the lowest among provinces.

The encouraging signs in the economy regarding the solid gains in the labour market will provide a further boost to business and household confidence in Manitoba.

CLIMATE AND GREEN PLAN

The environment and economy go hand-in-hand. We cannot think of one without acting on the other. Sustainable development brings the environment

and economy together. It means jobs and economic opportunity for Manitobans, as well as the need to protect and preserve our natural environment and live and act sustainably.

The Manitoba government is developing a made-in-Manitoba climate and green plan founded on the principle of sustainable development. It will contain policies and priorities on climate, jobs, water and nature. It will seek to leverage our province’s clean, green foundation into an environmental and economic advantage. It will build on our clean energy investments to responsibly and realistically reduce carbon emissions while creating new low-carbon economic opportunities in our province, including carbon pricing. It will offer approaches to water and land use, sustainable agriculture, protecting wetlands, forests and natural areas, investing in green infrastructure, promoting technology and innovation, and numerous other initiatives.

We will seek the input of Manitobans on our proposed plan, to get their suggestions and ideas.

PARTNERSHIPS

Much of our time during our first year in government has been spent listening to our municipal partners. We are committed to supporting all municipalities, including Winnipeg, through a simplified approach that provides more flexibility and autonomy for local decision-making. We will develop funding envelopes that will reduce red tape while expanding “fair say” for all municipalities.

In addition, we look forward to moving towards a single window model to simplify the process for municipalities and third-party proponents to apply for cost-sharing and allow us to assess strategic investments in infrastructure and services based upon maximizing value for provincial taxpayers’ money.

We have benefited greatly from the discussions and advice from our Indigenous communities and their leaders and elders, and we will continue to work

22 / BUDGET 2017

together to move forward on important projects that have been too long delayed.

We continue to pursue concrete actions toward reconciliation with First Nations who were displaced from their homes by the catastrophic flooding of 2011. The construction of flood protection infrastructure to keep Manitobans and their communities safe remains a top priority for our government, including outlet channels that are needed to alleviate flooding around Lake Manitoba and Lake St. Martin. We look forward to meaningful engagement with those who may be affected by these projects, including regular outreach and meetings with municipalities and private landowners. We remain committed to meaningful engagement and consultations with Indigenous communities on the government’s preferred outlet channel routes and any impact that the proposed routes may have on aboriginal and treaty rights. Our

engagement will ensure that Indigenous communities have opportunities to participate in related construction work and realize economic benefits from the eventual channel projects. Manitoba is also committed to working with Shoal Lake First Nation, the Government of Canada and the City of Winnipeg to move forward with the Shoal Lake road project with the full participation of the local community.

We look forward to bringing clarity to the protocols that govern formal consultations with our Indigenous partners so we can move forward together on these and other developments that will help strengthen our economy.

Budget 2017 is our government’s second budget. We are building on our commitment to work with all Manitobans to make Manitoba better. We are on the road to recovery.

BUDGET 2017 / 23

APPENDICES

Appendix 1: Fiscal Performance Review

24 / BUDGET 2017

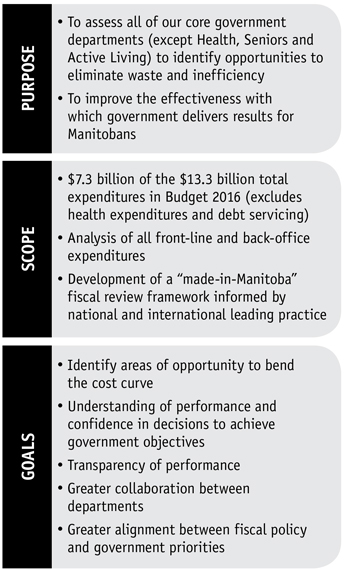

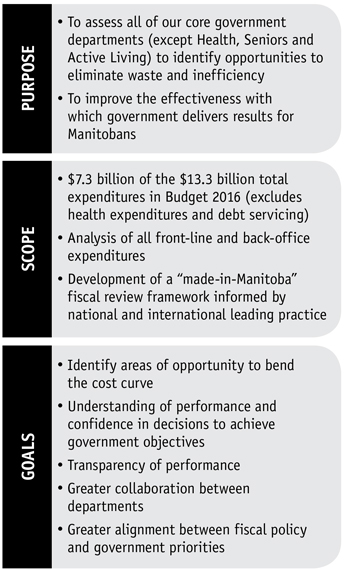

Interviews were conducted with over 140 senior government officials and included an assessment of whether there is a clear framework governing provincial expenditures, with a focus towards identifying opportunities within each of the departments to reduce the rate of growth in expenditures, both in the short term (Budget 2017) and beyond.

The observations that arose from the Fiscal Performance Review (Review) included the following:

| ● | | the Review noted the lack of performance management and measurement of outcomes/results across government; |

| ● | | a performance-based framework is required to focus on results and to ensure good value for taxpayers’ dollars; |

| ● | | over 160 specific opportunities across government were identified to bend the expenditure curve with most of these grouped into 11 key areas of opportunity; |

| ● | | opportunities should be created to promote the ongoing consideration and discussion of innovative ideas within the civil service; and |

| ● | | a concerted effort is required to improve interdepartmental collaboration. |

BUDGET 2017 / 25

The Review has provided a Fiscal Performance Review Framework (Framework) to support a fundamental change in behaviour, culture and approach to fiscal decision-making across government based on the following principles:

| | |

Results-based | | Fiscal performance should be centred on the intended outcomes to be achieved. |

Aligned | | Services and programs must be aligned to achieve the intended outcomes. |

Transparent | | The results of programs and services should be measured against the intended outcomes in a transparent and accountable manner. |

Transformative | | Changes to programs and services need to be sustained in a manner that delivers value for taxpayers. |

All

encompassing | | Barriers between departments need to be removed in recognition of the interdependence of programs and services. |

The Framework provides the public service with:

| ● | | an assessment tool to measure effectiveness, efficiency and value for money regarding government expenditures on programs and services; |

| ● | | an approach to analysis that provides options of service delivery methods or models and business cases; |

| ● | | the right questions to ask in order to align programs and policies to intended outcomes and performance measurement; and |

| ● | | guidance to apply analysis and evidence to inform policy and program choices and prioritize resources. |

This “made-in-Manitoba” Framework is informed by characteristics that ensure success based on global best practices:

|

Leadership from the Top: Cabinet Sets the Tone Clear and Open Principles |

| |

Long-Term Planning: Focus on Fiscal Sustainability Culture of Cost Efficiency and Effectiveness |

| |

Accountibility: Openness and Transparency of Information Clarity of Objectives and Results |

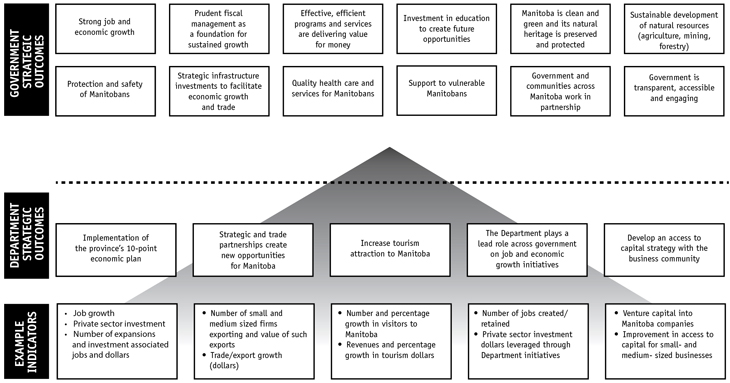

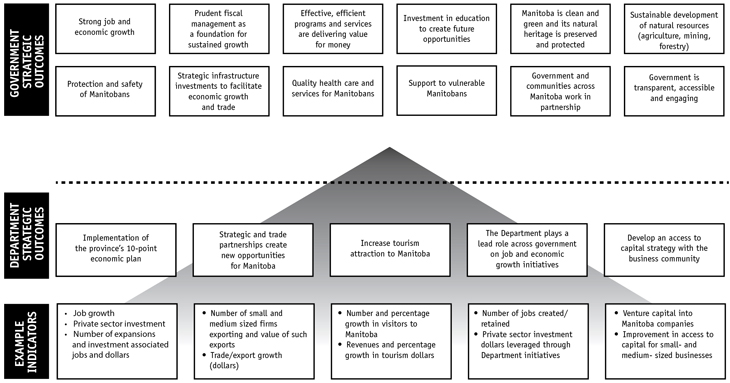

Part of a performance review framework depends on identifying government’s overall strategic outcomes and then aligning each department with those overall outcomes. Once the departmental outcomes have been established within the wider government framework, indicators of progress towards those outcomes can be identified for each outcome. A sample of this alignment, developed for Manitoba Growth, Enterprise and Trade (Department), is provided in Figure 1.

26 / BUDGET 2017

Figure 1

Implementation of the Framework requires establishing a culture of results-driven, continuous improvement, wherein decision makers apply a series of questions to programs and services to establish alignment, measurement, assessment, implementation and evaluation. The use of reliable data, information and evidence, supported by standards and tools, is key to the successful application of the Framework.

As referenced in the November 21st, 2016 Speech from the Throne, a full framework based on this advice will be developed to guide our efforts towards ensuring that Manitobans receive value for the services government provides with their hard-earned money.

Beyond the specific opportunities identified within departments, the Review also identified several larger areas of opportunity where the Manitoba government can enhance and improve the delivery of its services. Experience with other jurisdictions and knowledge of leading practices allowed the identification of a number of opportunities for Manitoba to:

| ● | | eliminate waste and duplication; |

| ● | | reduce program costs and enhance service delivery; |

| ● | | improve government operating and administrative process efficiencies; |

| ● | | enable technology to automate processes; |

| ● | | increase organizational governance and internal controls; and |

| ● | | leverage potential opportunities to increase revenues and improve customer service. |

BUDGET 2017 / 27

Eleven key areas of opportunity were identified with savings estimated at over $100 million if all recommended actions are successfully implemented:

| 1. | Rationalization of management and back- office functions resulting from departmental reorganization |

| 2. | Reduction of communications expenditures |

| 3. | Modernization of procurement across government |

| 4. | Reduction of targeted tax credits |

| 5. | Reduction of direct support programs to business |

| 6. | Asset management planning and rationalization, including real estate |

| 7. | Organizational and process transformation in Manitoba Families |

| 8. | Funding for schools and the post-secondary education sector |

| 9. | Capital project management and delivery |

| 11. | Review of agencies, boards and commissions |

Further investigation and business cases were developed for prioritized areas of opportunity. A change management approach and plan was also developed to provide guidelines to assist departments in implementation.

In Budget 2017, we have taken our first steps towards meeting the challenges and embracing the opportunities presented in this review. Significant realignment of non-performing tax credit programs, streamlining and creating single-window access to business development supports, and meeting our early commitment to streamline and reduce senior management in government is already resulting in meaningful improvements that will bend the cost curve over time and build a sustainable financial future for Manitoba.

28 / BUDGET 2017

BUDGET 2017 / 29

Appendix 2: Clinical and Preventive Services Planning for Manitoba

30 / BUDGET 2017

In January of 2017 we received the final report on Provincial Clinical and Preventive Services Planning for Manitoba: Doing Things Differently and Better2 (the ‘Peachey Report’). The overall goal of the Peachey Report was to develop a province-wide plan to improve health services and the health of Manitobans while making the health care system more sustainable.

The Peachey Report’s overall conclusions indicate that the necessary resources and capacity are present and adequate, and that there is an opportunity to reshape health care in an evidence-based and cost-effective manner that will have an overall positive effect on the health outcomes of Manitobans.

The scope of the Peachey Report is comprehensive and reflects consultations with Manitobans and health care providers. It identifies principles that should govern how clinical and preventive services should be planned, many of which mirror the principles identified in the Fiscal Performance Review:

| | |

Transparent | | All aspects of the decision-making process are easily understood or able to be explained |

Patient-centred | | Focuses on the holistic needs of the patient and family as the centre of the health care delivery system Culturally safe and culturally sensitive |

Active, robust provider engagement | | Ensures effective practitioner input |

Reflects population

needs | | Equitable across the geographic and demographic distribution of the population |

Supports access to needed services | | Incorporates local access to core services and additional access to referred services |

Enhanced

quality of care that is affordable now and sustainable in the future | | Consistent with our economic base and annual real growth Applies defined standards for acceptable, appropriate, accessible, efficient, effective and safe care |

Innovative delivery models | | Supports collaborative models of care and role optimization of health professions |

Decision-

making based on evidence | | Requires validated qualitative and quantitative evidence |

| 2 | The Provincial Clinical and Preventive Services Planning for Manitoba report was commissioned in late 2015 and conducted by Health Intelligence and Associates: David K. Peachey (Principal), Nicholas Tait, Orvill Adams and William Croson. |

BUDGET 2017 / 31

The Peachey Report reviewed 10 priority areas within our health care system and provided observations on the current state and recommendations on how care could be improved within each of the following sectors:

| ● | | Emergency medical and health services |

| ● | | Mental health and addictions |

| ● | | Public and population health |

In addition, the report reviewed the health services and unique challenges faced by Indigenous Manitobans and provided recommendations for improved service and outcomes.

The Peachey Report described the challenges of the current governance system in health and the need to clarify the respective roles of Manitoba Health, Seniors and Active Living, the regional health authorities and the service providers. It reviewed the evolution of digital health and the need to focus the investments in this sector towards the priorities identified in the clinical and preventive services plan.

Similar and complementary challenges and opportunities were also identified, and further explored in the Health System Sustainability and Innovation Review.

32 / BUDGET 2017

BUDGET 2017 / 33

Appendix 3: Factors Affecting Emergency

Department Waiting Room Times in Winnipeg3

| 3 | Factors Affecting Emergency Department Waiting Room Times in Winnipeg by Malcolm Doupe, Dan Chateau, Shelley Derksen, Ricardo Lobato de Faria, Joykrishna Sarkar, Ruth-Ann Soodeen, Scott McCulloch, and Matt Dahl. Manitoba Centre for Health Policy, University of Manitoba. 2017. |

34 / BUDGET 2017

The objectives of this report, carried out by researchers at the Manitoba Centre for Health Policy at the University of Manitoba, was to identify factors which affect wait times in the City of Winnipeg’s emergency department waiting rooms. It analyzed Emergency Department Information System (EDIS) data and the factors on which that data is provided.

The report identifies three determinants of emergency department wait time:

| ● | | Input Factors: Volume of incoming patients, which it concluded have a relatively low impact on wait times; |

| ● | | Throughput Factors: Provider supply and number/ type of diagnostic tests performed, which it found have a high impact on wait times; |

| ● | | Output Factors: Number of emergency department patients waiting to be admitted to an inpatient hospital bed and the hospital’s admission capacity, which have a medium impact on wait times. |

The report reviews factors affecting emergency department wait times with a focus on the capacity of EDIS use to provide information on the variety of factors that impact the length of an emergency department visit. The authors describe a unique approach for analyzing input, throughput and output factors differing from previous analyses in treating throughput and output separately. It concludes that by breaking out the throughput factors and seeking additional data, improvements can be made to the flow of these factors and reduce waits.

BUDGET 2017 / 35

Appendix 4: Health System Sustainability

and Innovation Review

36 / BUDGET 2017

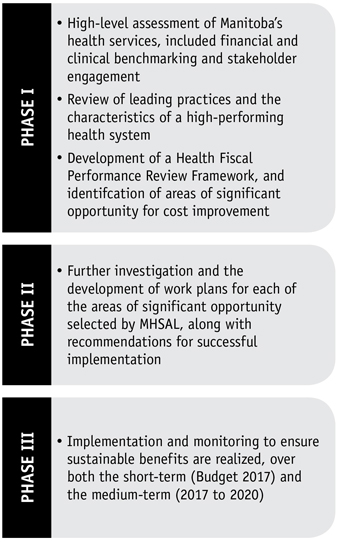

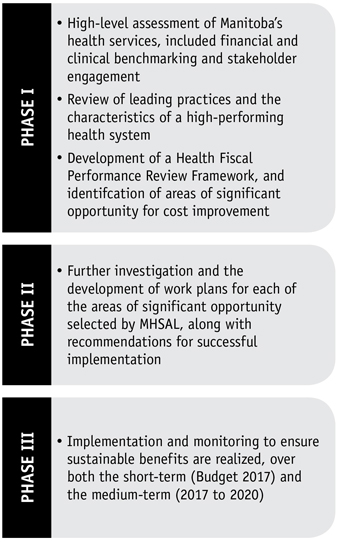

OVERVIEW OF MANDATE AND PROCESS

The independent Health System Sustainability and Innovation Review (Health Review) was undertaken to better understand how the cost curve in relation to the growth in health care funding could be bent, to improve the efficiency and effectiveness of health care services, so the health system is sustainable and supports improved health outcomes for Manitobans. The current organizational structure of the Winnipeg Regional Health Authority (WRHA) was included in the review to further support reflections on the current structure of the provincial health system, including Manitoba Health, Seniors and Active Living (MHSAL).

The in-scope spending for the review was approximately $6 billion, representing approximately 45% of the total Manitoba government budget for program expenditures. Over 300 specific cost improvement opportunities were identified in the first phase of the Health Review, in part through ideas put forward during over 70 stakeholder engagement sessions, on-line surveys of front-line service providers and research based on leading global practice. These were grouped into 11 key areas of opportunity.

To effectively measure financial performance, the following two lenses were applied:

| 1. | Allocative Efficiency: the extent to which limited funds are directed towards the right mix of health services. In other words, doing the right things. |

Measuring allocative efficiency includes assessing the services we currently invest in and identifying services that require further investment. This approach evaluates health care programs and services to identify the optimal focus and degree of investment. In health care, this also relates to the proportion of care appropriately provided in acute care settings as opposed to community and primary care settings.

| 2. | Technical Efficiency: the extent to which a health care provider is securing the minimum cost for the maximum quality. In other words, doing things the right way. |

Technical efficiency is an operational performance assessment that measures the degree to which resources are being wasted and assessing the health system’s capability to optimize those health care services already provided through various means of quality improvement.

The review was undertaken in two phases, with our government committing to undertake a third phase with our partners in the health sector.

HEALTH SYSTEM CURRENT STATE ASSESSMENT

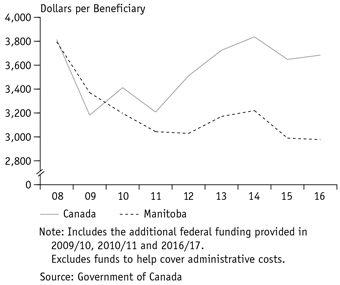

When compared against four other provincial jurisdictions4, Manitoba spent 23% more than it would have at Ontario’s per capita rate and 26% more than it

| 4 | British Columbia, Alberta, Saskatchewan and Ontario |

BUDGET 2017 / 37

would have at British Columbia’s rate. These findings are even more concerning when compared to our per capita spending in 2003, which was in line with both Ontario and British Columbia. Over the following 13 years, from 2003 to 2016, Manitoba’s health expenditures per capita increased by 72%5.

Ontario and British Columbia have been more successful in constraining cost increases by incorporating improvements from similar evaluations. However, reforms that have occurred in other provinces, such as consolidation of services, a shift to a patient-centered, commissioning-based model and funding reform have not yet occurred in Manitoba.

Other findings of the Health Review include:

| ● | | Most health care programs and services in Manitoba have not been subject to a systemic cost review in a very long time. |

| ● | | Manitoba spent more on “other institutions”, which includes personal care homes, than it would have at the per capita rates of any of the comparator provinces. |

| ● | | Manitoba spent less per capita on physicians than Ontario, Saskatchewan and Alberta. |

| ● | | Lengths of acute care stay in Manitoba are typically significantly longer than the average of their Ontario peers. |

Most notably, and notwithstanding the substantial increased spending from 2012 to 2016, Manitoba’s health services did not improve and productivity declined:

| ● | | emergency department expenses increased by 21% while total visits decreased by 2%; |

| ● | | operating room expenses increased by 8% while total visits decreased by 2%; and |

| ● | | overall hospital costs increased by 15% while patient days decreased by 1%, representing an increase in cost per patient day of 17%. |

| 5 | National Health Expenditure Trends 1975-2016 (Health System Sustainability and Innovation Review: Phase 1 Report). |

FUTURE STATE:

OPPORTUNITIES FOR IMPROVEMENT

The second phase of the Health Review focused on the development of work plans for seven prioritized areas of opportunity for cost and service improvement:

Opportunity #1

| | | | |

Strategic system realignment | | Realign and focus the roles and responsibilities between the MHSAL, the regional health authorities and facilities. | | |

| | |

| | Establish province-wide programs with consistent service standards, codes of practice, standard work and consistent measurement frameworks. | | |

FINDINGS

| ● | | There is currently no comprehensive framework in place across the health care system that codifies the mandates, accountabilities and roles of MHSAL, health authorities or providers. |

| ● | | The organizational structures of the health care system are complex for a province of our size, leading to misalignment and duplication of roles and functions across eight health authorities, five regional health authorities and multiple provider boards. |

| ● | | The structure of the Regional Health Authority Act, current operating agreements and service delivery frameworks/practices codify independence and autonomy of regions and sites instead of encouraging performance as part of a province-wide system, including poorly defined performance metrics and service expectations. |

| ● | | Alignment of planning, core service delivery and clinical delivery programs is required to improve |

38 / BUDGET 2017

| | effectiveness and resource utilization, but many health leaders are concerned about further centralization because of a bias to local delivery and/or because of their experience with poor centralized execution. |

Opportunities #2 and #3

| | | | |

| | |

Funding for performance | | Establish commissioning and performance-based funding model along with expenditure management programs | | |

| | |

Infrastructure rationalization | | Develop long-term infrastructure strategy aligned with health care priorities | | |

FINDINGS

| ● | | Funding for health care programs and services remains largely based on historic global budgets not linked to population need and with limited incentives to improve quality and efficiency. |

| ● | | The structure of current operating agreements and service delivery frameworks encourage independence and autonomy of regions and sites instead of encouraging performance as part of a province-wide system. |

| ● | | Funding conditions are not consistently defined between funding authorities to achieve a co-ordinated set of outcomes. Moreover, the funding model incorporates direct and indirect funding support to many organizations thereby impeding delivery capability and prevents meaningful transformation activity. |

Opportunities #4 and #5

| | | | |

| | |

Insured benefits and funded health programs | | Benefits and funded programs should be in alignment with Canadian standards | | |

| | |

Core clinical and health care services | | Shift from acute care to community care, review procurement and transportation program reduce variability of care and length of stay | | |

FINDINGS

| ● | | The planning and development of health care services, including the development of facilities, has not been based on a provincial clinical services plan and evidence-based care, resulting in suboptimal development and use of clinical facilities. |

| ● | | Manitoba’s health care system is centred around acute care delivery and provider centred care, which restricts the development of alternate delivery models that emphasize community or preventative care or strategies. This limits opportunities to pursue integrated delivery with alternate cost structures. |

BUDGET 2017 / 39

Opportunity #6

| | |

| |

Integrated shared services | | Identify functions that can be delivered better under a shared service model, including consolidation of health supports and administrative services |

| |

| | Align community level delivery with advanced facilities and sites |

FINDINGS

| ● | | While some corporate functions such as shared services in finance, human resources and laundry have been consolidated at the WRHA level, other functions remain dispersed across WRHA sites. |

Opportunity #7

| | | | |

| | |