Exhibit 99.1

SUMMARY BUDGET 2018/19

Summary Budget

For the Fiscal Year Ending March 31, 2019 (Millions of Dollars)

With Comparative Data for the Fiscal Year Ending March 31, 2018

| | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | |

| | | | | | | | | Per Cent Change |

| | | | | | | | | 2018/19 Budget |

| | | 2018/19 | | 2017/18 | | 2017/18 | | from 2017/18 |

| | | Budget | | Forecast | | Budget | | Forecast | | Budget |

| | | | | |

Revenue | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | |

| | | | | |

Income Taxes | | | 4,041 | | | | 3,940 | | | | 4,194 | | | | 2.6 | | | | (3.6 | ) |

| | | | | |

Other Taxes | | | 4,800 | | | | 4,620 | | | | 4,497 | | | | 3.9 | | | | 6.7 | |

| | | | | |

Fees and Other Revenue | | | 2,333 | | | | 2,363 | | | | 2,307 | | | | (1.3 | ) | | | 1.1 | |

| | | | | |

Federal Transfers | | | 4,496 | | | | 4,195 | | | | 4,163 | | | | 7.2 | | | | 8.0 | |

| | | | | |

Net Income of Government Business Enterprises | | | 842 | | | | 758 | | | | 705 | | | | 11.1 | | | | 19.4 | |

| | | | | |

Sinking Funds and Other Earnings | | | 275 | | | | 252 | | | | 235 | | | | 9.1 | | | | 17.0 | |

| | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | |

| | | | | |

Total Revenue | | | 16,787 | | | | 16,128 | | | | 16,101 | | | | 4.1 | | | | 4.3 | |

| | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | |

| | | | | |

Expenditure | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | |

| | | | | |

Health | | | 6,751 | | | | 6,633 | | | | 6,681 | | | | 1.8 | | | | 1.0 | |

| | | | | |

Education | | | 4,453 | | | | 4,405 | | | | 4,410 | | | | 1.1 | | | | 1.0 | |

| | | | | |

Families | | | 2,144 | | | | 2,128 | | | | 2,131 | | | | 0.8 | | | | 0.6 | |

| | | | | |

Community, Economic and Resource Development | | | 1,441 | | | | 1,275 | | | | 1,473 | | | | 13.0 | | | | (2.2 | ) |

| | | | | |

Justice and Other Expenditures | | | 1,600 | | | | 1,399 | | | | 1,370 | | | | 14.4 | | | | 16.8 | |

| | | | | |

Debt Servicing | | | 1,034 | | | | 964 | | | | 991 | | | | 7.3 | | | | 4.3 | |

| | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | |

| | | | | |

Total Expenditure | | | 17,423 | | | | 16,804 | | | | 17,056 | | | | 3.7 | | | | 2.2 | |

| | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | |

| | | | | |

Contingency for Writedown | | | – | | | | 50 | | | | – | | | | | | | | | |

| | | | | |

In-Year Adjustments/Lapse | | | (115 | ) | | | – | | | | (115 | ) | | | | | | | | |

| | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | |

| | | | | |

Net Income (Loss) | | | (521 | ) | | | (726 | ) | | | (840 | ) | | | | | | | | |

| | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | |

NOTES:

| • | | The 2017/18 forecast and budget have been restated to be consistent with the 2018/19 budget presentation. |

| • | | In-Year Adjustments/Lapse could be an increase in revenue and/or decrease in expenditures. |

| • | | Numbers may not add due to rounding. |

SUMMARY BUDGET 2018/19

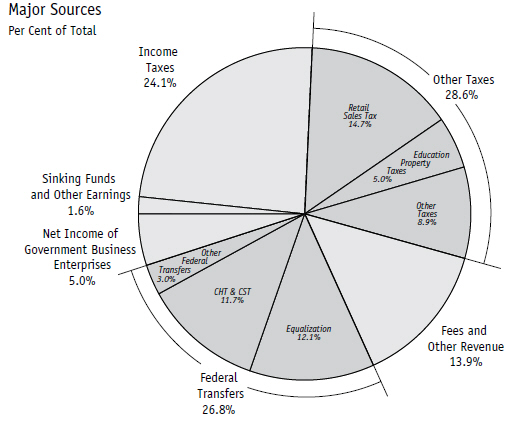

Revenue

Revenue in 2018/19 is projected to increase $686 million, or 4.3%, from the 2017/18 Budget. Income tax revenue is projected to decrease by $153 million, with a $176 million decrease in individual income tax revenue and an increase of $23 million in corporation income tax revenue. Budget 2018 projects a $303 million, or 6.7%, increase in other tax revenue, mainly reflecting growth in retail sales tax and the new carbon tax. Fees and other revenue is projected to increase $26 million, or 1.1%. Federal transfers are projected to increase $333 million, or 8.0%. Net income of Government Business Enterprises is projected to increase $137 million and sinking funds and other earnings is projected to increase by $40 million.

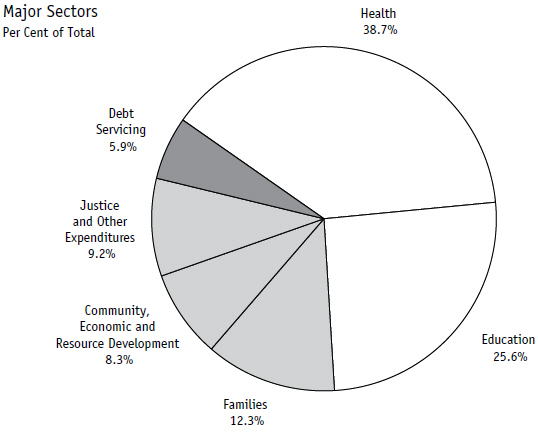

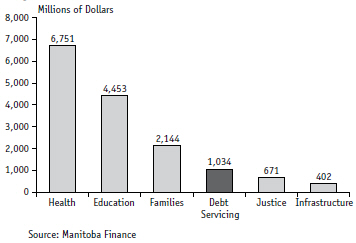

Expenditure

Expenditure in 2018/19 is projected to increase $367 million, or 2.2%, from the 2017/18 Budget. The growth in health expenditure is $70 million, or 1.0%. Education-related expenditure is increasing by $43 million, or 1.0%. Families is up $13 million, or 0.6%. Community, economic and resource development expenditure will decrease by $32 million, or 2.2%. The justice and other expenditures sector will increase by $230 million, or 16.8% mainly reflecting expenses of $102 million for the establishment of the new Conservation Trust Fund. Debt servicing is expected to increase by $43 million.

SUMMARY REVENUE

For the Fiscal Year Ending March 31, 2019 (Millions of Dollars)

With Comparative Data for the Fiscal Year Ending March 31, 2018

| | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | |

| | | | | | | | | Per Cent Change |

| | | | | | | | | 2018/19 Budget |

| | | 2018/19 | | 2017/18 | | 2017/18 | | from 2017/18 |

| Source of Revenue | | Budget | | Forecast | | Budget | | Forecast | | Budget |

| | | | | |

Income Taxes | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | |

Individual Income Tax | | | 3,475 | | | | 3,388 | | | | 3,651 | | | | | | | | | |

Corporation Income Tax | | | 566 | | | | 552 | | | | 543 | | | | | | | | | |

| | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | |

Subtotal: Income Taxes | | | 4,041 | | | | 3,940 | | | | 4,194 | | | | 2.6 | | | | (3.6 | ) |

| | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | |

Other Taxes | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | |

Carbon Tax | | | 143 | | | | – | | | | – | | | | | | | | | |

Corporations Taxes | | | 319 | | | | 300 | | | | 282 | | | | | | | | | |

Fuel Taxes | | | 345 | | | | 342 | | | | 334 | | | | | | | | | |

Land Transfer Tax | | | 89 | | | | 89 | | | | 84 | | | | | | | | | |

Levy for Health and Education | | | 352 | | | | 345 | | | | 342 | | | | | | | | | |

Retail Sales Tax | | | 2,463 | | | | 2,470 | | | | 2,360 | | | | | | | | | |

Tobacco Tax | | | 231 | | | | 234 | | | | 249 | | | | | | | | | |

Other Taxes | | | 10 | | | | 11 | | | | 11 | | | | | | | | | |

Education Property Taxes | | | 848 | | | | 829 | | | | 835 | | | | | | | | | |

| | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | |

Subtotal: Other Taxes | | | 4,800 | | | | 4,620 | | | | 4,497 | | | | 3.9 | | | | 6.7 | |

| | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | |

Fees and Other Revenue | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | |

Fines and Costs and Other Legal | | | 57 | | | | 59 | | | | 54 | | | | | | | | | |

Minerals and Petroleum | | | 13 | | | | 14 | | | | 11 | | | | | | | | | |

Automobile and Motor Carrier Licences and Fees | | | 155 | | | | 154 | | | | 154 | | | | | | | | | |

Parks: Forestry and Other Conservation | | | 35 | | | | 38 | | | | 34 | | | | | | | | | |

Water Power Rentals | | | 111 | | | | 118 | | | | 111 | | | | | | | | | |

Service Fees and Other Miscellaneous Charges | | | 1,623 | | | | 1,657 | | | | 1,635 | | | | | | | | | |

Tuition Fees | | | 339 | | | | 323 | | | | 308 | | | | | | | | | |

| | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | |

Subtotal: Fees and Other Revenue | | | 2,333 | | | | 2,363 | | | | 2,307 | | | | (1.3 | ) | | | 1.1 | |

| | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | |

Federal Transfers | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | |

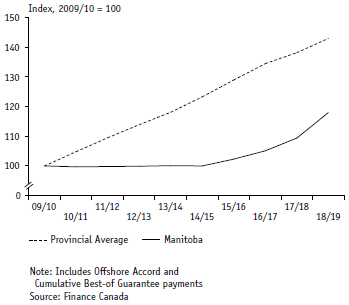

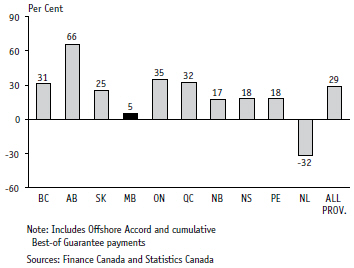

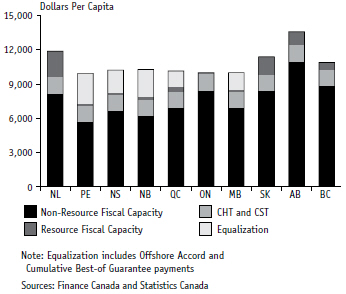

Equalization | | | 2,037 | | | | 1,820 | | | | 1,820 | | | | | | | | | |

Canada Health Transfer (CHT) | | | 1,441 | | | | 1,365 | | | | 1,355 | | | | | | | | | |

Canada Social Transfer (CST) | | | 518 | | | | 502 | | | | 502 | | | | | | | | | |

Shared Cost and Other Transfers | | | 500 | | | | 508 | | | | 486 | | | | | | | | | |

| | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | |

Subtotal: Federal Transfers | | | 4,496 | | | | 4,195 | | | | 4,163 | | | | 7.2 | | | | 8.0 | |

| | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | |

Net Income of Government | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | |

Business Enterprises (GBEs) | | | 842 | | | | 758 | | | | 705 | | | | 11.1 | | | | 19.4 | |

| | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | |

Sinking Funds and Other Earnings | | | 275 | | | | 252 | | | | 235 | | | | 9.1 | | | | 17.0 | |

| | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | |

Total Revenue | | | 16,787 | | | | 16,128 | | | | 16,101 | | | | 4.1 | | | | 4.3 | |

| | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | |

SUMMARY EXPENDITURE

For the Fiscal Year Ending March 31, 2019 (Millions of Dollars)

With Comparative Data for the Fiscal Year Ending March 31, 2018

| | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | |

| | | | | | | | | Per Cent Change |

| | | | | | | | | 2018/19 Budget |

| | | 2018/19 | | 2017/18 | | 2017/18 | | from 2017/18 |

| Sector/Department | | Budget | | Forecast | | Budget | | Forecast | | Budget |

| | | | | |

Health | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | |

| | | | | |

Health, Seniors and Active Living | | | 6,751 | | | | 6,633 | | | | 6,681 | | | | 1.8 | | | | 1.0 | |

| | | | | |

Education | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | |

| | | | | |

Education and Training | | | 4,453 | | | | 4,405 | | | | 4,410 | | | | 1.1 | | | | 1.0 | |

| | | | | |

Families | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | |

| | | | | |

Families | | | 2,144 | | | | 2,128 | | | | 2,131 | | | | 0.8 | | | | 0.6 | |

| | | | | |

Community, Economic and Resource Development | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | |

| | | | | |

Agriculture | | | 370 | | | | 228 | | | | 394 | | | | | | | | | |

| | | | | |

Growth, Enterprise and Trade | | | 107 | | | | 110 | | | | 113 | | | | | | | | | |

| | | | | |

Indigenous and Northern Relations | | | 34 | | | | 32 | | | | 32 | | | | | | | | | |

| | | | | |

Infrastructure | | | 402 | | | | 384 | | | | 400 | | | | | | | | | |

| | | | | |

Municipal Relations | | | 366 | | | | 362 | | | | 371 | | | | | | | | | |

| | | | | |

Sustainable Development | | | 162 | | | | 159 | | | | 163 | | | | | | | | | |

| | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | |

| | | | | |

Subtotal: Community, Economic and Resource Development | | | 1,441 | | | | 1,275 | | | | 1,473 | | | | 13.0 | | | | (2.2 | ) |

| | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | |

| | | | | |

Justice and Other Expenditures | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | |

| | | | | |

Legislative Assembly | | | 49 | | | | 46 | | | | 46 | | | | | | | | | |

| | | | | |

Executive Council | | | 4 | | | | 4 | | | | 4 | | | | | | | | | |

| | | | | |

Civil Service Commission | | | 21 | | | | 21 | | | | 21 | | | | | | | | | |

| | | | | |

Employee Pensions and Other Costs | | | 81 | | | | 82 | | | | 77 | | | | | | | | | |

| | | | | |

Finance | | | 351 | | | | 347 | | | | 352 | | | | | | | | | |

| | | | | |

Justice | | | 671 | | | | 658 | | | | 661 | | | | | | | | | |

| | | | | |

Sport, Culture and Heritage | | | 87 | | | | 88 | | | | 83 | | | | | | | | | |

| | | | | |

Enabling Appropriations | | | 284 | | | | 74 | | | | 74 | | | | | | | | | |

| | | | | |

Other Appropriations | | | 52 | | | | 79 | | | | 52 | | | | | | | | | |

| | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | |

| | | | | |

Subtotal: Justice and Other Expenditures | | | 1,600 | | | | 1,399 | | | | 1,370 | | | | 14.4 | | | | 16.8 | |

| | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | |

| | | | | |

Debt Servicing | | | 1,034 | | | | 964 | | | | 991 | | | | 7.3 | | | | 4.3 | |

| | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | |

| | | | | |

Total Expenditure | | | 17,423 | | | | 16,804 | | | | 17,056 | | | | 3.7 | | | | 2.2 | |

| | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | |

Revenue, 2018/19

Expenditure, 2018/19

FISCAL RESPONSIBILITY STRATEGY 2018/19:

KEEPING OUR PROMISES

FISCAL RESPONSIBILITY STRATEGY 2018/19: KEEPING OUR PROMISES

CONTENTS

| | | | |

FISCAL RESPONSIBILITY STRATEGY: KEEPING OUR PROMISES | | | 9 | |

| |

MANITOBANS MAKING CHOICES | | | 11 | |

| |

FOCUS ON SUMMARY | | | 12 | |

| |

BUILDING THE BUDGET – FOCUS ON OUTCOMES | | | 14 | |

| |

REBUILDING THE ECONOMY | | | 21 | |

| |

SECURING OUR FUTURE: IMPROVEMENTS TO THE FISCAL RESPONSIBILITY AND TAXPAYER PROTECTION ACT | | | 24 | |

| |

THE PATH FORWARD | | | 25 | |

FISCAL RESPONSIBILITY STRATEGY: KEEPING OUR PROMISES

Our government inherited a legacy of unsustainable annual increases in spending, ballooning deficits, and faltering services. Our economy was becoming ever more dependent on public spending and increasingly exposed to risk of further credit downgrades and interest rate hikes.

We have a measured plan to deal with these challenges and make Manitoba the most improved province in Canada. This requires hard work. To keep our promise, we need to take nearly a billion dollars of wasteful spending out of our annual budget, focusing on outcomes and value for the money we are spending today in order to create better opportunities in the future.

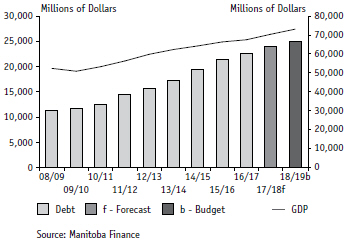

Budget 2018 delivers on our commitment to restore stability to our finances, secure our public services and strengthen the economy for Manitobans, even as our debt servicing costs are budgeted to increase to over a billion dollars this year. We are also setting clear objectives to manage future financial volatility and to further improve financial transparency and accountability.

These are our promises. And we intend to fulfill these promises. Manitobans deserve a break.

Storm Clouds

Manitoba’s ability to withstand economic turbulence may be tested significantly over the coming year, as a number of factors combine to create a period of considerable volatility. As an economy that relies on export revenue in a number of key sectors, uncertainty over the future of the North American Free Trade Agreement casts an ominous shadow. The United States is Manitoba’s largest trading partner; the erosion of this relationship would have immediate and severe consequences for Manitoba. Within Canada, the increased frequency and severity of interprovincial trade disputes threatens to undermine the viability of both the New West Partnership and the Canadian Free Trade Agreement.

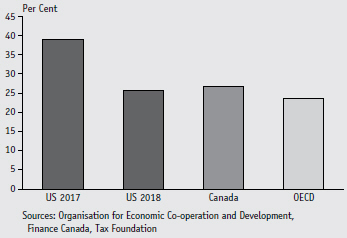

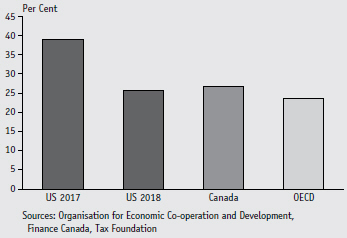

Manitoba’s tax competitiveness is also a growing issue. Tax reforms recently adopted by the United States government have significantly reduced both personal and corporate tax rates, challenging Manitoba’s ability to compete with American states for investment, job recruitment and skilled professionals. Exacerbating this challenge are recent tax increases implemented by the Government of Canada, which created significant volatility in provincial personal income tax receipts – from $160 million over expectations in 2016, to $262 million below expectations in 2017. We have yet to see evidence that income tax revenues will return to previous levels in 2018/19, which puts material pressure on Manitoba’s finances, despite a strong underlying economy.

Also looming over Manitoba’s economy is the probability of higher interest rates. Central banks throughout the world, including the Bank of Canada, have begun to slowly increase their rates and have signaled that additional rate hikes may occur over the coming year. In 2018/19, our borrowing costs will surpass one billion dollars – up $70 million year over year. This increase is attributable to increased debt from higher borrowings ($50 million) as well as the impact of higher interest rates ($20 million). On a full-year basis, the short-term impact of a 1% increase in interest rates could approach $100 million, with the longer term impact being much greater. To put this in context, debt servicing costs – if this were a government department – would be our fourth largest department – larger than Justice!

Major Areas of Spending

MANITOBANS MAKING CHOICES

Budget 2018 is informed by pre-budget consultations that engaged close to 35,000 Manitobans, almost double the previous record set in 2017.

Our consultation process included an online survey, community consultations and three telephone-based town halls. In addition, hundreds of Manitobans submitted letters to the Minister of Finance, offering their input and highlighting their priorities for Budget 2018.

Here is what Manitobans told us:

Manitobans agree that:

| ● | | fixing our fiscal situation is a top priority |

| ● | | the current debt load is unsustainable |

| ● | | a moderate path to balancing the budget is reasonable |

| ● | | the Manitoba Civil Service can be streamlined through attrition and trimming senior management positions |

Manitobans want a health care system that is cost-effective and focused on delivering quality and timely care. They agree that:

| ● | | cost savings can be found within the system |

| ● | | wait times must be reduced, increasing the availability of high tech equipment and freeing up more personal care home beds |

| ● | | a health care premium is not right for Manitoba |

| ● | | the federal government should cover half of the province’s health care costs |

Manitobans want a cannabis policy that ensures:

| ● | | criminal gangs are out of the cannabis business |

| ● | | the safety of citizens, whether or not they are using cannabis |

FOCUS ON SUMMARY

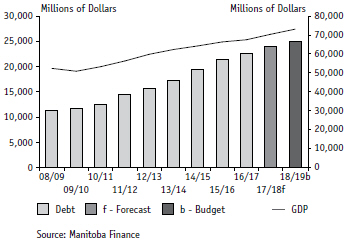

For many years, annual government budgets focused on core government departments, and less attention was paid to other government entities such as the crown corporations. In 2007, Manitoba fully implemented Canadian Public Sector Accounting Standards which require the consolidation of all government entities under a single budgeting and reporting framework to improve transparency and provide citizens with a “whole of government” perspective. This comprehensive approach is consistent with the way most Manitobans and credit rating agencies assess governments’ fiscal performance, and ensures that public services are consistently and properly managed.

Summary statements acknowledge this reality by reporting on all entities of government that provide provincial public services paid for by Manitobans, whether through taxes or rate payments such as hydro or auto insurance. It is for this reason that Manitoba’s balanced budget legislation applies to Summary statements, and that a portion of the ministers’ pay is impacted by these results. By extension, any summary deficit increases net debt.

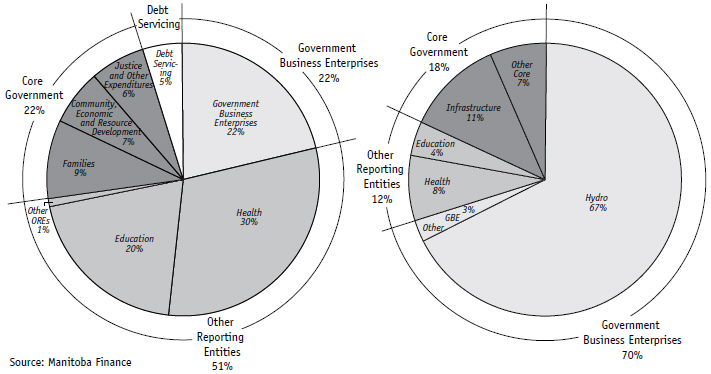

While accounting and budgeting has evolved to include other entities, the related financial decision-making framework has remained largely segregated, with government focused on the core departments over which the Legislative Assembly exercises direct control. The central Manitoba government departments not influenced by multiple Other Reporting Entities (ORE) make up only 22% of Manitoba’s summary expenditure budget, while the four crown corporations that are Government Business Enterprises (GBE) represent 22% of expenditures, 25% of revenue and 70% of capital investment.

In the summary budget, GBEs are consolidated on a modified equity basis. The following illustration shows the relative total scope of GBE expenditures compared to core government and OREs. For purposes of this illustration the Health and Education sectors are included with OREs as the majority of the departmental expenditures ultimately flow to school divisions and regional health authorities.

| | |

| Total 2018/19 Expenditures | | Total 2018/19 Capital |

| Per Cent of Total | | Per Cent of Total |

| | | | | | |

| | Summary Budget Defined Manitoba’s summary budget includes revenue forecasts and expenditure estimates for government departments as well as projections for the approximately 180 other reporting entities. This is a “whole of government” reporting approach for Manitoba’s public services. | | | | Impact of OREs and GBEs

|

There are approximately 180 reporting entities across summary government, including major crown corporations (Manitoba Hydro, Manitoba Public Insurance and Manitoba Liquor and Lotteries), universities and colleges, | | | |

school divisions and the health and family services authorities, as well as major insurance providers like the Workers Compensation Board and the Manitoba Agricultural Services Corporation. Financial variability in even one of these entities dramatically impacts our ability to improve Manitoba’s fiscal position and directly impacts how much funding is available for other core programs and services.

We are asking reporting entities to take the same steps that government departments have taken – streamlining the workforce, reducing management structures and pivoting towards achieving the outcomes that Manitobans demand and deserve. We are also working to reduce volatility. Increasingly this will be a part of our plan to bring the summary budget into balance.

Taking Inventory

Prudent financial stewardship requires taking stock of what you own and assessing how much of it has value going forward. In the process of taking inventory, we have discovered that the previous government’s actions resulted in over-valued or worthless assets being held on our books, creating situations where we have liabilities that are not properly recorded and are unnecessarily exposing our finances to added risk. Over the past year, as we familiarized ourselves with the extent of these risks, we have taken prudent measures to put our financial house back in order. Recovering from past decisions and clarifying the status of our assets will restore public confidence in Government’s accounting practices and, more importantly, put our books on a more predictable and stable foundation. This work continues and further details of our progress will be provided upon release of the 2017/18 Public Accounts.

BUILDING THE BUDGET – FOCUS ON OUTCOMES

We are taking meaningful steps to create a sustainable financial future for Manitoba, and the results speak for themselves: since 2016, we have managed within the budgets we set and have reduced the deficit each year. In 2018, we will build on that progress.

Cost Drivers – Human Resources

Across Summary government, people are our strongest asset but also our largest cost driver.

| | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | |

Group | | Number of Employees

(Estimated) | | Total Pay

and Benefits | | Number of

Agreements | | |

Core Government | | | | 14,000 | | | | | $1.1 B | | | | | 9 | | | | | | |

Crown Corporations | | | | 10,000 | | | | | $0.9 B | | | | | 18 | | | | | | |

Healthcare | | | | 52,000 | | | | | $4.3 B | | | | | 182 | | | | | | |

Universities and Colleges | | | | 13,000 | | | | | $0.9 B | | | | | 24 | | | | | | |

Schools (K–12) | | | | 26,000 | | | | | $2.2 B | | | | | 119 | | | | | | |

Child Welfare Agencies | | | | 8,000 | | | | | $0.2 B | | | | | 11 | | | | | | |

Total | | | | 123,000 | | | | | $9.6 B | | | | | 363 | | | | | | |

Put another way, payroll approaching $10 billion represents a sizable majority of our total annual expenses, representing nearly 49 different unions and associations, and 20% of the total Manitoba workforce.

To manage these costs, we established sustainable salary expectations through The Public Services Sustainability Act. We are working to streamline collective bargaining in the health and education sectors, where there are currently 182 and 38 bargaining units, respectively. We have also reduced core government management by over 15% and have initiatives in place to harness the natural annual attrition rate to reduce the core government employee count by 8% over 4 years.

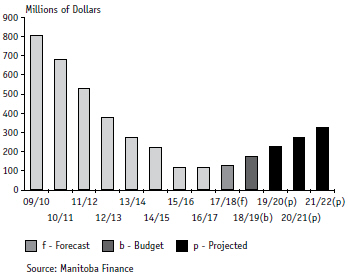

Cost Drivers – Previous Capital Investments

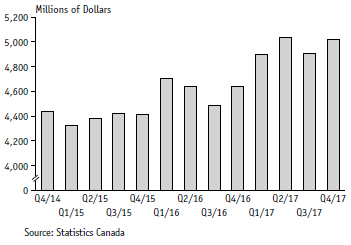

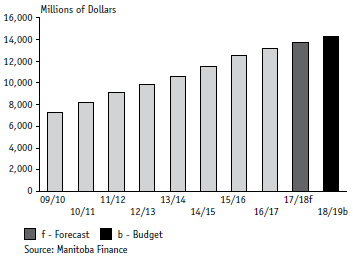

For many years, significant capital investments were undertaken without regard for their sustainability, and they are now compromising our ability to live within our means and make progress on eliminating the deficit. For example, in the Department of Infrastructure, capital debt repayment (including enabling expenses) represents 70% of its 2018/19 operating expenditures. Even if we were to choose to make no further capital investment in our highways and bridges, we would still be spending over $450 million annually for years to come, just to pay for the decisions of the past.

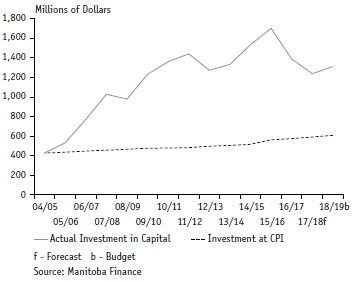

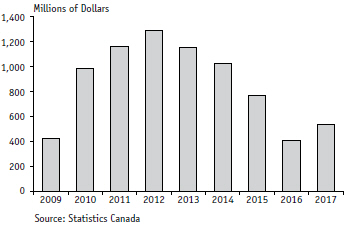

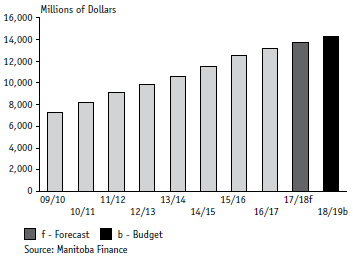

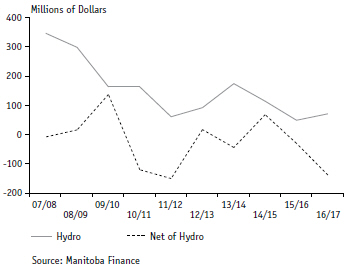

Last year’s budget highlighted the challenges resulting from past unsustainable capital spending levels; levels that had quadrupled over a period of 11 years to their peak in 2015/16, when growth at the rate of inflation would have resulted in only a 32% increase.

Debt Financed Capital Spending from

2004/05 to 2018/19

The level of growth in core debt-financed capital has resulted in a $2 billion increase in net debt over the past five years and a corresponding increase in interest costs to the Province, comprising a much larger share than in the past.

Not only did this growth reflect unprecedented and unsustainable increases – it also occurred without a focus on return on investment.

In response, our government has developed a comprehensive long-term strategy to bend the capital cost curve starting with a 6.9% reduction in Strategic Infrastructure from 2017/18 Budget levels. Through the later half of 2017, the Manitoba Government undertook significant work to develop tools to assess capital spending programs, resulting in some delays and related reductions in capital spending.

As promised in the 2016 Throne Speech, a new return on investment test to prioritize government investments is being applied to ensure Manitobans receive value for their money. We are making all of these changes to spend capital in more thoughtful ways, all while keeping our election promise to spend more than a billion dollars every year on Strategic Infrastructure.

The 2018/19 capital budget reflects priorities of:

| ● | | minimizing costs of asset ownership; |

| ● | | valuing “fix and repair” over conspicuous construction of unnecessary structures; |

| ● | | investing in schools for underserved communities that have been neglected in the past; |

| ● | | health transformation; and |

| ● | | environmental infrastructure in response to climate change. |

Strategic Infrastructure 2018/19

| | | | | | | | | | | | |

| Millions of Dollars | | 2018/19

Budget | | 2017/18

Forecast | | 2017/18

Budget |

| | | |

Roads, Highways, Bridges and Flood Protection | | | | | | | | | | | | |

| | | |

Highways Infrastructure and Airport Runway Capital | | | 355 | | | | 436 | | | | 510 | |

| | | |

Maintenance and Preservation – Highways | | | 136 | | | | 146 | | | | 143 | |

| | | |

Water Related Infrastructure | | | 104 | | | | 45 | | | | 60 | |

| | | |

Transportation Equipment and Aircraft | | | 17 | | | | 12 | | | | 19 | |

| | | |

Maintenance and Preservation – Water | | | 12 | | | | 14 | | | | 15 | |

| | | | | | | | | | | | |

| | | |

Subtotal | | | 624 | | | | 653 | | | | 747 | |

| | | |

Health, Education and Housing | | | | | | | | | | | | |

| | | |

Health | | | 319 | | | | 183 | | | | 358 | |

| | | |

Education | | | 168 | | | | 95 | | | | 176 | |

| | | |

Housing | | | 90 | | | | 95 | | | | 107 | |

| | | | | | | | | | | | |

| | | |

Subtotal | | | 577 | | | | 373 | | | | 641 | |

| | | |

Other Provincial Infrastructure | | | | | | | | | | | | |

| | | |

Municipal and Local Infrastructure | | | 178 | | | | 181 | | | | 189 | |

| | | |

Public Service Buildings, Equipment and Technology | | | 171 | | | | 57 | | | | 88 | |

| | | |

Parks, Cottage and Camping | | | 12 | | | | 1 | | | | 12 | |

| | | | | | | | | | | | |

| | | |

Subtotal | | | 361 | | | | 239 | | | | 289 | |

| | | | | | | | | | | | |

| | | |

Total Strategic Infrastructure | | | 1,562 | | | | 1,265 | | | | 1,677 | |

| | | | | | | | | | | | |

NOTES:

| • | | The 2017/18 forecast and budget have been restated to be consistent with the 2018/19 budget presentation. |

For too long, our capital spending priorities have focused on new, conspicuous head offices, while ignoring basic needs like schools and failing to maintain the institutions that we own. This budget sets the stage for a major investment in five new schools that will result in schools’ share of total capital spending increasing significantly in 2019/20. This investment reflects our commitment to addressing a history of neglect, which has resulted in too many students trying to learn in crowded schools and portable classrooms.

Last year, we announced that we would explore the feasibility and benefits of building schools under a Public-Private Partnerships (P3) model, and we retained KPMG to advise us on this approach and to share the experience of other jurisdictions. While we remain fully committed to the benefits of P3s and partnering with private enterprise, we will always turn to evidence and pursue the best value for money. For a number of reasons – including lack of scale for P3 schools, the increased timeline and expense of a P3 tendering process, the urgent need to open new schools and the value for money, we have decided to build these schools using an enhanced conventional tender. Informed by our review of the P3 construction process, the Public Schools Finance Board (PSFB) has incorporated new, leading-edge practices including tendering multiple schools simultaneously. As a result, the cost of constructing these five schools has been reduced by nearly $19 million, and three of the five schools will be completed a year ahead of schedule.

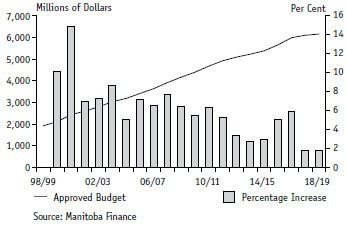

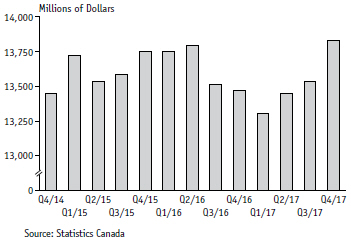

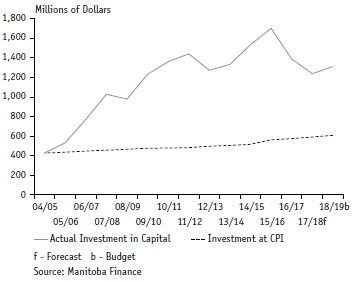

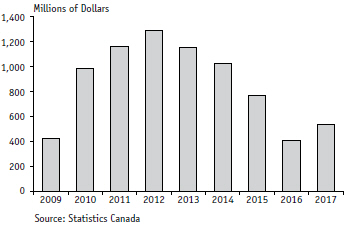

Cost Drivers – Health Care

| | | | |

Healthcare spending has grown to represent over 40% of our core budget. Over the past 20 years, healthcare budgets have tripled, from $1.9 billion in 1998 to $6.2 billion in 2018 without a commensurate improvement in outcomes. When we took office in 2016, per capita health expenditures in Manitoba were the fourth highest expenditure level amongst the provinces. At the same time, our wait times were consistently among the longest in Canada. We have turned to evidence in our review of Manitoba’s overall healthcare system. We have discovered that the current governance model is overly complex for a province of our size, and Manitobans are not receiving an optimal level of care. In addition, accountability for results is fractured and inadequate across the system. | | | | Manitoba Health, Seniors and Active Living Historical Budget Trend

|

2017/18 was a pivotal year for health care in Manitoba. A new Transformation Management Office is overseeing reforms to reduce costs and improve services. At the same time, we have introduced new accountability within the system to better measure outcomes and put service delivery on a more sustainable path. Even the little changes are important. Our health-related entities will be moving from government not-for-profit accounting standards to Canadian Public Sector Accounting Standards in an effort to standardize reporting, and ensure the timely verification and compilation of information for summary budgeting and reporting. It is hard to believe that for years, our province’s health-related entities did not use the same accounting standards as the Government, impairing their capacity for effective information sharing and coordination.

Cost Drivers – Legalization of Cannabis

The current path toward legalization of cannabis has been rushed, and we have repeatedly expressed our concern that it is more important to get it right than to meet an arbitrary deadline.

We are focused on public safety, including elimination of the black market. If cannabis is not priced competitively, it will not gain market share and the black market will continue to thrive, which is bad for Manitobans and particularly bad for our children. Not knowing the expected tax revenue, or associated costs of cannabis, means that we are not building our budget on a hope of revenue that we cannot predict, because hope is not a plan.

What we know for certain, and all provinces agree, is that the province will bear the majority of the costs of legalizing cannabis, including healthcare, education, road safety, justice and more, and that we expect these increased costs to outweigh any revenue gains.

Focus on Outcomes

In the past, funding was provided to many of our most critical partners with limited or no reporting on outcomes – failure was not addressed and success was not rewarded.

We have talked about “bending the cost curve”, but this is about transforming our culture and rethinking how we do things. Focusing on outcomes is the only way to drive costs out of the system while preventing adverse impacts on the services Manitobans expect and deserve. Examples of our new approach to spending include:

| ● | | a new value for money assessment tool to guide our investments in cultural capital, including the Assiniboine Park Conservancy, Winnipeg Art Gallery, and Royal Aviation Museum of Western Canada; |

| ● | | block funding arrangements to reduce red tape and allow agencies to deliver the right services to the right people in the right way without relying on complex funding formulas or unintended incentives to drive costs and limit innovation. We have already introduced block funding for municipalities and some family services agencies and are continuing to explore other opportunities in this area; |

| ● | | a greater focus on competitive procurement processes as well as social impact procurement, including leveraging social enterprises and pay for performance models such as Social Impact Bonds; and |

| ● | | working toward consolidation of common functions, such as finance and administration. |

All of these tools require common approaches to public procurement processes that are transparent, comprehensive and drive value across the public sector. We are engaging support to develop better procurement practices that will harness savings across government in areas that range from information technology, to equipment purchases to maintenance and repair contracts.

We are also continuing to explore alternative service delivery opportunities, not only to improve service, but also to reduce costs. This year, we are reviewing options to improve the cost-effectiveness of aircraft services within government and will be issuing a Request for Proposals to explore better ways to achieve value in this program.

All of these innovative efforts will be carefully monitored for success. We are focusing on outcomes by deploying Balanced Scorecards throughout core government and, in the coming year, will also be reporting publicly on how we are doing – both our successes and where we find a need for improvement or a different approach.

Transforming the Public Service

In addition to the economic circumstances we face, rapid advances in technology and changes in Manitobans’ expectations also present significant challenges. To face these complex issues successfully, we must learn from proven good practices and leverage the talent and ideas of public servants, and create space for innovation to grow.

In February of this year, we shared Manitoba’s Transformation Strategy, setting out a bold vision for the future and providing a framework for public servants to take action to transform both their work and their culture. This strategy provides an opportunity to build a modern public service culture that will attract and retain diverse, skilled and innovative employees into the future. Introducing Balanced Scorecards and external reporting of outcomes is a key pillar in this initiative.

We are also advancing our commitment to Open Government. This spring, we will streamline Manitoba’s process for consulting with citizens. We will launch an online portal to centralize and simplify the mechanism through which citizens provide input into government programs and services. With improved information from citizens, the public service will be better equipped to focus its efforts on priorities that will advance outcomes for Manitobans.

Giving Manitobans a Well-Deserved Break

When our Government was elected in April 2016, Manitoba’s tax regime was out of line with other provinces: we had one of the lowest basic personal income tax exemptions, the tax treatment for small business income was not competitive, and we were handed the highest sales tax rate in Western Canada.

Soon after taking office, we proudly introduced tax bracket indexation, and are now continuing on our work. Budget 2018 makes significant strides to give Manitoba families and individuals a well-deserved tax break and restore a competitive tax environment.

Reducing the Provincial Sales

Tax from 8% to 7%

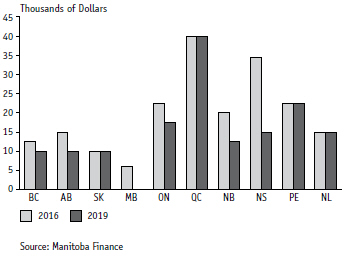

The following table shows provincial sales tax rates applicable before the 2016 budget and projected to 2020. Manitoba is the only province to announce a rate reduction. Manitoba’s rate will match British Columbia’s and be lower than any province east of Manitoba.

Our sales tax reduction will also improve Manitoba’s business tax competitiveness, stimulate the economy and put money back into the hands of Manitobans.

Provincial Sales Tax Rates

| | | | |

| | | 2016

(pre-budget) | | 2020 |

| | | |

British Columbia | | 7% | | 7% |

| | | |

Alberta | | n/a | | n/a |

| | | |

Saskatchewan | | 5% | | 6% |

| | | |

Manitoba | | 8% | | 7% |

| | | |

Ontario | | 8% | | 8% |

| | | |

Quebec | | 9.975% | | 9.975% |

| | | |

New Brunswick | | 8% | | 10% |

| | | |

Nova Scotia | | 10% | | 10% |

| | | |

Prince Edward Island | | 9% | | 10% |

| | | |

Newfoundland and

Labrador | | 8% | | 10% |

| | |

☐ Rate increase | | ☐Rate decrease |

Source: Manitoba Finance

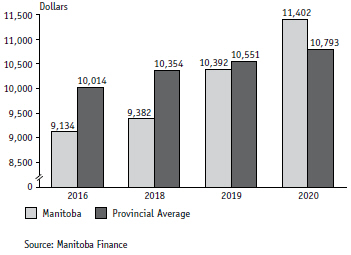

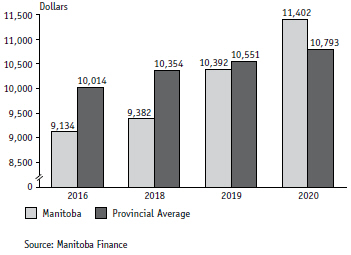

Increasing the Basic Personal Amount – $2,020 by 2020

| | | | |

Provincial Basic Personal Amounts

| | | | The “basic personal amount” is the amount of income that is exempt from personal income taxes or, put another way, the amount a person can earn before the government starts to tax you. The larger the basic personal amount, the better for all taxpayers. In 2016, Manitoba’s basic personal amount was the only one outside of Atlantic Canada that was below $10,000. We plan to increase Manitoba’s basic personal amount by $1,010 on January 1, 2019 and again by $1,010 on January 1, 2020 – or “$2,020 by 2020”. As a result, Manitoba’s basic personal amount will exceed $11,400 and outpace the provincial average across Canada. Increasing the basic personal amount will help all taxpayers, but will disproportionately benefit the working poor who will either no longer pay |

provincial income tax at all or have a much higher percentage of their income tax-free, keeping hard earned money in the homes of those who need it most. Through this change, we anticipate that by 2020 a total of 31,000 low income earners will no longer need to pay taxes.

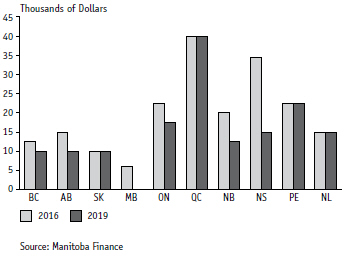

Increasing the Small Business Income Threshold to $500,000

| | | | |

Provincial Corporation Income Tax Small Business Tax on $500,000 in 2016 and 2019

| | | | We know small businesses are the mainstay of the Manitoba economy. Manitoba recognizes their value by increasing the small business income threshold eligible for Manitoba’s 0% corporation income tax rate, the lowest in Canada. A small business with up to $500,000 taxable income will now be exempt from Manitoba corporate income tax. Lowering Taxes to the Benefit of all Manitobans The Manitoban economy is doing very well. At the same time, we see federal tax policies that threaten small businesses and challenge top income earners in Canada, alongside large reductions in US corporate and personal tax rates. Manitobans need a break, and businesses need to remain competitive in the Canadian and Global market place. |

REBUILDING THE ECONOMY

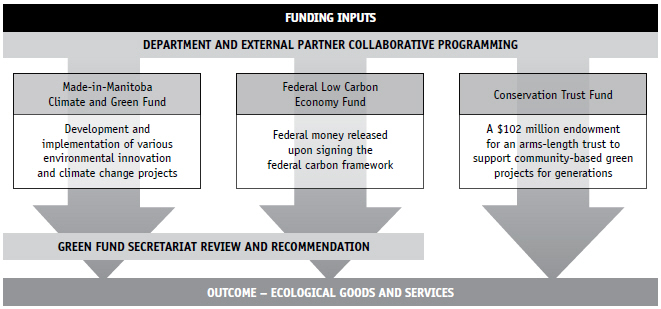

Climate and Green Plan

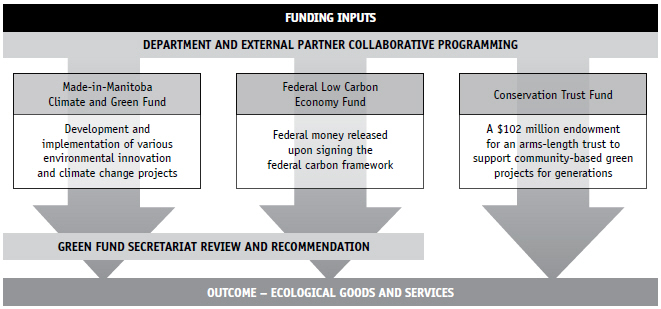

This past October, we released our Made-in-Manitoba Climate and Green Plan that aims to make Manitoba the cleanest, greenest and most climate resilient province in Canada. Our Plan integrates environmental and economic objectives across all of government based on four pillars – climate, jobs, water, and nature.

Our choices were either to agree to the federally-mandated carbon tax dictated and controlled by Ottawa, or to find our own “Made-in-Manitoba” carbon plan. Budget 2018 follows through on our commitment to develop a Made-in-Manitoba approach to reduce our greenhouse gas emissions. All carbon tax revenues received over the next four years will be returned to Manitobans through tax reductions.

Budget 2018 includes the historic establishment of a $102 million Conservation Trust Fund to protect wetlands, grasslands, forests and natural areas by providing matching funds to partnerships with private investors, landowners and community based conservation organizations. We have also formed a “Made-in-Manitoba Climate and Green Fund” that will provide the necessary funds to implement our Made-in-Manitoba Climate and Green Plan, and we look forward to partnering with the federal government on climate change programs.

Economic Development

Jobs and economic growth remain at the centre of our plan for a better Manitoba. A stronger economy will allow for improvements in front line services and additional investments in the programs and initiatives most important to Manitoba families while also repairing the state of the province’s finances. Manitobans recognize that better services depend on a stronger economy, and we have taken the first steps on the road to making Manitoba the most improved jurisdiction for investment and job creation.

In the past, Manitoba did not have a clearly articulated, evidence-based approach to economic development, but rather, a disjointed collection of mismatched programs that were added, incrementally, over time. Further, programs that were added were not reviewed to determine if they had achieved their intended outcomes.

This past year, we undertook a comprehensive assessment of the state of our economic development efforts. We sat down with our business leaders to gather their views and give us their expert recommendations on how to make Manitoba the most improved province when it comes to attracting business investment.

Our report confirmed the absence of clearly defined goals and objectives, significant areas of mandate overlap amongst our many economic development agencies, and a lack of coordination within government departments.

We are committed to addressing these shortcomings, and have asked senior Manitoban business leaders to direct the next step of designing our overall strategy and reforming the way we attract business investment to our province.

Look North

As part of advancing economic development across Manitoba, we see the North as the key to unlocking our economic potential.

The Look North Report and Action Plan for Manitoba’s Northern Economy outlines a path forward to building stronger partnerships and a brighter economic future in the North. The report identifies six priority areas including northern mineral and other resource potential; Indigenous engagement and partnerships; strategic infrastructure investment; housing challenges and opportunities; enterprise eco-system of support; and education, training and workforce development.

A northern steering committee and joint action groups for each of the priority areas have been established to lead and engage stakeholders in the next phase of work to develop more detailed strategies and action plans to help unlock the tremendous economic potential that exists in this region.

At the same time, we have committed to establishing a mineral development protocol with First Nations to create a clear pathway forward and a stable and predictable consultation process that ensures First Nations are involved in all aspects of mineral development and share in the resulting benefits. We will continue our work with First Nations communities to define a mutually agreed process that will advance mineral development projects in Indigenous traditional territories.

The Look North Report highlighted access to broadband as a priority area and one of the most common topics to arise in discussions with northerners. Our government recently announced a $20 million contribution towards a $63-million project to bring high-speed Internet to 72 rural and remote communities in the province, 37 of which are First Nation communities and 18 of which are located in remote regions of northern Manitoba. This announcement is exemplary of how strong partnerships with our federal counterparts and Indigenous organizations can advance shared priorities and modernize and transform the economic future of the region.

Reducing Red Tape

According to industry estimates, federal, provincial and municipal regulations cost businesses in Manitoba $1.2 billion, of which $360 million is considered unnecessary. Seven out of ten business owners in Manitoba say red tape is limiting their ability to create jobs. Reducing this red tape is an important part of our plan to grow the

economy, and we are committed to becoming Canada’s most improved province by reducing the burden of regulatory requirements that are poorly designed, duplicative, contradictory, anachronistic or overly prescriptive.

The Regulatory Accountability Act that was introduced in June 2017 requires the measurement, tracking and reporting of regulatory requirements found in legislation, regulations, policies, and forms. As part of this process, more than 906,000 regulatory requirements were identified in the baseline count measured as of April 1, 2016.

This new Act introduces a number of innovative mechanisms to promote regulatory accountability and reduce red tape, including the 2-for-1 rule, which will require two regulatory requirements to be removed for every new one introduced.

Business is taking note. Stakeholders have publicly stated that Manitoba’s red tape measure is the best of its kind in North America. During Canada’s 2018 Red Tape Awareness Week, Manitoba received an “A” grade in the Canadian Federation of Independent Business’ (CFIB) 2018 Provincial Red Tape Report Card for significant progress on regulatory accountability and red tape reduction. This ties Manitoba for first with British Columbia and Quebec. By comparison, Manitoba’s last grade under the previous government in 2016 was an “F”, the worst grade amongst provinces.

Manitoba also won the CFIB’s 2018 Golden Scissors Award in recognition of its leadership on red tape reduction through introduction of The Regulatory Accountability Act and The Red Tape Reduction and Government Efficiency Act 2017.

Allowing the Private Sector to Flourish

The underlying economy in Manitoba is strong:

| ● | | Total employment increased by 10,500 workers, the largest gain in 15 years; |

| ● | | Private sector jobs increased by 11,800 workers, the largest gain in 15 years; |

| ● | | Second highest increase in average weekly earnings among provinces and highest since 2014; |

| ● | | Labour income growth has improved to 4.7% in 2017, compared to 0.8% in 2016; |

| ● | | Manufacturing sales increase by 5.3%, best in six years; |

| ● | | Wholesale merchandise sales increased by 7.4%, best since 2014; |

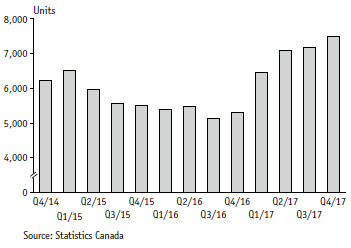

| ● | | Motor vehicle sales increased by 10.1%, best in 15 years; |

| ● | | Truck and SUV sales are up by 15.4%, best in 20 years; |

| ● | | Exports to the Non-U.S. markets increased by 13.0%, best in six years; |

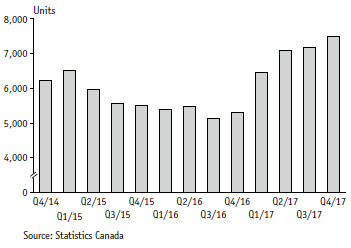

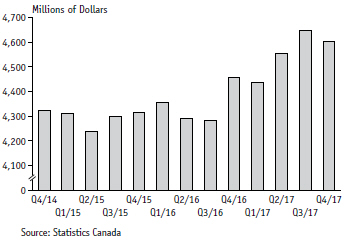

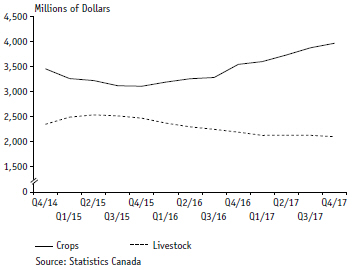

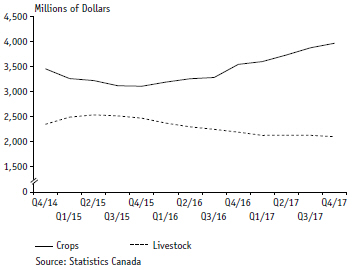

| ● | | Manitoba crop farmers report a record volume of harvest (bushels) in 2017; and |

| ● | | Total farm cash receipts surpassed $6.5 billion in 2017, the highest ever in Manitoba. |

SECURING OUR FUTURE: IMPROVEMENTS TO THE FISCAL RESPONSIBILITY AND TAXPAYER PROTECTION ACT

The Fiscal Responsibility and Taxpayer Protection Act affirms fiscal discipline and accountability to Manitobans on sustainable financial management. It requires that governments show progress toward a balanced budget that is based on summary results.

Amendments will be introduced to strengthen the Act. The improvements will create greater incentives for difficult – yet essential – work in restoring our finances, and remove disincentives against early progress or the extra achievement beyond $100 million per year. Measuring progress from the 2017/18 budget, the Act will also allow for reinstatement of ministerial salary amounts withheld once a surplus is achieved in future. Finally, to improve transparency, we will now report each minister’s respective withheld salary amounts.

As a result of the tabled Budget 2017, the baseline (which is adjusted for things such as emergencies and Hydro net income) was calculated as follows:

The Fiscal Responsibility and Taxpayer Protection Act

Base Line Deficit Results

(Millions of Dollars)

| | | | |

| | | 2017/18

Budget | |

| |

Revenue | | | 16,101 | |

| |

Expenditure | | | 17,056 | |

| | | | |

| |

Net Result | | | (955) | |

| |

Year-end Adjustments/Lapse | | | (115) | |

| | | | |

| |

Net Income (Loss) | | | (840) | |

| | | | |

| |

Adjustments: | | | | |

| |

1) Net Income (Loss) Manitoba Hydro | | | 74 | |

| |

2) Fiscal Stabilization Fund | | | 10 | |

| | | | |

| |

Base Line Deficit | | | (924) | |

| | | | |

It is upon this baseline that the Government will be held accountable to make steady progress. In fact, results will need to show an improvement of $100 million a year, every year, in order for ministers to realize all of their pay.

THE PATH FORWARD

For a 13 year period prior to 2016/17, core expenditure budgets were consistently over spent. Over that period, total overspending was $1.7 billion excluding the costs of the 2011 flood, or almost $140 million per year on average.

For 2017/18, we are forecasting the second straight year of keeping spending below budgeted levels through careful management and steady execution of our promises, and we accomplished this despite the most significant reduction in individual income tax revenue in a generation and prudently adding a contingency for writedowns. The forecasted 2017/18 year-end results, as adjusted pursuant to the Act, are estimated as set forth below.

The Fiscal Responsibility and Taxpayer Protection Act

Base Line Deficit Results

(Millions of Dollars)

| | | | | | | | | | | | |

| | | 2017/18

Budget | | 2017/18

Forecast | | Increase/

(Decrease) |

| | | |

Revenue | | | 16,101 | | | | 16,128 | | | | 27 | |

| | | |

Expenditure | | | 17,056 | | | | 16,854 | | | | (202 | ) |

| | | | | | | | | | | | |

| | | |

Net Result | | | (955 | ) | | | (726 | ) | | | 229 | |

| | | |

Year-end Adjustments/Lapse | | | (115 | ) | | | – | | | | 115 | |

| | | | | | | | | | | | |

| | | |

Net Income (Loss) | | | (840 | ) | | | (726 | ) | | | 114 | |

| | | | | | | | | | | | |

| | | |

Adjustments: | | | | | | | | | | | | |

| | | |

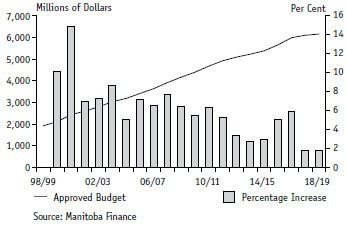

1) Net Income (Loss) Manitoba Hydro | | | 74 | | | | 40 | | | | (34 | ) |

| | | |

2) Fiscal Stabilization Fund | | | 10 | | | | 10 | | | | – | |

| | | | | | | | | | | | |

| | | |

Base Line Deficit | | | (924 | ) | | | (776 | ) | | | 148 | |

| | | | | | | | | | | | |

| | |

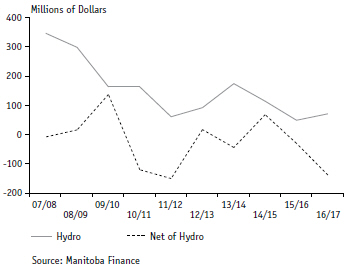

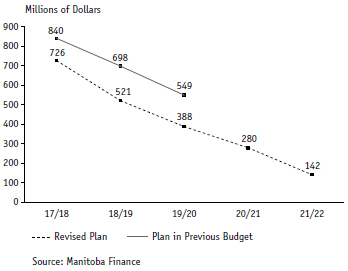

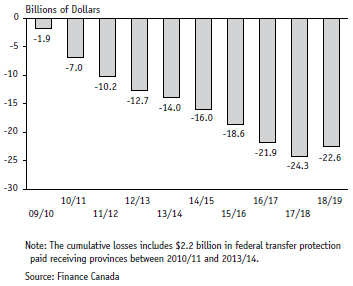

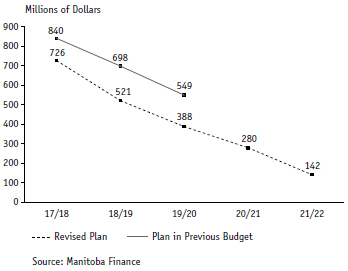

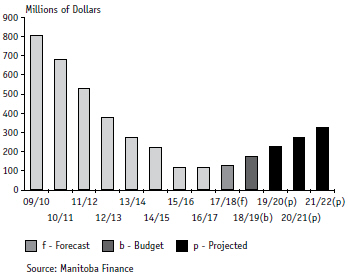

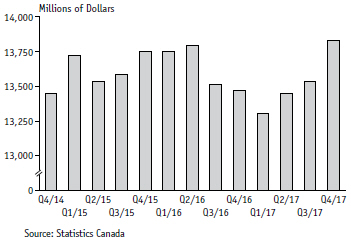

As we look forward to the next four years, our projections show steady progress on deficit reduction into the future, while at the same time delivering tax relief from the Cabinet table to the kitchen table of Manitobans. This revised projection differs from the projections offered as part of Budget 2017, showing a new and improved “trajectory” to budget reduction. We have also extended our forecast period by a further two years in order to provide further guidance in respect of our longer term plans. | | Summary Budget Deficit

|

Summary Budget

(Millions of Dollars)

| | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | |

| | | 2017/18

Forecast | | 2018/19

Budget | | 2019/20

Projection | | 2020/21

Projection | | 2021/22

Projection |

| | | | | |

Revenue | | | 16,128 | | | | 16,787 | | | | 17,095 | | | | 17,243 | | | | 17,593 | |

| | | | | |

Expenditure | | | 16,854 | | | | 17,423 | | | | 17,598 | | | | 17,638 | | | | 17,850 | |

| | | | | |

Year-End Adjustments/Lapse | | | – | | | | (115 | ) | | | (115 | ) | | | (115 | ) | | | (115 | ) |

| | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | |

| | | | | |

Net Income (Loss) | | | (726 | ) | | | (521 | ) | | | (388 | ) | | | (280 | ) | | | (142 | ) |

| | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | |

Core Government

(Millions of Dollars)

| | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | |

| | | 2017/18

Forecast | | 2018/19

Budget | | 2019/20

Projection | | 2020/21

Projection | | 2021/22

Projection |

| | | | | |

Revenue | | | 12,945 | | | | 13,546 | | | | 13,898 | | | | 13,989 | | | | 14,302 | |

| | | | | |

Expenditure | | | 13,710 | | | | 14,170 | | | | 14,306 | | | | 14,306 | | | | 14,478 | |

| | | | | |

Year-End Adjustments/Lapse | | | – | | | | (35 | ) | | | (35 | ) | | | (35 | ) | | | (35 | ) |

| | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | |

| | | | | |

Net Result | | | (765 | ) | | | (589 | ) | | | (373 | ) | | | (282 | ) | | | (141 | ) |

| | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | |

| | | | | |

Fiscal Stabilization Account Transfer | | | (10 | ) | | | (50 | ) | | | (50 | ) | | | (50 | ) | | | (50 | ) |

| | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | |

| | | | | |

Net Income (Loss) | | | (775 | ) | | | (639 | ) | | | (423 | ) | | | (332 | ) | | | (191 | ) |

| | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | |

Fiscal Stablization Account

Through transfers to the Fiscal Stabilization Account, we are also steadily replenishing the Province’s savings that were previously drawn down – even when the economy was strong and revenue was growing.

Restoring Credit Rating

Credit rating agencies downgraded Manitoba last year, citing the past financial mismanagement of the Province’s affairs. In fact, there were three downgrades in a space of three years. Downgrades put the entire sustainability of the province at risk, and can cost us millions of dollars in higher borrowing costs. While the path to restore our credit ratings will need to be over the course of successive responsible budgets (there are no quick fixes), we are bending the curve. By introducing responsible budgets and deliberately executing them, we have worked to arrest this alarming trend.

Debt to GDP

Looking to Budget 2019

We have already commenced work for building Budget 2019. We are starting our budgeting process earlier than ever before, and our efforts will be well underway by the summer. Next year’s budget process will also continue with the ongoing priorities of refining tax credits and reviewing our tax systems.

The Storm Clouds we have seen are real – we will remain on high vigilance. We are seeking ways to reduce volatility in our summary budget – for example by reviewing the past accounting policies taken in respect of entities like Workers Compensation Board, where there may be ways for better budgeting practices across summary government. In the meanwhile, we will continue our work in finding better value for money and more cost effective outcomes, while reducing Manitobans’ excessive tax burden and bringing the summary budget into balance.

Budget Paper A

ECONOMIC REVIEW AND OUTLOOK

ECONOMIC REVIEW AND OUTLOOK

CONTENTS

| | | | |

OVERVIEW | | | A1 | |

| |

INTERNATIONAL ECONOMIC DEVELOPMENTS | | | A2 | |

| |

THE CANADIAN ECONOMIC DEVELOPMENTS | | | A4 | |

| |

MANITOBA ECONOMY | | | A5 | |

| |

MANITOBA OUTLOOK | | | A18 | |

| |

CHANGING ECONOMIC AND FISCAL LANDSCAPE | | | A20 | |

| |

MANITOBA FINANCE SURVEY OF ECONOMIC FORECASTS 2017f–2019f | | | A23 | |

| | |

| | B U D G E T 2 0 1 8 E c o n o m i c R e v i e w a n d O u t l o o k / A 1 |

OVERVIEW

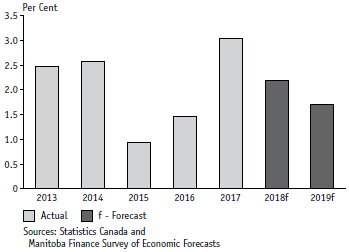

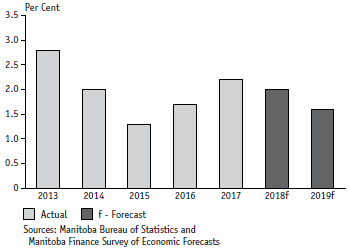

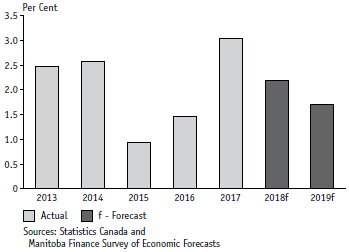

Manitoba’s economic performance indicators show an improvement in growth, which began in 2016 and strengthened in the first half of 2017. Most key indicators reveal a sharp acceleration in economic activity in 2017 compared to the two previous years.

| | |

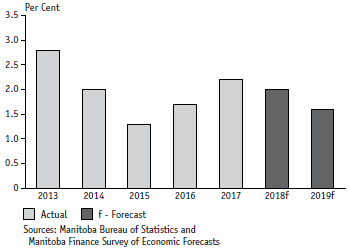

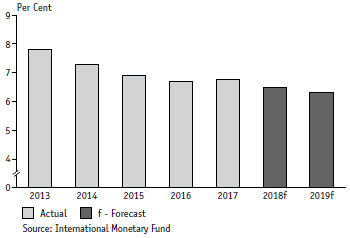

Manitoba Real GDP Growth, 2013–2019f

| | This momentum in economic growth is attributed to a number of factors. Stable commodity prices are supporting a recovery in national and international exports of goods and services. Strong provincial population growth is maintaining confidence and boosting capital spending on residential, commercial and industrial properties in Manitoba. Record harvest of grains and oilseeds is lifting output in agriculture and in a number of other supporting sectors. As well, Manitoba hosted the 2017 Canada Summer Games in Winnipeg. This provided an additional lift to domestic spending as spectator sports, performing arts, restaurants, accommodation and transportation facilities provided services for hundreds of visiting athletes, their families and spectators. |

Offsetting these gains were developments in Manitoba’s mining and oil extraction sector. Weak market fundamentals and depletion of reserves in certain sections of existing mines are lowering production and jobs in the sector. While further consolidation is expected in 2018 and 2019, activity could quickly turn around if prices surge, or exploration and technology reveal new finds or cost-efficient ways to extract natural resources.

As the impact from one-time transitory factors and commodity price recovery-fueled stimulus diminish, economic growth is expected to slow over the medium term. Some indicators, including employment, point to a slower pace of growth in the latter half of 2017. Similarly, several major projects completing or winding down are expected to slow the pace of capital spending in the near term.

The broad and sustained increase in global demand is expected to support Manitoba’s exports and business investment in manufacturing and wholesale capacity, while growth in population and jobs will continue to lift domestic spending. In addition, stable government infrastructure spending will add to growth.

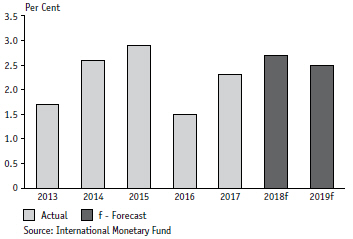

According to the Manitoba Bureau of Statistics, real GDP growth in Manitoba improved from a low of 1.3% in 2015 to 2.2% in 2017. The Manitoba Finance Survey of Economic Forecasts indicates 2.0% growth in 2018 and 1.6% growth in 2019. This compares to 2.3% and 1.8% growth forecast for Canada in 2018 and 2019, respectively.

The general economic outlook is subject to considerable risks associated with the ongoing North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) renegotiations and higher interest rates. Federal measures to cool the housing market are elevating concerns of their impact on Manitoba’s relatively balanced housing market. In addition, corporate and

| | |

A 2 / E c o n o m i c R e v i e w a n d O u t l o o k B U D G E T 2 0 1 8 | | |

personal tax rate changes in the U.S. and Canada are placing a spotlight on global tax competitiveness. This could cause a measurable behavioural response by businesses and households.

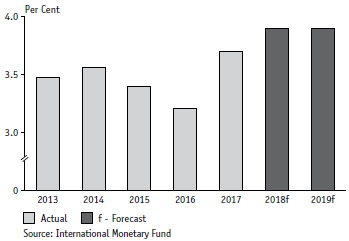

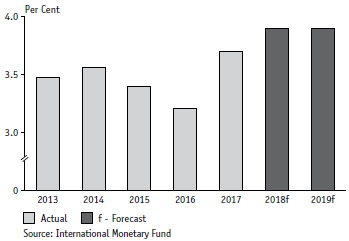

INTERNATIONAL ECONOMIC DEVELOPMENTS

In 2017, after several years of below average growth, the global economy turned a corner. This global growth is broad-based as evidenced by the International Monetary Fund (IMF) highlighting positive year-over-year growth in 120 countries around the world, representing 75% of the global economic output, the best broad-based expansion since 2010.

| | |

Global Real GDP Growth, 2013–2019f

| | Citing tax cuts and infrastructure spending, the IMF upgraded U.S. economic growth by 0.4% to 2.7% in 2018 and by 0.6% to 2.5% in 2019. The strengthening recovery in the Eurozone and Japan is also cause for greater optimism. Progress in structural reforms in key Emerging Market Economies (EMEs), along with a gradual increase in commodity prices, should keep growth in emerging markets resilient and buoyant. Considering these factors, the IMF increased its global economic forecasts for 2018 and 2019. The global economy is expected to grow by 3.9% in 2018 and 2019, 0.2% higher for both years compared to its previous forecast and the highest growth since 2011. |

Advanced economies are expected to grow by 2.3% in 2018 and 2.2% in 2019, up 0.3% and 0.4% higher compared to earlier projections. EMEs are forecast to grow solidly at rates of 4.9% and 5.0% in 2018 and 2019, respectively.

While there is optimism and confidence coming from the expansion in global trade that is currently taking root, a considerable amount of risk clouds the outlook. Prolonged uncertainty on long-standing free trade agreements like NAFTA and United Kingdom’s membership in the European Union (EU) is weighing down investment spending and productivity. Government, business and household indebtedness is stretched and increasingly sensitive to further interest rate increases.

Furthermore, as is always the case, unexpected international trade frictions can quickly derail the expansion in global trade, while a wider rise in geopolitical tensions could increase volatility in financial and commodity markets.

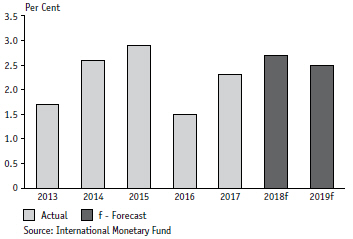

U.S.

The U.S. is Manitoba’s largest international market, accounting for 65% of merchandise exports in 2017. The pace of economic growth in the U.S. significantly picked up, during the last three quarters of 2017, averaging 2.9%, close to its historical norm of 3.1%. U.S. labour markets have tightened and the unemployment rate has fallen to 4.1%,

| | |

| | B U D G E T 2 0 1 8 E c o n o m i c R e v i e w a n d O u t l o o k / A 3 |

| | |

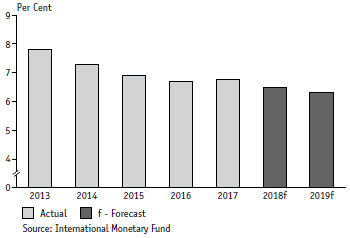

the lowest since January 2001. Average hourly earnings grew by a noticeably higher than expected 2.9% year-over-year increase in January. Recently, the higher than expected increase in earnings stoked concerns of inflation, leading to a sharp increase in bond yields and financial market volatility. Other factors that are fueling higher inflation expectation and a corresponding rise in borrowing costs include a positive momentum in the economy, large personal and corporate income tax cuts, and the proposed $1.5 trillion infrastructure plan. If providing stimulus in an already tight labor market leads to a substantial increase in inflation and higher interest rates, some of the boost to economic growth will be lost. On the other hand, increased U.S. demand could further support rising global demand and trade. | | U.S. Real GDP Growth, 2013–2019f

|

China

| | |

China is Manitoba’s second-largest global trading partner, accounting for 10.1% of total international merchandise trade in 2017. The Chinese economy is continuing its transition from investment and exports to consumer spending and services. The steady growth in the share of services to over half of the Chinese economy and accelerating consumer spending are indicative of the progress being made in rebalancing the economy. Significant headway in reforms in areas such as restructuring State-Owned Enterprises point to a more balanced and durable economic growth ahead. High indebtedness, especially at the sub-sovereign level and trade frictions between China and the U.S. are near term concerns. China, however, has monetary and fiscal policy space at the central government (federal) level to balance some of the risks. | | China Real GDP Growth, 2013–2019f

|

| | |

A 4 / E c o n o m i c R e v i e w a n d O u t l o o k B U D G E T 2 0 1 8 | | |

Japan

Japan is Manitoba’s third-largest overseas market with a 5.9% market share of international merchandise sales in 2017. Should a new Trans-Pacific Partnership agreement be reached, it would increase Manitoba’s trade with Japan and with the Asia-Pacific region.

Japan posted eight consecutive quarters of positive economic growth. Earnings growth is key to Japan’s economic recovery as consumer spending accounts for roughly 60% of the economy. Wages have improved and are likely to boost consumer spending going forward. Business investment is also picking up.

Interest rates are low in Japan and should be supportive of consumer spending and business investment. Government spending on infrastructure to host the 2020 Olympics will add to the economic momentum. As the global economy strengthens, Japanese exports to the rest of the world are also picking up. Despite the Bank of Japan’s accommodative policies, deflationary pressures remain.

Eurozone

The EU, which includes the Eurozone (countries using the euro as their currency), has the potential of becoming a significant trading partner of the province, with the Canada-European Union Comprehensive Economic and Trade Agreement (CETA) coming into force last September. The EU accounted for 4.3% of Manitoba’s total international merchandise exports.

Eurozone, buoyed by low energy prices, low interest rates and increasing exports, posted its best economic growth since the recovery began almost a decade ago. Consumer spending led the recovery and is expected to stay buoyant this year with steady gains in employment, rising wages and low interest rates. Exports should continue to grow with strengthening global demand. A tightening in production capacity should spur business investment spending in 2018.

THE CANADIAN ECONOMIC DEVELOPMENTS

The Canadian economy emerged from a year and a half of weak growth conditions at the end of 2016 and posted 3.0% real GDP growth in 2017, the highest among the G7 and more than twice the rate of 1.4% recorded in 2016.

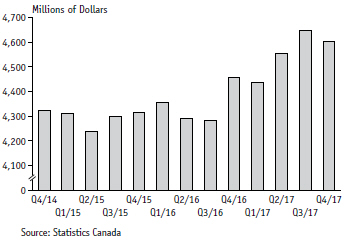

The rebound was led by consumer spending, which increased by 3.5% in 2017, the largest increase since 2010. Business capital spending turned around and posted its first increase in three years. Growth in exports remained relatively steady, increasing by 1.0% both in 2017 and in 2016. Reflecting the strength in consumer and business spending, imports increased by 3.6%, the highest growth since 2011.

The acceleration in economic activity added 336,500 jobs in 2017, the best annual increase since the Great Recession. Quality of jobs materially improved. Roughly five out of six jobs were full-time and seven out of ten were in the private sector. Furthermore, the number of hours worked advanced 1.4% in 2017 compared to a gain of 0.8% in 2016. Average weekly earnings – a key driver of consumer spending – rebounded in 2017, increasing by 2.0% compared to a gain of 0.4% in 2016.

Despite a strong annual result for GDP growth in 2017, quarterly national economic accounts reveal a slower pace in the second half of the year. The deceleration was broad based among spending categories and indicates a leveling of demand following the transitory boost from an upturn in capital investment, low energy prices and from

| | |

| | B U D G E T 2 0 1 8 E c o n o m i c R e v i e w a n d O u t l o o k / A 5 |

larger Canada Child Benefit (CCB) transfers to households.

The current outlook factors in a slower pace of growth. After a lift from the CCB transfers and robust employment gains, consumer spending, which accounts for 57% of all expenditure in Canada, is expected to slow as interest rates continue to increase.

Strengthening global demand is expected to lift export sales and business investment in Canada, partially offsetting the weakness from the household sector. As a result, the Canadian economy is forecast to slow to 2.3% this year and to 1.8% in 2019. Nominal GDP is expected to increase by 4.1% in 2018 and 3.8% in 2019.

Economic and fiscal developments currently unfolding can materially change the outlook.

Canada Real GDP Growth,

2013–2019f

The uncertainty surrounding NAFTA, a trade deal that has been in place for almost a quarter of a century, can slow and discourage actual and planned investments in Canada. Major tax reforms in the U.S. and recent federal tax changes in Canada increase flight risks for capital, businesses and skilled workers from jurisdiction to jurisdiction.

Recent increases in interest rates, and the Bank of Canada’s (BoC) signal to move rates even higher, could reduce overall spending in the economy by more than expected. With relatively low interest rates in the past decade, a sensitivity to higher rates and higher debt servicing costs will be tested with each interest rate increase.

At the national level, consumers seem to be the most vulnerable to a downturn as they continue to add to household debt. The latest figures show the average Canadian household debt-to-disposable income at a record 172.1% in 2017. However, the BoC does have the flexibility to adjust interest rates down, as it did during the Great Recession and after the commodity price collapse in 2015.

A positive outcome on NAFTA combined with very accommodative U.S. tax cuts and infrastructure plan could boost capital investment and job creation in Canada. In addition, an acceleration in the broad based expansion in global trade could lift commodity prices and Canadian exports above current expectations.

MANITOBA ECONOMY

The Manitoba economy generates relatively stable annual economic growth over time, even during periods of increased volatility in financial and commodity markets. Over the long-term, the province maintained consistent average annual growth in most key economic indicators, including real GDP, employment and manufacturing sales when compared to other provinces.

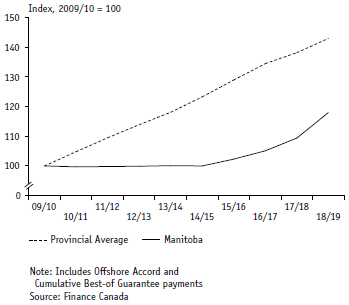

Even with increased volatility, the trend in Manitoba’s 10-year average annual real GDP growth has been relatively stable over the last 15 years, while the national average has declined. The province surpassed the national average 10-year growth trend in 2009 and was the second highest among provinces in 2016.

| | |

A 6 / E c o n o m i c R e v i e w a n d O u t l o o k B U D G E T 2 0 1 8 | | |

Manitoba has been successful in attracting a record number of skilled workers, entrepreneurs and their families to the province. This has resulted in the province recording the fastest rate of population growth among provinces in the last three years. In 2017, the working age population exceeded 1,000,000 persons for the first time in Manitoba’s history. Moreover, population growth is providing confidence for investing in productive capacity and expanding domestic demand.

Also, in 2017, Manitoba posted a record level of capital investment in residential and non-residential buildings in the province. The number of housing starts were the highest level since 1987.

A number of other key performance indicators showed significant improvement in 2017:

| ● | | Total employment increased by 10,500 workers, the largest gain in 15 years. |

| ● | | Private sector jobs increased by 11,800 workers, the largest gain in 15 years. |

| ● | | Second-highest increase in average weekly earnings among provinces and the highest since 2014. |

| ● | | Labour income growth improved to 4.7% in 2017, compared to 0.8% in 2016. |

| ● | | Manufacturing sales increased by 5.3%, the best in six years. |

| ● | | Wholesale merchandise sales increased by 7.4%, the best since 2014. |

| ● | | Motor vehicle sales increased by 10.1%, the best in 15 years. |

| ● | | Truck and SUV sales increased by 15.4%, the best in 20 years. |

| ● | | Exports to Non-U.S. markets increased by 13.0%, the best in six years. |

| ● | | Manitoba crop farmers reported a record volume of harvest (bushels) in 2017. |

| ● | | Total farm cash receipts surpassed $6.5 billion in 2017, the highest ever in Manitoba. |

| ● | | Highest number of births since 1972. |

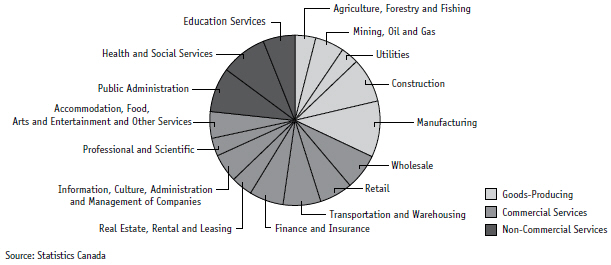

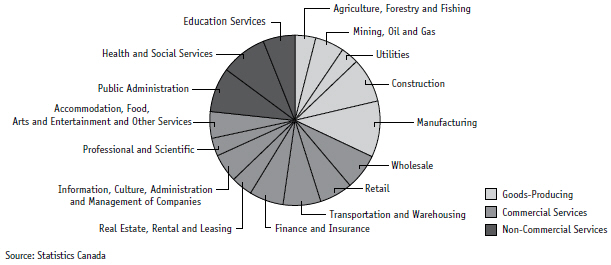

Manitoba GDP By Industry Shares, 2016

| | |

| | B U D G E T 2 0 1 8 E c o n o m i c R e v i e w a n d O u t l o o k / A 7 |

Reflecting this momentum, real GDP growth increased to 2.2% in 2017, up from 1.7% in 2016 and 1.3% in 2015. As some of the boost from transitory factors and prior commodity price shock ease, economic activity is expected to moderate to a sustainable pace going forward in Canada and in Manitoba.

The Manitoba economy will continue to benefit from a broad and balanced mix of medium-sized sectors. With the range in contribution from the smallest to largest sector being the narrowest among provincial economies, no single industry dominates overall production and jobs.

The strength of the Manitoba economy is not limited to its diverse economic base. Centrally located in North America, the province has a recognized and extensive manufacturing, wholesale trade, transportation and warehousing network that produces and distributes raw commodities and goods and services across Canada and globally. Almost half of the provincial exports are destined for foreign markets while the other half are destined for Canadian provincial markets. This distribution is the most balanced among provinces.

Diversity in markets and production lowers Manitoba’s foreign trade exposure for domestically produced goods and services as well as jobs. Furthermore, the mix of primary commodities, processed products and services contained in provincial exports reduces Manitoba’s overall supply chain dependence on imported items that are embodied in exports.

In this Economic Review and Outlook Report, annual, quarterly and monthly economic statistics are on a calendar year basis. These statistics are often revised and can change the assessment of economic performance over time.

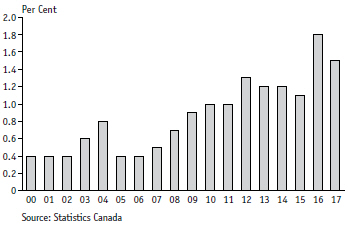

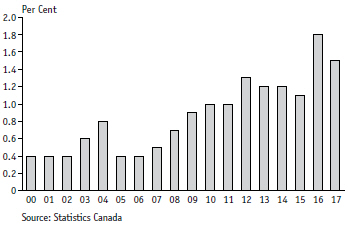

Population

Manitoba’s population was estimated at 1,338,109 persons in 2017, an annual increase of 19,994 persons or 1.5%. This follows a record annual increase of 22,693 persons or 1.8% in 2016.

In the past decade, population increased by 1.2% annually, 50% higher than the long-term average rate of 0.8%. In the last three years, Manitoba showed the fastest population growth among provinces, averaging 1.5% annual growth, well above the national average of 1.1%.

Most of this growth is due to a concerted effort by the Manitoba Provincial Nominee Program (MPNP) to use immigration to recruit for labour market and entrepreneurial needs. The MPNP is an economic immigration program designed to attract job-ready skilled workers and active investors. It has been an important part of the immigration system since 1998.

The renewal of the MPNP is streamlining the application process to achieve better and quicker outcomes. It has already reduced application-processing time to under six-months and it has eliminated the $100,000 deposit previously required from business investors.

Manitoba’s Annual Population Growth,

2000–2017

| | |

A 8 / E c o n o m i c R e v i e w a n d O u t l o o k B U D G E T 2 0 1 8 | | |

Recent enhancements will make it easier for international students with a Manitoba education to build careers and settle in the province. Priority will be given to business investors who start a business within the first 12 months of their arrival in Manitoba, particularly those who start a business outside of Winnipeg. For skilled workers, priority will be given to candidates with close family connections in Manitoba and spouses who have the language proficiency, training and experience to quickly find in-demand jobs.

In addition to immigration, population growth has been increasingly supported by the natural rate of increase. Given a younger demographic arriving through immigration and the echo boom cohort maturing into the prime child rearing age, the number of births has increased to noteworthy levels. From a low of 13,764 births in 2001/02, the number of births has increased to a record 17,641 births in 2016/17.

As the proportion of younger people increase, the median age has declined, making Manitoba’s overall population age younger. The median population age peaked at 37.8 years from 2008 to 2013 and has since declined. In 2017, the median age fell to 37.4 years, the third lowest among provinces and below Canada (40.6 years).

The demographic dynamics are reflected in the labour market. Since 1990, Manitoba once again has the majority of the working age population in 20 to 29 year age cohort, surpassing the 50 to 59 year age cohort in 2016. The second-largest working age cohort is aged 30 to 39 years.

In addition, Manitoba has a proportionally higher share of youth in the population compared to other provinces. As a result, the labour supply is expected to continue to increase over the medium term.

Labour Market

Displaying the smallest swings in annual average growth, Manitoba’s labour market is the most stable in Canada. It reflects a balance in supply and demand, with employment and labour force growing at a steady 1.0% annual pace since 1976.

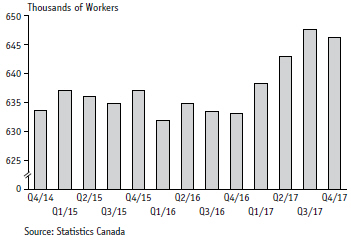

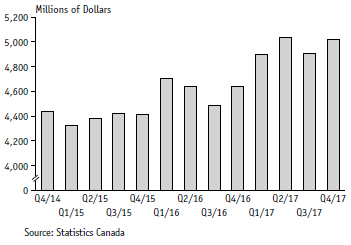

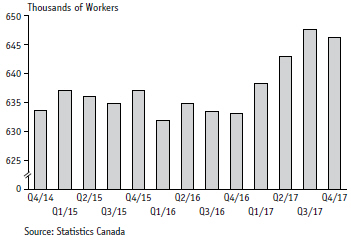

Manitoba’s Employment Level, Quarterly Average Fourth Quarter 2014–Fourth Quarter 2017

The labour market has shown resilience in absorbing a record increase in population, while maintaining the second-lowest unemployment rate and the third-highest labour force participation rate in Canada.

Last year was an exceptional year for Manitoba’s labour market. The number of working age Manitobans surpassed 1,000,000 individuals for the first time. The number of jobs increased by 10,500, the largest gain in 15 years. An average of 644,100 workers were employed during the year, the highest ever.

Most of the employment growth was due to full-time jobs, which increased by 9,200 or 1.8%. Part-time employment increased by 1,300 workers, or 1.1%. Youth employment increased

| | |

| | B U D G E T 2 0 1 8 E c o n o m i c R e v i e w a n d O u t l o o k / A 9 |

by 2,200 jobs, the first increase in three years and the largest increase in 11 years. Employment growth in the private sector was exceptionally strong and rose by 11,800 workers, or 2.5%. This was the largest increase in private sector jobs in 15 years.

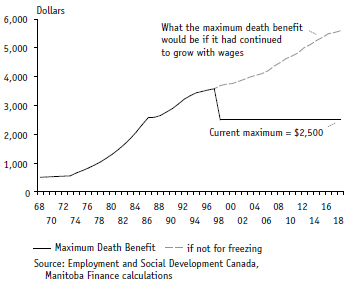

The strong growth in jobs reduced the number of unemployed by 4,600 workers, the largest annual reduction in the number of unemployed since 1998. It also cut the unemployment rate for 2017 to 5.4% from 6.1% in 2016.