Exhibit 99.1

Province of Nova Scotia

(Canada)

| | |

| | This description of the Province of Nova Scotia is dated as of December 11, 2017, and appears as Exhibit (1) to the Province of Nova Scotia’s Annual Report on Form 18-K to the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission for the fiscal year ended March 31, 2017. |

This document (otherwise than as a prospectus contained in a registration statement filed under the Securities Act of 1933) does not constitute an offer to sell or the solicitation of an offer to buy any Securities of the Province of Nova Scotia. The delivery of this document at any time does not imply that the information herein is correct as of any time subsequent to its date.

TABLE OF CONTENTS

| | | | |

| | | Page | |

Further Information | | | 2 | |

Forward-Looking Statements | | | 3 | |

Summary | | | 4 | |

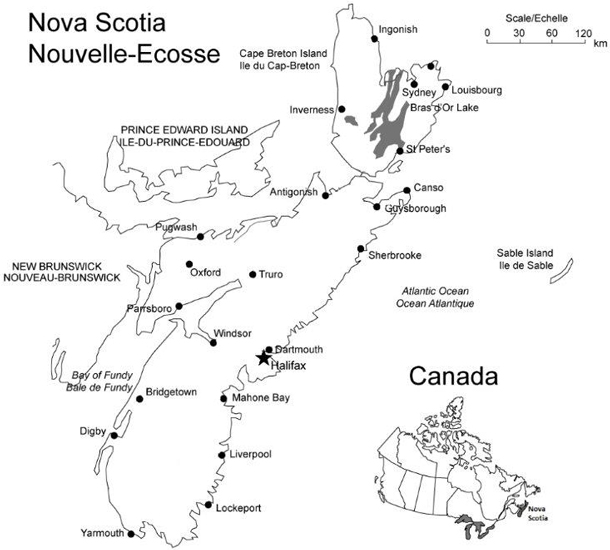

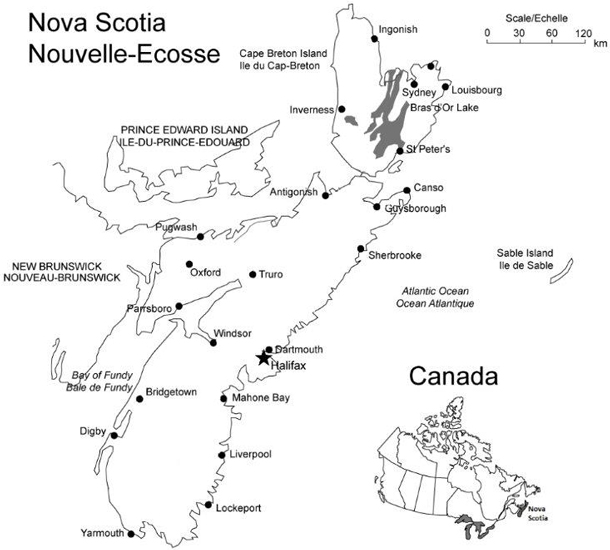

Map of Nova Scotia | | | 5 | |

Introduction | | | | |

Overview | | | 6 | |

Political System | | | 6 | |

Constitutional Framework | | | 6 | |

Economy | | | | |

Principal Economic Indicators | | | 8 | |

Recent Developments | | | 10 | |

Economic Structure | | | 11 | |

Population and Labor Force | | | 12 | |

Income and Prices | | | 14 | |

Capital Expenditures | | | 15 | |

Goods Producing Industries | | | 16 | |

Exports | | | 18 | |

Service Sector | | | 22 | |

Energy | | | 23 | |

Government Finance | | | | |

Overview | | | 26 | |

Specific Accounting Policies | | | 26 | |

Summary of Budget Transactions and Borrowing Requirements | | | 29 | |

Revenue | | | 30 | |

Program Expenditures/Expenses | | | 35 | |

Loans and Investments | | | 38 | |

| | | | |

| | | Page | |

Provincial Debt | | | | |

Funded Debt | | | 39 | |

Derivative Financial Instruments | | | 40 | |

Debt Maturities and Sinking Funds | | | 40 | |

Current Liabilities | | | 43 | |

Guaranteed Debt | | | 43 | |

Pension Funds | | | 44 | |

Public Sector Debt | | | | |

Public Sector Funded Debt | | | 47 | |

Certain Crown Corporations and Agencies | | | | |

Sydney Steel Corporation and Sydney Tar Ponds Agency | | | 48 | |

Nova Scotia Municipal Finance Corporation | | | 48 | |

Nova Scotia Power Finance Corporation | | | 48 | |

Foreign Exchange | | | 49 | |

Official Statements | | | | |

Table 1 – Statement of Debentures Outstanding | | | 51 | |

FURTHER INFORMATION

This document appears as an exhibit to the Province of Nova Scotia’s Annual Report to the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission (“SEC”) on the Form 18-K for the fiscal year ended March 31, 2017. Additional information with respect to the Province of Nova Scotia is available in such Annual Report, the other exhibits to such Annual Report, and in amendments thereto. Such Annual Report, exhibits and amendments can be inspected and copied at the public reference facility maintained by the SEC at: 100 F Street, NE, Washington, D.C. 20549. Copies of such documents may also be obtained at prescribed rates from the Public Reference Section of the Commission at its Washington address or, without charge, from Province of Nova Scotia, Department of Finance & Treasury Board, Deputy Minister of Finance & Treasury Board, PO Box 187, 7th Floor, 1723 Hollis Street, Halifax, Nova Scotia, Canada, B3J 2N3.

The SEC maintains an Internet site that contains reports, statements and other information regarding issuers that file electronically with the SEC. The address for the SEC’s Internet site is http://www.sec.gov.

In this document, unless otherwise specified or the context otherwise requires, all dollar amounts are expressed in Canadian dollars. On December 8, 2017, the noon spot rate for the U.S. dollar in Canada, as reported by the Bank of Canada, expressed in Canadian dollars, and was $1.2860. See “Foreign Exchange” for information regarding the rates of conversion of U.S. dollars and other foreign currencies into Canadian dollars. The fiscal year of the Province of Nova Scotia ends March 31. “Fiscal 2017” and “2016-2017” refers to the fiscal year ending March 31, 2017, and unless otherwise indicated, “2016” means the calendar year ended December 31, 2016. Other fiscal and calendar years are referred to in a corresponding manner. Any discrepancies between the amounts listed and their totals in the tables set forth in this document are due to rounding.

2

FORWARD-LOOKING STATEMENTS

This exhibit includes forward-looking statements. The Province of Nova Scotia has based these forward-looking statements on its current expectations and projections about future events. These forward-looking statements are subject to risks, uncertainties, and assumptions about the Province of Nova Scotia, including, among other things:

| | • | | the Province of Nova Scotia’s economic and political trends; and |

| | • | | the Province of Nova Scotia’s ability to control expenses and maintain revenues. |

In light of these risks, uncertainties and assumptions, the forward-looking events discussed in this annual report might not occur.

3

SUMMARY

The information below is qualified in its entirety by the detailed information provided elsewhere in this document.

PROVINCE OF NOVA SCOTIA

| | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | |

| Economy | | Year Ended December 31 | |

| | | 2012 | | | 2013 | | | 2014 | | | 2015 | | | 2016 | |

| | | (in millions unless otherwise indicated) | |

Gross Domestic Product at Market Prices | | $ | 37,836 | | | $ | 38,615 | | | $ | 39,739 | | | $ | 40,580 | | | $ | 41,726 | |

Household Income. | | | 36,686 | | | | 37,690 | | | | 38,603 | | | | 39,791 | | | | 40,813 | |

Capital Expenditures(1) | | | 3,598.4 | | | | 3,575.4 | | | | 3,423.4 | | | | 3,467.2 | | | | 3,862.0 | |

Annual Increase in Consumer Price Index | | | 2.0% | | | | 1.2% | | | | 1.7% | | | | 0.4% | | | | 1.2% | |

Population by July 1 (in thousands) | | | 944.9 | | | | 943.0 | | | | 942.2 | | | | 941.5 | | | | 948.6 | |

Unemployment Rate | | | 9.1% | | | | 9.1% | | | | 9.0% | | | | 8.6% | | | | 8.3% | |

| |

| Revenues and Expenses – Consolidated Entity | | Fiscal Year Ended March 31 | |

| | | 2013 | | | 2014 | | | 2015 | | | 2016 | | | 2017 | |

| | | (in millions) | |

Revenues | | $ | 9,749.8 | | | $ | 9,708.9 | | | $ | 10,310.5 | | | $ | 10,549.8 | | | $ | 10,833.7 | |

Current Expenses | | | 10,407.8 | | | | 10,737.1 | | | | 10,805.6 | | | | 10,950.8 | | | | 11,078.7 | |

| | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | |

Surplus (Deficit) from Governmental Units | | | (658.0 | ) | | | (1,028.1 | ) | | | (495.1 | ) | | | (401.0 | ) | | | (245.0 | ) |

Net Income from Government Business Enterprises | | | 354.4 | | | | 351.3 | | | | 351.4 | | | | 387.8 | | | | 394.6 | |

| | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | |

Provincial Surplus/(Deficit) | | ($ | 303.6 | ) | | ($ | 676.9 | ) | | ($ | 143.7 | ) | | ($ | 13.2 | ) | | $ | 149.6 | |

| | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | |

| |

| Public Sector Funded Debt | | As at March 31 | |

| | | 2013 | | | 2014 | | | 2015 | | | 2016 | | | 2017 | |

| | | (in millions unless otherwise indicated) | |

General Revenue Fund Funded Debt | | $ | 15,350.0 | | | $ | 15,323.4 | | | $ | 15,925.5 | | | $ | 15,942.1 | | | $ | 15,639.4 | |

Miscellaneous Debt | | | 11.3 | | | | 9.5 | | | | 8.0 | | | | 10.1 | | | | 10.0 | |

Sub Total | | | 15,361.3 | | | | 15,332.9 | | | | 15,933.5 | | | | 15,952.3 | | | | 15,649.4 | |

| | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | |

Total Guaranteed Debt | | | 143.3 | | | | 138.6 | | | | 124.0 | | | | 118.3 | | | | 98.1 | |

Total Consolidated Entity Funded Debt | | | 15,504.6 | | | | 15,471.5 | | | | 16,057.5 | | | | 16,070.5 | | | | 15,747.5 | |

| | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | |

Less: Sinking Funds, Public Debt Management Fund | | | 2,694.2 | | | | 2,531.1 | | | | 2,675.8 | | | | 2,595.8 | | | | 2,712.5 | |

| | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | |

Net Public Sector Funded Debt | | $ | 12,810.4 | | | $ | 12,940.4 | | | $ | 13,381.7 | | | $ | 13,474.8 | | | $ | 13,035.0 | |

| | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | |

Per Capita ($) | | $ | 13,557.4 | | | $ | 13,721.9 | | | $ | 14,202.5 | | | $ | 14,311.3 | | | $ | 13,741.0 | |

As a Percentage of: | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | |

Household Income(2) | | | 34.9% | | | | 34.3% | | | | 34.7% | | | | 33.9% | | | | 31.9% | |

Gross Domestic Product at Current Market Prices | | | 33.9% | | | | 33.5% | | | | 33.7% | | | | 33.2% | | | | 31.2% | |

| (1) | Methodology used to calculate Capital Expenditures was revised in 2015 and adjusted for all included periods. Housing has been excluded in the new methodology since the primary goal of the program is to publish capital expenditures made by private- and public-sector organization. |

| (2) | Population as of July 1 of the preceding calendar year Household Income (Personal Income has been replaced with Household Income by Statistics Canada, the concepts are similar) and Gross Domestic Product at market prices are for the previous calendar year. |

4

5

INTRODUCTION

Overview

The Province of Nova Scotia (“Nova Scotia” or the “Province”) is the most populous of the four Atlantic Provinces of Canada (“Atlantic Canada”) and covers 20,402 square miles. It extends 360 miles in length and varies in width from 50 miles to 105 miles.

According to estimates issued by Statistics Canada, the population of Nova Scotia was 953.9 thousand as of July 1, 2017, and represented 2.6% of Canada’s population of 36.7 million. The largest urban concentration in Atlantic Canada is the Halifax Regional Municipality (“Halifax”). Halifax Census Metropolitan Area, situated centrally on the Atlantic coast of the Province, had a population of 425,871 as of July 1, 2016. Halifax, the capital of Nova Scotia, is the commercial, governmental, educational, and financial center of the Province, and is also the location of an important naval base. The Government of Canada also has an extensive shipbuilding project in Halifax that started in 2013.

Political System

The Legislature of Nova Scotia consists of the Lieutenant Governor and the Nova Scotia House of Assembly. The Nova Scotia House of Assembly is elected by the people for a term not to exceed five years. The House of Assembly may be dissolved at any time by the Lieutenant Governor on the advice of the Premier of the Province, who is traditionally the leader of the majority party in the Nova Scotia House of Assembly.

The last provincial general election was held on May 30, 2017. The Liberal Party was elected to a majority government and holds 27 seats in the House of Assembly. The official opposition in the House of Assembly is the Progressive Conservative Party with 17 seats and the New Democratic Party holds 7 seats.

The executive power in the Province is vested in the Governor-in-Council, comprising the Lieutenant Governor acting on the advice of the Executive Council. The Executive Council is responsible to the House of Assembly. The Governor General of Canada in Council appoints the Lieutenant Governor, who is the representative of the Queen in the Province. Members of the Executive Council are appointed by the Lieutenant Governor, normally from members of the House of Assembly, on the nomination of the Premier.

The Parliament of Canada is composed of the Queen represented by the Governor General, the Senate, whose members are appointed by the Governor General upon the recommendation of the Prime Minister of Canada, and the House of Commons, whose members are elected by the people. The people of Nova Scotia are entitled to send 11 elected representatives to the 338-member House of Commons. Ten Senators represent Nova Scotia in the Senate.

There are three levels of courts in Nova Scotia; provincially appointed courts are grouped together, the Supreme Court and Court of Appeal. The Provincial Court is a court of record and every judge thereof has jurisdiction throughout the Province to exercise all the power and perform all the duties conferred or imposed on a judge of the Provincial Court. In addition to hearing matters relating to provincial statutes and municipal by-laws, the Provincial Court is specifically authorized to hear certain matters under the Criminal Code of Canada. The Supreme Court of Nova Scotia is a court of original jurisdiction and as such has jurisdiction in all cases, civil and criminal, arising in the Province except those matters or cases expressly excluded by statute. The Nova Scotia Court of Appeal is the general court of appeal in both civil and criminal matters.

Constitutional Framework

Similar to the British Constitution, the Constitution of Canada (the “Constitution”) is not contained in a single document, but consists of a number of statutes, orders, and conventions. Canada is a federation of ten provinces and three Federal territories, with a constitutional division of responsibilities between the Federal and provincial governments, as set forth in The Constitution Acts, 1867 to 1982. The Constitution Acts are divided into two fundamental documents. The Constitution Act, 1867 (formerly the British North America Act, 1867), provides for the federation of British North America provinces, and the Constitution Act, 1982 (the “1982 Act”), enacted by the parliament of the United Kingdom, provides, among other things, that amendments to the Constitution be effected in Canada according to terms of an amending formula.

6

The 1982 Act also includes a Charter of Rights and Freedoms, which encompasses language rights, Aboriginal rights, principles of the reduction of regional economic disparities, and the making of fiscal equalization payments to the provinces by the Government of Canada, including an enumeration of other Acts and orders which are part of the Constitution.

Under the Constitution, each provincial government may exclusively make laws in relation to the following matters:

| | • | | municipal institutions; |

| | • | | property and civil rights; |

| | • | | forestry and non-renewable natural resources; |

| | • | | other matters of purely provincial or local concern; |

| | • | | raise revenue through direct taxation within its territorial limits; and |

| | • | | borrow monies on the credit of the province. |

The Federal Parliament of Canada is empowered to raise revenue by any system of taxation, and generally has jurisdiction over matters or subjects not assigned exclusively to the provincial legislatures. The Federal Parliament may exclusively make laws in relation to the following matters:

| | • | | the Federal public debt and property; |

| | • | | the borrowing of money on the public credit of Canada; |

| | • | | the regulation of trade and commerce; |

As a province of Canada, Nova Scotia could be affected by political events in another province. For instance, on September 7, 1995, the Government of Quebec presented a Bill to the National Assembly entitled An Act respecting the future of Quebec (the “Act”) that included, among others, provisions authorizing the National Assembly to proclaim the sovereignty of Quebec. The Act was to be enacted only following a favorable vote in a referendum. Such a referendum was held on October 30, 1995. The results were 49.4% in favor and 50.6% against.

In 1996, the Government of Canada, by way of reference to the Supreme Court of Canada (the “Supreme Court”), asked the court to determine the legality of a unilateral secession of the Province of Quebec from Canada, either under the Canadian Constitution or international law. On August 20, 1998, the Supreme Court of Canada ruled that the Province of Quebec did not have the unilateral right of secession, and that any proposal to secede authorized by a clear majority in response to a clear question in the referendum should be construed as a proposal to amend the Constitution, which would require negotiations. These negotiations would have to deal with a wide array of issues, such as the interest of the other provinces, the Federal Government, the Province of Quebec, and the rights of all Canadians both within and outside the Province of Quebec, and specifically, the rights of minorities, including Aboriginal peoples.

7

ECONOMY

Nova Scotia has a diversified economy. The geographic location of Nova Scotia, being surrounded almost completely by water with more than 4,598 miles of coastline, has significantly contributed to the economy. The importance of the sea to the economy is witnessed in many industries such as fishing and aquaculture, oil and gas, naval defense, shipbuilding, tourism, transportation and research.

While many of the goods and services producing industries are directly or indirectly related to the processing of Nova Scotia’s natural resources such as seafood products, pulp and paper products, and natural gas, the provincial economy is also diversified into information age technologies and other goods as diverse as motor vehicle tires and naval shipbuilding.

Export of goods are important to the economy of Nova Scotia as export of goods and services represents 36.9% of Nova Scotia’s GDP at market prices. Of international merchandise exports, approximately 69.0% are exported to the United States.

Nova Scotia’s economy features the general characteristics of developed economies. Nova Scotia’s service sector is disproportionately larger than that of Canada. This represents Nova Scotia’s long-established position as the principal private sector service center for Atlantic Canada and the center for regional public administration and defense.

Principal Economic Indicators

The economy of Nova Scotia is influenced by the economic situation of its principal trading partners in Canada and abroad, particularly the United States. In 2016, Nova Scotia’s gross domestic product (“GDP”) at market prices was $41.7 billion, or 2.0% of Canada’s GDP. Compared with the levels for 2015, real GDP at market prices in chained 2007 dollars for Nova Scotia increased by 0.8% while GDP in Canada increased by 1.4% in 2016. Total exports of goods and services from Nova Scotia, to international and inter-provincial destinations, in 2016 increased by 3.1%.

Manufacturing sales in 2016 increased by 4.2% for Nova Scotia compared to an increase of 1.2% for Canada.

8

The following table sets forth certain information about economic activity in Nova Scotia and, where provided, Canada, for the calendar years 2012 through 2016.

SELECTED ECONOMIC INFORMATION

| | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | |

| | | | | | Compound

Annual rate

of growth(1) | |

| | 2012 | | | 2013 | | | 2014 | | | 2015 | | | 2016 | | |

| | | (In millions of $ in current prices unless otherwise indicated) | | | | |

Gross Domestic Product (Nova Scotia) | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | |

At Market Prices(2) | | $ | 37,836 | | | $ | 38,615 | | | $ | 39,739 | | | $ | 40,580 | | | $ | 41,726 | | | | 2.5 | % |

Chained 2007 Dollars | | | 35,530 | | | | 35,483 | | | | 35,871 | | | | 36,356 | | | | 36,654 | | | | 0.8 | % |

GDP at Basic Prices (Chained 2007) | | | 32,116 | | | | 32,020 | | | | 32,347 | | | | 32,723 | | | | 33,066 | | | | 0.7 | % |

Gross Domestic Product (Canada) | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | |

At Market Prices(2) | | | 1,822,808 | | | | 1,897,531 | | | | 1,990,183 | | | | 1,994,911 | | | | 2,035,506 | | | | 2.8 | % |

Chained 2007 Dollars | | | 1,668,524 | | | | 1,709,821 | | | | 1,758,648 | | | | 1,776,251 | | | | 1,801,368 | | | | 1.9 | % |

Household Income (Nova Scotia) | | | 36,686 | | | | 37,690 | | | | 38,603 | | | | 39,791 | | | | 40,813 | | | | 2.7 | % |

Household Income ($ per capita) | | | 38,825.3 | | | | 39,968.2 | | | | 40,971.1 | | | | 42,263.4 | | | | 43,024.5 | | | | 2.6 | % |

Capital Expenditures(3) | | | 3,598.4 | | | | 3,575.4 | | | | 3,423.4 | | | | 3,467.2 | | | | 3,862.0 | | | | 1.8 | % |

Retail Trade. | | | 13,238.8 | | | | 13,663.0 | | | | 14,038.4 | | | | 14,062.8 | | | | 14,703.3 | | | | 2.7 | % |

Value of Manufacturing Sales | | | 10,459.8 | | | | 9,450.2 | | | | 7,347.1 | | | | 7,729.3 | | | | 8,052.7 | | | | -6.3 | % |

Unemployment Rate | | | 9.1 | % | | | 9.1 | % | | | 9.0 | % | | | 8.6 | % | | | 8.3 | % | | | | |

Annual Increase in Consumer Price Index: | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | |

Nova Scotia | | | 2.0 | % | | | 1.2 | % | | | 1.7 | % | | | 0.4 | % | | | 1.2 | % | | | | |

Canada | | | 1.5 | % | | | 0.9 | % | | | 2.0 | % | | | 1.1 | % | | | 1.4 | % | | | | |

| (1) | Compound annual rate of growth is computed by distributing the aggregate amount of growth during the period on the basis of a single annual rate of growth compounded annually. These rates are not adjusted for inflation unless otherwise indicated. |

| (2) | Gross Domestic Product (“GDP”) at market prices represents the value added by each of the factors of production plus indirect taxes less subsidies. GDP at Basic Prices represents the value added by each of the factors of production. |

| (3) | Methodology used to calculate Capital Expenditures was revised in 2015 for all periods listed. Housing has been excluded in the new methodology since the primary goal of the program is to publish capital expenditures made by private- and public-sector organization. |

Sources: Statistics Canada CANSIM Table 384-0037, 384-0038, 379-0030, 384-0042, 029-0045, 080-0020, 304-0015, 282-0002, and 326-0021.

9

Recent Developments

The following table sets forth the most recently available information with respect to certain economic indicators for Nova Scotia and Canada.

RECENT DEVELOPMENTS

| | | | | | | | | | | | |

| | | | | | Percentage Change, except where

noted | |

| | Period | | | Nova Scotia | | | Canada | |

Retail Trade (1) | |

| Jan. – Sep. 2017/

Jan. – Sep. 2016 |

| | | 6.4 | % | | | 6.8 | % |

Manufacturing Sales (1) | |

| Jan. – Aug. 2017/

Jan. – Aug. 2016 |

| | | 2.5 | % | | | 6.4 | % |

Housing Starts (all areas) (2) | |

| Jan. – Oct. 2017/

Jan. – Oct. 2016 |

| | | 18.7 | % | | | 8.7 | % |

Employment Growth (3) | |

| Jan. – Oct. 2017/

Jan. – Oct. 2016 |

| | | 0.7 | % | | | 1.8 | % |

Unemployment Rate (3) | | | Jan. – Oct. 2017 | | | | 8.4 | % | | | 6.5 | % |

Consumer Price Index | |

| Jan. – Oct. 2017/

Jan. – Oct. 2016 |

| | | 1.0 | % | | | 1.5 | % |

| (2) | These figures represent residential housing starts in both urban and rural areas, seasonally adjusted at annual rates. |

| (3) | These figures reflect the seasonally adjusted rate of unemployment. |

Sources: Statistics Canada, CANSIM Tables 080-0020, 304-0014, 304-0015, 027-0008, 282-0087, and 326-0020.

10

Economic Structure

Nova Scotia’s economy features the general characteristics of developed economies. Nova Scotia’s service sector is disproportionately larger than that of Canada. This represents Nova Scotia’s long-established position as the principal private sector service center for Atlantic Canada and the center for regional public administration and defense.

The following table shows the relative contribution of each sector to GDP in basic prices (chained 2007 dollars) for Nova Scotia and Canada for the calendar years indicated.

NOVA SCOTIA GROSS DOMESTIC PRODUCT BY INDUSTRY IN BASIC PRICES

(CHAINED 2007 DOLLARS)

| | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | |

| | | 2012 | | | 2013 | | | 2014 | | | 2015 | | | 2016 | | | Compound

Annual

Rate

of Growth

2012-2016 | | | % of GDP

in Basic Prices,

2016 | |

| | | (In millions) | |

| | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | Nova

Scotia | | | Canada | |

Primary Sector: | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | |

Agriculture, Forestry, Fishing, and Hunting | | $ | 806.9 | | | $ | 792.8 | | | $ | 822.4 | | | $ | 824.2 | | | $ | 769.9 | | | | -1.2 | % | | | 2.3 | % | | | 1.7 | % |

Mining and Oil, and Gas Extraction | | | 689.7 | | | | 586.4 | | | | 881.3 | | | | 711.5 | | | | 677.3 | | | | -0.5 | % | | | 2.1 | % | | | 7.9 | % |

Utilities | | | 560.1 | | | | 588.4 | | | | 589.5 | | | | 576.4 | | | | 566.9 | | | | 0.3 | % | | | 1.7 | % | | | 2.2 | % |

| | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | |

| | | 2,056.7 | | | | 1,967.6 | | | | 2,293.2 | | | | 2,112.1 | | | | 2,014.1 | | | | -0.5 | % | | | 6.1 | % | | | 11.8 | % |

| | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | |

Secondary Sector: | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | |

Construction | | | 1,730.3 | | | | 1,697.9 | | | | 1,608.5 | | | | 1,711.0 | | | | 1,861.5 | | | | 1.8 | % | | | 5.6 | % | | | 7.0 | % |

Manufacturing | | | 2,651.0 | | | | 2,564.4 | | | | 2,455.2 | | | | 2,499.1 | | | | 2,570.1 | | | | -0.8 | % | | | 7.8 | % | | | 10.4 | % |

| | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | |

| | | 4,381.3 | | | | 4,262.3 | | | | 4,063.7 | | | | 4,210.1 | | | | 4,431.6 | | | | 0.3 | % | | | 13.4 | % | | | 17.4 | % |

| | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | |

Service Sector: | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | |

Transportation and Warehousing | | | 1,080.6 | | | | 1,081.4 | | | | 1,125.7 | | | | 1,154.7 | | | | 1,171.4 | | | | 2.0 | % | | | 3.5 | % | | | 4.5 | % |

Wholesale Trade | | | 1,341.6 | | | | 1,377.5 | | | | 1,434.9 | | | | 1,459.6 | | | | 1,421.0 | | | | 1.4 | % | | | 4.3 | % | | | 5.8 | % |

Retail Trade | | | 2,181.3 | | | | 2,234.2 | | | | 2,232.5 | | | | 2,241.7 | | | | 2,307.2 | | | | 1.4 | % | | | 7.0 | % | | | 5.5 | % |

Finance and Insurance | | | 1,811.3 | | | | 1,788.0 | | | | 1,771.0 | | | | 1,805.6 | | | | 1,830.9 | | | | 0.3 | % | | | 5.5 | % | | | 7.1 | % |

Real Estate, rental and leasing(1) | | | 5,056.1 | | | | 5,166.8 | | | | 5,239.0 | | | | 5,341.2 | | | | 5,437.9 | | | | 1.8 | % | | | 16.5 | % | | | 13.1 | % |

Management of Companies | | | 142.1 | | | | 141.8 | | | | 130.8 | | | | 124.9 | | | | 117.4 | | | | -4.7 | % | | | 0.4 | % | | | 0.7 | % |

Professional, scientific and technical services | | | 1,314.3 | | | | 1,359.3 | | | | 1,398.2 | | | | 1,483.1 | | | | 1,516.5 | | | | 3.6 | % | | | 4.6 | % | | | 5.4 | % |

Administrative and support, waste management and remediation services | | | 695.3 | | | | 658.4 | | | | 675.0 | | | | 659.4 | | | | 642.6 | | | | -2.0 | % | | | 1.9 | % | | | 2.5 | % |

Information and Cultural Industries | | | 1,084.5 | | | | 1,080.2 | | | | 1,083.8 | | | | 1,071.1 | | | | 1,050.3 | | | | -0.8 | % | | | 3.2 | % | | | 3.0 | % |

Education Services | | | 2,221.1 | | | | 2,215.1 | | | | 2,234.1 | | | | 2,264.0 | | | | 2,252.4 | | | | 0.4 | % | | | 6.8 | % | | | 5.2 | % |

Health Care and Social Assistance | | | 3,101.5 | | | | 3,124.1 | | | | 3,206.8 | | | | 3,230.4 | | | | 3,270.2 | | | | 1.3 | % | | | 9.9 | % | | | 6.7 | % |

Accommodation and Food Services | | | 777.4 | | | | 759.5 | | | | 780.1 | | | | 788.5 | | | | 802.7 | | | | 0.8 | % | | | 2.4 | % | | | 2.1 | % |

Arts, entertainment, and recreation | | | 173.6 | | | | 168.3 | | | | 176.6 | | | | 189.4 | | | | 198.9 | | | | 3.5 | % | | | 0.6 | % | | | 0.7 | % |

Other Services (except Public Administration) | | | 645.0 | | | | 653.1 | | | | 660.1 | | | | 651.7 | | | | 649.4 | | | | 0.2 | % | | | 2.0 | % | | | 1.9 | % |

Public Administration | | | 3,978.0 | | | | 3,886.2 | | | | 3,860.3 | | | | 3,884.9 | | | | 3,887.2 | | | | -0.6 | % | | | 11.8 | % | | | 6.4 | % |

| | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | |

| | | 25,603.7 | | | | 25,693.9 | | | | 26,008.9 | | | | 26,350.2 | | | | 26,556.0 | | | | 0.9 | % | | | 80.5 | % | | | 70.8 | % |

| | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | |

Gross Domestic Product at Basic Prices | | | 32,116.1 | | | | 32,019.5 | | | | 32,346.7 | | | | 32,722.8 | | | | 33,066.2 | | | | 0.7 | % | | | 100.0 | % | | | 100.0 | % |

| | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | |

Source: Statistics Canada, CANSIM Table 379-0030, 379-0031 (Canada GDP by industry).

| (1) | Includes imputed values of output from owner-occupied housing. |

11

Population and Labor Force

According to estimates by Statistics Canada, at July 1, 2016, the population of Nova Scotia was 948.6 thousand or 2.6% of Canada’s population of 36.3 million. Over the period July 2012 to July 2016, the population of Nova Scotia grew by 0.4%, as compared to growth of 4.4% for Canada. Nova Scotia’s labor force decreased at a compounded annual rate of 0.8% compared to an increase of 0.8% for Canada for the 2012 to 2016 calendar year period.

According to Statistics Canada data for 2016, the Province’s labor force averaged 486,600 persons, representing 61.7% of the population 15 years of age and over. This level is a decrease of 0.7 percentage points in the participation rate compared to 2015. The figures for the calendar year 2016 show a decline in the unemployment rate to 8.3% from a rate of 8.6% in 2015. The labor force and the number of unemployed persons in 2016 showed declines from the levels observed in 2015, while the labor force employed decreased marginally from 2015 levels.

As the baby boom cohort of Nova Scotia’s population ages, an increasing share of the population is found among age cohorts that have lower participation rates. Between 2012 and 2016, the share of the working age population as measured by the Labor Force Survey aged 55 and older grew from 37.0% to 40.0% while the share aged between 25 and 54 declined from 47.9% to 45.5%. In 2016, the labor force participation rate of those aged 55 and up (the cohort with rising share of the population) was 34.7% while the labor force participation rate of those aged 25-54 (the cohort with declining share of the population) was 85.4%.

Nova Scotia’s unemployment rate was 8.7% in October 2017, on a seasonally adjusted basis, which was the same as the October 2016 level. The unemployment rate over the same period for Canada decreased to 6.2% from 6.9% a year earlier. The unemployment rate for Nova Scotia in October 2017 reflects an increase of 1.6% in the labor force from a year earlier, a 14.8% increase in the number of individuals unemployed and a 0.5% increase in the number of individuals employed, compared to the same month in 2016.

The following table sets forth Nova Scotia’s population and labor force for the 2012 to 2016 calendar years.

POPULATION AND LABOR FORCE

| | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | |

| | | 2012 | | | 2013 | | | 2014 | | | 2015 | | | 2016 | | | Compound

Annual

Rate of

Growth | |

| | | (In thousands unless otherwise indicated) | | | | |

Total Population (July 1) | | | 944.9 | | | | 943.0 | | | | 942.2 | | | | 941.5 | | | | 948.6 | | | | 0.1 | % |

Population 15 Years of Age and Over | | | 781.6 | | | | 781.9 | | | | 783.0 | | | | 785.5 | | | | 788.7 | | | | 0.2 | % |

Labor Force | | | 503.5 | | | | 497.7 | | | | 491.6 | | | | 490.2 | | | | 486.6 | | | | -0.8 | % |

Labor Force Employed | | | 457.6 | | | | 452.6 | | | | 447.6 | | | | 448.1 | | | | 446.2 | | | | -0.6 | % |

Labor Force Unemployed | | | 46.0 | | | | 45.1 | | | | 44.0 | | | | 42.0 | | | | 40.4 | | | | -3.2 | % |

Participation Rate (%): | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | |

Nova Scotia | | | 64.4 | % | | | 63.7 | % | | | 62.8 | % | | | 62.4 | % | | | 61.7 | % | | | | |

Canada | | | 66.5 | % | | | 66.5 | % | | | 66.0 | % | | | 65.8 | % | | | 65.7 | % | | | | |

Unemployment Rate (%): | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | |

Nova Scotia | | | 9.1 | % | | | 9.1 | % | | | 9.0 | % | | | 8.6 | % | | | 8.3 | % | | | | |

Canada | | | 7.3 | % | | | 7.1 | % | | | 6.9 | % | | | 6.9 | % | | | 7.0 | % | | | | |

Sources: Statistics Canada, CANSIM Tables 051-0001, 282-0002.

12

The following table illustrates the distribution of employment in Nova Scotia by industry for the calendar years 2012 through 2016, and the compound annual rate of growth over the period 2012 to 2016.

EMPLOYMENT BY INDUSTRY

| | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | |

| | | 2012 | | | 2013 | | | 2014 | | | 2015 | | | 2016 | | | Compound

Annual

Rate of

Growth | |

| | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | |

| | | (In thousands) | |

Agriculture | | | 6.1 | | | | 5.7 | | | | 5.2 | | | | 5.4 | | | | 4.5 | | | | -7.3 | % |

Forestry, Fishing, Mining, Oil, and Gas | | | 11.5 | | | | 11.5 | | | | 11.2 | | | | 11.8 | | | | 11.3 | | | | -0.4 | % |

Utilities | | | 3.8 | | | | 4.2 | | | | 3.8 | | | | 3.7 | | | | 3.3 | | | | -3.5 | % |

Construction | | | 32.3 | | | | 34.7 | | | | 34.0 | | | | 33.6 | | | | 32.9 | | | | 0.5 | % |

Manufacturing | | | 32.8 | | | | 30.6 | | | | 29.9 | | | | 28.7 | | | | 29.1 | | | | -2.9 | % |

Wholesale and Retail Trade | | | 74.8 | | | | 75.2 | | | | 73.9 | | | | 71.8 | | | | 71.9 | | | | -1.0 | % |

Wholesale Trade | | | 12.9 | | | | 12.1 | | | | 13.2 | | | | 11.9 | | | | 13.2 | | | | 0.6 | % |

Retail Trade | | | 61.9 | | | | 63.0 | | | | 60.7 | | | | 59.9 | | | | 58.7 | | | | -1.3 | % |

Transportation and Warehousing | | | 20.9 | | | | 19.6 | | | | 20.9 | | | | 20.5 | | | | 20.3 | | | | -0.7 | % |

Finance, Insurance, Real Estate, and Leasing | | | 21.8 | | | | 20.9 | | | | 22.2 | | | | 23.4 | | | | 23.6 | | | | 2.0 | % |

Professional, Scientific, and Technical Services | | | 23.9 | | | | 26.5 | | | | 26.1 | | | | 27.8 | | | | 27.5 | | | | 3.6 | % |

Business, Building and Other Support Services | | | 21.2 | | | | 22.8 | | | | 19.7 | | | | 20.3 | | | | 17.5 | | | | -4.7 | % |

Educational Services | | | 35.6 | | | | 34.6 | | | | 35.4 | | | | 36.4 | | | | 36.7 | | | | 0.8 | % |

Health Care and Social Assistance | | | 70.6 | | | | 69.8 | | | | 69.2 | | | | 72.4 | | | | 74.9 | | | | 1.5 | % |

Information, Culture, and Recreation | | | 19.7 | | | | 18.4 | | | | 19.2 | | | | 17.5 | | | | 16.2 | | | | -4.8 | % |

Accommodation and Food Services | | | 32.6 | | | | 31.4 | | | | 32.1 | | | | 30.9 | | | | 29.5 | | | | -2.5 | % |

Other Services | | | 20.6 | | | | 19.4 | | | | 18.3 | | | | 17.1 | | | | 19.4 | | | | -1.5 | % |

Public Administration | | | 29.2 | | | | 27.5 | | | | 26.7 | | | | 27.0 | | | | 27.6 | | | | -1.4 | % |

| | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | |

Total - All Industries | | | 457.6 | | | | 452.6 | | | | 447.6 | | | | 448.1 | | | | 446.2 | | | | -0.6 | % |

| | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | |

Source: Statistics Canada, Table 282-0008.

13

Income and Prices

Household income in Nova Scotia increased 2.6% to $40.8 billion in 2016 from 2015, and average weekly wages in 2016 were $847.26, up 1.5% from the level in 2015.

The following table reflects the percentage increases in average weekly wages and salaries for calendar years 2012 through 2016 as well as the Consumer Price Index (“CPI”) for Nova Scotia and Canada to 2016. On an annual basis in 2016, Nova Scotia’s CPI increased by 1.2% from 2015, while Canada’s CPI increased by 1.4% from 2015.

CPI AND AVERAGE WEEKLY WAGES AND SALARIES, INDUSTRIAL

AGGREGATE (PERCENT INCREASE OVER PREVIOUS YEAR)

| | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | |

| | | Nova Scotia | | | Canada | |

| | Average Weekly

Wages and Salaries | | | CPI | | | Average Weekly

Wages and Salaries | | | CPI | |

2012 | | | 3.0 | % | | | 2.0 | % | | | 2.5 | % | | | 1.5 | % |

2013 | | | 1.2 | % | | | 1.2 | % | | | 1.8 | % | | | 0.9 | % |

2014 | | | 2.8 | % | | | 1.7 | % | | | 2.7 | % | | | 2.0 | % |

2015 | | | 1.8 | % | | | 0.4 | % | | | 1.8 | % | | | 1.1 | % |

2016 | | | 1.5 | % | | | 1.2 | % | | | 0.5 | % | | | 1.4 | % |

Sources: Statistics Canada, CANSIM Tables 281-0027 and 326-0021.

14

Capital Expenditures

Capital expenditures consist of investment in new construction, and purchases of machinery and equipment in Nova Scotia by the private sector and all levels of government.

The following table sets forth capital expenditures for the 2013 to 2016 calendar years and investment spending intentions for 2017.

CAPITAL EXPENDITURES(1)

| | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | |

| | | 2013 | | | 2014 | | | 2015 | | | 2016(2) | | | 2017(3) | |

| | | (in millions) | |

Agriculture, forestry, and fishing | | $ | 106.9 | | | $ | 100.6 | | | $ | 89.5 | | | $ | 87.6 | | | $ | 78.0 | |

Mining & oil and gas extraction | | | 92.5 | | | | 59.5 | | | | x | | | | 155.5 | | | | 109.0 | |

Utilities | | | 290.5 | | | | 348.6 | | | | 391.0 | | | | 537.0 | | | | 591.5 | |

Construction | | | 132.6 | | | | 130.6 | | | | 103.7 | | | | 94.5 | | | | 95.9 | |

Manufacturing | | | 335.0 | | | | 441.4 | | | | 352.6 | | | | 218.3 | | | | 206.1 | |

Wholesale trade | | | 111.8 | | | | 104.4 | | | | 84.4 | | | | 112.7 | | | | 120.4 | |

Retail trade | | | 233.7 | | | | 178.8 | | | | F | | | | 172.3 | | | | 162.4 | |

Transportation & warehousing | | | 326.2 | | | | 300.3 | | | | 392.3 | | | | 522.9 | | | | 357.3 | |

Information & cultural industries | | | 276.1 | | | | 189.8 | | | | 234.4 | | | | 245.8 | | | | 234.9 | |

Finance & insurance | | | x | | | | 37.5 | | | | 53.1 | | | | 59.6 | | | | 51.1 | |

Real estate and rental and lending | | | 235.8 | | | | 305.1 | | | | x | | | | 303.4 | | | | 332.5 | |

Professional, scientific & technical services | | | x | | | | 46.7 | | | | 48.3 | | | | F | | | | 58.0 | |

Management of companies and enterprises | | | x | | | | 2.7 | | | | x | | | | 6.3 | | | | F | |

Administrative support, waste management and remediation services | | | x | | | | x | | | | 36.9 | | | | 26.3 | | | | 35.0 | |

Educational services | | | 283.5 | | | | 187.6 | | | | 133.4 | | | | 237.9 | | | | 358.3 | |

Health care and social assistance | | | 157.9 | | | | 115.6 | | | | 83.7 | | | | 115.5 | | | | 106.8 | |

Arts, entertainment and recreation | | | x | | | | 44.4 | | | | 71.5 | | | | 109.9 | | | | 82.8 | |

Accommodation and food services | | | 86.7 | | | | 86.5 | | | | x | | | | 54.0 | | | | 58.8 | |

Other services (except public administration) | | | x | | | | x | | | | x | | | | 29.6 | | | | 20.9 | |

Public administration | | | 754.4 | | | | 681.7 | | | | 657.2 | | | | 724.5 | | | | 772.2 | |

| | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | |

Total | | $ | 3,575.4 | | | $ | 3,423.4 | | | $ | 3,467.2 | | | $ | 3,862.0 | | | $ | 3,836.9 | |

| | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | |

Private Sector | | | 2,280.6 | | | | 2,302.6 | | | | 2,336.8 | | | | 2,772.9 | | | | 2,636.9 | |

Public Sector | | | 1,294.8 | | | | 1,120.8 | | | | 1,130.4 | | | | 1,089.2 | | | | 1,200.0 | |

| | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | |

Total | | $ | 3,575.4 | | | $ | 3,423.4 | | | $ | 3,467.2 | | | $ | 3,862.0 | | | $ | 3,836.9 | |

| | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | |

Construction | | | 1,948.1 | | | | 1,786.3 | | | | 1,952.7 | | | | 2,229.4 | | | | 2,297.2 | |

Machinery and Equipment | | | 1,627.3 | | | | 1,637.1 | | | | 1,514.5 | | | | 1,632.7 | | | | 1,539.7 | |

| | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | |

Total | | $ | 3,575.4 | | | $ | 3,423.4 | | | $ | 3,467.2 | | | $ | 3,862.0 | | | $ | 3,836.9 | |

| | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | |

| (1) | Capital Expenditures are classified under the North American Industrial Classification System (“NAICS”), x—suppressed by Statistics Canada to meet the confidentiality requirements of the Statistics Act, F—too unreliable to be published by Statistics Canada |

| (3) | Investment Intentions. |

Source: Statistics Canada, CANSIM Tables 029-0045 and 029-0048.

15

According to the “Annual Capital and Repair Expenditures Survey,” capital expenditure intentions showed a 0.6% decrease for Nova Scotia in 2017 from 2016, reflecting expectations of decreased capital spending in mining and gas extraction, and transportation and warehousing. The decrease was partly offset by increases in utilities, educational services and public administration. Capital expenditures as used in this survey, released in February 2017, is defined as the collection of data on intentions for capital investment and expenditures and does not include housing.

According to the “Annual Capital and Repair Expenditures Survey,” capital expenditures showed a 11.4% increase for Nova Scotia in 2016 over 2015, reflecting expectations of increased capital spending in utilities, transportation and warehousing, and educational services. The increase was partly offset by decreases in manufacturing.

Capital expenditures for 2015 showed a 1.3% increase over 2014. The change reflected an increase in utilities, transportation and warehousing, and information and cultural industries. Partially offsetting the above increases were decreases in manufacturing and educational services.

Capital expenditures for 2014 showed a 4.3% decrease compared to 2013. The change reflected a decrease in capital spending in educational services, information and cultural industries, and public administration. The decrease was partially offset by increases in real estate and rental and leasing, manufacturing, and utilities.

Goods Producing Industries

Manufacturing. The manufacturing industry is the largest contributor to the goods producing portion of Nova Scotia’s economy and accounted for 7.8% of real GDP (basic prices in chained 2007 dollars) in 2016. The gross selling value of manufacturing sales for Nova Scotia in the years 2012, 2013, 2014, 2015 and 2016 were as follows: $10,460 million, $9,450 million, $7,347 million, $7,729 and $8,053 million, a compounded annual rate of decrease of 6.3% over the period. This compares with an increase of 1.1% for Canada over the same period. In 2016, over 60% of manufacturing sales were from the food, plastics and rubber products and paper and wood products subsectors.

The employment level in the manufacturing sector in 2016 was 29,100, an increase of 400 persons compared to 2015. The manufacturing sector employed 6.5% of all workers in Nova Scotia in 2016, compared to 9.4% in Canada. Most of the employment in the manufacturing sector occurs outside of the province’s largest urban center (Halifax Regional Municipality) making the sector directly and indirectly a key employer in many of the more rural areas of the Province.

The United States is the primary market for Nova Scotia’s international total exports. In 2016, $3.7 billion or 68.4% of the value of Nova Scotia’s international total exports went to the United States.

Construction. The construction industry is the second largest goods-producing industry in Nova Scotia. Its contribution to real GDP (basic prices in chained 2007 dollars) was $1.9 billion in 2016 and accounted for 5.6% of total real GDP. Construction activity accounted for 57.7% of total capital expenditures in 2016. Compounded annually capital expenditures on construction in Nova Scotia increased 1.3% for the 2012 to 2016 period, as compared to a 1.5% decrease for Canada.

Canada Mortgage and Housing Corporation reported that housing starts in all areas of Nova Scotia decreased by 1.5% in 2016 from 2015, compared to an increase of 1.2% at the national level over the same period.

The Federal government’s new mortgage policies will expand the use and stringency of stress tests in mortgage insurance and elevate insurance criteria for low-ratio mortgages/mortgage loans that constitute greater than 80% of the value of a home. These Federal regulatory changes were directed at housing markets in Toronto and Vancouver. It is not clear that the Federal changes will have an impact on Nova Scotia homebuyers, especially those who would consider purchasing newly-built dwellings. Although Federal government policy can have an impact on housing markets through restrictions in mortgage financing, the recent performance of the Province’s housing sector is more likely attributable to longer-term demographic trends and a shift of the market away from single-detached dwellings to multi-unit apartments.

16

Housing price growth in Halifax has been variable from year to year but generally flat since 2012. The Royal Bank of Canada’s measure of housing affordability shows Halifax to be one of the most affordable of the major cities in Canada suggesting that new mortgage rules may not impair housing affordability in the Halifax market.

Overall residential activity in Nova Scotia has slowed over the past decade. Nova Scotia’s aging demographics has driven a shift in demand away from single-detached housing toward multiple-unit construction intended for the rental market. Housing starts outpaced the relatively slow population growth and household formation rates in the Province over the past five years. Most of the construction has been in Halifax where population growth rates have been higher.

HOUSING STARTS, ALL AREAS, NOVA SCOTIA

| | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | |

| | | 2012 | | | 2013 | | | 2014 | | | 2015 | | | 2016 | |

Single-detached | | | 2,258 | | | | 1,639 | | | | 1,355 | | | | 1,350 | | | | 1,656 | |

Multiples | | | 2,264 | | | | 2,280 | | | | 1,701 | | | | 2,475 | | | | 2,111 | |

Semi-detached | | | 420 | | | | 332 | | | | 220 | | | | 259 | | | | 318 | |

Row | | | 218 | | | | 259 | | | | 179 | | | | 129 | | | | 144 | |

Apartment and other unit type | | | 1,626 | | | | 1,689 | | | | 1,302 | | | | 2,087 | | | | 1,649 | |

| | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | |

Total units | | | 4,522 | | | | 3,919 | | | | 3,056 | | | | 3,825 | | | | 3,767 | |

| | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | |

Source: Statistics Canada, CANSIM Tables 027-0008.

Employment in the construction sector during 2016 was 32,900, a decrease of 700 persons from levels in 2015.

Fisheries. A large and diverse commercial fish and processing industry exists in Nova Scotia. Nova Scotia harvests over 50 different species of seafood, and exports these products to all major seafood markets. The Federal Government, through detailed stock assessment plans and quotas, manages fisheries resources. The primary fishing sector contributed $417.3 million (in chained 2007 dollars) to the provinces’ GDP in 2016, a decrease of 9.0% from 2015 levels.

Nova Scotia’s fish landings had a value of $1,211.5 million in 2015, and total volume of commercial fish landings increased by 2.5% in 2015 compared to the level in 2014. The value of Nova Scotia’s fish landings for 2016 have not been released by the Federal Department of Fisheries and Oceans. The impact of fishing on the province’s GDP is also seen in the manufacturing segment, which includes fish processing. Lobster is the predominant species and represented 57.4% of the total landed value in 2015. Scallop, Shrimp, and Queen Crab were the next predominant species in 2015 at 13.8%, 7.7%, and 6.0% respectively.

Nova Scotia was the largest exporter of fresh and processed seafood in 2016 among all provinces, at $1,666.7 million. The United States is Nova Scotia’s top destination, representing 53.1% of fresh and processed seafood exports in 2016. Nova Scotia exports to over 70 countries including China, Japan, South Korea, United Kingdom, Denmark, Hong Kong and France. The export value of seafood in 2016 increased by 5.0% compared to the total value in 2015.

The harvesting sector employed 4,900 persons throughout all of Nova Scotia in 2016, a decrease of approximately 600 persons from 2015.

The following table sets forth information with respect to the value of fish landings in Nova Scotia for the calendar years 2011 through 2015, and the value of exports of fresh and processed fish, including the value of exports of major species.

17

FISHING AND FISH PROCESSING INDUSTRY

| | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | |

| | | 2011 | | | 2012 | | | 2013 | | | 2014 | | | 2015 | |

| | | (in Millions) | |

Value of Fish Landings | | $ | 732.0 | | | $ | 768.5 | | | $ | 844.7 | | | $ | 1,046.7 | | | $ | 1.211.5 | |

| | | | | |

| | | 2012 | | | 2013 | | | 2014 | | | 2015 | | | 2016 | |

| | | (in Millions) | |

Value of Exports of fresh and processed fish | | $ | 872.7 | | | $ | 1,001.7 | | | $ | 1,197.7 | | | $ | 1,588.0 | | | $ | 1,666.7 | |

Lobster, fresh or frozen | | | 362.9 | | | | 422.9 | | | | 549.2 | | | | 893.0 | | | | 952.9 | |

Scallops, fresh or frozen | | | 98.1 | | | | 130.5 | | | | 163.0 | | | | 168.7 | | | | 139.0 | |

Crab, frozen | | | 132.0 | | | | 139.0 | | | | 167.2 | | | | 179.1 | | | | 222.6 | |

Shrimp, frozen | | | 75.8 | | | | 102.7 | | | | 109.5 | | | | 128.1 | | | | 107.1 | |

Sources: Department of Fisheries and Oceans, Industry Canada.

Mining and Mineral Exploration The value of mineral production (excluding oil and gas) in Nova Scotia was $230.1 million in 2016, unchanged from 2015 levels. The major minerals reported being produced in Nova Scotia in 2016 were crushed stone, sand and gravel. Nova Scotia’s gypsum and anhydrite deposits have been reported to be among the largest workable deposits in Canada. Gypsum outcrops occur throughout the whole of the northern half of the province’s mainland and Cape Breton Island. Gypsum data has been suppressed by Natural Resources Canada for confidentiality reasons. However, according to 2012 statistics, Nova Scotia produced about 65% of gypsum for all of Canada.

Real GDP in the sector, including the oil and gas sector, decreased by 4.8% in 2016 from 2015. The industry, including the oil and gas sector, employed 4,000 persons in 2016.

There are currently two surface coal mines operating in Nova Scotia, at Stellarton and Point Aconi, operated by Pioneer Coal. In March 2017, an underground coal mine in Cape Breton started initial production at Donkin from a single continuous miner. Production information on the sector is currently unavailable due to confidentiality requirements of Statistics Canada.

Agriculture Real GDP in 2016 in the crop and animal production sector decreased by 1.7% compared to 2015. Total farm cash receipts in 2016 decreased by 0.7%, comprised of a decline in crop receipts of 1.7%, a decrease in the receipts for livestock production of 7.9%, offset by an increase of 305.5% in total receipts from direct payments (these are primarily government support payments and crop insurance). The number of people employed in the agricultural sector stood at 4,500 persons in 2016, a decrease of about 900 from 2015. The major components of agricultural production in Nova Scotia include dairy products, fruit, livestock, field vegetables, eggs and furs.

Forestry In 2016, the value of manufacturing shipments for wood products was $465.2 million, an increase of 15.3% from 2015. The forestry logging and logging support sector employed 2,400 workers in 2016, unchanged from 2015. In 2016, the total provincial harvest of solid wood was 3,736,468 cubic meters, an increase of 2.6% over 2015. Of this amount, 320,596 cubic meters or 8.6% was exported.

Lumber shipments in 2016 were 1.13 million cubic meters, up 21.5% from 2014 (data for 2015 were suppressed by Statistics Canada due to confidentially reasons). Export sales of lumber and wood products decreased 11.2% in 2016 from 2015. The largest export destination for forestry products is the United States (50.4% in 2016), and exports to the US decreased by 17.3% in 2016 compared to 2015. In 2016, export sales for pulp and paper products were down 16.6% over 2015.

Exports

The total value of exports of goods and services from Nova Scotia in 2016, under Statistics Canada’s Provincial Economic Accounts data system, stood at $15,410 million, giving an annual compound growth rate of 0.5% over the 2012 to 2016 period. The value of exports of goods and services represented 36.9% of the total value of GDP in 2015.

18

Of the $15,410 million in exports of goods and services, 45.8%, or $7,058 million, was shipped to other countries, leaving 54.2% or $8,352 million as exports to other provinces within Canada. Exports of goods accounted for 60.7% of the total exports while exports of services accounted for 39.3%. Most of the goods are exported to other countries (57.9%), while services are mostly exported to other provinces (72.8%).

Over the 2012 to 2016 period, the total value of exports of goods had an annual compound rate of decline of 1.1% compared to a growth rate of 3.2% for the total value of export of services.

Statistics Canada reports in their Provincial Economic Accounts that the total value of international exports of goods in 2016 was $5,413 million, experiencing an annual compound rate of decline of 1.4% since 2012. The Provincial Economic Accounts figure can be contrasted with Nova Scotia’s international merchandise domestic exports of goods based on customs clearing data that amounted to $5,230 million in 2016. The Provincial Economic Accounts adjusts the customs data for other costs such as transportation margins and duties. Additionally, “domestic” international exports do not include exports from the Province that originated outside the Province. During the years 2012, 2013, 2014, 2015 and 2016 the average Canadian dollar/US dollar noon exchange rate, according to the Bank of Canada, was $0.9996, $1.0299, $1.1045, $1.2787 and $1.3248 Canadian dollars per one U.S. dollar respectively.

The following table sets forth categories of Selected Trade indicators for the calendar years 2012 through 2016.

SELECTED TRADE INDICATORS

| | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | |

| | | 2012 | | | 2013 | | | 2014 | | | 2015 | | | 2016 | |

| | | (In millions $) | |

Exports of goods to other countries | | $ | 5,726 | | | $ | 5,251 | | | $ | 5,023 | | | $ | 5,315 | | | $ | 5,413 | |

Export of services to other countries | | | 1,427 | | | | 1,468 | | | | 1,519 | | | | 1,592 | | | | 1,645 | |

| | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | |

Exports to other countries | | | 7,153 | | | | 6,719 | | | | 6,542 | | | | 6,907 | | | | 7,058 | |

| | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | |

Exports of goods to other provinces | | | 4,036 | | | | 4,262 | | | | 3,589 | | | | 3,710 | | | | 3,941 | |

Export of services to other provinces | | | 3,909 | | | | 3,950 | | | | 4,196 | | | | 4,330 | | | | 4,411 | |

| | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | |

Exports to other provinces | | | 7,945 | | | | 8,212 | | | | 7,785 | | | | 8,040 | | | | 8,352 | |

| | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | |

Total Exports of goods and services: | | | 15,098 | | | | 14,931 | | | | 14,327 | | | | 14,947 | | | | 15,410 | |

| | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | |

Imports of goods from other countries | | | 11,051 | | | | 11,163 | | | | 10,488 | | | | 11,264 | | | | 11,481 | |

Import of services from other countries | | | 1,444 | | | | 1,532 | | | | 1,602 | | | | 1,707 | | | | 1,845 | |

| | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | |

Imports from other countries | | | 12,495 | | | | 12,695 | | | | 12,090 | | | | 12,971 | | | | 13,326 | |

| | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | |

Imports of goods from other provinces | | | 5,859 | | | | 5,963 | | | | 5,348 | | | | 5,089 | | | | 5,245 | |

Imports of services from other provinces | | | 7,164 | | | | 7,490 | | | | 7,769 | | | | 8,032 | | | | 8,389 | |

| | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | |

Imports from other provinces | | | 13,023 | | | | 13,453 | | | | 13,117 | | | | 13,121 | | | | 13,634 | |

| | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | |

Total Imports of goods and services: | | | 25,518 | | | | 26,148 | | | | 25,207 | | | | 26,092 | | | | 26,960 | |

| | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | |

Trade Balance | | | (10,420 | ) | | | (11,217 | ) | | | (10,880 | ) | | | (11,145 | ) | | | (11,550 | ) |

| | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | |

Source: Statistics Canada, CANSIM Tables 384-0038. | |

19

The following two tables sets forth Nova Scotia’s top international merchandise exports by industry and the top imports by product for the calendar years 2012 through 2016, and the compound annual growth rate over the 2012 to 2016 period.

INTERNATIONAL MERCHANDISE EXPORTS BY INDUSTRY

| | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | |

| | | 2012 | | | 2013 | | | 2014 | | | 2015 | | | 2016 | | | Compound

Annual Rate

of Growth | |

| | | | | | (in millions) | | | | | | | | | | |

Tire Manufacturing | | $ | 1,028.1 | | | $ | 1,002.7 | | | | 1,087.8 | | | $ | 1,182.2 | | | $ | 1,195.3 | | | | 3.8 | % |

Seafood Product Preparation and Packaging | | | 489.2 | | | | 545.2 | | | | 625.2 | | | | 800.1 | | | | 917.9 | | | | 17.0 | % |

Fishing | | | 432.9 | | | | 507.0 | | | | 640.3 | | | | 885.1 | | | | 878.0 | | | | 19.3 | % |

Pulp Mills | | | 164.9 | | | | 201.1 | | | | 221.1 | | | | 241.5 | | | | 224.4 | | | | 8.0 | % |

Paper Mills | | | 111.7 | | | | 294.7 | | | | 229.7 | | | | 243.3 | | | | 174.8 | | | | 11.8 | % |

Sawmills and Wood Preservation | | | 80.9 | | | | 99.5 | | | | 118.6 | | | | 107.0 | | | | 118.1 | | | | 9.9 | % |

Frozen Food Manufacturing | | | 120.7 | | | | 114.9 | | | | 122.9 | | | | 129.6 | | | | 108.3 | | | | -2.7 | % |

Navigational, Measuring Medical, and control instruments | | | 88.3 | | | | 94.8 | | | | 107.1 | | | | 108.3 | | | | 85.3 | | | | -0.9 | % |

Unsupported Plastic Film, Sheet, and Bag Manufacturing | | | 64.1 | | | | 54.5 | | | | 61.8 | | | | 85.8 | | | | 85.1 | | | | 7.3 | % |

Recyclable Metal Wholesaler-Distributors | | | 76.0 | | | | 72.2 | | | | 80.4 | | | | 58.9 | | | | 79.7 | | | | 1.2 | % |

| | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | |

Sub-total | | | 2,656.8 | | | | 2,986.7 | | | | 3,295.0 | | | | 3,841.8 | | | | 3,866.9 | | | | 9.8 | % |

| | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | |

Other | | | 1,177.7 | | | | 1,337.2 | | | | 1,954.9 | | | | 1,504.2 | | | | 1,363.3 | | | | 3.7 | % |

| | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | |

Grand total | | $ | 3,834.5 | | | $ | 4,323.9 | | | $ | 5,249.9 | | | $ | 5,346.0 | | | $ | 5,230.2 | | | | 8.1 | % |

| | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | |

Source: Industry Canada, 5 digit NAICS codes.

INTERNATIONAL MERCHANDISE IMPORTS BY PRODUCT

| | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | |

| | | 2012 | | | 2013 | | | 2014 | | | 2015 | | | 2016 | | | Compound

Annual Rate

of Growth | |

| | | | | | (in millions) | | | | | | | | | | |

Motor Vehicles for Passenger Transport | | $ | 2,555.1 | | | $ | 2,600.2 | | | $ | 2,965.5 | | | $ | 3,196.2 | | | $ | 3,672.5 | | | | 9.5 | % |

Preparations of non-crude petroleum oils | | | 116.6 | | | | 284.2 | | | | 1,402.2 | | | | 1,303.2 | | | | 1,033.4 | | | | 72.5 | % |

Trucks and Other Vehicles for Transport of Goods | | | 114.1 | | | | 111.4 | | | | 150.9 | | | | 188.8 | | | | 190.7 | | | | 13.7 | % |

Ferry boats, Cruise Ships and Excursion Boats | | | | | | | 66.7 | | | | | | | | | | | | 141.0 | | | | n/a | |

Coal and Solid Fuels Manufactured from Coal | | | 143.0 | | | | 193.2 | | | | 161.9 | | | | 171.3 | | | | 119.6 | | | | -4.4 | % |

Electrical Transformers, Static Converters | | | 9.6 | | | | 12.4 | | | | 27.0 | | | | 13.7 | | | | 107.8 | | | | 83.0 | % |

Fish Fillets and Other Fish Meat—Fresh, Chilled | | | 69.4 | | | | 71.1 | | | | 89.7 | | | | 88.2 | | | | 103.4 | | | | 10.5 | % |

Natural Rubber; Balata, Gutta-Percha, Guayule, Chicle and Similar Natural Gums | | | 217.5 | | | | 173.0 | | | | 139.5 | | | | 123.4 | | | | 100.7 | | | | -17.5 | % |

Helicopters, Airplanes and Spacecraft | | | 72.1 | | | | 2.4 | | | | 134.2 | | | | 317.1 | | | | 93.2 | | | | 6.6 | % |

Self-Propelled Bulldozers, Scapers, Graders | | | 92.5 | | | | 58.0 | | | | 75.8 | | | | 82.9 | | | | 71.4 | | | | -6.3 | % |

| | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | |

Sub-Total | | | 3,390.0 | | | | 3,572.6 | | | | 5,146.7 | | | | 5,484.7 | | | | 5,633.7 | | | | 13.5 | % |

| | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | |

Other | | | 3,240.6 | | | | 2,446.5 | | | | 2,661.0 | | | | 2,806.4 | | | | 2,526.6 | | | | -6.0 | % |

| | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | |

Grand Total | | $ | 6,630.6 | | | $ | 6,019.0 | | | $ | 7,807.7 | | | $ | 8,291.1 | | | $ | 8,160.3 | | | | 5.3 | % |

| | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | |

Source: Industry Canada, HS4 codes.

Merchandise imports by commodity are assessed based on their port of clearance, rather than their intended destination in Canada (or beyond). Of note in the table on imports into Nova Scotia by product grouping is the large amount of motor vehicle for passenger transport. Most of these vehicles arrive from Europe, and are then shipped across Canada.

20

The following tables show top export destinations and import sources. The ranking for the top countries is based on their value in 2016, but the same countries are shown for all five years.

INTERNATIONAL MERCHANDISE EXPORTS BY TOP 10 COUNTRIES

| | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | |

| | | 2012 | | | 2013 | | | 2014 | | | 2015 | | | 2016 | |

| | | | | (in millions) | | | | | | | |

United States | | $ | 2,780.0 | | | $ | 3,071.6 | | | $ | 3,885.1 | | | $ | 3,787.0 | | | $ | 3,606.3 | |

China | | | 149.6 | | | | 197.3 | | | | 275.6 | | | | 420.3 | | | | 491.1 | |

United Kingdom | | | 74.5 | | | | 72.5 | | | | 79.4 | | | | 78.1 | | | | 88.8 | |

France (incl. Monaco, French Antilles) | | | 80.9 | | | | 68.5 | | | | 75.9 | | | | 84.3 | | | | 85.5 | |

Japan | | | 41.6 | | | | 36.1 | | | | 45.6 | | | | 59.1 | | | | 85.0 | |

Hong Kong | | | 70.1 | | | | 68.9 | | | | 85.7 | | | | 102.9 | | | | 84.7 | |

Korea, South | | | 35.1 | | | | 37.6 | | | | 57.8 | | | | 65.3 | | | | 83.8 | |

Mexico | | | 31.3 | | | | 35.1 | | | | 47.0 | | | | 65.0 | | | | 79.8 | |

Vietnam | | | 8.7 | | | | 20.7 | | | | 29.4 | | | | 33.9 | | | | 53.6 | |

Germany | | | 46.4 | | | | 44.0 | | | | 44.4 | | | | 45.1 | | | | 44.3 | |

| | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | |

Sub-total | | | 3,318.3 | | | | 3,652.2 | | | | 4,626.0 | | | | 4,741.1 | | | | 4,703.0 | |

| | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | |

Other | | | 516.2 | | | | 671.6 | | | | 624.0 | | | | 604.9 | | | | 527.3 | |

| | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | |

Total All Countries(1) | | $ | 3,834.5 | | | $ | 4,323.9 | | | $ | 5,249.9 | | | $ | 5,346.0 | | | $ | 5,230.2 | |

| | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | |

Source: Industry Canada. | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | |

INTERNATIONAL MERCHANDISE IMPORTS BY TOP 10 COUNTRIES(1)

| | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | |

| | | 2012 | | | 2013 | | | 2014 | | | 2015 | | | 2016 | |

| | | | | (in millions) | | | | | | | |

Germany | | $ | 2,312.2 | | | $ | 2,388.6 | | | $ | 2,389.8 | | | $ | 2,697.9 | | | $ | 2,855.7 | |

United States | | | 461.4 | | | | 564.5 | | | | 1,849.2 | | | | 1,618.7 | | | | 1,039.4 | |

United Kingdom | | | 588.9 | | | | 587.1 | | | | 769.8 | | | | 847.9 | | | | 982.2 | |

Sweden | | | 198.2 | | | | 165.1 | | | | 198.4 | | | | 203.9 | | | | 376.1 | |

Cuba | | | 525.3 | | | | 470.1 | | | | 533.9 | | | | 492.6 | | | | 366.5 | |

China | | | 244.8 | | | | 262.6 | | | | 291.4 | | | | 318.2 | | | | 340.9 | |

France (incl. Monaco, French Antilles) | | | 161.9 | | | | 73.2 | | | | 107.5 | | | | 71.4 | | | | 157.1 | |

Romania | | | 3.0 | | | | 2.6 | | | | 3.3 | | | | 1.3 | | | | 142.1 | |

Lithuania | | | 0.1 | | | | 0.3 | | | | 0.1 | | | | 0.0 | | | | 114.0 | |

Estonia | | | 0.3 | | | | 0.8 | | | | 0.3 | | | | 56.6 | | | | 112.6 | |

| | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | |

Sub-total | | | 4,496.0 | | | | 4,514.9 | | | | 6,143.7 | | | | 6,308.6 | | | | 6,486.6 | |

| | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | |

Other | | | 2,134.6 | | | | 1,504.2 | | | | 1,664.0 | | | | 1,982.5 | | | | 1,673.6 | |

| | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | |

Total All Countries | | $ | 6,630.6 | | | $ | 6,019.0 | | | $ | 7,807.7 | | | $ | 8,291.1 | | | $ | 8,160.3 | |

| | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | |

Source: Industry Canada. | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | |

| (1) | Merchandise trade data on a customs basis reports imports based on their province of clearance. Much of the value of goods cleared at Nova Scotia ports is not in fact destined for Nova Scotia customers and as such does not reflect the nature of economic relationship between the Province and the countries listed as major import sources. For example, Halifax has a significant auto port at which a large number of high valued cars from Germany (and elsewhere in Europe) are cleared, loaded onto trains and shipped elsewhere in North America. |

The new U.S. Administration is currently renegotiating the North American Free Trade Agreement (“NAFTA”) with Canada and Mexico. The form and extent of the renegotiations of NAFTA are uncertain at this time. Consequently, it is unclear how this would impact Nova Scotia’s trade with the U.S.

21

The Comprehensive Economic and Trade Agreement with the European Union (CETA) became effective on September 21, 2017. The removal of most tariff lines from European Union imports from Canada is anticipated to make Canadian goods more competitively priced in European markets.

After the United States, the European Union is the second largest destination of Nova Scotia goods exports. The bulk of Nova Scotia exports to European Union destinations are fish and agricultural products as well as aerospace parts.

Service Sector

Overview. The Halifax metropolitan area is the largest financial and commercial service center in Atlantic Canada. The area is also one of Canada’s major medical and scientific communities, and the location of several federally sponsored scientific research institutions, including the Bedford Institute of Oceanography. The Halifax region is also home to several universities as it is a major education center for Atlantic Canada.

The Halifax region accounted for 50.7% of the total employment in Nova Scotia in 2016 producing an unemployment rate of 6.1% for 2016 compared to the 8.3% unemployment rate for the Province as a whole, and a 7.0% unemployment rate for Canada.

The following table sets forth the percentage contribution to the GDP for the service sector by component for the calendar years 2012 through 2016.

SERVICE INDUSTRIES AS A PERCENTAGE OF TOTAL SERVICE PRODUCING INDUSTRIES

| | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | |

| | | 2012 | | | 2013 | | | 2014 | | | 2015 | | | 2016 | |

Wholesale trade | | | 5.2 | % | | | 5.4 | % | | | 5.5 | % | | | 5.5 | % | | | 5.4 | % |

Retail trade | | | 8.5 | % | | | 8.7 | % | | | 8.6 | % | | | 8.5 | % | | | 8.7 | % |

Transportation and warehousing(1) | | | 4.2 | % | | | 4.2 | % | | | 4.3 | % | | | 4.4 | % | | | 4.4 | % |

Information and cultural industries | | | 4.2 | % | | | 4.2 | % | | | 4.2 | % | | | 4.1 | % | | | 4.0 | % |

Finance and insurance | | | 7.1 | % | | | 7.0 | % | | | 6.8 | % | | | 6.9 | % | | | 6.9 | % |

Real estate and rental and leasing | | | 19.7 | % | | | 20.1 | % | | | 20.2 | % | | | 20.3 | % | | | 20.5 | % |

Professional, scientific and technical services | | | 5.1 | % | | | 5.3 | % | | | 5.4 | % | | | 5.6 | % | | | 5.7 | % |

Management of companies and enterprises | | | 0.6 | % | | | 0.6 | % | | | 0.5 | % | | | 0.5 | % | | | 0.4 | % |

Administrative and support, waste management and remediation services | | | 2.7 | % | | | 2.6 | % | | | 2.6 | % | | | 2.5 | % | | | 2.4 | % |

Educational services | | | 8.7 | % | | | 8.6 | % | | | 8.6 | % | | | 8.6 | % | | | 8.5 | % |

Health care and social assistance | | | 12.1 | % | | | 12.2 | % | | | 12.3 | % | | | 12.3 | % | | | 12.3 | % |

Arts, entertainment and recreation | | | 0.7 | % | | | 0.7 | % | | | 0.7 | % | | | 0.7 | % | | | 0.7 | % |

Accommodation and food services | | | 3.0 | % | | | 3.0 | % | | | 3.0 | % | | | 3.0 | % | | | 3.0 | % |

Other services (except public administration) | | | 2.5 | % | | | 2.5 | % | | | 2.5 | % | | | 2.5 | % | | | 2.4 | % |

Public administration | | | 15.5 | % | | | 15.1 | % | | | 14.9 | % | | | 14.8 | % | | | 14.7 | % |

Total (2) | | | 100.0 | % | | | 100.0 | % | | | 100.0 | % | | | 100.0 | % | | | 100.0 | % |

| | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | |

| (1) | Includes Pipeline Transportation – See “Offshore Exploration and Development”. |

| (2) | Numbers may not add up due to rounding. |

Source: Statistics Canada, CANSIM Table 379-0030.

Trade. In 2016, wholesale merchants’ sales increased 0.5% and retail sales increased by 4.6% respectively in Nova Scotia compared to an increase of 2.7% and 5.1% respectively in Canada over 2015. The value of retail sales in 2016 in Nova Scotia was $14.7 billion. The compound annual rate of growth in retail sales was 2.7% in Nova Scotia and 4.1% in Canada during the 2012 to 2016 period. Employment in the wholesale sector and retail sector stood at 13,200 and 58,700 persons respectively in 2016. This represents an increase of approximately 1,300 persons in the wholesale sector and a decrease of 1,200 persons in the retail sector compared to 2015.

22

The value of wholesale merchants’ sales was $9.3 billion in 2016, an increase of 0.5% compared to 2015. In 2016, the wholesale sector had a real GDP negative rate of change of 2.6%. The combined wholesale and retail trade sector accounts for 11.3% of the total value of real GDP at basic prices for the Province.

Transportation and Warehousing. Transportation and warehousing have been important factors in the economy of Nova Scotia throughout its history. Halifax harbor and the Strait of Canso are deep-water, ice-free harbors. The Port of Halifax is capable of handling vessels up to 150,000 metric tonnes, and the Strait of Canso can accommodate the world’s largest super-tankers.

The sector’s real GDP (chained 2007 dollars) in 2016 increased by 1.4% from 2015. In 2016, the sector employed about 20,300 persons, a decrease of 200 from 2015.

Port facilities at Halifax include 35 deep-water berths that are complemented by rail, air, and motor freight services. With two container terminals, each capable of berthing two container ships simultaneously, Halifax is Canada’s fourth largest container port and is capable of handling fully laden Post-Panamax vessels. Halifax’s south end container terminal is undergoing a project to simultaneously berth and service two post-Panamax vessels. The total volume of cargo handled by the Port of Halifax in 2016 was 8.3 million metric tonnes. In 2016, containerized cargo tonnage amounted for 4.1 million metric tonnes. The Port of Halifax handled 480,722 TEU (twenty foot equivalent units) in 2016, up 14.9% from the number in 2015. Non-containerized cargo accounted for approximately 4.2 million metric tonnes. Non-containerized cargo consists of Bulk cargo (chiefly consisting of petroleum products and gypsum), Ro/Ro (roll-on/roll-off) and break-bulk. This port serves as a trans-shipment point for automobile distribution throughout Atlantic Canada via ship and rail. The Port of Halifax had visitation by 136 cruise vessels in 2016 with 238,217 passengers.

Tourism. Nova Scotia had approximately 2.237 million non-resident overnight tourists during 2016, an increase of 8.2% over 2015. Overall in 2016, the majority of visitors, 86.4%, came from other parts of Canada, while 9.9% from the United States, and 3.7% from overseas. About 68.7% of visitors to Nova Scotia travelled by road with the remaining 31.3% arriving by air.

Energy

Nova Scotia is not currently a substantial oil producer. Natural gas production in Nova Scotia is from two developments: Sable Offshore Energy Project and the Deep Panuke development. Both of these fields are beyond their peak of production and their output is declining, which is unrelated to the decline in oil prices.

The more substantial effect of lower oil prices has been on the Nova Scotia’s international trade. With lower oil prices since 2014, the Canadian dollar has depreciated significantly against the U.S. dollar since early 2013, and, in combination with rising domestic spending in the U.S. has provided support to Nova Scotia’s international exports, with the exception of energy products.

The majority of electricity generated in Nova Scotia is from coal and oil-fired facilities. Overall total electricity production from utilities and independent power producers in Nova Scotia for 2016 was 9,914 gigawatt hours, a 3.0% decrease in production from 2015. Total hydro, tidal, wind and solar generation was 1,907 gigawatt hours, a 4.2% increase over 2015. The Province of Nova Scotia’s regulations require that nearly 25 per cent of the province’s electricity supply come from renewable sources (wind, solar, tidal and biomass technology) in 2015, and has a target of 40% renewable electricity by 2020. The Province achieved the 2015 target, with the actual figure being 26.6 per cent as reported by Nova Scotia Power.

23

ELECTRIC POWER GENERATION (MEGAWATT HOURS)

| | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | |

| | | 2012 | | | 2013 | | | 2014 | | | 2015 | | | 2016 | |

Hydro, Tidal, Wind, Solar and other | | | 1,677,398 | | | | 1,784,229 | | | | 1,892,847 | | | | 1,829,565 | | | | 1,906,520 | |

Thermal generation | | | 9,428,660 | | | | 8,985,526 | | | | 8,748,063 | | | | 8,390,471 | | | | 8,007,834 | |

| | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | |

Total | | | 11,106,058 | | | | 10,769,755 | | | | 10,640,910 | | | | 10,220,036 | | | | 9,914,354 | |

| | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | |

Source: Statistics Canada, CANSIM Table 127-0007

Offshore Exploration and Development

Since the beginning of exploration activity in the late 1960’s, substantial gas reserves and modest oil reserves have been discovered, including the six fields that are part of the Sable Offshore Energy Project (“SOEP”), and the Deep Panuke field. In addition to the producing gas field, the SOEP project includes a gas plant at Goldboro and a fractionation plant at Point Tupper. The Maritimes & Northeast Pipeline provides transportation of SOEP gas to markets in Nova Scotia, New Brunswick, and the northeastern United States. This pipeline originates at the “tailgate” of the gas plant in Goldboro, Nova Scotia, continues in a westerly direction and crosses the New Brunswick-Nova Scotia border near Tidnish, Nova Scotia. During 2016, production levels declined a further 9.1% from 2015 levels, and are down 76.1% from the peak production in 2002.

Encana’s Deep Panuke natural gas project is located approximately 109 miles off the coast of Nova Scotia. The natural gas is currently being processed on the production platform and exported to shore by a dedicated pipeline to the SOEP gas processing facility in Goldboro, and then the natural gas is fed into the Maritime and Northeast Pipeline. At the time of development, the Deep Panuke project was anticipated to have a mean production life of 13 years. The Deep Panuke project was expected to deliver between 200 million and 300 million cubic feet of natural gas per day. However, due to production challenges, Deep Panuke production averaged only 58.3 mmcf/d in 2016. The Deep Panuke project has encountered significant production challenges with water seeping into the wells. In 2015, Encana, the interest holder in Deep Panuke, decided to operate the field on a seasonal basis to capitalize on high winter gas prices in the New England market. In the spring of 2016, Encana decided to produce natural gas on a year-round basis. However, production during 2016 was 16.2% below 2015 levels.

NATURAL GAS PRODUCTION

| | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | |

| | | 2012 | | | 2013 | | | 2014 | | | 2015 | | | 2016 | |

SOEP Production (mmcf/d) | | | 207.8 | | | | 140.2 | | | | 145.1 | | | | 139.6 | | | | 126.6 | |

Deep Panuke Production (mmcf/d) | | | — | | | | 46.2 | | | | 203.3 | | | | 69.7 | | | | 58.3 | |

| | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | |

Total Production (mmcf/d) | | | 207.8 | | | | 186.4 | | | | 348.4 | | | | 209.3 | | | | 184.9 | |

| | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | |

ExxonMobil Canada Properties Ltd., Shell Canada Ltd., Imperial Oil Reserves, Pengrowth Energy Trust and Mosbacher Operating Ltd. are interest holders in SOEP. In 1999, the project partners signed a royalty agreement for this project with the Province. The current year’s royalty income (considering current decommissioning costs as discussed below) from offshore gas and natural gas liquids for the fiscal year 2016-2017 was $9.9 million. In 2016-2017, the Province incurred Prior Years’ Adjustments (“PYA”) of negative $8.1 million – resulting in net royalty revenues of $1.8 million for 2016-2017. These PYAs arise from two sources: a) the recalculation of actual royalty income to be paid by the interest holders, and b) when the SOEP reaches the end of its technical viability, interest holders are entitled to deduct decommissioning cost from royalties paid to the Province. The Province has been accruing a liability for the Province’s share of the costs associated with the decommissioning of the project. When royalties estimated for future years are insufficient to fully offset the Province’s share of these costs, Prior Years’ Adjustments (“PYA”) are required for royalty revenue previously recorded.

24

OFFSHORE ROYALTY INCOME

| | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | |

| | | Fiscal Year Ended March 31 | |

| | | 2013 | | | 2014 | | | 2015 | | | 2016 | | | 2017 | |

Current Royalty Income (‘000) | | $ | 22,748 | | | $ | 20,732 | | | $ | 30,019 | | | $ | 14,068 | | | $ | 9,870 | |