EXHIBIT (f)(ii)

The 2015 Review of State Finances.

FORWARD-LOOKING STATEMENTS

This exhibit contains forward-looking statements. Statements that are not historical facts, including statements about the State of Queensland’s (the “State” or “Queensland”) beliefs and expectations, are forward-looking statements. These statements are based on current plans, budgets, estimates and projections and therefore you should not place undue reliance on them. The words “believe”, “may”, “will”, “should”, “estimate”, “continue”, “anticipate”, “intend”, “expect”, “forecast” and similar words are intended to identify forward-looking statements. Forward-looking statements speak only as of the date they are made, and neither the Queensland Treasury Corporation nor the State undertake any obligation to update publicly any of them in light of new information or future events.

Forward-looking statements are based on current plans, estimates and projections and, therefore, undue reliance should not be placed on them. Although the Queensland Treasury Corporation and the State believe that the beliefs and expectations reflected in such forward-looking statements are reasonable, no assurance can be given that such beliefs and expectations will prove to have been correct. Forward-looking statements involve inherent risks and uncertainties. We caution you that actual results may differ materially from those contained in any forward-looking statements.

A number of important factors could cause actual results to differ materially from those expressed in any forward-looking statement. Factors that could cause the actual outcomes to differ materially from those expressed or implied in forward-looking statements include:

| | • | | the international and Australian economies, and in particular the rates of growth (or contraction) of the State’s major trading partners; |

| | • | | the effects, both internationally and in Australia, of any further global financial crisis, any subsequent economic downturn, the ongoing economic, banking and sovereign debt crisis in Europe and any stalling of the protracted United States recovery; |

| | • | | increases or decreases in international and Australian domestic interest rates; |

| | • | | changes in the State’s domestic consumption; |

| | • | | changes in the State’s labor force participation and productivity; |

| | • | | downgrades in the credit ratings of the State and Australia; |

| | • | | changes in the rate of inflation in the State; |

| | • | | changes in environmental and other regulation; and |

| | • | | changes in the distribution of revenue from the Commonwealth of Australia Government to the State. |

Queensland Treasury

2015 Review of State Finances

2015 Review of State Finances

FOREWORD

In accordance with its 2015 election commitment, the new Government directed Queensland Treasury (Treasury) to undertake a Review of the State’s Finances, for publication as part of the first State Budget of the term.

The Review commenced in March 2015 with the purpose of reporting on:

| 1. | The State’s current fiscal position, including any relevant historical context and relative to peers. |

| 2. | The sustainability of the State’s fiscal position, including: |

| | • | | the appropriateness of various operating statement and balance sheet measures of State fiscal performance and sustainability |

| | • | | an assessment of the key drivers and likely direction of those measures based on medium term modelling work to be undertaken by Treasury. |

| 3. | The veracity of the current forward estimates, including: |

| | • | | adequacy of existing provisions on a “no policy change” basis |

| | • | | identification of any material outstanding funding issues requiring resolution |

| | • | | identification of any unallocated funding that may be available for other priorities, including debt repayment. |

| 4. | Based on the above findings, policies and actions required to support implementation of the Government’s five fiscal principles and related commitments. |

This Report is, in effect, a high level fiscal review. It is not intended as a comprehensive policy review covering matters of service delivery and performance. Comments on policy are largely restricted to those areas required to support implementation of the Government’s fiscal principles and strategy.

2015 Review of State Finances

TABLE OF CONTENTS

| | | | | | |

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY | | | 5 | |

| | |

1. | | ECONOMIC CONTEXT | | | 12 | |

| | |

2. | | QUEENSLAND’S FISCAL POSITION – 2000-01 TO 2013-14 | | | 20 | |

| | |

3. | | INTERSTATE COMPARISON OF KEY AGGREGATES | | | 45 | |

| | |

4. | | FORWARD ESTIMATES – ASSUMPTIONS AND RISKS | | | 54 | |

| | |

5. | | MAJOR FUNDING PRESSURES | | | 64 | |

| | |

6. | | CREDIT RATINGS AND DEBT MARKETS | | | 67 | |

| | |

7. | | FISCAL SUSTAINABILITY | | | 78 | |

| | |

8. | | GOC PERFORMANCE AND SUSTAINABILITY | | | 87 | |

| | |

9. | | THE GOVERNMENTS FISCAL PRINCIPLES | | | 97 | |

| | |

10. | | KEY ENABLERS OF THE FISCAL PRINCIPLES | | | 102 | |

| |

GLOSSARY OF TERMS | | | 105 | |

2015 Review of State Finances

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

ECONOMIC CONTEXT

For the last two decades, the Australian and Queensland economies have shown remarkable resilience despite a series of shocks. The Queensland economy outperformed the national economy throughout most of this period.

More recently, growth in Queensland’s economy has been driven by the significant investment in liquefied natural gas (LNG) projects. This overshadowed an underlying weakness in other sectors of the economy.

The Queensland economy now faces considerable challenges in the form of a weaker outlook for Queensland’s trading partners, a fall in the terms of trade and lower levels of business investment. This in turn is driving slower growth in incomes and spending.

Queensland’s population growth, which for some decades exceeded Australia’s due to strong levels of migration, has slowed to levels more in line with the national average.

The issue for policy makers at both the State and national level is how to facilitate growth in workforce participation and productivity to mitigate the impact of these factors on living standards at a time when governments are fiscally constrained.

QUEENSLAND’S CURRENT FISCAL POSITION

Queensland entered the last decade with a fiscal position that was the strongest of all the states. It had very low levels of debt and low tax rates.

The policy trade-off in Queensland was levels of service, infrastructure and public sector wages that were well below national averages.

Successive Queensland governments implemented policies aimed at raising service levels towards national standards in key areas and addressing infrastructure deficits. The benefit of that investment today (beyond the obvious service delivery benefits) is that Queensland is not facing the major infrastructure pressures now being experienced in many other states.

Queensland’s low tax settings remained in place during this period. There was a fundamental policy imbalance.

In the period leading up to the Global Financial Crisis (GFC), the policy imbalance was masked by the revenue surge from the housing and mining booms and the growth in GST driven by credit expansion. However, with state fiscal capacities equalised through the Grants Commission process, it is the policy settings that are paramount. In effect, like most governments throughout the developed world, Queensland ‘overshot’.

Queensland also faced the added challenges of the South East Queensland water crisis and an unprecedented series of natural disasters.

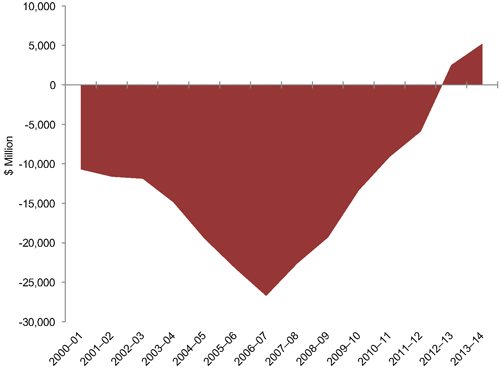

The net outcome was a dramatic increase in General Government debt between 2006-07 and 2013-14.

5

2015 Review of State Finances

Since 2008, there has been greater expenditure restraint and a series of remedial measures in the form of asset sales, tax increases, the imposition of successive rounds of generic ‘efficiency dividends’ and similar measures.

With a Budget dominated by employee expenses in deficit, a significant reduction in employee expenses was also required.

As a proportion of the population, the public sector is now the same size it was 2000-01. The growth in the public service between 2000-01 and 2013-14 was predominantly in front line service delivery roles.

At the time of the publication of the 2014-15 Mid Year Fiscal and Economic Review (MYFER), the budget and debt position had been broadly stabilised, but with little room for new policy. As is the case with the Australian Government and Western Australian budgets, Queensland faces ongoing revenue challenges associated with the rebalancing of world commodity prices.

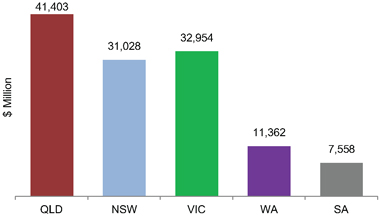

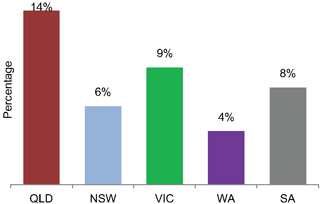

INTERSTATE COMPARISON OF KEY AGGREGATES

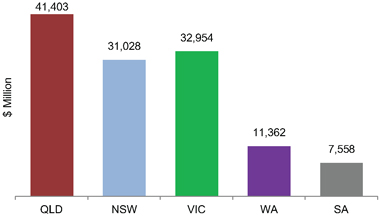

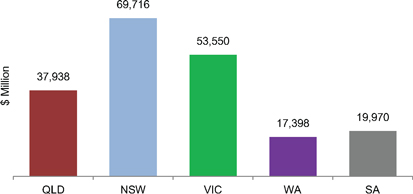

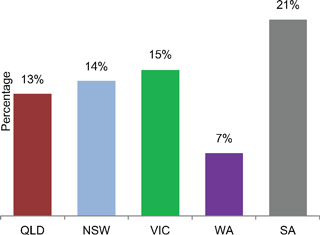

In terms of peer comparisons, Queensland’s General Government Gross Debt is the highest of all major states. Queensland also performs poorly on the General Government Debt to Revenue measure.

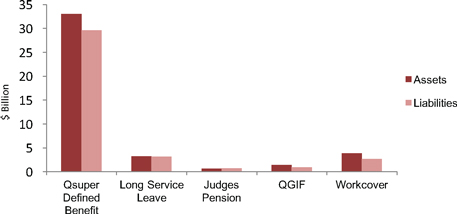

Queensland’s Net Debt position is far more favourable than its Gross Debt position, due to the significant financial investments Queensland holds to meet future employee entitlements, most notably the defined benefit superannuation scheme. These financial investments also see Queensland perform well on the Net Financial Liabilities measure.

Queensland ranks first among the major states on the Net Worth measure, but last on the Net Financial Worth measure. However, the utility of these measures for comparative purposes is questionable, due to differences in the composition and structure of government across jurisdictions and approaches to asset valuation.

FORWARD ESTIMATES – ASSUMPTIONS AND RISKS

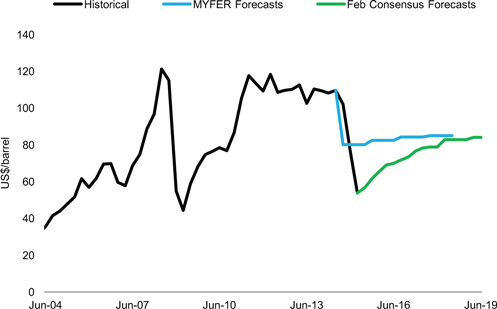

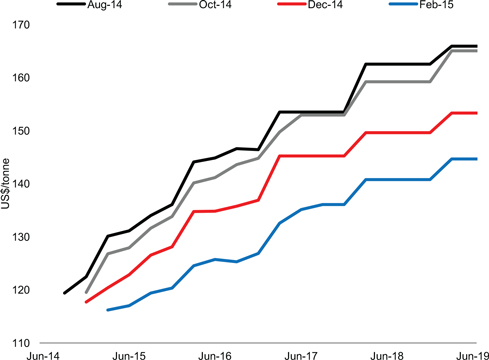

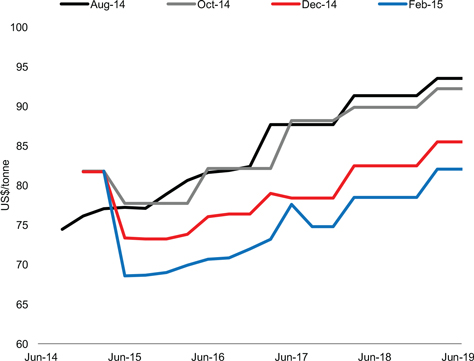

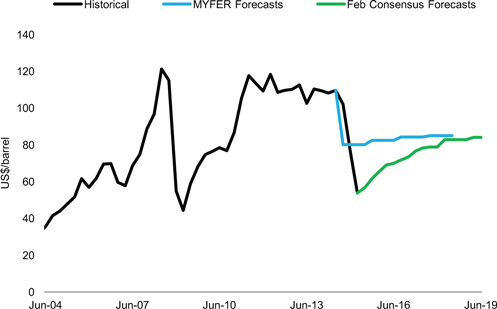

The estimates published in the December MYFER were fundamentally sound in terms of the assumptions. There have been developments since the publication of MYFER that will make the Government’s budget and debt reduction task more difficult. These are further reductions in Consensus Forecasts for coal and oil (linked to LNG) prices and the impact of the Australian Energy Regulator’s Determination of allowable revenues for Energex Limited (Energex) and Ergon Energy Corporation Limited (Ergon).

The bulk of the funding identified by the former Government as election commitment offsets was held by Treasury and reflected items where final decisions were yet to be made and a general policy provision for emerging items. This is available for allocation by Government, but is required by Queensland Health and Tourism and Events Queensland to maintain funding levels. While the inclusion of provisions has been standard practice since the introduction of accrual budgeting, a standard protocol should be put in place for communicating those provisions to the relevant departments when an election is called.

6

2015 Review of State Finances

MAJOR FUNDING PRESSURES

As part of the Review, Treasury liaised with Directors-General to identify current funding issues and future pressures that were not captured in agency forward estimates as part of the 2014-15 MYFER.

It is a standard part of the Budget process that agencies will identify a large number of issues for funding consideration that in totality far exceed the funding capacity of Government. The Budget process is designed to deal with those issues in terms of prioritisation and resolution.

The following could be described as the most significant funding pressures faced by the Budget having regard to materiality and likelihood.

| 1. | Health Funding – the challenges associated with the Australian Government’s move from an activity based funding model to a fixed contribution approach. |

| 2. | Cross River Rail – capacity constraints faced by the passenger rail network in crossing the Brisbane River. |

| 3. | Schools – new schools and additional classrooms to meet growth and a re-emergence of school backlog maintenance. |

| 4. | Prison Capacity – some new capacity is being added but could easily be exceeded if recent trends in the prisoner population continue. |

| 5. | Information and Communications Technology – a large number of the Government’s key systems and enabling technologies are past or approaching their end of life. |

| 6. | Tropical Cyclone Marcia – the cost of the damage will need to be incorporated into the 2015-16 Budget. |

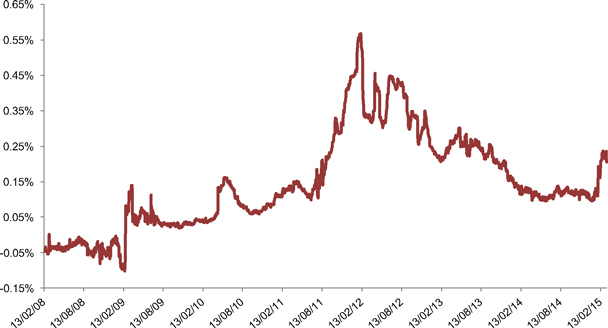

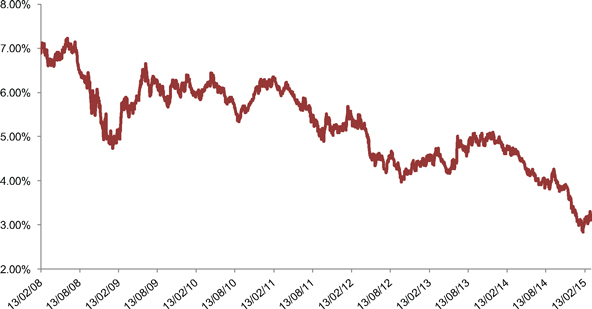

CREDIT RATINGS AND DEBT MARKETS

Queensland is currently rated AA+ by Standard & Poor’s with a stable outlook and Aa1 by Moody’s (equivalent to AA+) with a negative outlook.

While, based on the MYFER estimates, Queensland’s new borrowing requirements are relatively low, Queensland Treasury Corporation (QTC) has significant refinancing requirements on the State’s debt. The State has a refinancing requirement averaging approximately $10 billion per annum over the forward estimates.

The number of AAA rated entities has reduced dramatically since the Global Financial Crisis. Australia is now one of only eight sovereigns with a AAA credit rating.

It is difficult to be precise about the cost of Queensland being rated AA+ rather than AAA. Credit ratings are one factor that influence the relative cost of debt. Other factors include the volume of debt, the risk appetite of the market and investors’ views and perceptions.

Under current economic circumstances, it is neither necessary nor wise in terms of the magnitude of the policy adjustments required to pursue a return to AAA in the near term. It is however important for Queensland to have a strong and stable credit rating to ensure orderly access to capital markets at a reasonable price.

7

2015 Review of State Finances

There is ample liquidity in the markets and this has pushed yields to historic lows. However, internationally there is also evidence of significant imbalances in capital markets. Credit quality counts most during periods of market stress.

Queensland’s key credit weakness is its debt burden as measured by debt to revenue. Ratings agencies would be concerned about the re-emergence of material fiscal/cash deficits.

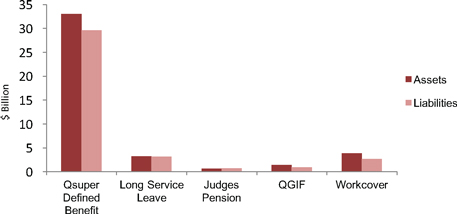

There has been an ongoing debate as to whether the ratings agencies give adequate weight to Queensland’s financial asset holdings. Queensland has over $30 billion in financial assets and is the only Australian state with fully funded public sector employee entitlements.

The fact remains that the State has the ability to give effect to a substantial reduction in debt should the circumstances require it.

FISCAL SUSTAINABILITY

Fiscal sustainability is important because:

| a. | it protects the community from the dislocation and uncertainty associated with significant policy corrections |

| b. | Government needs to have the financial capacity to help the community when needed most |

| c. | it ensures intergenerational equity. |

At the practical level, this is achieved by having principles and targets covering the Budget balance, debt and liability management.

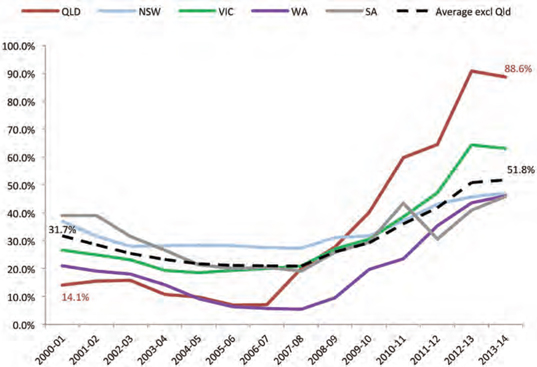

The net operating balance is the Government’s preferred fiscal measure. Most states have the net operating balance as their headline measure. Achieving a net operating surplus is a necessary, but not sufficient condition for fiscal sustainability in light of Queensland’s current debt levels.

Debt in itself is not ‘bad’. While it is widely accepted that states should not borrow for recurrent expenditure, it is entirely appropriate that Government borrow for new infrastructure to support service delivery and economic development – i.e. infrastructure that generates a strong social rate of return.

There is no clear and widely accepted empirical answer as to the appropriate amount of debt for a state government. However, Queensland’s current debt level leaves the State with little capacity to absorb external shocks and potentially vulnerable during times of financial market stress. For these reasons, the conclusion is that Queensland’s debt levels are too high.

Given: (a) the current economic environment and revenue outlook; (b) policy commitments and constraints; and (c) the inevitability that Government will face funding pressures that need to be addressed; a reduction in debt in absolute terms may not be achievable over the medium term.

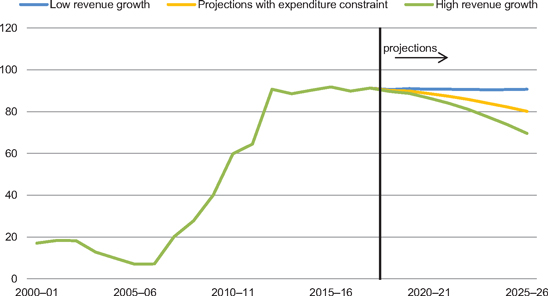

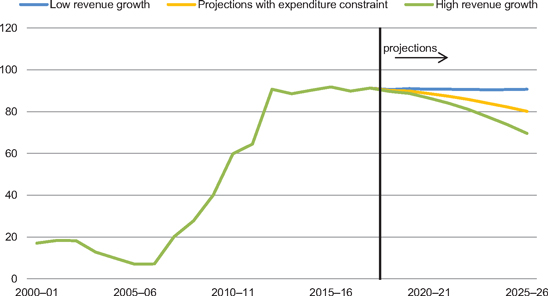

The most practical medium term objective may be for growth in the economy and revenues to reduce the relative size of Government debt over time – as measured by the General Government debt to revenue ratio.

8

2015 Review of State Finances

Treasury has modelled various scenarios under this approach. If the Government’s fiscal strategy ensures General Government debt grows at or below growth in real gross state product (GSP), then the ‘base case’ would see Queensland’s General Government debt to revenue ratio reduce from around 90% in 2015-16 to below 80% by 2025-26. Any debt reduction measures outside of the ‘base case’ would allow Government to pursue a more ambitious target.

Achieving the desired reduction in the relative size of debt will, at a minimum, require Government to: (a) target operating surpluses in the range of $1 billion to $2 billion; and (b) ensure the capital program is kept to a size where it is primarily funded through recurrent cash flow rather than borrowing.

The analysis is of course based on the current State tax and expenditure mix which in fact, is the heart of the sustainability problem.

For some years now, governments at the state and national level have been implementing a series of sub-optimal solutions in an effort to stabilise their budget situations. The enduring solution to the sustainability problem lies in recognising that Australia’s systems of taxation and fiscal federalism are broken. There is a fundamental mismatch between community expectations and the capacity of governments to deliver.

GOVERNMENT OWNED CORPORATIONS (GOCs) PERFORMANCE AND SUSTAINABILITY

As the lender to the GOCs, QTC reviews the capacity of the GOCs to service their debt – in effect, credit quality. The Queensland Government is the ultimate guarantor.

QTC’s assessment is that in general the businesses are of good credit quality. They are able to meet their debt service and repayment obligations and there is capacity to increase the gearing levels of some GOCs. Based on a ‘desk-top’ analysis, increasing their gearing to more commercial levels could release in the order of $4 billion in equity.

The equity released through the regearing would effectively represent a bring-forward of the Government’s six year debt reduction target for the General Government sector and provide capacity for Government to pursue a more ambitious improvement in the debt to revenue ratio.

CS Energy’s commercial position however, remains challenged. It is incurring operating losses due to long running coal supply and contractual issues.

Queensland Bulk Water Supply Authority (Seqwater) and Queensland Rail are entities which reside in the GOC sector, but are statutory bodies. These entities currently have $12 billion in debt.

Government could consider using some of the equity released from the GOCs to reduce Seqwater’s high debt levels and place it on a firm self-supporting footing.

Like any businesses, Queensland’s GOCs face risks and will have to adapt to sectoral changes – the biggest of which is arguably the impact of new technologies on the electricity network. If these are not managed well, the costs will be borne by the Budget and taxpayers.

9

2015 Review of State Finances

On the basis that the GOC sector debt is commercially sustainable, it is reasonable for the Government’s fiscal policy focus to be on the General Government sector. This however is subject to some important caveats. Namely, to be commercially sustainable they must:

| 1. | have commercially appropriate gearing levels and dividend policies |

| 2. | be allowed to price commercially |

| 3. | evolve and respond to changes in market conditions |

| 4. | make good investment decisions |

| 5. | not have non-commercial policies imposed on them. |

This has not been the case in the past. These elements are also important to the rating agencies’ positions on the status of the GOC debt.

THE GOVERNMENT’S FISCAL PRINCIPLES

The Government’s fiscal principles are sound in terms of coverage. However, based on the analysis contained in this document and developments since MYFER, some modifications are proposed. Treasury’s recommendations for the Government’s five fiscal principles, including those that remain unchanged, are as follows:

| 1. | The Government will target ongoing reductions in Queensland’s relative debt burden, as measured by the General Government debt to revenue ratio. [A medium term quantitative target could be considered as part of the development of the 2015-16 Budget] |

| 2. | The Government will target a net operating surplus that ensures any new capital investment is funded primarily through recurrent revenues rather than borrowing. |

| 3. | The General Government capital program will be managed to ensure a consistent flow of works to support jobs and the economy and reduce the risk of backlogs emerging. |

| 4. | Maintain competitive taxation by ensuring that General Government sector own-source revenue remains at or below 8.5% of gross state product, on average, over the forward estimates. |

| 5. | Target full funding of long term liabilities such as superannuation and WorkCover Queensland (WorkCover) in accordance with actuarial advice. |

KEY ENABLERS OF THE FISCAL PRINCIPLES

The merger of the transmission and distribution entities proposed by the Government should assist in driving efficiencies and returns to the Government as the shareholder.

There are a number of other key policies and actions that will be required to support the achievement of the Government’s fiscal principles.

Employee numbers need to be monitored closely with growth limited to that provided through existing funding formulae and election commitments.

10

2015 Review of State Finances

Wage growth needs be as closely aligned to inflation outcomes as possible. With the ongoing imposition of savings targets on agencies, it is difficult to see how genuine cashable productivity improvements that would be required to fund real wage increases could be achieved.

In Australia the revenue growth over the past two decades was such that it allowed for a familiar pattern: a problem is identified; Government accepts ownership of the problem; and, the solution is a spending package. The Government and the community at large will need to think laterally and develop solutions to problems beyond spending.

Generally, agencies have a good track record of managing within their budgets. However, they are under increasing pressure. To live within their budgets, Ministers and agencies need to continuously review and reprioritise.

Queensland now spends at levels at or around national averages in almost all service delivery areas. Where Queensland’s spending is not achieving the same results as in other states, Government and taxpayers have the right to know why.

The Government has a number of significant system related decisions to make over coming years. It is increasingly accepted that when the claim is that the ICT need is unique, it is easier and cheaper to change the business than build the system. Standardising processes so that Government can access private sector ICT as a service is not outsourcing.

The issue of the public ownership of GOCs has now been resolved. Nonetheless, the State has a vast balance sheet which needs to be managed actively to meet the Government’s debt objectives and future infrastructure needs. Treasury needs to work closely with QTC and QIC on these issues and develop proposals for Government’s consideration.

For the foreseeable future, Queensland will need to closely align its capital spending ambitions to the available cash flow generated by the budget. The focus needs to be on the most efficient way of achieving the outcome sought, rather than the pursuit of ‘the project’. The role of Building Queensland as the Government’s key infrastructure advisor will be pivotal.

The revenue bases of the states are already narrow. Further revenue concessions would be particularly harmful to Queensland’s credit rating position, as they damage both the numerator and denominator in key credit metrics. Moreover, the medium term fiscal challenge for Queensland is closer alignment between its revenue and expenditure settings.

11

2015 Review of State Finances

Economic growth is a key contributor to improving the standard of living of Queenslanders by increasing household incomes and therefore the quantity and quality of goods and services residents can consume and enjoy.

Queensland’s fiscal position needs to be considered in light of the underlying economic context to more fully understand the potential challenges that lie ahead.

| 1.1 | ECONOMIC GROWTH IN QUEENSLAND |

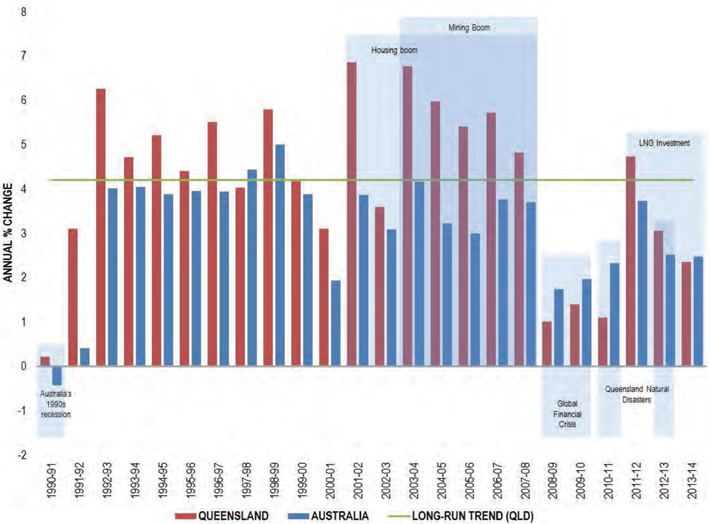

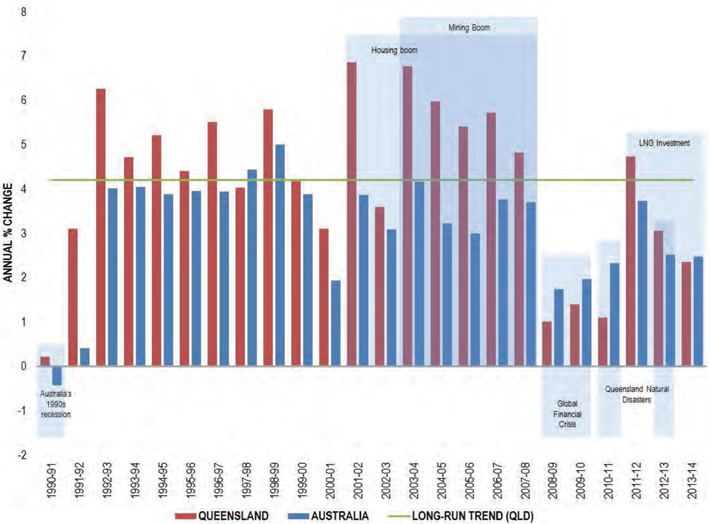

For the last two decades, the Australian and Queensland economies have shown remarkable resilience despite a series of external shocks. As shown in Chart 1.1 below, Queensland outperformed the Australian economy throughout most of this period.

Chart 1.1

Queensland’s Economic Growth Record

Source: Queensland Treasury; ABS 5206.0 and 5220.0

Following a period of only moderate growth in the early 1990s as a result of recessions in industrialised countries around the world, the Queensland economy was able to quickly rebound and embark upon a period of sustained economic expansion.

This turnaround was due, in part, to a swift recovery in dwelling investment as mortgage interest rates declined and growth in exports following a depreciation in the Australian dollar. A prolonged surge in business investment consolidated the recovery.

12

2015 Review of State Finances

While the Asian Financial Crisis hampered business and consumer confidence in 1997-98, a currency depreciation and monetary easing mitigated its impact on the domestic economy.

With a generous First Home Owner Grant and an expanding population, a seven-year housing boom began in 2001-02. During this period, house prices more than doubled and dwelling investment reached an historical high in 2007-08.

Queensland was well placed to benefit from the commodity boom of the early 2000s. Over the decade to 2007-08, raw coal production rose 74%, while production expanded from new zinc, lead and copper mines. Rising optimism also saw business investment record annual growth in excess of 10% per annum between 2002-03 and 2007-08.

Strong economic activity contributed to robust labour market outcomes, with the State’s unemployment rate falling to 3.7% in 2007-08 – a post World War II low. However, wages and price pressures were mounting.

With the onset of the GFC, dwelling investment declined and consumption growth weakened. As the economies of Queensland’s major trading partners slowed, Queensland’s total exports fell. Higher interest rates, an appreciation of the Australian dollar, the severe drought between 2004 and 2007, and the 2008 and 2009 natural disasters also exacerbated the fallout, as demand for labour moderated and unemployment rose.

Over much of the period since the GFC, the Queensland economy has been hindered by subdued global economic conditions and ongoing strength in the Australian dollar. The economy grew by an average of only 0.8% per annum between 2008-09 and 2010-11, before strengthening to an average of 3.3% per annum between 2011-12 and 2013-14.

The more recent expansion was driven by a recovery in coal exports and a significant increase in business investment as a result of the construction of three LNG projects. However, the LNG investment masked weakness in the other sectors of the economy.

The Queensland economy now faces considerable challenges in the form of the weaker outlook for Queensland’s major trading partners, a significant decline in the terms of trade and lower levels of business investment. This, in turn, is driving lower growth in household incomes and spending.

Queensland’s economic performance also continues to be impacted by longer-term underlying factors such as lower population and productivity growth, and a falling employment participation rate.

| 1.2 | DRIVERS OF ECONOMIC GROWTH AND INCOME |

Generally, economic growth is viewed and analysed from the perspective of output – consumption, investment and exports. However, given the primary objective of economic growth is to improve living standards of individuals, it is important to understand the inter-relationships among economic output, incomes and living standards.

The total output of an economy is the generator of, and equates to, the total income received through wages, profits and taxes.

13

2015 Review of State Finances

The income individuals receive is a measure of their standard of living, as it determines the quantity and quality of goods and services they are potentially able to demand and enjoy.

While demand will fluctuate and at times be heavily influenced by external factors (e.g. the international economy), growth in demand will only be sustainable if the population has the capacity to provide the quantity and quality of labour necessary to support the growth in output.

Therefore, in terms of Government policy development, an alternative framework for analysing economic growth is to examine the contributions made by the economy’s population on the supply side.

Under this framework, economic growth can be disaggregated into contributions from three elements – population, participation and productivity.

Table 1.1

Measuring Economic Growth

| | | | |

Element | | Measure | | Description |

| Population | | Population aged 15 years and over | | The more people of working age in the economy, the greater the potential workforce to grow the size of the economy. |

| | |

| Participation | | Extent to which the working age population are employed. | | The more people participate in work, the greater the size of the economy, higher incomes received and quality of life experienced. |

| | |

| Productivity | | Average output produced per hour worked | | As workers are able to produce more with each hour worked, the economy grows, and incomes and quality of life also increase. |

Population Growth

Overall population growth is a function of three factors: the natural population increase (births less deaths); net interstate migration; and net overseas migration.

The age structure is also a significant factor in the relationship between population and economic growth, given the population aged 15 and over primarily constitutes the pool of people from which the labour force is formed. Labour force participation rates are highest for middle-aged cohorts and drop off sharply for older cohorts.

The relative size of different age cohorts can also affect the economy’s industrial structure, e.g. younger age cohorts require more education and older age cohorts generally require greater levels of health and residential care.

Employment Participation

Employment participation reflects a combination of three factors:

| • | | the proportion of the population in the workforce (the labour force participation rate) |

| • | | the proportion of the workforce employed (the employment/unemployment rate) |

| • | | the number of hours worked (reflecting the proportion of employed persons working part time, full time or overtime). |

14

2015 Review of State Finances

Labour Productivity

Labour productivity measures the amount of economic output produced on average per hour worked in the economy. Increases in labour productivity over time can occur through capital deepening (increases in the capital to labour ratio), efficiency improvements (making better use of existing labour and capital) and technological improvements.

Structural changes in the economy, in particular changes in industry structure, are important factors influencing changes in labour productivity, with more capital-intensive industries (e.g. mining and manufacturing) generally leading to increased output per unit of labour employed. Conversely, growth in more labour-intensive sectors (e.g. health and community services, tourism and hospitality) moderate potential increases in labour productivity.

Terms of Trade

Another important factor contributing to both overall economic growth and changes in average incomes is the prevailing terms of trade (i.e. the price of the State’s exports relative to its imports).

Changes in Queensland’s terms of trade over time reflect movement in the relative prices of traded goods and services. The significance to Queensland of its key export-orientated industries means the State’s economic income is likely to be influenced more by changes in the terms of trade than other states.

15

2015 Review of State Finances

| 1.3 | QUEENSLAND’S ECONOMIC PERFORMANCE |

Relative Contribution to Growth

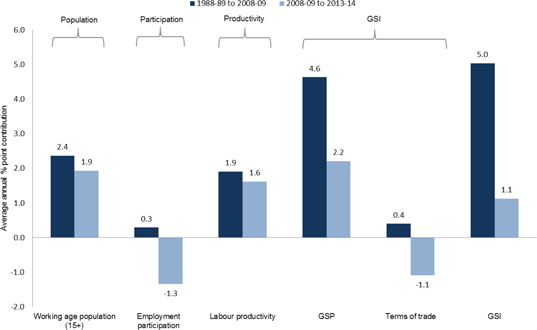

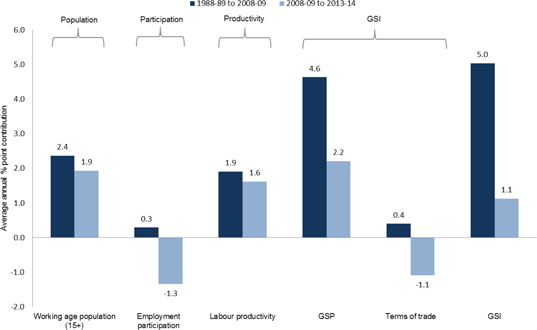

Chart 1.2 shows the relative contributions made by each of these elements to Queensland’s economic growth, and Gross State Income (GSI), over the last 25 years.

Chart 1.2

Drivers of Real Economic and Income Growth, Queensland

(1988-89 to 2013-14)

Source: Queensland Treasury; ABS 3101.0 and 6202.0

The key drivers of economic and income growth over recent decades have been population growth and increases in labour productivity, with employment participation and terms of trade also contributing, albeit relatively marginally, to overall growth outcomes. Specifically:

| • | | working age population growth over the last 25 years has averaged 2.2% per year, driven by historically high interstate and overseas migration for much of the period |

| • | | female workforce participation increased from 49.8% of the working age female population in 1988-89 to 60.3% in 2013-14 |

| • | | consistent with the rest of Australia, Queensland has experienced high rates of productivity growth over the past 25 years, averaging 1.9% per year, due to a range of factors, including capital deepening, technological change, policy reform and changes in industry structure |

| • | | high commodity prices initiated a sharp rise in the State’s terms of trade between 2002-03 and 2010-11, although much of these gains have since been reversed. |

In line with the weaker growth experienced in recent years, the contribution from each of these growth drivers has been significantly different since the GFC.

To illustrate this point, Chart 1.2 above compares the contribution to growth of each factor over the 20 years from 1998-89 to 2008-09 with the contribution in the five years from 2008-09 to 2013-14.

Population Growth

Key drivers of population growth have slowed, reducing the number of people being added to the State’s labour force each year.

16

2015 Review of State Finances

In particular, while Queensland’s population growth during the 2000s was underpinned by strong rates of interstate and overseas migration, net interstate migration has fallen significantly over the last decade.

Net interstate migration averaged 29,000 people per year over the 20 years to 2008-09, compared with only 7,600 per year over the five years to 2013-14. Queensland recorded only 5,753 net interstate migrants in 2013-14, the lowest level since records began in 1981-82.

This likely reflects a range of factors, including the maturing of the Queensland economy, with the differential in house prices and cost of living between Queensland and other major states having reduced over time. In addition, the reduced employment opportunities in Queensland relative to other states, in particular, Victoria and New South Wales, has also reduced the relative attractiveness of Queensland as a migration destination.

Employment Participation

The most significant change in recent years has been the detraction from growth from lower employment participation.

Queensland’s labour force participation rate peaked at 67.8% of the working age population in 2008-09 and has since fallen to 65.9% in 2013-14.

In contrast to the strong growth in female participation in the 1990s and 2000s, this rate has more recently fallen.

The ageing of Queensland’s population also appears to be having a negative impact on employment participation rates as a greater proportion of the population exits the labour force.

The proportion of the population aged 15 to 64 peaked in 2007-08 at 67.5% and has since fallen to 66.2%. Over the same period, the proportion of the population aged 65 and over has increased from 12.2% to 14.0%.

Part time employment has grown by 97,400 persons since 2008-09, outstripping full time employment growth of 45,800 persons over the same period.

Some of the fall in the participation rate is likely to be accounted for by a ‘discouraged worker effect’ where rises in the unemployment rate over the period have led to some jobseekers leaving the labour force entirely. Youth have also been affected.

This rise in the unemployment rate can be largely attributed to external economic factors over the past five years, particularly the aftermath of the GFC. These factors are also likely to have contributed to the relative increase in part time employment, compared with full time employment, in recent years.

Labour Productivity

Labour productivity growth in the last five years has been marginally lower than in the previous two decades. More than $60 billion has been invested in the State’s coal seam gas industry during that time.

17

2015 Review of State Finances

In the absence of the coal seam gas development boom, the State’s labour productivity growth in the last five years would have reduced substantially compared with the average over the previous 20 years.

Terms of Trade

Finally, in relation to the terms of trade, it is significant that, over of the past decade, high global commodity prices have fed a boom in the construction of new mines and associated infrastructure in Queensland and elevated the terms of trade, increasing the rate of income growth accruing to Queensland.

However, the high commodity prices which initiated a sharp rise in the State’s terms of trade between 2002-03 and 2010-11 have fallen sharply over the last 18 months, negating some of these impacts and resulting in a substantial detraction from income growth over the last five years.

| 1.4 | QUEENSLAND’S ECONOMIC OUTLOOK |

Economic prospects for Queensland over the next decade will be driven by several key factors, including:

| • | | the performance of international and national economies |

| • | | the transition of the Queensland economy following the resources investment boom. |

The international outlook remains clouded with uncertainty. The pace of economic recovery in the United States is expected to be gradual while high levels of debt in a number of member countries will continue to be a drag on any substantial recovery in the Euro Zone.

In Japan, a declining population is expected to continue to constrain the country’s economic growth. Growth in China should also continue to moderate, as the Chinese Government aims to rebalance the economy, contain growth in local government debt and address environmental concerns. Taken together, these factors suggest that global economic growth is likely to remain below historical averages in coming years.

Meanwhile, migration flows have stabilised over the past few years and, as a result, Australia’s and Queensland’s population growth are expected to be lower than in the previous decade. These developments suggest that national and Queensland trend population growth are likely to stabilise at lower levels than their respective average historical growth rates.

Population growth in Queensland is likely to remain more in line with the national average in the foreseeable future and there is unlikely to be the same influx observed in the first decade of this century.

18

2015 Review of State Finances

The ageing of the population is expected to reduce labour force participation rates. This is also expected to see spending on health and aged care services rise significantly in the coming decade, both nationally and at a State level.

Over the next two years, the Queensland economy will be driven by the transition from the resources investment phase to the production phase. The sharp fall in LNG investment is the major factor restraining growth in 2014-15, but in 2015-16 there will be a rebound in growth as LNG production and exports ramp up.

The transition away from capital-intensive resources investment, combined with greater expenditure in the labour-intensive social services sector, is expected to limit potential growth in labour productivity.

The expected weakness in demand for resources, reflecting the soft international economic outlook, is likely to lead to continued downward pressure on commodity prices, with the terms of trade remaining at lower levels for the foreseeable future. While a number of policy levers that impact on the level of economic activity, such as monetary policy, are managed at the national level, the State Government has some influence in three key policy areas:

| • | | in recognition that the private sector is the principal engine of growth in the economy, a key focus of Government policy should be to create an environment conducive to business confidence and investment |

| • | | the Government also has a role, where appropriate, to support growth through policies aimed at more targeted, immediate employment generation and to address specific instances of labour market failure |

| • | | with the public sector comprising approximately 20% of the economy, ongoing efficiency improvements in the delivery of Government services are also critical to growth in overall labour productivity. |

19

2015 Review of State Finances

| 2. | QUEENSLAND’S FISCAL POSITION – 2000-01 TO 2013-14 |

Queensland’s fiscal position in the 1990s was by any measure the strongest of all the Australian states, largely due to the application of fiscal principles which became known as ‘The Trilogy’. While the wording changed over time, the three core elements remained:

| 1. | Fully funding long term liabilities such as superannuation and workers’ compensation |

| 2. | Borrowing only for assets that generated an income stream sufficient to service the debt |

| 3. | Maintaining Queensland as the ‘low tax State’. |

As a consequence, Queensland had balanced budgets and little to no General Government debt.

Unlike other states, as the ‘low tax State’ Queensland had no fuel tax (later converted into the Fuel Subsidy Scheme), no financial institutions duty and generous principal place of residence stamp duty concessions. Queensland’s tax rates were generally lower across the board.

Clearly, this could only be achieved if there was a trade-off. The trade-off in Queensland was levels of service, infrastructure and public sector wages that were well below the national average.

Since then, successive Queensland governments have sought to address these differences in service levels and standards. The low tax policies however largely remained.

There was also a significant surge in infrastructure spending.

For a time, the revenues generated by the housing and mining booms and the increases in GST revenues arising from the credit expansion made this appear affordable. However the process of fiscal equalisation, whereby all states are placed on a similar footing, means that over the medium term no state can at the same time pursue high expenditure and low tax policies regardless of how strong their economy is performing.

Queensland has also faced a number of severe weather events, first in the form of a protracted water crisis followed by severe floods and cyclones.

The GFC led to a significant collapse in revenues and highlighted the underlying policy imbalance. By that time, the infrastructure spending associated with earlier decisions was effectively ‘committed’.

The outcome was a rapid rise in Queensland’s debt levels. A significant policy correction was required.

Queensland governments have since implemented a range of measures in an effort to address the policy imbalance and stabilise the fiscal position. This task has been made harder due to the ongoing deterioration in the revenue outlook, particularly royalty revenues.

20

2015 Review of State Finances

The rest of this Chapter examines these issues in more detail, with particular reference to the last decade.

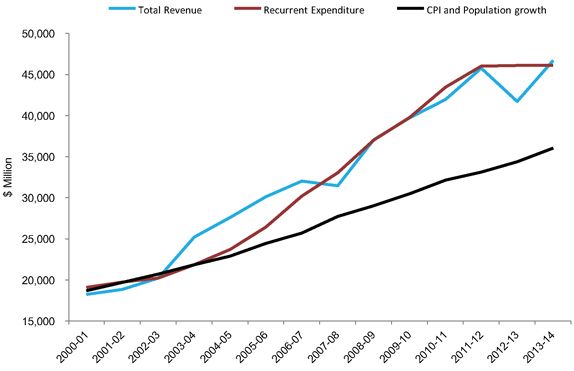

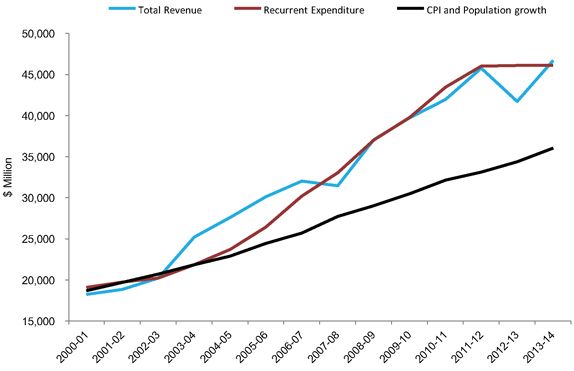

Between 2000-01 and 2013-14, General Government recurrent expenditure grew at an average rate of 7%. While clearly in excess of the combination of Consumer Price Index (CPI) and population growth, it aligns with revenue growth during that period.

On one level, this is not surprising. It is consistent with Queensland, on average, recording General Government operating surpluses throughout this period.

Chart 2.1

Total Revenue and Recurrent Expenditures

2000-01 to 2013-14

Source: ABS 5512.0; ABS 6401.0; Queensland Report on State Finances 2013-14

The growth rate of 7% per annum is by any measure large and can be explained by two factors:

| 1. | A number of major expenditure policy developments, including ongoing efforts to take Queensland’s expenditure levels towards national averages (See Box 2.1 below) |

| 2. | The recurring theme in the history of public finance of locking in expenditure in the expectation that the revenue boom will continue. |

21

2015 Review of State Finances

Box 2.1

Significant Expenditure Policy Developments

2001-02

| | • | | Breaking the Unemployment Cycle Initiative. |

2002-03

| | • | | Education and Training Reforms for the Future, including introduction of the Preparatory Year of Schooling. |

2004-05

| | • | | Child Protection Funding following the 2004 Crime and Misconduct Commission of Inquiry. |

2005-06

2006-07

| | • | | More Beds for Hospitals. |

| | • | | Queensland Skills Plan. |

2007-08

| | • | | Climate Change Package. |

| | • | | State Schools of Tomorrow. |

2010-11

| | • | | Flying Start – Move Year 7 to High School. |

2011-12

| | • | | 2018 Gold Coast Commonwealth Games. |

2012-13

| | • | | Royalties for the Regions. |

2013-14

| | • | | National Disability Insurance Scheme – Disability Services Shortfall. |

EMPLOYEE EXPENSES

The largest component of General Government expenditure is employee expenses, comprising nearly half of all expenditure. No analysis of trends in the State’s financial position would be complete without a more detailed examination of growth in this expenditure category.

Over the period 2000-01 to 2013-14, employee expenses grew at an average rate of 7.1%.

There are two components that determine growth in employee expenses: employee numbers and wages growth.

22

2015 Review of State Finances

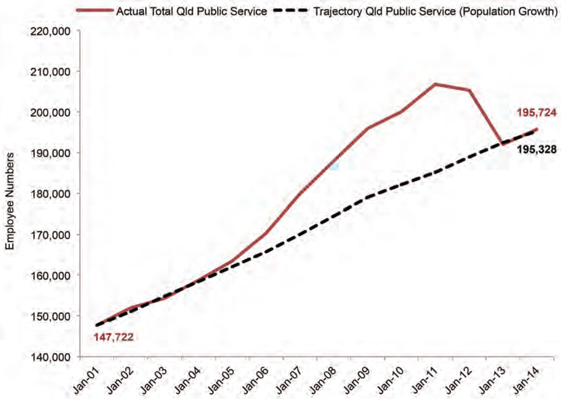

Size and Composition of the Public Service

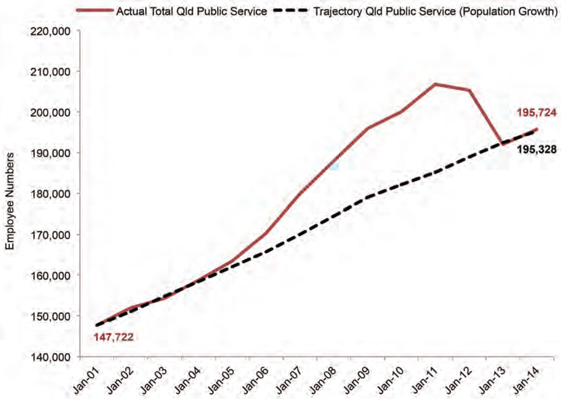

The Chart below compares growth in the public service compared to population growth over the period 2000-01 to 2013-14.

Chart 2.2

Actual Public Service vs Population Growth Trajectory

Jan 2001 to Jan 2014

Source: Public Service Commission - MOHRI data

Public sector numbers grew at a rate much higher than population in the period post 2005. The majority of that growth was in Queensland Health.

Following the reduction in employee numbers in 2012-13, as a proportion of the population the public sector is now the same size it was 2000-01.

23

2015 Review of State Finances

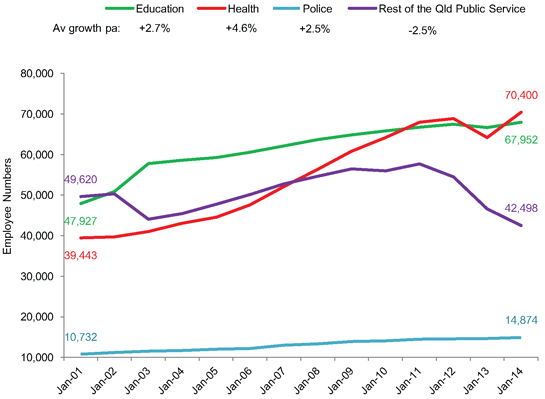

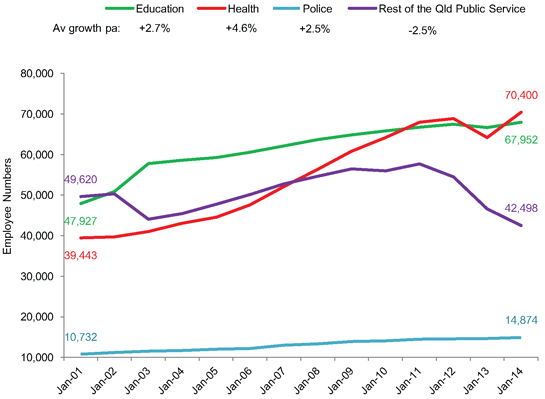

Chart 2.3

Composition of Public Service

2001 to 2014

Source: Public Service Commission

Growth in Education and Police department employee numbers has been consistent with population growth. This is not surprising given that their funding formulas are population driven (e.g. school enrolments, police to population ratio).

The overall trajectory would seem to be consistent with the major policy and expenditure pushes of Government during this period, rather than representing a fundamental problem around FTE management.

The exception to this is Queensland Health. Treasury’s view is that in the post 2005 period, Health had problems in relation to both internal systems and management culture in relation to FTE and Budget management. Health’s performance in this area has since greatly improved, particularly with the introduction of the Hospital and Health Services (HHSs).

With the ‘Rest of the Public Service’ declining in absolute terms from 50,000 to 42,000 over this period, this could infer that a higher proportion of the public service is now devoted to direct service delivery than was the case in 2000-01.

24

2015 Review of State Finances

While detailed occupational data for all groups is not available back to 2000-01, the Public Service Commission has been able to provide data on some special occupational groups back to 2002-03. Approximately 80% of the growth in the public service since 2002-03 relates to the occupational groups detailed in the Table below.

Table 2.1

Queensland Public Sector – Special Occupational Groups

| | | | | | | | |

Selected Special Occupational Groups | | Jun-03 | | | Jun-14 | |

Firefighters | | | 2,048 | | | | 2,366 | |

Ambulance Officers | | | 2,162 | | | | 3,551 | |

Teacher/Teacher aides | | | 40,960 | | | | 49,861 | |

Nurses | | | 16,021 | | | | 26,005 | |

Doctors | | | 3,118 | | | | 7,393 | |

Other Health Practitioners | | | 5,490 | | | | 9,326 | |

Police | | | 8,585 | | | | 11,492 | |

| | | | | | | | |

TOTAL | | | 78,382 | | | | 109,994 | |

| | | | | | | | |

Source: Public Service Commission

Wages Growth

In 2000-01, Average Weekly Earnings (AWE) for the Queensland public sector was $739, around $44 (or 5.6%) less than the comparable Australian average. Queensland was ranked fourth highest of the states. In 2013-14, AWE in the Queensland public sector was $1,292, which was very close to the Australian average of $1,293 for the public sector. This was the second highest of the states after Western Australia.

In real terms, Queensland public sector AWE increased by 19.4% during this period compared with the Australian average of 15.7%.

Table 2.2

Average Weekly Earnings 2000-01 to 2013-14

| | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | |

| | | | | Nominal $ | | | Real $(2013-14) | |

| | | Sector | | 2013-14 | | | 2000-01 | | | Change | | | 2013-14 | | | 2000-01 | | | Change | |

Aus | | Private | | | 1,077 | | | | 618 | | | | 459 | | | | 1,077 | | | | 882 | | | | 195 | |

| | Public | | | 1,293 | | | | 783 | | | | 510 | | | | 1,293 | | | | 1,118 | | | | 175 | |

NSW | | Private | | | 1,078 | | | | 670 | | | | 408 | | | | 1,078 | | | | 947 | | | | 131 | |

| | Public | | | 1,281 | | | | 836 | | | | 446 | | | | 1,281 | | | | 1,182 | | | | 99 | |

Vic | | Private | | | 1,026 | | | | 600 | | | | 426 | | | | 1,026 | | | | 848 | | | | 178 | |

| | Public | | | 1,228 | | | | 756 | | | | 472 | | | | 1,228 | | | | 1,068 | | | | 160 | |

Qld | | Private | | | 1,045 | | | | 593 | | | | 452 | | | | 1,045 | | | | 868 | | | | 177 | |

| | Public | | | 1,292 | | | | 739 | | | | 553 | | | | 1,292 | | | | 1,082 | | | | 210 | |

SA | | Private | | | 1,013 | | | | 576 | | | | 437 | | | | 1,013 | | | | 829 | | | | 184 | |

| | Public | | | 1,246 | | | | 764 | | | | 482 | | | | 1,246 | | | | 1,100 | | | | 146 | |

WA | | Private | | | 1,301 | | | | 590 | | | | 711 | | | | 1,301 | | | | 861 | | | | 440 | |

| | Public | | | 1,326 | | | | 723 | | | | 602 | | | | 1,326 | | | | 1,054 | | | | 271 | |

Tas | | Private | | | 1,216 | | | | 731 | | | | 485 | | | | 1,216 | | | | 1,022 | | | | 194 | |

| | Public | | | 840 | | | | 498 | | | | 342 | | | | 840 | | | | 696 | | | | 143 | |

Source: Queensland Treasury; ABS 6302.0

25

2015 Review of State Finances

These results are impacted by the changing relative composition of the public sector workforce (for example, the significant increase in relatively highly paid medical clinicians post 2005 has increased Queensland’s average compared to other jurisdictions).

The Wage Price Index (WPI) removes some of these effects by holding the quality and quantity of labour purchased by employers constant. The WPI for the Queensland public sector increased by 68.8% over the 14 years to December 2014, much the same as the Australian average of 68.5%. At the same time, Queensland private sector WPI increased by 62.2%.

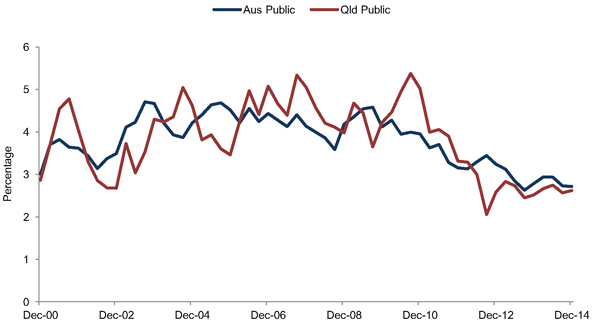

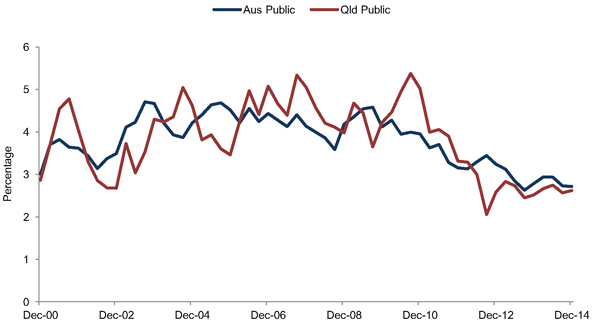

Chart 2.4

Wage Price Index, Australian and Queensland Public Sector

(annual % change, original)

Source: ABS 6345.0

26

2015 Review of State Finances

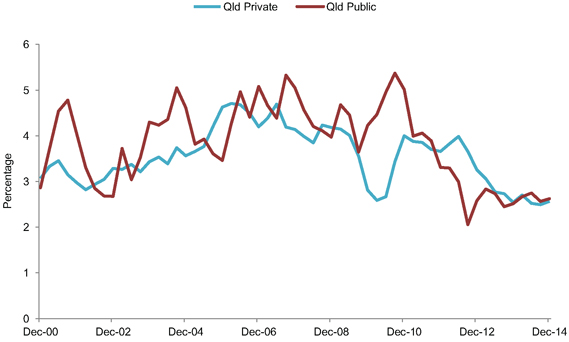

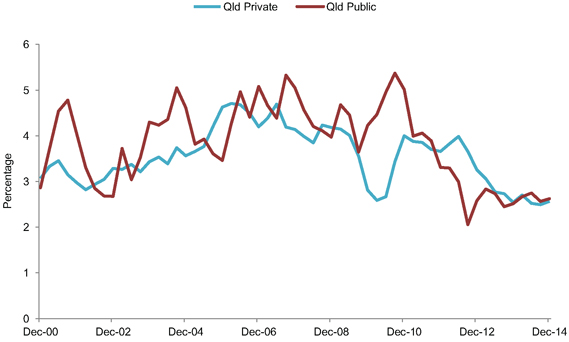

Chart 2.5

Wage Price Index, Queensland Private and Public Sector

(annual % change, original)

Source: ABS 6345.0

There are two recent significant deviations in the Queensland Public Sector WPI relative to the Queensland Private Sector WPI and the Australian Public Sector WPI. These are in 2008 and 2012.

In November 2008, the Government agreed to a three year wage increase of 4.5%, 4.0% and 4.0%. This increase was high even by wage outcomes at the time, particularly as the seriousness of the GFC was by then apparent. It also contrasts with the Queensland private sector response, which was a swift moderation in wage outcomes.

In 2012, the Government implemented a wages policy of 2.2% per annum. The 2.2% per annum increase has been lower than the actual change in the CPI and represents a reduction in public service real wages over the period. 2.2% is also lower than Treasury’s forward projections for CPI of 2.5% (mid-point of the RBA band), implying an ongoing real wage reduction. There was a protracted period in which the ‘core’ public service received no increase, which partly explains the sharp decline in 2012.

Conclusion

The growth in employee expenses over the period 2000-01 to 2013-14 was far in excess of CPI and population growth, but is explainable in the context of:

| 1. | Significant policy decisions in relation to Health, albeit that during part of this period there were also questions around Queensland Health’s FTE management |

| 2. | An increase in the compositional weighting towards more highly paid professions, and in particular health professionals as part of the 2005 Health Action Plan (HAP) |

| 3. | The general presumption that public sector salaries in key occupation groups should match the national average. |

27

2015 Review of State Finances

While the growth is explainable, it did not make it affordable. With significant fiscal deficits and employee expenses representing half of Government expenditure, Treasury’s conclusion was that a material reduction in employee expenses was required. The magnitude of that reduction was amplified by (a) the cost of the 2008 wage decision; and (b) the 2012 decision to fund election commitments through the imposition of a 3% employee expense growth cap.

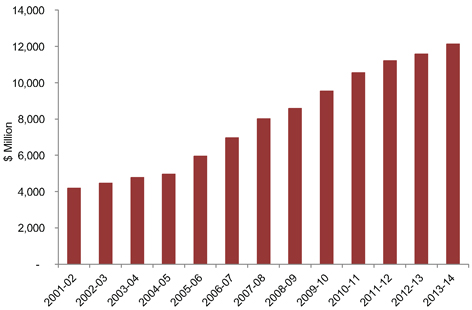

HEALTH

No Chapter on expenditure growth over the last decade would be complete without some commentary on Health.

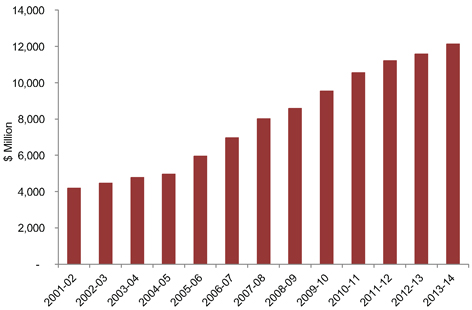

During the period 2001-02 to 2013-14, the health system received average year on year funding growth of 9.4% per annum. Operating expenditure for the health system in 2001-02 was $4.2 billion and grew to $12.1 billion by 2013-14.

Chart 2.6

Queensland Health Total Expenses

Source: Queensland Treasury

Growth in the period 2001-02 to 2004-05 was modest – in the order of 5% per annum.

The dramatic growth in expenditure from 2005 onwards was driven by two significant policy decisions:

| 1. | the HAP 2005-06 to 2010-11, developed in the wake of the Bundaberg Hospital Crisis |

| 2. | the More Beds for Hospitals Program (More Beds) 2006-07 to 2015-16. |

28

2015 Review of State Finances

The HAP committed funding of $6.4 billion over five and a half years ($4.4 billion additional in funding) to manage growing demand for health services. The program was targeted at sufficiently funding existing services, service expansion and enhancement and the recruitment of additional doctors and nurses.

The More Beds program replaced the HAP as the mechanism for providing additional operating funding to manage demand pressures. The key difference being that this commitment was infrastructure driven and underpinned by the delivery of an additional 2,000 hospital beds and $4.2 billion in funding over the period. The last tranche of growth funding under the More Beds program ceases in 2015-16.

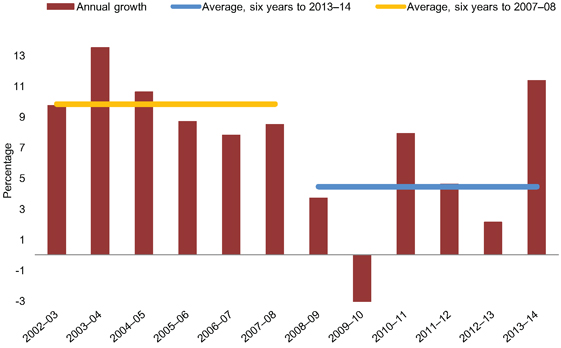

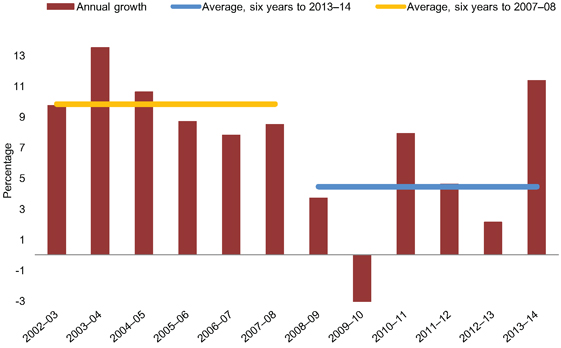

Average annual General Government revenue growth for the six years to 2007–08 was 9.2%. Following the GFC, average annual revenue growth slowed to 7.2% for the six years to 2013-14.

However, a large part of the growth post the GFC reflects Commonwealth Grants, both under the National Economic Stimulus program and the Australian Government contributions to disaster recovery following Cyclone Yasi and 2010 floods.

29

2015 Review of State Finances

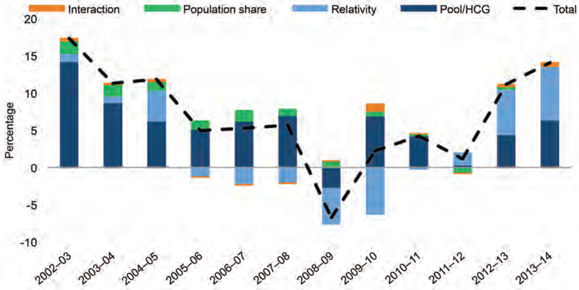

Accordingly, the Chart below shows how the key own-purpose revenue sources of GST, tax and royalties have grown since 2002-03. In aggregate, these revenue sources averaged 9.8% annual growth for the six years to 2007-08. This growth eased to 4.4% for the six years to 2013-14. The large increase in 2013-14 was primarily driven by an increase in Queensland’s relativity for the distribution of GST.

Chart 2.7

Queensland GST, Tax and Royalties Growth

Source: Queensland Treasury

GST Revenue

The amount each state receives in GST revenue is determined by: the size of the GST pool; its share of the national population; and its relativity determined by the Commonwealth Grants Commission (CGC).

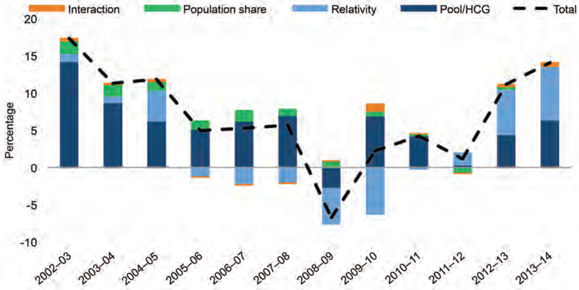

Queensland’s GST revenue grew by an average rate of 7.5% across 2001-02 to 2007-08. Growth in the GST pool was supported by strength in household consumption and dwelling investment activity, which were sustained by high levels of consumer confidence and partly funded by increases in household borrowings. Queensland’s relativity however declined as the mining boom delivered strong growth in royalty revenue. GST growth then eased to an average annual growth of 4.3% in the six years to 2013-14, as the global economic downturn weighed on domestic activity.

In 2012-13 and 2013-14, the strong growth in Queensland’s GST revenue was driven both by changes to Queensland’s relativity calculations resulting in the State receiving a greater proportion of the total nationwide GST pool and growth in the pool.

30

2015 Review of State Finances

Chart 2.8

Queensland Growth in GST Revenue

(General Government sector, percentage contribution to total growth)

Source: Queensland Treasury

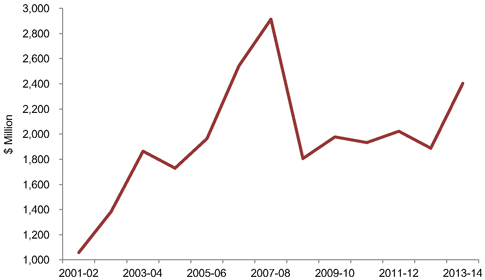

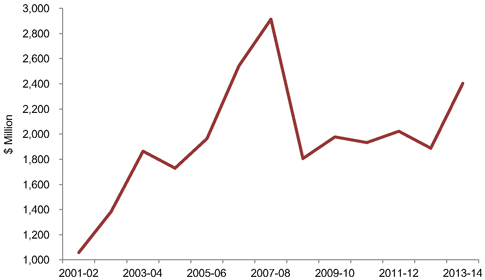

Taxation

Annual growth in transfer duty averaged 19.4% in the six years to 2007-08, driven by a range of factors including Queensland’s relative affordability of housing, high population growth and the impact of the burgeoning mining sector. This was a key contributor to total taxation growth of 12.2% per annum over this period.

The downturn in economic conditions following the GFC caused transfer duty to fall 38% in 2008-09, as business conditions eased and the housing market slowed. Transfer duty has since remained broadly at that level for several years. Strong growth in 2013-14 in part reflected duty on some major business transactions, including the sale of Queensland Motorways Limited (QML).

31

2015 Review of State Finances

Chart 2.9

Transfer Duty Revenue

Source: Queensland Treasury

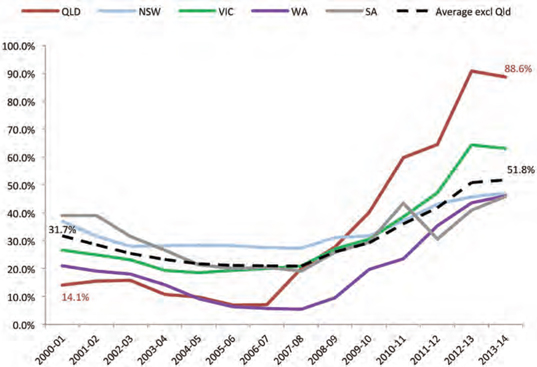

Royalty Revenue

The vast majority of Queensland’s royalty revenue is derived from coal exports.

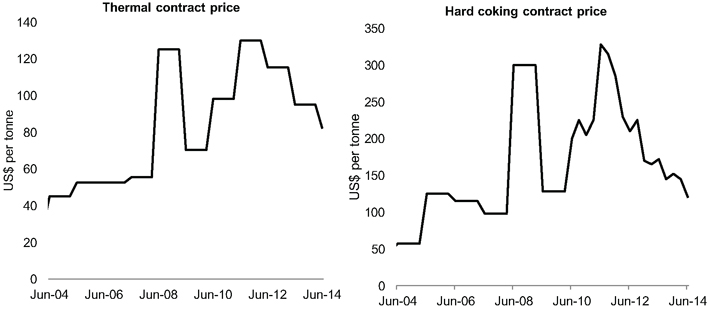

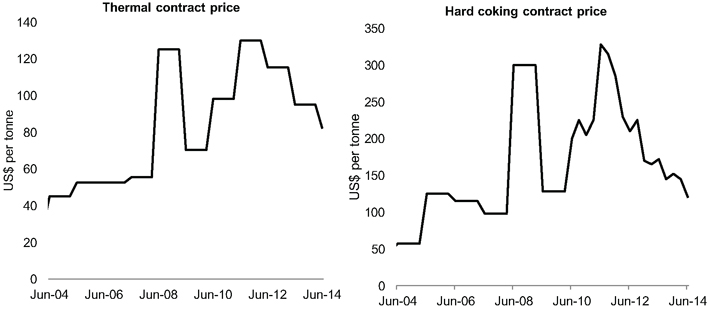

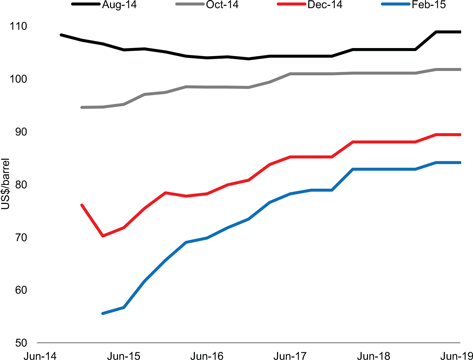

Royalty revenue grew strongly between 2000-01 and 2007-08, with growth of around 50% in both 2004-05 and 2005-06, due to a surge in the hard coking coal contract price. In contrast to the other own-source revenues, royalty revenues peaked in 2008-09. Floods in Queensland temporarily restricted supply and hard coking and thermal coal contract prices rose to US$ 300/t and US$ 125/t respectively, while the GFC drove a 17% depreciation in the Australian dollar (A$) in that year.

The locked-in contract prices resulted in coal royalties increasing by over 200% in 2008-09, as the higher prices also resulted in higher effective rates of royalties paid (with Queensland operating a progressive royalty rate system from 1 July 2008 – 7% of the coal price per tonne up to the first $100, and 10% for the balance of the price).

32

2015 Review of State Finances

Chart 2.10

Coal Royalty Revenue

Source: Queensland Treasury

Parameters unwound in 2009-10 with the A$ appreciating and coal contract prices falling. This more than offset the growth in coal export volumes and royalty revenue fell significantly. Coal royalties recovered somewhat in 2010-11 and 2011-12 as floods, Cyclone Yasi and industrial action restricted supply and temporarily boosted international coal prices. A higher A$ and lower production volumes however constrained the extent of the recovery in coal royalties.

Since then, coal prices have declined, and with the A$ remaining resiliently high for much of this period, royalty revenues fell in 2012-13. Coal royalties recovered slightly in 2013-14 as volumes increased and the A$ weakened.

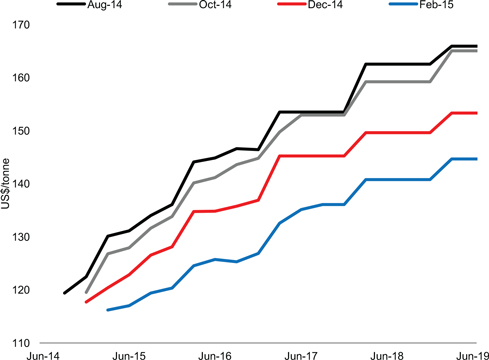

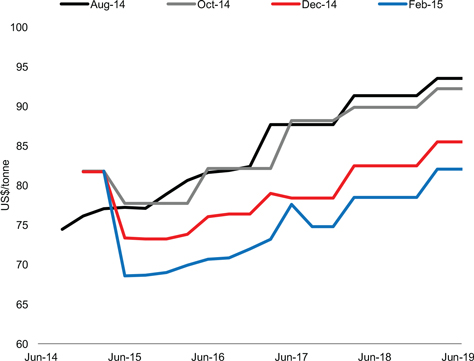

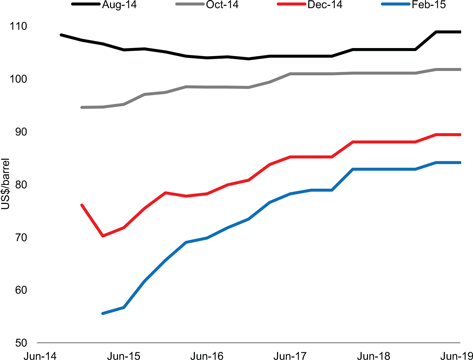

Chart 2.11

Coal Contract Prices

Source: Queensland Treasury; Consensus Forecasts

33

2015 Review of State Finances

| 2.4 | HORIZONTAL FISCAL EQUALISATION |

Any government managing state finances in Australia needs to understand the implications of Horizontal Fiscal Equalisation (HFE). The CGC advises the Australian Government on the distribution of GST revenue among the states based on HFE.

The objective of HFE is to distribute GST in a way that provides all states and territories with the same fiscal capacity to deliver a standard set of services – after taking into account jurisdictions’ expenditure needs and revenue raising capacities.

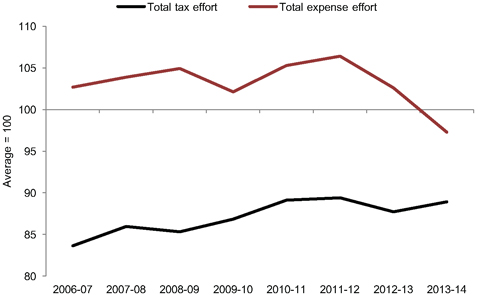

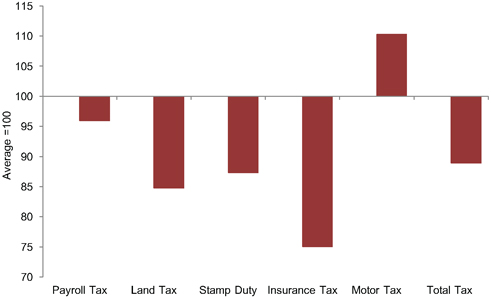

With revenues and expenditure equalised, it is a state’s policy settings that determines its relative budget outcomes. The Chart below uses CGC data to compare Queensland’s expenditure effort with its tax effort. For many years now, there has been a misalignment between the two.

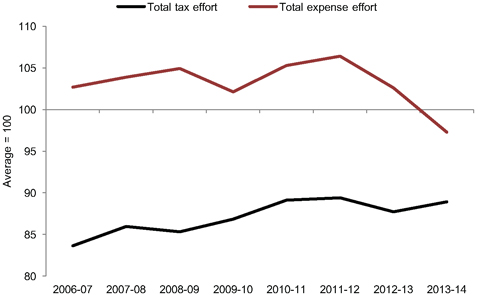

Chart 2.12

Comparison of Queensland Effort Ratios: Total Tax and Total Expenditure

Source: Queensland Treasury

Some of the remedial measures taken over recent years, and most recently the spending reductions in the 2012-13 Budget, have partially addressed the imbalance. The full year impact of those measures, which resulted in no growth in General Government expenditure in 2013-14, is shown in the above Chart. 2013-14 would be rightly regarded as an outlier.

34

2015 Review of State Finances

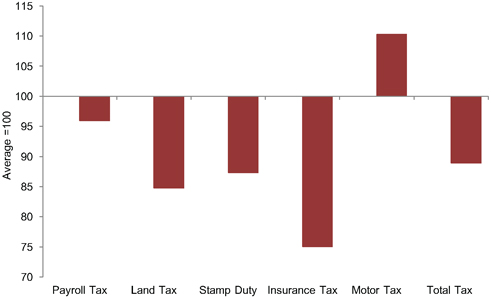

Generally, and with the notable exception of Disability Services (being addressed as part of the NDIS), Queensland’s expenditure effort is at or above national average levels, but its tax effort (85% to 90%) is below national average levels. The Chart below shows Queensland’s relative effort in the major tax categories assessed by the CGC.

Chart 2.13

Queensland Taxation Effort by Category

2013-14

Source: Queensland Treasury

This is important to understanding Queensland’s relative fiscal distress. To put this in context, had Queensland’s tax and expenditure effort been aligned over the decade 2003-04 to 2012-13, Queensland’s General Government debt would currently be in the order of $10 billion to $15 billion lower.

HFE is also important in the context of public debates about how states such as Queensland and Western Australia should ‘use’ their royalty revenues.

An economy that is performing relatively strongly in terms of generating revenue does not compensate for an imbalance in the revenue and expenditure policy mix or inefficiencies in service delivery. Western Australia’s credit rating was downgraded last year despite averaging real economic growth of 6% over the last decade – a performance that would probably put it amongst the strongest performing sub-national economies in the developed world.

The net impact of the HFE process is that royalty revenue is redistributed between all of the states and territories through their GST distribution. Higher royalty revenue in Queensland and Western Australia simply means less GST revenue for Queensland and Western Australia.

35

2015 Review of State Finances

The magnitude of Queensland’s capital expenditure effort during the period 2000-01 to 2012-13 is hard to overstate. Some of the more significant infrastructure project decisions taken during this time are detailed in the Box below. This does not include the South East Queensland (SEQ) water assets and natural disaster related expenditure which is covered separately.

Box 2.2

Significant Infrastructure Project Decisions

2000-01

| • | | Citytrain Rollingstock Programs. |

2002-03

| • | | Introduction of the Preparatory Year of Schooling. |

2004-05

2005-06

| • | | CityTrain MetTRIP Track Infrastructure Upgrades. |

2006-07

| • | | Education - Tomorrow’s Schools. |

2007-08

| • | | Lady Cilento Children’s Hospital (formerly Queensland Children’s Hospital). |

| • | | Sunshine Coast University Hospital. |

| • | | Gold Coast University Hospital. |

| • | | Queensland Rail Citytrain Rollingstock. |

| • | | Gateway Upgrade Project. |

| • | | State Schools of Tomorrow. |

2008-09

| • | | Brisbane Supreme and District Court Complex. |

| • | | Darra to Springfield Transport Corridor. |

| • | | Lotus Glen Correctional Centre. |

2009-10

| • | | Bruce Highway – Cooroy to Curra Upgrade. |

2010-11

| • | | Flying Start – Move Year 7 to High School. |

| • | | Cairns Base, Mackay Base and Townsville Hospital Redevelopments. |

2011-12

| • | | 2018 Gold Coast Commonwealth Games. |

2012-13

| • | | Upgrade of the Bruce Highway Package. |

2013-14

| • | | New Generation Rollingstock. |

36

2015 Review of State Finances

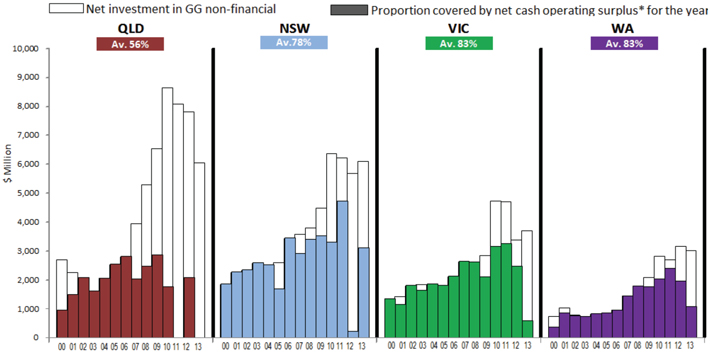

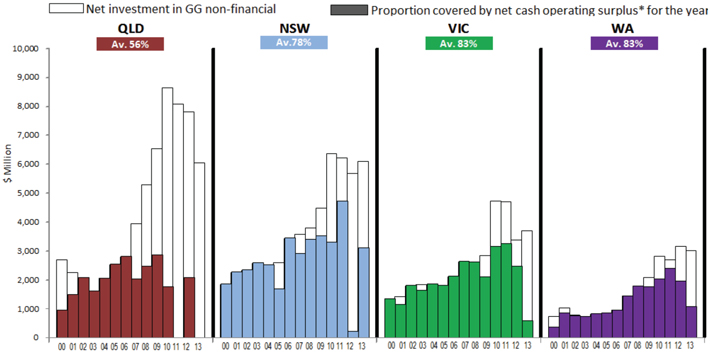

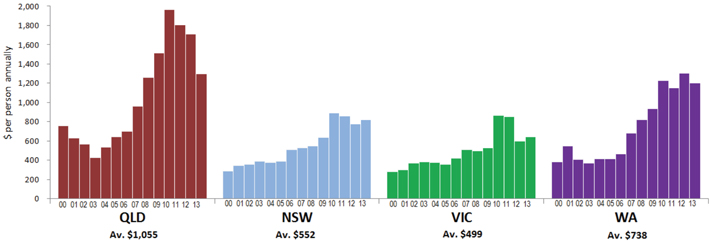

The best way to illustrate Queensland’s capital expenditure effort during this period is by comparing Queensland’s General Government capital expenditure to New South Wales, Victoria and Western Australia. This is shown below in both absolute and per capita terms. Queensland was outspending these states on both measures.

The first Chart also shows the proportion of the spending that was funded from recurrent sources – the cash operating surplus. In terms of reliance on borrowing to fund capital expenditure, Queensland went from no reliance, to partial reliance, to full reliance on borrowings.

Although the rapid increase in expenditure took place between 2006-07 and 2009-10, many of the decisions which gave rise to the expenditure were made in the earlier part of the decade. There is a considerable lag between major project instigation and peak expenditure. By the time the extent of the deterioration in the fiscal climate became clear, most of the projects were past the point where cessation would have represented a sensible public policy outcome. This was the case in pragmatic terms regardless of the merits or otherwise of the post GFC-stimulus arguments made at the time.

Chart 2.14

Net Investment in General Government Non-Financial Assets

1999-00 to 2012-13

Source: ABS; Government Finance Statistics Australia 2008-09 and 2012-13

37

2015 Review of State Finances

Chart 2.15

Net Investment in General Government Non-Financial Assets per Capita

1999-00 to 2012-13

Source: ABS; Government Finance Statistics Australia 2008-09 and 2012-13

While this Review focusses on the cost and the debt implications of the expenditure, there are also undeniable benefits. Queensland has less traffic congestion, better facilities, new hospitals, roads and bridges. SEQ water security is effectively underwritten for decades to come. Unlike in some states, there is minimal public discourse around an ‘infrastructure crisis’.

Just as the infrastructure program was a large part of the reason behind Queensland’s rapid rise in debt, the budget now needs to realise the benefit of that investment through much lower expenditure expectations for the foreseeable future.

If anything, with such a sizeable infrastructure footprint, there needs to be a reweighting of emphasis away from new projects and towards demand management measures and better maintenance of the existing asset base.

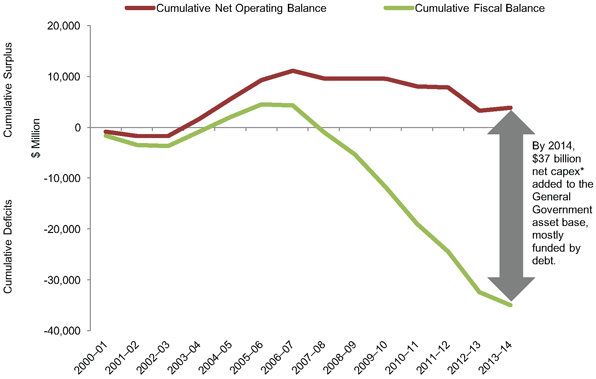

THE SOUTH EAST QUEENSLAND WATER CRISIS

From 2001 to 2009, SEQ experienced a prolonged drought. During this time, the combined levels of the region’s three chief water storages – Wivenhoe, Somerset and North Pine Dams – fell below 17%. Serious concerns were held around the security of SEQ’s water supply if the drought continued.

In August 2006, the Government approved a range of measures in response to the critical depletion of regional storages, including the construction of major new supply assets.

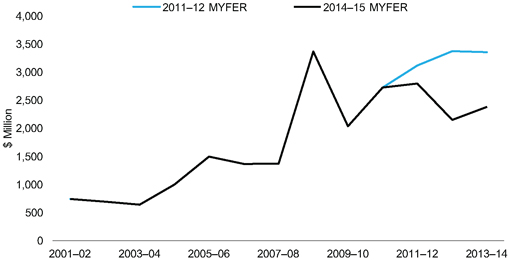

The drought-response assets included around 20 infrastructure projects, ranging from additional ground water supplies, the Gold Coast Desalination Plant, the Western Corridor Recycled Water Scheme and new dams and weirs. The Government also purchased SEQ council owned assets. Between 2006-07 and 2008-09 the State raised $7.4 billion in debt to pay for this water infrastructure.

The assets form the basis of the SEQ Water Grid.

38

2015 Review of State Finances

There will always be questions as to whether the pace and scale of the Government’s response was proportionate. However, there was a crisis and based on the information available to Government at the time a significant response was required.

However necessary the response was, it was nonetheless a significant blow to the State’s balance sheet and credit metrics.

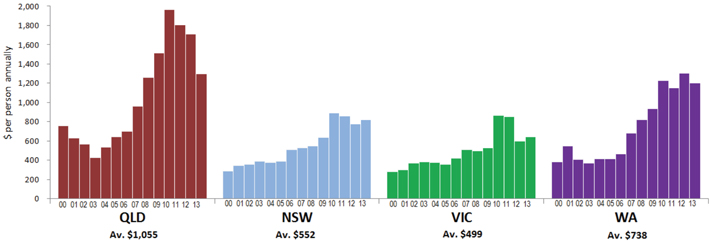

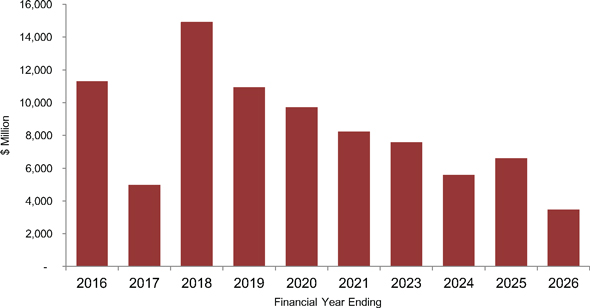

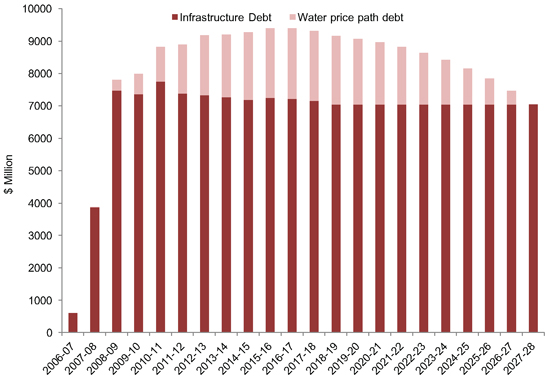

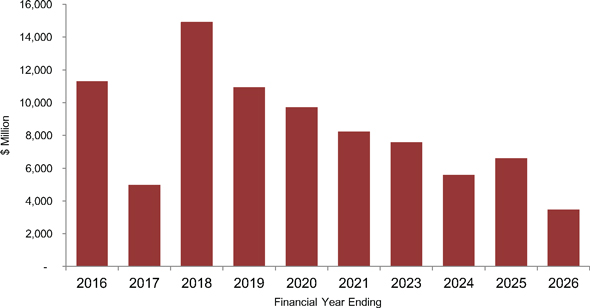

The assets were almost fully debt-funded. In order to mitigate the price impact on consumers, the Government instigated a ten year price path to cost reflective pricing. This means that water infrastructure related debt will peak at $9.4 billion, $2 billion above the cost of the assets, by 2015-16 before reducing as the price path progressively recovers the debt through water charges.

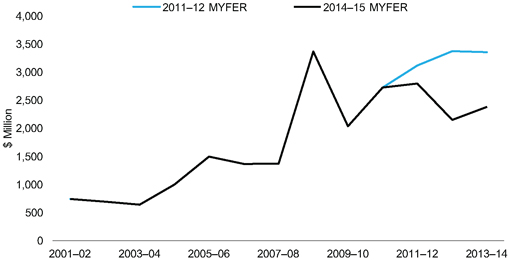

Chart 2.16

Debt connected with SEQ drought response

Source: Queensland Treasury, various sources

Unlike the debt held by the State’s Government Owned Corporations, the ratings agencies do not consider this debt to be self-supporting.

As history now shows, one of the most severe droughts in Queensland’s history was ended by one of the most severe floods in Queensland’s history.

39

2015 Review of State Finances

NATURAL DISASTERS

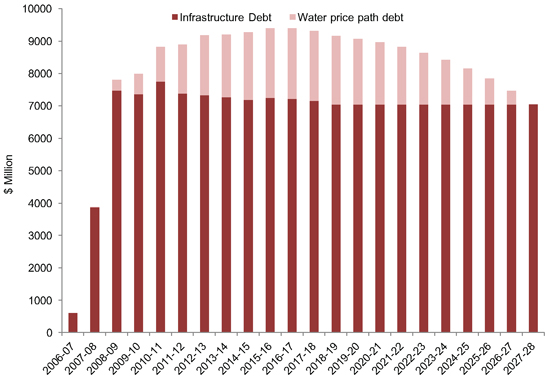

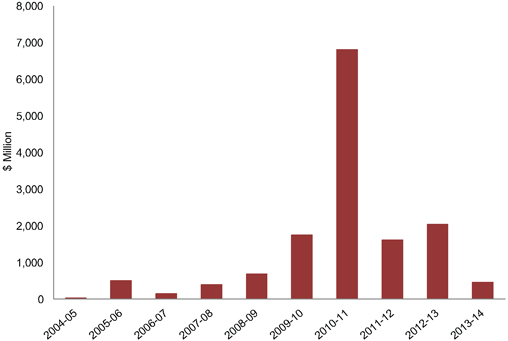

Chart 2.17

A Decade of Natural Disaster Events in Queensland – Costs

Source: Queensland Treasury

Queensland’s natural disasters have had a significant cost, in financial, economic and most importantly human terms.

In net fiscal terms though, the cost of this unprecedented series of natural disasters to the Budget is much less than the cost of the water grid. This is because the Australian federation, quite appropriately, has supportive risk sharing arrangements. Under these arrangements, and with certain thresholds and exclusions, the Australian Government contributes 75% towards the cost of repair and recovery.

The financial flows associated with the expenditure, and revenues from the Australian Government, have added an additional level of complexity to the presentation of Queensland’s fiscal position that continues to this day.

40

2015 Review of State Finances

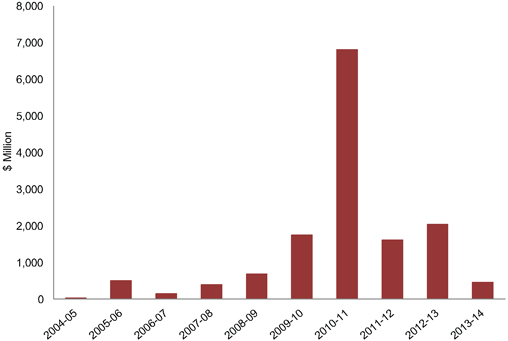

| 2.6 | BRINGING THE PIECES TOGETHER |

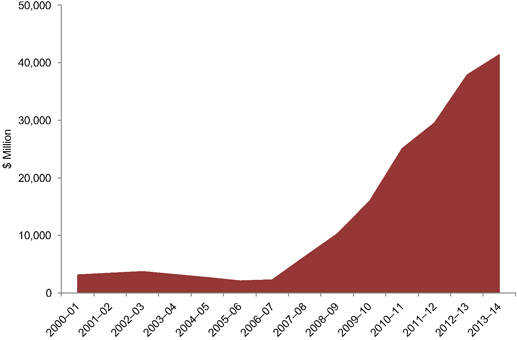

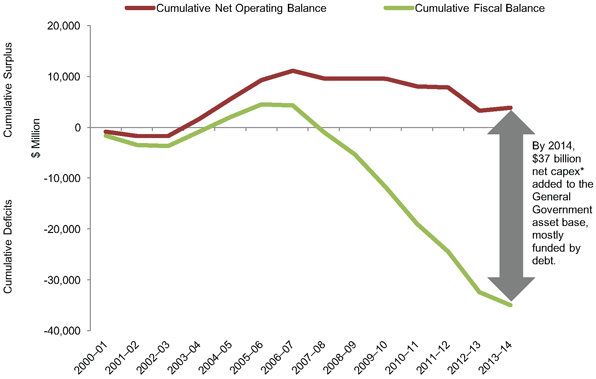

The Charts below bring together three key aggregates to illustrate the relationship between the operating surplus (recurrent revenue and expenditure), the fiscal balance (to incorporate capital expenditure) and debt. For completeness, the net debt balance is also shown.

There was a net operating surplus throughout much of the period 2000-01 to 2013-14, but the size of the operating surplus was insufficient to provide funding to support what can only be described as a historically significant surge in capital expenditure. As a consequence, the capital expenditure was funded increasingly by debt.

In other words, if the sole responsibility of the State was the provision of recurrent expenditure, an operating surplus would have been sufficient and Queensland would not have a debt problem. However, the State does have significant infrastructure responsibilities. The size of the operating balance needs to be proportionate to Queensland’s infrastructure obligations and ambitions.

Chart 2.18

Cumulative Net Operating Balance and Fiscal Balance

2000-01 to 2013-14

Source: Queensland Treasury

41

2015 Review of State Finances

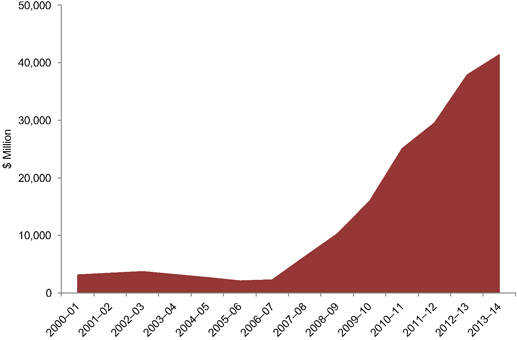

Chart 2.19

General Government Gross Debt Balance

2000-01 to 2013-14

Source: Queensland Treasury

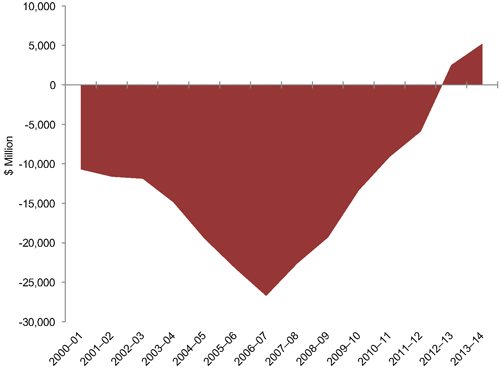

Chart 2.20

General Government Net Debt Balance

2000-01 to 2013-14

Source: Queensland Treasury

42

2015 Review of State Finances

Following the GFC and the subsequent downgrade in Queensland’s credit rating, there has been much greater awareness within Government of the causes of Queensland’s fiscal difficulties as outlined in this Chapter. Since then, successive governments have undertaken remedial measures in an effort to address/stabilise the situation. The significant remedial measures are detailed in the Box below.

There has also been greater restraint shown in relation to new expenditure, with the notable exception of the ultimately successful bid to host the 2018 Commonwealth Games. The decision to participate in NDIS was costly, but understandable in light of Queensland’s historic under-provision in this important area and the better standards of service and care it is intended to provide.

While election commitments have generally been ‘funded’, the funding offsets have been public sector savings – savings which otherwise could have contributed towards the budget repair task.

The culmination of these remedial efforts is a Budget and debt position that at the time of the 2014-15 MYFER had been broadly stabilised, but with little room for expansionary policy. As is the case with the Australian Government and Western Australian budgets, and although less significant in relative terms, Queensland faces ongoing revenue challenges associated with the ongoing rebalancing of world commodity prices and consequent adverse impact on mining royalty revenue.

43

2015 Review of State Finances

Box 2.3

Significant Remedial Measures1

Post 2008-09 Budget

2008-09 Major Economic Statement

| • | | Introduced a Public Sector Efficiency Target. |

| • | | Increased Motor Vehicle Registration Fees. |

| • | | Delayed the Abolition of Transfer Duty on Core Business Assets to 1 July 2012. |

| • | | Introduced a Land Tax Surcharge of 0.5% on aggregate land holdings in excess of $5 million. |

| • | | Closed the QSuper Defined Benefit Scheme to new members. |

2009-10 Budget

| • | | Abolished the Queensland Fuel Subsidy Scheme. |

| • | | Increased the Public Sector Efficiency Target. |

| • | | Further delayed the Abolition of Transfer Duty on Core Business Assets to 1 July 2013. |

| • | | Reduced Local Government Grants and Subsidies. |

| • | | A package of GOC Reforms aimed at increasing rates of return. |

| • | | Asset sales: Forestry Plantations Queensland; Queensland Motorways Limited; Port of Brisbane; QR Limited above and below rail coal business and assets; Abbot Point Coal Terminal. |

2010-11 Budget

| • | | Increased the Public Sector Efficiency Target. |

2010-11 Mid-Year Fiscal and Economic Review

| • | | Introduced a Voluntary Separation Program. |

| • | | Increased the Public Sector Efficiency Target. |

| • | | Removed the Principal Place of Residence Concession for Transfer Duty. |

2011-12 Mid-Year Fiscal and Economic Review

| • | | Increased the Voluntary Separation Program. |

| • | | Further delayed the Abolition of Transfer duty on Core Business Assets – until “the Budget can accommodate the abolition”. |

| • | | Introduced Cash Bidding for Prospective Exploration Land and applied Transfer Duty on the Transfer of Mining Tenures. |

2012-13 Budget

| • | | Major package of fiscal repair measures – comprising expenditure reductions, revenue measures and capital savings. This included a material reduction in the public service of 14,000 FTEs. |

| • | | Increased the Transfer Duty Rate for transactions valued at or above $1 million. |

| • | | Increased the Coal Royalty Rate on values above $100 per tonne. |

| • | | Restricted First Home Owner Grant to those buying or building new homes. |

2013-14 Budget

| • | | Increased the Duty Rate on General Insurance Products. |

| • | | Deferred the next Payroll Tax Threshold increase to $1.2 million to 1 July 2015. |

| • | | Extended the Urban Fire Levy to all property receiving a rates notice – renamed the Emergency Management, Fire and Rescue Levy. |

| • | | Increased the Public Sector Efficiency Target. |

| 1. | ‘Significant’ in this context are measures in excess of $50 million per annum. Does not include measures used to fund election commitments, as these did not contribute towards Budget repair. |

44

2015 Review of State Finances

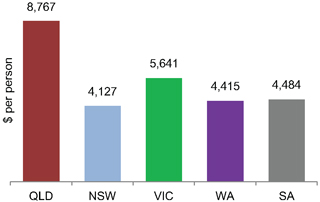

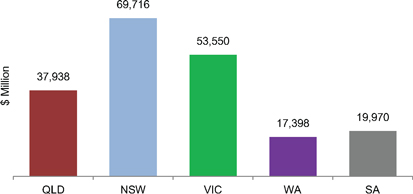

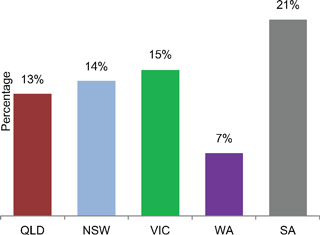

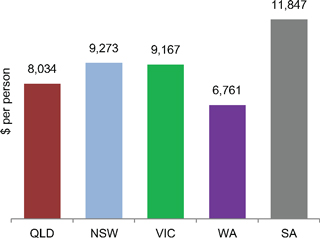

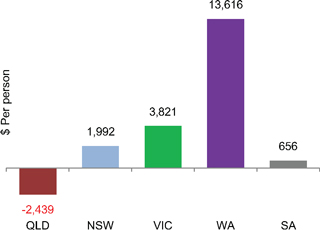

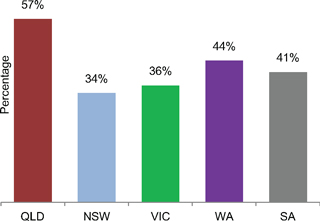

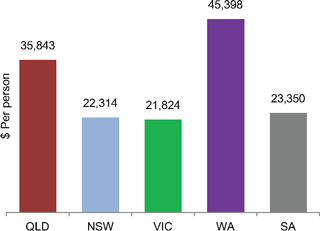

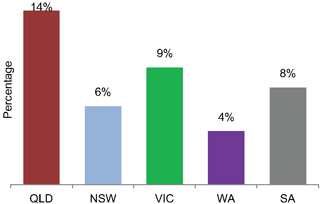

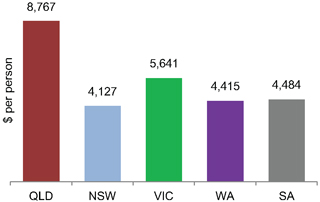

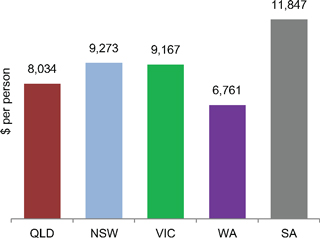

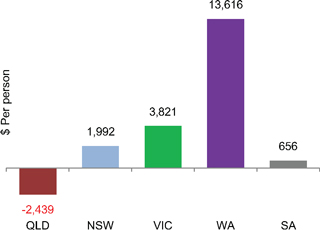

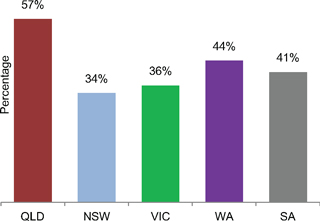

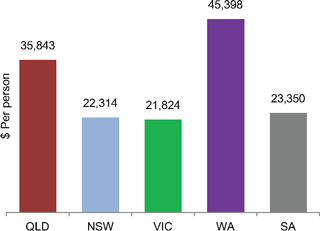

| 3. | INTERSTATE COMPARISON OF BALANCE SHEET AGGREGATES |