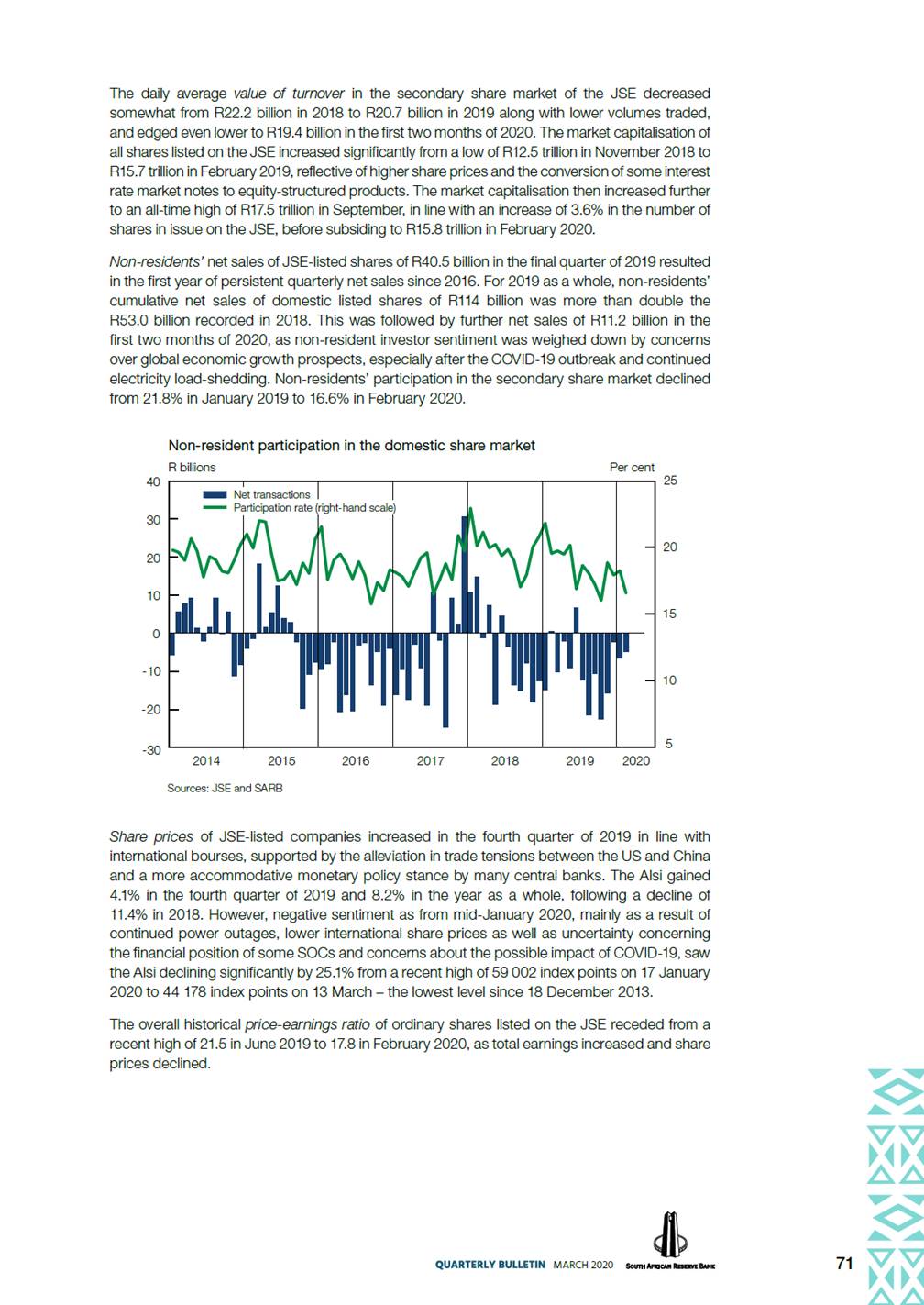

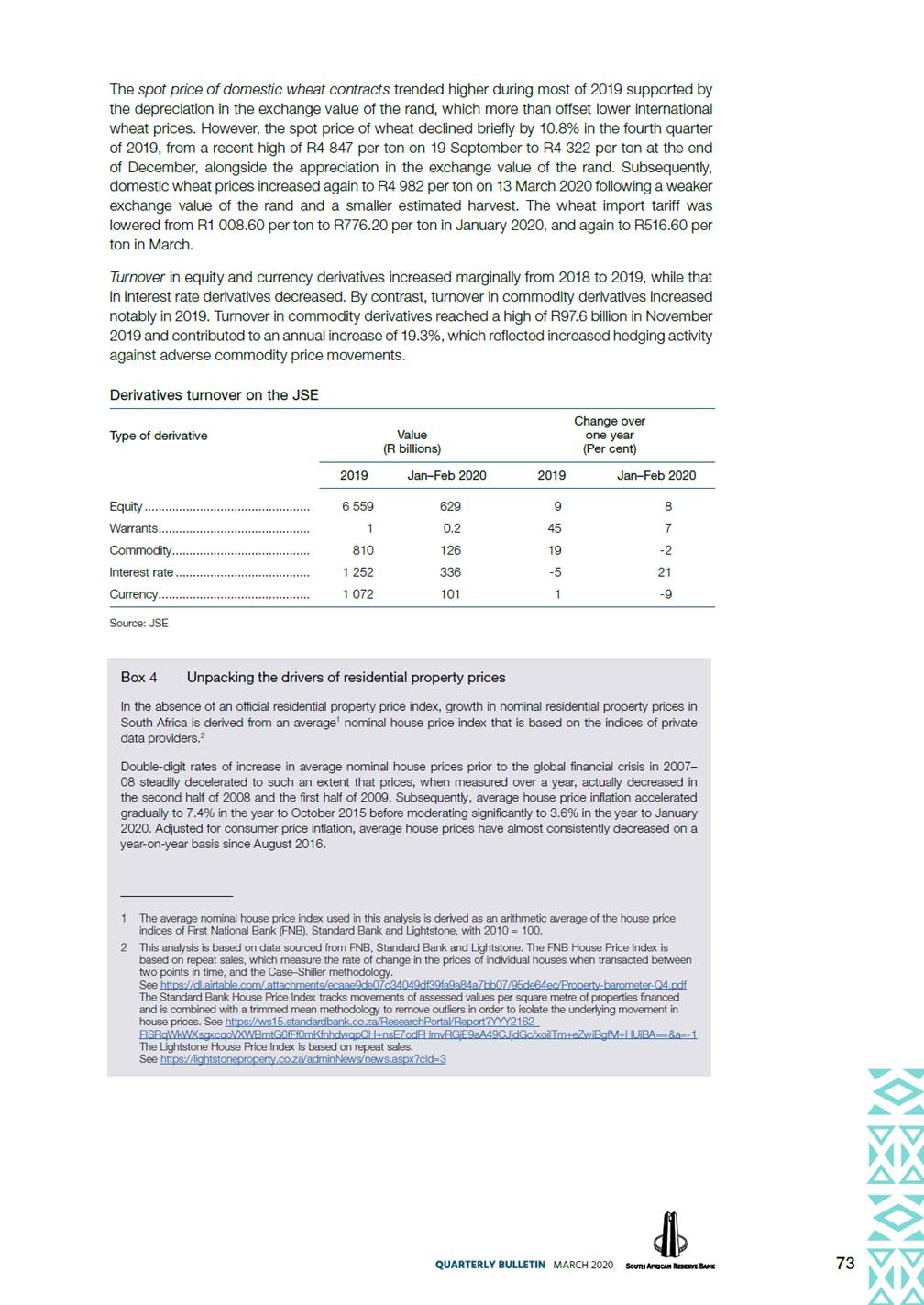

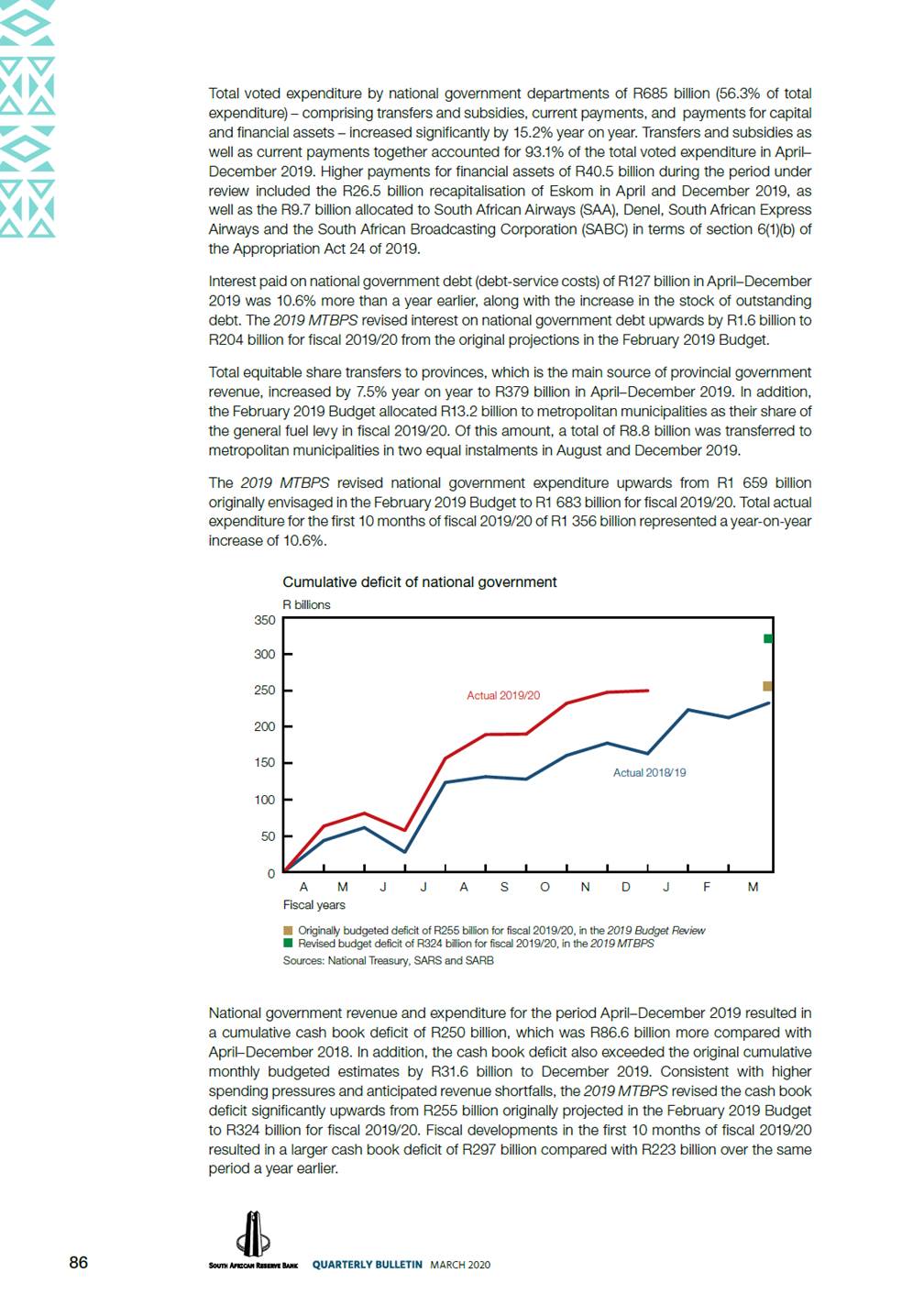

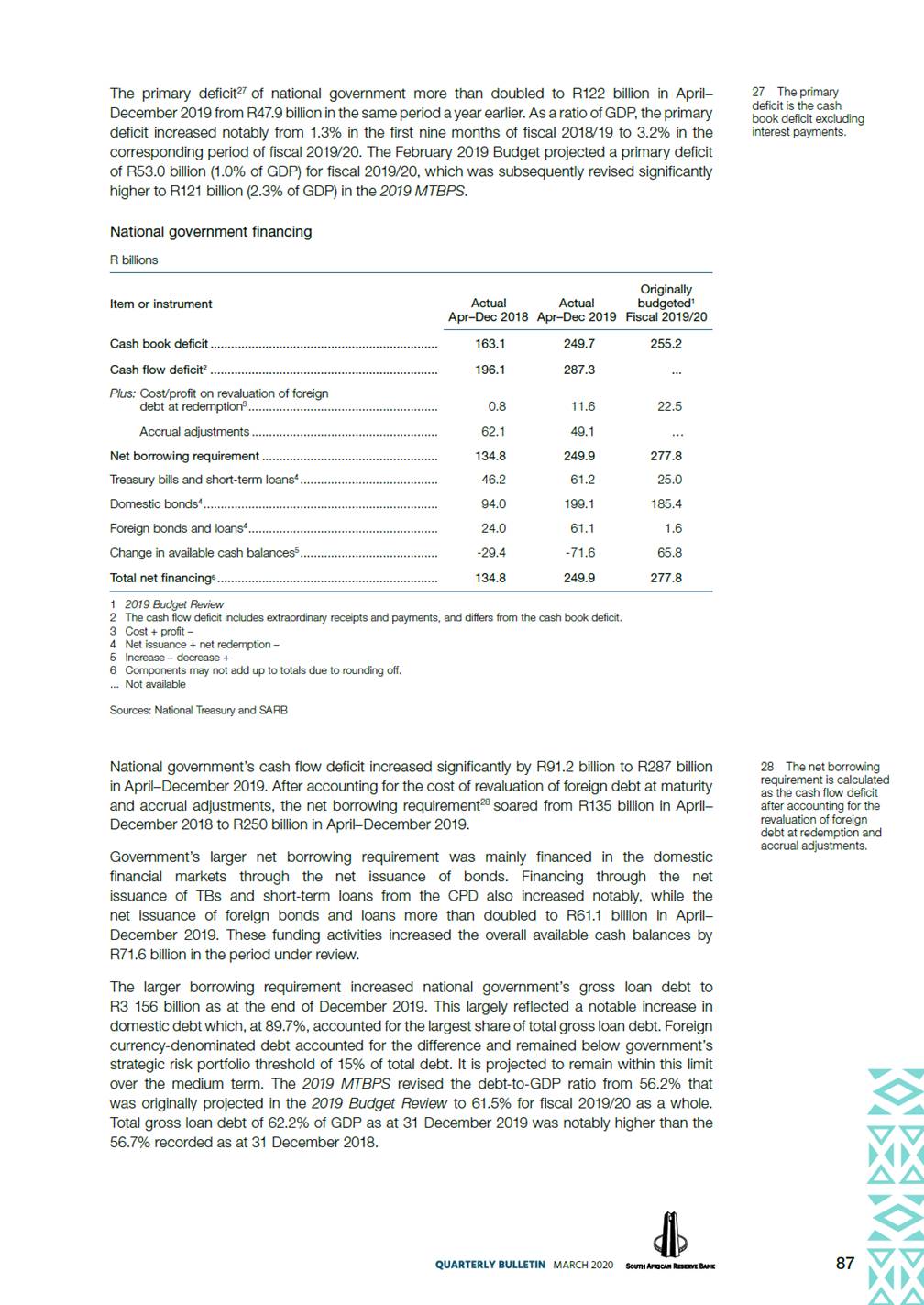

Quarterly Economic Review Introduction Global economic growth slowed further to 2.5% in the fourth quarter of 2019 as output growth decelerated sharply in the advanced economies and moderated in emerging markets. The annual expansion of 3.0% in the world economy in 2019 was the weakest since the 2007–08 global financial crisis. With the exception of the United States (US), growth in most advanced economies slowed significantly in the fourth quarter. Latin America and emerging Europe led the moderation in emerging markets, which was contrasted by a slight acceleration in China and India. World trade volumes contracted for the seventh consecutive month in December 2019, particularly in emerging markets, as trade tensions continued to weigh on sentiment. Global inflation remained muted throughout 2019. In the fourth quarter of 2019, a further decline in the international prices of metals and minerals contrasted a modest increase in that of agricultural products and energy. The price of Brent crude oil initially rose to a recent high of US$69 per barrel in early January 2020 amid optimism that a US–China trade deal would boost global economic growth prospects. In mid-February, however, oil prices decreased sharply due to concerns that the outbreak of the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) would weaken global demand. Oil prices declined further in early March as the virus spread to several countries. With Russia not cutting production in line with the Organization of the Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC), and Saudi Arabia then announcing an increase in production, oil prices fell significantly to around US$31 per barrel in mid-March. These developments contributed to a significant change in investors’ risk appetite, with global equity and bond prices falling sharply in the first two weeks of March. The South African economy entered a second technical recession since the first quarter of 2018, with real gross domestic product (GDP) contracting by a further 1.4% in the fourth quarter of 2019 following a revised contraction of 0.8% in the third quarter. The weakness in economic activity in the fourth quarter was broad-based, with output contracting in the primary, secondary and tertiary sectors. Annual output growth slowed further from 0.8% in 2018 to only 0.2% in 2019 – the lowest growth rate since the sharp contraction in 2009 following the global financial crisis. The faster pace of contraction in the real output of the agricultural sector was the main driver of the decrease in the real gross value added (GVA) by the primary sector in the fourth quarter of 2019 as mining output increased somewhat. On an annual basis, both agricultural and mining output contracted for a second successive year in 2019. Encouragingly, expectations of a much larger domestic maize crop could support agricultural output in 2020. The real GVA by the secondary sector decreased further in the fourth quarter of 2019 as output contracted in all the subsectors. The renewed implementation of load-shedding, and the intensity thereof, weighed on electricity production and also adversely affected manufacturing output in addition to continued weak demand. The real output of the construction sector, which decreased for a sixth successive quarter in the fourth quarter of 2019 and for a third consecutive year, reflected subdued fixed investment amid persistent low business confidence and sluggish economic activity. The real output of the tertiary sector reverted from an increase in the third quarter of 2019 to a decrease in the fourth quarter. Despite fairly strong Black Friday sales, which boosted retail trade in the fourth quarter, declines in wholesale and motor trade resulted in a contraction in the real GVA by the commerce sector. The output of the transport, storage and communication sector contracted notably further in the fourth quarter of 2019, consistent with the decline in import volumes. By contrast, growth in real economic activity in the finance, insurance, real estate and business services sector accelerated. Real gross domestic expenditure (GDE) decreased by a further 4.6% in the fourth quarter of 2019 following a similar decrease in the third quarter. Both real gross fixed capital formation and real final consumption expenditure by general government reverted from increases to contractions, alongside a much faster pace of real inventory de-accumulation. Real net exports contributed the most to growth in real GDP in the fourth quarter of 2019, but were offset by the run-down of inventories. Growth in real final consumption expenditure by households accelerated somewhat in the fourth quarter of 2019, supported by faster growth in real disposable income. Real spending on services, non-durable goods and, in particular, semi-durable goods increased at a faster pace, boosted by 1 MARCH 2020