Exhibit 99.E

DESCRIPTION OF THE REPUBLIC OF SOUTH AFRICA

DATED MARCH 1, 2022

INCORPORATION OF DOCUMENTS BY REFERENCE

This document is an exhibit to the Republic of South Africa’s Annual Report on Form 18-K under the Securities Exchange Act of 1934 for the fiscal year ended March 31, 2021. All amendments to such Annual Report on Form 18-K/A filed by South Africa following the date hereof shall be incorporated by reference into this document. Any statement contained in a document, all or a portion of which is incorporated or deemed to be incorporated by reference herein, shall be deemed to be modified or superseded for purposes of this document to the extent that a statement contained herein or in any other subsequently filed document that also is or is deemed to be incorporated by reference herein modifies or supersedes such statement. Any statement so modified or superseded shall not be deemed, except as so modified or superseded, to constitute a part of this document.

TABLE OF CONTENTS

In this document, the government of the Republic of South Africa is referred to as the “National Government,” “the Government” or the “South African Government”. The currency of the Republic of South Africa (South Africa) is the South African Rand. In this document, all amounts are expressed in South African Rand (R or Rand) or US Dollars (US$, $ or Dollars), except as otherwise specified. See “The External Sector of the Economy—Reserves and Exchange Rates” for the average rates for the Rand against the Dollar for each of the years 2018 through March 1, 2022. On February 28, 2022, the exchange rate, as reported by the South African Reserve Bank (SARB), was R15.4488 per Dollar (or 6.4730 US cents per Rand).

The Republic’s fiscal year begins on April 1 and ends on March 31. For example, the 2021 fiscal year refers to the fiscal year beginning April 1, 2020 and ending March 31, 2021. Economic data presented in this description is presented on a calendar year basis unless reference is made to the relevant fiscal year or the fiscal year is otherwise indicated by the context. For example, fiscal data referring to the “first quarter” of 2021 refers to data as at, or for the three months ended, June 30, 2021. Economic data referring to the “first quarter” of 2021, by contrast, refers to data as at, or for the three months ended, March 31, 2021.

Unless otherwise indicated, references to gross domestic product (GDP) are to real GDP, calculated using constant prices in order to adjust for inflation (with 2015 as a base year), and % changes in GDP refer to changes as compared to the previous year or the same quarter of the previous year, unless otherwise indicated. Some figures included in this document have been subject to rounding adjustments. As a result, sum totals of data presented in this document may not precisely equate to the arithmetic sum of the data being totaled. All GDP data presented in this document has been recalculated in line with Statistics South Africa’s (Stats SA) 2021 rebasing and benchmarking exercise. As such, recent GDP data and ratios that include GDP data are directly comparable across previous National Budgets and MTBPS figures found in this document. This is not the case when using the actual documents as printed at the time. For more information, see “—Effects of GDP rebasing on fiscal and debt ratios.”

Unless otherwise stated herein, references in this description to the 2021-2022 Budget are to the 2021-2022 National Budget as released on February 24, 2021 and not as amended by the Medium-Term Budget Policy Statement (MTBPS) released on November 11, 2021. References to the 2021-2022 Consolidated Government Budget, which includes the 2019-2022 National Budget as part thereof, shall be construed accordingly. Unless otherwise stated herein, references in this description to the 2022-2023 Budget are to the 2022-2023 National Budget as released on February 23, 2022 and described here under “Public Finance – 2022-2023 National Budget and Consolidated Government Budgets.”

A NOTE ON SEASONALLY ADJUSTED AND ANNUALIZED INFORMATION

Some of the figures included in this document have been subject to seasonal adjustment and/or annualization.

Seasonal adjustment is a method to account for and eliminate the estimated effects of normal seasonal variation from a series of data, so that the effects of other influences on the series can be more clearly recognized and defined. Depending on the nature of the seasonal pattern, seasonal adjustment is accomplished either by the multiplicative method (i.e., each value of a time series is adjusted by dividing by a seasonal index that represents the percentage of the normal value typically observed in that season) or the additive method (i.e., each value of a time series is adjusted by adding or subtracting a quantity that represents the absolute amount by which the value in that season of the year tends to be below or above normal, as estimated from past data).

The aim of annualization is to reflect what the real growth rate would be if the prevailing growth rate were to be sustained for a year. Annualized information is calculated as the quarterly data multiplied by four, while the annualized growth rates are derived by raising the change in a given quarter from the previous quarter to the power of four.

Summary Information

The following summary tables do not purport to be complete and are qualified in their entirety by the more detailed information appearing elsewhere in this document.

The following tables set forth certain summary statistics about the economy of South Africa, public finance and debt of the National Government for the periods indicated.

Selected Economic Indicators

| | As of and for the year ended December 31, | As of and for

the three-month

period ended

September 30,(1) |

| | 2016 | 2017 | 2018 | 2019 | 2020 | 2021 |

| | Rand (million) (except percentages) |

| The Economy | | | | | | |

| Gross Domestic Product (GDP) | | | | | | |

| Nominal GDP(2) | 4,759,555 | 5,078,190 | 5,357,640 | 5,605,034 | 5,521,075 | 6,124,329* |

| Real GDP(3) | 4,450,171 | 4,501,702 | 4,568,670 | 4,573,835 | 4,279,647 | 4,475,878* |

| Real % change from prior year | 0.7 | 1.2 | 1.5 | 0.1 | -6.4 | 5.8 |

| Unemployment rate (%) | 26.7% | 27.5% | 27.1% | 28.7% | 29.2% | 34.0% |

| | | | | | | |

| Balance of payments | | | | | | |

| Current account | (127,354) | (120,236) | (158,821) | (144,549) | 109,786 | 287,777** |

| Financial account | (32,942) | (71,453) | 18,176 | 28,584 | 83,608 | 32,545** |

| Change in gross gold and other foreign reserves | 47,356 | 50,722 | 51,641 | 55,058 | 55,013 | 57,058** |

| Rand/Dollar exchange rate (average) | 14.5 | 13.3 | 13.3 | 14.4 | 16.6 | 14.6 |

| Consumer prices (2016/12=100) | 80.5 | 84.3 | 88.1 | 91.6 | 94.4 | 98.7 |

| Producer prices (2020/12=100) | 84.8 | 89.2 | 93.8 | 97.1 | 100.0 | 106.8 |

* Estimate based on the three-month period ended September 30, 2021, seasonally adjusted and annualized.

** Cumulative numbers up to September 30, 2021, not seasonally adjusted.

| | As of and for the fiscal year ended March 31,(6) |

| | 2017 | 2018 | 2019 | 2020(4) | 2021(5) |

| | Rand (billion) (except percentages) |

| Main Government Revenue | 1,196.4 | 1,275.3 | 1,345.9 | 1,238.4 | 1,483.2 |

| % of GDP(2) | 25.5% | 23.5% | 23.7% | 22.2% | 24.0% |

| Main Government Expenditure | 1,404.9 | 1,506.6 | 1,691.0 | 1,789.0 | 1,893.1 |

| % of GDP(2) | 27.0% | 27.8% | 29.7% | 32.1% | 30.7% |

| Main Budget Deficit | (208.6) | (231.3) | (345.1) | (550.6) | (409.9) |

| % of GDP(2) | (4.4%) | (4.3%) | (6.1%) | (9.9%) | (6.6%) |

| Net borrowing requirement | 208.6 | 231.3 | 337.5 | 366.3 | 359. 3 |

| Change in cash and other balances | (29,041.3) | (24,590.2) | (3,701.2) | 17,737.9 | (284.7) |

_________________

Notes:

| (1) | For the three months ended September 30, 2021, seasonally adjusted and annualized. |

| (3) | At constant 2015 prices. |

| (4) | Final outcome for fiscal year 2020, as reflected in the MTBPS (November 2021). |

| (5) | Estimates as revised and reflected in the MTBPS (November 2021). |

| (6) | Fiscal ratios presented in table based on 2015 rebased GDP data. |

Source: National Treasury, SARB and Statistics SA (Stats SA).

The estimates included in this Annual Report are based on the 1993 System of National Accounts (SNA) published by the United Nations in cooperation with other international organizations. This means that the methodology, concepts and classifications are in accordance with the latest guidelines of an internationally agreed system of national accounts. The estimates of real GDP are expressed in terms of a 2015 base year. Revision of the estimates for all components of the national accounts is done from time to time based on the availability of data.

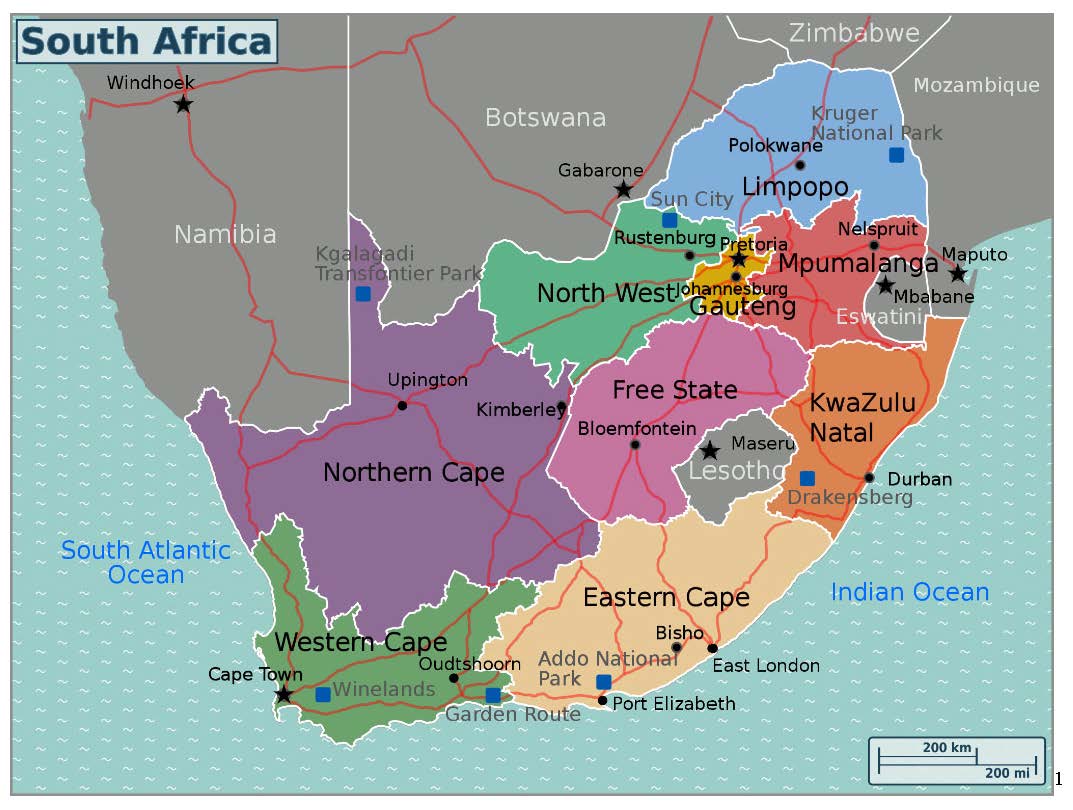

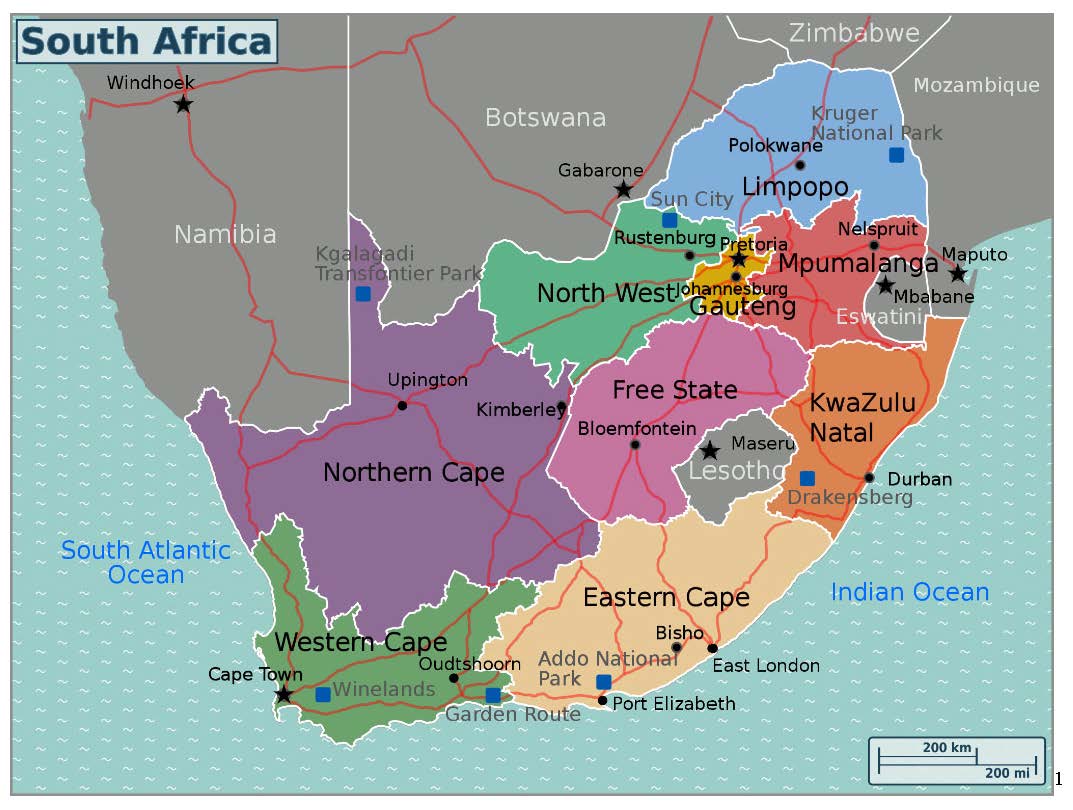

MAP OF THE REPUBLIC OF SOUTH AFRICA

Republic of South Africa

Area and Population

South Africa is situated on the southern tip of the African continent, with the Atlantic Ocean to the west and the Indian Ocean to the east. The north of the country shares common borders with Namibia, Botswana and Zimbabwe and, to the north east, the country shares a border with Mozambique. South Africa also shares common borders with the Kingdoms of Lesotho and Eswatini (formerly, Swaziland). The total surface area of South Africa is approximately 1,219,090 square kilometers, with over 3,000 kilometers of coastline.

South Africa comprises nine provinces, which are the Eastern Cape, Free State, Gauteng, KwaZulu-Natal, Limpopo, Mpumalanga, Northern Cape, North West and Western Cape Provinces.

According to the racial classifications that formed the basis for the apartheid system, “Black” referred to persons of original African indigenous origin, “Asian” to persons of Asian origin, “White” to persons of Caucasian ethnic origin and “Coloured” to persons of mixed race. While the National Government no longer makes any unfair discrimination based on race, the country’s history of racial division and racial and ethnic differences continues to have social and economic significance. This is because social and economic policies are judged partly by their ability to address disparities and discrimination and to equalize opportunities. Therefore, in this document, reference to such racially classified statistics is made occasionally to illustrate those disparities.

South Africa’s population is approximately 60.14 million as at June 30, 2021, of which approximately 30.8 million, representing 51.1% of the population, are female. Approximately 80.9% are Black, 8.8% are Coloured, 2.7% are Indian/Asian and 7.7% are White. The most densely populated parts of South Africa are the four major industrialized areas: the Pretoria/Witwatersrand/Vereeniging area of Gauteng (which includes Johannesburg), the Durban/Pinetown/Pietermaritzburg area of KwaZulu-Natal, the Cape Peninsula area of the Western Cape (which includes Cape Town) and the Gqeberha (formally Port Elizabeth), Kariega (formally Uitenhage) area of the Eastern Cape.

South Africa has a diverse population consisting of Afrikaans and English-speaking Whites, Asians (including Indians), Coloureds, Khoi, Nguni, San, Sotho-Tswana, Tsonga, Venda and persons that have immigrated to South Africa from across the globe. By virtue of the country’s diversity, South Africa has 11 official languages, namely Afrikaans, English, isiNdebele, isiXhosa, isiZulu, Sepedi, Sesotho, Setswana, siSwati, Tshivenda and Xitsonga. According to the results of the census conducted in 2011, isiZulu is the mother tongue of 22.6% of the population,

1 Mart Bouter, CC BY-SA 4.0 <https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0>, via Wikimedia Commons

followed by isiXhosa at 15.9%, Sepedi at 9.1%, Afrikaans at 7.9%, and English and Setswana at 8.2% each. IsiNdebele is the least spoken language in South Africa, at 1.5%.

Government and Political Parties

Following the repeal of apartheid legislation, South Africa held its first fully democratic national election on April 27, 1994.

On May 10, 1994, Mr. Nelson Mandela, who had previously been elected as president of the ANC, was inaugurated as South Africa’s first black president. Mr. Mandela served until his deputy, Mr. Thabo Mbeki succeeded him on June 16, 1999. Mr. Mbeki resigned from the presidency on September 24, 2008, and Mr. Kgalema Motlanthe served as interim President between September 25, 2008 and May 9, 2009.

On May 9, 2009, following the ANC’s victory in the elections, Mr. Jacob Zuma was inaugurated as the fourth democratically elected President of the Republic, and he appointed Mr. Cyril Ramaphosa as Deputy President.

In October 2017, the Supreme Court of Appeal ruled that former President Zuma had to face 18 counts of corruption, fraud, racketeering and money laundering. On February 14, 2018, former President Zuma resigned as President of the Republic of South Africa. On March 16, 2018, the National Prosecuting Authority announced the decision to prosecute former President Zuma on 16 charges of corruption, racketeering and money laundering. In November 2018, former President Zuma submitted a court application for a permanent stay of his prosecution. On October 11, 2019, the KwaZulu-Natal Division of the High Court, Pietermaritzburg, dismissed the application for permanent stay of prosecution. In December 2019, former President Zuma petitioned the Supreme Court of Appeal of South Africa to challenge the dismissal of his application for a permanent stay of prosecution. On March 13, 2020, the Supreme Court of Appeal of South Africa dismissed former President Zuma’s appeal application. In February 2020, an arrest warrant was issued for former President Zuma, which was subsequently cancelled by the KwaZulu-Natal Division of the High Court and in September 2020, former President Zuma brought an application for the recusal of Advocate Billy Downer, the prosecutor in the case against him for corruption, racketeering and money laundering. In October 2021 the KwaZulu-Natal Division of the High Court, Pietermaritzburg, dismissed the application for the recusal of Advocate Downer. Former President Zuma launched an appeal against the decision to dismiss his application for the recusal of Advocate Downer. On February 16, 2022, KwaZulu-Natal Division of the High Court, Pietermaritzburg dismissed the application and Former President Zuma’s trial is set to proceed on April 11, 2022.

Following former President Zuma’s resignation, Mr. Cyril Ramaphosa ran unopposed and was elected on February 15, 2018 as the President of South Africa by the National Assembly.

President Ramaphosa was inaugurated on May 25, 2019 for his first full-term as President of the Republic of South Africa following the ANC’s victory in the 2019 National and Provincial elections. President Ramaphosa appointed Mr. David Mabuza as the Deputy President and reduced his cabinet from 36 Ministers to 28 with the amalgamation of several portfolios.

Constitution

The Constitution of the Republic of South Africa, 1996 (Constitution) was adopted in 1996 and was phased in between 1997 and 1999. Since its adoption, there have been seventeen amendments to the Constitution. The Constitution provides for elections every five years as well as for the separation of powers among the legislative, executive and judicial branches of the National Government. Under the Constitution, the bicameral Parliament, in which the legislative authority of the National Government is vested, is comprised of a National Assembly and a National Council of Provinces (NCOP).

The National Assembly consists of no fewer than 350 and no more than 400 members elected on the basis of proportional representation pursuant to which political parties receive seats in proportion to the votes cast for the parties concerned.

The National Assembly is mandated by the Constitution to elect the President, provide a national forum for public consideration of issues, pass legislation, scrutinize and oversee executive action, maintain oversight of the bodies and institutions established by Chapter 9 of the Constitution, and ensure that Members of Cabinet are accountable collectively and individually to Parliament for the exercise of theirs powers and the performance of their functions.

The NCOP is one of the two Houses of Parliament and is constitutionally mandated to ensure that provincial interests are taken into account in the national sphere of government. This is done through participation in the national legislative process and by providing a national forum for consideration of issues affecting provinces. The NCOP also plays a unique role in the promotion of the principles of Cooperative Government and Intergovernmental Relations. It ensures that the three spheres of government work together in performing their unique functions in terms of the Constitution and that in doing so, they do not encroach in each other’s area of

competence. The NCOP consists of 90 members (namely 54 permanent members and 36 special delegates). Each of the nine provincial legislatures elects ten representatives.

Each province has its own executive authority, the premier. The premiers are elected by each Provincial legislature from among its members. The powers of the premier are exercised in consultation with a provincial executive council, which is constituted in a manner similar to the Cabinet in the National Government. The provinces exercise limited power on a national level, principally through their representatives in the NCOP, as well as through their power to block Parliamentary action affecting the constitutional position and status of the provinces. When deciding on bills that amend the constitution, the provincial delegations vote in accordance with the mandate conferred on them by their respective provincial legislature. Each province has one vote and at least six provinces have to vote in favor of the bill for it to be passed. Similarly, when deciding on bills that affect the provinces, the provincial delegations vote in accordance with the mandate conferred on them by their respective provincial legislatures. Each province has one vote and at least five provinces need to vote in favor of the bill for it to be approved.

Political Parties

The ANC is the ruling party in eight of the nine South African provinces. Founded in 1912, the ANC led the struggle against apartheid and is the most influential party in South Africa in terms of the size of its electoral constituency support. Following the May 2019 elections, the ANC occupies 230 of the National Assembly’s 400 seats. Every five years the ANC holds a National Conference where the ANC adopts proposed constitutional amendments and elects the National Executive Committee. The 54th ANC National Conference took place in Johannesburg, Gauteng Province, from December 16 to December 20, 2017, where Mr. Cyril Ramaphosa was elected president of the ANC.

2019 National and Provincial Elections

The official general election results were announced on May 11, 2019. The ruling ANC won the elections, receiving 57.50% of the votes cast in respect of the national elections. The DA remained the official opposition of the ANC, with 20.77% of the votes, and the EFF came in third with 10.80% of the votes.

The table below sets out the National and Provincial Assembly seats secured by political parties following the May 2019 general elections.

Political Party | Number of seats in

National Assembly |

| | | |

| ANC | 230 | 57.50% |

| DA | 84 | 20.77% |

| EFF | 44 | 10.80% |

| IFP | 14 | 3.38% |

| VF PLUS | 10 | 2.28% |

| ACDP | 4 | 0.84% |

| UDM | 2 | 0.45% |

| NFP | 2 | 0.35% |

| ATM | 2 | 0.44% |

| GOOD | 2 | 0.40% |

| AIC | 2 | 0.28% |

| COPE | 2 | 0.27% |

| PAC | 1 | 0.19% |

| ALJAMA | 1 | 0.18% |

| Other(1) | 0 | 1.87% |

| Total | 400 | 100.0% |

Note:

(1) Other includes the remaining political parties that did not obtain any of the 400 National Assembly seats, but obtained votes.

Source: IEC.

The table below sets out the NCOP seats secured by political parties following the May 2019 general elections.

Political Party | Permanent | Special |

| | | |

| ANC | 29 | 25 |

| DA | 13 | 7 |

| EFF | 9 | 2 |

| VP | 2 | 1 |

| IFP | 1 | 1 |

| Total | 54 | 36 |

Source: Parliament of the Republic of South Africa

2021 Municipal Elections

Municipal elections are held every five years. Municipal elections were held on November 1, 2021. The shares of the votes for the major parties were as follows: ANC — 47.9%, DA — 20.0%, EFF — 10.6%, IFP — 6.3%, and COPE — 0.2%. The next municipal elections are scheduled to take place in 2026.

Recent Political Developments

The Commission

In August 2018, the President established the Judicial Commission of Inquiry into State Capture, Corruption, Fraud and other allegations in the Public Sector (the Commission) to investigate allegations of state capture, corruption, fraud and other allegations in the public sector including organs of state in South Africa. The Commission was granted a final extension until September 30, 2021 to conclude its investigation.

On July 15, 2019, former President Zuma made his first appearance before the Commission and during the questioning he objected to further questioning. An agreement was reached with the Commission that he would continue to participate and would, therefore return on a later date. Former President Zuma attended the Commission’s proceedings on November 16 and 17, 2020. On November 16, 2020, an application was made by former President Zuma for the recusal of the Chairperson of the Commission and on November 19, 2020 the Chairperson dismissed the recusal application. Thereafter, the Commission was informed that former President Zuma had decided to excuse himself from the proceedings and it transpired that former President Zuma had left without the Chairperson’s permission.

In December 2020, the Commission made an application to the Constitutional Court wherein it sought to compel former President Zuma to appear before the Commission and to declare that his conduct of leaving the Commission without permission to be unlawful. On January 21, 2021, the Constitutional Court ordered former President Zuma to obey all summonses and directives lawfully issued by the Commission and directed him to appear and give evidence before the Commission on the dates determined by it. Former President Zuma did not attend the Commission as required and in February 2021, the Commission approached the Constitutional Court seeking an order declaring that former President Zuma is guilty of contempt of court and sentencing him to imprisonment for a period of two years. On June 21, 2021, the Constitutional Court declared that former President Zuma is guilty of the crime of contempt of court for failure to comply with the order made by the Constitutional Court and he was sentenced to 15 months’ imprisonment. On July 7, 2021, former President Zuma handed himself to the police. The incarceration of former President Zuma was followed by violent protest in parts of Gauteng and KwaZulu-Natal provinces which escalated into looting. On September 5, 2021 the Department of Correctional Services confirmed that former President Zuma was placed on medical parole.

The Commission concluded its investigations on January 1, 2022, and issued first and second parts of its three-part report on January 4, 2022 and February 1, 2022 (respectively) and intends to issue the third part of the report at the end of April 2022. The first and second parts of the Commission’s published report provide recommendations that deal with accountability of individuals and that call for institutional reforms, particularly in relation to public procurement policy, whistle-blowing laws and the governance of state-owned companies. Over the medium term, the government will devote considerable attention to strengthening its fight against corruption and addressing the recommendations of the report. In the 2022 Budget, the National Treasury details that it will engage with relevant departments and financial regulators on how to respond to the Commission’s findings on improving the regulation of cash transactions and public-sector procurement. The response will also address specific allegations of wrongdoing and how regulation laws can be strengthened to prevent future abuses.

Presidential Cabinet Changes

On August 5, 2021, President Ramaphosa reconfigured certain government departments and made changes to his cabinet. The changes to the departments and his cabinet were as follows:

| · | The Department of Human Settlements, Water and Sanitation was split into two departments being the Department of Human Settlements and Water and Sanitation. |

| · | The political responsibility of the State Security Agency was placed under the Presidency. |

| · | Mr. Mondli Gungubele was appointed to replace Mr. Jackson Mthembu as the Minister in the Presidency. |

| · | Ms. Khumbudzo Ntshaveni was moved as the Minister of Small Business Development and appointed as the Minister of Communications and Digital Technologies. |

| · | Ms. Thandi Modise was moved from her position as Speaker of Speaker of the National Assembly and appointed as the Minister of Defense and Military Veterans. |

| · | Mr. Enoch Godongwana, who was the Chairperson of the Development Bank of South Africa, was appointed as the Minister of Finance to replace Mr. Tito Mboweni following his resignation. |

| · | Dr. Joe Phaahla, who was the Deputy Minister of Health, and was appointed as the Minister of Health replacing Dr. Zweli Mkhize who tendered his resignation. |

| · | Ms. Mmamoloko Kubayi was moved as Minister of Tourism and appointed as Minister of Human Settlements. |

| · | Ms. Ayanda Dlodlo was moved as Minister of State Security and appointed as Minister of Public Service and Administration. |

| · | Ms. Stella Ndabeni-Abrahams was moved as Minister of Communications and Digital Technologies and appointed as the Minister of Small Business Development. |

| · | Ms. Lindiwe Sisulu was moved as the Minister of Human Settlements, Water & Sanitation and appointed as the Minister of Tourism. |

| · | Mr. Senzo Mchunu was moved as the Minister of Public Service and Administration and appointed as the Minister of Water and Sanitation. |

Legal System

The South African legal system is based on Roman-Dutch law and incorporates certain elements of English law, subject to the Bill of Rights contained in the Constitution. Judicial authority in South Africa is vested in the courts, which are established pursuant to the Constitution. The Constitution is the supreme law of the land and no other law can supersede the provisions of the Constitution. The Constitutional Court is the highest court in South Africa and has jurisdiction as the court of final instance over all matters relating to the interpretation, protection and enforcement of the terms of the Constitution. It is also the court of first instance on matters such as those concerning the constitutionality of an Act of Parliament referred to it by a member of the National Assembly. Decisions of the Constitutional Court are binding upon all persons and upon all legislative, executive and judicial organs of state. Matters not falling within the jurisdiction of the Constitutional Court fall within the jurisdiction of the other Superior Courts, which consists of the Supreme Court of Appeal and the High Court of South Africa (which has nine Divisions corresponding to the provinces). Judgments of the Supreme Court of Appeal are binding on all courts of a lower order, including the High Court of South Africa, and judgments of the High Court of South Africa are binding on the lower courts within their respective areas of jurisdiction.

The tenure of Chief Justice Mogoeng Mogoeng, who was appointed on September 8, 2011 came to an end in October 2021. Interviews for the vacant position of the Chief Justice were conducted by the Judicial Service Commission (JSC) from February 1, 2022 to February 4, 2022, following which the JSC recommended Justice Mandisa Maya, the current president of the Supreme Court of Appeal, for appointment as the Chief Justice in February 2022. The Chief Justice and the Deputy Chief Justice of the Constitutional Court are appointed by the President in consultation with the JSC and the leaders of parties represented in the National Assembly. The Judge President and Deputy President of the Supreme Court of Appeal are appointed by the President after consulting with the JSC only. The remaining judges of the Constitutional Court, the Supreme Court of Appeal and the High Court are appointed by the President on the advice of the JSC.

Key Reforms and Legislative Initiatives

Broad-Based Black Economic Empowerment

Broad-Based Black Economic Empowerment (B-BBEE) continues to be a core tenet of the government’s initiative to address the economic exclusion of historically disadvantaged South Africans as well as its socio-economic challenges. As part of this initiative, the National Government enacted the Broad-Based Black Economic Empowerment Act, 2003 (Act No. 53 of 2003) (B-BBEE Act), which came into effect in April 2004. For purposes of the B-BBEE Act, “black people” is a generic term which means Africans, Coloureds and Indians who are South African citizens. The B-BBEE Act aims to facilitate B-BBEE and promote economic transformation by: incentivizing meaningful participation by black people in the economy; changing the racial composition of ownership and management structures in enterprises; promoting investment programs that lead to B-BBEE; creating institutional mechanisms to support B-BBEE implementation; enabling access to economic activities, infrastructure and skills for black women and rural and local communities; increasing the extent to which workers, communities and cooperatives own and manage enterprises; and promoting access to finance for black economic empowerment (BEE). This B-BBEE Act is implemented, and its implementation is measured, through a balanced scorecard found in the B-BBEE Codes of Good Practice. The Act has since been amended by the Broad-Based Black Economic Empowerment Amendment Act 46, 2013 (Act No. 46 of 2013) to continue to give effect to government policy aimed at reducing inequality, defeating poverty and creating employment, and to address, inter alia, circumvention, regulatory mechanisms and compliance amongst other related matters.

The Department of Trade, Industry and Competition has issued the B-BBEE Codes of Good Practice on Black Economic Empowerment (the Codes). The Codes, which were promulgated in February 2007 and amended in October 2013, set out general principles for measuring ownership, management control, skills development, enterprise and supplier development and socio-economic development, including special guidance for exempted micro enterprises (small businesses), and qualifying small enterprises (medium size entities). The Codes also provide guidance on B-BBEE verification, the recognition of contributions toward B-BBEE of multinationals and the treatment of public entities and other enterprises wholly owned by organs of state.

The B-BBEE Act requires that every organ of national and local government and every public entity apply B-BBEE the relevant Codes in issuing licenses, implementing procurement policies, determining qualification criteria for the sale of state-owned enterprises and developing criteria for entering into public private partnerships. There is thus a positive binding onus placed on organs of states and public entities to promote inclusive growth through the B-BBEE Framework.

Multinational Companies

The Codes give multinational companies flexibility in the manner in which they implement the Codes. A multinational company can retain sole ownership of its South African subsidiary, provided that alternative measures to broaden economic participation by black people, in terms of the Codes, are exercised. One such alternative is through application of the Equity Equivalent Investment Programme which gives multinationals an opportunity to contribute towards skills transfer, empowerment of small-medium-micro-enterprises and broader socio-economic empowerment projects.

Public Entities and State Agencies

The B-BBEE Act places a legal obligation on state agencies to contribute to B-BBEE, including when developing and implementing their preferential procurement policies. The Preferential Procurement Policy Framework Act, 2000 (Act No. 5 of 2000) states that all spheres of government must have a mechanism in place that brings about categories of preference in allocation of contracts when procuring goods and services to advance historically disadvantaged individuals (HDIs). In evaluating submission for tenders above R50 million, a total of 10% is allocated to the B-BBEE Status Level. Dispensation was given to organs of state and public entities to apply pre-qualifying criteria to advance certain designated groups.

Private Sector

A business’ B-BBEE Status Level is an important factor affecting its ability to tender successfully for government and public entity tenders and to obtain licenses in certain sectors like mining and gaming, as well as trading with other firms in the private sector. The amendments, introduced by the Department of Trade, Industry and Competition (the DTIC) and approved by Parliament in 2013, impose penalties in certain circumstances such as fronting or circumvention of the legislation. These amendments became effective as of October 24, 2014. Private sector clients increasingly require their suppliers to have a minimum B-BBEE rating in order to boost their own B-BBEE ratings. B-BBEE is accordingly an important factor to be taken into account by any firm conducting business in South Africa.

The B-BBEE Act provides for the DTIC to publish and promote any transformation charter (for later development into industry codes) for a particular sector of the economy, provided that charter (or sector code) is developed by the major stakeholders in that sector and advances the objectives of the B-BBEE Act. These charters or sector codes set out a blueprint and timeline for the transformation of the relevant economic sectors, including such sectors as tourism, financial services, forestry and construction. To date the Minister has gazetted ten charters which are:

| · | Information and Communication Technology Sector Codes; |

| · | Construction Sector Code; |

| · | Integrated Transport (2009 Version) Sector Codes; |

| · | Financial Services Sector Codes; |

| · | Marketing, Advertising and Communication Sector Codes; and |

Sector Codes issued in terms of Section 9 of the B-BBEE Act have similar binding status as the Generic Codes.

Some of the biggest challenges facing the government in relation to the implementation of B-BBEE include educating the South African public on the objectives, opportunities and perceptions relating to B-BBEE, ensuring that the objectives of B-BBEE are properly adhered to, encouraging investment in South Africa that advances B-BBEE and promotes economic and social transformation and improving representation in senior and executive management positions.

The Companies Act, 2008 (Act No 71 of 2008) and its reforms

In 2011, the Companies Act, 2008 (Act No. 71 of 2008) (the Companies Act) came into effect, repealing the Companies Act, 1973 (Act No. 61 of 1973). The Companies Act introduced significant changes by providing for, among others, business rescue, simplification of registration, social and ethics committees for public companies, corporate governance including financial accountability, and provisions relating to shareholder activism. The Companies Act provides for the establishment of institutions, such as the Companies and Intellectual Property Commission, Companies Tribunal, Specialist Committee on Company Law, Financial Reporting Standards Council and Takeover Regulations Panel.

Companies Amendment Bill, 2021

The DTIC has, through the Companies Amendment Bill, 2021 (the 2021 Bill), undertaken a process to amend aspects of the Companies Act to improve provisions in the Companies Act dealing with three key policy objectives: reducing the administrative and financial burden of regulatory compliance, especially for small businesses; facilitating wage ratio transparency; and curbing ‘beneficial share ownership’ opportunities for money laundering. This follows a process that began in 2018 through the Companies Amendment Bill, 2018 (the 2018 Bill). The 2018 Bill was published on September 21, 2018 for public comment and it was followed by extensive public engagement with a number of interested persons and organizations. These included the National Economic Development and Labor Council (Nedlac), the Specialist Committee on Company Law (SCCL), the JSE Limited and the SA Institute of Chartered Accountants, among others. Following these consultations, the redrafted bill (in the form of the 2021 Bill) was published for public comment in October 2021.

The proposed amendments in the 2021 Bill cover the following:

| · | Change to the definition of securities; |

| · | Provision of the definition of true owner; |

| · | Provision for the preparation, presentation and voting on companies’ remuneration policy and director remuneration report; |

| · | Provision for the filing of annual financial statements, filing of the copy of the company securities register of disclosure of beneficial ownership with the Companies and Intellectual Property Commission; |

| · | Differentiation where the right to gain access to gain companies records may be limited; |

| · | Clarification when a notice of Amendment of the Memorandum of Incorporation (MoI) may take effect; |

| · | Empowering of the court to validate the irregular creation, allotment or issue of shares; |

| · | Clarification of aspects relation to partly paid shares; |

| · | Exclusion of subsidiary companies from certain requirements relating to inter-group finance; |

| · | Provision of instances where special resolution is required for the acquisition of shares of a company; |

| · | Extension of the definition of employee share scheme; |

| · | Provision for circumstances where private company will be a regulated company on effected transactions; |

| · | Provision for circumstances where company is unable identify persons who hold beneficial interests for securities. |

| · | Dealing with composition of the social and ethics committee (SEC), publication of the application for exemption from requirements to appoint the SEC; |

| · | Provision for presentation and approval of the SEC report at the annual general meetings of shareholders; and |

| · | Provision for differentiation of duties of Chairperson and Chief Operation Officer of the Companies Tribunal. |

Mining Industry Reform

Mining in South Africa has historically been undertaken largely by the private sector. As of December, 31 2021, there were approximately 1,968 operating mines and quarries in South Africa. The most important mining houses in South Africa include Anglo American plc, De Beers Corporation, African Minerals Limited, BHP Billiton SA, Gold Fields Limited, Impala Platinum Holdings Limited, Lonmin plc, Kumba Iron Ore Limited, Exxaro Limited, Xstrata plc and Harmony Gold Limited. These corporations, together with their affiliates, are responsible for the majority of the gold, diamond, uranium, zinc, lead, platinum, chrome, iron ore, coal and silver mining in South Africa.

The Minister of Mineral Resources is the competent authority for granting prospecting and mining licenses. The objective of the Department of Mineral Resources and Energy (DMRE) for fiscal year 2021 is to grant 120 licenses to HDIs, 125 licenses have been granted as of March 31, 2021. In comparison to the outcome achieved in 2020,which was 176 licenses issued, this has slightly dropped.

The South African Mineral Resources Administration System (SAMRAD) was launched in April 2011 to process mining license applications, which enables the monitoring of the status and improves overall quality of license applications. Through SAMRAD, the public can view the locality of applications, rights and permits made or held.

The DMRE is also responsible for managing environmental impacts from mining-related activities, and by the end of March 2021, had conducted 968 environmental verification inspections out of a target of 1,275 inspections. This has significant drop when compared with the actual achieved in 2020 for 1381, due to fewer official trips undertaken for mine inspections. The Department of Environmental Affairs has transferred some of the functions of the National Environmental Management Act, 1998 (Act No. 107 of 1998) (NEMA) related to mining activities to the DMRE, which means the DMRE would be the competent authority for environmental impact assessments for the mines and would also be responsible for developing tools and systems for mine environmental management and reporting.

Mining Charter

Subsequent to an extensive consultation with mining stakeholders the Mining Charter, 2018 was gazetted for implementation on September 27, 2018. This Charter represents the interest of all stakeholders and it is the DMRE’s view that it will meaningfully transform the industry while ensuring its growth and competitiveness. The Charter Regulations has been completed by the end of March 2019 financial year for ease and standardized implementation by all stakeholders. Regarding the developed Mining Charter, the court has set aside some of the provisions in the Charter (i.e. Ownership and Procurement). The Court further ordered that the Minister had no legal power to develop the Charter.

The DMRE, while proceeding with implementation of the Mining Charter in 2019/20, will undertake advocacy sessions and engagements with investors and stakeholders on the Charter and its Regulations. In this regard the DMRE has implemented youth upliftment programs for new entrants identified throughout the mining value chain, as well as assist with issues of access to funding, geological information, compliance and access to markets.

Mining and Petroleum Resources Development Act

The DMRE is in the process of amending part of the Mineral and Petroleum Resources and Development Act, 2002 (Act No. 28, 2002) (MPRDA) to excise the regulation of the petroleum and gas sector from the MPRDA, after the High Court in 2021 declared that certain aspects of the Mining Charter function as policy instruments without binding legislative effect.

The Upstream Petroleum Resources Development Bill, 2019 (Petroleum Bill), which seeks to ensure that the upstream petroleum sector is no longer regulated under the MPRDA and instead under discrete petroleum legislation, was gazetted for public comment in December 2019. The DMRE subsequently conducted public consultations with stakeholders who presented written submissions. The comments provided during the public consultation phase were taken into consideration in finalizing the Petroleum Bill, which was tabled in Parliament in July, 2021 as it was considered an ordinary bill affecting the provinces and consequently must be considered by both the National Assembly and the National Council of Provinces.

On March 27, 2020, the Minister of Mineral Resources and Energy published, for implementation, the Amendments to the Mineral and Petroleum Resources Development Regulations (Amended Regulations). The Amended Regulations provide for the following:

| · | improved regulation of Social and Labor Plans; |

| · | meaningful notification and consultation requirements; |

| · | procedures and requirements for downscaling and retrenchments, section 52 of the MPRDA; |

| · | procedures and requirements for surface land use, section 53 of the MPRDA; and |

| · | full alignment with NEMA and the One Environmental Management System and improved appeals regime. |

The following legislative instruments are still in progress and anticipated to be finalized during the 2021/22 financial year and these include the Mining Company of South Africa (MINCOSA) Bill, the Petroleum Agency of South Africa (PASA) Bill, the review of the Mine Health and Safety Act Amendment Bill and the related Regulations. The Department is progressing the Amendment of the Mine Health and Safety Act, 1996 (Act No. 29 of 1996) (MHSA) that seeks to address challenges relating to health and safety of mineworkers. This Bill will be published for stakeholder comments in the third quarter of the 2022/23 fiscal year.

With regards to shale gas, the DMRE will continue working together with its state-owned enterprises, the Council for Geoscience (CGS) and PASA, to evaluate shale gas and conduct new research initiatives, including an investigation into the occurrence of near-surface hydrocarbon.

Other Mining Industry Initiatives and Legislation

Health and safety standards within the industry are governed by the MHSA. The number of fatalities in the sector reported as of March 31, 2021 by the department indicate that they have not achieved the target set of 10% reduction in fatalities, and only achieved a 2% reduction in fatalities. There were more "multiple" fatalities reported by mines during the financial year. These fatalities are mainly caused by a lack of effective health and safety management systems at the mines. Fall of ground accidents remain the largest cause of fatalities, followed by transportation and machinery accidents. A 19% reduction in occupational injuries was achieved by the department, the reason for this over achievement is that less injuries were reported during lockdown levels 2 and 1. In September 2012, the Cabinet approved the moratorium on the acceptance and processing of applications to explore shale gas, allowing normal exploration (excluding the actual hydraulic fracturing) to proceed under the existing regulatory framework.

The CGS has undertaken a shale gas research project that is aimed at unlocking the unknowns and assumptions about shale gas exploration in the country. The project is also aimed at building scientific skills in the area of shale gas exploration as this is a new concept to the country at large.

The program is funded by the DMRE and will assist the government in making well-informed decisions about shale gas in South Africa.

The objectives of the program are to collect and review new geological information of the Karoo Basin, to define an environmental baseline, to assess the amount of recoverable gas mainly from the Whitehill and Prince Albert Formations, to cover various geo-environmental impacts like ground water dynamics with possible contamination and monitor potential seismic interferences.

The CGS Shale gas project will serve as a baseline study for future shale gas research work and play a vital role in review of Petroleum Exploration and Exploitation Regulations. NEMA regulations will be utilized as a framework in identifying shortfalls of the environmental impacts of the shale gas.

Department of Justice and Constitutional Development

The department continues to play a crucial role in the fight against fraud and corruption, particularly through its implementation of the National Anti-Corruption Strategy (NACS). Part of its responsibility in this regard is to ensure the effective and optimal functioning of Specialized Commercial Crime Courts (SCCCs). A total of six new

SCCCs were established in 2020/21 in the provinces of Limpopo (3), Mpumalanga (1), North West (1) and Northern Cape (1). Every province now has SCCCs. These courts enhance the department’s ability to combat serious commercial crime and corruption. Additional to the afore-mentioned, in 2020/21, the department prioritized the capacitation and operationalization of the Investigating Directorate, established in the Office of the National Director of Public Prosecutions in 2019 to deal specifically with offences or criminal or unlawful activities involving serious, high-profile and complex corruption, including allegations of corruption arising from Commissions of Inquiry. This prioritization will continue in 2021/22. Government will also give precedence to the appointment of members of a new National Anti-Corruption Advisory Council, a cross-sectoral body charged with overseeing the implementation of the NACS, and accountable to Parliament. See “Internal Security – Department of Justice and Constitutional Development” for additional information.

International Relations

South Africa maintains diplomatic relations with 123 countries. South African representation abroad includes 104 embassies, 16 consulates, 97, honorary consulates, 2 liaison offices, 68 non-resident accreditations and 12 representations in international organizations. South Africa hosts 123 embassies, 53 consulates, 79 honorary consulates, 1 liaison office, 18 non-resident accreditations and 35 international organizations.

United Nations

South Africa is one of the 51 founding members of the United Nations (UN) in 1945. South Africa has served as a member of the UN Security Council, the UN Human Rights Council and is a member of the UN General Assembly and the Economic and Social Council of the United Nations.

African Union (AU)

The Organization of African Unity (OAU) was established on May 25, 1963 in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia with the signing of the OAU Charter by representatives of 32 governments. South Africa joined the AOU in 1994, becoming the 53rd member of the continental body. In July 2000, the AOU was revitalized and the Constitutive Act of the African Union (the Act) opened for signatures, South Africa’s Parliament ratified the Act in February 2001 and ascended to membership of the AU and some of the AU bodies as articulated in the Act. South Africa has served as the chair of the AU Commission and as chair of the Union.

International Monetary Fund (IMF)

South Africa is a founding member of the IMF and is one of 40 participants that have ratified the IMF’s expanded and amended New Arrangements to Borrow (NAB). South Africa committed a maximum of 340 million Special Drawing Rights (SDRs) to NAB during the five-year period from 2012 to 2017 and was called upon to lend a total of 90.2 million SDRs (R1.4 billion). South Africa has renewed its membership as a participant in the NAB for the five-year period from 2017 to 2022 and has renewed its commitment of 340 million SDRs. As of September 24, 2021, South Africa’s quota at the IMF was 0.68 billion SDRs.

South Africa is one of the 35 participants with commitments to the IMF’s 2012 Bilateral Borrowing Agreements (BBAs). South Africa committed US$2 billion to the 2012 BBAs. In October 2017, South Africa migrated to the IMF’s 2016 BBAs, to which it again committed US$2 billion (2.8 billion SDRs).

South Africa also contributes funds to the Poverty Reduction and Growth Trust (PGRT), the IMF’s instrument for financial support to low-income countries (LICs).

World Bank

South Africa is a founding member of the World Bank Group, which comprises the International Bank for Reconstruction and Development (IBRD), the International Development Association (IDA), the International Finance Corporation (IFC) and the Multilateral Investment Guarantee Agency (MIGA).

General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade

South Africa is a founding member of the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (GATT), participated in the Uruguay Round of Multilateral Trade Negotiations and acceded to the Marrakesh Agreement that established the World Trade Organization (WTO) in 1994. It is also part of the generalized system of preferences of Canada, the European Union (EU), Japan, Norway, Russia, Switzerland, Turkey and the United States.

South Africa is party to the Economic Partnership Agreement with the European Union, the Southern Africa Customs Union, the Southern African Development Community, the African Continental Free Trade Area, the

Trade, Development and Cooperation Agreement; the EFTA-SACU Free Trade Agreement, the Southern Common Market (Mercosur) PTA and the Trade and Investment Framework Agreement.

Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development

South Africa enjoys a strong partnership with the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) and participates in numerous programs and committees. South Africa is a signatory to the Convention on Combating Bribery of Foreign Public Officials in International Business Transactions, and part of the Mutual Acceptance of Data system and has played a key role in the establishment of the African Tax Administrators Forum.

Group of 20 (G20)

South Africa is a member of the Group of 20 and is also a member of the Financial Stability Board (FSB), a structure responsible for setting standards and monitoring the progress of financial regulation globally.

BRICS

South Africa became a member of BRICS in 2010 and has participated in all subsequent Leaders Summits. BRICS is a group composed of five major emerging market economies; namely, Brazil, Russia, India, China and South Africa.

New Development Bank

During the sixth BRICS Summit, which took place in Fortaleza on July 15, 2014, leaders of the BRICS countries signed the Agreement Establishing the New Development Bank (NDB), thus making South Africa a founding member of the bank, with equal shareholding among all founding members.

Commonwealth

In 1994, South Africa re-joined the Commonwealth. South Africa’s participation is limited to promoting economic, social and cultural cooperation and enhancing democracy through the Commonwealth Heads of States and Ministers’ meetings.

African Continental Free Trade Agreement (AfCFTA)

South Africa is a signatory to and a member of the AfCFTA, which came into force on May 30, 2019. The AfCFTA aims to promote the economic integration of Africa’s small and fragmented markets to create a single continental market for goods and services with the free movement of people and capital. The AfCFTA will bring together 55 members of the African Union, representing a population of more than 1.2 billion people and a combined gross domestic product of over US$3.4 trillion.

African Development Bank

South Africa is a member of the African Development Bank Group, which comprises the African Development Bank (AfDB), the African Development Fund (ADF) and the Nigeria Trust Fund (NTF). The AfDB was founded following an agreement signed by member states on August 14, 1963, in Khartoum, Sudan, and became effective on September 10, 1964. South Africa joined the AfDB in 1995 and has been contributing to the ADF since 1996. South Africa is the fourth largest shareholder of the AfDB and actively makes contributions to the ADF.

Public Health

South Africa has a well-established health sector which comprised approximately 11% of GDP (including private sector expenditure) in the 2020/21. This percentage was higher than in most years, as a result of the temporary budget additions to the sector to fight the COVID-19 pandemic and the GDP contraction in this year. There are over 4,000 public health facilities, including approximately 400 hospitals throughout the Republic. Public health spending was approximately R262.7 billion in the 2020/21 fiscal year (including the school nutrition program and training of medical professionals), slightly less than private health spending which was approximately R266.2 billion.

Over the past decade several achievements have been realized in the health sector, including among others, improved life expectancy and reduction in child and maternal mortality. Life expectancy has increased from an estimated 55.4 years to 64.7 years between 2009 and 2019, but declined slightly to 62 years in 2021 due to the COVID-19 pandemic. The under-five mortality rate declined from 79 to 30.8 per 1000 live births between 2002 and 2021 and the infant mortality rate has declined from 55.9 to 24.1 over the same period. Contributing to this is

increased access to anti-retroviral treatment through universal test and treat, new child vaccines (rotavirus and pneumococcal) and an effective prevention of mother-to-child HIV transmission which had been reduced to below 1%.

COVID-19 Impact and Response

In December 2019, the emergence of a new strain of the COVID-19 was reported in Wuhan, Hubei Province, China that has subsequently spread throughout the world, including South Africa. On January 30, 2020, the World Health Organization declared COVID-19 a public health emergency of international concern and on March 11, 2020, the World Health Organization declared COVID-19 a global pandemic. The COVID-19 outbreak is currently having a significant short-term adverse impact on the global economy, including sharp reductions in GDP and financial markets, but the medium and longer-term implications are difficult to predict. In South Africa, the COVID-19 outbreak has had an adverse impact across various sectors of the economy including the financial markets, which have experienced significant sell-offs in equities, bonds and exchange rates following developments related to the outbreak and recent ratings actions. See “ – Recent Ratings Developments” below.

To prevent the spread of COVID-19, on March 15, 2020, South Africa imposed travel restrictions, closed educational institutions and prohibited gatherings of more than 100 persons, among other restrictions. On March 23, 2020, President Cyril Ramaphosa announced a nation-wide 21-day lockdown, which commenced on March 27, 2020, as well as more comprehensive travel restrictions and mandatory self-quarantining measures. Essential services such as health services, grocery stores, pharmacies, laboratories, emergency personnel and security services are exempt from the lockdown and continue to operate. From April 29, 2020, South Africa gradually started easing the restrictions and has since then alternated between different levels of lockdown restrictions (on a 1-5 scale where level 5 is the most severe and level 1 is the least severe restriction). As at February 3, 2022, the country was on adjusted level 1, with most of the restrictions removed.

The Government has implemented a number of interventions to support South Africa's economy and mitigate the economic impact of COVID-19. These measures include support for businesses through an expansion of the Employment Tax Incentive, an extension for certain businesses' pay-as-you-earn tax payments and the allocation of additional funding for certain SMEs and firms producing essential goods, as well as support for workers and individuals through the creation of a special COVID-19 Temporary Employer/Employee Relief Scheme. In addition, on March 19, 2020, the SARB announced a reduction in the repo rate of 100 basis points, from a level of 6.25% to 5.25%. The SARB has also announced a set of interventions to stabilize financial markets and ensure sufficient liquidity in money markets, including additional liquidity provision both overnight and on a term basis to clearing banks, an increase in the penalty for placing funds back with the SARB at end of day square-off, and the purchases of government bonds in the secondary market. In addition, the Prudential Authority has announced certain regulatory measures to provide temporary liquidity relief to banks, controlling companies of such banks and branches of foreign institutions.

As at February 2022, South Africa has experienced four significant waves of COVID-19 infections, with 3.6 million confirmed cases, 95,000 confirmed deaths and close to 300,000 excess deaths between May 3, 2020 and January 22, 2022 as estimated by the South African Medical Research Council.

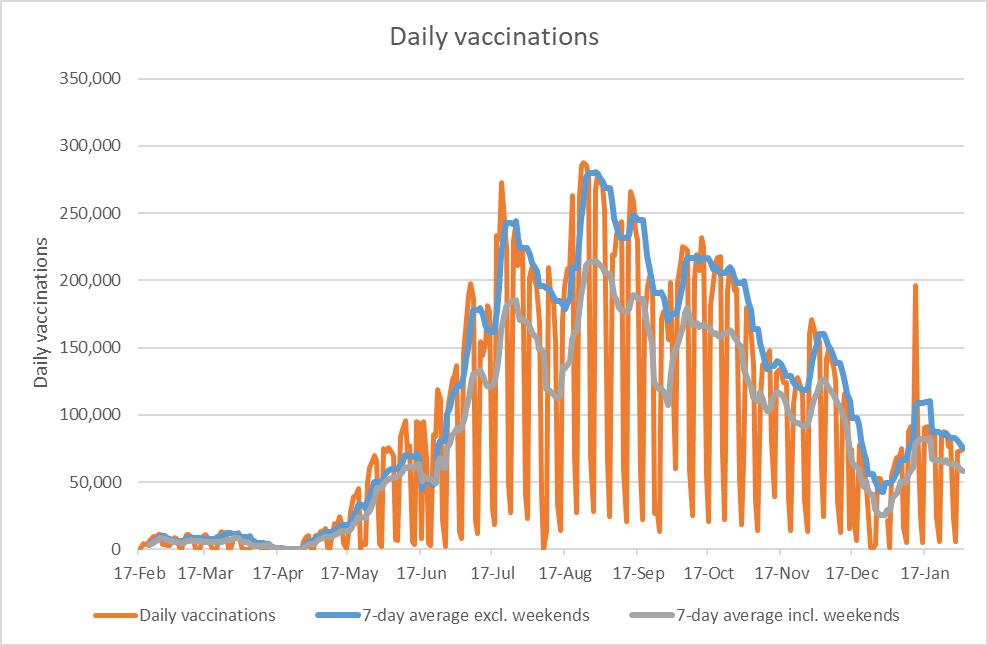

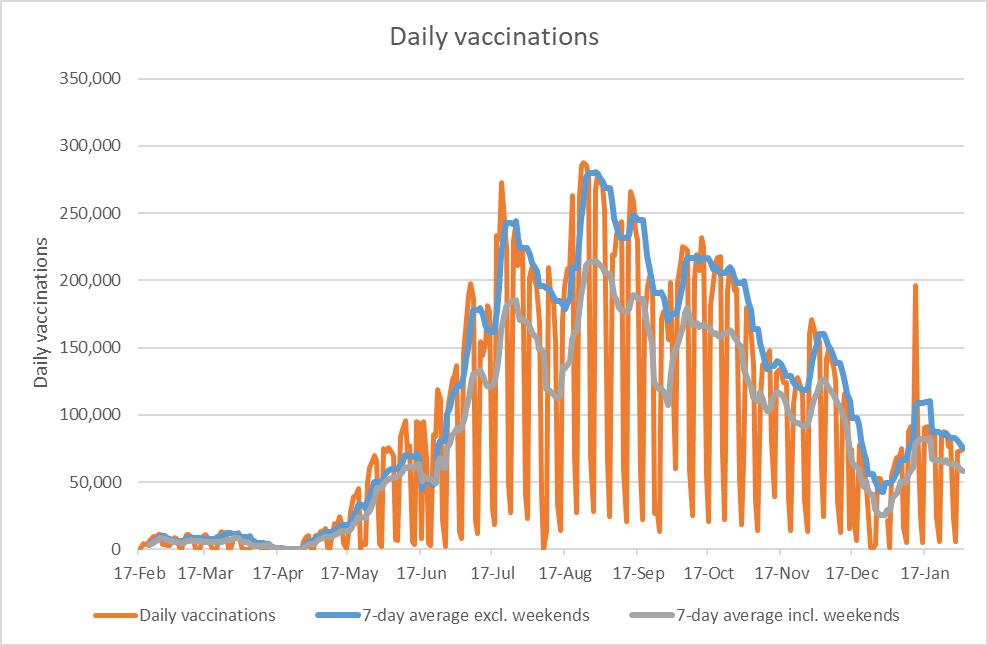

The public vaccination program is facilitating a reopening of the economy. As at February 2, 2022, 18.6 million adults (46.7% of the adult population) had received at least one dose and 16.5 million (41.5% of the adult population) were fully vaccinated. Coverage is higher in the elderly (60+years) segments of the population and lower amongst young people. In total, over 30 million doses have been administered and the daily vaccinations was approximately 75,000 doses per day on average (excluding weekends) since their roll-out in May 2021.

Figure 1 – COVID-19 Vaccination Progress in South Africa since Program Inception in 2021 through January 2022

HIV, AIDS and TB

Stats SA estimates the average life expectancy in South Africa for females to be 64.6 years, and 59.3 years for males. However, it should be noted that life expectation estimates vary, primarily due to differences in assumptions about the rapidity with which the HIV epidemic will spread and the morbidity and mortality of the disease.

| · | The socio-economic impact of the HIV and AIDS epidemic on South Africa is significant and the National Government has made the curtailment and treatment of this disease a high priority. This, along with the treatment and prevention of TB, is part of a multi-pronged strategy to improve public health services that also includes hospital revitalization, increasing the number of health professionals in the public sector, the introduction of new generation child vaccines, and improved infectious and non-communicable disease control programs. |

| · | A multi-sectoral approach aims to improve prevention programs and mitigate the impact of AIDS-related morbidity and mortality. The National Strategic Plan for HIV, TB and STIs 2017-2022 (launched on March 31, 2017, by then Deputy President Cyril Ramaphosa) aims to build on achievements made in HIV, TB and STI prevention, treatment and care and address social and structural barriers that increase vulnerability to HIV, TB and STI infection and increase protection of human rights. Some of the key objectives of this plan include: |

| o | reducing new HIV infections from 270,000 to less than 100,000 per year; |

| o | reducing new TB infections from 450,000 to less than 315,000 per year; and |

| o | reaching the 90–90–90 targets by 2020, whereby 90% of people living with HIV know their HIV status (an estimated 93% was achieved in March 2021), 90% of people who know their HIV positive status are accessing treatment (71% achieved in March 2021) and 90% of people on treatment have suppressed viral loads (88% achieved in March 2021). |

Spending on HIV and AIDS has grown rapidly to approximately R48 billion per annum (including foreign donor contributions) in 2020/21, of which R24 billion came from the HIV and AIDS conditional grant to provincial departments of health. There is evidence that access to ART treatment has extended the lifespan of many South Africans. According to StatSA’s 2021 mid-year population estimates, the number of people living with HIV has increased over the past decade from 5.2 million in 2009 to 8.2 million in 2021, while the number of HIV related deaths has been on a constant decline from 202,218 to 85,154 over the same period.

Quality of care

Although health outcomes in the country are improving, the public health sector nevertheless faces many challenges and the quality of care provided in public health facilities is often regarded as inadequate. Increased focus has been placed on improving the quality of the public health sector through the establishment of Office of Health Standards and Compliance (OHSC). OHSC is mandated to monitor and enforce compliance with health establishments with norms and standards prescribed by the Minister of Health. The Office is also mandated to

consider and investigate complaints relating to the quality of the public sector. Initiatives such as the Ideal Clinic program and the recently announced National Quality Health Improvement Plan aim to raise the standard of primary healthcare facilities and hospitals in the country, and address gaps identified by OHSC.

National Health Insurance (NHI)

NHI is the South African government’s chosen path towards achieving universal health coverage, equitable access and improved quality of health care for all. Substantial changes are envisaged in both the public and private health sectors, particularly in terms of the way these are financed. Key to this reform is establishing an NHI Fund, which will pool funding for healthcare and purchase services from both public and private providers on behalf of the entire population. In 2019, the NHI Bill was introduced to Parliament, and still remains with Parliament, to establish the legal foundation of the NHI Fund. Parliament’s Portfolio Committee on Health has received a significant amount of comments as part of its public consultation and is also conducting hearings in all nine provinces. Reforms can be expected in the enactment of the NHI.

Due to the COVID-19 pandemic and related government response efforts, spending on NHI grants has been low as funds have been appropriated towards other grants such as for the employment of medical interns. In 2022/23, the Department of Health will focus on piloting strategic purchasing at the sub-district level through contracting units for primary care.

Internal Security

South African Police Service (SAPS)

Amid capacity and budget challenges, the South African Police Service (SAPS) continues to prioritize improving community safety and combatting contact crimes such as crimes against women and children using its workforce of more than 175,000 officials. This includes frontline police officers such as constables, emergency response teams such as public order policing units, detectives, forensic analysts, K-9 Units and scientists, among others. These officials work to prevent, investigate and solve the most complicated and sophisticated criminal cases.

The department is strengthening its efforts to fight serious and priority crime such as corruption. To this end, the Directorate for Priority Crime Investigation (DPCI) within SAPS was allocated additional funding over the 2020 Medium Term Expenditure Framework (MTEF) period to improve its investigative capacity. Accordingly, as at the end of 2020/21, the DPCI had a total staff complement of 2,514 personnel. This number is expected to increase to over 3,000 over the medium term as the Directorate appoints more investigators. In 2020/21, the percentage of trial ready case dockets for serious corruption in the public and private sectors was 72.34% (68 from a total of 94) and 78.48% (124 from a total of 158), respectively. Over the same period, 103 out of 120 or 85.83% of cyber-related crime investigative support case files were investigated, of which 65% (or 67 from a total of 103) were successfully investigated by the DPCI within 90 calendar days.

Given the context of increased violent crimes such as gender-based violence and femicide in South Africa, the SAPS is implementing initiatives to enhance its forensic services capacity. The implementation of the Criminal Law (Forensic Procedures) Amendment Bill, 2021 is critical in this regard. The Bill is being introduced as an amendment to the Criminal Law (Forensic Procedures) Amendment Act, 2013 (Act No. 37 of 2013). This Act provides for the taking of buccal samples from all persons who have been convicted of a sentence of imprisonment in respect of any offence listed in Schedule 8 of the Criminal Procedure Act, 1977 (Act No. 51 of 1977), within a period of two years from the date of commencement of the Act. Following the enactment of the Act, challenges were encountered with regard to the taking of buccal samples from convicted Schedule 8 offenders, with some offenders refusing to submit to the taking of their buccal samples or to take it themselves on the account that this is an infringement of their human rights. This situation was worsened by the fact that the Act does not provide for a mechanism to enforce compliance with the requirement to submit to the taking of a buccal sample by convicted Schedule 8 offenders. Over the medium term, the department will implement the Criminal Law (Forensic Procedures) Amendment Bill, 2021 (once enacted into law) to ensure that Schedule 8 offenders are not being released without being sampled as this has far reaching consequences such as failure to link offenders to unsolved crimes or to crimes which they might commit in future.

The department is also prioritizing the thorough and responsive investigation of crime to foster a feeling of safety in communities. This is further accompanied by intensified efforts to increase police visibility in communities. During the 2020/21 financial year, the department initiated a pilot of its Safer Cities Framework in 10 cities. The Framework entails a multidisciplinary approach towards fighting crime and includes collaboration between SAPS and its key stakeholders to ensure that cities are safer and more secure. Over the same period, the percentage reduction in outstanding case dockets related to contact crimes older than 3 years amounted to 46.2% against an annual target of 14.7%. The improved performance in this regard was due to enhanced efforts by the department

to utilize its ICT systems such as the Persons Identification and Verification Application (PIVA) System to better profile suspects. The department also enhanced the implementation of its monitoring systems at divisional level to achieve reduced levels of contact crime. Moreover, to improve police visibility in communities, the Community-in-Blue protocol was developed for implementation in all nine provinces and over eight thousand patrollers were recruited, nationally. The goal is to intensify efforts to improve community policing, focusing on the mobilization of the Community-in-Blue initiatives, in order to improve visibility, particularly in high crime areas.

Department of Justice and Constitutional Development

The Department of Justice and Constitutional Development continues to play a crucial role in the fight against fraud and corruption, particularly through its implementation of the National Anti-Corruption Strategy (NACS). Part of its responsibility in this regard is to ensure the effective and optimal functioning of Specialized Commercial Crime Courts (SCCCs). A total of six new SCCCs were established in 2020/21 in the provinces of Limpopo (3), Mpumalanga (1), North West (1) and Northern Cape (1). Every province now has SCCCs. These courts enhance the department’s ability to combat serious commercial crime and corruption. Additional to the afore-mentioned, in 2020/21, the department prioritized the capacitation and operationalization of the Investigating Directorate, established in the Office of the National Director of Public Prosecutions in 2019 to deal specifically with offences or criminal or unlawful activities involving serious, high profile and complex corruption, including allegations of corruption arising from the Commissions of Inquiry. This prioritization will continue throughout the 2021/22 fiscal year. Government will also give precedence to the appointment of members of a new National Anti-Corruption Advisory Council, a cross-sectoral body charged with overseeing the implementation of the NACS, and accountable to Parliament.

In March 2020, Cabinet approved the National Strategic Plan (NSP) on gender-based violence and femicide (GBVF) which sets out roles, responsibilities and actions for government and civil society to speedily address this scourge. Pillar 3 of the NSP inter alia requires the department (Justice and Constitutional Development), South African Police Service, and the NPA to reduce backlog cases related to GBVF, which includes cases of domestic violence. Three Bills, namely, the Criminal Law (Sexual Offences and Related Matters) Amendment Act Amendment Bill, 2020, the Criminal and Related Matters Amendment Bill, 2020, and the Domestic Violence Amendment Bill, 2020 were introduced in Parliament in 2020/21 to deal with issues relating to GBVF. With regards to convictions, in the year ended March 31, 2021, the NPA achieved a conviction rate of 75.8% (against a target of 70%) in sexual offence cases, up from 75.2% in the year ended March 31, 2020.

Priority was also given in 2020/21 to creating capacity in the Information Regulator, responsible for the promotion and protection of the right to privacy as it relates to personal information and the right of access to information, as enshrined in the Protection of Personal Information Act (2013) and Promotion of Access to Information Act (2000). The additional capacity will enable the Information Regulator to effectively discharge its legislative mandate, i.e. the regulation of access to information and protection against unauthorized dissemination of personal information.

The South African Economy

Overview

South Africa has the second largest economy in Sub-Saharan Africa in terms of total GDP, accounting for approximately 20% of the aggregate GDP of Sub-Saharan Africa as of 2020 according to World Bank Data. However, South Africa continues to confront a challenging domestic and international economic environment. Following the financial crisis, which induced a 1.5% contraction in real GDP growth in 2009, real GDP growth rebounded to rates above 3% in 2010 and 2011. Growth subsequently declined to 1.4% in 2014, 1.3% in 2015, 0.7% in 2016 and 1.2% in 2017 as a result of lower commodity prices, higher borrowing costs, diminished business and consumer confidence, and drought. The economy fell into technical recession in the first half of 2018, as a result of production losses in the agriculture and mining sectors, while investment growth remained subdued and imports accelerated. Growth rebounded in the second half of 2018, primarily driven by a recovery in the manufacturing, transport, finance and business services sectors, which resulted in real GDP growth of 1.5% in 2018. In 2019, real GDP growth slowed to 0.1%, partly as a result of electricity supply failures. The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic and its mitigating measures induced a notable 6.4% contraction in real GDP in 2020. Weak growth has contributed to a record unemployment rate of 34.9% as of the third quarter of 2021. Economic growth projections in the 2022 Budget estimate a solid rebound in growth to 4.8% in 2021, before settling at 1.7% by 2024. Electricity shortages are expected to constrain the economy over the medium term.

In spite of the economic downturn in recent years, South Africa has maintained a stable and transparent macroeconomic framework, a well-developed financial sector, and resilient institutions, all of which have underpinned long-term economic stability.

South Africa has a robust regulatory environment, openness to trade, a floating exchange rate, a credible inflation-targeting regime and sound institutions, strong investor protection and an independent judiciary, which maintains the rule of law.

South Africa is resource rich. It is the world’s largest producer of platinum and chromium and holds the world’s largest known reserves of manganese, platinum group metals, chromium, vanadium and alumino-silicates. The economy includes a sophisticated finance, wholesale and retail trade, logistics, catering and accommodation sectors, as well as a developed manufacturing sector. Financial markets are liquid and both equities and government bonds are actively traded by domestic and international investors.

The World Economic Forum Global Competitiveness Report ranks South Africa as the second most competitive country in sub-Saharan Africa. Having lost competitiveness in 2018 due to changes in the political landscape, South Africa gained momentum in 2019, improving to 60th out of 140 countries, up from 67th in 2018. South Africa continues to rank favorably for financial market development, large market size and good infrastructure, with one of the most advanced transport infrastructure in the region. South Africa has a sophisticated banking sector with a major footprint in Africa. It is the continent’s financial hub, with the Johannesburg Stock Exchange (JSE) as Africa’s largest stock exchange by market capitalization.

With the most developed industrial and financial capabilities on the African continent, South Africa plays an important role in regional policies, markets, finance and infrastructure, and has an attractive position as the gateway into Africa. Outwardly oriented South African companies are among the largest sources of foreign direct investment (FDI) in Africa and the country’s development finance institutions are playing an increasing role in the funding of regional infrastructure investments. According to the United Nations Conference on Trade and Development’s (UNCTAD) World Investment Report, outward FDI by South African firms had increased by 64% to US$7.5 billion in 2017 as retailers expanded to Namibia and one of South Africa’s largest banks opened additional branches across the continent. However, the COVID-19 pandemic triggered health and economic challenges which have affected FDI inflows globally. FDI inflows to South Africa decreased by 39% to US$3.1 billion in 2020 and outwards investments from South Africa were negative (-US$2.0 billion) as South African multinational enterprises repatriated capital from foreign countries.

South Africa has been strongly adversely affected by the effects of the COVID-19 outbreak. While the sharp contraction in GDP is not forecast to persist, any subsequent declines in global GDP growth or prolonged disruption of financial markets may impede a growth recovery in South Africa, particularly if South Africa suffers repeated large outbreaks or is required to re-impose substantial restrictions.

Income Inequality; Labor and Employment

On March 11, 2020, the World Health Organization declared the COVID-19 outbreak a pandemic. Due to the infectiousness and severity of the disease, the government responded with a number of measures aimed at controlling the pandemic, the main being a nationwide lockdown. This resulted in income loss for individuals and