Exhibit C

FORDING CANADIAN COAL TRUST

MANAGEMENT’S DISCUSSION AND ANALYSIS

FORWARD-LOOKING INFORMATION

This management’s discussion and analysis contains forward-looking information within the meaning of the United States Private Securities Litigation Reform Act of 1995 including, but not limited to, Fording Canadian Coal Trust’s expectations, intentions, plans and beliefs. Forward-looking information can often be identified by forward-looking words such as “anticipate”, “believe”, “expect”, “goal”, “plan”, “intend”, “estimate”, “optimize”, “may”, and “will” or similar words suggesting future outcomes, or other expectations, beliefs, plans, objectives, assumptions, intentions or statements about future events or performance. This management’s discussion and analysis contains forward-looking information, included in, but not limited to, the sections titled Overview, Strategy and Key Performance Indicators, Nature of Operations, 2007 Compared with 2006, Outlook, Liquidity and Capital Resources, Outstanding Unit Data, Critical Accounting Estimates, Changes in Accounting Policies, Financial and Other Instruments, Key Risks and Uncertainties.

Unitholders and prospective investors are cautioned not to place undue reliance on forward-looking information. By its nature, forward-looking information involves numerous assumptions, known and unknown risks and uncertainties, of both a general and specific nature, that could cause actual results to differ materially from those suggested by the forward-looking information or contribute to the possibility that predictions, forecasts or projections will prove to be materially inaccurate. For a further discussion of the assumptions, risks and uncertainties relating to the forward-looking statements contained in this management’s discussion and analysis, please refer to the sections entitled Caution Regarding Forward-Looking Statements and Key Risks and Uncertainties.

INTRODUCTION

The Trust

This management’s discussion and analysis, dated March 14, 2008, is a year-over-year review of the activities, results of operations, liquidity and capital resources of the Fording Canadian Coal Trust (the Trust) and its subsidiaries on a consolidated basis. The Trust is an open-ended mutual fund trust existing under the laws of Alberta and governed by its Declaration of Trust. Its units are publicly traded in Canada on the TSX (FDG.UN) and in the United States on the NYSE (FDG). The Trust is not a trust company and it is not registered under any trust and loan company legislation as it does not carry on or intend to carry on the business of a trust company. References to “we”, “us” and “our” in this management’s discussion and analysis are to the Trust and its subsidiaries.

The Trust was formed in connection with a plan of arrangement effective February 28, 2003 (the 2003 Arrangement). Prior to August 24, 2005, the Trust held all of the shares and subordinated notes of its operating subsidiary company, Fording Inc. (the Corporation). Effective August 24, 2005, the Trust reorganized its structure by way of a plan of arrangement (the 2005 Arrangement) under which substantially all of the assets of the Corporation were transferred to a new entity, Fording Limited Partnership (Fording LP), and the Trust. The 2005 Arrangement created a flow-through structure whereby the Trust directly and indirectly owns all of the partnership interests of Fording LP, which holds the partnership interest in Elk Valley Coal Partnership (Elk Valley Coal) previously held by the Corporation.

1

Effective January 1, 2007, the Trust reorganized into a royalty trust. As a royalty trust, current provisions of the Canadian Income Tax Act do not limit the level of foreign ownership of the units of the Trust. The reorganization into a royalty trust did not change the distribution policy of the Trust or affect the amount of cash available for distribution to unitholders.

The Trust is a flow-through structure and under currently applicable Canadian income tax regulations all taxable income of the Trust is distributed to the unitholders without being taxed at the Trust level. The Trust does pay mineral taxes and Crown royalties to the provinces of British Columbia and Alberta. On June 22, 2007, the Federal Government of Canada enacted changes to Canadian income tax regulations that will result in the taxation of income and royalty trusts that were publicly traded as of October 31, 2006, other than certain real estate investment trusts, at effective rates similar to Canadian corporations commencing in 2011.

The Trust does not carry on any active business. The Trust directly and indirectly owns all of the interests of Fording LP, which holds a 60% interest in Elk Valley Coal. The Trust uses the cash it receives from its investments to make quarterly distributions to its unitholders.

The principal asset of the Trust is its 60% interest in Elk Valley Coal, which was created in connection with the 2003 Arrangement. Elk Valley Coal combined the metallurgical coal mining operations and assets formerly owned by Fording Inc. (the public company that was the predecessor of the Trust prior to the 2003 Arrangement), Teck Cominco Limited and/or its affiliates (Teck Cominco) and the Luscar/CONSOL joint ventures. Elk Valley Coal produces and distributes metallurgical coal from six mines located in British Columbia and Alberta, Canada. The Trust accounts for its interest in Elk Valley Coal as a joint venture using the proportionate consolidation method. Until June 2007, the Trust also held a 100% interest in NYCO, which mined and processed wollastonite and other industrial minerals at two operations in the United States and one operation in Mexico.

At the time of the 2003 Arrangement, the Trust held a 65% interest in Elk Valley Coal and Teck Cominco held the remaining 35%. The agreement governing Elk Valley Coal provided for an increase in Teck Cominco’s interest to a maximum of 40% to the extent that synergies realized from the combination of various metallurgical coal assets contributed to Elk Valley Coal exceeded certain target levels. The partners agreed that the synergy objectives were achieved and, as a result, the Trust’s interest in Elk Valley Coal was reduced to 62% effective April 1, 2004, to 61% on April 1, 2005, and to 60% on April 1, 2006. We accounted for the estimated effect of the 5% reduction of our interest in Elk Valley Coal in the second quarter of 2004, including an estimate of additional distribution entitlements to be received from Elk Valley Coal through March 31, 2006. The additional distribution entitlements received from Elk Valley Coal since March 31, 2004 were included in the Trust’s cash available for distribution over the period ending March 31, 2006.

The information in this management’s discussion and analysis should be read together with the consolidated financial statements, the notes thereto and other public disclosures of the Trust. Additional information relating to the Trust, including our annual information form, is available on SEDAR atwww.sedar.com, on EDGAR atwww.sec.gov, and on the Trust’s website atwww.fording.ca. The consolidated financial statements have been prepared in accordance with generally accepted accounting principles (GAAP) in Canada. These principles conform in all material respects with GAAP in the United States, except as disclosed in note 17 to the consolidated financial statements.

We report our financial information in Canadian dollars and all monetary amounts set forth herein are expressed in Canadian dollars unless specifically stated otherwise.

2

Elk Valley Coal Partnership

Elk Valley Coal is a general partnership between Fording LP and Teck Cominco. Our consolidated financial statements reflect our proportionate interest in Elk Valley Coal.

Teck Cominco is the managing partner of Elk Valley Coal and is responsible for managing its business and affairs, subject to certain matters that require the agreement of all partners. We are dependent upon Teck Cominco as managing partner of Elk Valley Coal and there is some risk to us should any conflict arise between the Trust, Elk Valley Coal and Teck Cominco. Should Teck Cominco not fulfill its obligations under the agreement governing Elk Valley Coal, fail to manage the business and affairs of Elk Valley Coal in a prudent manner or should conflicts of interest arise, there could be adverse effects on the amount of cash available for distribution to unitholders.

Elk Valley Coal is the second-largest supplier of seaborne hard coking coal in the world. Hard coking coal is a type of metallurgical coal used primarily for making coke by integrated steel mills, which account for substantially all global production of primary (i.e. unrecycled) steel. The seaborne hard coking coal market is characterized by the global nature of international steel making, the relative concentration of quality metallurgical coal deposits in Australia, Canada and the United States and the comparatively low cost of seaborne transportation.

Elk Valley Coal has an interest in six active mining operations. The Fording River, Coal Mountain, Line Creek, Elkview and Greenhills operations are located in the Elk Valley region of southeast British Columbia. The Cardinal River operation is located in west-central Alberta.

The Fording River, Coal Mountain, Line Creek and Cardinal River operations are wholly owned. The Greenhills operation is a joint venture in which Elk Valley Coal has an 80% interest. Elk Valley Coal holds, directly and indirectly, a 95% general partnership interest in the Elkview Operation.

Elk Valley Coal also owns numerous coal resources in British Columbia as well as a 46% interest in Neptune Bulk Terminals (Canada) Ltd. (Neptune Terminals), a coal loading facility located in North Vancouver, British Columbia.

NYCO

NYCO consisted of our former subsidiaries that operated wollastonite mining operations in New York State and Mexico and a tripoli mining operation in Missouri. In June 2007, we sold our interest in NYCO for cash proceeds of approximately $37 million, net of withholding taxes. Estimated income taxes owing on the net proceeds are $6 million. The distributable proceeds from the sale of NYCO, net of income taxes paid and payable, of $31 million, or $0.21 per unit, were included in cash available for distribution in 2007.

NYCO is presented as a discontinued operation in the accompanying consolidated financial statements.

NON-GAAP FINANCIAL MEASURES

This management’s discussion and analysis refers to certain financial measures, such as distributable cash, cash available for distribution, sustaining capital expenditures, income before unusual items, future income taxes and unrealized gains or losses on foreign exchange forward contracts, and the average realized Canadian dollar sales prices if realized gains and losses on foreign exchange forward contracts were included in revenues in 2007, that are not measures recognized under GAAP in Canada or the United States and do not have standardized meanings prescribed by GAAP. These measures may differ from those made by other issuers and, accordingly, may not be comparable to such measures as reported by other trusts or corporations. We discuss these measures, which have been derived from our financial statements and applied on a consistent basis, because we believe that they are of assistance in the understanding of the results of our operations and financial position, and provide further information about the ability of the Trust to earn and distribute cash to unitholders.

3

Cash available for distribution is the term used by us to describe the cash generated from our investments during a fiscal period that is available for distribution to unitholders. Actual distributions of cash to unitholders are made in accordance with our distribution policy.

Sustaining capital expenditures refers to expenditures in respect of capital asset additions, replacements or improvements required to maintain business operations at current production levels. The determination of what constitutes sustaining capital expenditures requires the judgment of management.

Income before unusual items, future income taxes and unrealized gains or losses on foreign exchange forward contracts is a non-GAAP measure of earnings. It adds back to net income determined in accordance with GAAP the impact of future taxes and unrealized gains or losses on foreign exchange forward contracts, which are non-cash and may be subject to significant change until realized, as well as unusual items that are significant and not expected to be recurring.

CONTROLS AND PROCEDURES

Management is responsible for establishing and maintaining adequate disclosure controls and procedures as well as adequate internal control over financial reporting. Disclosure controls and procedures are designed to ensure that information required to be disclosed in U.S. filings is recorded, processed, summarized and reported within appropriate time periods. Internal control over financial reporting is a process designed to provide reasonable assurance regarding the reliability of financial reporting and the preparation of consolidated financial statements for external reporting purposes in accordance with GAAP. Internal control over financial reporting may not prevent or detect fraud or misstatements because of limitations inherent in any system of internal control.

As an inter-listed trust, we are subject to the laws, rules and requirements of both Canada and the United States and the TSX and NYSE, including the requirement that we evaluate the effectiveness of both our disclosure controls and procedures and our internal control over financial reporting. As of December 31, 2007 an evaluation of the disclosure controls and procedures was carried out under the supervision of and participation of management. Based on that evaluation, management determined that disclosure controls and procedures are effective. Management, with the participation of our president and chief financial officer, conducted an evaluation of the effectiveness of our internal control over financial reporting based on the framework set out inInternal Control — Integrated Frameworkissued by the Committee of Sponsoring Organizations of the Treadway Commission (COSO). Based on this evaluation, management concluded that our internal control over financial reporting was effective as of December 31, 2007 based on the criteria set out inInternal Control — Integrated Frameworkissued by COSO.

4

OVERVIEW

Highlights

| | | | | | | | | | | | | |

| (millions of Canadian dollars, except as noted) | | 2007 | | | 2006 | | | 2005 | |

| | | | | | | | | | | | | |

| Revenue | | $ | 1,427.3 | | | $ | 1,798.2 | | | $ | 1,829.9 | |

| Income from operations | | | 308.2 | | | | 682.9 | | | | 776.2 | |

| Net income from continuing operations | | | 322.5 | | | | 542.9 | | | | 834.3 | |

| Add (deduct): | | | | | | | | | | | | |

| Future income tax expense (reversal) | | | 73.0 | | | | 9.2 | | | | (97.0 | ) |

| Unrealized gains on foreign exchange forward contracts | | | (38.7 | ) | | | — | | | | — | |

| Change in accounting standards for in-process inventory | | | — | | | | 31.7 | | | | — | |

| Gain from reduction of interest in Elk Valley Coal | | | — | | | | — | | | | (5.4 | ) |

| Gain on issuance of partnership interest | | | — | | | | — | | | | (27.2 | ) |

| | | | | | | | | | |

| Net income from continuing operations before unusual items, future income taxes and unrealized gains or losses on foreign exchange forward contracts | | $ | 356.8 | | | $ | 583.8 | | | $ | 704.7 | |

| | | | | | | | | | |

| | | | | | | | | | | | | |

| Cash available for distribution | | $ | 348.9 | | | $ | 617.8 | | | $ | 721.6 | |

| Distributions declared | | $ | 358.8 | | | $ | 610.2 | | | $ | 700.6 | |

| | | | | | | | | | | | | |

| Net income from continuing operations per unit | | $ | 2.18 | | | $ | 3.69 | | | $ | 5.68 | |

| Net income from continuing operations per unit before unusual items, future income taxes and unrealized gains or losses on foreign exchange forward contracts | | $ | 2.41 | | | $ | 3.97 | | | $ | 4.79 | |

| | | | | | | | | | | | | |

| Cash available for distribution per unit | | $ | 2.36 | | | $ | 4.20 | | | $ | 4.91 | |

| Distributions declared per unit | | $ | 2.43 | | | $ | 4.15 | | | $ | 4.76 | |

| | | | | | | | | | | | | |

| Total assets | | $ | 1,086.8 | | | $ | 1,073.8 | | | $ | 1,182.6 | |

| Total long-term debt | | $ | 280.9 | | | $ | 312.5 | | | $ | 215.2 | |

| | | | | | | | | | | | | |

Coal sales — Trust’s 60% share(millions of tonnes) | | | 13.6 | | | | 13.6 | | | | 14.5 | |

Our financial results from 2005 through 2007 reflect successive decreases in U.S. dollar coal prices for the 2006 and 2007 coal years. Elk Valley Coal’s average selling prices decreased by 12% to approximately US$107 per tonne for the 2006 coal year, which ran from April 1, 2006 to March 31, 2007, and further decreased by 13% to approximately US$93 per tonne for the 2007 coal year. The strengthening of the Canadian dollar relative to the U.S. dollar and increases in Elk Valley Coal’s unit cost of product sold due primarily to significant inflation in the cost of mining inputs, including labour, contractor services, diesel fuel, tires and other consumables, also contributed to the decreases in income and cash available for distribution over this three-year period.

5

STRATEGY AND KEY PERFORMANCE INDICATORS

Strategy

Our goal has been to use our investment in Elk Valley Coal’s long-lived assets, which have a history of strong performance, to provide for distributions to our unitholders over the long term. On December 5, 2007, our Trustees announced that independent committees had been formed to explore and make recommendations regarding strategic alternatives that may be available to the Trust to maximize value for its unitholders. The independent committees were given a broad mandate to consider a wide range of alternatives including an acquisition of all of the Trust’s outstanding units by a third party, a sale of its assets, including its interest in Elk Valley Coal, a combination, reorganization or similar form of transaction or continuing with its current business plan. It is anticipated that no further announcements will be made regarding any strategic alternatives unless and until the Trustees determine disclosure of a material change is required.

Cash available for distribution is generated primarily from our investment in Elk Valley Coal and will be significantly affected by Elk Valley Coal’s success in executing its business plan over the long term. Elk Valley Coal’s vision is to be a leader in the global metallurgical coal industry; trusted and valued by its customers, its investors, its employees and its communities.

Key Performance Indicators

Key performance indicators for Elk Valley Coal are safety performance, quality control, unit transportation costs and unit cost of product sold, which includes material and clean coal productivities, plant yield, strip ratios and haul distances. Elk Valley Coal monitors and assesses lost time and medical aid incident frequencies and lost time incident severity. Quality indicators focus on the delivery of coal within established product specifications on a consistent basis. Mining improvements are measured by productivity gains in the mines. Sound environmental performance is demonstrated by controlling the impact of activities on the environment through work practices and complying with or exceeding applicable laws and regulations. Elk Valley Coal continuously reviews and monitors these performance indicators.

NATURE OF OPERATIONS

The Steel and Metallurgical Coal Industries

Integrated steel mills account for substantially all global production of primary (i.e. unrecycled) steel. Integrated steel mills depend on metallurgical coal and iron ore as the two primary inputs for making steel. There are three main categories of metallurgical coal. The categories are separated by reference to their chemical and physical properties. These differences, in turn, result in differentiation in pricing, which has become quite significant in recent years. Hard coking coals form high-strength coke, semi-soft coking coals produce coke of lesser quality and pulverized coal for injection is used for its heat value and is not typically a coking coal. Semi-soft and pulverized coals normally have lower sales values compared with hard coking coal due to marked differences in quality and broader availability. Recent trends in coal marketing and purchasing have led to the stratification of hard coking coals into quality groupings based on their chemical and physical properties, with prices varying significantly between these groups. The highest-quality hard coking coals are relatively scarce and, accordingly, command the best prices. A key strategic priority for Elk Valley Coal is to maximize the quality and consistency of its products so that it continues to produce hard coking coals that are classified within the highest-quality groupings.

6

The demand for hard coking coals is closely correlated with the steel production of integrated steel mills. However, other factors can influence demand. The substantially lower pricing for semi-soft and pulverized coals encourages integrated steel mills to substitute these coals, to the extent their processes allow, in an attempt to reduce the total cost of steel production. This substitution tends to have technical limits. Use of semi-soft coals reduces the productivity of coke ovens and blast furnaces. Increased use of pulverized coals reduces overall coking coal requirements but, in turn, necessitates the use of higher-quality hard coking coals. Therefore, substitution can increase when the steel mills operate at lower rates of productivity and when the price differential between hard coking and other coals widens. There is also an impact on hard coking coal demand when steel mills purchase supplies of finished coke. Approximately two-thirds of the hard coking coal needs of integrated steel mills and other producers of coke are met by domestic production or by production delivered overland. The remaining needs are satisfied by importing hard coking coal through seaborne trade.

There are currently no technologically feasible and cost-effective alternatives to using coking coal in the steel-making process. Changes to the steel-making process tend to occur gradually. Research into alternative technologies has been ongoing for many years, but to date the alternatives to using coking coal, such as direct smelting or hydrogen-reduction technologies, have generally not been feasible or cost-justified on a large commercial scale. However, the high prices and limited supplies of hard coking coals that have been experienced in recent years, combined with public pressure and government action to reduce carbon dioxide emissions, are expected to place increased focus on alternative technologies in the future. Alternative technologies may eventually displace some of the demand for hard coking coal, although the time frame for this change is expected to be relatively extended.

The demand side of the seaborne hard coking coal market is more fragmented than the supply side; however, the major steel producers have historically formed both formal and informal alliances to improve their bargaining leverage. In addition, there has been a trend toward consolidation among steel producers in recent years. In particular, the Mittal Group has acquired a number of other steel producers and has created the world’s largest steel company. Industry consolidation generally increases the purchasing power and bargaining strength of these customers although, recently, other factors including strong demand and perceived shortages of supply have sustained hard coking coal prices at historically high levels.

Since 2003, global steel production, and hence the demand for hard coking coal, has grown dramatically, driven primarily by rapid industrialization and economic development in the emerging economies of China, India, Russia and Brazil, commonly referred to as the “BRIC” countries. This is in contrast to the many years of relatively stable demand and stagnant prices for steel and hard coking coal that preceded 2003. The rapid development of the BRIC countries is expected to further increase the volatility of the global steel and hard coking coal markets in the future because these countries will likely experience sudden and irregular swings in their economic development. Accordingly, we expect to experience increased volatility in our financial results in future years. A strategic priority for Elk Valley Coal is to position itself so that it can react appropriately and efficiently to sudden fluctuations in demand and prices. This will generally require increased flexibility across all of Elk Valley Coal’s business operations. For example, increased flexibility in its mine plans is required so that production levels and product mix can be adjusted more quickly in response to changing market conditions. It is anticipated that, going forward, Elk Valley Coal’s marketing strategies will be developed based on a presumption of increased volatility in sales prices and volumes. Also, flexibility in financing structures will be needed to accommodate the fluctuations and volatility in cash flows that may occur during these cycles.

China, in particular, is a key influence on the global steel and hard coking coal markets. The significant construction boom in China has required it to dramatically increase its domestic steel production capacity. China does not currently import a significant amount of seaborne hard coking coal because the requirements of its domestic steel mills can generally be met by Chinese coal producers and imports from Mongolia. In fact, China is the world’s largest producer of metallurgical coal, but it does not currently export significant quantities because domestic demand is so strong. However, an economic downturn in China could potentially cause its exports of hard coking coal to increase in the future. Elk Valley Coal does not currently sell significant quantities of coal to China, but it has benefitted indirectly from the growth in China because it sells coal to the large integrated steel mills elsewhere in Asia that help supply the Chinese market.

7

Competitive Position

Elk Valley Coal is the second-largest supplier of seaborne hard coking coal in the world, with approximately 15% of the global seaborne market in 2007. The other main producing regions of seaborne hard coking coal are Australia and the United States. The principal competitors to Elk Valley Coal are Australian producers and include the BHP Billiton/Mitsubishi Alliance, Anglo American Plc./Mitsui & Co. Ltd. and Xstrata Plc. New sources of supply of hard coking coal from Australia are expected to come into the market over the next few years. While not all of these new sources are expected to produce the highest quality hard coking coal, the supply will compete directly with some of Elk Valley Coal’s products.

Undeveloped reserves of high-quality metallurgical coal have been identified in Mongolia, Russia, Mozambique and other locations. These reserves have the potential to add a significant amount of supply in the longer term. There are significant economic, logistical and political challenges involved in developing these new reserves; however, the historically high prices and relative scarcity of high-quality hard coking coal experienced in recent years increases the likelihood that some of these high-quality deposits will be developed.

Nearly all of Elk Valley Coal’s production is hard coking coal, including a high proportion of high-quality hard coking coal products and a range of other products. Generally, these coal products are comparable in quality with those of Elk Valley Coal’s competitors and perform well when blended by customers with other coals. The varying chemical and physical properties of its coal products, their relative supply and demand in the marketplace and any differences in ocean freight costs into various markets result in differentiation in pricing between Elk Valley Coal’s various hard coking coal products. In response to trends toward increased stratification of hard coking coal qualities and, therefore, prices, Elk Valley Coal is producing products and structuring its operations to preserve the value of its highest-quality coals. Approximately 10% of Elk Valley Coal’s production is sold as thermal coal or as pulverized coal to steel mills.

On the whole, the cost of production for Elk Valley Coal is competitive with that of the average Australian producer. However, that competitive position can depend on a number of factors, including the type of operations of a particular competitor and foreign currency exchange rates. Elk Valley Coal operates in mountainous regions whereas Australian metallurgical coal production is generally from open-pit mines in non-mountainous terrain using dragline and truck and shovel methods, or from underground operations. Metallurgical coal production in the United States is generally from underground operations in the eastern states.

Transportation costs, including rail and port services, are significant to Elk Valley Coal and generally determine its competitiveness. Rail costs are high in comparison to Elk Valley Coal’s primary competitors in Australia because most of its coal is shipped through difficult terrain to west-coast ports that are over 1,100 kilometres from its mines. However, rail costs are also high because there are no cost-effective alternatives to Elk Valley Coal’s rail service providers, which impacts its ability to negotiate competitive rates and service levels. These factors, combined with its high port costs, place Elk Valley Coal at a competitive disadvantage and result in it being a relatively high-cost producer compared with its peers in the global metallurgical coal industry. As a higher cost producer, Elk Valley Coal is subject to greater risks in a highly competitive market. Australian producers generally have a marked cost advantage over Elk Valley Coal because their mining operations are located much closer to tidewater, the rail lines run through more even terrain and because there are competitive mechanisms for rail service.

8

Operating the Business

Selling coal

Elk Valley Coal currently has approximately 45 customers around the world. Most of its customers are integrated steel mills, the largest of which are located in South Korea and Japan. A breakdown of sales revenue by geographic region is as follows:

| | | | | | | | | | | | | |

| Elk Valley Coal sales by region (%) | | 2007 | | | 2006 | | | 2005 | |

| | | | | | | | | | | | | |

| Asia | | | 47 | | | | 45 | | | | 45 | |

| Europe | | | 33 | | | | 35 | | | | 34 | |

| North America | | | 14 | | | | 11 | | | | 13 | |

| South America | | | 6 | | | | 9 | | | | 8 | |

Elk Valley Coal sells substantially all of its coal pursuant to evergreen contracts or long-term supply agreements. Evergreen contracts allow for pricing of specified volumes of coal to be set annually and require one or two year’s notice of termination by either party. Long-term supply agreements provide for the purchase of specified volumes of coal each year for a specified number of years, but allow prices to be set annually. Historically, less than 10% of Elk Valley Coal’s sales have been based on spot market prices, which is typical for the seaborne hard coking coal market. Coal is generally priced on an annual basis for the 12-month period that starts April 1, referred to as the coal year. In other cases, coal is priced on a calendar year basis or another 12-month period that differs from the typical coal year.

Evergreen contracts and long-term supply agreements have traditionally been used to reduce some of the risk associated with sales and production volumes by providing more certainty and stability of sales volumes from year to year. However, within the calendar year the timing of coal sales is largely dependent on customers as they determine when vessels are nominated to receive shipments and it is not unusual for some sales volume to be carried over from one coal year into the next. In recent years, the amount of this carryover has increased. A strategic priority for Elk Valley Coal is to negotiate contract volumes that are more consistent with each customer’s underlying buying patterns in order to improve predictability.

The usual terms of sale for seaborne coking coal result in customers taking title to coal once it is loaded onto vessels at the shipping port. Elk Valley Coal’s customers typically arrange and pay for ocean freight and off-loading from vessels at the destination port. In some cases, Elk Valley Coal pays these costs, selling the coal on terms such that title to the coal transfers at the shipping destination. Higher prices are negotiated for these sales to cover the ocean freight rates and the costs of ocean freight are reflected in transportation costs.

Transporting coal

Elk Valley Coal transports approximately 90% of its coal to ports in Vancouver, British Columbia utilizing two rail service providers. Canadian Pacific Railway Limited (Canadian Pacific) provides services to the five operations in the Elk Valley region in southeast British Columbia, and Canadian National Railway Company (Canadian National) provides services to the Cardinal River operation in west-central Alberta. There are currently no cost-effective alternatives to these providers for the volume of coal produced by these mines, which affects Elk Valley Coal’s ability to negotiate competitive service rates. Elk Valley Coal has a five-year agreement with Canadian Pacific for the westbound movement of its coal, which expires in March 2009. The rates under the agreement consist of a base rate and premiums if U.S. dollar coal prices and West Texas Intermediate crude oil prices are within certain parameters. The agreement with Canadian National expires in January 2009 and consists of a base rate plus a fuel surcharge.

9

Westshore Terminals in Vancouver handles most of the shipments loaded onto vessels. Neptune Terminals in North Vancouver, which is 46% owned by Elk Valley Coal, loads the balance of west-coast shipments. There are generally no cost-effective alternatives to these port facilities. Loading agreements with Westshore Terminals expire in March 2010 for the Elkview operation and in March 2012 for the Fording River, Greenhills and Coal Mountain operations. The agreement with Westshore Terminals for the Line Creek operation expired on March 31, 2007 and Elk Valley Coal is currently shipping under interim arrangements. The loading costs under the Westshore Terminals contracts are partially linked to the average Canadian dollar price that Elk Valley Coal receives for coal. Loading rates for Neptune Terminals are based on the actual costs allocated to the handling of coal at that facility.

Charges for demurrage by vessel owners for waiting times are incurred if there are loading problems or scheduling issues at the port or if there is a shortage of the specified coal at the port because of, for example, weather problems that interfere with the transportation of coal. Recently, vessel demurrage costs have increased significantly due to higher demurrage rates being charged by vessel owners as well as longer vessel wait times due to low inventories at the ports resulting from shortfalls in rail shipments. Ocean freight rates, including vessel demurrage rates, have increased significantly due to strong global demand for shipping services and rising fuel costs. Rising ocean freight rates, other than vessel demurrage rates, have little direct impact on Elk Valley Coal because the customer generally pays the ocean freight (either directly or through higher negotiated coal prices). Rising ocean freight costs can have an adverse indirect effect on Elk Valley Coal’s competitiveness, however, because it increases the overall cost of its products, which could make other suppliers that are geographically closer to the customer more attractive.

Approximately 10% of coal shipments are eastbound and delivered to North American customers by rail or by rail and ship via Thunder Bay Terminals in Thunder Bay, Ontario. Canadian Pacific handles Elk Valley Coal’s eastbound rail transportation under a contract that expires in December 2009.

The impact of the variability of our rail and port contracts with coal prices in the 2008 calendar year is estimated to be approximately $0.05 of additional transportation cost for each $1.00 change in the average Canadian dollar coal prices above $100 per tonne.

Mining coal

Elk Valley Coal employs conventional open-pit mining techniques using large haul trucks and electric or hydraulic shovels. Overburden rock is drilled and blasted with explosives and is then loaded onto trucks by shovels and hauled outside of the mining area. Once the overburden is removed, the raw coal is typically recovered from the seam by bulldozers and is loaded onto haul trucks by front-end loaders and shovels for transport to the coal preparation plants. These plants employ breakers, which size the raw coal and remove large rocks, wash the raw coal of ash and impurities using conventional techniques and then dry the clean coal using dryers that utilize coal or natural gas for fuel.

Movement of rock overburden constitutes a significant portion of the unit cost of product sold because considerably more rock overburden must be blasted and moved outside of the active mining area compared with the volume of coal recovered from the underlying seams. Typically, more than 20 tonnes of rock must be moved for every tonne of coal produced, which equates to a strip ratio of approximately 8-9 bank cubic metres of rock overburden moved for each tonne of clean coal produced. Certain key variables are carefully managed with a view to the long-term economic viability of the coal reserve.

| | • | | Thestrip ratiois the average volume (bank cubic metres) of rock that must be moved for each tonne of clean coal produced and can vary from period to period around a long-term trend. The strip ratio impacts the size of the mining fleet, plant productivity and the cost of mining inputs such as labour, tires and fuel. A lower strip ratio normally reduces the unit cost of product sold. |

10

| | • | | Thehaul distanceis the one-way distance the trucks, on average, have to travel to move the overburden. The haul distance impacts the size of the mining fleet, productivity in the mine and the cost of mining inputs such as labour, tires and fuel. Shorter haul distances normally result in lower cost of product sold. |

| |

| | • | | Totalmaterial productivityis a measure of operational efficiency, stated in the volume of rock and coal moved per eight-hour work shift. Higher productivity, which depends on such things as mine design, employee levels, size of the mining fleet, haul distance and equipment availability and capacity, normally reduces the unit cost of product sold. |

Changing technology and the use of larger equipment can reduce mining costs and increase productivity, which could make mining areas with higher strip ratios or longer haul distances economic and increase recoverable coal. The outlook for hard coking coal prices also helps to determine which strip ratios and haul distances can be economic. Mining costs are also impacted by the cost of various inputs such as labour, maintenance, fuel and other consumables. There has been significant inflation in mining input costs in recent years. Western Canada has been experiencing an economic boom and Elk Valley Coal operates in a very tight labour market. The availability of employees and contractors has been constrained, which has placed upward pressure on costs. The prices of diesel fuel and haul truck tires, which are major cost drivers for Elk Valley Coal, have also risen significantly.

The estimated physical mining capacity of Elk Valley Coal (including only its share of production from the Greenhills operation) for 2008 is approximately 25 million tonnes, which is down from 26 million tonnes reported in 2006. Capital expansion projects at the Elkview, Cardinal River and Fording River operations that were substantially completed in 2004 and 2005 were undertaken with the belief that the projects would increase Elk Valley Coal’s physical mining capacity to approximately 30 million tonnes by 2007. Subsequent adverse changes in assumptions regarding future mining conditions, particularly at the Fording River and Elkview operations, have resulted in less physical mining capacity than was originally anticipated when these expansion projects were undertaken.

The physical mining capacity is based on current long-range mine plans, which reflect expectations for a number of physical considerations such as strip ratios, haul distances and the size of the mining fleet. Changes to mine plans, for example, to respond to market factors or geological issues, can affect physical capacity. Elk Valley Coal’s current long-range mine plans include higher strip ratios and longer haul distances over the next several years.

Effective capacity can be influenced by product requirements and other factors such as labour and contractor availability, rail and port performance and parts supply. For example, in recent years the lack of readily available haul truck tires constrained Elk Valley Coal’s effective capacity to approximately 25 million tonnes. During 2007, rail transportation problems further constrained Elk Valley Coal’s effective capacity. Elk Valley Coal is currently operating in a very tight labour market and there are critical shortages of skilled trades people and experienced equipment operators in western Canada, which may restrict its effective capacity in the future.

Based on current long-range mine and capital spending plans, Elk Valley Coal expects its physical mining capacity to gradually increase to approximately 27 million tonnes by 2010. However, effective capacity may be constrained over this period unless the frequency and timeliness of rail shipments increases from 2007 levels and the availability of haul truck tires improves.

11

Coal preparation plant processing includes the washing and drying of coal for sale. Washing coal removes impurities such as rock and ash. Drying the coal after washing reduces the moisture level of the coal in order to meet customers’ specifications. Certain key variables related to processing coal are also carefully managed with a long-term view to optimal mine operations.

| | • | | The percentage of clean product recovered compared with the amount of raw coal processed is referred to asplant yield. The yield achieved is a function of the physical characteristics of raw coal being processed and the amount of ash and impurities in the raw coal. In the cleaning process, ash in the raw coal is removed to acceptable levels for the production of coke for the steel-making process. Generally, a higher yield lowers the unit cost of product sold. |

| |

| | • | | Clean coal productivityis a measure of the overall operational efficiency of the coal preparation plant and minesite operations. It is stated as the amount of clean coal produced per eight-hour work shift. In addition to factors that affect productivity in the mining operations, productivity for coal preparation plants is dependent upon plant design and site employee levels. |

Mining and plant equipment and other infrastructure must be maintained. Scheduled shutdowns of operations, which are typically built into our production plans, may be taken at various times throughout the year to provide for employee vacations and allow for maintenance activities. Generally, scheduled shutdowns occur in July and August, which adversely impacts production volumes and unit costs in the third quarter.

2007 COMPARED WITH 2006

Results of Operations (Trust’s 60% Share)

| | | | | | | | | | | | | |

| Volumes and prices | | 2007 | | | 2006 | | | 2005 | |

| | | | | | | | | | | | | |

Coal production(millions of tonnes) | | | 13.5 | | | | 13.1 | | | | 15.4 | |

Coal sales(millions of tonnes) | | | 13.6 | | | | 13.6 | | | | 14.5 | |

| Average sales price (US$per tonne) | | $ | 97.70 | | | $ | 113.10 | | | $ | 99.30 | |

Average sales price1 | | $ | 104.90 | | | $ | 132.50 | | | $ | 126.40 | |

| | | | | | | | | | | | | |

Operating results(millions of dollars) | | | | | | | | | | | | |

| Revenue | | $ | 1,427.3 | | | $ | 1,798.2 | | | $ | 1,829.9 | |

| Cost of product sold | | | 562.0 | | | | 532.3 | | | | 469.2 | |

| Transportation | | | 478.0 | | | | 500.3 | | | | 510.2 | |

| Selling, general and administration | | | 20.0 | | | | 23.4 | | | | 17.2 | |

| Depreciation and depletion | | | 49.8 | | | | 49.2 | | | | 47.5 | |

| | | | | | | | | | |

| | | | | | | | | | | | | |

| Income from operations | | $ | 317.5 | | | $ | 693.0 | | | $ | 785.8 | |

| | | | | | | | | | |

| | | |

| 1 | | The average sales prices for 2006 and 2005 include the realized effects of our foreign exchange forward contracts of $4.20 per tonne in 2006 and $6.60 per tonne in 2005. |

Revenues

Revenues decreased by 21% from $1.8 billion in 2006 to $1.4 billion in 2007 due to lower U.S. dollar coal prices and the effect of the stronger Canadian dollar relative to the U.S. dollar in 2007. Average U.S. dollar coal prices for 2007 calendar year decreased by 14% to US$97.70 per tonne as a result of successive decreases in prices for the 2006 and 2007 coal years.

12

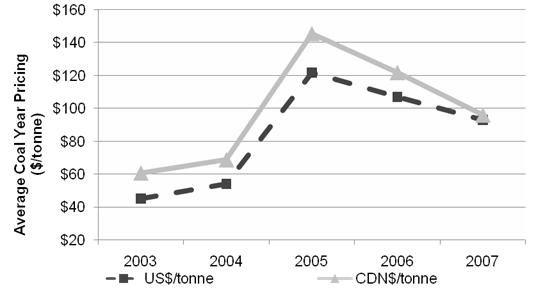

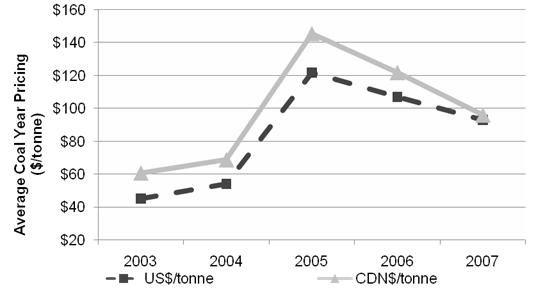

The following graph presents Elk Valley Coal’s average U.S. and Canadian dollar coal-year prices for 2003 through 2007. The graph highlights the volatility in Elk Valley Coal’s average coal-year selling prices that has occurred since 2003 and assists with the explanations of revenue variances. Substantially all of Elk Valley Coal’s sales are denominated in U.S. dollars. The Canadian dollar equivalent prices are included in the graph to demonstrate the impact of general changes in the U.S./Canadian dollar exchange rate. The Canadian dollar equivalent prices presented in the graph exclude the effects of our foreign exchange forward contracts:

Elk Valley Coal believes that the global metallurgical coal markets have entered a period of unprecedented volatility. Elk Valley Coal’s prices for the 2005 coal year (April 1, 2005 to March 31, 2006) reached historically high levels of approximately US$122 per tonne, which was more than double the prices for the 2004 coal year. The 2005 coal year prices reflected the confluence of strong growth in demand for steel, driven largely by the rapid industrialization and economic development of China and the other BRIC countries, and coal production and delivery problems that constrained global supplies of hard coking coal at that time. Negotiations for the 2006 coal year were conducted under different circumstances. In late 2005, some integrated steel mills slowed deliveries of hard coking coal and substituted coals of lesser quality in response to the widening price gap between hard coking coal and semi soft coking coals. At the same time, the global supply of hard coking coal increased. As a result, prices came off historically high levels and Elk Valley Coal’s average prices for the 2006 coal year declined by 12% to approximately US$107 per tonne.

Leading into the 2007 coal year negotiations, continuing substitution of lesser quality coals and increasing global supply of hard coking coal caused further downward pressure on prices and Elk Valley Coal’s average prices fell by a further 13% to approximately US$93 per tonne for the 2007 coal year. The 2007 coal year prices represented a significant decline relative to the 2005 coal year, but in comparison to the many preceding years of low prices and slow growth in demand, the 2007 coal year prices remained relatively high. During 2007, the global metallurgical coal markets shifted dramatically and by the end of 2007 the market was in tight supply because of growing demand and lower than expected growth in exports from Australian suppliers. In late 2007, spot sales of hard coking coal by other coal producers were occurring at very high prices as many integrated steel mills faced critically low inventories.

13

The average realized Canadian dollar coal price decreased by 21% to $104.90 per tonne in 2007. The decrease in the average realized Canadian dollar sales price was greater than the percentage decrease in the average U.S. dollar price because the Canadian dollar has strengthened significantly against the U.S. dollar and because of the change in accounting for our foreign exchange forward contracts. Our forward contracts are not designated as hedges under the new accounting standards for financial instruments that became effective on January 1, 2007 and, accordingly, realized gains or losses on the contracts are no longer included in revenues or in the average Canadian dollar sales price. Realized gains on the forward contracts in 2007 were $75 million, which were recorded as non-operating income. If these realized gains had been included in revenue in 2007, the average realized sales prices would have been $110.40 per tonne.

The revenue variances for 2007 compared with 2006 are summarized in the following table:

| | | | | |

| (millions of Canadian dollars) | | | | |

| | | | | |

| Revenue in 2006 | | $ | 1,798 | |

| Variance attributed to lower U.S. dollar coal prices | | | (225 | ) |

| Variance attributed to the change in the U.S./Canadian dollar exchange rate | | | (94 | ) |

| Realized gains on foreign exchange forward contracts included in revenue in 2006 | | | (58 | ) |

| Variance attributed to coal sales volumes | | | 6 | |

| | | | |

| | | | | |

| Revenue in 2007 | | $ | 1,427 | |

| | | | |

| | | | | | | | | | | | | |

| Cost of Product Sold | | 2007 | | | 2006 | | | 2005 | |

| | | | | | | | | | | | | |

Coal sales(millions of tonnes) | | | 13.6 | | | | 13.6 | | | | 14.5 | |

Coal production(million of tonnes) | | | 13.5 | | | | 13.1 | | | | 15.4 | |

Cost of product sold(millions of dollars) | | $ | 562.0 | | | $ | 532.3 | | | $ | 469.2 | |

Cost of product sold(per tonne) | | $ | 41.30 | | | $ | 39.20 | | | $ | 32.40 | |

Cost of product sold includes expenses to move overburden and extract, clean and dry coal. It also includes other expenses such as engineering, exploration and the administration of the mine site, including head office costs related to operations. It excludes transportation costs, selling, general and administration costs such as the costs of marketing products, commissions on sales and certain head office costs not related to the production of coal.

| | | | | | | | | | | | | |

| Operating statistics | | 2007 | | | 2006 | | | 2005 | |

| | | | | | | | | | | | | |

Total material moved(millions of bank cubic metres) | | | 134.6 | | | | 136.8 | | | | 154.2 | |

Strip ratio(bank cubic metres of waste rock per tonne of clean coal produced) | | | 8.5 | | | | 9.0 | | | | 8.5 | |

Haul distance(kilometres per haul) | | | 3.4 | | | | 3.1 | | | | 2.8 | |

Total material productivity(bank cubic metres per 8-hour work shift) | | | 320.2 | | | | 330.9 | | | | 360.1 | |

Plant yield(percent) | | | 65 | | | | 64 | | | | 65 | |

Clean coal productivity(tonnes of clean coal produced per 8-hour work shift) | | | 33.4 | | | | 32.8 | | | | 37.4 | |

14

Cost of product sold increased by $30 million, or 6%, over 2006 due primarily to higher input costs. The unit cost of product sold increased by 5%, or $2.10 per tonne, to $41.30 per tonne. The prices for diesel fuel, tires and other consumables increased for a number of reasons including higher crude oil prices, global shortages in the supply of haul truck tires and generally higher inflation. The cost of contractor services has increased due to strong demand for contractors in the booming western Canadian economy.

Production levels in 2007 were 4% higher than in 2006 in response to stronger demand from Elk Valley Coal’s customers, although production and sales levels were constrained by shortfalls in rail shipments during 2007. As a result, Elk Valley Coal ended 2007 with low inventories at the ports and relatively high inventories at the mines.

The benefit of lower strip ratios in 2007 was partially offset by longer haul distances. Strip ratios decreased and haul distances increased due to normal variations in mining conditions.

Total material productivity has decreased by 11% since 2005 due largely to higher rates of employee turnover, which has reduced the average experience level of Elk Valley Coal’s employees and increased training requirements. The labour market in western Canada is very tight and there is strong demand for the skills possessed by Elk Valley Coal’s employees, particularly by oil sands projects. There is also a critical shortage of experienced equipment operators and skilled tradespeople generally. Longer haul distances also contributed to lower material productivity in 2007.

| | | | | | | | | | | | | |

| Transportation Costs | | 2007 | | | 2006 | | | 2005 | |

| | | | | | | | | | | | | |

Coal sales(millions of tonnes) | | | 13.6 | | | | 13.6 | | | | 14.5 | |

Transportation(millions of dollars) | | $ | 478.0 | | | $ | 500.3 | | | $ | 510.2 | |

Transportation(per tonne) | | $ | 35.10 | | | $ | 36.90 | | | $ | 35.30 | |

Transportation costs consist primarily of the cost of rail service to move coal to ports and port charges for the handling, storage and loading of coal onto vessels. Other costs include ocean freight that is the responsibility of Elk Valley Coal, demurrage charges for vessel waiting times and coal testing fees.

Transportation and other costs decreased by $22 million, or 4%, from 2006. Rail rates decreased in 2007, particularly for westbound shipments from the mines in the Elk Valley. Under the agreement with Canadian Pacific that expires in March 2009, the rates for the 2007 coal year, which commenced April 1, 2007, were based partly on Elk Valley Coal’s average U.S. dollar selling prices. The decrease in U.S. dollar prices for the 2007 coal year resulted in a decrease in the westbound rail rates paid to Canadian Pacific compared with the prior year.

Port rates decreased from 2006 levels due primarily to lower realized Canadian dollar coal prices, which affect loading rates charged by Westshore Terminals.

The benefits of lower rail and port costs in 2007 were partially offset by an increase in vessel demurrage costs due to longer vessel wait times and higher demurrage rates. Port inventories were at low levels during 2007 due to shortfalls in rail shipments, which resulted in longer vessel wait times and increased demurrage costs.

15

Other Income and Expenses

| | | | | | | | | | | | | |

| (millions of Canadian dollars) | | 2007 | | | 2006 | | | 2005 | |

| | | | | | | | | | | | | |

| Interest expense | | $ | (21.4 | ) | | $ | (18.8 | ) | | $ | (11.3 | ) |

| | | | | | | | | | |

| | | | | | | | | | | | | |

| Net foreign exchange gains (losses) | | $ | 31.0 | | | $ | (5.6 | ) | | $ | 4.2 | |

Realized gains on foreign exchange forward contracts1 | | | 74.5 | | | | — | | | | — | |

Unrealized gains on foreign exchange forward contracts2 | | | 38.7 | | | | — | | | | — | |

| Change in accounting policy for in-process inventory | | | — | | �� | | (31.7 | ) | | | — | |

| Gain on issuance of partnership interest | | | — | | | | — | | | | 27.2 | |

| Gain on corporate reorganization | | | — | | | | — | | | | 5.4 | |

| Other | | | 3.2 | | | | 0.5 | | | | (1.8 | ) |

| | | | | | | | | | |

| | | | | | | | | | | | | |

| | | $ | 147.4 | | | $ | (36.8 | ) | | $ | 35.0 | |

| | | | | | | | | | |

| | | |

| 1 | | Realized gains or losses on foreign exchange forward contracts were included in revenues in 2006 and 2005 under previous accounting standards. |

| |

| 2 | | Unrealized gains or losses on foreign exchange forward contracts were not recorded in 2006 or 2005 under previous accounting standards. |

The significant strengthening of the Canadian dollar during 2007 resulted in unrealized foreign exchange gains on our U.S. dollar-denominated long-term debt of $47 million. These unrealized gains were partially offset by foreign exchange losses recorded on our U.S. dollar cash and accounts receivable balances, resulting in net foreign exchange gains of $31 million for the year compared with a net loss of $6 million in 2006.

In 2007, other income includes realized gains of $75 million on the foreign exchange forward contracts that matured during the year. Prior to 2007, realized gains and losses on the forward contracts were included in revenue because the contracts were designated as hedges under the previous accounting standards.

The fair value of our outstanding foreign exchange forward contracts as at December 31, 2007 was $39 million, which is recorded as an unrealized gain. Prior to 2007, we did not record unrealized gains or losses on our foreign exchange forward contracts under the previous accounting standards.

At the beginning of 2006, we adopted a new accounting standard for in-process inventory, which resulted in a non-cash charge to earnings of $32 million.

16

Income Taxes

| | | | | | | | | | | | | |

| | | Years ended December 31 | |

| (millions of Canadian dollars) | | 2007 | | | 2006 | | | 2005 | |

| | | | | | | | | | | | | |

| Current income tax expense (reversal): | | | | | | | | | | | | |

| Provincial mineral taxes and Crown royalties | | $ | 38.3 | | | $ | 75.5 | | | $ | 58.7 | |

| Canadian corporate income taxes | | | 0.4 | | | | (0.3 | ) | | | 3.9 | |

| | | | | | | | | | |

| | | | 38.7 | | | | 75.2 | | | | 62.6 | |

| | | | | | | | | | | | | |

| Future income tax expense (reversal) : | | | | | | | | | | | | |

| Provincial mineral taxes and Crown royalties | | $ | 2.0 | | | $ | 9.2 | | | $ | 31.3 | |

| Canadian corporate income taxes | | | 71.0 | | | | — | | | | (128.3 | ) |

| | | | | | | | | | |

| | | | 73.0 | | | | 9.2 | | | | (97.0 | ) |

| | | | | | | | | | | | | |

| | | | | | | | | | |

| Total income tax expense (reversal) | | $ | 111.7 | | | $ | 84.4 | | | $ | (34.4 | ) |

| | | | | | | | | | |

Income tax expense includes a provision for British Columbia mineral taxes and Alberta Crown royalties assessed on the cash flows of Elk Valley Coal. Five of Elk Valley Coal’s six mines operate in British Columbia and are subject to British Columbia mineral taxes. Mineral tax is a two-tier tax with a minimum rate of 2% and a maximum rate of 13%. The minimum tax of 2% applies to operating cash flows as defined by regulations. The maximum tax rate of 13% applies to cash flows after taking available deductions for capital expenditures and other permitted deductions. Alberta Crown royalties are assessed on a similar basis, at rates of 1% and 13% and apply to Elk Valley Coal’s Cardinal River operations. The decreases in British Columbia mineral taxes and Alberta Crown royalties from 2006 correspond to the reduction in the taxable cash flows of Elk Valley Coal due primarily to lower sales prices and the effect of the stronger Canadian dollar against the U.S. dollar.

On June 22, 2007, the Federal Government of Canada enacted new legislation that will result in the taxation of income and royalty trusts that were publicly traded as of October 31, 2006, other than certain real estate investment trusts, at effective rates similar to Canadian corporations commencing in 2011. As a result, the Trust recorded a long-term future tax liability and non-cash charges to income tax expense totalling $71 million in 2007.

The future liability for corporate income taxes is based on estimated gross temporary differences of approximately $253 million that are expected to reverse after 2010, which, using an effective tax rate of 28%, results in a future tax liability of $71 million at year end. The temporary differences relate primarily to the difference between the net book value of our capital assets for accounting purposes and their tax basis. The estimates of temporary differences and the timing of their reversal after 2010 are complex and require significant judgment by management. These estimates may change in the future and the future tax liability and income tax expense may fluctuate as a result of changes in these estimates.

CASH AVAILABLE FOR DISTRIBUTION

Under the Declaration of Trust, we make quarterly distributions to unitholders. Distributions for any year must be sufficient to ensure the Trust is not liable for current corporate income taxes. Quarterly distributions are determined in advance of the end of each quarter at the discretion of the Trustees. If it is determined at the end of the taxation year that the distributions declared during the year were insufficient to eliminate our liability for corporate income taxes, then a non-discretionary supplemental distribution will be paid to the unitholders of record on the last day of the fiscal year in an amount sufficient to eliminate the liability. To the extent that cash is not available to pay a distribution sufficient to eliminate the current income tax liability, a distribution would be made in units of the Trust.

17

Cash available for distribution is the term we use to describe the cash generated from our investments during a fiscal period that is available for distribution to unitholders. Cash available for distribution is derived from cash flows from the operations of our subsidiaries, including our proportionate interest in Elk Valley Coal, before changes in non-cash working capital, less sustaining capital expenditures to the extent not funded by debt or equity, principal repayments on debt obligations and any amount allocated to reserves.

Any non-cash working capital related to operations is excluded from the calculation of the cash available for distribution because normal, short-term fluctuations in non-cash working capital are not necessarily indicative of earnings and to include the changes would result in unwarranted volatility of cash available for distribution. Fluctuations in non-cash working capital are financed by available lines of credit of Elk Valley Coal and the Trust, as applicable.

Proceeds under our distribution reinvestment plan are excluded from the calculation of cash available for distribution.

Sustaining capital expenditures refers to our share of Elk Valley Coal’s expenditures in respect of capital asset additions, replacements or improvements required to maintain business operations at current production levels. The determination of what constitutes sustaining capital expenditures requires the judgment of Elk Valley Coal’s management. Sustaining capital expenditures are typically financed from cash flow from operations and are deducted in determining cash available for distribution to Elk Valley Coal’s partners as they are paid in cash. The partnership agreement governing Elk Valley Coal requires the partners to finance their proportionate share of Elk Valley Coal’s sustaining capital expenditures to the extent that the actual expenditures for the year exceed the depreciation deductions that are available to the partners for tax purposes (referred to under Canadian tax laws as “capital cost allowance”) plus certain other tax deductions. The Trust will finance its share of the shortfall using equity or debt financing, such as proceeds from the distribution reinvestment plan or utilization of available bank credit lines.

The timing and amount of capital expenditures incurred by Elk Valley Coal can vary considerably from quarter to quarter and from year to year and will directly affect the amount of cash available for distribution to the Trust’s unitholders. Our cash distributions to unitholders may be reduced, or even eliminated at times, when significant capital expenditures are incurred or other unusual expenditures are made that cannot be funded by other sources.

Establishing cash reserves to meet, for instance, any short-term or long-term need for cash is a discretionary decision of Elk Valley Coal and any reserves would reduce cash available for distribution. Any cash reserves established at the Elk Valley Coal level would have the effect of reducing amounts distributed by Elk Valley Coal to its partners; however, such reserves must be authorized by a special resolution of the partners, and the partnership agreement requires Elk Valley Coal to make reasonable use of its operating lines for working capital purposes.

The Trust has little flexibility to claim certain deductions for income tax purposes due to the nature of the business of Elk Valley Coal and the maturity of its assets. Because the Trust must not be subjected to current income taxes under the Declaration of Trust, we have limited opportunity to establish cash reserves, including reserves aimed at mitigating the impact of fluctuating sustaining capital expenditures and to provide for the settlement of long-lived liabilities. We generally view long-term debt as an integral part of our long-term capital structure. Other long-term liabilities, including future taxes and our share of Elk Valley Coal’s pensions, other post-retirement benefits and asset retirement obligations, are expected to be settled in cash over time. The impact of the settlements, which may be significant, will reduce cash available for distribution as these liabilities are settled, unless the Trust elects to finance them using additional equity or debt, such as proceeds from the distribution reinvestment plan or utilization of available bank credit lines.

18

Cash available for distribution is not a term recognized by GAAP in Canada and it is not a term that has a standardized meaning. Accordingly, cash available for distribution, when used in this management’s discussion and analysis and our other disclosures, may not be comparable with similarly named measures presented by other trusts.

The cash available for distribution from our investments and the distributions made by the Trust in the past three years are set forth in the table below.

| | | | | | | | | | | | | |

| (millions of Canadian dollars) | | 2007 | | | 2006 | | | 2005 | |

| | | | | | | | | | | | | |

| Current year: | | | | | | | | | | | | |

| Cash from operating activities | | $ | 387.1 | | | $ | 690.4 | | | $ | 632.8 | |

| Add (deduct): | | | | | | | | | | $ | | |

| Increase (decrease) in non-cash working capital | | | (17.9 | ) | | | (40.6 | ) | | | 124.3 | |

| Sustaining capital expenditures, net | | | (46.5 | ) | | | (26.0 | ) | | | (38.8 | ) |

| Capital lease payments | | | (1.6 | ) | | $ | (1.8 | ) | | | (2.2 | ) |

| Proceeds from the sale of NYCO, net of taxes paid and payable | | | 30.5 | | | | — | | | | — | |

| Other | | | (2.7 | ) | | | (4.2 | ) | | | 5.5 | |

| Cash reserve | | | — | | | | — | | | | — | |

| | | | | | | | | | |

| | | | | | | | | | | | | |

| Cash available for distribution generated in the year | | | 348.9 | | | | 617.8 | | | | 721.6 | |

| | | | | | | | | | | | | |

| Distributable cash carried forward from prior years | | | 15.7 | | | | 8.1 | | | | (12.9 | ) |

| | | | | | | | | | |

| | | | | | | | | | | | | |

| Distributable cash, including amounts carried forward | | | 364.6 | | | | 625.9 | | | | 708.7 | |

| | | | | | | | | | | | | |

| Distributions declared during the year | | | (358.8 | ) | | | (610.2 | ) | | | (700.6 | ) |

| | | | | | | | | | |

| | | | | | | | | | | | | |

| Distributable cash carried forward to future years | | $ | 5.8 | | | $ | 15.7 | | | $ | 8.1 | |

| | | | | | | | | | |

| | | | | | | | | | | | | |

| Per unit amounts: | | | | | | | | | | | | |

| Cash available for distribution generated in the year | | $ | 2.36 | | | $ | 4.20 | | | $ | 4.91 | |

| Distributions declared | | $ | 2.43 | | | $ | 4.15 | | | $ | 4.76 | |

There are two elements to the sustainability of our distributions: magnitude and longevity. Our investment in a resource business means that our earnings and cash flows will be cyclical in nature. The impact of this cyclicality on cash available for distribution is immediate because of our flow-through structure and any cash reserves aimed at mitigating this variability in distributions may otherwise subject the Trust to current income taxes, which is not permitted. The degree of volatility of cash available for distribution will depend primarily on Elk Valley Coal’s product prices, production and transportation costs, capital expenditure requirements and the capacity to produce and sell product. Elk Valley Coal believes that the global metallurgical coal markets have entered a period of unprecedented volatility and our distributions are expected to fluctuate significantly in the future. The longevity of our ability to generate cash available for distribution is largely dependent upon the life of Elk Valley Coal’s reserves, the continuing relevance of its products in the marketplace and its cost competitiveness over the long term.

The Trust will become subject to corporate income taxes in 2011, which will directly reduce the amount of cash available for distribution beginning at that time.

19

FOURTH QUARTER 2007

Our fourth quarter net income from continuing operations decreased by 57% to $49 million compared with the fourth quarter of 2006 and our income from operations decreased by 71% to $43 million. These reductions were due primarily to lower U.S. dollar prices for the 2007 coal year, which commenced April 1, 2007, and the effects of the stronger Canadian dollar relative to the U.S. dollar in 2007.

Other items impacting net income from continuing operations in the fourth quarter were the decrease of $37 million in the unrealized gains on our foreign exchange forward contracts, which resulted from the maturity of contracts and realization of $44 million of gains during the quarter, and non-cash future income tax reversals of $11 million, which related primarily to a legislated reduction in the corporate income tax rates that will apply to the Trust beginning in 2011.

Net income from continuing operations before unusual items, future income taxes and unrealized gains or losses on foreign exchange forward contracts was $75 million in the fourth quarter compared with $116 million in the fourth quarter of 2006 and primarily reflects lower U.S. dollar coal prices for the 2007 coal year and a stronger Canadian dollar.

Cash available for distribution from our investments in the quarter was $75 million ($0.50 per unit) compared with $147 million ($1.00 per unit) in the fourth quarter of 2006. Distributions declared for the quarter were $0.53 per unit compared with $0.95 per unit for the fourth quarter of 2006.

Operations

Revenues for the quarter decreased by $97 million, or 23%, compared with the fourth quarter of 2006. Coal sales volumes of 3.6 million tonnes (Trust’s share) for the quarter were slightly higher than in the fourth quarter of 2006. Average U.S. dollar coal prices for the quarter decreased by 13% to US$92.70 per tonne as a result of lower prices for the 2007 coal year. The average realized Canadian dollar coal price decreased by 25% to $91.50 per tonne for the quarter.

Elk Valley Coal’s unit cost of product sold increased by 10% to $40.00 per tonne for the fourth quarter of 2007 compared with $36.40 per tonne in the fourth quarter of 2006. This was due primarily to a sharp increase in diesel fuel costs as well as higher costs for contractor services, tires and other consumables. Production levels, strip ratios and haul distances in the fourth quarter of 2007 were similar to those in the fourth quarter of 2006.

Unit transportation costs decreased by 10% to $33.00 per tonne compared with $36.80 in the fourth quarter of 2006. Lower unit transportation costs for the quarter were due primarily to lower average selling prices. Certain of Elk Valley Coal’s rail and port costs are tied to its average selling prices. The benefit of lower rail and port costs was partially offset by an increase in vessel demurrage costs due to longer vessel wait times and higher demurrage rates. Port inventories were at low levels during 2007 due to shortfalls in rail shipments. This has resulted in longer vessel wait times and increased demurrage costs.

2006 COMPARED WITH 2005

Operations

Revenues

Coal sales revenues of $1.8 billion in 2006 decreased by 2% from the prior year. The effects of lower sales volumes and a stronger Canadian dollar were partially offset by higher average calendar-year coal sales prices. Elk Valley Coal’s U.S. dollar price of coal on a calendar-year basis increased 14% over 2005. Prices in Canadian dollar terms increased 5% and reflected the stronger Canadian dollar during 2006. Some of the impact of the stronger Canadian dollar was offset by gains on the settlement of foreign exchange forward contracts of $59 million recorded in 2006.

20

Coal sales volumes declined by 6% to 13.6 million tonnes from 14.5 million tonnes in 2005. Factors that depressed sales volumes in 2006 included increased substitution of lower-priced, lower-quality coking coals by some integrated steel mills to reduce consumption of hard coking coal and an increased supply of hard coking coal from producers in Australia and Canada.

Cost of Product Sold

Cost of product sold increased $63 million, or 13%, over 2005 levels, despite lower sales volumes. The unit cost of product sold increased 21% or $6.80 per tonne. Rising costs for many mining inputs provided upward pressure to cost of product sold in 2006. Labour costs increased because of the settlements of long-term union labour agreements, which included one-time costs and signing bonuses, at a number of mines during the year in a highly competitive labour environment. High activity levels in the mining industry worldwide had an impact on costs. Consumables, such as tires, fuel, repairs and services, increased for a number of reasons including shortages, higher crude prices and higher inflation. Production levels in 2006 were 15% lower compared with 2005 in order to manage inventory levels in response to lower sales. Lower production increased the fixed costs per tonne of coal produced and sold, and adversely affected the efficiency of mining operations. Also contributing to increased costs were higher strip ratios and longer haul distances. Strip ratios increased overall as a result of normal variations of geology and, to a lesser extent, yield at the mines.

Total material and clean coal productivities decreased by 8% and 12% in 2006, respectively. This largely reflects lower production levels compared with 2005, as well as higher strip ratios and slightly lower plant yield.

Transportation Costs

Transportation costs were down $10 million, or 2%, in 2006. The impact of lower sales volumes in 2006 was largely offset by higher rail and port rates. Rail rates increased in 2006, particularly for westbound shipments from the mines in the Elk Valley. In April 2005, Elk Valley Coal and Canadian Pacific reached a five-year agreement for westbound rail rates and volumes effective April 1, 2004 to March 31, 2009 for transportation of coal from the mines in the Elk Valley to the west-coast ports.

Other Income and Expenses

Interest expense increased in 2006 compared with 2005 primarily because of higher debt levels. Long-term debt increased approximately $100 million during 2006 in order to refinance capital additions in 2004 and 2005 that were initially funded in part by working capital.

Other items in 2006 included a $32 million charge to earnings to reflect a new accounting standard for in-process inventory. In 2005, other items included a $27 million gain on the sale of limited partnership interests in the Elkview operations to two of Elk Valley Coal’s customers.

Income Taxes

Mineral taxes were $85 million in 2006 compared with $90 million in 2005 and were consistent with the decrease in taxable cash flows generated by Elk Valley Coal. Mineral taxes in 2006 included additional expense arising from assessments of prior years’ returns. We also recognized a future tax asset of $13 million in 2006, of which $9 million was taken as a reduction in goodwill to reflect certain future tax assets not recognized upon the formation of the Trust.

21

The future income tax reversal in 2005 includes the reversal of a $164 million provision for future Canadian corporate income taxes following the 2005 Arrangement.

SUMMARY OF QUARTERLY RESULTS

Our quarterly results over the past two years reflect the variability of Elk Valley Coal’s business. Net income also includes the significant impact of a number of unusual transactions and events. Net income before unusual items, future income taxes and unrealized gains or losses on foreign exchange forward contracts is influenced largely by coal prices, the U.S./Canadian dollar exchange rate, coal sales volumes, unit cost of product sold and unit transportation costs.

| | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | |

| Coal statistics | | 2007 | | | 2006 | |

| (Trust's 60% Share) | | Q4 | | | Q3 | | | Q2 | | | Q1 | | | Q4 | | | Q3 | | | Q2 | | | Q1 | |

| | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | |

Production(million of tonnes) | | | 3.3 | | | | 3.4 | | | | 3.7 | | | | 3.1 | | | | 3.3 | | | | 3.0 | | | | 3.3 | | | | 3.5 | |

Sales(millions of tonnes) | | | 3.6 | | | | 3.4 | | | | 3.8 | | | | 2.8 | | | | 3.5 | | | | 3.5 | | | | 3.5 | | | | 3.1 | |

| Average US$prices (per tonne) | | $ | 92.70 | | | $ | 93.20 | | | $ | 100.70 | | | $ | 105.40 | | | $ | 106.30 | | | $ | 108.80 | | | $ | 116.10 | | | $ | 122.30 | |

| Average CDN$prices (per tonne) | | $ | 91.50 | | | $ | 97.30 | | | $ | 110.90 | | | $ | 123.50 | | | $ | 122.60 | | | $ | 124.40 | | | $ | 133.00 | | | $ | 152.30 | |

Cost of product sold (per tonne) | | $ | 40.00 | | | $ | 41.00 | | | $ | 39.50 | | | $ | 45.80 | | | $ | 36.40 | | | $ | 42.60 | | | $ | 39.20 | | | $ | 38.60 | |