Exhibit D

FEDERATIVE REPUBLIC OF BRAZIL

This description of the Federative Republic of Brazil (“Brazil” or the “Republic”) is dated as of September 14, 2010 and appears as Exhibit D to the Republic’s Annual Report on Form 18-K to the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission for the fiscal year ended December 31, 2009.

Until the introduction of the real in July 1994, Brazil had experienced high rates of inflation. A variety of indices exist for measuring inflation in Brazil. This document uses the General Price Index-Domestic Supply (Índice Geral de Preços-Disponibilidade Interna, or “IGP-DI”), a national price index based on a weighting of three other indices, the Wholesale Price Index-Domestic Supply (Índice de Preços por Atacado-Disponibilidade Interna, or “IPA-DI”) (60%), the Consumer Price Index (Índice de Preços ao Consumidor) (30%), and the National Index of Building Costs (Índice Nacional de Custos de Construção, or “INCC”) (10%). The IGP-DI, one of the most widely used inflation indices, is calculated by the Getúlio Vargas Foundation, an independent research organization. See “The Brazilian Economy—Prices”. As measured by the IGP-DI, the annual rate of inflation in Brazil was 1.2% in 2005, 3.8% in 2006, 7.9% in 2007, 9.1% in 2008 and -1.4% in 2009. Such levels of inflation, together with the fluctuation of the Brazilian currency in relation to the U.S. dollar, should be considered by the readers of all financial and statistical information contained herein.

The following table sets forth certain exchange rate information reported by the Central Bank for the selling of U.S. dollars, expressed in nominal reais, for the periods indicated. The Federal Reserve Bank of New York does not report a noon buying rate for the real.

Table No. 1

Commercial Exchange Rates (Selling Side)

R$/$1.00

| | | | | | | |

Year | | Average for

Period(1) | | End of

Period | | Percentage

Change

(End of

Period) | |

2005 | | 2.4341 | | 2.3407 | | (11.8 | ) |

2006 | | 2.1771 | | 2.1380 | | (8.7 | ) |

2007 | | 1.9483 | | 1.7713 | | (17.2 | ) |

2008 | | 1.8375 | | 2.3370 | | 31.9 | |

2009 | | 1.9935 | | 1.7412 | | (25.5 | ) |

| (1) | Weighted average of the exchange rates on business days during the period. |

Source: Central Bank.

In January 1999, the Central Bank abandoned its exchange band mechanism, which encouraged small exchange devaluations within a specified range and which had been in effect since March 1995, and permitted the value of the real to

D-1

float freely against that of the dollar. On December 31, 2009, the real-U.S. dollar exchange rate (sell side) in the commercial exchange market, as published by the Central Bank, was R$1.7412 to $1.00 while on December 31, 2008 it was R$2.3370 to $1.00. See “Balance of Payments and Foreign Trade—Foreign Exchange Rates and Exchange Controls”. In this report, references to “dollars”, “U.S. dollars”, “U.S.$” and “$” are to United States dollars, and references to “real“, “reais“ and “R$” are to Brazilian reais. The fiscal year of the federal Government of Brazil (the “Federal Government”) ends December 31 of each year. The fiscal year ended December 31, 2009 is referred to herein as “2009”, and other years are referred to in a similar manner. Tables herein may not add due to rounding.

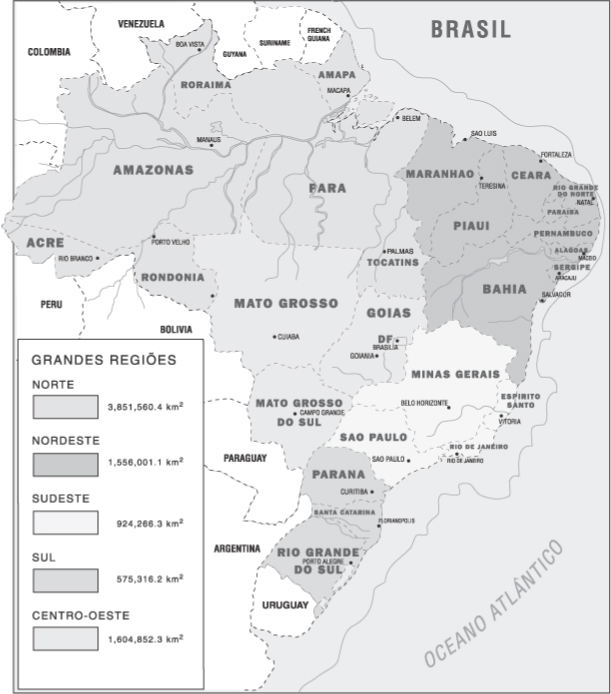

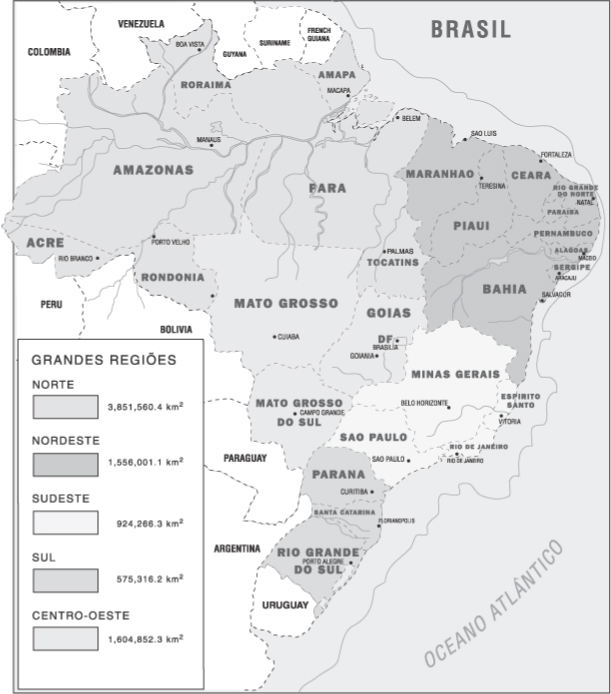

MAP OF BRAZIL

D-2

INTRODUCTION

Brazil is the fifth largest country in the world and occupies nearly half the land area of South America. Brazil shares a border with every country in South America except Chile and Ecuador. The capital of Brazil is Brasília, and the official language is Portuguese. On December 31, 2009, Brazil’s estimated population was 191.4 million.

Following two decades of military governments, in 1985 Brazil made a successful transition to civilian authority and democratic government. A new Brazilian Constitution (the Constituição da República Federativa do Brasil, or “Constitution”) was adopted in 1988. In 1989, direct presidential elections were held for the first time in 29 years. After winning a runoff election with 61% of the vote on October 27, 2002, Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva assumed the presidency of Brazil on January 1, 2003, and was re-elected in October 2006 for a second term ending in 2010, after winning a runoff election with 60.8% of the votes.

Mr. da Silva is a member of the Workers’ Party (Partido dos Trabalhadores, or “PT”). Following the October 2002 elections, Mr. da Silva’s party held 17.5% of the seats in the Chamber of Deputies and 12.3% of the seats in the Senate. Mr. da Silva was elected as part of a broad coalition consisting of the Liberal Party (Partido Liberal) and five smaller parties, including the Brazilian Socialist Party (Partido Socialista Brasileiro, or “PSB”) and the Brazilian Workers Party (Partido Trabalhista Brasileiro, or “PTB”). In 2003 and 2004, the PT formed new alliances with the Brazilian Democratic Movement Party (Partido do Movimento Democrático Brasileiro, or “PMDB”) and the Brazilian Progressive Party (Partido Progressista, or “PP”) and with other, small parties. As a result of these alliances, Mr. da Silva’s coalition grew to 73% of the members of the Chamber of Deputies and to 57% of the members of the Senate. Following the outcome of the general elections held in October 2006, President da Silva’s coalition consisted of 11 parties (PMDB, PT, PP, PSB, the Democratic Labor Party (Partido Democrático Trabalhista, or “PDT”), the Republic Party (Partido da República, or “PR”), PTB, the Communist Party of Brazil (Partido Comunista do Brasil, or “PCdoB”), the Green Party (Partido Verde, or “PV”), the Social Christian Party (Partido Social Cristão, or “PSC”) and the Brazilian Republican Party (Partido Republicano Brasileiro)), representing 72% of the seats in the Chamber of Deputies and 62% of the seats in the Senate. During President da Silva’s administration, several Parliamentary Commissions of Inquiry (CPI) were created in Congress to investigate corruption cases involving members of the Federal Government. In 2005, a corruption complaint garnered attention in the press: a member of the allied base of President da Silva said that several congressmen received bribes for voting in favor of the interests of the Government (bribery that became known as the “monthly allowance”). The complaint resulted in the resignation of the President’s Chief of Staff, Jose Dirceu, and several other lawsuits against members that were allegedly involved in the corruption are still pending in court.As President, Mr. da Silva has initiated a series of social programs, including a “Zero Hunger” campaign, which is intended to eradicate famine and address poverty in the Republic; a “Bolsa Família” program that provides assistance to impoverished families; and a “First Job” program aimed at facilitating the entry of young people into the labor market. He has also secured reforms of the tax, pension and judicial systems, instituted a framework for public-private partnerships, introduced a regulatory framework for investment in the electricity sector, among other sectors, and secured amendments to the country’s bankruptcy law. Finally, the da Silva administration’s economic policy has been characterized by fiscal discipline, a floating exchange rate and inflation targeting. Among the da Silva administration’s first initiatives was an increase in the consolidated public sector primary surplus target, which increased from 3.75% of real gross domestic product (Produto Interno Bruto, or “GDP”) in 2002 to 4.25% of GDP in each of 2003, 2005, 2006 and 2007. The Federal Government raised the target from 4.25% to 4.5% in 2004, due to better than expected fiscal revenues. In 2008, the primary surplus reached 4.1% of GDP. For 2009, the primary surplus target was initially set at 3.8% and after adjusted to 2.5%. The primary surplus of 2009 was 2.1% of GDP, but the target was achieved when the government discounted part of the PAC investments (0.4% of GDP) in its expenditures.

Mr. da Silva succeeded in enacting certain pension reforms, which Brazil’s Chamber of Deputies and Senate approved. On December 19, 2003, the rules related to retirement and social security for civil servants were further modified by Constitutional Amendment No. 41. On July 5, 2005, the National Congress approved Constitutional Amendment No. 47, which modifies Constitutional Amendment No. 41 as it applies to civil servants. The adjustments include: (i) an increase in the minimum retirement age for civil servants from 48 to 55 years for women and from 53 to 60 years for men; (ii) a reduction of 30% in pensions paid for widows and orphans of civil servants in excess of the ceiling for retirement payments under the general social security system per month; (iii) a contribution to the social security system by retired civil servants of 11% of the amount by which the retired employee’s pension exceeds 60% of the above-mentioned ceiling in the case of federal retirees and 50% of the above-mentioned ceiling in the case of all other retired civil servants; (iv) a uniform contribution level for municipal, State and federal workers consisting of at least 11% of the amount of the employee’s salary; and (v) the institution of a complementary regime for new civil servants, which will require the passage of ordinary legislation. For the

D-3

private sector pension system (the general social security system), the cap on social security pensions paid to private sector retirees was raised from R$1,561.56 to R$3,467.40. The amounts used as reference are revised every year. See “The Brazilian Economy—Constitutional Reform” and “—Social Security”.

Mr. da Silva was also able to enact certain tax reforms. On December 19, 2003, the Chamber of Deputies and the Senate approved an amended tax reform bill in the form of Constitutional Amendment No. 42. Constitutional Amendment No. 42 provides for, among other items: (i) the Delinking of Central Government Revenues (Desvinculação de Recursos da União, or “DRU”), which permits the reallocation of 20% of certain tax revenues that the Federal Government would otherwise be required to devote to specific program areas under the Constitution; (ii) the exempting of exports from the tax on the circulation of goods and services (Imposto sobre Circulação de Mercadoria e Serviços, or “ICMS”) and the establishment of a fund to compensate States for lost ICMS revenue resulting from that exemption; (iii) the imposition of the contribution for the financing of social security (Contribuição para o Fianciamento da Seguridade Social, or “COFINS”) only at the final stage of the production process, rather than at each stage of that process; (iv) a reduction of the tax on industrial products (Imposto sobre Produtos Industrializados, or “IPI”) on imports of capital goods; and (v) a requirement that the Federal Government transfer to States and municipalities 25% of the revenues from the Contribution on the Intervention in the Economic Domain (Contribuição de Intervenção no Domínio Econômico, or “CIDE”). On December 12, 2007, the Brazilian Congress failed to pass a constitutional amendment that would have extended the provisional financial contribution levy (Contribuição Provisória sobre a Movimentação Financeira, or “CPMF”). The Brazilian Congress did, however, agree to extend the DRU until 2011. In January 2008, the Federal Government announced a fiscal package to compensate for the revenue loss expected from the CPMF withdrawal. The package included a reduction in the federal budget and an increase in revenue from higher taxes on foreign exchange and credit card operations and an increase in the Social Contribution on Net Profits (Contribuição Social sobre o Lucro Líquido, or “CSLL”) for financial institutions.

During the second year of his first term, Mr. da Silva was able to enact certain judicial reforms. In November 2004, Congress approved Constitutional Amendment No. 45, dated December 8, 2004, a set of reforms intended to improve the efficiency of the judicial system. Constitutional Amendment No. 45, among other things, amends Articles 102 and 105 of the Constitution to provide that the Superior Court of Justice (Superior Tribunal de Justiça, or “STJ”), and not the Federal Supreme Court (Supremo Tribunal Federal, or “STF”), is to determine whether foreign judgments and foreign arbitral awards are enforceable in Brazil. The enforcement by a Brazilian court of a foreign arbitral award is subject to the recognition of such award by the STJ. The STJ will recognize such an award if all of the required formalities are observed and the award does not contravene Brazilian national sovereignty, public policy and “good morals”.

Other reforms introduced by Constitutional Amendment No. 45 include: (i) the right of all parties to a judicial process of reasonable duration and to the means necessary to attain it; (ii) the submission by Brazil to the jurisdiction of the International Criminal Court, the governing statute of which was ratified by Brazil in June 2002; (iii) a provision barring a retired or removed judge from practicing, for a period of three years, before the court in which he or she sat; (iv) a rule providing that decisions of the Federal Supreme Court on the merits of lawsuits challenging the constitutionality of certain acts (ações diretas de inconstitucionalidade and ações declaratórias de constitucionalidade) constitute binding precedents for the lower courts, government bodies directly linked to federal, State or municipal powers and entities created to perform government activities in a decentralized manner; (v) a rule providing that the Federal Supreme Court may issue summary legal principles (súmulas) that are binding on the lower courts and the direct and indirect administration; (vi) the establishment of a fifteen-member National Council of Justice (Conselho Nacional de Justiça) to oversee the administrative and fiscal management of the judiciary; and (vii) the establishment of a fourteen-member National Council of the Public Ministry (Conselho Nacional do Ministério Público) to oversee the administrative and fiscal management of the public prosecution service.

On February 9, 2005, President da Silva sanctioned a bankruptcy law that had been under consideration by the Congress for ten years, as well as changes to the tax code. The new bankruptcy law, Law No. 11,101, among other things, (i) places a cap equal to 150 times the minimum monthly salary on claims in bankruptcy proceedings by employees for such items as unpaid wages, unused vacation time and implements a 40% penalty for unjust dismissals; (ii) gives secured creditors priority over tax claims in bankruptcy proceedings; and (iii) ends a “succession” doctrine that makes a purchaser of assets from a bankrupt company or from a company under judicial reorganization responsible for certain of the insolvent company’s tax and social security obligations as a consequence of the acquisition, and, in the case of a company under bankruptcy proceedings, the debtor’s labor claims. The Federal Government expects the measure to reduce interest rates charged by financial institutions for domestic loans.

Law No. 11,187 dated October 19, 2005, introduced further reforms by amending Brazil’s Civil Procedure Code to limit interlocutory appeals (agravos). In December 2006, Law No. 11,417 sanctioned the binding clause—the mechanism which

D-4

obligates lower court judges to follow decisions adopted by the STF. As a result, lower court judges are required to follow STF precedents, which may reduce the amount of appeals and expedite court decisions. In addition, two other laws regarding courts reform were sanctioned during the same month of 2006: Law No. 11,418 dated December 19, 2006, which limits the analysis of appeals by STF to general pertinent questions considered relevant to society as a whole and Law No. 11,419 dated December 19, 2006, which provides for the digitalization of the judicial process, thereby allowing judges in all of Brazil to work with electronic documents in order to expedite the judicial process.

In June 2006, the Law of Civil Execution (Law No. 11,232/05 of December 22, 2005) was enacted. It defines new procedures to expedite debt judgments. Pursuant to this Law, after the judge’s decision, the debtor will be required to pay the outstanding debt in 15 days. In the case of non-payment there will be a penalty of 10% of the amount due. Pursuant to this Law, the debtor also shall not auction its assets in order to avoid its debts and the automatic stay against the execution of the judgment has been eliminated.

Law No. 11,382, sanctioned in December 2006 and relating to extra-judiciary bank certificates execution, may expedite debt judgments in the Republic and favors banking spread reductions and more credit concessions. The legislation permits the petitioner to obtain a certificate in order to block the debtor’s physical goods (vehicles, real estate) from being sold before the debt payment. The distraint system is utilized and the debtor’s goods are impounded in order to guarantee a debt payment and sold if payment does not occur. Evaluation of physical goods is done by the judicial officer and the transfer of goods from the debtor to the creditor has priority in such evaluation. The debt may be paid in installments by the debtor if it recognizes its debts and has previously made a deposit of 30% of the total value of the debt.

Changes have also been made to improve the investment climate. On December 30, 2004, President da Silva sanctioned Law No. 11,079, which provides for the formation of two types of “public-private partnerships” (Parceiras Público-Privadas or “PPP”): (i) contracts for concessions of public works or utility services under which private party concessionaires receive payments from a public sector entity in addition to tariffs charged to end-users and (ii) contracts for rendering of services under which a public sector entity is the end-user. PPP contracts must be worth at least R$20 million and provide for a service period of between five and 35 years, including extensions of the term. All such contracts can only be awarded through a public bidding process. Because the concessionaires will only begin to receive payments when the services under the PPP contract are provided, the private parties will have to obtain private financing for the construction of the facility that is to provide the services under the contract. Law No. 11,079 permits payments from the public sector entity to be made directly to the contractor’s creditors, thereby reducing the creditors’ overall credit risk. The federal PPP program is overseen by a management committee appointed by the Ministry of Planning, Budget and Management, the Ministry of Finance and the Office of the Chief of Staff (Casa Civil da Presidência da República). The management committee is charged with selecting the projects for and regulating the federal PPP program. See “The Brazilian Economy—Incentives for Private Investment”.

Measures are also being taken to facilitate the access of foreign investors to domestic financial markets. In November 2005, the Federal Government simplified the process for the registration of securities with the Brazilian Securities Commission (Comissão de Valores Mobiliários or “CVM”) and of the generation of the CNPJ number, two necessary steps to allow foreign investors to operate in the domestic markets.

Law No. 11,312, dated June 27, 2006, exempts foreign investors from a withholding tax on trading in Brazilian government bonds. The exemption is limited to investment funds that have at least 98% of their assets invested in Brazilian government bonds and in which all of the investors are nonresidents of Brazil. The exemption does not apply to repurchase transactions or to investors that are resident in countries that have no capital gains taxes or that impose such a tax at a rate lower than 20%. The exemption is intended to increase the demand for Brazilian government bonds and reduce Brazil’s borrowing costs. On January 22, 2007, the Federal Government unveiled the Growth Acceleration Plan 2007-2010, a set of measures seeking to: (i) create incentives for private investment; (ii) increase public investment in infrastructure; and (iii) remove bureaucratic, administrative, normative, legal and legislative obstacles to growth. The measures are grouped under five broad headings: infrastructure investment, stimulus to credit and financing, improvement in the investment climate, tax exemptions and improvements in the tax system, and long-term fiscal measures. In the infrastructure area, the PAC projects investments of R$504 billion in the period 2007-2010, of which R$436 billion would come from state-owned companies and from the private sector. The Federal Government presented, on March 29, 2010, the second phase of the Growth Acceleration Program (PAC 2). The preliminary estimate of investments in PAC 2 projects is approximately R$ 1.5 trillion. See “The Brazilian Economy—Incentives for Private Investment”.

In order to stimulate economic activity and increase liquidity to minimize the effects of the international crises, the Federal Government implemented expansionary fiscal and monetary policies, as well as other measures since September 2008. Among the instruments used are the following: a package of tax reductions, increases in PAC resources, creation of a housing

D-5

program (“Minha casa, Minha Vida”, or “My House, My Life”), creation of a credit line for agriculture, reduction of reserve requirements for Brazilian banks, a series of reductions of the Selic rate, sales of foreign exchange swaps, rescues of certain banks by the Central Bank and currency swap operations with central banks of others countries.

On October 6, 2008, Provisional Measure No. 442, (subsequently enacted as Law No. 11,882 of December 23, 2008), authorized the Central Bank to rescue banks with special operations of rediscount and with guarantees of loans in foreign currency. Pursuant to such Provisional Measure, the Central Bank was also allowed to authorize the issue of leasing credit securities by financial institutions. On October 21, 2008, Provisional Measure No. 443 (enacted as Law No. 11,908, of March 3, 2009) authorized Banco do Brasil and CEF to form subsidiaries and acquire interests in financial institutions. It also authorized the creation of an investment bank called Caixa Banco de Investimento S.A., which is an integral subsidiary of the CEF, with the objective of exploring investment bank activities and other operations as provided in the applicable legislation.

To ease the lack of liquidity in the international market, Resolution No. 3,631, dated October 30, 2008, regulated a swap line of currencies between the Central Bank and the Federal Reserve Bank of New York. This swap line expired on February 2010. Also with the objective of overcoming a shortage of liquidity, the Central Bank issued CMN Resolution No. 3,672, on December 12, 2008 and Circular No. 3,434, on February 4, 2009. These measures established criteria and special conditions for loans in foreign currency, which allowed the Central Bank to guarantee on behalf of Brazilian companies the payments of offshore loans with payments due in 2008 and 2009.

The Provisional Measure No. 464 of June 9, 2009 (converted to Law No. 12,087 of November 11, 2009), provided financial assistance by the Republic to States, Federal District and Municipalities, in the year of 2009, with the objective of promoting the country’s exports. It also allowed the Republic to participate in the Credit Guarantor Fund (Fundo Garantidor de Créditos, or “FGC”) for small and medium enterprises.

On October 30, 2008, the Central Bank published Resolution No. 3,629, which permitted Brazilian banks to use up to 5% of the total balance of their savings deposits to provide financing for construction companies in the form of credit lines for working capital until March 31, 2009. On November 13, 2008, the Central Bank published Resolution 3,635, allowing the (Caixa Econômica Federal, or “CEF”) to provide working capital financing earmarked for civil construction in a total amount of up to R$3 billion, with the exclusive purpose of giving an additional guarantee and reducing the perception of risk associated with such operations. The Advisory Board of the Time-in-Service Guarantee Fund (Fundo de Garantia do Tempo de Servico, or “FGTS”) also approved, on December 2, 2008, a credit line of R$3 billion for construction companies in 2009.

There were also other more specific sector measures designed to stimulate economic activity. Resolution No. 3,628, October 30, 2008, authorized the utilization of new credit operations in the amount of R$8 billion earmarked for Petrobrás, a Brazilian oil company. To aid the naval construction industry, the Federal Government announced the provision of R$10 billion from the Merchant Marine Fund (FMM) and suspended of the payment of the IPI by Decree No. 6,704 of December 19, 2008. The agricultural sector benefited from a credit line of R$12.6 billion, created with resources of BNDES. These funds were earmarked to provide financing for the storage of alcohol, farming and working capital.

In addition, the Federal Government implemented measures concerning foreign trade. It provided R$10 billion to BNDES to finance lines of credit for the pre-shipment of exports and to increase working capital of enterprises. As a result, BNDES reduced the cost of credit lines available for capital goods purchases until the end of 2009. It also managed interest rates to improve credit access for micro, small and medium enterprises.

On October 30, 2008, the Advisory Board of the FGTS approved the acquisition of up to R$7 billion in debentures issued by BNDES. On December 1, 2008, BNDES created a new credit line for the financing of the working capital of Brazilian companies, the Special Program of Credit – PEC, with a budgetary endowment of R$6 billion valid until June 30, 2009. Art. 15 of Provisional Measure No. 450 (subsequently enacted as Law No. 11,943 of May 28, 2009) of December 9, 2008, authorized the Republic to transfer up to US$2 billion obtained from the World Bank (“IBRD”), to BNDES by means of credit operations. Through Provisional Measure No. 453 of January 22, 2009 (subsequently enacted as Law No. 11,948 of June 16, 2009), the Republic was authorized to grant credit to BNDES, in an amount of up to R$100 billion. Previously, Provisional Measure No. 439 of August 29, 2008 (subsequently enacted as Law 11,805 of November 6, 2008), had already authorized the Republic to grant credit to BNDES in the maximum amount of R$15 billion. Law No. 11,948 was amended by Provisional Measure No. 472 of December 15, 2009, which increased the credit limit by $180 billion to BNDES. The last tranche of this loan from the Treasury to BNDES was transferred on May 4, 2010.

D-6

Law No. 11,887, dated December 24, 2008, created the Brazil Sovereign Fund (Fundo Soberano Brasileiro, or “FSB”), an anti-cyclical mechanism, the objective of which was to promote investments in assets in Brazil and abroad, create public savings, minimize the effects of the economic and financial crises, as well as promote projects of strategic interest to Brazil. To complement the FSB, on the same day, Provisional Measure No. 452 was amended and authorized Brazil to issue treasury bonds to establish the FSB. As of May 2010, the FSB was valued at R$17.1 billion, or approximately 0.5% of GDP. Provisional Measure No. 452 was not approved by Congress and lost its validity on June 1, 2009 – there was no need to issue a new measure to further the FSB.

On April 23, 2010 the Federal Government issued Provisional measure No. 487, which among other things, allows the use of the Brazilian Sovereign Fund for the capitalization of State enterprises. This measure also created certain facilities for managing state assets, allowing the exchange of shares of public and private enterprises that are in the portfolio of the Treasury and of the State owned enterprises.

In early 2009, with the objective of reducing dollar demand, the Central Bank issued Resolution No. 3.675 of January 29, 2009, which allowed companies to extend the period of export foreign-exchange contracts by approximately 360 days, until January 31, 2010. On February 5, 2009, the Central Bank issued Circular No. 18,040, reestablishing procedures for the use of resources from international reserves in order to finance the restructuring by Brazilian companies of their offshore debt.

On March 4, 2009, the Central Bank, through Resolution No. 3,689, gave Brazilian financial institutions access to the U.S. dollars in the international reserves to pay and refinance debt with their offshore subsidiaries. In addition, on March 25, 2009, the Central Bank launched U.S. dollar auctions backed by reserves to loosen the export market, financing long positions in foreign exchange. On March 25, 2009, the Government created the program “My House, My Life”, through Provisional Measure No. 459 (subsequently enacted as Law No. 11,977 of July 7, 2009), with the objective of building one million houses for low income families. This program will have resources of up to R$60 billion, of which R$34 billion will be provided through subsidies from the Federal Government and BNDES, and R$26 billion originating from FGTS financing.

On March 30, 2009, as a result of the increase in job losses registered in the months preceding March 2009, the Board of the Workers’ Support Fund (Fundo de Amparo ao Trabalhador, or “FAT”) enacted Resolution No. 595 extending from five to seven months the payment of unemployment insurance benefits for workers of certain sub-sectors of activity most affected by the global crisis.

Most of the measures enacted to tackle the crises are being phased out in 2010. For instance, on February 24, 2010, The Central Bank of Brazil announced a set of measures withdrawing anti-crisis measures adopted since October 2008. Amongst these measures are the changes in the reserve requirement (restoring the rate of 15%) and an increase in the additional reserve requirement for banks’ time deposits and demand deposits (reestablishing the rate of 8%). Another example is the end of the IPI tax relieve for cars, which ended on March 31, 2010.

During the period from 1982 until the implementation of Brazil’s external debt restructuring in 1994, Brazil failed to make payments on certain of its external indebtedness from commercial banks as originally scheduled, and in February 1987 declared a moratorium on principal and interest payments on external indebtedness to commercial banks. Brazil’s external indebtedness to commercial banks was restructured in a Brady Plan restructuring in April 1994. See “Public Debt—Debt Crisis and Restructuring”. Throughout the debt restructuring process, the Republic continued to make principal and interest payments on its external bonded indebtedness in accordance with the terms of such indebtedness. See “Public Debt—Debt Record”.

Prior to the introduction of the real as Brazil’s official currency in July 1994 pursuant to the Plano Real, Brazil’s economic performance had been characterized by macroeconomic instability, including extremely high rates of inflation and significant and sudden currency devaluations. Pre-Plano Real stabilization efforts, which included wage and price controls, failed to contain inflation for any extended period. See “The Brazilian Economy—Historical Background”. The Plano Real, which the Federal Government announced in December 1993 and fully implemented in July 1994, succeeded in lowering inflation from an annual rate of 2,708.4% in 1993 and 909.6% in 1994 to 14.8% in 1995, 9.3% in 1996, 7.5% in 1997 and 1.7% in 1998, as measured by the IGP-DI. The inflation rate increased to 20.0% in 1999, however, following the decision of the Central Bank in January 1999 to permit the value of the real to float against that of the dollar. The inflation rate subsequently declined as a consequence of the implementation of the inflation targeting regime by the Central Bank in June 1999, registering 9.8% in 2000 and 10.4% in 2001. See “The Brazilian Economy—Prices”.

D-7

The real reached R$2.8892 to $1.00 on December 31, 2003, R$2.6544 on December 31, 2004, R$2.3407 on December 31, 2005 and R$2.1380 on December 31, 2006. Because of the current international financial crisis, the real depreciated significantly and reached R$2.337 to $1.00 on December 31, 2008. Nevertheless, in 2009, the real recovered against the U.S. dollar and stood at R$1.7420 per $1.00 on December 31, 2009. See “Balance of Payments and Foreign Trade—Foreign Exchange Rates and Exchange Controls”.

Noting that the inflation rate as measured by the broad consumer rate index Consumer Amplified Price Index (Índice de Preços ao Consumidor Amplo, or “IPCA”) was likely to meet its target of 5.5% for 2004 and 4.5% for 2005 (with tolerance levels of plus or minus 2.5 percentage points), the Central Bank reduced its Over/Selic interest rate target from 26.5% on May 21, 2003 to 16.0% on April 14, 2004. However, in an effort to manage inflationary expectations, the Central Bank increased its Over/Selic rate target from September 2004 to May 18, 2005, reaching 19.75%. The Central Bank gradually reduced its Over/Selic rate target from 19.5% on September 14, 2005 to 11.25% on September 5, 2007, but to manage renewed inflationary expectations resulting from accelerated growth, the Central Bank increased its Over/Selic rate target to 11.75% on April 16, 2008, to 12.25% on June 4, 2008, to 13.00% on July 23 and to 13.75% on September 10, 2008. The 13.75% rate target was maintained until the end of 2008, when the Central Bank began an easing of monetary policy due in part to the international financial crisis and its effects on the domestic economy. The policy was implemented on January 21, 2009 with the reduction of the Over/Selic target rate to 12.75%. The rate was further reduced to 11.25% on March 11, 2009, 10.25% on April 29, 2009 and 9.25% on June 10, 2009. The last reduction was on July 22, 2009, when the Over/Selic rate was reduced to 8.75%. After ten months of reductions, the Over/Selic was increased to 9.50% on April 28, 2010, to 10.25% on June 6, 2010 and to 10.75% on July 21, 2010.

On March 21, 2007, the IBGE, concluding a two-year effort to improve Brazil’s National Accounts System, revised its methodology for calculating GDP and restated its historic GDP data dating back to 1995. Under the new methodology, a broader range of sources of information is used to provide a more accurate measure of Brazil’s GDP. Sources such as IBGE’s annual survey of economic segments, tax receipts information and household surveys are utilized to calculate GDP. As a result, activities that were previously estimated under the prior methodology, such as government consumption and financial intermediation, are now actually measured. In addition, the relative weights of economic activities were adjusted to give greater importance to services such as telecommunications and transportation.

Brazil’s real and nominal GDP growth for the years 2000 through 2005 was revised upward. As reported by the IBGE, GDP increased 4.0% from 2005 to 2006, 5.7% from 2006 to 2007 and 5.1% from 2007 to 2008. GDP decreased 0.2% from 2008 to 2009. Production in the industrial, agricultural and services sectors rose 2.9%, 4.2% and 3.8%, respectively, from 2005 to 2006, 4.7%, 5.9% and 5.4%, respectively, from 2006 to 2007, 4.3%, 5.8% and 4.8% from 2007 to 2008 and changed by -3.1%, -0.5% and 0.8%, respectively, from the last quarter of 2008 to the first quarter of 2009. Production in the industrial, agricultural and services sectors decreased 5.5%, 5.2% and rose 2.6%, respectively, from 2008 to 2009.

After six years of surpluses, Brazil’s current account had a deficit in 2008 of $28.2 billion. In 2009 the current account deficit closed at US$24.3 billion, and the balance of payments registered a surplus of US$46.7 billion, compared to a surplus of US$3.0 billion in 2008. Exports totaled US$153.0 billion in 2009, a 22.7% decrease over 2008, while imports totaled US$127.7 billion, a 26.2% decrease over 2008. Brazil’s net capital and financial account surplus was US$ 71.3 billion in 2009, which is an increase from the surplus of $29.4 billion in 2008. Foreign direct investment net inflows totaled US$25.9 billion in 2009, a decrease of 42.4% compared to 2008, and net portfolio investment inflows totaled US$46.1 billion in 2009, compared to a net inflow of negative US$0.78 billion in 2008.

From 2004 to 2007, Brazil registered successive trade balance surpluses of $33.6 billion, $44.7 billion, $46.5 billion and $40.0 billion, respectively. In 2008, Brazil registered a trade surplus of approximately $24.8 billion. Exports totaled $197.9 billion, a 23.2% increase over 2007, while imports totaled $173.2 billion, a 43.5% increase over 2007. In 2008, a trade balance and service and income deficit of $57.2 billion resulted in a current account deficit of approximately $28.2 billion, compared to a current account surplus of approximately $1.5 billion in 2007.

In 2009, Brazil registered a trade surplus of approximately US$25.3 billion. Exports totaled US$ 153.0 billion, a 23.2% decrease over 2008, while imports totaled US$ 127.7 billion, a 26.3% decrease over 2008. In 2009, a trade balance and service and income deficit of US$52.9 billion resulted in a current account deficit of approximately US$24.3 billion, compared to a current account deficit of approximately US$28.2 billion in 2008.

Since 1994, debt management policy has aimed at lengthening the maturity of domestic public debt, as well as consolidating a domestic yield curve by means of selling fixed income government securities. A portion of the Federal

D-8

Government’s federal domestic securities debt is indexed to inflation indices or foreign currencies. The portion of debt indexed to foreign currencies has been falling and there is an ongoing effort to substitute floating-rate bonds for fixed-rate and inflation-linked securities.

The consolidated public sector nominal balance (the difference between the level of consolidated public sector debt in one period and the level of such debt in the previous period, excluding the effects of the Federal Government’s privatization program and the effect of exchange rate fluctuations on the debt levels between periods), by contrast, showed deficits of 2.4% of GDP in 2004, 3.0% of GDP in 2005, 3.0% of GDP in 2006, 2.75% of GDP in 2007, 1.98% of GDP in 2008 and 2.84% in the first five months of 2009. The interest expense with respect to Brazil’s public sector debt represented 6.6% of GDP in 2004, rose to 7.3% of GDP in 2005, decreased to 6.8% of GDP in 2006, decreased further to 6.1% of GDP in 2007, and decreased to 5.6% of GDP in 2008. The accumulated nominal balance for the five-month period ended May 31, 2009 was a surplus of 2.84% of GDP, while interest expense was 5.5% of GDP.

Net public sector debt in Brazil, composed of the internal and external debt of the Federal Government, State and local governments and public sector enterprises, amounted to $360.5 billion (47.0% of GDP) in December 2004, $428.3 billion (46.5% of GDP) in December 2005, $499.2 billion (44.7% of GDP) in December 2006, $649.7 billion (42.7% of GDP) in December 2007 and $457.8 billion (35.8% of GDP) in December 2008. See “Public Debt—Table No. 31”.

In February 2008, the Central Bank introduced conceptual alterations in the calculation of the General Gross Government Debt (“GGGD”), to be initially applied to the January 2008 data, which (i) exclude National Treasury securities in the Central Bank’s portfolio and (ii) include repo operations for which the monetary authority is liable. The modifications take into consideration the entire securities debt held by the market, as the Treasury securities in the Central Bank’s portfolio do not represent effective fiscal debt, but are rather a monetary policy management instrument, and repo operations have a close relationship to the Treasury debt. According to the new methodology, GGGD reached 57.4% of GDP on December 31, 2007 (compared to 63.8% as calculated by the old methodology). The new calculation does not affect the net debt to GDP ratio.

Table No. 2

SELECTED BRAZILIAN ECONOMIC INDICATORS

| | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | |

| | | 2005 | | | 2006 | | | 2007 | | | 2008 | | | 2009 | |

The Economy | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | |

Gross Domestic Product: | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | |

(in billions of constant 2008 reais) | | R$ | 2,715.60 | | | R$ | 2,823.44 | | | R$ | 2,995.03 | | | R$ | 3,148.85 | | | R$ | 3,143.01 | |

(GDP at current prices in U.S.$ billions)(1) | | US$ | 882.44 | | | US$ | 1,088.77 | | | US$ | 1,366.54 | | | US$ | 1,636.02 | | | US$ | 1,577.26 | |

Real GDP Growth (decline)(2) | | | 3.16 | % | | | 3.97 | % | | | 6.08 | % | | | 5.14 | % | | | (0.19 | )% |

Population (millions) | | | 183.38 | | | | 185.56 | | | | 187.64 | | | | 189.61 | | | | 191.48 | |

GDP Per Capita(3) | | US$ | 4,811.99 | | | US$ | 5,867.33 | | | US$ | 7,282.73 | | | US$ | 8,628.22 | | | US$ | 8,237.20 | |

Unemployment Rate(4) | | | 8.30 | % | | | 8.40 | % | | | 7.40 | % | | | 6.80 | % | | | 6.80 | % |

IGP-DI (rate of change)(5) | | | 1.23 | % | | | 3.80 | % | | | 7.90 | % | | | 9.11 | % | | | (1.43 | )% |

Nominal Devaluation Rate(6) | | | (11.80 | )% | | | (8.70 | )% | | | (17.10 | )% | | | 31.90 | % | | | (25.49 | )% |

Domestic Real Interest Rate(7) | | | 17.60 | % | | | 10.90 | % | | | 3.70 | % | | | 3.10 | % | | | 11.52 | % |

Balance of Payments (in U.S.$ billions) | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | |

Exports | | | 118.31 | | | | 137.81 | | | | 160.65 | | | | 197.94 | | | | 152.99 | |

Imports | | | (73.61 | ) | | | (91.35 | ) | | | (120.62 | ) | | | (173.11 | ) | | | (127.65 | ) |

| | | | | |

Current Account | | | 13.99 | | | | 13.64 | | | | 1.55 | | | | (28.19 | ) | | | (24.30 | ) |

Capital and Financial Account (net) | | | (9.46 | ) | | | 16.30 | | | | 89.09 | | | | 29.35 | | | | 71.30 | |

Change in Total Reserves | | | 4.32 | | | | 30.57 | | | | 87.48 | | | | 2.97 | | | | 46.65 | |

D-9

| | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | |

Total Official Reserves | | | 53.80 | | | | 85.80 | | | | 180.30 | | | | 193.78 | | | | 238.52 | |

Public Finance | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | |

Financial Surplus (Deficit) as % of GDP(8) | | | (3.4 | )% | | | (3.5 | )% | | | (2.7 | )% | | | (1.9 | )% | | | (3.3 | )% |

Primary Surplus (Deficit) as % of GDP(9) | | | 3.9 | | | | 3.2 | | | | 3.4 | | | | 3.5 | | | | 2.1 | |

Public Debt (in billions) | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | |

Gross Internal Debt (Nominal)(10) | | US$ | 543.7 | | | US$ | 677.4 | | | US$ | 977.1 | | | US$ | 793.0 | | | US$ | 1,228.9 | |

Gross External Debt (Nominal)(11) | | | 85.5 | | | | 73.9 | | | | 69.3 | | | | 66.2 | | | | 73.6 | |

Public Debt as % of Nominal GDP | | | 68.2 | | | | 66.2 | | | | 66.1 | | | | 65.0 | | | | 72.2 | |

Net Internal Debt | | | 59.0 | | | | 59.7 | | | | 61.7 | | | | 60.0 | | | | 68.1 | |

Net External Debt(12) | | | 9.3 | | | | 6.5 | | | | 4.4 | | | | 5.0 | | | | 4.1 | |

Total Public Debt (Nominal)(13) | | US$ | 629.20 | | | US$ | 751.3 | | | US$ | 1,046.4 | | | US$ | 859.2 | | | US$ | 1,302.5 | |

| (1) | Converted into dollars based on the weighted average exchange rate for each year. |

| (2) | Calculated based upon constant average 2009 reais. |

| (3) | Not adjusted for purchasing power parity. |

| (4) | Unemployment in the metropolitan areas of Rio de Janeiro, São Paulo, Belo Horizonte, Porto Alegre, Salvador and Recife at the end of the relevant period. |

| (5) | IGP-DI is one indicator of inflation. While many inflation indicators are used in Brazil, the IGP-DI, calculated by the Getúlio Vargas Foundation, an independent research organization, is one of the most widely utilized indices. |

| (6) | Year-on-year percentage appreciation of the dollar against the real (sell side). |

| (7) | Brazilian federal treasury securities deflated by the IGP-DI and adjusted at each month-end to denote real annual yield. |

| (8) | Financial results represent the difference between the consolidated public sector debt in one period and the consolidated public sector debt in the previous period, excluding the effects of the Federal Government’s privatization program and the effect of exchange rate fluctuations on the debt levels between periods. |

| (9) | Primary results represent Federal Government revenues less Federal Government expenditures, excluding interest expenditures on public debt. |

| (10) | Presents debt on a consolidated basis, which is calculated as the gross internal debt less credits between governmental entities. |

| (11) | Not including external private debt. Consolidated external private debt as of December 31, 2009 was $85.0 billion. |

| (12) | Gross external debt less total reserves. |

| (13) | Consolidated gross public sector debt. |

Sources: IBGE; Getúlio Vargas Foundation; Central Bank.

D-10

THE FEDERATIVE REPUBLIC OF BRAZIL

Area and Population

Brazil is the fifth largest country in the world and occupies nearly half the land area of South America. Brazil is officially divided into five regions consisting of 26 States and the Federal District, where the Republic’s capital, Brasília, is located.

Brazil has one of the most extensive river systems in the world. The dense equatorial forests and semi-arid plains of the North are drained by the Amazon River and the fertile grasslands of the South by the Paraná, Paraguay and Uruguay Rivers. Other river systems drain the central plains of Mato Grosso and the hills of Minas Gerais and Bahia. Most of the country lies between the Equator and the Tropic of Capricorn, and the climate varies from tropical to temperate. More than half of the total terrain of Brazil consists of rolling highlands varying from 650 to 3,000 feet in altitude.

According to the demographic census conducted by the IBGE in 2000, Brazil had an estimated population of 169.8 million that year. IBGE also estimates that the population is currently growing at a rate of 1.6% per year. Approximately 138.0 million people, or 81.2% of the population, live in urban areas; the urban population has been increasing at a greater rate than the population as a whole. The largest cities in Brazil were São Paulo and Rio de Janeiro, with estimated populations of 10.4 million and 5.9 million, respectively, according to the 2000 census. Other cities with populations in excess of one million were Brasília, Belém, Belo Horizonte, Curitiba, Fortaleza, Goiânia, Manaus, Porto Alegre, Recife and Salvador. The States with the largest GDP in Brazil, São Paulo, Rio de Janeiro and Minas Gerais, had populations in excess of 37.0 million, 14.4 million and 17.9 million, respectively, on December 31, 2000.

There were approximately 160.6 million persons of working age (10 or more years of age) in Brazil in 2008. The active labor force was composed of 92.4 million persons, of whom approximately 17.4% worked in retail, 9.2% in education, health and social services, approximately 17.4% in agriculture and related areas, approximately 15.1% in industry, approximately 7.5% in civil construction, approximately 4.9% in public administration and 28.4% in other services.

Although social welfare indicators in Brazil such as per capita income, life expectancy, and infant mortality do not compare favorably to those of certain of Brazil’s neighboring countries, statistics in the Human Development Report for 2009, published by the United Nations Development Program, show that Brazil has made significant progress in improving social welfare over the past three decades. During that period, life expectancy in Brazil increased by approximately 21.3% (from 59.5 years in 1970-1975 to 72.2 years in 2007) and the infant mortality rate decreased 76.8% (from 95 per 1,000 live births in 1970 to22 per 1,000 live births in 2007). Adjusted for purchasing power parity by the United Nations, real GDP per capita rose 0.9% annually from 1975 to 2007. In addition, the reduction in inflation under the Plano Real and the consequent diminution of the erosion of purchasing power have improved the social welfare of large numbers of lower-income Brazilians.

The following table sets forth comparative GDP per capita figures and selected other comparative social indicators for 2005:

Table No. 3

Social Indicators, 2007

| | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | |

| | | Brazil | | | Argentina | | | Chile | | | Ecuador | | | Mexico | | | Peru | | | U.S. | | | Venezuela | |

Real GDP per capita(1) | | $ | 9,567 | | | $ | 13,238 | | | $ | 13,880 | | | $ | 7,449 | | | $ | 14,104 | | | $ | 7,836 | | | $ | 45,592 | | | $ | 12,156 | |

Life expectancy at birth (years) | | | 72.2 | | | | 75.2 | | | | 78.5 | | | | 75.0 | | | | 76.0 | | | | 73.0 | | | | 79.1 | | | | 73.6 | |

Infant mortality rate (per 1,000 births) | | | 22.0 | | | | 16.0 | | | | 9.0 | | | | 25.0 | | | | 17.0 | | | | 24.0 | | | | 8.0 | | | | 18.0 | |

Adult literacy rate | | | 90.0 | % | | | 97.6 | % | | | 96.5 | % | | | 91.0 | % | | | 92.8 | % | | | 89.6 | % | | | 99.0 | % (2) | | | 95.2 | % |

| (1) | Based on 2007 figures, adjusted for purchasing power parity by the United Nations. Per capita GDP amounts in this chart therefore differ from the amounts for per capita annual income set forth in “Summary Economic Information”. |

| (2) | For purposes of calculating its “Human Development Index”, the United Nations Development Program applied a rate of 99.0%. |

Source: United Nations Development Program, Human Development Report 2009.

D-11

Form of Government and Political Parties

Brazil was discovered by the Portuguese navigator Pedro Álvares Cabral in the year 1500 and remained a Portuguese colony for more than 300 years. The colonial government, first established in Salvador in the Northeast, was transferred to Rio de Janeiro in 1763. During the Napoleonic wars the Portuguese court moved from Lisbon to Rio de Janeiro, where it remained until 1821. In the following year Brazil declared its independence from Portugal, and the Prince Regent Dom Pedro I became Emperor of Brazil. His successor, Dom Pedro II, ruled Brazil for 49 years, until the proclamation of the Republic on November 15, 1889. From 1889 to 1930, the presidency of the Republic generally alternated between officeholders from the dominant States of Minas Gerais and São Paulo. This period, known as the First Republic, ended in 1930, when Getúlio Dorneles Vargas took power. Vargas governed Brazil for the next fifteen years, first as chief of a provisional government (1930-1934), then as a constitutional president elected by Congress (1934-1937) and finally as dictator (1937-1945) of a government that he termed the New State (Estado Novo). During the period from 1945 to 1961, Brazil held direct elections for the presidency. The resignation of President Jânio da Silva Quadros in 1961 after less than seven months in office and the resistance to the succession to the presidency of Vice President João Goulart created a political crisis that culminated in the establishment of a parliamentary system of government. The new system of government lasted approximately 16 months. In January 1963, after a plebiscite, Brazil returned to a presidential government, which was overthrown by the military in March 1964. Military governments ruled Brazil from 1964 until 1985, when a civilian president was elected by means of an electoral college composed of Senators and Deputies.

Thereafter, a series of political reforms was enacted, including the reestablishment of direct elections for the President and the calling of a Constitutional Assembly which, in October 1988, adopted a new Brazilian Constitution. In December 1989, Fernando Collor de Mello was elected President of Brazil for a five-year term in the first direct presidential election since 1960. Since October 1994, Brazil’s Presidents have been elected to serve four-year terms. In October 2006, Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva of PT was reelected as President of Brazil; he assumed his second presidential term on January 1, 2007.

Brazil is a federative republic with broad powers granted to the Federal Government. The Constitution provides for three independent branches of government: an executive branch headed by the President; a legislative branch consisting of the bicameral National Congress, composed of the Chamber of Deputies and the Senate; and a judicial branch consisting of the Federal Supreme Court and lower federal and State courts. The Constitution provided for a mandatory constitutional review that began in October 1993 and ended on May 31, 1994. The review resulted in the adoption of six amendments, which included the reduction of the presidential term of office from five to four years. The Constitution also provided for a plebiscite in April 1993 in which voters were permitted to consider alternative systems of government, including a return to the monarchy; in that plebiscite, the Brazilian electorate voted overwhelmingly to maintain the presidential system of government.

Under the Constitution, the President is elected by direct vote. A constitutional amendment adopted in June 1997 permits the re-election for a second term of the President and certain other elected officials. The President’s powers include the right to appoint ministers and key executives in selected administrative posts. The President may issue provisional measures (medidas provisórias) with the same scope and effect as legislation enacted by the National Congress. However, Constitutional Amendment No. 32, which became effective on September 12, 2001, prohibits the issuance of provisional measures for, among other things, the implementation of multi-year plans and budgets, the seizure of financial or other assets, and the regulation of matters which the Constitution specifically requires the National Congress to regulate through complementary law. Under Constitutional Amendment No. 32, provisional measures are enforceable for up to 60 days, extendable for a single additional period of 60 days. If a provisional measure is rejected or if it is not voted by the National Congress within the enforcement period, the provisional measure becomes invalid as of the date it was issued. The amendment expressly prohibits the re-issuance of provisional measures not voted by the National Congress within the enforcement period.

The legislative branch of government consists of a bicameral National Congress composed of the Senate and the Chamber of Deputies. Ordinary legislation requires a simple majority vote in both houses of the National Congress for adoption. Amendments to the Constitution require an absolute three-fifths majority vote, in each of two rounds of voting, in both houses of the legislature. A matter addressed in a proposed amendment that is rejected cannot be reproposed during the same legislative session. The Senate is composed of 81 Senators, elected for staggered eight-year terms, and the Chamber of Deputies has 513 Deputies, elected for concurrent four-year terms. Each State and the Federal District is entitled to three Senators. The number of Deputies is based on a proportional representation system weighted in favor of the less populated States which, as the population increases in the larger States, assures the smaller States an important role in the National Congress.

D-12

The judicial power is exercised by the Federal Supreme Court (composed of 11 Justices), the Superior Court of Justice (composed of 33 Justices), the Federal Regional Courts (appeals courts), military courts, labor courts, electoral courts and the several lower federal courts. The Federal Supreme Court, whose members are appointed for life by the President, has ultimate appellate jurisdiction over decisions rendered by lower federal and State courts on Constitutional matters.

Brazil is divided administratively into 26 States and the Federal District. The States are designated as autonomous entities within the federative union and have all powers that the Constitution does not preclude the States from exercising. The Constitution reserves to the Republic the exclusive power to legislate in certain areas, including, among others, monetary systems, foreign affairs and trade, social security and national defense. The States may exercise legislative power in matters not reserved exclusively to the Republic and have, concurrently with the Republic, certain powers of taxation. At the State level, executive power is exercised by governors elected for four-year terms and legislative power by State deputies also elected for four-year terms. Judicial power at the State level is vested in the State courts, and appeals of State court judgments may be taken to the Superior Court of Justice and the Federal Supreme Court.

Federal, State and Local Elections

National general elections were held in October 2006. The offices of the President and State Governors, one-third of the Senate and all the seats in the Federal Chamber of Deputies, as well as seats in the State legislatures, were determined pursuant to the election. After winning a runoff election with 60.8% of the vote on October 29, 2006, Mr. da Silva was reelected as part of a coalition, consisting of the Brazilian Party of the Republic and PCdoB. Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva assumed the presidency of Brazil on January 1, 2007. Mr. da Silva is a member of the PT. Following the October 2006 elections, Mr. da Silva’s party held 16.0% of the seats in the Chamber of Deputies and 14.8% of the seats in the Senate.

On October 3, 2010, and if need be, in a second round on October 31, 2010, a presidential election will be held in Brazil. The President is elected directly to a four-year term, with a limit of two terms. President Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva, of the Workers’ Party (Partido dos Trabalhadores), is ineligible for reelection under the Brazilian constitution, having served two successive terms. Among the candidates running for presidential include Dilma Rousseff, of the Workers’ Party (Partido dos Trabalhadores) and Jose Serra, of the Social Democratic Party (Partido da Social Democracia Brasileira), along with candidates from other political parties. In addition, all 27 governors (of the 26 States and of the Federal District), all 513 members of the lower house of Congress and 54 of the 81 senators are also up for election.

External Affairs and Membership in International Organizations

Brazil maintains diplomatic and trade relations with almost every nation in the world. It has been a member of the United Nations since 1945. The Republic participates in the organizations under the control of the United Nations Secretariat, as well as others of a voluntary character, such as the International Fund for Agriculture and Development.

Brazil is an original member of the IMF and the World Bank, as well as three affiliates of the World Bank, the International Finance Corporation, the International Development Association and the Multilateral Investment Guaranty Agency. Brazil was an original member of the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (“GATT”) and is a charter member of the World Trade Organization. In addition, Brazil is an original member of the Inter-American Development Bank (“IDB”), the Inter-American Investment Corporation, the African Development Bank Group and the International Fund for Agricultural Development.

At the regional level, Brazil participates in the Organization of American States (“OAS”) and in several sub-regional organizations under the OAS, as well as in the Latin American Economic System, the Latin American Integration Association, the Andean Development Corporation and the Financial Fund for the Development of the River Plate Basin.

In March 1991, Brazil, Argentina, Paraguay and Uruguay entered into the Treaty of Asunción, formally establishing the Southern Common Market (Mercado Comum do Sul, or “Mercosul”), a common market organization composed of the signatory nations. In December 1994, the four member countries signed an agreement establishing the date of January 1, 1995 for the implementation of a Common External Tariff (“CET”) intended to transform the region into a customs union. However, under Decision No. 59 of the Common Market Council (Conselho do Mercado Comun) dated December 17, 2007, each member country (other than Paraguay and Uruguay) is permitted a list of 100 basic items as exceptions to the CET to be completely eliminated by December 31, 2010, while Paraguay and Uruguay are permitted a list of up to 649 items and 225 items, respectively, to be eliminated completely by 2015. Because of these exceptions to the CET, the full implementation of a customs union has not yet been achieved.

D-13

Mercosul has six associate members: Bolivia, Chile, Colombia, Ecuador, Peru and Venezuela. Associate members are included in free trade treaties but have no voting rights within Merscosul. On July 4, 2006, Venezuela signed in Córdoba, Argentina, the adhesion protocol to Mercosul, officially declaring its intention of becoming the fifth integrant country of the bloc, a commitment that will last for the next four years. In this period, Venezuela will have to adapt to the norms of Mercosul, including the application of the CET. However, the completion of the free trade process between Venezuela and the four remaining partners will not be completed until January 2014.

Mercosul has attempted to form trading relations with other countries. Brazilian Presidential Decree No. 4,458 dated November 5, 2002, ratified an automobile accord between Mercosul and Mexico that is intended to increase trade in automotive products between the two parties. In December 2004, Mercosul concluded preferential trade accords with India and the Southern African Customs Union. In December 2007, Mercosul also established a free trade agreement with the State of Israel.

At the first Summit of the Americas in Miami, Florida, in December 1994, Brazil joined 33 other countries in the Western Hemisphere in negotiations for the establishment of a Free Trade Area of the Americas. In December 1995, Mercosul and the European Union signed a framework agreement for the development of free trade between them. In 1996, Mercosul signed agreements with Chile and Bolivia, effective October 1996 and February 1997, respectively, for the development of free trade among them; these agreements were approved by the Brazilian National Congress in September 1996 and April 1997, respectively. Mercosul also signed an agreement with Chile, approved by Brazilian Presidential Decree No. 4,404 dated October 3, 2002, that provides for the reduction of tariffs for certain automotive, chemical and agricultural products in trade between Brazil and Chile.

On December 9, 2007, the presidents of Brazil, Argentina, Paraguay, Uruguay, Bolivia, Equator and Venezuela signed the creation of the Banco do Sul. The institution aims at being an alternative to multilateral institutions such as the IMF and the World Bank for the funding of development projects in the region. The Covenant Establishing the Banco do Sul was signed by seven countries in September 2009 in Venezuela.

On September 8, 2008, the Central Bank and the central bank of Argentina signed a convention that establishes the general rules of operation of the System of Payments in Local Currency (Sistema de Pagamentos Brasileiro, or “SML”). The SML is a payment system focused on business deals, which allows importers and exporters in Brazil and Argentina to make and receive payments in their local currencies. SML operations began on October 2, 2008.

On June 30, 2008, two framework agreements to form a free trade area between Mercosur and the Republic of Turkey and between Mercosur and the Hashemite Kingdom of Jordan were signed.

On April 3, 2009, the Customs Union of Southern Africa (“SACU”), a block that consists of five African countries (South Africa, Botswana, Lesotho, Namíbia and Swaziland), signed an agreement with Mercosur that provides for a reduction in the trade tariffs between the two economic blocks. This is the third agreement that Mercosur has signed beyond its region. The previous agreements were signed with India in 2005 and Israel in 2007. Decree No. 7,159 of April 27, 2010 set forth the Free Trade Agreement between Mercosur and Israel. With this decree, the Free Trade Agreement became effective in Brazil and created a free trade area that removes most tariff barriers for trade in goods between the two countries.

On June 10, 2009, the Minister of Finance, Guido Mantega, announced that Brazil intends to lend US$10 billion to the IMF, which is approximately the Brazilian quota in the IMF. This decision is a result of the G-20 meeting held in London on April 2, 2009, in which President Lula stated that Brazil wished to contribute to the IMF. The IMF will issue bonds to Brazil in exchange for the US$10 billion loan. The closing of this loan is conditioned upon the issuance of such bonds by the executive Directors of the IMF and also on the end of the revision process of the New Agreement to Borrow (“NAB”). The agreement for this loan was signed between Brazil and the IMF on January 22, 2010.

The Bank for International Settlements (BIS) formalized, on December 9, 2009, the entry of Brazil in the Committee on the Global Financial System and Markets, which has the responsibility of monitoring the development of financial markets for major Central Banks as its main function.

D-14

THE BRAZILIAN ECONOMY

Historical Background

From the late 1960s through 1982, Brazil followed an import-substitution, high-growth development strategy financed, in large part, by heavy recourse to foreign borrowings. Foreign debt grew at an accelerated pace in response to the oil shocks of the 1970s and, when international interest rates rose sharply in 1979-80, the resulting accumulated external debt became one of Brazil’s most pressing problems in the decade that followed. See “Public Debt—Debt Crisis and Restructuring”. The debt crisis of the 1980s and high inflation substantially depressed real growth of Brazil’s GDP, which averaged 2.3% per year from 1981 to 1989. The public sector’s role in the economy also expanded markedly, with many key economic sectors subject to Federal Government monopoly or subsidized participation, and significant structural distortions were introduced through high tariffs and the creation of subsidies and tax credit incentives. Significant increases in the money supply to finance a large and growing fiscal deficit further fueled inflationary pressures.

Efforts to address these problems during the late 1980s and early 1990s were largely unsuccessful. High inflation and the recurrent threat of hyperinflation during this period prompted the Federal Government to pursue a series of stabilization plans, but these plans were mostly ineffective because they lacked important supporting mechanisms. Stabilization measures implemented at that time relied on mechanisms, such as price and wage freezes and/or unilateral modifications of the terms of financial contracts, that were not supported by fiscal and monetary reforms. A central problem during this period was the public sector, which ran operational deficits averaging more than 5% of GDP during the five-year period from 1985 to 1989, while monetary policy was compromised by the short-term refinancing of public sector debt. These problems were aggravated by the 1988 Constitution, which limited the ability of the Federal Government to dismiss public sector employees and reallocated public resources, in particular tax revenues, from the Federal Government to the States and municipalities without a proportional shift of responsibilities to them, thereby further constraining the effectiveness of Federal Government fiscal policy. The practice of inflation indexation in the economy, which made prices downwardly rigid, also helped to undermine stabilization measures. See “—Relationship between the Federal and Local Governments”, “—Employment” and “Public Finance—Taxation and Revenue Sharing Systems”.

In December 1993, the Federal Government announced a stabilization program, known as the Plano Real, aimed at curtailing inflation and building a foundation for sustained economic growth. The Plano Real was designed to address persistent deficits in the Federal Government’s accounts, expansive credit policies and widespread, backward-looking indexation.

The Plano Real had three stages. The first stage included a fiscal adjustment proposal for 1994, consisting of a combination of spending cuts and an increase in tax rates and collections intended to eliminate a budget deficit originally projected at $22.0 billion. Elements of the proposal included (i) cuts in current expenditures and investment through the transfer of some activities from the Federal Government to the States and municipalities, (ii) the establishment of an Emergency Social Fund, financed by reductions in constitutionally mandated transfers of Federal Government revenues to the States and municipalities, to ensure financing of social welfare spending by the Federal Government, (iii) a prohibition on sales of public bonds by the Federal Government, except to refinance existing debt and for certain specified expenditures and investments, (iv) new taxes, including a new levy on financial transactions, and (v) the collection of the Contribution for the Financing of Social Security (Contribuição para o Financiamento da Seguridade Social, or “COFINS”) in order to finance health care and welfare programs, following the November 1993 confirmation by the Federal Supreme Court that such contributions were permissible under the Constitution.

The second stage of the Plano Real, initiated on March 1, 1994, began the process of reform of the Brazilian monetary system. Brazil’s long history of high inflation had led to the continuous and systematic deterioration of the domestic currency, which no longer served as a store of value and had lost its utility as a unit of account. Because inflation had reduced dramatically the information content of prices quoted in local currency, economic agents had included in their contracts a number of mechanisms for indexation (providing for the adjustment of the amounts payable thereunder by an agreed-upon inflation or tax rate to preserve the economic value of such contracts) and the denomination of obligations in indexed units of account. The process of rehabilitation of the national currency began with the creation and dissemination of the Unit of Real Value (Unidade Real de Valor, or “URV”) as a unit of account. The second stage of the Plano Real was designed to eliminate the indexation of prices to prior inflation and to link indexation to the URV instead.

The third stage of the Plano Real began on July 1, 1994, with the introduction of the real as Brazil’s currency. The real replaced the cruzeiro real as the lawful currency of Brazil, with each real exchangeable for 2,750 cruzeiros reais. This was the last in a series of currency replacements that occurred from 1986 through 1994. The cruzeiro real had replaced the cruzeiro as

D-15

the lawful currency of Brazil on August 1, 1993, with each cruzeiro real exchangeable for 1,000 cruzeiros; the cruzeiro had replaced the cruzado novo as the lawful currency of Brazil under the Collor Plan of March 15, 1990, with each cruzeiro exchangeable for one cruzado novo; the cruzado novo had replaced the cruzado as the lawful currency of Brazil under the Summer Plan of January 16, 1989, with each cruzado novo exchangeable for 1,000 cruzados; and the cruzado had replaced the cruzeiro as the lawful currency of Brazil under the Cruzado Plan of February 28, 1986, with each cruzado exchangeable for 1,000 cruzeiros. In the third stage of the Plano Real, all contracts denominated in URVs were automatically converted into reais at a conversion rate of one to one, and the URV, together with the cruzeiro real, ceased to exist (although the cruzeiro real was generally accepted until August 31, 1994). The real initially appreciated against the U.S. dollar, with the rate in the commercial market (sell side) moving from R$1.00/dollar, when the real was introduced, to R$0.829/dollar on October 14, 1994. In March 1995, the Central Bank formalized an exchange band system pursuant to which the real would be permitted to float against the U.S. dollar within bands established by the Central Bank. Thereafter, the real gradually declined in value against the dollar, reaching R$1.1164 per dollar on December 31, 1997 and declining further to R$1.2087 per dollar on December 31, 1998. However, the Central Bank was forced in January 1999 to abandon its exchange band mechanism, which encouraged small exchange devaluations within a specified range, and permit the value of the real to float freely against that of the U.S. dollar.

Largely as a result of the measures under the Plano Real, the average monthly rate of inflation dropped significantly from 43.2% during the first half of 1994 to 2.65% during the second half of that year. The annual rate of inflation for 1994 was 909.6%, down from 2,708.4% in 1993. The public sector operational balance also showed a surplus of 1.3% of GDP in 1994, versus a 0.2% of GDP public sector operational surplus in 1993. However, the external accounts showed a higher current account deficit in 1994 as a result of an increase in imports and a reduction in net capital account surplus.

In January 1999, Brazil’s international reserves came under significant pressure as a result of a series of events that month. On January 6, 1999, the newly inaugurated governor of the State of Minas Gerais announced that the State would suspend for 90 days payments with respect to the State’s approximately R$18.3 billion debt to the Federal Government. A week later, on January 13, 1999, Gustavo H.B. Franco, the president of the Central Bank and one of the architects of the Plano Real, resigned and was replaced by Francisco Lopes, who attempted a controlled devaluation of the real by widening the band within which the real was permitted to trade. Subsequent Central Bank intervention failed to keep the real-U.S. dollar exchange rate within the new band, however, and on January 15, 1999, the Central Bank announced that the real would be permitted to float, with Central Bank intervention to be made only in times of extreme volatility.

On February 2, 1999, the Federal Government designated Armínio Fraga Neto to replace Francisco Lopes as president of the Central Bank. Following Mr. Fraga’s confirmation on March 3, 1999, the Central Bank eliminated two widely used overnight rates, the Central Bank Basic Rate (Taxa Básica do Banco Central) and the Central Bank Assistance Rate (Taxa de Assistência do Banco Central), giving primacy to the Over/Selic rate; because the Central Bank could influence the Over/Selic rate on a daily basis through its participation in auctions, repurchase transactions and reverse repurchase transactions, the Over/Selic rate permitted the Central Bank to react more quickly to changes in market conditions.

Following its decision to permit the real to float, the Federal Government formally adopted inflation targeting as its monetary policy framework. See “The Financial System—Monetary Policy and Money Supply”. The Federal Government also began negotiations with the IMF on adjustments to the 1999-2001 economic program agreed in November 1998 and new economic targets in light of the new foreign exchange regime introduced in January 1999.

During the second half of 2000, uncertainties about the U.S economy, concerns about Argentina and rising oil prices caused the real to decline in value against the U.S. dollar. The real-U.S. dollar exchange rate (sell side) in the commercial exchange market, as published by the Central Bank, declined 7.5% from R$1.8234 to $1.00 on August 31, 2000 to R$1.9596 to $1.00 on November 30, 2000. Brazil’s continued compliance with a $41.8 billion IMF-led support program agreed on November 13, 1998, as established by the IMF’s sixth review on November 28, 2000, and an improvement in the external environment resulting from interest rate reductions in the United States, reduced the downward pressure on the exchange rate, which ended the year at R$1.9554 to $1.00. The improved conditions also permitted the Central Bank to lower its Over/Selic rate target to 15.75% on December 20, 2000 and 15.25% on January 17, 2001.

From 2001 to 2002 the real suffered from multiple external and domestic pressures that ultimately led to the depreciation of the currency. Key external factors included Argentina’s financial crisis, misgivings about Argentine exchange rate policies, uncertainties about the U.S. economy, rising oil prices and the September 11th attacks. Domestic pressures included severe power shortages and election uncertainties.

D-16

To avoid further depreciation of the real, the Central Bank intervened in the foreign exchange market by selling U.S. dollars and buying reais. The Central Bank also raised its Over/Selic rate target to limit increases in core inflation, uncertainties related to the effects of exchange rate depreciation and the accelerating pace of economic activity. In addition, the Federal Government sought to contain currency deprecation by increasing its international reserves available for financing future interventions to support the real.

The real was also helped by the IMF’s approval of standby facilities for Brazil. On September 14, 2001, the IMF announced that its Executive Board had approved a new standby facility for Brazil in the amount of SDR 12.14 billion (approximately $15.6 billion) in support of the Federal Government’s economic and financial program through December 2002.

The IMF approved on October 29, 2008, the “Short-Term Liquidity Facility”, a tool to address short-term external liquidity to its member countries as a result of a liquidity shortage in the international interbank system. Brazil can draw the equivalent of 500% of its quota in the IMF for a period of three months, renewable for another two periods of three months. Every twelve months, the member country will be entitled to make a maximum of three successive withdrawals. The borrower country must declare in a letter to the IMF Managing Director its commitment to maintain sound macroeconomic policies.