EXHIBIT D

Republic of Panama

This description of the Republic of Panama is dated as of September 29, 2017 and appears as Exhibit D to the Republic of Panama’s Annual Report on Form 18-K to the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission for the fiscal year ended December 31, 2016.

D-1

TABLE OF CONTENTS

| | | | |

| | | Page | |

RECENT DEVELOPMENTS | | | D-5 | |

THE REPUBLIC OF PANAMA | | | D-15 | |

THE PANAMANIAN ECONOMY | | | D-18 | |

STRUCTURE OF THE PANAMANIAN ECONOMY | | | D-30 | |

THE PANAMA CANAL | | | D-36 | |

THE COLÓN FREE ZONE | | | D-42 | |

EMPLOYMENT AND LABOR | | | D-44 | |

PUBLIC FINANCE | | | D-49 | |

FINANCIAL SYSTEM | | | D-56 | |

FOREIGN TRADE AND BALANCE OF PAYMENTS | | | D-63 | |

PUBLIC SECTOR DEBT | | | D-73 | |

TABLES AND SUPPLEMENTARY INFORMATION | | | D-79 | |

The fiscal year of the Government of the Republic of Panama (the “Government”) ends on December 31. The twelve-month period ended December 31, 2016 is referred to in this description of the Republic of Panama as “2016” and other years are referred to in a similar manner unless otherwise indicated. All references to “U.S.$”, “$” or “dollars” are to United States Dollars.

Totals in certain tables in this description of the Republic of Panama may differ from the sum of the respective individual items in such tables due to rounding.

D-2

INDEX OF TABLES

| | | | | | |

| | | | | Page | |

TABLE NO. 1 | | Selected Panamanian Economic Indicators | | | D-13 | |

TABLE NO. 2 | | Inflation (percentage change from previous period) | | | D-26 | |

TABLE NO. 3 | | Gross Domestic Product | | | D-27 | |

TABLE NO. 4 | | Sectoral Origin of Gross Domestic Product (in millions of dollars) | | | D-27 | |

TABLE NO. 5 | | Percentage Change from Prior Year for Sectoral Origin of Gross Domestic Product (percentage change) | | | D-28 | |

TABLE NO. 6 | | Sectoral Origin of Gross Domestic Product (as percentage of GDP) | | | D-29 | |

TABLE NO. 7 | | Selected State-Owned Enterprises 2016 Financial Statistics (in millions of dollars) | | | D-31 | |

TABLE NO. 8 | | Panama Canal Principal Statistics | | | D-36 | |

TABLE NO. 9 | | Labor Force and Employment | | | D-45 | |

TABLE NO. 10 | | Average Real Monthly Wages | | | D-46 | |

TABLE NO. 11 | | Budgeted Expenditures of the Central Government by Function (in millions) | | | D-49 | |

TABLE NO. 12 | | Fiscal Performance - Central Government | | | D-51 | |

TABLE NO. 13 | | Fiscal Performance - Consolidated Non-Financial Public Sector | | | D-53 | |

TABLE NO. 14 | | Central Government Operations (in millions of dollars) | | | D-53 | |

TABLE NO. 15 | | Consolidated Non-Financial Public Sector Operations (in millions of dollars) | | | D-54 | |

TABLE NO. 16 | | International Reserves (in millions of dollars) | | | D-55 | |

TABLE NO. 17 | | Largest Banking Institutions (assets in millions of dollars) | | | D-56 | |

TABLE NO. 18 | | The Banking Sector (in millions of dollars) | | | D-57 | |

TABLE NO. 19 | | Banco Nacional de Panamá Balance Sheet (in millions of dollars) | | | D-60 | |

TABLE NO. 20 | | Composition of Merchandise Exports, F.O.B. (in millions of dollars) | | | D-64 | |

TABLE NO. 21 | | Composition of Merchandise Imports, C.I.F. (in millions of dollars) | | | D-65 | |

TABLE NO. 22 | | Direction of Merchandise Trade (as percentage of total) | | | D-67 | |

TABLE NO. 23 | | Foreign Direct Investment in Panama by Investor Residence | | | D-68 | |

TABLE NO. 24 | | Foreign Direct Investment in Panama by Category of Economic Activity | | | D-70 | |

TABLE NO. 25 | | Balance of Payments (in millions of dollars) | | | D-72 | |

TABLE NO. 26 | | Public Sector Internal Debt (in millions of dollars) | | | D-74 | |

TABLE NO. 27 | | Public Sector External Debt (in millions of dollars) | | | D-75 | |

TABLE NO. 28 | | Public Sector External Debt Amortization (in millions of dollars) | | | D-75 | |

TABLE NO. 29 | | External Direct Debt of the Republic Central Government | | | D-79 | |

TABLE NO. 30 | | External Debt Guaranteed by the Republic Decentralized Institutions | | | D-80 | |

TABLE NO. 31 | | Internal Funded Debt Securities of the Republic | | | D-80 | |

D-3

D-4

RECENT DEVELOPMENTS

Presentation of Economic and Other Information

The Office of the Comptroller General has updated the base year used for the System of National Accounts from 1996 to 2007. International best practices call for updating the constant GDP base year at least every 10 years to reflect structural changes in production, consumption and prices, and to ensure that the National Accounts provide a more accurate depiction of the economy given its dynamism. Data for the Colón Free Zone (“CFZ”) and the Panama Canal have not yet been published using the new base year.

Government financial statistics and related tables are presented in accordance with the IMF Government Finance Statistics Manual 1986 (“GFSM 1986”). Real sector statistics are presented in accordance with the UN 1993 System of National Accounts (“SNA 1993”); however, with the change of base year from 1996 to 2007, financial intermediation activity is being measured following the UN 2008 System of National Accounts (“SNA 2008”). Balance of payments statistics for 2013 to 2016 were calculated pursuant to the Sixth Edition of the Balance of Payments and International Investment Position Manual published by the International Monetary Fund (“IMF”). Balance of payments statistics for 2012 were calculated pursuant to the Fifth Edition of the IMF Balance of Payments Manual.

Open unemployment figures are no longer presented. Unemployment figures are now used.

Political Developments

On May 4, 2014, Panama held general elections for the posts of president, members of the Assembly and other regional posts. The then-incumbent Vice President, Juan Carlos Varela, was elected President with 39.08% of the vote obtained by the “El Pueblo Primero” alliance composed of the Partido Popular and Partido Panameñista. President Varela took office on July 1, 2014. On July 1, 2014, President Juan Carlos Varela appointed Dulcidio De La Guardia as Minister of Economy and Finance. On July 1, 2014, Iván A. Zarak Arias was appointed Vice Mister of Economy and Eyda Varela de Chinchilla was appointed Vice Minister of Finance. Isabel de Saint Malo de Alvarado was elected as Vice President on the same day as the President and was appointed Minister of Foreign Affairs.

On December 3, 2013, then presidential candidate Varela announced the priorities of his administration in a Plan for the El Pueblo Primero Alliance. The Plan included, among other initiatives, implementation of price controls on basic foods to reduce the cost of living and initiatives to maintain the growth of the Panamanian economy through public investment projects, such as plans to provide potable water nationwide; to construct Metro lines 2 and 3 to San Miguelito and East and West Panama City; to construct 500 kilometers of new highways, 15 health centers and four hospitals; and to increase the coverage of the irrigation system from 20% to 40% of all cultivated land. The Plan also called for new rules to increase transparency in the government and to reduce corruption and cronyism.

Through Executive Decree No. 689 of December 26, 2014, the Varela administration adopted its five-year Strategic Government Plan, “Un solo país”. The Plan includes the economic and social strategy, the financial program and a five-year indicative public investment plan that establishes the criteria for public expenditure for prioritized sectors, programs and projects. Such prioritized sectors include, among others, transportation, energy, agriculture and tourism, while projects and programs include a project to improve access to potable water and a program to improve education.

Upon taking office, the Varela administration initiated investigations of possible corruption by former government officials who served in the administration of President Ricardo Martinelli. Several former officials have been subject to preventive measures during the pendency of proceedings. On March 11, 2016, public prosecutor Jeronimo Mejía issued a request to the Ministry of Foreign Affairs to seek the extradition of former president Ricardo Martinelli from the United States. The Supreme Court of Justice previously had ordered the provisional arrest of former president Martinelli and authorized Mr. Mejía to take any necessary actions to effect the arrest. The former president is accused of illegal telephone wiretapping, invasion of privacy and crimes against the public administration. On September 27, 2016, the Ministry of Foreign Affairs submitted a formal request to the United States for the extradition of former president Martinelli. On June 12, 2017, former president Martinelli was arrested in the Coral Gables, Florida and detained in a federal detention center in Miami, Florida. On August 31, 2017, a United States magistrate judge of the U.S. District Court for the Southern District of Florida issued an order certifying the extradition of former president Martinelli and committing Martinelli to the custody of the U.S. Marshall, to be held at the federal detention center in Miami, Florida or another suitable facility pending final disposition of the matter by the U.S. Secretary of State to the designated agents of the Government of Panama.

D-5

In January and February 2017, the Supreme Court opened two new investigations against former President Ricardo Martinelli. In January 2017, the Supreme Court opened an investigation into accusations that former President Martinelli attempted to extort Impregilo, an Italian construction company, to pay for the construction of a hospital in Veraguas province. In February 2017, the Supreme Court opened an investigation into accusations that former President Martinelli embezzled funds from loan disbursements totaling U.S.$30 million made by the Social Security Fund to HPC Contratas P&V, contractor for the Amador Convention Center construction project. The Supreme Court has opened a total of nine investigations against former President Martinelli, which are based on allegations of (i) extortion of Impregilo, (ii) embezzlement of funds from loan disbursements made by the Social Security Fund, (iii) irregularities in the purchase of dehydrated foods under the former Programa de Ayuda Nacional (“National Assistance Program”); (iv) illegal telephone wiretapping; (v) irregularities in the purchase of grains under the former National Assistance Program; (vi) insider trading of shares in Petaquilla Minerals Ltd.; (vii) crimes against the public administration (acceptance of bribes); (viii) unlawful issuance of 353 pardons; and (ix) unlawful conduct in connection with an alleged usurpation of lands in Veraguas province. The investigations have not resulted in charges against former President Martinelli, which require his presence in Panama.

In the Assembly, 26 of the 71 seats belong to the Partido Revolucionario Democrático (“PRD”), 24 seats belong to Cambio Democrático, 16 seats belong to the Partido Panameñista, two seats belong to the Partido Molirena, one seat belongs to Partido Popular, one seat belongs to Partido Alianza and one representative has no party affiliation. On July 1, 2017, Congresswoman Yanibel Abrego, of the Cambio Democrático party, was elected President of the National Assembly for the 2017–2018 period. Congressman Jorge Ivan Arrocha, of the Partido Panameñista party, and Congressman Edwin Zuñiga, of the Cambio Democrático party, were elected as the first and second Vice Presidents of the National Assembly, respectively.

On August 7, 2017, the National Assembly confirmed the appointments of Roxana Cardenas as the new CEO of the Empresa Nacional de Autopistas (National Highways Company, “ENA”) and Jorge Luis Gonzalez, Presidential Goals Secretary, as the representative of the Executive Branch on the board of directors of the National Water Institute, IDAAN.

On July 31, 2017, Manuel Grimaldo, former Vice Minister of Interior Commerce and Industries, was appointed as the General Manager of the Colon Free Zone. Mr. Grimaldo succeeds Surse Pierpoint, who was appointed to serve as an advisor for development projects at Tocumen International Airport. The National Assembly confirmed Mr. Grimaldo in the position on August 7, 2017.

On July 6, 2017, Mr. Gilberto Ferrari was appointed as the new General Manager of Empresa de Transmisión Eléctrica Panameña (Panamanian Electric Transmission Company, ETESA). Mr. Ferrari succeeds Oscar Rendoll, who served as interim general manager of ETESA after Mr. Iván Barria resigned following the occurrence of two blackouts in less than a week in March 2017.

On March 31, 2017, Mirei Endara resigned as Minister of Environment, citing personal reasons. Ms. Endara was the first person to serve in this position, following the establishment of the Ministry of Environment in 2015. As of September 2017, Mr. Emilio Sempris is serving as Acting Minister of Environment.

On January 4, 2017, Alfredo Juncá was elected Magistrate of the Electoral Tribunal for a period of ten years. Mr. Juncá succeeded Erasmo Pinilla, who served in the position for twenty years.

On January 3, 2017, President Varela announced the appointment of Maria Luisa Romero as Minister of Government. Minister Romero succeeded Milton Henriquez, who resigned upon being appointed Ambassador to Spain. On January 3, 2017, President Varela also announced the appointment of Carlos Rubio as Vice Minister of Government, the position held by Ms. Romero prior to her appointment as Minister of Government.

Recent Government Actions

On September 18, 2017, the Assembly approved Bill No. 509 to raise the property tax exemption for principal residences or familial tax patrimony from U.S.$30,000 to U.S.$120,000 (with this upper limit subject to revision every five years). For principal residences or familial tax patrimony, Bill 509 then sets forth property tax rate brackets of 0.5% from U.S.$120,001 to U.S.$700,000 and 0.7% above U.S.$700,000. For commercial and industrial properties, second residences, and other properties, Bill No. 509 provides a tax exemption for the first U.S.$30,000, followed by brackets of 0.6% for U.S.$30,001 to U.S.$250,000; 0.8% for U.S.$250,001 to U.S.$500,000; and 1.0% above U.S.$500,000. In addition, Bill No. 509 provides a three-year property tax exemption for registered purchases of first homes with a value of up to U.S.$300,000 and imposes tax withholding obligations on mortgage providers for commercial and industrial properties and second residences.

D-6

On August 23, 2017, the Assembly passed Bill No. 305, which would reform the procurement law. Bill No. 305 provides for the elimination of abbreviated public contracts, international certification of insurers and obligations to train personnel, among other reforms.

On August 8, 2017, the Minister of Agriculture, Eduardo Carles, announced an increase in import tariffs on milk derivatives from 15% to 30%. The measure returns the tariff to its historical levels, prior to a reduction that was implemented in 2012.

On August 8, 2017, the Executive Branch, through Cabinet Decree No. 82, approved the creation of the Empresa Pública de Saneamiento de Panamá (National Sanitation Public Enterprise). This new state-owned enterprise will manage the sewage systems in the districts of Panama, San Miguelito, Arraiján and La Chorrera.

On August 1, 2017, the Public Ministry of the Republic of Panama announced that it had entered into a cooperation agreement with Odebrecht, pursuant to which Odebrecht will pay a fine of U.S.$220 million to the Government and will provide certain information related to embezzlement and bribery charges. Of the total fine, U.S.$100 million relates to use of the financial sector for irregular purposes.

On July 26, 2017, the Minister of Economy and Finance presented to the National Assembly the 2018 budget bill. The proposed national budget for 2018, totaling U.S.$23,397.1 million, would represent an increase of 7.9% compared to the 2017 national budget.

In July 2017, Executive Decree No. 86 extended for six additional months the temporary price caps on 22 products that are part of the family food basket; these price caps were first imposed by Executive Decree No. 165 of July 1, 2014 and, since then, have been extended continuously in six-month intervals, with certain adjustments. The price caps apply throughout the national territory except for Darien province and the island territories (which may be subject to a later determination). Thirteen items have been assigned a maximum price and nine have been assigned both a maximum price and a maximum gross margin of sale, ranging from 10% to 15%. As to each of those nine items, retailers have an obligation to sell at least one brand at the maximum price and the rest of the brands at the maximum gross margin of sale. The Decree created a Price Adjustment Commission, comprised of the Ministers of Commerce and Industry, Agricultural Development and Economy and Finance, which evaluates price adjustment requests from companies or producers’ associations. This Commission was authorized to adjust prices on the regulated products in response to market conditions. Retailers that offer the remaining 28 products that are part of the family food basket listed in the Decree are required to give advance notice to the Authority for Consumer Protection and Defense of Competition of any increase in the retail price of any of these products.

On June 13, 2017, Panama established official diplomatic relations with the People’s Republic of China. On the same date, Panama terminated diplomatic relations with the Republic of China, Taiwan. On September 13, 2017, Mr. Francisco Carlo Escobar Pedreschi presented his credentials as Panama’s ambassador to the People’s Republic of China.

In March 2017, the Cabinet Council approved modifications and amendments to Law No. 76 of 2009, which provides for measures intended to promote and develop industry. The modifications and amendments establish a National Industrial Competitiveness Program, which includes initiatives designed to strengthen human capital and to finance and develop micro, small, and medium enterprises. An industrial competitiveness program is intended to coordinate institutional actors and the private sector for the design and execution of plans to develop the industrial sector and to promote exports through initiatives related to market promotion, food safety, and human capital.

In March 2017, President Varela signed Law No. 389, which amends Law No. 40 of 2010 to provide students attending private schools up to U.S.$270 per school year for primary education expenses; U.S.$360 per school year for middle school expenses; and U.S.$450 per school year for high school expenses. More than 75,000 students from private schools in Panama whose tuition and monthly payments do not exceed U.S.$2,000 per year may receive the scholarship.

D-7

In February 2017, the Assembly approved Panama’s accession to the Convention on Mutual Administrative Assistance in Tax Matters (“MAC”) that Panama had signed in October 2016. By acceding to the MAC, the number of jurisdictions with which Panama may formally exchange information increases from 30 to 107.

In February 2017, Executive Decree No. 001–17 extended increases to import tariffs on certain flowers, coal, clinker (cement), and garments, which had been initially imposed in August 2016. The increased tariffs, which will not apply to imports that qualify for certain preferential tariff rates, are scheduled to expire on December 31, 2017. In March 2017, Executive Decree No. 001–17 was amended to increase tariffs on certain additional products, including coffee, wood boards, paper towel, aluminum and certain wires and cables; this amendment also will not apply to imports that qualify for certain preferential tariff rates.

Law No. 4 of February 17, 2017 reformed the Judicial Code, the Criminal Code, and the Code of Criminal Procedure. Law No. 4 addresses policies related to extradition, penitentiary overcrowding, and criminal prosecution and seeks to conform Panamanian criminal procedures with international standards. Law No. 4 includes provisions concerning prison conditions, earned time programs, rehabilitation programs, clemency policies, social integration of former prisoners and judicial efficiency.

In January 2017, the Government published for the first time a “National Risk Evaluation for the Prevention of Money Laundering and Financing of Terrorism.” The analysis identifies the risk level of money laundering in connection with different economic activities to inform the development of appropriate public policies and to direct resources effectively. The report concluded that internal crime is a source of money laundering in Panama; Panama is vulnerable to money laundering from overseas crime; and that some services and juridical structures in Panama could be abused abroad for money laundering. The report also concluded that the financing of terrorism is a low risk in Panama, in part due to the legal framework and institutional capacity.

In January 2017, the Government requested cancellation of a contract with Odebrecht for development of the Hydroelectric Project Chan II. In February 2017, Odebrecht accepted an action plan proposed by the Government to cancel the contract. The Government estimates that construction by a new contractor could require up to three years.

On April 3, 2016, international media published reports regarding an investigation by the International Consortium of Investigative Journalists (the “ICIJ”), the German newspaper Süddeutsche Zeitung and several of their media partners relating to confidential offshore financial arrangements revealed by documents leaked from Mossack Fonseca & Co., a law firm that is based in Panama. As a result of these media reports, on April 8, 2016, the French government added Panama to its list of Non-Cooperative States and Territories for French tax purposes. On May 9, 2016, the ICIJ published a database containing the financial and attorney-client communications that reportedly were leaked from Mossack Fonseca & Co., which involve 214,488 offshore entities in more than 200 countries and territories. The disclosure has had significant consequences for politicians and high profile individuals from around the world whose confidential financial arrangements were made public. In July 2016, the U.S. Department of Justice reportedly began to investigate whether employees of Mossack Fonseca knowingly participated in money laundering and tax evasion. In response to the disclosure and public criticism that followed, on April 29, 2016, Panama established a special independent committee composed of national and international experts, such as Nobel economics laureate Joseph Stiglitz, to evaluate existing practices and to propose measures to assist Panama in combatting international tax evasion and to strengthen Panama as a global financial center with best practices concerning transparency. Additionally, the Attorney General instructed Javier Carballo, an organized crime public prosecutor, to investigate whether any illegal behavior took place in relation to the activities of Mossack Fonseca & Co. On August 5, 2016, Joseph Stiglitz and Eric Pieth resigned from the special independent committee, expressing concerns relating to the transparency of the work of the committee. In November 2016, the committee delivered its report to the Government with recommendations to protect the integrity of the international logistics and corporate and financial services sectors in Panama.

The Economy

In the first six months of 2017, estimated GDP growth was 5.8%, compared to 4.9% for the same period in 2016. Inflation, as measured by the average CPI with base year 2013, was 0.7% in the first six months of 2017. At the end of the first quarter of 2017, the unemployment rate was 5.6%, the same as that of the first quarter of 2016.

The transportation, storage and telecommunications sector increased by an estimated 12.6% for the first six months of 2017 compared to the same period in 2016, primarily due to an increase in the operations of the Panama Canal, air transportation and ports.

D-8

Mining activities increased by 8.1% in the first six months of 2017 compared to the same period in 2016, reflecting a contribution of 1.8% of GDP, due to the increase of demand of raw materials for the construction industry. The construction sector grew 8.1% in the first six months of 2017 compared to the same period in 2016, primarily due to the execution of public and private projects, and its contribution to GDP increased from 16.5% in the first six months of 2016 to 16.9% for the same period in 2017. The financial intermediation sector grew by 3.1% in the first six months of 2017 compared to the same period in 2016 and represented a contribution of 7.7% of GDP in the first six months of 2017, a decrease from 7.9% for the same period in 2016. Growth in financial intermediation sector was attributable mainly to banking activity.

The Central Government’s current savings for the first six months in 2017 registered a surplus of U.S.$477 million (0.8% of nominal GDP) compared to a surplus of U.S.$474 million for the same period in 2016 (0.9% of nominal GDP). The Government’s overall deficit decreased from U.S.$1.1 billion in the first six months of 2016 (2.1% of nominal GDP) to a deficit of U.S.$1.0 billion for the same period in 2017 (1.7% of nominal GDP). In the first six months of 2017, Panama’s non-financial public sector balance registered a deficit of U.S.$226 million (0.4% of nominal GDP), an increase from a deficit for the same period in 2016 of U.S.$122 million (0.2% of nominal GDP).

Estimated nominal GDP for 2016 was U.S.$55,187.8 million, representing 4.9% growth compared to preliminary nominal GDP for year 2015 of U.S.$52,132.3 million. Inflation in 2016, as measured by the Panamanian consumer price index, was 0.7%.

In 2016, Panama’s real GDP grew by an estimated 4.9%, compared to 5.8% in 2015. Inflation, as measured by the average CPI with base year 2013, was 0.7% in 2016. The Central Government’s current savings for 2016 registered a surplus of U.S.$1.39 billion (2.5% of nominal GDP), compared to a surplus of U.S.$1.21 billion in 2015 (2.3% of nominal GDP). The Government’s overall deficit increased to U.S.$2.2 billion in 2016 (4.0% of nominal GDP) from U.S.$2.0 billion in 2015 (3.9% of nominal GDP). In 2016, Panama’s non-financial public sector balance registered an adjusted deficit of U.S.$0.8 billion (1.5% of nominal GDP), a decrease from an adjusted deficit of U.S.$1.0 billion (2.0% of nominal GDP) in 2015.

The agriculture sector decreased an estimated 0.1% in 2016, compared to 2015, in part due to due to a decrease in production of vegetables, bananas, pineapple, and muskmelon. The fisheries sector decreased an estimated 8.4% in 2016, compared to 2015, primarily due to the decrease in fishing of commercial species, which resulted in less exports of fresh fish and shrimp. Commerce increased an estimated 3.3% in 2016, compared to 2015, as a result of increased sales of fuel and similar products, beverages, food and tobacco. The hotels and restaurant sector increased an estimated 2.2% in 2016, compared to 2015, primarily due to increased performance of services in restaurants. The real estate sector increased an estimated 4.7% in 2016, compared to 2015, primarily due to an increased level of sale activities in the residential sector, which increased by 3.2%.

The Assembly approved Panama’s 2017 budget on October 26, 2016. The 2017 budget contemplates total expenditures of U.S.$21.7 billion, with budget estimates based on an anticipated nominal GDP of U.S.$58.6 billion (5.8% real growth from 2016) and an anticipated consolidated non-financial public sector deficit of approximately U.S.$585 million (approximately 1.0% of estimated nominal GDP) for 2017. The corresponding fiscal deficit permitted under the Social and Fiscal Responsibility Law is approximately U.S.$585 million. Compliance with the Social and Fiscal Responsibility Law is assessed only against year-end results. Due to the seasonality of revenue receipts and year-end dividend payments, fiscal results expressed as a percentage of GDP have historically improved during the second half of the fiscal year. The 2017 budget allocates public recurrent and capital expenditures as follows: 41.6% to the social services; 17.2% to financial services; 15.9% to general services; 12.3% to infrastructure development; 2.3% to development and promotion of production; 1.0% to environment and technology; and 9.7% to other services. Investment for 2017 includes ongoing projects, such as Metro Line 2, the fourth bridge over the Canal, and Ciudad Esperanza (City of Hope, an urban housing project in the Arraiján district of Panama Oeste province for the construction of public housing and community amenities, such as a school, police station, recreation and sports facilities, a business plaza and public offices), and new projects, such as construction of the Technical Institute for Higher Education, Renovación Urbana de Colón (Colón Urban Renewal), and road construction on Panamerican highway between La Chorrera and San Carlos.

The preliminary fiscal deficit of the non-financial public sector for the first six months of 2017 was approximately U.S.$226 million (0.4% of nominal GDP). Article 10 of the Social and Fiscal Responsibility Law, as amended by Law No. 38 of 2012, establishes a ceiling for the adjusted deficit of the non-financial public sector of 1.0% of nominal GDP projected in the budget for the 2017 fiscal year.

D-9

The preliminary fiscal deficit of U.S.$226 million for the non-financial public sector deficit for the six-month period ended on June 30, 2017 represented an increase of U.S.$104 over the deficit of U.S.$122 million registered for the same period of 2016. Total non-financial public sector expenditures for the six-month period ended June 30, 2017 were U.S.$5.9 billion, an increase of U.S.$57 million (1.0%) from U.S.$5.8 billion. Total revenue for the six-month period ended on June 30, 2017 was U.S.$5.6 billion, a decrease of U.S.$47 million (0.8%) from U.S.$5.7 billion for the same period of 2016.

On the expenditure side, non-financial public sector capital expenses totaled U.S.$1,537 million for the first six months of 2017, a decrease of U.S.$151 million (8.9%) compared to U.S.$1,688 million during the same period of 2016. Non-financial public sector current expenses during the six-month period ended on June 30, 2017 amounted to U.S.$4.3 billion, a U.S.$208 million (5.1%) increase from U.S.$4.1 billion during the same period of 2016. On the revenue side, tax revenue during the first six months of 2017 was U.S.$2.9 billion, an increase of U.S.$50 million (1.8%) from U.S.$2.8 billion during the first six months of 2016, while non-tax revenue was U.S.$652 million, an increase of U.S.$13 million (2.0%) from U.S.$639 million for the same period in 2016. Capital revenue during the first six months of 2017 was nil.

Public Debt

As of August 31, 2017, total public debt was U.S.$23,054.4 million. Internal public debt accounted for 22% of total debt, while external public debt accounted for 78% of total debt. The average maturity of the debt portfolio as of August 31, 2017 was 11.3 years, with an average duration of 7.9 years. As of June 30, 2017 local secondary market transactions reached U.S.$355.0 million.

As of December 31, 2016, total public debt was U.S.$21,601.6 million. Internal public debt accounted for 22.2% of total debt, while external public debt accounted for 78.2% of total debt. The average maturity of the debt portfolio as of December 31, 2016 was 10.8 years, with an average duration of 7.7 years. During 2016, Treasury note and Treasury bond issuances totaled U.S.$1,016.2 million and local secondary market transactions reached U.S.$1,266.9 million.

Primary market transactions during 2016 included the issuance of U.S.$698.5 million of Treasury Bonds due 2024 and U.S.$317.7 million of Treasury Notes due 2019. Primary market transactions during the first nine months of 2017 included the issuance of U.S.$352.0 million of Treasury Bonds due 2024.

On May 15, 2017, Panama conducted a liability management transaction involving an issuance of U.S.$1,168,292,000 aggregate principal amount of its 4.500% Global Bonds due 2047; a reopening and issuance of U.S.$253,988,000 aggregate principal amount of its 3.875% Global Bonds due 2028; and a purchase by Panama of U.S.$345,473,000 aggregate principal amount of its 5.200% Global Bonds due 2020. Following the transaction, the aggregate outstanding principal amount of Panama’s 5.200% Global Bonds due 2020 was reduced from U.S.$1,500,000,000 to U.S.$1,154,527,000. On March 10, 2016, Panama issued U.S.$1.0 billion aggregate principal amount of its 3.875% Global Bonds due 2028.

IMF Relationship

Panama is a member of the International Monetary Fund (“IMF”). Under Article IV of the IMF’s Articles of Agreement, the IMF holds bilateral discussions with its member countries, usually every year, to assess their economic health. The IMF Executive Board concluded its most recent Article IV consultation with Panama on May 1, 2017.

The Panama Canal

The Canal plays a significant role in the Panamanian economy. In the Panama Canal Authority (“PCA”) 2016 fiscal year ending on September 30, 2016, Canal transits decreased to 13,114 from 13,874 in fiscal year 2015, while cargo tonnage in fiscal year 2016 decreased to 204.7 million long tons from 229.1 million long tons in fiscal year 2015. According to the PCA, toll revenues for fiscal year 2016 reached U.S.$1,933.0 million, a decrease of 2.9% compared to U.S.$1,991.3 million in fiscal year 2015.

On average, from the Canal’s fiscal year 2012 to the fiscal year 2016, transits through the Canal decreased by 2.2% and cargo tonnage decreased by 1.5%. Factors such as the development of alternative land routes and the increasing size of vessels transiting the Canal have contributed to the decrease in the number of vessels required to transport cargo between 2012 and 2016. However, on average, from fiscal year 2012 to fiscal year 2016, toll revenues have increased by 2.3% per annum, primarily due to an increase in toll rates. In fiscal year 2016, the PCA had a surplus of approximately U.S.$1,163.4 million, a decrease of 14.5% compared to U.S.$1,360.8 million in 2015.

D-10

On September 18, 2017, the Assembly approved the PCA’s budget for its fiscal year ending on September 30, 2018. This budget assumes an increase of 3.9% in transit revenues and an increase of 6.0% in total operating income and projects that dividends to the Central Government at the end of the year will increase by 3.2% from U.S.$1,141 million budgeted for the 2017 fiscal year to U.S.$1,178 million budgeted for the 2018 fiscal year.

In August 2017, the Cabinet Council approved modifications to the Canal tolls structure, pursuant to recommendations from the PCA Board of Directors. The approved adjustments will apply to all market segments and are scheduled to take effect on October 1, 2017. For the container carrier segment, the revised tolls structure will offer reduced rates on containers that are loaded on their return trip; this opportunity will be available to neopanamax vessels taking round-trip passages through the Canal, provided that: (1) the vessel has a use rate of at least 70% in the northern transit, and (2) the time between north and south transit does not exceed twenty-eight days. The revised structure also modifies tolls for ships carrying liquefied natural gas or liquefied petroleum gas. In addition, “container ships / loose cargo in bulk” were reclassified from the “other” segment to the “general cargo” segment, which is expected to result, typically, in lower rates for clients in this category.

On June 26, 2016, the PCA completed an expansion project involving the construction of a third set of locks. The project was authorized by the Assembly in July 2006 pursuant to a U.S.$5.25 billion expansion plan, which was approved in a national referendum held in October 2006. In July 2009, a contract for construction of the third set of locks was awarded to the Grupo Unidos por el Canal (“GUPCSA”) consortium, composed of Sacyr Vallehermoso, S.A., Impregilo S.p.A., Jan de Nul n.v., and Constructora Urbana, S.A., for a total base price of approximately U.S.$3.1 billion. Pursuant to the construction contract, disputes arising from the project may be submitted to a Dispute Adjudication Board (“DAB”), whose determinations may be challenged under the International Chamber of Commerce (“ICC”) Rules of Arbitration. As of March 2017, claims by GUPCSA against the PCA totaled approximately U.S.$6.06 billion; these claims are in different stages of the conflict resolution process established under the contract.

In January 2016, the DAB issued two decisions regarding certain claims by GUPCSA. One of the DAB decisions denied all claims presented by GUPCSA in respect of labor costs and benefits arising from an agreement between the Panamanian Chamber of Construction and a construction union. In the second DAB decision, GUPCSA claimed labor costs associated with time extensions granted in previous decisions on claims concerning concrete, basalt and a strike by construction union members based on a contractual clause pertaining to scaling of manual labor costs; the DAB awarded GUPCSA U.S.$24.6 million on this claim. In July 2016, the DAB issued three decisions. In one decision, the DAB denied claims by GUPCSA for U.S.$99.0 million and a 76-day contract extension in connection with additional costs that resulted from allegedly unforeseeable and adverse conditions in the Pacific Site. In the two other decisions, the DAB awarded U.S.$6.4 million and U.S.$0.4 million for claims based on certain laboratories and the drainage of certain lagoons. In six other decisions issued in 2016, the DAB recognized U.S.$56.6 million of claims by GUPCSA, which had petitioned for U.S.$119.0 million in the six disputes; the PCA reserved its right to submit these DAB decisions to ICC arbitration. In December 2016, the PCA received from GUPCSA two new requests for ICC arbitration with claims totaling U.S.$2.4 billion; GUPCSA subsequently instituted the two arbitrations with the ICC.

In January 2017, the DAB issued a ruling on a claim by GUPCSA for U.S.$114.0 million based on cost overruns related to the quality and quantity of basalt, the availability of sites for disposal of excavated material and the physical conditions in the area where the water basins were built. The DAB’s ruling recognized U.S.$4.0 million of the claim, due to physical conditions of the water basin area, while the other components of the claims were denied. In July 2017, an ICC arbitral tribunal issued a decision dismissing each claim concerning a temporary cofferdam, which had totaled U.S.$218 million, while also awarding to the PCA more than U.S.$22.9 million in costs and expenses from the arbitration proceeding.

According to the PCA, as of September 30, 2016, 224 neopanamax ships had traversed the expanded Canal, including ships carrying liquid natural gas and liquid petroleum gas. One official incident had been registered as of September 30, 2016, which had not led to any claims on behalf of the ship. On September 5, 2017, the PCA announced its objective to increase the number of daily scheduled transits by neopanamax vessels from six to seven as of December 1, 2017, and then to reach eight daily scheduled transits by neopanamax vessels in early 2018.

In July 2017, the Panama Canal launched an environmental recognition program, “Green Connection,” to recognize clients that demonstrate excellent environmental management and to encourage others to implement technologies and standards that reduce emissions. The program includes an Environmental Premium Ranking and a Green Connection Award.

D-11

In May 2016, construction of the first electricity generation plant in Central America based on liquefied natural gas commenced on Telfers Island, in the province of Colón. The project represents an investment of U.S.$1,150 million and is expected to add 381 MW to the country’s energy matrix as part of the National Energy Plan 2015-2050 and to include a regasification terminal with a storage capacity of 180,000 m3. The plan also contemplates the possibility of converting Panama into a distribution hub for liquefied natural gas for the region. The plant is expected to be operational in 2018.

The PCA administers the “Bridge over the Panama Canal in the Atlantic Sector Project,” which was authorized by Law 28 of July 17, 2006 and consists of the design and construction of a concrete vehicular bridge and access roads, with a total length of approximately 4,605 meters and four lanes, in the province of Colón. The project contemplates a connection from the western on-ramp of the new bridge with an existing road commonly known as “Costa Abajo de Colon” and includes a bridge over the Chagres river, downstream of the Gatún landfill. As of March 31, 2017, the PCA had awarded U.S.$410.2 million in contracts for the project, including a U.S.$379.7 million contract with Puente Atlántico, S.A. for construction of the bridge over the Panama Canal.

D-12

TABLE NO. 1

Selected Panamanian Economic Indicators(1)

The following table sets forth Panama’s principal economic indicators for the years 2012 through 2016:

| | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | |

| | | 2012(R) | | | 2013(R) | | | 2014(P) | | | 2015(P) | | | 2016(P) | |

Economic Data: | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | |

GDP (millions, nominal dollars) | | $ | 39,955 | | | $ | 44,856 | | | $ | 49,166 | | | $ | 52,132 | | | $ | 55,188 | |

GDP (millions, constant dollars)(2) | | $ | 29,873 | | | $ | 31,852 | | | $ | 33,780 | | | $ | 35,732 | | | $ | 37,472 | |

GDP (% change, constant dollars)(2) | | | 9.2 | % | | | 6.6 | % | | | 6.1 | % | | | 5.8 | % | | | 4.9 | % |

Service Sector (% change, constant dollars)(2)(3) | | | 6.9 | % | | | 3.5 | % | | | 4.5 | % | | | 6.3 | % | | | 4.6 | % |

Other (% change, constant dollars)(2)(4) | | | 17.6 | % | | | 17.5 | % | | | 10.8 | % | | | 3.7 | % | | | 5.7 | % |

GDP Per Capita (constant dollars)(2) | | $ | 7,887 | | | $ | 8,272 | | | $ | 8,632 | | | $ | 8,988 | | | $ | 9,282 | |

Population (millions) | | | 3.79 | | | | 3.85 | | | | 3.91 | | | | 3.98 | | | | 4.04 | |

CPI – Period Average (% change) | | | 5.7 | % | | | 4.0 | % | | | 2.6 | % | | | 0.2 | % | | | 0.7 | % |

Unemployment | | | 4.1 | % | | | 4.1 | % | | | 4.8 | % | | | 5.1 | % | | | 5.5 | % |

Public Finance: | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | |

Total Consolidated Non-Financial Public Sector Revenues (millions) | | $ | 9,013 | | | $ | 9,950 | | | $ | 10,225 | | | $ | 10,656 | | | $ | 11,609 | |

Total Consolidated Non-Financial Public Sector Expenditures (millions)(5) | | $ | 9,564 | | | $ | 10,976 | | | $ | 11,778 | | | $ | 11,880 | | | $ | 12,674 | |

Overall Surplus (Deficit) (millions) | | $ | (551 | ) | | $ | (1,026 | ) | | $ | (1,563 | ) | | $ | (1,042.6 | ) | | $ | (1,064.9 | ) |

As % of Current GDP | | | (1.4 | )% | | | (2.3 | )% | | | (3.2 | )% | | | (2.0 | )% | | | (1.9 | )% |

Central Government Surplus (Deficit) (millions) | | $ | (1,029 | ) | | $ | (1,690 | ) | | $ | (1,945 | ) | | $ | (2,026 | )% | | $ | (2,203 | ) |

As % of Current GDP | | | (2.6 | )% | | | (3.8 | )% | | | (4.0 | )% | | | (3.9 | )% | | | (4.0 | )% |

Public Debt (at December 31): | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | |

Internal Debt (millions) | | $ | 3,483 | | | $ | 3,453 | | | $ | 3,879 | | | $ | 4,573 | | | $ | 4,700 | |

External Debt (millions) | | $ | 10,782 | | | $ | 12,231 | | | $ | 14,352 | | | $ | 15,648 | | | $ | 16,902 | |

Public Debt (as % of Current GDP) | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | |

Internal Debt | | | 8.7 | % | | | 7.7 | % | | | 7.9 | % | | | 8.8 | % | | | 8.5 | % |

External Debt | | | 27.0 | % | | | 27.3 | % | | | 29.2 | % | | | 30.0 | % | | | 30.6 | % |

Total Public Debt (millions) | | $ | 14,265 | | | $ | 15,684 | | | $ | 18,231 | | | $ | 20,222 | | | $ | 21,602 | |

Trade Data: | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | |

Exports (f.o.b.) Goods(6)(7) (millions) | | $ | 18,271 | | | $ | 17,057 | | | $ | 15,333 | | | $ | 12,784 | | | $ | 11,705 | |

Imports (c.i.f.) Goods(6)(7) (millions) | | $ | (28,140 | ) | | $ | (26,597 | ) | | $ | (25,710 | ) | | $ | (22,492 | ) | | $ | (20,490 | ) |

Goods Trade Balance(7) (millions) | | $ | (9,869 | ) | | $ | (9,540 | ) | | $ | (10,337 | ) | | $ | (9,709 | ) | | $ | (8,785 | ) |

Current Account Surplus(7) (Deficit) (millions) | | $ | (3,816 | ) | | $ | (4,401 | ) | | $ | (4,794 | ) | | $ | (3,377 | ) | | $ | (3,098 | ) |

Overall Balance of Payments Surplus (Deficit)(7) (millions) | | $ | (958 | ) | | $ | (109 | ) | | $ | 380 | | | $ | (1,117 | ) | | $ | (1,233 | ) |

Total Official Reserves (at December 31) (millions) | | $ | 2,137 | | | $ | 2,412 | | | $ | 3,509 | | | $ | 3,044 | | | $ | 3,540 | |

| (1) | All monetary amounts in millions of U.S. dollars at current prices, unless otherwise noted. |

| (2) | Constant GDP figures are based on 2007 constant dollars in chained volume measure. |

| (3) | Including real estate, public administration, commerce, restaurants and hotels, financial services, the CFZ, the Panama Canal, transportation and communications, public utilities and other services. |

| (4) | Including mining, manufacturing, agriculture and construction. |

| (5) | Including interest payments. |

| (7) | Figures have been calculated pursuant to the fifth edition of the IMF Balance of Payments Manual. |

D-13

Sources: Directorate of Analysis and Economic Policies, Office of the Comptroller General, Banco Nacional de Panamá (“BNP”) and Ministry of Economy and Finance.

D-14

THE REPUBLIC OF PANAMA

Area and Population

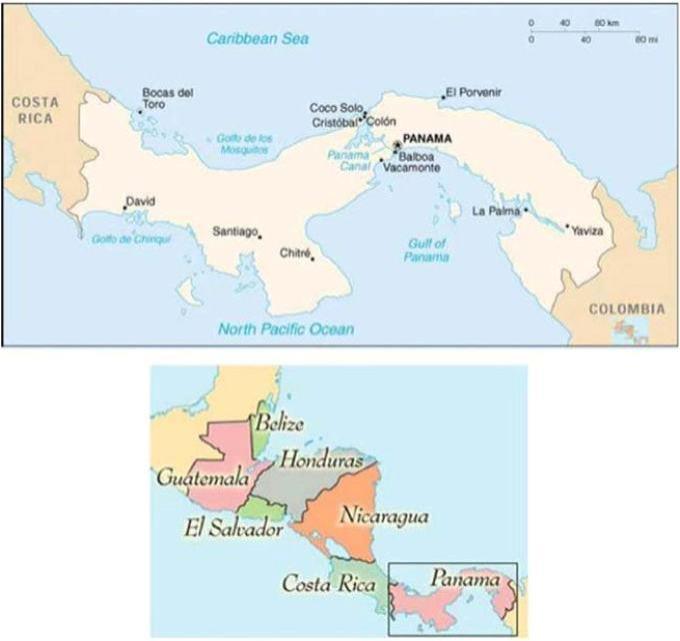

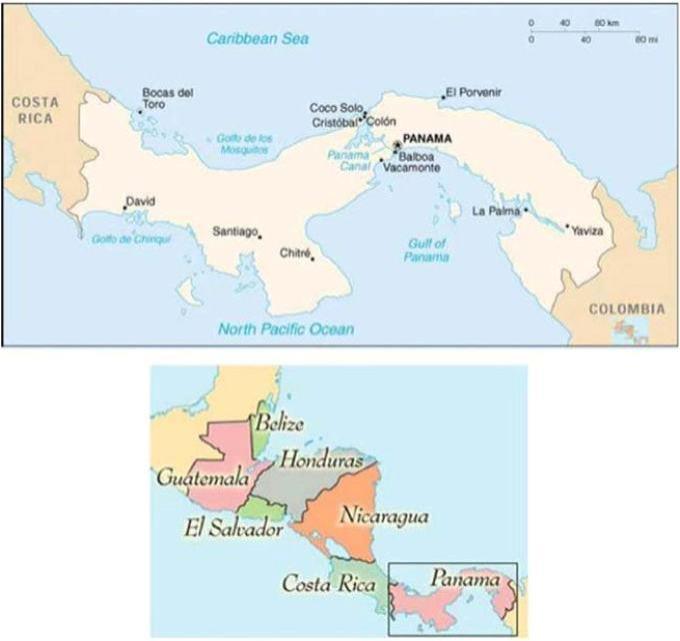

Panama is a republic located on the narrowest point of the Central American isthmus, which connects the continents of North America and South America. It has a coastline of approximately 1,868 miles on the Caribbean Sea and Pacific Ocean and is bordered on the east by Colombia and on the west by Costa Rica. Panama has a national territory of approximately 29,157 square miles situated within its coastline and 345 miles of land borders, and includes numerous coastal islands. The Panama Canal, one of the most important commercial waterways in the world, which connects the Atlantic and Pacific Oceans, bisects the country running northwest to southeast. Panama’s climate is primarily tropical.

As of December 31, 2016, Panama had an estimated population of 4.0 million and a population density of 54.4 people per square kilometer. At December 31, 2016, Panama Province, the Republic’s largest province, was estimated to comprise 52.2% of Panama’s total population. Colón Province, located at the northern terminus of the Panama Canal, was estimated to comprise 7.0% of the total population.

During the period from 2012 to 2016, the population grew by an average of 1.6% per annum. Approximately 64.6% of Panama’s population lives in cities and towns with more than 1,500 inhabitants, and 6.4% of the population is indigenous, some of whom are seeking greater autonomy from the Government. Of the Panamanian population, 27.1% is under 15 years of age, 65.1% is between the ages of 15 and 64, and 7.8% is over the age of 65. Average life expectancy in Panama is 77.9 years. The infant mortality rate is estimated at 14.5 per 1,000 births. Panama’s official language is Spanish.

In 2016, Panama’s preliminary GDP in chained volume measure grew by approximately 4.9% compared to 5.8% in 2015. Inflation, as measured by the average CPI with base year 2013, was 0.7% in 2016. The Central Government’s current savings for 2016 registered a surplus of U.S.$1.39 billion (2.5% of nominal GDP) compared to a surplus of U.S.$1.21 billion in 2015 (2.3% of nominal GDP). The Government’s overall deficit increased to U.S.$2.2 billion in 2016 (4.0% of nominal GDP) from U.S.$2.0 billion in 2015 (3.9% of nominal GDP). In 2016, Panama’s non-financial public sector balance registered an adjusted deficit of U.S.$0.8 billion (1.5% of nominal GDP), a decrease from an adjusted deficit of U.S.$1.0 billion (2.0% of nominal GDP) in 2015.

Panama’s preliminary per capita GDP for 2016, expressed in chained volume measure, was approximately U.S.$9,282.0. According to the 2010 census, education indicators show that Panama’s literacy rate for people over the age of ten years is approximately 94.5%. Estimates as of March 2016 show that 22.1% of the population is considered to be living in poverty while 9.9% is considered to be living in extreme poverty.

Historical Information

Panama gained independence from Spain in 1821 and subsequently joined the Confederation of Greater Colombia, from which Panama declared its independence on November 3, 1903. Several weeks after gaining independence, Panama signed the Hay/Bunau-Varilla Treaty with the United States, which, among other things, granted the United States the right to occupy a ten-mile wide zone and a concession for the construction, maintenance, operation and protection of the Panama Canal (the “Canal Zone”). See “The Panama Canal—General”.

Panama adopted its first constitution in 1904 and, between 1904 and 1968, Panama generally experienced social and political stability and economic growth under a constitutional democracy. During the period immediately following World War II, the Panamanian military interfered with the civilian government, although this interference largely ended by the mid-1950s. Constitutional government continued until October 1968, when the National Guard mounted a military coup and replaced the civilian government. Although the military made nominal efforts during the late 1970s to return to civilian government, the military generally remained in control of the Government until 1989.

Issues related to control of the Panama Canal and the Canal Zone caused considerable unrest in Panama. In 1977, following 13 years of negotiations, Panama signed treaties with the United States that provided for abolishing the Canal Zone in 1979 and the eventual turnover of the Panama Canal to Panama in 1999. See “The Panama Canal—The Canal Treaty of 1977”.

In 1983, General Manuel Antonio Noriega (“Noriega”) became Commander of the National Guard and assumed effective control of the Government. In the spring of 1987, a political crisis galvanized Noriega opponents and resulted in the formation of a major civilian protest and opposition movement widely supported by civilian organizations, political parties and the business community. This political crisis generated an economic crisis as well.

D-15

In response to the ensuing political crisis, in March 1988, the United States suspended its Agency for International Development (“AID”) programs to Panama and blocked preferential sugar quotas, causing further economic disruption. The United States imposed additional economic sanctions that year, including a freeze on all United States payments for the Panama Canal (at that time, approximately U.S.$6 million per month), an order prohibiting American citizens and companies from making payments to the Government and a freeze on all Government accounts (and certain additional assets) in the United States.

In December 1989, relations between Panama and the United States deteriorated, culminating in a United States military intervention that resulted in the removal of Noriega. Guillermo Endara (“Endara”), who had been elected by a significant majority of the popular vote earlier in the year, was subsequently sworn in as President.

Since the end of 1989, Panama has enjoyed political and economic stability under democratically elected governments.

Relations with the United States have been fully restored. Endara finished his presidential term and, in the spring of 1994, orderly national elections were held. Ernesto Pérez Balladares (“Pérez Balladares”), who was elected President with 33% of the vote in May 1994, finished his presidential term in August 1999. Mireya Moscoso (“Moscoso”), who was elected with 44.8% of the vote in May 1999, took office on September 1, 1999 and completed her presidential term on August 31, 2004. On May 2, 2004, Martín Torrijos (“Torrijos”) was elected President with 47.4% of the vote. He took office on September 1, 2004 and completed his presidential term on June 30, 2009. Ricardo Martinelli (“Martinelli”), who was elected President with 60.0% of the vote on May 3, 2009, took office on July 1, 2009 and completed his presidential term on June 30, 2014. President Martinelli was succeeded by President Varela.

The Panamanian military was disbanded in 1990 and, in 1994, by constitutional amendment, the military was abolished. Costa Rica, Panama’s western neighbor, also does not have a military. If Panama were attacked by a foreign force and the neutrality of the Panama Canal were jeopardized, the United States would have the right under treaties related to the Panama Canal to take measures to protect the neutrality of the Canal. The national police force of Panama also has certain defensive capabilities.

Form of Government and Political Parties

Panama is a republic with a representative form of government. In 1972, the original version of the current Constitution was adopted (the fourth in Panama’s history), setting forth the structure of the Government, individual and collective rights and duties, and the division of powers among the executive, legislative and judicial branches.

Executive power is vested in the President and the presidentially-appointed Ministers, who constitute the Cabinet. The President and the Vice President are each elected by direct, universal suffrage for a term of five years. The President and the Vice President may not be reelected to the same office within ten years after the expiration of their term. In the event the President is unable to finish a term, the Vice President would succeed to the presidency.

National legislative power is vested in the Assembly, Panama’s unicameral legislative body. The number of electoral districts, each comprising an average of approximately 63,010 persons, determines the number of legislators; as of August 2017, the Assembly had 71 seats. The full Assembly is elected by universal suffrage every five years. Members of the Assembly are not subject to limits on the number of terms in office to which they may be elected. The Assembly has, among other powers, the authority to enact legislation, ratify treaties, approve the budget and ratify the appointment of the Comptroller General, the Attorney General and justices of the Supreme Court of Justice (the “Supreme Court”). To be enacted, legislation must be approved after three separate readings by a majority of all legislators or by a majority of legislators present at the session, depending on the substance of the legislation being enacted. The President may veto bills adopted by the Assembly, but the Assembly may override presidential vetoes by a vote of two-thirds of its members. Pursuant to the Constitution, the Assembly may empower the President and the Cabinet to adopt legislation when the Assembly is not in session. The Assembly has the power to amend the Constitution. Amendments to the Constitution may be adopted either by a majority vote of all legislators in two different Assemblies or by a majority vote of all legislators in two sessions of the same Assembly and a public referendum.

On May 4, 2014, Panama held general elections for the offices of President, Members of the Assembly and other regional posts. The then incumbent Vice President, Juan Carlos Varela, was elected President with 39.08% of the vote obtained by the “El Pueblo

D-16

Primero” alliance composed of the Partido Popular and Partido Panameñista. President Varela took office on July 1, 2014. As of September 2017, of the 71 seats in the Assembly, 26 seats belong to the Partido Revolucionario Democrático (“PRD”), 24 seats belong to Cambio Democrático, 16 seats belong to the Partido Panameñista, two seats belong to the Partido Molirena, one seat belongs to Partido Popular, one seat belongs to Partido Alianza and one representative has no party affiliation. On July 1, 2014, President Juan Carlos Varela appointed Dulcidio De La Guardia as Minister of Economy and Finance. On July 1, 2014, Iván A. Zarak Arias was appointed Vice Minister of Economy and Eyda Varela de Chinchilla was appointed Vice Minister of Finance.

On December 3, 2013, then presidential candidate Varela announced the priorities of his administration in a Plan for the El Pueblo Primero Alliance. The Plan included, among other initiatives, implementation of price controls on basic foods to reduce the cost of living and initiatives to maintain the growth of the Panamanian economy through public investment projects, such as plans to provide potable water nationwide; to construct Metro lines 2 and 3 to San Miguelito and East and West Panama City; to construct 500 kilometers of new highways, 15 health centers and four hospitals; and to increase the coverage of the irrigation system from 20% to 40% of all cultivated land. The Plan also called for new rules to increase transparency in the government and to reduce corruption and cronyism. Programs under the Plan are in progress.

Judicial power is vested in the Supreme Court and various lower tribunals. The President appoints the nine justices of the Supreme Court for staggered ten-year terms, with two justices being selected every two years, subject to ratification by the Assembly. Lower court judges are appointed by the Supreme Court. The judicial branch prepares its own budget and sends it to the executive branch for inclusion in the general budget presented to the Assembly for approval. The Supreme Court is the final court of appeal and has the power to declare null and void laws, regulations or other acts of the executive or legislative branches that conflict with the Constitution.

Panama is administratively divided into ten provinces and three territories. In each province, executive power is exercised by a Governor who is appointed by the President. There are no provincial legislative or judicial bodies. Provincial governments do not have their own independent budgets. Within each province are municipalities that are, in turn, divided into precincts. Each municipality has a municipal council and a mayor who exercises executive power. Mayors and members of municipal councils are elected by direct, universal suffrage for five-year terms. Municipalities levy and collect municipal taxes and adopt their own budgets for financing local projects.

On October 20, 2015, the Assembly approved Law No. 66, which amended Law No. 37 of 2009, a law that decentralized certain aspects of public administration. Law No. 66 stated seven objectives: 1) to amend Law No. 37 of June 29, 2009, which decentralized public administration; 2) to reallocate property taxes between municipalities; 3) to establish a formula for the allocation of property tax for municipalities with less income; 4) to direct the investment of allocated funds to specific areas; 5) to replace the “Decentralizing National Authority” with a “National Secretariat of Decentralization”; 6) to establish an Investment Program for Public Works and Municipal Services and 7) to include special territories that do not have municipalities.

Foreign Affairs and International Organizations

Panama maintains diplomatic relations with 148 countries. Panama is a charter member of the United Nations (“U.N.”) and a member of various other international organizations, including the IMF and the Inter-American Development Bank (“IADB”). Panama is a founding member of the Organization of American States (“OAS”) and is also a member of the International Bank for Reconstruction and Development (“World Bank”) and the World Bank affiliates, including the International Finance Corporation (“IFC”) and the Multilateral Investment Guaranty Agency (“MIGA”) (collectively, the “World Bank Group”), as well as a member of the San José Pact, under which Venezuela and Mexico agreed to provide the Central American countries and four Caribbean countries with crude oil and petroleum products under preferential terms. On September 6, 1997, Panama acceded to membership in the World Trade Organization (“WTO”).

Panama consults with several international agencies, such as the World Bank Group and the IADB, regarding its economic program, objectives, projections and policies. In recent years, Panama has utilized the IADB and the World Bank Group for significant external financing. See “Public Sector Debt—External Debt”.

In 2010, the Assembly approved legislation implementing the Corporación Andina de Fomento (“CAF” or “Development Bank of Latin America”) agreement and Panama became a Series A country member. CAF is a development bank created in 1970 and owned by 19 sovereigns, 17 from Latin America and the Caribbean and Spain and Portugal, as well as by 13 private banks in the Latin America region. It promotes sustainable development through loans and grants, and support in the technical and financial structuring of projects in the public and private sectors of Latin America. As of December 31, 2016, the Republic had outstanding borrowings of U.S.$893.6 million from CAF. See “Public Sector Debt—External Debt”.

D-17

THE PANAMANIAN ECONOMY

General

Panama’s unique geographic position, service economy (including the Panama Canal) and monetary regime anchored on the use of the U.S. dollar as legal tender are major factors in Panama’s economic performance.

Panama has used the U.S. dollar as its legal tender since shortly after gaining its independence in 1903. The national currency, the Balboa, is used primarily as a unit of account linked to the U.S. dollar at a ratio of one dollar per one Balboa. The Government does not print paper currency, although a limited amount of coinage is minted. Panama’s monetary system is based on its Constitution (beginning with the 1904 Constitution, which established the Balboa) and Panamanian laws expressly recognizing the U.S. dollar as legal tender. There are no Panamanian foreign exchange controls or reporting requirements, and capital moves freely in and out of the country, without local currency risk. Under Panama’s unique monetary system, foreign exchange reserves are not needed to support the currency.

The absence of both a national printed currency and a Balboa exchange market diminishes the significance of the balance of payments as an indicator of the Government’s external debt service capacity. Fiscal policy, therefore, is a more relevant indicator of the accumulation and drawdown of Government reserves available for sovereign debt service. Moreover, this monetary system imposes an element of discipline on Panamanian authorities in the areas of monetary and fiscal policy. Panama is limited in its ability to conduct a stimulative monetary policy and can finance public sector deficits only through borrowing.

In 2012, the non-financial public sector registered a deficit of 1.4% of GDP. In 2013 the non-financial public sector registered a deficit of 2.3% of GDP and in 2014, the non-financial public sector deficit increased to 3.2% of GDP. In 2015, the non-financial public sector deficit fell back to 2.0% of GDP. In 2016, the non-financial public sector deficit fell to 1.5% of GDP.

From 2012 to 2016, Panama experienced an average annual rate of inflation, as measured by the average consumer price index (“CPI”), of 2.6%. In 2016, the annual rate of inflation, as measured by the average CPI with a base year of 2013, was estimated at 0.7%.

The Panamanian economy is dominated by a large service sector, which represented 75.1%, 72.9%, 71.9%, 72.2% and 72.0% of GDP in 2012, 2013, 2014, 2015 and 2016, respectively. The manufacturing and agricultural sectors represented far smaller percentages, 5.0% and 2.1%, respectively, in 2016. Historically, the Panamanian economy has been characterized by an imbalance between the open, internationally-oriented service sector and the relatively closed manufacturing and agricultural sectors, where productivity has been lower and government policies may have affected resource allocation. See “Structure of the Panamanian Economy—Principal Sectors of the Economy”. Ongoing investments are designed to promote Panama as a hub for logistic, maritime and air transport services.

While much of the service sector economic activity is represented by activities associated with public administration, commerce and real estate, the significant internationally-oriented activities of this sector distinguish the Panamanian economy, particularly transportation, storage, communication and financial intermediation. For instance, in the Canal’s 2016 fiscal year (which ended September 30, 2016), commercial oceangoing traffic registered 13,114 transits, and the Canal’s toll revenue was U.S.$1,932.99 million, representing 3.5% of Panama’s estimated GDP for 2016 measured in nominal dollars.

As a result of the dollar-based economy, the international trade associated with the Panama Canal and the CFZ, and certain legislative initiatives, Panama has also developed an important financial sector that represented 7.7% and 7.9% of GDP in 2015 and 2016, respectively. There is no lender of last resort or deposit insurance in Panama. See “Financial System—The Banking Sector”.

Reforms and Development Programs

Social Security. In December 2005, the Assembly approved Law No. 51, which reformed Panama’s social security system by, among other things, requiring employees to make contributions into the social security system for 20 years (up from the prior 15-year requirement) before becoming eligible to receive benefits and gradually transitioning from a defined benefits system to personal savings accounts. Law No. 51 also established the obligation to support the Disability, Old Age and Death Benefit System (Régimen de Invalidez, Vejez y Muerte (“IVM”)) with annual deposits by the Central Government to an administration and investment trust created for the sustainability of the IVM of U.S.$75 million in each of the years 2007, 2008 and 2009, U.S.$100 million in each of the years 2010, 2011 and 2012, and U.S.$140 million in each of the years 2013 through 2060.

D-18

Trade Liberalization. Trade liberalization advanced with Panama’s accession to the WTO, which became effective September 6, 1997. Panama has also negotiated free trade agreements with many of its trading partners, such as the United States, Canada, the European Free Trade Association, Mexico, Colombia, Chile and Central American countries. See “Foreign Trade and Balance of Payments—Tariffs and Other Trade Restrictions”.

Government Procurement. On May 10, 2011, Law No. 22 of 2006, which established a system for government procurement in Panama, was modified by Law No. 48 of 2011. The modification grants the Dirección General de Contrataciones Públicas (“Public Contracting Authority”) the power to impose fines. In addition, it expanded the scope of the law to include regulation of acquisitions by the Caja de Seguro Social (“Social Security Fund” or “CSS”) of pharmaceutical products as well as contracts with funding supplied by foreign governments. Law No. 48 of 2011 also modified provisions that regulate, among other things, exemption from the contractor selection process and the sale of assets under exceptional process, advertising and promotion services contracts.

Export Processing Zones & Free Zones. During 2007, two export processing zones (“EPZs”) were created in Panama. EPZs are well-defined areas for establishing industrial, commercial and service facilities for operation in a free trade system. In June 2007, the Zona Procesadora Chilibre was created and, in August 2007, the Zona Procesadora Colón Maritime Investor, S.A. was created to provide infrastructure, facilities and support systems to attract new business and foreign investments. In June 2009, the Hewlett-Packard Global Services Panama EPZ was created. In August 2013, the Vaguil EPZ was created to implement the Panama Diamond Exchange, which is the first and only Latin American diamond and gemstone bourse recognized by the World Federation of Diamond Bourses. Panama is a member of the Kimberley Process, which is designed to prevent the import of diamonds from conflict areas in Africa. As of September 2017, 82 call centers had official registrations with EPZs. In December 2016, the Cabinet Council authorized the National Commission on Free Zones to approve the establishment and operation of a free zone by Consorcio Industrial de las Americas, S.A. in Pacora, Panama province, the “PanaPark Free Zone,” which is expected to host approximately 250 businesses operating in manufacturing, logistics, services, technology and assembly. Construction of the PanaPark Free Zone began in January 2017, and manufacturing activities are expected to begin in October 2017.

Fiscal Reforms. On June 5, 2008, Law No. 34 of 2008 was ratified, establishing a Social and Fiscal Responsibility Regime to promote sound fiscal policies and management. This law came into effect on January 1, 2009. The Social and Fiscal Responsibility Regime requires any new government to present, during the first six months of its administration, a multi-year social strategy, a five-year financial plan and the macroeconomic criteria to manage public expenditures and to incentivize current savings. Through Executive Decree No. 689 of December 26, 2014, the Varela administration adopted its five-year Strategic Government Plan, “Un solo país”. The Plan includes the economic and social strategy, the financial program and a five-year indicative public investment plan that establishes the criteria for public expenditure for prioritized sectors, programs and projects. Such prioritized sectors include, among others, transportation, energy, agriculture and tourism, while projects and programs include a project to improve access to potable water and a program to improve education.

In addition to creating the Fondo de Ahorro de Panamá (Panama Saving Fund, “FAP”), Law No. 38 of June 5, 2012 amended the Social and Fiscal Responsibility Law to set a ceiling on the annual non-financial public sector adjusted deficit of 2.9% of GDP for 2012, 2.8% for 2013, 2.7% for 2014, 2.0% for 2015, 1.5% for 2016, 1.0% for 2017 and 0.5% thereafter. The amendment also allows a temporary suspension of the fiscal deficit ceiling in cases of emergency or a deceleration in economic activity. On November 26, 2012, Cabinet Resolution No. 157 declared a National State of Emergency as a result of severe damage to roads and housing infrastructure in the provinces of Panama and Colón resulting from flooding and landslides from heavy rainfall in November 2012. The Government estimated that damage caused by this natural event totaled approximately U.S.$123.2 million, or 0.3% of nominal GDP, and raised the effective fiscal deficit ceiling of the non-financial public sector for 2012 to 3.1% of nominal GDP. In March 2013, the Cabinet approved an extraordinary credit to the National Budget of U.S.$123.2 million, allocated to several public institutions responsible for the rehabilitation and reconstruction of the damaged infrastructure. The largest amounts of extraordinary funds were allocated to the Ministry of Public Works ($83.8 million) and the Ministry of Housing and Territorial Administration ($24.0 million).

On September 2, 2014, pursuant to Cabinet Resolution No. 152, the Executive approved an approximately U.S.$590 million expenditure reduction plan for 2014 consisting of reductions of U.S.$100 million in current expenditures and U.S.$490 million in the investment budget. The plan called for a freeze on new hiring. The projects that would be subject to budget cuts were those that had

D-19

not yet started and those designated as low priority. The plan did not affect the debt service budget. The Government was committed to reducing the deficit in light of the 2014 ceiling imposed by the Social and Fiscal Responsibility Law, which was approximately U.S.$1.3 billion for 2014, in light of a preliminary fiscal deficit of the Non-Financial Public Sector for the first six months of 2014 of approximately U.S.$1.5 billion. In September 2014, the Government estimated that the expenditure reduction plan would not, by itself, accomplish the goal of meeting the Social and Fiscal Responsibility Law target, and that the deficit might fall within a range of 3.7%-4.2% of GDP. In December 2014, the Government requested that the Assembly increase the 2014 deficit ceiling, but not the deficit ceiling for subsequent years. The non-financial public sector deficit for 2014 was U.S.$1,563 million, equivalent to 3.2% of GDP. In 2015 and 2016, the non-financial public sector deficit was U.S.$1,208 million and U.S.$1,065 million, equivalent to 2.3% of GDP and 1.9% of GDP, respectively, compared to statutory ceilings of 2.0% and 1.5% for 2015 and 2016, respectively. The Fiscal and Social Responsibility Law provides that five senior economic officials of the Republic, including the Minister of Economy and Finance and the Comptroller General, would be responsible if the deficit ceiling were to be exceeded, but the law does not specify what such responsibility would entail, nor does the law specify any institutional consequences for non-compliance.

In April 2011, Law No. 31 was ratified, modifying the Panamanian Fiscal Code. The modified law implemented, among other things, a dividend tax for every loan or credit that companies provide to their shareholders. The dividend tax consists of a withholding of 10% of the amount of a loan or credit, irrespective of income. In the case of bearer shares, the dividend tax increased to 20%. Under the modified law, only legal entities producing taxable income that are subject to income tax will be required to pay a Monthly Advance of Income Tax, a tax introduced by Law No. 8 of March 2010.

In August 2012, Law No. 52 eliminated an estimated income tax introduced by Law No. 8 of March 2010 because the tax did not meet the expectations of the authorities and created additional administrative burden for taxpayers and for the revenue authority. The tax was replaced by the previous system of estimating income tax payments based on the previous year’s income.

In May 2015, Law No. 27 established new taxes on non-metallic mining products, such as sand, gravel, quarried stone, limestone, clay and tuff stone. The rates vary according to the kind of mineral. Law No. 27 also established that all coupons and tickets, gaming chips and other documents containing a payment obligation resulting from gambling activities would be subject to a tax rate of 5.5%. Funds collected on these activities will be allocated to finance increases in monthly pension distributions according to the following schedule: monthly distributions of less than U.S.$250.00 increase by U.S.$50 per month; distributions of U.S.$250.01 to U.S.$270.00 increase by U.S.$45 per month; distributions of U.S.$270.01 to U.S.$300.00 increase by U.S.$40 per month; distributions of U.S.$300.01 to U.S.$400.00 increase by U.S.$30 per month and distributions of U.S.$400.01 to U.S.$1,000.00 increase by U.S.$20 per month. These increases in pensions represent approximately U.S.$75 million per year.

Social Developments. Panama’s social spending generally focuses on spending in the social sectors of health, education and housing. In 2015 and 2016, social spending represented approximately 41.4% and 43.4% of the Government’s budget, respectively.

In May 1995, the Government created the Development Trust Fund pursuant to Law No. 20 and, on June 27, 2000, the Assembly approved Law No. 22, which approved the use of the Development Trust Fund principal for social development programs and infrastructure projects. The laws provided that up to U.S.$200 million could be drawn down from the Development Trust Fund to support infrastructure projects. The disbursements were to be made against invoices presented to the Ministry of Economy and Finance. See “Structure of the Panamanian Economy—The Role of the Government in the Economy”. From 2006 through 2010, funds were available in the following amounts: U.S.$70.0 million to water supply; U.S.$30.0 million to irrigation and agricultural projects; and U.S.$97.0 million to road rehabilitation. During the same period, U.S.$69.8 million had been disbursed to fund water supply projects; U.S.$27.3 million to fund irrigation and agricultural projects; and U.S.$94.5 million to fund road rehabilitation projects. From its inception through December 31, 2010, which was the final year that funds were disbursed from the Development Trust Fund, approximately U.S.$194.3 million were disbursed to support infrastructure projects.

In June 2012, the Government created the FAP pursuant to Law No. 38 of 2012. The initial capital of the FAP came from the Development Trust Fund. The FAP was capitalized and began operations on June 7, 2012. The Development Trust Fund has ceased to exist. According to the FAP’s accumulation rule, every year income from the Canal of up to 3.5% of GDP will be deposited in the National Treasury and any excess over that amount will be transferred to the FAP. The FAP has two main objectives: (1) macroeconomic stability in cases of national emergencies and (2) long-term national savings. The FAP also may repurchase and retire Panamanian sovereign debt once the size of the FAP reaches 5.0% of GDP. The FAP Secretary reports to the Ministry of Economy and Finance, which establishes investment guidelines for the FAP. In addition, Law No. 38 provides for the BNP to serve as the FAP’s Trustee and for an independent Board of Directors to safeguard FAP assets. In 2016, the FAP generated interest of U.S.$26.1 million compared to U.S.$24.4 million in 2015 and had net assets of U.S.$1,265.0 million, an increase of 3.3% from U.S.$1,225.0 million in 2015 due to a decrease in accounts payable to asset managers.

D-20