Exhibit 99.E

© South African Reserve Bank

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without fully acknowledging the Quarterly Bulletin of the South African Reserve Bank as the source. The contents of this publication are intended for general information only and are not intended to serve as financial or other advice. While every precaution is taken to ensure the accuracy of information, the South African Reserve Bank shall not be liable to any person for inaccurate information or opinions contained in this publication.

| | | | |

Enquiries relating to this Bulletin should be addressed to: | | | | |

Head: Research Department | | | | |

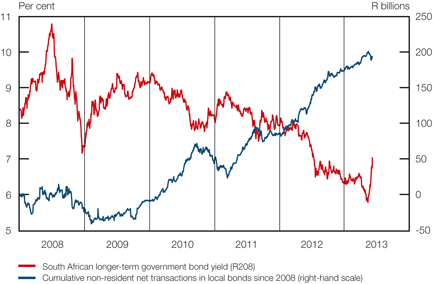

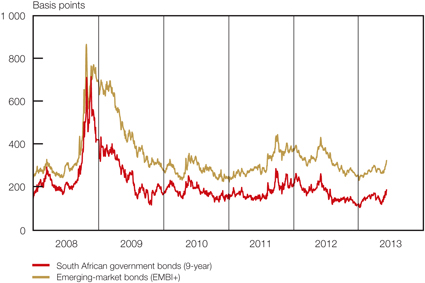

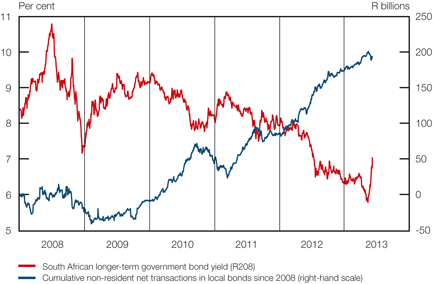

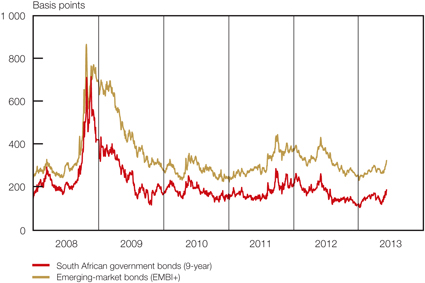

South African Reserve Bank | | | | |

P O Box 427 | | | | |

Pretoria 0001 | | | | |

Tel. +27 12 313-3668/3676 | | | | |

http://www.reservebank.co.za | | | ISSN 0038-2620 | |

| | |

| | Quarterly Bulletin June 2013 |

Contents

Quarterly Economic Review

| | | | |

Introduction | | | 1 | |

Domestic economic developments | | | 4 | |

Domestic output | | | 4 | |

Real gross domestic expenditure | | | 8 | |

Factor income | | | 13 | |

Gross saving | | | 14 | |

Employment | | | 14 | |

Labour cost and productivity | | | 19 | |

Prices | | | 20 | |

Foreign trade and payments | | | 27 | |

International economic developments | | | 27 | |

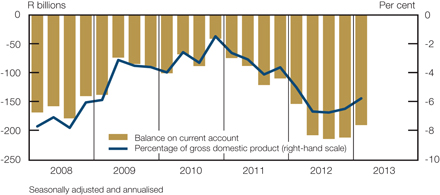

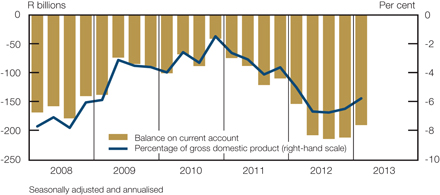

Current account | | | 30 | |

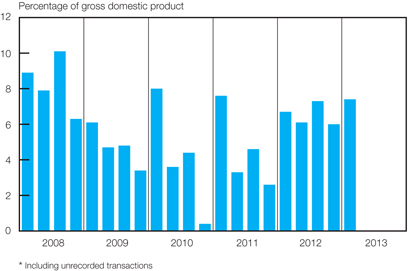

Financial account | | | 35 | |

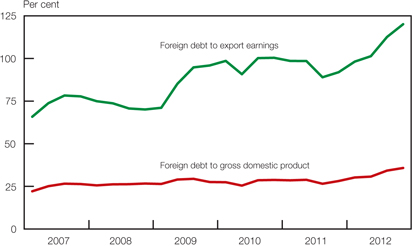

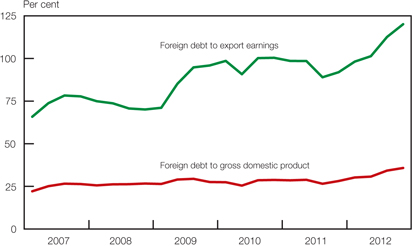

Foreign debt | | | 37 | |

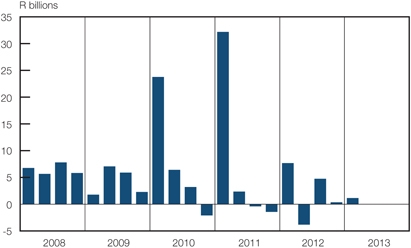

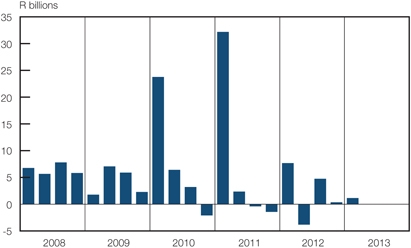

International reserves and liquidity | | | 38 | |

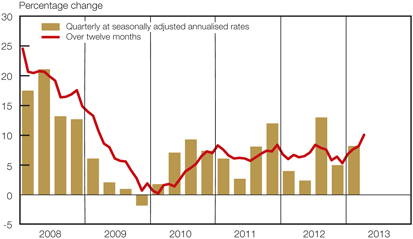

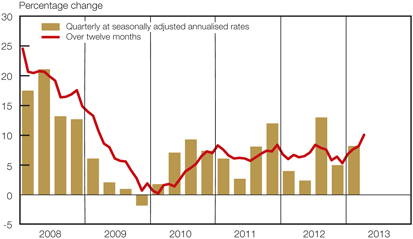

Exchange rates | | | 39 | |

Monetary developments, interest rates and financial markets | | | 41 | |

Money supply | | | 41 | |

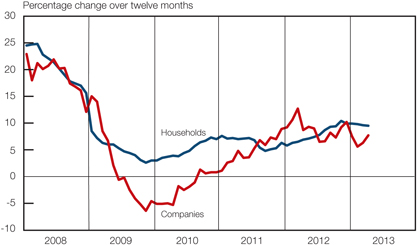

Credit extension | | | 43 | |

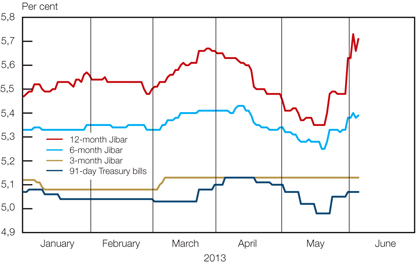

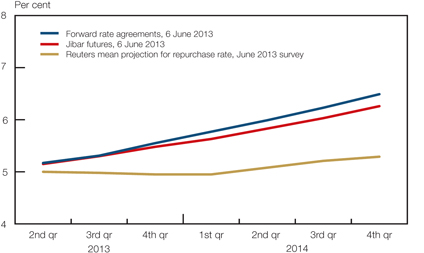

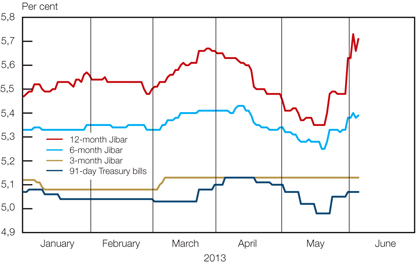

Interest rates and yields | | | 45 | |

Money market | | | 49 | |

Bond market | | | 51 | |

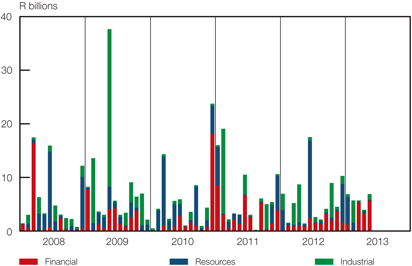

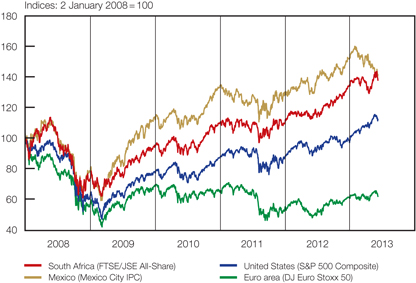

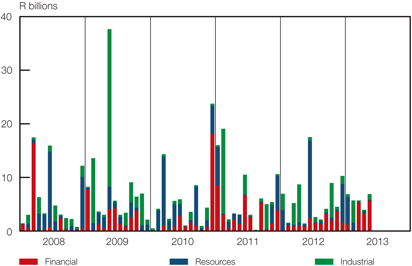

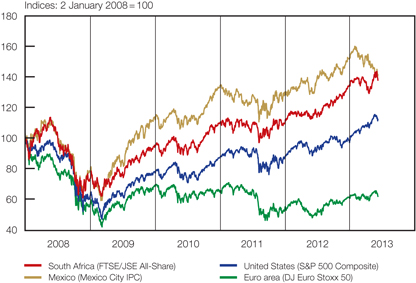

Share market | | | 52 | |

Market for exchange-traded derivatives | | | 54 | |

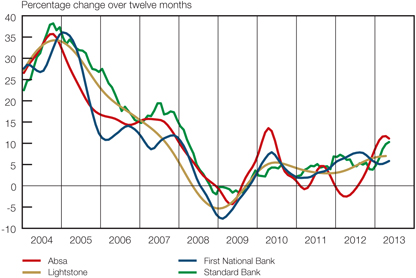

Real-estate market | | | 54 | |

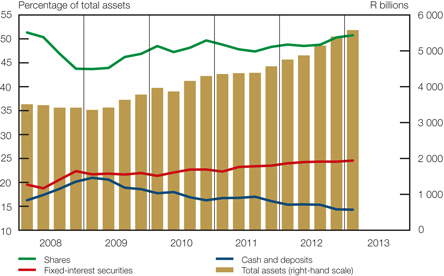

Non-bank financial intermediaries | | | 55 | |

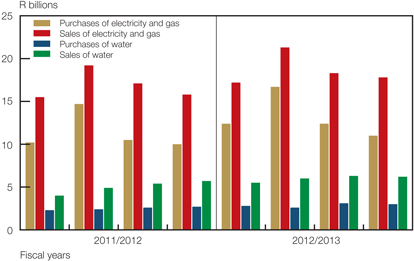

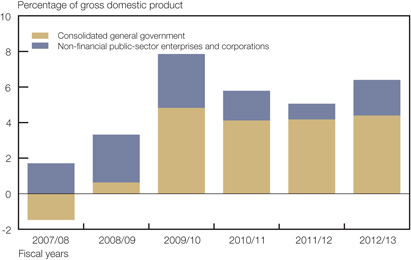

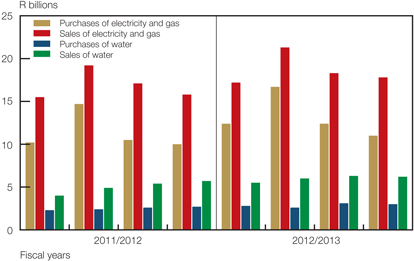

Public finance | | | 57 | |

Non-financial public-sector borrowing requirement | | | 57 | |

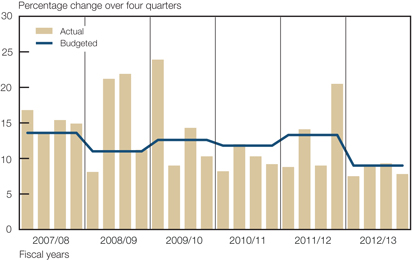

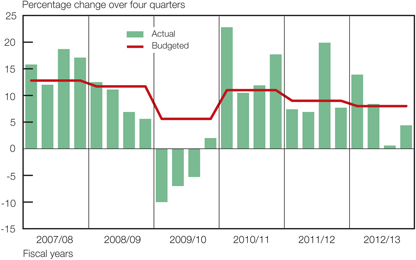

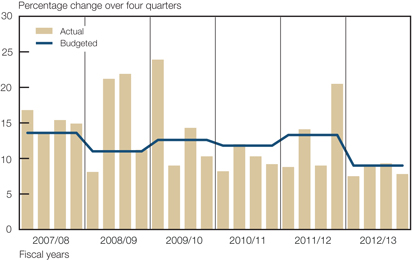

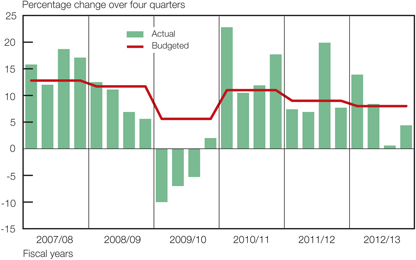

Budget comparable analysis of national government finance | | | 61 | |

| |

Statements issued by Gill Marcus, Governor of the South African Reserve Bank | | | | |

| |

Statement of the Monetary Policy Committee 20 March 2013 | | | 67 | |

| |

Statement of the Monetary Policy Committee 23 May 2013 | | | 72 | |

| |

Note | | | | |

| |

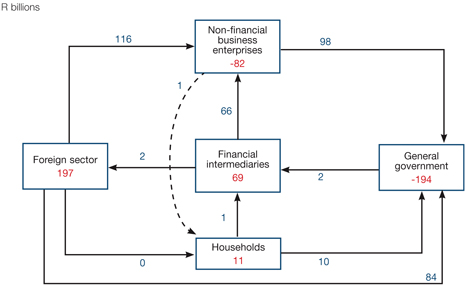

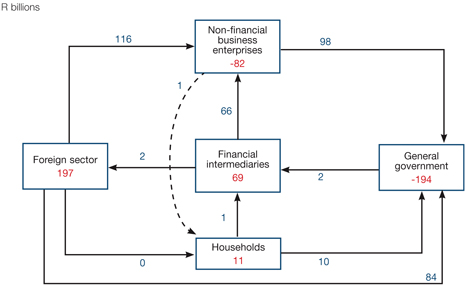

Note on the flow of funds in South Africa’s national financial account for the year 2012 | | | 76 | |

| |

Notes to tables | | | 90 | |

| |

Statistical tables | | | | |

| |

Contents | | | S–0 | |

Statistical tables | | | S–2 | |

Key information | | | S–144 | |

| | |

| Quarterly Bulletin June 2013 | |  |

Quarterly Economic Review

Introduction

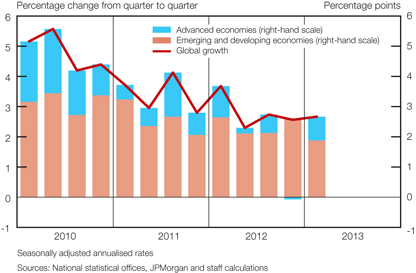

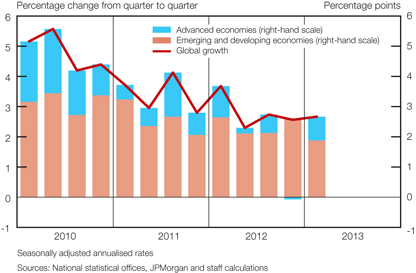

During the first quarter of 2013 the hesitant global recovery continued at a somewhat firmer pace, as a slackening in the rate of expansion in the developing economies was more than fully countered by improved real growth in the advanced economies, particularly in the United States (US) and Japan. Economic activity in the euro area contracted further over the period, with already fragile confidence being undermined towards the end of the quarter by developments in Cyprus. Among the developing countries China experienced lower-than-expected growth in the first quarter, although still expanding at more than twice the pace of overall global output. While the outlook for economic activity in sub-Saharan Africa remained positive, a number of setbacks detracted from the region’s growth momentum in the early part of the year.

Global inflation remained fairly well contained in the first four months of 2013, although inflation outcomes in emerging-market and developing countries exceeded those in the advanced economies. The pedestrian pace of expansion in global activity and slowdown in China’s resource-intensive growth contributed to a moderation in the international prices of oil and a range of other commodities, particularly from mid-February 2013. Under these circumstances most countries maintained an expansionary monetary policy stance, particularly the advanced economies.

In South Africa economic activity lost traction in the first quarter of 2013 as real growth decelerated to an annualised rate of 0,9 per cent – less than the concurrent pace of population growth. The marked loss of growth momentum was largely due to a contraction in manufacturing output, as steel production was affected by a fire at a large steel mill and petroleum refineries were shut down for maintenance. Simultaneously, agricultural output declined as a dry mid-season spell resulted in a downward revision in crop estimates. The production of electricity also contracted further over the period, reflecting the impact of supply constraints and higher real prices. By contrast, real value added in mining increased as platinum output recovered from the strike-related production stoppages that affected the platinum industry in the second half of 2012, while gold output rose somewhat despite an underground fire at one of the major gold mines. In the construction industry activity in the residential and non-residential building sectors picked up somewhat in the first quarter of 2013.

In the services sector real output continued expanding at a reasonably firm pace, buoyed by activity in the finance, retail trade and communication subsectors. With employment gains in government slowing in the first quarter of 2013, growth in the general government’s real value added moderated somewhat over the period.

Growth in real gross domestic expenditure accelerated in the first quarter of 2013 as real final consumption by government and inventory investment rebounded, having registered declines in the previous quarter. The most significant increases in real inventory holdings in the first quarter were recorded in the manufacturing and mining sectors, replenishing low stock levels carried over from the previous period. Government simultaneously stepped up real spending on non-wage goods and services, alongside a slower pace of increase in real compensation of government employees.

Growth in real disposable income of households and the pace of increase in real final consumption expenditure by households both moderated somewhat in the first quarter of 2013. The pace of increase in spending on durable goods continued to lose momentum, especially in the area of purchases of new motor vehicles albeit off a high base. Expenditure on semi-durable goods remained firm, supported by resilient spending on clothing and footwear, whereas the pace of increase in households’ purchases of non-durable goods also decelerated significantly over the period. Real spending by households on services registered a moderate acceleration in the first quarter of 2013 as expenditure on rent, household and medical services increased. Households continued to incur further debt over the period but at a fairly modest pace which was closely aligned with the growth in disposable income, resulting in a broadly sideways movement of the household debt-to-income ratio.

| | |

| Quarterly Bulletin June 2013 | |  |

Growth in real gross fixed capital formation slowed further in the first quarter of 2013. Of the main three institutional sectors, only general government registered an acceleration as provincial and central government departments increased their capital spending on housing and construction works. Fixed capital outlays by both private business enterprises and public corporations registered slower growth. The deceleration in investment activity by private business enterprises was widespread and consistent with the generally more subdued economic conditions, with only the agricultural sector, building contractors and business services firms stepping up their expenditure on capital goods. Albeit off a high base, the pace of increase in real capital spending by public corporations slowed considerably in the first quarter, reflecting a weakening of capital investment by the electricity sector as industrial action interrupted progress with the construction of a new power plant. This negative impact was partly offset by firm capital expenditure by public corporations related to the expansion of freight rail, port terminal and road capacity.

The subdued growth trajectory in South Africa was mirrored in lustreless job creation, with total employment rising by only 1,5 per cent over the year to the first quarter of 2013 and a quarter of the workforce remaining unemployed. Job creation continued to be skewed towards the public sector rather than the private sector. Average wage settlements rose marginally in the first quarter of 2013 when compared with 2012, but allowing for productivity improvements, unit labour cost increases remained fairly aligned with the upper limit of the 3 to 6 per cent inflation target range. Consumer price inflation accelerated in the course of the past year, driven by the prices of petrol, food, transport, education, health services and health insurance, and levelled off just below the upper limit of the target range in the early part of 2013. The depreciation in the exchange value of the rand over the past year was an important indirect contributor to the inflation process.

In the first quarter of 2013 the deficit on the current account of the balance of payments narrowed to 5,8 per cent of gross domestic product. The trade account benefited from an increase in external demand, especially from emerging-market economies, firm international prices for South African export commodities, an improvement in the terms of trade and a more competitive exchange value of the rand. Although imports also rose significantly as domestic expenditure expanded, this fell short of the increase in export proceeds. Simultaneously the deficit on the services and current transfer account narrowed, reflecting improved travel and dividend receipts from the rest of the world.

The deficit on the current account was fully financed by a further sizeable inflow of foreign capital in the first quarter of 2013, registered against the backdrop of nominal interest rate differentials that continued to favour South Africa. A net inflow of direct investment capital was recorded as foreign parent companies extended long-term loans to their domestic subsidiaries. Other investment flows also registered an inflow of capital on a net basis, while portfolio investment (including new issues and redemptions of portfolio investment assets) switched to a net outflow of capital over the period.

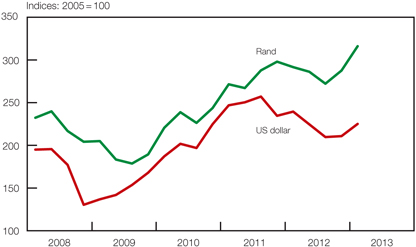

The exchange value of the rand depreciated in the first five months of 2013 driven by apprehension about a range of factors including South Africa’s comparatively large current-account deficit, loss of international competitiveness, electricity-supply constraints, labour unrest, the possibility of weaker global demand for commodities, and concerns about further sovereign debt downgrades. During May severe industrial action and violent unrest highlighted the risk of further mining-supply disruptions, exacerbating the depreciation of the exchange rate.

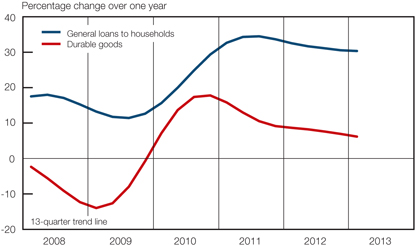

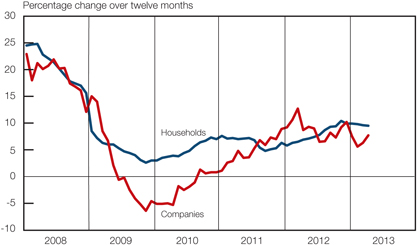

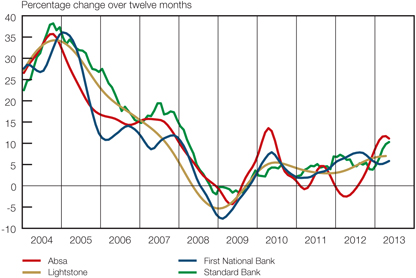

Overall bank lending to the domestic private sector remained hesitant in the first four months of 2013 despite the low levels at which benchmark interest rates had been maintained since mid-2012. Growth in general loans to the household sector started to lose some of its earlier buoyant momentum, probably reflecting greater caution among lenders and borrowers alike. However, instalment sale credit continued to expand briskly over the period, consistent with fairly high levels of purchases of durable goods. Mortgage lending remained very slow, although a number of indicators of housing activity and prices started improving.

| | |

| | Quarterly Bulletin June 2013 |

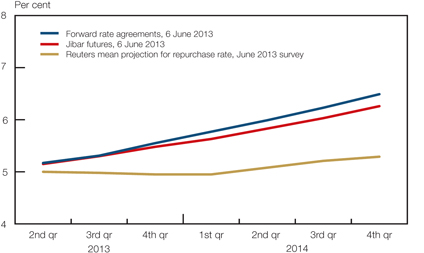

Share prices on the JSE Limited (JSE) reached further record highs in the first part of 2013 and bond yields also trended lower to levels previously observed more than four decades ago. However, in May and early June the depreciation of the exchange value of the rand and associated expectations of higher inflation resulted in a significant firming of bond yields, while rates on forward rate agreements also rose notably.

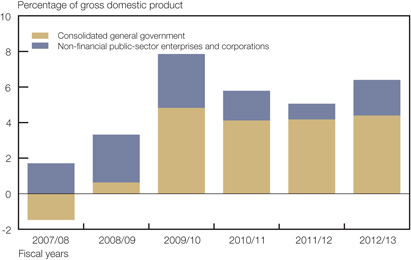

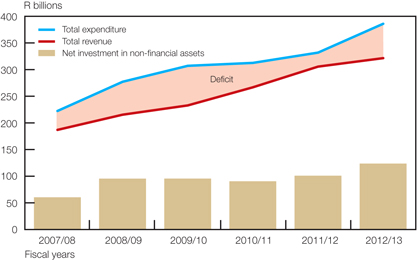

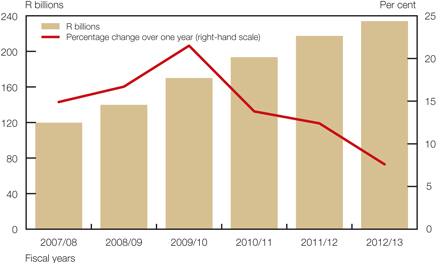

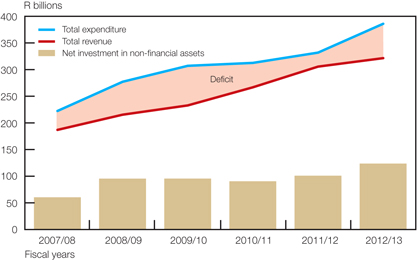

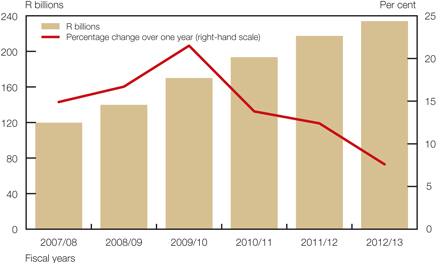

The finances of the broad public sector had a decidedly more expansionary thrust in the past fiscal year. While the general government continued to render support to the economic recovery by incurring a somewhat larger deficit, the financial shortfall of the non-financial public enterprises and corporations more than doubled over the period as these institutions stepped up their infrastructure investment drive. At the same time the ratio of government debt to gross domestic product continued on an upward trajectory, although remaining well contained when compared with debt ratios in other economies.

| | |

| Quarterly Bulletin June 2013 | |  |

Domestic economic developments

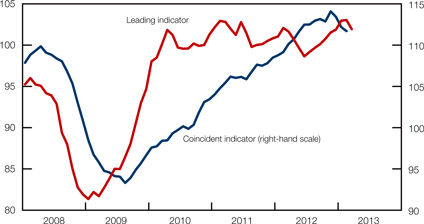

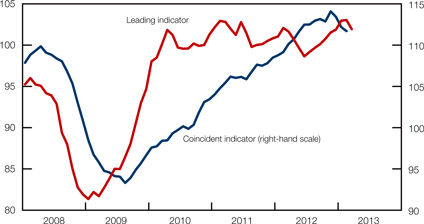

Following eight consecutive monthly increases, the composite leading business cycle indicator decreased in March 2013. The leading indicator has trended broadly sideways since mid-2010, suggesting a continuation of the sluggish economic growth rates observed in recent quarters. The composite coincident business cycle indicator decreased for a third consecutive month in February 2013, reflecting the recent loss of momentum in output growth in the domestic economy.

Composite business cycle indicators

Indices: 2010 = 100

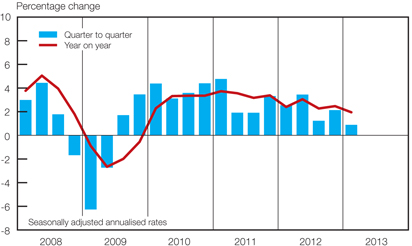

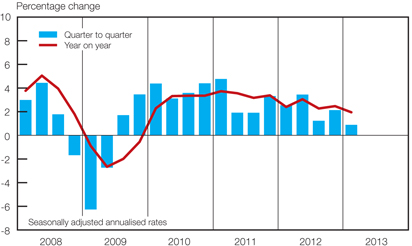

Domestic output1

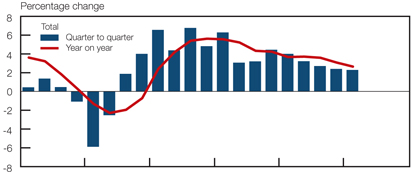

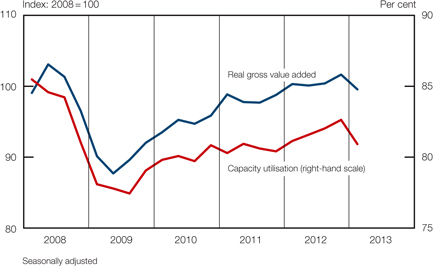

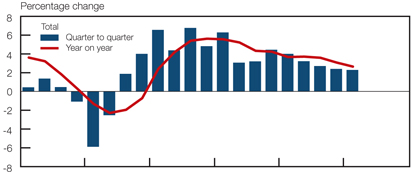

Activity in the domestic economy lost some momentum in the first quarter of 2013. Growth in real gross domestic production slowed from an annualised rate of 2,1 per cent in the final quarter of 2012 to 0,9 per cent in the first quarter of 2013. The slower pace of increase primarily reflected a contraction in the real output of the secondary sector. Growth in the real value added by the primary sector rebounded, while activity in the tertiary sector remained lively.

Real gross domestic product

| | |

| | Quarterly Bulletin June 2013 |

Excluding the contribution of the more volatile primary sector, growth in real gross domestic product plunged from 2,7 per cent in the fourth quarter of 2012 to only 0,2 per cent in the first quarter of 2013.

Subsequent to a decline of 3,7 per cent in the fourth quarter of 2012, the real value added by the primary sector expanded at a firm pace in the first quarter of 2013, rising at an annualised rate of 8,1 per cent. Real output of the mining sector improved following the low production base in the final quarter of 2012 brought about by protracted labour-related shutdowns of operations and technical problems experienced at some mines. Agricultural output growth, however, turned negative in the first quarter of 2013.

Real gross domestic product

Percentage change at seasonally adjusted annualised rates

| | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | |

| | | 2012 | | | 2013 | |

Sector | | 1st qr | | | 2nd qr | | | 3rd qr | | | 4th qr | | | Year | | | 1st qr | |

Primary sector | | | -9,5 | | | | 24,0 | | | | -7,1 | | | | -3,7 | | | | -2,2 | | | | 8,1 | |

Agriculture | | | 4,8 | | | | 9,3 | | | | 7,4 | | | | 10,0 | | | | 2,3 | | | | -4,9 | |

Mining | | | -15,1 | | | | 30,9 | | | | -12,7 | | | | -9,3 | | | | -4,0 | | | | 14,6 | |

Secondary sector | | | 5,5 | | | | -0,5 | | | | 1,5 | | | | 3,6 | | | | 2,1 | | | | -6,2 | |

Manufacturing | | | 6,4 | | | | -0,8 | | | | 1,2 | | | | 5,0 | | | | 2,4 | | | | -7,9 | |

Tertiary sector | | | 3,1 | | | | 2,3 | | | | 1,9 | | | | 2,4 | | | | 3,0 | | | | 2,4 | |

Non-primary sector | | | 3,7 | | | | 1,6 | | | | 1,8 | | | | 2,7 | | | | 2,8 | | | | 0,2 | |

Total | | | 2,5 | | | | 3,4 | | | | 1,2 | | | | 2,1 | | | | 2,5 | | | | 0,9 | |

| | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | |

Lower field crop production brought about by a dry mid-season spell was reflected in the real value added by the agricultural sector declining at a rate of 4,9 per cent in the first quarter of 2013. Livestock and horticultural production, by contrast, held up fairly well over the period. Early indications are that field crop production for the 2012/13 production season is likely to be lower than in the previous production season.

Commercial maize crop estimates

| | | | | | | | |

| | | Crop | | | Area planted | |

| Period | | (Million tons) | | | (Million hectares) | |

2011/12: Final | | | 12,1 | | | | 2,7 | |

2012/13: Fourth production forecast | | | 11,4 | | | | 2,8 | |

Source: Crop Estimate Committee

Following declines in the second half of 2012, the real value added by the mining sector rebounded, rising at an annualised rate of 14,6 per cent in the first quarter of 2013. The recovery in mining output could mainly be attributed to increases in the production of gold and platinum over the period. Mining production contributed 0,7 of a percentage point to growth in real gross domestic product in the first quarter of 2013 after having subtracted 0,5 of a percentage point in the final quarter of 2012.

The gold-mining sector benefited from increased production following strike activity in the second half of 2012. Production losses due to an underground fire at one of South Africa’s major gold mines in the early months of 2013, together with the power outage and production ramp-up at another gold mine, however, partly restrained the growth in gold output over the period. Platinum production continued to recover from the strike-related production stoppages

| | |

| Quarterly Bulletin June 2013 | |  |

that affected the platinum industry in the second half of 2012. Coal production receded in the first quarter of 2013 due to excessive rainfall that affected most coal mines and ongoing strike action that halted production at several coal operations. Contingency measures, however, assured the supply of coal to power stations during the period. Diamond production contracted markedly during the quarter as excessive rainfall disrupted production at the country’s biggest diamond mine. A deterioration in the grades and quality of diamonds further contributed to lower production volumes at certain mines over the period. More generally, rapidly rising input costs, productivity impediments and illegal strike action, combined with a falling demand for some mineral products, continued to affect mining operations adversely in South Africa.

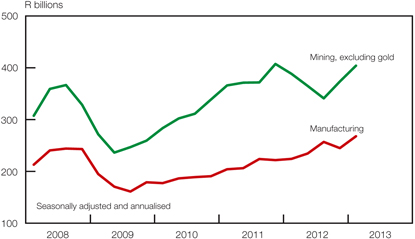

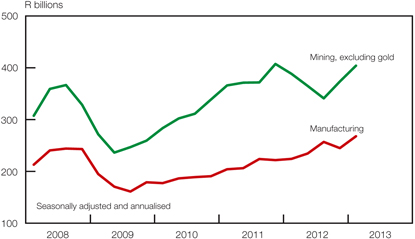

Real gross domestic product of the mining sector

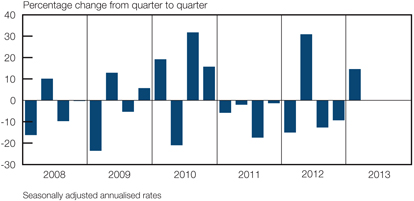

Having increased at an annualised rate of 3,6 per cent in the fourth quarter of 2012, the real value added by the secondary sector contracted at a rate of 6,2 per cent in the first quarter of 2013. Production in the manufacturing and electricity, gas and water sectors receded, while growth in the real value added by the construction sector was broadly maintained over the period.

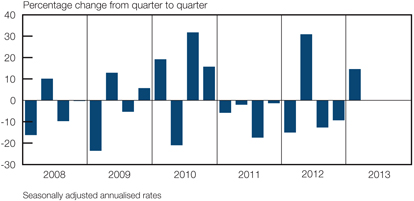

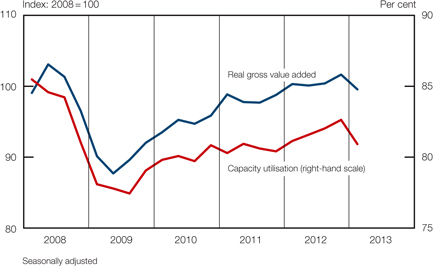

The real value added by the manufacturing sector switched from a moderate increase of 5 per cent in the fourth quarter of 2012 to an annualised rate of decline of 7,9 per cent in the first quarter of 2013 – reducing output to levels recorded roughly a year earlier. This decline reflected lower production volumes in the manufacturing of wood and wood products; petroleum and chemicals; glass and non-metallic mineral products; basic iron and steel, non-ferrous metal products and machinery; radio, television and communication apparatus and professional equipment; and furniture and other manufacturing products. Conversely, production increased in the subsectors for food and beverages; textiles, clothing, leather and footwear; electrical machinery; and motor vehicles, parts and accessories and other transport equipment. The contraction in manufacturing production caused the contribution of manufacturing to growth in real gross domestic product to change from adding 0,8 of a percentage point in the fourth quarter of 2012 to subtracting 1,2 percentage points in the first quarter of 2013.

| | |

| | Quarterly Bulletin June 2013 |

The weaker performance of the manufacturing sector could be attributed to subdued business confidence levels, sluggish domestic demand, rising inflation, disrupting industrial action, concerns about sustainable electricity supply, and poor trading conditions in many of the country’s leading trading-partner countries. With a fire at a steel mill and refinery maintenance also dragging production down, the utilisation of production capacity in the manufacturing sector declined from 82,6 per cent in the fourth quarter of 2012 to 80,9 per cent in the first quarter of 2013, well below its recent peak of 86,6 per cent registered in the first quarter of 2007.

Manufacturing: Real gross value added and capacity utilisation

In the sector supplying electricity, gas and water, the real value added contracted further at an annualised rate of 3 per cent in the first quarter of 2013, following a decline of 2,2 per cent in the fourth quarter of 2012. This was the fourth quarterly decline in the real value added by the sector in five consecutive quarters, and could partly be attributed to unscheduled maintenance at a production unit due to an electrical fault. Year-on-year growth in electricity consumption plunged to its lowest rate since the second quarter of 2012, reflecting, inter alia, the outcome of Eskom’s ongoing buy-back agreements with some large-scale industrial users to save electricity, and the impact of higher electricity prices on consumption.

Growth in real output of the construction sector accelerated marginally from an annualised rate of 0,2 per cent in the fourth quarter of 2012 to 0,9 per cent in the first quarter of 2013. Construction activity in the residential and non-residential building sectors picked up somewhat, while civil construction activity slowed over the period.

In the services sector real output growth was maintained at a rate of 2,4 per cent in both the fourth quarter of 2012 and the first quarter of 2013. The real value added by the finance, insurance, real-estate and business services, and by the trade and transport sectors increased over the period, while activity in the general government sector lost momentum.

After recording progressively slower quarter-to-quarter growth throughout 2012, the real value added by the trade sector bounced back and rose at an annualised rate of 1,9 per cent in the first quarter of 2013. This increase could mainly be attributed to the improved performance of the retail subsector which continued to benefit from the relatively low interest rate environment. Over the same period, the real value added by the wholesale sector increased marginally, while growth in the real value added by the motor trade subsector slowed somewhat. Besides the slower growth in demand for new passenger vehicles by the household sector and weaker

| | |

| Quarterly Bulletin June 2013 | |  |

demand from the car rental industry, growth in light commercial vehicle (LCV) sales and the exports of passenger vehicles also moderated. Measured over one year, the growth in real value added by the trade sector slowed from 2,9 per cent in the fourth quarter of 2012 to 2,1 per cent in the first quarter of 2013.

The real value added by the transport, storage and communication sector increased mildly from an annualised rate of 1,9 per cent in the fourth quarter of 2012 to 2,2 per cent in the first quarter of 2013. Land transport volumes increased slightly in a more normalised trading environment following widespread disruptive labour disputes in the second half of 2012. Activity in the communication sector maintained its steady upward momentum in the opening months of 2013.

Growth in the real output originating in the finance, insurance, real-estate and business services sector accelerated from an annualised rate of 2,9 per cent in the fourth quarter of 2012 to 3,3 per cent in the first quarter of 2013. This acceleration largely reflected increased trading activity in the domestic securities market while the real value added by the banking sector decreased. According to the Ernst & Young Financial Sector Confidence Index, banking confidence was marginally softer in the first quarter of 2013.

The real value added by general government slowed from an annualised growth rate of 2,6 per cent in the fourth quarter of 2012 to 1,9 per cent in the first quarter of 2013 as employment gains in general government moderated over the period.

Real gross domestic expenditure

Real gross domestic expenditure increased at an annualised rate of 3,5 per cent in the first quarter of 2013, having declined by 0,9 per cent in the fourth quarter of 2012. Following a contraction previously, both real final consumption expenditure by general government and real inventory holdings increased in the first quarter. Although growth in real final consumption expenditure by households and gross fixed capital formation lost some momentum in the first quarter of 2013, real gross domestic final demand still increased at an annualised rate of 2,5 per cent over the period.

Components of real gross domestic final demand

| | |

| | Quarterly Bulletin June 2013 |

Real gross domestic expenditure

Percentage change at seasonally adjusted annualised rates

| | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | |

| | | 2012 | | | 2013 | |

| Component | | 1st qr | | | 2nd qr | | | 3rd qr | | | 4th qr | | | Year | | | 1st qr | |

Final consumption expenditure | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | |

Households | | | 4,0 | | | | 3,2 | | | | 2,7 | | | | 2,4 | | | | 3,5 | | | | 2,3 | |

General government | | | 1,9 | | | | 3,7 | | | | 8,3 | | | | -0,7 | | | | 4,2 | | | | 3,0 | |

Gross fixed capital formation | | | 4,6 | | | | 5,4 | | | | 5,6 | | | | 4,3 | | | | 5,7 | | | | 2,5 | |

Domestic final demand | | | 3,7 | | | | 3,7 | | | | 4,3 | | | | 2,1 | | | | 4,0 | | | | 2,5 | |

Change in inventories (R billions)* | | | 5,9 | | | | 6,3 | | | | 5,1 | | | | -4,1 | | | | 3,3 | | | | 4,0 | |

Gross domestic expenditure | | | 4,4 | | | | 4,4 | | | | 4,1 | | | | -0,9 | | | | 4,1 | | | | 3,5 | |

Growth in real final consumption expenditure by households slowed marginally from 2,4 per cent in the fourth quarter of 2012 to 2,3 per cent in the first quarter of 2013 amid dwindling consumer confidence levels. Real spending on both durable and non-durable goods slowed, while consumers sustained their strong appetite for semi-durable goods. Spending on services continued to increase at a slow pace during this period.

Real final consumption expenditure by households

Growth in real spending on durable goods slowed from an annualised rate of 6,1 per cent in the fourth quarter of 2012 to 5,4 per cent in the first quarter of 2013 – the lowest rate of increase in almost four years. This slower growth could probably be attributed to the moderation in real

| | |

| Quarterly Bulletin June 2013 | |  |

disposable income growth and in unsecured lending extended to households as banks appear to be tightening their lending practices in view of a deterioration in the risk profile of consumers. The slower spending mainly occurred in the personal transport equipment category, especially new motor vehicle sales, where the replacement cycle may have started to mature. Over the same period, real spending on furniture and household appliances increased further, albeit at a more moderate pace than in the preceding quarter.

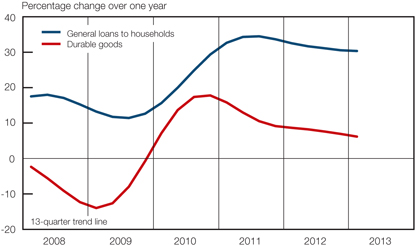

Growth in nominal household expenditure on durable goods and unsecured lending

Spending on durable goods has gradually lost momentum since the fourth quarter of 2011 as the household sector increasingly experienced higher levels of financial stress, exacerbated by rising inflation and slower growth in real disposable income. More recently, outlays on durable goods have probably also been hampered by the faster pace of increase in the relative prices of imported goods due to the depreciation in the exchange value of the rand.

Real final consumption expenditure by households

Percentage change at seasonally adjusted annualised rates

| | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | |

| | | 2012 | | | 2013 | |

| Component | | 1st qr | | | 2nd qr | | | 3rd qr | | | 4th qr | | | Year | | | 1st qr | |

Durable goods | | | 8,1 | | | | 8,9 | | | | 7,8 | | | | 6,1 | | | | 11,0 | | | | 5,4 | |

Semi-durable goods | | | 6,1 | | | | 6,8 | | | | 6,2 | | | | 5,1 | | | | 6,2 | | | | 6,2 | |

Non-durable goods | | | 2,5 | | | | 2,2 | | | | 1,7 | | | | 2,3 | | | | 2,5 | | | | 1,4 | |

Services | | | 3,6 | | | | 1,7 | | | | 1,3 | | | | 0,8 | | | | 1,8 | | | | 1,1 | |

Total | | | 4,0 | | | | 3,2 | | | | 2,7 | | | | 2,4 | | | | 3,5 | | | | 2,3 | |

After increasing at a slightly slower pace in the fourth quarter of 2012, spending on semi-durable goods increased at a somewhat faster pace in the first quarter of 2013. Spending on clothing and footwear – the largest category of semi-durable goods – remained firm, partly due to the prices of these products being well contained. Moreover, spending on household textiles, furniture, and recreational and entertainment goods also picked up, whereas spending on motor vehicle parts and accessories and miscellaneous goods remained lacklustre over the period.

Subsequent to an annualised increase of 2,3 per cent in the fourth quarter of 2012, growth in real spending on non-durable goods decelerated to 1,4 per cent in the first quarter of 2013. Higher spending on food – the category with the largest weight in the non-durable goods

| | |

| | Quarterly Bulletin June 2013 |

basket – was neutralised by slower growth in spending on beverages and tobacco in the first quarter of 2013. In addition, real spending on petroleum products declined, probably due to sharp increases in the price of petrol over the period. Concurrently, expenditure on transport services also contracted. However, spending on household fuel, medical products, and recreational and entertainment goods increased over the period.

Real spending by households on services – the largest component of household expenditure – increased at a rate of 1,1 per cent in the first quarter of 2013, slightly higher than the pace of increase attained in the final quarter of 2012. Higher spending on rent, household and medical services was partly offset by a decline in expenditure on transport and communication services. The increase in spending on miscellaneous services was partly neutralised by a slower pace of increase in net travel receipts from abroad.

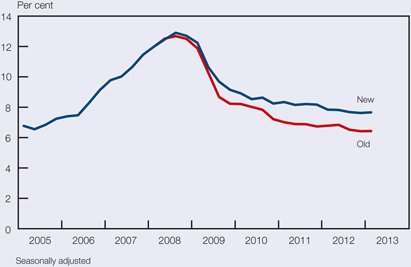

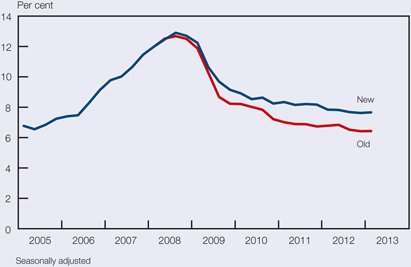

Box 1: Revision of the household debt-service cost ratio

The interest rates that apply to various types of loans differ significantly. A structural shift in credit extension in favour of non-mortgage lending, together with an extension of the range of interest rates reported to the South African Reserve Bank covering various types of credit extended to households, mandated a re-look at the methodology used to estimate the debt-service cost of the household sector in the national accounts statistics. As a percentage of total household debt, the non-mortgage debt of the household sector rose from 39 per cent in 2007 to 46 per cent in 2012 as so-called unsecured lending expanded briskly.

As shown in the accompanying graph, the revised debt-service cost as a percentage of disposable income has exceeded previously calculated ratios since the first quarter of 2008. The broad trends, however, remain roughly unchanged. The increasing gap between the two ratios mainly reflects the growing share of non-mortgage lending in total lending to the household sector, and the fact that the interest rates applicable to non-mortgage loans are generally significantly higher than typical mortgage interest rates.

Debt-service cost as a percentage of disposable income

Although still work in progress, the preliminary revised debt-service cost ratio is published as part of key national accounts statistics on page S–152 of this Quarterly Bulletin. The secondary impact of this revision on other national accounts aggregates will be made available at a later stage.

| | |

| Quarterly Bulletin June 2013 | |  |

Following an increase of 2,4 per cent in the fourth quarter of 2012, growth in real disposable income of households moderated somewhat to 2,2 per cent in the first quarter of 2013. The slower pace of increase in the disposable income of consumers could largely be attributed to slower growth in compensation of employees over the period. Even though the rate of increase in household debt slowed, the ratio of debt to disposable income remained at 75,4 per cent in the first quarter of 2013.

Against the backdrop of relatively low and steady interest rates in South Africa, the debt-service cost ratio of households edged higher from a revised 7,6 per cent in the fourth quarter of 2012 to 7,7 per cent in the first quarter of 2013. Owing to nominal disposable income increasing at a slower pace than household wealth, the ratio of household net wealth to disposable income advanced from 314 per cent in the fourth quarter of 2012 to 321 per cent in the first quarter of 2013.

Following a decline of 0,7 per cent in the fourth quarter of 2012, real final consumption expenditure by general government grew at an annualised rate of 3 per cent in the first quarter of 2013. The faster pace of spending was largely due to increased outlays on non-wage goods and services, which outweighed a slower pace of increase in compensation of employees. Outlays on non-wage goods and services reflected, inter alia, government’s intention to enhance the quality of education and healthcare, including the provision of antiretroviral medicines. Real final consumption expenditure by general government as a ratio of gross domestic product increased at broadly the same rate as recorded in the fourth quarter of 2012. However, growth in real spending by government, excluding armaments, tapered off from 3,6 per cent in the fourth quarter of 2012 to 3 per cent in the first quarter of 2013.

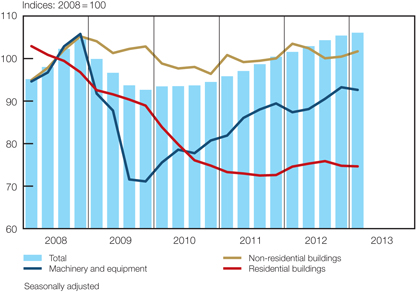

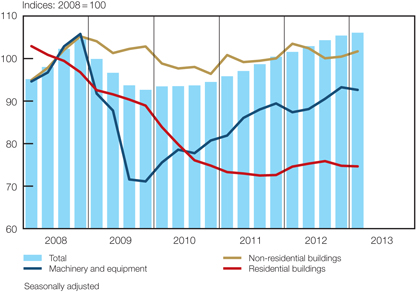

Growth in aggregate real gross fixed capital formation continued to slow in the first quarter of 2013. The annualised rate of increase in real capital spending moderated from 4,3 per cent in the fourth quarter of 2012 to 2,5 per cent in the first quarter of 2013. This deceleration, notwithstanding relatively low interest rates and the high priority assigned to government’s infrastructural development programme, could be ascribed to slower growth in real fixed capital outlays by both private business enterprises and public corporations.

Real gross fixed capital formation

Percentage change at seasonally adjusted annualised rates

| | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | |

| | | 2012 | | | 2013 | |

| Sector | | 1st qr | | | 2nd qr | | | 3rd qr | | | 4th qr | | | Year | | | 1st qr | |

Private business enterprises | | | 2,5 | | | | 2,7 | | | | 2,8 | | | | 3,8 | | | | 3,9 | | | | 2,8 | |

Public corporations | | | 11,0 | | | | 9,8 | | | | 10,6 | | | | 7,2 | | | | 9,1 | | | | 1,5 | |

General government | | | 4,9 | | | | 10,9 | | | | 10,3 | | | | 2,1 | | | | 8,5 | | | | 3,2 | |

Total | | | 4,6 | | | | 5,4 | | | | 5,6 | | | | 4,3 | | | | 5,7 | | | | 2,5 | |

Having accelerated for four consecutive quarters, annualised growth in real fixed capital expenditure by private business enterprises slowed to 2,8 per cent in the first quarter of 2013. Subdued outlays by all sectors, with the exception of the agriculture, construction and finance sectors, contributed to the slower investment activity by private business enterprises.

If the slower pace of capital spending were to continue, it could reduce the long-term growth potential of the economy and cause capacity constraints to develop and inflationary pressures to escalate. Both the mining and manufacturing sectors continued to face large-scale uncertainties, globally as well as domestically, which caused them to lower their capital spending on machinery and equipment significantly in the first quarter of 2013. The mining sector, more especially the gold and platinum mining industry, was negatively impacted by the volatility in the exchange value of the rand. By contrast, building contractors raised their capital spending, consistent with the improvement in market sentiment following renewed activity in high-density residential and non-residential building projects. In addition, business services increased their spending on computer and information technology equipment and computer software.

| | |

| | Quarterly Bulletin June 2013 |

Real gross fixed capital formation

The pace of increase in real spending by public corporations slowed from 7,2 per cent in the final quarter of 2012 to 1,5 per cent in the first quarter of 2013, mainly due to a deceleration in capital investment by the electricity sector. The slower growth in capital spending by the electricity sector resulted primarily from several weeks of continued industrial action at the Medupi power plant. However, meaningful capital spending on ongoing projects by Transnet, in particular the freight rail expansion project and the port terminals capacity expansion project, helped to counter the slower growth. In addition, the South African National Roads Agency (SANRAL) continued with its capital spending on roads, with the bulk of the spending taking place on non-toll roads.

Growth in capital expenditure by general government accelerated from an annualised rate of 2,1 per cent in the fourth quarter of 2012 to 3,2 per cent in the first quarter of 2013. Provincial and central government departments increased their capital spending in the areas of housing and construction works. These social and economic infrastructure spending programmes have been the key contributor throughout 2012 and have continued into the first quarter of 2013.

Subsequent to a decline of R4,1 billion in the level of real inventories in the fourth quarter of 2012, stocks increased by R4 billion in the first quarter of 2013. This accumulation of real inventory holdings boosted growth in real gross domestic expenditure by 1,5 percentage points in the first quarter of 2013, following a subtraction of 1,7 percentage points in the preceding quarter. The most significant increases in real inventory holdings in the first quarter of 2013 were recorded in the manufacturing and mining sectors.

Inventories were accumulated in the manufacturing sector due to increased imports of crude oil to replenish the low stock levels brought about by planned maintenance shutdowns conducted at some major refineries during the fourth quarter of 2012. In the mining sector levels of platinum and coal inventories increased in the first quarter of 2013.

Factor income

Growth over four quarters in total nominal factor income slowed from 7,6 per cent in the fourth quarter of 2012 to 6,9 per cent in the first quarter of 2013. This resulted from a decrease in the momentum of growth in remuneration of employees, while gross operating surpluses of business enterprises increased over the period.

| | |

| Quarterly Bulletin June 2013 | |  |

Measured over one year, growth of 7,4 per cent was recorded in total compensation of employees in the first quarter of 2013, lower than the rate of 9,2 per cent registered in the fourth quarter of 2012. Although a moderation in growth in compensation was recorded in most sectors of the economy, it was most prominent in the general government sector. Government’s salary and wage bill returned to normal in the first quarter of 2013, after sizeable bonuses were paid out in the fourth quarter of 2012. The moderation in compensation of employees was also broadly consistent with the relatively stable employment conditions in the formal economy over the period. Accordingly, the ratio of remuneration of employees to total factor income decreased from 51,9 per cent in the fourth quarter of 2012 to 51,8 per cent in the first quarter of 2013.

The year-on-year growth in the total gross operating surplus of business enterprises accelerated from 5,8 per cent in the fourth quarter of 2012 to 6,4 per cent in the first quarter of 2013. Increased growth mainly occurred in the agricultural and mining sectors. Mining operations expanded in the first quarter of 2013, following supply constraints at a major platinum mine and safety stoppages curbing operations during the preceding quarter. Accordingly, the share of the gross operating surplus in total factor income increased from 48,1 per cent in the final quarter of 2012 to 48,2 per cent in the first quarter of 2013.

Gross saving

The national saving ratio measured as gross saving as a percentage of gross domestic product increased from 12,8 per cent in the fourth quarter of 2012 to 14 per cent in the first quarter of 2013. Gross saving by the corporate sector and by general government increased, while the household saving ratio remained unchanged. The overall level of gross saving increased by an annualised R42,7 billion, thereby lowering South Africa’s dependency on foreign capital to finance gross capital formation from 33,7 per cent in the fourth quarter of 2012 to 29,3 per cent in the first quarter of 2013.

Gross saving by the corporate sector as a percentage of gross domestic product increased slightly from 13,8 per cent in the fourth quarter of 2012 to 14,2 per cent in the first quarter of 2013. The higher value of the gross operating surplus of business enterprises and lower dividend declarations contributed to this outcome.

Gross dissaving by general government as a ratio of gross domestic product moderated from a rate of 2,7 per cent in the fourth quarter of 2012 to 1,9 per cent in the first quarter of 2013. Rising tax collections alongside a slight moderation in government expenditure on certain items such as transfers to households and social benefit payments had a positive effect on the level of saving.

Gross saving by the household sector as a percentage of gross domestic product remained at 1,7 per cent for the fifth consecutive quarter in the first quarter of 2013. Although expenditure by households lost some momentum, the simultaneously slower pace of increase in disposable income resulted in the saving ratio being sustained over the period.

Employment

Alongside sluggish output growth in the domestic economy, employment in the formal non-agricultural sector of the economy decreased marginally in the fourth quarter of 2012. According to the Quarterly Employment Statistics (QES) survey by Statistics South Africa (Stats SA), employment decreased by 0,7 per cent on a seasonally adjusted and annualised basis in the fourth quarter of 2012, as both the public and private sector shed jobs during the period. Employment decreased by an estimated 14 200 jobs on a seasonally adjusted and annualised basis in the fourth quarter of 2012, bringing the level of total formal non-agricultural employment to an estimated 8,43 million at the end of December 2012.2 Employment growth in the South African economy slowed notably over the past year, with the annual average growth in total formal non-agricultural employment moderating from 2,2 per cent in 2011 to 1,2 per cent in 2012.

| | |

| | Quarterly Bulletin June 2013 |

Change in enterprise-surveyed formal non-agricultural employment by sector*

| | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | |

| | | Change in

4th qr 2012 | | | Change over four

quarters to

4th qr 2012 | | | Cumulative job

losses(-) gains(+) | |

| Sector | | Number | | | Per

cent | | | Number | | | Per

cent | | | 4th qr 2008

to 1st qr

2010 | | | 2nd qr 2010

to 4th qr

2012 | |

Finance, insurance, real-estate and business services | | | -600 | | | | -0,1 | | | | 10 000 | | | | 0,5 | | | | -163 400 | | | | 75 300 | |

Manufacturing | | | 2 600 | | | | 0,9 | | | | -2 400 | | | | -0,2 | | | | -118 300 | | | | -29 700 | |

Trade, catering and accommodation services | | | -17 200 | | | | -4,0 | | | | 9 200 | | | | 0,6 | | | | -75 700 | | | | 37 600 | |

Construction | | | 2 000 | | | | 1,9 | | | | 2 700 | | | | 0,6 | | | | -52 100 | | | | 16 900 | |

Total mining | | | 5 500 | | | | 4,3 | | | | 1 200 | | | | 0,2 | | | | -35 900 | | | | 27 500 | |

Gold mining | | | -1 000 | | | | -2,7 | | | | -2 500 | | | | -1,8 | | | | -8 900 | | | | -19 200 | |

Other mining | | | 6 500 | | | | 7,1 | | | | 3 700 | | | | 1,0 | | | | -27 000 | | | | 46 700 | |

Electricity | | | -600 | | | | -3,8 | | | | 2 600 | | | | 4,3 | | | | -3 300 | | | | 6 200 | |

Private transport, storage and communication services | | | 1 600 | | | | 2,5 | | | | -2 800 | | | | -1,0 | | | | -2 000 | | | | 4 700 | |

Community, social and personal services | | | -100 | | | | -0,1 | | | | 6 500 | | | | 1,6 | | | | 13 400 | | | | 11 200 | |

Private sector | | | -6 800 | | | | -0,4 | | | | 27 000 | | | | 0,4 | | | | -437 300 | | | | 149 600 | |

Provinces | | | -9 800 | | | | -3,5 | | | | 12 600 | | | | 1,2 | | | | 51 600 | | | | 80 700 | |

Local governments | | | 8 600 | | | | 13,8 | | | | 14 700 | | | | 5,8 | | | | 15 000 | | | | 29 400 | |

National departments | | | -12 300 | | | | -10,3 | | | | 1 700 | | | | 0,4 | | | | -800 | | | | 35 600 | |

Other public-sector enterprises | | | -3 300 | | | | -9,0 | | | | 1 600 | | | | 1,2 | | | | -7 800 | | | | 8 800 | |

Public transport, storage and communication services | | | 9 200 | | | | 36,8 | | | | 16 600 | | | | 15,6 | | | | -4 900 | | | | 19 200 | |

Total public sector | | | -7 500 | | | | -1,4 | | | | 47 200 | | | | 2,3 | | | | 53 100 | | | | 173 700 | |

Grand total | | | -14 200 | | | | -0,7 | | | | 74 200 | | | | 0,9 | | | | -384 200 | | | | 323 300 | |

| * | Seasonally adjusted. Components may not add to totals due to rounding |

Following two quarters of notable employment gains, the public sector shed 7 500 jobs in the fourth quarter of 2012, representing an annualised rate of decrease of 1,4 per cent. Labour paring was most pronounced at national departments, followed by provincial governments. Conversely, local governments and public-sector enterprises expanded their employment numbers further in the fourth quarter of 2012.

In the wake of the fairly pervasive and disruptive industrial action that occurred in the second half of 2012, private-sector employment contracted further in the fourth quarter of 2012, albeit at a much slower pace than in the third quarter. Job shedding was fairly pervasive throughout the private sector, with employment losses occurring in the trade, catering and accommodation services sector (at an annualised rate of 4,0 per cent); the electricity sector (3,8 per cent); the gold-mining sector (2,7 per cent); the finance, insurance, real-estate and business services sector (0,1 per cent) and the private community, social and personal services sector (0,1 per cent). These decreases were partly countered by employment gains in the non-gold mining sector (7,1 per cent); the private transport, storage and communication sector (2,5 per cent); the construction sector (1,9 per cent) and the manufacturing sector (0,9 per cent).

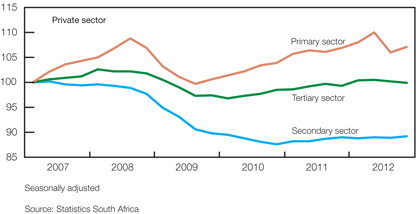

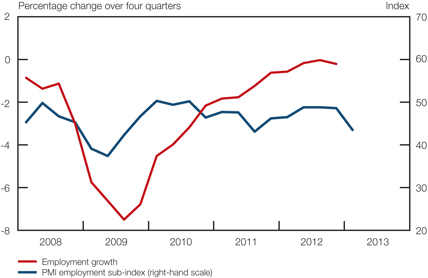

Following the decrease in employment in the third and fourth quarters of 2012, the private sector added only about 27 000 job opportunities in the year to the fourth quarter of 2012, representing a disappointing increase of only 0,4 per cent. The accompanying graph illustrates the loss of momentum in private-sector employment growth over the past two years; the private

| | |

| Quarterly Bulletin June 2013 | |  |

sector added 36 800 employment opportunities in the second half of 2010, only 20 300 in the second half of 2011, before shedding 37 600 in the same period of 2012. Although the decline in private-sector employment in the second half of 2012 was exacerbated by the labour unrest that occurred in various sectors of the economy over this period, the loss of underlying momentum was nevertheless evident, particularly in tertiary-sector employment. Despite the industrial action occurring predominantly in the primary sector of the economy, private tertiary-sector employment – representing about 65 per cent of total formal non-agricultural private-sector employment –decreased for two consecutive quarters up to the fourth quarter of 2012, shedding some 27 300 jobs over this period. The slowdown in private-sector employment growth is indicative of the difficulty facing the South African economy in addressing the high level of domestic unemployment, particularly in the current challenging global economic environment.

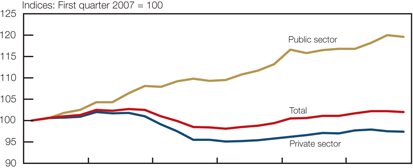

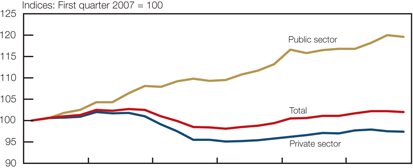

Formal non-agricultural employment

Following the loss of around 19 500 mining-sector jobs in the third quarter of 2012 largely due to the unprotected strike activity that pervaded the sector, employment in the mining sector increased by 5 500 in the fourth quarter of 2012, as some of the miners who were dismissed during the wildcat strikes were later re-hired. The non-gold mining sector in particular shed roughly 18 700 jobs in the third quarter of 2012, of which only about 6 500 were recovered in the fourth quarter. Conversely, employment levels in the gold-mining sector have contracted uninterruptedly since the first quarter of 2010, with the pace of job shedding accelerating for four consecutive quarters to an annualised rate of 2,7 per cent in the fourth quarter of 2012. Despite the acceleration in labour paring in the gold-mining sector over the short term, the sector lost only 2 500 employment opportunities in 2012, compared to a loss of 9 100 in 2011. The mining sector continues to face significant headwinds including, among others, slowing global demand for mining commodities, marked declines in a range of commodity prices, as well as rapidly rising input costs. In addition, amid this challenging domestic and global economic environment, a number of mining subsectors will conduct collective wage negotiations within a tense labour market milieu during the current round of negotiations.

| | |

| | Quarterly Bulletin June 2013 |

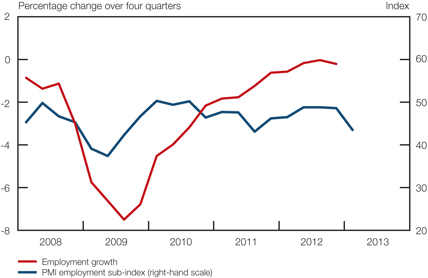

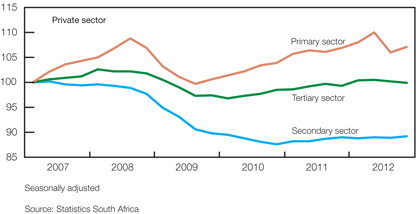

Alongside an acceleration in manufacturing output growth, employment increased at an annualised rate of 0,9 per cent in the fourth quarter of 2012, following three consecutive quarterly declines. Despite the pick-up in employment in the fourth quarter of 2012, the number of people employed in the manufacturing sector nevertheless continued to decrease compared with the same period in the preceding year. Recent outcomes of sentiment indicators are not supportive of employment creation in the manufacturing sector over the short term. After settling marginally below the neutral 50 index-level for three consecutive quarters, the Kagiso Purchasing Managers’ Index (PMI) employment sub-index decreased notably to 43,5 index points in the first quarter of 2013. In addition, according to the Bureau for Economic Research (BER) Manufacturing Survey for the first quarter of 2013, manufacturers expect general business conditions in the next twelve months to worsen.

Manufacturing employment growth and the Kagiso PMI employment sub-index

Employment levels in the manufacturing sector have been in a structural decline since the mid-1990s, largely due to a gradual loss of international competitiveness and increased mechanisation. In an attempt to enhance the competitiveness of the domestic manufacturing sector and to increase employment in the sector, the Department of Trade and Industry recently unveiled the new Industrial Policy Action Plan (IPAP) 2013/2014. The IPAP 2013/2014 aims to extend existing support programmes in the automotive, metals, agro-processing, clothing and textiles, as well as leather and footwear industries. In addition, it includes action plans in support of green industries, renewable energy efficiency and advanced manufacturing and materials, it sets standards and a strategic tariff regime to clamp down on illegal and substandard imports, and introduces a strategic focus on minerals and resources beneficiation.

Despite declining in the fourth quarter of 2012, employment in the electricity-generation sector nevertheless increased by 4,3 per cent from the fourth quarter of 2011 to the fourth quarter of 2012. Subsequent to the wave of labour unrest that occurred in certain sectors of the economy in the second half of 2012, Eskom has also been troubled by continuous industrial action and work stoppages in the opening months of 2013, threatening to delay its critical infrastructure expansion programme. Further setbacks, such as sharply reduced electricity imports from Mozambique due to flood-related damage to the transmission line from Cahorra Bassa, have also forced Eskom to continue its maintenance into the winter months when demand for electricity will peak.

| | |

| Quarterly Bulletin June 2013 | |  |

Following a decrease in the third quarter of 2012, employment levels in the construction sector increased at a rate of 1,9 per cent in the fourth quarter, resulting in a slight acceleration in year-on-year employment growth in the sector to a rate of 0,6 per cent in that quarter. Encouragingly, employment prospects in the construction sector appear to be improving. This is reflected in the second consecutive quarterly increase in the FNB/BER Civil Construction Confidence Index, which improved by 15 index points to a four-year high of 51 in the first quarter of 2013. Civil construction confidence improved largely as a result of increased profitability, even though growth in construction activity slowed somewhat. While government remains committed to increase infrastructure spending, capital expenditure in the mining sector could be inhibited by lower international commodity prices, labour market disruptions and a measure of policy uncertainty. Furthermore, the gradual recovery in the building industry appears to remain on track, as evidenced by the ongoing increase in the real value of building plans passed, as well as a second successive quarterly improvement in the FNB/BER Building Confidence Index to a level of 37 index points in the first quarter of 2013 – its highest level since the fourth quarter of 2010.

Indicative of the slowdown in tertiary-sector employment growth, employment in the finance, insurance, real-estate and business services sector decreased for three successive quarters up to the fourth quarter of 2012, at rates of 1,0 per cent, 1,7 per cent and 0,1 per cent, respectively. Despite these decreases, employment in this sector increased by about 10 000 job opportunities in the year to the fourth quarter of 2012.

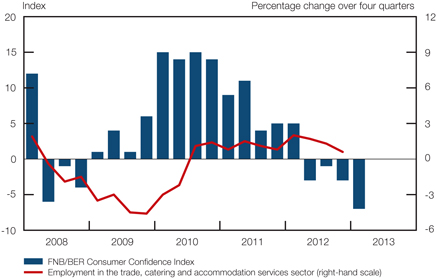

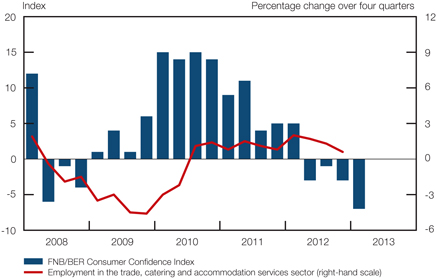

Together with the continued slowdown in output growth in the trade, catering and accommodation services sector, employment in this sector decreased by around 17 200 job opportunities in the fourth quarter of 2012. As a result, year-on-year growth in employment in the sector slowed to a modest rate of 0,6 per cent in the fourth quarter of 2012. Disappointingly, the FNB/BER Consumer Confidence Index declined further by four index points to a nine-year low of—7 index points in the first quarter of 2013. This index is currently at its lowest level since the first quarter of 2004 and at an even more depressed level than at its most recent low point of—6 registered during the global financial crisis in the second quarter of 2008. The BER noted in its Retail Trade Survey for the first quarter of 2013 that retail sales growth is set to slow further, dimming the prospects for meaningful employment creation in the trade, catering and accommodation services sector in the short term.

Employment in the trade, catering and accommodation services sector and the FNB/BER Consumer Confidence Index

| | |

| | Quarterly Bulletin June 2013 |

According to the Quarterly Labour Force Survey (QLFS) conducted by Stats SA, there were approximately 13,6 million persons employed in South Africa in the first quarter of 2013, representing an increase of 199 000 people compared with the same period in 2012. Total employment decreased by 44 000 job opportunities from the fourth quarter of 2012 to the first quarter of 2013 on a non-seasonally adjusted basis. Disappointingly, the number of unemployed persons increased by an estimated 75 000 in the year to the first quarter of 2013, partially explained by an expanding labour force and probably more people actively looking for a job as evidenced by the decrease of 5 000 in the number of discouraged work-seekers over the same period. The official unemployment rate in the South African economy consequently came to 25,2 per cent in the first quarter of 2013, the same rate as in the first quarter of 2012.

Labour market statistics

| | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | |

| | | 2012 | | | 2013 | |

| | | Mar | | | Jun | | | Sep | | | Dec | | | Mar | |

| | | (000’s) | | | (000’s) | | | (000’s) | | | (000’s) | | | (000’s) | |

a. Total employment | | | 13 422 | | | | 13 447 | | | | 13 645 | | | | 13 577 | | | | 13 621 | |

b. Total unemployment (official definition) | | | 4 526 | | | | 4 470 | | | | 4 667 | | | | 4 501 | | | | 4 601 | |

c. Total economically active (= a + b) | | | 17 948 | | | | 17 916 | | | | 18 313 | | | | 18 078 | | | | 18 222 | |

d. Total not economically active | | | 14 838 | | | | 14 987 | | | | 14 705 | | | | 15 050 | | | | 15 017 | |

e. Total aged 15–64 years (= c + d) | | | 32 786 | | | | 32 903 | | | | 33 018 | | | | 33 128 | | | | 33 240 | |

f. Official unemployment rate (= b*100/c) | | | 25,2 | % | | | 24,9 | % | | | 25,5 | % | | | 24,9 | % | | | 25,2 | % |

Source: Statistics South Africa, Quarterly Labour Force Survey

Labour cost and productivity

The year-on-year pace of increase in nominal remuneration per worker in the formal non-agricultural sector of the economy moderated notably from 8,9 per cent in the third quarter of 2012 to 7,0 per cent in the fourth quarter. Although nominal wage growth decelerated in both the public and private sectors of the economy, the moderation was most pronounced in the public sector, where wage growth slowed from 10,9 per cent in the third quarter of 2012 to 6,2 per cent in the fourth quarter. Nonetheless, the real take-home pay of those gainfully employed in the formal non-agricultural sector accelerated marginally from an annual average rate of 1,7 per cent in 2011 to 2,0 per cent in 2012.

The deceleration in nominal remuneration growth per worker in the public sector in the fourth quarter of 2012 could be ascribed to a moderation in the year-on-year pace of increase in the wages per worker paid by provinces and local governments to 5,3 per cent and 0,4 per cent respectively. Furthermore, the nominal remuneration per worker in the public transport, storage and communication sector decreased by 7,2 per cent in the year to the fourth quarter of 2012. By contrast, wage growth for employees of national departments accelerated further to a year-on-year rate of 14,8 per cent in the fourth quarter of 2012.

Private-sector wage growth remained marginally above 7,0 per cent, on average, in 2011 and 2012, moderating from a year-on-year rate of 7,7 per cent in the third quarter of 2012 to 7,1 per cent in the fourth quarter. Despite the slight moderation, year-on-year increases in nominal remuneration per worker remained above the inflation target range in all subsectors, with the exception of the mining sector. Remuneration per worker increased at the fastest pace in the electricity sector (14,5 per cent), followed by the trade, catering and accommodation services sector (10,6 per cent); the private transport, storage and communication sector (9,4 per cent); the manufacturing sector (8,7 per cent); the private community, social and personal services sector (8,1 per cent); and the construction sector (7,9 per cent). By contrast, nominal remuneration growth in the mining sector decreased by 3,2 per cent in the fourth quarter of 2012, as wage growth slowed notably to 3,2 per cent in the gold-mining sector, while wages

| | |

| Quarterly Bulletin June 2013 | |  |

per worker actually decreased by 5,1 per cent in the non-gold mining sector. The decrease in wages per worker in the non-gold mining sector largely resulted from the high base created in the fourth quarter of 2011, due to extraordinary bonus payments at the time.

The average wage settlement rate in collective bargaining agreements accelerated from 7,6 per cent in 2012 to 7,9 per cent in the first quarter of 2013, according to Andrew Levy Employment Publications. The number of working days lost due to strike action rose to 875 000 in the first quarter of 2013, compared with 700 000 for the corresponding period in 2012. Strike activity in a number of sectors resulted from a spillover of events in 2012. The disruptive labour unrest that occurred during the second half of 2012 suggests that some contestation may continue to characterise the labour market in coming quarters, as a number of multi-year wage agreements are due to be negotiated in the second and third quarters of 2013.

Year-on-year growth in employment in the formal non-agricultural sector of the economy moderated at a slightly slower pace than that of output in the fourth quarter of 2012, resulting in labour productivity growth decelerating marginally from 1,4 per cent in the third quarter of 2012 to 1,2 per cent in the fourth quarter. However, productivity growth in the manufacturing sector accelerated to 3,2 per cent in the year to the fourth quarter of 2012, as output increased alongside a further decline in the level of employment. Remuneration growth in the formal non-agricultural sector of the economy moderated more than output growth, resulting in year-on-year growth in nominal unit labour cost decelerating from 7,4 per cent in the third quarter of 2012 to 5,7 per cent in the fourth quarter. Similarly, the year-on-year pace of increase in unit labour cost in the manufacturing sector decelerated from 7,0 per cent in the third quarter of 2012 to 5,3 per cent in the fourth quarter, as remuneration growth slowed while output growth gathered pace. However, when assessing unit labour cost developments by applying the broader national accounts measure of compensation of employees per unit of output (i.e., also including the agricultural sector and the informal sector), year-on-year growth in unit labour cost accelerated from 5,5 per cent in the third quarter of 2012 to 6,8 per cent in the fourth quarter.

Real wages, productivity and nominal unit labour cost

Prices

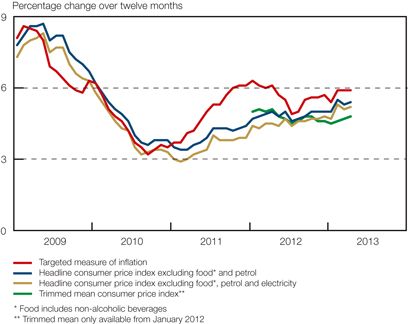

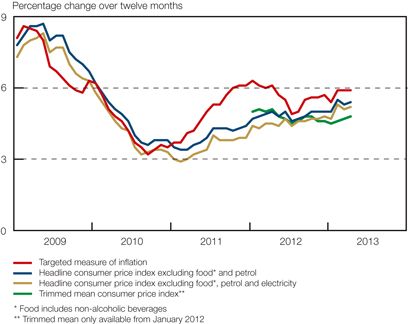

Within an environment of slowing economic growth and moderating inflation in most advanced economies, domestic headline consumer price inflation nevertheless continued to accelerate up to the opening months of 2013. However, having accelerated gradually from a recent low of 4,9 per cent in July 2012 to 5,9 per cent in February 2013, twelve-month headline consumer

| | |

| | Quarterly Bulletin June 2013 |

price inflation then levelled off at 5,9 per cent in March and April 2013, thereby remaining within the inflation target range of 3 to 6 per cent for twelve consecutive months since May 2012.3 The acceleration in consumer price inflation could initially be attributed largely to a quickening in price inflation of consumer goods; notably that of petrol and food. However, consumer services price inflation also accelerated somewhat in recent months. Renewed wage cost pressure amid an unsettled labour market environment, as well as the possible lagged pass-through effect of the depreciation in the exchange rate of the rand, continue to pose a significant further upside risk to the domestic inflation outlook.

Encouragingly, domestic producer price inflation moderated throughout 2012 and in the opening months of 2013. From February 2013 Stats SA applied a new methodology to calculate the producer price index (PPI). This implied that the headline PPI for domestic output was discontinued and replaced with five industry-specific PPIs which reflect the stages of domestic production, namely a final manufactured goods PPI; an intermediate manufactured goods PPI; an electricity and water PPI; a mining PPI; and an agriculture, forestry and fishing PPI. Producer price inflation for final manufactured goods – the new headline PPI, since it best represents the effects of price changes through the stages of production – decelerated from a recent high of 8,8 per cent in February 2012 to 5,4 per cent in April 2013. The moderation in final manufactured producer price inflation in the opening months of 2013 resulted largely from a deceleration in price inflation of beverages, non-metallic mineral products, as well as petroleum and chemicals. Producer price inflation for electricity and water has decelerated steadily since the middle of 2011, amounting to a still-high rate of 11,4 per cent in March 2013, before quickening again to 12,9 per cent in April. Conversely, producer price inflation for mining accelerated notably in recent months to a rate of 8,6 per cent in March 2013, as price inflation in coal and gas, gold and other metal ores, as well as non-ferrous metal ores picked up pace. Producer price inflation for mining then decelerated notably to 4,5 per cent in April 2013, as price inflation moderated in all the mining sub-categories in the month.

Producer and consumer prices

Aiding the moderation in producer price inflation, inflation in imported commodity prices slowed notably from a recent high of 9,4 per cent in September 2012 to 3,3 per cent in January 2013, as international crude oil prices softened in the closing months of 2012. However, the notable increase in crude oil prices in January and February 2013, coupled with the depreciation in the exchange rate of the rand, resulted in a renewed acceleration in imported producer price inflation to 4,7 per cent in March 2013. Imported producer price inflation subsequently moderated to 4,1 per cent in April 2013, largely due to a deceleration in imported mining producer price inflation and a decrease in international crude oil prices.

| | |

| Quarterly Bulletin June 2013 | |  |

Consumer goods price inflation moderated somewhat from a twelve-month rate of 5,3 per cent in November 2012 to 4,8 per cent in January 2013, before accelerating again to 5,1 per cent in April. The recent acceleration in consumer goods price inflation resulted largely from an acceleration in price inflation in semi-durable goods from 2,4 per cent in December 2012 to 3,2 per cent in April 2013. Non-durable goods price inflation decelerated marginally from 7,3 per cent in January and February 2013 to 7,2 per cent in April, while durable goods prices declined at a faster pace, with the twelve-month rate of decline picking up pace from 0,2 per cent in December 2012 to 0,5 per cent in April 2013. The slight acceleration in consumer goods price inflation in the opening months of 2013 resulted from a pick-up in price inflation in the transport goods category from 2,8 per cent in January 2013 to 6,2 per cent in March, as well as in the recreation and culture goods category from 2,2 per cent to 3,7 per cent over the same period. Price inflation in these two consumer goods categories then moderated somewhat in April 2013. Within the consumer goods basket, the housing and utilities category, the food and non-alcoholic beverages category and the alcoholic beverages and tobacco category registered rates of increase in excess of the upper limit of the inflation target range of 6 per cent in April 2013.

Consumer services price inflation remained very stable near the upper end of the inflation target range throughout 2012, before accelerating to 6,6 per cent in April 2013. The quickening in services price inflation resulted largely from an acceleration in price inflation in the miscellaneous services component from 5,2 per cent in January 2013 to 8,2 per cent in April, and to a lesser extent in recreation and culture services from 3,6 per cent in December 2012 to 5,4 per cent in April 2013. Within the miscellaneous services category, the cost of insurance services accelerated notably, with the cost of health insurance in particular increasing briskly at a rate of 10,2 per cent in April 2013. Apart from miscellaneous services prices, the prices of transport, education and health services increased at rates in excess of the upper limit of the inflation target range in April 2013. Conversely, despite accelerating somewhat in recent months, communication services prices increased at a modest rate of only 1,4 per cent in April 2013.

Although in the wake of drastically lower US grain crops food price increases have been one of the chief contributors to the acceleration in headline consumer price inflation in the second half of 2012, recent indications are that inflationary pressures emanating from food prices have eased somewhat. Manufactured producer food price inflation decelerated from a recent peak of 11,7 per cent in January 2012 to 5,9 per cent in January 2013, before accelerating somewhat to 6,5 per cent in April. Similarly, agricultural producer price inflation – almost exclusively comprising agricultural food products – moderated from a recent high of 4,9 per cent in November 2012 to -0,2 per cent March 2013, before accelerating again to 1,3 per cent in April.

The deceleration in producer food price inflation assisted in moderating food price inflation at the consumer level from a recent high of 7,5 per cent in November 2012 to 5,9 per cent in March 2013, before accelerating to 6,3 per cent in April. The slowdown in consumer food price inflation resulted largely from moderations in bread, cereals and meat price inflation – together accounting for 57 per cent of the consumer food price basket. In addition, year-on-year price inflation decelerated in six of the nine consumer food price categories from February 2013 to March. Despite the general moderation in food price inflation, price increases in five of the nine categories in the consumer food price basket nevertheless exceeded the upper limit of 6 per cent of the inflation target range in April 2013, the overshooting categories being fish; milk, eggs and cheese; vegetables; sugar, sweets and desserts; and other food products. Encouragingly, global agricultural commodity prices have declined on average by almost 20 per cent since their recent peak in the opening months of 2012 and, barring adverse weather conditions, are expected to moderate further.

| | |

| | Quarterly Bulletin June 2013 |

Food prices

When the impact of the more volatile food, non-alcoholic beverages and petrol prices is omitted from the calculation of targeted headline consumer price inflation, underlying inflation accelerated gradually from 4,6 per cent in July 2012 to 5,5 per cent in February 2013, before moderating to 5,4 per cent in April. Similarly, when also excluding the impact of electricity prices from the calculation, consumer price inflation accelerated steadily throughout 2012 and amounted to 5,3 per cent in February 2013, before slowing to 5,2 per cent in April.

Underlying measures of consumer price inflation

| | |

| Quarterly Bulletin June 2013 | |  |

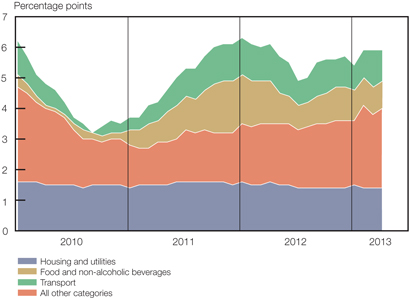

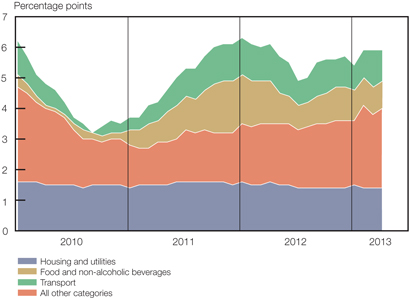

An additional measure of underlying inflation, namely the trimmed mean consumer price inflation, accelerated marginally from 4,5 per cent in January 2013 to 4,8 per cent in April. Although remaining fairly muted, the pick-up in underlying inflation seems to suggest that inflationary pressures have become slightly more broad-based in recent months. This is supported by the accompanying graph, depicting the contributions of selected categories to the annual percentage change in the headline consumer price index. The contribution of the “other” remaining categories – apart from housing and utilities, food and non-alcoholic beverages and transport – to the acceleration in headline consumer price inflation in recent months has been increasing steadily, suggesting a broadening of inflationary pressure.

Contribution of selected categories to the annual percentage change in the consumer price index

An analysis of price changes based on the classification of individual consumption by purpose (COICOP) categories also reveals a slight broadening of inflationary pressure in the economy. The year-on-year rates of increase in seven of the twelve categories did not exceed the upper limit of the inflation target range in April 2012, with six categories recording price increases which fluctuated between 3 to 6 per cent, while the remaining category increased at a rate below 3 per cent. The five categories that increased at rates in excess of 6 per cent in April 2013 – together accounting for 55 per cent of the total consumer price basket – were food and non-alcoholic beverages, alcoholic beverages and tobacco, transport, education and miscellaneous goods and services. In addition, the twelve-month rates of increase in five categories decelerated in April 2013, while two categories recorded the same rate of increase and the rates of increase in the remaining five categories accelerated when compared to March 2013.

Administered price inflation moderated somewhat from 9,8 per cent in September 2012 to 8,5 per cent in January 2013. Thereafter, it accelerated once again to 10,6 per cent in March 2013, before moderating to 8,9 per cent in April. The recent movements in administered price inflation can largely be ascribed to changes in domestic petrol prices; petrol price inflation decelerated from 17,6 per cent in September 2012 to 11,6 per cent in January 2013, quickened again to 16,4 per cent in March and moderated to 10,4 per cent in April. The inland price of petrol increased by a cumulative R1,34 per litre from January 2013 to April, reflecting higher

| | |

| | Quarterly Bulletin June 2013 |

international crude oil prices in the opening months of 2013. Encouragingly, the inland price of petrol decreased by 73 cents per litre in May 2013, as crude oil prices subsequently softened due to renewed fears of a slowdown in the global economic recovery.

Headline CPI inflation in COICOP categories

Percentage changes over twelve months

| | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | |

| | | 2013 | |

| | | Weights | | | Feb | | | Mar | | | Apr | |

Food and non-alcoholic beverages | | | 15,41 | | | | 6,1 | | | | 5,7 | | | | 6,2 | |

Alcoholic beverages and tobacco | | | 5,43 | | | | 7,9 | | | | 5,8 | | | | 6,5 | |

Clothing and footwear | | | 4,07 | | | | 3,2 | | | | 2,9 | | | | 3,1 | |

Housing and utilities | | | 24,52 | | | | 5,9 | | | | 5,9 | | | | 5,8 | |

Household content, maintenance and equipment | | | 4,79 | | | | 3,2 | | | | 3,2 | | | | 3,2 | |

Health | | | 1,46 | | | | 4,4 | | | | 4,0 | | | | 4,8 | |

Transport | | | 16,43 | | | | 5,5 | | | | 7,5 | | | | 6,2 | |

Communication | | | 2,63 | | | | 0,1 | | | | 1,0 | | | | 0,8 | |

Recreation and culture | | | 4,09 | | | | 3,6 | | | | 4,5 | | | | 4,0 | |

Education | | | 2,95 | | | | 8,9 | | | | 9,0 | | | | 9,0 | |

Restaurants and hotels | | | 3,50 | | | | 7,2 | | | | 6,0 | | | | 5,9 | |

Miscellaneous goods and services | | | 14,72 | | | | 7,5 | | | | 7,4 | | | | 7,5 | |

All items headline CPI | | | 100,00 | | | | 5,9 | | | | 5,9 | | | | 5,9 | |

When excluding the effect of petrol prices from the calculation of administered prices, this rate of increase accelerated from 7,1 per cent in July 2012 to 7,8 per cent in April 2013. Similarly, when also excluding electricity prices from the above-mentioned calculation, administered price inflation accelerated from 6,6 per cent in September 2012 to 8,2 per cent in April 2013. The sharp depreciation in the exchange value of the rand in May 2013 could exert further upward pressure on administered price inflation in the months ahead.

Administered price inflation categories

Percentage change over twelve months

| | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | |

| | | 2013 | |

| | | Weights | | | Feb | | | Mar | | | Apr | |

Housing and utilities | | | 7,03 | | | | 9,5 | | | | 9,5 | | | | 9,4 | |

Transport | | | 6,08 | | | | 11,7 | | | | 15,8 | | | | 10,0 | |

Communication | | | 2,30 | | | | 0,6 | | | | 1,8 | | | | 1,6 | |

Recreation and culture | | | 0,06 | | | | 0,0 | | | | 0,0 | | | | 0,0 | |

Education | | | 2,95 | | | | 9,0 | | | | 9,0 | | | | 9,0 | |

Restaurants and hotels | | | 0,06 | | | | 9,6 | | | | 9,6 | | | | 9,6 | |

Total administered prices | | | 18,48 | | | | 8,9 | | | | 10,6 | | | | 8,9 | |

Average inflation expectations for 2013, as reflected by the Inflation Expectations Survey conducted by the BER in the first quarter of 2013, were almost unchanged from the previous quarter and remained anchored around the upper limit of the inflation target range of 3 to 6 per cent. Inflation is expected to average 6,0 per cent in 2013 and 2014, before ticking up marginally to 6,1 per cent in 2015. Whereas the inflation expectations of financial analysts have risen, business executives and trade unions adjusted their expectations for 2013 downwards. Regarding 2014, financial analysts see inflation at 5,5 per cent, trade unions anticipate a rate of

| | |

| Quarterly Bulletin June 2013 | |  |

5,9 per cent and business executives expect a much higher inflation rate of 6,5 per cent. In the fourth quarter of 2012, households raised their inflation expectations for the next twelve months by a significant 0,8 percentage points to 7,2 per cent – their highest expected rate in two years. However, in the first quarter of 2013 households’ inflation expectations moderated to a rate of 6,8 per cent.

Headline consumer price inflation expectations

Per cent, as surveyed in the first quarter of 2013

| | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | |

| Average inflation expected for: | | Financial

analysts | | | Business

representatives | | | Trade union

representatives | | | All surveyed

participants | |

2013 | | | 5,8 | | | | 6,3 | | | | 5,9 | | | | 6,0 | |

2014 | | | 5,5 | | | | 6,5 | | | | 5,9 | | | | 6,0 | |

2015 | | | 5,6 | | | | 6,6 | | | | 6,2 | | | | 6,1 | |

Source: Bureau for Economic Research, Stellenbosch University

| | |

| | Quarterly Bulletin June 2013 |

Foreign trade and payments

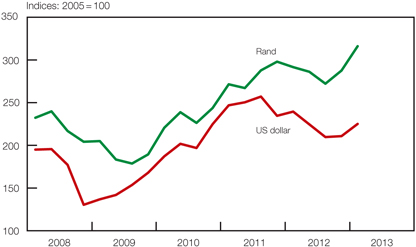

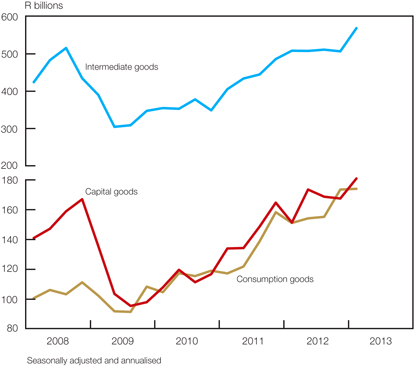

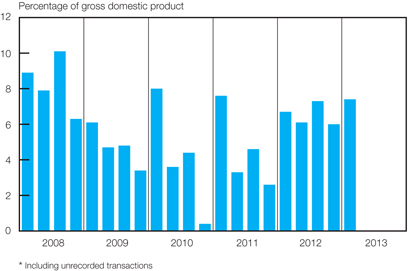

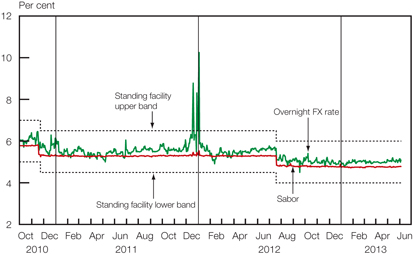

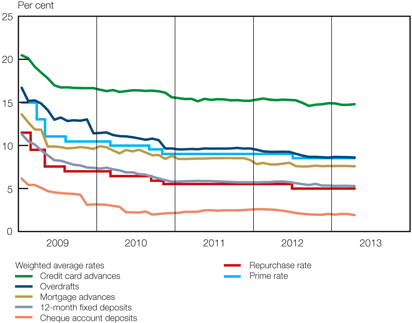

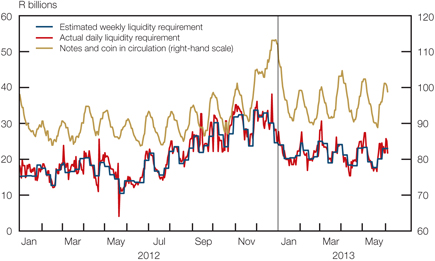

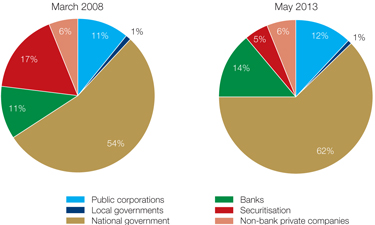

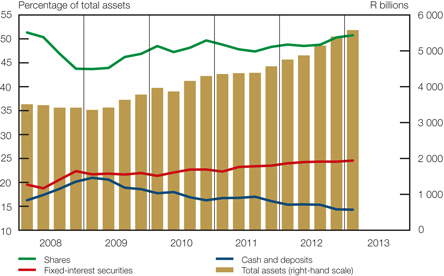

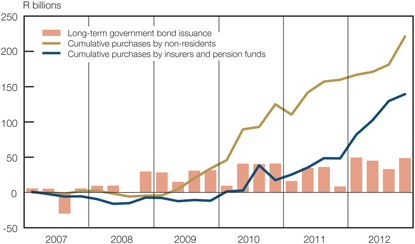

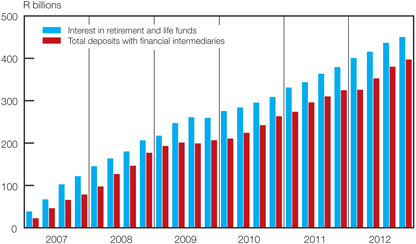

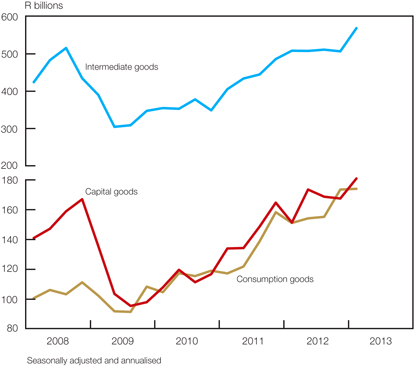

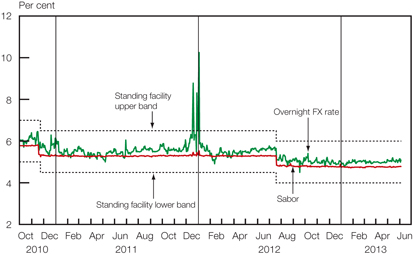

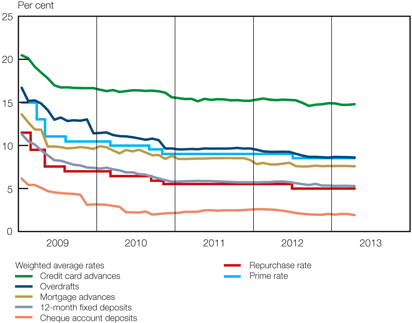

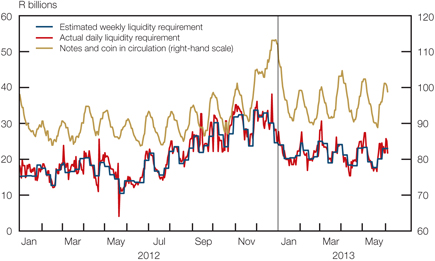

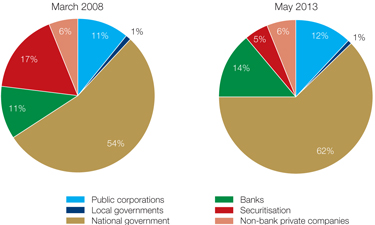

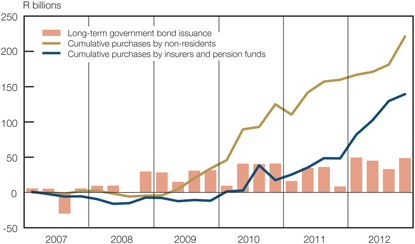

International economic developments