Exhibit 99.E

© South African Reserve Bank

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without fully acknowledging the Quarterly Bulletin of the South African Reserve Bank as the source. The contents of this publication are intended for general information only and are not intended to serve as financial or other advice. While every precaution is taken to ensure the accuracy of information, the South African Reserve Bank shall not be liable to any person for inaccurate information or opinions contained in this publication.

| | | | |

Enquiries relating to this Bulletin should be addressed to: | | | | |

| |

Head: Research Department | | | | |

South African Reserve Bank | | | | |

P O Box 427 | | | | |

Pretoria 0001 | | | | |

Tel. +27 12 313-3668/3676 | | | | |

| |

http://www.reservebank.co.za | | | ISSN 0038-2620 | |

| | |

| | Quarterly Bulletin March 2014 |

Contents

Quarterly Economic Review

| | | | |

Introduction | | | 1 | |

Domestic economic developments | | | 4 | |

Domestic output | | | 4 | |

Real gross domestic expenditure | | | 8 | |

Factor income | | | 13 | |

Gross saving | | | 14 | |

Employment | | | 14 | |

Labour cost and productivity | | | 22 | |

Prices | | | 23 | |

Foreign trade and payments | | | 30 | |

International economic developments | | | 30 | |

Current account | | | 33 | |

Financial account | | | 38 | |

Foreign debt | | | 40 | |

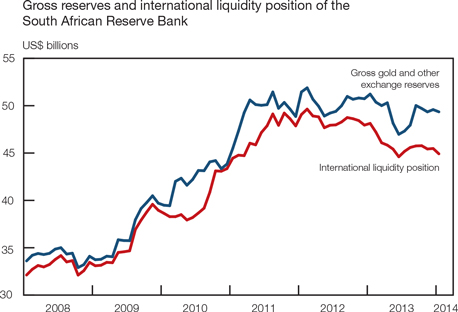

International reserves and liquidity | | | 42 | |

Exchange rates | | | 43 | |

Monetary developments, interest rates and financial markets | | | 48 | |

Structural and regulatory issues in 2013 and early 2014 | | | 48 | |

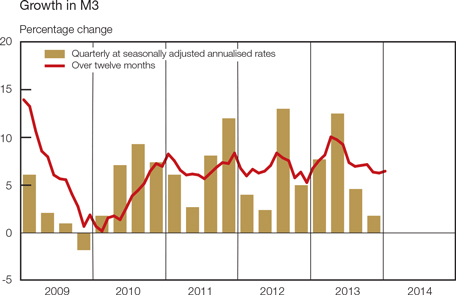

Money supply | | | 52 | |

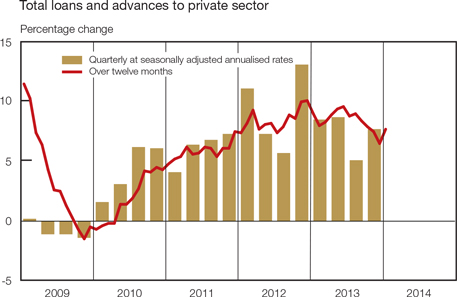

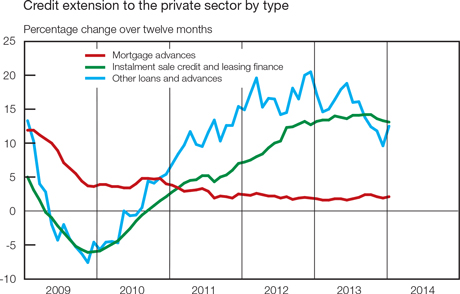

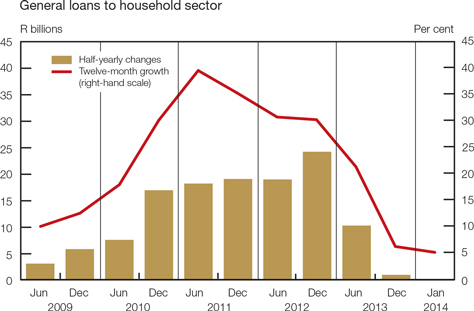

Credit extension | | | 54 | |

Interest rates and yields | | | 58 | |

Money market | | | 62 | |

Bond market | | | 63 | |

Share market | | | 65 | |

Market for exchange-traded derivatives | | | 66 | |

Real-estate market | | | 67 | |

Non-bank financial intermediaries | | | 68 | |

Flow of funds | | | 69 | |

Public finance | | | 70 | |

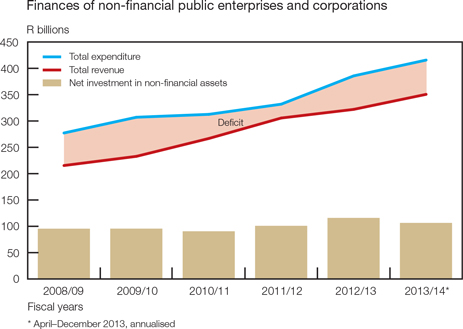

Non-financial public-sector borrowing requirement | | | 70 | |

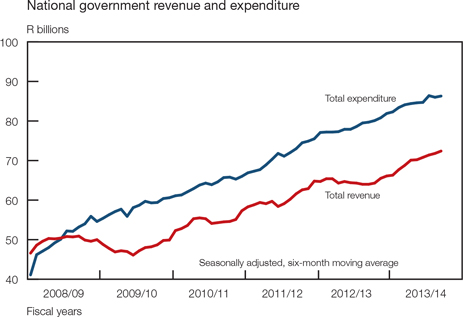

Budget comparable analysis of national government finance | | | 72 | |

The Budget for fiscal 2014/15 to 2016/17 | | | 78 | |

Fiscal policy stance | | | 78 | |

| |

Statement issued by Gill Marcus, Governor of the South African Reserve Bank | | | | |

| |

Statement of the Monetary Policy Committee 29 January 2014 | | | 83 | |

| |

Notes to tables | | | 88 | |

| |

Statistical tables | | | | |

| |

Contents | | | S–0 | |

Statistical tables | | | S–2 | |

Key information | | | S–144 | |

| | |

| Quarterly Bulletin March 2014 | |  |

Quarterly Economic Review

Introduction

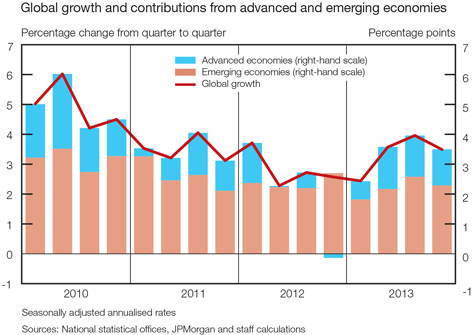

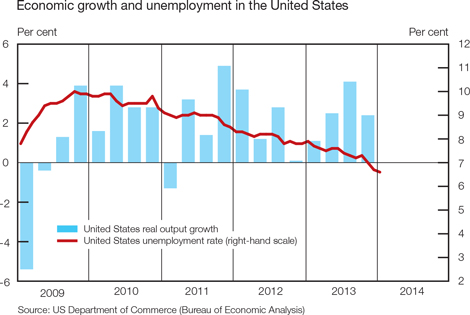

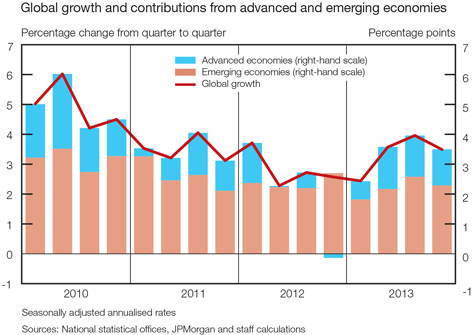

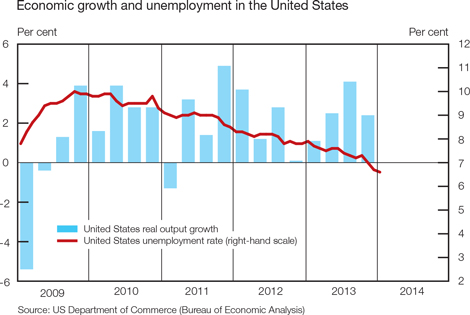

Global economic activity, despite remaining fragile and uneven, has maintained a firmer undertone from the second quarter of 2013. However, the overall growth momentum slowed somewhat in the final quarter of the year after peaking in the third quarter as growth moderated in several emerging Asian and European countries, as well as in advanced economies. While the continued fragility of the recovery in the euro area and fears of deflation prompted the European Central Bank (ECB) to reduce its key policy interest rate in November 2013, signs of improvement in economic conditions brought the Federal Reserve in the United States (US) to announce in December 2013 the first cutback in the pace of its purchases of securities – while still maintaining ultra-low policy interest rates.

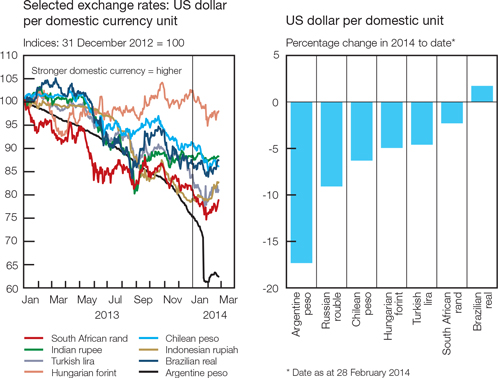

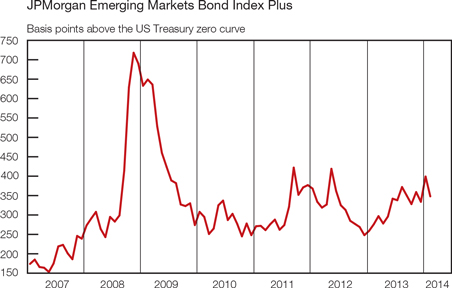

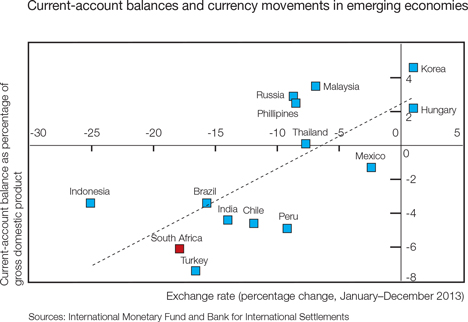

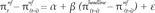

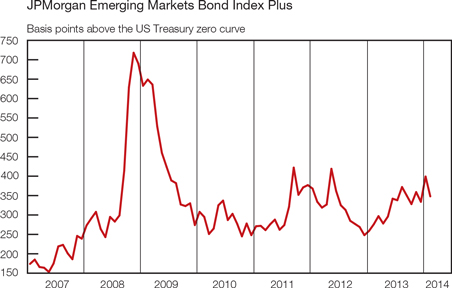

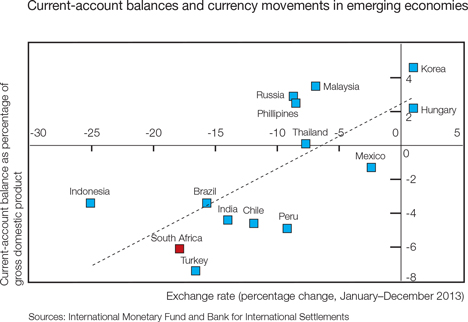

The actual onset of the tapering of quantitative easing influenced sentiment in global financial markets, reducing the relative attractiveness of exposure to emerging-market assets and triggering portfolio adjustment. Against this background, several emerging-market economies with large current-account deficits recently experienced significant currency depreciations and heightened inflation. However, international commodity prices remained well contained and with the world economy continuing to function below full capacity, global inflation remained fairly benign during the period under review, although significantly higher in emerging economies than in advanced economies.

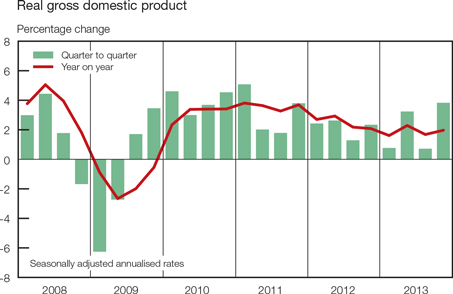

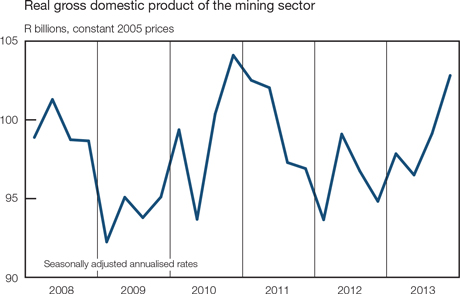

The South African economy recorded erratic quarter-to-quarter growth in 2013, with the overall pace of expansion in real output for the year as a whole a disappointing 1,9 per cent. Apart from longer-term impediments to growth such as constrained electricity supply and logistical bottlenecks, production in the first quarter of 2013 was held back by industrial action, fire damage at a large steel mill and maintenance of production facilities, while widespread strike action again disrupted production in the third quarter. From the low base established in the third quarter, the subsequent normalisation of production propelled growth to an annualised rate of 3,8 per cent in the fourth quarter of the year. South Africa’s erratic growth pattern could well continue in the first quarter of 2014, with protracted industrial action again weighing on production.

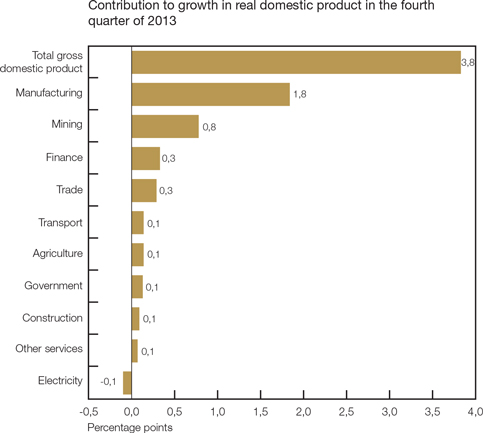

As labour relations normalised, a rebound in manufacturing production, especially in the motor vehicles and components subsector, made the largest contribution to the buoyant rate of real economic growth in the fourth quarter of 2013. Mining production also rose briskly over the same period, led by diamonds, gold and platinum group metals. The trade sector similarly made a significant contribution to growth in the fourth quarter as rising retail and wholesale sales more than fully countered a decline in motor trade activity. Real agricultural production registered a strong performance in the fourth quarter of 2013 primarily on account of an increase in field crop production, particularly in sugar cane. Rising civil construction activity was reflected in an increase in real value added by the construction sector, whereas real electricity production declined in the fourth quarter, partly as a result of supply constraints.

The gradual consolidation of household finances continued in the final quarter of 2013, as the pace of increase of real final household consumption expenditure slowed marginally further and the ratio of household debt to disposable income edged lower. Real spending on durable and semi-durable goods rose at a somewhat slower pace in the fourth quarter, with expenditure on furniture and appliances contracting along with slower growth in spending on personal transport equipment and on computers and related equipment.

The pace of increase in real final consumption expenditure by general government edged higher in the fourth quarter of 2013 as outlays on non-wage goods and services increased, reflecting in part the expenditure related to the state funeral of the former president of South Africa, Mr Nelson Mandela, alongside somewhat higher real compensation of government employees.

| | |

| Quarterly Bulletin March 2014 | |  |

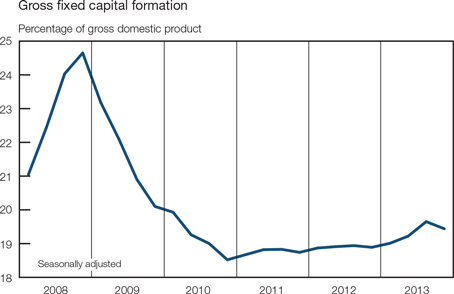

Growth in real capital expenditure moderated notably in the fourth quarter of 2013. This was due to a sharp deceleration in the pace of growth in real fixed capital formation by private business enterprises, as real outlays in the manufacturing sector slowed. Capital spending on wind farms and solar plants for the generation of electricity, which gained in significance in 2013, continued at a more moderate pace in the final quarter of the year.

While constituting less than a fifth of the country’s overall fixed capital formation, real capital spending by general government advanced at a brisk pace in the final quarter of 2013, broadly maintaining its momentum of the previous quarter. Priority areas included the construction and upgrading of roads, schools and hospitals, with the provincial governments and local authorities in particular stepping up their expenditure. At the same time the level of real fixed capital expenditure by public corporations essentially moved sideways – albeit at a high level, mainly reflecting ongoing spending by the electricity and transport sectors.

The accumulation of inventories recorded in the first three quarters of 2013 made way for destocking in the final quarter of the year. The reversal in stockpiling in the final quarter resulted mainly from a de-accumulation of inventories in the manufacturing sector and in the strike-prone mining sector, reflecting fairly subdued business confidence levels.

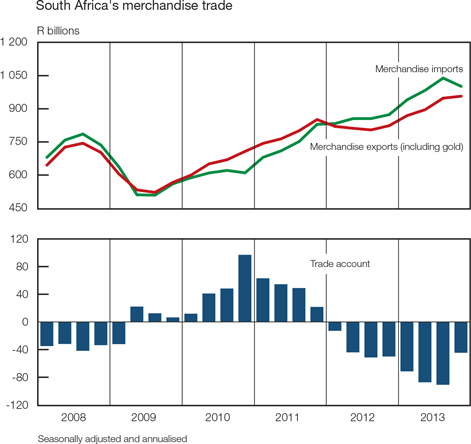

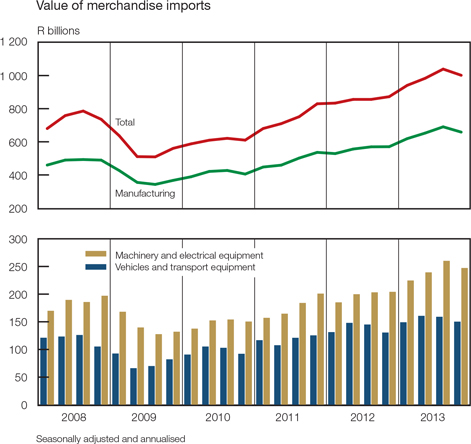

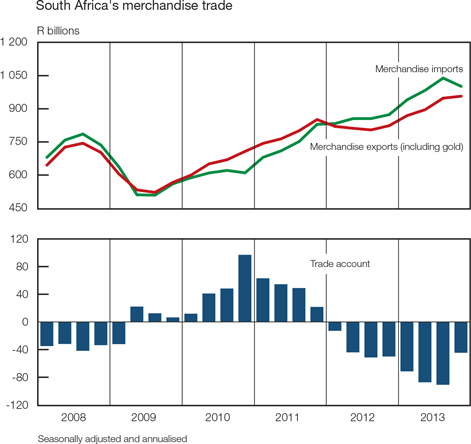

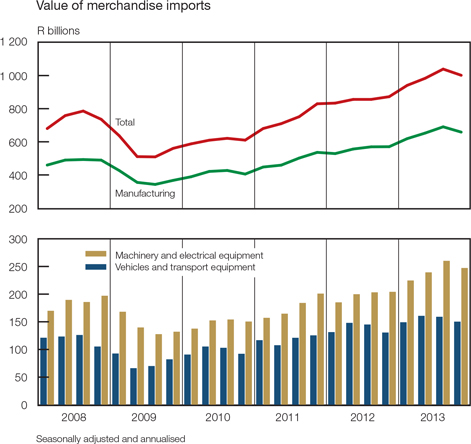

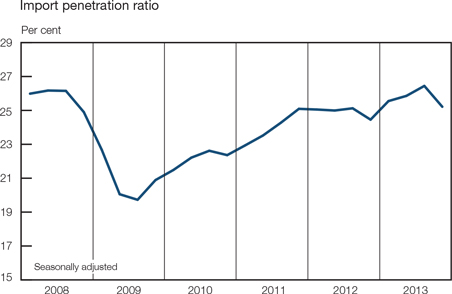

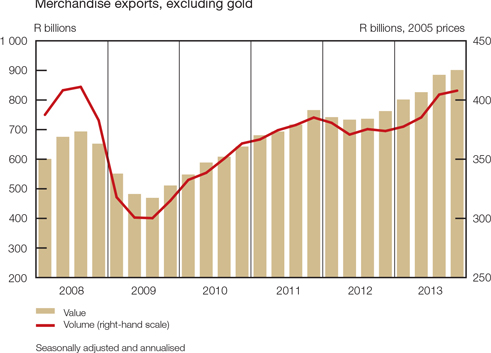

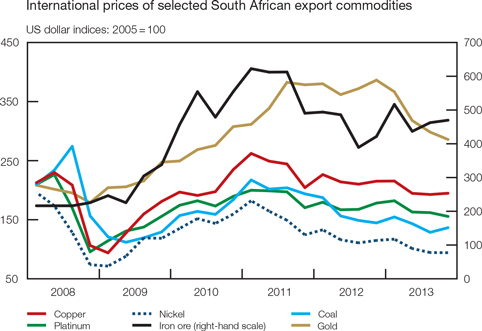

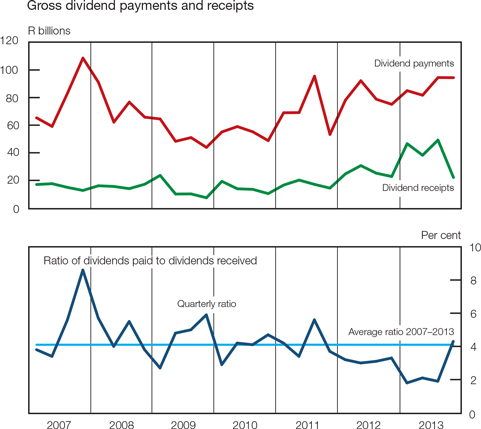

Partly related to the negative inventory investment, merchandise imports contracted significantly in the fourth quarter of 2013, albeit from a high base. Pronounced decreases were recorded in imports of especially machinery and electrical equipment, and vehicles and transport equipment. By contrast, merchandise exports rose in the fourth quarter, partly as a catch-up action following the strike-induced setbacks to production and exports in the previous quarter. At the same time the deficit on the services, income and current transfer account widened somewhat in the fourth quarter of 2013, not least due to lower gross dividend receipts from the rest of the world following exceptionally high receipts in the preceding quarter. These developments culminated in a somewhat narrower deficit on the current account of the balance of payments: the fourth-quarter deficit amounted to 5,1 per cent of gross domestic product, lower than in the third quarter when the shortfall ratio amounted to 6,4 per cent.

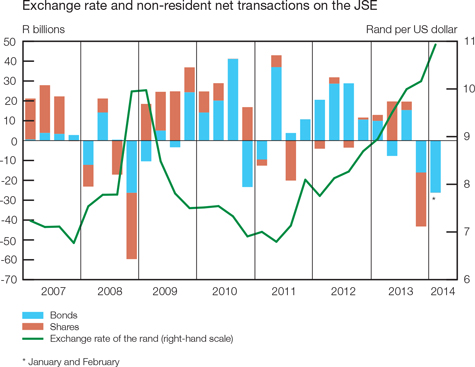

With international investor sentiment towards emerging-market economies having turned negative during the fourth quarter of 2013 in reaction to the imminent tapering of asset purchases by the US Federal Reserve, a sharp reversal of portfolio flows was registered in the final quarter of 2013. The net inward movement of foreign capital through the financial account of the balance of payments moderated considerably in the fourth quarter of the year, with the inflow mainly taking the form of an increase in other investment liabilities. Throughout the fourth quarter the South African Reserve Bank (the Bank) maintained its gross gold and other foreign-exchange reserves at a level of around four-and-a-half months’ worth of imports.

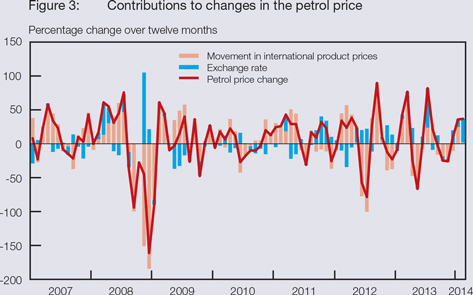

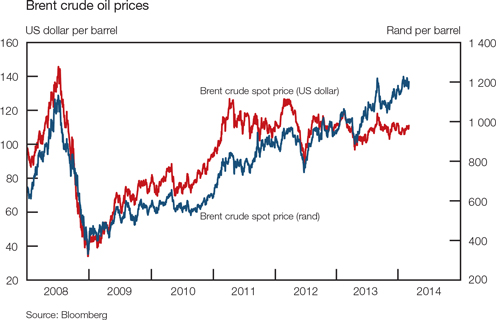

The investor dynamics generated by the tapering announcements in the US, the ongoing labour strife and the sizeable deficit on the current account of the balance of payments contributed to a renewed depreciation in the exchange value of the rand in the final weeks of 2013 and early 2014. Although the pass-through of the depreciation in the exchange rate to inflation remained muted, prices and expectations started to respond; bolstered by higher food and fuel prices, consumer price inflation for instance most recently picked up to a level just below the 6 per cent upper limit of the inflation target range.

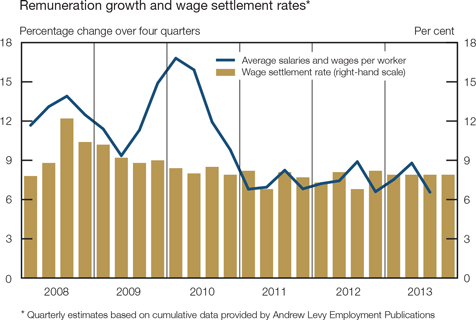

Despite instances of adversarial industrial relations, average wage settlements in 2013 remained at levels just below 8 per cent throughout the year. Employer-surveyed data show modest growth in employment in the formal sector in the year to the third quarter of 2013, with the public sector rather than the private sector responsible for the limited number of jobs that were created. Unemployment remained structurally high at more than 24 per cent of the workforce.

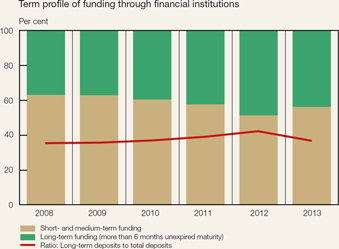

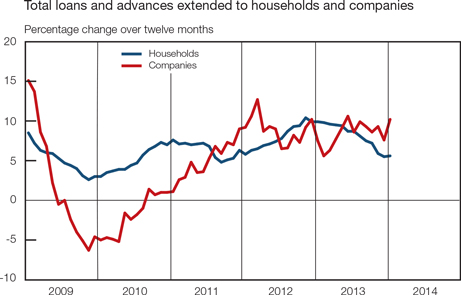

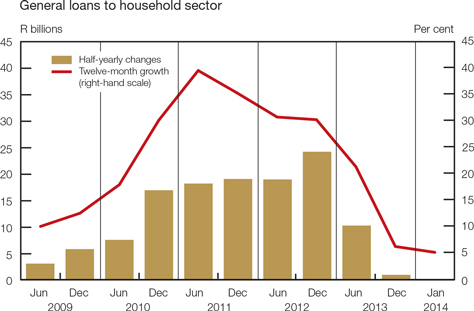

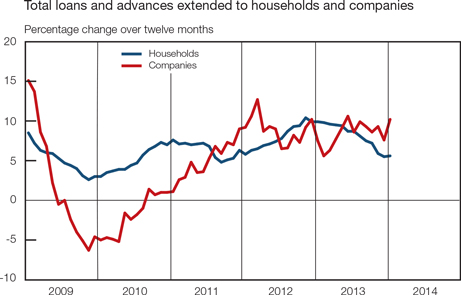

The slow and uneven pace of economic growth and subdued levels of confidence contributed to sluggish growth in banks’ credit extension. Unsecured lending to households lost its earlier vigour in the course of 2013, while the pace of increase in installment sale credit and leasing finance slowed in recent months, consistent with the reduced buoyancy of vehicle sales. Growth in mortgage advances picked up slightly but remained subdued.

| | |

| | Quarterly Bulletin March 2014 |

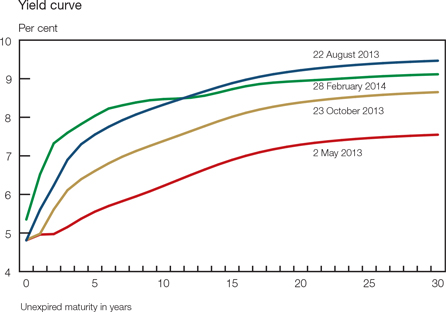

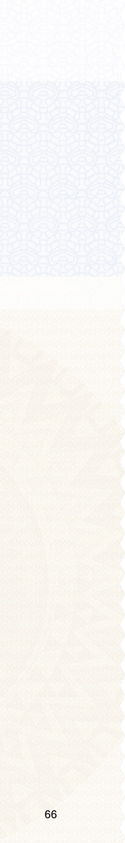

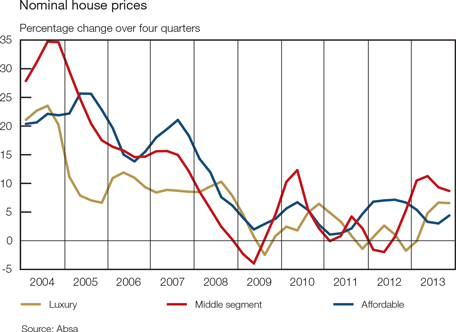

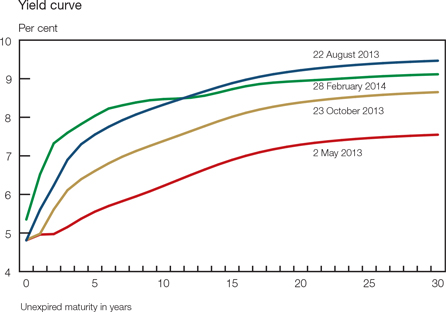

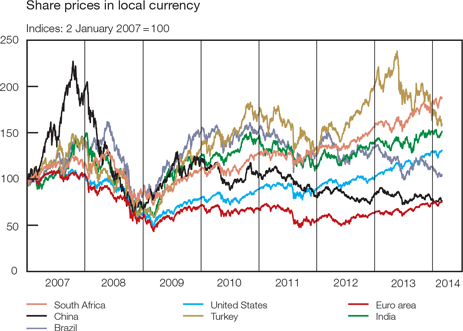

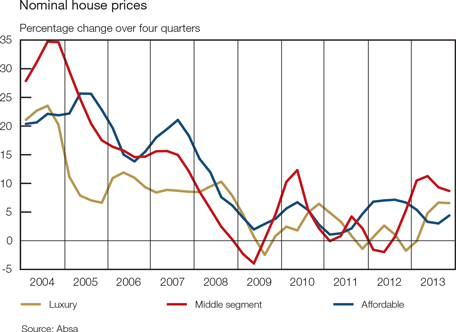

Towards the end of 2013 house price inflation was maintained at year-on-year rates of around 7 per cent, with tentative signs of an improvement in turnover. With yields on deposit-type investments low, South African share prices fluctuated higher in 2013 and early 2014 to successive record levels. Domestic bond yields, which increased significantly in the wake of the first tapering remarks by the US Federal Reserve in May 2013, rose further in the second half of 2013 and first two months of 2014. Owing to the marked depreciation in the exchange value of the rand, the rand value of most portfolios of foreign assets increased sharply in recent months.

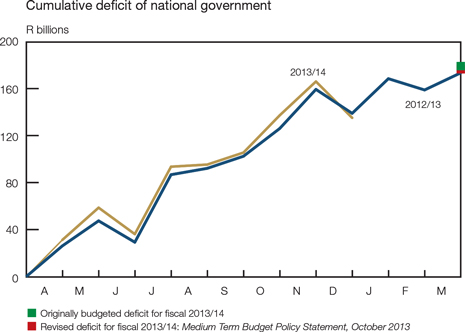

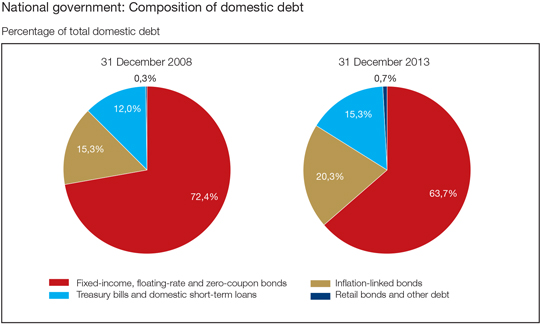

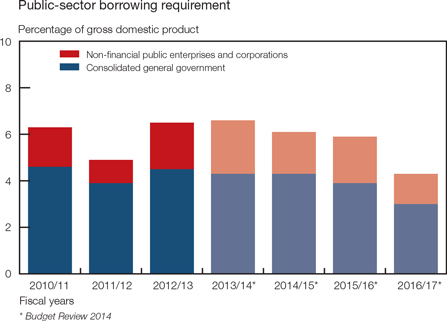

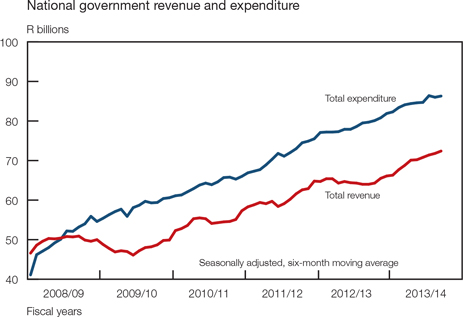

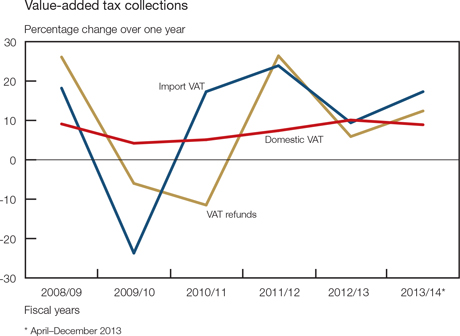

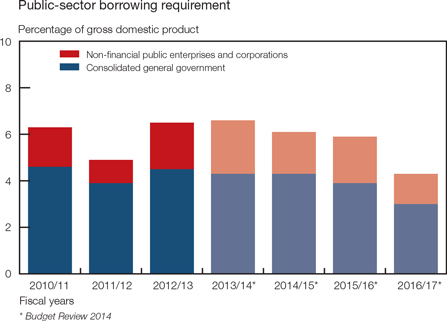

The public-sector borrowing requirement remained marginally above 6 per cent of gross domestic product in the period April to December 2013, supporting the economic recovery as both general government and the non-financial public corporations incurred deficits. Delivered in February 2014, the Budget for fiscal 2014/15 essentially maintained an even keel fiscal policy, providing consistency and stability while simultaneously moving ahead in the implementation of the National Development Plan (NDP). Balancing the key principles of countercyclicality, debt sustainability and intergenerational fairness in an environment of lacklustre growth, the Budget provided for moderate increases in real spending, although within an explicit expenditure ceiling. Compared with the October 2013 Medium Term Budget Policy Statement, a slightly quicker pace of narrowing of the consolidated budget deficit was projected in support of debt stabilisation, while at the same time improving the composition of government expenditure through further emphasis on capital spending and alignment with the NDP.

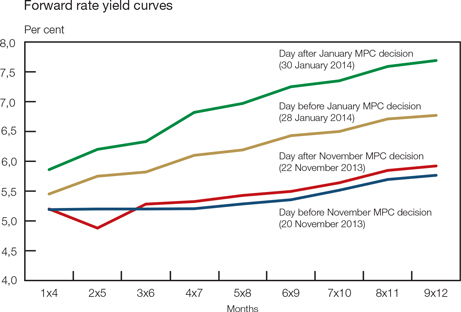

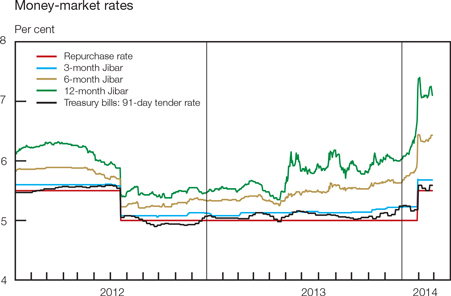

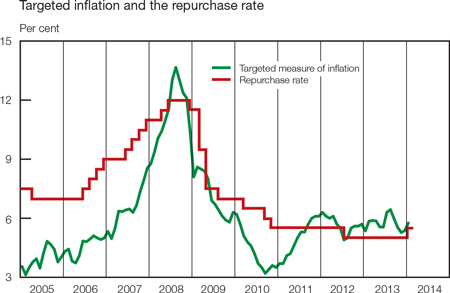

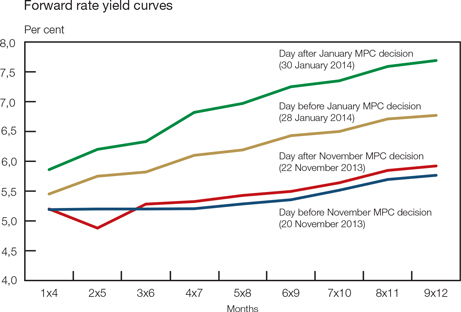

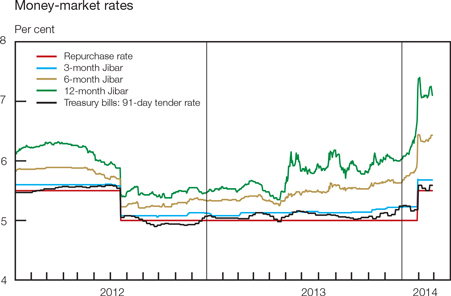

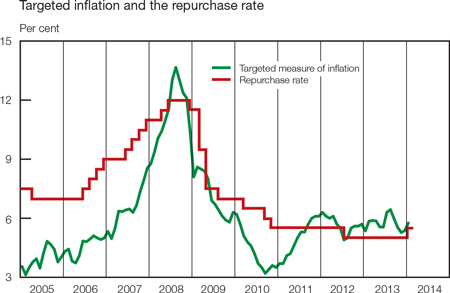

A notable further depreciation in the exchange value of the rand in January 2014 significantly raised the risk of inflation rising above the target range and staying there for a protracted period of time. To address this risk the Monetary Policy Committee (MPC) at its January 2014 meeting decided to increase the repurchase rate from 5,0 per cent to 5,5 per cent per annum – the first change in the repurchase rate since July 2012, when it was lowered by 50 basis points. The 18-month trough in interest rates was therefore slightly longer than in the previous interest rate cycle: the 2005–2006 trough lasted 14 months, with the repurchase rate at the time being maintained at a level of 7 per cent.

| | |

| Quarterly Bulletin March 2014 | |  |

Domestic economic developments

Domestic output1

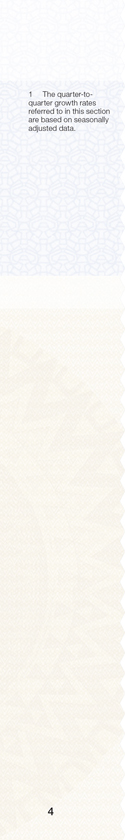

Domestic economic activity expanded notably in the fourth quarter of 2013. Growth in real gross domestic product picked up from an annualised rate of 0,7 per cent in the third quarter of 2013 to 3,8 per cent in the fourth quarter, mainly reflecting a rebound in the real value added by the secondary sector which had severely hampered the country’s growth performance in the preceding quarter. Stronger growth was also recorded in the real value added by the primary and tertiary sectors.

Despite the improved performance in the fourth quarter of 2013, aggregate real gross domestic product for the year 2013 as a whole increased by a disappointing 1,9 per cent, reflecting among other factors the adverse impact of sporadic labour disruptions in several sectors of the economy, subdued business and consumer confidence levels, structural impediments hampering production and ongoing subdued global economic conditions. Growth in real gross domestic product in 2013 was, with the exception of 2009 when gross domestic production contracted, the lowest during the past 15 years. On average, annual growth amounted to 2,8 per cent in the four years, from 2010 to 2013, compared with an average of 3,7 per cent in the preceding ten years.

Real gross domestic product

Percentage change at seasonally adjusted annualised rates

| | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | |

| | | 2012 | | | 2013 | |

| Sector | | Year | | | 1st qr | | | 2nd qr | | | 3rd qr | | | 4th qr | | | Year | |

Primary sector | | | -2,0 | | | | 7,5 | | | | -4,7 | | | | 8,9 | | | | 12,8 | | | | 2,9 | |

Agriculture | | | 2,0 | | | | -4,4 | | | | -3,0 | | | | 3,6 | | | | 6,4 | | | | 2,3 | |

Mining | | | -3,6 | | | | 13,4 | | | | -5,4 | | | | 11,4 | | | | 15,7 | | | | 3,1 | |

Secondary sector | | | 1,8 | | | | -5,9 | | | | 9,6 | | | | -4,5 | | | | 9,2 | | | | 1,0 | |

Manufacturing | | | 2,1 | | | | -7,9 | | | | 11,7 | | | | -6,6 | | | | 12,3 | | | | 0,8 | |

Tertiary sector | | | 3,2 | | | | 2,0 | | | | 2,2 | | | | 1,3 | | | | 1,5 | | | | 2,0 | |

Non-manufacturing sector | | | 2,5 | | | | 2,4 | | | | 1,6 | | | | 2,1 | | | | 2,5 | | | | 2,1 | |

Non-primary sector | | | 2,8 | | | | 0,0 | | | | 4,0 | | | | -0,1 | | | | 3,3 | | | | 1,8 | |

Total | | | 2,5 | | | | 0,8 | | | | 3,2 | | | | 0,7 | | | | 3,8 | | | | 1,9 | |

| | |

| | Quarterly Bulletin March 2014 |

Compared to the erratic growth of the labour-affected and energy-dependent manufacturing sector, the real value added by the other sectors advanced more smoothly from quarter to quarter, as illustrated in the accompanying table. Excluding manufacturing, the economy registered annual growth of 2,1 per cent for the year 2013 as a whole.

The real output of the primary sector increased at a brisk pace of 12,8 per cent in the fourth quarter of 2013 following growth of 8,9 per cent in the third quarter, with both the agricultural and the mining sectors registering a firmer pace of growth in the final quarter of 2013.

The real value added by the agricultural sector increased at an annualised rate of 6,4 per cent in the fourth quarter of 2013 following an increase of 3,6 per cent in the third quarter. The strong performance in the fourth quarter stemmed primarily from an increase in field crop production, more in particular sugar cane, alongside higher animal and horticultural production. According to the final estimates of the Crop Estimates Liaison Committee, the maize crop for the 2012/13 production season amounted to 11,7 million tons compared with 12,1 million tons harvested in the 2011/12 production season.

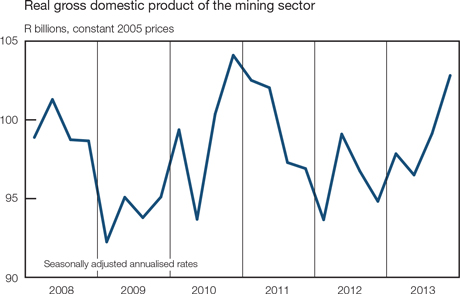

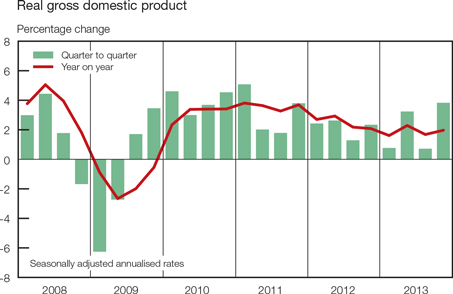

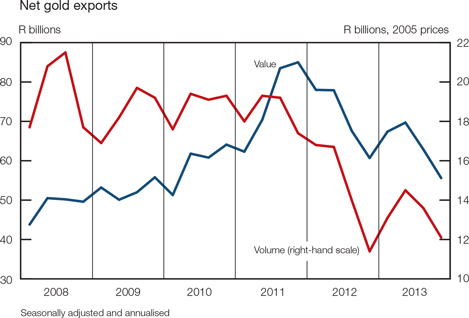

Growth in real value added by the mining sector accelerated from 11,4 per cent in the third quarter of 2013 to 15,7 per cent in the fourth quarter. This firm performance could largely be attributed to pronounced increases in the production of diamonds and other mining commodities, while some growth in the production of platinum group metals also contributed to the positive outcome. Gold production benefited from a higher grade of ore milled and lower operating cost experienced by some gold mines. Platinum production expanded further despite remnants of labour disruptions during the period. By contrast, the production of coal was affected by the scaling down of unprofitable collieries and disruptions due to construction activity to modify certain plants. In addition, the adverse weather conditions experienced in the preceding quarter continued to weigh upon certain open-cast coal operations over the period.

On an annual basis, the real output of the mining sector increased by 3,1 per cent in 2013 after having declined by 3,6 per cent in 2012. The recovery in mining output in 2013 largely reflected higher production volumes in the diamond, platinum and gold mining sectors. Labour strife and the policy environment continued to play a key role in 2013.

Subsequent to an annualised decline of 4,5 per cent in the third quarter of 2013, the real value added by the secondary sector expanded at a firm pace in the fourth quarter, rising by 9,2 per cent. The real output of the manufacturing sector improved from a low base established in the preceding quarter, alongside a firm increase in construction activity. Output of the electricity, gas and water sector, however, contracted over the period.

| | |

| Quarterly Bulletin March 2014 | |  |

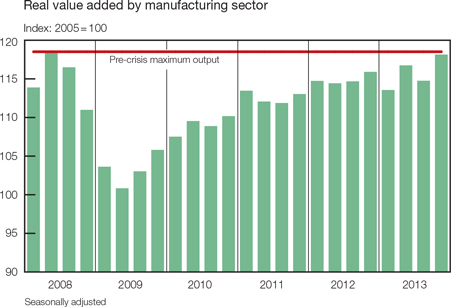

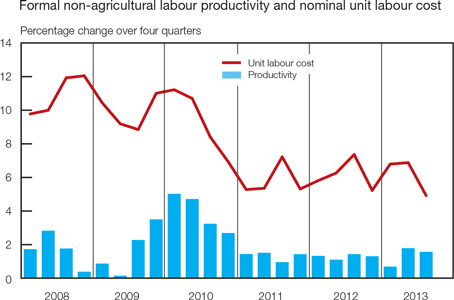

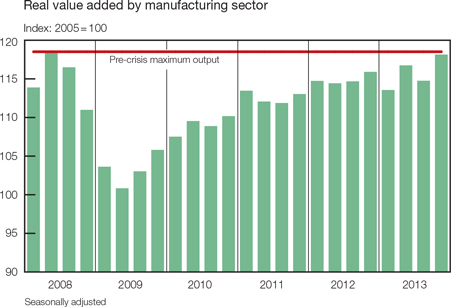

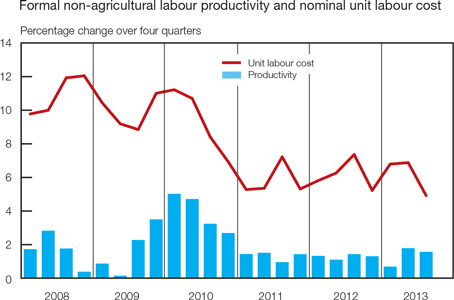

Having been fairly erratic in the first three quarters of 2013, growth in the real value added by the manufacturing sector rebounded in the final quarter of 2013, adding 1,8 percentage points to the overall economic growth rate of 3,8 per cent in the fourth quarter. Real output originating in the manufacturing sector increased at an annualised rate of 12,3 per cent in the final quarter of 2013, following a decline of 6,6 per cent in the third quarter. Notwithstanding the most recent recovery in manufacturing output, real production still fell short of levels recorded prior to the financial crisis. Production more recently benefited from somewhat more stable global economic conditions, stronger growth in advanced and emerging-market economies and enhanced competitiveness brought about by the depreciation in the exchange value of the rand. For the improved performance of the manufacturing sector to be sustained, however, the ongoing increases in nominal unit labour cost and diminishing productivity growth in the sector would need to be addressed.

| | |

| | Quarterly Bulletin March 2014 |

Growth in production in the subsectors manufacturing motor vehicles, parts and accessories; petroleum and chemical products, rubber and plastic products; and radio, television and communication equipment accelerated over the period. Production, however, decreased in the subsectors producing wood and wood products; clothing and footwear; and basic iron and steel, non-ferrous metals and machinery. Consistent with the higher level of manufacturing production, the utilisation of production capacity in the manufacturing sector advanced from 81,2 per cent in the third quarter of 2013 to 82,6 per cent in the fourth quarter. Pronounced increases were registered in the subsectors manufacturing motor vehicles, parts and accessories, and other transport equipment.

For the year as a whole, real growth in manufacturing output, however, tapered off from 2,1 per cent in 2012 to only 0,8 per cent in 2013. The slower momentum in 2013 largely reflected locally driven dynamics such as a setback caused by a fire at a steel mill, maintenance of refineries and industrial action in the motor vehicle and component industries. Global demand for domestically produced manufactured products remained subdued over the period.

Having increased at an annualised rate of 3,8 per cent in the third quarter of 2013, real output of the sector supplying electricity, gas and water contracted by 5,6 per cent in the fourth quarter. The decline could primarily be explained by supply constraints following scheduled maintenance performed on two large generators during the quarter. The tight supply of electricity was furthermore exacerbated by the fact that air-cooled stations could not operate at maximum capacity due to extremely high temperatures experienced over the period. The real value added by the sector contracted by 0,4 per cent in 2013, following a decline of 1,6 per cent in 2012. The most recent decline could be attributed to the warmer winter temperatures experienced during 2013, increased savings by the household sector in response to higher electricity prices and sluggish economic growth over the period.

Real output of the construction sector continued to pick up pace and advanced at an annualised rate of 3,1 per cent in the fourth quarter of 2013 compared with a rate of 2,1 per cent in the third quarter. Civil construction activity in the public sector maintained its underlying upward momentum, driven by government’s infrastructural development plans. Activity in the residential and non-residential building industry, however, improved only marginally over the period. Owing mainly to increased activity in civil construction, the real value added by the construction sector rose by 2,8 per cent in 2013 compared with an increase of 2,3 per cent in 2012.

Growth in the real value added by the tertiary sector accelerated from an annualised rate of 1,3 per cent in the third quarter of 2013 to 1,5 per cent in the fourth quarter. Firmer growth in the commerce and finance, insurance, real-estate and business services sector was partly

| | |

| Quarterly Bulletin March 2014 | |  |

neutralised by the weaker performance of the transport sector. The real value added by general government remained subdued over the period.

Real output of the trade sector increased at an annualised rate of 2,3 per cent in the fourth quarter of 2013, significantly faster than the rate of increase of 1,3 per cent in the third quarter. This solid performance primarily reflected an expansion in retail and wholesale trade, as somewhat less buoyant activity was registered in the motor trade subsector. The pickup in retail and wholesale trade in part followed a low base in the third quarter of 2013 caused by the spate of industrial action which negatively affected some sectors between August and October. Conversely, the more modest performance of the motor trade subsector reflected strike action and the somewhat weaker domestic demand for durable and semi-durable goods in the final quarter of 2013. Demand for tourism accommodation increased in the fourth quarter of 2013, inter alia, due to a surge in the number of foreign travellers. For the year as a whole, the growth in real value added by commerce moderated from a rate of 3,8 per cent in 2012 to 2,2 per cent in 2013 as the real value added by all subsectors slowed over the period.

Growth in the real value added by the transport, storage and communication sector edged lower from an annualised rate of 2,6 per cent in the third quarter of 2013 to 1,6 per cent in the fourth quarter, reflecting sluggish activity in the transport subsector. Activity in both freight and passenger transportation slowed over the period whereas activity in the telecommunication subsector picked up further. Overall, growth in the real value added by the transport, storage and communication sector slowed from 2,4 per cent in 2012 to 1,9 per cent in 2013.

Consistent with the acceleration in overall growth, the real value added by the finance, insurance, real-estate and business services sector picked up from an annualised rate of increase of 1,2 per cent in the third quarter of 2013 to 1,5 per cent in the fourth quarter. The increased growth reflected higher activity in the banking sector and in the equity, bond and financial markets. The growth in real value added by the finance, insurance, real-estate and business services sector moderated from 3,7 per cent in 2012 to 2,4 per cent in 2013.

Growth in real output of general government increased at an annualised rate of 0,9 per cent in the fourth quarter of 2013. On a calendar basis, the real value added by general government slowed to 1,5 per cent in 2013, compared with an increase of 2,8 per cent in 2012.

Real gross domestic expenditure

Aggregate real gross domestic expenditure declined further from an annualised rate of 0,8 per cent in the third quarter of 2013 to 3,6 per cent in the fourth quarter. In real terms, faster growth in final consumption expenditure by general government was more than neutralised by a slower pace of increase in household consumption expenditure and gross fixed capital formation; inventory holdings declined over the period. For the year 2013 as a whole, however, real gross domestic expenditure increased by 2,2 per cent, thereby exceeding growth in real gross domestic production.

Real gross domestic expenditure

Percentage change at seasonally adjusted annualised rates

| | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | |

| | | 2012 | | | 2013 | |

| Component | | Year | | | 1st qr | | | 2nd qr | | | 3rd qr | | | 4th qr | | | Year | |

Final consumption expenditure | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | |

Households | | | 3,5 | | | | 2,4 | | | | 2,5 | | | | 2,1 | | | | 2,0 | | | | 2,6 | |

General government | | | 4,0 | | | | 2,8 | | | | 1,7 | | | | 1,5 | | | | 2,0 | | | | 2,4 | |

Gross fixed capital formation | | | 4,4 | | | | 3,8 | | | | 5,6 | | | | 7,0 | | | | 3,1 | | | | 4,7 | |

Domestic final demand | | | 3,8 | | | | 2,7 | | | | 2,9 | | | | 2,9 | | | | 2,2 | | | | 2,9 | |

Change in inventories (R billions)* | | | 9,9 | | | | 7,9 | | | | 16,4 | | | | 3,3 | | | | -22,3 | | | | 1,3 | |

Gross domestic expenditure | | | 4,0 | | | | 5,3 | | | | 3,2 | | | | -0,8 | | | | -3,6 | | | | 2,2 | |

| | |

| | Quarterly Bulletin March 2014 |

Real net exports made the largest contribution to growth in real gross domestic product in the fourth quarter of 2013, adding 7,8 percentage points, followed by real final consumption expenditure by households. For the year 2013 as a whole, real private consumption expenditure by households, however, continued to make the largest contribution to real gross domestic product.

Contribution of expenditure components to growth in real gross domestic product

Percentage points

| | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | |

| | | 2012 | | | 2013 | |

| Component | | Year | | | 1st qr | | | 2nd qr | | | 3rd qr | | | 4th qr | | | Year | |

Final consumption expenditure | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | |

Households | | | 2,3 | | | | 1,6 | | | | 1,6 | | | | 1,4 | | | | 1,3 | | | | 1,7 | |

General government | | | 0,8 | | | | 0,6 | | | | 0,4 | | | | 0,3 | | | | 0,4 | | | | 0,5 | |

Gross fixed capital formation | | | 0,9 | | | | 0,7 | | | | 1,1 | | | | 1,4 | | | | 0,6 | | | | 0,9 | |

Change in inventories | | | 0,1 | | | | 2,4 | | | | 1,7 | | | | -2,6 | | | | -5,2 | | | | -0,4 | |

Net exports | | | -1,7 | | | | -4,8 | | | | -0,2 | | | | 1,6 | | | | 7,8 | | | | -0,5 | |

Residual | | | 0,1 | | | | 0,2 | | | | -1,4 | | | | -1,4 | | | | -1,2 | | | | -0,3 | |

Gross domestic product | | | 2,5 | | | | 0,8 | | | | 3,2 | | | | 0,7 | | | | 3,8 | | | | 1,9 | |

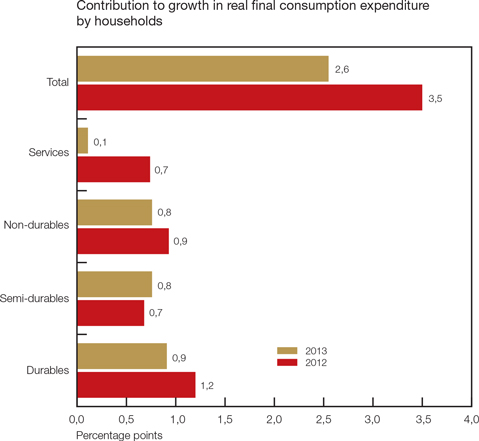

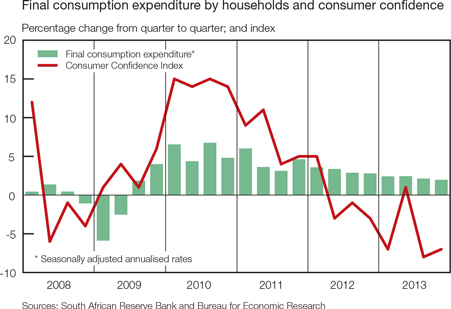

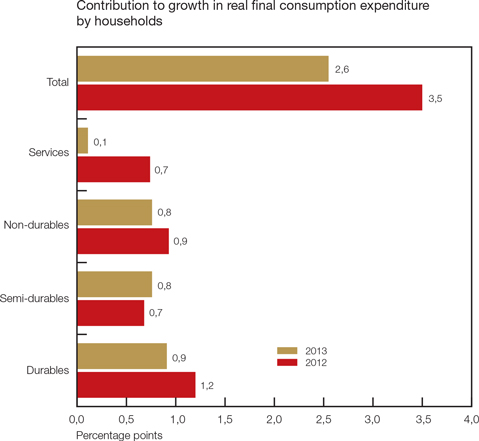

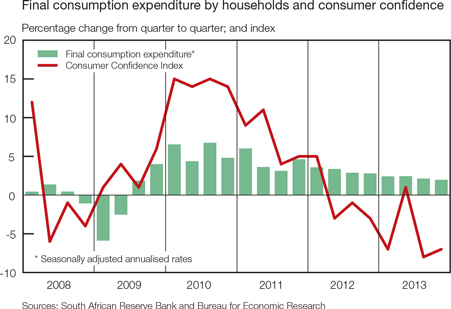

Real final consumption expenditure by households increased at a slightly slower pace in the fourth quarter of 2013 due to, among other factors, rising inflation and tighter lending conditions. Having increased at an annualised rate of 2,1 per cent in the third quarter of 2013, real spending by households advanced at a marginally slower pace of 2,0 per cent in the fourth quarter. Growth in outlays on durable and semi-durable goods lost some momentum, whereas real expenditure on non-durable goods remained sluggish. Expenditure on services, however, increased at a faster pace over the period.

Real final consumption expenditure by households

Percentage change at seasonally adjusted annualised rates

| | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | |

| | | 2012 | | | 2013 | |

| Category | | Year | | | 1st qr | | | 2nd qr | | | 3rd qr | | | 4th qr | | | Year | |

Durable goods | | | 11,1 | | | | 5,9 | | | | 12,6 | | | | 9,4 | | | | 6,9 | | | | 7,9 | |

Semi-durable goods | | | 6,2 | | | | 7,6 | | | | 8,5 | | | | 7,1 | | | | 3,1 | | | | 6,7 | |

Non-durable goods | | | 2,7 | | | | 2,4 | | | | 2,7 | | | | 0,5 | | | | 0,2 | | | | 2,2 | |

Services | | | 1,7 | | | | 0,1 | | | | -2,1 | | | | 0,1 | | | | 1,7 | | | | 0,3 | |

Total | | | 3,5 | | | | 2,4 | | | | 2,5 | | | | 2,1 | | | | 2,0 | | | | 2,6 | |

Having increased by 3,5 per cent in 2012, growth in real consumption expenditure by households moderated to 2,6 per cent in 2013, still accounting for roughly 61 per cent of total expenditure on gross domestic product.

In the fourth quarter of 2013 household spending on durable goods expanded at a slower pace than in the preceding two quarters, moderating from 9,4 per cent in the third quarter to a still fairly brisk 6,9 per cent in the final quarter. Lower spending on furniture and appliances, along with slower growth in spending on personal transport equipment and on computers and related equipment – components which typically have a high import content – was partly offset by increased spending on durable recreational and entertainment goods and on other durable goods. The weaker demand for furniture and household appliances could probably in part be ascribed to a moderation in credit extension by some retailers. Consistent with slower growth in real disposable income of households and lower consumer confidence levels, the pace of increase in real spending on durable goods moderated from 11,1 per cent in 2012 to 7,9 per cent in 2013.

| | |

| Quarterly Bulletin March 2014 | |  |

After growing at a steady pace of more than 7 per cent in the first three quarters of 2013, growth in real spending on semi-durable goods decelerated to 3,1 per cent in the final quarter of 2013. The slower growth was evident in most categories of semi-durable goods, with the exception of recreational and miscellaneous goods.

| | |

| | Quarterly Bulletin March 2014 |

Owing to the largely non-discretionary nature of expenditure on non-durable goods, the level of real spending on this category remained broadly unchanged in the third and fourth quarters of 2013. Lower spending on petroleum products, probably related to the high real price of these products, was offset by increased expenditure on food, beverages and tobacco over the period.

Real spending on services, constituting the largest part of total consumption expenditure by households, increased at an annualised rate of 1,7 per cent in the fourth quarter of 2013, up from 0,1 per cent in the preceding quarter. Growth in spending on rent and household services more than neutralised slower spending on transport and communication services. For the calendar year 2013 as a whole, real spending by households on services rose by 0,3 per cent, that is, at a much slower pace than the increases of 3,6 per cent and 1,7 per cent recorded in 2011 and 2012 respectively.

Growth in real disposable income of households slowed marginally from an annualised rate of 2,1 per cent in the third quarter of 2013 to 2 per cent in the fourth quarter. On a year-on-year basis, growth in real disposable income of households, however, moderated more noticeably from 3,9 per cent in 2012 to 2,5 per cent in 2013. Household income continued to be negatively affected by rising inflation, the adverse effect of widespread labour unrest and (indirectly) the deterioration in the country’s terms of trade.

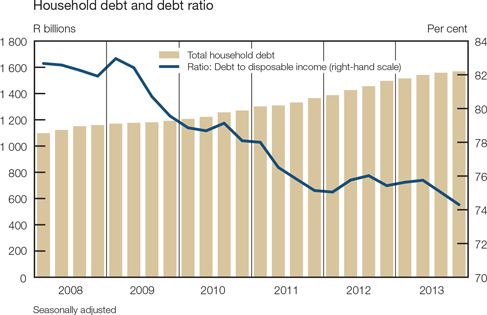

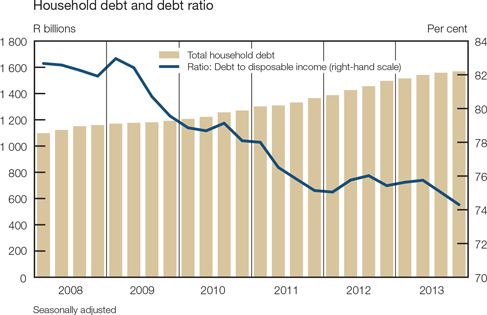

Alongside the slightly slower pace of increase in household consumption expenditure, growth in credit extended to the household sector moderated in the fourth quarter of 2013. The quarterly ratio of household debt to annualised disposable income remained below 76 per cent throughout the year, and as growth in disposable income outpaced growth in household debt, the ratio of household debt to disposable income decreased from 75 per cent in the third quarter of 2013 to 74,3 per cent in the fourth quarter.

On an annual basis, growth in household debt slowed from 8,6 per cent in 2012 to 7,3 per cent in 2013. Simultaneously, the ratio of household debt to disposable income decreased marginally from 75,6 per cent in 2012 to 75,2 per cent in 2013, due to a more pronounced slowdown in debt relative to household income. The debt-service cost ratio, however, remained at 7,7 per cent in both 2012 and 2013, due to stronger growth in credit facilities in high interest-rate advances which offset slower growth in lower interest rate credit facilities over the period.

| | |

| Quarterly Bulletin March 2014 | |  |

Having increased at a rather subdued annualised rate of 1,5 per cent in the third quarter of 2013, the pace of increase in real final consumption expenditure by general government edged higher to 2 per cent in the fourth quarter. The stronger growth could partly be attributed to increased outlays on non-wage goods and services which included, among other expenses, spending associated with the state funeral of the former president of South Africa, Mr Nelson Mandela. Growth in real compensation of employees edged higher in the final quarter of 2013.

Real final consumption expenditure by general government rose by 2,4 per cent in 2013 –slower than the increase of 4 per cent in 2012 when spending on armaments bolstered these outlays. The moderation in 2013 could also in part be attributed to slower growth in spending on compensation of employees. Relative to the country’s gross domestic product, consumption expenditure by general government remained elevated at roughly 22 per cent in both 2012 and 2013.

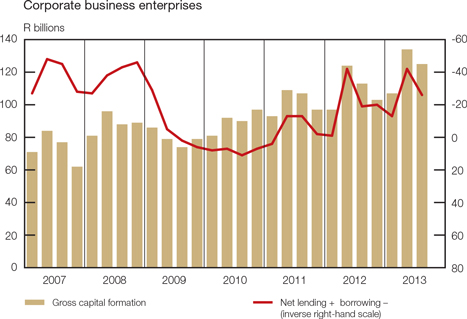

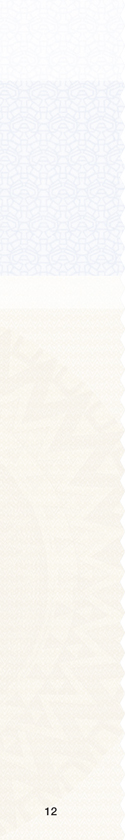

Growth in real gross fixed capital formation moderated in the fourth quarter of 2013, having maintained a steady pace throughout the year. Whereas private business enterprises recorded a significant deceleration, capital spending by the other institutional sectors increased at a slightly faster pace. Capital expenditure by general government advanced at a brisk pace of 9,2 per cent, roughly similar to the rate of increase recorded in the preceding quarter. As a ratio of gross domestic product, however, fixed capital formation tapered off from 19,6 per cent in the third quarter of 2013 to 19,4 per cent in the fourth quarter. The annual growth rate in real fixed capital spending improved further to 4,7 per cent in 2013 following an increase of 4,4 per cent in 2012.

Real gross fixed capital formation by private business enterprises slowed in the final quarter of 2013 as real outlays in the manufacturing sector continued at a more moderate pace. The momentum in capital spending reflected investors’ appetite to increase capacity and to spend on major additions and maintenance. The gradually rising real capital expenditure throughout the year brought the annual growth rate for 2013 to 5,5 per cent, higher than in 2012.

The mining sector continued to spend on ongoing projects, with the majority of the capital outlays directed at machinery and equipment, and construction works. The spending on capital assets was spread across the coal, gold and iron-ore subsectors of mining. Even though production activity at platinum mines was weighed down by industrial action, capital spending continued apace.

| | |

| | Quarterly Bulletin March 2014 |

Real gross fixed capital formation

Percentage change at seasonally adjusted annualised rates

| | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | |

| | | 2012 | | | 2013 | |

| Sector | | Year | | | 1st qr | | | 2nd qr | | | 3rd qr | | | 4th qr | | | Year | |

Private business enterprises | | | 3,9 | | | | 6,2 | | | | 8,2 | | | | 8,6 | | | | 2,4 | | | | 5,5 | |

Public corporations | | | 4,9 | | | | -1,6 | | | | 0,1 | | | | 0,4 | | | | 0,8 | | | | 3,1 | |

General government | | | 6,2 | | | | 1,5 | | | | 2,6 | | | | 9,0 | | | | 9,2 | | | | 3,5 | |

Total | | | 4,4 | | | | 3,8 | | | | 5,6 | | | | 7,0 | | | | 3,1 | | | | 4,7 | |

The moderation in capital investment by the manufacturing sector in the fourth quarter of 2013 was mainly visible in spending on machinery and equipment. Capital spending was spread across a spectrum of manufactured goods industries, including food and beverages, chemicals, and motor parts and accessories.

Real capital formation by the electricity sector rose in the fourth quarter of 2013, partially underpinned by a sharp increase in the capital spending on wind farms and solar plants as part of the Renewable Energy Independent Power Producer Procurement Programme. This was in particular pronounced in the Northern and Eastern Cape. Some of these projects were completed in the final quarter of 2013.

Growth in real fixed capital expenditure by public corporations improved marginally to an annualised rate of 0,8 per cent in the fourth quarter of 2013, mainly due to ongoing spending by the electricity and transport sectors. Most of the leading entities, including Transnet, SANRAL and the Trans-Caledon Tunnel Authority, raised their capital spending. Despite the ongoing activity, real capital expenditure by public corporations increased at a rate of only 3,1 per cent in 2013, substantially lower than the rate of increase of 4,9 per cent recorded in 2012.

Real gross fixed capital formation by general government was maintained in the fourth quarter of 2013, with the provincial governments and local authorities in particular stepping up their expenditure. The impetus in capital spending continued to be upheld by outlays on education, health, transport and energy. In addition, the construction and upgrading of provincial roads, schools and provincial hospitals gained momentum. Despite brisk capital outlays in the second half of 2013, growth in 2013 as a whole slowed to 3,5 per cent compared with 6,2 per cent recorded in 2012.

Real inventory accumulation reversed from R3,2 billion in the third quarter of 2013 to destocking at a rate of R22,3 billion (at 2005 prices) in the fourth quarter, subtracting 4,7 percentage points from the growth in real gross domestic expenditure. The de-accumulation of inventories in the manufacturing and mining sectors in the final quarter of 2013 reflected fairly subdued business confidence levels, a stronger than expected increase in economic activity and a fairly sharp decline in imports over the period. On an annual basis, the level of real inventories came to R1,3 billion in 2013, less than the R9,9 billion recorded in 2012.

The decline in inventories in the mining sector largely reflected lower inventory holdings as industrial action adversely affected production in the fourth quarter of 2013. In the manufacturing sector, the de-accumulation of inventories was associated with lower imports of manufactured goods over the period. Industrial and commercial inventories as a percentage of the non-agricultural gross domestic product declined from 13,2 per cent in the third quarter of 2013 to 12,8 per cent registered in the fourth quarter.

Factor income

Growth over four quarters in aggregate nominal factor income edged lower from a revised rate of 7,5 per cent in the third quarter of 2013 to 7,1 per cent in the fourth quarter. This slower pace of increase reflected more moderate growth in both gross operating surpluses of business enterprises and compensation of employees. However, for the year 2013 as a whole, the rate of increase in total factor income amounted to 7,2 per cent compared with a rate of increase of 7,1 per cent registered in 2012.

| | |

| Quarterly Bulletin March 2014 | |  |

Measured over a year, growth in total compensation of employees decelerated from 8,7 per cent in the third quarter of 2013 to 8,5 per cent in the fourth quarter. This moderation in growth was mainly evident in salaries paid by the general government, and by the manufacturing sector where the payment of wages was affected by illegal strike action in several subsectors. Consequently, the ratio of total compensation of employees to total factor income decreased from 53,4 per cent in the third quarter of 2013 to 53,3 per cent in the fourth quarter. For the year 2013 as a whole, growth in compensation of employees amounted to 8,6 per cent, compared with a rate of 8,8 per cent recorded in 2012. By contrast, the average wage settlement rate as compiled by Andrew Levy Employment Publications increased from 7,6 per cent in 2012 to 7,9 per cent in 2013.

Year-on-year growth in the total gross operating surplus decelerated from 6,3 per cent in the third quarter of 2013 to 5,5 per cent in the fourth quarter as the agricultural and finance sectors performed weaker over the period. Growth in the aggregate gross operating surplus nevertheless accelerated from 5,4 per cent in 2012 to 5,7 per cent in 2013, while the share of the gross operating surplus in total factor income edged lower from 47,8 per cent to 47,1 per cent over the same period.

Gross saving

Gross saving as a percentage of gross domestic product (i.e., the national saving ratio) declined from 13,3 per cent in the third quarter of 2013 to 13,2 per cent in the fourth quarter. This could mainly be attributed to a deterioration in the saving performance of the household sector and the general government as the saving ratio by corporates remained stable. The foreign financing ratio, measuring South Africa’s dependency on foreign capital to finance gross capital formation, decreased marginally from 32,3 per cent in the third quarter of 2013 to 28 per cent in the fourth quarter.

Gross saving by the corporate sector relative to gross domestic product remained unchanged at 13,7 per cent in the third and fourth quarters of 2013. Measured over a year, dividend payments declined by 1,8��per cent in the fourth quarter of 2013 while corporate tax payments advanced at a brisk pace of 14,8 per cent.

The corporate saving ratio receded from 14,7 per cent in 2012 to 14,1 per cent in 2013 as tougher trading conditions gave rise to slower growth in operating surpluses and lower receipts from property income, while dividend and tax payments increased modestly over the period.

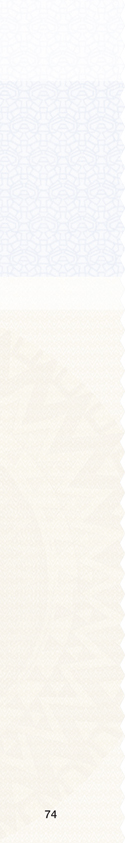

Gross dissaving by general government rose from 2,1 per cent of gross domestic product in the third quarter of 2013 to 2,2 per cent in the fourth quarter. Government income moderated on account of lower growth in value added tax alongside an increase in total government expenditure reflecting, inter alia, higher transfers to households and increased interest payments on public debt over the period. The rate of dissaving by general government nevertheless remained at 2,2 per cent in 2012 and 2013.

The gross saving rate of the household sector weakened from 1,7 per cent in the third quarter of 2013 to 1,6 per cent in the fourth quarter, as both household final consumption expenditure and disposable income of households increased at a slower pace over the period.

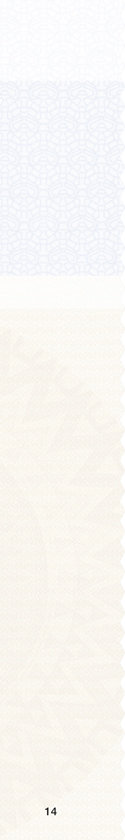

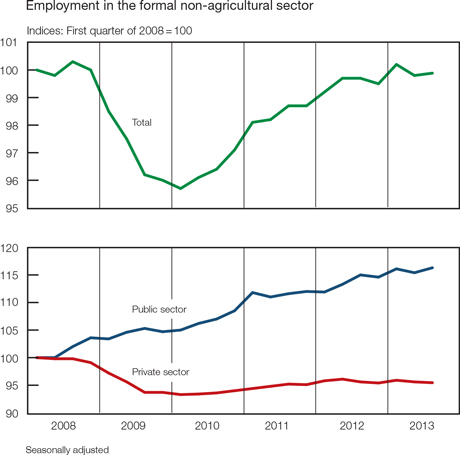

Employment

Consistent with the weakening in the growth momentum of the economy, the pace of increase in formal non-agricultural employment has stalled since the third quarter of 2012. This followed a period of ten quarters in which employment losses related to the recessionary conditions after the global financial crisis in 2008 were steadily recovered. Having increased slightly in the third quarter of 2013, the level of formal non-agricultural employment approximated that which existed immediately prior to the global financial crisis at around 8,45 million, according to Stats SA’s Quarterly Employment Statistics (QES) survey. Disappointingly, private-sector employment has not yet recovered to that level, having essentially remained stationary since the second quarter of 2012, unlike public-sector employment which increased apace in a contra-cyclical fashion.

| | |

| | Quarterly Bulletin March 2014 |

In fact, the public sector increased its staff complement by an annualised 3,1 per cent in the third quarter of 2013, reclaiming all the jobs lost in the preceding quarter. Employment increased at all public-sector tiers in the third quarter, with the largest increases registered by local governments and public-sector enterprises.

Conversely, private-sector employment decreased further at an annualised rate of 0,7 per cent in the third quarter of 2013. Similar to the previous quarter, job losses were again fairly pervasive throughout the private sector, occurring in the gold-mining sector (recording the highest rate of contraction at 22,2 per cent); the construction sector; the electricity sector; the finance, insurance, real-estate and business services sector; the manufacturing sector; the non-gold mining sector; and the private transport, storage and communication services sector. In the private sector employment creation took place in the community, social and personal services sector and in the trade, catering and accommodation services sector.

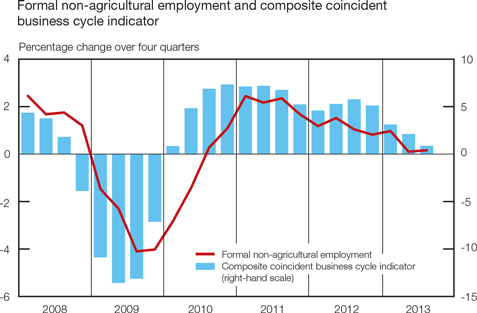

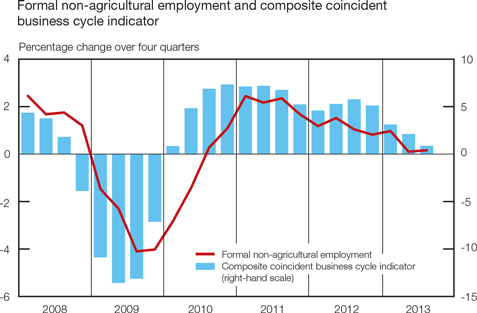

Entering its 52nd month in December 2013, the current upward phase in the South African business cycle appears to have lost some momentum. The accompanying graph shows the correlation between the year-on-year rate of change in the composite coincident business cycle indicator and that in formal non-agricultural employment. Following a sustained period of slowing output growth, exacerbated by numerous incidents of disruptive industrial action, formal non-agricultural employment growth has gradually lost momentum over the past two years. Over and above disappointing output and employment growth, the domestic industrial relations environment has dampened business and investor confidence in the South African economy. During the current upward phase in the business cycle, the RMB/BER Business Confidence Index breached the neutral level of 50 in only three of the seventeen quarters up to the fourth quarter of 2013 – an exceptionally low number for such a lengthy business-cycle expansion.

| | |

| Quarterly Bulletin March 2014 | |  |

Change in enterprise-surveyed formal non-agricultural employment by sector*

| | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | |

| | | Change over

one quarter at

annualised rate

3rd qr 2013 | | | Change over four

quarters to

3rd qr 2013 | | | Cumulative job

losses (-) gains (+) | |

| Sector | | Number | | | Per

cent | | | Number | | | Per

cent | | | 4th qr

2008 to

1st qr 2010 | | | 2nd qr

2010 to

3rd qr 2013 | |

Finance, insurance, real-estate and business services | | | -6 500 | | | | -1,4 | | | | 10 600 | | | | 0,6 | | | | -163 400 | | | | 86 400 | |

Manufacturing | | | -2 500 | | | | -0,9 | | | | -5 000 | | | | -0,4 | | | | -118 300 | | | | -37 500 | |

Trade, catering and accommodation services | | | 7 300 | | | | 1,7 | | | | 7 300 | | | | 0,4 | | | | -75 700 | | | | 62 000 | |

Construction | | | -3 600 | | | | -3,3 | | | | -7 700 | | | | -1,8 | | | | -52 100 | | | | 7 200 | |

Total mining | | | -9 100 | | | | -6,9 | | | | -13 400 | | | | -2,6 | | | | -35 900 | | | | 8 600 | |

Gold mining | | | -8 200 | | | | -22,2 | | | | -15 400 | | | | 10,8 | | | | -8 900 | | | | -33 600 | |

Other mining | | | -900 | | | | -0,9 | | | | 2 000 | | | | 0,5 | | | | -27 000 | | | | 42 300 | |

Electricity | | | -200 | | | | -1,6 | | | | -600 | | | | -1,0 | | | | -3 300 | | | | 6 200 | |

Private transport, storage and communication services | | | -600 | | | | -0,9 | | | | -2 400 | | | | -0,9 | | | | -2 000 | | | | 700 | |

Community, social and personal services | | | 4 500 | | | | 4,3 | | | | 1 500 | | | | 0,3 | | | | 13 400 | | | | 12 700 | |

Private sector | | | -10 700 | | | | -0,7 | | | | -9 700 | | | | -0,2 | | | | -437 300 | | | | 146 300 | |

Provinces | | | 5 500 | | | | 2,0 | | | | 1 500 | | | | 0,1 | | | | 51 600 | | | | 91 900 | |

Local governments | | | 5 000 | | | | 7,5 | | | | 17 000 | | | | 6,5 | | | | 15 000 | | | | 37 800 | |

National departments | | | 900 | | | | 0,8 | | | | -5 700 | | | | -1,2 | | | | -800 | | | | 42 100 | |

Public transport, storage and communication services | | | 600 | | | | 2,1 | | | | 5 800 | | | | 5,1 | | | | -4 900 | | | | 15 800 | |

Other public-sector enterprises | | | 3 800 | | | | 11,1 | | | | 4 500 | | | | 3,2 | | | | -7 800 | | | | 16 600 | |

Total public sector | | | 15 800 | | | | 3,1 | | | | 23 000 | | | | 1,1 | | | | 53 100 | | | | 204 200 | |

Grand total | | | 5 100 | | | | 0,2 | | | | 13 300 | | | | 0,2 | | | | -384 200 | | | | 350 500 | |

| * | Seasonally adjusted. Components may not add up due to rounding |

| | |

| | Quarterly Bulletin March 2014 |

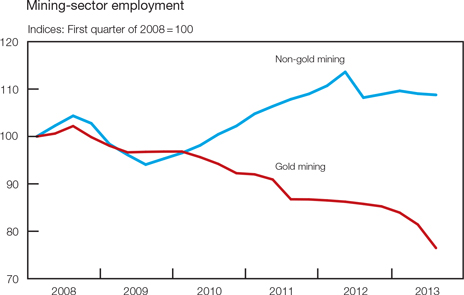

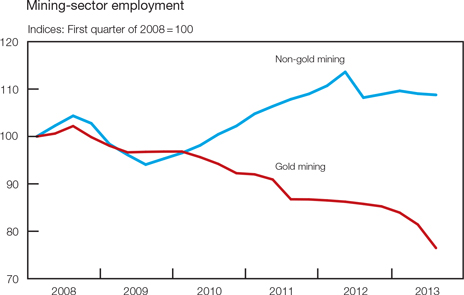

Employment in the mining sector decreased notably further in the third quarter of 2013, as job shedding in especially the gold-mining sector accelerated markedly. In addition, non-gold mining employment decreased for a second successive quarter in the third quarter of 2013. The industrial relations environment in the South African mining industry has changed dramatically since the Marikana tragedy in August 2012, subjecting the industry to high wage demands and intermittent bouts of disruptive industrial action in various subsectors. These labour tensions, coupled with relatively low global commodity prices, fairly sluggish demand for commodities and high domestic operating costs, adversely affected employment creation in the mining sector. In the five quarters up to the third quarter of 2013 the mining sector shed a cumulative 32 800 employment opportunities, lowering the total number of people formally employed in the mining sector to roughly 502 000. Employment prospects in the mining sector remain bleak, particularly considering the most recent widespread labour strike in the platinum-mining sector, which commenced late in January 2014.

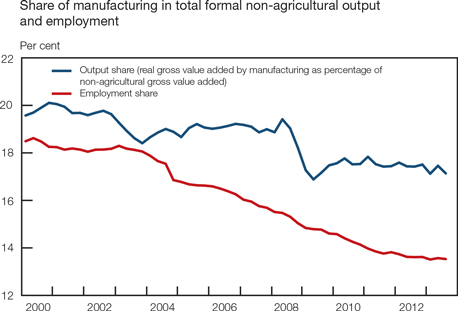

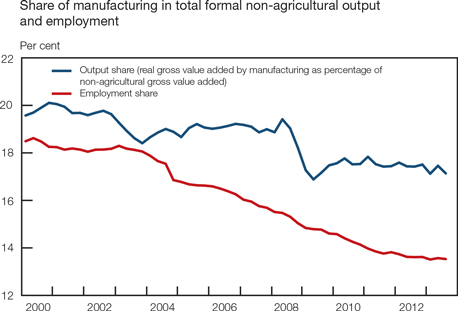

Following a marginal increase in employment in the second quarter of 2013, the manufacturing sector shed a further 2 500 jobs in the third quarter. In addition, the domestic automotive industry was subjected to lengthy and disruptive industrial action in the third and fourth quarters of 2013. The accompanying graph indicates the manufacturing sector’s share in the total formal non-agricultural economy in terms of employment and gross domestic product. Although the manufacturing sector’s share has declined in terms of both variables, the decline in the sector’s employment share has been more pronounced than that in output – probably reflecting the ongoing trend of labour-substituting mechanisation in the domestic manufacturing sector. Accordingly, the Manufacturing Survey of the Bureau for Economic Research (BER) for the fourth quarter of 2013 noted that while employment indicators remained fairly weak, the fixed investment indicator had risen to its highest level since the first quarter of 2012 despite indications that a large majority of manufacturers were not utilising their production capacity to the full. According to the BER, considering the lacklustre employment prospects in the manufacturing sector, this planned new investment is probably aimed at replacing existing capacity, evident in the net majority of respondents expecting an increase in real investment in machinery and equipment in 12 months’ time increasing notably from the third quarter to the fourth quarter of 2013. In general, the BER survey results for the fourth quarter of 2013 were fairly positive, with exporters in particular indicating improved sales volumes on account of a pick-up in global demand for manufactured goods and improved competitiveness associated with the depreciation in the exchange value of the rand.

| | |

| Quarterly Bulletin March 2014 | |  |

Employment levels in the electricity-generating sector decreased in the third quarter of 2013, following notable employment gains in the second quarter. Despite the partial integration of independent power producers into the national electricity grid, South Africa’s electricity supply seems likely to remain fairly constrained until the end of 2014, when the first unit of the new Medupi power station is expected to become operational. Whereas electricity-supply constraints could continue to hamper output and employment growth in the electricity-intensive sectors of the domestic economy, the ongoing programme to expand electricity-generating capacity bodes well for employment creation in the electricity sector.

Employment in the finance, insurance, real-estate and business services sector decreased for a second successive quarter in the third quarter of 2013, with the pace of labour paring accelerating to an annualised rate of 1,4 per cent. Similarly, employment in the construction sector decreased for a third consecutive quarter in the third quarter of 2013, with the pace of job shedding accelerating in each successive quarter. Around 8 000 formal construction jobs were lost in the first three quarters of 2013. Encouragingly, however, the FNB/BER Civil Confidence Index increased by a further 15 index points to 66 in the fourth quarter of 2013 – its highest level since the third quarter of 2008. The increase in confidence resulted from a rise in construction activity and a concomitant moderation in tendering competition. Profitability improved only modestly, while the pace of employment losses moderated. In addition, civil contractors expect the improvement in activity and profitability to continue in the first quarter of 2014.

Employment in the trade, catering and accommodation services sector increased at an annualised rate of 1,7 per cent in the third quarter of 2013, lifting employment to a level only slightly higher than that in the same period in the preceding year. Despite a disappointing decline in retail business confidence, the Retail Survey of the BER for the fourth quarter of 2013 showed a notable improvement in employment in that quarter. However, a meaningful acceleration in retail sales growth is not expected, while new vehicle sales contracted in the fourth quarter of 2013. Encouragingly, the depreciation in the exchange rate of the rand appears to have provided a fillip to the tourism industry, which should support employment creation in the sector.

According to the Quarterly Labour Force Survey (QLFS) conducted by Stats SA, the number of persons employed in South Africa increased by 653 000 in the year to the fourth quarter of 2013, representing a year-on-year growth rate in total employment of 4,5 per cent. In February 2014, Stats SA updated the QLFS results for the full sample period – 2008 to 2013 – to reflect the new population benchmarks obtained from Census 2011. This resulted in the total number of people employed being revised upwards over the full sample period, bringing the total level of employment to almost 15,2 million in the fourth quarter of 2013. The bulk of the employment opportunities that were created in the year to the fourth quarter of 2013 were created in the

| | |

| | Quarterly Bulletin March 2014 |

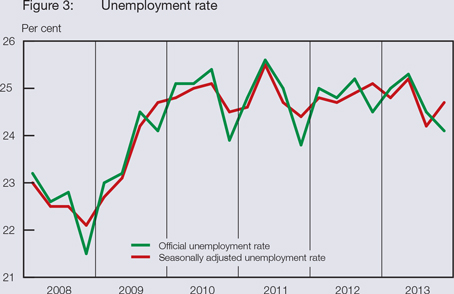

formal non-agricultural sectors of the economy, particularly in community and social services, trade, finance and other business services, transport and communication, and construction. In addition, 95 000 informal employment opportunities were created over the same period. The number of unemployed persons increased by 121 000 in the year to the fourth quarter of 2013, reducing the official unemployment rate in the South African economy to 24,1 per cent from 24,5 per cent a year earlier. (It was also 24,5 per cent in the third quarter of 2013.) The number of discouraged work-seekers, which registered a notable contraction of 128 000 in the third quarter of 2013, decreased by a further 97 000 in the fourth quarter of 2013. Encouragingly, youth unemployment receded for a third successive quarter in the fourth quarter of 2013, falling from 53,3 per cent in the first quarter of 2013 to 48,9 per cent in the fourth quarter.

Labour market statistics

Thousands

| | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | |

| | | Dec 2012 | | | Mar 2013 | | | Jun 2013 | | | Sep 2013 | | | Dec 2013 | |

a. Total employment | | | 14 524 | | | | 14 558 | | | | 14 692 | | | | 15 036 | | | | 15 177 | |

b. Total unemployment (official definition) | | | 4 709 | | | | 4 862 | | | | 4 972 | | | | 4 880 | | | | 4 830 | |

c. Total economically active (= a + b) | | | 19 233 | | | | 19 420 | | | | 19 663 | | | | 19 916 | | | | 20 007 | |

d. Total not economically active | | | 15 172 | | | | 15 138 | | | | 14 049 | | | | 14 952 | | | | 15 015 | |

e. Total aged 15–65 years (= c + d) | | | 34 405 | | | | 34 558 | | | | 34 712 | | | | 34 868 | | | | 35 022 | |

f. Official unemployment rate (= b*100/c) | | | 24,5 | % | | | 25,0 | % | | | 25,3 | % | | | 24,5 | % | | | 24,1 | % |

Source: Statistics South Africa, Quarterly Labour Force Survey

Box 1: Seasonally adjusting the official unemployment rate

Economic time series are often subject to seasonal fluctuations and other calendar effects, such as the number of trading days, weekends and public holidays in a month or quarter. These seasonal and calendar effects often mask the underlying movements in an economic time series, possibly resulting in an erroneous interpretation and analysis of the particular economic indicator. The aim of seasonal adjustment1 is to filter out seasonal and calendar effects that occur repeatedly in the same season and with similar intensity on an annual basis in an economic time series, thereby facilitating more accurate economic analysis of the time series. At the same time it is inappropriate to make any seasonal or calendar adjustment to a time series in the absence of clear statistical evidence and economic interpretation of the effect.

The unemployment rate is an extremely important macroeconomic indicator, particularly in the South African context, given government’s overarching policy objective of eradicating unemployment, inequality and poverty. The official South African unemployment rate has been available on a quarterly basis since the first quarter of 20082 and is calculated as the ratio of those persons who are classified as being unemployed to the total economically active population, expressed as a percentage. The calculation is depicted in the formulas below.

| | |

Employed + Unemployed = Economically Active Population Unemployment Rate = (Unemployed / Economically Active Population) * 100 | | |

In seasonally adjusting the official unemployment rate, the Bank employed the indirect method of seasonal adjustment, since the components comprising the total economically active population (i.e., employed and unemployed persons) could exhibit different seasonal patterns. Thus the two time series – the number of unemployed and employed persons – were tested separately for seasonality.3 Where seasonality was found to be present it was adjusted for, and the seasonally adjusted component time series were then used to calculate the seasonally adjusted unemployment rate, according to the formula above.

| 1 | According to the European Statistical System Guidelines on Seasonal Adjustment (2009 edition by Eurostat, European Commission), seasonal adjustment also includes the adjustment for calendar effects, such as the number of working days or trading days in a month, or particular dates that can statistically be shown to make a difference in the data, such as public holidays, or the number of weekends in a month. |

| 2 | Published by Statistics South Africa in the Quarterly Labour Force Survey. |

| 3 | Seasonal adjustment was done using the X12-ARIMA approach (supported by the Bureau of Census in the United States). |

| | |

| Quarterly Bulletin March 2014 | |  |

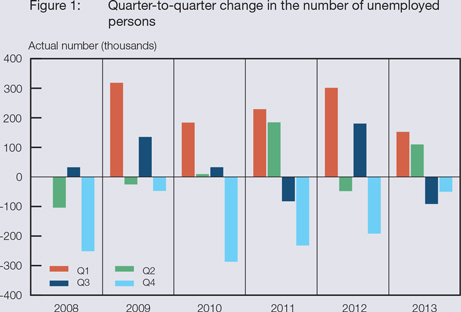

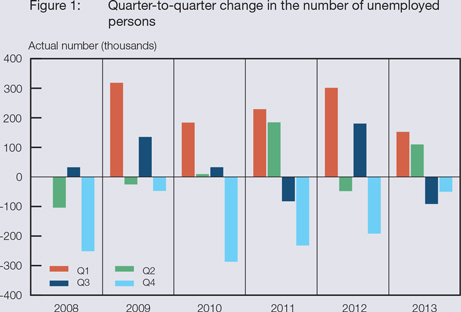

Figure 1 shows that the number of unemployed persons usually decreases notably in the fourth quarter of each year and subsequently increases markedly in every first quarter. This can largely be explained by the temporary employment of casual workers in the trade, catering and accommodation services sector in the fourth quarter of each year. In addition to these temporary employees then becoming unemployed again in the first quarter of the following year, the large number of school leavers becoming economically active contributes further to the increase in the number of unemployed persons in the first quarter of each year.

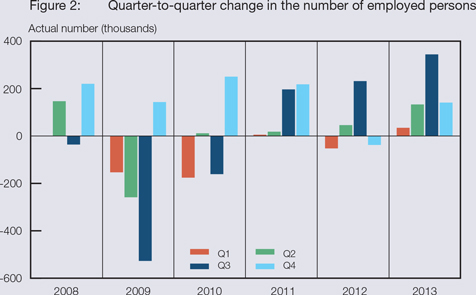

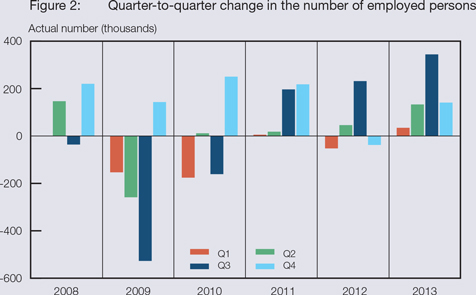

Figure 2 depicts the quarter-to-quarter change in the number of employed persons. The increase in employment in the fourth quarter of each year and the subsequent decrease in the first quarter of each year are neither as pronounced nor as consistent as that observed in the number of unemployed persons in Figure 1. As such, the statistical results show that the time series measuring the number of unemployed persons is influenced by seasonality, while the time series measuring the number of employed persons is not.

| | |

| | Quarterly Bulletin March 2014 |

Individual tests for seasonality indicated significant seasonality in the time series measuring the number of unemployed persons at the 1 per cent confidence level for the Friedman test, the Kruskal-Wallis test, as well as the test for the presence of seasonality assuming stability. However, due to the relatively short data span the Evolutive seasonality test revealed no evidence of a change in the seasonal pattern over time, resulting in the combined test for significant seasonality to be inconclusive. As more data become available the combined test for significant seasonality should become more reliable and conclusive. However, due to the statistical evidence indicating a stable seasonal pattern, it seems prudent to seasonally adjust the time series measuring the number of unemployed persons.

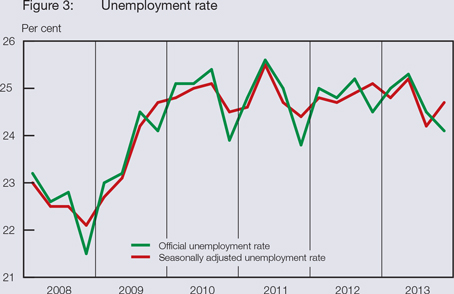

The seasonally adjusted unemployment rate was obtained by substituting the non-seasonally adjusted time series measuring the number of unemployed persons by its seasonally adjusted version in the formula calculating the unemployment rate. The seasonally adjusted unemployment rate is shown in Figure 3, together with the official unemployment rate. The seasonally adjusted unemployment rate is consistently lower than the official unemployment rate in the first quarter of each year, while it is consistently higher than the official unemployment rate in the fourth quarter of each year, thereby reducing the overall volatility in the indicator and providing a more steady measure of the domestic unemployment rate. Henceforth, both the official and the seasonally adjusted unemployment rate will be included in table KB814 on page S–154 of the Quarterly Bulletin. As with all seasonally adjusted data, the seasonally adjusted unemployment rate is subject to revision as further observations are added to the time series.

According to the latest Global Employment Trends 2014 Report of the International Labour Organization (ILO), labour markets have been adversely affected by the slower-than-expected global economic recovery. Employment growth slowed in 2013 across most regions, leading to a further increase in unemployment rates. Global employment rose by only 1,4 per cent in 2013 – broadly unchanged from the pace of increase in 2012 – but slower than in any year during the pre-crisis decade. The report further states that employment growth deteriorated in every geographic region except in South Asia and North Africa. The global unemployment rate remained unchanged at 6,0 per cent in 2013, compared with the preceding year. The number of unemployed persons around the world is estimated to have reached 202 million in 2013, an increase of 5 million from a revised 197 million in the previous year. The labour market outlook for young people worsened in nearly every region of the world. Globally the youth unemployment rate rose to 13,1 per cent in 2013, up from 12,9 per cent in 2012 and 11,6 per cent in 2007.

| | |

| Quarterly Bulletin March 2014 | |  |

Labour cost and productivity

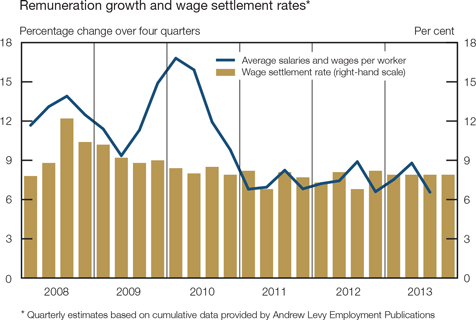

The pace of increase in total nominal salaries and wages per worker moderated notably from a year-on-year rate of 8,8 per cent in the second quarter of 2013 to 6,6 per cent in the third quarter due to a marked deceleration in public-sector wage growth. Consequently, growth in the real take-home pay of those formally employed in the non-agricultural sector of the economy decelerated from 2,7 per cent in the year to the second quarter of 2013 to 0,6 per cent in the year to the third quarter. Public-sector wages per worker increased at a rate of 3,1 per cent in the year to the third quarter of 2013, notably slower than the rate of increase of 11,7 per cent recorded in the year to the second quarter. The deceleration resulted mainly from the high remuneration base created in the third quarter of 2012, when civil servants at national departments and provinces received a backdated salary increase.

By contrast, the pace of increase in private-sector salaries and wages per worker accelerated continually during 2013, amounting to a year-on-year rate of 7,3 per cent in the second quarter and 8,1 per cent in the third quarter. Remuneration growth varied widely within the different private subsectors in the third quarter of 2013, with the gold-mining sector (14,6 per cent) and the trade, catering and accommodation services sector (12,4 per cent) recording double-digit year-on-year increases, while the lowest increases were recorded in the electricity sector (1,8 per cent) and the construction sector (5,2 per cent). Other subsectors where remuneration increases were higher than the 6 per cent upper limit of the inflation targeting band were the private community, social and personal services sector (6,6 per cent); the finance, insurance, real-estate and business services sector (6,8 per cent); the non-gold mining sector (6,8 per cent); the private transport, storage and communication services sector (7,1 per cent) and the manufacturing sector (8,3 per cent).

According to Andrew Levy Employment Publications, the overall average wage settlement rate in collective bargaining agreements amounted to 7,9 per cent in 2013, marginally above the average settlement rate of 7,6 per cent recorded in 2012. The number of workdays lost due to industrial action rose from 3,5 million in 2012 to 5,2 million in 2013, largely due to the conclusion of a number of multi-year wage negotiations resulting in increased labour unrest in various economic sectors. Workdays lost peaked at 2,9 million in the third quarter of 2013.

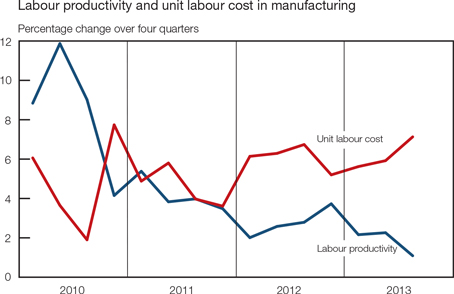

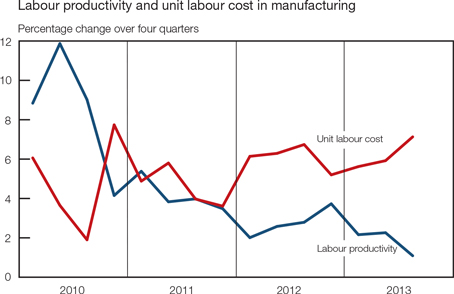

Year-on-year growth in total non-agricultural employment accelerated marginally, while that in real output decelerated in the third quarter of 2013, resulting in a moderation in productivity growth from 1,8 per cent in the second quarter of 2013 to 1,6 per cent in the third quarter. Similarly, productivity growth in the manufacturing sector decelerated from 2,6 per cent in the year to the second quarter of 2013 to 1,3 per cent in the year to the third quarter.

| | |

| | Quarterly Bulletin March 2014 |

Nominal remuneration growth per worker in the formal non-agricultural sector of the economy decelerated at a faster pace than output growth, resulting in a notable slowdown in year-on-year nominal unit labour cost inflation from 6,9 per cent in the second quarter of 2013 to 4,9 per cent in the third quarter. However, the marked deceleration in public-sector remuneration growth, largely due to base effects, assisted this moderation in unit labour cost inflation. When assessing unit labour cost developments by applying the broader national accounts measure of compensation of employees per unit of output,2 the year-on-year rate of increase in unit labour cost decelerated less sharply from 7,7 per cent in the second quarter of 2013 to 6,9 per cent in the third quarter. These values still exceeded the upper limit of the inflation target range.

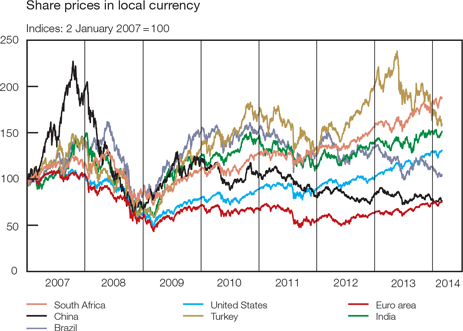

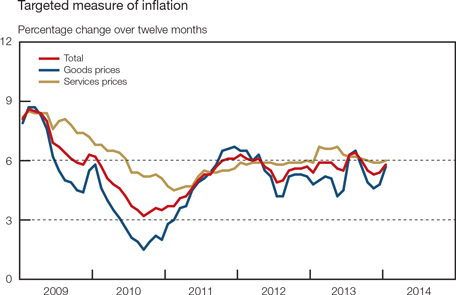

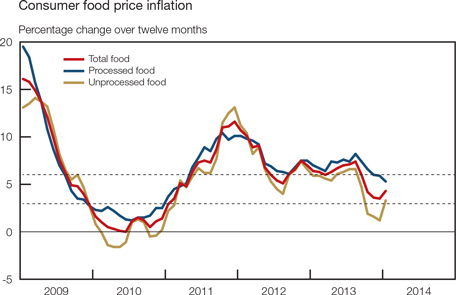

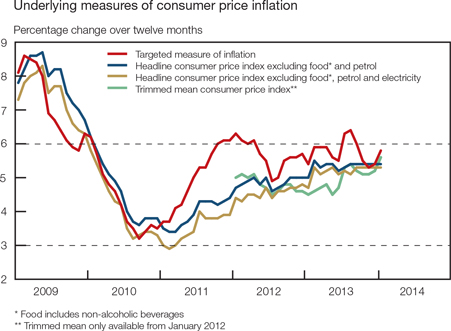

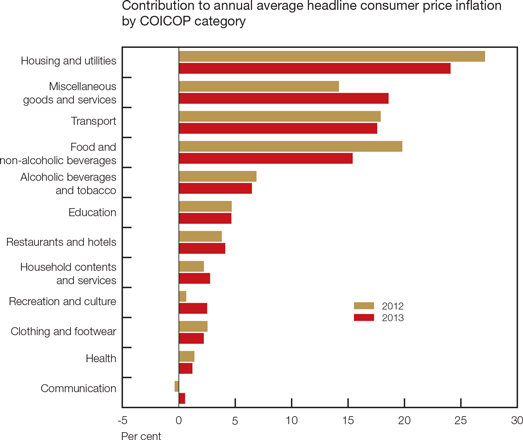

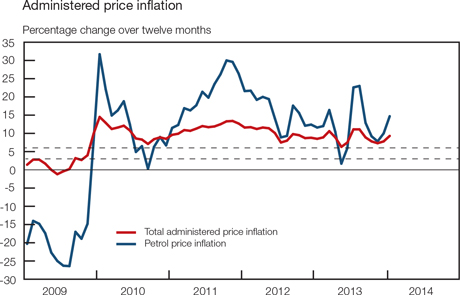

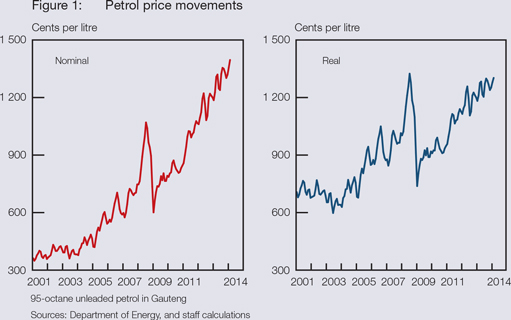

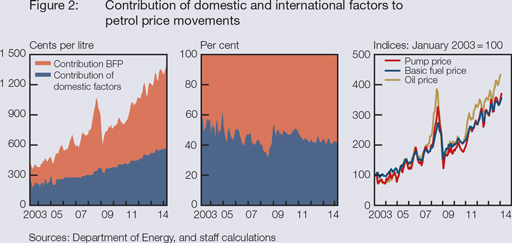

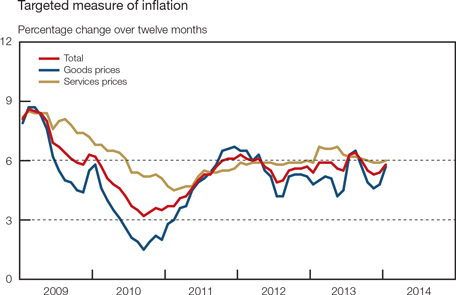

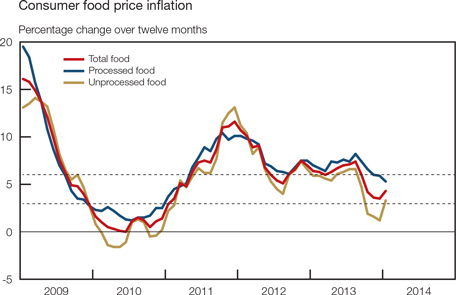

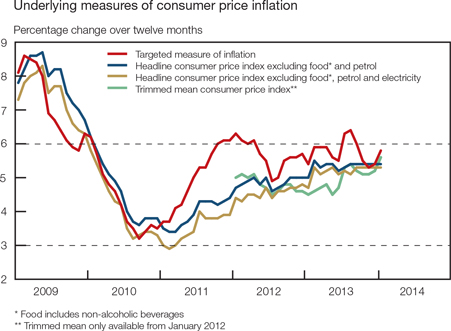

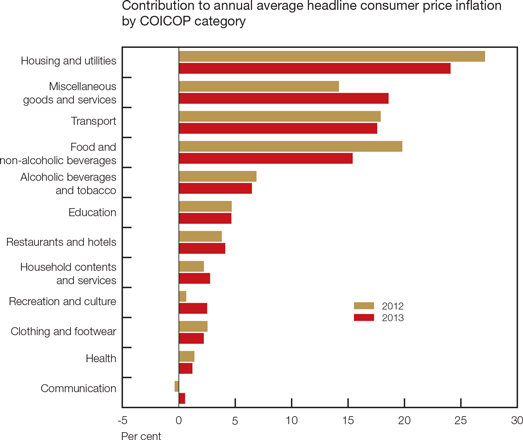

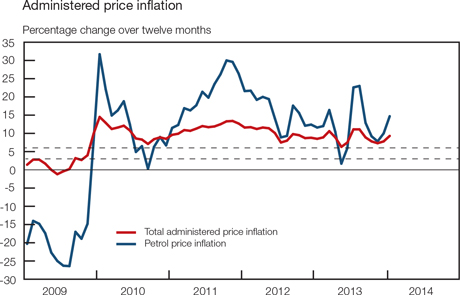

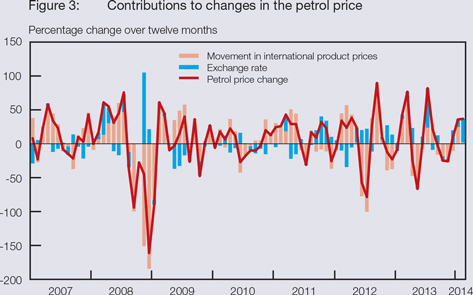

Prices

Within an environment of slowing output growth in 2013, the annual average headline consumer price inflation rate in South Africa remained contained within the inflation target range at 5,7 per cent, having accelerated only marginally compared with the preceding year. Having slightly exceeded the inflation target range in July and August 2013, headline inflation moderated to 5,4 per cent in December, before quickening to 5,8 per cent in January 2014.3 Recent movements in consumer price inflation can largely be ascribed to fluctuations in food and petrol prices, with underlying inflationary pressures remaining fairly stable. Key barometers of underlying inflation remained significantly below the upper limit of the inflation target range of 3 to 6 per cent, despite the protracted depreciation in the exchange rate of the rand.

The inflationary impact of the lower exchange value of the rand has thus far been more visible in domestic producer price inflation than in consumer price inflation. Producer price inflation for final manufactured goods accelerated to 7,0 per cent in January 2014, with price inflation remaining elevated in most subcategories of final manufactured goods. Disconcertingly, producer price inflation for intermediate manufactured goods almost doubled from 5,8 per cent in January 2013 to 11,1 per cent in August, before decelerating somewhat to 7,5 per cent in November. Producer price inflation for intermediate manufactured goods subsequently quickened to 9,3 per cent in January 2014. Inflationary pressures were prevalent throughout most subcategories of intermediate manufactured goods, with the prices of textiles and leather goods, chemicals, rubber products, glass products, and basic iron and steel products all registering double-digit rates of increase over the twelve months to January 2014. These price pressures do not augur well for inflation in the prices of final manufactured goods in coming months.

Most measures of producer price inflation accelerated in the closing months of 2013. Producer price inflation for mining products quickened from -0,2 per cent in October 2013 to 4,8 per cent in January 2014, while producer price inflation for agriculture, forestry and fishing products

| | |

| Quarterly Bulletin March 2014 | |  |

accelerated from 1,8 per cent to 5,6 per cent over the same period. Of note is the fact that producer price inflation for fishing products accelerated briskly throughout 2013, amounting to 22,3 per cent in January 2014. Producer price inflation for electricity and water accelerated markedly and came to 14,5 per cent in January 2014, mainly on account of increases in the price of electricity.

Price inflation for imported commodities remained fairly elevated in recent months mainly due to the downward trend in the exchange value of the rand, but moderated from 9,7 per cent in October 2013 to 7,0 per cent in December. Partly driven by crude oil, price inflation of imported mining commodities in particular remained high, amounting to 20,3 per cent in October 2013 before slowing to 13,3 per cent in December. Conversely, price inflation of imported manufactured products remained fairly stable and well contained at around 2,8 per cent in the second half of 2013.

Recent movements in headline consumer price inflation resulted largely from changes in consumer goods price inflation, in turn driven almost exclusively by changes in non-durable goods price inflation. Consumer goods price inflation accelerated to 6,5 per cent in August 2013, before moderating to 4,6 per cent in November. Similarly, non-durable goods price inflation quickened to 8,9 per cent before slowing to 5,4 per cent over the same period, largely due to movements in petrol and food prices. Subsequently, consumer goods price inflation accelerated somewhat to 5,7 per cent in January 2014, as petrol price inflation in particular quickened notably.

Despite the prolonged yet until recently fairly gradual depreciation in the exchange rate of the rand, little pass-through to consumer goods price inflation has thus far been observed. As such, semi-durable goods price inflation has remained fairly stable around the 3 per cent level throughout 2013, accelerating only marginally from 2,9 per cent in October to 3,8 per cent in January 2014. Following a prolonged period of deflation, durable goods price inflation accelerated gradually from a recent low of -0,8 per cent in February 2013 to 2,4 per cent in January 2014, largely due to an acceleration in new motor vehicle price inflation from 2,3 per cent to 5,8 per cent over the same period. However, the depreciation in the exchange rate of the rand became more pronounced in January 2014, suggesting an increased risk of accelerating domestic consumer goods price inflation in coming months.

The limited pass-through from the depreciation in the exchange rate of the rand to domestic inflation was probably related to a range of factors, including:

| • | | surplus capacity in the economy leading to stronger competition among producers; |

| | |

| | Quarterly Bulletin March 2014 |

| • | | tight consumer budgets and conservatism among lenders and borrowers alike about the use and extension of credit; |

| • | | the length of the supply chain, inventory buffers and the use of instruments to hedge against exchange rate movements; |

| • | | continued inroads into the South African market by imports from the lowest-cost countries; |

| • | | technological advances lowering the real prices of a range of products such as telecommunication equipment and computers; and |

| • | | benign inflation expectations shaped by the generally successful inflation outcomes under inflation targeting. |

Consumer services price inflation slowed gradually from 6,7 per cent in May 2013 to 6,0 per cent in January 2014, reflecting a marked moderation in transport services price inflation and to a lesser extent a slower pace of increase in the prices of recreation and culture services. In the closing months of 2013 miscellaneous services price inflation also decelerated somewhat on account of a slowdown in funeral services price inflation. Conversely, housing and utilities service price inflation accelerated marginally from 4,9 per cent in October 2013 to 5,2 per cent in January 2014, as house rental price inflation picked up in the final quarter of the year.

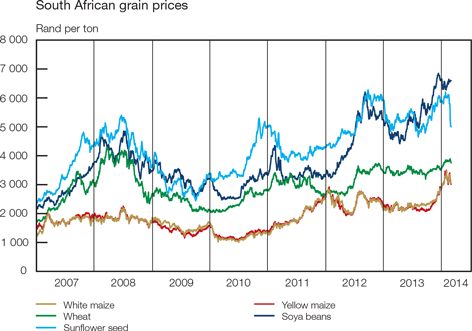

Domestic food price pressures diminished somewhat in the closing months of 2013, following record international maize crops and relatively low domestic meat prices. As such, final manufactured producer food price inflation decelerated from 7,5 per cent in July 2013 to 5,2 per cent in November, before quickening to 6,7 per cent in January 2014. The moderation in final manufactured producer food price inflation resulted largely from a slower rate of increase in the price of meat, grain mill products, starch products and bakery products. Consequently, final manufactured producer food price inflation decelerated from an annual average rate of 8,4 per cent in 2012 to 6,4 per cent in 2013.

Final manufactured producer food prices

Annual average percentage change

| | | | | | | | |

| | | Weights | | | 2013 | |

Meat and meat products | | | 3,69 | | | | 5,5 | |

Fish and fish products | | | 1,49 | | | | 10,7 | |

Fruit and vegetables | | | 2,66 | | | | 3,7 | |

Oils and fats | | | 0,32 | | | | 8,1 | |

Dairy products | | | 2,81 | | | | 7,3 | |

Grain mill products | | | 2,13 | | | | 3,9 | |

Starch products | | | 1,32 | | | | 7,8 | |

Bakery products | | | 6,12 | | | | 10,8 | |

Sugar | | | 1,79 | | | | -0,3 | |

Other food products | | | 1,67 | | | | -0,5 | |

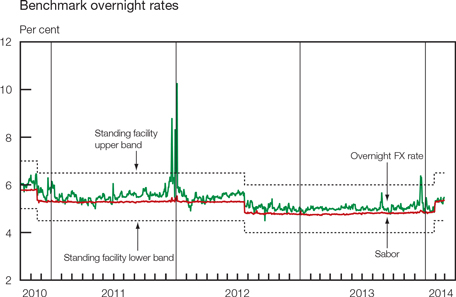

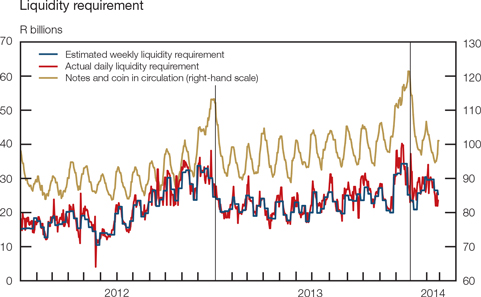

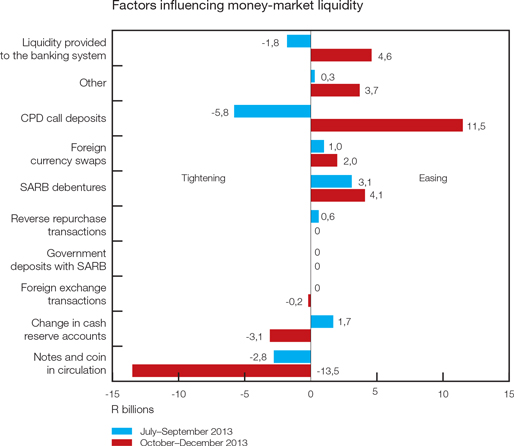

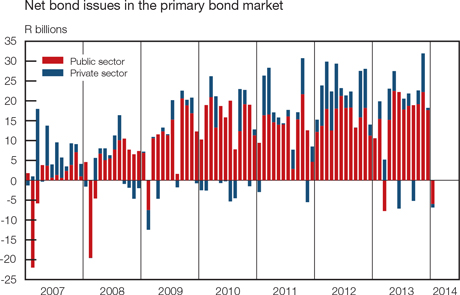

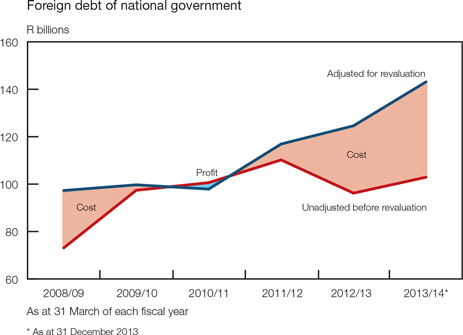

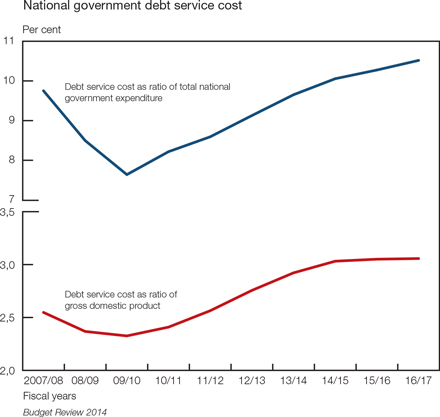

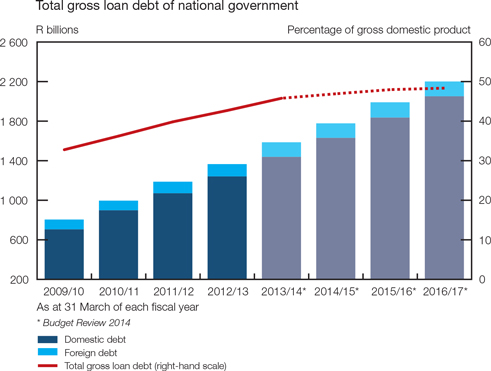

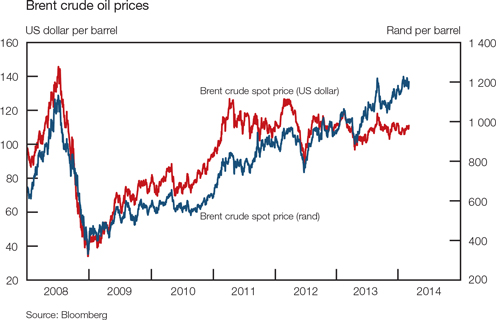

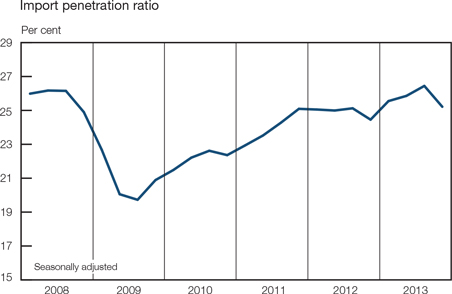

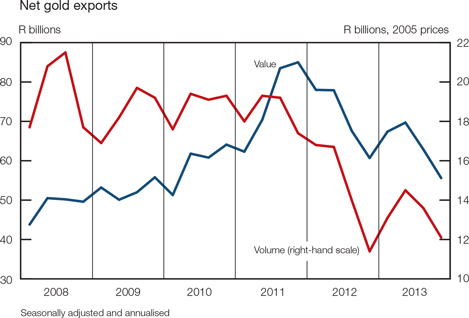

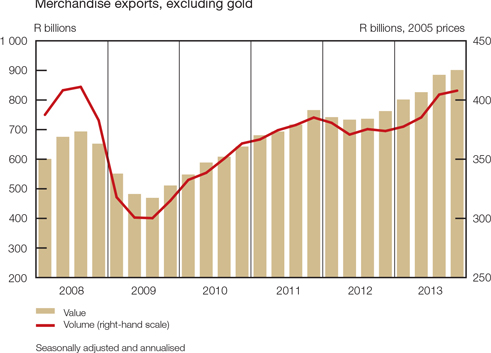

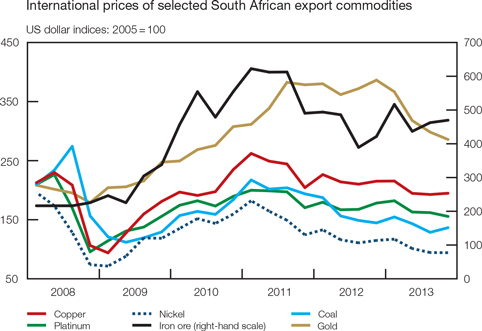

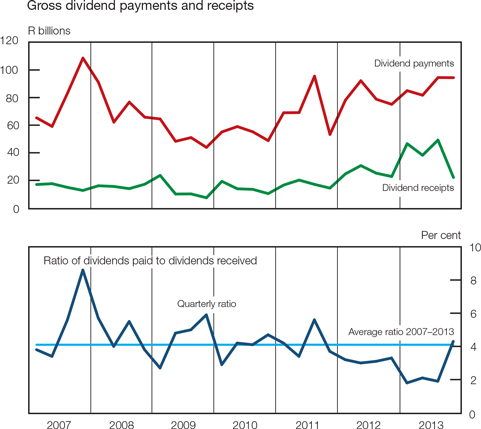

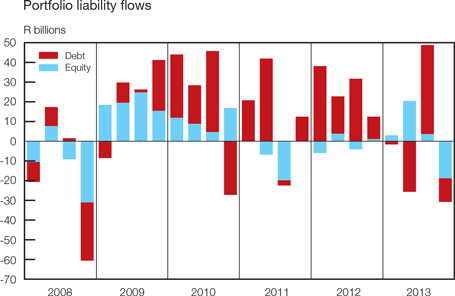

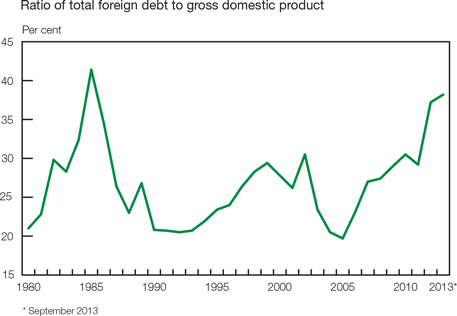

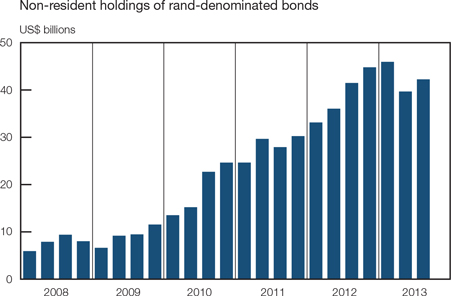

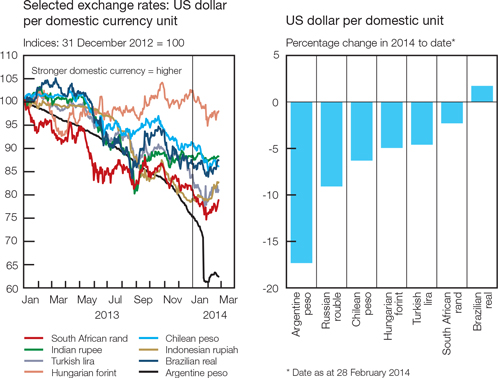

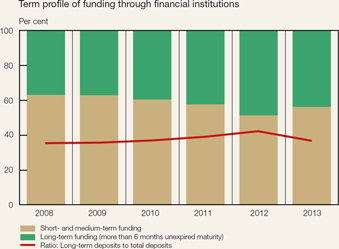

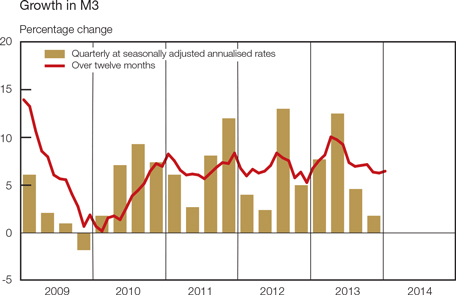

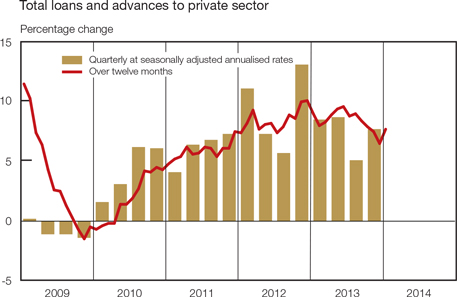

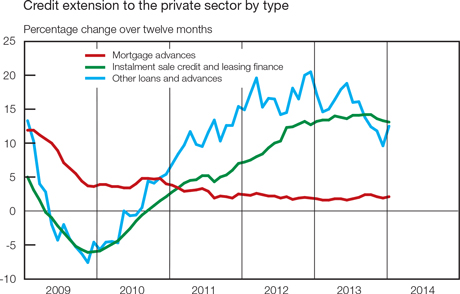

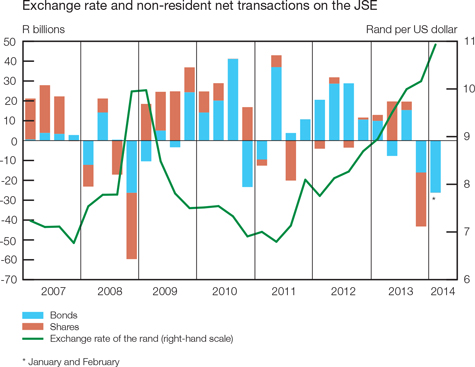

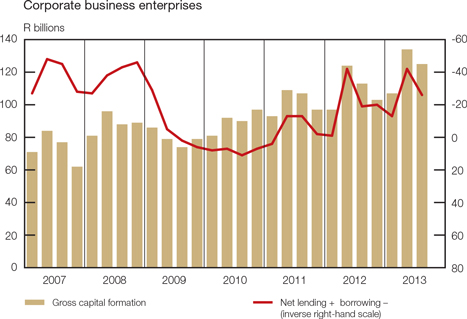

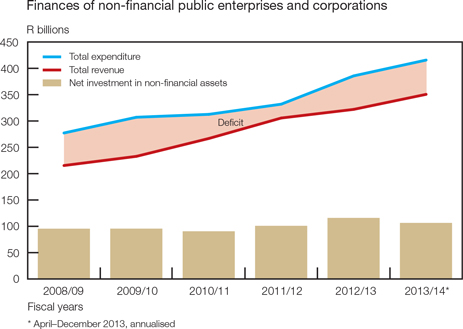

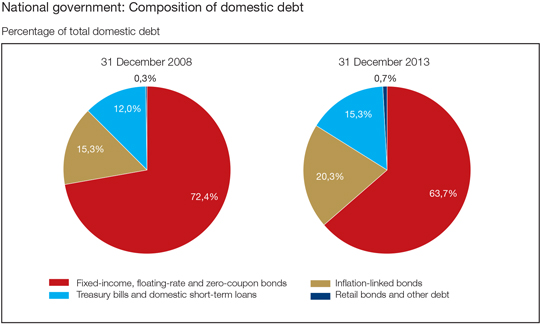

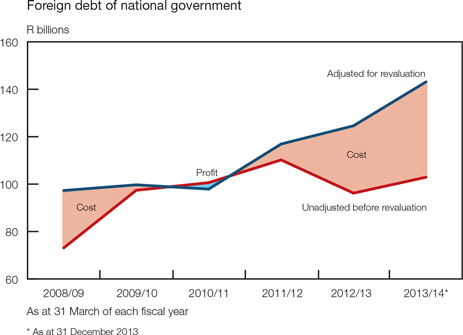

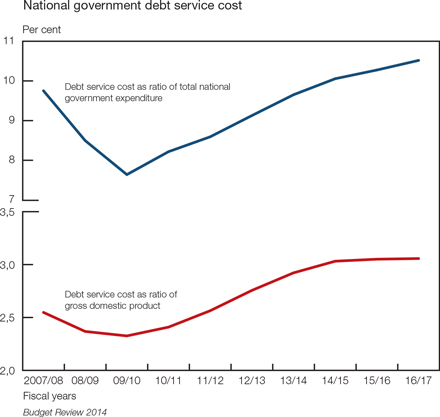

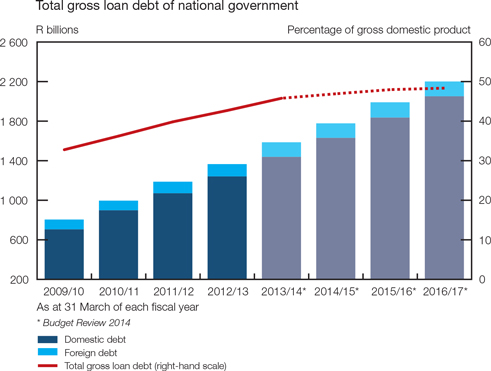

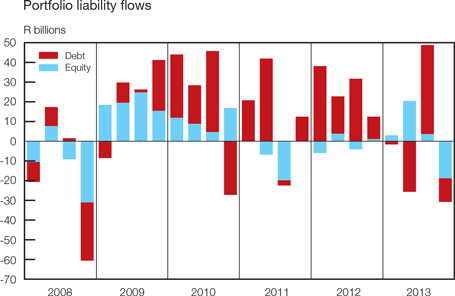

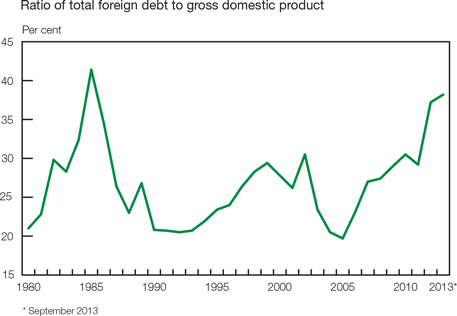

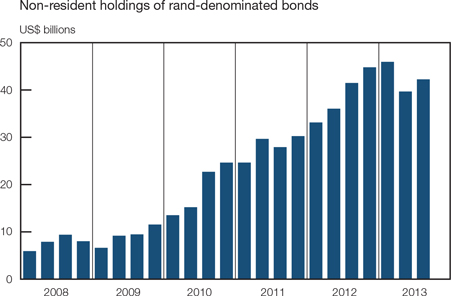

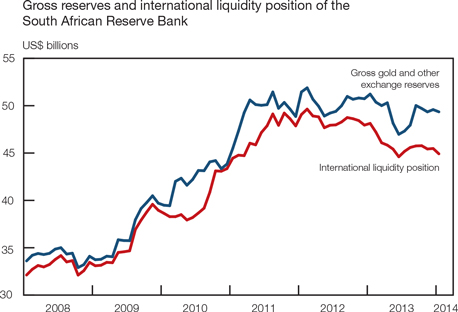

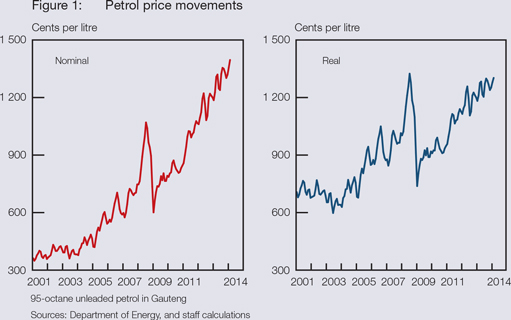

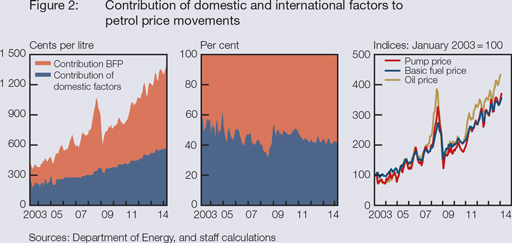

All items | | | 24,00 | | | | 6,4 | |