EXHIBIT 99.D

DESCRIPTION OF THE REPUBLIC OF SOUTH AFRICA

DATED December 4, 2015

INCORPORATION OF DOCUMENTS BY REFERENCE

This document is an exhibit to the Republic of South Africa’s Annual Report on Form 18-K under the Exchange Act of 1934 for the fiscal year ended March 31, 2015. All amendments to such Annual Report on Form 18-K/A filed by South Africa following the date hereof shall be incorporated by reference into this document. Any statement contained in a document, all or a portion of which is incorporated or deemed to be incorporated by reference herein, shall be deemed to be modified or superseded for purposes of this document to the extent that a statement contained herein or in any other subsequently filed document that also is or is deemed to be incorporated by reference herein modified or supersedes such statement. Any statement so modified or superseded shall not be deemed, except as so modified or superseded, to constitute a part of this document.

1

TABLE OF CONTENTS

| | | | |

SUMMARY INFORMATION | | | 3 | |

| |

INTRODUCTION | | | 5 | |

| |

REPUBLIC OF SOUTH AFRICA | | | 7 | |

Area and Population | | | 8 | |

Government and Political Parties | | | 8 | |

Legal System | | | 14 | |

Broad-Based Black Political Empowerment | | | 14 | |

Land Reform | | | 16 | |

Mining Industry Reform | | | 17 | |

Crime Prevention | | | 23 | |

International Relations | | | 27 | |

Development Finance Institutions (DFIs) | | | 30 | |

Public Health | | | 31 | |

| |

THE SOUTH AFRICAN ECONOMY | | | 35 | |

Overview | | | 35 | |

Implementing the National Development Plan 2030: The Medium-Term Strategic Framework | | | 36 | |

GDP | | | 37 | |

GDE | | | 40 | |

Principal Sectors of the Economy | | | 43 | |

Informal Sector of the Economy | | | 64 | |

Employment and Trade Unions | | | 65 | |

Prices and Wages | | | 71 | |

| |

MONETARY AND FINANCIAL SYSTEM | | | 73 | |

The SARB | | | 73 | |

Monetary Policy | | | 74 | |

Financial System Stability | | | 79 | |

Regulation of the Financial Sector | | | 79 | |

Financial Sector Charter | | | 85 | |

Credit Allocation | | | 86 | |

Capital Markets | | | 89 | |

Exchange Controls | | | 92 | |

Gold and Foreign Exchange Contingency Reserve Account (GFECRA) | | | 97 | |

| |

THE EXTERNAL SECTOR OF THE ECONOMY | | | 99 | |

Foreign Trade | | | 99 | |

Balance of Payments | |

| 103

|

|

Current Account | |

| 105

|

|

Financial Account | |

| 106

|

|

Reserves and Exchange Rates | |

| 110

|

|

Change in Reserves | |

| 112

|

|

| |

PUBLIC FINANCE | | | 113 | |

Background | | | 119 | |

The Budget Process | | | 120 | |

MTBPS | | | 120 | |

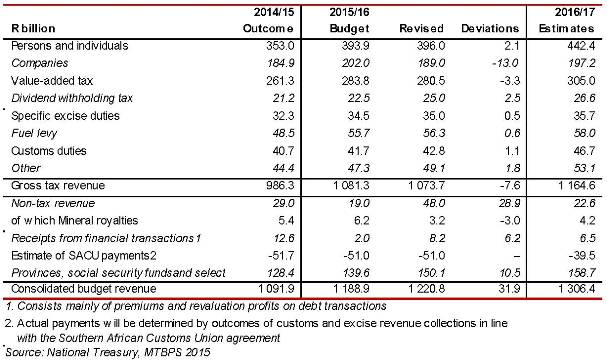

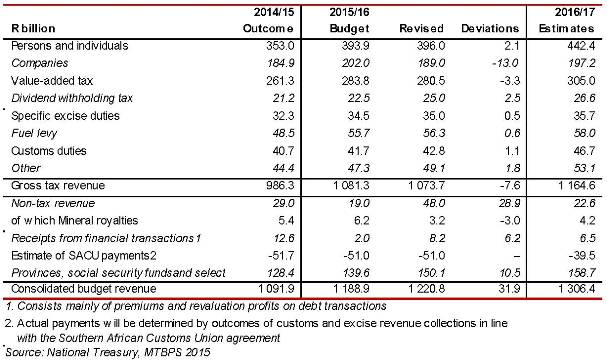

2015-2016 National Budget and Consolidated Budgets | | | 122 | |

Taxation | | | 126 | |

Revenue | | | 131 | |

Financing | | | 132 | |

Public Enterprises | | | 133 | |

| |

NATIONAL GOVERNMENT DEBT | | | 144 | |

General | | | 144 | |

Summary of Internal National Government Debt | | | 145 | |

Summary of External National Government Debt | | | 145 | |

Guaranteed Debt | | | 146 | |

Debt Service Costs | | | 147 | |

Debt Record | | | 148 | |

Tables and Supplementary Information | | | 149 | |

2

In this document, the government of the Republic of South Africa is referred to as the “National Government,” “the Government” or the “South African Government”. The currency of the Republic of South Africa (South Africa) is the South African Rand. In this document, all amounts are expressed in South African Rand (R or Rand) or U.S. Dollars (US$, $ or Dollars), except as otherwise specified. See “The External Sector of the Economy—Reserves and Exchange Rates” for the average rates for the Rand against the Dollar for each of the years 2009 through 2014 and for the 11-month period ended November 30, 2015. On December 3, 2015, the exchange rate, as reported by the South African Reserve Bank (SARB), was R14.3328 per Dollar (or 0.0697 U.S. cents per Rand).

The Republic’s fiscal year begins on April 1 and ends on March 31. For example, the 2015 fiscal year refers to the fiscal year beginning April 1, 2014 and ending March 31, 2015. Economic data presented in this description is presented on a calendar year basis unless reference is made to the relevant fiscal year or the fiscal year is otherwise indicated by the context. For example, economic data referring to the “first quarter” of 2015 refers to data as at, or for the three months ended, June 30, 2015. Economic data referring to the “first three months” of 2015, by contrast, refers to data as at, or for the three months ended, March 31, 2015.

Unless otherwise indicated, references to gross domestic product (GDP) are to real GDP, calculated using constant prices in order to adjust for inflation (with 2010 as a base year), and % changes in GDP refer to changes as compared to the previous year or the same quarter of the previous year, unless otherwise indicated.

Unless otherwise stated herein, references in this description to the 2015-2016 Budget are to the 2015-2016 National Budget as released in February 2015 and not as amended by the Medium-Term Budget Policy Statement (MTBPS) released on October 22, 2015. References to the 2015-2016 Consolidated Budget, which includes the 2015-2016 National Budget as part thereof, shall be construed accordingly.

Some figures included in this document have been subject to rounding adjustments. As a result, sum totals of data presented in this document may not precisely equate to the arithmetic sum of the data being totaled.

SUMMARY INFORMATION

The following summary tables do not purport to be complete and are qualified in their entirety by the more detailed information appearing elsewhere in this document.

The following tables set forth certain summary statistics about the economy of South Africa, public finance and debt of the National Government for the periods indicated.

3

| | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | |

| | | As of and for the year ended December 31, | | | As of and for

the six months

ended June 30,(1) | |

| | | 2010 | | | 2011 | | | 2012 | | | 2013 | | | 2014 | | | 2015 | |

| | | Rand (million) (except percentages) | |

The Economy | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | |

Gross Domestic Product (GDP) | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | |

Nominal GDP(2) | | | 2,748,008 | | | | 3,024,950 | | | | 3,262,542 | | | | 3,534,326 | | | | 3,796,462 | | | | 3,942,919 | (3) |

Real GDP(4) | | | 2,748,008 | | | | 2,836,286 | | | | 2,899,248 | | | | 2,963,389 | | | | 3,008,576 | | | | 3,045,469 | (3) |

Real % change from prior year | | | 3.0 | % | | | 3.2 | % | | | 2.2 | % | | | 2.2 | % | | | 1.5 | % | | | 1.8 | % |

Change in per capita earnings (%)(5) | | | 3.4 | % | | | 2.9 | % | | | 0.5 | % | | | (0.4 | )% | | | (0.3 | )% | | | N/A | |

Total merchandise exports | | | 68,856 | | | | 794,743 | | | | 825,025 | | | | 932,588 | | | | 1,003,826 | | | | 502,593 | (6) |

Unemployment rate (%) | | | 24.9 | % | | | 24.80 | % | | | 24.9 | % | | | 24.7 | % | | | 25.1 | % | | | 25.5 | %(7) |

Balance of trade (Rand billion) (13) | | | 59.7 | | | | 51.0 | | | | (31.5 | ) | | | (68.3 | ) | | | (68.6 | ) | | | (14.3 | )(6) |

Balance of payments | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | |

Current account | | | (41.245 | ) | | | (65,287 | ) | | | (161,704 | ) | | | (203,774 | ) | | | (206,644 | ) | | | (71,229 | )(6) |

Financial account | | | 56,128 | | | | 65,896 | | | | 173,245 | | | | 130,403 | | | | 155,809 | (7) | | | 36,695 | (6) |

Change in gross gold and other foreign reserves | | | (24,075 | ) | | | (107,193 | ) | | | 33,123 | | | | 89,247 | | | | 48,335 | | | | 2,686 | (6) |

Rand/Dollar exchange rate (average) | | | 7.32 | | | | 7.25 | | | | 8.21 | | | | 9.65 | | | | 10.84 | | | | 12.45 | (8) |

Consumer prices (2012/12=100) | | | 88.2 | | | | 92.6 | | | | 97.8 | | | | 103.4 | | | | 109.7 | | | | 113.6 | (9) |

Producer prices (2012/12=100))(14) | | | N/A | | | | N/A | | | | 100 | | | | 106 | | | | 113.9 | | | | 116.7 | (9) |

Average monthly yields for listed National Government debt securities 5-10 yrs | | | 7.41 | | | | 8.01 | | | | 6.50 | | | | 7.73 | | | | 7.39 | | | | 7.96 | |

Average monthly yields for listed National Government debt securities > 10 yrs | | | 8.38 | | | | 8.51 | | | | 7.37 | | | | 8.32 | | | | 7.84 | | | | 8.33 | |

| | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | |

| | | As of and for the fiscal year ended March 31, | |

| | | 2010 | | | 2011 | | | 2012 | | | 2013 | | | 2014 | | | 2015(11) | | | 2016(12) | |

Main Government Revenue | | | 586,113.1 | | | | 672,751.5 | | | | 745,292.2 | | | | 799,761.7 | | | | 887,265.1 | | | | 963,560.6 | | | | 1,070,664.5 | |

% of GDP(2) | | | 23.8 | % | | | 27.7 | % | | | 28.2 | % | | | 28.4 | % | | | 29.2 | % | | | 28.4 | % | | | 29.8 | % |

Main Government Expenditure | | | 747,868 | | | | 805,979.1 | | | | 889,911.5 | | | | 965,495.6 | | | | 1,047,758.6 | | | | 1,131,951.8 | | | | 1,246,929.6 | |

% of GDP(2) | | | 30.5 | % | | | 32.0 | % | | | 32.0 | % | | | 32.7 | % | | | 33.2 | % | | | 32.0 | % | | | 33.6 | % |

Main Budget Deficit | | | (161,754.9 | ) | | | (133,227.7 | ) | | | (144,619.3 | ) | | | (165,733.9 | ) | | | (160,493 | ) | | | (168,391.2 | ) | | | (176,266 | ) |

% of GDP(2) | | | (6.3 | )% | | | (4.7 | )% | | | (4.7 | )% | | | (5.0 | )% | | | (4.4 | )% | | | (4.4 | )% | | | (4.3 | )% |

Net borrowing requirement | | | (161,754.9 | ) | | | (133,227.7 | ) | | | (144,620.2 | ) | | | (165,353.3 | ) | | | (160,498.7 | ) | | | (168,391.2 | ) | | | (176,265.2 | ) |

Change in cash and other balances(10) | | | (30,128.7 | ) | | | (41,354.7 | ) | | | (21,741.4 | ) | | | 29,033.1 | | | | (12,346.4 | ) | | | (6,548.8 | ) | | | 8,857.2 | |

Notes:—

N/A = not available

| (1) | First half of 2015, seasonally adjusted and annualized. |

4

| (3) | Estimate for first half of 2015, seasonally adjusted and annualized. |

| (4) | At constant 2010 prices. |

| (5) | Real growth rate in per capita earnings, at constant 2010 prices. |

| (6) | Estimates to June 30, 2015. |

| (7) | Quarterly Labour Force Survey (QLFS) as of September 30, 2015. |

| (8) | Rand/Dollar rates are averages for the period through July 2015. |

| (9) | As of July 30, 2015. Calculated based on the average values over the seven months. |

| (10) | The total debt of National Government (net) is calculated with due account of the bank balances of the National Revenue Fund (balances of National Government’s accounts with the SARB and the Tax and Loans Accounts with commercial banks). |

| (11) | Final outcome for fiscal year 2015, as reflected in the MTBPS (October 2015). |

| (12) | Estimates as revised and reflected in the MTBPS (October 2015). |

| (13) | Total Trade figures from 2013 onwards includes trade with Botswana, Lesotho, Namibia and Swaziland (BLNS countries). |

| (14) | Due to a rebasing in 2012, figures prior to 2012 are not available. |

Source: South African National Treasury, SARB and Statistics SA (Stats SA).

The estimates included in this Annual Report are based on the 1993 System of National Accounts (SNA) published by the United Nations in cooperation with other international organizations. This means that the methodology, concepts and classifications are in accordance with the latest guidelines of an internationally agreed system of national accounts. The estimates of real GDP are expressed in terms of a 2010 base year. Revision of the estimates for all components of the national accounts is done from time to time based on the availability of data.

Statistics South Africa (Stats SA), who compiles the expenditure side of national accounts, has rebased certain GDP estimates in the Statistical Release, P0441, Gross Domestic Product, Third Quarter 2014 dated November 25, 2014 in terms of a 2010 base year.

INTRODUCTION

South Africa has been an established constitutional democracy since 1994, when it held its first fully democratic national elections. The South African economy is diverse and supported by a well-developed legal system and a sophisticated financial system. The major strengths of the South African economy are its services and manufacturing sectors, its strong physical and economic infrastructure and its abundant natural resources, including gold, platinum metals and coal.

The country’s fifth fully democratic national elections took place in May 2014, and saw the ruling African National Congress (ANC) maintaining its significant majority in Parliament. A number of minority parties make up the balance of the seats presently held in the National Assembly, including the National Freedom Party (NFP, six seats), United Democratic Movement (UDM, four seats), the Freedom Front Plus (VF Plus, four seats), the African Independent Congress (AIC, three seats), the Pan African Congress (PAC, one seat), and the African People’s Convention (APC, one seat). The Azanian People’s Organisation (AZAPO), the United Christian Democratic Party (UCPC) and the Minority Front (MF) all lost their seats in the National Assembly due to their failure to meet the minimum vote threshold. Municipal elections will take place in 2016.

The world economy is experiencing a lengthy period of low growth. Growth in developing economies has moderated in response to lower commodity prices, subdued domestic demand and reduced capital inflows. Growth in some developed economies has offset this slowdown. The South African government has taken two key steps to adapt to this low-growth world. It has identified the broad structural reforms needed to put the economy on a much higher growth path and it has sought to reduce South Africa’s vulnerability by implementing fiscal policy measures to maintain the health of the public finances.

The Government’s economic agenda is based on the principle that prudent macroeconomic policies provide an important anchor for stability in today’s turbulent global environment. Sustainable fiscal policy protects the social gains made since 1994. A resilient, flexible financial system helps the economy adjust to rapid change. The National Development Plan (NDP) lays the basis for much-needed economic and policy reforms to establish a platform for faster growth. Creating work and improving education to eliminate poverty and build a more equitable society are at the heart of long-term reforms set out in the NDP.

Nevertheless, economic conditions remained challenging for South Africa. The 2015 MTBPS estimates that South Africa’s economic performance has deteriorated over the past several years. Electricity constraints, weak business confidence and low household demand have limited growth. GDP is expected to grow by 1.5% in 2015, same as in 2014, rising marginally to 1.7% in 2016 and 2.6% in 2017.

5

Electricity supply is expected to constrain growth through 2016 by limiting output and dampening business and consumer confidence. Goverment’s plan to reduce electricity shortages has made progress, with the first unit of Eskom Medupi power station commencing operations, adding 800 MW of energy to the national grid. Government has sought to stabilize Eskom’s financial position with an R23 billion equity investment financed from the sale of Vodacom shares.

Given the weak economic outlook, proposals for additional taxes—which are essential to fund government’s ambition policy agendas—will be approached with caution. Over the medium term, the Government expects to continue to explore reforms that promote an efficient and progressive tax system, taking into account the recommendations of the Davis Tax Committee that was established in July 2013. The committee has published reports on small business taxation, value-added tax (VAT), base erosion and profit shifting, estate duty and mining taxation. A report on the role of the tax system in supporting inclusive growth, employment, equity and fiscal sustainability has also been published.

Despite weak economic growth over the past five years, revenue collection has consistently outpaced economic expansion. While nominal GDP growth has averaged 8.6% over the past five years, tax revenue has averaged 10.5% growth during the same period. Gross tax revenue for 2014/15 came in R7.3 billion above projections in the 2015 budget but has been revised downward by R7.6 billion in 2015/16. The downward revision was attributed to the weak performance of corporate income tax collections due to the steep decline in commodity prices and slowdown in economic activity. In total, lower growth has resulted in a downward revision of R35 billion to gross tax revenue projections between 2015/16 and 2017/18.

Domestic inflation is lower, largely as a result of declining oil prices. The Rand’s depreciation, however, poses some risk to the inflation outlook. Consumer price index (CPI) inflation eased to 4.6% over the first eight months of 2015, from 6.1% in 2014. Core inflation, which represents the long-run trend of the price levels and excludes temporary shocks, was unchanged at 5.7% over the same period.

Government is maintaining the fiscal course that was announced in 2014/15. Spending limits will remain in place to support sustainable public finances that are not overburdened by debt and interest payments. The ratio of government debt to GDP is expected to stabilize. The main budget deficit is projected to stabilize at 3.5% of GDP over the medium term, with the consolidated deficit declining to 3%. The expenditure ceiling set in the 2015 budget remains in place. Spending pressure, including higher wage bill, have been accommodated within the contingency reserves and departmental baselines.

6

In the three months ended September 30, 2015, quarterly changes reflected an increase in the number of people employed (by 171,000 to 15,828,000) and an increase in unemployment (by 188,000 to 5,418,000). This resulted in a slight increase in the unemployment rate from 25.0% in the three months ended June 30, 2015 to 25.5% in the three months ended September 30, 2015. Increases in non-agricultural employment were observed in both the formal and informal sectors (10,930,000 and 2,721,000, respectively). Employment increased by 28,000 people in the agricultural sector, while a decrease of 110,000 was observed in private households. The quarterly decrease of 200,000 among the economically inactive population was driven by an increase in discouraged job-seekers (208,000).

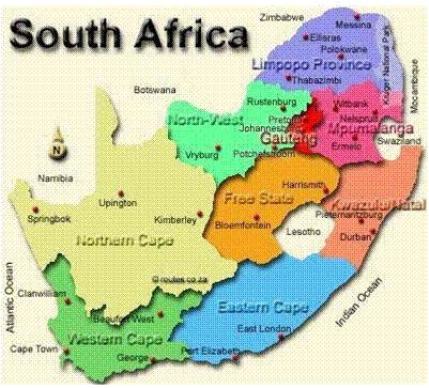

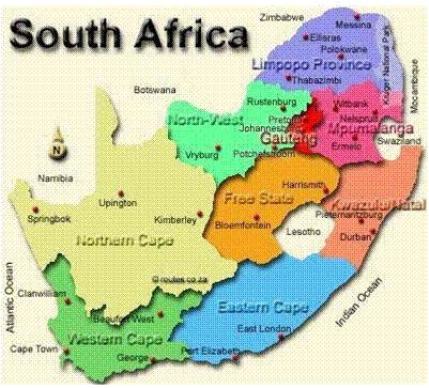

MAP OF THE REPUBLIC OF SOUTH AFRICA

REPUBLIC OF SOUTH AFRICA

Area and Population

South Africa is situated on the southern tip of the African continent, with the Atlantic Ocean to the west and the Indian Ocean to the east. The north of the country shares common borders with Namibia, Botswana and Zimbabwe and, to the north east, the country shares a border with Mozambique. South Africa also shares common borders with the kingdoms of Lesotho and Swaziland. The total surface area of South Africa is approximately 1,219,090 square kilometers, with over 3,000 kilometers of coastline.

7

South Africa comprises nine provinces, which are the Eastern Cape, Free State, Gauteng, KwaZulu-Natal, Limpopo, Mpumalanga, Northern Cape, North West and Western Cape Provinces.

In the former racial classification that formed the basis for the apartheid system, “Black” referred to persons of original African indigenous origin, “Asian” to persons of Asian origin, “White” to persons of Caucasian ethnic origin and “Colored” to persons of mixed race. While the National Government no longer makes any unfair discrimination based on race, the country’s history of racial division and racial and ethnic differences continues to have social and economic significance. This is because social and economic policies are judged partly by their ability to address disparities and discrimination and to equalize opportunities. Therefore, in this document, reference to such racially classified statistics is made occasionally to illustrate those disparities.

South Africa’s population is approximately 55 million as at June 30, 2015, of which 28.1 million, representing 51% of the population, are female. Approximately 80.5 % are African, 8.8% are Colored, 2.5% are Indian/Asian and 8.3% are White (source: Stats SA Mid-year population estimate 2015). The most densely populated parts of South Africa are the four major industrialized areas: the Pretoria/Witwatersrand/Vereeniging area of Gauteng (which includes Johannesburg), the Durban/Pinetown/Pietermaritzburg area of KwaZulu-Natal, the Cape Peninsula area of the Western Cape (which includes Cape Town) and the Port Elizabeth/Uitenhage area of the Eastern Cape.

Stats SA estimates the average life expectancy in South Africa for females to be 72.7 years, and for males to be 65.2 years. However, it should be noted that life expectation estimates vary, primarily due to differences in assumptions about the rapidity with which the HIV epidemic will spread and the morbidity and mortality of the disease (see “— Public Health — HIV, AIDS and Tuberculosis (TB)”).

South Africa has a diverse population consisting of Afrikaans and English-speaking Whites, Asians (including Indians), Coloreds, Khoi, Nguni, San, Sotho-Tswana, Tsonga, Venda and persons that have immigrated to South Africa from across the globe. By virtue of the country’s diversity, South Africa has 11 official languages, namely Afrikaans, English, isiNdebele, isiXhosa, isiZulu, Sepedi, Sesotho, Setswana, siSwati, Tshivenda and Xitsonga. According to the results of the census conducted in 2011, isiZulu is the mother tongue of 22.6% of the population, followed by isiXhosa at 15.9%, Sepedi at 9.1%, Afrikaans at 7.9%, and English and Setswana at 8.2% each. IsiNdebele is the least spoken language in South Africa, at 1.5% (source: Census 2011).

Government and Political Parties

Constitution

Following the repeal of apartheid legislation, South Africa held its first fully democratic national election in 1994. The final Constitution was adopted in 1996 and phased-in between 1997 and 1999. South Africa’s Constitution is hailed as one of the most progressive in the world and enjoys high acclaim internationally. The Constitution states that South Africa is “founded on a commitment to achieve equality, to promote and protect human dignity and to advance human rights and freedoms”. The Constitution enshrines the principles of supremacy of the rule of law, universal adult suffrage, regular elections and multi-party democracy. The Bill of Rights contained in Chapter 2 of the Constitution is one of the world’s broadest, guaranteeing freedom of speech, movement and political activity, and providing persons accused of crimes with many legal protections including the right to a speedy trial and the right to remain silent. The Bill of Rights also enshrines the right to access to adequate housing, food, water, education and healthcare, and prohibits discrimination on the basis of race, gender, sexual orientation, age, pregnancy or marital status.

The Constitution provides for the separation of powers among the legislative, executive and judicial branches of the National Government. Under the Constitution, the bicameral Parliament, in which the legislative authority of the National Government is vested, is comprised of a National Assembly and a National Council of Provinces.

8

The National Assembly consists of no fewer than 350 and no more than 400 members elected on the basis of proportional representation pursuant to which political parties receive seats in proportion to the votes cast for the parties concerned. Of the 400 seats in the National Assembly, approximately 200 seats are selected from provincial lists, with a fixed number allocated to each province. The remaining seats are filled from national lists to ensure proportionality in accordance with the total number of votes cast for each party in the national election.

The National Council of Provinces consists of 90 members (namely 54 permanent members and 36 special delegates). Each of the nine provincial legislatures elects ten representatives.

The Constitution provides for national elections every five years and places all elections and referendums in the country for all three spheres of government (national, provincial and local) under the control of the Independent Electoral Commission (IEC). The most recent national and provincial elections were held in May 2014 and municipal elections will take place in 2016.

Each province has its own executive authority, the premier. The premiers are elected by each Provincial legislature from among its members. The powers of the premier are exercised in consultation with a provincial executive council, which is constituted in a manner similar to the Cabinet in the National Government. The provinces exercise limited power on a national level, principally through their representatives in the National Council of Provinces, and also through their power to block Parliamentary action affecting the constitutional position and status of the provinces.

Political Parties

The ANC, which was founded in 1912 and which led the struggle against apartheid, is the ruling party in eight of the nine South African provinces, and the most influential party in South Africa in terms of the size of its electoral constituency support. Following the May 2014 elections, the ANC occupies 249 of the National Assembly’s 400 seats. Every five years the ANC holds a National Conference, which is its highest decision-making body and which decides the policies of the ANC, adopts proposed constitutional amendments and elects the National Executive Committee. At its 53rd National Conference, held in Mangaung, Free State Province from December 16-20, 2012, the ANC re-elected the current President of South Africa, Jacob Zuma, as president of the ANC, and Cyril Ramaphosa as his deputy. The 80-member National Executive Committee, which is the party’s highest decision-making body between conferences, was also elected at the National Conference.

The ANC Youth League (ANCYL), under the former leadership of Julius Malema and its principal spokesperson, Floyd Shivambu, made a number of public statements calling for the nationalization of mines and mining assets. The ANCYL also advocated for the nationalization of banks and the expropriation of agricultural land without compensation. Various ANC officials responded by stating that nationalization is neither government nor ANC policy.

Mr. Malema was suspended from the ANC for five years in November 2011 after the disciplinary committee found him guilty of bringing the party into disrepute and sowing division in the party ranks.

Consequently, Mr. Malema launched the Economic Freedom Fighters (EFF) party in 2013 with himself as its leader. The launch of the EFF marked the second launch of a new political party during 2013. In February 2013, former World Bank Managing Director and anti-apartheid activist Dr. Mamphela Ramphele announced the launch of Agang SA. In the May 2014 elections, the EFF won 25 seats in the National Assembly, while Agang SA won two seats.

9

The Democratic Alliance (DA), founded in 2000 and currently led by Mmusi Maimane, serves as the official opposition in the National Assembly. In the 2009 elections, the DA won 67 of the 400 seats in the National Assembly, and following the 2014 national and provincial elections, now holds 89 seats.

On August 15, 2010, the DA and the Independent Democrats announced that the two parties had ratified a memorandum of understanding, paving the way for complete integration by 2014. The memorandum of understanding made provision for Independent Democrat members of the National Assembly and Provincial Legislatures to hold dual membership until the next national and provincial elections in 2014. As of the May 2014 elections, all remaining dual members of the Independent Democrats became members of the DA as per the memorandum of understanding.

On November 10, 2008, a faction of the ANC broke away from the party and launched a new political party, called the Congress of the People (COPE), led by former ANC chief whip and Defence Minister Mosiuoa Lekota and former Gauteng Premier Mbhazima Shilowa. COPE won 30 seats in the National Assembly following the April 2009 elections. Since then, there has been a protracted leadership dispute between Mr Lekota and Mr Shilowa. The South Gauteng High Court validated Mr Lekota as the rightful head of COPE in a ruling handed down in October 2013, however, Mr Shilowa has indicated that he is likely to continue to challenge for a position within COPE through the courts. COPE currently holds three seats in the National Assembly.

The Inkatha Freedom Party (IFP) was founded in 1975. In 2009, the IFP won 218 seats in the National Assembly, decreasing to ten seats in May 2014 elections. In the May 2011 municipal elections, the IFP was unable to lodge the required documentation in time to contest the local government election in Umzumbe, an IFP stronghold. This culminated in an urgent application to the Constitutional Court, the result of which was an affirmation by the Constitutional Court of the Electoral Commission’s view that the IFP could not contest the election in Umzumbe. The current leader of the IFP is Chief Mangosuthu Buthelezi.

Following the May 2014 elections, a number of minority parties make up the balance of the seats presently held in the National Assembly, including the National Freedom Party (NFP, six seats), United Democratic Movement (UDM, four seats), the Freedom Front Plus (VF Plus, four seats), the African Independent Congress (AIC, three seats), the Pan African Congress (PAC, one seat), and the African Peoples Convention (APC, one seat). the Azanian People’s Organisation (AZAPO), The United Christian Democratic Party (UCPC) and the Minority Front (MF) all lost their seats in the National Assembly due to their failure to meet the minimum threshold in votes.

Presidential Developments

Following the June 1999 elections, Thabo Mbeki of the ANC succeeded Nelson Mandela as President and continued to serve as President following the 2004 elections. Phumzile Mlambo-Ngcuka, who had been serving in the Cabinet as Minister of Minerals and Energy, was appointed as the first female Deputy President of South Africa in July 2005, replacing Deputy President Jacob Zuma who was released from his duties by the then President Thabo Mbeki following allegations of corruption. On September 20, 2006, the charges of corruption against Jacob Zuma were struck from the court roll because the state was not ready to proceed with its case. The National Prosecuting Authority (NPA) attempted to recharge Jacob Zuma, but the Pietermaritzburg High Court ruled on September 12, 2008 that the decision to prosecute Jacob Zuma on corruption, racketeering and tax evasion charges was procedurally invalid.

In September 2008, the ANC recalled Thabo Mbeki from office before his term expired. The ANC stated that the decision had been made in light of a High Court judgment which suggested executive meddling in the decision to prosecute Jacob Zuma. On September 21, 2008 Thabo Mbeki tendered his resignation, which became effective on September 25, 2008.

Following Thabo Mbeki’s resignation, the National Assembly voted by secret ballot to determine which of two nominees (that of the ANC and that of the DA) would fill the vacant office of president. Kgalema Motlanthe, of the ANC, captured the majority of the votes and was sworn in as South Africa’s President on September 25, 2008, with Baleka Mbete, also of the ANC, appointed as his deputy. On May 9, 2009 Jacob Zuma was inaugurated as President, with Kgalema Motlanthe as his deputy.

10

On January 12, 2009, the Supreme Court of Appeal (SCA) held that the Pietermaritzburg High Court had erred in its ruling regarding the declaration that the decision of the NPA to prosecute Jacob Zuma was invalid. The matter was taken on appeal to the Constitutional Court and was set to be heard on May 12, 2009, however, on April 6, 2009, the NPA announced that it had dropped the corruption charges against Jacob Zuma, citing political interference in the legal process. The circumstances surrounding the NPA’s decision to drop the charges have been called into question by the DA and political action groups including Freedom Under the Law, and a court challenge was brought requiring the release by the NPA of records relating to the decision. A review application was filed by the DA, and in 2015, the NPA filed its papers arguing that President Zuma was charged with corruption almost immediately after being elected as ANC leader, in order to stop then President Thabo Mbeki from being recalled. The matter has not proceeded further since then.

During 2013, Public Protector Thuli Madonsela conducted an investigation into a more than R200 million security upgrade of President Zuma’s home in Nkandla, KwaZulu-Natal. The Public Protector released the conclusions of the investigation in a report dated March 19, 2014. Amongst the Public Protector’s findings was that certain of the upgrades installed by the Department of Public Works in the President’s Nkandla home resulted in an unlawful misappropriation of public funds. The report directed the President to submit comments to the report to the National Assembly within 14 days and the President responded on April 2, 2014 that he had directed the Special Investigating Unit to examine the security upgrades and would make a further report to the National Assembly following conclusion of the Special Investigating Unit’s probe. The President has since commented on the Public Protector’s report and the Special Investigating Unit has finalized its report. The National Assembly convened an ad hoc committee to consider the Public Protector’s report as well as all other reports on Nkandla. The ad hoc committee released its findings on November 13, 2014. The report absolved President Zuma from responsibility for the abuse of funds on his Nkandla home and left it to the Cabinet to rule whether refurbishments at Nkandla were legitimate security measures, and to the President to decide who should be held responsible for excesses. The President tasked the Minister of Police, Mr. Nkosinathi Nhleko, with the task of investigating who should be held responsible for repayment of the money spent on President Zuma’s Nkandla home. In May 2015, Minister Nhleko released his report which found that the President did not have to repay money for the upgrades at his home because all the features, including the swimming pool, were for the President’s security. The report was submitted for tabling in Parliament. Parliament set up an ad hoc committee to consider Minister Nhleko’s report. The ad hoc committee endorsed Minister Nhleko’s finding and its report was tabled in Parliament in August 2015 when it was adopted.

On October 8, 2015, the Supreme Court of Appeal (SCA) handed down a significant judgment relating to the powers of the Public Protector. The judgment was in an appeal by the South African Broadcast Corporation (SABC), the Minister of Communications and, the Chief Operating Officer of the SABC, against the decision of the Western Cape High Court to suspend the Chief Operating Officer of the SABC. The main issue addressed in the judgment was whether recommendations by the Public Protector have to be implemented. The court held that, as the primary watchdog of the Government, the recommendations of the Public Protector have to be implemented because if the recommendations are ignored, it strips the office of all power. The SCA held that only a court can review the findings and recommendations of the Public Protector. The same issue will be considered by the Constitutional Court on February 9, 2016, when it will decide on the application by the EFF to force President Jacob Zuma to comply with the recommendation by the Public Protector to repay the public funds spent on his Nkandla homestead.

2014 National and Provincial Elections

In May 2014, approximately 25 million South Africans registered to vote in the national and provincial elections, compared to the approximately 23 million people registered to vote in April 2009.

The IEC approved the candidate lists of 42 political parties that contested the national and provincial elections. Of these parties, 29 political parties were registered to contest the national election for the National Assembly. 13 political parties were registered to contest all nine provincial legislatures, 29 political parties applied to contest only some provinces.

11

According to IEC data, a total of 18 million South Africans cast their votes in the elections on May 7, 2014. The May 2014 elections were considered fair, transparent and credible by the IEC. The official general election results were announced on May 10, 2014. The ruling ANC won the elections, receiving 62% of the votes cast in respect of the national elections. The DA remained the official opposition of the ANC, with 22% of the votes, and the EFF came in third with 6% of the votes.

The table below sets out the National and Provincial Assembly seats secured by political parties following the May 2014 general elections.

| | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | |

| | | Number of seats in

National Assembly | | | Proportional

Representation seats | |

Political Party | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | |

ANC | | | 249 | | | | 62.15 | % | | | 118 | | | | 59.0 | % |

DA | | | 89 | | | | 22.23 | % | | | 45 | | | | 22.5 | % |

EFF | | | 25 | | | | 6.35 | % | | | 11 | | | | 5.5 | % |

IFP | | | 10 | | | | 2.4 | % | | | 5 | | | | 2.5 | % |

NFP | | | 6 | | | | 1.57 | % | | | 3 | | | | 1.5 | % |

UDM | | | 4 | | | | 1 | % | | | 2 | | | | 1.0 | % |

VF PLUS | | | 4 | | | | 0.9 | % | | | 3 | | | | 1.5 | % |

COPE | | | 3 | | | | 0.67 | % | | | 3 | | | | 1.5 | % |

ACDP | | | 3 | | | | 0.57 | % | | | 3 | | | | 1.5 | % |

AIC | | | 3 | | | | 0.53 | % | | | 3 | | | | 1.5 | % |

AGANG SA | | | 2 | | | | 0.28 | % | | | 2 | | | | 1.0 | % |

PAC | | | 1 | | | | 0.21 | % | | | 1 | | | | 0.5 | % |

APC | | | 1 | | | | 0.17 | % | | | 1 | | | | 0.5 | % |

| | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | |

Total | | | 400 | | | | 100.0 | % | | | 200 | | | | 100.0 | % |

| | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | |

Source: IEC.

On May 24, 2014, following the ANC’s victory in the elections, Jacob Zuma was inaugurated as the fourth democratically elected President of the Republic, with Cyril Ramaphosa as his deputy.

2011 Municipal Elections

Municipal elections are held every five years. The 2011 municipal elections were held on May 18, 2011 at which 13.66 million South Africans voted. This was the highest voter turnout since the first municipal elections following the reorganization of municipalities in 2000. Before the 2011 elections, the ANC had control of a majority of municipalities in each province, including the Western Cape Province. In the 2011 elections, the DA won a majority (57.08%) of the votes in the Western Cape Province. In the Nelson Mandela Bay municipality, the ANC also obtained a majority of votes. Although the DA increased its presence in the Northern Cape (to 22.27%), the ANC won control of the province as a whole (at 63.57%).

COPE, the NFP and the IFP also tried to improve their standings but failed to obtain control of any municipalities. Various smaller parties contested the elections, but made no significant impact.

The end results of the 2011 municipal elections were that, of 35,235,914 votes cast, the ANC won 63.65% of the votes, the DA won 21.97%, the IFP won 3.94%, the NFP won 2.58% and COPE won 2.33%. Each of the remaining parties contesting the elections obtained results below 1%.

Zuma Administration

The Constitution provides for a Cabinet consisting predominantly of members of the National Assembly, who retain their seats while in the Cabinet. Cabinet portfolios are allocated by the President. The Cabinet generally operates by consensus rather than by voting.

12

On May 25, 2014, President Zuma announced his Cabinet, which consisted of 35 ministers who are members of Parliament, in addition to the President and the Deputy President, as well as some structural changes to the National Government. Some departments were split, others combined and new departments were created. President Zuma also announced that the National Planning Commission (NPC) as well as the Performance Monitoring and Evaluation Ministries in the Presidency had been combined into one Ministry to harmonize the planning and monitoring functions. On March 15, 2015, Mr. Collins Chabane, the Minister of Public Service & Administration, passed away in a motor vehicle collision, and Nathi Mthethwa, the Minister of Arts and Culture, was appointed as the Acting Minister of Public Service & Administration. On September 22, 2015, President Zuma announced a reshuffle of the Cabinet in order to permanently fill the position of Minister of Public Service & Administration. The following replacements were made:

| | • | | Public Service and Administration Minister, Mr. Collins Chabane, was replaced by the former Minister of Mineral Resources, Ngoako Ramatlhodi. |

| | • | | Mineral Resources Minister, Mr. Ramatlhodi was replaced by Mr. Mosebenzi Zwane, former MEC for economic, small business development and environmental affairs of the Free State province. |

The NPC released a diagnostic report on June 9, 2011 that aims to identify the main challenges confronting the country and to examine the underlying causes of such problems. The diagnostic report is not a plan; it provides the basis for a plan.

The diagnostic report covers the following topics:

| | • | | institutions and governance. |

On November 11, 2011, the NPC released its vision statement for 2030 (Vision 2030), as well as a National Development Plan (NDP 2030) for the Cabinet’s consideration. The NDP 2030 focuses on key priority areas and identifies nine primary challenges: high unemployment, poor education outcomes, a high disease burden, divided communities, uneven public service performance, settlement patterns that marginalize the poor, corruption, an overly resource-intensive economy and crumbling infrastructure.

The key areas of focus for the NDP 2030 are:

| | • | | enhanced capabilities and an active citizenry; |

| | • | | growth, investment and employment; |

| | • | | rising standards of education and a healthy population; |

| | • | | an effective and capable government; |

| | • | | collaborations between the private and public sectors; and |

| | • | | leadership from all sectors of society. |

13

Legal System

The South African legal system is based upon Roman-Dutch law and incorporates certain elements of English law, subject to the Bill of Rights contained in the Constitution. Judicial authority in South Africa is vested in the courts, which are established pursuant to the Constitution. The Constitution is the supreme law of the land and no other law can supersede the provisions of the Constitution. The Constitutional Court has jurisdiction as the court of final instance over all matters relating to the interpretation, protection and enforcement of the terms of the Constitution and is the court of first instance on matters such as those concerning the constitutionality of an Act of Parliament referred to it by a member of the National Assembly. Decisions of the Constitutional Court are binding upon all persons and upon all legislative, executive and judicial organs of state. Matters not falling within the jurisdiction of the Constitutional Court fall within the jurisdiction of the Supreme Court, which consists of the Supreme Court of Appeal and various High Courts. Judgments of the Supreme Court of Appeal are binding on all courts of a lower order, including the High Courts, and judgments of the High Courts are binding on the lower courts within their respective areas of jurisdiction.

The Chief Justice and the Deputy Chief Justice of the Constitutional Court are appointed by the President in consultation with the Judicial Service Commission (JSC) and the leaders of parties represented in the National Assembly. The Judge President and Deputy President of the Supreme Court of Appeal are appointed by the President after consulting with the JSC only. The remaining judges of the Constitutional Court, the Supreme Court of Appeal and the High Courts are appointed by the President on the advice of the JSC.

Former Chief Justice Sandile Ngcobo retired on August 12, 2011 and was replaced by the new Chief Justice, Mogoeng Mogoeng, on September 8, 2011. Prior to his retirement, President Zuma had extended Chief Justice Ngcobo’s term of office. However, this decision was declared unconstitutional by the Constitutional Court, which held that the section of the Judges’ Remuneration and Conditions of Employment Act, which the President relied on to extend the term of office, was unconstitutional. The appointment of Mogoeng Mogoeng to the position of Chief Justice ahead of Deputy Chief Justice Dikgang Moseneke was controversial and prompted public scrutiny of the JSC and the consultation process. Chief Justice Mogoeng Mogoeng’s appointment was confirmed after an intensive two-day televised interview before the JSC, chaired by Deputy Chief Justice Moseneke.

Broad-Based Black Economic Empowerment

Broad-Based Black Economic Empowerment (BBBEE) is a core tenet of the National Government’s initiative to address the economic exclusion of historically disadvantaged South Africans by encouraging the redistribution of wealth and opportunities to historically disadvantaged persons. As part of this initiative, the National Government enacted the Broad-Based Black Economic Empowerment Act, 2003 (Act No. 53 of 2003) (BBBEE Act), which came into effect in April 2004. For purposes of the BBBEE Act, “black people” is a generic term which means Africans, coloreds and Indians. On June 18, 2008, the High Court of South Africa ordered that South African Chinese persons (who are South African citizens or would have obtained citizenship but for the previously applicable discriminatory laws) be included within the ambit of the BBBEE Act. The BBBEE Act aims to facilitate BBBEE and promote economic transformation by: incentivizing meaningful participation by black people in the economy; changing the racial composition of ownership and management structures in enterprises; promoting investment programmes that lead to BBBEE; enabling access to economic activities, infrastructure and skills for black women and rural and local communities; increasing the extent to which workers, communities and cooperatives own and manage enterprises; and promoting access to finance for black economic empowerment (BEE).

In 2013, amendments to the BBBEE Act were introduced. These, together with the Codes change the current BBBEE framework and are the result of the Government’s intention to promote and implement BBBEE. Government policy has to date been based on the principle that the manner in which a firm applies BBBEE is to be decided by the individual firm having regard to its own business needs with the BBBEE framework providing a methodology for measuring the BBBEE rating of the firm. The new BBBEE framework introduces penalties in certain circumstances, which is an important departure from previous Government policy.

The Department of Trade and Industry (DTI), empowered by the BBBEE Act, has issued the BBBEE Codes of Good Practice on Black Economic Empowerment (the Codes). The Codes, which were promulgated in February 2007, require that every organ of national and local government and every public entity must, as far as is reasonably possible, apply best BEE practices in issuing licenses, implementing procurement policies, determining qualification criteria for the sale of state-owned enterprises and

14

developing criteria for entering into public private partnerships. The Codes set out general principles for measuring ownership and management control, preferential procurement, employment equity, skills development, enterprise development and socio-economic development, including special guidance for qualifying small enterprises. The Codes also provide guidance on fronting practices, BEE verification, the recognition of contributions toward BEE of multinationals, and the treatment of public entities and other enterprises wholly-owned by organs of state. The Codes are subject to review by the Minister of Finance in 2017.

Multinational Companies

The Codes have given multinational companies flexibility in the manner in which they can implement the Codes, should they wish to do so. A multinational company trading in South Africa can retain sole ownership of its South African subsidiary, provided that alternative measures to broaden economic participation by black people, in terms of the Codes, are exercised. This retention of ownership by a multinational over its South African subsidiary can be achieved by implementation of “equity equivalent” programs which must be pre-approved by the Minister of the DTI as well as the ministry of the industry in which the relevant multinational enterprise operates. Such equity equivalent programs focus on skills transfer, empowerment of SMME businesses and broader socio-economic empowerment projects.

Public Entities and State Agencies

The BBBEE Act places a legal obligation on state agencies to contribute to BBBEE, including when developing and implementing their preferential procurement policies. The Preferential Procurement Policy Framework Act, 2000 (Act No. 5 of 2000) (PPPFA) was promulgated as a result of Section 217 of the Constitution, which states that all spheres of government must have a mechanism in place that would bring about categories of preference in allocation of contracts when procuring goods and services to advance historically disadvantaged individuals (HDIs). In December 2006, when the Codes were approved for gazetting, Cabinet gave the DTI and the National Treasury a mandate to amend the PPPFA to advance the objectives of the BBBEE Act. The draft amended PPPFA was gazetted for public comment on August 20, 2009. On June 8, 2011, the Minister of Finance gazetted new regulations in terms of the PPPFA which became applicable to all organs of state and public entities as of December 7, 2011, except selected “major public entities” and certain national and provincial government business enterprises set out in the Public Finance Management Act, 1999 (Act No. 1 of 1999) (PFMA), which are exempted until December 7, 2012. In terms of the new regulations, the BBBEE contributorship level of an enterprise (calculated with reference to the Codes) will account for up to 20% of the scorecard in respect of all tenders valued between R30,000 and R1,000,000 and up to 10% of the scorecard in respect of tenders exceeding R1,000,000.

Private Sector

Although the BBBEE Act and Codes do not impose legal obligations on firms to comply with BBBEE targets, a firm’s BBBEE status is an important factor affecting its ability to successfully tender for Government and public entity tenders and (in certain sectors like mining and gaming) to obtain licenses. The amendments introduced in 2013 impose penalties in certain circumstances. Private sector clients also increasingly require their suppliers to have a minimum BBBEE rating in order to boost their own BBBEE ratings. BBBEE is accordingly an important factor to be taken into account by any firm conducting business in South Africa.

The BBBEE Act provides for the DTI to publish and promote any transformation charter (for later development into industry codes) for a particular sector of the economy, provided that charter (or code) is developed by the major stakeholders in that sector and advances the objectives of the BBBEE Act. These charters/codes set out a blueprint and timeline for the transformation of the relevant economic sectors. Examples include the Agri-BEE Charter, the Marketing, Advertising and Communication Sector Charter, the Integrated Transport Sector Codes, the Forest Sector Code, the Construction Sector Code, the Tourism Sector Code, the Chartered Accountancy Sector Code, the Property Sector Charter and the Information and Communication Technology (ICT) Code. Other charters are being developed and draft versions thereof have been released, including the draft Financial Sector Code.

Some of the biggest challenges facing the National Government in relation to the implementation of BBBEE include educating the South African public on the objectives, opportunities and perceptions relating to BBBEE, providing certainty as to the requirements of BBBEE, ensuring that the objectives of BBBEE are properly adhered to and encouraging investment in South Africa that advances BBBEE and promotes economic and social transformation.

15

Land Reform

Land reform in South Africa is a complex issue, due to both the apartheid era legacy of dispossessing black South Africans of their land and to the current development challenges. Through the judicial framework process and the Constitution’s protection of private property rights, the National Government seeks to facilitate the equitable transfer of land to South Africans who were previously dispossessed of their land as a result of the land dispossession policies of the previous regime in South Africa.

The White Paper on Land Affairs of 1997 is a land reform strategy that focuses on restitution, redistribution and land tenure reform. Restitution involves either returning land or providing alternative compensation to persons who have been dispossessed of their land; redistribution encourages the acquisition of land by disadvantaged South Africans (with the aid of government grants); and land tenure reform aims to create a unified and secure system of landholding.

The Department of Rural Development and Land Reform had previously set 2014 as the deadline for achieving land reform in South Africa through the redistribution of 30% of white-owned commercial agricultural land to those previously dispossessed of such land. Section 25 of the Constitution provides that property may only be expropriated subject to compensation that is either agreed by those affected or decided or approved by a court. The National Government has been committed to executing its land reform strategy to uphold this constitutional principle.

In June 2007, the National Policy Conference of the ANC resolved that it was necessary to develop a detailed strategy in order to meet the 30% target. Pursuant to this, the Department of Public Works released a policy document on the expropriation of land and other property in the public interest or for public purposes. The policy document had two main objectives: (1) to enable the state to use expropriation as a means to affect land reform and (2) to align the Expropriation Act of 1975 with the Constitution. To achieve these goals, the Expropriation Bill was presented before Parliament on April 11, 2008, and was published for public comment after certification of the bill. On August 27, 2008, the Portfolio Committee on Public Works withdrew the bill until further notice, stating that more time was needed to ensure consultation with a wide variety of stakeholders. The National Government abandoned the 30% target in 2013. The focus is now on ensuring that all land reform farms are 100% productive. According to the Department of Rural Development and Land Reform, approximately 7.4 million hectares of land have been transferred to disadvantaged South Africans under the restitution and redistribution program; the initial 30% target was 24.6 million hectares.

The implementation of the land restitution and land reform programs are supported through allocations to the Department. Expenditure grew from R8.9 billion in 2012 to R9.5 billion in 2014, mainly due to the increase in land reform and restitution grants, and is expected to increase to R11.5 billion by 2019. The Commission on Restitution of Land Rights has developed a strategic plan to finalize the remaining claims that addresses issues such as price negotiation, untraceable claimants, disputes and jurisdiction. A total of 9,149 claims from the first round of restitution, which ended in 1998, remain unsettled. The Department of Rural Development and Land Reform is in the process of verifying all outstanding claims. The department provided R36 million for 2015/2016, 2016/17 and 2017/18 for the establishment of a Valuer-General office which establishes prices for the farms redistributed as part of the land reform. The Restitution of Land Rights Amendment Act of 2014 extends the lodgment of land claims for five years, from July 1, 2014 to June 30, 2019.

In response to the slow pace of land redistribution, many commercial farmers and farming organizations have elected to drive reform themselves by establishing transformation programs, which aim to preserve and enhance agricultural productivity. A partnership between government, farming organizations, communities, financiers and experts is required as promoted by the 50/50 policy under which farm workers own 50% of the farms.

16

The National Government is also currently investigating policy options with regards to foreign ownership of South African land and its effect on the National Government’s ability to meet its Constitutional duties to effectively deliver on land reform. The policy options recommend that where land has been earmarked for reform, restitution or integrated human settlement, National Government approval is required for the sale of that land to foreign nationals.

Significant strides have been made in the area of land reform:

| | • | | as at March 31, 2015, 1,459 farms had been recapitalized; |

| | • | | the Department of Rural Development and Land Reform employed 15,781 youths under the National Rural Youth Services Corps program. |

Mining Industry Reform

Mining in South Africa has historically been undertaken largely by the private sector. As of January 2014, there were 1,699 registered mines and quarries in South Africa. The most important mining houses in South Africa include Anglo American plc, De Beers Corporation, African Mineral Limited, BHP Billiton SA, Gold Fields Limited, Impala Platinum Holdings Limited, Lonmin plc, Kumba Iron Ore Limited, Exxaro Limited, Xstrata plc and Harmony Gold Limited. These corporations, together with their affiliates, are responsible for the majority of the gold, diamond, uranium, zinc, lead, platinum, chrome, iron ore, coal and silver production in South Africa.

| | • | | Gross fixed capital formation in the mining industry increased significantly under the Mineral and Petroleum Resources Development Act No 28 of 2002 (MPRDA), from R18 billion in 2004 to R79 billion in 2013 (source: South African Reserve Bank). |

| | • | | Foreign direct investment in the mining industry grew considerably, from R112 billion in 2004 to R429 billion in 2012 (source: South African Reserve Bank). |

| | • | | Employment in the mining industry grew from 448,909 in 2004 to 495,000 in 2014. |

| | • | | Mining contribution to GDP decreased from R245 billion in 2004 to R225 billion in 2014. |

The Mineral and Petroleum Resources Development Act (MPRDA) and the Mining Charter

The National Government enacted the MPRDA in 2002. The MPRDA, which came into effect on May 1, 2004, together with the implementation of the Broad-Based Socio-Economic Empowerment Charter for the South African Mining Industry published on August 13, 2004 (the Mining Charter), recognizes the state’s sovereignty and custodianship over the country’s mineral resources. The MPRDA also provides for equitable access to mineral resources, expansion of opportunities for HDIs (including women-led entities) and promotes economic growth, employment and socio-economic welfare, and security of tenure. The Department of Mineral Resources (DMR), which is responsible for administering the MPRDA, is currently in the advanced stage of reviewing the MPRDA with a view to streamlining mining regulation in South Africa to optimize the contribution of the sector to national development priorities such as energy security and beneficiation and providing further clarity around such issues as the transfer, amendment, suspension and partitioning of rights. Among other things, the MPRDA Amendments Bill aims “to provide for the regulation of associated minerals, partitioning of rights and enhanced provisions relating to the regulation of the mining industry through beneficiation of minerals or mineral products.” The MPRDA amendments were tabled in Parliament in May 2013. The amendment bill was approved by the Parliamentary Portfolio Committee, the National Assembly and the National Council of Provinces in March 2014 and was sent back to the Parliament for consideration in January 2015. The Department received an additional R42 million over the medium term towards enforcing compliance with the MPRDA.

17

The Minister of Mineral Resources (previously the Minister of Minerals and Energy) is the competent authority for granting prospecting and mining licenses. In granting rights to HDIs, the DMR’s objective for fiscal year 2014 was to grant 200 such licenses, 101 of which have been granted as of September 30, 2014.

An online mineral resources administration system, the South African Mineral Resources Administration System (SAMRAD), was launched in April 2011 to process mining license applications, which enables the monitoring of the status and improves overall quality of license applications. The SAMRAD was further strengthened with the upgrading and rollout of software in the 2014 fiscal year, which enables the public to view spatial data and produce shapefiles making the SAMRAD more user friendly, and ensures enhancement of the spatial planning function within government.

The DMR is also responsible for managing environmental impacts from mining-related activities, and by the end of September 2014, had conducted 1,111 environmental inspections out of a target of 1,700 inspections. The Department of Environmental Affairs has transferred some of the functions of the National Environmental Management Act related to mining activities to the DMR, which means the DMR would be the competent authority for environmental impact assessments from the mines and would also be responsible for developing tools and systems for mine environmental management and reporting. The DMR is currently developing measures to streamline the licensing process relating to mining environmental issues to improve turnaround times.

The vision of the Mining Charter is to create a globally competitive mining industry that reflects a non-racial South Africa and draws on the human and financial resources of, and offers real benefits to, all South Africans. The Minister of Mineral Resources, the Chamber of Mines and the National Union of Mineworkers signed the stakeholders’ declaration on strategy for the sustainable growth and meaningful transformation of South Africa’s mining industry on June 30, 2010. The Mining Charter was reviewed after its first five years, as agreed by its signatories. The result of the review was the 2010 amendment to the Mining Charter, which reaffirmed the 2014 targets of the Mining Charter (the Revised Mining Charter).

The requirement under the Mining Charter for mining entities to achieve a 26% ownership by Historically Disadvantaged South Africans (HDSA) of mining assets by the year 2014 was retained. According to the Chamber of Mines, this target has been achieved, but conversations about broader transformations in the mining industry remain ongoing between the DMR and the Chamber. Amendments to the Mining Charter in the Revised Mining Charter include, amongst other things, the requirement by mining companies to: (i) facilitate local beneficiation of mineral commodities; (ii) procure a minimum of 40% of capital goods, 70% of services and 50% of consumer goods from HDSA suppliers by 2014 (these targets are exclusive of non-discretionary procurement expenditure); (iii) ensure that multinational suppliers of capital goods contribute a minimum of 0.5% of annual income generated from South African mining companies towards the socio-economic development of South African communities via a social development fund beginning in 2010; (iv) achieve a minimum of 40% HDSA demographic representation by 2014 at all levels of management; (v) invest up to 5% of annual payroll in essential skills development activities; and (vi) implement measures to improve housing and living standards for mineworkers by converting or upgrading mineworkers’ hostels into family units, attaining an occupancy rate of one person per room and facilitating home ownership options for all mineworkers in consultation with organized labor, all of which must be achieved by 2014. In addition, mining companies are required to monitor and evaluate their compliance to the Revised Mining Charter and must submit annual compliance reports to the DMR.

The Scorecard for the Broad-Based Socio-Economic Empowerment Charter for the South African Mining Industry attached to the Revised Mining Charter (the Scorecard) makes provision for a phased-in approach for compliance with the above targets over the five-year period ending in 2014. For measurement purposes, the Scorecard allocates various weightings to the different elements of the Revised Mining Charter. Failure to comply with the provisions of the Revised Mining Charter will amount to a breach of the MPRDA and may result in the cancellation or suspension of a mining company’s existing mining and/or prospecting rights.

18

The DMR initiated a process of evaluating the progress on the implementation of the Mining Charter during the 2014 fiscal year, the findings of which will constitute a critical input to the review process. The findings of the report were released in May 2015.

In 2008, the Mineral and Petroleum Resources Development Amendment Act was passed to do the following:

| | • | | transfer environmental regulation of mines to the Minister of Environmental Affairs and Tourism; |

| | • | | deal with challenges of implementing the MPRDA; |

| | • | | implement technical improvements to the MPRDA to improve efficiency in the management of the country’s mineral resources; |

| | • | | improve the handling of residue stockpiles and residue deposits; and |

| | • | | streamline the process of obtaining ministerial approval for cessions, transfers and encumbrances of rights aimed at promoting and protecting new entrants into the mining industry and of facilitating economic development. |

The MPRDA Amendments Bill was referred back to Parliament in January 2015 after the former Mineral Resource Minister, Ngoako Ramatlhodi, requested it, initially on the basis that the preparation of the bill through Parliament had been unconstitutional.

The MPRDA Amendment Act is yet to come into force. The DMR is currently looking at further possible amendments to the MPRDA to reinforce its objectives, to promote investment in the mining sector and to improve the system of granting rights.

A mineral beneficiation strategy was adopted by Cabinet in July 2011, focusing on five strategic value chains: iron and steel, energy commodities, jewelry fabrication, autocatalytic converters and diesel particulate filters, and pigment and titanium metal production. The purpose of the strategy is to outline a framework for the orderly development of the country’s mineral value chains, enabling South Africa to develop its mineral wealth to its full potential and to the benefit of the entire population. Its vision is to advance economic development in South Africa through the optimization of linkages in the mineral value chain, facilitate economic diversification, create jobs and promote industrialization. It aims to expedite South Africa’s move towards a knowledge-based economy and contribute to GDP growth through increased mineral value added per capita. The strategy is designed to align with South Africa’s national industrialization program and aims to create jobs in an economically diverse and environmentally sustainable manner, increase South Africa’s competitiveness and expand its industrial knowledge base.

Following the adoption of the mineral beneficiation strategy, the DMR tabled two of the five pilot value chains (iron and steel and energy) as outlined in the strategy, which were approved by Cabinet in October 2011. The DMR is working on the development of a beneficiation strategy framework which will include the five pilot value chains outlined in the beneficiation strategy. The framework outlines a set of enablers that are intended to bring about the orderly development of mineral value chains domestically and represents an opportunity for South Africa to catalyze industrialisation and contribute towards economic growth.

In 2009, the DMR published the national strategy for the management and rehabilitation of derelict and ownerless mines in South Africa, which aims to guide the management of mining legacies, with the dual purpose of rendering mines productive and environmentally safe. It proposes a course of action for the state to discharge its responsibility regarding constitutional environmental rights as contemplated in section 24 of the Constitution. The implementation of the strategy will continue, with annual updates of the

19

estimated state liability for the rehabilitation of derelict and ownerless mines being completed by actuarial scientists commissioned by the DMR. The DMR rehabilitated 28 mine sites in the period ended March 31, 2014, which contributed to the creation of 284 jobs. Job creation is a key requirement for all projects as it addresses some of the priorities of the NDP. The rehabilitation program has a positive impact on communities, resulting in economic growth through locally sourced labor and material, and improved health and wellbeing of communities. Furthermore, it reduces human and animal exposure to asbestos fibres from historical asbestos mine sites. The management and implementation of the rehabilitation of derelict and ownerless mines project received an additional allocation of R5 million in 2014/15 for 11 dangerous mine holdings that required immediate attention, bringing the total investment for this project to R89 million over the medium term. The DMR aims to rehabilitate 150 derelict and ownerless mines in the MTEF period to limit the flow of acid mine water into the environment, keeping abreast with the Government’s 2014-2019 medium-term strategic framework (MTSF) for the period for the protection and enhancement of environmental assets and natural resources.

Other Mining Industry Initiatives and Legislation

The Mineral and Petroleum Resources Royalty Act of 2008 (the Royalty Act) is aimed at ensuring that the country benefits from the exploitation of its mineral resources by imposing a resource rent on holders of rights. It also seeks to stimulate investment in the sector by addressing potential investors’ need for regulatory certainty. The Royalty Act recognizes that mineral resources are non-renewable and are part of the common heritage of all South Africans, and thus imposes a royalty on the extraction and transfer of mineral resources. The Schedules to the Royalty Act set out the classification of the mineral resources and their corresponding royalty rate. The Royalty Act was passed by the National Assembly on August 21, 2008 and the National Council of Provinces on September 23, 2008. The Royalty Act was assented to by the President on November 24, 2008 and came into force in stages between November 1, 2009 and March 1, 2010.

In addition, in 1999, the National Government launched an organization called the South African Women in Mining Association, with a focus on assisting informal mining groups in obtaining mining rights, running mining businesses and promoting female empowerment in the mining sector in accordance with the provisions of the Mining Charter. This initiative was followed by the launch in 2007 of the Youth in Energy and Mining (YEM), a program aimed at young people with an interest in the mining and energy sectors. YEM seeks to promote skills development, procurement, beneficiation enterprise development and small scale mining.

There has been an increase in the number of women participating in the mining sector since 1994. All stakeholders need to ensure that effective interventions are implemented to prevent intimidation of women in mining, whilst more attention should also be given to the health and safety of women in the sector.

The mining industry has also established the Mining Industry Growth, Development and Empowerment Task Team (MIGDETT) to help manage the negative effects of the global economic crisis and to save jobs, as well as to position the industry for growth and transformation in the medium to long term. Membership of MIGDETT includes the mining industry, the National Government, organized labor and other stakeholders.

Health and safety standards within the industry are governed by the Mine Health and Safety Act (Act 29 of 1996) (MHSA). Mining safety continues to be an area of concern as on average there are approximately 125 mine worker fatalities annually. These fatalities are partially attributable to a lack of stringent safety measures. Land slide accidents remain the largest cause of fatalities, followed by transportation and machinery accidents. During 2011, consultations took place to consider amendments to the MHSA. The proposed amendments are designed to strengthen enforcement, simplify the administrative system for the issuing of fines, reinforce offences and penalties, and remove ambiguities in certain definitions and expressions in the MHSA, and promote consistency with other laws, particularly the MPRDA. The MHSA draft amendments were tabled to Cabinet for approval for publication in the government gazette

20

and public consultation in November 2013. DMR has engaged in enhanced geoscience research and development, promoted mineral beneficiation and mine health and safety policy development and continued promotion and regulation of the diamond and precious metals industries. As part of a strategy for enhancing state participation in the mining industry, the Cabinet approved the establishment of the African Exploration Mining and Finance Corporation (AEMFC) to serve as the nucleus of a newly established state-owned mining company.

Successful implementation by the DMR of its development strategy for the mining sector requires stakeholder engagement to address current infrastructure, workforce skill development, and regulatory constraints, as well as to encourage exploration and research and development. As discussed in greater detail, below, under “The South African Economy—Mining and Quarrying”, a significant challenge for the DMR and industry stakeholders is the repairing of industrial relations following wildcat strikes initially sparked by the death of 40 mine workers during an August 2012 strike at the Lonmin mine in Marikana which then led to on and off strikes throughout parts of 2012 and 2013. The most significant strike in 2014 was the six-month strike in the platinum sector in the first half of 2014. A draft framework agreement for a sustainable mining industry was entered into by organized labour, organized business and government on June 14, 2013. The aim of the framework agreement was to promote stability in labour relations and ensure the sustainability of the mining sector. In September 2015, another mining pact was entered into between mining companies, unions and the government to limit the extent of adverse operating conditions on potential job losses going forward. In November 2015, a Mining Phakisa brought together business, labour and government to identify priorities to achieve the objectives of increasing mining exploration, investment, production, sustainability and transformation of the industry.

In September 2012, the Cabinet approved the moratorium on the acceptance and processing of applications to explore shale gas, allowing normal exploration (excluding the actual hydraulic fracturing) to proceed under the existing regulatory framework.

The approval was granted with some of the following recommendations:

| | • | | Allowing normal exploration (excluding the actual hydraulic fracturing) to proceed under the existing regulatory framework. Licensing should take into consideration the State’s developmental objectives and environmental protection requirements; |

| | • | | The augmentation of the current regulatory framework. The establishment of the appropriate regulations, controls and co-ordination systems is expected to take six to 12 months; |

| | • | | Collaboration by the Ministers of Science and Technology and of Mineral Resources in developing mechanisms for the co-existence of the astronomy research projects and the exploration for an possible extraction of shale gas in the Karoo; |

| | • | | Once all the preceding actions have been completed, the authorization of hydraulic fracturing under strict supervision of the monitoring committee. In the event of any unacceptable outcomes, the process may be halted; |

The DMR developed and published the technical regulations for shale gas development in the Government Gazette for public comments which was tabled for Cabinet approval in October 2013. The regulations place particular emphasis on unconventional extractive mechanisms for gas in the Karoo Basin and are also aimed at ensuring the developments are executed in a socially and environmentally safe manner to address concerns of communities as well as other interested and affected stakeholders. The final technical regulations, published in 2014, are intended to establish an orderly exploration of the shale gas potential in a manner that protects the water and environment and coexists with other key program of government, such as the Square Kilometer Array (SKA).

21