Via Facsimile and U.S. Mail

Christian Windsor

Special Counsel

Division of Corporation Finance

U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission

100 F Street, NE

Washington, DC 20549-7010

| Re: | Prosper Marketplace, Inc. |

| | Post-Effective Amendment No. 2 to Registration Statement on Form S-1 |

| | File No. 333-147019 (the “Registration Statement”) |

Dear Mr. Windsor:

On behalf of Prosper Marketplace, Inc., a Delaware corporation (“Prosper”), we are providing the following responses to the comment letter dated April 26, 2010 from the staff (the “Staff”) of the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission (the “Commission”) regarding Prosper’s Post-Effective Amendment No. 2 to the Registration Statement (“Amendment No. 2”). The responses set forth below are numbered to correspond to the number ed comments in the Staff’s comment letter, which have been reproduced here for ease of reference. Please note that all page numbers in our responses refer to Amendment No. 2.

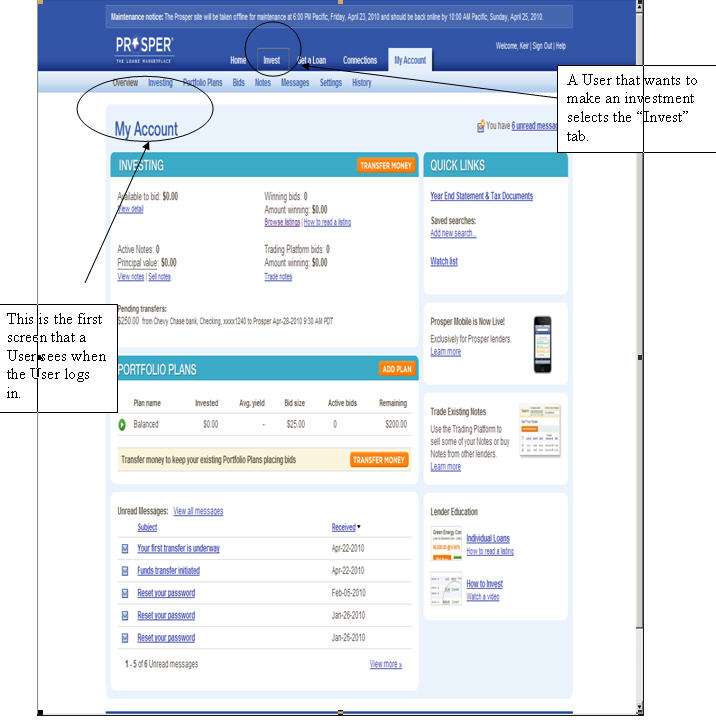

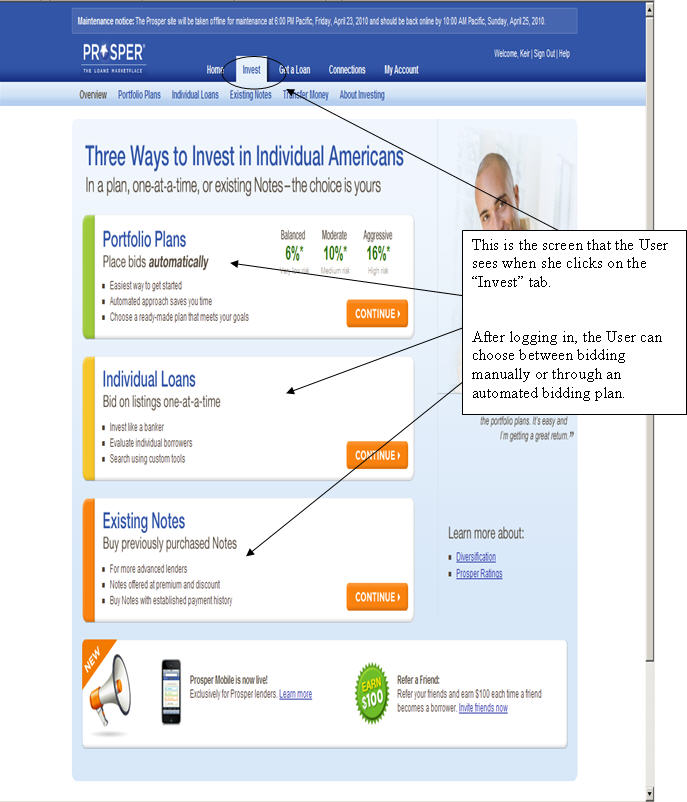

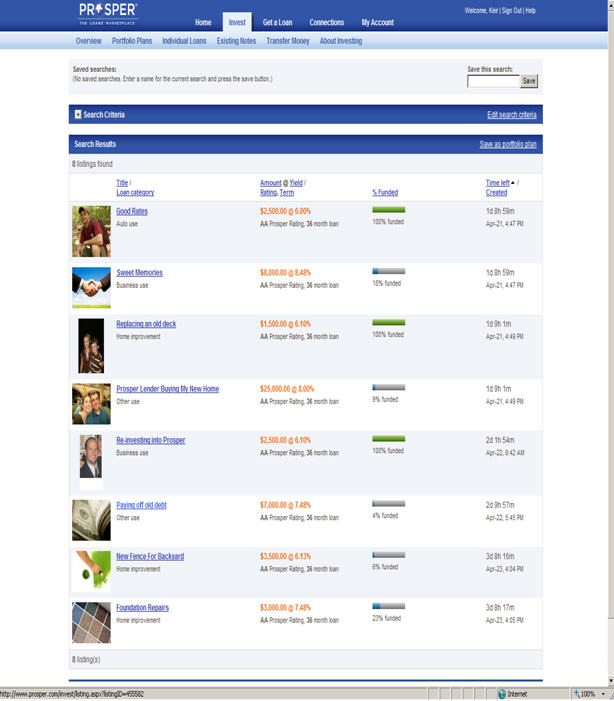

To illustrate the operation of the process by which a user of our platform (a “User”) identifies loans and eventually invests in notes (“Notes”), we have included screenshots reflecting (i) the process for creating and bidding through automated bidding plans and (ii) the manual bidding process in Appendices A and B, respectively.

Based on ongoing discussions we’ve had with the Staff in the Division of Corporation Finance and the Division of Investment Management, we propose to make the following changes to the operation of the automated bidding plan platform:

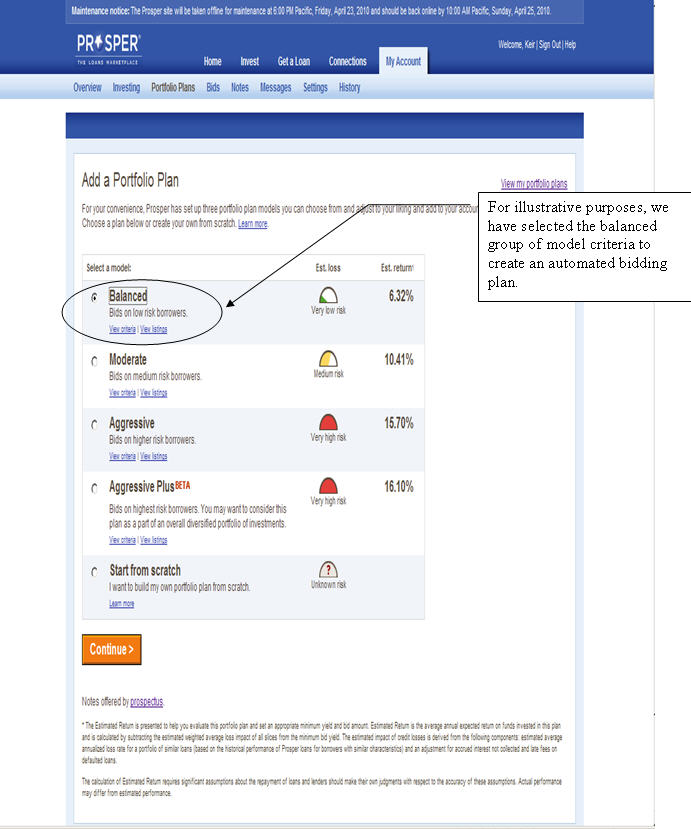

| · | Effective immediately, we will cease the auto-update feature for all new automated bidding plans; |

| · | We will, as soon as is reasonably practicable, but in any event within the next seven days, replace the labeling of our model criteria as “Aggressive,” “Moderate,” “Balanced” and any similar characterization, with neutral terms; |

| · | If we are unable to replace the labeling of our model criteria plans as “Aggressive,” “Moderate,” “Balanced” and any similar characterization by the end of the day on Monday, May 3, 2010, we will suspend the creation of new model portfolio plans until the re-characterization of such plans is complete; |

Christian Windsor

Special Counsel

U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission

April 30, 2009

Page 2

| · | We will, as soon as practicable but in any event within 14 days of May 3, 2010, revise references to the automated bidding plans on our website to: |

| o | make clear that an automated bidding plan is a portfolio of loan slices to be selected and approved by a User; |

| o | delete the presentation of estimated loss or return in the advertisements of model portfolio plans; |

| o | provide the User with greater information about the composition of the model portfolio plans (e.g., loan criteria) earlier in the plan creation process; |

| o | deemphasize any role that we play in assembling automated bidding plans and take steps to ensure that Users take greater control of the portfolio creation process; |

| · | We will, as soon as practicable, but in any event within 60 days of completing the preceding series of bullets, eliminate the current model automated bidding plans from our website; |

| · | We will, as soon as practicable, but in any event within 90 days, adopt a new automated bidding plan system that allows for the creation of automated bidding plans that are based on Prosper ratings; |

| · | Within the next two weeks, we will provide the staff in the Division of Investment Management and the Division of Corporation Finance with a draft action plan for establishing the new automated bidding plan system; and |

| · | The draft action plan that we will provide to the Staff will include a discussion of the proposed structure of the new automated bidding plan system, including a discussion of how we would propose to transition to the new system, our legal analysis of such system, and to the extent possible, screenshots or comps of how the proposed system would be presented to Users |

The following provides the Staff our responses to the comments made in connection with Amendment No. 2.

Christian Windsor

Special Counsel

U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission

April 30, 2009

General

| 1. | The Division of Investment Management continues to consider your response. They may have additional comments. |

Response: We respectfully acknowledge the Staff’s comment. Based on conversations with the Staff of the Division of Investment Management subsequent to the filing of Amendment No. 2, we hereby commit to adopt a new automated bidding plan system that allows for the creation of new automated bidding plans that are based on Prosper ratings; this system will be reviewed by the Staff in the Division of Investment Management and the Division of Corporation Finance before such structure goes into effect. In the meantime, we have included the following risk factor in Amendment No. 2:

If we are required to register under the Investment Advisers Act, our ability to conduct our business could be materially adversely affected.

The Investment Advisers Act of 1940, or the “Investment Advisers Act,” contains substantive legal requirements that regulate the manner in which “investment advisers” are permitted to conduct their business activities. We believe that our business consists of providing a platform for peer-to-peer lending for which investment adviser registration and regulation do not apply under applicable federal law, and do not believe that we are required to register as an investment adviser with either the SEC or any of the various states. The SEC or a state securities regulator could reach a different conclusion, however. Registration as an investment adviser could adversely affect our method of operation and revenues. For example, the Investment Advisers Act requires that an investment adviser ac t in a fiduciary capacity for its clients. Among other things, this fiduciary obligation requires that an investment adviser manage a client’s portfolio in the best interests of the client, have a reasonable basis for its recommendations, fully disclose to its client any material conflicts of interest that may affect its conduct and seek best execution for transactions undertaken on behalf of its client. It could be difficult for us to comply with this obligation without meaningful changes to our business operations, and there is no guarantee that we could do so successfully. If we were ever deemed to be in non-compliance with applicable investment adviser regulations, we could be subject to various penalties, including administrative or judicial proceedings that might result in censure, fine, civil penalties (including treble damages in the case of insider trading violations), the issuance of cease-and-desist orders or other adverse consequences.

| 2. | We note that you still have not responded to comments 3, 4, 5, and 7 from our original comment letter; please do so with your next submission. In particular, disclose the delinquency and default information for all loans originated since you recommenced operations as of a recent date. |

Christian Windsor

Special Counsel

U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission

April 30, 2009

| | Response: Amendment No. 2 and our annual report on Form 10-K for the year ended December 31, 2009 include disclosures that are responsive to these comments, as described below: |

| | (a) | In response to comment 3, we have updated the information in the Registration Statement regarding the performance of loans originated on our platform as of December 31, 2009. This updated information can be found on pages 24-27 and 70-79 of Amendment No. 2. |

| | (b) | In response to comment 4, we have updated the tables in the section of the Registration Statement that describes our Prosper Rating system. These updated tables can be found on pages 54-58 of Amendment No. 2. |

| | (c) | In response to comment 5, we have updated the disclosure in the Registration Statement regarding Notes purchased on our platform by related persons. This updated disclosure can be found on page 111 of Amendment No. 2. |

| | (d) | In response to comment 7, we have revised footnote 17 of our beneficial ownership table regarding the share ownership of the Omidyar Network Fund. The revised footnote can be found on page 84 of our Annual Report on Form 10-K, which is incorporated by reference into Amendment No. 2. |

| 3. | We note that you believe the actual loss performance would not provide an accurate picture of likely losses going forward because of their “unseasoned” nature. Please provide these numbers supplementally to the staff. In addition, please tell us how you determined the historical numbers used represent a more accurate picture of likely losses going forward than more recent data. |

Response: As of March 31, 2010, four loans originated on our platform since we relaunched operations on July 13, 2009 have defaulted, resulting in net charge-offs of $19,236, or 0.22% of all loans originated on the platform since relaunch (based on dollar volume). Because many of the loans originated on our platform since relaunch have only been outstanding for a few months, we do not believe this default information would provide Users with an accurate assessment of the likelihood of defaults on such loans going forward. We believe the more comprehensive information regarding loan performance that we have included in the Registration Statement, which can be found on pages 24-27 and 70-79 of Amendment No. 2, along with the information discussed in the Risk Factors Section of Amendment No. 2 under the head ing “Some of the borrowers on our platform have ‘subprime’ credit ratings, are considered higher than average credit risks, and may present a high risk of loan delinquency or default”, provide Users with the information about the historical performance of loans made through our platform that we believe to be material to their investment decision.

Christian Windsor

Special Counsel

U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission

April 30, 2009

Also, as noted in our letter to the Staff dated April 15, 2010, we intend to include information in our filings with the Commission comparing estimated and actual returns for Users who created automated bidding plans using our model criteria beginning with our Quarterly Report on Form 10-Q for the fiscal quarter ending September 30, 2010. We will update this information periodically, but no less frequently than annually, thereafter. We will also incorporate this information by reference in subsequent post-effective amendments to the Registration Statement.

| 4. | The adjustments to the model plans appear to be made without specific consent by the Lenders. This suggests that the investment decision is made at the time the Lender invests in the portfolio rather than at the time the notes are funded. Please provide us with your analysis supporting your conclusion that prior consent to changes is a sufficient manifestation of investment intent for later changes to the portfolio plans. Similarly, please provide your analysis supporting your conclusion that an initial determination to invest a specific amount in a portfolio plan slice is sufficient to show investment intent for amounts that might be invested much later as either principal and interest, or later deposits, are made into a lender members account allowing the funds to be invested. |

Response:

An Investor Does not Become Irrevocably Bound Until He Bids on an Active Loan Listing

The basic premise of the automated bidding plans is that a User selects and approves basic bidding instructions and the automated bidding plan bids on loans that become available that match the criteria selected and approved by the User. Under that system a User must indicate the minimum amount that the User wishes to bid on loans meeting the criteria included in the User’s automated bidding plan, as well as the total amount that he wishes to invest. A User cannot bid on a particular loan until the User deposits at least the minimum bid amount in his Prosper account (this is the case regardless of whether a User bids on loans manually or through an automated bidding plan). Similarly, a User cannot bid on all of the loan slices included in the UserR 17;s automated bidding plan until the User deposits the total amount that he wishes to bid in the User’s Prosper account.

Based on these two inputs, a User can effectively set up an automated bidding plan, but invest in loans on a loan-by-loan basis by depositing just enough in the User’s account to bid on one loan, and deferring future bids until such time that the User deposits enough money in its account for subsequent bids. By use of the priority settings, a User can further control this process by putting loan slices in the order in which he would like to bid upon them as they

Christian Windsor

Special Counsel

U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission

April 30, 2009

Page 6

become available. A User can cancel or modify his automated bidding plan at any time and is only bound to purchase Notes that relate to loans upon which the User already has successfully bid.1

Based on these facts, we respectfully submit that a User who invests in Notes by use of an automated bidding plan makes an irrevocable investment decision with respect to a particular Note only when all of the following conditions have been met:

| | (i) | the User approves the loan slices included in his automated bidding plan, all of which are displayed before the User can approve the composition of his automated bidding plan, |

| | (ii) | the User provides sufficient funds in his account to satisfy the minimum bid amount established by the User, and |

| | (iii) | the User’s bid is placed on a loan that matches the criteria selected by the User, which could take place immediately after the automated bidding plan is created or possibly months after such plan is created. |

No sale takes place until all of these conditions have been met. We believe that this is the “time of sale” for the purposes of the Securities Act, which the SEC has indicated is the point in time at which a purchaser either enters into a contract of sale relating to a security (including by virtue of acceptance by the seller of an offer to purchase) or completes the purchase of a security. See SEC Rel. No. 33-8591 (Jul. 19, 2005). In some ways, a bid made on a loan through an automated bidding plan is analogous to an offer to purchase; it does not become binding until Prosper accepts the bid by placing a bid at the User’s direction on a loan that meets the criteria selected by the User.&# 160; We believe that this interpretation is consistent with generally understood principles of securities law. See Cohen v. Stratosphere Corp., 115 F.3d 695 (9th Cir. Nev. 1997) (execution of a subscription agreement does not create a binding contract for the purchase of securities if the seller has the right to reject subscriptions and has not accepted such subscriptions); see alsoSEC v. Carriba Air, Inc., 681 F.2d 1318, 1324 (11th Cir. 1982) (where the seller does not have a right to reject offers to purchase, a sale occurs when investors placed funds in escrow and such investors became irrevocably committed to purchase securities).

Based on the foregoing, a User’s initial determination to invest a specific amount through an automated bidding plan is irrelevant if such determination isn’t followed by other

1 Prosper retains the right to terminate any active loan listing prior to funding.

Christian Windsor

Special Counsel

U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission

April 30, 2009

Page 7

steps. It is the funding of an account, followed by the placement of a bid on a loan that matches criteria selected and approved by the User, that reflects a User’s investment intent.2

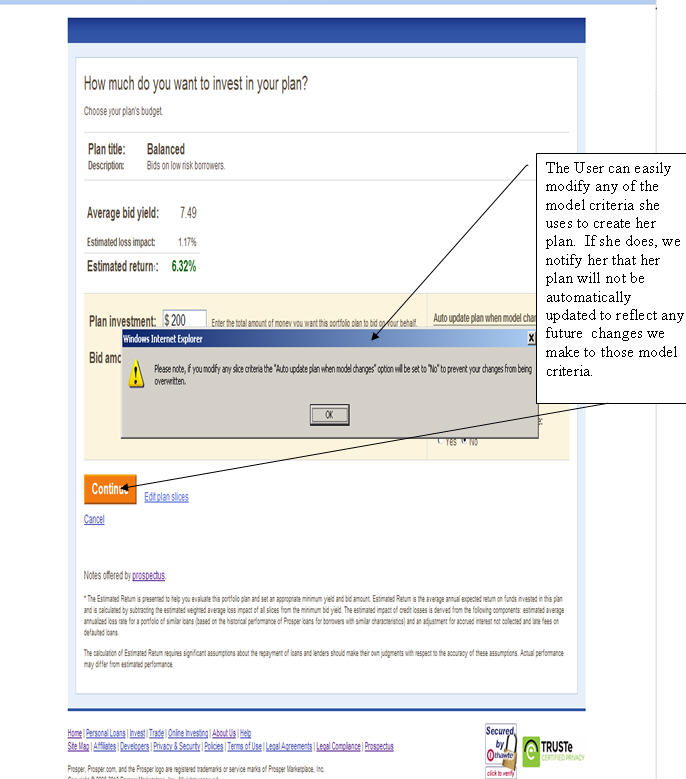

Changes to an Automated Bidding Plan

As part of the process of creating an automated bidding plan, if a User elects to create an automated bidding plan using our model criteria, the User is asked whether he wants to have that plan criteria updated to match changes to those model criteria.3 A User who makes this election also can elect to be notified of updates to the model plan criteria when they occur. A User who elects to receive such notices is notified two business days prior to the effective date of any changes made to the User’s automated bidding plan. If the User objects to changes to the criteria included in his automated bidding plan, the User can decline such changes, modify the automated bidding plan himself, cancel the automated bidding plan or remove funds from the User’s account so that the User’s plan cannot bid on future loan listings. In this regard, it is important to note that over 90% of the Users that have automated bidding plans that are eligible for updating have elected to receive notice of changes prior to such changes being made to their automated bidding plans.

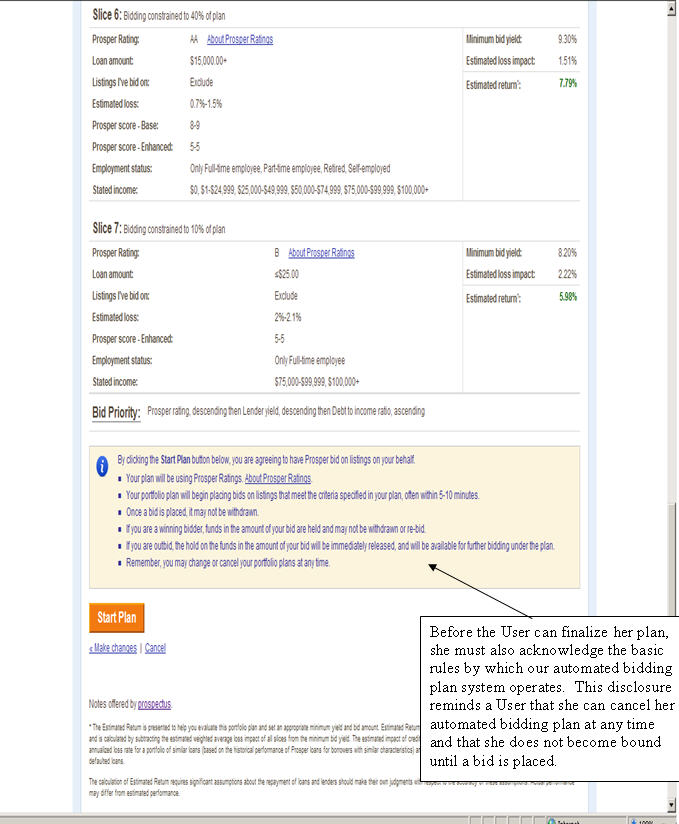

We believe that the combination of disclosures made about automated bidding plans, the steps that a User must take in order to approve an automated bidding plan, the disclosures made before the User can finalize his automated bidding plan, and the notice that a User generally receives before changes are made to his automated bidding plan, all provide a User with a meaningful opportunity to evaluate whether the User wants to allow changes to be made to his automated bidding plan before such changes are effective.

| 5. | The staff is unable to conclude that the portfolio plans do not constitute an investment in a separate security based on the analysis you have provided in response to our former comment 6. For example, in the marketing, selection criteria and management of the portfolios, it appears that Prosper exercises a certain amount of control. We note that Prosper markets sample portfolios they have constructed and analyzed as “Balanced,” “Moderate,” and “Aggressive;” we |

2 Notably, this investment intent only applies to the specific bid being placed; after a User places a bid through an automated bidding plan, he can modify his plan criteria, in which case additional bids will only be placed on loans that meet those modified criteria, or he can terminate the plan altogether, in which case no additional bids will be placed through the plan .

3 Note that this feature only applies to a plan that is based solely on model criteria, where those criteria are not modified in any way. The adjustments that we make from time to time generally relate to the technical operation of an automated bidding plan, including, for example, adjustments to incorporate changes to loan criteria (e.g., the elimination or creation of new loan criteria). It is also important to note that the total investment and minimum bid amounts established by the User in setting up a plan are never affected by changes to our model plan criteria. These amounts can only be modified by the User.

Christian Windsor

Special Counsel

U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission

April 30, 2009

Page 8

| | also note that Prosper makes periodic adjustments to the portfolios without obtaining specific Lender acceptance. Please address our concerns in your response. |

Response: We respectfully submit that our efforts with respect to the automated bidding plans do not create a separate security from the Notes for the following reasons:

| 1. | Automated bidding plans do not involve a common enterprise; |

| 2. | Automated bidding plans do not involve an expectation of profits primarily based on our efforts in connection with the automated bidding plans; |

| 3. | The only contract of sale formed on our platform relates to the sale of the Notes; |

| 4. | We do not “manage” any User’s automated bidding plan; and |

| 5. | The automated bidding plans do not involve an investment contract under Gary Plastic Packaging Corporation v. Merrill, Lynch, Fenner & Smith. |

Each of these reasons is discussed in turn below.

| | 1. | Automated Bidding Plans Do Not Involve a Common Enterprise |

The investment contract test analysis articulated in SEC v. W.J. Howey Co., 328 U.S. 293 (1946) focuses on whether an enterprise involves the investment of money in a common enterprise with the expectation of profits based primarily on the efforts of others. As discussed in our prior comment letter, we do not believe that each of these factors is present here. For the purposes of this comment letter, however, we focus on the “common enterprise” and “primarily based on the efforts of others” prongs of the analysis.

Horizontal Commonality: Automated Bidding Plans Do Not Involve the Pooling of Investor Assets

A majority of judicial circuits that have considered the issue follow the horizontal approach to a common enterprise, which focuses on the relationship among investors in an economic venture. Integral to this approach is the pooling of investors’ money in a common venture.4 Here, there is no pooling of User assets within an automated bidding plan. A User’s

4 The DC, First, Second, Third, Fourth, Sixth, and Seventh Circuits all apply the horizontal approach. See Ryan Borneman, Why the Common Enterprise Test Lacks a Common Definition, A Look Into the Supreme Court’s Decision of SEC v. Edwards, 5 U.C. Davis Bus. L.J. 16 (2005).

Christian Windsor

Special Counsel

U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission

April 30, 2009

Page 9

creation of an automated bidding plan is absolutely independent of, and has no bearing on, the creation of an automated bidding plan by other Users. As noted before, even if two Users create identical automated bidding plans, there would be no pooling of their assets in a common plan and no certainty that the two Users would ultimately purchase the same Notes through their respective plans. If there is any pooling of assets associated with an automated bidding plan, it occurs when a User successfully bids on a loan and receives a Note, which already is treated as a security and registered with the SEC.

Strict Vertical Commonality: There is No Correlation Between the Success or Failure of a User’s Automated Bidding Plan and Our Success or Failure

The Ninth Circuit follows a strict vertical commonality approach under which a court examines whether the promoter and the investor are both exposed to risk and the profits and losses of investor and promoter are correlated. The leading statement of what constitutes vertical commonality was rendered by the Court of Appeals for the Ninth Circuit in SEC v. Glenn W. Turner Enterprises, Inc., 474 F.2d 476 (9th Cir.), cert. denied, 414 U.S. 821, 94 S. Ct. 117, 38 L. Ed. 2d 53 (1973). In that case, the court found a common enterprise where the financial arrangement was “one in which the fortunes of the investor (were) interwoven with and dependent upon the efforts and success of those seeking the investment.” Glenn W. Turner Enterprises at 482 n.7.

As noted previously, we derive no profits from the automated bidding plans. We do not charge a fee for the use of such plans, receive any special compensation for the loans identified by investors through automated bidding plans, or receive a fee for the administration of the automated bidding plan system on an ongoing basis. Instead, our profits are derived solely from the fees we charge in connection with originating and servicing loans funded on our platform (regardless of whether they are funded through manual bids, bids placed by automated bidding plans, or a combination of the two). Similarly, the failure of Users to use automated bidding plans, or to successfully bid upon Notes through the use of such plans, has absolutely no bearing on our success or failure as an enterprise. Whether we succeed or fail as an enterprise depends primarily on the successful attraction of borrowers and lenders to our website, our effective provision of tools for investors to identify loans in which they are interested and our effective servicing of the loans underlying the Notes. For the purposes of the Howey test, the potential profits that Users may achieve through successful bids on Notes as a result of utilizing our automated bidding plan system are in no way linked to our profits from such system (which, incidentally, are non-existent).

In this respect, the Ninth Circuit’s position in Mordaunt v. Incomco, 686 F.2d 815, (9th Cir. 1982), cert denied, 469 U.S. 1115, 83 L. Ed. 2d 793, 105 S. Ct. 801, 1985 U.S. LEXIS 470 (1985) is quite relevant to the comments raised by the Staff. In Mordaunt, the Court of Appeals for the Ninth Circuit rejected an argument that discretionary commodities trading accounts were investment contracts. The plaintiffs in Mordaunt argued that vertical commonality existed because the success or failure of the investments made through the discretionary commodities

Christian Windsor

Special Counsel

U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission

April 30, 2009

Page 10

trading accounts collectively were essentially dependent upon promoter expertise. In rejecting this argument, the Court of Appeals noted its opinion in Brodt v. Bache & Co., 595 F.2d 459 (9th Cir. 1978), where the court stated:

The success or failure of Bache as a brokerage house does not correlate with individual investor profit or loss. On the contrary, Bache could reap large commissions for itself and be characterized as successful, while the individual accounts could be wiped out. Here, strong efforts by Bache will not guarantee a return nor will Bache’s success necessarily mean a corresponding success for Brodt. Weak efforts or failure by Bache will deprive Brodt of potential gains but will not necessarily mean that he will suffer serious losses. Thus, since there is no direct correlation on either the success or failure side, we hold that there is no common enterprise between Bache and Brodt. 595 F.2d at 461.

The court in Mordaunt went on to note that:

Under Brodt, there is no common enterprise unless there is some direct relation between the success or failure of the promoter and that of his investors. In this case, as in Brodt, such direct relation is lacking. Incomco earned commissions totaling $20,190.00 on the Mordaunts’ accounts during the period in which the Mordaunts’ collective losses amounted to $27,385.03.

By analogy, as noted above, there is no direct relationship between a User’s “profits” and our success or failure in administering the automated bidding plan system, regardless of the level of control exerted over the administration of the system. In fact, as was the case in Mordaunt, it is possible that we could generate revenues even if a User has losses in connection with the Notes purchased by such User through his automated bidding plan. We believe our case is even stronger than that of the defendants in the Mordaunt case; in our case, unlike a discretionary commodities trading account, the investor is ultimately responsible for selec ting the loans that will be bid upon through the automated bidding plans. All we have done is establish a tool that an investor can use to identify such loans. As discussed in our prior comment letter, the criteria to be used to identify loans are fully customizable, and these same criteria are available for use by Users whether they identify loans through manual bidding or through an automated bidding plan. See Appendices A and B.

Broad Vertical Commonality: There is No Correlation Between the Success or Failure of a User’s Automated Bidding Plan and Our Efforts With Respect to Such Plans

The Fifth, Eighth and Eleventh Circuits follow a broad vertical approach under which a common enterprise exists if the success of an investor depends on a promoter’s expertise. See e.g., SEC v. Continental Commodities Corp., 497 F.2d 516 (5th Cir. 1974)(“the requisite

Christian Windsor

Special Counsel

U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission

April 30, 2009

Page 11

commonality is evidenced by the fact that the fortunes of all investors are inextricably tied to the efficacy of the (investment manager’s efforts)”).5 Although we do not believe that the broad vertical commonality approach reflects the majority view of the investment contract analysis, this prong of the Howey test is lacking as well. Our efforts associated with the maintenance of our automated bidding plan system do not materially impact the likelihood that Users will profit from purchasing Notes using that system. Whether we expend a lot or a little of effort will not materially affect the profitability of Notes purchased through automated bidding plans; a User’s profits will ultimately depend on the performance of the loans underlying the Notes she has purchased and not on the fact that the Notes were purchased by use of the automated bidding plan system.

| | 2. | Automated Bidding Plans Do Not Involve An Expectation Of Profits Primarily Based On Our Efforts In Connection With The Automated Bidding Plans |

Our efforts with respect to automated bidding plans do not create an expectation of profits that is distinct from the expectation relating to the Notes. This is because Users have too much control over the creation of the automated bidding plan for it to be said that the expectation of profits associated with an automated bidding plan, if any, is based solely on our efforts. See Albanese v. Florida Nat’l Bank of Orlando, 823 F.2d 408, 410 (11th Cir. 1987) (“If the investor retains the ability to control the profitability of his investment, the agreement is no security.”). Indeed, as noted by the Eleventh Circuit:

Courts have found investment contracts where significant efforts included the pre-purchase exercise of expertise by promoters in selecting or negotiating the price of an asset in which investors would acquire an interest. See Sec. & Exch. Comm’n v. Eurobond Exch., Ltd., 13 F.3d 1334 (9th Cir.1994) (involving interests in foreign treasury bonds); Gary Plastic Packaging Corp. v. Merrill Lynch, Inc., 756 F.2d 230 (2d Cir. 1985) (involving interests in certificate of deposit program); Glen-Arden Commodities, Inc. v. Costantino, 493 F.2d 1027 (2d Cir. 1974) (involving investments in warehouse receipts for whiskey).

5 The problem with the broad vertical commonality approach was articulated in Berman v. Bache, Halsey, Stuart, Shields, Inc., 467 F. Supp. 311, 319 (S.D.Ohio 1979), where the court noted that a finding of a common enterprise based solely upon the fact of entrustment by a single principal of money to an agent effectively excises the common enterprise requirement of the Howey test and only require (1) the investment of capital (2) with the expectation of profit through the efforts of others, for nothing more is involved in a single discretionary trading account. See also Revak v. SEC Realty Corp ., 18 F.3d 81, 87-88 (2d Cir. N.Y. 1994) (“If a common enterprise can be established by the mere showing that the fortunes of investors are tied to the efforts of the promoter, two separate questions posed by Howey -- whether a common enterprise exists and whether the investors’ profits are to be derived solely from the efforts of others -- are effectively merged into a single inquiry: “whether the fortuity of the investments collectively is essentially dependent upon promoter expertise.”)

Christian Windsor

Special Counsel

U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission

April 30, 2009

Page 12

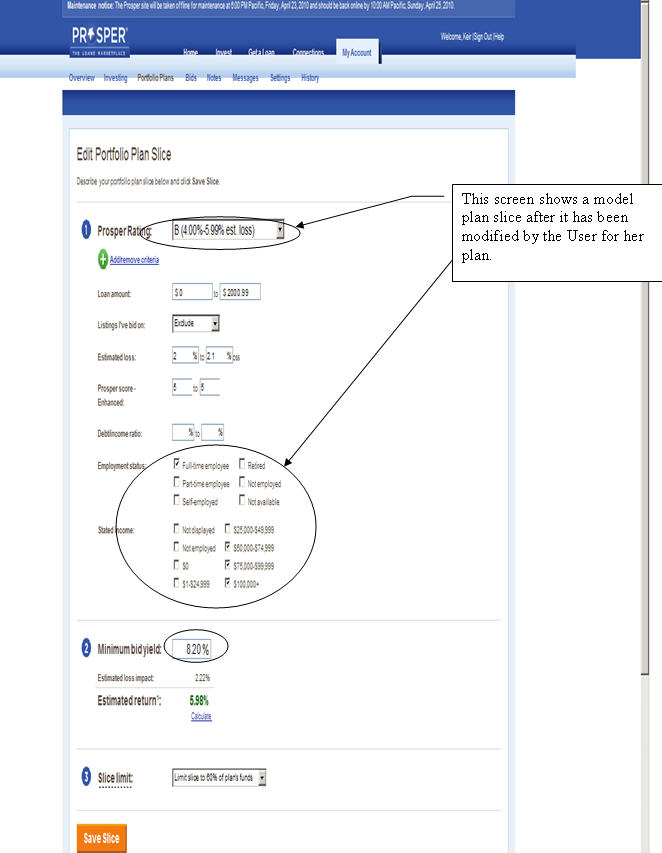

SEC v. Mutual Benefits Corp, 408 F.3d 737 (11th Cir. 2005). Here, a User controls every aspect of the process by which his automated bidding plan is created, including the selection of loans that the User bids upon (through the selection of plan criteria) and the price of the Notes acquired (i.e., the minimum yield). In addition, once created, the User can modify or terminate his plan as he sees fit.

Our Creation and Characterization of Model Plan Criteria And Our Modification of These Criteria Do not Create an Expectation of Efforts that is Distinct from the Expectation of Profits that a User Has With Respect to a Note

We understand that the Staff may be concerned that our ability to update an automated bidding plan if a User so elects may create an expectation of profits from our administration of the automated bidding plan system. It should be noted that we do not emphasize the updating feature in our advertisements relating to the automated bidding plans. In fact, we do not discuss the automatic updating feature anywhere on our website except on the page where a User who is in the process of creating an automated bidding plan is asked whether he wants to have his plan criteria automatically updated. In light of this fact, it is doubtful that the automatic updating feature creates an expectation of profits that is meaningfully different from the expectation of profits as sociated with the Notes more generally.

We also understand that the Staff may be concerned about our characterization of our groups of model criteria as “Balanced,” “Moderate,” and “Aggressive;” and our selection of such criteria. These actions are intended to provide a User with a starting point for creating his own automated bidding plan. Because the User can modify all or none of our model criteria, our acts in creating those criteria are superseded by the User’s acts in creating and approving an automated bidding plan that adopts those criteria wholesale or modifies the criteria to suit the investor’s individual investment judgment.

In SEC v. Glenn W. Turner Enterprises, Inc., 474 F.2d 476, 482 (9th Cir. 1973), the Ninth Circuit indicated that the critical inquiry in similar circumstances is “whether the efforts made by those other than the investor are the undeniably significant ones, those essential managerial efforts which affect the failure or success of the enterprise.” Similarly, the Fifth Circuit has indicated that:

It must be emphasized that the assignment of nominal or limited responsibilities to the participant does not negative the existence of an investment contract; where the duties assigned are so narrowly circumscribed as to involve little real choice of action or where the duties assigned would in any event have little direct effect upon receipt by the participant of the benefits promised by the promoters, a security may be found to exist. As the Supreme Court has held, emphasis must be placed upon economic reality. See Securities and Exchange Commission v. W.J. Howey Co., 328 U.S. 293, 90 L. Ed. 1244, 66 S. Ct. 1100 (1946).

Christian Windsor

Special Counsel

U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission

April 30, 2009

Page 13

SEC v. Koscot Interplanetary, Inc., 497 F.2d 473, 483 n.14 (5th Cir. 1974). Here, the “undeniably significant efforts” with respect to the automated bidding plans are the efforts made with respect to the Notes themselves and not our creation of the automated bidding plan system. The efforts that are highlighted by the Staff’s comments: the marketing, selection criteria and “management” of the plans, the characterization of the groups of criteria as “Balanced,” “Moderate,” and “Aggressive;” and periodic modifications to those criteria, are not the efforts that create a “security” within the meaning of the Securities Act. Instead, the principal efforts that we make with respect to Notes sold through our platform include:

| · | our creation of an online platform for individuals to request and make peer-to-peer loans, including our creation of the Internet-based auction process for bidding on loans; |

| · | our establishment of a market for secondary trading of all Notes on our platform; |

| · | our efforts to market peer-to-peer lending in order to attract new lenders and borrowers; |

| · | our development and collection of detailed criteria that lenders may use to identify loans in which they may be interested; |

| · | our ongoing analysis of loan performance and presentation of analytical and statistical data that allow a User to identify loans in which he is interested; |

| · | our efforts to investigate the information that borrowers provide about themselves; |

| · | our creation and application of the “Prosper Rating” credit rating system; |

| · | our efforts to mitigate the risk of non-payment (e.g., through the use of collection agents, etc.); and |

| · | our servicing of loans made through our platform. |

The efforts described above apply to manual and automated bidding. We believe that it is these efforts, if any, that create a “security” within the meaning of the Securities Act. The additional efforts that are the subject of the Staff’s comment, while meaningful, do not fundamentally change the nature of what a User seeks when he chooses to invest money through our platform: an opportunity to receive payments from Notes.

Even if the Staff were to focus exclusively on the efforts related to our automated bidding plan system, it is clear that the undeniably significant acts with respect to that system relate to the creation and approval of each User’s automated bidding plan, every aspect of which is subject to that User’s discretion. It cannot be said that a User’s choices are “narrowly

Christian Windsor

Special Counsel

U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission

April 30, 2009

Page 14

circumscribed” or that a User has “little real choice of action” with respect to the construction of an automated bidding plan. To the contrary - a User can choose from among any of the criteria by which we categorize loans in creating his plan. Further, a User can ignore our model plan criteria entirely and create an automated bidding plan from scratch. Because all of these choices are left to the discretion of the User, the User’s actions in creating an automated bidding plan are the “undeniably significant ones” for the purposes of the Howey test.

| | 3. | The Only Contract of Sale Formed on Our Platform Relates to the Sale of the Notes |

The Securities Act defines the term “sale” to include “every contract of sale or disposition of a security or interest in a security for value.” In Radiation Dynamics Inc. v. Goldmuntz, 464 F.2d 876 (2d Cir. 1972), the court approved a jury instruction that a purchase or sale occurred for Rule 10b-5 purposes “when the parties to the transaction are committed to each other.” See also Hill v. Equitable Bank, 599 F. Supp. 1062, 1072 (D.Del. 1984) (concluding that a sale of securities occurs when parties enter into “a binding commitment to undertake a securities transaction, even though full performance of the transaction does not occur unt il a later date”).

As noted in the response to comment number four, a User is not irrevocably committed to purchase securities, and therefore has not entered into a contract of sale, until the User’s bid is placed on a loan that matches the criteria selected by the User. Before such time, a User is not bound in any way to purchase a security. A User can withdraw any funds included in the User’s Prosper account, change his automated bidding plan or eliminate his automated bidding plan entirely at any time. Even if a User selects an automated bidding plan and fully funds that plan, the User is not irrevocably bound to purchase Notes until such time that we accept the User’s bid pursuant to such plan and places the User’s bid on a loan that is identified through the automated bidding plan. Ev en then the User can delete all of the remaining slices included in the automated bidding plan and withdraw all of the User’s remaining funds from his Prosper account. In such an event, the only contract to which the User is bound is the contract relating to the bid that the User has placed.

If there is no binding contract until we accept a bid and place it on a loan request, the actions taken with respect to an automated bidding plan necessarily cannot involve the offer or sale of a security relating to the automated bidding plan prior to such time. Further, the Note is the only security being “sold” at that time, and not an interest in the automated bidding plan.

| | 4. | We Do not “Manage” a User’s Automated Bidding Plan |

We do not manage a User’s automated bidding plan. A User who sets up an automated bidding plan is responsible for the management of such automated bidding plan. At most, we provide a User with model criteria as a starting point to create a plan, and provide him with the option of having his portfolio updated to incorporate changes we make to the model criteria, if

Christian Windsor

Special Counsel

U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission

April 30, 2009

Page 15

any, on which his plan is based. Every meaningful decision that is made with respect to that plan, including with respect to the size, risk level and specific criteria included in the plan, all are subject to the management of the User.

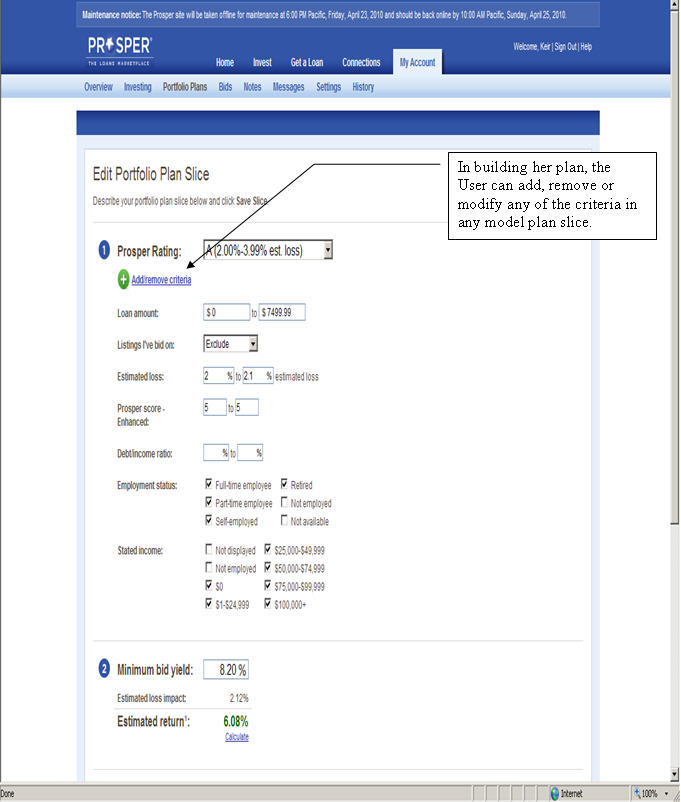

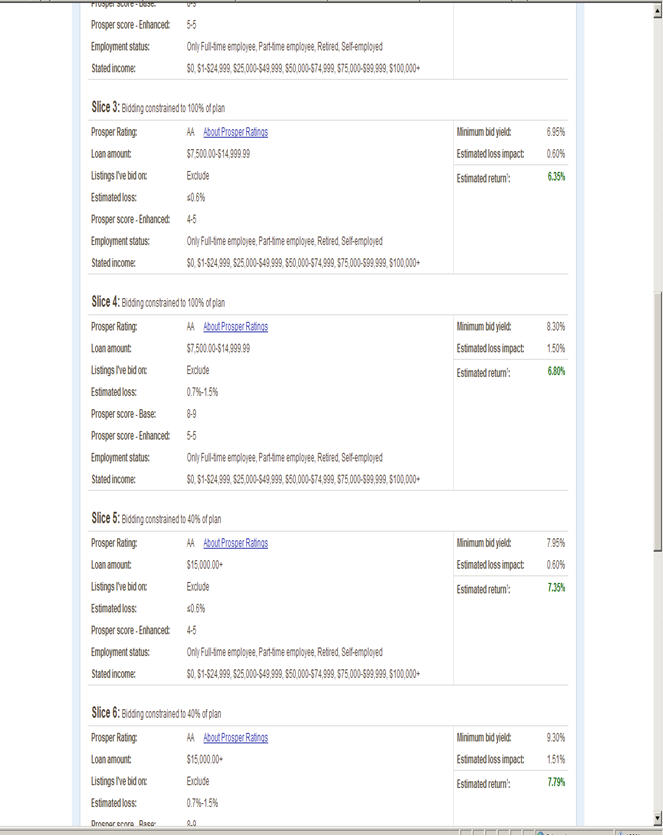

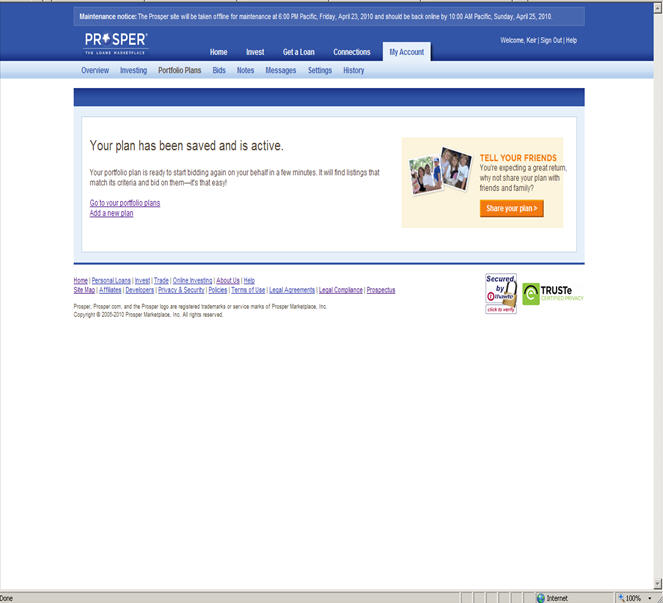

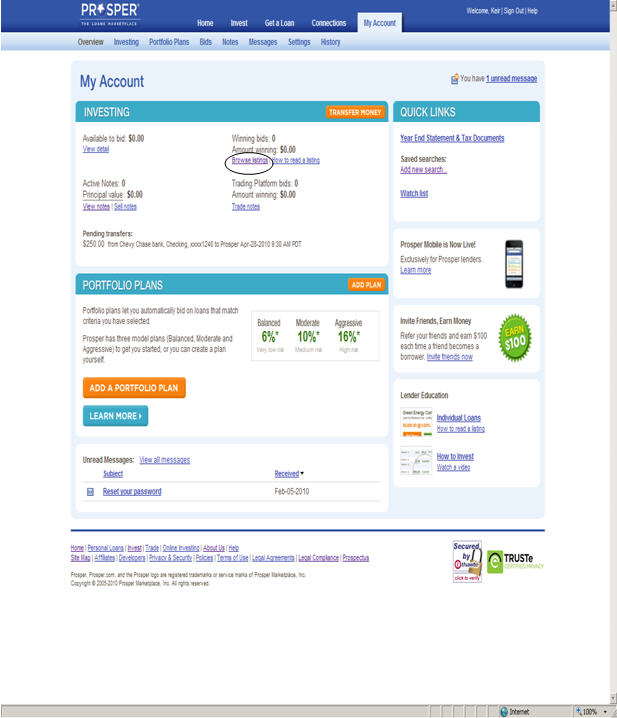

A User must click through at least five screens before he can finalize an automated bidding plan. At every step along the way, the User may modify any of the criteria included in the slices that make up his automated bidding plan. The User selects the minimum bid amount, the total amount to be bid, and the bid priority for slices included in his automated bidding plan. Finally, before the User can approve his automated bidding plan, he must scroll past each of the loan slices included in the plan and approve them all. After the User approves the automated bidding plan he has selected, he can modify or delete that plan at any time, including after making bids on loans matching criteria prescribed by loan slices included in the User’s portfolio. � 60;In light of this level of control, we do not believe it can be said that Prosper “manages” a User’s automated bidding plan.

We believe that the level of control exhibited by a User who creates an automated bidding plan distinguishes the automated bidding plans from comparable investment products that the SEC views as involving investment contracts. For example, the SEC discussed the issue of control in describing employee benefit plans:

Whether a separate security in the form of a plan interest exists in participant-directed plans depends on the circumstances. …. Where the sponsor under such a trust or arrangement acts as a mere custodian of the participant’s account without rendering investment advice or commingling the assets of the account with those of other accounts, and the participant retains complete investment discretion and control over the account, the Staff generally has taken a no-action position regarding the registration of interests in the plan or arrangement.

A different situation exists where the sponsor or trustee of a participant-directed plan actively manages the funds provided to him by plan participants. Thus, for example, corporate thrift, savings or similar plans which allow participants to direct their investments into any of several investment funds managed by the plan trustees of administrators would be deemed to involve securities in the form of employee interests. In such cases, it is clear that the employees are relying on the plan managers to maintain the various funds in a manner that will produce profits and thereby enhance their investment.

SEC Rel. No. 33-6281 (Jan. 15,1981). Here, our role as sponsor of the automated bidding plan automated bidding system is much more of a custodial role than one as an active manager. We do not provide investment advice or commingle a User’s assets with those of other Users. Moreover, the User retains complete control of his Prosper account and his plan. With the exception of bids that already have been made, a User can modify or terminate an automated bidding plan at any time and without any approval or other input from Prosper. Even though

Christian Windsor

Special Counsel

U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission

April 30, 2009

Page 16

we modify model criteria from time to time, we do not update a User’s plan unless he has elected to allow us to do so and even then the User can opt out of any change to the model criteria prior to such changes being made to the slices included in his plan.

| | 5. | The Automated Bidding Plans Do Not Involve an Investment Contract under Gary Plastic Packaging Corporation v. Merrill, Lynch, Fenner & Smith |

We appreciate that the Staff has reservations about the actions that we take with respect to the automated bidding plan system, however we respectfully submit that these actions do not distinguish the Notes bid upon through the automated bidding plan system from those bid upon through manual bidding. We believe that this point is made most clearly by a comparison of these actions to the actions taken by Merrill Lynch in Gary Plastic Packaging Corporation v. Merrill, Lynch, Fenner & Smith, 756 F.2d 230 (2d Cir. 1985).

In Gary Plastic, the court noted the following actions that Merrill Lynch took with respect to the $100,000 CDs (“Jumbo CDs”) offered as indicative of the creation of an investment contract that was distinct from the CDs underlying the Jumbo CDs:

Merrill Lynch is engaged in activity that is significantly greater than that of an ordinary broker or sales agent. Since Merrill Lynch possesses significant economic power, it is able to negotiate with the issuing banks to obtain a favorable rate of interest. Pursuant to defendants’ scheme, the banks create new CDs that carry interest rates lower than those they pay their direct customers. From this differential, Merrill Lynch receives a commission for its services, which include providing a secondary market and cultivating a large group of banks that desire to borrow money. Therefore, a significant portion of the customer’s investment depends on Merrill Lynch’s managerial and financial expertise.

The court in Gary Plastic cited the following in support of its conclusion that Merrill Lynch’s efforts with respect to the Jumbo CDs involved an investment contract:

| · | the secondary market maintained by Merrill Lynch created an opportunity for liquidity and capital appreciation that would not be available otherwise, and even if available, would not be available without penalty; |

| · | Merrill Lynch committed to repurchase Jumbo CDs purchased through its program if interest rates dropped; and |

| · | Merrill Lynch implicitly promised to maintain its marketing efforts, which were critical to the success of the secondary market for the Jumbo CDs and the availability of Jumbo CDs at competitive rates. |

Christian Windsor

Special Counsel

U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission

April 30, 2009

Page 17

By way of contrast, we do not attach any features to Notes purchased through the automated bidding plan system or provide any services through our plan system that enhance the value of Notes. For example:

| · | all of the economic terms of a Note purchased through an automated bidding plan are identical to the terms of Notes issued in connection with the loan upon which the Note is based, regardless of whether such Notes were acquired through manual bids or an automated bidding plan; |

| · | the opportunity for liquidity and capital appreciation created by the secondary market for the Notes is the same, regardless of how a Note is purchased -- there is no secondary market that is specific to automated bidding plans; |

| · | a User who bids on a loan identified through an automated bidding plan generally has no better or worse chance of finding a loan that meets the User’s selection criteria than a User who bids on loans manually; and |

| · | unlike Merrill Lynch’s efforts to “cultivate” banks to offer CDs through its program, we do not do make any special efforts in order to attract borrowers to our platform to make loans available to Users who have established automated bidding plans. |

Based on the foregoing, we believe that our automated bidding plan system is distinguishable from the offering at issue in Gary Plastic.

| | 6. | Registration of Interests in the Automated Bidding Plans Does Not Provide Additional Investor Protection |

The Supreme Court has long espoused a broad construction of what constitutes an investment contract, in an effort “to afford the investing public a full measure of protection.” Howey, 328 U.S. at 298. The investment contract case law thus “embodies a flexible rather than a static principle, one that is capable of adaptation to meet the countless and variable schemes devised by those who seek the use of the money of others on the promise of profits.” Id. at 299. In applying the investment contract analysis, courts are instructed to apply the investment contract test in light of the economic realities of the transaction. United Hous. Found., Inc. v. For man, 421 U.S. 837, 851-52, 44 L. Ed. 2d 621, 95 S. Ct. 2051 (1975); Tcherepnin v. Knight, 389 U.S. 332, 336, 19 L. Ed. 2d 564, 88 S. Ct. 548 (1967); Futura Dev. Corp. v. Centex Corp., 761 F.2d 33, 39 (1st Cir. 1985).

Here, the economic reality is that Users choose to use automated bidding plans for the same reasons that they bid manually: in order to invest in Notes. While we appreciate the Staff’s concerns regarding the operation of the automated bidding plans, we do not believe that such concerns warrant registration of the automated bidding plans as separate interests. In fact, such registration would be superfluous. We believe that, as a result of the registration of the

Christian Windsor

Special Counsel

U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission

April 30, 2009

Page 18

Notes, any communications made by us in connection with the automated bidding plans are subject to liability under the antifraud provisions of the Securities Act, including Section 11, Section 12(a)(2) and Section 17. Further, we expect that the antifraud provisions of the Exchange Act, Section 10(b) and Rule 10b5-1 thereunder would apply in full measure to any statements we made in connection with the sale of Notes through the automated bidding plans. Since investors have the same protections under the Securities Act regardless of whether the automated bidding plans are registered as securities, we can see no principled reason for requiring their registration, particularly in light of the strong arguments against the characterization of the Notes as investment contracts.

In contrast to the minimal investor protection benefits that would be derived from registration of the automated bidding plans, taking the position that such plans have to be registered could have devastating effects on our business and could potentially cause us to cease operations. We believe that we can make modifications to the automated bidding plans to alleviate any questions raised about whether the automated bidding plans involve a separate security. Given that the SEC’s mission is both to protect investors and to facilitate the formation of capital, we believe that it would be most consistent with the SEC’s mission to address the Staff’s concerns without registration.

To clarify the risks posed to Prosper by automated bidding plans, we will include the following risk factor in our next prospectus supplement and our next post-effective amendment to the Registration Statement:

Prosper’s administration of the portfolio plan system could create additional liability for Prosper and such liability could be material

A lender can identify loans on Prosper’s website in one of two ways: manually, or through a “portfolio plan.” Portfolio plans are automated bidding tools that allow a lender to place bids efficiently using criteria the lender sets, without having to look through every listing or worry about listing end dates. A lender specifies the amount of money and minimum yield percentage to bid on listings that meet the lender’s criteria, such as Prosper Rating, number of current delinquencies, or other listing features. Prosper offers several plans as models with pre-filled criteria that will help get a lender started. Since our relaunch in July 2009, approximately 51% of the bids made on our platform (measured in terms of dollar volume) were made by members using our portfolio plan system.

Portfolio plans represent a portfolio of loan criteria, that if implemented, allow a lender to bid on loans meeting such criteria. Since the Notes ultimately purchased as a result of a portfolio plan are the same as Notes purchased manually, they present the same risks of non-payment as all Notes that may be purchased on Prosper’s website. For example, as with any other Note purchased through Prosper’s website, there is a risk that a loan identified through a portfolio plan may become delinquent or default, and the

Christian Windsor

Special Counsel

U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission

April 30, 2009

Page 19

estimated return and estimated loss for that loan individually, or the estimated loss or return for the portfolio plan as a whole, may not accurately reflect the actual return or loss on such loan. If this were to occur, a lender who purchases a Note through a portfolio plan could pursue a claim against Prosper in connection with its representations regarding the performance of the loans bid upon as a result of the portfolio plan. An investor could pursue such a claim under various antifraud theories under federal and state securities law. To date, no actions have been taken or threatened against us on this theory, however, such actions could have a material adverse effect on our business.

| 6. | Revise your discussion of your continued losses (on page 36 of the marked version of your response) to discuss Prosper’s available liquidity as of a recent date. Also, please discuss the potential impact upon your ability to continue as a going concern if the amount realized as a result of the private placement were to be materially reduced. Revise your disclosure to place the risks associated with your lack of liquidity under a separate subheading. |

Response: We will revise the discussion of our continued operating losses in our next post-effective amendment to the Registration Statement to reflect our consummation of a new round of equity financing on April 15, 2010. The total amount of this financing was within the range anticipated by us and contemplated in the letter of intent we entered into with respect to the financing on March 30, 2010, which is described on page 36 of Amendment No. 2.

* * * * * * *

In connection with the Staff’s comments, we hereby acknowledge that:

| · | we are responsible for the adequacy and accuracy of the disclosure in the filing; |

| · | Staff comments or changes to disclosure in response to Staff comments do not foreclose the Commission from taking any action with respect to the filing; and |

| · | we may not assert Staff comments as a defense in any proceeding initiated by the Commission or any person under the federal securities laws of the United States. |

| | Sachin Adarkar General Counsel |

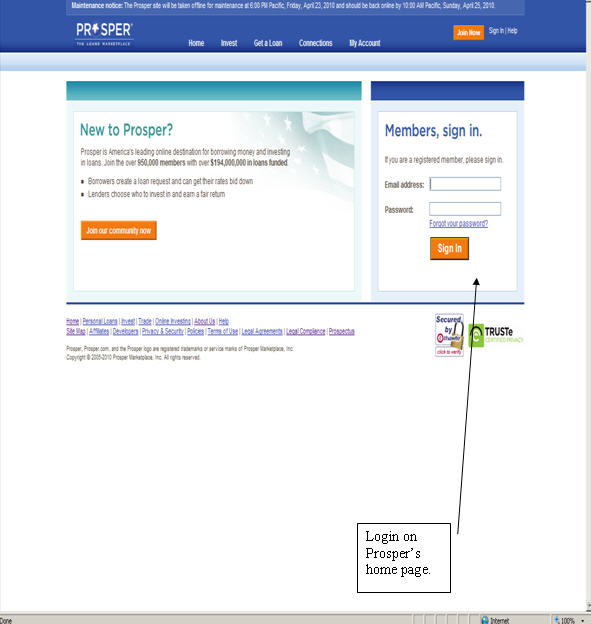

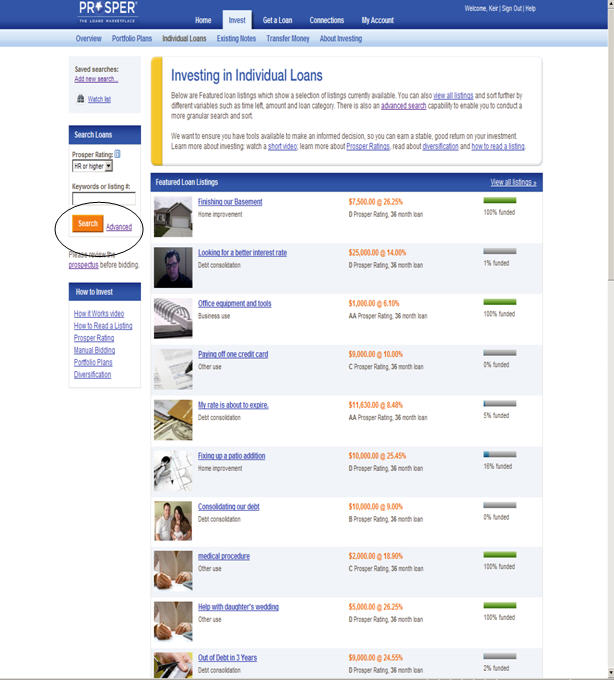

Login ---- -> Browse Notes ---- -->Advanced Search --- --> Add or Remove Criteria

Login ---- -> Browse Notes ---- -->Advanced Criteria -- (After Addition Additional Criteria)