Exhibit 2

| | | | |

| | | |  |

| | |

| | | | | 2012 Economic and Financial Document |

| | |

| | | | Section I: |

| | |

| | | | Italy’s Stability Programme |

| | |

The 2011 ECONOMIC AND FINANCIAL DOCUMENT is available on-line at the Internet address listed below: www.mef.gov.it www.dt.tesoro.it www.rgs.tesoro.it ISSN: 2239-5539 | |  | | |

Economic and Financial Document 2012

Section I:

Italy’s Stability Programme

Submitted by Prime Minister

and

Minister of the Economy and Finance

Mario Monti

Adopted by the Cabinet on 18 April 2012, endorsed by Parliament on 26 April

ECONOMICAND FINANCIAL DOCUMENT – ITALY’S STABILITY PROGRAMME

ITALY 2020: RIGOUR, GROWTH AND EQUITY

Let’s try to envision that in 2020 some 69 per cent of people between the ages of 24 and 65 years will have a job, almost 10 percentage points more than today. Let’s try to think that a woman will not have to face an obstacle course in attempting to make home life and career compatible, because there will be a modern parental leave system, an extensive network of accessible care structures for children and the elderly, and shops that are open during hours that will make it possible for her to manage her days according to her needs. Let’s imagine that the quality of essential public services in southern Italy is not systematically inferior to those in the rest of the country. Let’s contemplate being able to rely on an efficient, modern system of insurance against the risks of job loss, which covers all workers, regardless of the contract they have, and that the number of persons at risk of poverty is cut by 2.0 million with respect to 2010. Let’s imagine being able to start up a business activity without having to request authorisations and, if we’re under 30 years old, being able to start up a business with one euro in capital. In the event of business disputes, we can count on judicial proceedings that allow for concluding a civil court case in 394 days as in Germany, instead of the 1,210 days it takes today in Italy. Let’s imagine that at least one-third of the population between the ages of 30 and 34 has a university degree, also because there is increasingly less risk of dropping out of the school system in the early years of education, as occurs today with around 18.8 per cent of young people - one-third more than in Germany and France. Let’s imagine that it’s worthwhile for a young researcher to think about a career in Italy because investment in research has grown to 1.53 per cent of GDP and there are at least seven R&D jobs for every 1,000 inhabitants, as in France, Austria or Germany. Let’s imagine less polluted cities and less expensive utility bills, because Italy is on the cutting edge in energy efficiency. Let’s imagine citizens, workers and business people interacting with the public administration via the Internet, thanks to an ultra broadband connection accessible to 100 per cent of the population. And paying less in taxes because the government is more efficient and costs less. Meanwhile, the public debt has fallen below the threshold of 100 per cent of GDP, after having reached 120 per cent in 2012.

Reflecting on scenarios such as these and on the policy actions needed for realising them is not an abstract diversion. It is the essence of the exercise that Italy and the other EU Member States must complete each year in preparing a Stability Programme and a National Reform Programme as part of the Europe 2020 Strategy for intelligent, sustainable and inclusive growth.

Thinking about national economic policy within a European frame of reference and over the long term is one of the most important changes introduced into the European Union’s economic governance with the ‘European Semester’. Coordination of structural reforms among Member States of the Union is a necessary matter of fact. The European economies have a high degree of interdependence and the reforms of certain economies have an impact on others. Setting long-term objectives is instead a useful and pragmatic way of stimulating policy and public opinion to set targets toward the future we want for the country and for Europe, initiating work today so that this future can be realised.

| | |

| MINISTERODELL’ECONOMIAEOFTHE FINANZE | | |

| | III |

ECONOMICAND FINANCIAL DOCUMENT – ITALY’S STABILITY PROGRAMME

The Europe 2020 Strategy constitutes an integral part of the national agenda. On the one hand, it sheds light on the fundamental weaknesses of Italy’s economy that we have lived with for too long and that can no longer be tolerated. On the other hand, it sets long-term objectives that Italy must set in any case, even without the stimulus of Europe, in order to enable the economic and productive system to emerge stronger and reinforced from the crisis. None of these objectives is outside of Italy’s reach.

The Economic and Financial Document is thus a key step in the definition of national economic policy and represents an instrument for setting out a vision of how Italy must evolve in this decade and for plotting the path, year after year, of concrete reforms that can be verified in subsequent years.

v

The 2012 Economic and Financial Document, the second since the inauguration of the European Semester, has been drawn up against a distinct backdrop.

The financial crisis that hit Italy and the rest of Europe has seen some of its most difficult moments in the past months. Sovereign debt crisis, weakness in the financial sector and the slowdown of the international economy were intertwined, thereby causing a dangerous short circuit. The crisis steered Italy, with particular intensity, into a spiral that put the staying power of the economic and financial system at risk.

With this emergency, Parliament has instituted a Government in the national interest, supported by a broad majority of political parties that, despite their strong policy differences, have the general interest of the nation at heart, in a spirit of unity and collaboration among institutions. The experience of this Government originates from the urgency to act, but it is based on the awareness that it is not enough to focus on the short term to get over the critical phase. The flare-up of sovereign-risk premiums that led the country to the brink of a dramatic crisis is not the cause, but is the symptom of a greater malaise. The crisis originated from factors outside of the Italian economy that were linked to the European and international framework, but was furthered by the persistence of structural, fundamental weaknesses of our economy that had yet to be tackled.

It is for this reason that Italy has been hit harder by the crisis and is having difficulty emerging from it. At the end of 2011, the gross domestic product was still some five percentage points below where it was before the crisis. In the past two years, industrial production has recovered just over one-fifth of the loss experienced during the acute phase of the crisis, between 2008 and 2009. Household income has contracted by more than 4.0 per cent in real terms, while it rose during the same period, albeit only marginally, in Germany and France. The percentage of households experiencing economic hardship has risen. At the start of this year, the number of employed persons was still more than 600,000 below the peak level reached in April 2008. The crisis has had particularly hard repercussions on less educated and younger workers, workers with term contracts, and women. It has entailed a slowdown of credit to the private sector and in particular, credit to businesses, which has not yet been completely reversed.

In brief: Italy is today further away from its national objectives deriving from the Europe 2020 Strategy than when the Strategy was adopted two years ago.

| | |

| | MINISTERODELL’ECONOMIAEOFTHE FINANZE |

IV | | |

ECONOMICAND FINANCIAL DOCUMENT – ITALY’S STABILITY PROGRAMME

The message is clear. It is not possible to wait for the storm to pass and the current parenthesis to close. The crisis that we have been experiencing since 2008 can have a profound and long-term impact on Italy’s growth, even if a destructive shock has been avoided. The logic behind the Europe 2020 Strategy is that you do not tackle a structural crisis from a defensive position, with cyclical responses. It is necessary to instil a process of change at all levels, guided by clear objectives and by an idea of the future that we seek. For our country, this means tackling the critical aspects of the economic and productive system, which are well known, and defining the terms of a profound transformation.

For this reason, the Government has established an action plan based on two elements: fiscal consolidation and promotion of growth. And an agenda of reforms based on three underlying principles: rigour, growth, and equity.

The first sphere of action is fiscal consolidation. The public debt has reached its highest level since the start of the crisis. It is necessary to manage this heavy burden by outlining a gradual, but long-term, plan for its reduction. This is a compulsory decision, necessary to avoid jeopardising the country’s economic security, even at the cost of significant sacrifices to be made by individuals, households and businesses.

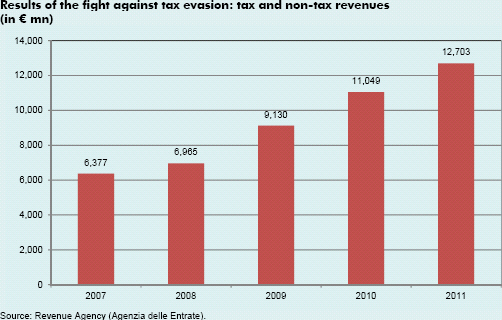

And it is because this financial rigour takes its toll on the entire nation, that it must be undertaken in an equitable fashion and have the smallest impact possible on growth potential. Although a substantial part of fiscal adjustment has inevitably been achieved by adjusting tax revenues, the measures have been implemented so as to be growth-oriented, to the extent possible, through a relative increase in taxation on consumption and real property, and a relative reduction of fiscal pressure on business activity and work. The commitment to fight unacceptable levels of tax avoidance and tax evasion in Italy is also based on equity. Tax evasion is a form of unfair competition between businesses, and a way in which dishonest citizens damage other citizens, triggering higher fiscal pressure for all taxpayers. For this reason the proceeds of the fight against tax evasion will need to be used for reducing tax rates in the future, as well.

In the medium term, debt reduction will need to rely increasingly on the reduction of current expenditure. From this standpoint, the spending review will play a key role as it will favour a higher quality of public expenditure in key sectors.

In order to be credible, debt reduction must be structural and isolated from decisional variability stemming from different political administrations. With regard to the first criterion, the pension reform which brings the retirement age in Italy to the highest level in Europe and the decision not to consider proceeds from the fight against tax evasion in estimates of government revenues are, indeed, structural factors. The second criterion is ensured by the commitment to a balanced budget to be sanctioned by the Constitution through amendment of Article 81, in line with the commitment undertaken in the Euro Plus Pact and the new ‘fiscal compact’, the international treaty that sets the rules for fiscal union between the Member States of the Euro Area.

| | |

| MINISTERODELL’ECONOMIAEOFTHE FINANZE | | |

| | V |

ECONOMICAND FINANCIAL DOCUMENT – ITALY’S STABILITY PROGRAMME

Still, the heart of Italy’s problem is how to get back to growth again. There is no reason to accept the fact that Italy has had a growth rate below the Euro Area average for more than 10 years. At the present time, growth cannot come from the expansionist stimuli of public spending. Nor can it be hoped that growth can be achieved by squeezing salaries and competing on price with emerging economies that have low labour costs and less protection of social rights.

The impulse to growth that will push Italy toward the Europe 2020 Strategy objectives will come from boosting the total factor productivity of the economy. In particular, this could be achieved by increasing efficiency, productivity and competitiveness in the currently more rigid structure.

Allowing more competition in the product and services market is fundamental. Experience shows that a more open market can lead to better services and lower costs, while also pushing productivity and thereby enhancing the value of the most dynamic and innovative businesses.

Liberalising the economy is a not an abstract principle, but a means for removing privileges and income arising from privileged positions. It helps to give more opportunity to do and to grow to whoever may have initiative without having inherited a certain profession or position.

The disconcerting growth of unemployment and the low level of employment, in particular of young people and women, point to the urgency of reforming the labour market, characterised by its injustices and a lack of order. It is a dual market in which workers with contracts without a termination date enjoy high levels of job security, while others with different types of contracts have modest prospects of improvement, little training and barely any job security. At present, the labour market is flexible only on the hiring side, and an all-encompassing unemployment protection system does not exist. It is necessary to reshape the labour market, as the Government has proposed with a legislative bill recently presented to Parliament, in order to help workers and businesses engage in the difficult phase of reorganisation and changing productive specialisation, and to tackle the dramatic problem of high unemployment among young people.

Tax regulations represent another fundamental part of the strategy for emerging from crisis and returning to growth. The fiscal system must be flexible, innovative and capable of giving incentives to investments in new sectors propelling growth. Tax regulations need to be simplified in order to make life easier for the honest citizen and taxpayer. These changes must also be accompanied by a public administration ever more efficient and consistent in its actions. A more transparent, result-oriented and streamlined administration will be able to make a more meaningful contribution to the nation’s economic productivity growth and will take less of a toll on the earnings of businesses and individuals.

Infrastructure investments can also provide a push to productivity. The Government has already freed up more than €22 billion within the Interministerial Committee for Economic Planning (CIPE) that will result in 180,000 new direct jobs, and another 100,000 indirect jobs. The ‘Cohesion Action Plan’ has begun the acceleration and requalification of investments of European Union structural funds concentrated in the southern regions of the country. It is also necessary to leverage the digital economy, which can generate new activities and help overcome territorial divides and the size limitations of Italian businesses. Furthermore, the Government is concerned about the access to credit for Italian businesses and it is determined to overcome the problem of payment delays stemming from the public administration. Broadening market accessibility is furthermore a primary objective for attracting more foreign investment to Italy.

| | |

| | MINISTERODELL’ECONOMIAEOFTHE FINANZE |

VI | | |

ECONOMICAND FINANCIAL DOCUMENT – ITALY’S STABILITY PROGRAMME

Prices, salaries, and costs matter, but so do the human and social capital available to the nation’s economy. Growth, as broadly defined, also depends on the capacity, the talents and the propensity to innovation of a nation’s researchers, workers and firms. Innovation, a skilled work force, and research are fundamental assets that allow firms to shift into high-technology sectors, or new markets such as those offered by the green or digital economy. Italy boasts significant strengths, examples of excellence in research, a quality education system, and firms that operate on the technological frontier. But looking at the situation from the perspective offered by the Europe 2020 Strategy, our country still invests too little in research, has an insufficient number of patents, and loses too much talent because of the high number of young people who emigrate abroad.

Social capital also constitutes a factor for the sustainable growth of an economy. It is thus necessary to break the vicious circle between corruption and the informal economy.

v

In past months, Italy has undertaken a considerable degree of reforms. The ‘Save Italy’, ‘Grow Italy’, ‘Simplify Italy’ decrees and the ‘Cohesion Action Plan’ have started to tackle structural weaknesses and have responded convincingly to the requests of European and international institutions. The analyses of this National Reform Programme demonstrate that the deregulation and simplification measures will have a cumulative positive effect on growth of 2.4 percentage points of GDP in 2020. Italy has secured its public accounts, and in 2013, will have a primary surplus equal to 3.9 per cent of GDP. Public debt is now on a gradual and long-term reduction path.

These sprint results have been realised through the collective effort of Parliament, the representatives of unions and of businesses, and the Government. But much remains to be done to overcome economic lags and deep-rooted weaknesses that have accumulated over the years. Getting back to growth is a lengthy undertaking, and much remains to be done. An agenda of the things to be done is set out in the final chapter of the National Reform Programme. The actions are concrete and wide-ranging, and they round out and enhance the initiatives of past months, having an impact on all key factors related to the competitiveness of the economic and productive system: furthering the opening of the market for goods and services; reshaping the labour market in line with the outlook for growth; investing in the value of education and innovation; revising the tax system; providing incentives for investments abroad and supporting exports; speeding up civil court proceedings; modernising the public administration; preventing and stifling corruption; and investing in transport infrastructure, the digital agenda and the green economy. Such a strategy needs to take into account the conditions of the backdrop of every area of the country, with particular attention to enhancing the value of the unused growth potential of the country’s southern regions.

There is still a brief, extraordinary window of opportunity that the country must not lose. The current situation still has its ups and downs, but is more favourable than in the recent past, as we have seen Italy’s capability of response and that of all its institutions. The situation of the Euro Area with respect to the financial markets shows signs of stabilisation and improvement, thanks to the pragmatic policy of the European Central Bank and the agreement reached at a European level for resolving the crisis in Greece. Important decisions have been made in order to complete the economic governance architecture, thus reinforcing measures of fiscal discipline and firewalls. The public debt inherited from the past remains a heavy burden for Italy to bear.

| | |

| MINISTERODELL’ECONOMIAEOFTHE FINANZE | | |

| | VII |

ECONOMICAND FINANCIAL DOCUMENT – ITALY’S STABILITY PROGRAMME

As indicated in the Stability Programme, the international cycle remains weak and uncertain. At a domestic level, growth cannot be expected to return until 2013. The lack of employment directly or indirectly affects almost one-half of Italian households. It is necessary to act with determination in order to complete the sequence of reforms and to enable the country to start up again, thus actively contributing to economic recovery. The year ahead must be a year of profound transformation for Italy, consistent with what has already occurred in past months.

v

In order to proceed without delay, we need to clear the field of some scepticism about the usefulness of the tool of reforms, scepticism coming from two erroneous perceptions: the first is the political timing of the reforms, and the second is the scope (of the economic and social interests) of the reforms.

With reference to the first aspect, according to some opinions it is risky to carry out structural reforms when the economy is contracting. In the short term, the reforms entail additional costs, whereas the benefits are produced only over the medium/long term. International experience demonstrates that the risk is true only in part and that it can be mitigated. Reforms do indeed require patience, but they will pay off. The most recent comparative analyses done by multilateral organisations show that the benefits of reforms may be seen earlier than expected if the measures are concentrated within a limited time period, and constructed with proper logic and over a time sequence. The Government’s action will thus be to link liberalisation and simplification measures to the reform of the labour market and the revision of the taxation system, combining them with measures to free up and to requalify investment in infrastructures, improve the effectiveness of education, strengthen childcare and care of the elderly, and promote opportunities for young people. Coordination among these measures will create virtuous circles mitigating the negative effects and allowing the positive effects to emerge more rapidly. Concentrating the reforms sends a clear signal to residents, consumers, businesses and investors, triggering a positive circuit of expectations that fuels growth.

The other aspect regards the scope of interests affected by the reforms. Reforms are difficult to pass because they affect interests concentrated in categories with strong political representation and instead bring advantages to a broad base of unorganized interests, such as consumers, or young people, or even future generations. This is an issue to that should be dealt with not in terms of political tactic, but in terms of equity. The sacrifices required for reducing the public debt and returning to economic must be distributed equitably in order to be sustainable. For this reason, the reform measures presented in past months have been conceived as systematic measures that have an effect on a wide range of sectors and issues. In this way, the weight of adjustment is not unduly put on any specific category or social group, but everyone is asked to accept a sacrifice in terms of their own particular interest in order to have advance in the general interest. The greater equity there is, the greater is the willingness to accept changes, even if difficult.

Implementing the Europe 2020 Strategy requires national reforms. But it is necessary for the European environment to supply the Member States with the best backdrop possible in order to ensure national reforms are effective and reward sacrifices made. For this reason, the Government immediately made its best effort to contribute directly and substantially to the Union’s policy orientation, so that there would be no priority higher than growth on the Union’s agenda. The Euro Area crisis is the product of short-sighted attitudes toward public finance, in particular during periods of expansion. But it was also caused by a deficit in both reforms and economic policies for growth. Focusing on growth and on its most important engine - integration of the single market - will produce the energy necessary to drive Europe out of the sovereign debt crisis.

| | |

| | MINISTERODELL’ECONOMIAEOFTHE FINANZE |

VIII | | |

ECONOMICAND FINANCIAL DOCUMENT – ITALY’S STABILITY PROGRAMME

Finally, one can ask if the 2020 Agenda is a technocratic agenda or if it has an inspiring vision of society and the market. For some, structural reforms are needed in order to preserve the European social model with its achievements in the face of a world that is changing. For others, reforms need to signal the point of departure from that model, which is outdated and financially unsustainable. The less visible, but essential, thread that links the reforms of the Europe 2020 Strategy together is the construction of a highly competitive social market economy at a European level, and thus an economy that creates more sustainable employment. This is the fundamental objective that the Lisbon Treaty assigned to the European Union. Getting growth started again within a model of stable public finance is the way to build a modern social market economy.

The 2012 National Reform Programme is one step in a process that will repeat itself every year until 2020. The reforms presented in this document inaugurate a series of projects, whose work must continue in the years to come. Growth requires planning continuity and consistency over time. In this regard, the Europe 2020 Strategy has one strong advantage. It is a reference framework that will remain valid over the long term, even in the face of changing governments with distinct programmatic visions. It is a stable framework that can be filled with somewhat different contents depending on specific views about concrete policies, but its orientation toward reaching the 2020 objectives for Italy does not change.

A Member State which has a clear and ambitious National Reform Programme consistent with public finance targets as identified in its Stability Programme, which has political parties that share such a strategy and believe it to be an integral part of their policies, and thus which commit to respecting it, even in the future, and finally, a Member State which has a government focused on the implementation of the programme of structural reforms and is supported by Parliament, the representatives of unions and of businesses, and the public at large, is a Member State that is credible and predictable, that contributes to guiding Europe, and that can be deemed to be increasingly reliable by the markets, but even more so, by its citizens.

This Economic and Financial Document proposes a vision for the development of the country and a way for moving ahead. I hope that it offers a stimulus for fuelling solid debate among political parties, representatives of unions and of businesses, and autonomous territorial entities, about the challenges that await the nation and about the best solutions for creating more growth, more employment and more equity.

| | |

| | Mario Monti |

| |

| | President of the Council of Ministers Minister of Economy and Finance |

| | |

| MINISTERODELL’ECONOMIAEOFTHE FINANZE | | |

| | IX |

ECONOMICAND FINANCIAL DOCUMENT – ITALY’S STABILITY PROGRAMME

| | |

| | MINISTERODELL’ECONOMIAEOFTHE FINANZE |

X | | |

ECONOMICAND FINANCIAL DOCUMENT –ITALY’S STABILITY PROGRAMME

TABLE OF CONTENTS

| | | | |

| I. | | OVERALL FRAMEWORKAND ECONOMIC-POLICY OBJECTIVES | | 1 |

| | |

| II. | | MACROECONOMIC SCENARIO | | 3 |

| II.1 | | The international scenario | | 3 |

| II.2 | | Italy’s economy | | 4 |

| II.3 | | Impact of key reforms on growth | | 10 |

| Box | | National accounts revisions | | |

| | |

| III. | | NET BORROWINGAND PUBLIC DEBT | | 12 |

| III.1 | | The path to a turnaround – Excessive Deficit Procedure | | 12 |

| III.2 | | Financial Impact of key Reforms | | 18 |

| III.3 | | The cyclically adjusted balance | | 19 |

| III.4 | | Public debt | | 21 |

| III.5 | | Trend of debt-to-GDP ratio | | 27 |

| Box | | The expenditure rule | | |

| | |

| IV. | | SENSITIVITY ANALYSIS | | 29 |

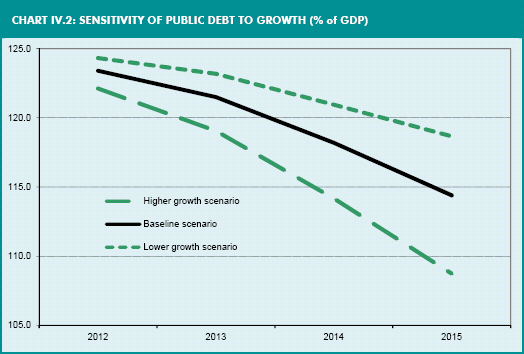

| IV.1 | | Sensitivity to economic growth | | 29 |

| IV.2 | | Sensitivity to interest rates | | 32 |

| | |

| V. | | SUSTAINABILITYOF PUBLIC FINANCES | | 35 |

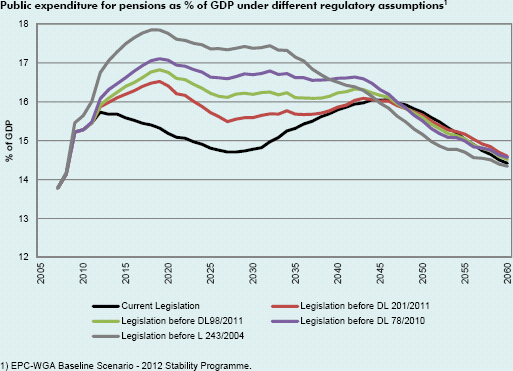

| V.1 | | The impact of population ageing on public expenditure | | 35 |

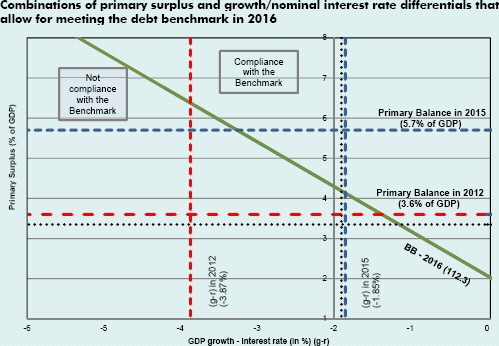

| V.2 | | Debt sustainability | | 43 |

| V.3 | | Analysis of the sensitivity of public-debt dynamics over the long term | | 45 |

| V.4 | | The impact of pension reform on sustainability | | 50 |

| V.5 | | Other relevant factors | | 51 |

| Box | | The reform of the pension system | | |

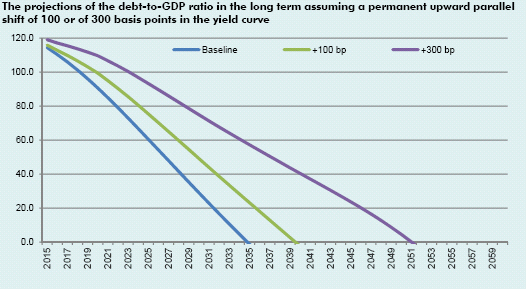

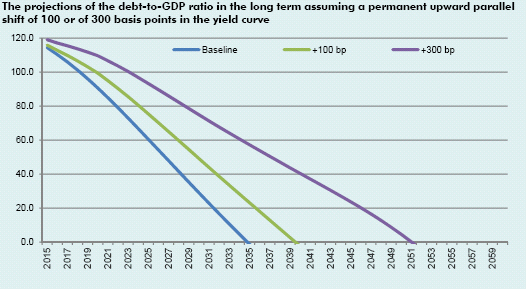

| Box | | Sensitivity of the debt to interest rates in medium/long term | | |

| Box | | Guarantees granted by the State | | |

| Box | | The debt rule | | |

| | |

| MINISTERODELL’ECONOMIAEDELLE FINANZE | | |

| | XI |

ECONOMICAND FINANCIAL DOCUMENT –ITALY’S STABILITY PROGRAMME

| | | | |

| VI. | | QUALITYOF PUBLIC FINANCES | | 59 |

| VI.1 | | Actions taken and strategy for 2013-2015 | | 59 |

| Box | | Macroeconomic impact of fiscal consolidation measures adopted in 2011 | | |

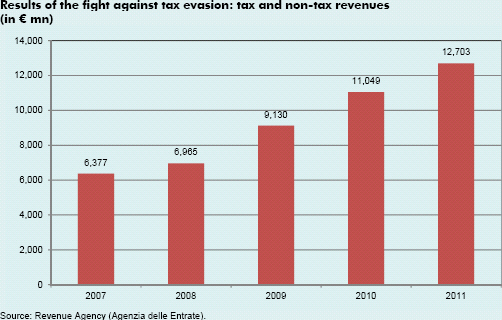

| Box | | The fight against tax evasion | | |

| Box | | International outlook and policies for cooperation in development | | |

| | |

| VII. | | INSTITUTIONAL ASPECTSOF PUBLIC FINANCES | | 71 |

| VII.1 | | Fiscal rules | | 71 |

| VII.2 | | Strengthening of fiscal framework | | 74 |

| | |

| | MINISTERODELL’ECONOMIAEDELLE FINANZE |

XII | | |

ECONOMICAND FINANCIAL DOCUMENT –ITALY’S STABILITY PROGRAMME

TABLES

| | |

| Table I.1 | | Public finance indicators: objectives (% of GDP) |

| |

| Table II.1 | | Base assumptions |

| |

| Table II.2a | | Macroeconomic prospects |

| |

| Table II.2b | | Prices |

| |

| Table II.2c | | Labour market developments |

| |

| Table II.2d | | Sector accounts |

| |

| Table II.3 | | Overall macroeconomic effects of the structural reforms of Decree-Law No. 1/2012 and Decree-Law No. 5/2012 (percentage deviation compared with baseline simulation) |

| |

| Table II.4 | | Macroeconomic effects of the individual structural reform measures contained in Decree-Law No. 1/2012 and Decree-Law No. 5/2012 (percentage deviation compared with baseline simulation) |

| |

| Table III.1 | | Differences with respect to previous Stability Programme |

| |

| Table III.2 | | The path to a turnaround (% of GDP) |

| |

| Table III.3 | | General Government budgetary prospects |

| |

| Table III.4a | | General Government revenues: discretionary and based on unchanged policies |

| |

| Table III.4b | | Expenditures to be excluded by expenditure rule |

| |

| Table III.5 | | General Government account based on unchanged policies |

| |

| Table III.6 | | State Sector – Public Sector - cash balances (in € mn and % of GDP) |

| |

| Table III.7 | | Financial impact of NRP measures (in € mn) |

| |

| Table III.8 | | Cyclical developments (% of GDP) |

| |

| Table III.9 | | Public debt determinants (% of GDP) |

| |

| Table III.10 | | General Government debt by sub-sector (in € mn and % of GDP) |

| |

| Table IV.1 | | Sensitivity to GDP growth (percentage values) |

| |

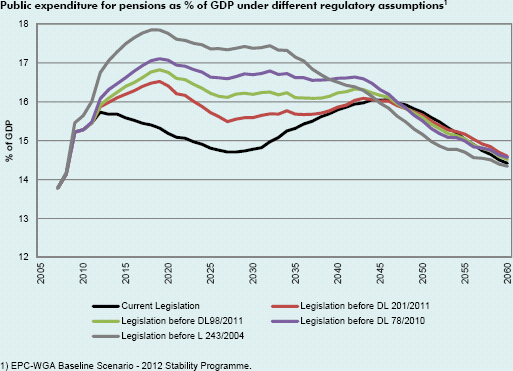

| Table V.1 | | Public expenditure for pensions, healthcare, long-term care, education and unemployment compensation (2005-2060) |

| |

| Table V.2 | | Long-term sustainability indicators |

| |

| Table V.3 | | Intervention to support financial institutions (in € mn) |

| |

| Table V.4 | | Intervention to support financial institutions (% of GDP) |

| |

| Table VI.1 | | Cumulative impact of 2011 legislation on General Government’s net borrowing (before netting out induced effects; in € mn) |

| |

| Table VI.2 | | Cumulative impact of 2011 budget packages on General Government’s net borrowing (before netting out induced effects; in € mn) |

| |

| Table VI.3 | | Cumulative impact of 2011 budget packages on General Government’s net borrowing by sub-sector (before netting out induced effects; in € mn) |

| |

| Table VI.4 | | Impact of Decree Law No. 98/2011 - converted by Law No. 111/2011 (before netting out induced effects; in € mn) |

| |

| Table VI.5 | | Impact of Decree Law No. 138/2011 - converted by Law No. 148/2011 (before netting out induced effects; in € mn) |

| |

| Table VI.6 | | Impact of Law No. 183/2011 - 2012-2014 Stability Law (before netting out induced effects; in € mn) |

| |

| Table VI.7 | | Impact of Decree-Law No. 201/2011 - converted by Law No. 214/2011 (before netting out induced effects; in € mn) |

| |

| Table VI.8 | | Public finance policy scenario for 2012-2015 (% of GDP) |

| | |

| MINISTERODELL’ECONOMIAEDELLE FINANZE | | |

| | XIII |

ECONOMICAND FINANCIAL DOCUMENT –ITALY’S STABILITY PROGRAMME

CHARTS

| | |

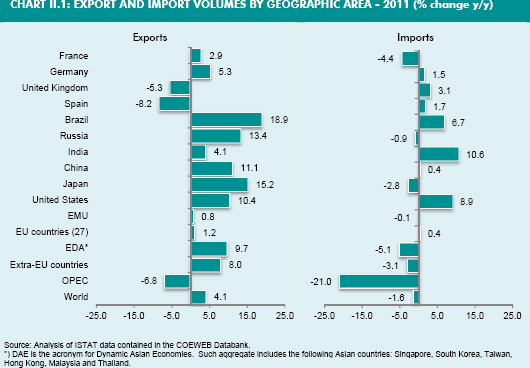

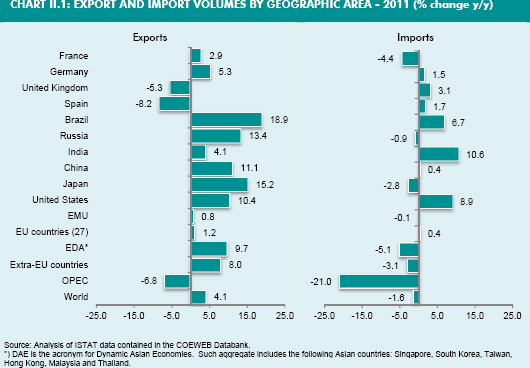

| Chart II.1 | | Export and import volumes by geographic area 2011 (% change y/y) |

| |

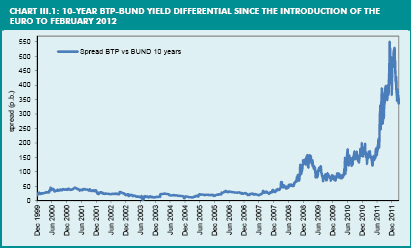

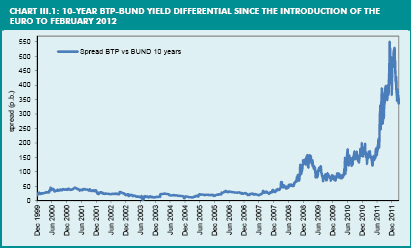

| Chart III.1 | | 10-year BTP-bund yield differential since the introduction of the euro to February 2012 |

| |

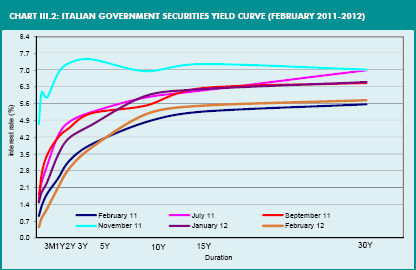

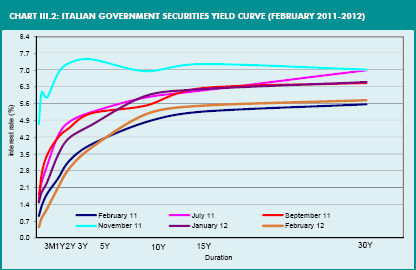

| Chart III.2 | | Italian Government securities yield curves (February 2011-2012) |

| |

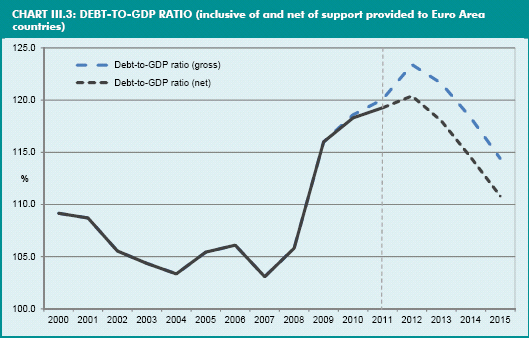

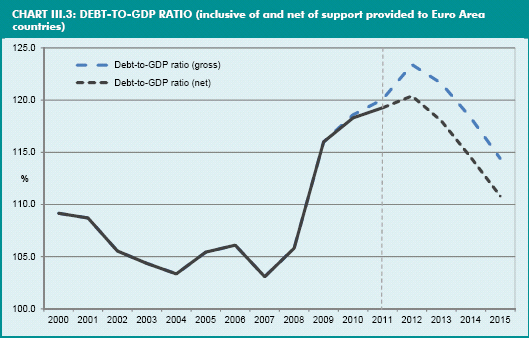

| Chart III.3 | | Debt-to-GDP ratio (inclusive of and net of support provided to Euro Area countries) |

| |

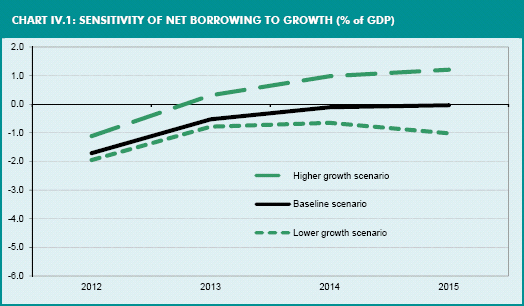

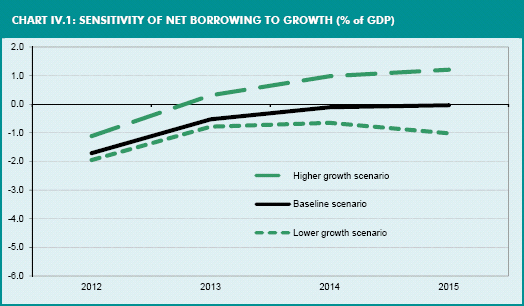

| Chart IV.1 | | Sensitivity of net borrowing to growth (% of GDP) |

| |

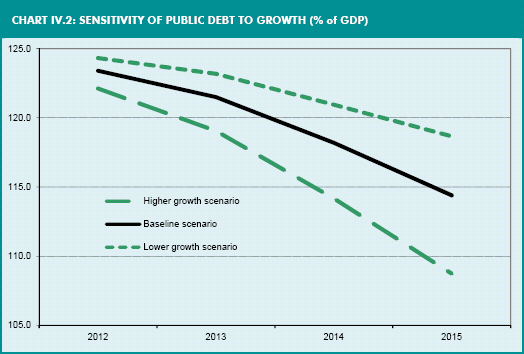

| Chart IV.2 | | Sensitivity of public debt to growth (% of GDP) |

| |

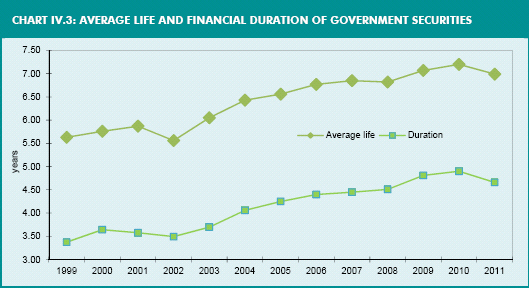

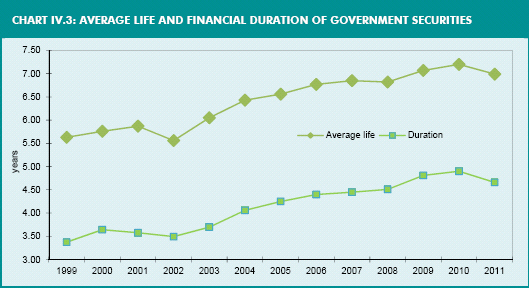

| Chart IV.3 | | Average life and financial duration of Government securities |

| |

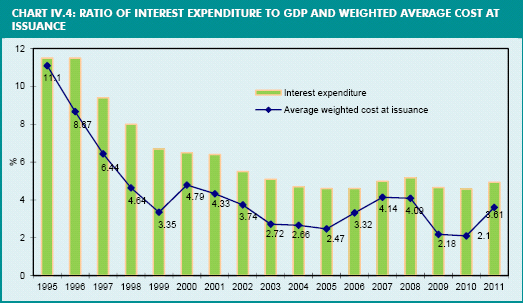

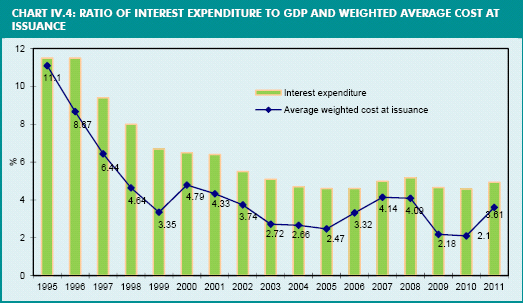

| Chart IV.4 | | Ratio of interest expenditure to GDP and weighed average cost at issuance |

| |

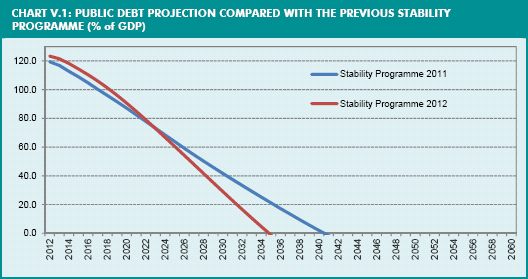

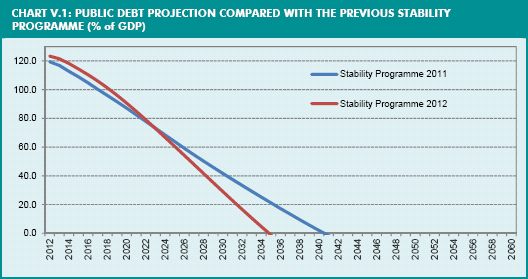

| Chart V.1 | | Public debt projection compared with the previous Stability Programme (% of GDP) |

| |

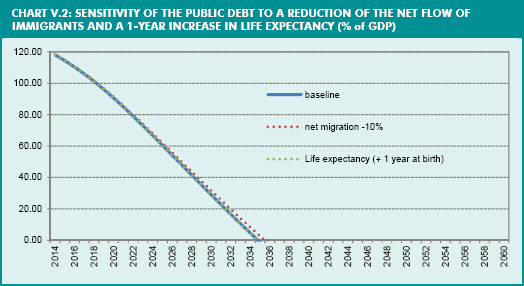

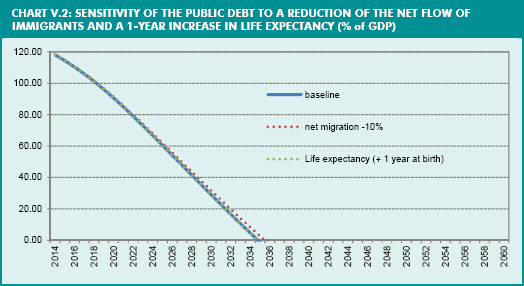

| Chart V.2 | | Sensitivity of the public debt to a reduction of the net flow of immigrants and a 1-year increase in life expectancy (% of GDP) |

| |

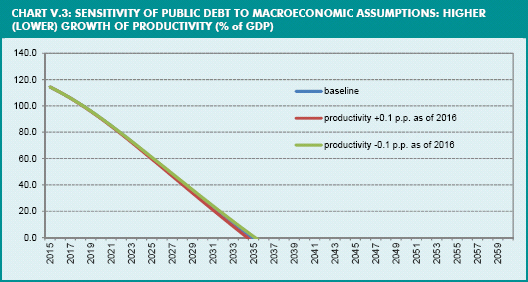

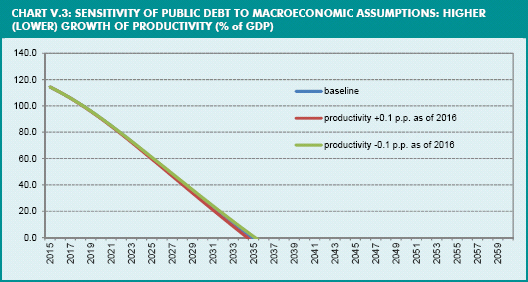

| Chart V.3 | | Sensitivity of public debt to macroeconomic assumptions: higher (lower) growth of productivity (% of GDP) |

| |

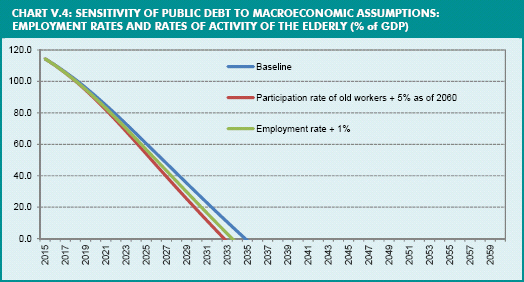

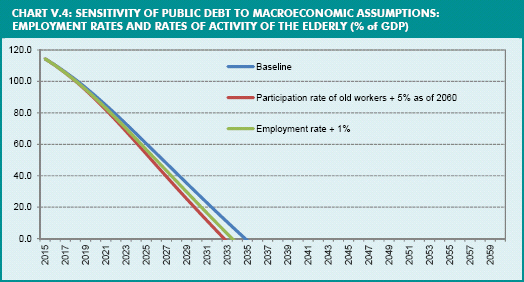

| Chart V.4 | | Sensitivity of public debt to macroeconomic assumptions: employment rates and rates of activity of the elderly (% of GDP) |

| |

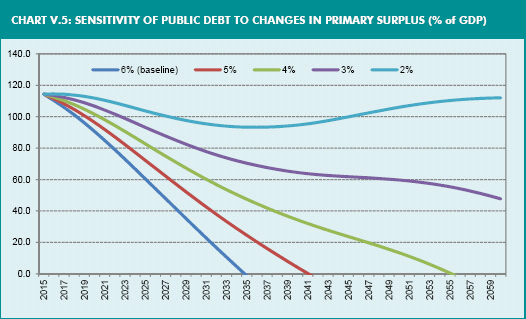

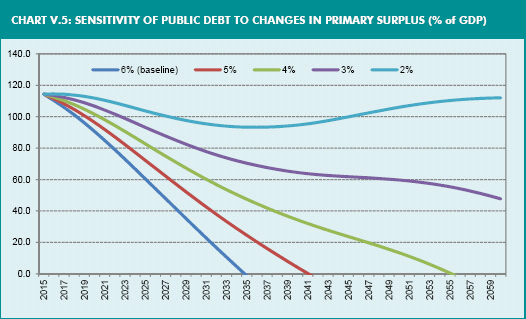

| Chart V.5 | | Sensitivity of public debt to changes in primary surplus (% of GDP) |

| |

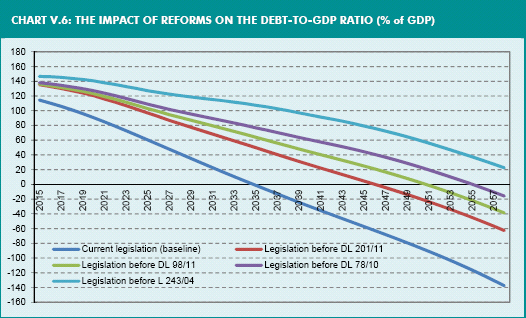

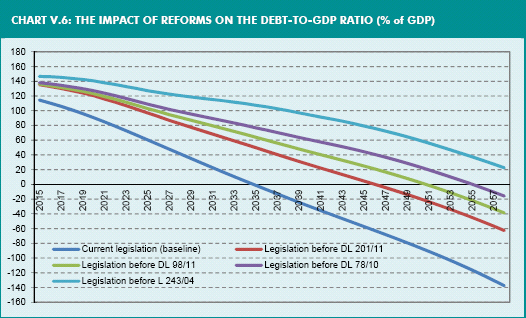

| Chart V.6 | | The impact of reforms on the debt-to-GDP ratio (% of GDP) |

| |

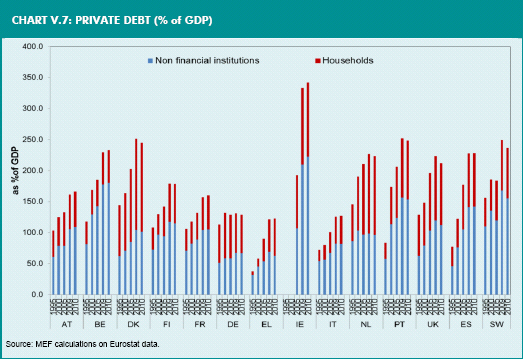

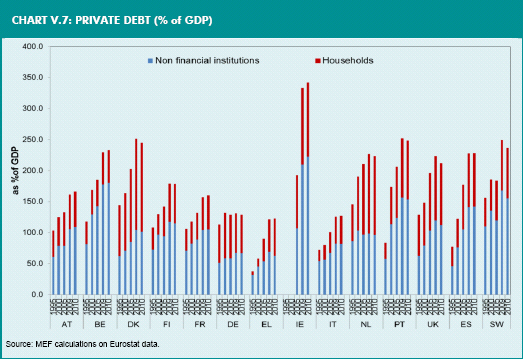

Chart V.7 | | Private debt (% of GDP) |

| | |

| | MINISTERODELL’ECONOMIAEDELLE FINANZE |

XIV | | |

ECONOMICAND FINANCIAL DOCUMENT – ITALY’S STABILITY PROGRAMME

| I. | OVERALL FRAMEWORK AND ECONOMIC-POLICY OBJECTIVES |

The moderate recovery of Italy’s economy in the first half of 2011 was weakened by the slowdown of the global economic cycle and by growing tensions in the sovereign debt market for the Euro Area. In 2011, real GDP growth was 0.4 per cent, penalised by the recession in the final two quarters of the year. Therefore, during the current cyclical phase, the objective of fiscal consolidation must be considered equally with the growing need for providing a new impulse to economic recovery.

Budget rigour, growth and equity are the three pillars on which the Government’s strategy is based. These objectives coincide fully with those behind the renewed governance of Europe.

In 2011, the action of rebalancing of the public accounts was pursued with determination, with a view of achieving a balanced budget; such action required the adoption of a series of corrective measures, also in view of the deterioration of economic growth prospects and the renewal of tensions in the financial markets.

| | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | |

| TABLE I.1: PUBLIC FINANCE INDICATORS: OBJECTIVES (% of GDP) | | | | | | | | | | |

| | | | | | |

| | | 2010 | | | 2011 | | | 2012 | | | 2013 | | | 2014 | | | 2015 | |

UPDATED POLICY SCENARIO | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | |

Net borrowing | | | -4.6 | | | | -3.9 | | | | -1.7 | | | | -0.5 | | | | -0.1 | | | | 0.0 | |

Net structural borrowing (1) | | | -3.6 | | | | -3.6 | | | | -0.4 | | | | 0.6 | | | | 0.6 | | | | 0.4 | |

Structural change | | | -0.4 | | | | 0.0 | | | | -3.2 | | | | -1.0 | | | | 0.0 | | | | 0.2 | |

Primary surplus | | | 0.0 | | | | 1.0 | | | | 3.6 | | | | 4.9 | | | | 5.5 | | | | 5.7 | |

Primary structural surplus (1) | | | 1.0 | | | | 1.3 | | | | 4.9 | | | | 6.1 | | | | 6.2 | | | | 6.1 | |

Public debt | | | 118.6 | | | | 120.1 | | | | 123.4 | | | | 121.5 | | | | 118.2 | | | | 114.4 | |

Public debt (net of EU Area financial support) (2) | | | 118.3 | | | | 119.2 | | | | 120.3 | | | | 117.9 | | | | 114.5 | | | | 110.8 | |

| | | | | | |

MEMO: Report to Parliament (3) | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | |

Net borrowing | | | -4.6 | | | | -3.8 | | | | -1.2 | | | | 0.1 | | | | 0.4 | | | | | |

Structural net borrowing (1) | | | -3.5 | | | | -3.2 | | | | -0.1 | | | | 1.1 | | | | 1.0 | | | | | |

Structural change | | | -0.5 | | | | -0.3 | | | | -3.1 | | | | -1.2 | | | | 0.1 | | | | | |

Public debt (2) | | | 118.4 | | | | 119.8 | | | | 120.1 | | | | 117.5 | | | | 113.9 | | | | | |

| 1) | Net of one-off measures and the cyclical component. Estimates prepared on the basis of national accounting data available as of December 2011. |

| 2) | Net of direct loans to Greece, Italy’s portion of ESFS liabilities and Italy’s portion of ESM capital for the years from 2010 to 2015. |

| 3) | The projected data have not been published. |

As was the case in previous years, the budget law referred to the years of 2011-2014 was anticipated in the summer months, with the adoption of two specific budget packages: the first package in July1 was aimed at achieving a balanced budget in 2014, as targeted in the 2011 Economic and Financial Document (DEF); the second package in August2 was designed to move forward the achievement of a balanced budget to 2013 and to maintain that target in subsequent years. Altogether, the measures guaranteed a net correction of net borrowing by 2014 equal to approximately €60.0 billion, or 3.4 per cent

| 1 | Decree-Law No. 98/2011, converted by Law No. 111/2011. |

| 2 | Decree-Law No. 138/2011, converted by Law No. 148/2011. |

| | |

| MINISTERODELL’ECONOMIAEDELLE FINANZE | | |

| | 1 |

ECONOMICAND FINANCIAL DOCUMENT – ITALY’S STABILITY PROGRAMME

of GDP. With the Stability Law approved in December for the years 2012-2014, a different allocation of resources was established without altering the public finance balances3. At year end, in view of a further weakening of the macroeconomic scenario and a drastic deterioration of the European sovereign debt crisis, the new Government adopted an additional budget package4 which provided for a further correction of net borrowing by 2014 of the amount of €21 billion, or 1.4 per cent of GDP, so as to guarantee the achievement of a balanced budget in 2013. Altogether, the budget packages approved during 2011 will lead to a structural correction of €48.9 billion in 2012, or 3.1 per cent of GDP; the comparable figure for 2014 is €81.3 billion, or roughly 4.9 per cent of GDP.

Subsequent to December, Italy witnessed a further deterioration of economic conditions, but also a significant reduction in yields on government securities. Considering this latter development along with the measures already adopted and enacted into law, the Government substantially confirms the path to financial turnaround, as traced at year end : net borrowing falls well below the 3.0 per cent threshold of reference in 2012 and gradually decreases in subsequent years, making it possible to reach a balanced budget in structural terms in 2013.

The structural deficit is expected to contract by 3.2 percentage points in 2012 to reach a surplus of 0.6 per cent of GDP in 2013, thereby broadly surpassing the medium-term objective (MTO). In subsequent years, the structural balance is maintained well above the MTO.

The primary surplus rises in nominal terms, reaching 5.7 per cent of GDP in 2015, thus significantly increasing with respect to the 1.0 per cent recorded for 2011.

Fiscal consolidation measures have been accompanied by the adoption of various reforms5 aimed at removing the main obstacles that have compressed Italy’s growth potential. Such reforms are outlined in the National Reform Programme which is presented with the Stability Programme, in line with the stipulation for closer coordination of European Union economic policies as of 2011, with the inauguration of the European Semester.

| 3 | The Stability Law (Law No. 183/2011) provided for the use of resources under the Fund for Structural Economic-Policy Actions (ISPE) with Decree-Law No. 98 and Decree-Law No. 138 of 2011 and defined spending cuts for the Ministries as established by the decrees. |

| 4 | Decree-Law No. 201/2011, converted by Law No. 214/2011. |

| 5 | Decree-Law No. 201/2011, converted by Law No. 214/2011; Decree-Law No.1/2012, converted by Law No. 27/2012 and Decree-Law No. 5/2012, converted by Law No. 35/2012. |

| | |

| | MINISTERODELL’ECONOMIAEDELLE FINANZE |

2 | | |

ECONOMICAND FINANCIAL DOCUMENT – ITALY’S STABILITY PROGRAMME

| II. | MACROECONOMIC SCENARIO |

| II.1 | THE INTERNATIONAL SCENARIO |

The growth of the global economy slowed in 2011, with GDP estimated to have increased by 3.6 per cent and trade flows by 6.1 per cent. A disparity in growth continues to be evident between (i) the world’s developed nations and (ii) emerging markets and recently industrialised countries, with the latter having much higher growth rates and higher inflationary pressures.

The assumptions about growth of the global economy in 2012 have been revised downward to the present level of 3.1 per cent, while the rate of expansion of world trade has been scaled back to the current level of 3.4 per cent. Even though the international backdrop appears to have become more favourable in recent months, there are still elements of uncertainty regarding the future. Developed countries have high levels of indebtedness, the reduction of which will require restrictive fiscal policies over the medium term. In addition, developed economies could be affected by lower growth in the emerging markets. The prices of energy, food and industrial commodities remain at high levels, and there are continuing risks that geopolitical tensions may push up the prices even further, thereby limiting the economic recovery.

Economic growth in the Euro Area weakened overall in 2011, to the point of moving into negative territory in terms of the year-on-year change in GDP for the final quarter of the year. The governments of European countries decided to move forward the implementation of the European Stability Mechanism (ESM) to the first half of 2012. The European Central Bank has contributed to reducing financial market tensions by easing the monetary policy rate to 1.0 per cent and, more importantly, by undertaking two refinancing operations of the banking system over a three-year period and significantly expanding the range of financial assets eligible as collateral for transactions financed through the central bank.

In the United States, the economy gradually improved in 2011, with the momentum continuing into the first months of 2012. The labour market witnessed a sizeable reduction in the unemployment rate, despite some uncertainty in recent months, and inflation appears poised to remain under control. Instead, difficulties in the property market continue. The Federal Reserve Bank has announced that it will maintain, with all probability, an extremely accommodating monetary policy through the end of 2014.

In Japan, the economic recovery that took shape in the second half of 2011 came to an abrupt halt following the slowing of the global economy. The Bank of Japan set a medium-long-term inflation target of between 0 and 2.0 per cent, while also establishing a short-term target of 1.0 per cent.

| | |

| MINISTERODELL’ECONOMIAEDELLE FINANZE | | |

| | 3 |

ECONOMICAND FINANCIAL DOCUMENT – ITALY’S STABILITY PROGRAMME

The moderate recovery of Italy’s economy in the first half of 2011 was weakened by the slowdown of the global economic cycle and by growing tensions in the sovereign debt market for the Euro Area. Financial strains led to a sizeable increase in the spread between the yields on Italian and German ten-year government securities, reaching the highest level since the introduction of the euro (more than 5.5 percentage points). Though spreads later decreased significantly, falling below 3.0 percentage points, they have risen again in recent weeks.

In 2011, Italy’s economic activity grew by 0.4 per cent, decelerating due to the recession in the final two quarters of the year. The figure is slightly below the official 0.6 per cent estimate contained in the 2011 Report to Parliament presented at the start of December. GDP growth was sustained by net exports, which provided a positive contribution of 1.4 percentage points. Gross fixed investment and the change in inventories subtracted from GDP growth 0.4 and 0.5 percentage points, respectively. The contribution of final consumption to growth was nil.

The buoyant increase of exports proved significant (5.6 per cent) despite the appreciation of the euro. The increase in imports was instead modest (0.4 per cent) due to the weakening of domestic demand in the second half of the year.

Domestic demand

In 2011, gross fixed investment contracted significantly (-1.9 per cent). The drop was even more pronounced in the construction sector (-2.8 per cent) where an adjustment process is now in progress. The decline reported in machinery and equipment (-1.5 per cent) was instead offset by the increase in investments in transport equipment (1.5 per cent).

The growth of household spending was modest (0.2 per cent), and was impacted by both the limited increase in disposable income and the acceleration of inflation. A shift in the composition of household spending was observed in favour of services (1.6 per cent) to the detriment of the consumption of goods (-0.9 per cent).

Italian residents’ purchases abroad fell by 2.2 per cent against a 2.9 per cent increase in the spending of non-residents in Italy. Public expenditure fell by 0.9 per cent1 in line with fiscal consolidation measures.

In the labour market, the recovery of employment that began at the end of 2010 was weakened due to the slowdown of the economic cycle. On the whole, the year of 2011 yielded mixed results. Employment began to grow again, albeit modestly, after two years of contraction, while the number of employed reported by the Labour Force Survey was up by 0.4 per cent (with the increase in terms of full-time equivalents (FTEs) equal to 0.1 per cent). At a sector level, the increase was more dynamic in the industrial sector (excluding construction) and private services, contrasting a decrease in the construction sector. The labour supply also gained momentum, rising by 0.4 per cent. The unemployment rate averaged 8.4 per cent, remaining unchanged with respect to 2010.

| 1 | In nominal terms, the reduction of public expenditure is 1.0 per cent. |

| | |

| | MINISTERODELL’ECONOMIAEDELLE FINANZE |

4 | | |

ECONOMICAND FINANCIAL DOCUMENT – ITALY’S STABILITY PROGRAMME

The hours authorised for the wage-supplementation scheme (CIG) in 2011 decreased by approximately 19 per cent when compared with 2010, even though they remain at high levels (roughly 973 million hours). The ordinary CIG was reduced by 33 per cent, whereas the extraordinary and exceptional (in deroga) CIG fell to a more limited extent (-13 per cent and -14 per cent, respectively). The number of hours actually utilised by businesses (475 million hours) amounted to approximately 48 per cent of the hours authorised.

Despite a decelerating cost of labour, unit labour costs rose with respect to 2010 due to setbacks in productivity. The industrial sector (excluding construction) and the construction sector reported the highest increases in unit costs.

With reference to price developments, the GDP deflator rose by 1.3 per cent, while the consumption deflator was 2.7 per cent higher, reflecting increased prices for imported goods and services.

The harmonised index of consumer prices (HICP) rose by an average of 2.9 per cent in 2011, compared with 1.6 per cent for the prior year. Core inflation was 2.2 per cent higher, compared with 1.5 per cent in 2010.

On average, the harmonised index of prices for 2011 is 0.2 percentage points above the Euro Area average, with the variance essentially due to the timing with which the price increases in the more volatile components (energy and fresh food products) incorporate the trend of quotations on international markets. Core inflation reflects a higher differential (0.5 percentage points), which can be traced to the trend reported for non-energy durable goods for industry (whose prices grew by more than 1.5 percentage points over the Euro Area average) and services (0.7 percentage points).

NATIONAL ACCOUNTS REVISIONS

On 2 March 2012, ISTAT published ordinary revisions to 2009-2010 data, along with the publication of estimates for the 2011 annual accounts. The table below shows the differences between the two series of data for the main aggregates of GDP, and figures for prices and employment. The new estimates entail a downward revision of real GDP growth by 0.4 percentage points for 2009, with the final figure being -5.5 per cent; the change is mostly attributable to a sharper decrease in investments in machinery and equipment with respect to the previously published estimate. Final consumption was also revised downward due to a more limited increase in expenditure of public administrations which partially offset the slightly upward revision of expenditure of non-profit institutions serving households (NPISH). Economic growth for 2010 was revised upward by 0.3 percentage points compared with the previous estimate, to a total of 1.8 per cent. The revision resulted in a more positive variation in investment in machinery and equipment against a downward revision in the construction sector. The growth of household spending has been pegged at 1.2 per cent, improving by 0.2 percentage points. The revisions also affected exports, whose growth was lowered by 0.6 percentage points to 11.6 per cent. The nominal GDP growth rate was lowered by 0.4 percentage points in 2009, to -3.5 per cent, and increased in 2010 by 0.3 percentage points, to 2.2 per cent.

In October 2011, the national accounts data were revised in line with the new classification of economic activities (NACE II 2007) and the adoption of the European statistical classification of products by economic activities (CPA 2008).

| | |

| MINISTERODELL’ECONOMIAEDELLE FINANZE | | |

| | 5 |

ECONOMICAND FINANCIAL DOCUMENT – ITALY’S STABILITY PROGRAMME

Comparison between current and previous ISTAT series

| | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | |

| | | 2009 | | | 2010 | | | 2011 | |

| | | CURRENT | | | PREVIOUS | | | CURRENT | | | PREVIOUS | | | CURRENT | |

ITALY MACROECONOMIC DATA (VOLUMES) | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | |

GDP | | | -5.5 | | | | -5.1 | | | | 1.8 | | | | 1.5 | | | | 0.4 | |

Imports | | | -13.4 | | | | -13.4 | | | | 12.7 | | | | 12.7 | | | | 0.4 | |

National final consumption | | | -1.0 | | | | -0.9 | | | | 0.7 | | | | 0.6 | | | | 0.0 | |

- Household consumption | | | -1.6 | | | | -1.6 | | | | 1.2 | | | | 1.0 | | | | 0.2 | |

- Public consumption | | | 0.8 | | | | 1.0 | | | | -0.6 | | | | -0.5 | | | | -0.9 | |

- NPISH consumption | | | 2.3 | | | | 2.2 | | | | -0.4 | | | | 1.0 | | | | 0.9 | |

Gross fixed investment | | | -11.7 | | | | -11.7 | | | | 2.1 | | | | 2.4 | | | | -1.9 | |

- Machinery and equipment | | | -16.1 | | | | -15.3 | | | | 13.9 | | | | 12.6 | | | | -1.5 | |

- Transport means | | | -18.9 | | | | -18.6 | | | | 4.4 | | | | 7.5 | | | | 1.5 | |

- Construction | | | -8.8 | | | | -8.9 | | | | -4.8 | | | | -4.0 | | | | -2.8 | |

- Intangible goods | | | -0.9 | | | | -5.7 | | | | -0.1 | | | | 0.2 | | | | -1.3 | |

Valuable goods | | | -29.3 | | | | -14.7 | | | | 11.0 | | | | -3.5 | | | | 1.1 | |

Exports | | | -17.5 | | | | -17.5 | | | | 11.6 | | | | 12.2 | | | | 5.6 | |

| | | | | |

PRICES | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | |

GDP deflator | | | 2.1 | | | | 2.1 | | | | 0.4 | | | | 0.4 | | | | 1.3 | |

Import deflator | | | -7.7 | | | | -7.7 | | | | 6.7 | | | | 6.9 | | | | 7.3 | |

National final consumption deflator | | | 0.5 | | | | 0.5 | | | | 1.5 | | | | 1.5 | | | | 2.0 | |

Household consumption deflator | | | -0.1 | | | | 0.0 | | | | 1.5 | | | | 1.5 | | | | 2.7 | |

Public consumption deflator | | | 2.1 | | | | 2.0 | | | | 1.4 | | | | 1.4 | | | | -0.1 | |

NPISH consumption deflator | | | 0.9 | | | | 1.2 | | | | 2.6 | | | | 2.1 | | | | 1.5 | |

Gross fixed investment deflator | | | 1.0 | | | | 1.0 | | | | 1.2 | | | | 1.3 | | | | 3.3 | |

- Machinery and equipment | | | 1.3 | | | | 0.7 | | | | -0.4 | | | | 0.4 | | | | 2.2 | |

- Transport means | | | 1.0 | | | | 1.1 | | | | 1.1 | | | | 0.9 | | | | 2.9 | |

- Construction | | | 1.1 | | | | 1.1 | | | | 2.1 | | | | 2.0 | | | | 4.1 | |

- Intangible goods | | | -2.3 | | | | 0.9 | | | | 3.1 | | | | 1.8 | | | | 2.7 | |

Valuable goods deflator | | | 10.5 | | | | 6.5 | | | | 23.4 | | | | 23.7 | | | | 2.9 | |

Export deflator | | | -2.4 | | | | -2.4 | | | | 2.6 | | | | 2.4 | | | | 4.1 | |

| | | | | |

LABOUR | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | |

Employment (FTEs) | | | -2.9 | | | | -2.9 | | | | -0.9 | | | | -0.7 | | | | 0.1 | |

Full-time employment (FTEs) | | | -2.8 | | | | -2.8 | | | | -1.3 | | | | -1.1 | | | | 0.4 | |

Foreign trade

In 2011, Italy’s foreign trade continued on the positive trend that first took shape in 2010, moving substantially in line with the expansion of global trade and international industrial production. Italy confirmed its position as the world’s seventh largest exporter2. The overall trade balance was a deficit of €24.6 billion (1.7 per cent of GDP), improving over the deficit of €30.0 billion in 2010 as a result of exports that grew at a higher rate (11.4 per cent) than imports (9.0 per cent). Both imports and exports hit historical highs in 2011, thus surpassing the records for 2008. Exports amounted to €376 billion, or €7 billion above the 2008 level, and imports came to €400 billion, exceeding the 2008 level by € 18.4 billion. From a geographic perspective, both imports and exports to non-European markets proved more dynamic than flows with European countries.

| 2 | In 2011, the top three exporting countries were China, the United States and Germany (Source: National Institute for Foreign Trade (ICE)). |

| | |

| | MINISTERODELL’ECONOMIAEDELLE FINANZE |

6 | | |

ECONOMICAND FINANCIAL DOCUMENT – ITALY’S STABILITY PROGRAMME

In 2011, Italy enjoyed good growth in total export volumes, particularly due to increased penetration of emerging markets. Exports rose by 4.1 per cent, while imports declined by 1.6 per cent with respect to 2010. More specifically, exports grew mainly toward BRIC (18.9 per cent to Brazil and 13.4 per cent to Russia) and Japan (15.2 per cent). With reference to Europe, increases in exports were registered mainly toward Germany and France (5.3 per cent and 2.9 per cent, respectively). Among non-European markets, import volumes rose markedly from India (10.6 per cent) and the United States (8.9 per cent). In Europe, imports from the UK registered the sharpest rate of increase (3.1 per cent). The only exception to the increase in trade was in the OPEC area, with respect to which both exports and imports contracted (by 6.8 per cent for exports and 21.0 per cent for imports).

A review of average unit values shows that imports performed better than exports in 2011, from both a geographic and sector perspective, with respective rates of growth equal to 10.9 per cent and 7.1 per cent. Such rates reflect increases of 0.4 and of 1.1 percentage points, respectively, over rates posted in the previous year. From a geographic perspective, the greatest increases in average unit values were realized for imports from non-European countries (from 25.3 per cent for OPEC and 24.2 per cent of the Russia to 11.0 per cent for the DAE countries), particularly as a result of energy imports. Instead, for exports, the highest growth in average unit values was seen with respect to the European area (from 10.4 per cent for Spain to 6.8 per cent for Germany).

CHART II.1: EXPORT AND IMPORT VOLUMES BY GEOGRAPHIC AREA - 2011 (% change y/y)

| | |

| MINISTERODELL’ECONOMIAEDELLE FINANZE | | |

| | 7 |

ECONOMICAND FINANCIAL DOCUMENT – ITALY’S STABILITY PROGRAMME

Italy’s share of world exports at current prices in the first half of 2011 remained unchanged with respect to the same period of 2010 (3.0 per cent). A similar performance was reported by the larger European and non-European countries3.

According to provisional data for 2011, inward foreign direct investment in Italy amounted to €25.4 billion, increasing by €18.4 billion over 2010 (€6.9 billion)4. A similar trend was seen all across the European area5.

Prospects for the Italian economy

Italy’s economic prospects continue to be influenced by the evolution of the global scenario and in particular, the European scenario, both of which appear to be improving since the start of 2012. The expansion of advanced economies in 2011 was adversely affected by exceptional factors (such as the natural disaster in Japan in the spring of 2011) and the pronounced financial tensions in the Euro Area, and remains subject to elements of uncertainty. The U.S. recovery that has been under way for about a year could weaken as a result of the deleveraging of households and businesses. Geopolitical tensions in the Middle East could cause increases in oil prices. Though conditions for credit in the Euro Area have improved as a result of the European Central Bank’s interventions, the risks connected to the fragility of the sovereign debt markets should not be overlooked. Possible sources of risk include the stronger-than-expected slowdown of the emerging economies (China, in particular) and/or new concerns regarding financial stability in Japan.

However, there are also upside risks worth mentioning: i) a more robust recovery of the U.S. economy, and ii) more positive fundamental conditions for the Euro Area due to implemented structural reforms.

The weakening of the domestic economic cycle that occurred in 2011 prompted a reduction in the estimate of real GDP growth for 2012; this estimate now stands at -1.2 per cent, and is approximately 0.8 percentage points lower than that forecast in December. The tone of the economy is expected to continue to be weak, although gradually improving, in the first half of 2012, due to the weakness of domestic demand and the effects of transmission of past tensions on the credit market. Such trends are likely to be partially offset by the support coming from net foreign demand. Business activity is expected to recover gradually, starting from the second half of the year. In 2013, GDP should grow moderately (0.5 per cent), slightly above the official estimate at December, accelerating in 2014 (1.0 per cent, unchanged with respect to the previous estimate) and in 2015 (1.2 per cent).

The forecast calls for the continuing expansion of exports over the time horizon of reference, though performance should be less impressive than in 2012. Instead, reflecting the weakness of domestic demand, imports should contract in 2012, and then recover in following years. The current balance of the balance of payments is projected to improve

| 3 | Ministry of the Economic Development, ‘Foreign Trade’, Update, Year 18, no. 4/2011. |

| 4 | Bank of Italy, ‘Balance of Payments and Capital Position Abroad’, Supplements to Statistical Bulletin, Monetary and Financial Indicators, no. 12, New Series, Year XXII, 22 February 2012. |

| 5 | UNCTAD, ‘Global Investment Trends Monitor’, no. 8, 24 January 2012. |

| | |

| | MINISTERODELL’ECONOMIAEDELLE FINANZE |

8 | | |

ECONOMICAND FINANCIAL DOCUMENT – ITALY’S STABILITY PROGRAMME

significantly in 2012-2015, going from -3.1 per cent in 2011 to -1.3 per cent in 2015. Fixed investment is likely to reflect the weakness of demand in 2012, and then expand anew over the three-year period 2013-2015. Household consumption is likely to be impacted in 2012 by the weakening of the labour market, but should then start to grow again gradually in the 2012-2015 period. A restrictive orientation for public spending is projected for 2013-2014.

In the labour market, employment as measured in full-time equivalents (FTEs) is poised to decline by 0.6 per cent in 2012. The unemployment rate would stand at 9.3 per cent. The recovery in terms of employment should materialize in 2013. The unemployment rate is projected to trend downward from 9.2 per cent in 2013 to 8.6 per cent in 2015. Despite another deceleration in the cost of labour, the unit labour cost is expected to grow by 1.7 per cent in 2012 due to setbacks in productivity, though the outlook for the three years thereafter points to moderation of the trend. The GDP deflator should stand at 1.8 per cent in 2012, rising to 1.9 per cent in the three-year period 2013-2015. Inflation as measured by the private consumption deflator is pegged at 2.8 per cent for 2012 (harmonised index of 3.0 per cent), accelerating slightly compared to the previous year, whereas it should remain at a lower level in the 2013-2015 period.

TABLE II.1: BASE ASSUMPTIONS

| | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | |

| | | 2011 | | | 2012 | | | 2013 | | | 2014 | | | 2015 | |

Short-term interest rate1 | | | 1.5 | | | | 1.0 | | | | 3.6 | | | | 4.3 | | | | 4.9 | |

Long-term interest rate | | | 5.3 | | | | 5.4 | | | | 5.6 | | | | 6.0 | | | | 6.2 | |

USD/EUR exchange rate | | | 1.39 | | | | 1.33 | | | | 1.33 | | | | 1.33 | | | | 1.33 | |

Change of the nominal effective exchange rate | | | -0.2 | | | | -5.8 | | | | 0.0 | | | | 0.0 | | | | 0.0 | |

World GDP, excluding EU | | | 4.2 | | | | 4.0 | | | | 4.2 | | | | 4.7 | | | | 4.7 | |

EU GDP growth | | | 1.5 | | | | 0.1 | | | | 1.4 | | | | 1.9 | | | | 2.3 | |

Growth in Italy’s key foreign markets | | | 4.9 | | | | 1.2 | | | | 2.7 | | | | 4.3 | | | | 4.7 | |

World import volumes, excluding EU | | | 7.4 | | | | 6.2 | | | | 6.8 | | | | 7.7 | | | | 7.8 | |

Oil price (Brent, USD/barrel) | | | 111.3 | | | | 119.5 | | | | 119.7 | | | | 119.7 | | | | 119.7 | |

| 1) | Short-term interest rate: the average of the forecast rates on 3-month government securities issued during the year; long-term interest rate: the average of the forecast rates on 10-year government securities issued during the year. |

TABLE II.2a: MACROECONOMIC PROSPECTS

| | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | |

| | | 2011

Level1 | | | 2011 | | | 2012 | | | 2013 | | | 2014 | | | 2015 | |

| | | | % Change | |

Real GDP | | | 1,425,627 | | | | 0.4 | | | | -1.2 | | | | 0.5 | | | | 1.0 | | | | 1.2 | |

Nominal GDP | | | 1,580,220 | | | | 1.7 | | | | 0.5 | | | | 2.4 | | | | 2.8 | | | | 3.2 | |

COMPONENTS OF REAL GDP | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | |

Private consumption | | | 854,589 | | | | 0.2 | | | | -1.7 | | | | 0.2 | | | | 0.5 | | | | 0.7 | |

Public consumption 2 | | | 299,164 | | | | -0.9 | | | | -0.8 | | | | -1.1 | | | | -0.3 | | | | 0.2 | |

Gross fixed investment | | | 269,531 | | | | -1.9 | | | | -3.5 | | | | 1.7 | | | | 2.5 | | | | 2.8 | |

Inventories (% of GDP) | | | | | | | -0.5 | | | | -0.3 | | | | 0.1 | | | | 0.0 | | | | 0.0 | |

Exports of goods and services | | | 404,501 | | | | 5.6 | | | | 1.2 | | | | 2.6 | | | | 4.2 | | | | 4.6 | |

Imports of goods and services | | | 402,330 | | | | 0.4 | | | | -2.3 | | | | 2.2 | | | | 3.6 | | | | 3.9 | |

CONTRIBUTION TO REAL GDP GROWTH 3 | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | |

Domestic demand | | | — | | | | -0.4 | | | | -1.8 | | | | 0.2 | | | | 0.7 | | | | 1.0 | |

Change in inventories | | | — | | | | -0.5 | | | | -0.3 | | | | 0.1 | | | | 0.0 | | | | 0.0 | |

Net exports | | | — | | | | 1.4 | | | | 1.0 | | | | 0.1 | | | | 0.2 | | | | 0.3 | |

| 2) | General Government and NPISH |

| 3) | Slight discrepancies, if any, are due to rounding. |

| | |

| MINISTERODELL’ECONOMIAEDELLE FINANZE | | |

| | 9 |

ECONOMICAND FINANCIAL DOCUMENT – ITALY’S STABILITY PROGRAMME

TABLE II.2b: PRICES

| | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | |

| | | 2011

Level | | | 2011 | | | 2012 | | | 2013

% Change | | | 2014 | | | 2015 | |

GDP deflator | | | 110.8 | | | | 1.3 | | | | 1.8 | | | | 1.9 | | | | 1.9 | | | | 1.9 | |

Private consumption deflator | | | 112.6 | | | | 2.7 | | | | 2.8 | | | | 2.1 | | | | 1.9 | | | | 1.9 | |

HICP | | | 113.8 | | | | 2.9 | | | | 3.0 | | | | 2.2 | | | | 2.0 | | | | 1.8 | |

Public consumption deflator | | | 110.5 | | | | -0.1 | | | | 0.5 | | | | 0.1 | | | | 0.5 | | | | 1.1 | |

Investment deflator | | | 114.5 | | | | 3.3 | | | | 1.9 | | | | 2.2 | | | | 2.3 | | | | 2.2 | |

Export deflator | | | 112.4 | | | | 4.1 | | | | 2.0 | | | | 2.2 | | | | 2.1 | | | | 2.0 | |

Import deflator | | | 118.7 | | | | 7.3 | | | | 3.9 | | | | 1.7 | | | | 1.6 | | | | 1.6 | |

TABLE II.2c: LABOUR MARKET DEVELOPMENTS

| | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | |

| | | 2011

Level1 | | | 2011 | | | 2012 | | | 2013

% Change | | | 2014 | | | 2015 | |

Employment, persons (national accounts) | | | 24,743 | | | | 0.3 | | | | -0.4 | | | | 0.3 | | | | 0.6 | | | | 0.7 | |

Employment, hours worked | | | 43,886,203 | | | | 0.3 | | | | -0.3 | | | | 0.0 | | | | 0.2 | | | | 1.0 | |

Unemployment rate | | | | | | | 8.4 | | | | 9.3 | | | | 9.2 | | | | 8.9 | | | | 8.6 | |

Labour productivity, persons | | | 57,618 | | | | 0.1 | | | | -0.8 | | | | 0.2 | | | | 0.3 | | | | 0.5 | |

Labour productivity, hours worked | | | 32,5 | | | | 0.2 | | | | -1.0 | | | | 0.4 | | | | 0.7 | | | | 0.2 | |

Compensation of employees | | | 668,298 | | | | 1.8 | | | | 0.7 | | | | 1.4 | | | | 2.1 | | | | 2.1 | |

Compensation per employee | | | 38,721 | | | | 1.4 | | | | 1.1 | | | | 1.1 | | | | 1.4 | | | | 1.3 | |

| 1) | Units of measure: employment (persons and hours worked) in thousands of units; labour productivity in euro at constant values; compensation of employees in millions of euro at current values; compensation per employee in euro. |

TABLE II.2d: SECTOR ACCOUNTS

| | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | |

| | | 2009 | | | 2010 | | | 2011 | | | 2012

% GDP | | | 2013 | | | 2014 | | | 2015 | |

Net lending/borrowing with the rest of the world | | | -2.0 | | | | -3.6 | | | | -3.1 | | | | -2.3 | | | | -2.0 | | | | -1.7 | | | | -1.3 | |

- Balance of goods and services | | | -0.5 | | | | -1.9 | | | | -1.5 | | | | -0.9 | | | | -0.6 | | | | -0.3 | | | | 0.0 | |

- Balance of primary income and transfers | | | -1.5 | | | | -1.6 | | | | -1.7 | | | | -1.4 | | | | -1.4 | | | | -1.4 | | | | -1.3 | |

- Capital account | | | 0.0 | | | | 0.0 | | | | 0.1 | | | | 0.0 | | | | 0.0 | | | | 0.0 | | | | 0.0 | |

Net lending/borrowing of private sector | | | 3.5 | | | | 1.0 | | | | 0.8 | | | | -0.6 | | | | -1.5 | | | | -1.5 | | | | -1.2 | |

Net lending/borrowing of the Public administrations1 | | | -5.4 | | | | -4.5 | | | | -3.8 | | | | n.a. | | | | n.a. | | | | n.a. | | | | n.a. | |

Net lending/borrowing of the Public administrations2 | | | -5.4 | | | | -4.6 | | | | -3.9 | | | | -1.7 | | | | -0.5 | | | | -0.1 | | | | 0.0 | |

Statistical discrepancies | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | |

| 1) | ESA95 series. Most recent historical data available: 2011. |

| II.3 | IMPACT OF KEY REFORMS ON GROWTH |

The deregulation and simplification measures enacted by the Government at the start of 20126 and described in the National Reform Programme represent a package of wide-ranging structural reforms aimed at boosting the level of competition within various sectors of the economy and eliminating barriers to enterprises.

The measures in the overall package have been subdivided into three large standard macro areas in order to provide an initial quantitative evaluation of the effects of the

| 6 | Decree-Law No. 1/2012 converted into Law No. 27/2012 and Decree-Law No. 5/2012 converted into Law No. 35/2012. initiatives on growth, employment, consumption and investment. Each of the macro areas describes a specific area of action. |

| | |

| | MINISTERODELL’ECONOMIAEDELLE FINANZE |

10 | | |

ECONOMICAND FINANCIAL DOCUMENT – ITALY’S STABILITY PROGRAMME

For details about the simulations, reference should be made to the chapter in the National Reform Programme on the impact of reforms.

Altogether, the reforms (sum of the effects produced by the individual macro areas) have a total effect on growth equal to 2.4 percentage points of GDP over a nine-year time period7 (2012-2020), with an average annual impact of approximately 0.3 percentage points of GDP. Almost one-half of the contribution to GDP growth is realized in the first four years (0.9 percentage points in 2015).

| | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | |

TABLE II.3: OVERALL MACROECONOMIC EFFECTS OF THE STRUCTURAL REFORMS OF DECREE-LAW NO.

1/2012 AND DECREE-LAW NO. 5/2012 (percentage deviation compared with baseline simulation) | |

| | | 2012 | | | 2013 | | | 2014 | | | 2015 | | | 2020 | |

GDP | | | 0.2 | | | | 0.4 | | | | 0.7 | | | | 0.9 | | | | 2.4 | |

Consumption | | | 0.1 | | | | 0.1 | | | | 0.2 | | | | 0.3 | | | | 1.1 | |

Investments | | | 0.5 | | | | 1.1 | | | | 1.6 | | | | 2.0 | | | | 3.9 | |

Employment | | | 0.2 | | | | 0.2 | | | | 0.2 | | | | 0.1 | | | | 0.1 | |

|

| Source: Analyses with QUEST III—Italy (European Commission). | |

| | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | |

TABLE II.4: MACROECONOMIC EFFECTS OF THE INDIVIDUAL STRUCTURAL REFORM MEASURES CONTAINED IN DECREE-LAW NO. 1/2012 AND DECREE-LAW NO. 5/2012 (percentage deviation compared with baseline simulation) | |

Measure | | Description | | 2012 | | | 2013 | | | 2014 | | | 2015 | | | 2020 | |

Measures aimed at favouring competition and the opening of markets | | Reduction of the mark-up | | GDP Consumption Investments Employment | |

| 0.0

-0.6

0.7

0.0 |

| |

| 0.1

-1.0

1.5

0.0 |

| |

| 0.3

-1.0

2.1

0.0 |

| |

| 0.4

-0.9

2.6

0.1 |

| |

| 1.2

-0.5

4.2

0.3 |

|

| | | | | | | |

Reduction of the limitations on business activity, improvement of the business environment, administrative simplification | | Reduction of the entry barriers | | GDP Consumption Investments Employment | |

| 0.1

0.4

-0.2

0.1 |

| |

| 0.2

0.7

-0.4

0.1 |

| |

| 0.2

0.7

-0.5

0.1 |

| |

| 0.3

0.8

-0.6

0.0 |

| |

| 0.7

1.0

-0.5

-0.1 |

|

| | | | | | | |

| Reduction of administrative charges, administrative simplification | | Reduction of the time spent with the bureaucracy | | GDP Consumption Investments Employment | |

| 0.1

0.3

0.0

0.1 |

| |

| 0.1

0.4

0.0

0.1 |

| |

| 0.2

0.4

0.0

0.1 |

| |

| 0.2

0.5

0.0

0.0 |

| |

| 0.5

0.6

0.2

-0.1 |

|

| |

| Source: Analyses with QUEST III - Italy (European Commission). | | | | | |

| 7 | The simulation assumes that the reforms will be in effect as from the third quarter of 2012. |

| | |

| MINISTERODELL’ECONOMIAEDELLE FINANZE | | |

| | 11 |

ECONOMICAND FINANCIAL DOCUMENT – ITALY’S STABILITY PROGRAMME

| III. | NET BORROWING AND PUBLIC DEBT |

| III.1 | THE PATH TO A TURNAROUND – EXCESSIVE DEFICIT PROCEDURE |

With the launching of the excessive deficit procedure (EDP) against almost all European countries in late 2009, Italy was asked to bring its deficit under the limit of 3.0 per cent of GDP by 2012 and to guarantee an average annual budget correction equal to at least 0.5 percentage points of GDP during the 2010-2012 period.

The public-finance objectives set out in the previous Stability Programme were reinforced in 2011. Measures adopted repeatedly during the year succeeded in balancing the progressive weakening of the macroeconomic framework and the repercussions of financial-market tensions on public accounts.

| | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | |

TABLE III.1: DIFFERENCES WITH RESPECT TO PREVIOUS STABILITY PROGRAMME | |

| | | | | 2011 | | | 2012 | | | 2013 | | | 2014 | |

GDP GROWTH RATE | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | |

| | 2011 Stability Programme | | | 1.1 | | | | 1.3 | | | | 1.5 | | | | 1.6 | |

| | 2012 Stability Programme | | | 0.4 | | | | -1.2 | | | | 0.5 | | | | 1.0 | |

| | Difference | | | -0.6 | | | | -2.4 | | | | -1.1 | | | | -0.7 | |

NET BORROWING (% of GDP) | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | |

| | 2011 Stability Programme | | | -3.9 | | | | -2.7 | | | | -1.5 | | | | -0.2 | |

| | 2012 Stability Programme | | | -3.9 | | | | -1.7 | | | | -0.5 | | | | -0.1 | |

| | Difference | | | -0.1 | | | | 1.0 | | | | 1.0 | | | | 0.1 | |

PUBLIC DEBT (% of GDP) | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | |

| | 2011 Stability Programme | | | 120.0 | | | | 119.4 | | | | 116.9 | | | | 112.8 | |

| | 2012 Stability Programme | | | 120.1 | | | | 123.4 | | | | 121.5 | | | | 118.2 | |

| | Difference | | | 0.1 | | | | 4.0 | | | | 4.6 | | | | 5.4 | |

In April 2011, with the presentation of the 2011 Economic and Financial Document (DEF), the overall financial objectives were confirmed through 2012, whereas the achievement of a balanced budget was planned for 2014 on the basis of a budget correction package for 2013-2014 equivalent to approximately 2.3 percentage points of GDP.

In view of the European Commission’s assessments of the macroeconomic situation and budget set out in the 2011 Stability Programme, the ECOFIN Council made a recommendation to Italy in July 2011, requesting the country to: implement the fiscal consolidation plan to ensure the correction of the excessive deficit; use any unforeseen revenue on the budget-policy front to accelerate the reduction of the deficit and debt, with a view toward achieving the balanced budget target for the years of 2013 and 2014; reinforce the financial framework with the introduction of caps on expenditure; and improve monitoring of expenditures linked to different sectors of the public administration.

As had occurred in previous years, the correction of the public accounts was moved forward, with the adoption of a sizeable budget-rebalancing package in the summer months for the years 2011-2014. This package guaranteed a roughly €60 billion

| | |

| | MINISTERODELL’ECONOMIAEDELLE FINANZE |

12 | | |

ECONOMICAND FINANCIAL DOCUMENT – ITALY’S STABILITY PROGRAMME

cumulative net correction in net borrowing by the end of 2014, equivalent to 3.4 per cent of GDP. Later, in September, with the DEF Update, forecasts of public accounts were updated, taking into consideration of: the weakening of the macroeconomic scenario set out for 2012-2014 (equal to a total of almost two percentage points for the entire three-year period); indications emerging about the trend of the macroeconomic aggregates; the effects of the three-year budget package approved during the summer through two decree-laws1; and the emergence of new financial-market tensions. In order to confirm the 2011 target of 3.9 per cent and reinforce the targets for the years thereafter by moving the balanced-budget up to 2013, it was necessary to adopt stronger corrective measures, of an amount exceeding that originally planned.

Taking into consideration repercussions on the year-on-year trend of public accounts stemming from a new downward revision of growth prospects for 2012-2014 (about 1.9 percentage points total for the three-year period) and the dramatic deterioration of the sovereign debt crisis in Europe, another package of corrective measures was adopted in December to assure that Italy would meet its commitment to balance its budget in 20132.

Another downward revision of growth projections for 2012 was made in December, with estimates regarding public accounts worsening as a consequence. This was, however, mostly (not totally) offset by an expected reduction in interest expenditure. The Government’s commitment to a balanced budget in 2013 was based on the scenario set out in December. As a consequence this target will be reached, and indeed far surpassed, in structural terms.

Given the more recent economic trend and the measures already adopted and transformed into law, the Government can substantially confirm the path to a turnaround as outlined back in December: net borrowing moves back to a point well below the reference value of 3.0 per cent in 2012 and continues to decrease in subsequent years, making it possible to achieve a structural budget surplus in 2013 and in the years thereafter. The primary surplus increases in nominal terms, reaching 5.7 per cent in 2015, and thus significantly grows with respect to the 1.0 per cent realized in 2011.

The following table shows the adjustment in public accounts for 2011-2014. Altogether, the three budget packages finalized in 2011 will allow for a cumulative correction in terms of net borrowing equivalent to 3.0 percentage points of GDP in 2012, 4.6 in 2013 and 4.8 in 20143.

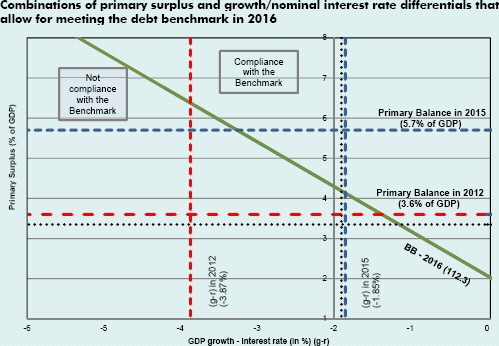

The contribution of incremental revenues to the net budget represents the prevalent quota in the 2012-2014 period; savings on expenditure are nonetheless growing during the entire three-year period; the pension measures yield their full effects over an even longer time period (for a detailed analysis, see the box in Chapter V). Incremental net revenues are equal to 2.4 percentage points of GDP in 2012 and 3.0 in 2013 and 2014, while the net reduction in expenditure is respectively equal to 0.6 percentage points in 2012, 1.6 in 2013 and 1.9 in 2014.