Exhibit (3)

| | | |

| | | Italy's Stability Programme |

| | | |

| | | 2022 |

MINISTERO DELL'ECONOMIA E DELLE FINANZE | | Abridged version |

| | | Italy's Stability Programme |

| | | |

| | | 2022 |

| | | |

| | | |

| | | Abridged version |

| | | |

| | | |

| | | |

| | | |

| | | |

| | | |

| | | Submitted by Prime Minister |

| | | |

| | | Mario Draghi |

| | | |

| | | |

| | | and Minister of the Economy and Finance |

| | | |

| | | Daniele Franco |

| | | |

| | | |

| | | |

| | | |

| | | |

MINISTERO DELL'ECONOMIA E DELLE FINANZE | | Adopted by the Council of Ministers on 6 April 2022 and endorsed by the Parliament on 20 April 2022 |

FOREWORD

In 2021, the Italian economy posted a strong recovery, as GDP grew by 6.6 percent in real terms and the general government deficit and debt ratios to GDP fell more sharply than expected, to 7.2 percent and 150.8 percent, respectively, from 9.6 percent and 155.3 percent in 2020.

Italy’s Q4-to-Q4 GDP growth in 2021 was the highest among the large European economies, thanks also to the policies adopted by the Italian Government to support households and businesses and to the success of the anti-Covid vaccination campaign.

In the final months of the year, the economic environment deteriorated, not only because of the surge in Covid-19 infections caused by the spread of the Omicron variant, but also because of the exceptional increase in the price of natural gas, which drove up electricity tariffs and emission rights (ETS) prices. The consequent increase in the inflation rate, which has been shared by all advanced economies, albeit to a varying degree, has led the main central banks to reverse their monetary policy stance towards restriction or, in the case of the European Central Bank, to signal a future move in that direction. As a result, interest rates rose, and the spread between the yield on Italian government bonds and that on German Bunds widened. Even so, the growth outlook at the start of the year, although revised slightly downwards, remained largely favourable.

In February, following a military escalation, Russia launched its invasion of Ukraine, to which the European Union, the G7 and numerous other countries responded with a series of economic sanctions. The war led to a further increase in the prices of energy, foodstuff, metals, and other raw materials and to a further decline in business and household confidence. In Italy, consumer inflation rose to 6.7 percent in March, and core inflation (net of energy products and fresh food), albeit much more moderate, reached 2 percent.

In view of these developments, the growth outlook for the economy is now weaker and much more uncertain than at the beginning of the year. In updating the official forecast of this Document, the worsening of the economic scenario is determined by the trend of exogenous variables - from energy prices to interest rates, from the trade-weighted exchange rate of the euro to the lower expected growth of Italy’s export markets. These variables are now all less favourable than they were in September, when the previous official forecast was published in the Update of the Stability Programme and in the Draft Budgetary Plan (DBP) for 2022.

Given a fourth-quarter GDP level closer to the pre-crisis high than previously estimated and to the economic impact of the war in Ukraine, the baseline GDP growth forecast (under existing legislation) for this year is revised down compared to the DBP, from 4.7 percent to 2.9 percent. The one for 2023 is also cut from 2.8 percent to 2.3 percent, while for 2024 the forecast is revised only slightly, i.e.,

| MINISTRY OF ECONOMY AND FINANCE | III |

| | ECONOMIC AND FINANCIAL DOCUMENT 2022 |

from 1.9 percent to 1.8 percent. The forecast for 2025 is set at 1.5 percent, following the approach according to which the three-year projection converges towards the “potential” growth rate of the Italian economy, which is currently estimated at 1.4 percent. This estimate assumes the implementation of the investment and reform programme envisaged in the National Recovery and Resilience Plan (NRRP).

In light of the many unknowns of the current situation, the baseline forecast is characterised by significant downside risks, including the possible interruption of natural gas inflows from Russia, which accounted for 40 percent of Italy’s imports in 2021. Although this risk is already partly incorporated in current gas and oil prices, it is reasonable to assume that a complete shutdown of Russian gas would cause further price increases, which would negatively affect GDP and push up inflation further. In such a scenario, average annual growth in 2022 could fall below the 2.3 percent inherited from 2021.

Already last year, the Italian Government responded to the sudden increase in energy prices with measures to contain costs for gas and electricity users. Such measures - which have been implemented since the third quarter of 2021 - amounted to 5.3 billion in terms of general government net borrowing in 2021 and 14.7 billion for the first half of this year, when measures were added also in favour of large companies, including energy-intensive ones, to contain fuel costs and to support the transportation sector. As a result of these measures, the increase in energy bills paid by businesses and households in the first half of the year is estimated to be at least a quarter lower than it would have been without such interventions.

Additional measures were adopted in the early months of the year in favour of specific categories (non-repayable grants and support for business liquidity), measures to cover part of the costs of regions and local authorities, and measures for the health sector (for a total of another 4.1 billion in 2022).

The Italian Government is also working on a broader and more structural response to the energy crisis, both through actions at the national level and through active participation in the formulation of European policies. On the national front, in agreement with the companies in the sector, an effort is being made to broaden and diversify gas supplies by making greater use of Italy’s southern pipelines, as well as to increase LPG imports and regasification capacity. An increase in domestic production of natural gas and biomethane will also be promoted.

The commitment of the Italian Government and gas companies to diversify gas supply sources is accompanied by growing efforts to rapidly reduce dependence on fossil energy sources by boosting the installation of electricity generation capacity from renewable sources. This line is consistent with the European Commission’s recent REPowerEU communication, which emphasises the development of biofuel production and a concerted EU-wide policy for gas acquisition and the imposition of minimum storage levels, while also calling on Member States to curb energy consumption by increasing the energy efficiency of buildings and saving measures, for example on indoor temperatures.

The Commission also proposes, in line with the position expressed by Italy, to revise and improve the mechanisms for the functioning of gas and electricity

| IV | MINISTRY OF ECONOMY AND FINANCE |

markets, without undermining the principles of transparency and competitiveness on which they are based.

The main objective in responding to the current energy crisis is to accelerate theecological transition while securing gas supplies, which represent the bridge to a decarbonised and sustainable economy, as well as improving the structure and the transparency of the energy markets.

More generally, the difficult phase we are going through should not be a distraction, but rather reinforce the commitment of all administrations and levels of government to effectively implement the NRRP and its largest ‘mission’ in terms of investments and other outlays, namely ecological transition. The completion of the first instalment of the NRRP at the end of 2021, with the disbursement of the relevant funds by the Commission, was indeed a first important achievement.

The past year was also characterised by bottlenecks in international transport and logistics, as well as shortages of crucial products in modern industrial supply chains such as semiconductors. The automotive industry has been particularly affected, not only because of insufficient availability of electronic components and consumers’ uncertainty about the timing of the phasing out of conventional cars, but also because of difficulties in reconverting the conventional car industry.

With regard to industrial policy, new funds have been allocated to support the car industry (both in terms of sales of non-polluting vehicles and support for innovation and reconversion of the production chain) and to sustain investments in the semiconductor industry.

Further measures will be issued in April. However, before describing what the next steps will be, it is worth considering the starting point in terms of public finance.

As mentioned, the year 2021 saw a significantly lower than expected general government deficit. Data on the cash requirements of the State sector shows that public finance developments remained favourable in the first quarter of this year. The new projections show lower general government deficits than projected for 2022-2024 in the DBP policy scenario, especially for 2022. This reflects sustained and higher-than-expected tax and social security contribution revenues and lower expenditure. Recent measures to lower energy costs have been funded in a way that does not raise the deficit compared to the announced target.

The general government deficit in the baseline scenario is 5.1 percent of GDP this year and is projected to fall to 2.7 percent of GDP in 2025. Against these projections, the Government has decided to confirm the DBP nominal deficit targets for 2022-2024. This entails a deficit path starting from 5.6 percent of GDP this year and declining to 2.8 percent in 2025 and creates room for new expansionary measures amounting to 0.5 percentage points of GDP this year, 0.2 in 2023 and 0.1 in 2024 and 2025.

Using these budgetary margins, the Italian Government will prepare a new decree-law to restore some funds that were used to cover the recent Decree-Law No. 17, integrate the resources intended to compensate for the increase in the cost of public works in the face of the dynamics of the price of energy and raw materials, and intervene again to contain the cost of fuel and energy. Instruments will also be put in place to support the companies most affected by the sanctions against Russia;

| MINISTRY OF ECONOMY AND FINANCE | V |

| | ECONOMIC AND FINANCIAL DOCUMENT 2022 |

to this end, the Guarantee Fund for SMEs will also be refinanced. Finally, additional resources will be made available to provide assistance to Ukrainian refugees.

Taking into account these measures, the policy scenario is characterised by GDP growth that is slightly higher than the baseline, especially in 2022 and 2023, when GDP is expected to grow by 3.1 percent and 2.4 percent, respectively, with positive repercussions on employment growth.

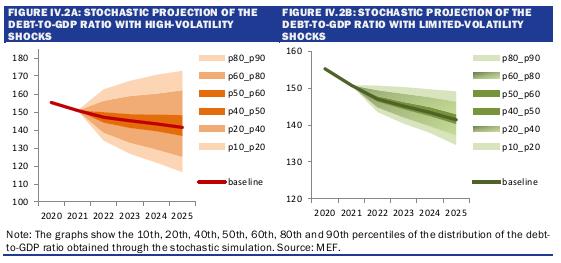

As mentioned above, in the policy scenario the general government deficit target is unchanged from the DBP for the years 2022-2024 and declines below 3 percent in 2025. The path of the structural balance is only slightly higher than that of the DBP due to a different quantification of one-off measures, but still envisages improvements in the structural balance throughout the planning horizon. The debt-to-GDP ratio will fall from 150.8 percent in 2021 to 141.4 percent in 2025.

The decision to confirm deficit targets that were set under more favourable economic circumstances testifies to the attention of the Government towards the sustainability of public finance. Even at this difficult time, when public finance is called upon to respond to multiple needs of both a cyclical and structural nature, the sustainability of public accounts is confirmed. Indeed, longer-term projections show that the gradual improvement of the budget balance in the years after 2025 and the full implementation of the reform programme outlined in the NRRP will make it possible to bring the debt-to-GDP ratio below the pre-pandemic crisis level (134.1 percent) by the end of the decade.

At the same time, it remains imperative for the Government to continue working to promote higher and sustainable economic growth. Already last year, it repeatedly laid the foundations for raising the economy’s growth potential. More than 320 billion has been allocated for public investment, adding to the resources provided for in the NRRP those of the Supplementary Fund and those earmarked by the 2022 Budget Law. Incentives for private investment and, in particular, incentives for research have been extended over time to provide greater planning certainty. New instruments have also been created to support basic and applied research.

The reform of the Personal Income Tax (IRPEF) and the cut in the Regional Tax on Production Activities (IRAP) reduce the tax burden on households and businesses, which will have positive effects on employment and the labour market. In addition, the introduction of the universal child benefit, the development of early education infrastructure, and the support for home buying in favour of young people are examples of the broader action that the Italian Government is taking in favour of families and the birth rate, also in light of adverse demographic trends.

The current situation should not make us turn our attention away from the structural policies that have already been launched in the strategic sectors of the ecological and digital transition, the competitiveness of the economic system, health and welfare, with particular regard to the structure of the pension system; for this latter, it will be necessary to find solutions that allow for flexible exits and a strengthening of supplementary pensions, while fully respecting the sustainability of public debt and of the pay-as-you-go system. Retirement prospects for younger generations will also have to be carefully analysed.

| VI | MINISTRY OF ECONOMY AND FINANCE |

In conclusion, the policy objectives of the Document are based on a scenario in which the economy is slowing down but is still registering a significant annual growth. The budgetary margins resulting from the confirmation of the targets set in the DBP will be used to further support the productive system, households and to carry out planned investments.

However, there is considerable uncertainty related to international political and economic factors. If the global scenario deteriorates further, annual growth is likely to be lower than that resulting from the carry-over of the 2021 result.

The Italian Government will not hesitate to intervene as decisively and rapidly as possible to support Italian households and businesses.

The Italian Government is committed to strongly accelerating the diversification of energy sources and the achievement of greater national energy autonomy.

The pressing problems we are currently facing must not divert our attention from medium and long-term objectives. The NRRP and all the initiatives aimed at making our economy more sustainable must be fully implemented: we must boost investment in human and physical capital and raise the employment rate and productivity growth.

Daniele Franco

Minister of Economy and Finance

| MINISTRY OF ECONOMY AND FINANCE | VII |

| | ECONOMIC AND FINANCIAL DOCUMENT 2022 |

| VIII | MINISTRY OF ECONOMY AND FINANCE |

INDEX

| I. | RECENT TRENDS IN THE ECONOMY AND THE PUBLIC FINANCES |

| | |

| II. | BASELINE MACROECONOMIC AND BUDGET FORECAST |

| II.1 | Baseline macroeconomic forecast |

| II.2 | Risks to the baseline macroeconomic forecast |

| II.3 | Budgetary outlook under existing legislation |

| | |

| III. | UPDATED POLICY SCENARIO |

| III.1 | Fiscal policy scenario |

| III.2 | Macroeconomic forecast under the policy scenario |

| III.3 | Budget balance, convergence towards the Medium-Term Objective and the expenditure rule |

| III.4 | Debt-to-GDP ratio and the debt rule |

| | |

| IV. | SUSTAINABILITY OF PUBLIC FINANCES |

| | |

| IV.1 | Risk scenarios of public finances |

| IV.2 | Sustainability analysis of public debt |

| | |

| V. | ANNEX |

| MINISTRY OF ECONOMY AND FINANCE | IX |

| | ITALY’S STABILITY PROGRAMME 2022 |

TABLES

| Table II.1 | Summary macroeconomic baseline scenario |

| Table III.1 | Public finance indicators |

| Table III.2 | Synthetic macroeconomic policy scenario |

| Table III.3 | Significant deviations |

| Table III.4 | Trends in current expenditure in relation to the expenditure benchmark |

| Table III.5 | Debt rule compliance |

| Table IV.1 | Sensitivity to growth |

FIGURES

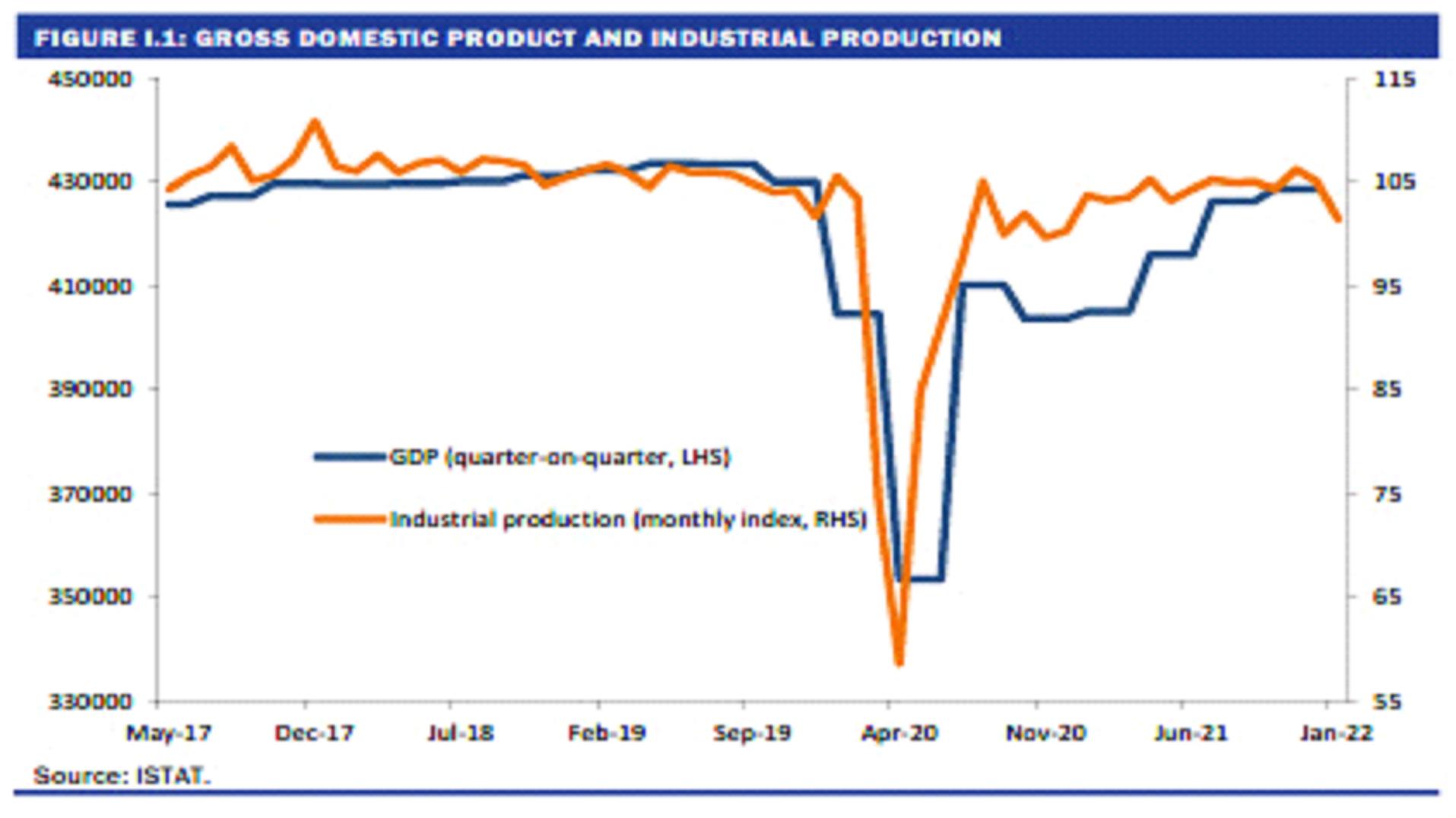

| Figure I.1 | Gross domestic product and industrial production |

| Figure I.2 | Wholesale prices for natural gas and electricity |

| Figure I.3 | Consumer prices for the whole nation (NIC) |

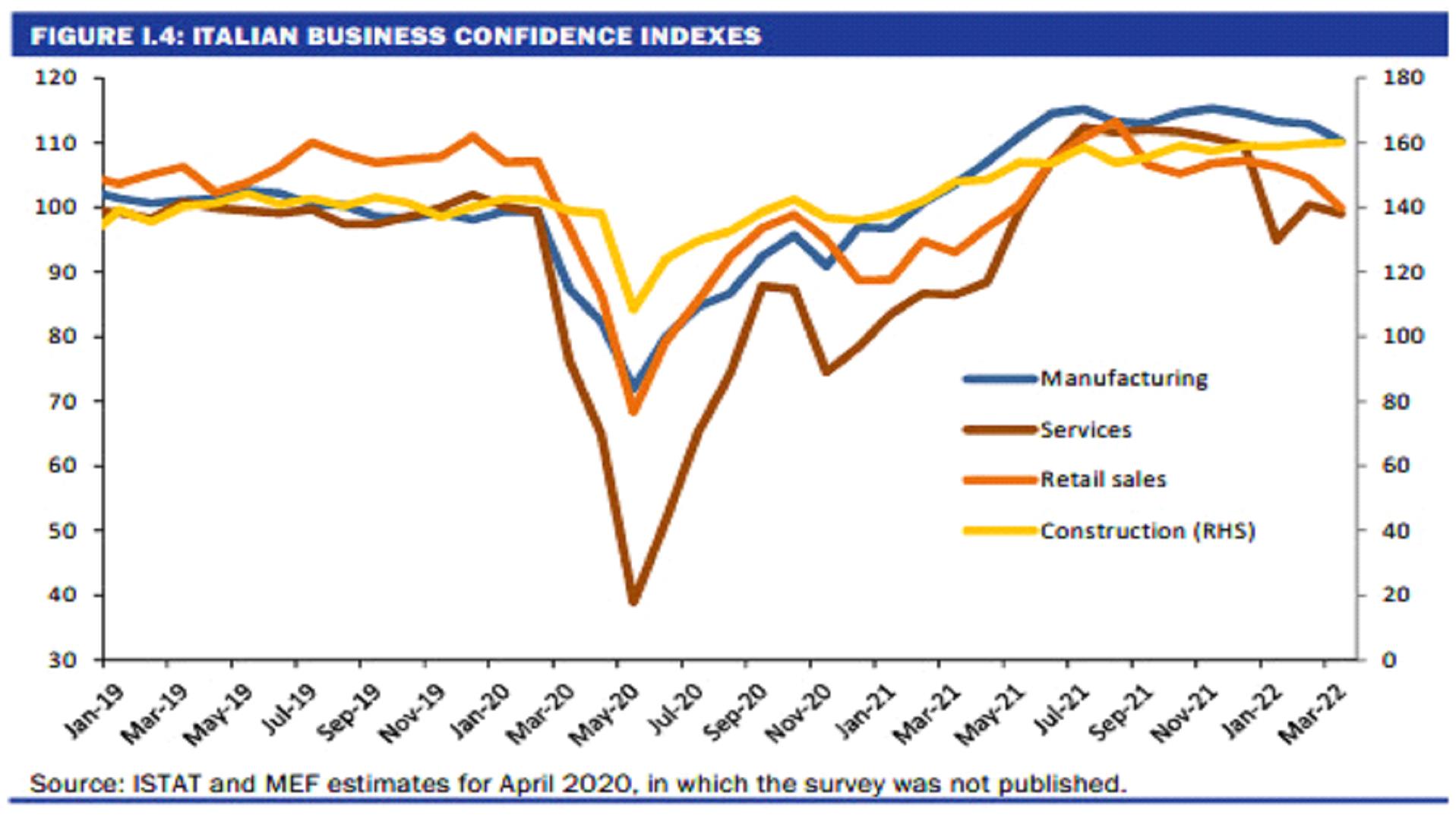

| Figure I.4 | Italian business confidence indexes |

| Figure I.5 | Net borrowing and gross debt of the general government as a ratio to GDP |

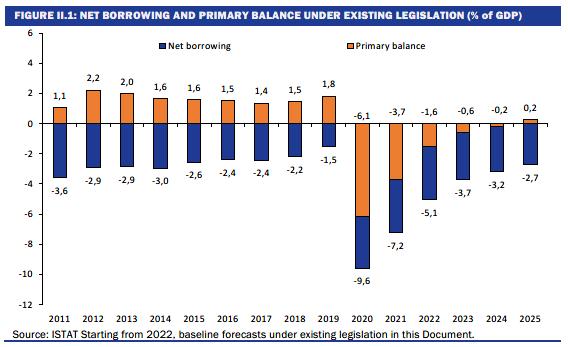

| Figure II.1 | Net borrowing and primary balance under existing legislation |

| Figure III.1 | Evolution of the Debt-to-GDP ratio gross and net of European AID |

| Figure IV.1 | Dynamics of the Debt-to-GDP ratio in sensitivity scenarios |

| Figure IV.2A | Stochastic projection of the Debt-to-GDP ratio with Hight- Volatility Shocks |

| Figure IV.2B | Stochastic projection of the Debt-to-GDP ratio with Limited-Volatility Shocks |

| Figure IV.3 | Medium-Term projection of the Debt-to-GDP ratio |

| Figure IV.4 | Debt-to-GDP ratio in the reference scenario |

| Figure IV.5 | Impact of greater reform-related growth |

| Figure IV.6 | Impact of improvement in tax compliance |

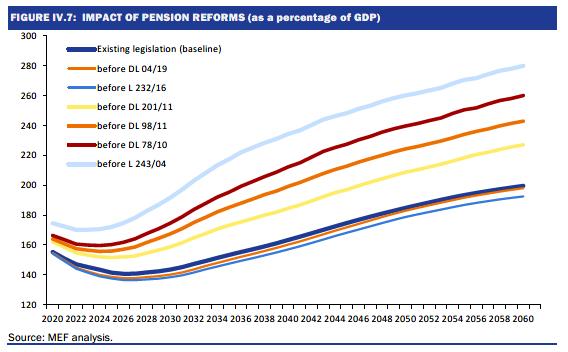

| Figure IV.7 | Impact of pension reforms |

BOX

| Chapter II | The recent evolution of trade relations between Italy and Russia |

| | Forecast errors for 2021 and revised estimates for 2022 and following years |

| | A risk analysis of the geopolitical situation and exogenous variables |

| X | MINISTRY OF ECONOMY AND FINANCE |

| I. | RECENT TRENDS IN THE ECONOMY AND THE PUBLIC FINANCES |

In 2021, Italy achieved strong recovery in gross domestic product and significant improvements in public finances. Gross domestic product (GDP) grew by 6.6 percent in real terms, after the exceptional fall of 9.0 percent recorded in 2020 in connection with the outbreak of the pandemic. General government net borrowing fell to 7.2 percent of GDP, from 9.6 percent in 2020. Thanks to sustained output growth in nominal terms (7.2 percent), the public debt-to-GDP ratio at the end of 2021 fell to 150.8 percent, from its peak of 155.3 percent in 20201.

However, after the remarkable recovery in the two middle quarters of 2021, the pace of GDP growth slowed in the final months of last year due to the fourth wave of the Covid-19 outbreak, shortages of materials and components, and soaring natural gas and electricity prices, which had already risen sharply since late spring.

In the first two months of this year, indicators of the international cycle weakened, although they remained moderately positive. In Italy, the impact of the rise in energy prices on the costs of businesses and household budgets worsened, although the measures financed by the 2022 Budget Law and subsequent

________________________

1 These estimates differ from the official data published by ISTAT on 1 March 2022 following the subsequent ISTAT press release of 24 March 2022, in which ISTAT revised the nominal GDP for 2021 downwards due to a value adjustment for natural gas imports and the related import prices.

| MINISTRY OF ECONOMY AND FINANCE | 1 |

| | ITALY’S STABILITY PROGRAMME 2022 |

Government measures2 reduced it by more than a quarter for the first half of 2022. In January, production in industry and construction came to a sharp halt, while the inflation rate rose again, in Italy as well as in other European countries.

The strong inflationary impulse from energy and raw materials also caused an upward revision of market expectations on the future monetary policy of the European Central Bank (ECB). As a result, interest rates rose significantly, and the yield differential between Italian government bonds and the Bund widened.

This already complex economic situation was compounded by Russia’s military attack on Ukraine at the end of February. The aggression led to the immediate imposition of economic sanctions against Russia by the European Union (EU), the G7 and many other countries. EU sanctions were initially targeted at banks and individuals; later, they were expanded to include the export of luxury and high-tech goods and steel imports. Although gas and oil are excluded from sanctions for the time being, natural gas and oil prices rose further, reaching a new high on 8 March, which was followed by a correction, aided by the announcement of a package of EU measures, including the REPowerEU Communication, and continued normal inflows of Russian gas.

The military crisis in Ukraine has also caused a marked increase in food commodity prices, which may have further impacts on inflation in a context in which Italy’s March consumer prices, according to preliminary data from ISTAT, were up 6.7 percent year-on-year according to the consumer price index for the whole nation (NIC), from 5.7 percent in February, with the underlying component also rising to 2.0 percent, from 1.7 percent3.

________________________

2 Decree-Laws Nos. 4 of 27 January 2022, 17 of 1 March 2022 and 21 of 21 March 2022.

3 The underlying component of the NIC index excludes energy, fuel, and fresh food.

| 2 | MINISTRY OF ECONOMY AND FINANCE |

I. RECENT TRENDS IN THE ECONOMY AND THE PUBLIC FINANCES | |

In the same months, Covid-19 infections peaked on a weekly basis around 20 January and then fell rapidly until the beginning of March, when new increases were recorded, also in correspondence with an increased spread of the BA.2 sub-lineage of the Omicron variant. As at the end of March, the infection trend appears to be stabilising, and the trend in hospitalisations and intensive care occupancy rates is such that all Italian regions are now classified as low risk. Approximately 90 percent of the population aged over 12 and almost 33 percent of children aged between 5 and 11 have completed the basic vaccination cycle. Taking this overall picture into account, the Italian Government decided to end the state of emergency on 31 March and adopted a roadmap for the removal of the current anti‑Covid restrictions4.

Nevertheless, the pandemic is still ongoing and remains an obstacle to economic activity at a global level, both in terms of impact on labour supply and consumer behaviour, and adverse effects on global value chains and transport costs.

Against this backdrop of great uncertainty, Italian household confidence, which had already been on a slight downward trend since October, fell sharply in March due to the war in Ukraine. In particular, households were much more pessimistic about Italy’s economic prospects and less inclined to make purchases of durable goods, while their assessment of their own economic conditions did not worsen appreciably.

According to the ISTAT business survey, the deterioration in business confidence was more limited, with a moderate decline in manufacturing and services and a more marked deterioration in retail trade. In construction, on the other hand, the confidence index reached a new high, although a high proportion of companies reported upward pressure on prices.

________________________

4 The provisions are contained in Decree-Law No. 24/2022 of 17 March 2022.

| MINISTRY OF ECONOMY AND FINANCE | 3 |

| | ITALY’S STABILITY PROGRAMME 2022 |

Based on the latest available data, although industrial production is estimated to have rebounded in February, nowcasting models indicate that the 0.6 percent cyclical increase recorded in the fourth quarter of 2021 was followed by a 0.5 percent contraction in GDP in the first quarter of this year, which is mainly attributable to a contraction in industrial value added. Quarterly GDP growth is expected to recover moderately in the second quarter, mainly thanks to services. However, it should be noted that in the March ISTAT survey, manufacturing firms’ expectations on orders and production worsened markedly, pointing to downside risks for the second quarter.

Turning to public finance, the decline in the general government net borrowing to 7.2 percent in 2021 is a much better result than the estimate presented in last year’s Stability Programme (11.8 percent) and the one presented in the Update of the Stability Programme and the Draft Budgetary Plan (DBP) (9.4 percent). This reduction occurred despite the extraordinary amount of support measures for households, businesses, labour, health, education, universities, and research implemented during the year in response to the pandemic (totalling 71 billion) and measures to contain energy costs for households and businesses (5.3 billion).

The lower deficit in 2021 compared to the forecast is the result of a better performance of both expenditure and revenues of the general government sector. In fact, almost all components of current primary expenditure were lower than expected, especially wages, intermediate consumption, and social benefits other than pensions. Public investment was in line with forecasts (reaching almost 51 billion, or 2.9 percent of GDP), while interest payments slightly exceeded the September estimates, mainly due to the increase in Italian and European inflation, which drove up payments on inflation-indexed securities. On the revenue side, both tax revenues and social security contributions exceeded DBP estimates by a total of 26.4 billion (1.5 percent of GDP).

| 4 | MINISTRY OF ECONOMY AND FINANCE |

I. RECENT TRENDS IN THE ECONOMY AND THE PUBLIC FINANCES | |

The most recent data indicates that the positive trend of public finance continued in the first quarter of 2022, as the cash requirements of the State sector fell to 30.0 billion from 41.1 billion in the same period last year. The decline in cash requirements appears to be mainly due to the growth in tax and social security contributions revenues, which in January increased by 13.8 percent and 7.8 percent respectively compared to the same month last year.

| MINISTRY OF ECONOMY AND FINANCE | 5 |

| | ITALY’S STABILITY PROGRAMME 2022 |

| 6 | MINISTRY OF ECONOMY AND FINANCE |

II.

| BASELINE MACROECONOMIC AND BUDGET FORECAST |

II.1 BASELINE MACROECONOMIC FORECAST

Starting from an ISTAT estimate of real GDP growth in 2021 that is higher than that projected in the Update of the Stability Programme and in the Draft Budgetary Plan (DBP), 6.6 percent compared to 6.0 percent, the baseline forecast (under existing legislation) for 2022 has fallen to 2.9 percent from 4.7 percent in the DBP, although the quarterly GDP profile of 2021 has created a carry-over effect of 2.3 percent this year.

In addition to the fact that the level of quarterly real GDP inherited from 2021 is significantly higher, the downward revision of the forecast for 2022 is mainly due to the worsening of the exogenous variables of the forecast. In fact, the growth forecasts for world trade and imports of the most important countries as export markets for Italy have been revised downwards. Moreover, the expected levels of commodity and energy prices are markedly higher, and so are current and expected interest rates. The weighted exchange rate of the euro is also less competitive, although the euro remains weak against the dollar. Overall, estimates using the Treasury’s ITEM model suggest that the changes in exogenous factors since last September would cut the real growth forecast for 2022 by at least 1.4 percentage points.

The lower import growth of Italy’s trading partners, which already incorporates to some extent the onset of the Ukraine crisis, must be added to the specific impact of lower bilateral trade flows between Italy and Russia due to the war situation and the sanctions. Russia’s share of Italian exports was significantly reduced from 2013 onwards due to the sanctions that were adopted in 2014 after the annexation of Crimea and Russia’s occupation of part of Donbass. In 2021, this share amounted to 1.5 percent. The main goods exported to Russia are mechanics, furniture, clothing, footwear, foodstuffs, and transport equipment.

Exports to Russia exceed 3.0 percent of sectoral exports only for clothing and furniture, and 2.0 percent for machinery and equipment. Based on a very broad interpretation of the measures, it is estimated that the sectors subject to export bans account for about half of Italian exports to Russia. The elimination of such exports since March would cause a drop in Italian GDP of about 0.2 percentage points in 2022 and a further impact of 0.1 points in 2023.

Russia’s weight in Italy’s foreign trade is greater on the import side: in 2021, partly due to the rise in prices, it amounted to 3.0 percent and mainly included natural gas, oil, metals, and steel products. There have been no reductions in gas and oil supplies so far, while, as mentioned, imports of steel products from Russia have been banned and those from Ukraine are severely limited by the ongoing

| MINISTRY OF ECONOMY AND FINANCE | 7 |

| | ITALY’S STABILITY PROGRAMME 2022 |

conflict and the destruction of important production sites. This will cause difficulties in obtaining certain semi-finished products and an increase in their price, which will have a negative impact on GDP by an estimated amount of less than a tenth of a percentage point.

As mentioned above, the conflict in Ukraine has also had a negative impact on household and business confidence, on top of causing a sharp correction in financial markets, which has been partially reversed. The effect of these factors on GDP has been quantified at an additional 0.2 percentage points of reduced growth in 2022.

On the other hand, the update of the growth forecast for 2022 also takes into account the different time distribution of expenditure related to the National Recovery and Resilience Plan (NRRP) with respect to what was assumed in the DBP, as well as the most recent measures adopted by the Italian Government to contain the increase in gas and electricity costs in the second quarter and to support energy-intensive companies and some leading manufacturing sectors, such as automotive, components and semiconductors5. It is estimated that the different time distribution of expenditure related to the NRRP will have a positive impact on growth in 2022 of about 0.2 percentage points, while the other measures, being offset by a temporary reduction in the financing of some expenditure and increases in revenues, will have a limited impact on GDP growth in this year (in the case of the Decree-Law No. 17, they will have a delayed effect of some significance in 2023).

The new macroeconomic forecast is also characterised by a much higher inflation rate than expected in the DBP. The household consumption deflator, which grew by 1.7 percent in 2021, is projected to increase by 5.8 percent in 2022, against a forecast of 1.6 percent in the DBP. The GDP deflator growth forecast, also 1.6 percent in the DBP, has risen to 3.0 percent. This brings the new nominal GDP growth forecast to 6.0 percent, only slightly lower than the 6.4 percent forecast in the DBP.

In the face of soaring inflation, wages and labour income are expected to accelerate more moderately, although the renewal of public (and some other) contracts will cause contractual wages to accelerate. Thanks to employment growth too, which is slower than in 2021 but still significant (2.6 percent in terms of hours worked), compensation of employees would grow by 5.5 percent in nominal terms this year, up from 7.7 percent last year. The unemployment rate would fall from 9.5 percent in 2021 to 8.7 percent.

On the external side, as it was already the case in the second half of 2021, the sharp increase in import prices will lead to a narrowing of the trade and current account surplus. The latter would fall to 2.3 percent of GDP this year, from 3.7 percent of GDP in 2020 and 3.3 percent in 2021.

Regarding the coming years, the GDP growth forecast for 2023 is also lower than that of the DBP (down to 2.3 percent from 2.8 percent) due to the worsening of the exogenous variables of the forecast - in particular, higher expected levels of energy prices and interest rates and lower expected growth in world trade. The forecast for 2024 is almost unchanged (1.8 percent against 1.9 percent), while the forecast for 2025, which was not considered in the DBP horizon, is set at 1.5 percent, also on the basis of the usual approach of making the three-year forecast

________________________

5 This refers to Decree-Laws No. 17 of 1 March 2022 and No. 21 of 21 March 2022.

| 8 | MINISTRY OF ECONOMY AND FINANCE |

II. BASELINE MACROECONOMIC AND BUDGET FORECAST | |

converge towards the potential growth rate of the Italian economy. The latter, assuming the implementation of the investment and reform programme envisaged by the NRRP, is set at 1.4 percent.

| TABLE II.1: SUMMARY MACROECONOMIC BASELINE SCENARIO (1) (percentage changes, unless otherwise indicated) |

| | 2021 | 2022 | 2023 | 2024 | 2025 |

| GDP | 6.6 | 2.9 | 2.3 | 1.8 | 1.5 |

| GDP deflator | 0.5 | 3.0 | 2.1 | 1.8 | 1.8 |

| Consumption deflator | 1.7 | 5.8 | 2.0 | 1.7 | 1.8 |

| Nominal GDP | 7.2 | 6.0 | 4.4 | 3.6 | 3.3 |

| Employment (AWU) (2) | 7.6 | 2.5 | 2.2 | 1.6 | 1.3 |

| Employment (WF) (3) | 0.8 | 1.8 | 1.7 | 1.2 | 1.0 |

| Unemployment rate | 9.5 | 8.7 | 8.3 | 8.1 | 8.0 |

| Current account balance (balance in % GDP) | 3.3 | 2.3 | 2.7 | 2.8 | 2.8 |

(1) Any inaccuracies are the result of rounding (2) Employment expressed in terms of standard work units (AWU) (3) Number of employed people according to the Continuous Labour Force Survey (Rilevazione Continua delle Forze Lavoro, RCFL) sample survey. |

The forecast assumes a reduction in inflation already in 2023 after the peak expected this year. The consumption deflator would grow by around 2.0 percent in the coming years. The most important factors are the expected trends in energy prices and wages. For the former, the standard approach is to use the prices of futures contracts on gas and oil, which foresee very high levels until spring 2023 and then a gradual decline to levels that, in the case of gas, would be less than half of current prices.

As regards contractual wages, the baseline scenario assumes that, net of the components linked to corporate welfare and productivity bonuses, adjustments to contractual minimum wages will continue to be based on the inflation rate net of imported energy products. Consider, for example, that in March the national consumer price index (NIC) net of energy recorded a year/year growth of 2.5 percent, while the general index grew by 6.7 percent. Assuming that the inflation rate net of energy does not rise very significantly from the level reached in February, future wage increases should be higher than in previous years, but relatively moderate and consistent with an inflation rate of around 2.0 percent in the medium term. Wage earners will regain purchasing power when energy prices fall, and the total inflation rate falls below the energy-adjusted rate6.

Looking at the other main macroeconomic variables, the baseline forecast foresees further growth in employment over the 2023-2025 period and a decline in the unemployment rate to 8.0 percent in 2025 despite a recovery in the labour participation rate. The current account surplus of the balance of payments would widen from 2023 onwards thanks to the expected fall in energy prices and a growth in merchandise exports in line with that of the main outlet markets, as well as the recovery of foreign tourism in Italy.

The baseline macroeconomic forecast was validated by the Parliamentary Budget Office in a note dated 24 March 2022

________________________

6 Consider, for example, that in 2020 the NIC inflation rate was -0.1 percent, while the rate net of energy was +0.6 percent. With energy prices rising, in 2021 the NIC increased by 1.9 percent while the net energy rate increased by 0.8 percent. When energy prices fall, the spread will reverse again.

| MINISTRY OF ECONOMY AND FINANCE | 9 |

| | ITALY’S STABILITY PROGRAMME 2022 |

FOCUS

| The recent evolution of trade relations between Italy and Russia |

Trade relations between Italy and Russia have gone through three distinct periods in recent years. In the first period (referable to years of significant expansion of international trade), exports to Russia grew considerably (from 3.8 to 10.5 billion), doubling as a percentage of total Italian exports (from 1.4 percent in 2002 to 2.8 percent in 2008). At the same time, imports of Russian goods into Italy also grew significantly (from 8 billion to 16 billion), albeit with a less pronounced effect in terms of share of total Italian imports (from 3.0 percent to 4.2 percent). |

Subsequently, in the years of the economic and financial crisis (2008-2013), the share of Italian imports from Russia continued to grow, rising to 5.6 percent in 2013. Italian exports, on the other hand, after the sharp slowdown in 2009 (-20.9 percent globally; -38.6 percent to Russia), slowly returned to pre-crisis levels, as did the share destined for the Russian market (2.8 percent). |

Finally, the third phase (from 2013 to 2021) was characterised by Russia’s military intervention in Crimea, to which the European Union responded with a package of sanctions that grew over time and affected trade levels. Italian imports of Russian goods collapsed in the space of three years (from 20.2 to 10.6 billion in 2016), also falling in terms of incidence on total national imports (from 5.6 percent to 2.9 percent, then orbiting at values just over 3 percent in the following years). The Russian market also appeared less and less central for Italian companies, with an absorption share almost halved over the eight years, from 2.8 percent in 2013 to 1.5 percent in 2021. It is worth noting that, in 2021, the 17.6 billion of imports from Russia produced almost 10 billion of trade deficit, while exports from Italy amounted to only 7.7 billion. |

|

At a sectoral level, sanctions in response to the 2014 Crimean crisis mainly affected imports of crude oil (-3.7 billion) and refined oil products (-2.2 billion). The case of natural gas is different, as Italy has increased its supply from Russia (+1.5 billion between 2013 and 2021, an increase of 19.7 percent), in the presence of a similar increase in relative dependence (from 37.1 percent to 46.6 percent). This result is exclusively attributable to 2021, when natural gas imports from Russia increased by more than 3 billion compared to 2019 (5.3 billion compared to 2020, which is known to be characterized by a sharp slowdown in international trade due to the pandemic crisis), almost entirely to be associated with the last quarter (+2.9 billion). Looking at the 2013-2019 period, on the other hand, Russian gas imports fell by 2.3 percent, with an absolute value of just under 6 billion in both years. |

| 10 | MINISTRY OF ECONOMY AND FINANCE |

II. BASELINE MACROECONOMIC AND BUDGET FORECAST | |

| | In consideration of the objectives of diversification in gas supply, it seems useful to recall Russia’s main competitors in the Italian market. In particular, ISTAT data highlight the role of Algeria, the only country to show values comparable to those of Russia (4.5 billion, equal to 22.8 percent of Italian sector imports); this is followed by Azerbaijan, Qatar (1.8 billion each) and Libya (about 600 million), other potential markets from which to diversify supplies. |

| | |

| | TABLE R1: EVOLUTION OF ITALY’S TRADE WITH RUSSIA BY SECTOR Years 2013 and 2021 (differences in absolute values and market shares on sector total) |

| | | | EXPORTS | IMPORTS |

| | Nace | Activity description | Differences in a.v. (EUR million) | Shares % of sector total | Differences in a.v. (EUR million) | Shares % of sector total |

| | | | 2013 - 2021 | 2013 | 2021 | 2013 – 2021 | 2013 | 2021 |

| | A | AGRICULTURE | -59.9 | 1.6 | 0.4 | 32.3 | 0.9 | 0.9 |

| | B | EXTRACTION | -0.5 | 0.6 | 0.4 | -1,919.4 | 23.4 | 24.6 |

| | | of which: crude oil | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | -3,735.8 | 17.1 | 8.8 |

| | | of which: natural gas | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 1,496.2 | 37.1 | 46.6 |

| | C | MANUFACTURING INDUSTRY | -2,998.0 | 2.8 | 1.6 | -725.2 | 2.2 | 1.4 |

| | CA | Food, beverages and tobacco | 24.5 | 2.2 | 1.4 | -71.9 | 0.7 | 0.4 |

| | CB | Textiles, clothing and footwear | -967.7 | 5.1 | 2.5 | -68.0 | 0.4 | 0.1 |

| | CC | Wood, paper and printing | -122.6 | 2.6 | 0.8 | 96.0 | 1.5 | 2.0 |

| | CD | Refined petroleum products | -1.3 | 0.1 | 0.1 | -2,231.8 | 29.2 | 15.1 |

| | CE | Chemistry | 139.8 | 2.3 | 2.0 | -438.0 | 2.2 | 0.7 |

| | CF | Pharmaceuticals | -11.5 | 1.0 | 0.6 | -1.5 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| | CG | Rubber, plastics, metals processing | -126.6 | 2.2 | 1.3 | 71.5 | 0.2 | 0.5 |

| | CH | Metallurgy and metal products | -163.8 | 1.6 | 0.9 | 1,973.1 | 3.5 | 5.4 |

| | CI | Electronics | -9.5 | 1.3 | 0.8 | 5.4 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| | CJ | Electrical equipment | -194.0 | 3.2 | 1.7 | 8.1 | 0.2 | 0.1 |

| | CK | Mechanics | -745.2 | 4.0 | 2.6 | 1.8 | 0.1 | 0.1 |

| | CL | Transport equipment | -412.1- | 2.2 | 0.8 | -72.1 | 0.3 | 0.0 |

| | CM | Furniture and other manufacturing activities | -408.0 | 4.2 | 1.7 | 2.2 | 0.1 | 0.1 |

| | D-V | OTHER ACTIVITIES | -17.0 | 0.3 | 0.1 | 12.9 | 0.1 | 0.1 |

| | | TOTAL | -3,075.3 | 2.8 | 1.5 | -2,599.4 | 5.6 | 3.7 |

| | Source: elaboration on ISTAT data |

| | |

| | The sanctions of past years have also reduced the presence of Italian companies on the Russian market (over 3 billion in sales in 2021 compared to 2013; -28.6 percent). Among manufacturing sectors, the fashion system has lost almost 1 million in exports during the last eight years, with the share of imports from Russia in the sector’s total cross-border sales more than halved (from 5.1 percent to 2.5 percent). Mechanics and furniture were also hard hit by the sanctions (over 400 million each), although with differing effects in terms of shares (-1.5 percentage points for mechanics and -2.5 percentage points for furniture and other manufacturing activities). On the whole, all Italian manufacturing sectors experienced a clear setback, associating a reduction in sales with a downsizing of the Russian market compared to other destination markets. The only exception was food and beverages, where the growth in exports in value (24 million) was matched by a reduction in the import share (from 2.2 percent to 1.4 percent). |

| MINISTRY OF ECONOMY AND FINANCE | 11 |

| | ITALY’S STABILITY PROGRAMME 2022 |

FOCUS

| Forecast errors for 2021 and revised estimates for 2022 and following years7 |

| |

| This box is aimed at providing an in-depth analysis of the changes introduced in the forecast update with the twofold purpose of i) assessing the forecast error for the year just ended; ii) analysing in greater detail the factors that led to a revision of the growth estimates for 2022 and the following years. In both cases the comparison is made with the forecasts made in the Update of the Stability Programme of last September and in the Draft Budgetary Plan (DBP). |

Table R1, column Delta 2021, shows the forecast error for 2021, i.e., the deviations between the September forecast and the final data published by ISTAT in March. The forecast for 2021 made in September included data from the National Accounts only up to the second quarter of last year, while the data published by ISTAT in March also include information on the second half of last year and the revision of the historical series for previous quarters. |

| With reference to GDP, the final ISTAT data were higher (0.6 percentage points) than expected, showing annual growth of 6.6 percent. The data confirms the quarterly growth profile defined in the DBP, which envisaged further expansion in the third quarter followed by a slowdown in the final quarter of the year. In fact, economic activity continued to grow at a high pace in Q3, in line with that recorded in Q2. Growth benefited from the easing of restrictions made possible by the acceleration of the vaccination campaign. In the last segment of 2021, economic activity slowed down due to higher energy prices and the effects of the fourth Covid wave. |

| |

| | TABLE R1 – MAIN VARIABLES OF THE MACROECONOMIC FRAMEWORK (average of seasonally adjusted quarterly data) |

| | | 2021 forecast | 2022 forecast | of which: Revised carry-over to 2022 compared to DBP | of which: Exogenous impact compared to DBP | of which: Revision of forecast |

| | | DBP | ISTAT | Delta 2021 | DBP | Stability Programme 2022 | Delta 2022 | (a) | (b) | (c) |

| | ITALY’S MACROS | | | | | | | | | |

| | GDP | 6.0 | 6.6 | 0.6 | 4.8 | 3.0 | -1.8 | 0.2 | -1.6 | -0.4 |

| | Household expenditure | 5.2 | 5.2 | 0.0 | 5.0 | 2.9 | -2.1 | -0.5 | -1.7 | 0.1 |

| | General Government expenditure | 0.7 | 0.6 | -0.1 | 1.7 | 1.2 | -0.5 | 0.2 | -0.1 | -0.6 |

| | Gross fixed capital formation | 15.5 | 17.0 | 1.5 | 6.8 | 7.0 | 0.2 | 1.8 | -2.4 | 0.8 |

| | Machinery, equipment and miscellaneous | 10.0 | 12.9 | 2.9 | 6.6 | 6.5 | -0.1 | 2.0 | -2.9 | 0.9 |

| | Construction | 20.9 | 22.3 | 1.4 | 6.5 | 8.7 | 2.1 | 3.0 | -1.7 | 0.9 |

| | | | | | | | | | | |

| | Exports of goods and services | 11.4 | 13.4 | 1.9 | 6.1 | 4.4 | -1.6 | 0.7 | -1.8 | -0.6 |

| | Imports of goods and services | 11.6 | 14.3 | 2.7 | 6.8 | 5.5 | -1.3 | 2.2 | -1.2 | -2.4 |

| | Deflators | | | | | | | | | |

| | GDP deflator | 1.5 | 0.5 | -1.0 | 1.6 | 3.0 | 1.4 | -1.0 | 0.2 | 2.2 |

| | Consumption deflator | 1.5 | 1.6 | 0.2 | 1.6 | 5.8 | 4.3 | 0.5 | 2.4 | 1.4 |

________________________

7 This box refers to quarterly income statement data published on 4 March 2022 that are working day adjusted.

| 12 | MINISTRY OF ECONOMY AND FINANCE |

II. BASELINE MACROECONOMIC AND BUDGET FORECAST | |

| | In terms of components, household consumption was in line with the forecast, while exports and investment, particularly in machinery and equipment, increased more than estimated; the gap is significantly positive for import growth. On the price front, there was a markedly higher than expected increase in import prices, as triggered by increases in the energy component in the second half of the year. The change in the consumption deflator was slightly higher than forecast (0.2 percent), while the actual change of the GDP deflator was 1.0 percentage point lower than estimated. |

| | In the analysis of the growth revision for 2022, the following steps have been taken: firstly, the statistical reasons for the change in the carry-over effect from 2021 have been analysed, followed by the deltas resulting from the new assumptions on the international scenario and then the revision of the forecast. |

| | Column ‘a’ shows the difference in the statistical carry-over effect from 2021 to 2022 between the value estimated in the last official update and the actual value. For GDP, the change in the carry-over effect is positive and amounts to 0.2 percentage points. The carry-over effect is affected by the higher-than-expected outcome in the second half of 2022, as noted above. |

| | The component due to the revision of the international scenario with respect to October is explained in column ‘b’, which shows the impact on the main variables estimated with the Treasury Department’s econometric model. The impact on GDP is significantly negative and reflects the deterioration of the international environment linked to the Russian-Ukrainian conflict. The latter has exacerbated critical conditions in the energy market, further increasing supply costs, and contributed to a deterioration in international trade. |

| | Column ‘c’ indicates the revision of the forecast which, for the percentage change in GDP, amounts to -0.4 percentage points. |

| | Table R2 provides a summary of the impact on GDP growth of developments in the international environment, comparing it with what was assumed in the September 2021 DBP. Such impact, estimated using the ITEM econometric model, is more unfavourable than September forecasts and amounts to -1.6 percentage points in 2022, -1.1 percentage points in 2023 and -0.4 percentage points in 2024, respectively. |

| | In detail, compared to the forecast underlying the DBP, international trade has been revised downwards sharply for 2022-23, with a more pronounced decline in the first year, before recovering in 2024. As a result, the effect of the revision of the global demand forecast on the rate of change of GDP is negative in both 2022 (-0.3 percent) and 2023 (-0.1 percent) and slightly positive in 2024 (0.1 percent). |

| | |

| | TABLE R2: EFFECTS ON GDP OF THE INTERNATIONAL SCENARIO COMPARED TO THE DBP (impact on growth rates) |

| | | 2022 | 2023 | 2024 |

| | 1. World trade | -0.3 | -0.1 | 0.1 |

| | 2. Oil and gas prices | -0.8 | -0.5 | 0.0 |

| | 3. Nominal effective exchange rate | -0.1 | -0.2 | 0.0 |

| | 4. Interest rate assumptions and financial effects | -0.2 | -0.3 | -0.6 |

| | 5. Sanctions against Russia | -0.2 | -0.1 | 0.1 |

| | Total | -1.6 | -1.1 | -0.4 |

| | Source: MEF calculations. |

| | |

| | In the first months of this year, oil prices maintained the upward trend that had emerged at the end of 2021, exacerbated by tensions arising from the Russian-Ukrainian conflict. The current projection, based on futures contracts, forecasts higher oil price levels over the entire three-year period. In particular, a peak of USD 99.8 per barrel is expected in 2022, followed

|

| MINISTRY OF ECONOMY AND FINANCE | 13 |

| | ITALY’S STABILITY PROGRAMME 2022 |

| | by a moderation in 2023 and 20248. Compared to what was projected in September, the price level is higher on average by about USD 26 over the three-year period. In the light of recent developments on the Ukrainian front, the need to consider among the exogenous variables also the price of gas has emerged, which has recorded very significant increases. The assumptions made concern the TTF gas price profile and are based on futures contracts. Specifically, the price in 2022 would reach levels four times higher than those extrapolated from contracts temporally consistent with the September Document, and then decline in subsequent years while remaining at levels much higher than those recorded in the recent past. Cumulating the effects of oil and gas price increases would result in a negative impact of 8 tenths of a point for the GDP rate of change in 2022, 5 tenths of a point in 2023 and no impact in 2024. |

| | On the exchange rate front, a technical assumption was adopted for the currency projection, which implies that the exchange rate remains unchanged over time and is equal to the average of the last 10 working days ending 10 March. The update of the nominal effective exchange rate, in comparison with September, sees an appreciation of the euro against other currencies of 0.3 percent in 2022 and 0.1 percent in 2023. The macroeconomic impact of this update of the exchange rate forecast is negative by one tenth of a percentage point on GDP growth in 2022 and two tenths in 2023. |

| | The profile of interest rates on government bonds is increasingly unfavourable over the three-year period, consistently with expectations of less accommodating policies by monetary authorities to counter inflationary pressures. In addition, higher BTP yields and a higher spread between the 10-year BTP and Bund are already expected this year, combined with higher bank credit costs. The econometric model estimates these factors to have negative effects on growth over the three-year period of -0.2 percentage points in 2022, -0.3 points in 2023 and -0.6 points in 2024, respectively. |

| | Finally, the imposition of sanctions on Russia following the outbreak of hostilities with Ukraine was also considered to be one of the revisions to the international framework that induced changes in the growth profile. Such restrictions would weaken trade by deteriorating foreign demand for domestic goods in proportion to direct export exposure to Russia. The estimated impact on the GDP rate of change is -0.2 and -0.1 percentage points in 2022 and 2023, respectively, and 0.1 in 2024. |

| | The DBP growth forecasts have been validated by the Parliamentary Budget Office. The latter in February, following the publication of ISTAT’s flash estimate for GDP in the fourth quarter, published a GDP growth forecast of 3.9 percent in 2022 and 1.9 percent in 2023. |

| | Compared to the European Commission’s most recent estimates (Winter Forecast), baseline GDP growth for 2022 is less pronounced (2.9 percent compared to 4.0 percent), while for 2023 baseline growth is 2.3 percent in both cases. In 2022, the European Commission’s estimate does not incorporate the latest international developments. In 2022, there is no mismatch between the growth estimated in the DBP and that of the European Commission and in general with those of other forecasters. |

| | |

| | TABLE R3: GROWTH FORECASTS FOR ITALY |

| | Real GDP (%y/y) | Forecast date | 2022 | 2023 |

| | Stability Programme 2022 | Mar-22 | 2.9 | 2.3 |

| | OECD | Dec-21 | 4.6 | 2.6 |

| | UPB | Feb-22 | 3.9 | 1.9 |

| | IMF (WEO) | Jan-22 | 3.8 | 2.2 |

| | European Commission | Feb-22 | 4.1 | 2.3 |

| | (*) For OECD adjusted data for working days. |

________________________

8 This refers to the average of futures over the last ten business days ending 10 March 2022..

| 14 | MINISTRY OF ECONOMY AND FINANCE |

II. BASELINE MACROECONOMIC AND BUDGET FORECAST | |

II.2 RISKS TO THE BASELINE MACROECONOMIC FORECAST

As usual, the baseline forecast was subjected to risk analysis on some key variables of the forecast (see the Focus entitled “A risk analysis on the geopolitical situation and exogenous variables”). In addition, in view of recent events, a risk scenario related to the war in Ukraine, and in particular the possibility that a further tightening of sanctions would lead to the interruption of gas and oil inflows from Russia, was explored.

The impact of a possible blockade of Russian gas and oil exports on production activities and on the prices of fossil energy sources and electricity would depend on several factors, including the timing of such an event, the level of gas stocks in Italy and Europe at the time of the interruption, and the geopolitical and military context in which it occurred.

In the simulation carried out, an export freeze was assumed to start at the end of April 2022 and last through 2023. Evaluations carried out with the contribution of experts in the sector lead to the hypothesis, with reference to the solar year rather than the thermal year, of an annual consumption in Italy of 74 billion standardised cubic metres in 2022 (against 77.1 billion in 2021) and 72.5 billion in 2023.

Based on these assessments, a first scenario assumes that companies in the sector would be able to secure the gas supplies the country needs thanks to an increase in imports from southern pipelines, an increased use of LNG (regasification capacity would increase significantly already in 2023) and an increase, initially modest, but growing over time, in domestic production of natural gas and biomethane.

However, if other European countries were to make similar efforts to diversify their supplies, this would lead to a much higher price increase than that incorporated in the exogenous components of the baseline macroeconomic framework.

The second risk scenario assumes that not all actions taken to diversify gas supplies will produce the desired results due to technical, climatic, and geopolitical issues, and that other EU countries will also face gas shortages. For Italy, gas shortages are assumed to be 18 percent of volume imports in 2022 and 15 percent of imports in 20239. As in the previous simulation, the decline in activity in the destination countries of Italian exports was also considered.

The simulation results show a fall in GDP compared to the baseline scenario of 2.3 percentage points in 2022 and 1.9 in 2023. Employment would be 1.3 percentage points lower this year and 1.2 percentage points in 2023. The consumption deflator would grow by 1.8 percentage points more this year and 2.4 percentage points in 2023. Assuming energy prices recover in the following two years and GDP returns to trend in 2025, the GDP growth rate would be 1.9 percentage points higher in 2024 and 2.3 percentage points in 2025.

________________________

9 The comparison between 2022 and 2023 is consistent with the assumption of significant progress in diversifying gas supply sources, as in 2022 Russian gas will still have been imported for four months, while in 2023 inflows from Russia would be zero. It should also be noted that, in line with the macroeconomic forecast, the analysis of gas supplies was carried out on a calendar year basis. The gas market, on the other hand, is based on the thermal year starting on 1 October. In the assumed scenario, it would be the thermal year 2022-2023 that would present the greatest supply difficulties.

| MINISTRY OF ECONOMY AND FINANCE | 15 |

| | ITALY’S STABILITY PROGRAMME 2022 |

Thus, in the worst-case scenario real GDP growth in 2022 would be 0.6 percent and 0.4 percent in 2023. As 2022 inherits 2.3 percentage points of growth from 2021, GDP growth in 2022 would be clearly negative, while the consumption deflator would grow by 7.6 percent. These assessments refer to the baseline scenario, as such a worst-case scenario would be met with a more robust economic support measure than that assumed in the policy scenario of this Document.

FOCUS

| A risk analysis of the geopolitical situation and exogenous variables |

| Using both the ITEM econometric model and the MACGEM-IT computational general equilibrium model, four different risk scenarios were considered for the baseline forecast, two of which related to the interruption of gas supplies from Russia following a tightening of sanctions, and the others to other specific macroeconomic risk factors. |

| For the two Russian gas embargo scenarios, the gas import blockade is assumed to occur from the end of April 2022 and to last through 2023. The first scenario assumes that companies in the sector manage to meet the demand by diversifying their supplies, even if the embargo causes gas, electricity, and oil prices to rise further than in the baseline scenario. In particular, the price of gas is assumed to be 37 percent higher in 2022 than in the baseline scenario (69 percent in 2023), the price of oil 9 percent higher (4.5 percent in 2023) and the price of electricity 30 percent higher (58 percent in 2023). Using the MACGEM-IT model, the impact of higher prices on output levels was determined, taking into account the use of energy materials in different sectors and inter-sectoral linkages. Moreover, as the embargo affects other European countries as well, the scenario also considers the effects of a drop in their activities due to the sharp rise in energy prices, leading to lower foreign demand. |

| In the second scenario, it is assumed that diversification efforts in supply do not have the expected results due to various difficulties. The interruption in gas supplies from Russia is therefore accompanied not only by an even more pronounced increase in gas, electricity, and oil prices (+10 percent on average compared to what was already assumed in the first scenario), but also by a shortage of gas, estimated at 18 percent and 15 percent of imports in volume in 2022 and 2023 respectively. The effects of the activity drop in European trading partners are also considered. |

| The third simulation concerns exchange rates. In the alternative scenario, they were set, over the forecast horizon, at levels corresponding to the average forward exchange rates over the most recent period (over the 10 days starting from 3 March 2021). This would result in a lower appreciation of dollars against euros in 2022 compared to the baseline scenario (by 4.8 percent instead of 6.3 percent). Moreover, while the nominal effective exchange rate remains broadly unchanged in the baseline scenario, in this simulation the euro would appreciate against other currencies by an average of about 0.3 percent in 2022 and 2.3 percent in 2023. In 2024 and 2025, the appreciation would be 3.2 and 0.8 percent, respectively. |

| The fourth and final simulation refers to risk factors related to the financial condition of the economy. Compared to the baseline scenario, the level of the 10-year BTP yield rate is assumed 100 basis points higher. These less favourable conditions for financing public debt do not affect the current year, but only the subsequent ones, due to the central bank’s ongoing programme of purchases of financial securities, which helps to limit the risk of tensions in the financial markets. In this alternative scenario, higher levels of the BTP-Bund spread starting from 2023 translate into less favourable conditions for access to credit, with higher interest rates applied to loans to households and businesses. |

| | The assessment of the impact on economic activity levels of the above risk elements is documented in Table R4. Under the first scenario hypothesis for the interruption of gas flows from Russia, the GDP growth rate would be lower than in the baseline scenario by 0.8 |

| 16 | MINISTRY OF ECONOMY AND FINANCE |

II. BASELINE MACROECONOMIC AND BUDGET FORECAST | |

| | percentage points in 2022 and 1.1 points in 2023. The recovery in the following years, with growth rates higher than in the baseline scenario (1.1 and 0.8 percent, respectively), means that the level of GDP in early 2025 is in line with the corresponding level in the baseline scenario. In the other, even more unfavourable, Russian gas embargo scenario, higher energy prices, lower gas availability for households and lower foreign demand would determine a contraction of the output growth rate relative to the baseline scenario by 2.3 percentage points in 2022 and 1.9 percentage points in 2023. In contrast, the GDP growth rate would be 1.9 percentage points higher than in the baseline in 2024 and 2.3 points higher in 2025. |

| | Regarding exchange rates, the higher appreciation of the euro relative to the baseline scenario would reduce the GDP growth rate relative to the baseline scenario by 0.4 percent in 2023, 0.8 percent in 2024 and 0.6 percent in 2025. This simulation does not include any assumptions about the partial block of Italy’s trade with Russia, therefore the effects on both exports and GDP of an appreciation of the euro (due, to a large extent, to the appreciation against the rouble) could be to some degree overestimated. Assuming worse financial conditions from 2023 onwards would determine a negative impact on the growth profile of the Italian economy. In particular, the GDP growth rate would be 0.1 percentage points lower in 2023 than in the baseline scenario and 0.4 and 0.5 points lower in 2024 and 2025, respectively. |

| | |

| | TABLE R1: EFFECTS OF RISK SCENARIOS ON GDP (impact on percentage growth rates compared to the baseline macroeconomic scenario) |

| | | 2022 | 2023 | 2024 | 2025 |

| | 1. Interruption of gas inflows from Russia: 1st scenario | -0.8 | -1.1 | 1.1 | 0.8 |

| | 2. Interruption of gas inflows from Russia: 2nd scenario | -2.3 | -1.9 | 1.9 | 2.3 |

| | 3. Nominal effective exchange rate | 0.0 | -0.4 | -0.8 | -0.6 |

| | 4. Assumption of worse financial conditions | 0.0 | -0.1 | -0.4 | -0.5 |

| | Source: MEF-TD calculations; ITEM and MACGEM-IT models. |

II.3 BUDGETARY OUTLOOK UNDER EXISTING LEGISLATION

Starting from the positive public finance results achieved in 2021, the baseline forecast of the general government net borrowing for 2022 is revised downward with respect to the Update of the Stability Programme and the Draft Budgetary Plan (DBP) policy scenario, from 5.6 percent to 5.1 percent of GDP. The general government account in the baseline scenario (under existing legislation) includes the measures to lower bills for households and businesses that the Government introduced with the 2022 Budget Law and the decree-laws adopted in the past three months, to which industrial policy measures must be added. To cover the measures, inter alia, ministerial expenditure was cut by 4.5 billion and an extraordinary tax on the profits of energy companies of 3.9 billion was introduced.

Moreover, as mentioned above, GDP is now projected to grow by 6.0 percent in nominal terms in 2022, compared to 6.4 percent in the DBP. Ceteris paribus, this would result in a negative impact on general government revenues. However, while the upward revision of the inflation forecast leads to higher interest payments on government bonds indexed to consumer prices and inflation-indexed expenditures, it also pushes up revenues from indirect taxes.

Overall, the downward revision of the 2022 net borrowing estimate is mainly due to higher tax, social security contributions and other current revenues, which

| MINISTRY OF ECONOMY AND FINANCE | 17 |

| | ITALY’S STABILITY PROGRAMME 2022 |

offset to a greater extent higher estimate of current and capital expenditure compared to the DBP. However, the tax burden calculated according to national accounts criteria is expected to fall from 43.5 percent in 2021 to 43.1 percent of GDP this year. Moreover, when correcting the data to take into account the classification of various tax and social security contribution reductions as expenditure measures, the actual tax burden is lower and falls slightly more, from 41.7 last year to 41.2 this year.

As regards the next three-year period, the general government account under existing legislation benefits from a significant reduction in relation to GDP of both current primary expenditure (from 45.0 percent in 2022 to 42.0 percent in 2025) and interest expenditure (from 3.5 percent to 3.0 percent, also thanks to the expected decline in consumer inflation), while general government gross fixed capital formation is expected to rise from 3.1 percent to 3.6 percent of GDP. On the revenue side, the tax burden would fall to 42.2 percent of GDP in 2025, while final revenues would fall from 48.5 percent of GDP in 2022 to 46.9 percent in 2025.

As a result of these changes, the general government net borrowing in the baseline scenario is expected to decrease from 5.1 percent of GDP in 2022 to 3.7 percent in 2023 and then to 3.2 percent in 2024 and 2.7 percent in 2025.

| 18 | MINISTRY OF ECONOMY AND FINANCE |

| III. | UPDATED POLICY SCENARIO |

III.1 FISCAL POLICY SCENARIO

The fiscal policy for 2022 outlined a year ago in the Stability Programme, subsequently clarified in the Draft Budgetary Plan (DBP) and then implemented with the Budget Law, is based on the consideration that the revival of the Italian economy after years of slow growth and the unprecedented slump in 2020 requires a prudent but expansive fiscal policy - albeit with the expectation that the NRRP will produce a gradually increasing momentum to the country’s sustainable development.

Therefore, according to the approach adopted in the 2022 Budget Law, Italy’s fiscal policy shall remain expansionary until the GDP gap, with respect to the pre-crisis trend, is fully closed. The gradually less expansionary stance of the fiscal policy will lead to a gradual decline in the deficit, a significant reduction in the debt-to-GDP ratio, an improvement in the quality of public spending and the recovery of revenues thanks to a shrinking tax gap.

The fiscal space obtained by adopting a more gradual deficit reduction path, compared to the baseline, has been allocated to a reform of the Personal Income Tax (Imposta sui Redditi delle Persone Fisiche, IRPEF), the Regional Tax on Production Activities (Imposta regionale sulle attività produttive, IRAP), and of social benefits, funding credit guarantees and public investment, as well as raising the resources for the Citizenship Income scheme. In addition, funding for health and pandemic response has been increased and a substantial reduction in energy costs for households and businesses has been implemented. The universal child benefit has been fully implemented.

As described in detail above, higher energy prices at the beginning of the year had the hardest impact on businesses and household budgets. As a result, the Government has taken action with further price containment measures. Interventions have also been, and are being, financed to support the automotive sector, and in particular the sales of environment-friendly cars, as well as the semiconductor sector.

The recent measures implemented by the Government are in line with the guidelines issued by the European Commission, which recognise, on the one hand, the need to cushion the impact on the economy of the increases in the price of natural gas and oil caused by the war in Ukraine, and, on the other, the importance of supporting strategic industrial sectors in the face of non-European competition, which is also based on substantial State aid.

In this context, in light of the lowering of the baseline net borrowing forecast to 5.1 percent of GDP, the Government has decided to confirm the deficit-to-GDP ratio target of the DBP (5.6 percent of GDP), and to use the resulting margin of approximately 0.5 percentage points of GDP to finance a new measure, to be

| MINISTRY OF ECONOMY AND FINANCE | 19 |

| | ITALY’S STABILITY PROGRAMME 2022 |

finalised in April. First of all, the new Decree-Law will restore budgetary funds temporarily de-funded to partially cover Decree-Law No. 17/2022, amounting to 4.5 billion in terms of impact on the general government net borrowing. The remaining resources will be allocated to the following interventions:

| • | the increase in funds for credit guarantees. |

| • | the increase in resources needed to cover the rise in prices of public works. |

| • | further action to contain fuel prices and energy costs. |

| • | further measures that are necessary to assist Ukrainian refugees and to alleviate the economic impact of the ongoing conflict in Ukraine on Italian companies. |

| • | continuing to support the health system’s response to the pandemic and the sectors most affected by the pandemic emergency. |

In addition, general government net borrowing targets for 2023 and 2024, which were revised under a meliorative filter in the 2022 DBP, are confirmed: 3.9 percent of GDP in 2023 and 3.3 percent of GDP in 2024. For 2025, the new deficit target is set at 2.8 percent of GDP. Based on the baseline public finance projections under existing legislation outlined above, this creates room to finance expansionary measures of 0.2 percent of GDP in 2023 and 0.1 percent in 2024 and 2025.

The public finance baseline projection described in the previous chapter does not include the so-called unchanged policies, which include a series of expenditures that may have to be implemented in the coming years due to international commitments or legislative factors, from the refinancing of international missions to the financing of future contract renewals in the general government sector. The central State administrations will contribute to the financing of these needs and new measures that the Government will decide to adopt with the end-of-year manoeuvre, through a renewed spending review activity. This is also in view of the fact that for the 2023-2025 three-year period, the resumption of the procedure provided for by Article 22-bis of Law No. 196 of 2009 is configured as one of the enabling reforms of the NRRP (reform 1.13).

To this end, the expenditure savings to be ensured by the central State administrations for the three-year planning period are indicated, according to an increasing profile, as 800 million for the year 2023, 1,200 million for the year 2024 and 1,500 million for the year 2025. The distribution among ministries and the areas of intervention will be identified by a decree of the President of the Council of Ministers (by 31 May) on the proposal of the Minister of Economy and Finance, after deliberation by the Council of Ministers.

| 20 | MINISTRY OF ECONOMY AND FINANCE |

III. UPDATED POLICY SCENARIO | |

| TABLE III.1: PUBLIC FINANCE INDICATORS (as a percentage of GDP)(1) |

| | 2020 | 2021 | 2022 | 2023 | 2024 | 2025 |

| POLICY SCENARIO | | | | | | |

| Net borrowing | -9.6 | -7.2 | -5.6 | -3.9 | -3.3 | -2.8 |

| Primary balance | -6.1 | -3.7 | -2.1 | -0.8 | -0.3 | 0.2 |

| Interest expense | 3.5 | 3.5 | 3.5 | 3.1 | 3.0 | 3.0 |

| Structural net borrowing (2) | -5.0 | -6.1 | -5.9 | -4.5 | -4.0 | -3.6 |

| Structural variation | -3.0 | -1.1 | 0.2 | 1.4 | 0.5 | 0.4 |

| Public debt (gross of subsidies) (3) | 155.3 | 150.8 | 147.0 | 145.2 | 143.4 | 141.4 |

| Public debt (net of subsidies) (3) | 151.8 | 147.6 | 144.0 | 142.3 | 140.7 | 138.8 |

| | | | | | | |

| BASELINE SCENARIO UNDER EXISTING LEGISLATION | | | | | | |

| Net borrowing | -9.6 | -7.2 | -5.1 | -3.7 | -3.2 | -2.7 |

| Primary balance | -6.1 | -3.7 | -1.6 | -0.6 | -0.2 | 0.2 |

| Interest expense | 3.5 | 3.5 | 3.5 | 3.1 | 3.0 | 3.0 |

| Structural net borrowing (2) | -5.0 | -6.1 | -5.3 | -4.3 | -3.8 | -3.4 |

| Structural variation | -3.0 | -1.1 | 0.8 | 1.1 | 0.5 | 0.3 |

| Public debt (gross of subsidies) (3) | 155.3 | 150.8 | 146.8 | 145.0 | 143.2 | 141.2 |

| Public debt (net of subsidies) (3) | 151.8 | 147.6 | 143.8 | 142.1 | 140.5 | 138.6 |

| | | | | | | |

| MEMO: Update of the Stability Programme 2021/ DBP 2022 (POLICY SCENARIO) |

| Net borrowing | -9.6 | -9.4 | -5.6 | -3.9 | -3.3 | |

| Primary balance | -6.1 | -6.0 | -2.6 | -1.2 | -0.8 | |

| Interest expense | 3.5 | 3.4 | 2.9 | 2.7 | 2.5 | |

| Structural net borrowing (2) | -4.7 | -7.6 | -5.4 | -4.4 | -3.8 | |

| Variation in structural balance | -2.9 | -2.9 | 2.1 | 1.0 | -0.6 | |

| Public debt (gross of subsidies) | 155.6 | 153.5 | 149.4 | 147.6 | 146.1 | |

| Public debt (net of subsidies) | 152.1 | 150.3 | 146.4 | 144.8 | 143.3 | |

| Nominal baseline GDP (absolute values x 1000) | 1657.0 | 1775.4 | 1882.7 | 1966.2 | 2037.6 | 2105.7 |

| Policy nominal GDP (absolute values x 1000) | 1657.0 | 1775.4 | 1887.0 | 1974.5 | 2048.3 | 2116.8 |

(1) Any inaccuracies are the result of rounding. (2) Net of one-time measures and the cyclical component. (3) Gross or net of Italy’s share of loans to EMU Member States, bilaterally or through the EFSF, and of the contribution to the capital of the ESM. As of 2021, the amount of these shares was approximately 57.3 billion, of which 43.0 billion for bilateral loans and through the EFSF and 14.3 billion for the ESM programme (see Bank of Italy, “Statistical Bulletin Public Finance, Cash Requirements and Debt”, March 2022). It is assumed that the MEF’s cash holdings will be reduced by approximately -0.2 percent of GDP in 2022 and by approximately -0.1 percent of GDP in each subsequent year, with the aim of bringing the balance back to the level of the end of 2019. In addition, estimates take into account the repurchase of SACE, the deployment of the earmarked assets, EIB guarantees and loans under the SURE and NGEU programmes. The interest rate scenario used for the estimates is based on the implicit forecasts derived from the forward rates on Italian government bonds for the period in which this Document was completed. |

III.2 MACROECONOMIC FORECAST UNDER THE POLICY SCENARIO

The measures envisaged in the policy scenario and to be adopted in April will have an expansionary effect on the Italian economy and will increase the change in GDP projected in the policy scenario to 3.1 percent in 2022 (from 2.9 percent in the baseline scenario) and to 2.4 percent in 2023 (from 2.3 percent in the baseline scenario).

| MINISTRY OF ECONOMY AND FINANCE | 21 |

| | ITALY’S STABILITY PROGRAMME 2022 |

The higher resources allocated support households and firms and contribute to increasing (compared to the baseline scenario) investment by 0.3 percent and household consumption by about 0.1 percentage points this year. In the following year, household consumption in the macroeconomic policy framework grows by 2.1 percent (in line with the baseline scenario) and total gross fixed capital formation by 5.5 percent (0.4 percentage points higher than in the baseline scenario). The improved demand performance triggers higher imports in 2023 on the one hand and promotes labour input growth on the other.

The policy scenario expects a higher employment and lower unemployment rate than the baseline scenario, which stands at 8.1 percent in 2023, and then declines further to 8.0 percent in 2024 and 7.9 percent in 2025.

GDP growth projections for 2024 and 2025 remain broadly unchanged from those in the baseline scenario. In other aspects, the differences between the policy scenario and the baseline scenario are limited, as the deficit differential is large this year but narrows in the next three years until essentially disappearing in 2024-2025.

| TABLE III.2: SYNTHETIC MACROECONOMIC POLICY SCENARIO (1) (percentage changes, unless otherwise indicated) |

| | 2021 | 2022 | 2023 | 2024 | 2025 |

| GDP | 6.6 | 3.1 | 2.4 | 1.8 | 1.5 |

| GDP deflator | 0.5 | 3.0 | 2.2 | 1.9 | 1.8 |

| Consumption deflator | 1.7 | 5.8 | 2.1 | 1.8 | 1.8 |

| Nominal GDP | 7.2 | 6.3 | 4.6 | 3.7 | 3.3 |

| Employment (AWU) (2) | 7.6 | 2.6 | 2.3 | 1.6 | 1.3 |