As required by Form 18-K, The Republic of Italy's most recent budget is filed as an exhibit to this Annual Report. In addition, other Italian Government budgetary papers may from time to time be filed as exhibits to amendments to this Annual Report. This Annual Report, any amendments hereto and exhibits hereto contain or may contain budgetary papers or other forward-looking statements that are not historical facts, including statements about the Italian Government's beliefs and expectations for the forthcoming budget period. Forward-looking statements are contained principally in the sections titled "The Italian Economy", "Monetary System" and "Public Finance." Forward-looking statements can generally be identified by the use of terms such as "will", "may", "could", "should", "would", "expect", "intend", "estimate", "anticipate", "believe", "continue", "project", "aim" or other similar terms. These forward-looking statements include, but are not limited to, statements relating to:

Those statements are or will be based on plans, estimates and projections that are current only as of the original date of release by the Italian Government of those budgetary papers and speak only as of the date they are so made. The information included in those budgetary papers may also have changed since that date. In addition, these budgets are prepared for government planning purposes, not as future predictions, and actual results may differ and have in fact differed, in some cases materially, from results contemplated by the budgets or other forward-looking statements. Therefore, those forward-looking statements are not a guarantee of performance and you should not rely on the information in those budgetary papers or forward-looking statements. If the information included or incorporated by reference in this Annual Report differs from the information in those budgetary papers or forward-looking statements, you should consider only the most current information included in this Annual Report, any amendments hereto and exhibits hereto. Certain figures regarding prior fiscal years have been updated to reflect more recent data that were not previously available. You should read all the information in this Annual Report.

There are important factors that could cause actual outcomes to differ materially from those expressed or implied in the forward-looking statements. These factors include, but are not limited to:

We use terms in this Annual Report that may not be familiar to you. These terms are commonly used to refer to economic concepts that are discussed in this Annual Report. Set forth below are some of the terms used in this Annual Report.

Amounts included in this Annual Report are normally rounded. In particular, amounts stated as a percentage are normally rounded to the first decimal place. Totals in certain tables of this Annual Report may differ from the sum of the individual items in such tables due to rounding.

The source for most of the financial and demographic statistics for Italy included in this Annual Report is data prepared by Istituto Nazionale di Statistica, or ISTAT, an independent Italian public agency that produces statistical information regarding Italy (including GDP data), in particular financial and demographic statistics for Italy published in the Annual Report of ISTAT dated July 7, 2023 and appendices thereto (together the "2023 ISTAT Annual Report") and elaborations on such data and other data published in the Annual Report of the Bank of Italy (Banca d'Italia, Italy's central bank) dated May 31, 2023 and appendices thereto (together the "2023 Bank of Italy Annual Report"). We also include in this Annual Report information published by the Statistical Office of the European Communities or Eurostat.

Certain other financial and statistical information contained in this Annual Report has been derived from other Italian Government sources, including: (i) the economic and financial document of 2023 (Documento di Economia e Finanza 2023), dated April 11, 2023 (the "2023 Economic and Financial Document"), which includes the 2023 stability programme (the "2023 Stability Programme") and the 2023 national reform programme (the "2023 National Reform Programme"), filed by paper under cover of Form SE as Exhibits 2, 3 (condensed English version of the 2023 Stability Programme), 4 and 5 (condensed English version of the 2023 National Reform Programme), respectively, to this Annual Report; (ii) the update of the 2023 Economic and Financial Document (Nota di Aggiornamento del Documento di Economia e Finanza 2022), dated September 27, 2023 (the "Update of the 2023 Economic and Financial Document") filed as Exhibit 6 to this Annual Report (condensed English version of the Update of the 2023 Economic and Financial Document filed as as Exhibit 7 to this Annual Report); and (iii) the Report on Public Debt in 2022 (Rapporto sul Debito Pubblico 2022), dated August 3, 2023 (the "2022 Report on Public Debt") filed as Exhibit 8 to this Annual Report.

In 1999, ISTAT introduced a new system of national accounts in accordance with the new European System of Accounts (ESA95) as set forth in European Union Regulation 2223/1996. This system was intended to contribute to the harmonization of the accounting framework, concepts and definitions within the European Union. Under ESA95, all European Union countries apply a uniform methodology and present their results on a common calendar. Both state sector accounting and public sector accounting transactions are recorded on an accrual basis. Since introducing the ESA95 accounting system, ISTAT has published revisions to the national system of accounts, including replacing its methodology for calculating real growth, which had been based on a fixed base index, with a methodology linking real growth between consecutive time periods, or a chain-linked index.

Effective September 2014, ISTAT has adopted a new system of national accounts in accordance with the new European System of National and Regional Accounts (ESA2010) as set forth in European Union Regulation 549/2013. ESA2010 has introduced several key differences from its predecessor ESA95, reflecting certain developments in the methodological and statistical tools widely used at international level to measure modern economies. Unless otherwise provided in this Annual Report, Italy's GDP data were prepared in accordance with the ESA2010 accounting system. For additional information regarding Italy's accounting methodology, see "Public Finance—Accounting Methodology".

All references herein to "Italy," the "State" or the "Republic" are to The Republic of Italy, all references herein to the "Government" are to the central Government of The Republic of Italy and all references to the "general government" are collectively to the central Government and local government sectors and social security funds (those institutions whose principal activity is to provide social benefits), but exclude government owned corporations. In addition, all references herein to the "Treasury" or the "Ministry of Economy and Finance" are interchangeable and refer to the same entity.

The following summary is qualified in its entirety by, and should be read in conjunction with, the more detailed information appearing elsewhere in this Annual report, any amendments hereto and annexes hereto.

businesses for energy costs and a cap on excise taxes on petrol and diesel fuel; and (ii) extension until March 31, 2023 of installment plans for payment of energy utilities in favor of certain businesses.

REPUBLIC OF ITALY

Area and Population

Geography. Italy is situated in south central Europe on a peninsula approximately 1,200 kilometers (745.645 miles) long and includes the islands of Sicily and Sardinia in the Mediterranean Sea and numerous smaller islands. To the north, Italy borders on France, Switzerland, Austria and Slovenia along the Alps, and to the east, west and south it is surrounded by the Mediterranean Sea. Italy’s total area is approximately 302,068 square kilometers (116,629 square miles), and it has 8,970 kilometers (5,574 miles) of coastline. The independent States of San Marino and Vatican City, whose combined area is approximately 61 square kilometers (24 square miles), are located within the same geographic area. The Apennine Mountains running along the peninsula and the Alps north of the peninsula give much of Italy a rugged terrain.

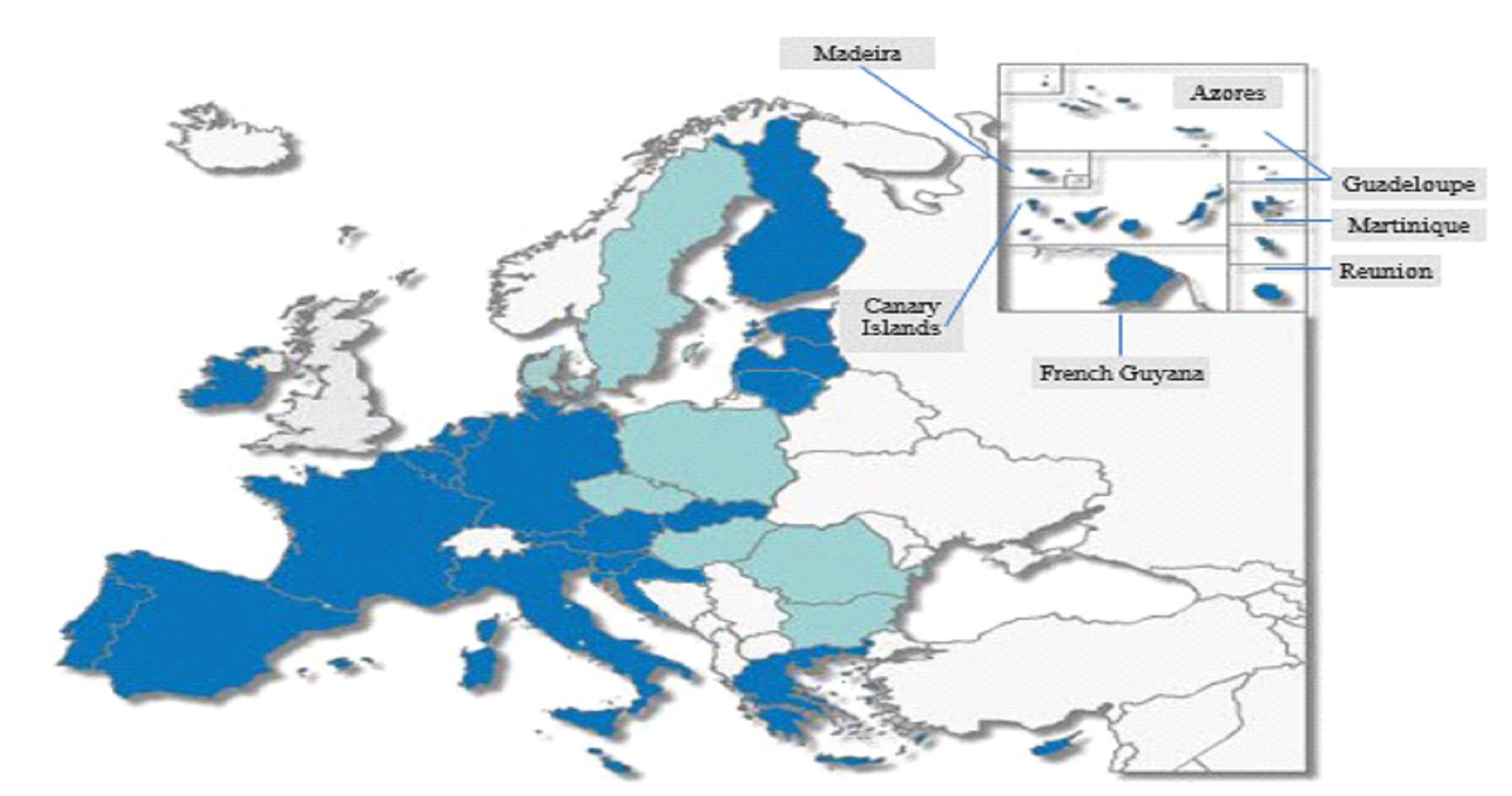

The following is a map of the European Union and the countries, including Italy, within the Euro area.

The following is a map of Italy.

Population. According to ISTAT data, as of December 31, 2022, Italy’s resident population was estimated to be approximately 58.851 million, accounting for approximately 13.2 per cent of the total EU population, compared to approximately 59.030 million as of December 31, 2021. Italy is the third most populated country in the EU after Germany and France.

According to ISTAT data, as of December 31, 2022, the six regions in the southern part of the peninsula together with Sicily and Sardinia, known as the Mezzogiorno, had a population of approximately 19.8 million. As of the same date, northern and central Italy had a population of approximately 27.3 million and 11.7 million, respectively.

As of December 31, 2022, the breakdown of the resident population by age group was as follows:

| • | under 20 | 17.4 per cent |

| • | 20 to 39 | 21.2 per cent |

| • | 40 to 59 | 30.3 per cent |

| • | 60 and over | 31.1 per cent |

__________________________

Source: ISTAT.

Italy’s fertility rate is one of the lowest in the world, while life expectancy for Italians is among the highest in the world. The average age of the resident population is increasing, mainly due to demographic trends and resident population decreasing in recent years.

Rome, the capital of Italy and its largest city, is situated near the western coast approximately halfway down the peninsula, and had a population of approximately 2.75 million as of December 31,

2022. The next largest cities are Milan, with a population of approximately 1.35 million, Naples, with approximately 913 thousand inhabitants, and Turin, with approximately 842 thousand inhabitants. Based on ISTAT data, as of December 31, 2022, population density was approximately 194.8 persons per square kilometer.

According to ISTAT data, as of December 31, 2022, there were approximately 5.1 million foreigners holding permits to live in Italy, a 2.8 per cent decrease from December 31, 2021. Immigration legislation has been the subject of intense political debate since the early 1990s. Since 2002, Italy has tightened its immigration laws through Law No. 189 of July 30, 2002 (Legge Bossi-Fini), and initiated bilateral agreements with several countries for cooperation in identifying illegal immigrants. In addition to measures aimed at controlling illegal immigration, the Government has also introduced measures aimed at regularizing the position of illegal immigrants, such as Legislative Decree No. 109 of July 16, 2012 and Law Decree No. 76 of June 28, 2013 (converted into Law No. 99 of August 9, 2013), Law Decree No. 130 of October 21, 2020 (converted into Law No. 173 of December 18, 2020), and Law Decree No. 20 of March 10, 2023 (converted into Law No. 50 of May 5, 2023). While these legislative efforts have resulted in the regularization of large numbers of illegal immigrants, Italy continues to have a relatively large number of foreigners living in Italy illegally.

In 2022, approximately 105.1 thousand immigrants arrived illegally in Italy by sea, compared to approximately 67.5 thousand and 34.1 thousand arriving illegally by sea in 2021 and 2020, respectively. This is due in part to the increase in the number of immigrants from North Africa entering Europe through the Central and Western Mediterranean routes.

As of September 30, 2023, the Government hosted approximately 141.1 thousand migrants. The number of Asylum seekers has increased in 2022, with the number of applications increasing from approximately 67.5 thousand as of December 31, 2021 to approximately 105.1 thousand as of December 31, 2022.

Government and Political Parties

Italy was originally a loose-knit collection of city-states, most of which united into one kingdom in 1861. It has been a democratic republic since 1946. The Government operates under a Constitution, originally adopted in 1948, that provides for a division of powers among the legislative, executive and judicial branches.

The Legislative Branch. Parliament consists of a Chamber of Deputies, with 400 elected members, and a Senate, with 200 elected members and a small number of life tenure Senators, currently five, consisting of former Presidents of the Republic and prominent individuals appointed by the President. Except for life tenure senators, members of Parliament are elected for five years by direct universal adult suffrage, although elections have been held more frequently in the past because the instability of multi-party coalitions has led to premature dissolutions of Parliament. The Chamber of Deputies and the Senate rank equally and have substantially the same legislative power. Any statute must be approved by both the Chamber of Deputies and the Senate before being enacted.

The Executive Branch. The head of State is the President, elected for a seven-year term by an electoral college that includes the members of Parliament and 58 regional delegates. On January 29, 2022, Parliament elected Mr. Sergio Mattarella as President for a second term. The President nominates and Parliament confirms the Prime Minister, who is the effective head of government. The President has the power to dissolve Parliament. The Council of Ministers is appointed by the President on the Prime Minister’s advice. The Prime Minister and the Council of Ministers answer to the Chamber of Deputies and the Senate and must resign if Parliament passes a vote of no confidence in the administration. The

Constitution also grants the President the power to appoint one-third of the members of the Constitutional Court, call general elections and lead the army.

The Judicial Branch. Italy is a civil law jurisdiction. Judicial power is vested in ordinary courts, administrative courts and courts of accounts. The highest ordinary court is the Corte di Cassazione in Rome, where judgments of lower courts of local jurisdiction may be appealed. The highest of the administrative courts, which hear claims against the State and local entities, is the Consiglio di Stato in Rome. The Corte dei Conti in Rome supervises the preparation of, and adjudicates, the State budget of Italy.

There is also a Constitutional Court (Corte Costituzionale) that does not exercise general judicial powers but adjudicates conflicts among the other branches of government and determines the constitutionality of statutes. Each of the President, the Parliament (in joint session) and representatives of the highest civil and administrative courts appoint five members of the Constitutional Court, for a total of 15 members.

Criminal matters are within the jurisdiction of the criminal law divisions of ordinary courts, which consist of magistrates who either act as judges in criminal trials or are responsible for investigating and prosecuting criminal cases.

Political Parties. The main political parties are: (i) Fratelli d’Italia, a right-wing political party led by Ms. Giorgia Meloni, (ii) Partito Democratico, a center-left political party led by Ms. Elly Schlein, (iii) Lega, a right-wing political party led by Mr. Matteo Salvini, (iv) Movimento 5 Stelle, a non-aligned political party led by Mr. Giuseppe Conte, and (v) Forza Italia, a center‑right political party led by Mr. Antonio Tajani.

The general Parliamentary elections held on September 25, 2022 resulted in the right-wing coalition, led by Fratelli d’Italia and including Lega and Forza Italia, winning a majority in both the Chamber of Deputies and the Senate. On October 21, 2022, President Mr. Sergio Mattarella invited Ms. Giorgia Meloni to form a new Government and, on October 22, 2022, Ms. Giorgia Meloni was sworn in as Italy’s Prime Minister. The coalition Government led by Ms. Giorgia Meloni is supported by the following major political parties: (i) Fratelli d’Italia, (ii) Lega, and (iii) Forza Italia.

Elections. Except for a brief period, since Italy became a democratic republic in 1946 no single party has been able to command an overall majority in Parliament, and, as a result, Italy has a long history of coalition governments.

On October 26, 2017, Parliament adopted Law No. 165, the new electoral law (so-called Rosatellum) that became effective on November 12, 2017 (the “2017 Electoral Law”). The 2017 Electoral Law provides for a mixed system of proportional and majority method with 37.5 per cent of seats awarded using a first past the post electoral system and 62.5 per cent of seats awarded using a proportional method, with one round of voting. As a result of the adoption of the 2017 Electoral Law, the 400 seats in the Chamber of Deputies are awarded as follows: (i) 147 seats are awarded through a first past the post vote in an equivalent number of single-member districts, (ii) 245 seats are awarded by vote based on regional proportional representation, and (iii) eight seats are awarded by vote of Italians abroad. Excluding the life tenure Senators (currently six), that includes senators appointed at the discretion of the President, and former presidents of Italy, the 200 seats in the Senate are awarded as follows: (i) 74 seats are awarded through a first past the post vote in an equivalent number of single-member districts, (ii) 122 seats are awarded by vote based on regional proportional representation, and (iii) four seats are awarded by vote of Italians abroad. Both the Senate and the Chamber of Deputies are elected on a single ballot. Parties are not eligible for any seats unless they obtain at least 3.0 per cent of the total votes, while the

minimum threshold for party coalitions is 10.0 per cent (on the assumption that at least one party in the coalition obtain at least 3.0 per cent of the total votes).

Regional and Local Governments. Italy is divided into 20 regions made up of 14 metropolitan areas, 80 provinces and 6 municipal consortia. The Italian Constitution reserves certain functions, including police services, education, and other local services, for the regional and local governments. Following a Constitutional reform passed by Parliament in 2001, additional legislative and executive powers were transferred to the regions. Legislative competence that historically had belonged exclusively to Parliament was transferred in certain areas (including foreign trade, health and safety, ports and airports, transport network and energy production and distribution) to a regime of shared responsibility whereby the national government promulgates legislation defining fundamental principles and the regions promulgate implementing legislation. Furthermore, as to all areas that are neither subject to exclusive competence of Parliament nor in a regime of shared responsibility between Parliament and the regions, exclusive regional competence is conferred to a region upon its request, subject to Parliamentary approval. In July 2009, Italy adopted legislation designed to increase the fiscal autonomy of regional and local governments. Under the new system, lower levels of government are able to levy their own taxes and will have a share in central tax revenues, including income tax and value added tax. In addition, a “standard cost” for public services such as health, education, welfare and public transport has been determined to set budgets for local governments.

The Italian Constitution grants special status to five regions (Sicily, Sardinia, Trentino-Alto Adige, Friuli-Venezia Giulia and Valle d’Aosta) providing them with additional legislative and executive powers.

Referenda. An important feature of Italy’s Constitution is the right to hold a referendum to abrogate laws passed by Parliament. Upon approval, a referendum has the legal effect of annulling legislation to which it relates. Referenda cannot be held on matters relating to taxation, the State budget, the ratification of international treaties or judicial amnesties. A referendum can be held at the request of 500,000 signatories or five regional councils. In order for a referendum to be approved, a majority of the Italian voting population must vote in the referendum and a majority of such voters must vote in favor of the referendum.

Constitutional reforms can be approved by two thirds of the members of each of the Chamber of Deputies and the Senate. If a constitutional reform fails to be approved by this super majority, the relevant reform may be submitted to a popular referendum at the request of one-fifth of the members of either the Chamber of Deputies or the Senate, 500,000 petitioners or five regional councils. Unlike any other referendum, referenda called to amend the Constitution do not require a quorum of the majority of the Italian voting population to vote in such referenda.

The European Union

Italy is a founding member of the European Economic Community, which now forms part of the European Union. Italy is one of the 27 current members of the EU together with Austria, Belgium, Bulgaria, Croatia, Cyprus, the Czech Republic, Denmark, Estonia, Finland, France, Germany, Greece, Hungary, Ireland, Latvia, Lithuania, Luxembourg, Malta, The Netherlands, Poland, Portugal, Romania, Slovakia, Slovenia, Spain and Sweden. The United Kingdom left the European Union on February 1, 2020.

The European Union is currently negotiating the terms and conditions of accession to the EU of the following candidate countries: Albania, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Moldavia, Montenegro, North Macedonia, Serbia, Turkey, and Ukraine. Potential candidates are Kosovo and Georgia.

EU Member States have agreed to delegate sovereignty for certain matters to independent institutions that represent the interests of the union as a whole, its Member States and its citizens. Set forth below is a summary description of the main EU institutions and their role in the European Union.

The Council of the EU. The Council of the EU, or the Council, is the EU’s main decision-making body. It meets in different compositions by bringing together on a regular basis ministers of the Member States to decide on matters such as foreign affairs, finance, education and telecommunications. When the Council meets to address economic and financial affairs, it is referred to as ECOFIN. The presidency of the Council rotates amongst Member States every six months according to a pre-set order. Portugal and Slovenia were in charge of the presidency of the Council from January 2021 to June 2021 and from July 2021 to December 2021, respectively. France and Czech Republic were in charge of the presidency of the Council from January 2022 to June 2022 and from July 2022 to December 2022, respectively. Spain is currently in charge of the presidency of the Council, while Sweden was in charge during the first half of the year.

The Council mainly exercises, together with the European Parliament, the European Union’s legislative function and promulgates:

| • | regulations, which are EU laws directly applicable in Member States; |

| • | directives, which set forth guidelines that Member States are required to enact by promulgating national laws; and |

| • | decisions, through which the Council implements EU policies. |

The Council also coordinates the broad economic policies of the Member States and concludes, on behalf of the EU, international agreements with one or more Member States or international organizations. In addition, the Council:

| • | shares budgetary authority with the European Parliament; |

| • | makes the decisions necessary for framing and implementing a common foreign and security policy; and |

| • | coordinates the activities of Member States and adopts measures in the field of police and judicial cooperation in criminal matters. |

Generally, decisions of the Council are made by qualified majority vote on a proposal by the Commission or the High Representative of the Union for Foreign Affairs and Security Policy. Starting from November 1, 2014, pursuant to changes enacted by the Treaty of Lisbon, qualified majority is achieved if:

| • | 55 per cent of Member States vote in favor (72 per cent in case the proposal is not coming from the Commission or from the High Representative); and |

| • | the proposal is supported by Member States representing at least 65 per cent of the total EU population. |

A minority of at least four Council members representing 35 per cent of the population may block a qualified majority vote.

The European Parliament. The European Parliament is elected every five years by direct universal suffrage. The European Parliament has three essential functions:

| • | it shares with the Council the power to adopt directives, regulations and decisions; |

| • | it shares budgetary authority with the Council and can therefore influence EU spending; and |

| • | it approves the nomination of EU Commissioners, has the right to censure the EU Commission and exercises political supervision over all the EU institutions. |

The latest EU election was held between May 23, 2019, and May 26, 2019, and Member State were allocated 751 (the maximum allowed under the EU treaties) seats in the European Parliament. Following the United Kingdom’s withdrawal from the EU on January 31, 2020, the 73 seats previously allocated to the United Kingdom were reallocated, with 27 seats being redistributed to other countries and the remaining 46 being kept in reserve for potential future enlargements. This reallocation resulted in each Member State being allocated the following number of seats in the European Parliament starting from February 1, 2020:

| Austria | 19 | | Latvia | 8 |

| Belgium | 21 | | Lithuania | 11 |

| Bulgaria | 17 | | Luxembourg | 6 |

| Cyprus | 6 | | Malta | 6 |

| Croatia | 12 | | Netherlands | 29 |

| Czech Republic | 21 | | Poland | 52 |

| Denmark | 14 | | Portugal | 21 |

| Estonia | 7 | | Romania | 33 |

| Finland | 14 | | Slovakia | 14 |

| France | 79 | | Slovenia | 8 |

| Germany | 96 | | Spain | 59 |

| Greece | 21 | | Sweden | 21 |

| Hungary | 21 | | | |

| Ireland | 13 | | | |

| Italy | 76 | | Total | 705 |

The five largest political groups in the European Parliament as a result of the United Kingdom’s withdrawal from the EU are:

| • | the European People’s Party (Christian Democrats), which comprises politicians of Christian democratic, conservative and liberal-conservative orientation, cumulatively representing approximately 25 per cent of the total seats; |

| • | the Progressive Alliance of Socialists and Democrats in the European Parliament, which is the political group of the Party of European Socialists, cumulatively representing approximately 20 per cent of the total seats; |

| • | the Renew Europe, which comprises politicians of liberal-centrist orientation, cumulatively representing approximately 14 per cent of the total seats; |

| • | the Greens/European Free Alliance, which comprises primarily green and regionalist politicians, cumulatively representing approximately 10 per cent of the total seats; and |

| • | the European Conservatives and Reformists, a soft Eurosceptic, anti-federalist political group, cumulatively representing approximately 9 per cent of the total seats. |

In the European Parliamentary elections held in Italy on May 26, 2019, Lega, which is part of the Identity and Democracy coalition, won approximately 34 per cent of the votes increasing significantly the votes won in the 2018 Italian Parliamentary elections. Partito Democratico, which is part of the Progressive Alliance of Socialists and Democrats coalition, remained the second largest party with approximately 23 per cent of the votes. Movimento 5 Stelle, which had come first in the 2018 Italian Parliamentary elections, fell to third place with approximately 17 per cent of the votes.

The European Commission. The European Commission traditionally upholds the interests of the EU as a whole and has the right to initiate draft legislation by presenting legislative proposals to the European Parliament and Council. Currently, the European Commission consists of 27 members, one appointed by each Member State for five-year terms.

Court of Justice. The Court of Justice ensures that Community law is uniformly interpreted and effectively applied. It has jurisdiction in disputes involving Member States, EU institutions, businesses and individuals. A Court of First Instance has been attached to it since 1989.

Other Institutions. Other institutions that play a significant role in the European Union are:

| • | the European Central Bank (the “ECB”), which is responsible for defining and implementing a single monetary policy in the euro area; |

| • | the Court of Auditors, which checks that all the European Union’s revenues has been received and that all its expenditures have been incurred in a lawful and regular manner and oversees the financial management of the EU budget; and |

| • | the European Investment Bank, which is the European Union’s financial institution, supporting EU objectives by providing long-term finance for specific capital projects. |

Membership of International Organizations

Italy is a member of the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO), as well as many other regional and international organizations, including the United Nations and many of its affiliated agencies. Italy is one of the Group of Seven (G-7) industrialized nations, together with the United States, Japan, Germany, France, the United Kingdom and Canada, and a member of the Group of Twenty (G-20), which brings together the world’s major advanced and emerging economies, comprising the European Union and 19 country members. Italy is also a member of the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), the World Trade Organization (WTO), the IMF, the International Bank for Reconstruction and Development (World Bank), the European Bank for Reconstruction and Development (EBRD) and other regional development banks.

THE ITALIAN ECONOMY

General

According to IMF data, the Italian economy, as measured by 2022 GDP (at current prices in U.S. dollars), is the tenth largest in the world after the United States, the People’s Republic of China, Japan, Germany, India, the United Kingdom, France, the Russian Federation and Canada.

The table below shows the annual percentage change in real GDP growth for Italy and the countries participating in the EU and in the euro area, including Italy, for the period from 2018 through 2022.

Annual Per Cent Change in Real GDP (2018-2022)

| | 2018 | 2019 | 2020 | 2021 | 2022 |

| Italy | 0.9 | 0.5 | (9.0) | 8.3 | 3.7 |

EU(1) | 2.1 | 1.8 | (5.6) | 6.0 | 3.4 |

Euro area(2) | 1.8 | 1.6 | (6.1) | 5.9 | 3.4 |

__________________________

| (1) | The EU represents the 27 countries participating in the European Union. |

| (2) | The euro area represents the 20 countries participating in the European Monetary Union. |

Source: Bank of Italy and Eurostat.

In 2018, Italy’s GDP increased by 0.9 per cent compared to 2017, at a slower pace than expected and experiencing a stop in the last few months of the year. This was mainly due to both the slowdown in foreign sales and the weakening of national demand, which in the second half of the year affected investments (especially in capital goods) and, to a lesser extent, household spending.

In 2019, Italy’s GDP increased by 0.5 per cent compared to 2018, evidencing a further slow-down in the growth of Italian economy. This was mainly due to lower investments than in 2018 as a result of an increased uncertainty in the global economy, and a slowdown in disposable income.

In 2020, Italy’s GDP decreased by 9.0 per cent compared to 2019, mainly as a result of the contraction of global activities, exports and tourist inflows, as well as the reduction in internal mobility and consumption, due to the containment measures adopted in Italy and worldwide to face the Coronavirus pandemic. Uncertainty around the pandemic and its effects also caused a decline in business investments. For additional information regarding the key measures adopted by Italy in connection with the Coronavirus pandemic, see “The Italian Economy—Key Measures related to the Italian Economy.”

In 2021, Italy’s GDP increased by 8.3 per cent compared to 2020, mainly as a result of the measures in support of the economy adopted in connection with the Coronavirus pandemic and the lifting of the Coronavirus restrictions that facilitated the recovery of the services sector, in particular tourism. Consumer spending, fostered by improved labor market conditions and less uncertainty related to the Coronavirus pandemic than in 2020, supported the growth of the economy, with the household savings rate gradually returning to pre-pandemic levels.

In 2022, Italy’s GDP increased by 3.7 per cent compared to 2021, mainly driven by the easement of the restrictive measures originally adopted to prevent the spread of the Coronavirus pandemic, and generally benefitting from a higher inflation rate than in 2021. Furthermore, the increase in GDP was

driven by the tourism and construction sectors, which benefitted from certain tax incentives granted for refurbishment activities aimed at improving the energy rating of buildings.

In the past, the Government has historically experienced substantial government deficits. Among other factors, this has been largely attributable to high levels of social spending and the fact that social services and other non-market activities of the central and local governments accounted for a relatively significant percentage of total employment as well as high interest expense resulting from the size of Italy’s public debt. Countries participating in the European Economic and Monetary Union are required to reduce “excessive deficits” and adopt budgetary balance as a medium-term objective. For additional information on the budget and financial planning process, see “Public Finance—Measures of Fiscal Balance,” “Public Finance—Revenues and Expenditures” and, “Public Debt—Summary of External Debt—Excessive Deficit Procedure.”

A longstanding objective of the Government has been to control Italy’s debt-to-GDP ratio. Mainly as a result of the increase in GDP, Italy’s debt-to-GDP ratio in 2022 decreased to 138.8 per cent net of euro area financial support and 141.7 per cent gross of euro area financial support, while the primary deficit amounted to 1.9 per cent. Excluding the financial support provided to European Monetary Union (“EMU”) countries, the decrease from 2021 was of 5.1 percentage points.

On September 23, 2019, the Bank of Italy announced that Italy’s debt-to-GDP ratio had been revised upwards for the previous years, due to a change in the methodology employed to calculate public debt at a European level, as set out in the Manual on Government Deficit and Debt published by Eurostat on August 2, 2019 (“Eurostat Manual”). The methodology change affected how interest on certain non-negotiable notes is accounted for. In Italy, this has mainly affected the accounting treatment of postal savings (Buoni Postali Fruttiferi) (“BPF”) issued up to 2001. BPFs are bearer instruments payable on demand, on or prior to their maturity date; accrued interest on BPFs is paid on redemption, at the same time as the principal amount. The Eurostat Manual requires that accrued interest on BPFs be taken into account when calculating their face value, rather than just when BPFs are redeemed. As of December 31, 2022, the outstanding BPFs had an aggregate principal amount and accrued interest of €7.3 billion and €42.7 billion, respectively.

Specific accounts were created by the Treasury in 2003 in order to fund BPF redemptions. As of December 31, 2022, approximately €41.6 billion had been set aside on these accounts.

According to Italy’s most recent estimates, Italy’s debt-to-GDP ratio, gross of euro area financial support, is expected to reach 140.2 per cent in 2023, 140.1 per cent in 2024, 139.9 per cent in 2025, and 139.6 per cent in 2026, respectively.

Historically, Italy has had a high savings rate, calculated as a percentage of gross national disposable income, which measures aggregate income of a country’s citizens after providing for capital consumption (the replacement value of capital used up in the process of production). Private sector savings as a percentage of gross national disposable income averaged 19.5 per cent in the period from 2001 to 2010 and 19.4 per cent in the period from 2011 to 2020. Private sector savings as a percentage of gross national disposable income were 24.9 per cent in 2021 and 22.0 per cent in 2022, respectively. Because of the historically high savings rate, the Government has been able to raise large amounts of funds through issuances of Treasury securities in the domestic market, with limited recourse to external financing. As of June 30, 2023, non-resident holders owned 26.9 per cent of the total outstanding government debt, while the Bank of Italy and resident holders owned 25.4 per cent and 47.7 per cent of the total outstanding government debt, respectively.

The Italian economy is characterized by significant regional disparities, with the level of economic development of Southern Italy usually below that of Northern and Central Italy. In 2022, the per capita GDP in Southern Italy, also known as the Mezzogiorno, increased by 3.5 per cent. GDP increased by 3.1 per cent in the North West and by 4.2 per cent in the North East of Italy, respectively, while GDP in the Centre of Italy increased by 4.1 per cent. The marked regional divide in Italy is also evidenced by significantly higher unemployment in the Mezzogiorno. For additional information on Italian employment, see “—Employment and Labor.”

Key Measures related to the Italian Economy

In the last decade, the Government adopted a series of measures aimed at increasing Government receipts, reducing Government spending, fighting tax evasion, reforming the Italian banking system, simplifying the public administration, sustaining the economic and financial growth of Italy, introducing a basic universal income, reviving public investment, achieving the financing targets adopted by the EU and balancing the general government’s budget.

Measures adopted in 2020

In 2020, the Government adopted several measures to counter the effects of the Coronavirus pandemic and support families and businesses, including:

| • | Law Decree No. 18 of March 17, 2020, converted into Law No. 27 of April 24, 2020, the so-called Decreto Cura Italia (the “Cure Italy Decree”), which provided for €25.0 billion of support measures to counter the Coronavirus pandemic. Measures introduced by the Cure Italy Decree included a suspension of tax payments and related obligations, tax breaks for certain businesses, a moratorium on certain civil and criminal proceedings, financial support to businesses and self-employed workers in sectors that had been particularly affected by the restrictions imposed by the Government during the Coronavirus pandemic, a suspension of employee dismissals, financial support measures for SMEs including state guarantees for certain loans, as well as additional funding for public services, the healthcare system and medical workers’ salaries. For more information on state guarantees provided pursuant to the Cure Italy Decree, see “Public Debt—General—SACE Guarantees”. |

| • | Law Decree No. 23 of April 8, 2020, converted into Law No. 40 of June 5, 2020, the so-called Decreto Liquidità (the “Liquidity Decree”), aimed at generating further cashflow for businesses, delaying payment terms for certain taxes and other dues, and protecting businesses in strategic industries from takeovers. The measures introduced by the Liquidity Decree included a broader application of the so-called Golden Power, pursuant to which Italy may prohibit or impose conditions on the acquisition of strategic businesses by non-Italian acquirers. |

| • | Law Decree No. 34 of May 19, 2020, converted into Law No. 77 of July 17, 2020, the so-called Decreto Rilancio (the “Restart Decree”), introducing measures to counter the economic effects of the Coronavirus pandemic and to support households, businesses and self-employed workers. The measures included a fund for education, financial support to self-employed workers, working families with children and low-income households, financial support to businesses in the hospitality sector, financial support for workers made redundant, reduced utilities and tax credits for rent and sanitising costs for SMEs, financial support to the healthcare system to hire additional nursing staff and expand intensive care units. |

| • | Law Decree No. 104 of August 14, 2020, converted into Law No. 126 of October 13, 2020, amending and supplementing measures previously introduced by the Cure Italy Decree and the |

Restart Decree. Law Decree No. 104 provided for additional €25.0 billion in support of the economic recovery against the adverse effects of the Coronavirus pandemic, bringing the total amount of funds committed by the Government to counter the effects of the Coronavirus pandemic to approximately €100.0 billion (approximately 6.0 per cent of Italian GDP).

In addition to the measures adopted in connection with the Coronavirus pandemic, other measures adopted by the Government in 2020 included the Decrees of the Ministry of Education No. 24 of June 5, 2020, No. 28 of June 9, 2020, and No. 72 of July 25, 2020, granting financial support to local authorities for the development and implementation of school expansion plans in certain areas of Central Italy affected by earthquakes in 2016 and 2017.

On December 30, 2020, Parliament approved the stability law for 2021 and the budget law for 2021-2023 through Law No. 178 of December 30, 2020 (the “2021 Budget”). The 2021 Budget allocated funds to the healthcare sector for hiring medical personnel and healthcare workers, and included measures aimed at stimulating the job market, such as offering certain tax incentives for hiring young people (up to 35 years of age) and women (with no age limits). Furthermore, €5.0 billion had been allocated to fund certain tax exemptions granted to private employers hiring employees in the South of Italy, and a new social safety net, the Extraordinary Indemnity for Income and Operational Continuity (ISCRO), had been introduced granting protection to those registered for VAT within a separate contribution regime (partite Iva in gestione separata).

Measures adopted in 2021

In 2021, the Government adopted additional measures to counter the effects of the Coronavirus pandemic and support families and businesses, and measures aimed at protecting national strategic interests and regulating employees’ dismissals, including:

| • | Law Decree No. 41 of March 22, 2021, converted into Law No. 69 of May 21, 2021, the so-called Decreto Sostegni, providing for financial measures totaling €32.0 billion aimed at supporting the service sector. The measures included new grants for businesses which suffered a decline in turnover, further extensions and suspensions of tax payment terms, extension of financial support for furloughs, a suspension of employee dismissals, financial support to the unemployed and additional funding for vaccines and drugs. |

| • | Law Decree No. 73 of May 25, 2021, converted into Law No. 106 of July 23, 2021, allocating approximately €40.0 billion to containing the social and economic impact of the Coronavirus-related restrictions. The main areas of action included, inter alia: support for businesses; access to credit and business liquidity; support for the health sector; work and social policies; support to local authorities. |

On December 30, 2021, Parliament approved the stability law for 2022 and the budget law for 2022-2024 through Law No. 234 of December 30, 2021 (the “2022 Budget”). The 2022 Budget defined new medium and long-term interventions that aimed to strengthen the actions undertaken under the National Recovery and Resilience Plan (Piano Nazionale di Ripresa e Resilienza) and reformed the income tax for individuals, redesigning rates and deductions. For additional information on the National Recovery and Resilience Plan, see “Financial Assistance to EU Member States—The National Recovery and Resilience Plan”.

Measures adopted in 2022

In 2022, the Government adopted several measures to counter the negative effects of the Coronavirus pandemic and the war in Ukraine on the Italian economy and the increase in energy prices, including:

| • | Law Decree No. 4 of January 27, 2022, converted into Law No. 25 of March 28, 2022, allocated approximately €20.0 million to supporting the economic activities affected, directly or indirectly, by Coronavirus-related restrictions. Further, by adopting Law Decree No. 4, the Government established a special fund of €200.0 million to boost the economic recovery through non-repayable grants to certain sectors of the economy. |

| • | Law Decree No. 17 of March 1, 2022, converted into Law No. 34 of April 27, 2022, provided for urgent measures to contain the effects of price increases in electricity and natural gas and increase the national production of renewable energy and energy savings, including (i) the exemption, for the second quarter of 2022, from the payment of general system charges for domestic users and non-domestic low voltage users, and (ii) a new regulation incentivizing the development of solar energy. Further, Law Decree No. 17: (i) reduced the VAT rate for gas and methane for civic and industrial uses; and (ii) granted an extraordinary contribution in the form of a tax credit ranging from 15 to 20 per cent of the incurred energy costs to companies with a high consumption of electricity and natural gas. |

| • | Law Decree No. 21 of March 21, 2022, converted into Law No. 51 of May 20, 2022, (i) introduced a cap on the excise duties payable on petrol and diesel fuel; (ii) provided for utilities bills’ installment plans and additional tax credits for companies; and (iii) lowered the family income threshold necessary to access certain energy bonuses. |

| • | Law Decree No. 115 of August 9, 2022, converted into Law No. 142 of September 21, 2022, inter alia: (i) mandated energy suppliers and operators to provide gas to certain categories of private consumers at a price that reflects the actual cost in the wholesale market; and (ii) prevented electricity and natural gas suppliers from amending contracts for the supply of energy to domestic users until April 30, 2023. |

| • | Law Decree No. 144 of September 23, 2022, converted into Law No. 175 of November 17, 2022, provided additional measures to contain the effects of the sharp increase in the cost of energy, including: (i) extending contributions to businesses and individuals for energy costs; and (ii) establishing certain allowances for the benefit of employees and self-employed workers. |

| • | Law Decree No. 176 of November 18, 2022, converted into Law No. 6 of January 13, 2023 provided for, inter alia, (i) extensions until December 31, 2022 of State contributions to businesses for energy costs and a cap on excise taxes on petrol and diesel fuel; and (ii) extension until March 31, 2023 of installment plans for payment of energy utilities in favor of certain businesses. |

On December 29, 2022, Parliament approved the stability law for 2023 and the budget law for 2023-2025 through Law No. 197 of December 29, 2022 (the “2023 Budget”). The 2023 Budget allocated approximately €35.0 billion to measures aimed at containing the increase in the cost of energy, and to support families, workers and businesses. Key measures of the 2023 Budget included, inter alia: (i) an increase in the income threshold required for families to access certain State funded energy grants; (ii) tax credits for SMEs and businesses with high energy consumption rates; (iii) a new pension system (Quota 103), allowing workers with at least 62 years of age and 41 years of social contribution to the national

pension fund to apply for retirement; (iv) an increase in the minimum pension amount for retirees over the age of 75 to €600; (v) a 15% flat-tax regime for certain self-employed workers; and (vi) an increase in the threshold for cash payments from €1,000 to €5,000 with effect from January 1, 2023.

Measures adopted in 2023

In 2023, the Government adopted measures to counter the general increase in energy prices, support areas affected by floods affecting the region of Emilia Romagna in May 2023, and sustain national strategic interests, including:

| • | Law Decree No. 34 of March 30, 2023, converted into Law No. 56 of May 26, 2023, providing for, inter alia, (i) the extension until June 30, 2023 of a reduced VAT rate on gas and methane products for civilian and industrial uses; (ii) reduced energy bills for low-income families; (iii) tax credits for businesses which in the first quarter of 2023 recorded an increase in the price of electricity and gas bills of more than 30 per cent compared to the first quarter of 2019; and (iv) a more favorable tax regime for farming entrepreneurs producing and selling photovoltaic energy. Furthermore, Law Decree No. 34 of March 30, 2023 established a special fund for national healthcare purposes in the amount of €1.0 billion to be allocated among the Italian regions. |

| • | Law Decree No. 61 of June 1, 2023, converted into Law No. 100 of July 31, 2023, establishing a special fund in the amount of €2.0 billion as aid package for families and businesses affected by deadly floods in Emilia-Romagna in May 2023. |

| • | Law Decree No. 131 of September 29, 2023 (not yet converted into law) providing for, inter alia, (i) a further reduction of energy bills for low-income households; (ii) a reduced VAT rate of 5% for the supply of methane gas for industrial use and for household heating purposes; and (iii) a €7.5 million fund established to support university scholarships. |

Furthermore, through Law No. 111 of August 9, 2023 (the “Law 111/2023”), Parliament approved a set of general principles and criteria enabling the Government to implement a full reform of the Italian tax system (legge delega).

Financial Assistance to EU Member States

The EFSF. In June 2010, the EU Member States created the European Financial Stability Facility (the “EFSF”) whose objective is to preserve financial stability of Europe’s monetary union by providing temporary assistance to euro area Member States. In order to fund any such assistance, the EFSF has the ability to issue bonds or other debt instruments in the financial markets. Such debt is guaranteed by the Member States on a several basis based on each Member State’s participation in the ECB’s share capital. Initially, the limit to these guarantees (and therefore of the facility itself) was capped at €440.0 billion. Italy’s share of the EFSF is approximately 19.0 per cent. Financing granted by the EFSF increases the public debt of the participating countries proportionally to the share of the EFSF.

The EFSF financing is combined with the financing granted under the European Financial Stabilization Mechanism (the “EFSM”), a €60.0 billion facility organized by the European Commission, and additional financings from the IMF. The EFSM allows the European Commission to borrow in financial markets on behalf of the Union and then lend the proceeds to the beneficiary Member State. All interest and loan principal are repaid by the beneficiary Member State via the European Commission. The EU budget guarantees the repayment of the bonds in case of default by the borrower. The EFSF, EFSM and IMF can only act after a request for support is made by a euro area Member State and a country program has been negotiated with the European Commission and the IMF. As a result, any

financial assistance by the EFSF, EFSM and IMF to a country in need is linked to strict policy conditions. The EFSF and EFSM could only grant new financings until June 2013; after this date, only existing financings could be administered.

A set of measures designed to expand the EFSF’s role were approved during the course of 2011: (i) the cap to guarantees provided by the euro area countries was increased from €440.0 billion to €780.0 billion; (ii) the facility was authorized to make purchases of Member States’ government bonds in the primary and secondary markets; (iii) it was authorized to take action under precautionary programs and to finance the recapitalization of financial institutions; and (iv) it was allowed to use the leverage options offered by granting partial risk protection on new government bond issues by euro area countries and/or by setting up one or more vehicles to raise funds from investors and financial institutions.

The ESM. From July 2013, the European Stability Mechanism (“ESM”), a facility with a maximum lending capacity of €500.0 billion, has assumed the role of the EFSF and the EFSM. The ESM has a subscribed capital of €700.0 billion, of which €80 billion is in the form of paid-in capital provided by the euro area Member States and €620.0 billion as committed callable capital and guarantees from euro area Member States, who have committed to maintain a minimum 15.0 per cent ratio of paid-in capital to outstanding amount of ESM issuances in the transitional phase from 2013 to 2017. Italy’s maximum commitment to the ESM is approximately €125.3 billion. The ESM will grant financings to requesting countries in the euro area under strict conditions and following a debt sustainability analysis.

On February 2, 2012, several revisions were made to the treaty instituting the ESM. Its entry into force was brought forward by one year, to July 2012, and the voting rules were amended to allow decisions to be taken by a qualified majority of 85 per cent in certain circumstances. This majority rule can be invoked in place of the requirement of unanimous decisions if the European Commission and the ECB determine that financial assistance measures need to be taken urgently and in the interests of the euro area’s financial and economic stability. Furthermore, as in the case of the EFSF, the ESM has additional means available to it to support countries in difficulty: it can purchase member countries’ government bonds, both directly or on the secondary market, and is allowed greater flexibility in its direct purchases of government bonds; it can act under precautionary programs; and it can finance the recapitalization of financial institutions. Finally, to strengthen investors’ confidence in the new arrangements, on March 30, 2012, the EU announced that the ESM’s endowment capital would be paid up by 2014 instead of 2017 as originally planned. It was also agreed that as of July 2012 the ESM has become the main instrument for financing new support packages. The EFSF will continue to operate until existing financing arrangements terminate. Total ESM/EFSF loans (in net disbursed terms) amounted to €295.0 billion as of September 2023. The ESM’s remaining lending capacity as of September 2023 is of approximately €417.4 billion (82 per cent).

The EU Solidarity Fund. The EU Solidarity Fund was set up in 2002 to respond to major natural disasters within Europe. The fund was created as a reaction to the severe floods in Central Europe in the summer of 2002. Since then, it has been used for 127 natural disasters in 24 Member States (plus the U.K.) and 3 accession countries (Albania, Montenegro, and Serbia) covering a range of different catastrophic events including floods, forest fires, earthquakes, storms and drought. The fund can provide financial aid if total direct damage caused by a disaster exceeds €3.0 billion (at 2011 prices) or 0.6 per cent of an EU country’s gross national income (GNI), whichever is lower, or for more limited regional disasters, the eligibility threshold is 1.5 per cent of the region’s gross domestic product (GDP), or 1.0 per cent for an outermost region. On September 11, 2020, the European Commission announced that it had granted €211.7 million from the EU Solidarity Fund to Italy, following the extreme weather damages in late October and November 2019. The grant will finance retroactively the restoration of vital infrastructures, measures to prevent further damage and to protect cultural heritage, as well as cleaning operations in the affected areas. In response to the Coronavirus pandemic, the scope of the EU Solidarity

Fund has been extended to encompass major public health emergencies. Since 2002 Italy has received more than €3.0 billion from the EU Solidarity Fund.

Quantitative Easing. On January 22, 2015, the ECB announced an expanded asset purchase program (“Quantitative Easing”) comprising the ongoing purchase programs for asset-backed securities (ABSPP) and covered bonds (CBPP3), and, as a new element, purchases of certain euro-denominated securities issued by euro area central governments, agencies, and European institutions (PSPP). Combined monthly purchases were originally capped at €60.0 billion and were initially intended to be carried out until September 2016 or until the ECB sees a sustained adjustment in the path of inflation that is consistent with its aim of achieving inflation rates close to 2.0 per cent over the medium term. In early December 2015, the ECB announced the extension of Quantitative Easing until March 2017, maintaining combined monthly purchases at the level of €60.0 billion. On March 10, 2016, the ECB announced an increase to €80.0 billion in the monthly purchase under the Quantitative Easing program and four new targeted longer-term refinancing operations (TLTRO II) to reinforce its accommodative monetary policy stance and to foster new lending, which will be conducted from June 2016 to March 2017, on a quarterly basis. From December 2016 to January 2018, the ECB has extended the Quantitative Easing program twice, decreasing the combined monthly purchases from €60.0 billion to €30.0 billion. With respect to the PSPP, the percentage of securities issued in the euro area and purchased by the ECB was increased from 8.0 per cent in 2015 to 10.0 per cent in 2016, while the percentage of securities issued in the euro area and purchased by national central banks of a Member State different from the Member State where the relevant securities were issued was decreased from 12.0 per cent in 2015 to 10.0 per cent in 2016. The residual 80.0 per cent of PSPP securities issued in the euro area were purchased by the national central bank of the Member State where the relevant securities were issued. On December 13, 2018, the ECB announced that net purchases under Quantitative Easing would end in December 2018. At the same time, the ECB announced that it would continue reinvesting, in full, the principal payments from maturing securities purchased under the Quantitative Easing for an extended period of time past the date when it starts raising the key ECB interest rates, and in any case for as long as necessary to maintain favorable liquidity conditions and an ample degree of monetary accommodation. On September 12, 2019, the ECB announced that it would resume making net purchases under the Quantitative Easing program, beginning November 1, 2019, at a rate of €20.0 billion per month. The ECB expects this to run for as long as necessary to reinforce the accommodative impact of its policy rates, and to end shortly before it starts raising the key interest rates. In March 2020, as a consequence of the Coronavirus pandemic, the ECB implemented the Pandemic Emergency Purchase Program (PEPP), a temporary asset purchase program of private and public sector securities. The initial €750.0 billion appropriation for the PEPP has been increased by €600.0 billion on June 4, 2020, and by €500.0 billion on December 10, 2020, for a total of €1,850 billion. On December 16, 2021, the ECB decided to discontinue net asset purchases under the PEPP at the end of March 2022. The maturing principal payments from securities purchased under the PEPP will be reinvested until at least the end of 2024. As of September 2023, the PEPP holdings at amortized cost amounts to approximately €1.7 billion.

The National Recovery and Resilience Plan. The National Recovery and Resilience Plan (Piano Nazionale di Ripresa e Resilienza) (“NRRP”) is part of the Next Generation EU programme, namely the €750.0 billion package – about half of which is in the form of grants – that the European Union implemented in response to the pandemic crisis to support its Member States. The main component of the Next Generation EU programme is the Recovery and Resilience Facility (“RRF”), which has a duration of six years – from 2021 to 2026 – and a total size of €723 billion at 2022 prices (€338.0 billion in the form of grants, and the remaining €385.0 billion in the form of low-interest loans). The NRRP presented by Italy, endorsed by the EU Commission on June 22, 2021 and approved by the EU Council on July 13, 2021 (as amended on September 19, 2023), envisages investments and a reform package, with €191.5 billion in resources being allocated to Italy through the RRF (€68.9 billion in the form of grants and €122.6 billion in the form of loans) and €30.6 billion being funded through a

complementary fund established by Law Decree No. 59 of May 6, 2021 (converted into Law No. 101 of July 1, 2021). In addition, €26.0 billion has been earmarked for the implementation of specific works and for replenishing the resources of the development and cohesion fund by 2032 and €13.0 billion will be available pursuant to the REACT-EU programme under Next Generation EU. The NRRP has been developed around three strategic axes shared at a European level: (i) digitization and innovation; (ii) ecological transition; and (iii) social inclusion, and intends to achieve the following six missions:

| 1. | Digitization, Innovation, Competitiveness, Culture: promoting the country’s digital transformation, supporting innovation in the production system, and investing in two key sectors for Italy, namely tourism and culture. Under the NRRP, €49.8 billion has been allocated to this mission (of which €40.3 billion from the RRF, approximately €800 million from the REACT-EU programme and €8.7 billion from the complementary fund); |

| 2. | Green Revolution and Ecological Transition: improving the sustainability and resilience of the economic system and ensuring a fair and inclusive environmental transition. Under the NRRP, €69.9 billion has been allocated to this mission (of which €59.5 billion from the RRF, €1.3 billion from the REACT-EU programme and €9.2 billion from the complementary fund); |

| 3. | Infrastructure for Sustainable Mobility: promoting the development of a modern and sustainable transportation infrastructure throughout the country. Under the NRRP, €31.5 billion has been allocated to this mission (of which €25.4 billion from the RRF and €6.0 billion from the complementary fund); |

| 4. | Education and Research: promoting education, digitalization and technical-scientific skills, research and technology transfer. Under the NRRP, €33.8 billion has been allocated to this mission (of which €30.9 billion from the RRF, €1.9 billion from the REACT-EU programme and €1.0 billion from the complementary fund); |

| 5. | Inclusion and Cohesion: promoting labor market participation, including through training, strengthen active labor market policies and foster social inclusion. Under the NRRP, €29.9 billion has been allocated to this mission (of which €19.9 billion from the RRF, €7.2 billion from the REACT-EU programme and €2.8 billion from the complementary fund); and |

| 6. | Health: promoting local health services, to allow modernization and digitization of the health system and ensuring equal access to care. Under the NRRP, €20.2 billion has been allocated to this mission (of which €15.6 billion from the RRF, €1.7 billion from the REACT-EU programme and €2.9 billion from the complementary fund). |

The NRRP also includes a programme of reforms to facilitate the implementation phase and, more generally, to contribute to the modernization of the country and make the economic environment more favorable to the development of business activities:

| • | a Public Administration reform to provide better services, encourage the recruitment of young people, invest in human capital and increase the level of digitization; |

| • | a justice reform to reduce the length of legal proceedings, especially civil proceedings, and the heavy burden of backlogs; |

| • | simplification measures horizontal to the NRRP, e.g., in matters of permits and authorizations and public procurement, to ensure the implementation and maximum impact of investments; and |

| • | reforms to promote competition as an instrument of social cohesion and economic growth. |

The NRRP may be amended and supplemented from time to time, including through adjustments contained in the National Reform Programme. For additional information on the 2023 National Reform Programme, see “Public Finance—The 2023 Economic and Financial Document.”

The following table shows the estimated financial impact of the measures contained in the NRRP on GDP, consumption, investments, imports and exports, in each case for the period from 2021 to 2026.

| | 2021 | 2022 | 2023 | 2024 | 2025 | 2026 |

| GDP | 0.1 | 0.2 | 1.0 | 1.8 | 2.7 | 3.4 |

| Consumption | (0.3) | (0.6) | (0.8) | (0.6) | 0.0 | 1.0 |

| Investments | 1.2 | 3.3 | 8.0 | 11.0 | 13.0 | 12.4 |

| Imports | 0.0 | 0.2 | 0.9 | 1.8 | 2.8 | 3.7 |

| Exports | (0.1) | (0.4) | (0.6) | (0.3) | 0.6 | 1.8 |

__________________________

Source: Ministry of Economy and Finance.

As of September 30, 2023, Italy had received €66.9 billion under the NRRP.

On July 28, 2023, the EU Commission gave a positive preliminary assessment regarding Italy’s third payment request in the amount of €18.5 billion.

On November 28, 2023, the EU Commission has endorsed a positive preliminary assessment regarding Italy's fourth payment request in the amount of €16.5 billion in grants and loans under the RRF. The corresponding amount will be disbursed at the end of the assessment process. Additional disbursements to Italy may be authorized by the EU Commission subject to the satisfaction of certain milestones and targets outlined in the NRRP.

The Ministry of Economy and Finance periodically monitors progress in the implementation of reforms and investments and is the primary point of contact with the EU Commission. A steering committee has been also set up at the Presidency of the Italian Council of Ministers.

SURE Facility. On May 19, 2020, the EU approved Council Regulation 2020/672 (“SURE Regulation”) which sets forth the legal framework for providing financial assistance in an aggregate amount of up to €100.0 billion to Member States that have experienced a severe economic disturbance caused by the Coronavirus pandemic. Loans provided to Member States under the SURE instrument are underpinned by a system of voluntary guarantees from Member States. Each Member State’s contribution to the overall amount of the guarantee corresponds to its relative share in the total gross national income (GNI) of the European Union, based on the 2020 EU budget. On September 17, 2022, the EU approved to extend a loan to Italy pursuant to the SURE Regulation in an aggregate principal amount of up to €27.4 billion with a maximum average maturity of 15 years which Italy has fully drawn. The term for the Member States to obtain loans under the SURE Regulation expired on December 31, 2022.

Collective Action Clauses. Italy has introduced a form of collective action clause into the documentation of all of its New York law governed bonds issued since June 16, 2003.

The rights of bondholders have generally been individual rather than collective. As a result of each bondholder having individual rights, the restructuring or amending of a bond would legally have to be negotiated with each bondholder individually and any one bondholder that did not agree with restructuring

or amendment terms could refuse to accept such terms or “hold out” for better terms thereby delaying the restructuring or amendment process and potentially forcing an issuer into costly litigation. These risks increase as the bondholder base is more geographically dispersed or is comprised of both individual and institutional investors.

In an effort to minimize these risks, issuers began including so-called collective action clauses into their bond documentation. These collective action clauses are intended to minimize the risk that one or a few “hold out” bondholders delay a restructuring or amendment where a majority of the other bondholders favor the terms of the restructuring or amendment, by permitting a qualified majority of the bondholders to accept the terms and bind the entire bondholder base to such terms.

The treaty instituting the ESM, as revised on February 2, 2012 (and ratified by Italy through Law No. 116 of July 23, 2012), required that all new government debt securities with a maturity of more than one year, issued on or after January 1, 2013, include the same collective action clauses as other countries in the Eurozone (the “EU Collective Action Clauses”). These standardized clauses for all euro area Member States, as set out in the document “Common Terms of Reference” dated February 17, 2012, developed and agreed by the European Economic and Financial Committee (EFC) and published on the EU Commissions website, allow a qualified majority of creditors to agree on certain “reserved matter modifications” to the most important terms and conditions of the bonds of a single series (including the financial terms) that are binding for all the holders of the bonds of that series with either (i) the affirmative vote of the holders of at least 75 per cent represented at a meeting or (ii) a written resolution signed by or on behalf of holders of at least 66 2/3 per cent of the aggregate principal amount of the outstanding bonds of that series and the consent of the Issuer. The EU Collective Action Clauses also include an aggregation clause enabling a majority of bondholders across multiple bond issues to agree on certain “reserved matter modifications” to the most important terms and conditions of all outstanding series of bonds (including the financial terms) that are binding for the holders of all outstanding series of bonds with (1) either (i) the affirmative vote of all holders of at least 75 per cent represented at separate meetings or (ii) a written resolution signed by or on behalf of all holders of at least 66 2/3 per cent of the aggregate principal amount of all outstanding series of bonds (taken in the aggregate) and (2) either (i) the affirmative vote of the holders of more than 66 2/3 per cent represented at a meeting or (ii) a written resolution signed by or on behalf of holders of more than 50 per cent of the aggregate principal amount of each outstanding series of bonds (taken individually) and the consent of the Issuer (so-called “Cross Series Modification Clauses”). Italy has included the EU Collective Action Clauses and the Cross Series Modification Clauses in the documentation of all new bonds issued since January 1, 2013. On December 14, 2018, a reform of the model EU Collective Action Clauses was announced during the Euro Summit. The main purpose of the new model was to introduce a “single-limb” voting mechanism under which Cross Series Modification Clauses are binding on all holders of series of debt securities aggregated in one voting group if the proposed modifications are approved by holders of a majority of all securities aggregated in the voting group. Such mechanism is different from the “double-limb” voting arrangement, which requires both a positive vote at the level of each affected class of holders of series of debt securities, and an overall aggregated positive vote of all holders of series of debt securities aggregated in one voting group. On November 30, 2021, the euro area Member States agreed to introduce the single-limb Collective Action Clauses for all new Eurozone government securities with maturity exceeding one year. The single-limb voting mechanism was originally intended to be in use as from January 1, 2022, but will now be implemented on the first day of the second month following the entry into force of the agreement amending the ESM Treaty. In the meantime, the euro area Member States have agreed to begin the phase out of the double-limb Collective Action Clauses (and no Collective Action Clauses) issuance from January 1, 2023, and to a maximum percentage of annual government securities issuance, without single-limb Collective Action Clauses, for each year, with a view of having only 5% of such issuances by 2023 and onwards. The percentages may be revisited if required by market conditions. For

additional information regarding Italy’s implementation of EU Collective Action Clauses, see “Public Debt—Summary of External Debt.”

Gross Domestic Product

The following table sets forth information relating to nominal (unadjusted for changing prices) GDP and real GDP for the periods indicated.

GDP Summary

| | 2018 | 2019 | 2020 | 2021 | 2022 |

Nominal GDP (in € millions)(1) | 1,771,391 | 1,796,649 | 1,661,240 | 1,822,345 | 1,946,479 |

Real GDP (in € millions)(2) | 1,720,515 | 1,728,829 | 1,573,680 | 1,704,512 | 1,767,998 |

| Real GDP per cent change | 0.9 | 0.5 | (9.0) | 8.3 | 3.7 |

| Population (in thousands) | 59,817 | 59,641 | 59,236 | 59,030 | 58,851 |

__________________________

| (1) | Nominal GDP (in € millions) calculated at current prices. |

| (2) | Real GDP (in € millions) at constant euro with purchasing power equal to the average for 2015. |

Source: ISTAT.

Private Sector Consumption. In 2022, private sector consumption in Italy increased by 4.6 per cent, compared to a 4.7 per cent increase in 2021, supported by savings accumulated during the Coronavirus pandemic and by the expansion of consumer credit. Purchases of non-durable goods and purchases of durable goods such as motor vehicles, white goods and consumer electronics, increased by 0.3 per cent and 0.5 per cent in 2022, respectively, while consumption of semi-durable goods increased by 12.3 per cent. Services increased at a pace of 8.8 per cent compared to 2021, representing 51.0 per cent of the total private sector consumption.

Public Sector Consumption. In 2022, public sector consumption in Italy remained stable compared to a 0.6 per cent increase in 2021, mainly due to the easing of the Coronavirus pandemic.

Gross Fixed Investment. In 2022, gross fixed investment in Italy increased by 9.4 per cent. Such increase, albeit at a slower pace than in 2021, was mainly driven by the boost to businesses sustained by the Government’s measures to counter the effects of the increase in energy prices.

Net Exports. In 2022, exports of goods and services increased by 9.4 per cent in volume compared to a 14.0 per cent increase in 2021. Such lower increase rate was mainly due to the general uncertainty generated by the conflict in Ukraine and the increase in energy prices. Exports of goods increased at a lower pace compared to 2021 by approximately 6.1 per cent over the previous year. Italy’s world market share in 2022 remained stable at approximately three per cent at current prices and exchange.

Imports. In 2022, imports of goods and services registered a 11.8 per cent increase compared to 2021, mainly driven by the import of services.

Strategic Infrastructure Projects. Italy’s infrastructure is still significantly underdeveloped compared to other major European countries.

Italy adopted legislation in 2001 (the “Strategic Infrastructure Law”) providing the government with special powers to plan and realize those infrastructure projects considered to be of strategic importance for the growth and modernization of the country, particularly in the Mezzogiorno. The Strategic Infrastructure Law is aimed at simplifying the administrative process necessary to award contracts in connection with strategic infrastructure projects and increase the proportion of privately financed projects. In the last decade, beginning with the Strategic Infrastructure Law, progress was made in the planning of public works, starting to overcome historical weakness linked to long procedures due to overlapping powers and responsibilities among different levels of government. In 2021 and 2022 general government expenditure for investments was 2.9 per cent and 2.7 per cent of GDP, respectively.

Principal Sectors of the Economy

In 2022, value added increased by 3.9 per cent, compared to an increase of 6.6 per cent in 2021, mainly driven by the construction sector.

The following table sets forth value added by sector and the percentage of such sector of the total value added at purchasing power parity with 2015 prices.

Value Added by Sector(1)

| | 2018 | 2019 | 2020 | 2021 | 2022 |

| | in € millions | per cent of Total | in € millions | per cent of Total | in € millions | per cent of Total | in € millions | per cent of Total | in € millions | per cent of Total |

| Agriculture, fishing and forestry | 33,491 | 2.2 | 32,961 | 2.1 | 31,444 | 2.2 | 31,209 | 2.0 | 30,555 | 1.9 |

| Industry | 305,399 | 19.7 | 305,040 | 19.6 | 270,771 | 19.0 | 307,211 | 20.0 | 306,685 | 19.2 |

| of which: | | | | | | | | | | |

| Manufacturing | 258,285 | 16.7 | 257,139 | 16.5 | 222,737 | 15.6 | 256,354 | 16.7 | 256,825 | 16.1 |

| Mining | 6,304 | 0.4 | 5,900 | 0.4 | 6,510 | 0.5 | 10,597 | 0.7 | 11,267 | 0.7 |

| Supply of Energy, Gas, Steam, and Conditioned Air | 25,465 | 1.6 | 26,638 | 1.7 | 26,606 | 1.9 | 25,318 | 1.6 | 24,492 | 1.5 |

| Water Supply Drainage and Wasting | 15,418 | 1.0 | 15,348 | 1.0 | 15,133 | 1.1 | 17,178 | 1.1 | 16,751 | 1.0 |

| Construction | 66,386 | 4.3 | 68,171 | 4.4 | 64,150 | 4.5 | 77,361 | 5.0 | 85,183 | 5.3 |

| Services | 1,141,339 | 73.8 | 1,148,026 | 73.9 | 1,057,619 | 74.3 | 1,122,913 | 73.0 | 1,173,518 | 73.5 |

| of which: | | | | | | | | | | |

| Commerce, repairs, transport and storage, hotels and restaurants | 327,311 | 21.2 | 333,073 | 21.4 | 274,174 | 19.3 | 313,337 | 20.4 | 344,106 | 21.6 |