| | |

|

| | | Italy’s Stability Programme |

| | |

|

| | |

|

MINISTERO DELL’ECONOMIA E DELLE FINANZE | | Abridged version |

| | | Italy’s Stability Programme |

| | | |

| | | 2023 |

| | | |

| | | |

| | | Abridged version |

| | | |

| | | |

| | | |

| | | |

| | | |

| | | |

| | | Submitted by the Prime Minister |

| | | |

| | | Giorgia Meloni |

| | | |

| | | |

| | | and the Minister of the Economy and Finance |

| | | |

| | | Giancarlo Giorgetti |

| | | |

| | | |

| | | |

| | | |

| | | |

MINISTERO DELL’ECONOMIA E DELLE FINANZE | | Adopted by the Council of Ministers on 11 April 2023 and endorsed by the Parliament on 28 April 2023 |

FOREWORD

The Economic and Financial Document (DEF) is being published against an economic backdrop that remains uncertain and fraught with risks. Recently, the grip of the pandemic and the high energy price has loosened; however, the war in Ukraine continues to rage, geopolitical tensions remain high, and the rise in interest rates and the drain of liquidity operated by central banks have caused pockets of crisis to surface in the international banking system.

Nevertheless, despite such an uncertain situation, the Italian economy continues to show remarkable resilience and vitality. In 2022, GDP grew by 3.7 percent and gross fixed capital formation increased by 9.4 percent in real terms, reaching 21.8 percent of GDP, a level not seen in over twenty years. Although cyclical GDP growth slowed down in the second half of last year, with a slight contraction in the fourth quarter, the latest indicators suggest that economic growth already resumed in the first three months of the year. Business surveys also point to improved expectations for orders and production and an increase in investment compared to last year.

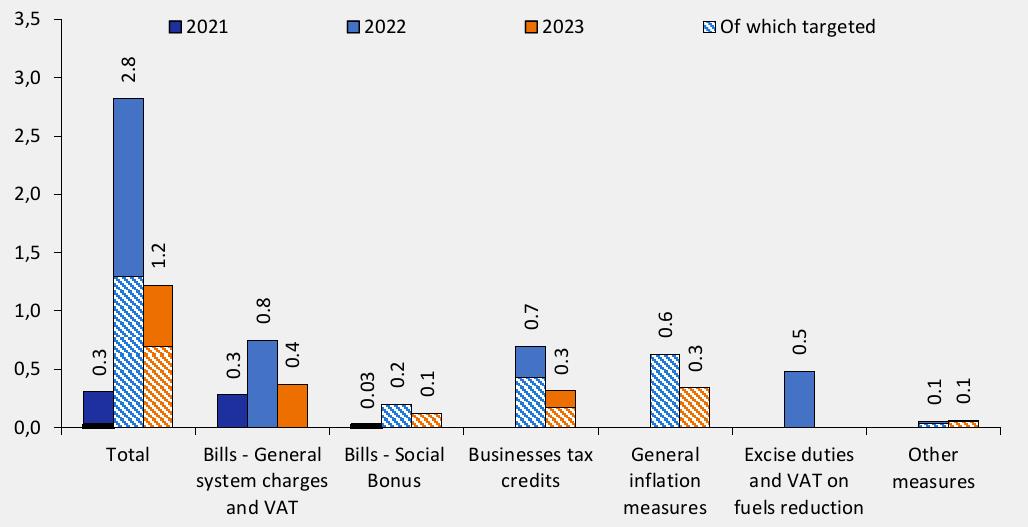

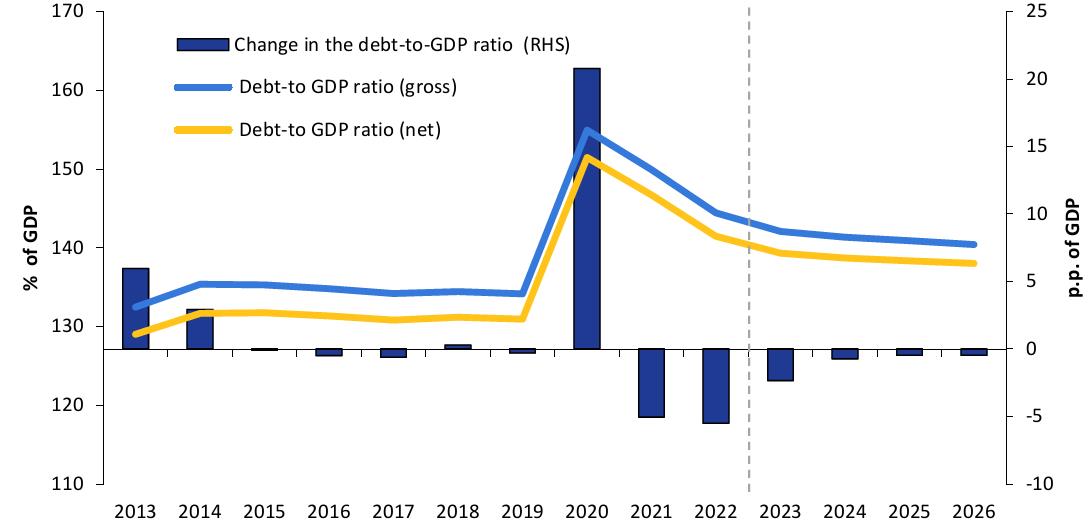

As far as public finance is concerned, 2022 was also positive in terms of the trend in public sector borrowing requirement, which fell to 3.3 percent of GDP, and in general government gross debt, which fell to 144.4 percent of GDP from 149.9 percent at the end of 2021. These results are quite remarkable if one considers the repeated fiscal policy measures adopted to support households and businesses exposed, in particular, to high energy prices, which according to the most up-to-date estimates amounted to 2.8 percent of GDP in gross terms.

The recent reclassification of tax credits related to building bonuses undertaken by ISTAT in agreement with Eurostat led to a shift from cash to accrual basis, resulting in a significant worsening of net borrowing (deficit) in 2022, which stood at 8.0 percent of GDP instead of close to the planned target of 5.6 percent. As a result of this accounting change and the recent changes in the building bonus scheme, the general government deficit based at existing legislation will however tend to improve in the coming years.

Tax credits held by the private sector will start to have a significant impact on cash borrowing requirements and will in any case make it more difficult to continue the rapid reduction in the debt ratio that has characterised the last two years, at least until 2026. In light of this framework, fiscal policy is called upon to ensure the full sustainability of public finance, while remaining ready to respond to new emergencies that may arise.

Given these premises, the Italian government’s first objective is to gradually overcome some of the extraordinary fiscal policy measures implemented over the last three years, and to identify new interventions both to support the most vulnerable and to relaunch the economy.

| MINISTRY OF ECONOMY AND FINANCE | V |

| | ECONOMIC AND FINANCIAL DOCUMENT 2023 |

The decision made in the budget law for 2023 to put an end to some emergency measures such as the cuts in excise duties on fuels, while maintaining a high degree of support for households and businesses to curb high energy prices throughout the first quarter, has proved successful. In particular, the cost of the measures against high energy prices for businesses was lower than estimated in the budget law by about five billion.

These resources made it possible to finance new measures to support households, businesses, and the national health system and its operators. The measures contained in Decree-Law No. 34 of 30 March 2023 extended the measures to curb high energy prices for the second quarter, remodelling them. An appropriation of one billion was also provided to fund a further intervention to mitigate the cost of energy for households in the fourth quarter of the year, which will be activated if the price of natural gas is above EUR 45/MWh. In addition, the ‘social energy bonus’ for households with at least four children remains in force and has been increased for families at risk of poverty. The same Decree-Law also covers additional needs of the healthcare system.

The gross impact of measures to counter the high energy price for 2023, including the new measures, amounts to 1.2 percent of GDP. More than half of this amount is directed towards the weakest segments of the population and the companies most exposed to high energy prices, in line with the recommendation of the European Council to favour targeted measures.

The normalisation of fiscal policy relies as well on the revision of building incentives, in particular the so-called superbonus 110 for energy efficiency and earthquake-proofing and the external renovation bonus. The draught of these two measures was significantly higher than originally estimated. In view of their onerousness, the Italian government first intervened by reducing the superbonus rate to 90 percent, except in certain specific cases, for expenditure incurred in 2023.

Subsequently, Decree-Law No. 11 of 16 February 2023 eliminated the possibility of opting for the transfer of the credit or the discount on the invoice instead of the direct use of the deduction, with the exclusion of certain cases. Moreover, the progressive saturation of the purchasing capacity of the banking system had de facto slowed down the transfer of credits, leading in many cases to a lack of liquidity for companies in the construction sector. In order to restart the credit market, the Italian government developed a series of measures that were included in the law converting the abovementioned Decree.

Once this phase is over, the Italian government intends to review the entire matter of building incentives in such a way as to combine the drive for energy efficiency and earthquake-proofing of buildings with the needs of public finance sustainability and distributive equity.

The second objective of the economic-financial planning is to reduce the general government deficit and the debt as a ratio to GDP gradually, but sustainably. With unchanged consistency, the Italian government therefore confirms the net borrowing-to-GDP targets already declared in November in the

| VI | MINISTRY OF ECONOMY AND FINANCE |

Draft Budgetary Plan (DBP), namely 4.5 percent this year, 3.7 percent in 2024 and 3.0 percent in 2025. The target for 2026 is set at 2.5 percent.

The corresponding development of the primary balance (i.e., net borrowing excluding interest payments) shows a small surplus (0.3 percent of GDP) already in 2024 and then markedly positive values in the following two years, 1.2 percent of GDP in 2025 and 2.0 percent of GDP in 2026.

In terms of the structural balance (i.e., adjusted for the output gap and one-off and other temporary measures), the planned reduction is consistent with the current rules of the Stability and Growth Pact with respect to both the so-called ‘corrective arm’ (until the deficit reaches 3 percent of GDP) and the ‘preventive arm’ (once the deficit falls below 3 percent).

After several years, the European Commission decided to reactivate the Stability and Growth Pact as early as 2024. At the same time, last November it presented a proposal to revise the budgetary rules and other aspects of economic governance, including the macroeconomic imbalances procedure (MIP). On 14 March, the ECOFIN Council approved a resolution calling on the Commission to rapidly present the relevant legislative proposals so that they could be approved by the end of the year.

The Commission’s SGP reform proposal focuses on an expenditure rule whose targets are modulated according to the sustainability of each Member State’s public debt. Consistent with the parliamentary resolution of 9 March, during the debate in the ECOFIN and its subcommittees, the Italian government supported the main lines of the Commission’s proposal, while highlighting some critical points (e.g. the categorisation of Member States according to the severity of public finance ‘challenges’) and proposing the adoption of preferential treatment for public investments to fight climate change and promote digital transition (the two pillars of the NRRP), as well as defence spending resulting from commitments undertaken in international fora. The Italian government also supports the need for enhanced symmetry in the MIP and will keep supporting these positions in the negotiations that will follow the presentation of the Commission’s legislative proposals.

The third priority objective that inspires the Italian Government’s economic policy is to continue to support the recovery of the Italian economy and the achievement of higher GDP growth rates and economic well-being of its citizens than those recorded in the past two decades.

The GDP growth forecasts in this Document are extremely prudent in nature, as they are based on cautious and reliable budget projections, which earned them validation by the Parliamentary Budget Office. In the trend scenario under existing legislation, GDP is projected to grow in real terms by 0.9 percent in 2023 - a figure revised upward in comparison to November’s DBP, in which growth in 2023 was set at 0.6 percent - and then to 1.4 percent in 2024, 1.3 percent in 2025 and 1.1 percent in 2026.

The trend projection for 2024 is revised downwards (from 1.9 percent) due to a less favourable configuration of exogenous variables compared to last November. The projection for 2025, on the other hand, is in line with the DBP,

| MINISTRY OF ECONOMY AND FINANCE | VII |

| | ECONOMIC AND FINANCIAL DOCUMENT 2023 |

while the further deceleration foreseen for 2026 is due to the practice whereby as the projection goes further into the future the projected growth rate converges towards the estimate of potential GDP growth, which is estimated at just over 1 percent according to the methodology defined at EU level.

Although these forecasts are cautious, the will and the ambition of this government regarding the growth of the Italian economy is confirmed. In the short term, efforts will be made to support the resumption of growth signalled by the latest data, as well as to contain inflation. Against an estimated deficit based at existing legislation for the current year of 4.35 percent of GDP, maintaining the existing deficit target (4.5 percent) will make it possible to introduce – with a legislative measure to be adopted soon – a cut in social security contributions to be paid by employees with low to medium incomes of more than 3 billion for this year. This will support the purchasing power of households and contribute to the moderation of wage growth. Together with similar measures in the budget law, this decision testifies to the Italian government’s focus on protecting workers’ purchasing power and, at the same time, on wage moderation to prevent a dangerous wage-price spiral.

Also for 2024, public finance projections indicate that, given a trend deficit of 3.5 percent, maintaining the target of 3.7 percent of GDP will create a budget space of about 0.2 GDP points, which will be allocated to the Tax Pressure Reduction Fund. The financing of the so-called unchanged policies from 2024 onwards, as well as the continuation of the cut in the tax burden in 2025-2026, will be supported by a strengthening of the public expenditure review and increased cooperation between tax authorities and taxpayers.

Thanks to the new tax measures for 2023 and 2024 outlined here, GDP growth in the policy scenario is projected at 1.0 percent this year and 1.5 percent in 2024. Since the current deficit projections indicate the need for a more neutral stance of fiscal policy in the 2025-2026 period, the corresponding policy scenario GDP growth projections are equal to the trend ones. This point will be reconsidered if future revisions of the deficit projections indicate the existence of room for manoeuvre without jeopardising the abovementioned net borrowing targets.

A much larger contribution to raising growth in the period covered by this Document will come from the investments and reforms envisaged in the National Recovery and Resilience Plan (NRRP). The Italian government is working to obtain the third instalment of the NRRP by April and to revise or reshape some of the Plan’s projects to accelerate their implementation. The programme under the REPowerEU European initiative is also being prepared, which will include, among other things, new investments in energy transmission networks and production chains related to renewable energy sources.

The start-up of the NRRP suffered from the complexity and innovativeness of some projects, high prices and shortages of components and materials, and red tape. However, new measures have recently been implemented to reorganise the management of the NRRP and adapt procedures on the basis of the initial elements that emerged during implementation. Once the revision of some project lines has been finalised, all conditions are in place to accelerate the implementation of reforms and investments that will not only produce favourable

| VIII | MINISTRY OF ECONOMY AND FINANCE |

socioeconomic impacts, but also raise the economy’s growth potential, together with the completion of the effects of the reform of the Public Procurement Code and other planned reforms, such as that of taxation and finance for growth.

In order to make our country more dynamic, innovative and inclusive, it is not enough just to have the NRRP. Indeed, it is also necessary to invest in strengthening the country’s productive capacity and to work over a longer time horizon than that of the Plan, so as to create the right conditions to avoid new inflationary flare-ups. This is an issue that must be addressed not only in Italy, but also in Europe.

In this context, it is therefore entirely realistic to aim for an increase in the GDP growth rate and employment in the coming years that goes well beyond the forecasts in this Document, along a path of innovation and investment under the banner of ecological and digital transition and the development of infrastructure for the transmission of clean energy and sustainable mobility.

Reducing inflation and restoring the purchasing power of wages is the fourth key objective of the Italian government’s economic policy. Measures to curb high energy prices have been instrumental in slowing the rise in inflation from mid-2021 onwards. The fall in the price of natural gas since the end of last summer has also driven down the price of electricity. The price of oil fluctuated considerably, but although excise duties were brought back to pre-crisis levels in January, fuel prices returned to only slightly higher levels in the second half of 2021.

The inflation rate according to the national NIC index peaked at 11.8 percent in October and November and then dropped to 7.7 percent in March. Although food price growth remains very high (13.2 percent), the decline in energy prices points to a further decline in inflation later this year. Core inflation (excluding energy and fresh food) continued to rise to 6.4 percent in March but is also expected to decelerate in the coming months.

Regarding the consumption deflator, the forecast in this Document is for inflation to fall from an average of 7.4 percent in 2022, to 5.7 percent this year and then to 2.7 percent in 2024 and 2.0 percent in 2025-2026. The fall in inflation will be accompanied by the gradual recovery of wages in real terms, which will have to take place gradually and not mechanically, but in step with the increase in labour productivity.

The objectives summarised here and illustrated more fully in the Stability Programme and in the National Reform Programme are aimed at improving the well-being of citizens and the fairness of our society, the indicators of which are analysed and projected up to 2026 in the annex to the DEF. We are facing great challenges, from climate change to the demographic crisis of the Italian population, but also significant opportunities to open up a phase of development marked by innovation and environmental sustainability and that invests not only in the economic assets, but also in inclusion values, in order to reduce generational, geographical and gender-based gaps.

| MINISTRY OF ECONOMY AND FINANCE | IX |

| | ECONOMIC AND FINANCIAL DOCUMENT 2023 |

The reforms undertaken, starting with the tax reform, are intended to rekindle Italians’ confidence in the future, protecting families and the birth rate and, by recognising the entrepreneurial spirit as an engine of economic development, promoting work as an essential expression of human beings. Therefore, the crux of this Document is responsible ambition.

| | Giancarlo Giorgetti | |

| | Minister of Economy and Finance | |

| X | MINISTRY OF ECONOMY AND FINANCE |

INDEX

| I. | RECENT TRENDS IN THE ECONOMY AND THE PUBLIC FINANCE |

| | |

| II. | BASELINE MACROECONOMIC AND BUDGET FORECAST |

| II.1 | Baseline macroeconomic forecast |

| II.2 | Risks to the baseline macroeconomic forecast |

| II.3 | Budgetary outlook under existing legislation |

| | |

| III. | UPDATED POLICY SCENARIO |

| III.1 | Fiscal policy scenario |

| III.2 | Macroeconomic forecast under the policy scenario |

| III.3 | Budget balance, convergence towards the Medium-Term Objective and expenditure rule |

| III.4 | Debt-to-GDP ratio and the debt rule |

| | |

| IV. | SUSTAINABILITY OF PUBLIC FINANCES |

| | |

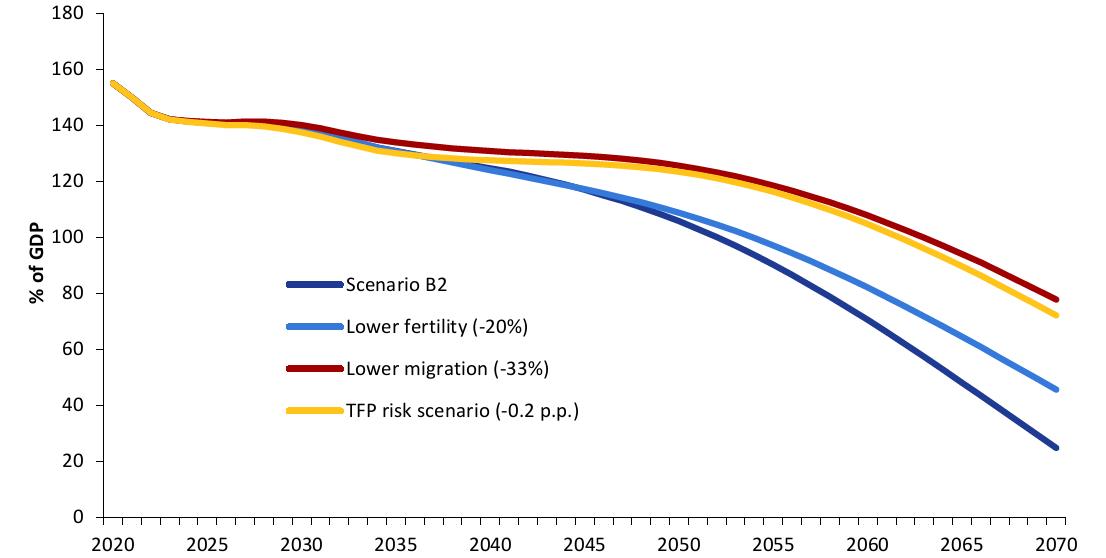

| IV.1 | Risk scenarios of public finances |

| IV.2 | Sustainability analysis of public debt |

| | |

| V. | ANNEX |

| MINISTRY OF ECONOMY AND FINANCE | XI |

| | ITALY’S STABILITY PROGRAMME 2023 |

TABLES

| Table II.1 | Summary macroeconomic under existing legislation scenario |

| Table III.1 | Public finance indicators |

| Table III.2 | Synthetic macroeconomic policy scenario |

| Table III.3 | Significant deviations |

| Table III.4 | Trends in current expenditure in relation to the expenditure benchmark |

| Table IV.1 | Sensitivity to growth |

FIGURES

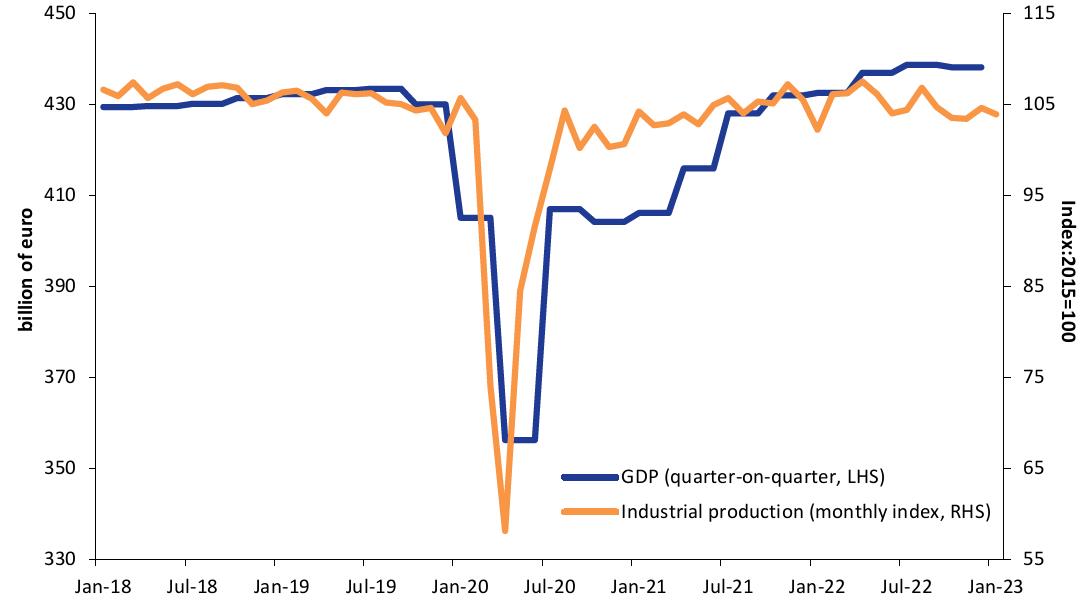

| Figure I.1 | Gross domestic product and industrial production |

| Figure I.2 | Wholesale prices of natural gas and electricity |

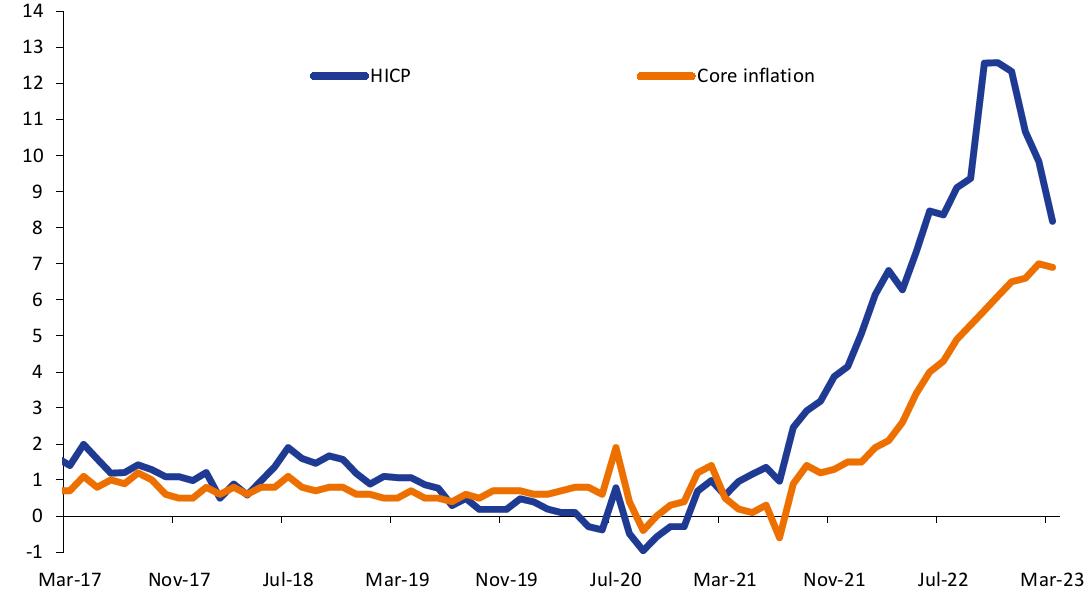

| Figure I.3 | Harmonised index of consumer prices |

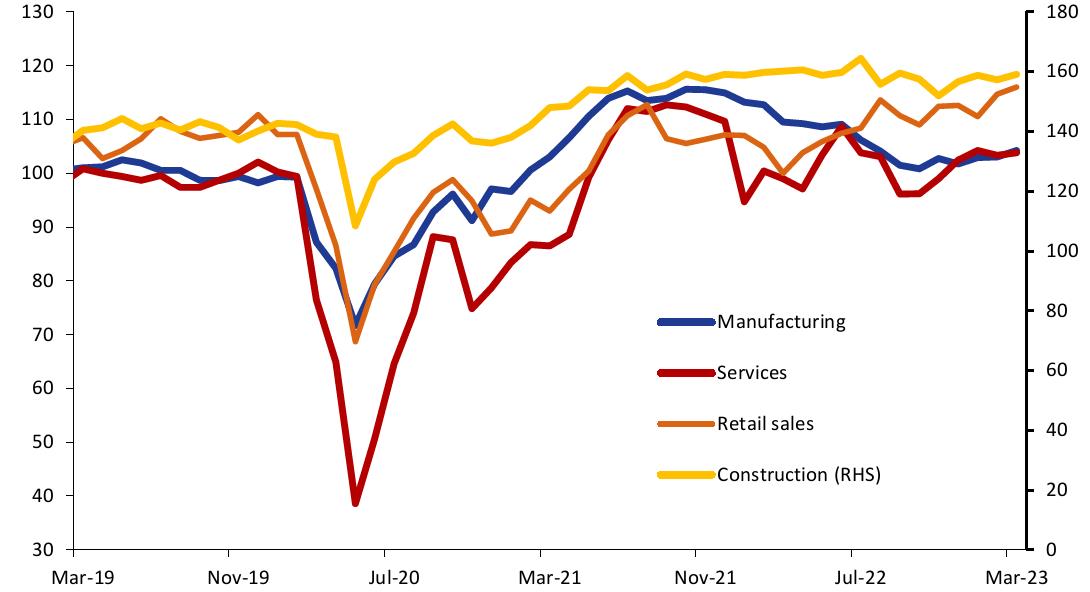

| Figure I.4 | Italian business confidence indexes |

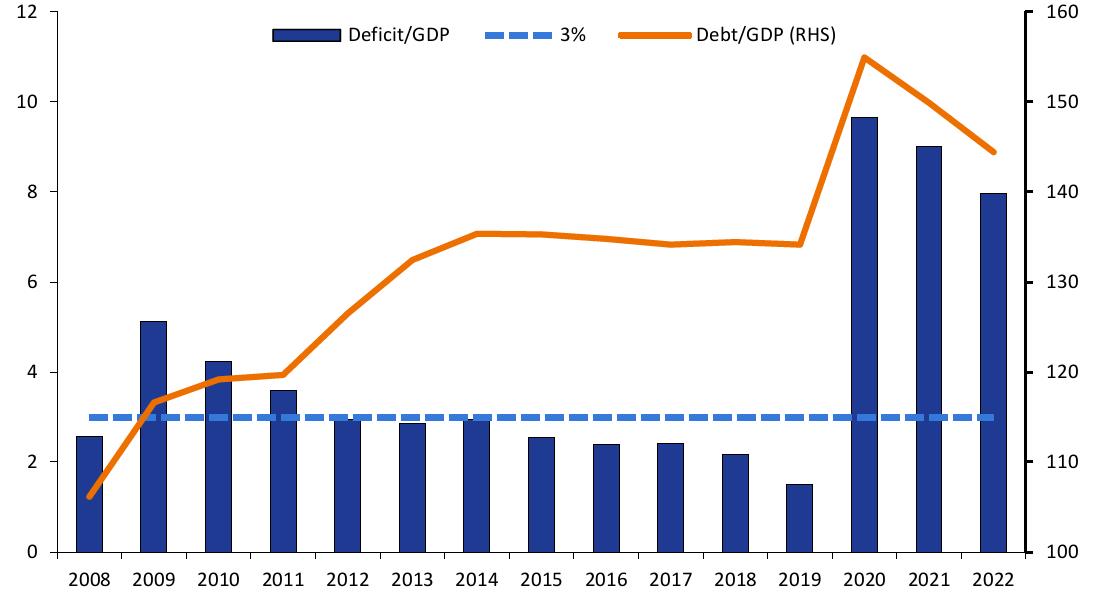

| Figure I.5 | Net borrowing and gross debt of the general government as a ratio to GDP |

| Figure II.1 | Price indices and balances at existing legislation |

| Figure III.1 | Evolution of the debt-to-GDP ratio gross and net of European aid |

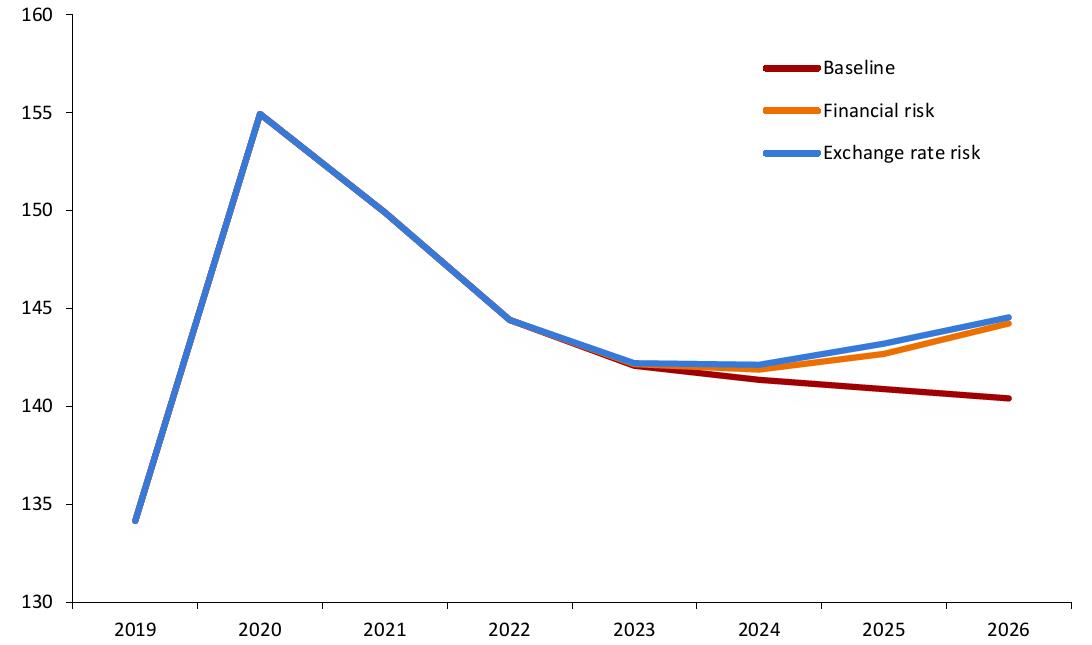

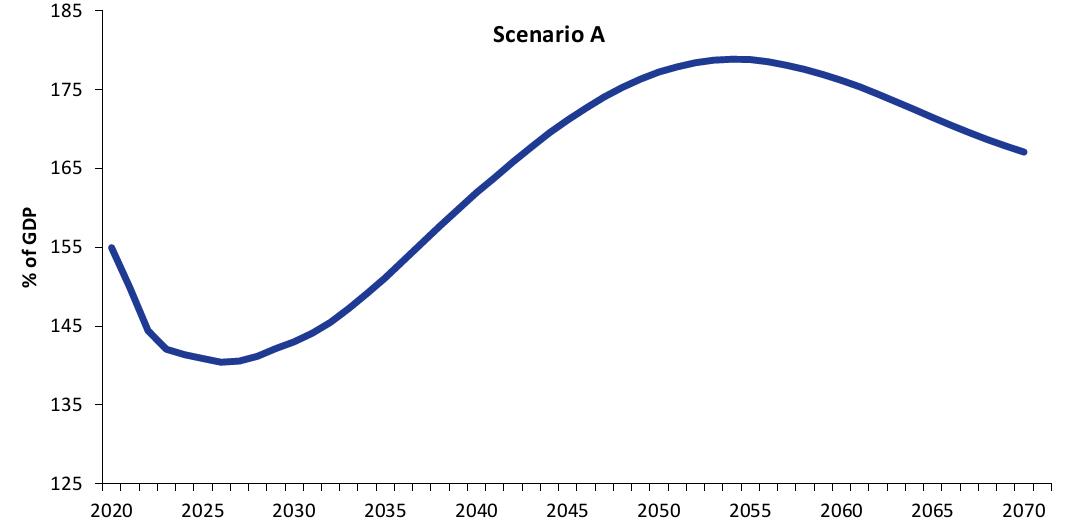

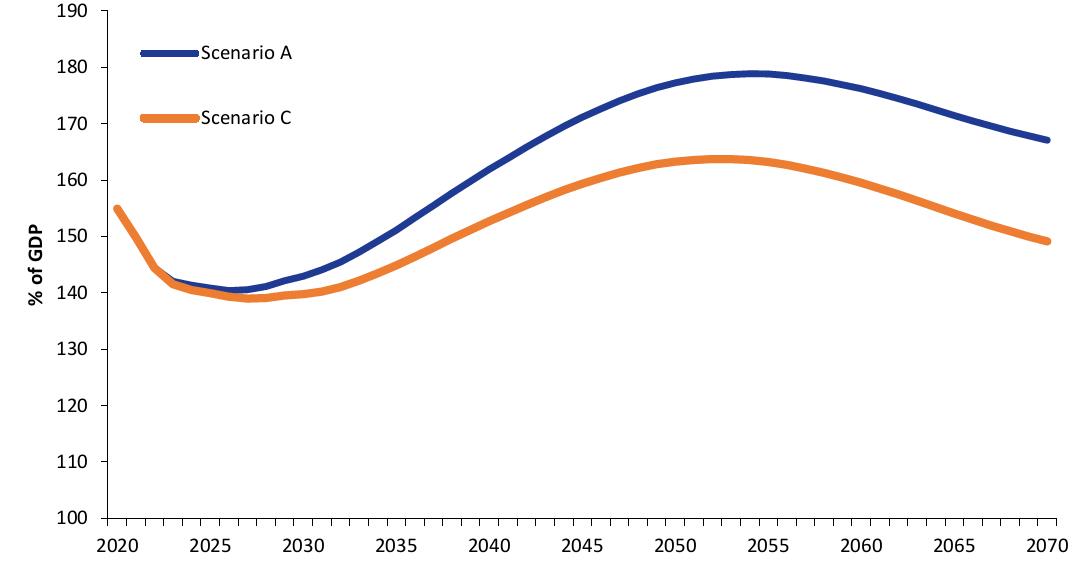

| Figure IV.1 | Dynamics of the debt-to-GDP ratio in sensitivity scenarios |

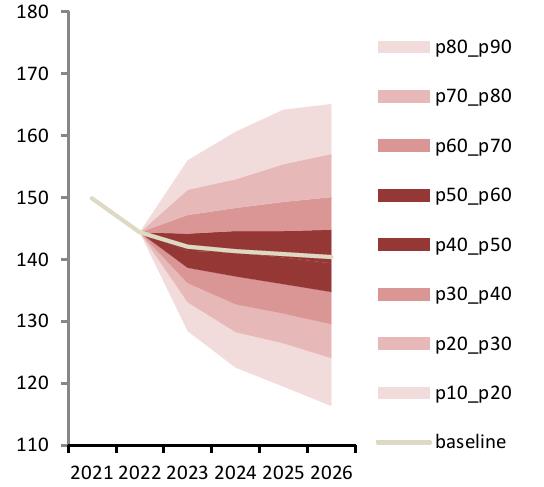

| Figure IV.2A | Stochastic simulation of the debt-to-GDP ratio under High- Volatility Shock |

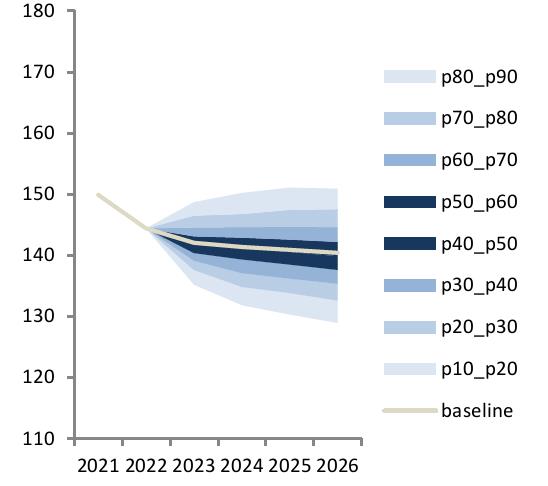

| Figure IV.2B | Stochastic simulation of the debt-to-GDP ratio under Limited Volatility Shock |

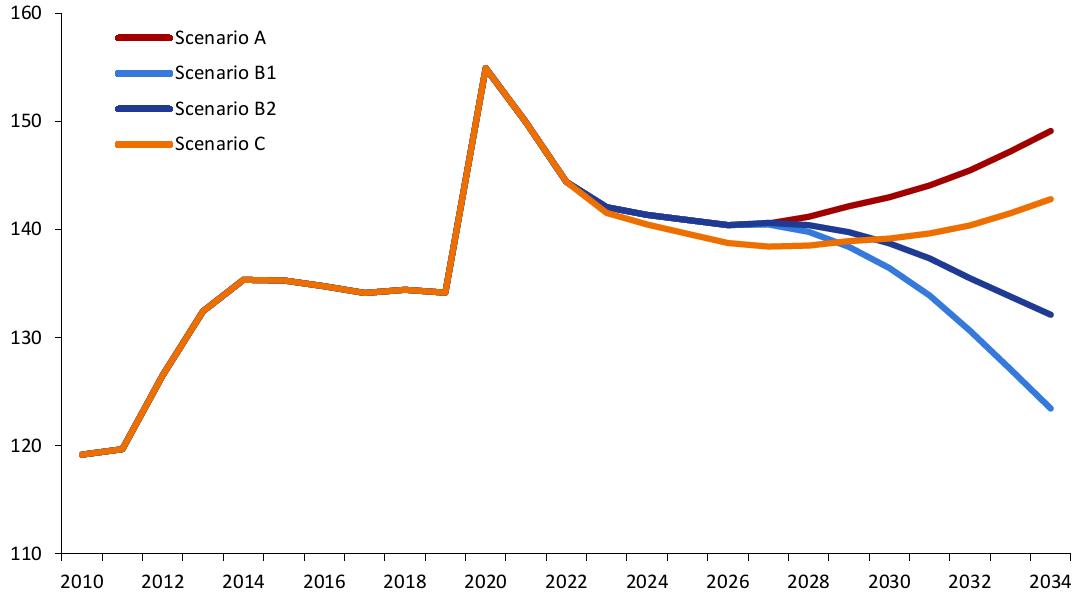

| Figure IV.3 | Medium-Term projection of the debt-to-GDP ratio |

| Figure IV.4 | Debt-to-GDP ratio in the reference scenario |

| Figure IV.5 | Impact of greater reform-related growth |

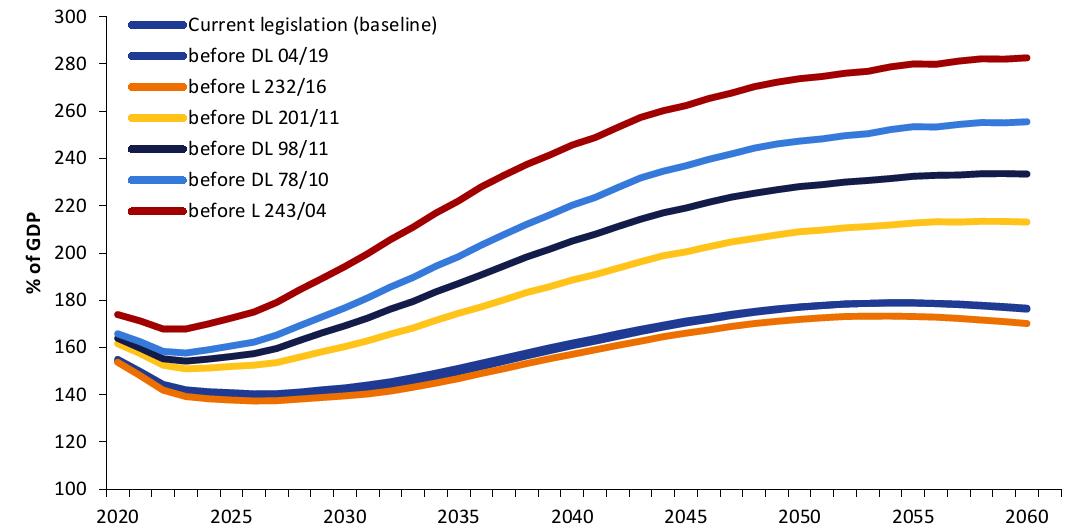

| Figure IV.6 | Impact of pension reforms |

| Figure IV.7 | Impact of a fiscal adjustment path in line with EGR. Sensitivity to adverse shocks |

FOCUS

| Chapter II | Inflation and price dynamics of energy and food |

| | Forecast errors for 2022 and revised estimates for 2023 and the following years |

| | A risk (or sensitivity) analysis on exogenous variables |

| | Superbonus 110: impact of accounting reclassification, temporary solutions and long-term perspectives |

| | Recent actions taken in response to high energy prices |

| XII | MINISTRY OF ECONOMY AND FINANCE |

| I. | RECENT TRENDS IN THE ECONOMY AND THE PUBLIC FINANCE |

In 2022, Italy continued the recovery of economic activity and the consolidation of public finances initiated the previous year. Despite the difficult economic environment, gross domestic product (GDP) grew by 3.7 percent in real terms, thus surpassing the pre-pandemic level of 2019 in the wake of the strong recovery in 2021 (7.0 percent).

General government net borrowing decreased by about one percentage point: 8.0 percent from 9.0 percent in 2021. The high level of the deficit is attributable to the accounting reclassification of tax credits related to building bonuses, without which the figure would have been 5.4 percent, considering only the effect on expenditure, and close to the official target of 5.6 percent of GDP, also considering the effect on tax revenues. The debt-to-GDP ratio was 144.4 percent, 1.3 percentage points lower than the forecast in last November’s DBP. Sustained nominal GDP growth (6.8 percent) contributed to the sharp reduction in the debt ratio of 5.5 percentage points compared to 2021. In 2021-22 period, the decline amounted to 10.5 percentage points, absorbing more than half of the increase in debt in 2020 due to the pandemic crisis.

Overall growth during 2022 was driven mainly by the recovery in services, thanks to the loosening of anti-Covid measures, and by household spending capacity, as boosted both by the previous accumulation of savings and by government income support policies. Industrial production, on the other hand, weakened gradually, consistent with a deteriorating international macroeconomic environment due to the war in Ukraine, rising energy prices and the gradual normalisation of monetary policy.

The Italian economy remained on an expansionary path until the summer of 2022, demonstrating considerable resilience; however, the slowdown factors mentioned earlier produced a slight contraction of GDP in the closing quarter.

In the first few months of this year, the indicators of the international cycle have been moving towards a phase of moderate recovery, coinciding with the slowdown in inflation. The latter is caused by both lower energy prices and the first effects of monetary policies on the financing conditions of households and companies.

More than a year after the start of the conflict in Ukraine, the humanitarian cost of the war continues to rise. According to UN agency figures, some 17.6 million people are currently in need of protection and humanitarian assistance. To isolate and weaken Russia’s economy, a considerable part of the international community, primarily the European Union, has tightened sanctions against Russia.

| MINISTRY OF ECONOMY AND FINANCE | 1 |

| | ITALY’S STABILITY PROGRAMME 2023 |

| FIGURE I.1: GROSS DOMESTIC PRODUCT AND INDUSTRIAL PRODUCTION |

|

| Source: ISTAT. |

European countries, and Italy in particular, have coped with the energy crisis caused by the drop in Russian gas imports by significantly reducing demand and diversifying supply sources. After the peaks recorded in the summer coinciding with the filling of storages, the price of European gas fell drastically.

| FIGURE I.2: WHOLESALE PRICES OF NATURAL GAS AND ELECTRICITY |

|

| Source: GME – Gestore Mercati Energetici. |

| 2 | MINISTRY OF ECONOMY AND FINANCE |

I. RECENT TRENDS IN THE ECONOMY AND THE PUBLIC FINANCE | |

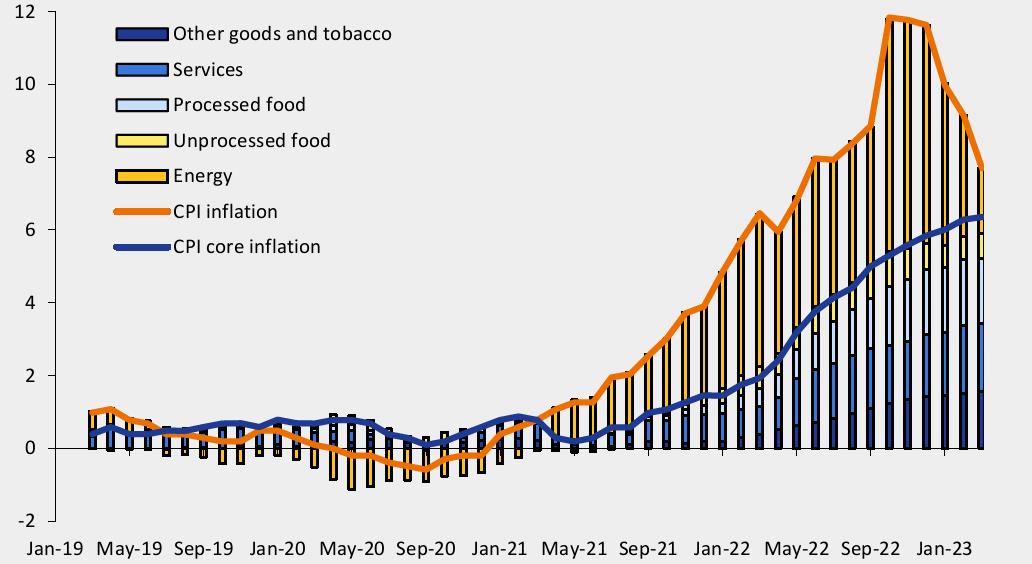

| FIGURE I.3: HARMONISED INDEX OF CONSUMER PRICES (% Y/Y) |

|

| Source: ISTAT. |

In 2022, the National Consumer Price Index for the whole nation (NIC) grew by 8.1 percent, accelerating significantly compared to 2021 (1.9 percent). Although overall inflation has been slowing since December, ISTAT’s preliminary estimates for March show the core component (which excludes unprocessed food and energy goods) still accelerating, at 6.4 percent trend. On the contrary, in March, the Harmonised Index of Consumer Prices (HICP) showed an initial, slight, decrease in the core component, to 6.9 percent from 7.0 percent in February. To counter inflationary pressures in the euro area, the European Central Bank (ECB) started a restrictive monetary policy cycle last July, which is having the first noticeable effects on the credit market and consequently on the money supply.

After some tensions on the yield spread between Italian government bonds and the Bund during last summer, the spread has decreased since October and has recently remained relatively stable. In addition, the recent financial turmoil caused a downward revision of market expectations on the ECB’s policy rates.

Despite the context of great uncertainty on both the geopolitical and economic fronts, the confidence of Italian households and businesses has been recovering strongly since October and consolidated in February and March. In particular, against a backdrop of a gradual improvement in assessments of price trends, households’ expectations on Italy’s economic situation and unemployment are more optimistic. The improvement in business confidence is equally significant, recording increases in all sectors in March. Notably, it reached a new high in retail trade.

Regarding public finance, the final estimate of net borrowing in 2022, at 8.0 percent of GDP, is approximately 2.4 percentage points higher than the 5.6 percent target set in last November’s DBP. As already mentioned, the gap is due to the revision of the accounting treatment of tax credits related to some building bonuses, which bring forward to the 2020-2022 period the financial effects that would instead be spread over the coming years under the previous statistical

| MINISTRY OF ECONOMY AND FINANCE | 3 |

| | ITALY’S STABILITY PROGRAMME 2023 |

treatment. For the same reason, the deficit-to-GDP ratio estimates for 2020 and 2021 were also revised upwards, by about 0.2 and 1.8 percentage points, respectively. Excluding the impact of this revision, the net borrowing in 2022 would have been close to the planned target of 5.6 percent (including the effect on tax revenues) in sharp decline from 7.2 percent of GDP in 2021, despite the increase in interest expenditure.

In fact, high inflation exerted pressure on index-linked securities, which affected the increase in interest expenditure, which amounted to 4.4 percent of GDP, a level higher than the 4.1 percent projected in the DBP and the 3.6 percent recorded in 2021. The high average duration of government bonds (around seven years) limited the impact of rising rates on the average cost of fixed-income debt.

On the other hand, rising inflation contributed to the 7.9 percent increase in final revenues, as also driven by economic growth. Together with the contained trend in primary expenditure, these allowed for an improvement in the primary balance, from -5.5 percent in 2021 to -3.6 percent of GDP in 2022, despite the considerable resources allocated to mitigate the effects of higher energy prices on households and firms.

The good performance of public finance is also reflected in the data on the cash requirements of the central government, which declined from about EUR 106.3 billion in 2021 to about EUR 66.8 billion in 2022 (a decline of 37.2 percent), contributing to the decline in the debt-to-GDP ratio. The reduction in borrowing requirements is substantial, at EUR 28.5 billion (24.7 percent), even excluding the Recovery and Resilience Facility grants received in August 2021 (almost EUR 9 billion) and April and November 2022 (a total of EUR 20 billion)1.

| FIGURE I.4: ITALIAN BUSINESS CONFIDENCE INDEXES |

|

| Source: ISTAT and MEF estimates for April 2020, when the survey was not published. |

________________________

1 Grants, unlike loans, are in fact accounted for as a reduction of borrowing requirements.

| 4 | MINISTRY OF ECONOMY AND FINANCE |

I. RECENT TRENDS IN THE ECONOMY AND THE PUBLIC FINANCE | |

| FIGURE I.5: NET BORROWING AND GROSS DEBT OF THE GENERAL GOVERNMENT AS A RATIO TO GDP |

|

| Source: ISTAT, Bank of Italy. |

| MINISTRY OF ECONOMY AND FINANCE | 5 |

| | ITALY’S STABILITY PROGRAMME 2023 |

| 6 | MINISTRY OF ECONOMY AND FINANCE |

| II. | BASELINE MACROECONOMIC AND BUDGET FORECAST |

II.1 BASELINE MACROECONOMIC FORECAST

Starting from an ISTAT estimate of real GDP growth in 2022 identical to that forecast in November in the revised and integrated Update of the Stability Programme – equal to 3.7 percent - the existing legislation scenario for 2023 is revised upward, to 0.9 percent, from 0.6 percent in the DBP. The revision considers the most recent economic indicators, which point to a faster recovery of economic activity than forecast in the Update, already starting from the first quarter. The new growth forecast for 2023 also considers the pronounced reduction in energy prices and the improved harmony of the recently observed international environment, as mentioned in the previous paragraph.

Expected GDP growth for the current year is driven by domestic demand net of inventories (0.8 percentage points) and net exports (0.3 percentage points); exports still show a substantial increase (+3.2 percent), as has been the case for several years now. Inventories, on the other hand, would make a slightly negative contribution. Projections assume that firms, with the marked drop in oil and gas prices, and also benefiting from the resources provided for in the RRP, will sustain the demand for investments, as driven by the machinery and equipment and construction components. In addition, companies might only be partially affected by the rise in interest rates due to the self-financing possibilities resulting from recent, high profit margins.

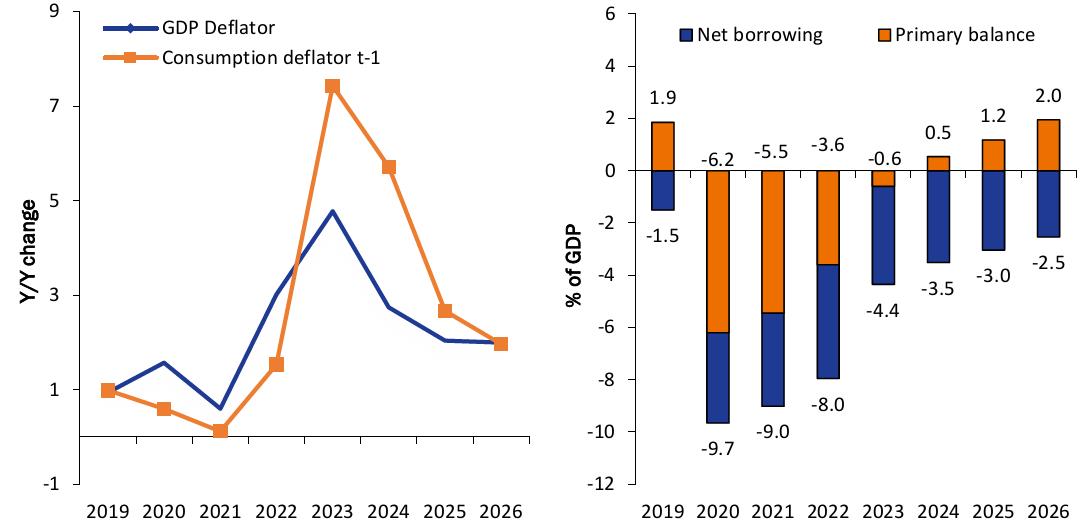

The new macroeconomic forecast is also characterised by a slightly higher inflation rate than envisaged last November. The household consumption deflator is expected to increase by 5.7 percent in 2023, against a projection of 5.5 percent in the Update of the Stability Programme, decelerating from the 7.4 percent observed in 2022. The GDP deflator growth forecast, at 4.1 percent in the Update, is revised to 4.8 percent. This brings the new nominal GDP growth forecast to 5.7 percent.

Despite the slowdown in price dynamics, consumer purchasing power will still be affected by overall high inflation. However, starting in the second half of the year, real income is expected to rise moderately thanks to the resilience of the labour market and the recovery of wages in the private sector, as well as the gradual easing of inflation. The unemployment rate would fall from 8.1 percent on average in 2022 to 7.7 in the current year.

| MINISTRY OF ECONOMY AND FINANCE | 7 |

| | ITALY’S STABILITY PROGRAMME 2023 |

| TABLE II.1: SUMMARY MACROECONOMIC UNDER EXISTING LEGISLATION SCENARIO (1) (percentage changes, unless otherwise indicated) |

| | 2022 | 2023 | 2024 | 2025 | 2026 |

| GDP | 3.7 | 0.9 | 1.4 | 1.3 | 1.1 |

| GDP deflator | 3.0 | 4.8 | 2.7 | 2.0 | 2.0 |

| Consumption deflator | 7.4 | 5.7 | 2.7 | 2.0 | 2.0 |

| Nominal GDP | 6.8 | 5.7 | 4.2 | 3.4 | 3.1 |

| Employment (FTE) (2) | 3.5 | 0.9 | 1.0 | 0.9 | 0.8 |

| Employment (LFS) (3) | 2.4 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 0.7 | 0.8 |

| Unemployment rate | 8.1 | 7.7 | 7.5 | 7.4 | 7.2 |

| Current account balance (balance in % GDP) | -0.7 | 0.8 | 1.3 | 1.6 | 1.6 |

(1) Any inaccuracies are the result of rounding. Database updated with the information available as of 5 April. (2) Employment in terms of full-time equivalent (FTE). (3) Employment (persons) based on the Labour Force Survey. |

As regards the coming years, the GDP growth forecast for 2024 is revised downward in comparison with the Update (to 1.4 percent, from 1.9 percent). The estimate for 2025 is unchanged (1.3 percent), while that for 2026, which is not considered in the Update horizon, is set at 1.1 percent; the latter value reflects the usual approach of making the forecast converge towards the potential growth rate of the Italian economy, estimated at 1.1 percent on average over the four-year planning period using the methodology agreed on at a European level.

The downward revision of the growth rate forecast for 2024 is partly explained by a less favourable international environment, which, contrary to the estimates for the current year, would push down the growth rate of the economy compared to the values projected in the Update. In this respect, the monetary policy followed by the central banks of major western countries plays a prominent role, as it has become more restrictive than foreseen last autumn when the Update was drawn up.

As is well known, an increase in interest rates transmits its full effects on the economy with some lag; therefore, especially in 2024, domestic demand would be less dynamic than last forecast due to recent restrictive interventions by the ECB. Lastly, the moderation in the international business cycle, resulting in lower international trade projections, and an appreciation of the euro exchange rate against the dollar2 contribute to the revision.

Taken as a whole, economic growth forecasts are characterised by caution and prudence, also considering reasons of expediency and prudent planning of public accounts.

Certainly, the implementation of the investment and reform plan organic to the RRP legitimately and correctly creates expectations of higher growth levels than those currently projected in official documents. These expectations are supported by estimates made both by the European Commission3 and within the national planning documents and in the NRP. For the prudential reasons mentioned above, this Document only partially incorporates the effects on productivity and labour supply associated with the implementation of the RRP in the growth estimates.

________________________

2 See the Focus ‘Forecast errors for 2022 and revised estimates for 2023 and the following years’ in this Chapter.

3 For example, according to a study by the European Commission in 2021, ‘we find that the level of real GDP in the EU-27 can be around 1.5 percent higher than without NGEU investments (in 2024). A significant part of this impact comes from spillover effects, pointing to the benefits of joint action’.

| MINISTRY OF ECONOMY AND FINANCE | 8 |

II. BASELINE MACROECONOMIC AND BUDGET FORECAST | |

However, the Stability Programme analyses the favourable impact on public finances of the higher economic growth attributable to the RRP in Chapter IV, within the paragraphs devoted to the analysis of the medium- and long-term sustainability of public debt.

Over the past few years, Italy’s economic growth has surprised on the upside several times, gradually leading the major forecasters - including the main international bodies - to revise their estimates upwards. The Italian government is confident that this will also be the case in the coming years.

The macroeconomic forecast under existing legislation was validated by the Parliamentary Budget Office (PBO) in a note of 7 April 2023.

| FOCUS | Inflation and price dynamics of energy and food |

| Exceptional price growth characterised 2022, driving the inflation rate to levels not seen in more than three decades. Last year, consumer prices, as measured by the NIC (National Consumer Price Index for the whole nation), grew by 8.1 percent, up from 1.9 percent in 2021. |

The inflationary flare-up first affected the so-called volatile component of the reference price basket, which includes energy goods and food. These items weigh about 10 and 18 percent respectively in the expenditure index4. Less affluent households have been hit harder, as a proportionally higher share of their income is spent on these types of purchases and uses. |

| This focus goes into more detail on the causes and the mechanism through which the increase in energy prices occurred, which was subsequently transmitted to core inflation, and illustrates the underlying reasons for the forecast of a gradual unwinding of the phenomenon contained within the Stability Programme. |

| |

| The shock from energy and food prices |

The first inflationary increase occurred as early as 2021; gas and electricity prices started to rise rapidly in the second half of the year, reaching considerable levels compared to the recent past. The increase became more pronounced following the war in Ukraine on 24 February 2022, peaking during the summer months; this was linked to an increasingly limited supply from Russia5 and a ‘race’ to build up stocks by European countries. |

| In August 2022, gas and energy prices exceeded their average value for the period 2015-2019 by a factor of ten, which was also reflected in energy bills. The price increase of the regulated energy goods component of electricity and gas averaged 65.6 percent over the year, three times the increase experienced in 2021 (+22.1 percent). By contrast, the non-regulated component of energy goods, which includes not only electricity and natural gas but also the fuel price, grew by +44.7 percent, four times the annual growth experienced in 2021 (+9.9 percent). In this context, the measures taken during 2022 to reduce the cost of bills and/or to contain the level of energy prices, such as the social bonus, the sterilisation of system charges and the reduction of VAT on gas and excise duties on fuels, helped to contain the increase in prices. |

| The Russian-Ukrainian conflict and adverse weather conditions also affected the food sector, for which price growth in 2022 amounted to 8.8 percent, clearly accelerating compared to |

________________________

4 In fact, one part of foodstuffs, processed goods, is part of core inflation: the latter weighs about 83 percent in the overall basket. Processed and unprocessed goods weigh 11.5 percent and 6.6 percent respectively. Overall, energy goods weigh in at about 10 percent, of which 8 percent concerns the unregulated component.

5 The supply difficulties came from unscheduled extraordinary maintenance activities of the Nord Stream 1 pipeline by Gazprom. It is also worth mentioning the episode of 26 September 2022 concerning the explosion of 3 out of 4 undersea pipes of the Nord Stream gas pipeline to Germany, which further reduced gas flows from Russia.

| MINISTRY OF ECONOMY AND FINANCE | 9 |

| | ITALY’S STABILITY PROGRAMME 2023 |

| | 2021 (0.5 percent). This provided an additional boost to inflation. More specifically, the largest price increases in 2022 were in unprocessed (fresh) food, whose index rose by 9.1 percent, while processed food prices rose by 8.5 percent6 . |

The price increase is primarily related to the impact of the conflict on exports of food commodities, such as wheat, maize, and sunflower oil, of which Ukraine and Russia themselves are important producers worldwide. On average for the year 2022, the price of food commodities on international markets rose by about 20.0 percent7. The peak was recorded between February and March 2022; after further fluctuations, we are witnessing a downward phase in wheat and maize prices, which have come back to the values of the end of 2021. |

The sector was also affected by the price of chemicals and fertilizers used in agriculture, whose production costs were pushed up by the energy shock. In addition, Russia is one of the world’s largest producers and exporters of fertilizers. The rise in prices peaked in August 2022 at 46.2 percent. The subsequent deceleration led to a year-on-year change of 21.5 percent in January 20238. |

| Regarding the production costs of food, the increase in of agricultural and forestry machinery prices, whose producer price index has recorded trend increases of just under 10 percent in recent months, must be considered. |

Finally, in 2022, the low spring temperatures, the exceptional heatwaves in the summer period, the almost total absence of rainfall and the dry climate strongly affected several traditional productions in the country. According to ISTAT, net of price changes, in 2022 Italian agricultural production decreased by 0.7 percent and crops by 2.2 percent.9 |

| This was reflected in consumer prices. Overall, the year-on-year increase in fresh food prices peaked at 12.9 percent in October. The acceleration of processed food prices was later but sharper and is still ongoing: in February 2023 the year-on-year change was 15.5 percent. |

| The rise in energy and food prices spread progressively to the main production sectors of the economy, which passed some of the higher costs on to consumers. This resulted in a continuous rise in core inflation from May 2021, whose average growth last year was 3.8 percent. The year 2022 ended with a year-on-year change of 5.8 percent, rising to 6.4 percent in March 2023, according to the latest ISTAT data. |

| |

| Inflation projections for the current year |

The inflation rate for March 2023, as estimated by ISTAT, shows the fourth consecutive decline in the change in the NIC index, which increased to 7.7 percent from its Novem-ber peak of 11.8 percent. Although consumer price tensions remain widespread in sev-eral categories of goods and services, there is a marked slowdown in energy goods pric-es (in year-on-year terms to 10.8 percent, from the peak of 71.1 percent in October 2022), which affects the regulated component to a greater extent (to -20.4 percent, from 51.6 percent in October

|

________________________

6 Among food products, the highest growth in 2022 was experienced by flour and other cereals, rice, bread, pasta and couscous, milk (especially long-life milk), butter and eggs, fresh fruit and frozen vegetables, frozen fish and poultry, olive oil and sugar.

7 With the largest increases occurring in the price of maize (28.3 percent), rough rice (23.6 percent) and wheat (19.5 percent).

8 Of lesser magnitude was the price increase for the manufacture of agrochemicals and other agricultural chemicals, which spiked more than 13 percent during 2022 to stand at 1 percent in January.

9 In particular, the production of olive oil (-17 percent), cereals (-10.4 percent), fodder plants (-5.5 percent), industrial plants (-4.5 percent), potatoes (-1.9 percent) and fresh vegetables (-1.8 percent) decreased in volume. By contrast, the production of fruit crops (+6.8 percent) and floriculture (+1.1 percent) increased in volume. In 2022, the prices of crop products grew by an average of 17.8 percent, with peaks of 40.3 percent for fodder, 39.9 percent for cereals, 21.2 percent for fresh vegetables, 14.7 percent for citrus fruits, 13.5 percent for industrial plants, 10.1 percent for wine and 6.6 percent for fresh fruit. The price of rice hit a high in February with a year-on-year increase of 41.8 percent.

| 10 | MINISTRY OF ECONOMY AND FINANCE |

II. BASELINE MACROECONOMIC AND BUDGET FORECAST | |

| | 2022) than the non-regulated component (to 18.9 percent, from 79.4 percent in October 2022). The March inflation assumption for 2023 was 5.1 percent. |

| The conditions are in place for the process of falling energy commodity prices, which started at the end of 2022 and became more pronounced in March 2023, to continue in the coming months. Indeed, gas and electricity prices in March were 62.5 percent and 54 percent lower, respectively, than in March 2022. The most recent forward price curves for gas, oil, and electricity are roughly stable throughout 2023, with only a gradual increase in the last months of the year. In recent weeks, forward prices have continued to move downwards. |

| On the protected energy goods market, ARERA has set gas tariffs down by 13.4 percent (EUR 46.58/MWh) for March, while electricity tariffs remain unchanged. The latter, which are updated quarterly, will record a 55.3 percent drop in the price on the bill in the second quarter, the result of a reduction in the cost of energy, only partially offset by the reintroduction of system charges. On the unprotected energy market, the downward trend of gas, oil and electricity is confirmed, whose forward prices in 2023 would nevertheless remain at slightly higher levels than the annual average prices recorded in 2021. |

| In light of these dynamics, it is reasonable to expect that the contraction of the energy component of the consumer price index will continue throughout 2023, both in the protected and unprotected market, although – in the case of the latter – there will be some delay in the adjustment of tariffs to the change in energy commodity prices. The run-up in food prices should also begin to slow down. However, while food commodity futures prices do not show any bullish signs over the next two years, it should not be forgotten that current and future weather conditions could adversely affect production and trigger new price tensions for some agri-food products. Overall, according to internal estimates, the core inflation component will tend to decelerate very slowly and gradually as a joint effect of a slowdown in the non-energy goods component and a stronger persistence of services. |

| The issue of inflation is constantly monitored by the government. While the comeback from the 2022 peaks in energy commodity prices is leading to a gradual loosening of some price containment measures, several measures to support households and businesses remain in place and would be reinforced in the event of new sudden price increases (see Focus ‘Recent initiatives taken in response to the high energy price’). |

| In conclusion, the inflation forecast in this Document is on a downward trend over the next three years. The estimate considers the easing of inflationary pressures already evident in the first months of 2023. This development is justified to a large extent by the well-established downward trend in energy prices. Indeed, the contribution of the energy component to the total change in the NIC index has been declining since the end of last year, giving way to the growing contribution of goods, including food, and services. Therefore, the return of core inflation is expected to be slower and more gradual, and although we are close to the peak, we may see a stabilisation phase in the dynamics before an actual drop in the second half of the year. In detail, the dynamics of the household consumption deflator is expected to be 5.7 percent in 2023, up from 7.4 percent in 2022. Thereafter, even if the deflationary momentum of the energy component is exhausted, the growth of the consumption deflator will fall to 2.7 percent in 2024, before stabilising at 2.0 in 2025 and 2026. |

| MINISTRY OF ECONOMY AND FINANCE | 11 |

| | ITALY’S STABILITY PROGRAMME 2023 |

| | FIGURE R1: INFLATION AND CONTRIBUTIONS OF MAIN AGGREGATES |

| | |

| | Source: MEF elaborations on ISTAT data. |

| FOCUS | Forecast errors for 2022 and revised estimates for 2023 and the following years 10 |

| |

This Focus provides an in-depth look at: (i) the forecast error for the year that has just ended; (ii) the factors that led to the change in growth estimates for 2023 and subsequent years. In both cases, the comparison is made with the forecasts made in the Update of the 2022 Stability Programme of last November. The main results are shown in Table R111 . |

| For 2022, the final figure was in line with the Update of the Stability Programme estimates: ISTAT certified an expansion of real GDP, in seasonally adjusted terms, of 3.8 percent. |

In terms of the components, household consumption and construction investment were more dynamic than expected, while both exports and imports underperformed; in terms of foreign trade, the contribution of net exports was better (less negative). On the price front, the growth of the GDP deflator was broadly in line with the forecast, while that of the consumption deflator exceeded expectations, being affected by stronger dynamics in the food and services components. |

The growth forecast for 2023 is revised upwards by 0.3 percentage points. A positive contribution to this revision is made by the improvement in the profile of international exogenous factors, amounting to 0.5 percentage points, and the stronger-than-expected reduction in gas prices. However, for reasons of prudence, the positive impact was only partially considered due to the high uncertainty characterising the international scenario. Finally, the differential of the carry-over effect on 2023 is nil, as the quarterly profile was also broadly in line with the November 2022 estimates. |

________________________

10 This Focus refers to the working-day adjusted quarterly economic accounts data published by ISTAT on 3 March 2023.

11 The forecasts for 2022 made in November included data from the National Accounts only up to the second quarter of last year, whereas the data published by ISTAT in March also refer to information from the second part of last year and revise the time series of previous quarters.

| 12 | MINISTRY OF ECONOMY AND FINANCE |

II. BASELINE MACROECONOMIC AND BUDGET FORECAST | |

| | TABLE R1: MAIN VARIABLES OF THE MACROECONOMIC FRAMEWORK (SEASONALLY ADJUSTED DATA) |

| | | 2022 Forecast | 2023 Forecast | of which: carry over effect on 2023 | of which: Exogenous impact | of which: other factors |

| | | Update 2022 | ISTAT | Delta 2022 | Update 2022 | SP 2023 | Delta 2023 | Delta (1) | Delta (2) | Delta (3) |

| | GDP | 3.8 | 3.8 | 0.0 | 0.7 | 1.0 | 0.3 | 0.0 | 0.5 | -0.1 |

| | Private consumption | 3.9 | 4.6 | 0.8 | 1.0 | 0.6 | -0.4 | -0.6 | 0.8 | -0.6 |

| | Government consumption | 1.4 | 0.0 | -1.3 | -2.6 | -1.3 | 1.2 | -1.4 | 0.0 | 2.6 |

| | Gross fixed capital formation | 8.7 | 9.7 | 1.0 | 3.0 | 3.7 | 0.7 | 1.9 | 0.6 | -1.8 |

| | Machinery, equipment and miscellaneous | 7.4 | 7.2 | -0.2 | 3.5 | 5.2 | 1.7 | 2.9 | 0.7 | -1.9 |

| | Constructions | 10.8 | 12.2 | 1.4 | 2.6 | 2.3 | -0.3 | 0.6 | 0.4 | -1.4 |

| | Exports of goods and services | 10.7 | 10.2 | -0.5 | 0.9 | 3.2 | 2.3 | 1.8 | -0.6 | 1.0 |

| | Imports of goods and services | 14.0 | 12.5 | -1.6 | 1.3 | 2.5 | 1.2 | -1.1 | 0.1 | 2.2 |

| | Deflators | | | | | | | | | |

| | GDP deflator | 3.0 | 3.0 | 0.1 | 4.1 | 4.8 | 0.7 | 0.4 | -0.1 | 0.4 |

| | Private consumption deflator | 7.0 | 7.4 | 0.5 | 5.5 | 5.7 | 0.2 | 1.5 | -1.0 | -0.2 |

| | Notes: Any inaccuracies result from rounding. |

| | |

| | Table R2 provides a summary of the impact on GDP growth of developments in the international environment, comparing it with what was assumed in the November 2022 Update. This impact, estimated using the ITEM econometric model, is more favourable for 2023. For the following two years, the impact is negative by -0.4 percentage points in 2024 and zero in 2025. |

| | |

| | TABLE R2: EFFECTS ON GDP OF THE INTERNATIONAL SCENARIO COMPARED TO THE UPDATE OF THE STABILITY PROGRAMME OF NOVEMBER 2022 (impact on growth rates) |

| | | 2023 | 2024 | 2025 |

| | 1. World trade | 0.0 | -0.1 | 0.1 |

| | 2. Oil and gas prices | 0.6 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| | 3. Nominal effective exchange rate | -0.1 | -0.1 | 0.0 |

| | 4. Interest rate assumptions | 0.0 | -0.2 | 0.0 |

| | Total | 0.5 | -0.4 | 0.0 |

| | Note to the Total: any inaccuracies result from rounding. Source: MEF elaborations. |

| | |

| | In detail, compared to the forecast of the Update of the 2022 Stability Programme, international trade is slightly revised downwards for the years 2023-2024 and then recovers in 2025. As a result, the effect of the revision of the world demand forecast on the rate of change of GDP is slightly negative in 2024 (-0.1 percent) and slightly positive in 2025 (0.1 percent). In the first months of this year, oil prices were lower than in the second half of 2022, although they remained at high levels above USD 80 per barrel. The current projection, based on futures contracts, forecasts lower oil price levels over the entire three-year period. After the 2022 peak, the price is expected to follow a gradual moderation in the |

| MINISTRY OF ECONOMY AND FINANCE | 13 |

| | ITALY’S STABILITY PROGRAMME 2023 |

| | following years12. Compared to the November forecast, the price level is only marginally lower in 2023-2025. By contrast, the price of gas has fallen more than expected since December. Specifically, after peaking between August and September last year, in the first two months of 2023 the price fell to pre-Russian-Ukrainian conflict levels. For the current year, according to the futures contracts, the price would be significantly lower than the previous year and would continue to fall to EUR 33.5/MWh in 2026. The gas price in 2023 would be about one third of the level projected in the Update, falling from EUR 144.6/MWh to EUR 50.6/MWh. Overall, over the 2023-2025 three-year period, the gas price would be on average about EUR 60/MWh lower. |

| | Cumulating the effects of the oil and gas declines would result in a positive impact of 6 tenths of a point for the rate of change of GDP in 2023. The impact would be zero in subsequent years. |

| | On the exchange rate front, the usual technical assumption that the exchange rate remains unchanged over the forecast horizon at the average levels of the most recent daily quotations (last 10 working days ending 8 March) was adopted for the currency projection. The update of the nominal effective exchange rate compared to November sees an appreciation of the euro against other currencies of 1.4 percent in 2023, with a negative macroeconomic impact of one-tenth of a percentage point on GDP growth in 2023 and 2024. |

| | The three-year profile of interest rates on government bonds is broadly in line with that of the Update, as a joint effect of the less accommodative policies confirmed by the monetary authorities and the markets’ expectations regarding the first cuts in the cost of money expected as early as the end of this year, after the recent financial tensions. Indeed, bond yields have been falling in recent weeks, with that of the ten-year BTP returning to levels close to 4 percent. Compared to the November forecast: (i) the yield on the BTP is slightly lower in 2023, the same in 2024 and slightly higher in 2025; (ii) the spread between the ten-year BTP and the ten-year Bund is smaller and is projected at just below 200 basis points for the current year; (iii) short-term market rates are instead higher in both 2023 and 2024. In particular, the econometric model estimates that an increase in average lending rates to the private sector will have negative effects on growth only in 2024 and amounting to -0.2 percentage points. |

| | The baseline macroeconomic forecast of this Document was validated by the Parliamentary Budget Office. The latter in February estimated GDP growth at 0.6 percent in 2023 and 1.4 percent in 2024. |

| | In its Winter Forecast, the European Commission forecast GDP growth for 2023 substantially in line with the trend growth published in this Document (0.8 percent compared to 0.9 percent); for 2024, a greater variance emerges (1.0 percent for the European Commission and 1.4 percent for the official estimates). The reasons for this deviation are presumably to be found not only in the recent reduction in gas price futures, but also in the different growth profile for 2023 underlying the forecasts, which implies a lower carry-over to 2024 for the European Commission. |

| | |

| | TABLE R3: GROWTH FORECAST FOR ITALY |

| | Real GDP (percent y/y) | Forecast date | 2023 | 2024 |

| | SP 2023 | Mar-23 | 0.9 | 1.4 |

| | OECD | Mar-23 | 0.6 | 1.1 |

| | UPB | Feb-23 | 0.6 | 1.4 |

| | IMF (WEO) | Jan-23 | 0.6 | 0.9 |

| | European Commission | Feb-23 | 0.8 | 1.0 |

| | Note: For OECD data corrected for working days. |

________________________

12 Reference is made to the average of futures prices over the last ten business days ending 8 March 2023.

| 14 | MINISTRY OF ECONOMY AND FINANCE |

II. BASELINE MACROECONOMIC AND BUDGET FORECAST | |

II.2 RISKS TO THE BASELINE MACROECONOMIC FORECAST

This section contains an analysis of the international economic situation and related risks, as translated into precise sensitivity scenarios for the main exogenous variables of the forecast.

Although the global economy was more resilient than expected last autumn and international cyclical indicators offer an outlook for expansion, some dynamics could weaken economic activity compared to the official macroeconomic picture.

First, the effects of monetary policies are beginning to affect liquidity, especially in the US and Europe. While the slowdown in the growth of the general price index has been helped by the fall in energy commodity prices, interest rate interventions have not yet been reflected in a slowdown of core inflation. There is therefore a risk that a new rise in commodity prices, dictated by OPEC+ oil supply policies and a recovery in Chinese demand, could recreate inflationary pressures at a time when monetary policy is already restrictive.

Second, some risks for international trade come from the possible materialisation of a sharp slowdown in the US economy and a geopolitical climate in which new fronts of tension could be added to the existing ones. Moreover, the first scenario would also impact the exchange rate, while the second would add pressure on commodity prices.

In assessing the repercussions on the Italian economy of the materialisation of these risks, the trend scenario was appropriately subjected to four simulation exercises modifying the evolution of the main exogenous variables, employing the econometric models in use at the Treasury Department.

A first simulation concerns the dynamics of energy commodity prices. In addition to oil price risks, less favourable weather conditions (e.g., drought in the summer months and a colder winter ahead) could cause gas and electricity prices to rise again. Gas, electricity, and oil prices were therefore assumed to be 20 percent higher in the second half of 2023 and in 2024, declining in subsequent years but remaining higher than the base assumption. The materialisation of this risk scenario would reduce growth rates relative to the trend scenario by -0.3 percentage points in 2023 and -0.4 points in 2024.

A second simulation concerns the weakening of world trade, the result of an increased fragmentation of foreign trade and a generalised decline in international demand, which would manifest itself mainly in 2024 and 2025. In both years, the GDP growth profile would fall by 0.2 percentage points.

The exchange rate is also a key variable. A pronounced slowdown in the US economy could be followed by a reshaping of monetary policy. Lower interest rates would weaken the dollar, favouring an appreciation of the euro. As market participants have recently changed their forecasts in this direction, with a greater cut in policy rates in the current year for the Fed than for the ECB, the risk scenario makes use of forward exchange rates, which assume a greater appreciation of the euro against the dollar than in the baseline scenario. The result for Italy’s growth, working through the nominal effective exchange rate, would envisage a revision of the trend macroeconomic scenario of -0.1 percentage points in 2023, -0.3 points in 2024 and -0.6 points in 2025.

| MINISTRY OF ECONOMY AND FINANCE | 15 |

| | ITALY’S STABILITY PROGRAMME 2023 |

Lastly, with reference to risk factors linked to both global financial market conditions and idiosyncratic factors, an increase of 100 basis points in the yield rate of the 10-year BTP is assumed for all forecast years from 2024 onwards, which would cause a reduction in growth compared to trend of -0.1 percentage points in 2024 and -0.4 points in 2025.

| FOCUS | A risk (or sensitivity) analysis on exogenous variables |

| The baseline scenario of this Document incorporates the persistence of high inflation at a global level and the countervailing action of central banks, as well as the continuation of the international crisis linked to the conflict in Ukraine, albeit with the easing of tensions in gas supplies. The framework of uncertainty that characterises the international scenario suggests the advisability of considering certain risk elements in the trend scenario and assessing their repercussions on the Italian economy, should they materialise. |

| The alternative scenarios analysed concern less favourable assumptions about the profile of world demand, energy commodity prices, exchange rates and financial market conditions. To assess the effects on the trend macroeconomic framework of each of these risk factors, four different simulation exercises were conducted using both the ITEM econometric model and the MACGEM-IT computational model. |

| The first scenario concerns a weaker trend in world trade, due to various factors, including a greater fragmentation of foreign trade owing to heightened geo-political tensions and a slower-than-expected path of inflation retraction, which would push back the end of monetary policy tightening. The presence of these risk elements would not affect the current year, where the slowdown in world trade is already pronounced in the baseline scenario, but 2024 and 2025, with an annual change respectively of one and half a percentage point lower than in the baseline scenario. Foreign demand (weighted by trade with Italy) would thus grow by 2.9 percent in 2024 and 3.5 percent in 2025. In 2026, world trade performance would pick up, with growth of 4.4 percent, compared to 3.1 percent in the trend framework. World demand levels would return in line with those of the baseline scenario in the third quarter of 2026. |

| A second simulation concerns the evolution of energy commodity prices (oil, natural gas and electricity). The scenario prefigures a more sustained energy commodity price trend, due to heightened geopolitical tensions and less favourable weather conditions, characterised by drought in the summer months and a harsher winter than the one that has just passed. Gas, oil, and electricity prices in the second half of 2023 and in 2024 were assumed to be 20 percent higher than in the baseline scenario. They would gradually return to the levels outlined in the trend scenario in the following years, being still 10 percent higher in 2025 and 5 percent higher in 2026. Using the MACGEM - IT model, the impact of higher prices was determined both on production levels, considering the use of energy materials in different sectors and inter-sectoral linkages, and on household gas consumption. |

| The third scenario concerns exchange rate developments. The technical assumption underlying the trend framework is to keep exchange rates unchanged over the forecast horizon at the average levels of the most recent daily quotations (in particular, daily quotations in the ten-working-day period ending 8 March 2023 were considered). In the alternative scenario, exchange rates were set at levels corresponding to the most recently observed forward exchange rates (15 March 2023). This would result in a higher appreciation of the euro against the dollar in 2023 than in the baseline scenario (by 1.3 percent instead of 0.9 percent). In 2024, the euro would appreciate against the dollar by 0.6 percent, compared to its slight depreciation in the baseline scenario (-0.2 percent). In 2025, the euro would appreciate by 0.4 percent against the dollar, compared with no change in the baseline scenario. In 2026, the exchange rate of the euro against the dollar would remain unchanged, as in the trend scenario. As regards the nominal effective exchange rate, in 2023 the euro would appreciate more pronouncedly than in the reference scenario (by 1.8 percent versus |

| 16 | MINISTRY OF ECONOMY AND FINANCE |

II. BASELINE MACROECONOMIC AND BUDGET FORECAST | |

| | 1.4 percent). In subsequent years, with the nominal effective exchange rate unchanged in the baseline scenario, the euro would appreciate on average against other currencies by 1.5 percent in 2024, 2.4 percent in 2025 and 0.3 percent in 2026. These dynamics would be affected to a non-negligible extent by the expected depreciation against other currencies, implicit in the forward exchange rates, of the Turkish lira, the Brazilian real and the Russian rouble. |

| | The fourth scenario concerns risk factors related to financial market conditions. A level of the yield rate on the 10-year BTP was assumed to be 100 basis points higher than the trend in each year of the forecast horizon, due to the possible transmission to the sovereign debt segment of tensions generated in other segments of the financial system. These less favourable conditions for sovereign debt financing would not affect 2023, but all subsequent years of the forecast horizon. In this alternative scenario, the higher levels of the BTP-Bund spread from 2024 onwards would lead to less favourable conditions for customers in accessing credit, with the application of higher interest rates on credit to households and businesses. |

| | The assessment of the effects on economic activity levels of the risk factors outlined above is shown in Table R1. Under the assumption of weaker world trade developments starting next year, the GDP growth rate would be lower than in the trend scenario by 0.2 percentage points in both 2024 and 2025. The strong recovery in 2026, with foreign demand returning to the levels of the baseline scenario in the third quarter of the year, causes GDP to grow by 0.3 percentage points more in that year than in the baseline scenario. Less favourable developments in energy prices cause the GDP growth rate to fall by 0.3 percentage points in 2023 and 0.4 points in 2024. The adjustment path would start gradually from the following year, with GDP growth rates higher than the reference framework by 0.4 and 0.2 percentage points in 2025 and 2026, respectively. |

| | Regarding exchange rates, the higher appreciation of the euro relative to what is projected in the framework would result in a GDP growth rate that is lower by 0.1 percent in 2023, 0.3 percent in 2024, 0.6 percent in 2025 and 0.3 percent in 2026. In the scenario of a deterioration of the economy’s financial conditions, the GDP growth profile would be lower than in the trend scenario by 0.1 percentage points in 2024, 0.4 points in 2025 and 0.5 points in 2026. |

| | |

| | TABLE R1: GDP EFFECTS OF RISK SCENARIOS (impact on percentage growth rates compared to trend macroeconomic framework) |

| | | 2023 | 2024 | 2025 | 2026 |

| | 1. World trade | 0.0 | -0.2 | -0.2 | 0.3 |

| | 2. Energy commodity prices | -0.3 | -0.4 | 0.4 | 0.2 |

| | 3. Nominal effective exchange rate | -0.1 | -0.3 | -0.6 | -0.3 |

| | 4. Financial conditions of the economy | 0.0 | -0.1 | -0.4 | -0.5 |

II.3 BUDGETARY OUTLOOK UNDER EXISTING LEGISLATION

The forecasts in the existing legislation scenario of public finance take into consideration the updated baseline macroeconomic scenario and the most recent data from the monitoring of general government revenue and expenditure trends, including the accounting effects of the reclassification of tax credits made by ISTAT13. They also include the further realignment of the assumptions on the time

________________________

13 Please refer to the Focus ‘Superbonus 110: impact of accounting reclassification, temporary solutions and long-term perspectives’ for all related details.

| MINISTRY OF ECONOMY AND FINANCE | 17 |

| | ITALY’S STABILITY PROGRAMME 2023 |

profile of the expenditure financed by the Next Generation EU programme, and the measures adopted in the final months of 2022 and in the first months of the year, in particular those to contain the effects of the increase in energy prices envisaged by the 2023-2025 budget law and by the recent decree-law No. 34 of 30 March 2023.

The general government net borrowing for the current year is projected at 4.4 percent of GDP, a level slightly below the DBP target of 4.5 percent, and in sharp decline from 8.0 percent in 2022.

On the primary balance side, the upward revision of the inflation rate and GDP forecasts, compared to the DBP forecasts, leads to an increase in revenues, both from indirect and direct taxes. The downward trend of energy prices, in gradual stabilisation, allowed for a containment of public finance costs for extraordinary measures to support households and businesses in the first quarter. In fact, the recent decree-law No. 34 of 2023 envisages measures amounting to approximately EUR 3.6 billion in gross terms, entirely covered by the expenditure savings resulting for the support measures in the first quarter of 2023, thus being neutral on budget balances. The primary balance would thus improve to -0.6 percent of GDP from - 3.6 percent of GDP in 2022.

Regarding interest expenditure, the forecast for 2023 is 3.7 percent of GDP, down from 2022, due to the lower inflation rate resulting in a lower revaluation of price-indexed securities.

For the next three years, by contrast, interest expenditure is projected to increase to 4.1 percent of GDP in 2024, 4.2 percent in 2025 and 4.5 percent in 2026. This is because increasing shares of the stock of public debt will have absorbed the higher yields resulting from the ECB’s raises of reference rates.

Expenditure on social transfers is expected to grow at a sustained pace especially in 2023 and 2024, as it is affected by benefit indexation based on the previous year’s inflation rate.

In addition, the reshaping of RRF flows results in a higher concentration of public investment expenditure, particularly in 2024 and 2025.

These expenditure increases are, however, more than offset by the phasing-out of temporary measures for high energy prices, and by the complete elimination of exceptional interventions to cope with the effects of the pandemic. Primary expenditure as a ratio of GDP is projected to fall from 52.4 percent in 2022 to 45.1 percent in 2026.

As a result of these factors, in the baseline scenario under existing legislation, the general government net borrowing as a ratio of GDP is projected on a moderately better profile than in the DBP, falling to 3.5 percent in 2024, 3.0 percent in 2025 and 2.5 percent in 2026, a level that is below the 3 percent threshold indicated by the Stability and Growth Pact.

In the same scenario, the debt-to-GDP ratio is projected to continue on a downward path, albeit at a slower pace than the extraordinary reductions observed in the last two years (-5.5 percentage points recorded in 2022 relative to 2021 and -5.0 percentage points recorded in 2021 relative to 2020). The ratio is expected to fall from 144.4 percent in 2022 to 140.4 percent in 2026.

| 18 | MINISTRY OF ECONOMY AND FINANCE |

II. BASELINE MACROECONOMIC AND BUDGET FORECAST | |

| FIGURE II.1: PRICE INDICES AND BALANCES AT EXISTING LEGISLATION (y/y change and % of GDP) |

|

| Source: ISTAT. As of 2023, forecasts under the existing legislation scenario of this Document. |

| FOCUS | SUPERBONUS 110: IMPACT OF ACCOUNTING RECLASSIFICATION, TEMPORARY SOLUTIONS AND LONG-TERM PERSPECTIVES |

| |

| Accounting reclassification |

| Starting in 1998, several tax benefits have been introduced in Italy for the requalification of existing buildings, which have been extended, more recently, to include energy efficiency and seismic risk reduction interventions. These measures consist of tax deductions proportionate to the amount of expenditure incurred, with different rates depending on the type of intervention. |

| Over the last few years, significant changes have been made to the system of eligibility for building incentives, which have significantly increased the deduction rate and allowed for the possibility, as an alternative to direct use, of a discount on the invoice paid in advance by suppliers or the transfer of the deduction in the form of a tax credit. |

| Among the various incentives, the so-called sismabonus, superbonus and external redecoration bonus are particularly important. |

| The sismabonus provides for a deduction of 50 percent, 70 percent and 80 percent of the expenses incurred, which varies depending on the degree of seismic risk reduction achieved through the intervention, with further increases in the case of works carried out on the common areas of apartment buildings (75 percent or 85 percent). |

| For expenditure incurred from 1 July 2020, the superbonus was introduced, raising the deduction rate up to 110 percent for expenditure on specific works in the field of energy efficiency and anti-seismic interventions on buildings. Then, with effect from 1 January 2023, the deduction was reduced to 90 percent for interventions carried out in 2023 in apartment buildings and those carried out by individual residents on building units. The 90 percent deduction of the expenses also applies to new interventions on single-family houses, begun as from 1 January 2023, only if the owner (or the holder of the real right) has a reference income, determined on the basis of coefficients that take into account the size of the household, not exceeding EUR 15,000 and the property is used as a main residence. |

| Regarding the external redecoration bonus, the tax relief consisted in a tax deduction of 90 percent of the expenses incurred in 2020 and 2021, and 60 percent of the expenses incurred in 2022, for interventions aimed at the recovery or restoration of the external facade of existing buildings, of any cadastral category, including commercial property. |

| MINISTRY OF ECONOMY AND FINANCE | 19 |

| | ITALY’S STABILITY PROGRAMME 2023 |

| | The introduction in 2020 of the invoice discount and credit transfer options has changed, from a statistical point of view, the nature of certain benefits and, consequently, their recording in the national accounts. |

| The ESA 2010 provides for two distinct types of tax credits, ‘payable’ credits and ‘non-payable’ credits. The ‘payable’ credits are those that can be reasonably expected to be used in full by the beneficiary irrespective of the size of the beneficiary’s tax liability at the time of their accrual, either through refund or through the possibility of using them as a set-off against taxes and social security contributions due, possibly even in years after the year of accrual. Such credits give rise to a debt of a definite amount owed by the State to the beneficiary and must therefore be recognised as an expense, with an impact on net borrowing in the year in which the right to the benefit arises for the full amount due (on an accrual basis), regardless of when they are used. |

| Conversely, ‘non-payable’ credits become uncollectable once the taxpayer’s tax credit limit is exceeded. They are recorded as a reduction in tax revenues, with an impact on net borrowing in the years in which they are used by the taxpayer. |

| The measures that introduced and then extended the building incentives with the transfer option had, however, discounted the related financial effects in terms of lower tax revenues according to the time profile of the use of the benefit as offset or deduction. This accounting treatment was consistent with the classification of tax credits as ‘non-payable’ according to the ESA 2010 and in line with the provisional opinion issued by Eurostat on 8 June 2021 on the statistical treatment of the superbonus. |

The new version of the 2022 Manual on Government Deficit and Debt, published by Eurostat on 1 February 2023, provided clearer guidance for distinguishing ‘payable’ and ‘non-payable’ credits and for identifying the time of recording. The new text considers three criteria for identifying ‘payable’ credits: transferability, deferral of use to years following the year of accrual, and the possibility of offsetting credits against any type of tax or social contribution owed by the beneficiary taxpayer. These characteristics of the credit, by increasing the likelihood of actual and full utilisation of the tax benefit, determine its classification as ‘payable’. |

| |

| Impact on net borrowing and public debt |

| Based on the criteria set forth in the new version of the Manual on Government Deficit and Debt, ISTAT, in agreement with Eurostat, classified the superbonus 110 and the external redecoration bonus as ‘payable’ and, consequently, recorded in expenditure (as investment grants) the full amount of the credit accrued in the year in which the taxpayer incurred the expenditure giving rise to the tax benefit. |

| The revision of the classification, announced with the publication of the preliminary estimates for GDP and net borrowing on 1 March 2023, resulted in the effects on net borrowing being brought forward in time compared to the cash recording. Considering the accounting reclassification of the two credits, the general government net borrowing was revised upward by 0.2 pp. of GDP in 2020 and 1.8 pp. of GDP in 2021. Overall, over the three-year period 2020-2022, the impact of the reclassification can be estimated at approximately 4.6 percentage points of GDP. |

| The reclassification entails, all other things being equal, an upward revision of the general government expected tax revenues for the years to come. In this regard, note that in the forecasts contained in the Update to the 2022 Stability Programme and in the 2023 Draft Budgetary Plan of last November, the expected financial effects of the two building incentives were spread over the period of use of the deductions, consistently with the accounting of the tax deductions as a reduction of tax revenues for the portion of the credit due in the year. |

| The updated forecasts consider the effects on public finance under the new accounting rules, pending new directions from the statistical authorities, which may revise the recording |

| 20 | MINISTRY OF ECONOMY AND FINANCE |

II. BASELINE MACROECONOMIC AND BUDGET FORECAST | |